CHAPTER 57 Disorders of the Vagina and Uterus

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH TO VULVAR DISCHARGE

Vulvar discharge is commonly found in bitches with disorders of the reproductive tract and, less commonly, disorders of the urinary tract. Vulvar discharge is also normal during proestrus, estrus, and the postpartum period. Vulvar discharge is uncommonly observed in queens. Determining the significance of the discharge depends on the stage of the reproductive cycle, the cellular composition of the discharge, and the source of the discharge. The diagnostic approach includes a thorough history-taking, physical examination, vaginal cytology, and vaginoscopy. When taking the history, the clinician should establish the stage of the reproductive cycle and the overall health of the bitch. The complete physical examination includes inspection of the discharge and vulva and palpation of the reproductive tract. Disorders of the vulva, vestibule, or vagina rarely cause signs other than vulvar discharge, licking of the vulva, and/or pollakiuria. Physical abnormalities are usually confined to these areas. In contrast, disorders of the uterus frequently result in systemic signs of illness in addition to a vulvar discharge. Historical findings such as malaise, weight loss, vomiting, or polydipsia-polyuria are suggestive of systemic illness, as are physical findings such as fever and dehydration. They deserve prompt attention.

The character of the vulvar discharge is determined by visual inspection and vaginal cytology (Box 57-1). Some characteristics, such as meconium, urine, and uteroverdin, can be confirmed by visual inspection. Uteroverdin is the dark green heme pigment normally found in the canine placenta. In the cat placental blood is red-brown in color. Its presence in a vulvar discharge indicates that placental separation has occurred. This is normal during stage II of parturition and during the first few hours postpartum, but it is abnormal at any other time. Sometimes, inflammation of the lower urinary tract or vestibule will cause dribbling of urine, which may be described by owners as a discharge. Meconium is the bright yellow fetal fecal material. Its presence indicates extreme fetal distress.

BOX 57-1 Differential Diagnoses for Vulvar Discharge Based on Predominant Cytologic Characteristics

BOX 57-1 Differential Diagnoses for Vulvar Discharge Based on Predominant Cytologic Characteristics

There are two important aspects of evaluating vaginal cytology. The first is examination of the vaginal epithelial cells for the maturation and cornification induced by estrogen (see Chapter 56 and Fig. 56-6). The second is identification of other cell types and mucus. The source of the vulvar discharge is confirmed by physical examination of the vulva and endoscopic examination of the vestibule and vagina. If a uterine source of the discharge is suspected, abdominal radiography and/or ultrasonography of the uterus should also be performed. Further diagnostic tests may be indicated once the origin and probable cause of the discharge have been established.

HEMORRHAGIC VULVAR DISCHARGE

Red blood cells (RBCs) are commonly found in normal and abnormal vulvar discharges. The other types of cells that are also present, particularly vaginal epithelial cells and white blood cells, determine their significance. In addition to the plentiful RBCs, the predominant cytologic finding during normal proestrus and estrus is numerous mature (cornified) superficial vaginal epithelial cells, indicating an estrogenic influence. White blood cells (WBCs) and extracellular bacteria may also be present. Ovarian remnant syndrome, exogenous estrogen, and the pathologic production of estrogens by ovarian follicular cysts or ovarian neoplasia can cause similar cytologic findings.

When RBCs are the predominant cytologic finding in the absence of cornified vaginal epithelial cells (i.e., no estrogenic influence), a cause for hemorrhage, such as vaginal laceration, uterine and vaginal neoplasia, subinvoluted placental sites, uterine torsion, and coagulopathies, should be sought. Vaginal laceration or other trauma to the reproductive tract is uncommon but may occur during breeding or as a result of vaginoscopy or obstetric procedures. Although bleeding from the vulva is certainly not common in animals with coagulation defects, it has been observed as the sole site of bleeding in some bitches with coagulopathies. When RBCs are accompanied by WBCs as the predominant cytologic abnormality, especially when the number of WBCs exceeds that expected in peripheral blood, a cause of inflammation (WBCs) rather than of hemorrhage (RBCs) should be sought.

MUCOID VULVAR DISCHARGE

Mucus is the predominant component of the normal postpartum discharge, lochia (see Chapter 59). It may also be present during normal late pregnancy and possibly in small amounts during the nonpregnant luteal phase. Cervicitis and mucometra can cause a mucoid vulvar discharge. In rare instances no apparent cause can be found in some bitches with small amounts of mucous discharge.

EXUDATE

Cellular debris is often the predominant component of the discharge that accompanies abortion and also of the discharge that accompanies the metritis associated with retained fetal or placental tissue. Some debris is also present in lochia.

Purulent Vulvar Discharge

Purulent and mucopurulent vulvar discharges are characterized by a predominance of polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs), with or without mucus. When bacteria are also present, the exudate is referred to as septic. Large numbers of PMNs without signs of degeneration or sepsis are often found during the first day or two of diestrus (see Chapter 56). This normal diestrual return of WBCs to the vaginal smear can be differentiated from inflammation of the reproductive tract by the absence of clinical signs, the temporal correlation with recent estrus, and the prompt disappearance of WBCs within 48 hours of the onset of diestrus.

A nonseptic exudate is often found in prepubertal bitches with vaginitis. Androgenic stimulation (exogenous testosterone or an intersex condition) can also cause a nonseptic inflammation. Other causes of nonseptic and septic vulvar discharges include vulvitis, vaginitis, pyometra, metritis (see Chapter 59), abortion (see Chapter 58), and a uterine stump granuloma or abscess.

ABNORMAL CELLS

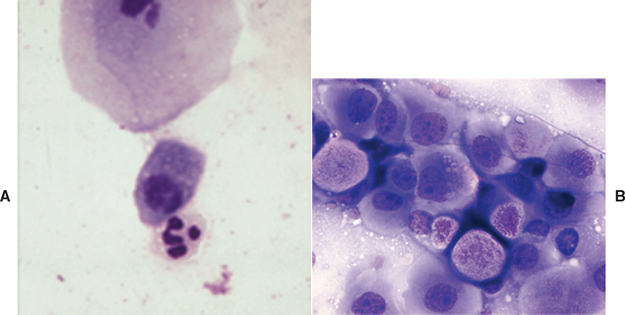

The characteristic appearance of endometrial cells easily distinguishes them from other cells seen on vaginal cytologic preparations. They are columnar and have a basal nucleus and foamy cytoplasm (Fig. 57-1). The presence of endometrial cells indicates uterine involvement. They may be found in animals with cystic endometrial hyperplasia, even in the absence of an overt vulvar discharge, or, less commonly, in lochia and in animals with metritis. Transmissible venereal tumors and transitional cell carcinomas readily exfoliate, and neoplastic cells may be found on vaginal cytologic preparations (see Fig 57-1). Leiomyomas do not readily exfoliate.

ANOMALIES OF THE VULVA, VESTIBULE, AND VAGINA

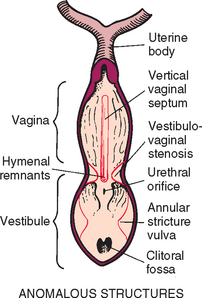

The müllerian ducts are the embryologic origin of the uterine tubes, uterus, and vagina. The vestibule, urethra, and urinary bladder develop from the urogenital sinus. Thus the vestibulovaginal junction is immediately cranial to the urethral orifice. The genital folds also form part of the vestibule (Fig. 57-2). The fusion of the Müllerian ducts with the urogenital sinus forms the hymen, which is composed of two epithelial surfaces separated by a thin layer of mesoderm. In bitches the hymen reportedly disappears before birth. The genital tubercle gives rise to the clitoris, and the genital swellings become the labia (vulva).

FIG 57-2 Anatomic location of normal structures and common congenital anomalies of the canine vagina and vulva.

(Redrawn from Miller ME et al, editors: Anatomy of the dog, Philadelphia, 1964, WB Saunders.)

The abnormal formation or disappearance of the hymen can result in a vertical band of tissue or in an annular stricture at the vestibulovaginal junction. The latter condition has also been referred to as vestibulovaginal stenosis. Abnormal or incomplete fusion of the paired müllerian ducts can result in the formation of an elongated vertical septum that bisects the vagina (Fig. 57-3) or in the formation of a vaginal diverticulum (pouch). Vaginal diverticula are uncommon. Complete duplication of parts of the urogenital tract, including a true double vagina, has been reported, but this is extremely rare. Abnormal fusion of the genital folds with the genital swellings can result in the formation of strictures within the vestibule and vagina. With the exception of abnormalities of the vulva and vestibule, the common congenital anomalies are located immediately cranial to the external urethral orifice. Hypoplasia or agenesis of parts of the reproductive tract also occurs. All these congenital anomalies of the vagina and vulva have been found in bitches, but they are apparently extremely rare in queens.

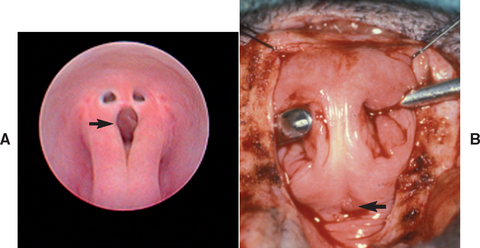

FIG 57-3 Vaginal septa in two bitches. A, Via vaginoscopy with saline infusion. B, Via episiotomy. Spay hook used to bring septum into surgical field. Arrow indicates urethral orifice.

Growth and maturation of the vulva and vagina depend on the ovarian hormones. When ovariectomy is performed before puberty, the reproductive tract remains in its infan-tile or juvenile stage of development. When the ovaries are removed after puberty, some atrophy occurs, but the reproductive tract does not return to its prepubertal size. Depending on the smallness of the vulva and the overall perineal conformation, the vulva may be recessed in the perineal skin. A recessed vulva could be congenital or acquired. In some obese individuals rolls of perineal fat cover the vulva.

Clinical Features

Anomalies of the vulva and vagina often cause no clinical signs, or they may be associated with perivulvar dermatitis, recurrent urinary tract infections, chronic vaginitis, or refusal to mate. Vulvar-vaginal anomalies are often recognized only because the female refuses to mate or because the male dismounts without being able to achieve intromission. Occasionally, vulvar-vaginal anomalies are associated with urinary incontinence. This may be due to urine pooling anterior to the lesion, or there may be other, concurrent congenital anomalies in the urogenital tract, such as ectopic ureters.

Diagnosis

Anomalies of the vulva and vagina are easily identified by physical examination and digital palpation. Most anomalies involve the caudal aspect of the tract, from the vestibulovaginal junction outward, and are easily reachable. Vaginoscopy (see Chapter 56) is very useful for evaluating the vestibule and vagina and may be combined with urethrocystoscopy in cases with urinary incontinence. Vaginography (see Chapter 56) can also be performed, but care must be taken with the plane of anesthesia, positioning of the patient, and interpretation of the findings. The vestibulovaginal junction is normally so narrow during anestrus, especially in pubescent bitches, that it may be mistaken for a stricture or stenosis. Furthermore, contraction of the constrictor vestibuli muscle, which may occur during manipulation of the genitalia, resembles a stricture. Before surgical treatment of vestibulovaginal stenosis (annular strictures) is considered for an intact animal, it should be evaluated during proestrus and estrus, at which time the normal vestibulovaginal junction relaxes considerably and is easily differentiated from a true stricture. Some strictures in the vestibule-vulva also “relax” during estrus. Abdominal radiography or ultrasonography can be performed to identify vaginal diverticula.

Treatment

Anomalies of the vulva and vagina often are incidental findings. Treatment is unnecessary if they are causing no clinical signs. Anomalies of the vulva and vagina that are causing clinical signs should be corrected surgically, during anestrus. Vulvar anomalies are corrected by episioplasty. The prognosis after episioplasty for recovery from perivulvar dermatitis, recurrent urinary tract infection, and vaginitis is excellent. Episioplasty should be delayed until puppies have reached physical maturity and, whenever possible, obese animals have returned to normal body condition. Thin bands of persistent hymenal tissue can sometimes be broken using digital pressure alone. Some annular strictures are amenable to bougienage. Surgical repair is necessary for the treatment of vaginal septa, and this can be achieved with minimally invasive endoscopy or an episiotomy (see Fig. 57-3). The prognosis for normal mating ability after surgical correction of vaginal septa and hymenal remnants is excellent. Animals with annular strictures may be prone to fibrosis and restricture. Celiotomy may be necessary to correct a vaginal diverticulum. Because hypoplasia or agenesis cannot be rectified, affected animals should be neutered to prevent additional complications, such as cystic endometrial hyperplasia. The role that heredity plays in the development of congenital vaginal and vulvar anomalies in bitches is unknown, but it is known that certain vaginal anomalies are inherited in mice.

CLITORAL HYPERTROPHY

In the female the clitoris develops from the genital tubercle, as does the penis in the male. Under the influence of androgens the canine clitoris may enlarge and even ossify. This can be caused by in utero exposure of female fetuses to androgens and progestins, by exogenous androgen administration to females of any age, or by endogenous androgen production from testicular tissue in intersex animals. Intersex is a term used to describe individuals with ambiguous genitalia in which the specific cause has not yet been determined. The cause may be abnormalities in chromosomal sex (e.g., XXY, XO, or XX/XY), gonadal sex (e.g., testis, ovotestis, and XX sex reversal), or phenotypic sex (e.g., ambiguous genitalia or discrepancy between internal and external genitalia, ±cryptorchidism). In utero exposure of female fetuses to androgens causes abnormal phenotypic sex. The external genitalia are ambiguous or cryptorchid male, whereas chromosomal sex is normal XX, the gonadal sex is normal ovary, and the internal genitalia are normal uterus, ±epididymis.

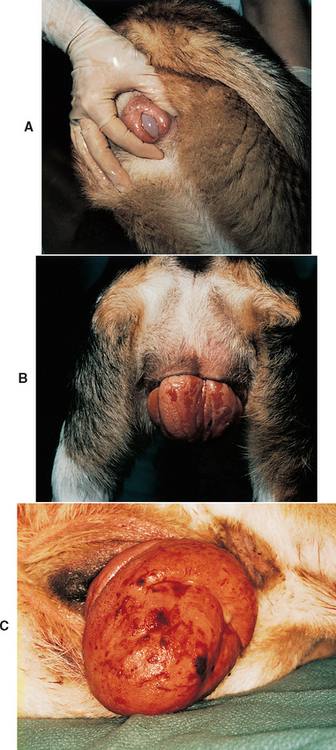

Clitoral hypertrophy may go unnoticed. More commonly, however, the enlarged clitoris protrudes from the vulva. This is often first apparent when the animal nears puberty or following the administration of exogenous androgens. A mucoid discharge is common, as is licking of the area. There may be a history of recurrent urinary tract infection. Physical examination will demonstrate the abnormal clitoris, which occasionally will have a distinctly phallic shape. When present, ossification is usually palpable. The vulva may have a normal appearance and position, or in intersex animals it may be ventrally displaced anywhere along the line from the normal vulvar position to the normal position of the preputial orifice (Fig. 57-4). This is because of the embryologic influence of androgens on the genital swellings, which normally develop into either the vulva (no androgen) or the prepuce and scrotum (androgen). The vestibule-vagina may be imperforate in females exposed in utero and in intersex animals.

FIG 57-4 Clitoral hyperplasia in a 1-year-old Weimaraner examined because of recurrent urinary tract infection and vulvar discharge. Note the ventral displacement of the vulva. Testes and uterus were found at surgery. Gonadectomy, hysterectomy, and clitorectomy were curative.

Treatment is to remove the source of androgen if it still exists. The hypertrophic soft tissue of the clitoris will usually regress, but ossified tissue is usually permanent. Unless it is clear that a previously normal female has been treated with androgens, such as might be the case with racing Greyhound bitches, affected animals should be evaluated for the presence of an intersex condition. Exploratory laparotomy with the intent of removing the gonads and internal genitalia may be the most cost-effective approach, although hormonal testing to confirm the presence of testicular tissue and karyotyping easily can be done (see Chapter 56). Clitorectomy may be needed to eliminate the clinical signs associated with chronic exposure.

VAGINITIS

Vaginitis (i.e., inflammation of the vagina) occurs in sexually intact or neutered bitches of any age or breed during any stage of the reproductive cycle. It is rare in queens. Vaginitis may result from immaturity of the reproductive tract; anatomic abnormalities of the vagina or vestibule; chemical irritation, such as that caused by urine; bacterial, viral, or yeast infections; androgenic stimulation; or mechanical irritation, such as that caused by foreign material or neoplasia.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based primarily on the historical and physical finding of a mucoid, mucopurulent, or purulent vulvar discharge, which is present in most bitches (90%) with vaginitis. The vulvar discharge of vaginitis rarely contains blood, except in cases caused by foreign material or neoplasia. Licking of the vulva and pollakiuria are less common additional clinical signs that are present in about 10% of affected animals. Animals with vaginitis are otherwise normal and healthy. If they are not, a diagnosis in addition to, or other than, vaginitis should be pursued. For example, the vulvar discharge may be originating from the uterus, not the vagina, in the case of pyometra. The diagnosis of vaginitis can be substantiated by vaginal cytology and vaginoscopy, but this is not always necessary for a first occurrence. The cytologic finding with vaginitis is nonseptic or septic inflammation without hemorrhage. Vaginoscopy is especially useful for identifying the underlying cause of vaginitis, such as anatomic abnormalities, foreign material, or neoplasia. The extent of the vaginal inflammation can also be assessed by vaginoscopy, and biopsies can be obtained if indicated. Urinalysis and urine culture should be performed in animals with a history of pollakiuria. Because the bacterial organisms isolated from bitches with vaginitis are quantitatively and qualitatively similar to the normal bacterial florae of the canine vagina, vaginal cultures are not helpful in the diagnosis of vaginitis. Rather, the results of bacterial culture and sensitivity testing are used to guide the formulation of a rational therapeutic plan. The clinical findings, diagnostic approach, treatment, and prognosis of canine vaginitis vary according to the age of the bitch.

PREPUBERTAL BITCH

In bitches younger than 1 year of age, physical and historical abnormalities almost always consist only of the vulvar discharge and inflammation of the vulva and vagina. The animals are otherwise healthy. Vaginal cytologic findings are most often nonseptic in nature. Systemic or topical antibiotics, douches, and perineal cleansing are common treatments, but the evidence shows that 90% of young bitches recover from vaginitis with or without treatment. Therefore healthy young bitches in which clinical findings are limited to a nonhemorrhagic vulvar discharge usually need no further diagnostic tests and require no treatment. Most such animals recover spontaneously as they reach physical maturity. Whenever any additional historical or physical abnormali-ties are found, young bitches should be evaluated using the approach described for the mature bitch.

The role of estrus, if any, in the resolution of vaginitis in young bitches is unclear. Because attaining physical and sexual maturity is so closely related, it is difficult to evaluate the relative contributions of each. In some bitches there is a temporal relationship between the onset of estrous activity and the resolution of vaginitis. However, vaginitis resolves spontaneously in most young bitches as they reach physical maturity, irrespective of estrus. Because ovariohysterectomy is traditionally performed before the first heat, the evidence is clear that ovariohysterectomy does not hasten the resolution of vaginitis. However, the effect of ovariohysterectomy on the persistence of vaginitis in the prepubertal bitch has not been reported. Because maturation of the reproductive tract during estrus may cause vaginitis to resolve (or, conversely, the absence of estrus may enable chronic vaginitis to persist), consideration may be given to delaying ovariohysterectomy in young bitches with chronic vaginitis until after the first heat.

MATURE BITCH

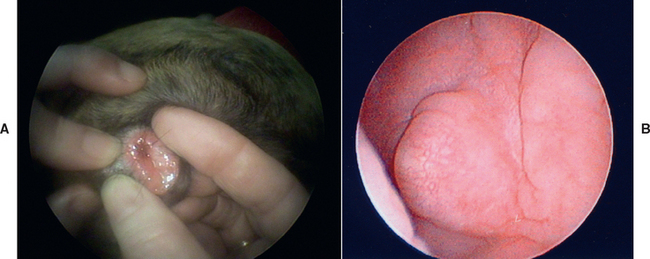

A predisposing factor for vaginitis can be identified in most (70%) affected bitches older than 1 year. The key to the successful therapy of vaginitis in mature bitches is the identification and elimination of underlying disorders. Of the identifiable factors in mature bitches, abnormalities of the genital tract are the most common (35%). They are found during physical and endoscopic examinations and include vulvar anomalies, vaginal strictures, vertical vaginal septa, foreign material, clitoral hypertrophy, and vaginal neoplasia (Fig. 57-5). Disorders of the urinary tract, including urinary tract infection and urinary incontinence, are the next most commonly (26%) identified abnormalities in mature bitches with vaginitis. Therefore thorough physical examination and vaginoscopy to identify abnormalities in the genital tract, vaginal cytology to characterize the discharge, and analysis and culture of urine obtained by cystocentesis should always be included in the evaluation of mature animals with vaginitis. Canine herpes virus infection has been cited as a rare cause of vesicular lesions on the mucosal surfaces of the genitalia in bitches and dogs. The lesions are discovered on the vulvar mucosa or during vaginoscopy. They rarely cause discharge or other signs of vaginitis, and isolation of the virus is rarely reported. Much more commonly, canine herpes virus infection causes fulminant multiorgan system failure and death in neonates, mild respiratory infection in adults, and abortion.

FIG 57-5 Vaginal abnormalities. A, Vaginal dermoid causing discharge in a 3-month-old Boxer. B, Fibroma in an 11-year-old spayed Golden Retriever with swollen vulva, chronic mucopurulent discharge, and ovarian remnants with follicular cysts and luteoma.

The resolution of vaginitis in mature bitches is directly related to the elimination of the underlying disorder. The prognosis is excellent for resolution of vaginitis after vulvar and vaginal anomalies are surgically corrected, after foreign material is removed, and after urinary incontinence is controlled. Urinary tract infection and vaginitis have some mutual predisposing causes as well as being predisposing factors for each other. Fortunately, correction of mutual causes and appropriate antibiotic therapy usually resolve both, irrespective of which came first. The choice of antibiotics should be based on the results of urine culture. Some mature bitches with vaginitis recover spontaneously.

The role of estrus, if any, in resolving vaginitis in mature bitches is unknown. The signs of vaginitis continue to improve in some mature bitches with each succeeding cycle. In others there is no apparent change in response to estrus. The effects of ovariohysterectomy on vaginitis in mature bitches are even less clear. In most bitches ovariohysterectomy has no apparent therapeutic effect on the outcome. Signs of vaginitis occur after ovariohysterectomy in some previously healthy bitches.

CHRONIC, NONRESPONSIVE VAGINITIS

Animals with chronic vaginitis in which an underlying cause has not been found and that do not recover in response to appropriate therapy remain a source of frustration. The initial minimum database of history, physical examination, urinalysis and urine culture, vaginal cytology, and vaginoscopy should be repeated. The database should be expanded to evaluate overall health with a complete blood count (CBC) and biochemical panel and to assess the rest of the urogenital tract with abdominal radiographs and ultrasound. The purpose is to assess progression of disease with the minimum database and find clues to less common predisposing factors or underlying disease with the additional diagnostic tests. For example, uterine stump abscess or pyometra or abnormal hormone production from ovarian remnant should be considered in the spayed bitch with chronic vaginitis. Yeast vaginitis, which is very uncommon in bitches, can occur after long-term antibiotic therapy. Body condition may have changed such that recessed vulva is now a factor. As a final diagnostic step, biopsy should be considered.

Some veterinarians recommend the use of over-the-counter douches containing dilute vinegar or povidone-iodine for the treatment of canine vaginitis. There is no published evidence that vaginal douching is efficacious in the treatment of canine vaginitis. In women douching is one of the risk factors for the development of bacterial vaginosis (Eckert, 2006). Povidone-iodine is cited as a contact irritant cause of noninfectious vaginitis and vulvitis in women (Sobel, 1997). Given the anatomy of the canine vagina, the discomfort of vaginitis, and the need for adequate animal restraint, many pet owners are unable to instill douches into the vagina instead of the vestibule. Until there is evidence that douching is helpful and that it is not harmful in management of canine vaginitis, the practice should probably be discontinued.

NEOPLASIA

Leiomyoma is the most common neoplasm of the vagina and uterus in geriatric bitches and queens. It often causes hemorrhage. However, because leiomyomas do not exfoliate readily, neoplastic cells are usually not seen on cytologic preparations. The histologic diagnosis is made from biopsy specimens of the mass that is identified by palpation, diagnostic imaging, and/or vaginoscopy. Treatment of leiomyomas is surgical excision. The prognosis is good if the location of the tumor is amenable to complete surgical excision. Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) occasionally invades the vestibule-vagina from the urethra. When it does, it can often be detected by vaginal palpation and can be seen during vaginoscopy. TCCs readily exfoliate, and the diagnosis is easily made on the basis of cytology obtained directly from the lesions during vaginoscopy (see Fig 57-1). Treatment of TCC is chemotherapy. The prognosis for cure is guarded, but quality of life may be good while urine flow is maintained and urinary tract infection and inflammation are controlled.

Bitches with transmissible venereal tumors (TVTs) are more likely to be examined because of a mass protruding from the vulva than because of a vulvar discharge. TVT is a contagious round-cell tumor. Venereal transmission is most common. It occurs primarily on the mucosal surfaces of the external genitalia of male and female dogs, but it can be transplanted to other sites and transmitted to other dogs by licking and by direct contact with the tumor. Primary TVTs have been found on the skin and in the oral and anal mucous membranes. The prevalence of TVT varies greatly with the geographic area. For example, the prevalence of TVT among 300 pound-source bitches in Yucatan, Mexico, was 15% (Ortega-Pacheco et al., 2007). Some TVTs regress spontaneously, but most do not. Some TVTs are quite locally invasive, and some metastasize to the regional lymph nodes (Fig. 57-6). Rarely, metastasis to distant sites such as the lungs, abdominal viscera, or central nervous system (CNS) occurs.

TVTs have a fleshy, hyperemic appearance. Initially, they appear as a raised area. As they grow, they acquire a cauliflower-like shape and may reach a diameter of 5 cm or larger. They are often quite friable and bleed easily. TVTs in males are most often found on the bulbus glandis area of the penis, but they may appear anywhere on the penile or preputial mucosa. Affected animals are usually examined because of a mass on the external genitalia, but they may also be seen because of a preputial or vulvar discharge. The diagnosis of TVT is strongly suspected on the basis of the physical appearance of the tumor on the external genitalia. Differential diagnoses, especially in animals with nongenital lesions, include other round-cell tumors such as mast cell tumor, histiocytoma, and lymphoma. Pyogranulomatous lesions and warts of the genitalia may also have a similar gross appearance. The diagnosis of genital TVT is easily confirmed by exfoliative cytologic studies, fine-needle aspiration, or histopathologic findings.

TVTs respond to several chemotherapeutic agents. Vincristine, administered once weekly as a single agent (see Chapter 77), is quite effective for solitary, localized lesions. It has a low toxicity and is financially acceptable to most owners. It is administered for two treatments beyond the time when the tumor disappears. The total duration of treatment is usually 4 to 6 weeks. Complete remission is achieved in more than 90% of dogs treated with vincristine alone, and they usually remain disease free. TVTs are also extremely sensitive to radiation therapy. Although surgical excision results in long-term control, relapses occur in as many as 50% of animals.

VAGINAL HYPERPLASIA/PROLAPSE

During proestrus and estrus the vagina becomes edematous and hyperplastic. Sometimes, the change is so severe in bitches that vaginal tissue protrudes out of the vulva. This condition has been referred to as vaginal hyperplasia or vaginal prolapse because these are the most prominent microscopic and physical findings, respectively. Vaginal hyperplasia/prolapse occurs in bitches exclusively during times of estrogenic stimulation—in other words, during proestrus and estrus. On rare occasions, prolapse recurs later in the same cycle at the end of diestrus or at parturition, a time when additional estrogen may be secreted. It is common for vaginal hyperplasia/prolapse to recur during each estrus in affected individuals, although each episode is not always of the same severity.

The amount of edema and hyperplasia is extremely variable. Digital palpation of the vagina shows that the mass originates from the ventral vagina, immediately cranial to the urethral orifice. All other areas of the vagina are normal. If the edematous tissue is small enough to be contained within the vagina and vestibule, it is usually very smooth, glistening, and pale pink to opalescent because of the edema (type I vaginal prolapse; Fig. 57-7, A). If the hyperplastic tissue protrudes from the vulva, it is dry, dull, and wrinkled. With continued exposure, fissures and ulcers develop (type II vaginal prolapse; Fig. 57-7, B). Although the tissue protruding from the vulva may be quite massive, it originates from a stalk involving only a few centimeters of the vaginal floor. Much less commonly, the hyperplastic tissue involves the circumference of the vagina (type III; Fig. 57-7, C). In all three types of vaginal hyperplasia/prolapse, the tissue is located at the level of the urethral orifice; the rest of the vagina is normal. Despite the fact that the edematous hyperplastic tissue lies over the external urethral orifice, urine flow is rarely impeded.

The diagnosis of vaginal prolapse is made on the basis of the history and physical examination findings. Bitches may be seen because they refuse to allow intromission or because of the mass protruding from the vulva. The history indicates that they are in proestrus or estrus. If it does not, the stage of the cycle can be confirmed by vaginal cytology. The protrusion of this edematous, hyperplastic tissue must not be confused with a true prolapse of the vagina or uterus that occurs rarely during parturition (Fig. 57-8). The history alone (estrus versus parturition) should be sufficient to do so. If the clinician is concerned that the hyperplastic tissue could be neoplastic, the two can be differentiated on the basis of findings yielded by the cytologic examination of material obtained by fine-needle aspiration.

Treatment

The treatment of vaginal hyperplasia/prolapse is primarily supportive. The edema and hyperplasia will resolve spontaneously when the follicular phase of the cycle and the ovarian production of estrogen are over. This can be hastened by ovariohysterectomy. Ovariohysterectomy also prevents the recurrence of vaginal hyperplasia/prolapse because there will be no more estrous cycles. After oophorectomy the edema and hyperplasia usually resolve within 5 to 7 days. There is no published evidence that the pharmacologic induction of ovulation hastens recovery.

Exposed tissue must be protected from trauma and, if the mucosa is damaged, from infection. This is usually accomplished by applying topical antibiotic (e.g., bacitracinneomycin-polymyxin) or antibiotic-steroid creams and cleaning the tissue (with warm saline solution or warm water and pHisoHex) as needed. Attention should also be paid to the underlying perineal and vulvar skin, which may be subject to maceration (see Fig. 57-7C). Potentially irritating bedding such as straw or wood chips should be removed. An Elizabethan collar may be used to prevent self-mutilation, but this is rarely necessary. Artificial insemination can be performed if vaginal hyperplasia/prolapse prevents copulation. The condition will resolve spontaneously as soon as the female goes out of heat. It is unlikely to recur (although this is possible) and cause dystocia at the time of parturition.

Surgical resection of the edematous tissue has been considered for brood bitches, but this should probably be reserved for extremely valuable animals. The hemorrhage that results is often significant, despite excellent surgical technique. The resection of hyperplastic tissue also does not prevent recurrence during subsequent estrous cycles, although the severity of the prolapse may be markedly reduced. We have seen one bitch with recurrent hyperplasia/prolapse in which the prolapse did not resolve despite ovariohysterectomy after the fourth recurrence. Resection was the only recourse. Because of its recurrent nature and the care required to manage severe cases, affected animals are not the best brood bitches. The role that heredity plays, if any, in the development of vaginal hyperplasia/prolapse is not known, but it appears to be at least familial in nature.

DISORDERS OF THE UTERUS

The clinical signs of disorders of the uterus are variable and nonspecific. For example, there may be no clinical signs associated with congenital anomalies such as segmental aplasia. Rather, it may be an incidental finding at the time of elective ovariohysterectomy. Conversely, in cycling animals segmental aplasia may be the cause of infertility. Many uterine disorders are manifested by the presence of an abnormal vulvar discharge. Uterine enlargement may cause abdominal discomfort and abdominal distention. In addition to those signs, uterine infections typically cause signs of systemic illness, such as anorexia, lethargy, polydipsia-polyuria, or fever. Uterine disease should be considered among the rule-outs for infertility, vulvar discharge, and postpartum illness. Uterine disease is much more likely in sexually intact animals, but the history of having been spayed does not exclude the possibility of a uterine stump abscess or granuloma, or pyometra in an animal with ovarian and uterine remnants.

Determining the stage of the estrus cycle is important for several reasons. First, some disorders are seen during certain stages; for example, pyometra is almost always seen during diestrus. Second, interpretation of diagnostic tests, such as cytology of vulvar discharge, depends on knowledge of the cycle. Physical examination will assess the overall health, and identify abnormalities in the reproductive tract. Uterine enlargement is usually detectable by abdominal palpation, especially in cats. Vulvar discharge may be more evident after palpation of the uterus. The absence of these findings, however, does not exclude uterine disease. Diagnostic imaging, particularly abdominal ultrasound, is extremely helpful. A uterine source of a vulvar discharge can be confirmed by vaginoscopy. Whenever there are signs of systemic illness, a CBC, biochemical panel, and urinalysis are indicated. The most common uterine disorders causing systemic illness in dogs and cats are pyometra (discussed later) and postpartum metritis (see Chapter 59).

Uterine neoplasia is rare in dogs and cats. Leiomyoma is the most common. Rarely, adenocarcinoma has been reported. Uterine neoplasia may be an incidental finding, or it may be associated with sangineous vulvar discharge, anorexia, weight loss, and abdominal discomfort and enlargement. The diagnosis is made by the finding of uterine enlargement on abdominal palpation and diagnostic imaging. Treatment is ovariohysterectomy. The prognosis for uterine leiomyoma is good if the location of the tumor is amenable to complete surgical excision. The prognosis for uterine carcinoma is poor because metastasis is often present. Focal, benign uterine masses, such as adenomomas, have also rarely been reported in geriatric bitches.

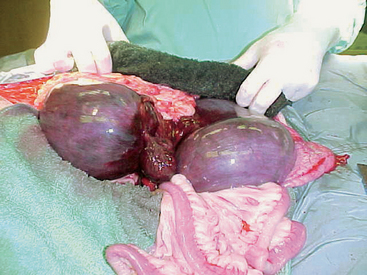

Uterine torsion is a life-threatening condition that usually occurs in the near-term gravid uterus in bitches and queens. It has also been reported in conjunction with other uterine pathology, such as hematometra and pyometra. One or both horns may be involved (Fig. 57-9). Affected animals are usually very ill and present as an acute abdomen with abdominal splinting and pain. Clinical signs also include sanguineous vulvar discharge and straining. The diagnosis is suspected on the basis of physical examination and ultrasonographic findings. It is confirmed at surgery. There are often significant metabolic derangements that should be evaluated with a biochemical panel and/or venous blood gas analysis. Treatment is ovariohysterectomy and intensive supportive therapy.

CYSTIC ENDOMETRIAL HYPERPLASIA, MUCOMETRA, AND PYOMETRA

CYSTIC ENDOMETRIAL HYPERPLASIA

Cystic endometrial hyperplasia (CEH) is characterized by an increase in the number, size, and secretory activity of the endometrial glands and by endometrial hyperplasia. Progesterone plays the most prominent role in the development of CEH, although it is not the only mechanism by which CEH can be experimentally induced. In bitches and queens CEH develops during the luteal phase (diestrus) of the cycle, a time when endogenous progesterone concentrations are high. It also develops in response to exogenous progestins under therapeutic as well as experimental conditions. The most common therapeutic use of progestins in bitches and queens is to suppress estrus. The endometrial response to endogenous and exogenous progesterone seems to be dose dependent because most affected animals are middle-aged, having experienced multiple cycles or having been treated for a length of time. In experimental conditions, as well as clinical application, the addition of estrogen when serum progesterone concentrations are high, such as is the case when estrogens are used for “mismating” in bitches, enhances the development of CEH, whereas estrogen alone does not cause CEH. Under experimental conditions ovariectomized 2- to 4-year-old bitches given a progestin (megestrol acetate) for 30 days developed CEH that was reversible when the progestin was withdrawn but that persisted when the progestin was continued. The same experiment confirmed previous findings that mechanical irritation of the endometrium (in this case by implanting silk suture material) also can cause CEH, but the silk-induced CEH was not maintained in the absence of the progestin (Chen et al., 2006). In and of itself, CEH does not cause clinical illness. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia does cause increased thickness in the uterine wall, which may be detectable on abdominal palpation and ultrasound. It may also cause decreased fertility.

MUCOMETRA

The general consensus is that CEH is the precursor of mucometra or hydrometra. In addition to the fluid accumulation within the cystic endometrial glands, sterile fluid accumulates in the uterine lumen. There may also be a mucoid or seromucoid vulvar discharge if the cervix is open. The dis charge is not purulent on cytologic evaluation. Uterine enlargement is detected by abdominal palpation and with diagnostic imaging. The uterus can be large enough to cause abdominal distention and associated signs of discomfort. Because bitches normally experience diestrus lasting more than 60 days after every estrous cycle and because queens usually experience diestrus only after having been induced to ovulate, mucometra is much more common in bitches than in queens.

Some bitches with mucometra also have a history of polydipsia-polyuria and vomiting or anorexia, but vital signs usually are normal and attitude usually is good. Ultrasonography will demonstrate the luminal fluid as well as the character of the uterine wall. Usually, the wall will be thicker than normal and the cystic nature of the endometrium is evident (Fig. 57-10). However, in some cases the histopathologic finding is endometrial atrophy. This may be related to the duration and degree of uterine distention. The historical and physical findings of animals with mucometra can be very similar to those of pregnancy or pyometra. Pregnancy can easily be excluded on the basis of ultrasound, but before days 42 through 45 of gestation when fetal skeletons become visible, the radiographic appearance of mucometra and the pregnant uterus is the same. Differentiating animals with mucometra from those with pyometra may be more difficult. Ultrasound alone would not be sufficient to differentiate among hydrometra, mucometra, and pyometra, but hydrometra and mucometra typically have a relatively anechoic ultrasonographic appearance, whereas the fluid associated with pyometra is usually echogenic. Animals with mucometra are not seriously ill, whereas those with pyometra often are. Both groups of animals are likely to be mildly anemic. The mean total WBC count of bitches with mucometra is normal, although an individual animal may have counts as high as 20,000/μl; whereas the mean total WBC of bitches with pyometra is reported to about 23,000/μl, with great variation among individuals. The most striking difference on the hemogram is the percentage of band neutrophils, which are much higher in bitches with pyometra. Fransson et al. (2004) reported that the percentage of band neutrophils had a sensitivity of 94% in differentiating pyometra from mucometra. Animals with mucometra typically have normal biochemical results. Ovariohysterectomy is curative. Medical management, as for pyometra, could also be considered for valuable breeding animals with mucometra.

PYOMETRA

Pyometra is characterized by purulent uterine contents and histologic evidence of variable degrees of inflammatory cell infiltrates (neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages) in the endometrium and, in severe cases, in the myometrium. There is also cystic endometrial hyperplasia, which is sometimes severe. Mild to severe fibroblast proliferation in the endometrial stroma, variable degrees of edema, necrosis, and sometimes ulceration of the endometrium and abscess formation in the glands are found. Occasionally, there is severe inflammation in the endometrium and myometrium, with endometrial atrophy rather than hyperplasia (De Bosschere et al., 2002). What initiates pyometra is still not completely understood. Although progesterone clearly plays a role, it is apparently not the sole explanation because serum progesterone concentrations are similar among normal healthy bitches and bitches with CEH, mucometra, and pyometra. It is also evident that neither CEH nor mucometra invariably progresses to pyometra. Differences in uterine estrogen and progesterone receptors have been demonstrated among normal, CEH, and pyometra specimens, but the differences have not always reached statistical significance and have not clearly demonstrated a different pathogenesis.

Bacterial invasion, presumably from the vaginal florae, is an important trigger. Escherichia coli is the most common organism isolated from bitches and queens with pyometra. Gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli produce endotoxins that are capable of initiating the cytokine cascade and the release of many inflammatory mediators. These are thought to be the cause of the local and systemic inflammatory reactions associated with pyometra. Inflammatory mediators such as C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-α, lactoferrin, and PGF2α are present in significantly greater serum or uterine concentrations in bitches with pyometra than in normal animals. Serum concentrations of C-reactive pro-tein and PGF2α are significantly greater in bitches with pyometra than in bitches with CEH alone. In addition to the local and systemic inflammatory response, bitches with pyometra are immunosuppressed as assessed by lymphocyte blastogenesis.

As with mucometra, pyometra is more common in bitches than in queens. Age, previous hormonal therapy, and nulliparous status are risk factors for the development of pyometra. The risk of developing pyometra increases with age, presumably because of repeated hormonal stimulation of the uterus. Reported mean ages of bitches with pyometra range from 6.5 to 8.5 years. There is a sixfold increased risk of pyometra in nulliparous bitches compared with primiparous or multiparous animals. Previous hormonal therapy with progestins and estrogen is also a risk factor. Estrogens given during diestrus, a time when endogenous serum concentrations of progesterone are high, increase the risk of pyometra. Younger bitches (mean age 5.5 years) that develop pyometra were more likely than older bitches (mean age 8.5 years) to have been treated with estrogens (Niskanen et al., 1998). Analysis of survival rates in Swedish dogs indicates that, on average, about 24% of bitches will develop pyometra by age 10 years. In Sweden progestins, rather than ovariohysterectomy, are the most common method used to control estrus.

Clinical Features

Pyometra is a serious, potentially life-threatening disorder because septicemia and endotoxemia can develop very quickly (over a matter of hours) and at any time. For this reason it is usually treated as an emergency situation. The clinical signs become evident during diestrus or early anestrus. The history typically shows that the female was in heat 4 to 8 weeks earlier or that progesterone was recently given, either as a treatment or as contraception. Owners often report a vulvar discharge. The other historical findings are not specific for pyometra. They include lethargy, anorexia, and vomiting. Polydipsia-polyuria is a common finding in bitches but not in queens. On physical examination a purulent, often bloody vulvar discharge is found in most (85%) bitches and queens with pyometra. Pyometra is classified as open or closed depending on whether there is a vulvar discharge. The degree of uterine enlargement is variable. Dehydration is a common finding, as is abdominal discomfort. Other physical examination findings vary according to the severity of sepsis or endotoxemia. Most affected animals are lethargic. Rectal temperature is often normal. Fever is reported in only 20% to 30% of bitches and queens with pyometra. Subnormal temperature may be found in those in septic or endotoxic shock. Capillary refill time may be prolonged.

Diagnosis

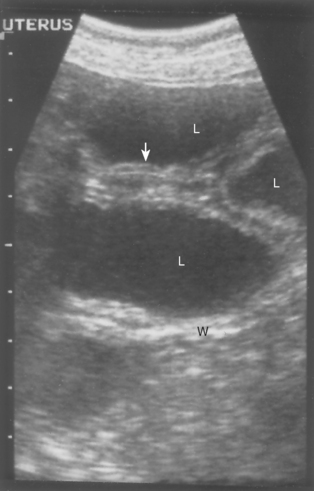

The diagnosis of pyometra is strongly suspected on the basis of the occurrence of clinical signs in a sexually mature female during or shortly after diestrus or after exogenous progestin administration, the presence of a septic vulvar discharge, and uterine enlargement. Abdominal ultrasound (or radiographs taken more than 45 days after having been in heat) confirms a fluid-filled uterus and rules out pregnancy (Fig. 57-11; see also Fig. 56-9). Neutrophilia with a shift toward immaturity (band neutrophils), monocytosis, and evidence of WBC toxicity are the most common findings on the CBC. The left shift (band neutrophils) is the single most sensitive test to differentiate pyometra from mucometra. Animals with pyometra may have a total WBC count as high as 100,000 to 200,000/μl, or there may be a leukopenia with a degenerative left shift. A mild normocytic, normochromic, nonregenerative anemia is usually also evident. Biochemical abnormalities are common, but nonspecific for pyometra. They include hyperproteinemia, hyperglobulinemia, and azotemia. Occasionally, alanine aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase activities are mildly to moderately increased. Urinalysis findings include isosthenuria and/or proteinuria in one third of the bitches with pyometra. Bacteriuria is common.

FIG 57-11 Sonogram of pyometra. L, Fluid-filled uterine lumen; W, uterine wall; arrow, endometrial cysts.

There is often a prerenal component to the azotemia. Most bitches and queens with pyometra are middle-aged or older and may have preexisting renal disease. Additionally, azotemia, proteinuria, and isosthenuria are often a direct result of the pyometra and are potentially reversible once the uterine infection is resolved. Immune complex glomerulonephritis is thought to be the cause of pyometra-induced azotemia and proteinuria. Even without overt azotemia, it has been shown that most (75%) bitches have decreased glomerular filtration rates as determined by ioxhexol clearance. The decreased glomerular filtration rate is demonstrable irrespective of age, indicating that pyometra, not solely preexisting renal disease, is a factor. The complete pathophysiology of the isosthenuria and polyuria has not been elucidated. It has been demonstrated that the ability to secrete vasopressin is not diminished in these animals but that the renal tubules of bitches with pyometra do not respond adequately to vasopressin. It is thought that bacterial endotoxin interferes with renal tubular response. Vaginal cytology reveals a septic exudate, sometimes containing endometrial cells (see Fig. 57-1). Results of bacterial culture and sensitivity testing of the uterine exudate identify the offending organism and the appropriate antibiotic therapy.

The most important alternate diagnosis for pyometra is pregnancy. Both conditions occur during the diestrous stage of the cycle. A modest mature neutrophilia, mild anemia, and hyperglobulinemia normally occur during pregnancy. Pregnant animals are not always healthy, and the presence of a septic vulvar discharge does not preclude the possibility of co-existent pregnancy. Uterine infection during pregnancy does not invariably result in the death of all fetuses. Even in the event of overt abortion, the entire litter is not always lost. The owner’s goals of treating an ill pregnant animal may be quite different from the goals of treating one with pyometra.

Treatment

Treatment of pyometra must be prompt and aggressive if the animal’s life is to be saved. Septicemia, endotoxemia, or both can develop at any time if they do not already exist. Uterine rupture also sometimes occurs. Intravenous fluid therapy is indicated to correct existing deficits, maintain adequate tissue perfusion, and improve renal function. Very aggressive fluid therapy will be needed for animals in septic shock. Even if they survive ovariohysterectomy, postoperative mortality is higher in bitches when blood pressure and urine output remain low than among those in which fluid therapy corrected hypotension and increased urine output. Whether or not they are septic, the prognosis for survival is worse when azotemia cannot be resolved before ovariohysterectomy. Appropriate antibiotic therapy should be instituted as soon as possible. Pending the culture results, an antibiotic that is typically effective against E. coli, the organism most commonly isolated from pyometra, could be considered. These include enrofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfa, and amoxicillin-clavulanate. Ovariohysterectomy is the treatment of choice for pyometra in bitches and queens. Despite appropriate supportive and surgical treatment, morbidity of 3% to 20% and mortality of 5% to 28% are reported. This is not unexpected, given the serious metabolic derangements caused by pyometra. Barring complications resulting from the disease itself, surgery, or anesthesia, ovariohysterectomy is curative.

Nonsurgical Treatment of Pyometra

Whether surgical or nonsurgical treatment is chosen, the needs for fluid and antibiotic support must be addressed. The justifications for the medical, rather than surgical, treatment of pyometra are the owner’s desire for offspring from the affected female and the health of the animal. Although medical management may effectively resolve the clinical illness and preserve the potential for future litters, unlike ovariohysterectomy, medical management of pyometra is not curative. Pyometra can be expected to recur. Recurrence is more common in bitches than in queens because bitches will have progesterone stimulation, the factor initiating pyometra, for at least 60 days after every cycle. Queens, on the other hand, are under the influence of progesterone only after copulation-induced ovulation or, less commonly, after spontaneous ovulation. Recurrence rates of 20% to 25% after the next estrus, 19% to 40% by 24 months, and 77% by 27 months after nonsurgical treatment of pyometra are reported for bitches. Recurrence rates of 7% to 15% are reported for queens. Some of the animals in these reports successfully became pregnant before pyometra recurred, whereas others did not. Because reproductive performance is limited by recurrence, the desired number of offspring should be obtained as soon as possible. Breeding to a fertile male during the first posttreatment estrus is recommended. Although there are reports of successful medical treatment of recurrent pyometra in bitches and queens, ovariohysterectomy, rather than repeated attempts at medical management, is usually recommended.

The other important consideration for medical, as opposed to surgical, treatment of pyometra is the animal’s health. Medical treatments take days to weeks to rid the animal of the infected uterine contents, whereas ovariohysterectomy accomplishes this in a matter of hours. Surgery is the better choice for critically ill animals. Response to medical treatment is much better in animals with open-cervix pyometra than in those with a closed cervix. Unless the cervix dilates during treatment of closed-cervix pyometra, treatment will fail. There is a greater risk of uterine rupture. For these reasons ovariohysterectomy should be considered for animals with closed-cervix pyometra even if they are not critically ill.

A variety of luteolytic and uterotonic drugs are used to treat pyometra. Luteolysis is important to stop continued progesterone production. Myometrial contractions are necessary to expel the uterine contents. Dopamine agonists such as bromocriptine and cabergoline suppress luteal activity by suppressing prolactin, which is luteotropic in bitches. Prostaglandins, such as prostaglandin F2α and cloprostenol, cause luteolysis via apoptosis, and they also cause myometrial contractions. Competitive antagonists of the progesterone receptor, such as aglepristone, block the effects of progesterone, and this results in cervical dilation and uterine contractions. Women who might be pregnant should handle all these drugs with great care. These drugs have been used alone and in combination with each other according to a variety of protocols that have been designed to minimize side effects and take advantage of their different modes of action. Treatment is continued until the uterus is empty, which is typically 7 to 14 days. During treatment the vaginal discharge is expected to increase as the uterus empties, and the animal’s clinical condition and laboratory abnormalities are expected to improve. If the clinical status worsens during medical treatment, ovariohysterectomy should be performed instead. Ovariohysterectomy can be considered at any time during medical treatment of pyometra if the condition is not improving as expected. Some of the treatment protocols are summarized in Box 57-2. These drugs are not labeled for use in dogs or cats in the United States at this time, although veterinary preparations are available in many other countries.

BOX 57-2 Nonsurgical Treatment of Pyometra

BOX 57-2 Nonsurgical Treatment of Pyometra

SC, Subcutaneous; PO, oral.

All treatments are “to effect,” as described in the text:

Note: Several drug dosages are given in micrograms, μg

Cabergoline and Cloprostenol

Adverse reactions are common in animals receiving PGF2α (Lutalyse®, Pfizer) therapy and include panting, salivation, emesis, defecation, urination, mydriasis, and nesting behavior. Intense grooming behavior and vocalization may also be seen in the queen. Adverse reactions usually develop within 5 minutes of PGF2α administration and last for 30 to 60 minutes. The severity of reactions is directly related to the dose administered and inversely related to the number of days of therapy. Adverse reactions tend to become milder with subsequent injections. Fewer side effects are reported for cloprostenol (Estrumate®, Schering-Plough), but gastrointestinal signs still occur in 30% to 54% of bitches given the drug. Gastrointestinal signs are the most common side effect of cabergoline (Galastop®, Ceva Vetem; Dostinex®, Pfizer). The only side effect reported for Aglepristone (Alizine®, Virbac) is transient pain or swelling at the injection site. Massaging the injection site to help disperse the drug can minimize this reaction. The posttreatment interestrous interval is shortened by 1 to 3 months by all of these drugs.

Pregnancy rates of 80% to 90% are reported for bitches that have received PGF2α therapy for open-cervix pyometra, whereas pregnancy rates are only 25% to 34% in bitches with closed-cervix pyometra. Pregnancy rates of 70% to 90% are reported for queens after PGF2α treatment for open-cervix pyometra. The successful treatment with PGF2α of closed-cervix pyometra in queens has apparently not yet been reported in the English-language literature. Other studies have focused more on survival of the animals than on subsequent fertility. In these studies success was defined as the resolution of clinical illness, absence of intraluminal uterine fluid, and return of uterine horn diameter to normal as assessed by ultrasound. Treatment with a combination of cloprostenol and cabergoline for 7 to 14 days was considered successful in 24 of 29 bitches (83%) with open-cervix pyometra when the bitches were evaluated at 14 days (Corrada et al., 2006). The other five bitches were spayed at 14 days. Only two of the successfully treated bitches were subsequently bred, and one conceived. Six of the bitches (25%) had a recurrence of pyometra after the first posttreatment estrus. Treatment with combinations of cloprostenol and aglepristone for 8 to 15 days was successful in 60% to 75% of bitches (n = 15) with open-cervix pyometra when the bitches were evaluated at 15 days, and all 15 bitches had returned to normal by 29 days (Gobello et al., 2003). Three of the 15 remaining bitches (20%) had a recurrence of pyometra after the first posttreatment estrous cycle. Only one bitch was mated, and she did conceive.

Fieni (2006)studied the efficacy of aglepristone given alone on days 1, 2, and 8 or in combination with cloprostenol on days 3 through 7 in 52 bitches with pyometra. Aglepristone caused the cervix to open within 4 to 48 hours (mean = 26 hours) in all 17 of the bitches with closed-cervix pyometra. The animals’ clinical condition improved immediately thereafter. Treatment of pyometra with the combination of aglepristone and cloprostenol was more successful (84%) than was treatment with aglepristone alone (60%). Five bitches were mated during the first posttreatment estrus, and 4 (80%) became pregnant. Two bitches that did not respond to treatment died 5 and 15 days later. Of the successfully treated bitches, 13% had recurrence of pyometra by 12 months after treatment and 19% had recurrence by 24 months after treatment. Treatment was successful even when serum concentrations of progesterone were already below 1 ng/ml at the onset of treatment. This would support the concept that the pathogenesis of pyometra is related to the interactions of progesterone with progesterone receptor and not solely to high serum concentrations of progesterone. The absence of side effects and the rapidity with which aglepristone caused cervical dilation in bitches with close-cervix pyometra suggest that aglepristone may be beneficial in presurgical stabilization of bitches undergoing ovariohysterectomy for pyometra. This possibility deserves further study.

Arora N, et al. A model for cystic endometrial hyperplasia/pyometra complex in the bitch. Theriogenology. 2006;66:1530.

Barsanti J. Genitourinary infections. In Greene C, editor: Infectious diseases of the dog and Cat, ed 3, St Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2006.

Cerundolo R, et al. Identification and concentration of soy phytoestrogens in commercial dog foods. Am J Vet Res. 2004;65:592.

Chen Y, et al. The roles of progestagen and uterine irritant in the maintenance of cystic endometrial hyperplasia in the canine uterus. Theriogenology. 2006;66:1537.

Corrada Y, et al. Combination dopamine agonist and prostaglandin agonist treatment of cystic endometrial hyperplasia-pyometra complex in the bitch. Theriogenology. 2006;66:1557.

Davidson A, editor. Clinical theriogenology. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2001;31:2.

De Bosschere H, et al. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia-pyometra complex in the bitch: should the two entities be disconnected? Theriogenology. 2001;55:1509.

De Bosschere H, et al. Estrogen-α and progesterone receptor expression in cystic endometrial hyperplasia and pyometra in the bitch. Anim Reprod Sci. 2002;70:251.

Dhaliwal G, et al. Oestrogen and progesterone receptors in the uterine wall of bitches with cystic endometrial hyperplasia/pyometra. Vet Rec. 1999;145:455.

Eckert L. Acute vulvovaginitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1244.

Faldyna M, et al. Immunosuppression in bitches with pyometra. J Small Anim Pract. 2001;42:5.

Fantoni D, et al. Intravenous administration of hypertonic sodium chloride solution with dextran or sodium chloride solution for treatment of septic shock secondary to pyometra in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1999;215:1283.

Fieni F. Clinical evaluation of the use of aglepristone, with or without cloprostenol, to treat cystic endometrial hyperplasia-pyometra complex in bitches. Theriogenology. 2006;66:1550.

Fransson B, et al. C-reactive protein in the differentiation of pyometra from cystic endometrial hyperplasia/mucometra in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2004;40:391.

Gobello C, et al. A study of two protocols combining aglepristone and cloprostenol to treat open cervix pyometra in the bitch. Theriogenology. 2003;60:901.

Hagman R, et al. Differentiation between pyometra and cystic endometrial hyperplasia/mucometra in bitches by prostaglandin F2α metabolite analysis. Theriogenology. 2006;66:198.

Hammel S, et al. Results of vulvoplasty for treatment of recessed vulva in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2002;38:79.

Heiene R, et al. The relationship between some plasma clearance methods for estimation of glomerular filtration rate in dogs with pyometra. J Vet Intern Med. 1999;13:587.

Heiene R, et al. Vasopressin secretion in response to osmotic stimulation and effects of desmopressin on urinary concentrating capacity in dogs with pyometra. Am J Vet Res. 2004;65:404.

Johnston S, et al, editors. Canine and feline theriogenology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001.

Kida K, et al. Lactoferrin expression in the canine uterus during the estrous cycle and with pyometra. Theriogenology. 2006;66:1325.

Lightner B, et al. Episioplasty for the treatment of perivulvar dermatitis or recurrent urinary tract infection in dogs with excessive perivulvar skin folds: 31 cases (1983-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;219:1577.

Lulich J. Endoscopic vaginoscopy in the dog. Theriogenology. 2006;66:588.

Misumi K, et al. Uterine torsion in two non-gravid bitches. J Small Anim Pract. 2000;41:468.

Niskanen M, et al. Associations between age, parity, hormonal therapy and breed, and pyometra in Finnish dogs. Vet Rec. 1998;143:493.

Ortega-Pacheco A, et al. Reproductive patterns and reproductive pathologies of stray bitches in the tropics. Theriogenology. 2007;67:382.

Ridyard A, et al. Successful treatment of uterine torsion in a cat with severe metabolic and homeostatic complications. J Feline Med Surg. 2000;2:115.

Sobel J. Vaginitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1896.

Ström-Holst B. Characterization of the bacterial population of the genital tract of adult cats. Am J Vet Res. 2003;64:963.

Ververidis H, et al. Serum estradiol-17β, progesterone and respective uterine cytosol receptor concentrations in bitches with spontaneous pyometra. Theriogenology. 2004;62:614.

Wang K, et al. Vestibular, vaginal, and urethral relations in spayed dogs with and without lower urinary tract signs. J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20:1065.