CHAPTER 6 Voiding disorders and bladder outlet obstruction

INTRODUCTION

Due to the high prevalence of bladder outflow obstruction (BOO) secondary to benign (and malignant) prostatic disease, voiding difficulties are the commonest reason for men to present to a urologist. However, recent evidence shows that a large population of men have a storage disorder such as OAB either as a primary diagnosis or secondary to BOO. Since, voiding disorders frequently are associated with storage LUTS such as nocturia and daytime frequency, this may well lead to a confusing mix of symptoms. With this in mind, men with LUTS should not be assumed to have a voiding disorder/prostatic disease and if there is any doubt as to the diagnosis then pressure/flow cystometry is necessary to differentiate definitively between voiding and storage disorders.

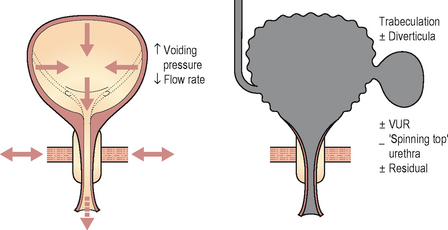

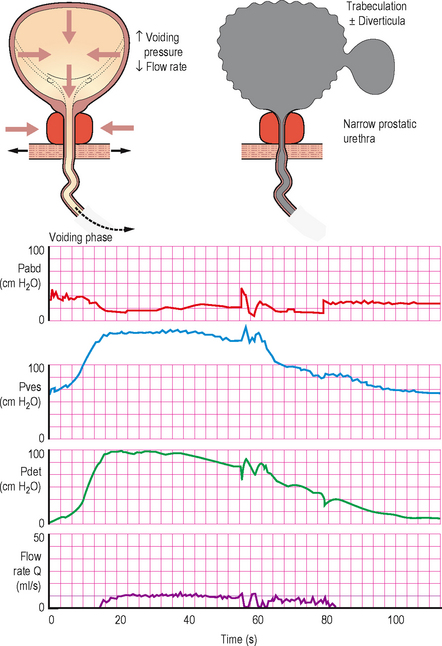

Figure 6.4 Typical cystometry appearances for bladder outlet obstruction. In this case the screening schematic shows obstruction at the level of the prostate.

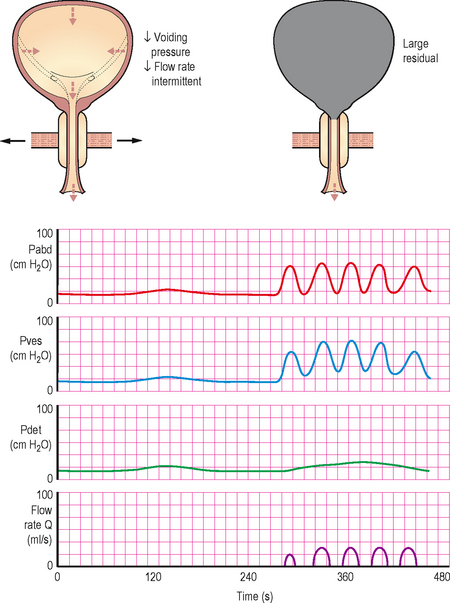

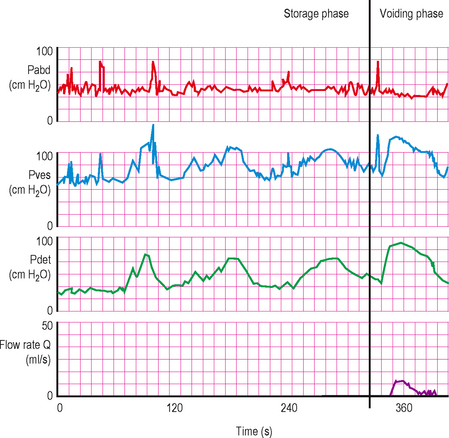

Figure 6.5 Pressure/flow trace in patient with both detrusor overactivity during filling and BOO during voiding. This is a common pattern as many patients have both conditions coexisting.

Causes of voiding difficulty in men are:

Voiding difficulty is far less common in females and when it occurs it should be thoroughly investigated with anatomical and functional investigations. Most female patients with voiding difficulty have a neuropathic disorder affecting the bladder, but a functional obstruction of the bladder outlet/urethra or detrusor muscle failure must be excluded. Causes of voiding difficulty in women are:

ANATOMICAL BLADDER OUTLET OBSTRUCTION

Bladder outflow obstruction (BOO) is a generic term for obstruction during voiding, and is characterized by increased detrusor pressure and reduced urine flow rate. It is usually diagnosed definitively during pressure/flow cystometry although history, physical evaluation and simple urodynamic tests (voiding diaries, uroflowmetry and PVR) often point to the correct diagnosis; the majority of patients do not receive pressure/flow cystometry until initial treatment has failed, or if there are other complicating factors.

Most patients present with predominant voiding LUTS, but some present with complications of the BOO including:

Benign prostatic obstruction

TERMINOLOGY: ENLARGEMENT OF THE PROSTATE

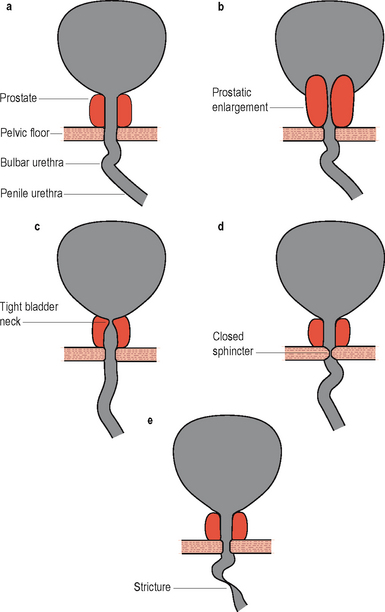

Figure 6.1 Screening appearances of bladder outlet obstruction. (A) Normal appearance of male lower urinary tract during voiding. (B) Prostatic obstruction: lengthening and thinning of prostatic urethra, prostatic indentation of the bladder neck. (C) Bladder neck obstruction: bladder neck shut or narrow during voluntary voiding contraction. (D) DSD: Narrow membranous urethra, bulging of prostatic urethra. (E) Urethral stricture.

Prostatectomy (usually trans-urethral prostatectomy [TURP]). Usage has declined in recent years due to the efficacy of medications in reducing symptoms and preventing progression. A variety of methods of performing prostatectomy or ablation of the prostate gland have been described including high intensity ultrasound, microwave thermotherapy, needle ablation, electro-vaporization and laser therapy. Open retropubic prostatectomy is also used in particularly large prostates where the open operation is quicker and safer than TURP. Prostatectomy is more successful in patients with demonstrable BOO on pressure/flow cystometry than in patients without documented obstruction

Prostatectomy (usually trans-urethral prostatectomy [TURP]). Usage has declined in recent years due to the efficacy of medications in reducing symptoms and preventing progression. A variety of methods of performing prostatectomy or ablation of the prostate gland have been described including high intensity ultrasound, microwave thermotherapy, needle ablation, electro-vaporization and laser therapy. Open retropubic prostatectomy is also used in particularly large prostates where the open operation is quicker and safer than TURP. Prostatectomy is more successful in patients with demonstrable BOO on pressure/flow cystometry than in patients without documented obstructionCatheterization to drain the bladder either with an indwelling catheter or CISC may be required in patients who are refractory to conservative or medical treatments and also in those who are not fit or are unwilling to undergo an invasive procedure.

CLINICAL NOTE: BENIGN PROSTATIC DISEASE

Malignant prostatic obstruction

Benign and malignant prostatic diseases often co-exist, but the relationship appears to be coincidental, although both conditions are under the influence of the male hormone testosterone:

Prostatic carcinoma must be ruled out in middle-aged and elderly men who present with storage or voiding LUTS, if carcinoma is discovered then it must be treated appropriately depending on the grade and stage of the disease and the medical condition of the patient, as per relevant guidelines. Initial screening during assessment of LUTS is usually with digital rectal examination (DRE) and serum prostate specific antigen (PSA); followed by trans-rectal ultrasound and prostatic biopsy if there is any suspicion of carcinoma.

Bladder neck obstruction

In this condition the bladder neck does not open completely during voiding and there is little or no flow during a well sustained detrusor contraction. Video urodynamics is necessary in order to make the diagnosis (Figure 6.1c). The condition is especially prevalent in younger men and also occurs occasionally in women; currently the aetiology of primary bladder neck obstruction is unknown. Theories for the cause include fibrosis, neurogenic dysfunction (detrusor/bladder neck dyssnergia) and smooth muscle hypertrophy, amongst others. On screening there may be trapping of contrast during the stop test (Figures 4.20 and 6.2).

Figure 6.2 Bladder neck obstruction/dyssynergia, showing trapping of contrast in the prostatic urethra during a stop test. During voiding the patient is instructed to stop his urinary stream: normally the contrast located in the prostatic urethra quickly milks back into the bladder; however, in patients with bladder neck dyssynergia, the tighter bladder neck resists retrograde flow, resulting in ‘ballooning’ of the prostatic urethra.

Urethral stricture

Urethral strictures can occur in men of all ages and symptoms tend to only become evident when the urethral calibre is reduced to below 11 Fr. Strictures prevent the urethra from expanding and cause a characteristic constrictive picture on uroflowmetry (Figure 3.4e).

Causes of urethral stricture include:

Although pressure/flow cystometry is useful in confirming BOO, more useful investigations include urethrography and cystoscopy which provide an anatomical assessment of the stricture (Figure 6.1e). Treatment is essentially surgical, usually with urethrotomy for simple short strictures or a urethroplasty for long, complex or recurrent strictures. Patients may require temporary bladder drainage via a catheter whilst awaiting surgery or if the surgery fails. Urethral dilatation is also helpful in keeping the urethra patent both prior to and following surgery.

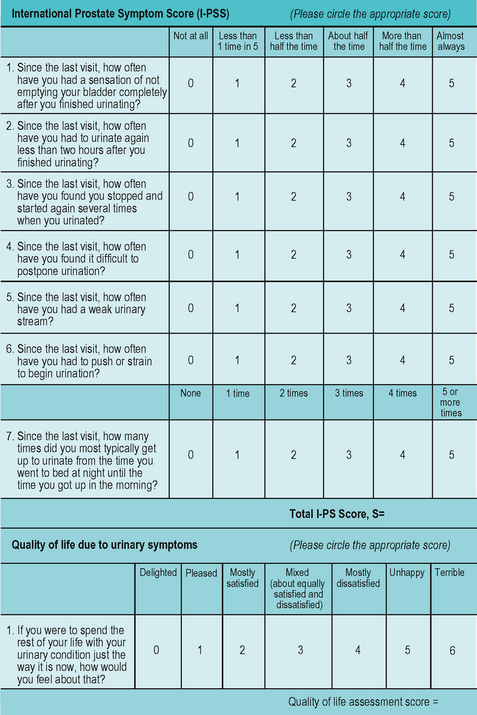

Evaluation of suspected BOO

Initial evaluation of anatomical bladder outlet obstruction includes:

Figure 6.3 International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS). This questionnaire is commonly used in the assessment of benign prostatic disease.

Further investigations should be performed if indicated including (but not limited to):

Indications for urodynamics to assess BOO

Voiding diaries

Helpful in quantifying the symptoms of urgency, frequency and nocturia which are commonly associated with BOO and also occur in storage disorders such as OAB. May also be useful in ruling out suspected nocturnal polyuria particularly when the patient complains of significant nocturia (see Chapter 3).

Uroflowmetry and PVR

Can be used as a screening tool, and in most cases this is all that is required to confirm the presence of BOO (although it can’t rule out a poorly contractile detrusor) before instigating treatment. In addition, it is a simple non-invasive test that can be used for subsequent monitoring following therapy. Urethral strictures produce a characteristic pattern (Fig. 3.4e), due to the constrictive obstruction, which may aid in making the diagnosis of stricture disease.

Pressure/flow cystometry

During voiding abnormally high pressures accompanied by a poor and prolonged urinary flow are characteristic of BOO. Cystometry is particularly useful in equivocal patients where it is necessary to rule out a detrusor cause for the LUTS, such as detrusor overactivity during the storage phase, or another cause for the dysfunctional voiding such as detrusor underactivity during the voiding phase. It is also important that any patient who is being considered for further surgery after initial failed surgery undergoes pressure/flow cystometry, both to confirm the symptoms are indeed due to BOO and to determine if any other complicating pathology is present such as DO.

Video urodynamics

This is the ‘gold standard’ investigation. Not only is all the information obtained as for pressure/flow cystometry but the added radiological screening allows the level of the obstruction to be determined. Enlargement of the prostate may be seen as a reduced calibre of the prostatic urethra and also as a prostatic indentation at the bladder base. Trapping of urine in the prostatic urethra due to bladder neck obstruction may also be visible during the stop test (Fig 6.2). Chronic changes to the bladder such as trabeculation and diverticula, as well as vesico-ureteric reflux during the high pressures generated by the bladder during voiding may also be seen (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 Possible findings during urodynamic testing of patients with BOO

| Possible findings during urodynamic testing of patients with BOO | |

|---|---|

| Voiding diaries | |

| Uroflowmetry and PVR | |

| Pressure/flow cystometry (Figures 6.4 and 6.5) | |

| Video urodynamics | |

URODYNAMICS IN PRACTICE: PROSTATIC OBSTRUCTION

Interpreting pressure/flow cystometry in BOO

It is usually obvious during the voiding phase of a pressure/flow urodynamic investigation that BOO is present. Many experts regard patients with a detrusor pressure >60 cm H2O associated with a Qmax <10 mL/s to be urodynamically obstructed. The detrusor pressure often reaches abnormally high levels (approaching or greater than 100 cm H2O) in an attempt to expel the urine through the obstruction. Yet the flow rate remains low (often less than 8 ml/s) despite the elevated pressures (high pressure, low flow).

However in many cases the findings are more equivocal such as when:

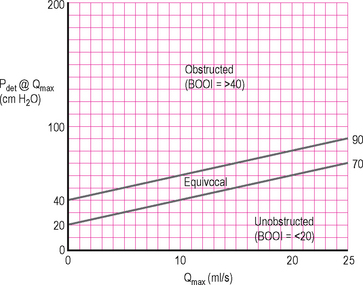

To aid in determining if BOO is present the ICS pressure/flow nomogram can be used to calculate the bladder outlet obstruction index (BOOI) by plotting Qmax against Pdet@Qmax. This will then categorize patients as being obstructed, unobstructed or equivocal. The ICS nomogram is based on a number of older nomograms (Abrams–Griffiths, Schafer LinPURR and URA nomograms) which were all found to have a high degree of correlation with each other; therefore only the ICS nomogram is required in routine clinical practice (Figure 6.6).

Figure 6.6 ICS BOO nomogram. Allows the BOOI to be easily calculated and the patient categorized as obstructed, unobstructed or equivocal. Must adjust for flow rate delay before using nomogram.

Modern urodynamic software usually contains the nomogram and will plot the data automatically; however if the nomogram is unavailable the BOOI (previously called the Abrams–Griffiths (AG) number) can be easily calculated manually using the following formula:

BOOI between 20 to 40 = equivocal.

When using the nomogram and/or calculating the BOOI it must be remembered that the flow rate delay must be corrected for when calculating the Pdet@Qmax, and this will depend on the local characteristics of the equipment (Chapter 4). It must also be borne in mind that the nomogram/BOOI was developed to assess male BOO due to a presumed prostatic cause. The nomogram and BOOI may therefore not be applicable in other situations such as in men with a functional obstruction (dyssynergia) and is not appropriate for women.

FUNCTIONAL OBSTRUCTION (DYSSYNERGIA)

During normal voiding the urethra relaxes synchronously with contraction of the detrusor muscle. Should the urethra and in particular its associated sphincter mechanisms fail to relax during voiding then uncoordinated activity between the detrusor and the urethra/sphincter occurs; this is termed dyssynergia. The ICS has defined a number of patterns of functional obstruction:

Dysfunctional voiding

‘An intermittent and/or fluctuating flow rate due to involuntary intermittent contractions of the peri-urethral striated muscle during voiding, in neurologically normal patients’. The condition occurs most frequently in children and it is thought to be due to intermittent pelvic floor contractions. (The old term for this was ‘non-neurogenic, neurogenic bladder’.) Poor relaxation of the pelvic floor and urethral sphincter mechanism is also common in patients with voiding dysfunction, especially those with pelvic pain syndrome.

Detrusor sphincter dyssnergia (DSD)

‘A detrusor contraction concurrent with an involuntary contraction of the urethral and/or peri-urethral striated muscle’ (Figure 6.1c). The condition tends to occur in patients with a supra-sacral neurological lesion, for example a spinal cord injury, Parkinson’s disease and also multiple sclerosis (MS) (see Chapter 9). Co-existing DSD and prostatic obstruction can occur in elderly men such as those with Parkinson’s disease and can be particularly difficult to manage. A useful therapeutic manoeuvre in such a situation can be to insert a temporary intra-urethral prostatic stent to treat the prostate obstruction, thus allowing the two conditions to be differentiated.

Non-relaxing urethral sphincter obstruction

‘A non-relaxing, obstructing urethra resulting in reduced urine flow’ tends to occur in patients with a sacral or infra-sacral neurological lesion, i.e. meningomyelocoele or following radical pelvic surgery which has damaged the innervation.

Fowler’s syndrome

This is an uncommon condition that primarily affects young women in their 20–30s, in whom the urethral sphincter mechanism fails to relax leading to raised PVRs and retention. There may be a history of lifelong voiding difficulty and often there is associated secondary detrusor failure. Many of these women have an associated hormonal problem (Stein–Leventhal syndrome – hirsutism, polycystic ovary syndrome and amenorrhoea). The aetiology is unknown and the gold standard investigation for this condition is a sphincter electromyogram (EMG), although pressure/flow cystometry, urethral pressure profilometry and ultrasound sphincter volume measurement may also be valuable. Some women may spontaneously recover whilst in others it may be a lifelong condition. CISC may be required to ensure adequate bladder drainage although it is poorly correlated and sacral neuromodulation has also been found to be of some benefit in restoring voiding.

Evaluation of suspected functional obstruction

The brief descriptions given above should be borne in mind when evaluating any patient who has outflow obstruction. Associated neurological symptoms and signs should suggest the possibility of DSD or a non-relaxing urethral sphincter obstruction.

These conditions are best evaluated using video urodynamics with synchronous use of electromyography and should ideally be performed in units with specialist expertise in investigating and managing these conditions.

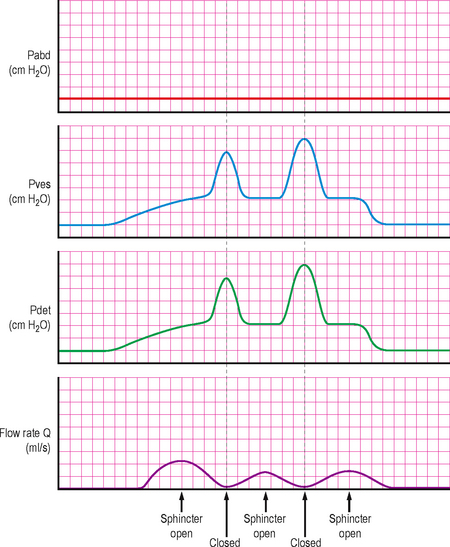

Urodynamic findings in functional obstruction

Urodynamic findings are similar to those seen in anatomical BOO and are characterized by high detrusor pressures coupled with poor flow. With DSD the sphincter may intermittently open and close during voiding. When the sphincter is open the detrusor pressures may be normal or moderately high. If the sphincter suddenly closes during a void the detrusor pressure rises because the detrusor is now iso-volumetrically contracting against the closed sphincter (similar to a stop test); the flow rate will also reduce/stop whilst the sphincter is closed. When the sphincter re-opens the detrusor pressures will drop and the flow will be re-established. This pattern may be repeated a number of times during a void (Figure 6.7).

Figure 6.7 Typical trace in DSD, showing intermittent opening and closure of the urethral sphincter causing a characteristic flow pattern and pressure changes.

Video urodynamics will also show the intermittent sphincter activity and the level of the obstruction. In addition the bladder may develop chronic changes due to the elevated voiding pressures including trabeculation, diverticula and vesico-ureteric reflux (most noticeable when the sphincter closes, causing a significant rise in detrusor pressure). The bladder and urethra in females may develop a ‘spinning top’ appearance due to widening of the posterior urethra due to the chronic high pressure trapping of urine in the urethra above the sphincter when the sphincter closes (Figure 6.8). EMG studies concurrent with pressure/flow cystometry may also show intermittent sphincteric activity during voiding.

DETRUSOR FAILURE (UNDERACTIVE DETRUSOR FUNCTION)

In addition to anatomical or functional obstruction to urine outflow, detrusor failure can also cause voiding dysfunction in both men and women.

Poor detrusor function during voiding can be classified as:

Causes of detrusor failure include:

Frequently patients present with chronic retention ± overflow incontinence, but detrusor failure should be considered in all patients who present with voiding difficulty. A uroflowmetry and PVR estimation is a good screening tool for the condition. An intermittent straining pattern or sometimes a prolonged, low flow rate void associated with a raised PVR should raise suspicions of detrusor failure (although a similar picture is frequently seen with BOO). However, only pressure/flow cystometry can definitively differentiate between BOO and detrusor failure and should therefore be performed in all equivocal cases, especially if the PVR is abnormally raised.

Chronic retention

This is a non-painful distended bladder, which remains palpable or percussable after the patient has passed urine.

Elderly men in particular are at risk of developing chronic retention secondary to BOO, but any of the causes of detrusor failure may lead to chronic retention. Often the cause of the chronic retention is unknown (idiopathic). A small group of middle-aged to elderly women present with acute retention of urine, usually after surgery and commonly vigorously deny any previous history of voiding difficulty. In addition, some women report ‘chronic holding’ either due to busy schedules or in an attempt to avoid public restrooms. Urodynamic investigation sometimes demonstrates an underactive detrusor with chronic retention in this distinct group.

Management of detrusor failure

Initial

The initial management of underactive detrusor is aimed at ensuring that the bladder is adequately drained, thus preventing over-distension of the bladder and overstretching of the detrusor muscle fibres leading to further damage; and also preventing the development or worsening of damage to the upper urinary tracts.

Long term

The long term management of detrusor underactivity is directed at the correction of any underlying aetiology, if possible. If the underlying cause is adequately treated and the bladder is allowed a period of ‘rest’ with suitable drainage then there may be some recovery of detrusor function. Bladder training can also be useful, particularly for the ‘infrequent voiders’ who are instructed to void by the clock (e.g. 2-hourly).

In a man with detrusor failure secondary to prostatic BOO a period of drainage may allow detectable function to return; in such a situation proceeding to prostatic surgery may be appropriate, whereas if there is no improvement in detrusor function then the voiding symptoms are unlikely to resolve and the man is likely to continue to need the bladder draining artificially following prostatic surgery.

Urodynamics in detrusor failure

Uroflowmetry and PVR

A useful screening and monitoring tool. A prolonged flow is usually seen along with a low Qmax. Often the flow is intermittent and the patient may be attempting to void with abdominal straining. The PVR will be consistently raised (usually above 200–300 ml). The flow rate pattern is similar to the pattern seen in BOO and it is impossible to be sure if voiding dysfunction is due to detrusor failure or BOO on the basis of this test. Though an elevated PVR suggests decompensation and relative underactivity of the detrusor, and not BOO.

Pressure/flow cystometry

This is able to determine if detrusor underactivity is present. During the storage phase the bladder may be hypo-sensitive with late bladder sensations detected and a high cystometric capacity. The patient may not demonstrate a strong desire to void and so may not have a measurable maximum cystometric capacity. In such cases the cystometric capacity (at which filling is stopped) may need to be determined by the investigator. On being given permission to void the patient often has a long delay before initiating the void. The detrusor pressure only rises minimally (or not at all if acontractile) with a corresponding low flow rate (low pressure, low flow voiding). Often the patient has to perform abdominal straining to initiate or maintain a void. Frequently only a negligible amount of fluid is voided (Figure 6.9).

Video urodynamics

This is useful to determine if there is any reflux of contrast at any point during the study and may also show hydronephrosis if there is any upper tract damage. Video urodynamics is therefore particularly important in patients with suspected neurogenic dysfunction. If sufficient contrast is voided then it may be possible to see the level of obstruction if the detrusor failure is secondary to BOO; although in many cases this is not possible due to the negligible volume voided.

URODYNAMICS IN PRACTICE: DETRUSOR FAILURE AND OUTLET RESISTANCE

It must be remembered that a normal detrusor contraction will be recorded as:

Therefore patients with apparent detrusor underactivity may have a very low outlet resistance, as may occur if the sphincteric mechanisms are grossly incompetent.

A patient with a very low outlet resistance is likely to experience stress incontinence during the filling phase.