3 Occupational performance and adaptation models

This chapter includes a number of models that address occupational therapy from the perspective articulated most prominently in North America. While occupational therapy grew out of both British and North American movements, the way that occupational therapy has been conceptualized in North America has had a widespread influence on theory throughout the world. While a number of different occupational performance models had been developed in different Western countries (e.g. the Canadian Occupational Performance Model (OPM) (DNHW & CAOT, 1983)), two have been selected to demonstrate different aspects of this approach. These are occupational performance models from the USA and Australia. The first two models presented in this chapter are the Occupational Performance (OP) model (Pedretti & Early, 2001), and with it the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) (AOTA, 2008), and the Occupational Performance Model (Australia) (OPMA) (Chapparo & Ranka, 1997). These models are most frequently, although not exclusively, used in physical rehabilitation practice because these models include a detailed focus on the body and its component capacities. In addition, a third model, the Occupational Adaptation (OA) model (first published: Schkade & Schultz, 1992), is presented.

These three models are presented together in this chapter because they particularly use the language of ‘science’. While this is evident in the two occupational performance models through their use of knowledge bases relating to the anatomy and physiology of the body, it is also evident in the extensive use of objective language (objectivity is highly valued in science) to label concepts in the Occupational Adaptation (OA) model. As discussed in the Introduction, over time the trend towards a more person-centred and less biomedical approach has characterized occupational therapy theory. Pedretti’s OP model and Chapparo’s and Ranka’s OPMA provide a good example of this shift in emphasis, in that OP is more consistent with a biomedical approach through its focus on the physical body and performance components and OPMA with a biopsychosocial approach, which emphasizes subjective experience in addition to performance components.

The term occupational performance has been used widely in a range of occupational therapy publications, particularly in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and was often used interchangeably with other terms. As Christiansen and Baum (1997) explained, “The terms function or functional performance are often used in the medical literature to describe the ability of an individual to accomplish tasks of daily living. In an American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) position paper, Baum and Edwards (1995) observed that, when occupational therapists in the United States use the term function, they refer to an individual’s performance of activities, tasks and roles during daily occupations (occupational performance)” (p. 5).

Occupational Performance Model

In this section, the Occupational Performance (OP) model, as articulated by Lorraine Williams Pedretti and her colleagues in the various editions of her well-known occupational therapy textbook, Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction (1981, 1985, 1990, 1996, 2001), is presented in detail in its most recent (2001) form. This model was chosen as a starting point for the chapter, because the concepts that are articulated in the model represent the way that occupational therapy was conceptualized in many Western countries over the course of the last century. Therefore, it is likely that many of the concepts in the model continue to influence occupational therapy theory and practice.

In this chapter, once the Occupational Performance model, as it was presented by Pedretti and Early (2001), has been outlined, more recent developments are discussed in a section on the historical description of the model’s development. These include the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF), first published in 2002 by the AOTA and now in its second edition (AOTA, 2008). While there are a range of occupational therapy models and frameworks published in the area of physical dysfunction, the OP model and the OTPF are both presented here because they flowed from or were associated with the official position of the AOTA (much of the Canadian work is discussed in Chapter 5). Pedretti’s and Early’s (2001) statement, “occupational performance terminology [used in the model] was defined and standardized in official documents of the AOTA” (p. 4) demonstrates that the OP model encapsulated the officially accepted view of the domain of concern of occupational therapy by the American Occupational Therapy Association at the time.

Main concepts and definitions of terms

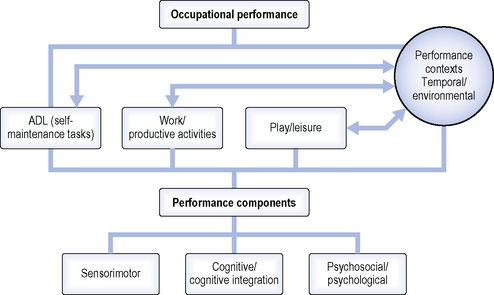

Lorraine Williams Pedretti is the author most closely associated with articulating the OP model. She did not claim to have authored this model but explained that some components of the model “have always been the core of OT” (Pedretti & Early, 2001, p. 4) and other details were added by committees and task forces of the American Occupational Therapy Association during the 1970s. The diagram (1996, 2001) (see Figure 3.1) used to represent the model acknowledges that it is based on the uniform terminology for occupational therapists, which was published in three editions by the AOTA and was succeeded by the OTPF. Throughout the description of this model, the term patient is used, as that is the term most often used in relation to this model. That is, the model used the term patient to refer to the subject of therapy, and for consistency, we do the same.

As the name suggests, the central aim in this model is to facilitate occupational performance. Occupational performance was defined as, “the ability to perform those tasks that make it possible to carry out occupational roles in a satisfying manner appropriate for the individual’s developmental stage, culture, and environment” (Pedretti & Early, 2001, p. 5). Pedretti defined occupational roles as “the life roles that an individual holds in society” (1996, p. 3). Occupational roles develop in conjunction with the occupations in which people engage and include roles such as “pre-schooler, student, parent, homemaker, employee, volunteer, or retired worker” (2001, p. 5). Thus, the purpose of occupational performance is to be able to fulfil occupational roles.

The development of occupational performance is dependent upon sufficient opportunities to practice and learn the skills and abilities required to fulfil occupational roles and developmental tasks. The model provides a framework for aiding occupational therapists to systematically analyze the nature of the problems that are reducing the occupational performance of an individual. It comprises three elements: performance areas, performance components and performance contexts. The diagram provides the details of each of these elements and how they relate to occupational performance. Problems can arise that interfere with occupational performance. These problems might stem from “deficits in task learning experiences, performance components, or impoverished performance contexts” (Pedretti & Early, 2001, p. 5).

The performance areas are the first of the three elements described by the authors. The model outlines three performance areas into which activities are grouped. These are activities of daily living (ADL), work and productive activities, and play or leisure activities. Pedretti and Early (2001) explained, “ADL include the self-maintenance tasks of grooming, hygiene, dressing, feeding and eating, mobility, socialization, communication, and sexual expression. Work and productive activities include home management, care of others, educational activities, and vocational activities. Play and leisure include play exploration and play or leisure performance in age-appropriate activities.” (p. 5.) It appears that, by explaining the performance areas first, their connection to occupational performance and occupational roles could be emphasized. In addition, Pedretti and Early stated, “intervention strategies must ultimately be directed to the patient’s achievement in performance areas when a performance component (e.g. motor skill development) is being addressed” (p. 6). This emphasizes that, while the performance components provide details for occupational therapists that are particularly useful in planning rehabilitation interventions, occupational therapy intervention is for the purpose of enhancing the occupational performance required by an individual in each of the performance areas.

Performance components are “the learned developmental patterns of behaviour which are the substructure and foundation of the individual’s occupational performance” (Pedretti & Early, 2001, p. 5). The components of performance are categorized in the following three groups: sensorimotor, cognitive and cognitive integration, and psychosocial and psychological components. According to this model, “adequate neurophysiological development and integrated functioning of the performance components are basic to an individual’s ability to perform occupational tasks or activities in the performance areas” (pp. 5–6). The sensorimotor component includes three types of functions. These are sensory, neuromusculoskeletal and motor functions. The cognitive integration and cognitive components relate to the ability to use higher brain functions. The psychosocial and psychological components include those abilities required for social interaction and emotional processing. The model provides substantial detail about the nature of these performance components. These details have been listed in Table 3.1 for clarity.

The third element in the OP model is called performance contexts. The model acknowledges that occupational performance is conducted in a variety of contexts. Therefore, in order to gain a detailed understanding of an individual’s occupational performance, occupational therapists need to know both how the abilities of the individual affect his or her performance and how the context in which occupations are performed influence that performance. Performance contexts are conceptualized as temporal and environmental. Pedretti and Early (2001) listed the following as examples of the temporal context: “the individual’s age, developmental stage or phase of maturation, and stage in important life processes such as parenting, education, or career… [and] disability status (e.g., acute, chronic, terminal, improving, or declining) must also be considered” (p. 6). These examples suggest that, in this model, the temporal contexts appear to relate primarily to the individual.

Environmental dimensions of the performance contexts are considered under the categories of physical, social and cultural. As Pedretti and Early stated, “The physical environment includes homes, buildings, outdoors, furniture, tools, and other objects. Social environment includes significant others and social groups. Cultural environment includes customs, beliefs, standards of behaviour, political factors, and opportunities for education, employment, and economic support” (p. 6).

Intervention

Underlying the model are two key approaches to facilitating occupational performance: remediation and compensation. In a remediation approach, intervention is targeted towards improving performance components, with the assumption that such improvements will lead to enhanced occupational performance in the performance areas. A compensatory approach is used when remediation is not considered achievable or feasible. According to Pedretti and Early (2001), the latter approach “focuses on remaining abilities and aims to improve function by adapting or compensating for performance component deficits” (p. 6). They proposed that examples of this approach might include adapting the methods used to perform tasks, providing assistive devices or modifying the environment.

The model outlines four levels of intervention. As the main focus of this model is remediation, the four levels primarily categorize methods that could be used for the remediation of problems in performance components. The levels in sequence are adjunctive methods, enabling activities, purposeful activity and occupations. They represent an intervention continuum that “takes the patient through a logical progression from dependence to occupational performance to resumption of valued social and occupational roles” (Pedretti & Early, 2001, p. 7). However, this continuum is not meant to be used in a strictly stepwise fashion and the various levels can overlap and be used simultaneously as required. Essentially, these intervention levels are based on the assumption that purposeful activity is the “primary treatment tool of occupational therapy” (p. 7) and that adjunctive methods and enabling activities are used as preparatory to functional activity in performance areas, rather than the aim of remediating problems in the performance components being an end in itself. As they stated, “exclusive use of such preparatory methods out of context of the patient’s occupational performance is not considered OT” (p. 7).

The first level of intervention is adjunctive methods. These are “procedures that prepare the patient for occupational performance but are preliminary to the use of purposeful activity” (p. 7). These methods generally focus on remediating performance components or maintaining structural integrity of body parts to prevent problems that could interfere with their potential use. They include methods such as “exercise, facilitation and inhibition techniques, positioning, sensory stimulation, selected physical agent modalities, and provision of devices such as braces and splints” (p. 7). Pedretti and Early (2001) emphasized that occupational therapists using these methods need to plan for progression to the subsequent intervention levels to ensure that adjunctive methods remain preparatory to purposeful activity.

The second level is enabling activities. This level involves the use of activities that might not be considered purposeful. Interventions at this level often involve simulation tasks, examples of which include “sanding boards, skate boards, stacking cones or blocks, practice boards for mastery of clothing fasteners and hardware, driving simulators, work simulators, and tabletop activities such as form boards for training in perceptual-motor skills” (Pedretti & Early, 2001, p. 7). These are often used when the requirements of purposeful activities are beyond the capabilities of patients. Essentially they represent graded activities that might enable patients to engage in activities for remediation and experience success, when purposeful activities would not be likely to result in this level of success. However, similar to adjunct methods, they need to be regarded as preparatory to purposeful activity. The primary goal of the first two levels of intervention is the remediation of performance components.

Pedretti and Early (2001) also included the use of equipment in this level. They listed equipment such as “wheelchairs, ambulatory aids, special clothing, communication devices, environmental control systems, and other assistive devices” (p. 7) as interventions at this level. It appears that their reason for including these devices here (rather than as environmental adaptations) could relate to purposeful activity being the main type of intervention proposed. As devices and equipment cannot be categorized as purposeful activity, they are probably conceptualized as tools for enabling performance, as are enabling activities. This approach appears to differ from some of the models presented in the following chapter, which present the environment as one of three primary intervention categories (i.e. person, environment, occupation).

The third intervention level is purposeful activity. Pedretti and Early (2001) emphasized that purposeful activity has always been at the core of occupational therapy. They defined purposeful activity as “activities that have an inherent or autonomous goal and are relevant and meaningful to the patient” (p. 8). It is the goal, relevance and meaningfulness to the patient that distinguishes this level from the second level, in which the activities chosen might have a goal that is meaningful to the occupational therapist but might not be evident to or valued by the client. The model assumes that activities become meaningful and purposeful to an individual because that individual needs them for functioning independently in their performance areas. Therefore, it is their contribution to the performance areas that makes activities purposeful.

At this level of intervention, purposeful activity is used for the purpose of “assessing and remediating deficits in the performance areas” (Pedretti & Early, 2001, p. 8). Thus, the focus is shifted to performance areas − compared with centring on performance components at the first two levels. Examples of the activities used are “feeding, hygiene, dressing, mobility, communication, arts, crafts, games, sports, work, and educational activities” (p. 8) and these could be conducted in the patient’s home, a community agency, or a healthcare facility.

The final level of intervention refers to occupations. This is the highest stage in the treatment continuum and involves engaging “the patient in natural occupations in his or her living environment and in the community. The patient performs appropriate tasks of ADL, work and productive activities, and play and leisure to his or her maximum level of independence.” (p. 9.) Because the core of this level is maximum independence and these activities are performed in their natural environments, active involvement in “scheduled OT” (p. 9) decreases to the point where it terminates and the individual “resumes and effectively performs valued occupational roles” (p. 9). The focus of this level of intervention moves to the performance of occupational roles within their natural context.

Pedretti and Early (2001) identified two “intervention approaches” (p. 10) that are valuable to use in conjunction with the OP model in the area of physical dysfunction. These are the biomechanical and motor control models. Each of these models provides principles for the treatment of movement problems caused by different processes. The biomechanical model “applies the mechanical principles of kinetics and kinematics to the movement of the human body. These mechanical principles deal with the way that forces acting on the body affect movement and equilibrium.” (p. 10.) The biomechanical model guides the assessment and restoration of range of motion, muscle strength and endurance (muscular and cardiovascular) and the prevention and reduction of deformity. The biomechanical model is used for individuals with sensorimotor problems resulting from “motor unit or orthopaedic disorders but whose central nervous system (CNS) is intact” (p. 10). Common intervention methods include “joint measurement, muscle strength testing, kinetic activity, therapeutic exercise, and orthotics” (p. 10) and many of the common interventions from the first two levels (adjunctive methods and enabling activities) derive from the biomechanical model.

Second is the motor control model, which addresses CNS problems. Pedretti and Early (2001) identified four approaches within this model. These were the Rood and Brunnstrom approaches to movement therapy, Knott and Voss’s proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation, and Bobath’s neurodevelopmental treatment. More recent publications of texts on rehabilitation for CNS problems demonstrate that the specific models used for addressing these types of problems have changed as knowledge has developed in this area. Readers are referred to more recent publications for the current approaches in this area.

These two treatment approaches (called frames of reference by other authors) are utilized in combination with the OP model to address problems in the sensorimotor performance components. Occupational therapists typically combine the OP model with other treatment approaches to provide details of interventions for other performance components. For example, they might use a cognitive-behavioural approach to understand interventions for psychosocial problems.

Historical description of model’s development

Despite the model being now somewhat dated, and no longer formally published, we have presented the OP model here because it is, arguably, the model that has influenced most pervasively the thinking of many practising occupational therapists throughout the world. This applies particularly to the area of physical dysfunction, but also more broadly.

The OP model reflected the official stance of the American Occupational Therapy Association and was influenced by their documents produced from the early 1970s. In 1996, Pedretti provided a detailed description of the history of the development of the OP model. She commenced by stating:

In 1973 the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) published The Roles and Functions of Occupational Therapy Personnel. This publication referred to occupational performance as a frame of reference that included three performance skills, later named performance areas, and five performance components, later combined to become the three used in the later versions of the OP model. The purpose was to describe the areas of expertise of occupational therapists and the domains of concern within the profession. (p. 5)

In this history, she discussed various publications throughout the 1970s and early 1980s as documents that contributed to an understanding of occupational performance. She also cited the three editions of the AOTA publication outlining recommendations for uniform reporting of occupational therapy services (which were primarily centred on hospital-based services) as documents that “defined the terminology in the occupational performance frame of reference” (p. 5). In summarizing its development, she wrote:

Thus, the concept of the Occupational Performance model was developed from a series of task forces and committees of the AOTA. It was generated from professional conceptualizations of practice and originally described as a frame of reference for practice and for curriculum design in education. (p. 5)

Evident with the OP model is the influence of both the mechanistic paradigm and the beginning of the renaissance of occupation (both discussed in the introduction to this book – see Table I.1). In line with this renaissance of occupation, a change in the discourse of occupational therapy has occurred since the latter part of the twentieth century, with the term occupation becoming used pervasively. The sixth edition of Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction (McHugh Pendleton & Schultz-Krohn, 2006) reflects this shift towards occupation within the profession by presenting the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) as representing the official position of the AOTA (rather than the OP model like the previous editions). The OTPF has also been developed with the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in mind, and its relationship to the ICF is emphasized in the sixth edition. This emphasis on the ICF demonstrates the shift that has also occurred in the broader healthcare environment, in which the focus has moved away from bodily impairments alone (a biomedical approach), to activity and participation (both biopsychosocial and socioecological approaches). This movement is more aligned with the current paradigm of occupation in occupational therapy.

Occupational therapy practice framework (OTPF)

The OTPF reflects the current movement towards occupation as occupational therapy’s core concern. However, the influence of the OP model on this framework is apparent. The concepts of performance areas, performance components and context are evident within this practice framework, albeit relabelled and incorporated into more detailed and additional categories. The way that the categories of the OTPF relate to the International Classification of Function (ICF) is also made explicit in the OTPF document. The OTPF has been published in two editions − 2002 and 2008. The edition used in this chapter is from 2008 and this includes a summary of the changes made to the first edition in developing the second edition. That summary is provided on pages 665–667 of the second edition (AOTA, 2008).

The OTPF aims to make explicit both the domain and process of occupational therapy. According to McHugh Pendleton and Schultz-Krohn (2006), “the domain describes the scope of practice or answers the question: ‘What does an occupational therapist do?’ The process describes the methods of providing occupational therapy services or answers the question: ‘How does an occupational therapist provide occupational therapy services?’ (p. 10).

Domain

The OTPF domain is divided into the following six categories: areas of occupation, client factors, activity demands, performance skills, performance patterns, and context and environment. The influence of the OP model is particularly evident within the first category, areas of occupation. This category includes activities of daily living (ADL) (also called personal or basic ADL, i.e. PADL and BADL, respectively), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), rest and sleep, education, work, play, leisure and social participation. The OTPF emphasizes that particular occupations can only be categorized in terms of their meaning and purpose for an individual. For example, laundry might be categorized as work for one person and IADL for another.

Client factors are “specific abilities, characteristics, or beliefs that reside within the client and may affect performance in areas of occupation” (AOTA, 2008, p. 630). As clients of occupational therapy services could be individuals, organizations or populations, this category is conceptualized as relevant to all three potential client groups. For each, the relevant values and beliefs, functions and structures are considered. For the person, values, beliefs and spirituality “influence a client’s motivation to engage in occupations and give his or her life meaning” (p. 633).

Using terminology consistent with the ICF, client factors include body functions and body structures. Quoting from a WHO publication, body functions are defined as the physiological functions of body systems (including psychological functions) and body structures refer to the anatomical parts of the body such as organs, limbs and their components. For organizations, values and beliefs might be encapsulated in vision and other value statements and codes of ethics. Functions include the processes that an organization uses for its planning, organizing and operationalizing its core functions and vision. Structures relate to the way the organization is structured including departments and their relationships, leadership and management structures, performance measures, etc. For populations, values and beliefs can include “emotional, purposive, and traditional perspectives”; functions include “economic, political, social and cultural capital” and structures “may include constituents such as those with similar genetics, sexual orientation, and health-related conditions” (AOTA, 2008, p. 634).

Activity demands “refer to the specific features of an activity that influence the type and amount of effort required to perform the activity” (AOTA, 2008, p. 634). A core skill of occupational therapists is the analysis of activities and occupations. They use this analysis to determine the capacities required for an individual to perform these activities within particular contexts. The specific constellation of demands of performing an activity or occupation provides enormous potential for altering activity demands to enable engagement in occupation. A change in one component of the activity or the context in which it is performed changes the total demands of the activity or occupation.

Performance skills have the closest relationship to performance components in the OP model. Performance skills are “the abilities clients demonstrate in the actions they perform” (AOTA, 2008, p. 639). The OTPF uses the following six interrelated categories for performance skills: motor and praxis skills, sensory-perceptual skills, emotional regulation skills, cognitive skills and communication and social skills (which have similarities to the original five categories of performance components). The OTPF distinguishes between body functions and performance skills in that body functions are capacities that “reside within the body” (p. 639) whereas performance skills are those abilities that can be demonstrated. Two of the examples that were given in the OTPF document of observable nature of performance skills are as follows: “praxis skills can be observed through client actions such as imitating, sequencing, and constructing; cognitive skills can be observed as the client demonstrates organization, time management, and safety” (p. 639). In further explicating the difference, the OTPF states “numerous body functions underlie each performance skill” (p. 639).

Performance patterns include the “habits, routines, roles, and rituals” (p. 641) that people use when engaging in activities and occupations. All four can facilitate or make difficult engagement in and performance of occupations. Habits are automatic behaviours used for engagement in occupations; routines are “established sequences of occupations or activities that provide a structure for daily life” (p. 641); roles are “sets of behaviour” (p. 641) that have social and personal expectations, can have implications for self-identity, and can shape choice and meaning of occupations; and rituals are “symbolic actions with spiritual, cultural, or social meaning that contribute to the client’s identity and reinforce the client’s values and beliefs” (p. 642). Performance patterns can develop and change over time and assist people to organize their engagement in occupations within their daily lives and over the course of their lives. The concept of performance was not a feature of the OP model, but has become embedded in occupational therapy thinking. This possibly occurred through the pervasive influence of Kielhofner’s Model of Human Occupation, presented in Chapter 6, which introduced the concept habits and routines.

Occupational therapists have always acknowledged that engagement in and performance of occupations occurs with specific places, at specific times, under specific conditions. In the OTPF, the situatedness of occupational performance is considered using the category of context and environment. It uses the term environment to refer to the physical and social environments. The physical environment refers to the natural and built environments (including the objects within them) in which people might perform occupations and the social environment “is constructed by the presence, relationships, and expectations of persons, groups, and organizations with whom the client has contact” (AOTA, 2008, p. 642).

While the term environment is used to refer to tangible aspects of the situation within which people engage in occupation, the term context is used to acknowledge the less tangible aspects of the circumstances surrounding occupational performance that can strongly influence it. These contexts can be “cultural, personal, temporal, and virtual” (AOTA, 2008, p. 642). The OTPF provides the following definitions of these four types of context, some of which are attributed to the WHO: “Cultural context includes customs, beliefs, activity patterns, behaviour standards, and expectations accepted by the society of which the client is a member. Personal context refers to demographic features of the individual such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, and educational level that are not part of a health condition. Temporal context includes stages of life, time of day or year, duration, rhythm of activity, or history. Virtual context refers to interactions in simulated, real-time or near-time situations absent of physical contact” (pp. 642 & 646). As these definitions demonstrate, the contexts surrounding occupational performance can be internal or external to the client or, in the case of cultural context, both internal and external contexts can combine – in that culture is an external context that shapes individual values and beliefs but the individual also internalizes these (to varying extents), making them part of the internal context of occupational performance.

Process

In addition to the occupational therapy domain, the OTPF also describes the “process that outlines the way in which occupational therapy practitioners operationalize their expertise to provide services to clients” (AOTA, 2008, p. 646). While the general processes that occupational therapists use, that is, assessment/evaluation, intervention and evaluating the outcomes, are also used by other professions, the OTPF document highlights that the distinctiveness of occupational therapy lies in its work “toward the end-goal of supporting health and participation in life through engagement in occupations” (pp. 646–647). Occupational therapists are also unique in that they conceptualize occupations as both methods and outcomes. Within a collaborative relationship with the client, occupational therapists plan for interventions on the basis of jointly identified and prioritized goals.

The first part of the process is assessment/evaluation. Practitioners collect sufficient appropriate information to develop an understanding of what has been, needs to be, and can be done with and for the client. The OTPF identifies this stage as consisting of both the occupational profile and analysis of occupational performance. It states, “The occupational profile includes information about the client and the client’s needs, problems, and concerns about performance in areas of occupation. The analysis of occupational performance focuses on collecting and interpreting information using assessment tools designed to observe, measure, and inquire about factors that support or hinder occupational performance.” (AOTA, 2008, p. 649.) These two components of the assessment/evaluation stage are described in detail in the OTPF document. Occupational therapists use their clinical reasoning to combine, analyze and synthesize information gained about the client’s occupational profile and occupational performance and make decisions about intervention.

Intervention is defined as “the skilled actions taken by occupational therapy practitioners in collaboration with the client to facilitate engagement in occupation related to health and participation” (AOTA, 2008, p. 652). In the OTPF, the intervention process is categorized into three steps, which are not necessarily followed in a linear sequence in practice. These are development of an intervention plan, implementation of the intervention, and its review. Each step in the intervention process is discussed in detail in the OTPF document.

The third part of the occupational therapy process relates to evaluating outcomes. The OTPF described the overall outcome of occupational therapy intervention as “supporting health and participation in life through engagement in occupation” (AOTA, 2008, p. 660). More specific outcomes are generally required to determine the degree of progress towards this more general goal that might have resulted from occupational therapy interventions. More specific outcomes might include “clients’ improved performance of occupations, perceived happiness, self-efficacy, and hopefulness about their life and abilities” (pp. 660–661). Outcomes might include information about clients’ subjective impressions of relevant goals or increments of progress that are measurable. The OTPF document proposed that “outcomes for populations may include health promotion, social justice, and access to services” (p. 661). The document outlined two steps in the outcomes process. The first was “Selecting types of outcomes and measures, including but not limited to occupational performance, adaptation, health and wellness, participation, prevention, self-advocacy, quality of life, and occupational justice” (p. 661). The second step was “Using outcomes to measure progress and adjust goals and interventions” (p. 661).

Summary

In this section of the chapter, we have reviewed the OP model and the OTPF. Taken together, these two theoretical frameworks represent the major threads in occupational therapy thinking in the USA. While the OP model is no longer published, its legacy appears to have remained within both occupational therapy practice in Western countries and within the OTPF, which is currently the official document of the AOTA. The OTPF has embedded within it many of the concepts of the OP model, but these have been expanded and articulated using the current language of occupation.

Because the AOTA is clear that the OTPF is not a model of practice, we have presented a memory aid for the OP model, as that model still seems to influence much current practice. In the following section, we present a memory aid for the OP model to help make explicit how it would be used in practice.

Memory aid

See Box 3.1.

BOX 3.1 Occupational Performance (OP) model memory aid

For each role

How do these roles influence the person’s self-identity and access to social and financial resources?

How do these roles influence the person’s self-identity and access to social and financial resources?In which roles, if any, is the person likely to encounter problems with performance of those roles?

How is the context in which those roles are performed likely to affect, if at all, that performance?

American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process, second ed. Am. J. Occup. Ther., 62. 2008:625-683.

McHugh Pendleton H., Schultz-Krohn W. The occupational therapy practice framework and the practice of occupational therapy for people with physical disabilities. In: McHugh Pendleton H., Schultz-Krohn W., editors. Occupational therapy: Practice skills for physical dysfunction. sixth ed. St Louis, MI,: Mosby; 2006:2-16.

Pedretti L.W. Occupational performance: A model for practice in physical dysfunction. In: Pedretti L.W., editor. Occupational therapy: Practice skills for physical dysfunction. fourth ed. St Louis, MI,: Mosby; 1996:3-12.

Pedretti L.W., Early M.B. Occupational performance and models of practice for physical dysfunction. In: Pedretti L.W., Early M.B., editors. Occupational therapy: practice skills for physical dysfunction,. fifth ed. St Louis, MI,: Mosby; 2001:3-12.

Occupational Performance Model (Australia) (OPMA)

The second model we review in this chapter is the Occupational Performance Model (Australia) (Chapparo & Ranka, 1997). This model does not represent the official position of OT Australia (the Australian Association of Occupational Therapy) in the way that the OP model represents the official position of the AOTA. Nor was it adopted by the majority of occupational therapists practising in Australia (its use was strongest in New South Wales, the Australian state in which it was developed). However, we have included this model in this book as it provides an excellent example of the influence of a biopsychosocial model of health on occupational therapy conceptual models.

Main concepts and definitions of terms

As the name suggests, the Occupational Performance Model (Australia) (OPMA) is a model that focuses on occupational performance as its central concept. It is structured in a similar way to the American OP model through levels of occupational performance. The OPMA addresses occupational performance on three mutually influencing levels − occupational roles, occupational performance areas and occupational performance components – as well as a fourth level that identifies three core elements of occupational performance: body, mind and spirit. It also includes more explicit attention to the environment than the OP model, through the concepts of space and time as factors that influence occupational performance. While the overall structure of the OPMA is similar to the OP model, particularly in its use of occupational performance areas and components, the differences in the OPMA are more consistent with other models developed or updated around a similar time (the 1990s). The trends that are evident in models at the time were towards: (1) a more integrated view of the environment and its influence on occupational performance; (2) an increased focus on and use of the term occupation (rather than activity); and (3) a biopsychosocial understanding of the person as consisting of subjective perceptions and experiences as well as body structures and functions. While the OPMA could have been included in Chapter 4 because of its extensive focus on the environment, we have included it here to emphasize the difference between the largely biomedical approach embedded in the OP model and the biopsychosocial approach of the OPMA.

Figure 3.2 provides a diagram of the OPMA. The influence of the AOTA OP model on the OPMA is evident in the structure of this diagram, in that, performance areas and performance components are presented as two different but interconnected levels in a central position in the diagram. These two concepts are central to the way that occupational performance has been conceptualized in Western countries.

FIG 3.2 Occupational Performance Model (Australia).

From http://occupationalperformance.com; created by and reprinted with kind permission of Christine Chapparro and Judy Ranka.

However, the two models differ with regard to the detail with which they attend to the broader context on occupational performance. The diagram of the American OP model provides extensive detail about performance areas and components, represented visually as the central features of the model that contribute to an understanding of occupational performance, while the environment is placed off to one side and is given little detail. In contrast, and consistent with other occupational therapy models of practice in the 1990s, the OPMA diagram represents the environment as surrounding the person and categorizes it into four components – sensory, social, cultural and physical environments. In addition, it also shows that space and time influence occupational performance.

The OPMA diagram shows component parts of the model that are considered to be interconnected. This interconnectedness is represented in the diagram by multiple arrows. The interconnectedness is also evident in the definitions of various components and constructs, which frequently make reference to other components and constructs in their definitions.

Many models at this time conceptualized the person and environment as intimately connected. Central to the OPMA is a relationship among person, environment and occupational performance. As Chapparo and Ranka (1997) stated, “the primary focus of this model is the lifelong person-environment relationship and its activation through occupation” (p. 3). Evident within this quote is the assumption that occupation forms the conduit between person and occupation. As discussed in the introduction to this book, this is one of the two major ways that occupational therapists conceptualize a relationship among person, environment and occupation. A range of different models presented in this book are based on this assumed relationship between person and environment and the idea that this relationship is enabled through occupation.

The inter relatedness of person and environment is evident in the OPMA in the way the term environment is used. Rather than labelling person and environment separately, it refers to internal and external environments (i.e. what would often be called ‘person’ in other models is conceptualized here as the internal environment). With reference to the diagram, the internal environment is placed as a central column consisting of four levels – occupational performance role, performance areas, performance components, and the core elements of body, mind and spirit. Surrounding these four levels of the internal environment is the external environment. This consists of sensory, social, cultural and physical environments. The internal and external environments intersect in the diagram at the levels of occupational role and core elements. A major aspect of the model is a conceptualization of occupational performance roles as the key point of intersection between the internal and external environments.

The internal environment

The internal environment occupies the central column of the OPMA diagram. The top level of occupational roles is the point at which the internal and external environments connect. The other three levels provide the details about the components of occupational performance.

Occupational roles: where the internal and external environments connect

While the internal environment comprises occupational roles, performance areas, performance components and the core elements of body, mind and spirit, the performance of occupational roles is the central focus of this model. From the perspective of the OPMA, every type of intervention that occupational therapists use should be done for the purpose of facilitating the performance of occupational roles. Any interventions used by occupational therapists that target occupational performance areas and components are only used because they are expected to influence the performance of occupational roles through these other levels. (This is similar to the emphasis placed in the OTPF, described earlier.) Chapparo and Ranka (1997) defined occupational performance roles as “patterns of occupational behaviour composed of configurations of self-maintenance, productivity, leisure and rest occupations. Occupational performance roles are determined by individual person-environment-performance relationships. They are established through need and/or choice and are modified with age, ability, experience, circumstance and time” (p. 6).

This definition emphasizes four important aspects of occupational roles in the model: (1) the degree to which occupational roles are influenced by both the individual performing the roles and social expectations of role performance; (2) the importance of the broader context in determining the need for and/choice of engagement in occupational roles; (3) the changing nature of occupational roles over time and with changing abilities, circumstances and experiences and; (4) the interconnectedness of occupational roles and occupational performance areas (and, flowing on from this, performance components).

First, the occupational roles of any particular person are configured uniquely depending on both the person’s interpretation of what is required and the expectations of others (both society and significant individuals). As evident in the diagram, it is at the level of occupational roles that the internal and external environments intersect. Consequently, in conceptualizing occupational roles, the OPMA emphasizes the interaction between the person (internal environment) and the external environment in shaping those roles. As Chapparo and Ranka (1997) stated, “within the boundaries of each role acquired throughout life, expectations of performance of role related tasks are formed by both socio-cultural factors in the external environment as well as the person who becomes the role performer” (p. 4).

Definitions of roles often emphasize the social expectations associated with roles. For instance, Chapparo and Ranka used Christiansen and Baum’s 1991 definition of roles, stating that a role comprises “a set of behaviours that have some socially agreed upon functions and for which there is an accepted code of norms” (p. 4). Chapparo and Ranka then commented that occupational performance roles are “those roles that constitute the bulk of daily function and routines” (p. 4). A person’s role perception is dependent upon both the social expectation associated with that role and the person’s own perception of the value of the role in his or her life and what he or she should or needs to do to fulfil it. The emphasis the OPMA places on the mutual influence between social and individual expectations and interpretations differentiates this model from others that conceptualize occupation as the medium through which person and occupation are connected. Whereas some other models conceptualize occupation as the vehicle through which individuals obtain mastery over the environment, the relationship between person and environment is not understood as the person acting on the environment through occupation. Instead, social roles encapsulate a two-way influence.

Second, the definition refers to occupational roles being established through need and/or choice. This assertion encapsulates the notion that occupational roles can fulfil a number of purposes in people’s lives. Their position at the intersection between the internal and external environments emphasizes that these needs and choices are influenced by both environments. For example, a person might perceive the need to engage in a particular occupational role in a particular way in order to meet a social demand (social expectations). However, fulfilling this role might also affect how that person thinks about him- or herself (self-identity) and influence the capacities, skills and interests that the person develops. If the person’s role performance is evaluated positively by both the external and internal environments, the person is likely to enjoy and pursue that role and it might become increasingly self-defining. In contrast, if the person feels that he or she has no choice but to perform that role, he or she might see it as a duty or essential for survival (or some other social purpose) rather than something to look forward to or that is self-defining. In either case, the person might or might not choose or determine the need to enhance their skills and employ them in fulfilling that role. Chapparo and Ranka (1997) also made the point that “individual choice is alien to a number of social groups whose sociocultural identity is collective” (p. 5).

Third, the OPMA proposes that a person’s occupational roles change with age, ability, experience and circumstance. While a person is likely to fulfil multiple roles simultaneously, these roles and their combinations will change as the internal and external environments change. Internal environments change as people age, their capacities, skills and interests wax and wane, and their experiences and expectations of and hopes for life change. External environments change as people come and go, as the physical environments in which people perform occupational roles alter and vary, and as societies, organizations and institutions change. As the internal and external environments change, the demands placed on a person and his or her preferences, abilities and perceptions of choice combine to influence people’s roles and their performance of those roles.

Fourth, in the OPMA, attention is given to performance areas and performance components in order to understand and facilitate occupational performance of roles. In this model, the central purpose of occupational therapy, a profession that often claims to promote health and well-being through occupation, is the facilitation of performance of occupational roles. Chapparo and Ranka (1997) explained the association between health and performance of occupational roles by stating, “Health is not the absence of disease, rather, it is competence and satisfaction in the performance of occupational roles, routines and tasks” (p. 2).

Chapparo and Ranka proposed that occupational performance roles have three dimensions − knowing, doing and being – which can contribute to occupational role performance to different degrees, depending on the abilities of the person and the demands of the role. They defined the knowing element as “having an intuitive or concrete understanding of desired or expected occupational performance roles” (p. 5). In a sense, it is about knowing what is required of you. The doing element refers to the process of carrying out occupational performance roles. Thus, it is not enough to know what is required but one also needs to be able to do what is required. The being element is described as a “fulfilment or satisfaction component of occupational performance roles” (p. 5). Because the internal and external environments are bound closely, the process of knowing about and performing occupational roles also has an effect on how the person feels and thinks about him- or herself.

Occupational performance areas and components and the core elements

A primary skill of occupational therapists is being able to understand and analyze the performance of occupational roles. In the OPMA, occupational role is at the top of four levels at which occupational performance can be analyzed. The three levels below it in the diagram are all part of the internal environment. These additional levels are occupational performance areas, occupational performance components and core elements of occupational performance, which are required for the performance of social roles.

The first level is occupational performance areas. The definition of occupational roles provided in the OPMA makes reference to “patterns of occupational behaviour composed of configurations of self-maintenance, productivity, leisure and rest occupations” (p. 6). As with the OP model, the OPMA uses the categories of performance areas to group occupations that contribute to occupational roles. However, in identifying performance areas, the OPMA emphasizes that the process of classifying particular occupations is idiosyncratic and should be done by the performer. The performance areas into which any individual might classify particular occupations can also change over time, age, circumstance and ability.

The OPMA adds rest occupations to self-maintenance, productivity and leisure, the last three areas being traditionally used in occupational therapy discourse and aligning with the main occupational performance areas in the OP model. Rest occupations were defined as “the purposeful pursuit of non-activity” (p. 6) and include sleep and the various activities undertaken for the purpose of relaxation. Chapparo and Ranka justified the inclusion of this performance area as a separate category to self-maintenance occupations by stating that “there are socio-cultural, daily and life span reasons for the degree to which people are, or wish to be, passive and contemplative rather than active and productive” (pp. 6–7). This rationale acknowledges the way the external environment can influence a person’s occupational behaviour. In contrast, categorizing rest as self-maintenance activities would be emphasizing the internal moderation aspects of the behaviour, rather than the need or choice to respond to external demands and influences.

The performance areas are a way of categorizing occupations into groups. However, OPMA further categorizes occupations into types of activity. The model does not use the term ‘activity’ because the authors argued that the “meanings attributed to the underlying construct [activity] have become so broad and flexible that it has lost its power to 1) describe elements of occupations and performance at varying levels, and 2) direct and influence the focus of occupational therapy intervention” (p. 7). Consequently, the model divides occupations into the subcategories of subtasks, tasks and routines. Subtasks are “steps or single units of the total task and are stated in terms of observable behaviour” and tasks are “sequences of subtasks that are ordered from the first performed to the last performed to accomplish a specific purpose” (p. 7). Chapparo and Ranka (1997) gave the example of the task of drinking, which can be divided into subtasks such as locating, reaching for, grasping and lifting the drinking vessel. These subtasks are performed in an orderly sequence in order to accomplish the task of drinking. Routines constitute the third subcategory and are “sequences of tasks that begin in response to an internal or an external cue and end with the achievement of the identified critical function” (p. 8). Routines are usually established to support the performance of occupations within the performance areas (i.e. self-maintenance, productivity, leisure and rest).

In the OPMA, all three subcategories of occupations are considered able to be classified according to structure and time. However, routines are discussed in more detail than tasks and subtasks in relation to both constructs. Chapparo and Ranka (1997) explained that routines have either fixed or flexible structures and regular or intermittent temporal patterns. Some routines have a fixed structure, in which they might show little deviation from established sequences of tasks and subtasks. Other routines can be undertaken using a greater variation in its components. Routines can also be fixed or intermittent in their temporal patterns. Regular routines can often become habitual “whereby the routine of well-practiced sequences of tasks can be performed without thinking” (p. 8). Intermittent routines do not have the same regularity but can be just as critical to the performance of occupations. The temporal aspects of routines, tasks and subtasks also vary with age, circumstance and ability.

The second level that contributes to the performance of occupational roles is performance components. Chapparo and Ranka (1997) stated, “accomplishment of routines and tasks in the occupational performance areas is predicated on the ability to sustain efficient physical, psychological and social function” (pp. 9–10). The OPMA presents a complicated view of performance components in that it conceptualizes this level as “forming both the component attributes of the performer as well as the components of the occupational tasks” (p. 10). As the authors explained, “there are physical, sensory-motor, cognitive and psychosocial dimensions to any task performed. These dimensions mirror and prompt a person’s various physical, sensory-motor, cognitive and psychosocial operations which are used to engage in task performance” (p. 10). Therefore, for each of the five performance components that it addresses – biomechanical, sensory-motor, cognitive, intrapersonal, interpersonal − it presents that component from the perspective of the performer and pertaining to the aspects of the task. Table 3.2 provides the details of each of these perspectives.

Table 3.2 Component attributes of the performer and components of occupational tasks

| Performance component | Perspective of the performer during task performance | Aspects of the task |

|---|---|---|

| Biomechanical | Operation of and interaction between physical structures of the body, e.g. range of motion | Biomechanical attributes of the task, e.g. size, weight |

| Sensory-motor | Operation of and interaction between sensory input and motor responses of the body, e.g. regulation of muscle activity | Sensory aspects of the task, e.g. colour, texture |

| Cognitive | Operation of and interaction between mental processes, e.g. thinking, perceiving, judging | Cognitive dimensions of the task – usually determined by its symbolic and operational complexity |

| Intrapersonal | Operation of and interaction between internal psychological processes, e.g. emotions, mood, affect, rationality | Intrapersonal attributes that can be stimulated by the tasks and are required for effective task performance, e.g. valuing, satisfaction, motivation |

| Interpersonal | The continuing and changing interaction between a person and others… that contributes to the development of the individual as a participant in society, e.g. relationships in partnerships, families, communities requiring sharing, cooperation, empathy | The nature and degree of interpersonal interaction required for effective task performance |

The final internal level comprises the interaction of the core elements of body, mind and spirit. Chapparo and Ranka (1997) quoted Adolf Meyer, “our body is not merely so many pounds of flesh and bone figuring as a machine, with an abstract mind or soul added to it” (pp. 11–12). Meyer’s comments were made in the context of the time when the biomedical model prevailed and a focus on the body was widespread. By making explicit the importance of body, mind and spirit (not just the body), the OPMA affirmed its position within a biopsychosocial perspective.

The body element comprises “all of the tangible physical elements of human structure”; the mind element is defined as “the core of our conscious and unconscious intellect which forms the basis of our ability to understand and reason”, and the spiritual element “is defined loosely as that aspect of humans which seeks a sense of harmony within self and between self, nature, others and in some cases an ultimate other; seeks an existing mystery to life; inner conviction; hope and meaning” (Chapparo & Ranka 1997, pp. 12–13). Chapparo and Ranka summed up the relationship between these different core elements of occupational performance by stating:

Together the body, mind, and spirit form the human body, the human brain, the human mind, the human consciousness of self and the human awareness of the universe. Relative to occupational performance, the body-mind-spirit core element of this model translates into the ‘doing-knowing-being’ dimensions of performance. These doing-knowing-being dimensions are fundamental to all occupational performance roles, routines, tasks and subtasks and components of occupational performance. (p. 13)

The external environment

Surrounding the internal environment and linked to it, especially through occupational roles, is the external environment. In OPMA, the external environment is conceptualized as having four dimensions − sensory, physical, social and cultural − that are all interconnected. All of these external factors influence occupational roles and their performance.

The physical environment refers to “the natural and constructed surroundings of a person” (p. 15). This forms the physical boundaries within which occupational performance takes place. The demands of the physical environment shape occupational performance by determining the skills and abilities required to perform particular routines, tasks and subtasks in a particular location and/or position. Chapparo and Ranka (1997) also proposed that the physical environment is shaped by the sociocultural environment and provided the example of the configuration of a large Western city being quite different to a tropical village on a Pacific island.

Chapparo and Ranka (1997) proposed that the sensory environment “provides the natural cues that direct occupational performance” (p. 15) and connects most closely to the sensory and cognitive performance components. The cultural environment “is composed of systems of values, beliefs, ideals and customs which are learned and communicated to contribute to the behavioural boundaries of a person or group of people” (p. 15). Cultural expectations of how people should behave and what they should do influence which occupational roles people need or choose to fulfil, how they formulate those roles, and how they see and feel about themselves (self-identity). In the OPMA, social environment is defined as “an organized structure created by the patterns of relationships between people who function in a group which in turn contributes to establishing the boundaries of behaviour” (p. 15).

The way that the external environment is discussed demonstrates the degree to which the OPMA emphasizes the influence of the environment on human behaviour. As the authors stated, “many occupational performance roles, routines, tasks and subtasks are performed specifically in response to external demands leading to constant adaptation of occupational behaviour” (Chapparo & Ranka, 1997, p. 15). However they also presented the view that the external environment can change or be maintained as a result of occupational performance. Therefore, it is important to see the internal and external environments as mutually influencing.

Constructs of space and time

In the OPMA, the notions of space and time are understood to pervade occupational performance. Both concepts are discussed in terms of their physical manifestation and how they are experienced. Chapparo and Ranka (1997) referred to these notions as physical and felt space and time. The notion of physical space is derived from the concepts of physics and includes “our understanding about body structures, body systems, objects with which people interact and the wider physical world within which people exist and function” (p. 16). Felt space refers to the subjective experience of space. This might include “the meaning [people] attribute to it, the way they use it and their interactions within it” (p. 16). The model emphasizes that the way physical space is experienced (felt) during occupational performance pervades all of the internal levels of occupational performance. For example, the size and shape of physical objects will activate receptors and responses at the performance component level, which will be interpreted at the level of the body−mind−spirit core elements and all of this subjective experience will contribute to the performance of occupations and occupational roles.

As with space, time is discussed in terms of physical and felt time. Physical time relates to the laws of physics and can be seen in processes like the measurement of time and the regular movement of the sun and moon. Chapparo and Ranka (1997) defined and explained felt time as follows: “Felt time is a person’s understanding of time based on the meaning that is attributed to it… felt time involves highly personal abstractions of time that have representation at all levels of the model. It is an experiential abstraction that is being constantly changed and modified by experience.” (p. 18.) Both physical and felt time influence occupational performance. For example, physical time is important when recording muscle contraction and response times. It often shapes routines and deadlines by which tasks and subtasks need to be completed. Felt time might influence performance through phenomena such as the sense a person has of how much time is available for the occupation and whether he or she feels it can be accomplished in that time or whether it is the ‘right’ time for something.

Occupational performance

The overall purpose of the OPMA is to provide a framework to address “both the nature of human occupations and occupational therapy practice” (Chapparo & Ranka, 1997, p. 1). Occupational performance is the major construct used to address these aims. Chapparo and Ranka defined occupational performance as “the ability to perceive, desire, recall, plan and carry out roles, routines, tasks and subtasks for the purpose of self-maintenance, productivity, leisure and rest in response to demands of the internal and/or external environment” (p. 4).

This definition gives important cues for understanding this model and some of its unique aspects. The first part of the definition refers to perceiving and desiring and points to the inclusion of and focus on an individual’s subjective experience within the model. The model acknowledges that occupational performance depends upon the individual’s perceptions and experiences of the world and his or her place within it. According to the definition, occupational performance depends on the person perceiving the need to perform occupation and forming a desire to do this. The concept of occupational role helps to explain how this need and desire are created. People fulfil occupational roles in their lives through their occupational performance. Fulfilling roles is not the only reason why people perceive the need and desire for occupational performance, for example, they might just enjoy it. But roles are important influences on this process of generating need and desire, as they are often vehicles for “social involvement and productive participation” (Chapparo & Ranka, 1997, p. 4). While the agency of people in shaping their occupational roles is acknowledged, the influence of the external environment in pressing upon and influencing occupational behaviour is strongly emphasized throughout the OPMA.

Chapparo and Ranka (1997) explained that occupational roles are determined by the unique interaction between the person, environment and performance, are established through need and/or choice, and change with age, ability, experience, circumstance and time. Individuals have unique constellations of roles that create specific demands for occupational performance, depending upon their life circumstances, goals and desires. These will also change for an individual over the course of his or her lifespan and as circumstances change. Because occupational roles lie at the interface between the internal and external environment, they influence and are influenced by both. For example, the external environment will influence the degree of choice that an individual has over their occupational performance roles and an individual will take on and carry out occupational roles according to his or her interests, capabilities, needs and aspirations.

“Recall, plan and carry out” are the next elements of the definition of occupational performance. They focus our attention on the ability to perform the occupations that are desired or perceived as necessary. The model asserts that performance of occupations requires “the ability to sustain efficient physical, psychological and social function” (p. 10), pointing to the importance of performance components. Occupational therapists develop skills in breaking down occupations and tasks into their components and analyzing the capacities required to accomplish them. This part of the definition points to the cognitive requirements of recalling and planning as well as the broader range of performance components that might be required to carry out the specific occupations. Because performance components relate to both the perspective of the performer and the demands of the task, in this model, occupational analysis requires consideration of how well the personal capacities and the task demands match.

In defining occupational performance, the authors combined their definitions of both performance and occupation. The performance aspect of the definition makes explicit the processes involved in the performing of occupations in terms of the ability to recall, plan and carry out those things that people want and need to do. However, the final part of the definition of occupational performance focuses on occupation, pointing to what people do. Occupation was defined as, “the purposeful and meaningful engagement in roles, routines, tasks and subtasks for the purpose of self-maintenance, productivity, leisure and rest” (p. 4). This definition is concerned with what people do and the purposes these occupations serve in their lives.

This definition presents occupation as a process rather than an entity. That is, it suggests that occupation is (the process of) “purposeful and meaningful engagement” rather than the things in which people engage (which are roles, routines, tasks and subtasks). Thus, when people engage in roles and tasks for the purpose of meeting needs relating to performance areas, they are engaged in the process of occupation.

The final part of the definition reads, “in response to the internal and/or external environment” (p. 4). This part of the definition emphasizes that the roles and activities that people perform are influenced by both their own skills, abilities, interests and desires and the demands of the external environment. The assumption that both environments (internal and external) are mutually influencing is central to this model. As Chapparo and Ranka stated, “Competence and satisfaction with role performance is therefore based on internal as well as external perceptions of performance” (p. 4).

Historical description of model’s development

As with many of the practice models reviewed later in this book, the impetus for the development of the OPMA came from the need for a theoretical framework to guide the curriculum at a particular institution that trained occupational therapists. In this case it was the University of Sydney, Australia. The authors stated that development of the model was commenced in 1986 “when it became clear that existing notions of occupational performance used to structure curriculum content in the Bachelor of Applied Science in Occupational Therapy at Cumberland College of Health Sciences (now The University of Sydney) required expansion to more adequately reflect both the nature of human occupations and occupational therapy practice” (Chapparo & Ranka, 1997, p. 1).

Chapparo and Ranka (1997) explained that this school of occupational therapy was required to undergo 5-yearly curriculum reviews and that, from the mid-1970s to the mid 1990s, the curriculum had changed considerably. They explained that the changes in this period led to “the development of a theoretical framework for the curriculum which [had] two integrated conceptual thrusts” (p. 24). These were: (1) a movement towards “problem-based, adult learning modes of education”; and (2) the use of the “conceptual notions of occupational performance and functions to organize content within the curriculum” (p. 24).

As Chapparo and Ranka stated, “the process of model building was initially stimulated by curriculum restructuring and subsequently continued by the authors to develop a model of occupational performance that was relevant to occupational therapy practice in Australia” (p. 24). They also stated that, in 1997, the OPMA model was at the stage of development where “concepts have been developed, classified and related, but not yet fully evaluated or tested” (p. 2).

The model was developed in five stages. These were:

While a monograph was published in 1997, which included many of the papers and presentations given regarding the model, the major way that the model is made available currently is through its website. This can be found at http://www.occupationalperformance.com. A number of assessments have also been devised, based on OPMA. These include the Perceive, Recall, Plan and Perform System of Task Analysis (PRPP) and the Comparative Analyses of Performance (CAPs).

Summary

OPMA provides an excellent example of the trends that occurred in occupational therapy models of practice in the mid to late 1990s. When contrasted with the OP model, it highlights the difference between a biomedical approach to health, which emphasized the body and normative views of its function and dysfunction, and a biopsychosocial view, which takes a more holistic approach to the person and considers biological, psychological and social aspects of human health and experience. It also forms a bridge to the ecological models presented in Chapter 4, as it starts to ‘blur’ the boundary between person and environment, through the concepts of internal and external environment.

Memory aid

See Box 3.2.

Chapparo C., Ranka J. OPM: Occupational Performance Model (Australia), Monograph 1. Castle Hill, NSW: Occupational Performance Network, 1997.

Chapparo C., Ranka J. Research development. Chapparo C., Ranka J., editors. The PRPP research training manual: continuing professional education. 1996. Edition 2.0, Chapter 9. Available at http://occupationalperformance.com/Index.php?/au/home/assessments/prpp/the_perceive_recall_plan_perform_prpp_system_of_task_analysis

OPMA website OPMA website. Available at http://www.occupationalperformance.com

Occupational Adaptation

The third model presented in this chapter is Occupational Adaptation (OA) (first published by Schkade & Schultz, 1992). This model has been included in this chapter because of its emphasis on foundational concepts in occupational therapy – occupation, adaptation and mastery – and also because it is based on normative assumptions about these concepts. Just as biomedicine is based on a normative view of the body, OA understands adaptation as a normative process. However, the OA model differs from the other models presented in this chapter, because, as its name suggests, its focus is on occupational adaptation rather than occupational performance. It distinguishes between the two concepts by conceptualizing occupational performance as a behavioural outcome and occupational adaptation as an internal process of generalization.

In the various presentations of the model, an emphasis is placed on the ‘normative’ nature of this OA process, meaning that occupational adaptation is a normal human process that occurs across the lifespan, rather than something that only occurs when illness, stress or disability requires adaptation. Therefore, in a number of publications, readers are encouraged to apply the model to their own lives. For example, Schkade and McClung (2001) stated, “we recommend that a therapist wishing to use this perspective in intervention should first ‘try it on’ with regard to his or her own life role adaptation challenges” (pp. 2–3) in order to enhance the person’s understanding of the model.

Main concepts and definitions of terms

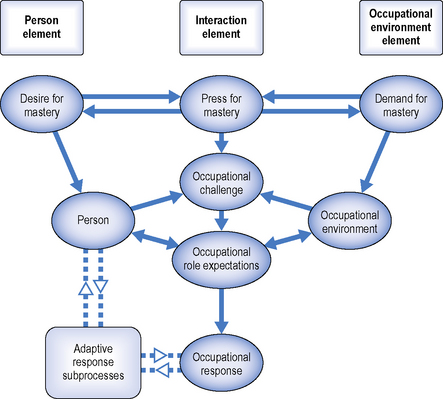

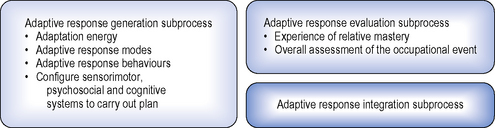

The Occupational Adaptation (OA) model aims to provide a framework for conceptualizing the process by which humans respond adaptively to their environments. The name of the model comes from combining the concepts of occupation and adaptation, which were both foundational concepts for occupational therapy. Schultz and Schkade (1997) defined adaptation as a change in one’s response to the environment when encountering an occupational challenge. As they stated, “This change is implemented when the individual’s customary response approaches are found inadequate for producing some degree of mastery over the challenge” (p. 474). Their definition of adaptation encompasses two important aspects: the need for a changed response and the idea of mastery.