Documentation of Nursing Care

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Identify three purposes of documentation.

2 Correlate the nursing process with the process of charting.

3 Discuss maintaining confidentiality of medical records.

4 Compare and contrast the five main methods of written documentation.

5 List the legal guidelines for recording on medical records.

6 Relate the approved way to correct entries in medical records that were made in error.

1 Correctly make entries on a daily care flow sheet.

2 Use a systematic way of charting to ensure that all pertinent information has been included.

3 Document the characterization of signs or symptoms in a sample charting situation.

4 Apply the general charting guidelines in the clinical setting.

case management system charting (p. 87)

charting (p. 85)

charting by exception (p. 87)

computer-assisted charting (p. 87)

computerized provider order entry (CPOE) (p. 93)

electronic health record (EHR) (p. 92)

focus charting (p. 87)

medical record (chart) (p. 85)

PIE charting (p. 89)

problem-oriented medical record (POMR) charting (p. 87)

protocols ( , p. 91)

, p. 91)

source-oriented (narrative) charting (p. 87)

PURPOSES OF DOCUMENTATION

Documentation provides a written record of the history, treatment, care, and response of the patient while under the care of a health care provider. It acts as a guide for reimbursement of costs of care, may serve as evidence of care in a court of law, shows the use of the nursing process, and provides data for quality assurance studies. Each person who provides care for the patient adds written documentation to the medical record (chart). The medical record contains all orders, tests, treatments, and care that occurred during the time the person was under the care of the health care provider. The chart is a communication tool for the professionals involved in caring for the patient. By documenting, each care provider tells the other health team members what has been done, how the patient has responded, and the current plan for care. Many different forms are used for documentation, and the most common forms are shown in the chapters specific to their content; for example, an intravenous (IV) flow sheet is shown in Chapter 36 (Administering Intravenous Solutions and Medications). A sample list of common chart forms is provided in Table 7-1.

Table 7-1

Forms Used for Hospital Documentation

| FORM | TYPE OF INFORMATION |

| GENERAL FORMS | |

| Face sheet | Patient data, including the patient’s name, address, phone number, next of kin, hospital identification number, religious preference, place of employment, insurance company, occupation, name of admitting physician, and admitting diagnosis |

| Physician’s orders | The physician’s directives for patient care |

| Graphic sheet | Record of serial measurements and observations, such as temperature, pulse, respiration, blood pressure, weight |

| Nursing care plan | Plan of care for the patient, including nursing diagnoses, goals/expected outcomes, and nursing interventions |

| Nurse’s notes | Written report of the nursing process (i.e., assessment, nursing diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation); record of interventions implemented and the patient’s response to them |

| Care flow sheet | Form on which checkmarks or short entries are made to indicate dietary intake, type of bath, wound dressing changes, oxygen in use, physician visits, equipment in use, level of activity, and so forth |

| Medication administration record (MAR) | Documentation of all medications ordered, doses given, and doses not taken by the patient |

| History and physical examination forms | Physician’s record of the patient’s medical history and findings of the current physical examination |

| Nurse’s admission history and assessment | Nurse’s current history, including usual habits, medications usually taken, and physical assessment findings at admission |

| Progress sheet | Physician’s notes regarding the patient’s progress |

| Laboratory reports | Results of laboratory tests |

| Radiology reports | Results of x-ray examinations |

| Admission forms | Information on patient identification, conditions for admission, and consent for general medical and nursing care |

| Intake and output (I&O) record | Serial record of 24-hour intake and output |

| SPECIAL FORMS | |

| Ancillary staff sheets | Records of treatments by physical therapists, occupational therapists, respiratory therapists, and so forth |

| Discharge planning sheet | Records by social services, home health agencies, case managers, and clinical nurse specialists regarding the discharge plans and needs of the patient |

| Consultation sheet | Record of another physician called in to consult by the attending physician |

| Surgical or treatment consent form | Patient authorization for surgery or treatment |

| MISCELLANEOUS FORMS | |

| Diabetic flow sheet | Record of blood sugar determinations and amounts of insulin administered |

| Preoperative checklist | List used to verify that the patient is ready to go to surgery |

| Frequent observations sheet | Used when very frequent measurements of vital signs or neurologic assessments are needed (e.g., after surgery or after head trauma) |

| Intravenous (IV) flow sheet | Record of IV fluids and additives infused, type of IV catheter in use, date tubing was changed, date dressing was applied |

| Transfer form | Information pertinent for the transfer of the patient to another unit or facility |

| Discharge form | Information about instructions given regarding wound care, medications, rest, activity restrictions, needed exercises, diet, and signs and symptoms to report to the physician; also includes when to next see the physician |

| Skin risk assessment | Data from thorough skin assessment upon admission; evaluation of risk factors for skin breakdown; diagrams showing areas of redness, breaks in the skin, or pressure ulcers |

| Fall risk assessment | Information regarding the potential fall risk of the patient; particularly used for frail, elderly, or neuromuscularly impaired patients |

| Pain assessment | Record of pain level, when assessed, measures to reduce it, effectiveness of treatment |

Insurance companies and Medicare rely on documentation in order to determine actual length of stay, procedures performed, and diagnoses established, and to calculate charges due for reimbursement. Each piece of equipment in service must be documented. Charts must display data that support the medical and nursing diagnoses listed. Evaluation data indicating that the treatment was successful or unsuccessful must be present to justify the duration of the hospital stay. Documentation of this type is also necessary for accreditation of the health care agency. Charts are also used for research data collection. For example, statistics may be compiled for the number of cases of pneumonia treated, the average age of the patients, and to see which treatments were the most effective.

The medical record is a legal record and can be used as evidence of events that occurred or treatment that was given. When documentation is thorough, the record provides a way to show that accepted standards of care have been met.

Documentation, also called charting, is used to track the application of the nursing process. The nurse writes down observations made about the patient’s condition, notes the care and treatment that was delivered, and adds the patient’s response. Documentation shows progress toward the expected outcomes listed on the nursing care plan.

Documentation is useful for supervisory purposes to determine how the staff are performing. Charting is audited as part of the health care agency’s quality improvement program. Evidence that care adheres to accepted standards should be present in the nurse’s notes. The results of chart audits tell nurse managers where improvement may be needed.

DOCUMENTATION AND THE NURSING PROCESS

The written nursing care plan or interdisciplinary care plan provides the framework for the nurse’s documentation. Charting is organized by nursing diagnosis or problem. An initial assessment is charted for each shift. Standard areas of assessment are usually noted on flow sheets, and a written note is added if an abnormality exists. Nursing diagnoses or problems are entered on the plan of care, which is created soon after the admission assessment is complete. The plan is reviewed and updated every 24 hours. Implementation of each intervention is documented either on a flow sheet or within the nursing notes. The specifics of what was done and how, plus the patient response, are entered in the chart. Evaluation statements are placed in the nurse’s notes and indicate progress toward the stated expected outcomes and goals. Evaluation data must be documented showing that expected outcomes have been achieved before a nursing diagnosis is marked “resolved” or deleted from the nursing care plan. When expected outcomes are not being met, the plan of care is altered.

THE MEDICAL RECORD

The medical record, or chart, contains data on a patient’s stay in the health facility or while under the care of a health care provider. Each type of facility has a particular set of forms used to record information about the patient.

As a legal record, its contents must be kept confidential and can only be given out with the patient’s written consent because it contains personal information regarding the patient. Only those health professionals caring directly for the patient, or those involved in research or teaching, should have access to the chart. Protecting the privacy of the patient is of prime importance. Patient information is not discussed with others who are not directly involved in the patient’s care.

The chart is the property of the health facility or agency, not of the patient or physician. Patients do have a right to information contained in the chart under certain circumstances (see Chapter 3). Keeping the patient and the family informed in a clear and timely manner usually satisfies their need for such information. After the patient has been discharged, the chart is sent to the medical records or health information department for safekeeping. It can be retrieved if the patient is admitted to service again within a 10-year span.

METHODS OF DOCUMENTATION (CHARTING)

Different methods of charting are used in various health care agencies. The six main methods of charting are (1) source-oriented (narrative) charting, which focuses on the patient’s disease; (2) problem-oriented medical record (POMR) charting, which focuses on the problems experienced by the patient as a result of being ill or on the defined nursing diagnoses reflecting those problems; (3) focus charting, which centers on the patient from a positive perspective; (4) charting by exception, which focuses on deviations from predefined norms, using preset protocols and standards of care; (5) computer-assisted charting, where data are input to the computer; and (6) case management system charting, which tracks variances from the clinical pathway.

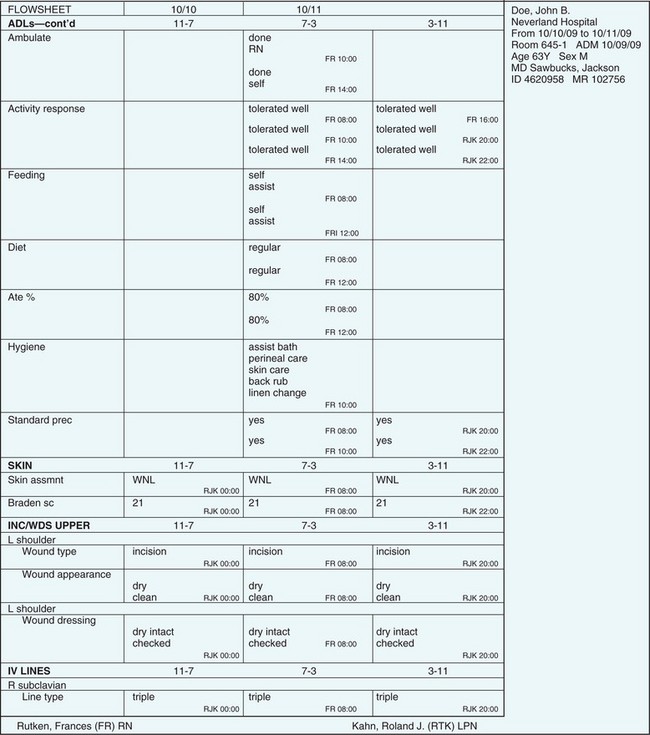

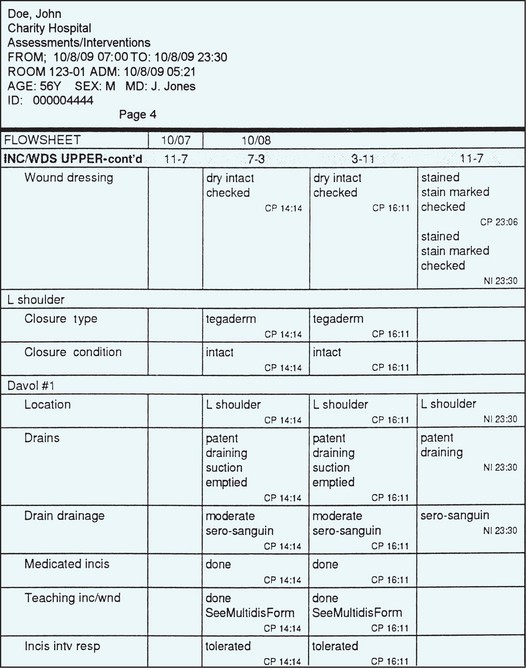

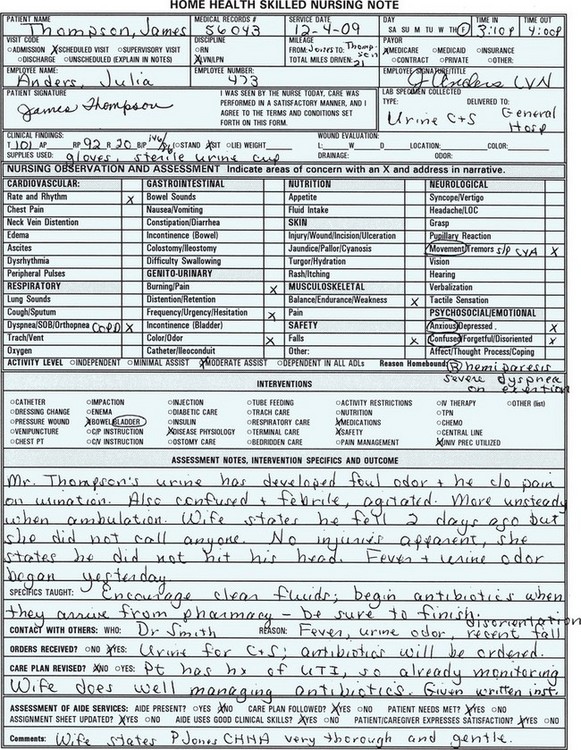

Whatever method of documentation is used, you are required to chart the patient’s progress periodically during the shift or at the time of a home health visit. The chart entries are either in your notes or on the various flow sheets (Figure 7-1). Flow sheets track routine assessments, treatments, and frequently given care. The specific time frame required for charting is found in the agency’s policy and procedure manual. Some agencies require one note per patient contact, others require charting every 1 to 3 hours during the shift.

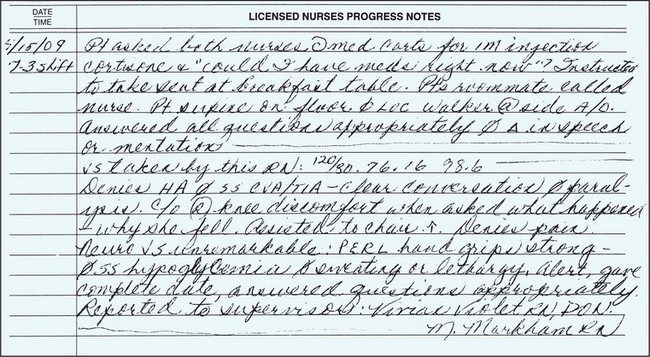

SOURCE-ORIENTED OR NARRATIVE CHARTING

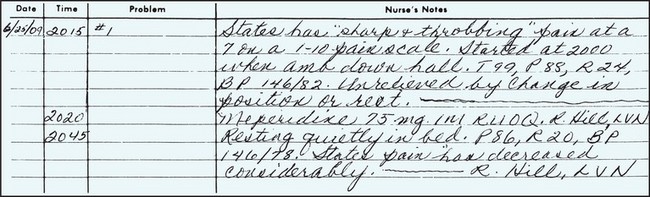

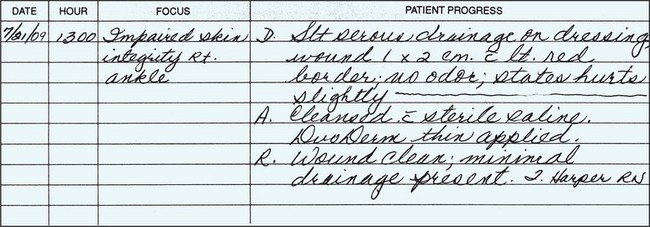

These records are organized according to the source of information. There are separate forms for nurses, physicians, dietitians, and other health care professionals to document their assessment findings and plan the patient’s care. Narrative notes are phrases and sentences written without any standardized structure, content, or form. Narrative charting used in source-oriented records requires documentation of patient care in chronologic order. Assessments usually follow a body systems format. The content is similar to a set of dated and timed journal entries (Figure 7-2).

Advantages of the source-oriented (narrative) method are as follows:

• It gives information on the patient’s condition and care in chronologic order.

• It indicates the patient’s baseline condition for each shift.

Disadvantages of the source-oriented, or narrative, method are as follows:

• It encourages documentation of both normal and abnormal findings, making it difficult to separate pertinent from irrelevant information.

• It requires extensive charting time by the staff.

• It discourages physicians and other health team members from reading all parts of the chart because of the lengthy descriptive entries in it.

PROBLEM-ORIENTED MEDICAL RECORD (POMR) CHARTING

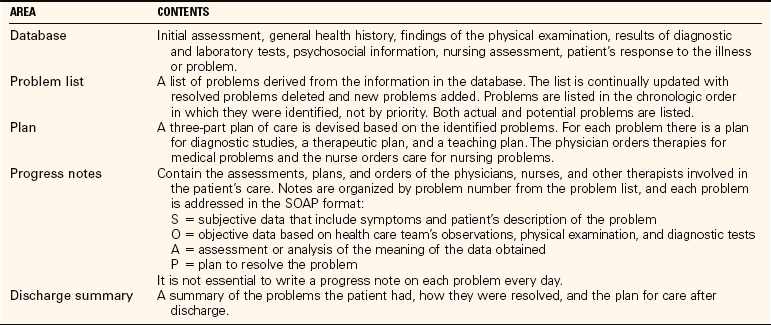

A system developed by Dr. Lawrence Weed has been used since the late 1960s. It focuses on patient status rather than on medical or nursing care. POMR charting emphasizes the problem-solving approach to patient care and provides a method for communicating what, when, and how things are to be done in order to meet the needs of the patient. The POMR contains five basic parts: the database, the problem list, the plan, the progress notes, and the discharge summary (Table 7-2). The precise form these records take varies greatly between agencies, but the essentials of charting are the same.

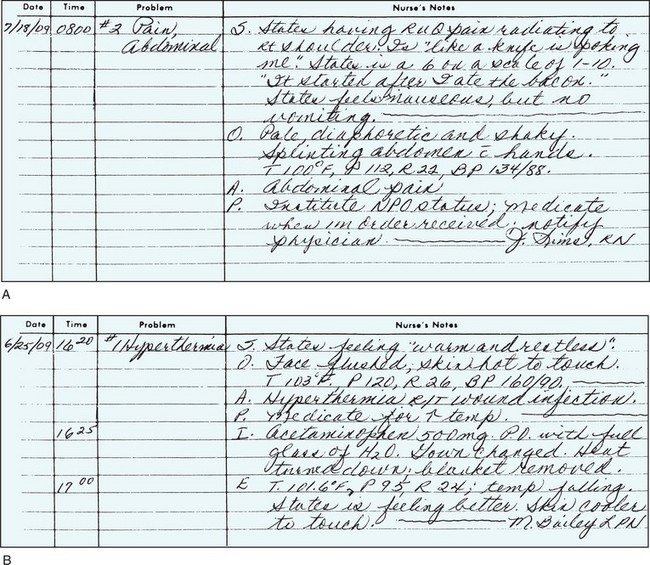

As this documentation method evolved, the original SOAP format for progress notes (S’ subjective information, O’objective data, A’assessment data, and P’plan) was modified to SOAPIE and SOAPIER. The additional letters stand for I’ implementation, E’evaluation, and R’revision. It is not necessary to use each component of the SOAPIER format each time you make an entry. If there are no subjective data, the “S” can be omitted or labeled “none.” If there is no revision, the “R” can be left out (Figure 7-3).

FIGURE 7-3 A, Example of problem-oriented medical record (POMR) charting. B, Example of SOAPIE (subjective, objective, assessment, plan, implementation, evaluation) charting.

Advantages of the POMR method of documentation are as follows:

• It provides documentation of comprehensive care by focusing on patients and their problems.

• It promotes the problem-solving approach to care.

• It improves continuity of care and communication by keeping relevant data related to a problem all in one place so that it is more available to all who are providing care.

• It allows easy auditing of patient records in evaluating staff performance or quality of patient care.

• It requires continual evaluation and revision of the plan of care.

Disadvantages of the POMR method of documentation are as follows:

• It results in loss of chronologic charting.

• It is more difficult to track trends in patient status.

• It fragments data because of the increased number of flow sheets required.

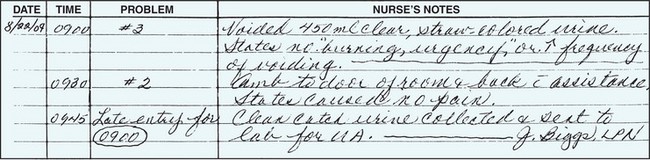

PIE Charting

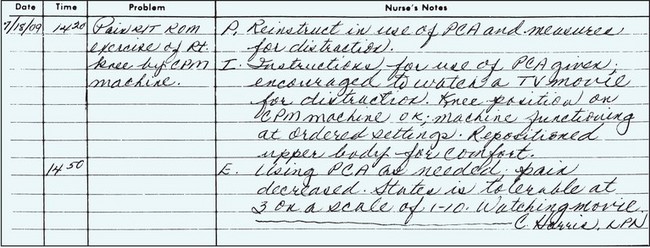

Another offshoot of this method is PIE charting: P’problem identification, I’interventions, and E’evaluation. This type of charting follows the nursing process and uses nursing diagnoses while placing the plan of care within the nurses’ progress notes. It differs from SOAP notes because it does not use a traditional nursing care plan or require narrative charting of the assessment data as long as they are normal. The problems, teaching, and discharge needs are listed underthe P of the PIE format. Nursing diagnoses are kept on a problem list (P), and each charting entry is marked with the problem number and title. With this method, the daily assessment information is placed on special flow sheets and duplication of the information is avoided. Interventions performed are documented under I. The outcomes of the interventions are evaluated and documented under E (Figure 7-4). When assessment data are abnormal, an A is added (APIE).

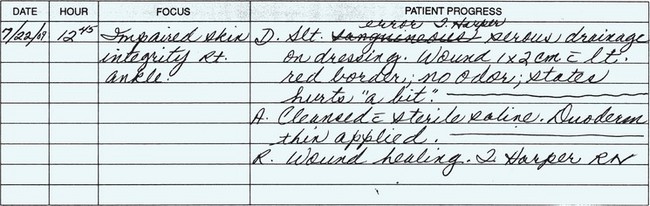

FOCUS CHARTING

Focus charting is similar to the POMR system but it substitutes focus for the problem, eliminating the negative connotation attached to “problem.” Focus charting is directed at a nursing diagnosis (e.g., pain), a patient problem (pressure sore), a concern (decreased food intake), a sign (fever), a symptom (anxiety), or an event (return from surgery). The note has three components: D’data, A’action, and R’response (DAR) or D’data, A’action, and E’evaluation (DAE) (Figure 7-5). The data component contains subjective and objective information that describes or supports the focus of the note. The action component includes interventions performed or to be implemented. The response component describes the outcomes of the interventions and whether the goal has been met.

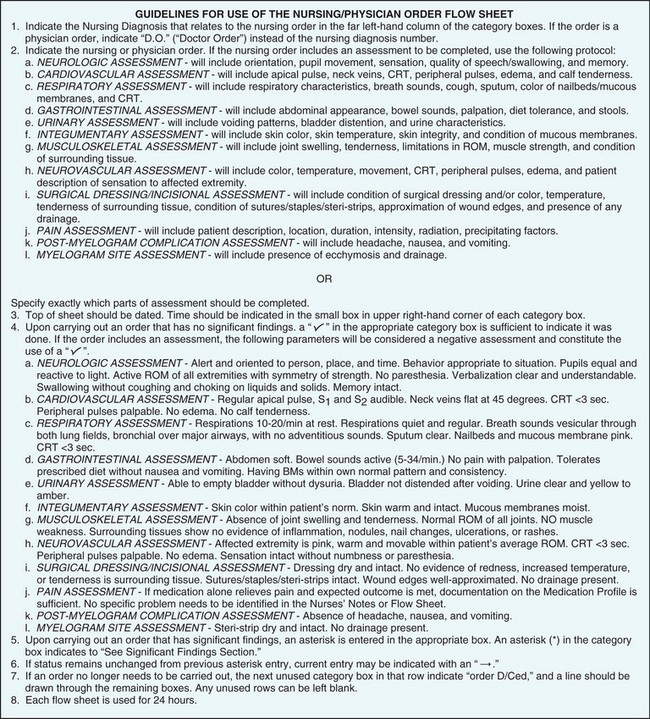

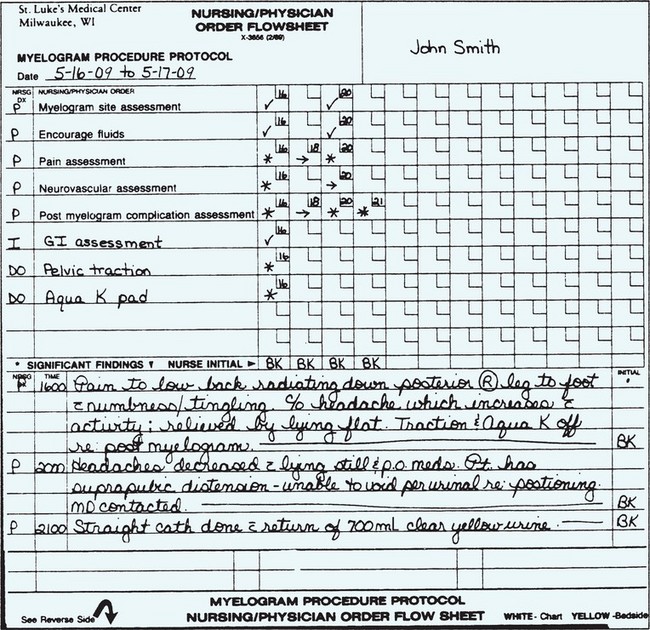

CHARTING BY EXCEPTION

Charting by exception was developed in the early 1970s by a group of nurses at St. Luke’s Medical Center in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The goal was to decrease the lengthy narrative entries of traditional charting systems and reduce repetition of data. Charting by exception is based on the assumption that all standards of practice are carried out and met with a normal or expected response unless otherwise documented. Agency-wide and unit-specific protocols (standard procedures) and standards of nursing care are the heart of the system. The standards and protocols are integrated into flow sheets and forms, and the nurse needs only to document abnormal findings or responses correlated with the nursing diagnoses listed on the nursing care plan (Figure 7-6). A longhand note is written only when the standardized statement on the form is not met (Figure 7-7, p. 93). Otherwise only a signature is necessary.

FIGURE 7-6 Guidelines for the use of the nursing or physician order flow sheet. These guidelines appear on the reverse side of the first page of the flow sheet.

FIGURE 7-7 Physical assessment documentation on a nursing or physician order flow sheet, with significant findings noted.

Charting by exception is the direct opposite of the adage, “If it wasn’t charted, it wasn’t done.” Charting by exception assumes that, unless documented to the contrary, all standards and protocols were followed and all assessment values were within accepted limits. This type of charting may present some problems with legalities when a chart is called into court because only abnormalities are documented in written words.

COMPUTER-ASSISTED CHARTING

An electronic health record (EHR) is a computerized comprehensive record of a patient’s history and care across all facilities and admissions. This type of record is a goal for the future for every patient. Systems are currently under design and study to accomplish this goal. Security and confidentiality of records are still major concerns (Legal & Ethical Considerations 7-1, onp. 94). Within a hospital system, computer records are protected by passwords and a firewall. With the addition of wireless technology for ease of entry from any place in the hospital, the security issues have increased. Each user who has access to a patient record must have a secure password. Passwords must be changed regularly in order to maintain security of the records. Encryption as well as authentication software is used when reports are transmitted outside of the health care facility campus.

Computerized provider order entry (CPOE) provides for efficiency of work flow because when orders are entered into the computer, there is automatic routing to the appropriate clinical areas for action. For example, a physician order for a new medication is ordered on the computer. That order is automatically posted to the electronic medication administration record (eMAR) for that patient. The order is always legible and transcribing errors are eliminated.

There are problems with the vocabulary used for computer entries in that terminology that is appropriate for the entire interdisciplinary team is needed. The Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms is a reference vocabulary developed for this purpose. This is important for evidence-based practice in order for researchers to understand the relationships in the data to predict trends and consequences of care (Lunney et al., 2005). At this time, it is difficult to integrate free-text narrative data into a controlled medical vocabulary for data mapping. Eventually software will be developed that can handle this aspect of documentation.

Health care agencies are moving toward electronic documentation of patient care. Documentation can be done as interventions are performed with the use of a roll-around bedside computer or a hand-held terminal carried from room to room (Figure 7-8). Computer-assisted charting can be cost-effective in terms of nursing time. Entries can be made at the point of care, at the time a change in condition is observed or a treatment is given. The information is fresh and no time has to be spent in recalling details or organizing events in sequence. If the system uses a drop-down table or menu to select from, you can quickly choose the appropriate description or intervention and do not have to key in free text. Test and diagnostic results can be electronically added to the medical record as they are received. This allows the information to be more rapidly available to the health care provider.

There are variations of computerized systems for charting. Any documentation system can be supported using electronic documentation. Some organizations use a combination of manual and electronic documentation. For example, some produce a flow sheet with the expected patient outcomes and nursing interventions listed. The nurse initials those interventions that were implemented, writes a narrative note for other necessary information, and adds the printout page to the chart. This adds some limited electronic functions to a basically manual system.

Other systems use the POMR format and produce a prioritized problem list. A plan of care is constructed by selecting the diagnoses, expected outcomes, and nursing interventions from specific screens on the computer and keystroking in required information. A touch screen may be part of the system for choosing the items on the screen.

A third type of system consists of selecting data from display screens to build the flow sheets and progress notes. The display screens are structured to allow documentation of current data and provide space for the addition of new findings. Much of the everyday care can be charted rapidly and completely in just seconds using such display screens. Often the progress notes from all disciplines involved in the patient’s care are integrated. A chart of vital sign trends or laboratory value trends can be printed very quickly. Figure 7-9 shows a printout of part of a patient’s electronic chart.

If an organization and medical community have fully implemented electronic health care records, clinical information from all sources will flow into the record. This results in a longitudinal medical record that will contain documentation of all the patient’s health care through time. The record is divided into episodes of care. An episode of care can occur in the outpatient or inpatient setting, any time the patient received medical assessment and/or medical intervention. As mentioned earlier, lab results, diagnostic imaging results, pathology reports, medication administration, and other information from all care delivery settings will be available via the electronic health care record. This provides virtually instant access to a complete medical history. Compare this to reviewing paper medical records from a variety of settings to assess a patient’s medical history.

At this time in today’s health care environment, a fully integrated electronic health care record is not common. There are multiple vendors for electronic health care record systems. Integration of these systems with an agency’s current needs requires computer programming and interfaces. These activities are expensive and time-consuming. Organizations must be prepared for a significant investment of time and finances to develop a true longitudinal electronic health care record.

Most commonly, organizations with an electronic medical record have a system that collects the health care record while the patient is within that system. The medical information is collected while the patient receives services as an inpatient or outpatient of that specific health care system. Physicians may be able to access health care information from that system from their offices. However, the clinic medical record and the hospital systems medical record may still remain separate and require access to both systems to review.

There are some considerations when using an electronic documentation system. One is confidentiality. Every individual who accesses the medical record has a password that is necessary for access to the assigned patient’s chart. Based on her position or job code, the person will be given a level of security that will allow access to only the specific information required for the job. When working on documentation at the computer, you should never leave the terminal while part of a patient’s chart is on the screen. Terminals should be situated so that passersby cannot view the information displayed. Organizations will have very specific policies outlining access, security, and use of the electronic health care record.

Electronic records place vital information instantly at the tips of the health care provider’s fingers because a review of previous problems, treatments, and responses can be viewed immediately. In 2006, The Joint Commission (formerly JCAHO) started requiring that a patient’s medical record must document his language and communication needs. When cultural information about the patient is entered, all of the health care team has access to it (Cultural Cues 7-1).

Advantages of computer-assisted documentation include the following:

• The date and time of the notation are automatically recorded.

• Notes are always legible and easy to read.

• There is quick communication between departments about patient needs.

• It allows multiple health care providers to access the same patient’s information at one time.

• If well designed, it can reduce documentation time.

• Electronic records can be retrieved very quickly (as long as the computer is up and running).

• If designed correctly, reimbursement for services rendered is faster and more complete because of complete and accurate documentation.

• A true electronic medical record can provide a complete longitudinal record of the patient’s medical history at one point of access.

• Well-designed integrated systems can reduce errors, thus having a positive impact on patient safety.

Disadvantages include the following:

• A very sophisticated security system is necessary to prevent unauthorized personnel from accessing patient records.

• Initial costs are considerable because many more terminals and an appropriate networking system must be purchased and interfaced for the system to work efficiently.

• Implementation of a full system can take a considerable length of time. This results in the need to use two systems, paper and electronic, during that transition.

• There is significant cost and time involved in training staff to use the system.

• Computer downtime can create problems of input, access, and transfer of information. Well-established backup plans (downtime procedures) must be developed.

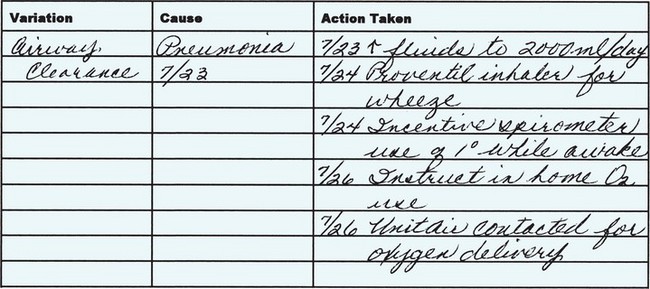

CASE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM CHARTING

Case management is a method of organizing patient care through an episode of illness so that clinical outcomes are achieved within an expected time frame and at a predictable cost (see Chapters 1 and 2). A clinical pathway or interdisciplinary care plan takes the place of the nursing care plan (see Figure 6-1). Documentation of variances is placed on the back of the pathway sheets. For example, a patient is admitted for abdominal surgery. The wound is healing well, but the patient develops pneumonia. The variance would be documented as in Figure 7-10.

THE DOCUMENTATION PROCESS

When documenting patient care, the patient’s needs, problems, and activities should be presented in terms of behaviors. The notes focus on the immediate pastand the present, never the future. For example, after assisting a patient to ambulate, you would chart something like “Ambulated 20 feet down the hall and back x3 with minimal assistance.”

Charting should be accurate, brief, and complete. When charting follows these guidelines, it presents a photographic view of the patient to anyone who reads the nursing notes.

ACCURACY IN CHARTING

Be specific and definite in using words or phrases that convey the meaning you wish expressed. Use of the words “appears to” or “seems” in phrases such as “appears to be resting” should be avoided. Chart the behavior; the patient either is or is not resting. Words that have ambiguous meanings and slang should not be used in charting. For example, how much is “a little,” “a small amount,” or a “large amount”? What do phrases such as “ate well,” “taking fluids poorly,” and “decubitus on sacrum” mean? Although such words give a general idea of what is meant, they are not specific. Someone else reading the notes will not know if the patient who “ate well” had a half a piece of toast, juice, and a cup of coffee or ate a bowl of cereal, scrambled eggs, two slices of bacon, 4 oz of orange juice, and two cups of coffee. Instead of charting a conclusion such as “taking fluids poorly,” chart the behavior and the specific amounts of liquid taken in a particular amount of time, such as “given fluids at frequent intervals, but takes only a few swallows; intake from 0700–1000: 30 mL of coffee, 60 mL of orange juice, and 50 mL of water.” Although a chart entry of “decubitus on sacrum” points to a patient problem, a better description is “skin of back clear, except for 4-cm reddened area over sacrum.” Specific data about size, amounts, and other measurements provide a means for determining whether the condition is getting better, getting worse, or staying the same. Rather than use the term “tolerated well,” describe what happened, even if it is a statement such as “walked in hall without problems.”

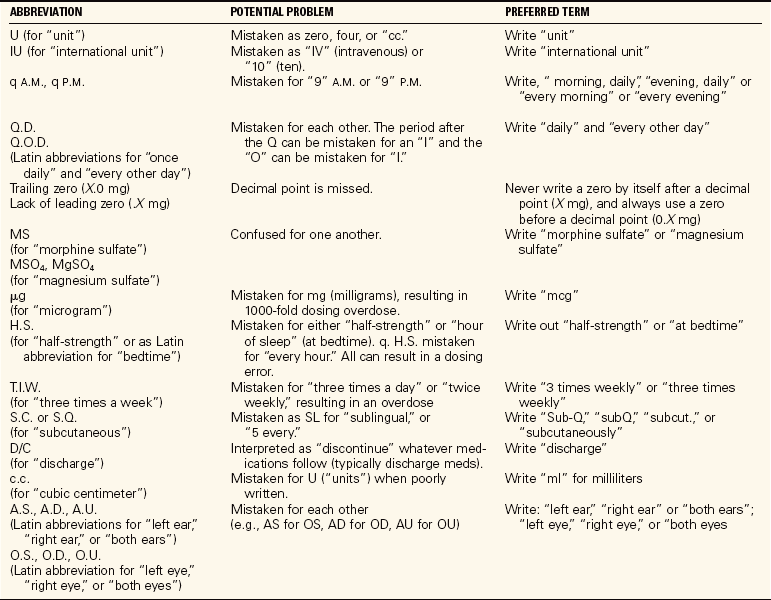

Table 7-3 provides a list of dangerous abbreviations, acronyms, and symbols that should not be used within a medical record.

BREVITY IN CHARTING

When charting, sentences are not necessary. Articles (a, an, the) may be omitted. Because the chart is about a particular patient, the word “patient” is left out whenever it is the subject of the sentence. Each statement should begin with a capital letter and end with a period. Rather than stating “Patient left for surgery via stretcher at 10:15,” simply state “To surgery via stretcher at 10:15.”

Abbreviations, acronyms, and symbols acceptable to the agency are used in charting to save time and space. Each agency has its own list of acceptable abbreviations and symbols. This list is usually found in the policy and procedures manual. A list of commonly used abbreviations and symbols is provided in Appendix 8.

You must choose which behaviors and observations are noteworthy or your nurse’s notes will be lengthy and irrelevant. In most agencies, if data are recorded on a flow sheet, they need not be documented again in the nurse’s notes. For example, the number of times the patient voids during the shift can simply be entered on the flow sheet under the proper section. No other notation is made in the nurse’s notes unless there was a problem or some significant data related to urination. A good way to begin to learn what should and should not be charted is to read over the notes of experienced nurses who are known to chart accurately and well. A rule of thumb is that if the behavior or finding is abnormal or a change from previous behavior or data, chart it.

LEGIBILITY AND COMPLETENESS IN CHARTING

Legibility is extremely important when charting. The medical record may be called into court, and what you wrote may be scrutinized and evaluated. If the writing is not easily legible, misperceptions of what was written can occur.

However, completeness is more important than brevity. You should record information about the patient’s needs and problems and also specify the nursing care given for those needs or problems. If you chart “Skin at IV site reddened and slightly swollen,” you must include a note about what you did about the problem. The full note should read “Skin at right forearm IV site reddened and slightly swollen in 4-cm area. IV dc’d and warm moist pack applied for 20 minutes. Redness and swelling receding. IV restarted in left hand with 20-ga catheter.”

What constitutes complete charting may vary among hospitals, extended-care facilities, and other health care agencies. Home care charting must particularly note safety factors in place and the need for continued care (Figure 7-11). Long-term care facilities may require only a monthly summary for patients in stable condition or a note when their condition changes (Figure 7-12), whereas hospitals caring for acutely ill patients require continual documentation of the patient’s condition, with entries made every few hours. For completeness in charting about a sign or a symptom of the patient, note something about each of the seven factors listed in Box 7-1.

WHAT TO DOCUMENT

In addition to assessment data related to signs and symptoms, information on the topics in Box 7-2 is to be documented either on flow sheets or in the nurse’s notes. The charting examples included with the procedures throughout this book show how to describe different types of information.

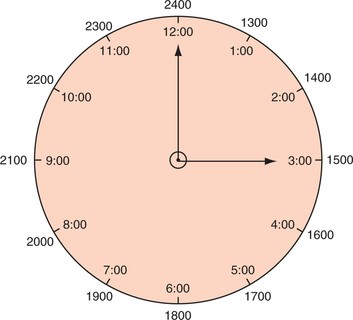

General Charting Guidelines

In addition to those mentioned above, there are several other general rules to consider when charting. They are presented in Box 7-3. Figure 7-13 (p. 102) shows the use of regular versus military time for chart entries.

THE KARDEX

Many organizations have eliminated the use of the Kardex. If it is used, however, it needs to be up to date. Though it is not a part of the permanent medical record, the Kardex is a quick reference for current information about the patient and ordered treatments. When used, it is kept at the desk with the unit secretary. It usually consists of a folded card for each patient in a holder that can be quickly flipped from one patient to another. The unit secretary and the primary nurse assigned to the patient update the information daily. Information kept on the Kardex includes the following:

• Room number, patient name, age, sex, admitting diagnosis, and physician’s name

• Scheduled tests or procedures

• Notations regarding tubes, machines, and other equipment in use

• Nursing orders for assistive or comfort measures

Hospitals that have instituted a completely computerized patient care system may not have this type of Kardex anymore. In its place, worksheets or working care plans are printed out for each patient each shift. The nurse assigned to the patient receives the printed sheet or reviews an electronic plan of care before or during the report on patients from the previous shift. The unit secretary has a census sheet or an electronic census board listing the room numbers, patient names, and diagnoses. For the computerized system, these sheets are automatically updated as new orders are keyed into the computer.

The printed working care plans can be used to organize your work. They also serve well if you write pertinent information that will be needed for charting onto the form as you work. Noting the time at which PRN (as necessary) medications are given, the amounts of intake and output, vital signs, wound appearance, and so on makes it easy to chart the information quickly once the chart is in hand or you are at the computer terminal. When using a printed care plan, it is important to remember that the printed sheet is only as current as the time it was printed. If orders have changed or been added, you must look at the electronic medical record. When an electronic system is used, staff should use the electronic system and not depend on printed reports.

If used, the Kardex can be a reference when giving a report on your patients. It also serves as a quick reference guide for the unit secretary in locating patients and when answering staff questions related to a particular patient. Although it takes time and practice to learn to chart efficiently and well, it is a major part of a nurse’s job and should be viewed as an important skill.

Documentation of medication administration is covered in Chapter 34.

NCLEX-PN® EXAMINATION–STYLE REVIEW QUESTIONS

Choose the best answer(s) for each question.

1. Which accreditation agency provides the guidelines for required documentation?

2. When an error is made in charting, the nurse remedies it by:

1. lining out the entry, dating it, and initializing it.

2. recopying the sheet and destroying the original.

3. Patients frequently request copies of their medical records. You understand that:

1. they have a right to a copy of their record after discharge.

2. only health care staff have the right to read the record.

3. the patient and family have a right to read the record.

4. the physician must write an order for the release of the record.

4. One characteristic differentiating source-oriented (narrative) charting from POMR charting is:

1. a specific order of forms in the chart.

2. a focus on the patient’s problems.

3. the separation of notes on medical care and nursing care.

5. When charting, it is wise to always:

1. include the names of all visitors with the time of the visit.

2. check that you are on the right chart or screen and on the right date.

6. When a patient’s medical record is needed as evidence for a legal action, you are aware that the record is the property of:

7. The advantage of POMR charting when using an interdisciplinary care system is that:

1. all charting is done on flow sheets.

2. not as many flow sheets are used.

8. The assumption in charting by exception is that:

1. if it was not charted, it was not done.

2. patient care is charted chronologically.

3. unless otherwise documented, all standards have been met.

9. An advantage of computer charting is that:

1. computers are always up, running, and available.

2. security of information is guaranteed with the computer system.

3. others can see what is being input as the nurse works with the charting screens.

4. it is cost-effective because it saves nursing time compared to writing out notes.

10. When charting the patient’s condition and nursing care, the nurse records: (Select all that apply.)

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES ? Read each clinical scenario and discuss the questions with your classmates.

Read the following scenario and then write out a POMR progress note and a focus charting note using the data given.

Marvin Barnes was admitted with impaired gas exchange r/t excessive pulmonary secretions. When you go to assess him, you discover that his temperature is 102.6° F (38.9° C), pulse 77, respirations 26 and shallow, and blood pressure 147/92 mm Hg. He is coughing and produces yellow-green sputum. He is having difficulty stopping the cough. He has oxygen via nasal cannula running at 3 L/min. He has acetaminophen ordered for fever over 100.2° F (38° C). You tell him that you will be back with medicine for his fever and that you will call the physician for an order for some cough medicine to relieve the cough.