Lifting, Moving, and Positioning Patients

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Describe the anatomy and function of the musculoskeletal system.

2 Explain the importance of proper body mechanics, alignment, and position change for both patient and nurse.

3 Discuss the principles of body movement and positioning, giving an appropriate example for each principle.

4 Identify ways to maintain correct body alignment of the patient in bed or in a chair.

5 Describe the proper method for transferring a patient between wheelchair and bed.

1 Correctly position a patient in the following positions: supine, prone, Fowler’s, and Sims’.

2 Assist patients to sit up in bed.

3 Demonstrate complete passive range-of-motion (ROM) exercises for a patient.

4 Correctly transfer a patient from a wheelchair to a bed.

5 Transfer a patient from a bed to a stretcher.

6 Demonstrate the correct techniques for ambulating a patient and for breaking a fall while ambulating.

alignment ( , p. 258)

, p. 258)

ambulate ( , p. 263)

, p. 263)

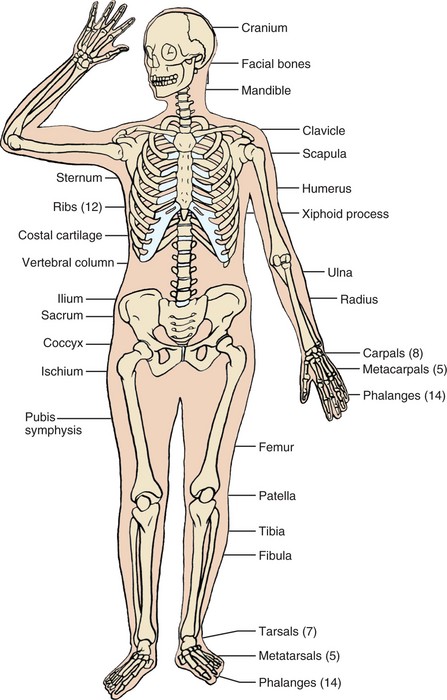

bone (p. 259)

bursa ( , p. 259)

, p. 259)

cartilage ( , p. 259)

, p. 259)

contractures ( , p. 262)

, p. 262)

dangling (p. 277)

Fowler’s position ( , p. 264)

, p. 264)

gait (p. 263)

gait belt (p. 282)

joint (p. 259)

kinesiology ( , p. 258)

, p. 258)

lateral position (p. 264)

ligaments ( , p. 259)

, p. 259)

logrolling ( , p. 272)

, p. 272)

necrosis ( , p. 262)

, p. 262)

pivot ( , p. 262)

, p. 262)

pressure ulcers ( , p. 262)

, p. 262)

prone position ( , p. 264)

, p. 264)

semi-Fowler’s position ( , p. 264)

, p. 264)

shearing force ( , p. 262)

, p. 262)

side-lying (lateral) position ( , p. 264)

, p. 264)

Sims’ position (p. 264)

skeletal muscles (p. 259)

supine position ( , p. 263)

, p. 263)

symmetry ( , p. 262)

, p. 262)

tendons (p. 259)

transfer belt (p. 282)

Lifting, moving, and positioning patients is an integral part of your workday. In order to provide the best patient care and to prevent self-injury, you must know the principles of body mechanics. Coordinated movement involves using the bones, joints, and skeletal muscles properly. Some hospitals and institutions are moving to a policy of “no manual lifting” or to the use of a lift team. The goal of this change is to decrease health care worker back injuries from repetitive lifting. The shift in policy is slowly occurring across the United States. Until equipment or lift teams are in place in all health care institutions, there will be instances when a nurse must lift a patient without assistance or use of a mechanical device. The following principles and practices serve as guides to help prevent injury.

PRINCIPLES OF BODY MOVEMENT FOR NURSES

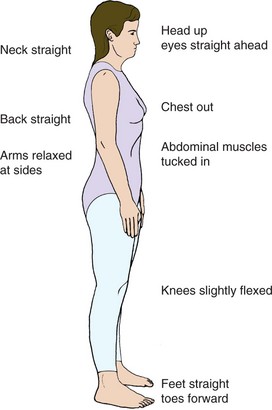

Kinesiology is the study of the movement of body parts (also called body mechanics). There are two main reasons why the use of good body movement is important for you and your patient. The first reason is that the body functions best when it is in correct anatomic position or alignment (arrangement in a straight line, bringing a line into order). Correct body alig nment is generally called “good posture” (Figure 18-2). The second reason for proper body movement is to prevent injuries. One of the most common injuries for health care workers is lower back strain. With proper use of body mechanics, many of these injuries can be avoided.

In today’s health care environment, more patients are being cared for at home. In order for these people and their caregivers to be safe, everyone must use correct lifting, moving, and positioning techniques (Box 18-1).

OBTAIN HELP WHENEVER POSSIBLE

Although it is possible to move and position patients independently, additional help is desirable. Combining the efforts of two nurses to change a patient’s position divides the work. Each nurse has less weight or fewer parts of the body to move. Sometimes it may seem difficult to find another staff person to assist you. It is always better to wait for help than to risk injury to yourself or the patient. Encourage the patient to assist when transferring and moving if possible. Use devices such as mechanical lifts and transfer or roller boards where available. Properly used, these items decrease the workload and prevent injury.

USE YOUR LEG MUSCLES

In positioning and transferring, use the muscles in your legs as much as possible. Instead of bending over at the waist to pick up something from the floor, bend at the knees and lower yourself until you can pick up the item without straining your back (Figure 18-3). Use the greatest number of muscles possible when lifting or moving an object. For instance, when turning a patient in bed, flex your knees and use the muscles in your legs as well as your arms. Without the power in your legs, there will be more work for the muscles in your arms. It is far better to use thigh, arm, and leg muscles rather than back muscles.

PROVIDE STABILITY FOR MOVEMENT

Keep your feet about shoulders’ width apart. This establishes a wide base of support and provides stability for movement. Think how easy it is to sway if you stand with your feet together and your eyes closed. Yet, if you spread your feet apart and close your eyes, you do not sway.

USE SMOOTH, COORDINATED MOVEMENTS

Use smooth, coordinated movements instead of jerking or sudden pulling motions. To coordinate effort, tell the patient and other staff members to move, lift, or pull “on the count of 3.” This will help to ensure that everyone is working at the same time to maximize the effort and decrease the individual load.

KEEP LOADS CLOSE TO THE BODY

Keep your elbows and work close to your body. This keeps the work load close to your waist and center of gravity. Pick up your textbook and hold it close to your body. Although it is a heavy book, it is easily managed close to your center of gravity. Slowly start to extend your elbows forward. This moves the book farther from the center of gravity and it becomes increasingly heavier. Do not fully extend your elbows or you will put stress and strain on your back muscles.

KEEP LOADS NEAR YOUR CENTER OF GRAVITY

Work at the same level or height as the object to be moved (Figure 18-4). This way your work load is near your center of gravity. Changing bed linens is a good example of this principle. In most institutions, the bed’s height may be adjusted. When changing linen or moving a patient, raise the bed to about waist level to keep the work near your center of gravity. Injuries are more likely to occur the farther away the work is from the center of gravity.

PULL AND PIVOT

Pulling actions require less effort than pushing or lifting. Whenever possible, use pulling motions. When transferring a patient to a stretcher, two nurses should stand on the far side of the stretcher to pull the patient toward them onto the stretcher. This movement is easier than pushing because it brings the patient closer to each nurse’s center of gravity. Face in the direction of the movement. It is much easier to move an object if you are facing in that direction. For example, place an object on the floor. Stoop down with the object in front of you and move the object forward. Fairly easy. Now place the same object on the floor, stoop down, only this time with the object to the side. Moving the object forward is not as easy in this instance.

In order to move the object at your side forward, you would need to twist to the side. To maintain proper body mechanics, keep your trunk straight when lifting or pulling. Twisting should be avoided. Instead, if turning is needed, pivot (turn or change direction with your feet while remaining in a fixed place). Pivoting prevents twisting, which can lead to back strain and injury.

PRINCIPLES OF BODY MOVEMENT FOR PATIENTS

Body movement and alignment are also important for patients. Many patients are unable to change position or move in bed independently. There are two basic principles for patients:

If these principles are not observed, the patient may experience complications.

HAZARDS OF IMPROPER ALIGNMENT AND POSITIONING

The hazards of improper alignment and positioning include

• Interference with circulation, which may lead to pressure ulcers (ulcers that form from local interference with circulation)

• Muscle cramps and possible contractures (resistance to stretch in damaged muscle that pulls a joint into a fixed or “frozen” position)

Contractures, muscle cramps, and respiratory problems as complications of immobility are discussed more thoroughly in Chapter 39.

Pressure Ulcers

Pressure ulcers, also known as decubitus ulcers or bedsores, occur from pressure on the skin. This pressure causes a local area of tissue necrosis (local death of tissue from disease or injury). Most often the area of pressure occurs between a bony prominence and an external surface. Besides pressure, the other main factor in the development of pressure ulcers is a shearing force. Shearing is an applied force that causes a downward and forward pressure on the tissues beneath the skin. Shearing forces occur when a patient slides down in a chair, if bedclothes are pulled from beneath the patient, or the patient is slid up to the head of the bed without lifting the body. More information on pressure ulcers may be found in Chapter 19.

APPLICATION of the NURSING PROCESS

When assessing the standing patient’s body alignment, begin by noting the head position in relation to the rest of the body (see Figure 18-2). Is the head centered and erect? Are the shoulders and hips parallel? Are the knees and ankles slightly flexed and parallel to the hips and shoulders? Do the arms hang comfortably at the patient’s side? Are the feet slightly apart to provide a base of support? During the assessment, also observe for any muscle weakness or paralysis, and check symmetry (equality in size, form, and arrangement of parts on the opposite sides of a plane; a mirror image) of extremities.

When a patient is sitting, again observe for symmetry (Figure 18-5). Determine if the patient’s head is erect and centered over the shoulders. Are the but tocks in the same plane as the shoulders and are the thighs in line with the shoulders? The patient’s weight should be distributed evenly over the buttocks and thighs. The knees should be flexed at about 90 degrees with the feet resting comfortably on the floor. Provide a footstool if the feet do not reach the floor. The arms should lie comfortably in the lap or be supported by the chair armrests.

Patients often lie on their back when in bed. It is important that this position be changed frequently to prevent the problems associated with immobility. Support the head with one pillow so the neck is not hyperflexed. The vertebral column should be centered and in alignment and there should not be any observable curves. The mattress should support the body in this position.

Assess the patient’s ability to ambulate (walk) and to change position independently. (A physician’s order is needed for a patient to be out of bed.) Observe the patient walking. Is the head centered over the vertebral column? Is the gait (style of walking) even and unlabored? Is the patient balanced? Is there any weakness or favoring of one side? This will determine the patient’s ability to ambulate independently or determine the type of assistance needed.

Nursing Diagnosis

Nursing diagnoses commonly used for problems with body movement are as follows

The defining characteristics for the patient are added to the nursing diagnosis stem to individualize the care plan. Nursing diagnoses for patients with problems of immobility are covered more extensively in Chapter 39.

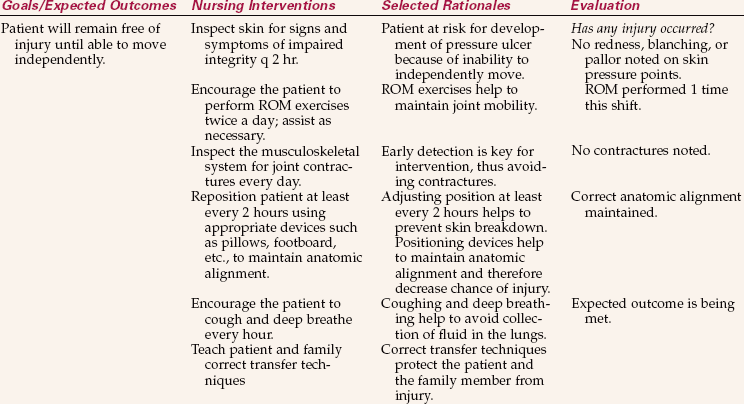

Planning

The data collected during the assessment phase give information about how to best promote independence or assist the patient. If the patient is not able to move independently, then the patient’s position will need to be changed at least every 2 hours to avoid complications. Your assessment will indicate whether you can move the patient independently or you will need assistance. During planning, decide how to change the patient’s position and whether you can delegate this task to assistive personnel.

The home setting must also be considered when planning care for the patient. Will the family be able to turn or assist in turning the patient correctly after discharge? Will the patient or family need any assistive devices, and do they know how to use them? Will extra pillows need to be purchased to assist with positioning? Will the patient be able to get around in and out of the home independently? Assessment and planning will answer these questions.

Expected outcomes are written for each nursing diagnosis. Examples related to the above nursing diagnoses might be as follows:

Implementation

Positioning: Basically, changing position accomplishes four things: (1) it provides comfort; (2) it relieves pressure on bony prominences and other parts; (3) it helps prevent contractures, deformities, and respiratory problems; and (4) it improves circulation. It is essential to know how to correctly support and position the patient while maintaining good body mechanics.

Common Positions and Their Variations: While in bed, there are three basic positions for the patient: supine, side-lying, and prone.

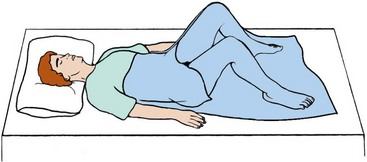

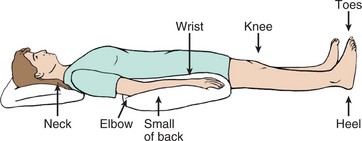

The supine position is when patients are resting on their back. It is recommended after spinal surgery and after the administration of some types of spinal anesthetics. The supine position is similar to proper standing alignment except that the body is in the horizontal as opposed to the vertical plane.

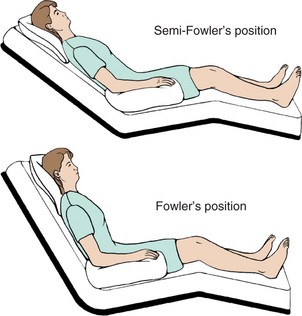

Variations of the supine position are Fowler’s, semi-Fowler’s, and low Fowler’s positions. Fowler’s position is arranged by elevating the head of the bed 60 to 90 degrees. Semi-Fowler’s position is an elevation of 30 to 60 degrees, and low Fowler’s is an elevation of 15 to 30 degrees. Unless contraindicated, the knees can be raised 10 to 15 degrees in these positions. Alternatively, a footboard can be placed at the bottom of the bed to brace the patient’s feet in correct alignment. Cardiac output and respiration are improved and urinary and bowel elimination are promoted in these positions. Do not place a patient who had abdominal surgery in a Fowler’s position unless ordered. Elevation of the knees above 15 degrees is contraindicated in elderly and postoperative patients because it is associated with decreased circulation of the lower extremities; check the orders. Fowler’s position may help the patient who has had a stroke and has paresis to swallow food and secretions.

Dorsal recumbent and dorsal lithotomy positions are other variations of the supine position. In the dorsal recumbent position, patients are on their back with knees flexed and soles of the feet flat on the bed (Figure 18-6). This is used for a variety of procedures and examinations. The dorsal lithotomy position (Figure 18-7) is used for examining the pelvic organs. It is like the dorsal recumbent position except the feet are usually placed in stirrups and the legs are spread farther apart and abducted. Patients with joint problems or arthritis may have difficulty assuming this position.

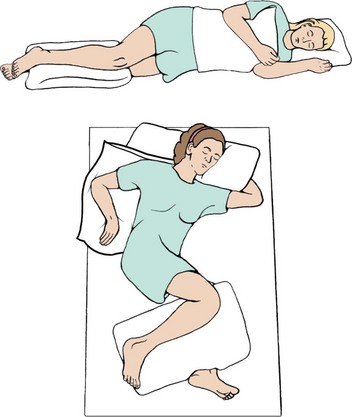

The side-lying or lateral position is achieved by having patients rest on their side. It alleviates pressure from bony prominences on the back. The major portion of the patients’ weight is on the dependent shoulder and hip. Maintain the vertebral column in proper alignment as if they were standing. The oblique side-lying position removes pressure from the dependent shoulder and hip and is easier for patients to maintain.

Sims’ position is a variation of the side-lying position. It is used for rectal examinations, administering enemas, or inserting suppositories, or for an unconscious patient. The distribution of weight is different from the side-lying position because in the Sims’ position the weight is distributed over the anterior ilium, humerus, and clavicle. When positioning on the left side, place the left arm behind the patient and draw the right knee and thigh up above the left lower leg. Tilt the chest and abdomen forward so the patient is resting on them as well.

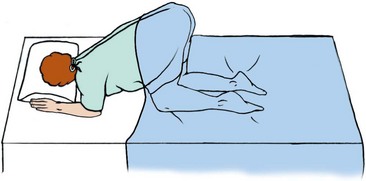

The prone position is when the patient is lying face down. It provides an alternative for patients who are on prolonged bed rest or are immobilized. Spinal cord–injured patients often use this position. The position is generally not well tolerated because it is boring. In the prone position, for patients who have not had a spinal cord injury, turn the head to one side or the other and support with a small pillow. If the head is not turned, or the patient is not on a special bed with a removable piece at the head, the patient would not be able to breathe.

The knee-chest position is a variation of the prone position (Figure 18-8). The patient is face down on the bed with the head turned to one side. The chest, elbows, and knees rest on the bed and the thighs are perpendicular to the bed. The lower legs rest flat on the bed. This is used for rectal examinations and as a method to restore the uterus to a normal position. Do not leave the patient alone in the knee-chest position because the patient may become dizzy, faint, or fall. A patient with arthritis or joint abnormalities may not be able to assume this position.

Skill 18-1 describes how to place the patient in many of the above positions.

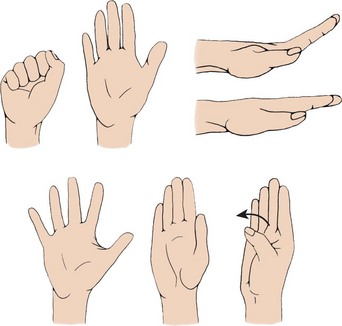

Positioning Devices: Devices used for positioning include pillows, boots or splints, footboards, cushioned boots or high-top sneakers, a trapeze bar (Figure 18-9, A, p. 269), sandbags, hand rolls, trochanter rolls (Figure 18-9, B), side rails, and bed boards. Pillows are used to support the body or extremities and elevate body parts. Boots or splints help to maintain dorsiflexion of the feet and may help to prevent heel pressure. Footboards and high-top sneakers are other devices used to maintain foot dorsiflexion. Trochanter rolls prevent external rotation of the hips and legs when a patient is lying in a supine position. Sandbags immobilize an extremity, provide support, and maintain correct body alignment. Hand rolls and splints for the hands and wrists help to prevent contractures of the hands, promote thumb adduction, keep the fingers slightly flexed, and prevent dorsiflexion of the wrist. A trapeze bar allows a patient to adjust position by enabling the trunk and buttocks to be raised off the bed. The patient may use it to help with moving up in bed or transferring from bed to wheelchair and to strengthen upper extremities. Side rails assist the patient to change position and turn in bed. Bed boards are boards that are placed under the home mattress to give more support to the mattress and thereby improve vertebral alignment.

Moving Patients Up in Bed: Patients need different amounts of help moving in bed. After proper instruction, many are able to reposition and move themselves up in bed independently. Other patients are able to provide assistance after they are told what is expected of them. Totally dependent patients rely on the nursing staff for this procedure. Before moving a patient up in bed, one of the most important steps is to determine how much help will be needed. If lift equipment is available, use it. When manually lifting, if there is any doubt about whether a patient is too heavy or immobile to be moved by you, at least one other person’s help should be enlisted. Skill 18-2 describes how to move patients up in bed.

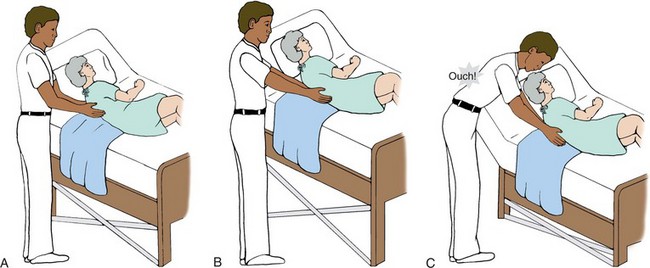

One of the techniques to move patients in bed is called logrolling. Logrolling is turning the patient as a single unit while maintaining straight body alignment at all times. Logrolling is often used for patients with injuries or surgery to the spine and for those who must avoid twisting. The linens for an occupied bed are often changed by using the logrolling turn. Logrolling can be done either with or without a lift sheet. If a lift sheet is used, two or three people are needed to accomplish the move, depending on the size of the patient (Figure 18-10). It takes at least two other people to assist when logrolling a patient without a lift sheet (Figure 18-11).

When using a lift sheet, you and preferably two other assistants stand on opposite sides of a locked, flat bed at waist level. Leave a pillow under the patient’s head and lower the side rails. Place a pillow or two, if needed, between the patient’s legs. All the nurses face the bed with one foot slightly in front of the other. Roll the lift sheet close to the patient’s body and, on the count of 3, lift the patient to one side of the bed, keeping the body in straight alignment. By lifting the patient to one side of the bed first, the patient should be centered in the bed after being logrolled. The tallest nurse is positioned on the far side of the bed and should be at the middle portion of the patient. The other two nurses are positioned one at the shoulders and neck and one at the legs and feet of the patient so that they can control movement of these parts. The nurse on the far side of the bed grasps the lift sheet. Again, the sheet is held as close to the patient’s body as possible, and on the count of 3 the patient is rolled in one smooth, coordinated, even motion with the body in straight alignment. The pillow is rearranged under the patient’s head and any other positioning devices are placed before lowering the bed and putting the call bell within the patient’s reach.

Logrolling without a lift sheet is accomplished in a similar manner. Three nurses are evenly spaced along one side of a locked, flat bed at waist level. One nurse supports and rolls the head, neck, and shoulder region; one supports and rolls the waist and hips; and the third supports and rolls the thighs and lower legs.

Therapeutic Exercise: Physical therapy is often ordered for the patient who is immobilized for an extended period of time. The physician indicates the patient’s problems, and the therapist performs an evaluation and then designs an exercise program to help the patient and to prevent further musculoskeletal problems from occurring. If a physical therapist is not available, you will need to assist your patient in performing these exercises. The family and/or significant other can also be shown how to assist the patient with exercise.

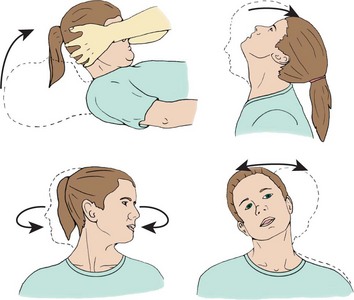

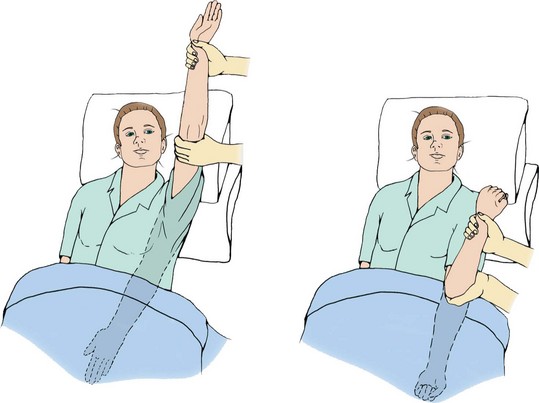

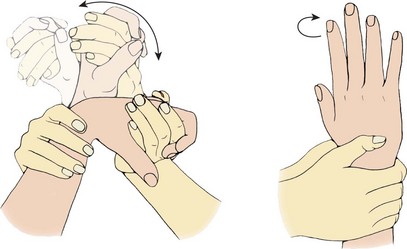

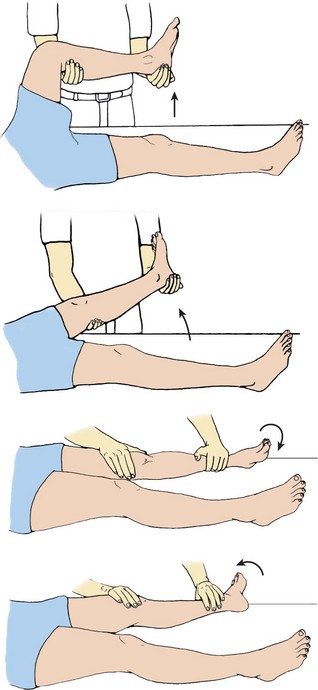

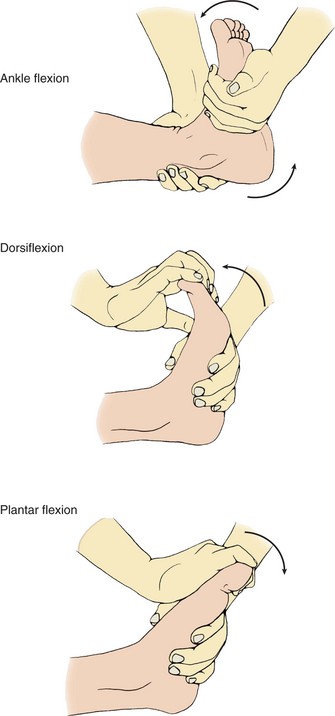

Full range-of-motion (ROM) exercises should be performed either actively or passively several times a day. Active ROM exercises are used for the patient who independently performs activities of daily living but for some reason is immobilized or limited in activity or is unable to move one extremity due to injury or surgery. Passive ROM exercises are performed on the patient who cannot actively move. This patient cannot contract muscles, so muscle strengthening cannot be accomplished. All muscles over a joint are maximally stretched to achieve or maintain flexibility of the joint. This is accomplished by moving the muscles to the point of slight resistance but not beyond. To prevent joint injury in performing passive ROM exercises, support the limb to be exercised above and below the joint. Principles related to carrying out ROM exercises for patients are listed in Box 18-2. Skill 18-3 describes how to provide passive ROM exercises.

Lifting and Transferring: Lifting and transferring patients also require the use of proper body mechanics and positioning principles. Some patients may be independent or need minimal assistance to ambulate. Others may need to be transferred to a chair, wheelchair, or stretcher.

Before transferring a patient to a wheelchair, have her dangle her legs over the side of the bed first (Figure 18-12). Dangling is the term used for the patient position of sitting on the side of the bed with the legs and feet over the side. The feet are either on the floor or supported on a footstool. Dangling is often the first step before sitting in a chair or ambulating. The purpose is to gradually accustom the body to the position change. While the patient is dangling, assess the patient’s balance, and monitor for orthostatic hypotension, dizziness, or nausea before getting the patient out of bed. If a patient has been on prolonged bed rest, she may only be strong enough to dangle for a few minutes and then will need to lie down again.

Wheelchairs are often used to transport an ambulatory patient to different areas for tests and procedures, or for the patient who is unable to walk or tolerate the fatigue associated with the effort. Either lift equipment or two nurses should transfer a patient to a wheelchair if the patient is unsteady, weak, or heavy (check agency policy) (Figure 18-13). Transferring a patient to a wheelchair is described in Skill 18-4.

Stretchers may also be called litters, gurneys, or carts. They are used for transporting a patient who is unable to sit in a wheelchair or is having certain tests or procedures done’for example, surgery. Stretchers have side rails and a safety belt that should be secured before moving the patient (Safety Alert 18-1).

Moving a wheelchair or a stretcher is an exception to a principle of body mechanics discussed earlier in this chapter. Both devices are pushed rather than pulled. To pull a wheelchair or stretcher would cause back strain and twisting.

Transferring Devices: Devices that may be used in lifting and transferring patients include mechanical lifts, lift or pull sheets, roller boards, slide boards, and transfer or gait belts. Mechanical lifts are discussed in Chapter 39. Lift sheets are often used to move and transfer a patient. Transferring a patient to a stretcher is discussed in Skill 18-5. Lift sheets may be used alone or with the following devices to help maintain the patient’s alignment during a transfer.

A roller board consists of several roller bars between fixed end bars. The bars are enclosed in a vinyl covering that allows the bars to turn when something or someone is pulled over top of the roller board. It works similar to a conveyor belt.

To use a roller board to transfer a patient to a stretcher, turn the patient to one side and place the roller board and lift sheet underneath the patient. Return the patient to a supine position and place the stretcher against the bed with the side rail down. Lock the stretcher wheels. One or more nurses are on the far side of the bed and you and another nurse are on the far side of the stretcher. The lift sheet is held as close to the patient as possible. On the count of 3, the patient is pulled across the roller board. The nurse(s) on the far side of the bed support the patient’s head and feet and help guide the patient to the stretcher. A slide board works similarly to a roller board except that it does not roll. It has a slippery surface that allows the patient on a lift sheet to be slid across it to a stretcher or to a wheelchair.

A transfer belt or gait belt may be used to ambulate and/or transfer the weak or unsteady patient. It is made of a tightly webbed canvas material and is very sturdy. Place and buckle the belt around a patient’s waist before having the patient stand. It needs to be tightened just enough to allow space for your hand to grasp it from the rear. Insert your hand into the belt from the bottom so that, if the patient falls, you will be able to support the weight. If you hold the belt from the top, it could slip out of your hand from the patient’s weight during a fall. Skill 18-6 discusses how to assist a patient to ambulate and how to break a fall.

Evaluation

During evaluation, determine whether the expected outcomes and goals from the planning phase have been met. Evaluate your own use of proper body mechanics. Feedback from the patient and other personnel should be obtained regarding positioning and transfers. Did you position the patient safely and correctly? Was the patient comfortable when you finished, or did you need to readjust the position? Did pressure areas develop on the skin? If the plan needs to be changed, document the changes for other personnel. Record the progress achieved in meeting the goals and outcomes (Nursing Care Plan 18-1).

Practicing the techniques of proper body mechanics and alignment will increase your confidence in being able to safely move and position any patient. Using your muscles and these techniques correctly will help protect your back. Preventing back injuries is a major concern for all health care professionals.

NCLEX-PN EXAMINATION–STYLE REVIEW QUESTIONS

Choose the best answer(s) for each question.

1. An elderly person may need to be reeducated on how to lift safely because: (Select all that apply.)

2. When moving the patient up in bed:

1. place one foot in front of the other.

2. use only those muscles absolutely necessary.

3. Forgetting to reposition a patient in a wheelchair for more than 1 hour may lead to:

4. When preparing to move a patient up in the bed who can assist, you would first:

1. pull the bed covers down to the foot of the bed.

2. raise the bed to a good working height.

3. ask the patient to grab the upper guard rails.

4. ask the patient to bend the knees and plant the feet on the mattress.

5. The oblique side-lying (lateral) position is helpful because:

1. the patient does not need to be repositioned as often.

2. it takes pressure off of the trochanter and shoulder.

3. all areas of the lung will drain secretions to the bronchus.

6. When placing the elderly patient in Fowler’s position, you must:

1. raise the head of the bed to 45 degrees.

2. use at least five pillows for positioning.

7. When changing the patient’s position:

1. use only those muscles absolutely necessary.

2. stand with feet close together for greater strength.

8. A common pressure point for a patient in the supine position is the:

9. When performing passive range-of-motion exercises:

1. help patients who are independently performing these activities.

2. avoid moving the joint to the point of discomfort.

3. perform each exercise at least 15 to 20 times.

4. support the extremity above the joint to promote movement.

10. When a patient falls, you document in the nurse’s notes:

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES ? Read each clinical scenario and discuss the questions with your classmates.

You are to get a patient who has left-sided paresis out of bed and into a chair for the first time. The patient has been in this country only a short time. How would you go about doing this? Would you need assistance?