Diet Therapy and Assisted Feeding

Objectives

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

Theory

1 Identify the role of the nurse related to diet therapy and special diet.

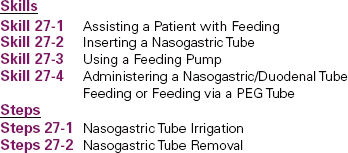

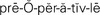

2 Compare and contrast a full liquid diet with a clear liquid diet.

3 Describe health issues related to nutrition.

4 List disease processes that may benefit from diet therapy.

5 Verbalize the rationale for tube feedings.

6 List the steps for the procedure to insert, irrigate, and remove a nasogastric tube.

7 Discuss the procedure for tube feeding.

8 Identify the medical rationale and nursing care for a patient receiving total parenteral nutrition (TPN).

Clinical Practice

1 Develop a teaching plan for nutritional therapy.

2 Utilize therapeutic communication with a patient who needs a special diet.

3 Demonstrate insertion, irrigation, and removal of a nasogastric tube.

4 Demonstrate feeding a patient through a nasogastric tube or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube.

Key Terms

anorexia nervosa ( , p. 486)

, p. 486)

atherosclerosis ( , p. 489)

, p. 489)

bulimia ( , p. 487)

, p. 487)

congestive heart failure (CHF) ( , p. 489)

, p. 489)

diabetes mellitus ( , p. 489)

, p. 489)

dysphagia ( , p. 492)

, p. 492)

feeding pump (p. 498)

gastrostomy tubes ( , p. 492)

, p. 492)

glycosuria ( , p. 498)

, p. 498)

hyperosmolality ( , p. 502)

, p. 502)

hypertension (p. 487)

jejunostomy or duodenal tubes ( , p. 493)

, p. 493)

myocardial infarction (MI) (p. 489)

nasogastric tubes ( , p. 492)

, p. 492)

NPO (p. 486)

percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes ( , p. 492)

, p. 492)

postoperative (p. 486)

preoperatively ( , p. 486)

, p. 486)

residue (p. 486)

total parenteral nutrition (TPN) ( , p. 502)

, p. 502)

THE GOALS OF DIET THERAPY

The goals of diet therapy are to treat and manage disease, prevent complications, and restore health through appropriate diet. Patients in hospitals and other health care facilities have multiple dietary needs due to disease processes, surgical procedures, physical health, and cultural, religious, and individual preferences. The specific diet for each patient is prescribed on the physician’s order sheet. Some patients may have diets without restrictions that are similar to meals eaten at home. For other patients, diet therapy is a significant factor in their medical treatment. You can assist patients to meet their nutritional goals by completing a thorough nutritional assessment. The patient’s food and fluid intake should be monitored and the response to therapy documented. Weight gain or loss, percentage of meals eaten, and ability to tolerate the diet should be included in the documentation. Modification of the diet to increase effectiveness of therapy can be accomplished through discussion with the patient, physician, and dietitian.

Patients who may need assistance with food and fluid intake are those who have paralysis of the arms, are visually impaired, have an intravenous line in their hand or arm, or are severely impaired or weak (Figure 27-1). You may delegate this task to the nursing assistant or a family member if appropriate (Skill 27-1).

Skill 27-1 Assisting a Patient with Feeding

Assisting a patient with feeding is a nursing responsibility. Patients with physical or mental impairment may require the expertise of a nurse to ensure safe feeding procedure is followed.

Supplies

Supplies

Tray with dishes of food

Tray with dishes of food

Over-the-bed or tray table

Over-the-bed or tray table

Utensils

Utensils

Napkin

Napkin

Straw

Straw

Small towel or extra napkin

Small towel or extra napkin

Review and carry out the Standard Steps in Appendix 3.

Assessment (Data Collection)

Assessment (Data Collection)

1. ACTION Assess the patient’s need for assistance with feeding.

RATIONALE Guides type of assistance to be given.

Planning

Planning

2. ACTION Check the diet on the tray with the diet sheet.

RATIONALE Ensures that the patient receives the correct diet.

3. ACTION Clear the over-the-bed table, and place the diet tray on it. Position the patient in as high a Fowler’s position as is comfortable and permitted. Or assist the patient to a chair. Position the over-the-bed table with the diet tray on it in front of the patient.

RATIONALE Swallowing is enhanced by an upright position.

4. ACTION Protect the patient’s clothing and bed linens with a towel or napkin.

RATIONALE Protects clothing or bed linens from soiling if food is spilled.

Step 3

Step 4

5. ACTION Open the containers of food, fluids, condiments, and eating utensils.

RATIONALE Prepares the food for feeding the patient.

Implementation

Implementation

6. ACTION Ask which foods the patient prefers to begin with. Add condiments as desired by the patient. Alternate foods as the patient desires. Offer small bites, and wait until the patient has chewed and swallowed before offering the next bite.

RATIONALE A relaxed, unhurried manner will encourage the patient to eat more of the meal.

7. ACTION Offer fluids when the patient indicates they are desired. Place a flexible straw in the fluid container and grasp it a few inches from the mouth end when steadying it for the patient to grasp with the lips. Be certain the liquid is not too hot.

Step 7

RATIONALE Liquids help wash down food. Do not add too much liquid as this will interfere with digestion. A straw masks the degree of heat in the fluid, and patients may burn their mouths if the liquid is too hot.

8. ACTION Wipe the mouth at intervals as needed. Talk with the patient during the meal. Try not to appear rushed.

RATIONALE Removal of food particles from the sides of the mouth preserves the patient’s dignity. Conversation adds to the social atmosphere and can improve food intake.

9. ACTION Encourage patients who are physically capable to feed themselves as much as possible.

RATIONALE Self-feeding increases self-esteem.

10. ACTION Refrain from insisting that the patient finish all the meal.

RATIONALE Gentle persuasion to take just another bite is appropriate for the patient who is taking a smaller amount of nutrients than required, but the patient’s wishes must be respected.

11. ACTION When the meal is finished, remove the tray, and offer an opportunity to perform hand hygiene and brush the teeth.

RATIONALE The patient’s hands may have become soiled if the patient participated in feeding. Oral hygiene refreshes the mouth and removes retained food particles.

The Visually Impaired Patient

12. ACTION For the patient who is visually impaired but is able to self-feed, describe what foods are on the plate and tray. Orient the patient to the position of the foods on the plate by describing the plate as if it is a clock face with particular foods positioned at, for example, 12:00, 3:00, 6:00, and 9:00.

RATIONALE Many patients who have their eyes bandaged or who are blind are still able to feed themselves if given adequate orientation to the plate and tray.

13. ACTION Complete procedure as listed for the patient who needs assistance.

RATIONALE Patients with additional impairment may need nursing assistance for feeding.

Evaluation

Evaluation

14. ACTION Assess patient’s tolerance of the meal, the amount consumed, and any difficulty experienced.

RATIONALE Provides information for modification of diet if necessary.

Documentation

Documentation

15. ACTION Document the feeding and the patient’s response.

RATIONALE Documents nutritional intake and how it is tolerated. Communicates progress to the health care team.

Documentation Example

2/16 1200 Fed lunch; ate 50% of meal. Had difficulty chewing and swallowing meats. Occasional coughing when swallowing. Discussed with physician. Diet changed to pureed meats.

____________________

(Nurse’s signature)

? CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

1. The patient requires assistance with feeding, but is reluctant to allow the nurse to help. Identify strategies the nurse might use to make the procedure more acceptable.

2. The patient is recovering from a cerebrovascular accident (CVA). Right-sided weakness is noted on assessment. What safety measures might the nurse use to reduce the risk of complications during assisted feeding?

FIGURE 27-1 Assisting with feeding.

THE POSTOPERATIVE PATIENT

Patients scheduled for surgical procedures may have special dietary needs. Ideally, the surgical patient should be well nourished preoperatively (before surgery) to facilitate postoperative (after surgery) healing and recovery.

Preoperative patients are usually NPO (no food or fluids by mouth) 6 to 8 hours before the procedure. This practice decreases the risk of vomiting whileunder anesthesia, which could lead to aspiration of stomach contents. Aspiration can result in seriousrespiratory complications.

? Think Critically About …

How does the anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract relate to the risk of aspiration when a patient is under anesthesia?

Postoperative patients progress from a clear liquid diet to a full liquid diet. Solid foods are added when the patient can tolerate them without nausea, vomiting, or other abdominal discomfort.

Clear liquids are started when the patient has a return of bowel sounds detected by auscultation. The goal is to introduce fluids that have low residue (remains after digestion), are easily digested, and have low risk of causing abdominal discomfort. Abdominal distress, such as vomiting and distention, can cause injury to surgical incisions.

Foods that are clear fluids at room temperature (e.g., gelatin, Popsicles) and liquids that are clear are on the clear liquid diet. Some physicians will restrict use of cola drinks on a clear liquid diet, but will allow carbonated drinks that are clear, such as white lemon-lime soda or ginger ale. Clear liquid diets are used short term because the diet is deficient in most nutrients. Bouillon (broth) added to the diet adds small amounts of protein and some electrolytes.

The patient progresses to full liquids when clear liquids are tolerated. Full liquid diets include all fluids, custards, ice cream, sherbet, puddings, and strained cereals. Full liquids can be used for long-term dietary management because protein and other essential nutrients, vitamins, and minerals are available from the foods allowed. Foods allowed in clear liquid diets and full liquid diets are compared in Table 27-1.

Table 27-1

Full Liquid and Clear Liquid Diets

Patients recovering from surgical procedures that involved manipulation of or surgical incision into the stomach or bowel may progress to a soft diet before attempting a general or regular diet. Soft diets are low in fiber, and foods have a soft consistency. Foods allowed on a soft diet include eggs, breads without seeds, boiled or mashed potatoes, soups, fruit, juices, tender cooked vegetables, ground or softly cooked meats, cooked cereals, and milk products (see Summary of Basic Hospital Diets in Appendix 5). As the patient’s condition progresses, the diet is advanced to general. This diet has no specific restrictions unless required because of a patient’s specific disease process (see Summary of Basic Hospital Diets in Appendix 5).

? Think Critically About …

Your patient is scheduled for a bowel resection. How would you discuss dietary goals with your preoperative patient? Can you explain expected dietary progression and rationale to your patient?

HEALTH ISSUES RELATED TO NUTRITION

ANOREXIA NERVOSA

Anorexia nervosa is a mental disorder characterized by refusal to maintain a normal minimum body weight, intense fear of becoming obese, and a severe disturbance in body image. It is prevalent among adolescent and young women who become obsessed with being thin; however, adolescent and young men may also be affected. They view themselves as obese despite being extremely underweight. Patients with anorexia nervosa may refuse to eat, or food intake is dangerously low. If not corrected, anorexia nervosa can be fatal. Treatment is a combination of nutritional intervention and psychological counseling (Rader Clinics, 2007).

Collaboration among the patient, family, physician, mental health professional, nurse, and dietitian is crucial. A nutritional plan that is acceptable to the patient should be initiated. The treatment goals are to plan and achieve a nutritious, healthy eating pattern and to attain a body weight that is acceptable to the patient. The patient must have a willingness to remain in psychological therapy and follow nutritional recommendations to achieve treatment success (Communication Cues 27-1).

Communication Cues 27-1

The Patient with Anorexia Nervosa

Terri Mashburn is a 16-year-old high school junior admitted with a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. Terri has lost 30 lbover the past 3 months as a result of refusing to eat and excessive exercise. She is observed during all meals. You are assigned to sit with Terri during her lunch.

NURSE: “Hello, Terri. Your lunch is here. I’m going to sit with you while you eat.”

TERRI: (Moves from chair to bed.) “You can take that away. I can’t eat that stuff! I’m not hungry anyway.” (Curls up in bed; hides face in pillow.)

NURSE: (Places tray on table. Sits on bed next to Terri.) “You seem upset, Terri. Tell me what’s bothering you.” (Places hand on Terri’s shoulder.)

TERRI: “Nothing is bothering me. I just don’t want to eat.”

NURSE: “Tell me about that.”

TERRI: “The nurse weighed me this morning. I’ve gained 2 lb since I’ve been here. This food is making me fat!”

NURSE: “I know you are concerned about your weight. Let’s talk about the medical plan concerning your weight.”

TERRI: (Sits up in bed.) “OK, but you are not going to make me eat all that food.”

NURSE: (Brings tray to beside.) “Tell me which foods you will eat. If you do not like any of them, I can get whatever you want from the dietary department.”

TERRI: (Raises cover on food.) “None of that will do. It will make me fat. I’ll eat a salad and an apple. Sprite to drink will be all right.”

NURSE: “I will call dietary now.” (Calls dietary department to order food.) “Now, let’s review your medical plan while we wait.”

BULIMIA

Bulimia is an eating disorder characterized by episodic binge eating, followed by behaviors designed to prevent weight gain, including purging, fasting, use of laxatives, and excessive exercise. Women with bulimia are aware of their problem and often feel ashamed of the behavior. Treatment of bulimia is usually easier because of this awareness. Psychological as well as nutritional counseling is necessary. Addition of nutritionalsupplements, and monitoring patients after eating to ensure purging does not occur may be included in the treatment plan. Medical conditions such as esophageal and peptic ulcers may accompany bulimia because of the gastric acid exposure during frequently induced vomiting. This condition must be treated along with providing the psychological counseling needed to stop these practices.

Clinical Cues

The patient with an eating disorder requires careful observation and skilled therapeutic communication. You should observe the patient for evidence of “hoarding” food, and structure communication to achieve compliance with the treatment regimen.

Nursing interventions for patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia include diet management, patient teaching, and monitoring progress. Teaching should include principles of healthy weight maintenance, components of a healthy diet, the dangers of fasting and purging, and availability of community support groups. Nurses should document the patient’s weight, compliance with nutritional recommendations, and eating behaviors; the effectiveness of the diet; and need for modification of any aspect of the treatment plan (Bond, 2005).

OBESITY

The incidence of obesity is rapidly increasing in the United States. Research by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control, 2008) estimates that about 62% of Americans are overweight; of those, about 32.5% are obese. Obesity is defined as excessive accumulation of fat, not merely being overweight according to height and weight standards. Many factors contribute to obesity, including genetics, environment, poor eating habits, lack of knowledge about good nutrition, body physiology, age, and gender. Diet therapy to manage obesity must be individualized and incorporate all factors relevant to the patient.

The fact that obesity increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension (abnormally elevated blood pressure), gallbladder disease, and joint disease is well documented. The goal of diet therapy is to improve health and quality of life. Long-term success of weight loss programs is low. Approximately 5% of obese persons who reach their desired weight maintain the weight loss over a 2- to 5-year period. Therefore, reaching a specific weight should not be the only measure of success.

To accomplish weight loss, the individual must expend more energy than is consumed through intake of calories. Exercise designed to match the ability of the patient is usually a component of weight loss programs. Diet therapy is dependent on the patient’s degree of obesity. Obesity is characterized as mild to morbid. A mildly obese person is about 20% to 30% above ideal body weight. Morbidly obese people are at least 100 lb above their ideal body weight. Excessive body fat is present in all instances of obesity. Very-low-calorie diets (500 calories/day or less), appetite suppressants, or surgical intervention may be used to treat obesity. Surgical procedures such as stomach stapling, jaw wiring, and gastric bypass are usually a last resort for individuals who are morbidly obese and have severe medical conditions. Diet therapy to treat obesity should include the following:

• Consultation and continued follow-up with a physician

• Referral and continued follow-up with a dietitian for nutritional assessment and assistance with meal planning

• Development of a meal plan that is realistic and acceptable to the patient

• An exercise program that takes the patient’s interests and physical limitations into consideration

• Foods from all groups of the MyPyramid

• Recommended dietary allowances of all nutrients

Current approaches to treatment of obesity include bariatric surgical procedures. These procedures include gastric bypass and laparoscopic elastic banding (lap band). These procedures have been successful for many individuals who have been unsuccessful at weight loss by other methods; however, there are many potential complications of which the patient must be fully informed (Mayo Clinic, 2007b).

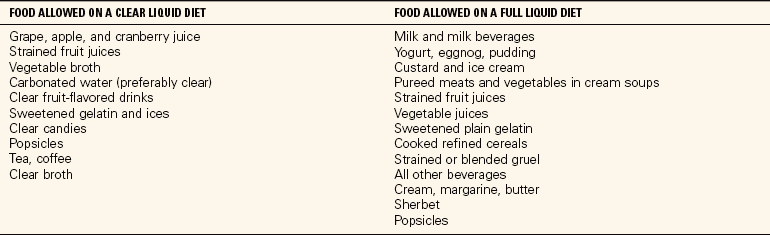

PREGNANCY

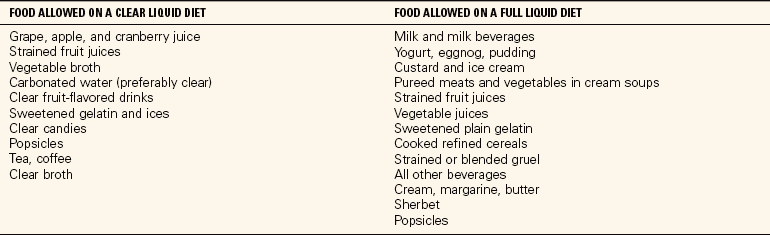

Nutritional status prior to and during pregnancy can influence the health of the mother and the fetus. Nutritional assessment and counseling are important throughout the pregnancy to reduce the risk of complications such as low-birth-weight infants and pregnancy-induced hypertension. Factors to consider when counseling a pregnant woman include her nutritional status prior to pregnancy, her age, and the number of pregnancies. An increase in nutrients is needed for healthy growth of fetal and maternal tissues. Counseling should include emphasis on maternal weight gain. Weight gain during pregnancy should consist of a gain of 2 to 4 lb during the first trimester and 1 lb per week during the second and third trimesters. The recommendation for calorie consumption is no increase during the first trimester and an increase of 300 calories/day during the second and third trimesters. These serve as guidelines only. Factors to consider include the patient’s prepregnancy weight and body mass index (BMI), and the general health of the mother and baby (Mayo Clinic, 2007a). Table 27-2 summarizes dietary needs during pregnancy and lactation.

Table 27-2

Changes in Nutrient Requirements During Pregnancy

Modified from Peckenpaugh, N.J., & Poleman, C. M. (2007). Nutrition Essentials and Diet Therapy (10th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders.

SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Individuals who abuse alcohol and other drugs often present to health care facilities with nutritional deficits. Substance abuse interferes with food intake by decreasing appetite, decreasing the amount of financial resources for food, and substituting calories in alcohol for calories in food. Substance abuse may also lead to impaired absorption and reduced storage and use of nutrients, as well as increased metabolic needs. Thiamine deficiency is often present with alcohol abuse. Patients seen in a health care facility with a history of substance abuse should be assessed for nutritional deficits. Medical treatment will usually include fluid and electrolyte supplements; vitamin and mineral supplements, especially thiamine; and a high-calorie, high-carbohydrate diet. Liver damage is common in substance abuse because of the increased stress of metabolizing excessive alcohol and drugs. Dietary fat may be restricted if liver function is impaired. The nurse plays a vital role in assessment of nutritional status and evaluation of the progress of treatment.

DISEASE PROCESSES THAT BENEFIT FROM DIET THERAPY

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Cardiovascular disease includes diseases of blood vessels, hypertension, myocardial infarction (MI) (loss of blood supply to the heart muscle), and congestive heart failure (CHF) (pump failure of the right or left ventricle). Diet therapy is focused on reduction of fat and sodium intake. Excessive fat intake, especially saturated fat, leads to development of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is the accumulation of fatty deposits on the walls of blood vessels. This process leads to narrowing of the vessel diameter, resulting in decreased blood supply to major organs. Narrow blood vessels increase the workload of the heart, resulting in hypertension as the heart attempts to circulate blood. Dietary management includes reduction of fat intake (30% or less of total calories) and reduction of cholesterol. There are three types of cholesterol in the blood. High-density lipoprotein (HDL) is referred to as “good cholesterol” because high blood levels tend to cleanse vessels of fatty deposits. Elevated blood levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) increase deposits of fat on vessel walls. Very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) serves as a carrier for triglycerides in the blood; therefore, levels should be kept low. Triglycerides are a type of fat that contributes to atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease. Increased levels may also indicate poor management of diseases such as diabetes. Red meats, eggs, and high-fat dairy products contain large amounts of saturated fat. Consumption of low-fat dairy products, vegetable oils, poultry, and fish is desirable to lower cholesterol levels (see Low-Fat Diets in Appendix 5).

Control of sodium in the diet is therapeutic in prevention and management of cardiovascular disease. Large amounts of sodium cause fluid retention. Increased fluid volume in patients with CHF increases the workload of the heart and results in increased respiratory distress and edema in the legs and feet. Increased fluid volume and edema can also lead to hypertension. New research shows that Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)’diets low in sodium and high in fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, legumes, and low-fat dairy products’can lower blood pressure even in healthy people. This might prevent hypertension later in life. The health care provider may prescribe a regular diet with no added salt, or sodium restriction from 250 mg to 4 g. One teaspoon of salt contains 2300 mg of sodium. Sodium content is very concentrated in many foods, and exceeding limits can occur easily. Patients should be taught to read food and beverage labels for sodium content and avoid adding salt to foods during cooking. Salt substitutes and no-salt seasonings may be used in cooking. Patients should consult with the physician or dietitian before using salt substitutes because many contain ingredients that should be avoided by some people (see Sodium-Restricted Diets in Appendix 5).

? Think Critically About …

Are you aware of the amount of sodium you consume? Read the labels for sodium content of your favorite snack foods. Develop an awareness of the amount of salt you add to foods at the table or during meal preparation.

DIABETES MELLITUS

Diabetes mellitus is a disturbance of the metabolism of carbohydrates and the use of glucose by the body. There are two main types of diabetes. Type 1 diabetes (insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus [IDDM]) occurs when the beta cells of the pancreas stop secreting insulin. Insulin is needed to transport glucose across the cell wall. Type 1 diabetes usually develops at an early age and was previously referred to as juvenile diabetes.

Type 2 diabetes (non–insulin-dependent [NIDDM]) occurs when glucose receptors on the cell membrane lose their sensitivity to insulin. Insulin is secreted in normal or excessive amounts; however, the receptor sites will not allow most glucose to enter the cell. Type 2 diabetes usually develops after age 40 and was previously referred to as adult-onset diabetes; however, an increased incidence of type 2 diabetes among young adults has been identified.

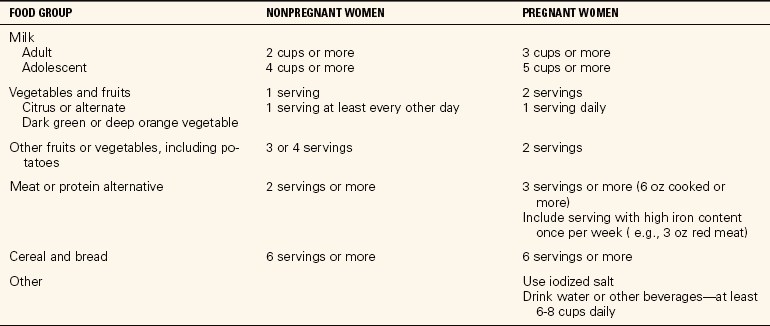

The incidence of diabetes is increasing at an alarming rate in the United States. Of particular concern is the prevalence of type 2 diabetes among late adolescent and young adult individuals. Americans of African American and Hispanic ethnic background are at greatest risk of development of diabetes. The goal of diet therapy for patients with diabetes is to control the amount of carbohydrates in the diet to maintain the blood glucose level at 70 to 100 mg/dL. Generally patients should distribute carbohydrate intake throughout the day and avoid ingestion of large amounts of carbohydrates at one meal. Dietary recommendations are a daily meal plan of 45% to 60% carbohydrates, 20% to 25% protein, and 20% to 25% fat. Calorie restriction will be included if the patient is overweight. Patients with type 2 diabetes are typically overweight. The majority of carbohydrates should be complex (brown rice, pasta, whole-grain foods, legumes). All carbohydrates are converted to glucose for energy. Complex carbohydrates usually contain more nutrients and higher fiber content. Research suggests that fiber delays the absorption of glucose, resulting in lower blood glucose levels. A summary of general dietary strategies for patients with diabetes is provided in Table 27-3.

Table 27-3

Dietary Strategies for the Two Main Types of Diabetes Mellitus

| DIETARY STRATEGY |

TYPE 1 (NONOBESE) |

TYPE 2 (USUALLY OBESE) |

| Decrease energy intake (kilocalories) |

No |

Yes |

| Increase frequency and number of feedings |

Yes |

May be necessary to balance carbohydrate intake |

| Plan consistent daily ratio of protein, carbohydrate, and fat for each feeding |

Desirable |

May be desirable to avoid excessive carbohydrate content in a meal |

| Use extra or planned food to treat or prevent hypoglycemia |

Very important |

Important if patient uses insulin as adjunct to oral medications |

| Plan regular times for meals and snacks |

Very important |

May be important, especially if insulin is used |

| Use extra food for unusual exercise |

Yes |

Usually not necessary; develop strategy based on individual patient need |

| During illness, use small, frequent feedings of carbohydrate to prevent starvation ketoacidosis |

Important |

Usually not necessary because of resistance to ketoacidosis; develop strategy based on individual patient need |

Adapted from Williams, S.R. & Schlenker, E. (2003). Essentials of Nutrition and Diet Therapy (8th ed., p. 385.). St. Louis: Mosby.

Patients with diabetes are at higher risk for cardiovascular disease, hypertension, kidney disease, blindness, and stroke. The nurse should encourage diabetic patients to monitor their blood glucose closely, especially the effect of carbohydrate intake on blood levels, and to consult with and follow the dietary recommendations of a dietitian or nutritionist. The American Diabetes Association recommends a diet of moderate complex carbohydrates, including pasta, beans, whole grains, rice, and fruit. The remainder of the dietary recommendations consists of decreasing the amount of protein to about 25% of total calories, and limiting fat intake to no more than 30% of total calories. Because of the increased incidence of heart disease in diabetic patients, the fat intake should be 20% to 25%. Foods high in saturated fats should be limited or avoided. Patients should be advised to limit the amount of salt added to the diet.

Patients should be instructed in ways to include favorite foods into the diet and remain within their individual dietary plan. The plan should be developed taking into consideration the type of diabetes, the patient’s activity level, and whether or not the patient is overweight. Every diabetic patient responds differently to carbohydrate intake. A serving of carbohydrates is 15 g regardless of the type of food. A patient can monitor his response to particular carbohydrates by measuring the blood glucose 1½ to 2 hours after eating. A blood glucose level of 180 mg/dL or below usually indicates an acceptable level following meals. Patients should be taught to read food labels to determine the amount of carbohydrates in a specific food and include that food in the diet as part of the overall meal plan. A patient may consume simple carbohydrates such as ice cream or candy if they are part of the daily allowance of carbohydrates and not additional. Inclusion of these foods should be dependent on good diabetes control as determined by the health care provider. Dietary counseling related to reducing fat and sodium in the diet should be a part of the meal plan (Nursing Care Plan 27-1).

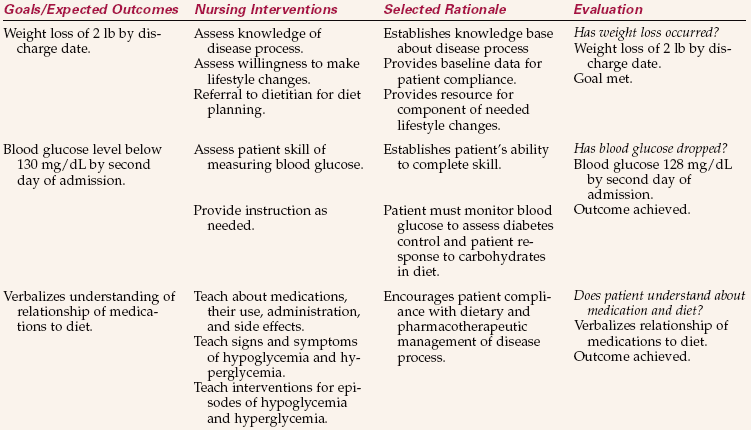

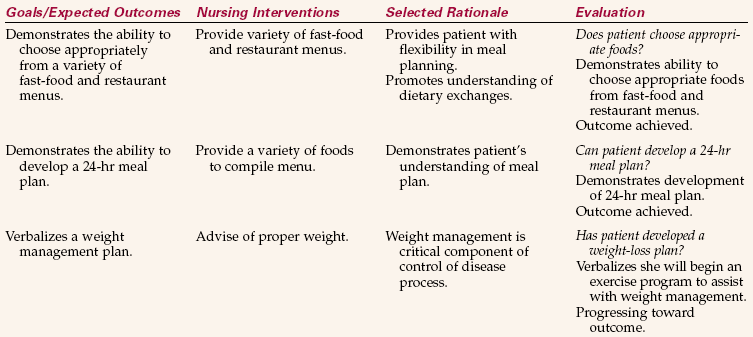

NURSING CARE PLAN 27-1

Diet Therapy for a Patient with Type 2 Diabetes

SCENARIO

Teresa James is a 46-year-old African American diagnosed with type 2 diabetes 3 months prior to admission. T.J. is an attorney in a busy law firm. She states she rarely has time to plan and prepare meals. “I just grab something on the run or eat out.” Mrs. James’ blood glucose is 413 mg/dL on admission. She is 5–3” and weighs 187 lb.

PROBLEM/NURSING DIAGNOSIS

Hyperglycemia (uncontrolled blood sugar)/Noncompliance related to unwillingness/inability to make lifestyle adjustments.

Supporting Assessment Data Subjective: Patient states, “I don’t have time for meal planning and preparation. I just grab something on the go or eat out.” Objective: Blood glucose 413 mg/dL. Weight 187 lb.

PROBLEM/NURSING DIAGNOSIS

Acknowledges inability to make appropriate food choices/Deficient knowledge related to meal planning for diabetes, relationship of diet to management of disease.

Supporting Assessment Data Subjective: Patient states, “I don’t have time for meal planning and preparation. I just grab something on the go or eat out.” Objective: Blood glucose 413 mg/dL. Weight 187 lb.

? CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

1. You are asked to provide a list of dietary recommendations to a patient with diabetes. What will you include in the list?

2. Your patient states he does not understand how to use the American Diabetes Association (ADA) Exchange List. Briefly describe the use of the Exchange List and its implications for the diabetic patient.

? Think Critically About …

Do you have a close family member with diabetes? Genetics play an important role in the development of type 2 diabetes. What steps can you take to prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes?

HIV/AIDS

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) and AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) are associated with severe diarrhea, profound weight loss, and muscle wasting. Some patients lose as much as 50% of their body weight as a result of treatment, multiple infections, loss of appetite, malignancies, and gastrointestinal disorders. Diet therapy is directed toward replacement of fluids and electrolytes, weight gain, replacement of muscle mass through protein intake, and maintaining the strength of the immune system. Patients should be referred to the dietitian as soon as they are diagnosed as HIV positive. Developing good nutritional practices is important in maintaining function of the immune system. Research suggests that diet therapy can be a factor in delaying the onset of full-blown AIDS.

Calorie intake should be increased for patients with HIV/AIDS. Emphasis should be placed on protein intake. Infections, an impaired immune system, and medical treatment may result in painful lesions in the mouth and ulcerations in the esophagus and stomach. Solid food may be difficult to eat. Milkshakes with added calories and supplements such as Ensure or Sustacal can be used to provide calories and protein. Fluids and electrolytes may be replaced intravenously (see High-Calorie/Protein Diets in Appendix 5). Dietary considerations include the following:

• Maintaining high calorie intake

• Increasing protein intake to maintain or increase muscle mass

• Offering bland, soft, or pureed foods when the mouth is painful

• Adding thickening agents to liquids if swallowing is difficult

• Adding seasonings to help food taste more appealing

• Encouraging small, frequent meals

Complete assessment of health and nutritional status is important for patients diagnosed with HIV/AIDS. Typical nursing diagnoses for HIV/AIDS patients are as follows:

• Impaired oral mucous membrane related to impaired immune system

• Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements related to anorexia, and/or oral lesions

• Fluid volume deficit related to prolonged diarrhea and decreased fluid intake

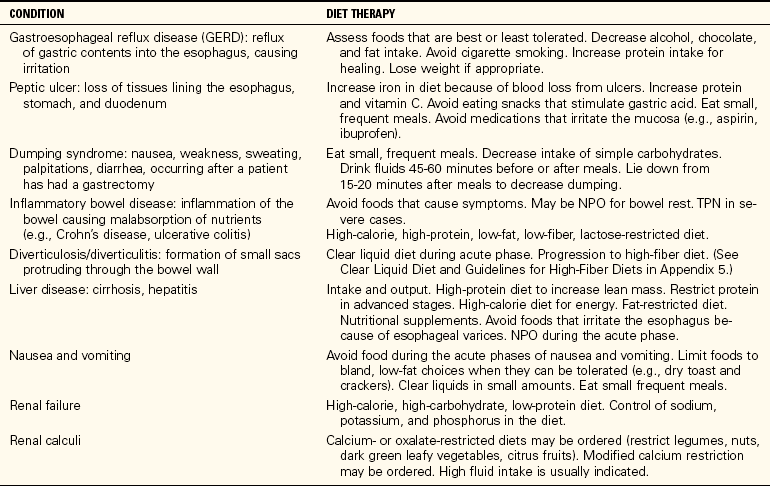

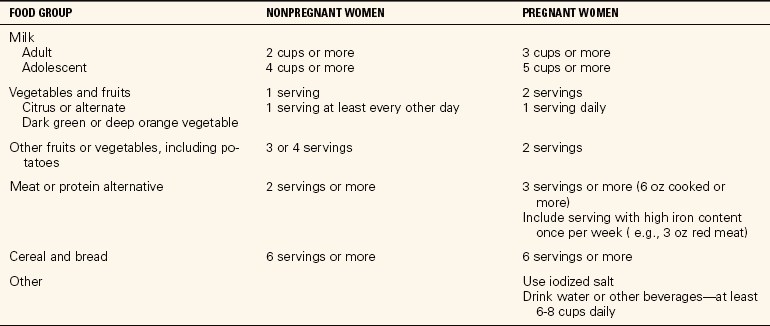

Table 27-4 provides a summary of nutritional recommendations for diseases/disorders of various body systems.

Table 27-4

Diet Therapy for Specific Diseases and Disorders

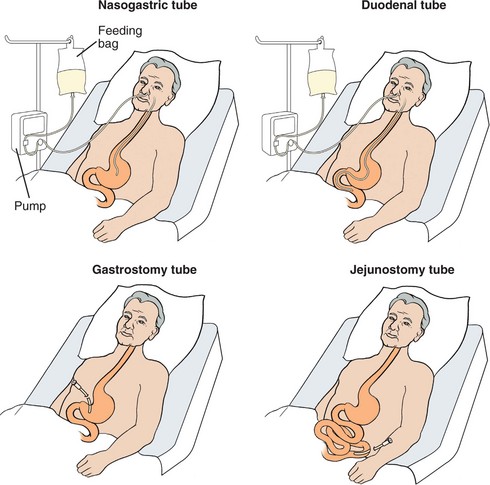

ASSISTED FEEDING

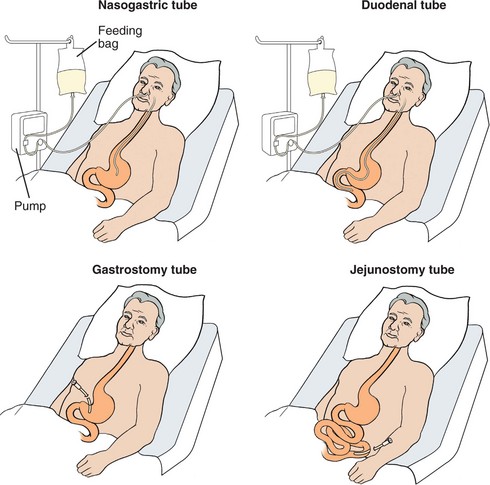

Patients with acute illness and neurologic disorders may be unable to tolerate oral fluid intake. Patients may experience dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) following a stroke or develop an increased risk for malnutrition from the effects of inflammatory bowel disease, HIV/AIDS, and cancer treatment. There are several types of enteral tubes. Tubes may be placed through the nose into the stomach (nasogastric tubes), placed directly into the stomach (gastrostomy tubes or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy [PEG] tubes), or placed into the intestine (jejunostomy or duodenal tubes) (Figure 27-2).

FIGURE 27-2 Anatomic locations for nasogastric, duodenal, gastrostomy, and jejunostomy tubes.

NASOGASTRIC AND ENTERAL TUBES

Nasogastric (NG) tube placement is usually a temporary measure to provide nutritional support. The tube is placed through the nose and esophagus into the stomach. The nasogastric tube may be used for other purposes, such as the following (Figure 27-3):

FIGURE 27-3 Nasogastric and enteral feeding tubes.

• Decompression of the stomach, such as removing stomach contents prior to or after surgery

• Obtaining specimen for lab analysis

• Gastric lavage for patients with gastrointestinal bleeding or for removal of ingested toxins

• Administration of medications (see Chapter 34, Skill 34-4)

Skill 27-4 Administering a Nasogastric/Duodenal Tube Feeding or Feeding via a PEG Tube

Tube feedings are administered to patients who cannot ingest food orally but do not have a problem with absorption of nutrients from the intestinal tract. They may be used for short-term or long-term nutritional support. Intermittent feedings should only be used with stomach tubes.

Supplies

Supplies

Large syringe or feeding bag and feeding formula

Large syringe or feeding bag and feeding formula

Tubing

Tubing

Feeding pump (if needed)

Feeding pump (if needed)

Stethoscope

Stethoscope

Gloves

Gloves

Adaptor for syringe for small-bore tubes

Adaptor for syringe for small-bore tubes

Glass of water

Glass of water

Review and carry out the Standard Steps in Appendix 3.

Assessment (Data Collection)

Assessment (Data Collection)

1. ACTION Check the physician’s order for type of feeding, amount, and strength of solution.

RATIONALE Ensures feeding is given according to physician’s order.

2. ACTION Assess abdomen for distention or tenderness.

RATIONALE Identifies discomfort prior to feeding to avoid complication.

Planning

Planning

3. ACTION Elevate the head of the bed 30 degrees.

RATIONALE Elevation allows gravity to help flow of the formula into the stomach and thus helps prevent reflux. The position should be maintained at least 30 to 60 minutes after the feeding.

4. ACTION Perform hand hygiene. Put on gloves.

RATIONALE Possible contact with body fluids requires the use of gloves.

Implementation

Implementation

5. ACTION Pinch off the tube and remove the plug, cap, or clamp.

RATIONALE Pinching the tube prevents fluid leaking from the tube.

6. ACTION Check placement of the tube. For NG tube, attach syringe and aspirate small amount of stomach contents (5 to 10 mL); if no fluid is obtained, check the tube placement by introducing air through the tube and listening to the left of the xiphoid process with the stethoscope for a “swoosh”; for a small-bore feeding tube, verify that placement has been checked by x-ray. Reinstill aspirated fluid.

RATIONALE Obtaining gastric or intestinal contents is the best evidence of proper tube placement. Small-bore feeding tubes frequently will collapse when aspiration is attempted and nothing can be obtained. Stomach or intestinal contents are high in electrolytes, and removal depletes electrolytes. When more than 150 mL of residual formula are obtained, the physician should be notified because it is an indication that the feeding is not well tolerated.

For Intermittent Feedings

7. ACTION Pinch off the tube and pour the formula into a gavage bag or the barrel of the syringe, keeping it no more than 18 inches above the level of entry into the stomach or intestine. If a gavage bag is used, fill it with the prescribed amount of formula and regulate it to run in slowly over 30 minutes.

Step 7

RATIONALE The formula should be given over 10 minutes or longer; gravity pull will draw it in. Flow can be regulated by raising and lowering the container.

8. ACTION Add formula to keep the neck of the syringe filled. Continue adding formula to the syringe until the prescribed amount is given. Flush the tube with 30 to 60 mL of water.

RATIONALE If the formula level falls below the neck of the syringe, air will enter the tubing and the intestinal tract, causing discomfort as a result of distention. Flushing the tube helps to prevent clogging.

For Continuous Tube Feeding

9. ACTION Fill the feeding bag with the prescribed amount of formula, clear the tubing of air, and attach it to an intravenous pole or infusion pump. Set the rate according to the physician order.

Step 9

RATIONALE Feeding bag can be hung at room temperature for 4 hours within the hospital environment. A feeding pump delivers a controlled flow of formula. Some gavage bags have a pocket in which to place ice; this type of bag can allow the formula to hang up to 6 hours when ice is present.

10. ACTION Verify enteral, gastrostomy, or jejunostomy tube placement.

RATIONALE Jejunostomy tube sutures must be secure. Aspirating usually will not produce fluid from the jejunum; air cannot be easily detected when instilled into the jejunum. If the tube is not in place, the feeding could spill into the abdominal cavity, causing a chemical peritonitis.

11. ACTION Check the amount of residual from the previous feeding for gastrostomy tube by aspirating with a syringe; reinstill the fluid.

RATIONALE Residual should be checked every 4 hours for continuous gastrostomy tube feedings.

12. ACTION Attach the tubing from the feeding bag to the enteral, gastrostomy, or jejunostomy tube using an adaptor as needed. Turn on the pump and check the drip rate; begin feeding.

RATIONALE Drip rate should be checked frequently. Patient tolerance of the feeding should be assessed every hour while the patient is awake. Increasing abdominal distention or pain indicates a problem.

13. ACTION Follow the formula with 1 to 2 oz of water to clear the tube. Keep the liquid level above the neck of the syringe or bag to prevent air bubbles from collecting in the system or in the patient’s intestinal tract.

RATIONALE Water helps clear the tubing and prevents clogging.

For Both Intermittent and Continuous Tube Feeding

14. ACTION Remove the syringe or connecting tubing, and clamp the tube by inserting the plug and covering with a cap protector or with a gauze 2 × 2 secured with a rubber band; a clamp may also be used (for intermittent feedings).

RATIONALE This prevents backflow of the formula or stomach fluid.

15. ACTION In the home, wash the bag and tubingor other equipment with soap and water every8 hours; change the bag and tubing or syringeevery 24 hours.

RATIONALE In home setting, equipment is washed with soap and water every 8 hours but may be reused for 3 to 7 days. Equipment is rinsed thoroughly after each feeding in the hospital and in the home.

16. ACTION Remove gloves and perform hand hygiene.

RATIONALE Prevents spread of microorganisms.

Evaluation

Evaluation

17. ACTION Assess patient for evidence of discomfort or complications such as nausea, vomiting, and respiratory distress.

RATIONALE Provides evidence of patient’s tolerance of tube feedings.

18. ACTION Monitor lab values, weight daily.

RATIONALE Assesses evidence of resolution of malnutrition.

Documentation

Documentation

19. ACTION Documentation should contain type of formula given, amount, verification of tube placement or securing sutures, amount of residual if obtained, and any signs of intolerance of the feeding.

RATIONALE Documents nutritional intake and any problems.

Documentation Example

5/16 1300 240 mL Jevity given via PEG tube. Checked for residual prior to feeding. 25 mL gastric contents aspirated and reinstilled. Abdomen soft, bowel sounds present in all quadrants. Tolerated feeding without evidence of discomfort. Head of bed remains at 30 degrees.

____________________

(Nurse’s signature)

Home Care Considerations

Nursing support for patient and family is essential. Teaching should involve patient and family if possible. Teaching plan should include

• Type of feeding

• Amount of feeding

• Operation of the feeding pump if used

• Checking for tube placement

• Signs and symptoms of complications

• Positioning the patient

• Procedure for manual feeding

• Safety factors during feeding

• Signs of problems to report

? CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

1. The patient is receiving continuous tube feeding at 70 mL/hr. The nurse checks residual and returns 500 mL. What action(s) should the nurse take?

2. The caregiver reports to the home care nurse that the patient has been coughing and “milk-like” drainage has been noted around the patient’s nose. List appropriate nursing interventions.

When enteral nutrition is anticipated over an extended period of time, small-bore feeding tubes (8 to 10 Fr.) may be inserted. Small-bore tubes are soft, flexible tubes that must be inserted by a skilled person using a guidewire or stylet. Patients who are active may find the tube restrictive and inconvenient. Nursing care of patients with NG tubes involves insertion, irrigation, administration of tube feeding, checking for placement, and removal of the tube.

Success in inserting the tube is more likely if the confidence of the patient is gained first. Tube insertion is more difficult if the patient is unable to cooperate, such as unconscious patients or patients with impaired mental function (Skill 27-2). Explain the procedure and its benefit to the patient prior to beginning insertion. Proper placement of small-bore tubes should be verified by x-ray.

Skill 27-2 Inserting a Nasogastric Tube

A nasogastric (NG) tube is inserted per a physician’s order and is used with suction when a patient is experiencing excessive vomiting, needs stomach decompression after surgery on the intestinal tract, or is at risk for aspirating stomach contents because of decreased level of consciousness. If the patient needs enteral feedings, the tube is either attached to a feeding pump or left unattached and plugged off for intermittent feedings.

Supplies

Supplies

Stethoscope

Stethoscope

Gloves

Gloves

Drape or towel

Drape or towel

Tongue blade

Tongue blade

NG tube

NG tube

Flashlight

Flashlight

Glass of water, straw

Glass of water, straw

Tape

Tape

Water-soluble lubricant

Water-soluble lubricant

Plug for tube

Plug for tube

Irrigation syringe and solution container

Irrigation syringe and solution container

Safety pin

Safety pin

Tissues

Tissues

Normal saline solution

Normal saline solution

Suction machine and connecting tubing, or feeding pump and tubing

Suction machine and connecting tubing, or feeding pump and tubing

Review and carry out Standard Steps in Appendix 3.

Assessment (Data Collection)

Assessment (Data Collection)

1. ACTION Assess the patient’s understanding of the procedure.

RATIONALE Patients can be more cooperative when they understand what is happening to them.

Planning

Planning

2. ACTION Check the airflow through the nostrils: Close one side of the nose, and check the airflow through the other.

RATIONALE This procedure determines which nostril is most patent and should be used for the tube’s passageway.

3. ACTION Gather all equipment needed. Position the patient with the head of the bed elevated 30 to 90 degrees. Raise head of bed to working height.

RATIONALE Demonstrates good time management. Elevating the head of the bed enables the tube to move by gravity down the digestive tract.

4. ACTION Hand the emesis basin and the tissues to the patient. Otherwise, place the emesis basin close beside the patient’s face with the tissues near the pillow. Agree on a hand signal that will instruct you to stop if the patient experiences too much discomfort.

RATIONALE The basin will catch emesis if the patient vomits. The signal allows the patient some control of the procedure.

5. ACTION Put on gloves.

RATIONALE Barrier protection is needed in case the patient vomits or there is spillage of gastric contents.

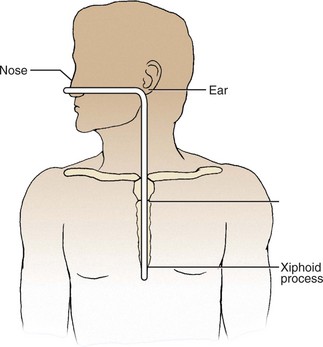

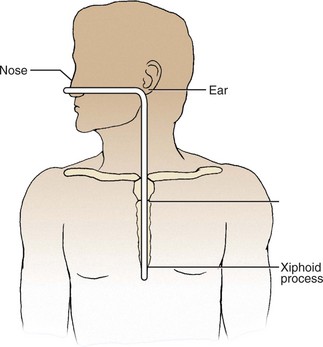

6. ACTION Measure the distance the tube is to be inserted by measuring from the tip of the nose to the tip of the ear and then to the xiphoid process. Mark it with a piece of tape.

Step 6

RATIONALE Some tubes have approximate target markings on them: one black band indicating the length of the tubing needed to reach the stomach, two bands for the pylorus, and three bands for the duodenum. Marking the tube after measurement individualizes the tube length.

7. ACTION Chill or warm the tube to the desired stiffness for insertion.

RATIONALE A too limp or too stiff tube is difficult to insert. Placing a soft rubber tube in a basin of ice will stiffen it; placing a stiff plastic tube in a basin of warm water will soften it.

Implementation

Implementation

8. ACTION Lubricate the tip of the tube and insert it through the nostril with the best airflow. If changing the NG tube, insert it in the nostril other than the one previously used to avoid further irritation of the tissue. With the patient’s head hyperextended, aim the tube down and toward the ear. Twist the tube slightly as you advance it. If you encounter severe resistance, withdraw the tube and insert it in the other nostril. Do not forcibly push it because you could injure tissue and cause bleeding.

RATIONALE Using the largest passageway for insertion of the tube decreases tissue trauma. For easier insertion, use water or a water-based lubricant to moisten the tip of the tube. Do not use an oil-based lubricant because of the possibility of lipid aspiration.

9. ACTION As the tube reaches the back of the throat, have the patient take sips of water through the straw, drop the head forward, and begin to swallow.

RATIONALE Encouragement is offered by saying “swallow,” “swallow,” when advancing the tube.

10. ACTION Check the position of the tube as it passes down the back of the patient’s throat by having the patient open his mouth and hold down the tongue with a tongue depressor. If the tube is coiled up in the mouth, withdraw it into the nose and begin again by having the patient bend head forward and swallow. The patient can signal you to stop for a moment to rest, if necessary, but avoid waiting too long.

RATIONALE Difficulty with the tube entering the esophagus opening sometimes occurs.

11. ACTION Advance the tube each time the patient swallows.

RATIONALE The tube advances more easily with the assistance of esophageal peristalsis.

12. ACTION Check the placement of the tube:

A Use the irrigating syringe to pull back, using gentle suction, and aspirate stomach contents. If none are obtained, turn the patient onto the left side and insert the tube another 1 to 2 inches. Test the fluid pH; instill 30 mL of air and obtain a sample of fluid. Fluid can be tested using pH strips.

B When tube placement has been properly established and the tube is secured to the patient, thereafter some facilities will allow checking by injecting 10 to 20 mL of air into the tube with the irrigating syringe and listening with the stethoscope placed to the left of the tip of the xiphoid. The air makes a “swooshing” sound as it enters the stomach, but the patient may belch if the tube is in the esophagus. However, this is not recommended as “best practice.”

RATIONALE When the target point on the tube has reached the nose, the tube should be in the stomach; this must be verified with a pH check of the aspirated fluid. Gastric pH is 1 to 4, intestinal and respiratory pH is greater than 6. A pH greater than 6 indicates the tube is in the trachea. If there is a question about placement, contact the physician.

13. ACTION Tape the tube securely to the face. Clean the bridge of the nose with a prep pad or apply tincture of benzoin to it. Cut a 4-inch long piece of 1-inch tape; split it up the middle for 3 inches. Place the solid piece of tape on the bridge of the nose, and spiral the split ends down the tube. Secure the tape with one more piece across the bridge of the nose. Be certain the tube is not rubbing the side of the naris because it can cause necrosis.

Step 13

RATIONALE The tube must be secured so that it is not easily dislodged. Commercially made NG tube holders are available and may be used in your facility.

14. ACTION Attach the free end of the tube to the connecting tubing attached to the suction machine or feeding tube. Turn the suction machine or wall unit to low intermittent suction for a patient who needs stomach decompression. If using a feeding pump, adjust the drip rate to the rate prescribed by the physician, connect the tubing, and turn on the pump. When the patient is up and not attached to the suction machine or feeding pump, loosely loop the tube in a circle, secure the loop with adhesive tape, and pin the tube to the gown.

RATIONALE Low, intermittent suction is usually ordered to prevent damage to the stomach mucosa. Securing the tube to the gown helps prevent pulling the tube, which is uncomfortable for the patient and can dislodge the tube.

15. ACTION Remove gloves. Position the tube by looping it above the stomach level, placing a piece of tape around it to make a tab, and fastening the tab to the gown with a safety pin.

RATIONALE Prevents the tube from becoming dislodged.

16. ACTION Perform hand hygiene before leaving the room.

RATIONALE Hand hygiene is necessary even after wearing gloves to prevent transmission of organisms to others.

Evaluation

Evaluation

17. ACTION For patient who needs stomach decompression, ask the patient if nausea is relieved. Assess abdomen for distention. Note the flow of stomach contents into the suction canister.

RATIONALE Determines effectiveness of procedure.

18. ACTION If feeding tube is inserted and feeding started, assess residual stomach contents in 4 hours. If patient is able to communicate, ask if there is any abdominal discomfort.

RATIONALE Evaluates patient’s tolerance of tube feeding.

Documentation

Documentation

19. ACTION Document procedure on the nurse’s notes. Document intake on the intake and output record. Documentation should include

• Reason for tube insertion

• Time of procedure

• Type of procedure

• Type and size of tube

• Patient’s tolerance of procedure

• Amount and characteristics of stomach contents

RATIONALE Provides members of the health care team with description of the procedure and the patient’s response.

Documentation Example

2/13 1300 Number 16 Levin tube inserted in right nostril. 500 mL dark green fluid returned. Vomited 200 mL dark green fluid during tube insertion. Tube taped to nose. States nausea and abdominal pain relieved after tube insertion. Tube connected to low, intermittent suction.

____________________

(Nurse’s signature)

Special Considerations

Special Considerations

Insertion of NG tube in patients who are unconscious or have endotracheal tubes in place may require assistance. Seek the help of another nurse to ensure patient safety.

Insertion of NG tube in patients who are unconscious or have endotracheal tubes in place may require assistance. Seek the help of another nurse to ensure patient safety.

Consult with the physician before inserting an NG tube into the nostril of a patient who has had nasal or throat surgery or trauma to the nose. Special care is usually required.

Consult with the physician before inserting an NG tube into the nostril of a patient who has had nasal or throat surgery or trauma to the nose. Special care is usually required.

Patients with mental impairment may attempt to pull out the feeding tube. Protective mittens may be applied to prevent pulling out the tube.

Patients with mental impairment may attempt to pull out the feeding tube. Protective mittens may be applied to prevent pulling out the tube.

Keeping the suction connecting tubing above the entrance to a portable suction unit helps the suction to work more efficiently.

Keeping the suction connecting tubing above the entrance to a portable suction unit helps the suction to work more efficiently.

? CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

1. The nurse inserts a nasogastric tube and checks for placement. When 20 mL of air is instilled, the nurse hears a “swoosh” over the stomach. The nurse aspirates 10 mL of fluid from the tube. The pH strip test 7.0. What action should the nurse take?

2. The patient has a nasogastric tube inserted postoperatively. The nurse notes that there has been no drainage from the tube in the past hour. List appropriate nursing actions.

Nasogastric tubes should be monitored frequently. Check tube placement prior to feeding or administering medications. Patients with decreased level of consciousness and decreased cough or gag reflex may not exhibit expected symptoms if the tube is displaced into the respiratory tract. Placement of the tube in the respiratory tract can lead to severe respiratory complications if the tube enters the pleural space or if misplacement is not detected prior to feeding or medication administration.

The nasogastric tube is irrigated to ensure it is patent. Usually 30 to 60 mL of normal saline solution is sufficient to flush the tube. The amount used for irrigation must be counted as part of the recorded intake (Steps 27-1). When therapy is completed or the patient is able to tolerate oral feedings, the nasogastric tube can be removed (Steps 27-2).

Steps 27-1 Nasogastric Tube Irrigation

Nasogastric tubes are irrigated to verify patency and keep them from clogging. They may be irrigated every few hours or once a day depending on the situation and the physician’s orders.

Review and carry out the Standard Steps in Appendix 3.

1. ACTION Check physician’s order for frequency of irrigation, and amount and type of solution.

RATIONALE Ensures following procedure as ordered.

2. ACTION Assess the color, amount, and characteristics of gastric secretions.

RATIONALE Provides baseline information.

3. ACTION Assess bowel sounds.

RATIONALE Bowel sounds are evidence of return or improvement of bowel function.

4. ACTION Assess patient for complaints of discomfort.

RATIONALE Information may indicate potential complications.

5. ACTION Position the patient in semi-Fowler’s position at 30 to 60 degrees.

RATIONALE A slightly upright position helps prevent reflux.

6. ACTION Perform hand hygiene and put on gloves.

RATIONALE Possible contact with body fluids requires the use of gloves.

7. ACTION Verify proper placement of the tube.

RATIONALE Prevents instilling irrigation fluid into the lungs.

8. ACTION Fill the syringe with the irrigating solution, usually normal saline, by holding the syringe between your index finger and thumb. Place the tip of the syringe in the solution, and pull the plunger up to obtain at least 30 mL of solution.

RATIONALE Normal saline is isotonic and will not upset electrolyte balance. Cola has shown to be an effective irrigation solution following tube feedings.

9. ACTION Disconnect the gastric tube from the suction tubing on the machine; hold the connecting tubing between the last two fingers of your nondominant hand; hold the gastric tube in a fistlike grasp with the other fingers of that hand.

RATIONALE The tube may be irrigated only if disconnected from suction.

10. ACTION Attach the filled syringe to the free end of the gastric tube and instill the solution.

RATIONALE Assists in clearing the tube.

11. ACTION When irrigation is completed, attach the gastric tube to the suction tubing; restart the suction.

RATIONALE Checking that the suction machine or unit is turned on will ensure correct function.

12. ACTION Remove gloves and perform hand hygiene; make the patient comfortable.

RATIONALE Performing hand hygiene prevents spread of microorganisms.

13. ACTION Add amount of irrigating solution to intake record.

RATIONALE Documents intake.

Steps 27-2 Nasogastric Tube Removal

When the condition for which the NG tube was inserted has resolved, the tube is discontinued.

Review and carry out the Standard Steps in Appendix 3.

1. ACTION Check physician’s order sheet for order to remove NG tube.

RATIONALE Prevents removal of the tube while still needed.

2. ACTION Assess amount, color, and character of drainage in suction canister.

RATIONALE Amount, color, and character of drainage must be documented on the chart.

3. ACTION Explain procedure to patient.

RATIONALE Helps gain patient’s confidence and cooperation.

4. ACTION Elevate head of bed to 30 degrees.

RATIONALE Position is more comfortable for patient.

5. ACTION Perform hand hygiene and put on gloves.

RATIONALE Protection against exposure to body fluids.

6. ACTION Turn off suction or tube feeding pump if present. Place the towel or basin where the withdrawn tube can be placed into it quickly. Flush the tube with 20 mL of water followed by 20 mL of air. Pinch off the tube and pull out gently but quickly.

RATIONALE Flushing the tube clears gastric content from the tube that may leak into the esophagus and cause irritation. Instillation of air pushes tube away from stomach lining and reduces the risk of trauma during removal. Pinching off the tube prevents spillage of any residual fluid.

7. ACTION Offer mouth care.

RATIONALE Mouth care removes unpleasant taste from the mouth.

8. ACTION Measure and record the gastric drainage. Rinse or dispose of the drainage container and tube following facility policy.

RATIONALE Gastric drainage is recorded as part of output for the shift.

9. ACTION Remove gloves and perform hand hygiene.

RATIONALE Prevents spread of microorganisms.

10. ACTION Assess every 2 hours for signs of nausea, vomiting, or abdominal distention. Assess bowel sounds.

RATIONALE Provides for early recognition of intolerance to removal of NG tube.

11. ACTION Document the time the tube was removed and the patient’s response to the procedure. If the tube was used for suction, record amount and characteristics of drainage.

RATIONALE Documentation provides communication to other health care personnel concerning the care provided to the patient.

PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC GASTROSTOMY TUBES

A PEG tube is generally used when a patient requires long-term nutritional support. The PEG tube has replaced surgical gastrostomy tube placement in most situations. The PEG tube has several advantages over surgical gastrostomy, including reduced procedure time, cost, and recovery time, and no need for general anesthesia. The tube is placed via endoscopy either in the day surgery unit or gastrointestinal (GI) lab. The PEG tube allows patients more freedom of ambulation and allows the patient the opportunity to administer his own feeding easily. A PEG tube can be removed easily when it is no longer indicated.

Care of the PEG tube is similar to that of the NG tube. Tube placement should be checked at least every shift and prior to feeding or administration of medication. Check the patient’s chart for the placement measurements. Measure the tube length from skin level to the end of the placement adapter. Compare the measurements. Higher measurements indicate the tube has migrated outward. If the tube becomes dislodged, the nurse should notify the charge nurse and the physician. Follow the facility policy and licensure regulations regarding reinsertion of the tube. The tube may be reinserted by an LPN/LVN if permitted by the scope of practice. Document your findings and report them to the physician if discrepancies are present.

Daily care of the tube involves washing the tube insertion site with soap and water. Use a cotton swab moistened with saline or half-strength peroxide to remove encrustation. Assess the skin for evidence of irritation, maceration, or signs of infection. Dry the site and reposition the external disk to prevent sticking to the skin. Document your assessment and treatment of the site. Observe the patient for abdominal distention or aspiration. Abdominal pain, vomiting, or respiratory distress may be signs of complication. Prior to feeding or administration of medications, the amount of residual fluid in the stomach should be assessed. If a continuous feeding is in progress, stop the infusion prior to checking for residual. Use an irrigation syringe to withdraw stomach contents. If the residual volume is greater than 150 mL, replace the withdrawn fluids and delay further feeding for 1 to 2 hours. (Facility policies vary. Follow the policy in your facility of practice.) Keep the patient’s bed elevated at least 30 degrees at all times if the patient is on continuous feeding to facilitate stomach emptying and prevent aspiration. Further discussion of various tubes for medical conditions can be found in your medical-surgical textbook.

FEEDING TUBES AND PUMPS

Tube feedings can be continuous or intermittent. Continuous feeding is effective for patients who cannot tolerate large amounts of fluids at one time. Intermittent feeding is beneficial for patients who are able to feed themselves or when beginning to reintroduce oral feeding. Intermittent feeding more closely resembles regular meals. Feelings of hunger stimulate appetite and aid in the transition from tube to oral feeding.

The amount of tube feeding is prescribed by the physician and usually ranges from 8 to 12 oz per feeding. It may be necessary to start with smaller amounts and increase the feeding as the patient is able to tolerate the formula. A daily amount of 2000 mL is generally sufficient to meet the patient’s nutritional requirements. High concentrations of carbohydrates are needed to increase the caloric content of the formula above this amount, but this often leads to diarrhea. If a syringe is used, it should be 30 mL or larger, and the formula should flow in by gravity; it should not be pushed in as a bolus or in large amounts. Allow about 10 minutes for an intermittent feeding to flow into the tube. Flush the tube with 30 mL of water after each feeding to prevent clogging. Facility policy may include use of carbonated sodas such as cola or ginger ale to flush tubing.

Continuous feedings are instilled into the tube drop by drop in much the same manner as an intravenous feeding. For this purpose, a feeding pump and a tube feeding set similar to an intravenous administration set is used (Skill 27-3). The rate is set on the pump, or the drops are regulated through the drip chamber to control the amount given; this device can be used with NG tubes, PEG tubes, or jejunostomy tubes (Skill 27-4). Tube feedings contain a high level of glucose to provide the necessary calories. They should be given slowly to prevent diarrhea and glycosuria (sugar in the urine). The preferred method is to give the feedings slowly over a 24-hour period. When feedings are ordered for four or more times a day, the patient is usually given 150 to 240 mL per feeding and advanced at a rate of 50 mL/day until the desired volume is tolerated. Principles to observe when administering tube feedings are summarized in Box 27-1.

Skill 27-3 Using a Feeding Pump

Continuous feeding via feeding pump is usually prescribed when a patient requires long-term nutritional support or cannot tolerate large volumes of feeding formula at one time.

Supplies

Supplies

Feeding formula

Feeding formula

Irrigating syringe

Irrigating syringe

Feeding pump

Feeding pump

Stethoscope

Stethoscope

Tubing for pump

Tubing for pump

Gloves

Gloves

Feeding tube bag

Feeding tube bag

Glass of water

Glass of water

Review and carry out Standard Steps in Appendix 3.

Assessment (Data Collection)

Assessment (Data Collection)

1. ACTION Check the physician’s order for type, amount, and flow rate of feeding.

RATIONALE Ensures correct feeding formula is administered.

2. ACTION Put on gloves. Assess tube placement or residual if PEG tube is in place.

RATIONALE Possibility of coming in contact with body fluids requires wearing gloves. Assessing placement determines NG tube is in the stomach, and prevents infusion of feeding into respiratory tract. Check residual to determine if stomach is emptying effectively.

Planning

Planning

3. ACTION Elevate head of bed at least 30 degrees. Keep bed elevated at all times.

RATIONALE Assists in preventing gastric reflux and/or aspiration of feeding.

4. ACTION Open tubing and feeding bag and connect to feeding pump with tubing clamp closed. Open formula and pour enough to infuse over a 4- to 6-hour period. If using commercially prepared feeding container, close the roller clamp on the tubing, spike the infusion port and fill the drip chamber.

RATIONALE Small amount of feeding formula in bag prevents spoilage of formula. Some formulas are prepared in an administration container. These formulas are prepared to hang for up to 24 hours.

5. ACTION Open the clamp and prime the tubing by allowing the formula to fill the length of the tubing.

RATIONALE Prevents air from entering the stomach and causing abdominal distention and discomfort.

Implementation

Implementation

6. ACTION Attach the tubing to the NG tube or PEG tube. Set the flow rate and turn on the pump.

RATIONALE Begins administration of feeding formula.

7. ACTION Observe the infusion for 2 to 3 minutes before leaving patient.

RATIONALE Determines if formula is infusing properly.

8. ACTION Remove gloves and perform hand hygiene.

RATIONALE Prevents spread of microorganisms.

Evaluation

Evaluation

9. ACTION Assess patient for signs of complications, including abdominal distention, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

RATIONALE Determines patient’s tolerance of tube feeding.

10. ACTION Assess stomach residual every 4 hours by aspirating contents.

RATIONALE Determines if stomach is emptying properly.

Documentation

Documentation

11. ACTION Document the time the infusion was started, type of formula, amount, and flow rate. Include checking for tube placement or check for residual. Document patient’s response to the infusion.

RATIONALE Verifies nutritional intake and patient response.

Documentation Example

2/14 1000 Feeding via pump initiated with 200 mL formula at 50 mL/hr. Tube patent and in place with return of gastric secretions. Positioned ↑ 30 degrees. Bowel sounds present all 4 quads.

____________________

(Nurse’s signature)

? CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

1. The nurse discovers the feeding solution bag empty and the pump continuing to infuse. Identify nursing interventions.

2. The home care nurse discovers the patient resting on the left side with the head on a pillow and the head of the bed flat. A continuous tube feeding is infusing at 30 mL/hr. What action, if any, should the nurse take?

Box 27-1 Principles of Tube Feeding

Principles to follow when giving patients tube feedings:

• Elevate the head of the bed 30 to 90 degrees before feeding and leave it up for 30 to 60 minutes after the feeding.

• Keep the head of the bed elevated at least 30 degrees at all times if the patient is receiving continuous feeding.

• Assess bowel sounds at least once every 8 hours.

• Assess abdomen for distention.

• Check the tube position within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract before each feeding is started or at least once each shift.

• Check for gastric residual by aspirating via the gastric tube before each intermittent feeding or at least every 4 hours if the patient is receiving continuous feeding. If the gastric residual is greater than one half the volume given in the last feeding or greater than 150 mL when continuous feeding is in progress, replace the residual and delay the next feeding for 1 to 2 hours.

• Perform a fingerstick blood glucose every 4 to 6 hours as ordered for hyperglycemia until the patient demonstrates a normal blood glucose level.

• If nausea occurs, stop the feeding and notify the physician.

• Record an accurate intake and output record. Dehydration can occur because of diarrhea or the high glucose content of the formula.

• If persistent diarrhea occurs, notify the physician.

TOTAL PARENTERAL NUTRITION

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is a method of delivering total nutrition through a catheter placed in a large central vein (e.g., subclavian vein). A large vein with high blood flow is needed to dilute the solution rapidly. The solution may also be infused through a port implanted in the patient’s chest wall, or a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC). These options are used for patients receiving long-term therapy, such as victims of massive burns, intestinal obstruction, inflammatory bowel disease, AIDS, or cancer chemotherapy.

TPN is composed of high concentrations of carbohydrates as the main source of energy. Protein is provided through solutions of all amino acids. Solutions of other essential nutrients are also added to the infusion. Fatty acids are administered through lipid solutions that are infused daily or several times per week. TPN solutions are started slowly to allow the body to adjust to the high level of glucose concentration and the hyperosmolality (increased concentration of solutes within the fluid) of the solution. Usually 1000 to 2000 mL is administered the first 24 hours. After the first 24 hours, the infusion is increased until the desired volume is met. Monitoring of TPN should be ongoing. The infusion rate should be assessed through out the shift. If the rate is lower or higher than the prescribed rate, you should adjust the infusion to the correct flow rate. Attempts should not be made to catch up if the rate has slowed. The rapid infusion of glucose can be harmful to the patient. Table 27-5 summarizes the steps for monitoring TPN.

Table 27-5

Monitoring Total Parenteral Nutrition*

| ITEM TO ASSESS |

WHEN TO ASSESS |

| IV site (PICC, central line, MediPort) |

Every 4 hours. Observe for redness, swelling, or drainage from site. |

| Patient response |

Every shift. Observe for signs of restlessness or discomfort. |

| Blood glucose |

Every 6-8 hours. Report abnormal levels to the physician. |

| Vital signs |

Every 4-8 hours. Abnormal vital signs may signal development of complications. |

| Weight |

Daily or weekly as ordered. Evaluates patient’s response. |

| Intake and output |

Every shift. Abnormal urinary output may signal hyperglycemia or altered kidney function. |

| Flow rate |

Every 4 hours. Prescribed flow rates should be followed to prevent hyperglycemic intolerance to TPN. |

| Electrolytes, CBC, BUN |

Daily or as ordered. Evaluates patient’s response. |

| Nutritional status |

Ongoing. Includes weight, albumin levels, status of muscle mass. |

Key: BUN, Blood urea nitrogen; CBC, complete blood count; IV, intravenous; PICC, a peripherally inserted central catheter.

*Baseline levels of blood chemistry, vital signs, weight, and nutritional status should be completed prior to beginning total parenteral nutrition (TPN) infusion. Compare ongoing monitoring to baseline results.

Elder Care Points

Elderly patients are at risk for fluid overload when receiving large volumes of intravenous fluids. Patients should be assessed for symptoms of fluid overload, including increased pulse rate, cough, respiratory distress, crackles on auscultation of the lungs, and imbalance in intake and output.

APPLICATION of the NURSING PROCESS

The steps of the nursing process are applied when caring for patients with NG or intestinal tubes.

Assessment (Data Collection)

• Assess reason for the tube. This information is necessary for evaluating the tube’s effectiveness.

• Assess patient’s understanding of the procedure.

• Assess function of the tube at least every 4 hours.

• Assess for signs of complications (i.e., nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention, abdominal pain, respiratory distress).

Nursing Diagnosis

Nursing diagnoses appropriate for patients requiring nutritional assistance are as follows:

• Risk for deficient fluid volume related to diarrhea or excessive vomiting

• Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements related to anorexia or NPO status

• Risk for injury related to aspiration of stomach contents into the respiratory tract from difficulty swallowing

Planning

Establish goals/expected outcomes based on the nursing diagnoses chosen. Examples of goals/expected outcomes are as follows:

• The patient will tolerate food and fluids without vomiting.

• The patient will consume at least 90% of all meals.

• The patient’s breath sounds will remain clear without evidence of aspiration of food or fluids.

• The patient will gain 2 lb by time of discharge.

• The patient’s stools will be formed.

Implementation

Nursing measures include frequent mouth care to prevent drying and cracking of the mucous membranes. To keep the mouth and lips moist, swab the oral cavity with a gauze pad or cotton swab that has been moistened with normal saline or water.

The nostrils often become dry and tender. If not contraindicated, a room humidifier can be helpful for the patient who is experiencing nose and throat discomfort. The nares should be cleansed with a swab and warm water daily or as needed. Water-soluble lubricant can be used on the nares. Other nursing actions include the following:

• Provide freedom of movement by securing the tubing to the patient’s clothing to permit maximum activity without pulling on the nares.

• Do not permit the tubing to be kinked, as the flow of tube feeding will be cut off.

• Keep the environment clean, quiet, and well ventilated.

Patient Teaching 27-1 provides information to discuss with patients or caregivers of patients with NG or intestinal tubes.

Patient Teaching 27-1

Patient with a Nasogastric or Intestinal Feeding Tube

Discuss the need for and advantages of having a nasogastric (NG) or intestinal tube in place. Teach the patient or primary caregiver the following:

• Perform oral care every 2 hours while awake to decrease mouth dryness; keep lips moistened.

• Be aware of the possible side effects from tube feeding, such as nausea, diarrhea, constipation, vomiting, or hyperglycemia.

• Keep the tube taped to the nose or face and attached to gown or clothing so that it does not hang lower than the stomach or point of entry into the patient’s body.

• Keep the patient sitting up at an angle of at least 30 degrees for 1 hour after feedings to prevent reflux and possible aspiration of formula.

• Administer tube feedings at room temperature. Keep open formula refrigerated between feedings.

• Discard prepared or open refrigerated formula after 24 to 48 hours.

• Aspirate gastric fluid from the tube to check placement before giving each feeding (for nasogastric tube).