Pain, Comfort, and Sleep

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Discuss the application of The Joint Commission pain standards in planning patient care.

2 Explain why pain is considered the “fifth vital sign.”

3 Explain the physiology of pain using the gate control theory.

4 Describe the use of a variety of nursing interventions for pain control, including biofeedback, distraction, guided imagery, massage, and relaxation.

5 Describe the need for normal sleep.

6 Discuss how the need for sleep changes over the life span.

7 Delineate factors that can interfere with sleep.

8 Define the sleep disorders insomnia, sleep apnea, and narcolepsy.

1 Assist the patient in accurately describing sensations of pain and discomfort.

2 Accurately and appropriately record the patient’s report of pain using clear, descriptive terms.

3 Evaluate the effects of various techniques used for pain control.

4 Assist the patient using a transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) unit.

5 Evaluate the effects of pain medication, and accurately report and record observations.

6 Assist with the care of patients receiving patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) or epidural analgesia.

7 Assess a patient regarding sleep difficulties.

8 Develop a plan designed to assist the patient in getting adequate sleep.

analgesic ( , p. 610)

, p. 610)

biofeedback (p. 608)

bolus (p. 610)

continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) (p. 616)

distraction (p. 608)

endorphins ( ) (p. 601)

) (p. 601)

epidural analgesia ( , p. 613)

, p. 613)

gate control theory (p. 600)

guided imagery ( , p. 608)

, p. 608)

hypnosis (p. 608)

insomnia (p. 616)

massage (p. 608)

meditation (p. 608)

narcolepsy (p. 616)

non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep (p. 613)

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) ( , p. 609)

, p. 609)

pain (p. 599)

patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) ( , p. 610)

, p. 610)

rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (p. 613)

relaxation (p. 607)

sleep apnea (p. 616)

transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) ( , p. 605)

, p. 605)

PAIN AND DISCOMFORT

Pain (feeling of discomfort strong enough to be intrusive and to affect or interfere with normal activity)is experienced by the majority of patients sometime during their health care experience. Surgical patients experience postoperative pain, and the condition requiring surgery may also cause pain. Many medical conditions, ranging from a headache to a myocardial infarction (heart attack), can cause pain. Fever causes generalized discomfort. Cancer, infection, fractures, cuts and abrasions, indeed the majority of illnesses and conditions are accompanied by varying degrees and types of pain.

There is no accurate objective measurement of pain. An electrocardiogram can indicate whether or not a patient’s heart is beating correctly, and an elec troencephalogram can verify abnormal brain activity, but there are no such tests for pain. It can only be assumed that patients will experience pain based on their diagnosed condition. Pain has historically been regarded as a symptom of a condition to be diagnosed and treated, thus eliminating the pain. For example, based on past experience, it was understood that patients with appendicitis experience severe pain. Following surgery, it was expected that they would experience significant incisional pain for the first day or two, following which the amount of pain would steadily decrease with each passing day until it ceased altogether. Using this model, continued severe pain was judged either as an indication of complications, or, in the absence of such complications, as drug-seeking behavior in a patient who has become addicted to the pain medication. Now, however, experts in the field regard pain as a condition rather than a symptom, and ideas about pain and its management are changing.

In the past, pain control measures were based on the health care providers’ understanding of how much pain the patient should have, based on the diagnosis. The physician ordered what was believed to be an appropriate amount of pain medication, and it was dispensed in response to the patient’s request and the nurse’s assessment of the actual degree of need. For example, the physician might order hydromorphone (Dilaudid) 2 to 4 mg every 4 to 6 hours subcutaneously for pain as needed, and the nurse would then determine how frequent and how large a dose within these limits would keep the patient comfortable.

The approach to pain control has changed. The establishment of pain assessment and treatment standards and the expansion of pain management options are two factors that have contributed to these changes. In 1999, The Joint Commission established standards related to pain that focus on the patient. The standards relative to direct patient care state the following:

• Patients have the right to appropriate assessment and management of pain.

• Pain is assessed in all patients.

• Patients are educated about pain and managing pain as part of treatment, as appropriate.

• The discharge process provides for continuing pain care based on the patient’s assessed needs at the time of discharge.

Pain assessment is now performed along with each assessment of vital signs, and pain is now considered the “fifth vital sign.” Documentation of the findings must be completed. Hospitalized patients are now frequently using patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) machines. These allow patients to administer medication within safe boundaries based on their perception of pain. Medication is administered intravenously, with the patient controlling when administration occurs, within boundaries prescribed by the physician. There is also an increased use of nonpharmacologic methods of pain relief, such as biofeedback, distraction, guided imagery, massage, and relaxation techniques, each of which is discussed in this chapter. Other complementary treatments, such as chiropractic, acupuncture, and acupressure, are also being used (see Chapter 32).

The fentanyl patch is a newer method for controlling chronic pain. It is replaced every 72 hours and can be managed at home by the patient. For postsurgical patients, a new form of pump allows the patient to administer pain medication directly to the incision site, rather than systemically.

THEORIES OF PAIN

Pain is defined as a feeling of discomfort, distress, or suffering caused by the stimulation of nerve endings. Acute pain is often a warning of potential or actual tissue damage, and allows the sufferer to withdraw from the source or to seek help in relieving symptoms.

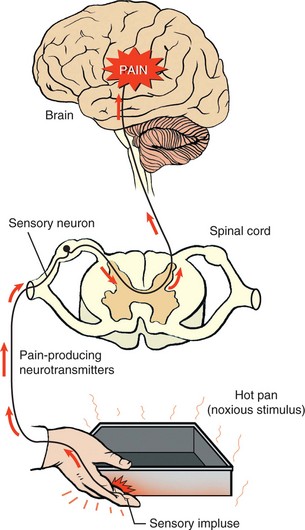

Pain is transmitted to the brain through the nervous system. This is done through afferent (sensory) neurons leading to the spinal nerves, and then to the brain. Once the signal is interpreted, the brain sends out a message to the body to respond (Figure 31-1).

Gate Control Theory

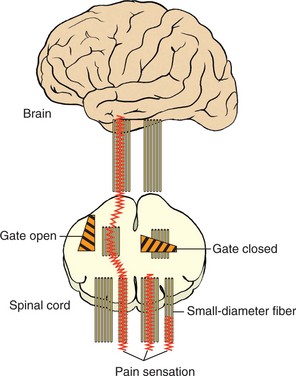

The gate control theory was first described by Melzack and Wall in 1965. Pain transmission is viewed as being controlled by a gate mechanism in the central nervous system (Figure 31-2). Stated in the simplest terms, opening the gate allows the transmission of pain sensation and closing the gate blocks this transmission. Several ideas that impact nursing practice are part of the gate control theory, including

• The gate may be opened by activity in the small-diameter nerve fibers from such things as tissue damage. Activity in the large-diameter nerve fibers, such as that provided by massage or vibration, seems to close the gate.

• Brainstem impulses caused by a high sensory input seem to close the gate, whereas a lack of this input allows the gate to open. This may be why people who are bored or lonely can experience a greater intensity in their pain than when they are occupied or distracted by such things as visitors or a particularly interesting program or activity.

• The cerebral cortex and thalamus play a role by opening the gate with impulses originating from an increase in anxiety, or by closing it with impulses originating from a decrease in anxiety. For example, fear that the pain will get worse and not be controlled can increase the intensity; knowing that pain can be and is being controlled can reduce the intensity.

Endorphins

Endorphins are endogenous, naturally occurring, opiate-like peptides that reduce or block the perception of pain. The word “endorphin” comes from “morphine” and “endogenous” (from within). Like morphine, endorphins attach to nerve endings in opioid receptors and block pain transmission. Both physiologic and psychological stressors can release endorphins, resulting in a reduction in pain and an increase in the sense of well-being.

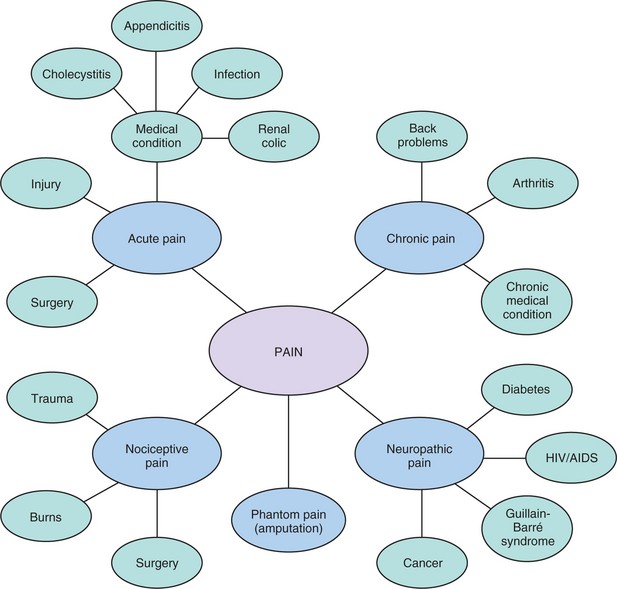

TYPES OF PAIN

The type and intensity of pain the patient is experiencing will assist in selecting methods that will best relieve the patient’s discomfort. The patient’s verbal description of pain, nonverbal signs of pain, and physiologic indicators of pain may vary according to the type of pain the patient is experiencing. Treatment decisions should be based on assessment that considers all of these factors. Concept Map 31-1 depicts the various types of pain.

Acute Pain

Acute pain is usually associated with an injury, medical condition, or surgical procedure. It is of short duration, lasting from a few hours to a few days. Injuries causing acute pain may include burns, bone fractures, and muscle strains. Medical conditions causing acute pain may include pneumonia, sickle cell crisis, angina, herpes zoster, inflammations, infections, and blockages. Acute pain may be described as aching, throbbing, or searing. The patient may be agitated or restless, and may protect the painful area by splinting, or supporting the area. Pain may also be accompanied by an increase in heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. Acute pain may worsen in the presence of anxiety or fear. The cause is usually easily determined, and the pain well controlled with analgesics (pain medications), surgery, or other techniques. Once the cause is removed, acute pain will be relieved.

Chronic Pain

Chronic pain may continue for months or possibly years. Chronic pain is associated with ongoing conditions, such as arthritis and back problems. There are many medical problems that can cause chronic pain. The limitations imposed by chronic pain can cause long-lasting psychosocial effects for the patient, due to necessary changes in lifestyle. Chronic pain may be described as dull, constant, shooting, tingling, or burning. The increased heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate seen with acute pain are often absent with chronic pain. A combination of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments is recommended to alleviate chronic pain. This would include combining medication with treatments such as guided imagery, application of heat and cold, and massage (see Concept Map 31-1).

Nociceptive Pain

Nociceptive pain involves injury to tissue in which receptors called nociceptors are located. Nociceptors may be found in skin, joints, or organ viscera. Injuries triggering nociceptive pain may be caused by trauma, burns, or surgery. There are four phases of pain associated with nociceptive pain. Transduction is the first phase and begins when tissue damage causes the release of substances that stimulate the nociceptors and start the sensation of pain. Transmission is the second phase and involves movement of the pain sensation to the spinal cord. Perception, the third phase, occurs when pain impulses reach the brain and the pain is recognized. The fourth phase, modulation, occurs when neurons in the brain send signals back down the spinal cord by release of neurotransmitters. Treatment of nociceptive pain may be directed toward one or all of the four phases. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) work by blocking the production of the substances that trigger the nociceptors in the transduction phase. Drugs that interfere with the transmission phase include opioids. Nonpharmacologic treatments such as distraction and guided imagery may be effective during the perception phase. Drugs that block neurotransmitter uptake work in the modulation stage.

Neuropathic Pain

Neuropathic pain is usually associated with a dysfunction of the nervous system, specifically an abnormality in the processing of sensations. Pain receptors in the body become sensitive to stimuli and send pain signals more easily. Nerve endings grow additional branches that send stronger pain signals to the brain. As the branches grow, they influence touch and warmth receptors and these receptors begin to send pain signals. In some cases, the pain signal that normally moves from the periphery toward the brain reverses and is sent in the opposite direction. These changes in the nervous system are often associated with medical conditions rather than tissue damage. Diabetes, Guillain-Barré syndrome, cancer, HIV, and nutritional deficiencies are examples of medical conditions that are associated with neuropathic pain. Analgesics and opioids usually do not relieve neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain is sometimes managed with common analgesics such as those in the NSAID family, but also increasingly with adjuvant medications such as tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and corticosteroids.

Phantom Pain

Phantom pain occurs after the loss of a body part from amputation. The patient may “feel” pain in the amputated part for years after the amputation has occurred. If this is not controlled with conventional methods, pain may be controlled by the use of continuous electrical stimulation from electrodes surgically implanted in the thalamus.

APPLICATION of the NURSING PROCESS

According to pain specialists, “pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever he says it does” (McCaffery and Pasero, 1989). In other words, only the patient knows what hurts and how much, and interventions must be based on the patient’s own assessment of the degree of pain and the need for pain relief.

Perception of Pain: One of the most difficult aspects of pain management is the assessment of pain and the evaluation of the effectiveness of interventions. Cultural background influences how people may show pain (Cultural Cues 31-1). Some cultures teach that outward expressions of pain are to be avoided. Men in some cultures may believe that denying the presence of pain shows bravery and strength. Care must be taken to ensure that adequate pain management is provided. The elderly may not express pain because they mistakenly believe it is a logical consequence of aging, because they don’t want to be a bother, or because they have been culturally trained not to complain about pain.

Observable indicators of pain include moaning, crying, irritability, inability to sleep, grimacing or frowning, restlessness, and a rigid posture in bed. Remember that these things can also indicate sorrow, worry, fear, and fatigue. In addition, some stoic patients may show none of these outward expressions of pain. Other detectable signs of pain can be an elevation in blood pressure, heart rate, and respirations or the presence of nausea or diaphoresis. Fully assess the patient’s pain, and encourage the patient to express the perception of the pain being experienced. Some patients may perceive pain to be less than or greater than what you may have seen before for the same condition.

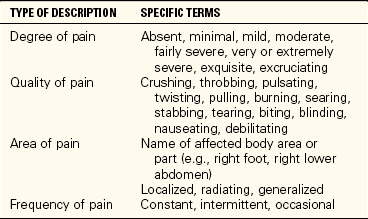

Alert adult patients may be able to use specific words to describe their pain. However, even for adults, it can be difficult to describe and tell how much pain is present. Table 31-1 gives some terms that can be used to describe pain. Be aware of any communication blocks that may prevent the patient from adequately describing the pain. For example, patients who speak a foreign language may require a translator to adequately describe their pain.

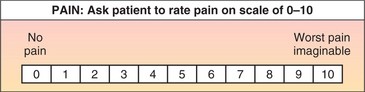

Pain Scales: A variety of pain scales are available to assist patients in communicating their pain level. A number scale is often used to assist the patient to rate the level of pain, with 0 being pain free and 10 being the worst pain imaginable (Figure 31-3). When requesting pain medication and when assessing the degree of relief following the dose, the patient can refer to the number scale. For example, David Randel, who had an appendectomy this morning, may describe his incisional pain as being 8 on a scale of 0 to 10, or very bad, but not the worst possible pain. One hour after receiving his medication, he may describe his pain as being a 3, not gone but greatly reduced, allowing him to move about and rest in reasonable comfort.

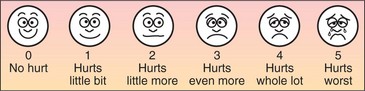

Children, as well as some adults, may find a number scale difficult to use. A picture scale showing faces in varying degrees of pain can also help assess pain (Figure 31-4). The FLACC (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, and Consolability) scale is used for preverbal or noncommunicative children (Assignment Considerations 31-1). For infants, one of several scales is used: the NIPS (Neonatal Infant Pain Scale), CRIES (Crying, Requires oxygen to maintain saturation, Increased vital signs, Expression, and Sleeplessness), and PIPP (Premature Infant Pain Profile).

For the confused patient, nonverbal cues that pain is being experienced may include restlessness, rocking, pacing, rigidity, guarding, wincing, crying, grimacing with movement, new inability to sleep, hypersensitivity to touch, withdrawal from usual contact with others, moaning, and grunting. Family or close friends may be able to provide input on how the individual has expressed pain in the past.

The scale selected to assist in determining the presence and intensity of pain must be indicated on the patient care plan so that it is used consistently by staff.

Nursing Diagnosis

Accurate nursing diagnosis for the patient with pain is based on the patient assessment. Because pain is an individual experience, the reported pain may vary from patient to patient, even though they share a similar medical diagnosis. Box 31-1 gives examples of possible nursing diagnoses for the patient with pain.

Planning

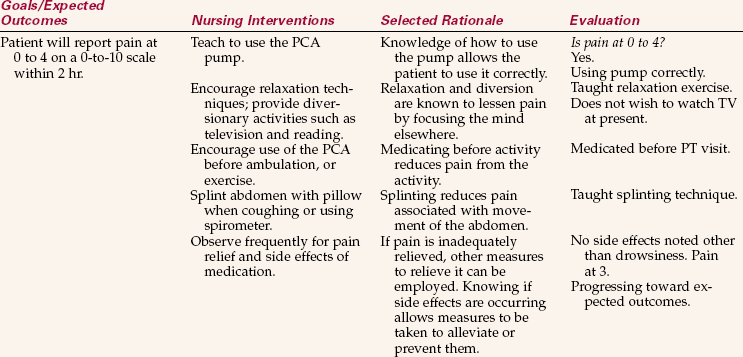

The plan of care must include pain assessment and management. This should include realistic goals with specific time frames for achieving results. A possible goal might be “patient will report pain at a level of less than 3 on a 0-to-10 scale within 2 days.” Goals should be realistic; a patient with a chronic condition may not be pain free, even with the use of analgesics.

Implementation

Pain is an individual experience. Medications or treatments that prove effective for one patient may not relieve symptoms as well for another patient. Different methods may need to be tried alone or in combination before the patient has effective pain relief (Nursing Care Plan 31-1).

Nonmedicinal Methods of Pain Control: Just as an individual may get better relief from one medication than another, there will be a variation in the effectiveness of nonmedicinal pain control methods. Appropriate use of nonmedicinal methods of pain control in some cases can greatly reduce the amount of medication needed. However, this does not mean that the patient should be denied medication to control the pain. As patients gain control and as changes in their condition reduce overall pain, they will voluntarily reduce the use of medications.

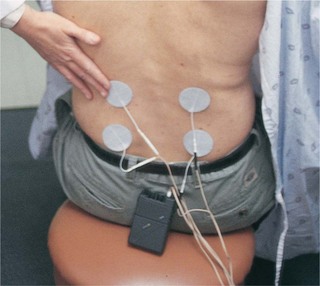

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation.: Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) uses a small electrical stimulator attached to electrodes to block pain. This therapy is available in high-frequency stimulation and low-frequency stimulation. Acute pain may be treated with conventional high-frequency TENS therapy, whereas low-frequency TENS therapy is more effective in the treatment of chronic pain. The electrodes are placed on the skin around the area of pain. Low-level current running between the electrodes acts to block the pain sensation. The patient can control the intensity and interval of the current with the dials on the stimulator (Figure 31-5). A health care professional trained in its use should initiate the application of the TENS unit. This may be a physical therapist, but may also be a nurse or physician.

The use of TENS requires a physician’s order. TENS for the relief of postoperative pain is generally most effective when the patient has received instructions on the use of the device before surgery. Postoperative pain and analgesic medications make teaching more difficult than it would have been before surgery for most patients. TENS may also be ordered following traumatic injuries. The occasional patient will not tolerate TENS stimulation well. If this is the case, discontinue treatment and notify the physician (Skill 31-1).

Percutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation.: A treatment showing promise for relief of lower back pain, such as that due to sciatica, and for relief of some severe headaches is percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PENS). An electric current is sent through thin needle probes positioned in the soft tissues and muscles of the back. A series of intermittent treatments using the electric current are given.

Binders.: Binders are cloths wrapped around a limb or body part. They are effective in relieving pain associated with strains, sprains, and surgical incisions. They support the surface and internal tissues during movement, coughing, and other activities. For example, an abdominal binder may be ordered to give additional support and provide comfort after abdominal surgery (see Chapter 38, Figure 38-11).

Application of Heat and Cold.: The application of heat or cold, or the alternate application of first one and then the other, can often soothe or relieve pain from muscular strain or overwork. It is also effective in reducing pain associated with healing tissues.

Sources of warmth include warm water compresses, warm blankets, Aquathermia K-Pads, tub and whirlpool baths, and chemical self-heating packs (Figure 31-6). The use of heat-producing equipment may require a physician’s order. When applying heat, check the temperature carefully to avoid burning the patient. Remember that very young and very old patients have skin that is more sensitive to heat damage. In addition, patients with altered levels of consciousness, impaired movement and feeling, or poor circulation may not be aware when something is too hot. These patients can suffer severe burns in a short period. All patients should be closely monitored if heat applications are being used.

Cold is particularly helpful in reducing swelling and can also be effective in calming muscle spasms and reducing the pain in joints and muscles from a variety of causes (Figure 31-7). Gentle ice massage of painful muscles can be done using ice that has been frozen in a paper cup. The edge of the cup is torn away to expose the ice, the remaining cup is used as a handle, and the area is massaged with the ice surface. A bag of frozen peas can be used as an ice pack. Cold is most frequently applied in the form of cold or iced compresses. Some patients will have a poor tolerance for cold treatment, so be alert to the patient’s response when using cold applications. Occasionally, patients will have an increase rather than a decrease in pain when ice is applied. To prevent skin damage, ice should be in contact with the skin for only a few minutes at a time, under direct supervision. Ice packs should be applied with a towel or other barrier between the pack and the skin, and not left in place for more than 15 to 20 minutes.

Relaxation.: Relaxation or tension release is helpful in reducing pain and in allowing the patient to obtain greater relief from pain medications. It is a physical technique that involves conscious relaxation of muscle groups. Before beginning, the patient should be made comfortable in a quiet environment. Many people find that a darkened environment helps them relax. The patient is instructed to first tighten and then release the muscles. Initially, the patient is encouraged to pay close attention to the difference in the feeling of tension versus relaxation. Frequently, relaxation is done progressively. Have the patient begin by tensing and relaxing (or just relaxing) the toes and feet and then the ankles, calves, knees, thighs, lower abdomen (or stomach), upper abdomen (or chest), shoulders, arms, hands and fingers, neck, face, and head. These directions are given slowly, one body area at a time, with a short space of quiet between each directed relaxation. After a session or two, most patients can do this technique for themselves. Some people with chronic tension-related pain go to sleep this way every night. There are a variety of relaxation tapes available to assist patients who find this technique helpful.

Biofeedback.: Biofeedback is a specialized relaxation technique using a machine that measures the degree of muscular tension with skin electrodes. The machine has colored lights that change (usually red to yellow to green) and a tone that changes in pitch from higher to lower as the patient relaxes muscular tension. The patient learns to use relaxation techniques or imagery to decrease tension. The degree of relaxation is measured by the biofeedback machine, causing the lights and the frequency tones to change, giving the patient immediate feedback on the degree of relaxation being achieved.

Distraction.: Distraction assists the patient to focus on something other than the pain. Patients frequently do this inadvertently, such as when they joke with visitors and for the moment forget their pain. Unfortunately, nurses sometimes take this as proof that the patient is not in pain at all and see the patient’s request for medication as drug-seeking behavior. In fact, the patient still hurts but is just focusing elsewhere.

Television, radio, playing a game, conversing with a friend or volunteer, reading, playing cards, using a computer, or even thinking about something else may all act as distractions. However, remember that the distraction does not make the pain go away; it merely diverts the attention elsewhere for a time. After the distraction is over, such as at the end of the television program or a visit, the patient may be more aware than ever of the pain. Distraction may be particularly helpful while waiting for an administered dose of medication to take effect. By the time the distraction ends, the pain has begun to be relieved by the analgesic.

Guided Imagery and Meditation.: These methods differ from relaxation in that they are mental rather than physical techniques. In guided imagery (verbally guiding the patient to imagine something) as it is used for pain control, patients are assisted to form mental images of a pleasant environment where they are comfortable and happy, such as a favorite vacation place. Patients undergoing painful procedures, such as bone marrow aspiration, can learn to use imagery to “leave” the procedure and mentally go somewhere else while it is occurring. Some people have great difficulty seeing things in their minds and will need verbal direction to hear or feel pleasant sensations, such as the rustle of leaves or the feel of a breeze as it brushes across their cheeks. Many people who do not visualize well can still get great relief from the technique when it calls on their auditory and kinesthetic abilities (Patient Teaching 31-1).

Meditation (focusing on an image or thought) can provide the same relief from a painful situation, but it relies on the use of a focus point rather than the mental creation of an alternate environment. During meditation, individuals focus on a visual point, a sound, or a repeated phrase, or just the pattern of their own breathing. This focuses attention away from the pain or a painful situation and, for many people, induces profound physical relaxation and reduction in blood pressure and respiratory rate.

Music.: Music can be used alone as a source of distraction from pain, and is frequently used effectively in conjunction with other methods. Meditation and relaxation techniques can be done to restful music, and massage can be greatly enhanced by the presence of soft, soothing sound. Also effective is the use of nature sounds, such as tapes of the ocean, a flowing stream, or the sounds of the wind and birds in the trees. Listening with headphones allows patients to enjoy their own preferences in music without disturbing others.

Hypnosis.: Hypnosis is also called therapeutic suggestion. It involves inducing a trance-like state using focusing and relaxation techniques and giving the patient suggestions that may be helpful after the return to an alert state of consciousness. Hypnosis should be done by someone trained in the technique. Hypnosis is only possible and effective when the individual is able to cooperate with the technique; it is pointless to urge it on someone who truly does not want to be hypnotized.

Massage.: Massage has long been used to induce relaxation and bring relief from muscle and structural pain. A nightly back rub can bring much comfort to the bedridden patient. Long firm strokes, softer circular strokes, and gentle pounding stimulate circulation, relax muscles, and increase the patient’s sense of well-being. This gift of direct comfort from nurse to patient, perhaps more than any other, demonstrates the caring relationship so important to good nursing care. The use of lotion warmed between the hands and then applied to the patient’s back refreshes the skin and relieves dryness and itching (Figure 31-8).

Conditions such as a healing surgical wound or inflammation of the tissues or vessels may preclude direct massage to the area of pain. In such cases, firm massage to another area of the body may allow the patient to focus away from the area of pain. Also, massage distal or proximal to the point of pain may relieve pain while avoiding direct stimulation to an injured site.

Chiropractic, acupuncture, and acupressure therapies are also used for pain management. These are discussed in Chapter 32.

Medical Methods of Pain Control:

Analgesic Medications.: When pain medications are ordered for patients experiencing pain, you are responsible for monitoring the patient’s pain level and administering the medication as ordered. The patient must also be monitored for effectiveness of the medication after administration. The time frame for reassessment will vary depending on the route of administration.

There are four basic categories of medications for the relief of pain. They are (1) nonopioid pain medications, a category that includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); (2) cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors; (3) narcotics or opioids; and (4) adjuvant analgesics. This fourth group includes drugs not primarily regarded as analgesics but that have been proven to be effective in the relief of certain types of pain; or that work with standard analgesics to produce better pain control. COX-2 inhibitors are a type of drug that selectively blocks the COX-2 enzyme, thought to play a role in the cause of arthritis pain. They do not block the COX-1 enzyme, which protects the gastrointestinal system. Therefore, these drugs are not supposed to cause the GI side effects such as gastritis and ulcers that NSAIDs may cause. Table 31-2 gives examples of the drugs in these four categories.

Table 31-2

Categories of Analgesic Medications

Key: COX-2, Cyclooxygenase-2; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Analgesic (pain-relieving) medications, whether prescription or nonprescription, are ordered by the physician for the patient. Check the name of the drug, dosage, route, and frequency. If the medication is ordered “as needed” (PRN), the order must include the circumstances under which the drug may be given, such as “PRN for back pain.” Analgesics may be given by a number of routes, including oral, intramuscular (IM) injection, intravenous (IV) injection or infusion, PCA, and epidural infusion.

Oral Medications.: Oral medications have been traditionally used for mild to moderate pain. Recent advances, however, have made available products such as time-released oral morphine, which may be used effectively for severe pain. This dosage form is particularly helpful for patients with chronic severe pain, such as occurs in patients with cancer. The use of this type of medication has allowed many individuals with severe chronic pain to return to work and a near-normal life for long periods of time despite serious illness.

Topical Medications.: Various topical creams, such as capsaicin creams, may provide relief for muscle or joint pain. Medication patches, such as fentanyl (Duragesic) patches, allow the analgesic medicine to be absorbed slowly through the skin. Lidoderm patches are often helpful for neuropathic pain. Fentanyl is approved for relief of severe chronic pain only.

Injected Medications.: Intramuscular or subcutaneous injection of pain medication is usually used for severe pain and only for a relatively short time. Medication given by this method has the advantage of lasting several hours, but administration is painful for the patient, and prolonged use can be detrimental to the tissues. Many individuals, particularly children, are fearful of injections. Small children and elderly adults also have relatively few sites with adequate muscle tissue; therefore, they can only safely receive medication by this route for a short time. Intramuscular injection requires careful technique to avoid nerve injury.

Intravenous Medications.: Intravenous pain medication may be given as a bolus (concentrated dose given rapidly); as a slow push (over a few minutes); as an intermittent infusion; or by continuous infusion. These techniques are discussed in Chapter 36.

Recent studies have shown that continuous infusion of opioids is less effective at pain control and may more easily result in overmedication. Administration via PCA (discussed in the next section) has become the preferred route for most patients, although continuous infusion may still be the route of choice for control of severe chronic pain, such as that experienced by some terminally ill cancer patients.

Intramuscular injections are used less today than in the past. The dose given is larger than that given IV, and the length of time the medication is effective is extended as a result of the slow absorption from the muscular tissue. They are more commonly used for immediate relief of severe pain when an IV line is not in place, although some physicians and patients still prefer the IM route (Assignment Considerations 31-2).

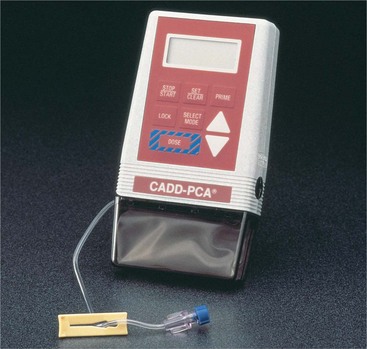

Patient-Controlled Analgesia.: Currently, the most common method used for injectable opioids in acute care is patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) (analgesia doses

controlled by the patient). This method uses one of a variety of programmable pumps (Figure 31-9). The medication comes in special cartridges or syringes, prediluted to an appropriate strength. The pump is programmed to administer the prescribed dose each time the patient pushes a button, within limitations set by the physician. The doctor’s order will specify the size of the dose and the minimum time between doses. The pumps are programmed by the RN or pharmacist. The physician may also order an initial dose or even a continuous infusion dose to be programmed along with the intermittent dose. Within the limits set by the physician’s order, the patient can then choose how often to receive the medication. Studies show that this level of control greatly reduces patient anxiety about pain by putting the patient in more control, and that most patients actually use less rather than more medication. Before caring for a patient with a PCA pump, it is important to understand how it is programmed, how the medication is inserted, and how the machine is locked to prevent anyone from tampering with the medication or the programming (Skill 31-2).

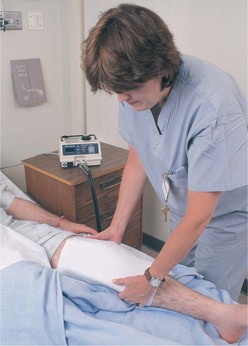

PCAs are commonly attached to an IV line, but the medication may also be injected into the subcutaneous tissue on the abdomen. This second method is often seen when the pumps are used to administer medication to nonhospitalized patients using small, portable pumps. These pumps may also be used for nonhospitalized patients with IV lines or ports (Figure 31-10).

Epidural Analgesia.: The epidural route has been used for anesthesia for a number of years. Epidural analgesia, however, is one of the newest forms of pain control. An anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist places a fine catheter in the epidural space near the base of the spine, then connects the catheter to a small battery-operated programmable pump. The pump administers an opioid analgesic into the epidural space (outside the dural space), either as a bolus followed by a continuous infusion or as repeated bolus doses, as ordered by the physician. This method is effective in controlling pain while allowing the patient to remain alert. Its uses include pain relief for obstetric patients in labor, postoperative patients, and patients with cancer. Possible side effects from the opiate component of the infusion include respiratory depression, pruritus, nausea and vomiting, constipation, urinary retention, low pulse rate, and hypotension. Because of the infrequent but possible occurrence of potentially dangerous side effects, particularly respiratory depression, patients receiving epidural analgesia are monitored closely. This often includes being placed on an apnea monitor and/or a pulse oximeter for the first 12 hours. The primary responsibility for caring for the epidural catheter lies with the RN. The LPN/LVN will monitor the patient for response to the medication (Steps 31-1).

Evaluation

Frequent evaluation of pain control measures is important. As the patient’s condition changes, so may the need for pain control. A patient’s perception of pain may increase with anxiety, which can be caused in part by ineffective pain control measures. As the patient’s condition improves, various interventions, such as medication, may need to be tapered or discontinued.

SLEEP

Proper rest and sleep are important, and may be interrupted for patients due to pain, fear, or stress, or as a side effect of medications and necessary treatments. An important nursing action is to assist the patient in obtaining enough sleep to aid in healing and maintaining health.

FUNCTIONS OF SLEEP

Although much of the actual function of sleep is not known, it is clear that adequate rest and sleep are important factors in general health and recovery from illness. These activities also play a major role in pain control. Being rested increases pain tolerance and allows an improved response to analgesia.

People who do not get adequate rest often suffer from daytime drowsiness and fatigue. Irritability, depression, and a decrease in concentration and memory are also common. There is an increase in the frequency of both accidents and illness.

STAGES OF SLEEP

Normal sleep follows a course through two states, non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. REM sleep is time in which you dream, and is a period of a high level of activity. Heart rate, blood pressure, and respirations are similar to that when awake. NREM sleep is believed to be the time when the body receives the most rest. During this stage, heart rate, blood pressure, and respirations decline. During the course of the night, a person will go through these two states in 90-minute cycles, repeating the cycles five or six times a night.

NREM sleep is divided into four stages. The first is a transition stage. As a person falls into a light sleep, the muscles relax. This stage usually lasts a few minutes, followed by stage 2. In stage 2 the person falls into a deeper sleep. Brain wave activity becomes larger, and there are bursts of electrical activity. This stage lasts 10 to 20 minutes.

As stage 3 begins, the person enters a period called delta sleep or slow-wave sleep, named for the high-voltage slow brain waves that occur. Respirations and heart rate slow in this stage, and the body becomes immobile. This stage lasts 15 to 30 minutes, resembling a coma, after which the person enters stage 4. This is the deepest stage of sleep. During this stage, it is difficult to arouse the sleeping person. This stage lasts approximately 15 to 30 minutes.

This is followed by a period of REM sleep. Brain waves become active, almost the same as when awake. This is the stage in which dreams occur, and it lasts approximately 20 minutes. About 25% of the night is spent in REM sleep, and the duration will increase with each sleep cycle during the night.

NORMAL SLEEP REQUIREMENTS

The amount of sleep an individual needs varies from person to person, and the amount of sleep needed also changes as a person passes through the life cycle.

Newborns require at least 16 hours of sleep per day, but this is distributed throughout the 24 hours rather than a having a true sleep cycle. They also spend about 80% of the time in REM sleep. It is speculated that the neural activity occurring during REM sleep is necessary for brain maturation. By 2 to 3 months of age, they begin to develop a true sleep cycle and REM sleep falls to about 50%. By age 1, the child is sleeping 12 to 14 hours per day, and continues to need this amount of sleep until reaching the age of preschool, when the amount needed drops to 11 to 13 hours.

School-age children require 10 to 11 hours of sleep per night. REM sleep decreases and deep sleep increases, allowing for necessary repair of damaged cells and the growth of new cells. Insufficient sleep can hamper both normal growth and daytime learning activities.

Growth hormone is secreted during deep sleep in both children and adolescents. Adolescents, however, have very different sleep patterns from younger children and adults. Although they need to get 9 to 10 hours of sleep a night, their internal clock does not trigger feelings of sleepiness until late at night due to a natural shift in circadian rhythms that occurs at this period in development. Because school hours demand that they waken by 6:30 or 7 A.M., many teens are chronically sleep deprived, affecting temperament, academic performance, and ability to stay awake at critical times, such as when driving a car.

Most adults require approximately 8 hours sleep a night, but many get less. Deep sleep time decreases, and REM sleep occurs for about 20% of the night. Mild to severe sleep disorders plague many adults, including varying degrees of insomnia, and waking multiple times during the night. Sleep difficulties increase during middle age, and can be particularly difficult for menopausal women.

It is a common misconception that the elderly need less sleep. However, such things as nocturia, joint pain, and other physical conditions may interrupt the sleep cycle with increasing frequency. The elderly also tend to have what is called advanced sleep onset’they go to bed earlier and get up earlier than during their younger years. They may also nap during the day. This again represents a shift in the circadian rhythm.

FACTORS AFFECTING SLEEP

Many things can cause disruption of the normal sleep cycle. People who work evening and night shifts often have difficulty in sleep during the day. Workers who change shifts during the month will have even more difficulty in adjusting in order to get enough rest. Students often spend nights studying and find that getting enough sleep can be a problem. Travelers may suffer from jet lag as they go through different time zones. Exposure to sunlight for several hours seems to help reset one’s internal clock. People who snore, or have partners who snore, may find that they are awakened frequently. People who snore also have an increased incidence of sleep apnea, which is linked to an increased frequency of cardiac ailments.

Lifestyle can affect the ability to sleep. Caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol consumption can interrupt normal sleep patterns. Caffeine and nicotine can delay sleep, and alcohol may cause nocturnal awakenings.

Regular exercise can help a person sleep, but exercise too close to bedtime may be overstimulating and keep a person awake. Taking a nap during the day may also disrupt nighttime sleep, and should be particularly avoided if the individual suffers from insomnia.

Stress and illness may also affect sleep. Nighttime worry may keep a person awake or cause awakening in the middle of the night. Illness or discomfort may prevent a person from resting well. An old mattress may contribute to sleeplessness because it is lumpy or no longer properly supportive.

Environmental factors, such as a room that is too hot or too cold, noisy, or with ambient light can also affect sleep. Patients in the hospital have an increase in interruptions of regular sleep due to hospital routines that can cause noise or require turning on lights, or the need to be awakened for such things as medications.

SLEEP DISORDERS

Disorders of sleep can interfere with a person’s quality of life and affect health. Accidents may occur due to a lack of sleep. People with sleep disorders should be treated by a health care practitioner if lifestyle changes or relaxation techniques fail to increase the quality of sleep. Referral to a sleep disorder clinic for testing may prove helpful.

Insomnia

Insomnia is difficulty in getting to sleep or staying asleep at night. This may be short term, lasting only a few nights, or chronic, lasting a month or longer.

Transient insomnia may be caused by stress, excitement, or a change in sleeping arrangements, such as occurs when traveling. The sleep pattern will usually normalize as the life situation settles back to routine.

Chronic insomnia may be the result of an underlying medical, behavioral, or psychiatric problem. Depression can often cause insomnia. Persons suffering from chronic insomnia may require treatment from a health care provider specializing in sleep disorders.

Sleep Apnea

Sleep apnea is a condition in which the person will stop breathing for brief periods during sleep. There are three types of sleep apnea: obstructive, central, and mixed-complex. They can be further classified as mild, moderate, and severe.

Obstructive apnea is the most common type. It is caused by a relaxation of the soft tissues, which allows partial to total obstruction of the airway. The condition may be further complicated by tissue or bony structure abnormalities. A person with obstructive apnea will have visible respiratory effort, but may not be able to move air past the obstruction, causing him to arouse sufficiently to draw breath before falling back into sleep. These individuals often do not remember waking, although it will occur multiple times through the night, even multiple times per hour.

Central apnea occurs due to a failure of the brain to communicate with the respiratory muscles. This results in cessation of breathing with no observable respiratory effort. As the oxygen saturation decreases, the individual resumes breathing. This is much less common than obstructive apnea. Mixed-complex sleep apnea is, as the name implies, a combination of obstructive and central sleep apnea.

Obstructive apnea may be treated with a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device. This uses a small compressor to maintain airflow via a mask or nasal prongs while the patient sleeps. A dental appliance may be prescribed to reposition the tongue or jaw at night. Central apnea does not respond to CPAP, but other treatments are available. Apnea is a problem that should be treated by a specialist.

Snoring

Snoring, or breathing during sleep accompanied by harsh sounds, is caused by vibration and/or obstruction of the air passages at the back of the mouth and nose. This may result from poor muscle tone, excessive tissue, or deformities such as a deviated septum. Obstructed airways due to colds or allergies can also cause snoring. Snoring may be simple, but can also be a symptom of sleep apnea. Heavy snorers may disrupt their own sleep, as well as the sleep of others.

The mild snorer should exercise to develop good muscle tone, and lose weight if needed. Sleeping on the side instead of on the back may help. Remember that snoring can be a symptom of airway obstruction and should be taken seriously. Referral to a physician or sleep disorder specialist may be necessary.

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy is sudden-onset, recurrent, uncontrollable, brief episodes of sleep during normal hours of wakefulness in a well-rested person. These sudden sleep periods may occur at any time and last from a few seconds to more than 30 minutes. For example, patients may fall asleep while reading a book, watching TV, attending a meeting, engaging in conversation, or driving. Symptoms usually begin by the age of 25 and may start as excessive daytime sleepiness. There is currently no cure, but drug and behavioral therapies have proven helpful. Regular exercise and exposure to bright light are recommended. Stimulant medication is often used to prevent daytime sleepiness. The diagnosis of narcolepsy is by clinical evaluation, sleep logs or diaries, and the results of sleep laboratory tests. Most narcolepsy is not inherited.

APPLICATION of the NURSING PROCESS

Adequate assessment of the patient having difficulty sleeping is necessary to provide effective interventions. A thorough history of any problems the patient has had related to sleep in the past should be com pleted. Any current illness or injury should be discussed in relation to comfort and disruption of sleep.

Encourage patients with sleep difficulties to keep a sleep diary. Information to be recorded includes the time they went to bed, when they woke up, and any time they awoke during the night; usual diet; and all medications taken, including sleep aids. They should also include information about where they sleep and anything that disturbs sleep, such as neighborhood noise, a snoring partner, wakeful children, or pets who demand attention in the night.

Nursing Diagnosis

Assessment of the patient allows identification of various nursing diagnoses for the patient with sleep problems. These may be related to the patient’s health as well as sleep disturbances. Box 31-2 lists possible nursing diagnoses for the patient with sleep disturbances. Sleep pattern disturbances may be related to many things, including environmental factors such as noise, health issues, and the necessity of shift work.

Planning

When setting up goals related to sleep disturbances, attention should be paid to the amount of sleep the individual patient needs. A possible goal might be that the patient will sleep undisturbed for 6 hours each night, or awake in the morning feeling rested.

Implementation

Assisting the patient to adjust lifestyle and bedtime habits can allow the patient to obtain a sufficient amount of sleep. Avoiding caffeinated beverages for 6 hours before bedtime will eliminate stimulants that may be interfering with sleep. Eliminating alcohol or nicotine for at least 2 hours before bedtime can also help the patient get to sleep and stay asleep. Encourage the patient to exercise regularly, but not immediately before bedtime. Patients should try to establish a routine time for going to bed and getting up, and avoid taking naps during the day. Going to bed hungry or overly full can interfere with sleep. Reading in bed should be avoided.

Sleep experts agree that the bedroom should be a refuge, with the bed used for sleep and for sexual relations. Reading, watching television, and discussing the day’s problems in bed are all disruptive to the sleep cycle. Many advise that when sleep does not come within 30 minutes, the individual should get up, go into another room, and read or engage in some restful activity until the feeling of sleepiness returns. It is also important that the room be at a comfortable temperature, and the mattress comfortable and properly supportive.

Patients in a health care facility are especially prone to environmental disruptions. The use of earplugs or a “white noise” machine may help block out noise. Many patients will sleep better if they have a favorite pillow or blanket from home. Take care to avoid waking patients unless absolutely necessary. Procedures such as vital signs and dressing changes should be scheduled together to avoid waking a patient repeatedly. If possible, close the patient’s room door, and avoid talking in the hallway during the night hours.

Medication such as sedatives and hypnotics are sometimes prescribed to promote sleep. These should be used only for short-term relief. Over-the-counter sleep medications often contain antihistamines that induce drowsiness. If using medications, the patient should take the dose early enough to allow time for absorption before bedtime. Patients should be instructed about potential side effects of any medications.

NCLEX-PN® EXAMINATION–STYLE REVIEW QUESTIONS

Choose the best answer(s) for each question.

1. There are several nonpharmacologic interventions for pain. The one that uses a machine to measure learned responses is ________________________________. (Fill in the blank.)

2. Endorphins modulate pain by:

1. acting on small-diameter nerve fibers.

2. acting on large-diameter nerve fibers.

3. Your patient, a 27-year-old computer programmer, is suffering pain in her right ankle due to a fracture received in a skiing accident. This type of pain would be considered:

4. Intramuscular injections of pain medication may be contraindicated in patients:

1. who have large, well-developed muscles.

2. who require long-term pain management.

5. When monitoring the patient for responses to opioid medication administered via an epidural catheter, the nurse knows that complications may include: (Select all that apply.)

6. Epidural analgesia is used:

7. A 55-year-old patient is receiving analgesia postoperatively via a PCA pump. He expresses concern about accidentally overdosing himself. Appropriate information to give the patient includes: (Select the two best responses.)

1. “Even though I am not giving you the medication, I do assess your tolerance of the ordered dose at regular intervals.”

2. “The doctor doesn’t order enough medication that you would be able to overdose.”

3. “I can ask the doctor to adjust your medication if you are worried.”

4. “The PCA has a lockout mechanism that prevents you from giving yourself too much medication.”

8. Patients for whom warm packs carry an increased risk of skin damage include: (Select all that apply.)

9. Factors that can adversely affect sleep include: (Select all that apply.)

1. consistent nighttime routines.

2. alcohol consumption near bedtime.

10. Patients should be advised that medications to promote sleep should be: (Select all that apply.)

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES ? Read each clinical scenario and discuss the questions with your classmates.

Patients in a hospital or long-term care facility may wake up in the middle of the night and find it difficult to go back to sleep. What interventions might the nurse provide to assist the patient to return to sleep?

Scenario B

What helps you go to sleep? Compare your notes with those of other students. What techniques identified could be used to assist a patient?