Orthodontic diagnosis and treatment in the mixed dentition

John Fricker, Om P Kharbanda and Julia Dando

Introduction

The primary aim of orthodontic assessment in a growing child is to differentiate between a developing normal occlusion and a potential malocclusion, including any abnormal growth of the face and function of the stomatognathic system. It is essential to have a sound understanding of facial growth and dental development, and the ability to recognize the rate and direction of facial and dental growth. Many situations of apparent malocclusion in the mixed dentition are actually manifestation of the normal process of dental and facial development. Minor incisor irregularities, spacing and ectopic eruption of teeth, which may show up during the mixed dentition, could self-correct with growth and development.

Correction of dental arch irregularities, occlusal and jaw relation abnormalities and elimination of functional interferences may be classified as preventive or interceptive. The term ‘preventive orthodontics’ implies steps undertaken for elimination of factors that may lead to malocclusion in an otherwise normally developing dentition.

‘Interceptive orthodontics’ implies that corrective measures may be necessary to intercept a potential irregularity from progressing into a more severe malocclusion. Neither the appliances used nor the treatment itself should interfere with the often rapid changes in eruption of permanent teeth and the dynamic nature of occlusal adjustment. It is important to understand that even when such procedures are carried out, a majority of these children will go on to require some further treatment in the permanent dentition.

Orthodontic assessment of a child

An orthodontic assessment in common with other specialties, must include a good history, a thorough clinical examination and any relevant investigations. The information gathered leads to a diagnosis, which in turn allows treatment planning. This topic is covered in detail in Chapter 1. Additional points relevant to aid orthodontic diagnosis, however, will now be discussed.

The child should be assessed for skeletal and dental problems and abnormalities of functions of the stomatognathic system. Clinical assessment is performed in all the three dimensions of space, i.e. vertical, anteroposterior and transverse.

Skeletal classification

This describes the anteroposterior relationship between the maxilla and mandible relative to the cranial base:

• Skeletal Class I – the maxilla and mandible are in a normal relationship (orthognathic).

• Skeletal Class II – the mandible appears small relative to the maxilla (retrognathic). This could be due to: a small mandible, a large maxilla or a combination of both.

• Skeletal Class III – the mandible appears larger than the maxilla (prognathic). This could be due to: a large mandible, a small maxilla or a combination of both.

• Vertical assessment includes low or increased facial heights, while transverse assessment should evaluate a narrow or wide maxilla or mandible.

Dental relationships

Dental relationships are recorded with the teeth in occlusion. It describes the anteroposterior relationship of the upper and lower molars according to Angle’s classification and the anteroposterior incisor relationship according to the British Standards Institute classification (1983). Angle’s classification of malocclusion is based on the relationship of the upper and lower first permanent molars.

Molar relationship (Figure 14.1)

• Class I implies a normal anteroposterior relationship with the mesial cusp of the upper first permanent molar occluding with the fossa of the lower first permanent molar.

• Class II molar relationship implies disto-occlusion of the lower first permanent molar with the upper first permanent molar and is a reflection of a retrognathic skeletal pattern with increased over jet.

• Class III molar relationship implies a mesially positioned lower first permanent molar and is a reflection of a prognathic mandible and anterior cross-bite.

Figure 14.1 Orthodontic molar relationships: (A) Class I – normal occlusion. The mesio-buccal cusp of the upper first permanent molar occludes between the mesial and distal cusps of the lower first permanent molar. (B) Class II – disto-occlusion. The lower first permanent molar is distal to the upper tooth. (C) Class III – mesio-occlusion. The lower first permanent molar is mesial to the upper molar.

Incisor relationship (Figure 14.2)

• Class II Division 1 (proclined upper incisors).

• Class II Division 2 (retroclined upper incisors).

• Class III cross-bite of the anterior segment or negative over jet.

Vertical assessment includes normal or abnormal vertical overlap of the incisors, i.e. normal, deep or open bite. Transverse assessment should include any cross-bite or scissors-bite of the buccal segments of the dental arches.

Figure 14.2 Orthodontic incisor relationships. (A) Class I – normal occlusion. The incisors. (B) Class II Division 1: The incisors are protruded and there is an excessive overjet. Class II Division 2: The upper central incisors are retroclined, while the upper lateral incisors are protruded. Furthermore, there is an excessive overbite. (C) Class III: An anterior cross-bite is present.

Complicating factors in any malocclusion

These include:

Intra-arch problems (Figure 14.3)

Orthodontic examination

Extra-oral

The physical status of the child should be included here, and if relevant, height and weight should be recorded on a standard growth chart. It is essential to determine if the face of the child is also growing normally. The face is examined with the child sitting upright. This is important because the mandibular rest position will change, if lying back.

Frontal view

• Shape of face – long and thin/normal/short and square.

• Symmetry – initial assessment from the front. Looking at the child from above and behind will confirm asymmetry. It is important to look at the position of the chin at rest and in occlusion. A deviation would suggest a functional shift is occurring rather than a true asymmetry.

• Facial proportions – viewed from the front, the face can be divided vertically into equal thirds. The height of the midface (supraorbital ridge to base of nose) should, therefore, equal that of the lower face (base of nose to chin). However, it may be increased or decreased.

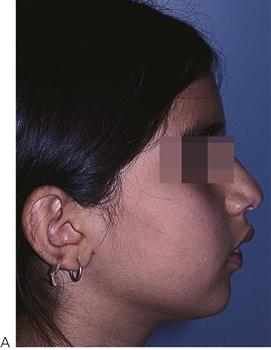

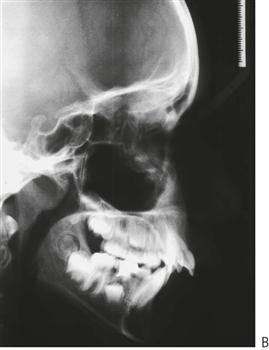

Lateral view (Figure 14.4)

• Profile – convex/straight/concave.

• Skeletal pattern – Class I, II, III.

• Nose – small/normal/prominent.

• Chin – recessive/normal/prominent.

• Nasolabial angle – acute/normal/obtuse. If the angle is obtuse, orthodontic treatment involving the extraction of permanent teeth will have a detrimental effect on the profile.

• Lip position – competent (closed), incompetent (apart).

• Labiomental sulcus – normal/deep.

• FMPA – imagine a line connecting the ear to the eye (Frankfort horizontal) and construct an angle with the lower border of the mandible. This angle (FMPA) will help to assess growth direction.

• Extreme types are vertical growers (with FMA angle >32°) and horizontal growers (with FMA angle of <20°). Growth direction is an important consideration in treatment planning (Figure 14.5).

Intra-oral

A record should be made of:

• Number of teeth present radiographically and intra-orally.

• Tooth quality and any existing restorations or active caries.

• Level of oral hygiene and assessment of gingival health.

• Assessment of crowding/spacing in both arches.

• Overjet, overbite, canine and molar relationships.

• Anterior or posterior cross-bites and any associated functional shift into occlusion.

• Dental centre lines in relation to each other (upper to lower).

• In relation to the facial midline (upper to face and lower to face).

• Condition of the oral soft tissues

• Abnormal frenal attachments. Thick upper labial frenum can be associated with median diastema. Tongue tie can be associated with articulation problems.

• Any other pathology such as an epulis.

• Tongue position: at rest and during swallowing.

• Speech articulation problems (see Chapter 15).

It is important to identify any deviation of the mandible during opening and closing into full intercuspal occlusion. Often the underlying cause is interference from an erupting tooth leading to either functional forward or lateral shift that demands early treatment to restore the balance in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ).

Investigations

These are determined by the findings at examination.

• Panoramic radiograph – will give an overall picture of the developing dentition and jaws. It is the standard radiograph used in orthodontic assessment. Additional films may be needed to allow a more detailed analysis of suspected pathology.

• Lateral cephalogram – this is useful to assess skeletal discrepancy when treatment is to be started. Tracing of the film and subsequent cephalometric analysis will aid diagnosis and treatment planning. This film can also be used as a baseline to monitor future growth.

• Posteroanterior (PA) cephalogram – for transverse discrepancies or asymmetry.

• Anterior occlusal films – only for location of impacted canines, supernumeraries, or ectopic teeth.

• 3-dimensional CT may be required for evaluation of exact location of impacted or supernumerary teeth that are otherwise difficult to locate with standard 2D radiographs. Cone beam CT (CBCT) is becoming increasingly popular, since radiation doses are much less than CT (see Chapter 11).

• Study models are essential baseline records that are also used in treatment planning and space analyses.

Evaluation of crowding

In the permanent dentition, it is easy to assess the amount of crowding by taking measurements directly from study models. Treatment will depend on the severity of the problem and may involve arch lengthening or extractions. In the mixed dentition, however, a prediction of future crowding is necessary.

Mixed dentition analysis

The purpose of a mixed dentition analysis is to determine the space available in the dental arch for the permanent successors to erupt. To complete this analysis, it is necessary to first record the arch length and the mesiodistal widths of the mandibular permanent incisors.

Measurement of arch length

The conventional way to determine arch length is to measure directly from a set of study casts. Soft brass wire can be adapted from the mesial of the first permanent molar to follow the arch form around to the mesial of the contralateral first molar. The wire should be shaped to the ideal arch form and not follow any teeth out of alignment. Once the arch length has been determined, it is then necessary to estimate the space required for the permanent successors. Mesiodistal dimensions of erupted teeth up to second premolars can be obtained directly from a study cast. Unerupted teeth can be measured by one of two methods:

Both methods are based on the high correlation between the crown measurements of the permanent mandibular incisors and the combined sizes of two premolars and permanent canines. Thus, it is possible to forecast the amount of space required for the unerupted teeth and to plan interceptive and/or preventive space management requirements.

The difference in values between arch length and tooth size will indicate the amount of crowding or spacing present.

Summary

At the end of diagnosis, a clinician should have gathered the following information:

• Growth pattern – normal, Class I, Class II, Class III.

• Growth trend – horizontal, vertical.

• Sequence and stage of eruption of teeth.

• Number of teeth missing or supernumeraries.

• The dental arch relations – cross-bites.

• Amount of crowding and spacing.

• Digit sucking/thumb sucking habit.

• Pattern of respiration, i.e. normal breathing or mouth breathing.

• Is the child likely to grow normally or would he/she benefit from orthodontic intervention?

Crowding and space management in the mixed dentition

Space management can minimize the development of crowding in the permanent dentition. It essentially involves:

• Space maintenance following the premature loss of primary molars.

• Utilization of the leeway space by placement of holding arches.

Space maintenance

The best space maintenance treatment is the preservation of the primary molars until natural exfoliation. Although dental health education and improved caries prevention have lowered the number of children who develop malocclusion because of premature loss of primary teeth, it is still one of the most common controllable causes of malocclusion.

When a primary second molar is lost prematurely due to caries or to the ectopic eruption of the first permanent molar, the first permanent molar will drift mesially. This is most pronounced in the maxilla with a more rapid shift of the molar and causing a Class II malocclusion. The earlier the loss of the second primary molar and the less the root development of the permanent molar, the greater will be the amount of bodily mesial shift of the permanent molar.

Factors to consider for placement of space maintainers

Placement of a space maintainer requires care of the appliance and oral hygiene maintenance. A child with poor oral hygiene and high caries risk is not the ideal case for such appliance therapy. Before a decision is made to provide a space maintainer, it is often essential to critically evaluate its merits, the need and the benefit it would provide to the development of normal occlusion.

Posterior teeth

• Whenever a primary second molar is lost prematurely, whether before or after the eruption of the first permanent molar, there will be some loss of arch length caused by the mesial drift of the permanent molar.

• Space maintenance is critical in children who have a normal arch length and lose a primary molar. Any loss of space in these children will result in crowding of the permanent teeth.

• Where space has already been lost, it is necessary to regain space and then fit a space maintainer.

Types of space maintainer

Removable

Removable space maintainers have shortcomings similar to all removable appliances:

A removable space maintainer that is only worn at night is often sufficient to hold space and prevent the mesial drift of permanent molars. Night-only wearing of the appliance also reduces the risk of loss or breakage by the patient. The appliance should be washed and inserted in place before going to bed, then removed, washed and placed in a safe place when not worn. Hawley’s appliance is a typical example.

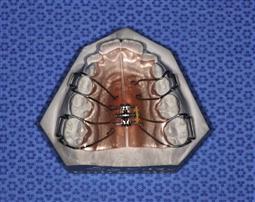

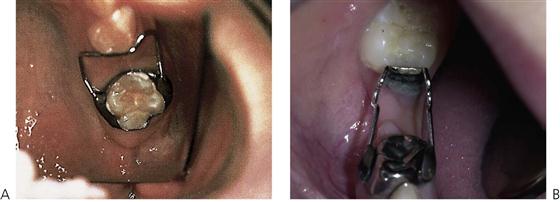

Fixed space maintainers (Figure 14.6)

• Fixed appliances have the advantage that they are worn continuously and do not require patient cooperation in wearing them.

• It should be noted that the placement of a fixed appliance in a child at high risk of caries may compromise those teeth which are banded as well as adjacent teeth.

• Band and loop appliance is typically used in cases of unilateral loss.

• Nance appliance or lingual arch can be used if the loss is bilateral.

Figure 14.6 (A) A band and loop space maintainer. The placement of a space maintainer must not compromise the permanent tooth. Bands should be cemented with a luting glass ionomer as a protection against caries and the appliance reviewed regularly. As the premolar erupts, the appliance is removed when there is interference with normal emergence. (B) A distal shoe space maintainer is placed following early loss of the second primary molar prior to the eruption of the first permanent molar. It prevents mesial migration of the permanent tooth.

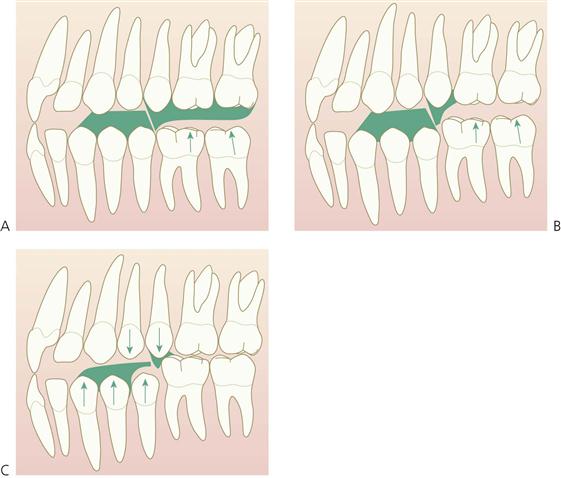

Regaining space

Within an arch, space may need to be regained when migration of permanent teeth has already occurred following the loss of adjacent deciduous teeth (Figure 14.7). Furthermore, space maintenance would then be needed until the permanent successor erupted. In the maxilla, this would intercept a developing Class II, dental relationship secondary to mesial migration and rotation of the first permanent molar. In the mandible, it could prevent a mild dental Class III relationship by uprighting tipped lower first permanent molars. In individuals with a developing skeletal discrepancy, the dental correction would have no effect on the underlying skeletal problem.

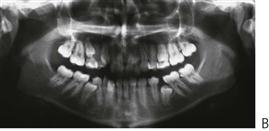

Figure 14.7 The failure to place space maintainers following bilateral loss of primary second molars has resulted in forward movement of the first permanent molars thereby reducing the available space for the second premolars. (A) More space tends to be lost in the upper arch than in the lower arch following loss of the second primary molars (B).

In general, tooth movement is slower in cases with severe horizontal growth pattern (low FMPA). Conversely, it is rapid in vertical growers, and space loss can occur very quickly. Early fitting of a space maintainer will prevent space loss. If space is to be regained, it is essential that the mechanics should not extrude the teeth at all.

Radiographs and study models are essential aids in assessing space needs. It is important to note whether teeth have moved bodily or have tipped into the space. Tipping can be easier to resolve than bodily tooth movement. Radiographic examination should also locate the permanent second molars and establish space available for distalization of the first permanent molars.

Appliances used to regain space

• Removable appliances – Acrylic cervical occipital appliance (ACCO appliance).

An ACCO appliance (Figure 14.8) is comprised of a palatal acrylic plate with an anterior bite platform to disclude the posterior teeth, allowing the first permanent molar to move freely. Retention is obtained via Adams clasps on the first premolars or deciduous molars and a labial bow across the permanent incisors. The bow should be supported with a band of acrylic across the labial surfaces of the incisors to increase the anchorage for the finger springs against the mesial surface of the molars to be distalized. These are most successful in the maxillary arch, where there is a dental and skeletal Class I pattern with normal vertical proportions and the regaining of space is by way of uprighting the first permanent molar.

Figure 14.8 (A–C) The ACCO appliance is used for uprighting maxillary permanent molars to regain space. To maximize anchorage, acrylic is flowed over the labial arch wire and this limits the proclination of incisors as the molars are distalized.

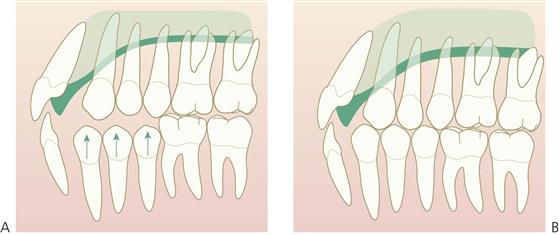

Timed extraction of teeth to resolve intra-arch crowding

The total amount of arch length deficiency is the key to planning of timed extractions. For this to be beneficial, a cephalometric analysis should show the child to be growing within a normal pattern and that all the permanent teeth are present radiographically and in the normal order of eruption.

Extraction of deciduous canines

• Premature loss of a primary canine as the permanent lateral incisor erupts will result in a midline shift to the same side. Extraction of the contralateral deciduous canine will help prevent a shift occurring.

• In cases with crowding, the loss of primary canines should be managed by placement of a fixed lingual arch to support the incisors and prevent lingual tipping as the midlines correct themselves.

• As the permanent canines erupt, it may be necessary to reduce some part of crown at the mesial of the primary first molars and then, as the first premolars erupt, reduce the mesial of the second primary molars.

Serial extraction

The purpose of serial extraction is to encourage the early eruption of the first premolars ahead of the permanent canines and should only be considered where there is an arch discrepancy of >4 mm. Serial extraction is usually limited to the upper arch as serial extractions in the lower arch usually results in lingual collapse of the lower anterior segment.

Contraindications

Serial extraction should not be performed in the following circumstances:

Treatment stages in serial extraction

• First, the primary canines are removed to allow spontaneous alignment of the permanent incisors.

• The primary first molars are removed to allow the eruption of the first premolars.

• Once the first premolars are erupted, they are removed and a space maintainer is issued to allow the permanent canines to erupt.

• Further orthodontic treatment is usually required to align teeth to achieve correct root angulation and incisor torque.

Thus, serial extraction is a planned procedure that demands a minimum of 5 years’ supervision by the dentist of the developing occlusion. Without such a commitment, the objectives will not be fully achieved and at times, the child is then left with a more severe malocclusion.

Spacing

Spaces in the deciduous dentition are normal and such spacing indicates an increased chance of good alignment in the permanent dentition. During the early mixed dentition stage, physiological spacing is common in the anterior region with the incisors appearing splayed. As the permanent canines erupt, this will resolve spontaneously and early treatment should not be contemplated.

Dentoalveolar disproportion and tooth size discrepancies can also lead to spacing. Definitive treatment should be delayed until the permanent dentition, when options for space closure through orthodontics or tooth build-ups are available. If ‘cosmetics’ is a concern in the mixed dentition, then crown build-ups of the permanent incisors as a temporary solution, should be considered.

Unusually large spaces may be caused by an enlarged tongue. Isolated true macroglossia is not common and is usually only associated with Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. If tongue size is suspected to be enlarged, secondary causes such as increased secretion of growth hormone may also need to be investigated by a paediatrician.

Dentoalveolar disproportion and tooth size discrepancies can also lead to spacing. Definitive treatment is carried out in the permanent dentition, when space closure or tooth build-ups should be considered.

Hypodontia is the term used to describe the congenital absence of one or more teeth. These teeth have not developed from the initiation stage of tooth development (see Chapter 11).

Diagnosis

An understanding of the normal sequence and average age of eruption of permanent teeth will alert the practitioner to the possibility of congenital absence of a tooth or teeth. Any delay in the normal eruption time of permanent teeth or exfoliation of primary teeth should be investigated radiographically. The orthopantomogram (OPG) panoramic radiograph provides a good view for premolars and molars but is often unclear in the incisor region because of the narrow focal trough. It may be necessary to supplement this with either periapical films or, in the maxilla, an anterior occlusal film.

For most children, a radiographic survey at age 7 years will demonstrate the presence or absence of all permanent teeth, except for third molars. It should be noted, however, that there is a large variation, especially in the second premolar region. Third molars are generally not radiographically visible before the age of 9 years. A radiograph will show the tooth follicle before calcification begins, and there is a range in development time between the presentation of the follicle and calcification commencing, especially for second premolars.

Management

Where a permanent tooth is diagnosed as congenitally absent, there are two choices in management:

The preferred treatment choice will depend on the severity of the condition (number of absent teeth), location of the missing teeth and the underlying skeletal pattern.

Class I patterns

The jaw relationship is normal. If the missing tooth is located in the posterior segments, space closure is often the treatment of choice. Occlusal relationships, however, will dictate the decision. On the other hand, if one or more lateral incisors are missing, the choices are to close spaces and substitute permanent canines for the absent laterals or open the spaces and fire the roots of the adjacent teeth in preparation for implant replacement. Planning such treatment is age-dependent as implants are not indicated until the patient is at least 22 years of age. Opening spaces in preparation for implants as a teenager will require long-term retention of the spaces and root angulations and often will require further orthodontics just prior to the placements of implants due to growth factors.

Class II patterns

This malocclusion is characterized by a smaller mandible with an increased overjet. The preferred option for missing teeth in the maxilla, is to close space and reduce the overjet at the same time. The permanent canines can replace lateral incisors, but size, shape and colour must be considered. Restorative techniques using resin veneers and acid-etch can be used to reshape the canines as lateral incisors, restoring the anatomy of the substituted teeth and providing a balanced smile.

Class III patterns

The maxilla is proportionally smaller than the mandible and there can be a dental cross-bite either anteriorly or posteriorly. If teeth are missing in the lower arch, and the skeletal problem can be camouflaged with orthodontics only, it may be advantageous to close space. Conversely if teeth are missing in the maxilla, space opening and tooth replacement is the preferred option to avoid further constriction of the arch.

Tooth loss due to trauma

Traumatic loss of a maxillary incisor can be treated orthodontically within the same guidelines as those for congenital absence of teeth.

Orthodontic aspects of supernumerary teeth

Development and aetiology

Supernumerary teeth may be found in any part of the dental arch; however, the most frequent sites are in the regions of the maxillary midline and the third molars. Because the supernumerary teeth develop late, they are not often found in the primary dentition and when they do develop with the primary teeth, they usually erupt. Tubercular and inverted supernumerary teeth are most often unerupted, and they commonly delay or inhibit the eruption of the central incisors. Supernumerary teeth in the region of the lateral incisors, either in the primary or permanent dentition, usually erupt into the arch.

Orthodontic effects

Delay or failure of eruption

The failure of a permanent tooth to erupt leads to malocclusion as adjacent teeth shift into the area that should be occupied by the permanent tooth. Moreover, the supernumerary tooth can be a cause of ectopic eruption of other teeth, producing a malocclusion. Supernumeraries can result in:

• Displacement of permanent teeth (Figure 14.9).

Figure 14.9 (A) Displacement of the upper left central incisor due to a midline tuberculate supernumerary lying in the palate (B).

Treatment planning

• If a supernumerary tooth is obstructing the eruption path of an adjacent tooth, or has any associated pathology, it should be removed as soon as convenient. However, with all dentoalveolar surgery, there are risks that need to be considered, such as nerve injury or damage to adjacent teeth and anaesthetic risk. In some cases, the risks will outweigh the benefits and it may be better to leave the supernumerary tooth in situ.

• A supernumerary primary incisor may be retained if there is sufficient room for it. The tooth should be extracted when the permanent lateral incisor is ready to erupt.

• If there is an extra permanent lateral incisor present with the primary supernumerary tooth, it may be removed at the same time. Usually, the more distal of the two permanent teeth is the supernumerary tooth.

• Identification of a supernumerary tooth that is similar in form and size to the adjacent tooth can be made by comparing the teeth with those on the opposite side of the dental arch. The tooth that more closely resembles the size and shape the normal lateral incisor should be retained.

Extraction of over-retained primary teeth

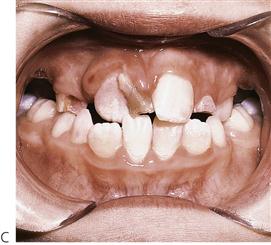

The earlier that one can recognize and remove over-retained primary teeth that may be causing ectopic eruption of a succedaneous tooth, the better the chance that a permanent tooth will erupt in a satisfactory position (Figure 14.10). The greatest damage that may result from over-retained primary teeth comes in the wake of ankylosed primary molars.

Figure 14.10 (A,B) Common presentations of anterior crowding. It is important to inform parents and children of where teeth will erupt. Lower permanent incisors form lingually to the primary teeth and in patients with tooth to base bone discrepancy, they will erupt behind the primaries. It is often wise to facilitate removal of such teeth, as in (B) and (C), to avoid the development of a cross-bite.

Diagnosis

The ankylosed primary molar may not be recognized in the very early stage (Figure 14.11). The condition can be readily diagnosed a short time later because the vertical level of the occlusal surface of the ankylosed tooth becomes noticeably lower than the level of adjacent teeth, and as time progresses, this difference in vertical level becomes more extreme.

Figure 14.11 An ankylosed lower second primary molar in infraocclusion. The tooth is subgingival and grossly carious. Uprighting of the first permanent molar is required initially, followed by surgical removal, and placement of a space maintainer.

Because ankylosed teeth seem to be submerging, they have been called ‘submerged’ teeth, but the term cannot be applied accurately to ankylosed teeth. The continued vertical eruption of the uninvolved adjacent teeth and the vertical growth of the alveolar process and periodontium create the illusion that the ankylosed tooth is submerging.

Management

• Ankylosed primary molars may be retained as long as they are maintaining arch length (i.e. preventing mesial shifting of the first permanent molars) or as long as they do not prevent the eruption of the succedaneous teeth.

• If there is evidence of root resorption, these teeth will eventually be lost normally and there is no indication for early removal.

• The union between the cementum and dentine of the tooth and the bone of the alveolar process is physically strong and removal may require a surgical procedure, depending on how far the tooth has been submerged.

• A space-maintaining appliance must be used if the primary tooth is removed before the imminent eruption of the succedaneous tooth.

An over-retained tooth often accounts for the ectopic eruption, or impaction, of the succedaneous tooth. Because the ankylosed tooth is ultimately unable to withstand the mesial shifting of the first molar and the loss of arch length, extraction of an ankylosed primary tooth is an effective means of interceptive-preventive orthodontics.

Ectopic eruption of permanent canines

The incidence of impacted canines in the maxilla is 2% and the majority lie in a palatal position. The anomaly can be associated with small or absent lateral incisors. In about 12% of cases with impacted canines, the lateral incisor root will undergo some resorption.

The normal age of eruption is 11 ± 2 years and the crown should certainly be palpable in the labial sulcus at 9–10 years of age. If the canine is not palpable, further investigation is indicated to check for impaction or ectopic eruption. Intra-oral radiographs taken at right angles to each other and the technique of parallax can be used to localize their position or alternatively an OPG panoramic film. Radiographic scans with cone beam CT are the best for localizing ectopic or impacted permanent canines as these provide a 3D position of the tooth (see Chapter 11).

Interceptive extraction of the deciduous canines can improve the position of the permanent teeth and the maximum improvement will be seen within 12 months (Ericson & Kurol 1988). The success of this approach is reduced, however, if the arch is already crowded (Power & Short 1993).

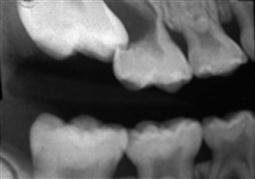

Ectopic eruption of first permanent molars (Figure 14.12)

This can be an indication of an inadequate arch length, and a radiographic survey is required to confirm the presence of premolar teeth. The permanent teeth may resorb the distal margins of the second primary molars; this is more common in the maxilla.

Figure 14.12 Ectopic eruption of the first permanent molars, causing resorption of the primary teeth. In this position, it is unlikely that the first permanent molars will erupt and space loss has already occurred. The primary molars were extracted and a space-regaining appliance constructed.

Management

• Where there is impaction of the permanent molar against the distal of the second primary molar, slicing or discing of the distal surface of the primary molar will allow the spontaneous eruption of the permanent molar.

• Placement of orthodontic separators or brass ligature wire is usually difficult and uncomfortable, and has mixed success.

• Where the resorption of the primary molar is advanced, the loss of this tooth is indicated and space-regaining mechanics should be considered once the permanent molar has erupted (see above).

• Parents should be warned that further orthodontic treatment is usually required because of arch length deficiencies.

• Primary failure of eruption (PFE) is a rare condition that is characterized by non-syndromic eruption failure of permanent teeth in the absence of mechanical obstruction. It typically affects first molars and/or second molars. The molars do not erupt and also do not respond to orthodontic traction rather efforts to pull them leads to ankylosis. This condition can be familial.

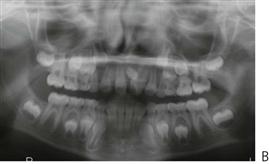

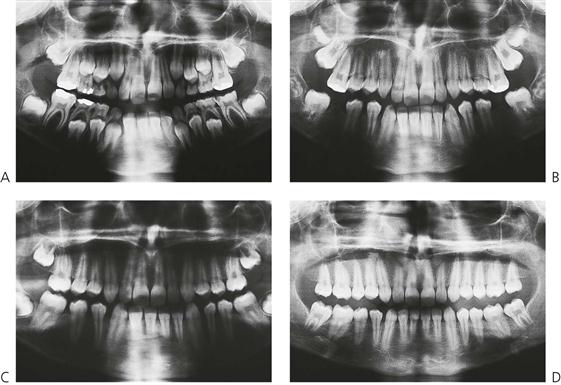

Extraction of first permanent molars (Figures 14.13, 14.14)

Gross caries involving the first permanent molars poses a difficult dilemma in treatment planning. The early presentation of the patient is essential in obtaining favourable results. The basic questions about whether these teeth should be removed or restored are:

• What is the long-term prognosis for the tooth?

• What is the status of the pulp?

Figure 14.13 Gross caries affecting the lower first permanent molars. Both teeth are non-vital and should be removed. This is a perfect time for extraction as the second molars will migrate mesially. The upper molars should be retained with a night-time removable appliance to prevent overeruption.

Figure 14.14 (A–D) Serial panoramic radiographs showing mesial migration of the second and third permanent molars following timed extraction of carious first permanent molars.

General considerations

• The decision to extract is often best made in conjunction with an orthodontist.

• If the tooth is not restorable no matter what the occlusion, then it should be removed. Even if successful root canal treatment can be completed, the status of the crown is most important. Commonly, these teeth have extensive loss of tooth structure, with only an enamel shell remaining.

• Non-vital immature teeth have a poor prognosis. Root canal treatment is usually not indicated in these teeth, especially as they would need an apexification procedure.

• If only the lower first permanent molars are removed, a removable appliance such as a Hawley should be used to prevent over eruption of the maxillary first permanent molars before the eruption of the lower second molars.

• The ideal time for lower first permanent molar extraction is before alveolar eruption of the second molar. These teeth will migrate mesially and assume the position of the first molar.

• If three molars are grossly carious and require removal, it is probably better to keep the extractions symmetrical and extract all four teeth.

• The presence or absence of third molars may influence a decision to extract the first molars, but ultimately, it will be the long-term prognosis of the first molars that determines the final treatment plan. The goal is to have a long-term, functional occlusion with minimum maintenance.

Orthodontic appliance systems

Basic requirements of orthodontic appliances

• Permit control of the amount, distribution, duration and direction of the force they exert.

• Be atraumatic to the oral tissues and not be adversely affected by oral secretions.

• Allow teeth and soft oral tissues to function normally.

• Allow wearer to maintain oral hygiene.

• Exert sufficient force or offer sufficient anchorage resistance to induce histological bone changes necessary for desired orthodontic tooth movement.

• Respond to the control of the operator.

• Allow movement of individual teeth or of groups of teeth in desirable directions.

Safety measures in fixed appliance treatment

Appliances should be regularly examined. Loose molar bands can result in caries due to failure of the cement lute, or cause trauma to the soft tissues because of excessive movement from biting forces. Archwires should be carefully fitted with the distal ends either cut as they leave the molar tube, or turned in. Failure to do this will result in irritation of the buccal mucosa.

Removable appliances

Although removable orthodontic appliances cannot produce all types of tooth movement, they possess several advantages. They are laboratory fabricated and hence require less chair time; are easily removed by the child/patient for oral hygiene and are often low cost. The conventional removable appliance is the Hawley appliance.

Design

Removable appliances should include:

Other design considerations

• For successful tooth/teeth movement to occur, the active components of the appliance should produce force in the desired direction whereas anchorage is derived from the acrylic plate that remains stationary.

• The acrylic plate should fit well against the palatal mucosa and must occupy the interdental spaces. The plate should be of even thickness, for strength and to house the retentive components and springs.

• The anchorage of the appliance is derived from palatal tissues, and from the teeth through the clasps.

• The posterior border of the maxillary appliance should be placed anterior to the junction of the hard and soft palate. It should be thin and gently merge with the palatal mucosa.

• The lower appliance should have smooth borders with sufficient relief to accommodate the functioning of the lingual frenum.

Springs

Spring design (finger, Z or retractors) should ensure adequate springiness and range of action while retaining strength.

| For lingual/palatal movement: | Labial bow/long labial bow |

| For labial movement: | Z spring or T spring |

| For mesial movement: | Finger spring |

| For distal movement: | Finger spring |

| For canine retraction: | Canine retractor – labial/palatal |

• The active arm of the spring should be in surface contact with the tooth to be moved.

• The point (area) of force application should be close to the cervical margin/gingival margin to minimize tipping.

• To increase the range of action, helices are incorporated into the spring design.

• Activate slowly, close to the gingival margins, without causing trauma to the oral tissues.

• There should be no hindrance/obstacle in the path of movement of teeth.

Labial bow

An active labial bow produces both horizontal and vertical force vectors resulting in palatal/lingual tooth movement and extrusion of tooth. It is used for retraction of proclined incisors. Since the labial bow causes tipping of the crown, simultaneous labial root tipping occurs.

Prerequisites for activating a labial bow are:

Anterior biteplanes

• The acrylic behind the upper incisors is thickened. In occlusion, there is contact of the lower incisors with the acrylic, with open bites in the buccal segments.

• In a growing child with a mild Class II tendency, bite opening may result in forward posturing of the mandible.

• Bite opening is a combination of supra-eruption of the mandibular molars and intrusion/stabilization of the vertical position of the mandibular incisors. Hence, a child with a normal or horizontal growth pattern is the most suitable case for bite opening.

• Children with vertical facial growth (that is, with a high FMPA) are not suitable cases for treatment with biteplanes. The biteplane will cause an open bite tendency to worsen, and have a detrimental effect on the profile.

• An active labial bow can be used to retract incisors after adequate bite opening, thus reducing an overjet.

• Biteplanes are also used to relieve interferences in the buccal segments, which may be hindering tooth movement.

Treatment of anterior cross-bites

Up to 10% of children present with cross-bites. Three types of anterior cross-bite may present in the mixed dentition.

Ectopic incisors

An incisor may erupt ectopically either palatally in the maxilla or labially in the mandible to a cross-bite relationship in centric occlusion. This may occur in a child with a balanced skeletal relationship. Early treatment is necessary if there is a deviation on opening and/or closing or if there is a traumatic occlusion or periodontal concern.

Skeletal Class III malocclusion

Skeletal Class III malocclusions are associated with maxillary transverse and anteroposterior deficiency coupled with prognathic mandible. Patients who have a major component of maxillary deficiency and little vertical growing can be successfully treated by early orthopaedic interventions. These include rapid maxillary expansion, maxillary protraction and mandibular chin cup therapy. Class III patients require follow-up and interventions to the age of 20 or beyond, until completion of mandibular growth.

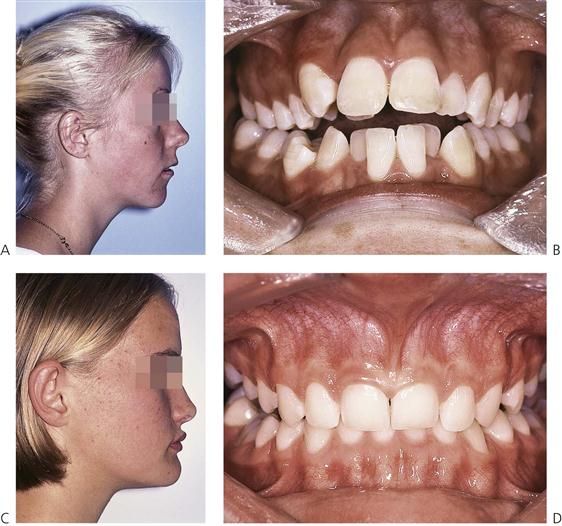

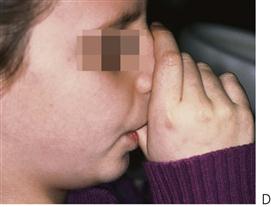

Pseudo Class III malocclusion (Figure 14.15)

This pattern occurs where there is a habitual mandibular closure pattern such that the mandible goes into a protrusive bite and thus cross-bite of incisors avoiding traumatic occlusion with lingual position of one or more maxillary incisors. Thus, anterior shift of the mandible can affect the growth of both the maxilla and the mandible with undesirable muscle adaptation. These cases are managed more simply as the primary movement required is to procline the maxillary incisors with a removable appliance or inclined plane until the patient is able to occlude comfortably into a retruded position.

Management

Tongue blade

If there is only one permanent incisor in cross-bite without an excessive overbite, a tongue blade, or paddle pop stick may be used to correct this. The stick is placed lingual to the upper tooth in cross-bite and the patient instructed to close firmly against the stick while it is held in position against the chin. The child should hold it there while biting against it and another person should count to 50 out loud, as in one apple, two apples, etc., for approximately 1 minute. Repeat this six times per day with an interval of at least half an hour. Correction is often complete within a few days.

Inclined planes

Where there is a functional shift of the mandible into an anterior cross-bite, an acrylic inclined plane can be fitted to the lower incisors to restrict the forward posturing and place pressure on the palatal of the maxillary incisors to push them labially. Alternatively, a composite build-up of the lower incisors will mimic the action of an incline plane. (It is preferable to choose a shade of composite resin that is easily distinguished from normal tooth structure to facilitate safe removal).

Treatment is usually complete within a few weeks. This appliance works best where there is a slight increase in overbite, which helps to retain the incisors in positive overjet once the appliance is removed.

Removable appliances (Figure 14.16)

• These appliances should only be used to correct cross-bites of dental origin.

• A modified Hawley appliance can be used in the maxilla to correct one or two teeth in cross-bite.

• Ensure there is adequate space to move the teeth into the desired position and movement will occur rapidly.

• Occlusal surfaces of both the primary and permanent molars should be covered to open the bite and allow free labial movement of the teeth in cross-bite.

• Adams’ clasps are placed on the first permanent molars.

• If the primary molars are present, ball-ended clasps can be fabricated to engage the interproximal areas of these teeth.

Where a single tooth is in cross-bite, a Z-spring placed palatally to the malposed tooth can be used, or if both central incisors are in cross-bite, two springs can be used to provide sweep arms on the palatal surface. Initially, the appliance should be fitted and checked for comfort with the springs passive. The springs are then activated 1–2 mm at a time. The patient is reviewed after 4 weeks to reactivate the springs as required and to check the retention of the appliance.

Figure 14.16 (A) Anterior dental cross-bite involving tooth 11. (B) An upper removable appliance can be used to correct these malocclusions utilizing Adams’ cribs on the first permanent and primary molars and two Z-springs. The Z-springs are activated approximately 2 mm to procline the incisor. Normally, the cross-bite should be corrected within 4 weeks and is often self-retaining dependent on the amount of overbite.

As with all removable appliances, the success of treatment is reliant on cooperation and compliance. If these qualities can be encouraged and the patient takes responsibility for the wearing of the appliance, treatment will progress satisfactorily. Occasionally, the cross-bite may also be due to a labially placed lower incisor. This must also be corrected, but is dependent on available space. If this is not available, definitive treatment may need to be delayed.

Treatment of posterior cross-bites

A posterior cross-bite is an abnormal, buccolingual relationship of a tooth or teeth when the two dental arches are brought into centric occlusion. There are two types of posterior cross-bite:

Dentoalveolar

Insufficient arch length or prolonged retention of deciduous teeth can deflect teeth during eruption and produce a cross-bite. Prolonged digit sucking can also cause palatal tilting of teeth and narrowing of the maxillary arch.

Skeletal

A skeletal cross-bite is related to size discrepancy between the maxilla and mandible. This could be a narrow maxilla, a wide mandible, or a combination of both. It is possible that both dental and skeletal causes may contribute to cross-bites of variable severity.

Management

• In children with a normally growing mandible, posterior cross-bites should be treated as early as possible to allow normal growth and development of the dental arches and temporomandibular joints. When planning treatment it is important to determine whether the cross-bite is unilateral or bilateral.

• The majority of cross-bites are bilateral but often present as unilateral when the teeth are in full intercuspal position. In these cases, the dental midlines will not be coincident on closing and there will be a deviation of the mandible towards one side at the end on closing.

• When the teeth are closed with the dental midlines coinciding, the posterior segments will be in an edge-to-edge, buccolingual position, reflecting the overall constriction of the maxillary dental arch, and bilateral maxillary expansion is indicated.

Cross-elastics

• When only a single molar is in cross-bite, this can often be corrected with a bonded attachment, button or hook, to the palatal of the maxillary and buccal of the lower molar.

• An elastic is stretched between these teeth; it is worn 24 h per day and changed every time it breaks (which is often).

• Cross-bites will normally correct within 3–4 months with continuous wearing of the elastic. The major change will be reflected in the position of the maxillary molar because of the cancellous nature of the maxillary alveolar bone as against the denser bone around the mandibular molar.

Removable appliances

• Lateral maxillary expansion can be achieved with a parallel expansion screw that is housed in the upper acrylic plate (Figure 14.17).

• To ensure delivery of sufficient force on the teeth and palate, the appliance should have excellent tissue contact and anchorage with clasps on teeth.

• Provide acrylic relief palatal to anterior teeth.

• The labial bow should be passive. When expansion occurs the bow becomes activated.

• The majority of the expansion appliances have a pitch of 1 mm. A full turn is achieved with four turns of the key.

• The conventional expansion schedule is one-quarter turn per week.

• Expansion appliances with posterior occlusal coverage work faster as they disclude the buccal occlusion.

It is extremely difficult to achieve unilateral expansion. A jackscrew offset in the palate will move one or two teeth, but there will usually be some expansion on the contralateral side. Always expand beyond the correction of the cross-bite and retain, because relapse potential is high. It is important to remember that correction is dental only, as the major component of tooth movement is tipping.

Fixed appliances

Slow maxillary expansion – quad helix/nickel titanium expanders

• A quad helix (Figure 14.18) is attached to the palatal surfaces of the cemented first molar bands. This may be hard soldered or removable via palatal tubes welded to the molar bands before cementation.

Figure 14.18 A quad helix appliance is used to correct posterior cross-bites in the mixed dentition. These appliances are simple to construct, are well tolerated by the patient and are efficient. They have the advantage that they are fixed and will also act as retainers once the malocclusion is corrected.

• The activation of this appliance is controlled by the dentist. This can be done intra-orally using pliers to open the individual helices or by removal of the appliance which is then expanded by hand. The quad helix is activated every 4 weeks and the appliance should be removed every 3 months for extra-oral activation and checking for loose bands or incipient caries.

• The expansion should continue until the molars are overcorrected, then retained with the same appliance for a further 3 months. The cross-bite is usually corrected within 4–6 months.

• The quad helix can be used simultaneously with full bonded appliance treatment.

• Thermal nickel titanium expanders require less adjustment than conventional stainless steel. Quad helix appliances provide a pre-determined amount of expansion. Cooling the expander softens the wire and allows it to be constricted and inserted into lingual tubes on the maxillary molars. As it warms to body temperature, it becomes springy and exerts continuous force on the teeth, thereby causing arch expansion.

• The expanding forces also cause simultaneous derotation of the molars.

Rapid expansion – Hyrax screw (Figure 14.19)

• Rapid maxillary expansion (RME) is indicated for severe cases of bilateral cross-bite, in which correction requires skeletal expansion. It involves the splitting of the midpalatal suture producing an orthopaedic increase in maxillary width. This can occur in a growing child, preferably before the age of 9 years. The split is evident on an occlusal radiograph, being widest at the incisors.

• The appliance uses a midpalatal screw (Hyrax) soldered to bands on the first permanent molars and the primary molars or premolars. In contrast with the removable appliance, the screw is activated a quarter turn twice each day and the patient should be monitored once a week.

• As the expansion proceeds, a diastema will show between the central incisors. This will close as the overstretched supragingival trans-septal fibres relapse. The parents and patients should be warned of this. As with any expansion technique, the cross-bite should be overcorrected and retained in this position for at least 3 months with the same appliance.

Deleterious oral habits

Digit sucking

One of the most common oral activities of the infant and young child is thumb and finger sucking (Figure 14.20). Sucking habits are perfectly normal in infancy. The infant will suck on any object brought into contact with the lips. This reflex behaviour may last for several years. It is an adaptive reflex common to mammals. Because it is a normal activity, thumb and finger sucking may be ignored in infancy. Thumb or finger sucking that is discontinued by age 2–3 years produces no permanent malformation of the jaws or displacement of the teeth. Continued beyond the time that the permanent incisor teeth erupt, it is almost always a factor in producing malocclusion in the anterior portion of the mouth.

Figure 14.20 (A) An anterior open bite in the primary dentition caused by a dummy-sucking habit. Even a malocclusion of this size will improve once the habit has stopped and requires no active treatment. Note that the anterior teeth have been restored, due to early childhood caries associated with the dummy and a bottle at night. (B) Lateral open bite caused by use of a pacifier. (C) Position of a thumb exerting orthopaedic as well as orthodontic forces. (D) Note the abnormal activity of the perioral musculature due to thumb sucking. (E) Resultant proclination of the upper anterior teeth, anterior open bite and abnormal tongue position in the mixed dentition. (F) Tongue guard appliance incorporating a mid-palatal screw expander.

The majority of older children who continue thumb sucking have what is termed an ‘empty’ habit. It is just something they have always done. These children are usually receptive to reasons why they should stop and many actually want to give up. A minority, however (especially if the habit has restarted) may have underlying social or psychological problems and these should be investigated.

Malocclusion from digit sucking

• Proclination and protrusion of the upper incisor teeth.

• The lower incisors may or may not be displaced lingually by the abnormal sucking habit.

• Posterior cross-bite due to over activity of buccinator compressing the maxilla.

• Anterior open bite (Figure 14.20A).

• Tendency for the tongue to perpetuate open bite with anterior tongue thrust. Proclined maxillary incisors and an anterior open bite favour the forward positioning of the tongue.

Control of digit sucking

Chemical means

Chemical therapy employs either hot-tasting, bitter-flavoured preparations or distasteful agents that are applied to the fingers or thumbs. Such things as cayenne pepper, quinine and asafoetida have been used to make the thumb or fingers so distasteful that the child will keep them out of his or her mouth. These preparations are effective with a limited number of children, and only when the habit is not firmly entrenched.

Mechanical means

• A simple device for controlling thumb or finger sucking is the application of adhesive tape to the thumb or finger. In many instances, this changes the character of the finger sufficiently to call the child’s attention to the fact that it is being placed in the mouth.

• A Hawley appliance with a palatal bar may be fitted as a habit reminder. This is important because in many instances thumb- and finger-sucking habits are at the subconscious level of the individual’s attention. Even though there may be some desire on the part of the child to discontinue the act, they may find it difficult to do so unless made aware of when they are doing it.

• A fixed appliance consisting of bands on the first molars and an anterior tongue crib will ensure compliance, as the child cannot remove it (Figure 14.20F).

• Often the child will respond to simple encouragement and explanation of the effect of digit-sucking on the teeth. The child’s own desire to break the habit means they react positively to such encouragement.

• The critical time for the elimination of digit-sucking is as the permanent incisors erupt. This generally coincides with entry into school, where peer pressure can be a powerful inducement to discontinue the habit.

• Psychological assessment is often beneficial in older children.

Mouth breathing

Mouth breathing is often associated with recurrent throat infections and nasal blockade. Obstructive mouth breathing can also be associated with severe deviated nasal septum or adenoids. Mouth breathing habit results in vertical growth pattern of the face, narrow maxillary arch, dryness of mouth causing gingivitis around maxillary incisors proclined maxillary incisors and inability to close lips. These facial features have been called ‘adenoid facies’. Timely correction of cause can facilitate oral breathing, which can improve growth pattern of the face. Should the mouth-breathing patient be considered for orthodontics, it should be initiated only after appropriate consultation with an ENT surgeon.

Tongue thrusting

Infantile swallowing habits should change to mature swallowing patterns with the eruption of teeth and the establishment of the occlusion that helps to contain the tongue in the oral cavity lingual to the dental arches during swallowing. ‘Teeth-apart’ swallowing is called a tongue thrust that can lead to open bite. Tongue thrust habits can also be the outcome of clinical malocclusion such as skeletal open bite. Habit breaking appliances in the form of cribs/rakes and swallowing exercises can help restore normal swallowing. A persistent tongue thrust habit can also cause relapse of treated cases of malocclusion leading to spacing/open bite and may require orthognathic surgery to close the open bite.

Correction of developing Class II skeletal malocclusions

Developing Class II skeletal malocclusions may benefit by the use of functional appliances. Functional appliances are those that alter the abnormal functioning of orofacial musculature, thereby bringing about normalization of growth and occlusion (Figure 14.21).

• By using functional appliances, there is an expectation of changes in the facial skeleton by growth modification.

• The simplest functional appliance is the anterior biteplane that can reposition the mandible more anteriorly in a growing child.

• Functional appliances can be fixed or removable.

• Functional appliances can be classified as tooth-borne (active or passive) and tissue-borne, depending upon the structures from which they derive anchorage. All removable functional appliances are tooth-borne, except the Frankel appliance, which is tissue-borne.

• Functional appliances help posture the mandible forward. The degree/amount of vertical and sagittal repositioning may cause variable tissue (muscle) responses.

• Those appliances that displace the mandible within the freeway space are intended to stimulate muscle activity and are called myodynamic appliances.

• Others can cause displacement of the mandible beyond freeway space and rely on passive muscle tension, and are called myotonic appliances.

Figure 14.21 (A) An ideal case for treatment using a functional appliance: a child with a normal maxilla, a small mandible and a normal growth pattern. (B) Lateral cephalogram showing proclination of the upper incisors.

Indications and case selection for functional appliances

• A growing child preferably during or prior to peak pubertal growth spurt.

• Retrognathic small mandible.

• Horizontal or normal growth trends.

• Normal or low incisor mandibular plane angle.

• Maxillary incisors not placed forward but can be proclined.

• No or minimal crowding in the upper and lower anterior teeth.

Effects of functional appliances

• Regulate the function of the oral/perioral musculature such as abnormal swallowing and thereby promote normal development.

• Mandible is repositioned forward.

• Remodelling of the glenoid fossa takes place.

• Retraction of maxillary anterior teeth.

• Bite opening and levelling of deep curve of Spee takes place with supra-eruption of lower posterior teeth.

• Mesial movement of lower buccal teeth and restraint or distalization of upper buccal teeth.

• Increase in lower posterior face height.

• Proclination of the lower anterior teeth.

Clark’s twin block appliance

The twin block appliance is a two-piece functional appliance (Figure 14.22). The upper and lower blocks are made of acrylic and meet each other in the premolar region at an angle of about 70°. This is sufficient to maintain mandibular forward posturing. A child can speak, eat and live with the appliance in place. Being the only full-time functional appliance, it is expected to bring about rapid skeletal, dental and neuromuscular adaptations.

The upper twin block can house an expansion screw as well as springs for individual minor tooth/teeth movement. Hence, while mandibular repositioning is in progress, simultaneous expansion of the maxilla and alignment of minor tooth malpositions can take place, thereby eliminating the need for pre-functional phase treatment, resulting in an overall shorter treatment time.

The twin block appliance offers flexibility of use with fixed appliances that may be required for finishing and detailing in the second phase of occlusal settlement. Hence, the total treatment time could be even shorter.

Treatment sequence (Figures 14.23, 14.24)

1. Case selection and treatment planning

• Prepare complete records, i.e. study models, clinical photographs and X-rays.

• Phase out the need for any major pre-functional orthodontic treatment or the possibility of simultaneous tooth movement with active phase.

• Record bite – advance mandible to edge-to-edge position for bite registration.

• Appliance issue and follow-up.

• Acrylic trimming for selective eruption of teeth for bite opening and sagittal molar correction.

• The modified acrylic biteplate holds the mandible forward.

Instructions for patients wearing Clark’s twin block appliance

• The appliance should be worn 24 h/day, except when cleaning and sports, including swimming.

• The key to success is eating with the appliance, as this enhances the adaptation of the muscles and ligaments of the temporomandibular joints as the mandible is protrusion.

• The usual time of treatment is 12 months, and this is usually followed by a second phase of treatment to detail the interdigitation of the upper and lower teeth.

Summary

Orthodontic assessment of a child requires a careful and detailed clinical examination. A child whose growth is yet to be completed and whose dentition is in a state of flux with several teeth shedding or erupting, needs to be diagnosed as having a state of normal/potentially abnormal or abnormal occlusion. This may require additional diagnostic records to be made, including input from a specialist orthodontist.

Further reading

Crowding

1. Becker A, Kurnei-R’em RM. The effects of infra occlusion: Part I Tilting of the adjacent teeth and local space loss. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 1992;102:256–264.

2. Bolton WA. The clinical application of a tooth-size analysis. American Journal of Orthodontics. 1962;48:504–529.

3. Irwin RD, Herold JS, Richardson A. Mixed dentition analysis: a review of methods and their accuracy. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. 1995;5:137–142.

4. Moorres CFA, Chadha JM. Available space for the incisors during dental development: a growth study based on physiological age. Angle Orthodontist. 1965;35:12–22.

5. Papandreas SG, Buschang PH. Physiologic drift of the mandibular dentition following first premolar extractions. Angle Orthodontist. 1993;63:127–134.

6. Staley RN, Kerber PE. A revision of the Hixon and Oldfather mixed dentition prediction method. American Journal of Orthodontics. 1980;78:296–302.

7. Tanaka MM, Johnston LE. The prediction of the size of unerupted canines and premolars in a contemporary orthodontic population. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1974;88:798–801.

Space management

1. Brennan MM, Gianelly AA. The use of the lingual arch in the mixed dentition to resolve incisor crowding. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 2000;117:81–85.

2. Wright GW, Kennedy DB. Space control in the primary and mixed dentitions. Dental Clinics of North America. 1978;22:579–601.

Timed extraction

1. Dale J. Interceptive guidance of occlusion, with emphasis on diagnosis. In: Graber TM, Vanarsdall RL, eds. Orthodontics, current principles and techniques. second ed Philadelphia: Mosby; 1994.

2. Gianelly AA. Crowding: timing of treatment. Angle Orthodontist. 1994;64:415–418.

3. Jacobs S. A reassessment of serial extraction. Australian Orthodontic Journal. 1987;10:90–96.

4. Jacobs SG. Reducing the incidence of palatally impacted maxillary canines by extraction of deciduous canines A useful preventive/interceptive orthodontic procedure. Australian Dental Journal. 1992;37:6–11.

5. Little RM. The effects of eruption guidance and serial extraction on the developing dentition. Pediatric Dentistry. 1987;9:65–70.

6. Mackie IC, Blinkhorn AS, Davies PHJ. The extraction of permanent molars during the mixed-dentition period – a guide to treatment planning. Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. 1989;5:85–92.

Ectopic eruption

1. Brearley LJ, McKibben DH. Ankylosis of primary molar teeth I Prevalence and characteristics. Journal of Dentistry for Children. 1973;40:54–63.

2. Ericson S, Kurol J. Maxillary canines by extraction of the primary canines. European Journal of Orthodontics. 1988;10:283–295.

3. Jacobs SJ. Radiographic localization of unerupted teeth: further findings about the vertical tube shift method and other localization techniques. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 2000;118:439–447.

4. Power SM, Short MBE. An investigation into the response of palatally displaced maxillary canines to the removal of deciduous canines and an assessment of factors contributing to favourable eruption. British Journal of Orthodontics. 1993;20:215–223.

5. Proffit WR, Vig KWL. Primary failure of eruption. American Journal of Orthodontics. 1981;80:173–190.

6. Southall PJ, Graveley JF. Vertical parallax radiography to localize an object in the anterior part of the maxilla. British Journal of Orthodontics. 1989;16:79–83.

Maxillary expansion

1. Bishara SE, Staley RN. Maxillary expansion: clinical implications. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 1987;91:3–14.

2. Fricker JP. Early intervention: the mixed dentition. Annals of the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgery. 2000;15:124–126.

3. Glineur R, Boucher C, Balon-Perin A. Interceptive treatments (ages 6–10) of transverse deformities: posterior cross-bite. L’Orthodontie Française. 2006;77:249–252.

4. Kennedy DB, Osepchook M. Unilateral posterior cross-bite with mandibular shift: a review. Journal of the Canadian Dental Association. 2000;17:569–573.

5. Thilander B, Wahlund S, Lennartsson B. The effect of early interceptive treatment in children with posterior cross-bite. European Journal of Orthodontics. 1984;6:25–34.

Digit sucking

1. Larsen E. The effect of dummy sucking on the occlusion: a review. European Journal of Orthodontics. 1987;8:127–130.

2. Mitchell EA, Taylor BJ, Ford RP, et al. Dummies and the sudden infant death syndrome. Archives of Disease in Children. 1993;68:501–504.

3. Oulis CJ, Vadiakas GP, Ekonomides J, et al. The effect of hypertrophic adenoids and tonsils on the development of posterior cross-bite and oral habits. Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry. 1994;18:197–201.

Functional appliances

1. Bishara SE, Ziaja RR. Functional appliances: a review. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 1989;95:250–258.

2. Clark WJ. The twinblock technique. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 1988;93:1–18.

3. Twelftree CC. Functional appliances. In: Fricker JP, ed. Orthodontics and dentofacial orthopaedics. Canberra: Tidbinbilla; 1998.

Suggested reading

1. Bishara S. Textbook of orthodontics. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2001.

2. Fricker JP, ed. Orthodontics and dentofacial orthopaedics. Canberra: Tidbinbilla; 1998.

3. Kharbanda OP. Orthodontics: Diagnosis and management of malocclusion and treatment of dentofacial deformities. New York: Elsevier; 2009.