The philosophy of paediatric dentistry

Richard P Widmer and Angus C Cameron

What is paediatric dentistry?

Paediatric dentistry is a specialty based not on a particular skill set, but encompassing all of dentistry’s technical skills against a philosophical background of understanding child development in health and disease. This new edition of the handbook emphasizes again the broader picture in treating children. A dental visit is no longer just a dental visit – it should be regarded as a ‘health visit’. We are part of the team of health professionals who contribute to the well-being of children, both in an individual context and at the wider community level. Children often slip through childhood to adolescence in the blink of an eye and family life is more pressured and demanding. Commonly, children spend more time on social media than interacting directly with family and friends and, more than ever, the major influences on their lives, come from outside the family.

The pattern of childhood illness has changed and with it, clinical practice. Children presenting for treatment may have survived cancer, may have a well-managed chronic disease or may have significant behavioural and learning disorders. There are increasing, sometimes unrealistic, expectations, among parents/carers that the care of their children should be easily and readily accessible and pain-free and result in flawless aesthetics.

Caries and dental disease should be seen as reflective of the family’s social condition and the dental team should be part of the community.

Your [patients] don’t have to become your friends, but they are part of your social context and that gives them a unique status in your life. Treat them with respect and take them seriously and your practice will become to feel part of the neighbourhood, part of the community.

(Hugh MacKay, psychologist, social researcher and novelist)

In the evolving dynamics of dental practice, we feel that it is important to change, philosophically, the traditional ‘adversarial nature’ of the dental experience. It is well recognized that for too many, the dental experience has been traumatic. This has resulted in a significant proportion of the adult population accessing dental care only episodically, for the relief of pain. Thus, it is vital to see a community, and consumer, perspective in the provision of paediatric dental services. The successful practice of paediatric dentistry is not merely the completion of any operative procedure but also ensuring a positive dental outcome for the future oral health behaviour of that individual and family. To this end, an understanding of child development – physical, cognitive and psychosocial – is paramount. The clinician must be comfortable and skilled in talking to children, and interpersonal skills are essential. It will not usually be the child’s fault if the clinician cannot work with the child.

Patient assessment

History

A clinical history should be taken in a logical and systematic way for each patient and should be updated regularly. Thorough history-taking is time consuming and requires practice. However, it is an opportunity to get to know the child and family. Furthermore, the history facilitates the diagnosis of many conditions, even before the hands-on examination. Because there are often specific questions pertinent to a child’s medical history that will be relevant to their management, it is desirable that parents be present. The understanding of medical conditions that can compromise treatment is essential.

The purpose of the examination is not merely to check for caries or periodontal disease, as paediatric dentistry encompasses all areas of growth and development. Having the opportunity to see the child regularly, the dentist can often be the first to recognize significant disease and anomalies.

Current complaints

The history of any current problems should be carefully documented. This includes the nature, onset or type of pain if present, relieving and exacerbating factors or lack of eruption of permanent teeth.

Medical history

Medical history should be taken in a systematic fashion, covering all system areas of the body. The major areas include:

• Cardiovascular system (e.g. cardiac lesions, blood pressure, rheumatic fever).

• Central nervous system (e.g. seizures, cognitive delay).

• Endocrine system (e.g. diabetes).

• Gastrointestinal tract (e.g. hepatitis).

• Respiratory tract (e.g. asthma, bronchitis, upper respiratory tract infections).

• Bleeding tendencies (include family history of bleeding problems).

• Urogenital system (renal disease, ureteric reflux).

Growth and development

In many countries, an infant record book is issued to parents to record postnatal growth and development, childhood illness and visits to health providers. Areas of questioning should include:

Family and social history

• Family history of serious illness.

• Schooling, performance in class.

This last area is useful in beginning to establish a common interest and a rapport with the child. When asking questions and collecting information, it is important to use lay terminology. The distinction between rheumatic fever and rheumatism is often not understood and more specific questioning may be required. Furthermore, questions regarding family and social history must be neither offensive nor intrusive. An explanation of the need for this information is helpful and appropriate. It is important to recognize the changing patterns of family units and the carer accompanying the child may not always have a full knowledge of the past medical history.

Examination

Extra-oral examination

The extra-oral examination should be one of general appraisal of the child’s well-being. The dentist should observe the child’s gait and the general interaction with the parents or peers in the surgery. An assessment of height and weight is useful, and dentists should routinely measure both height and weight, and plot these measurements on a growth chart.

A general physical examination should be conducted. In some circumstances, this may require examination of the chest, abdomen and extremities. Although this is often not common practice in a general surgery setting, there may be situations where this is required (e.g. checking for other injuries after trauma, assessing manifestations of syndromes or medical conditions). Speech and language are also assessed at this stage (see Chapter 16).

The clinician should assess:

Charting

Charting should be thorough and detail the current state of the dentition and the plan for future treatment.

Provisional diagnosis

A provisional diagnosis should be formulated for every patient. Whether this is caries, periodontal disease or, e.g. aphthous stomatitis, it is important to make an assessment of the current conditions that are present. This will influence the ordering of special examinations and the final diagnosis and treatment planning.

Special examinations

Radiography

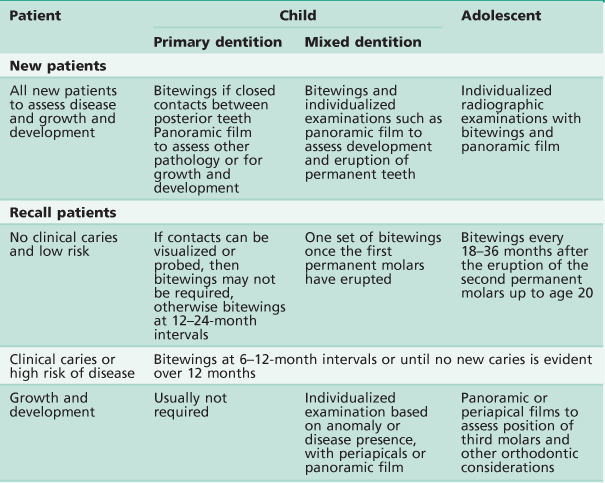

The guidelines for prescribing radiographs in dental practice are shown in Table 1.1. The overriding principle in taking radiographs of children must be to minimize exposure to ionizing radiation consistent with the provision of the most appropriate treatment. Radiographs are essential for accurate diagnosis. If, however, the information gained from such an investigation does not influence treatment decisions, both the timing and the need for the radiograph should be questioned. The following radiographs may be used:

Note that digital radiography, or the use of intensifying screens in extra-oral films, significantly reduces radiation dosage. As such, the use of a panoramic film in children is often more valuable than a full-mouth series.

Table 1.1

Guidelines for prescribing radiographsa

aBased on recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.

Other imaging

Many modern technologies are available to the clinician today, and their applications can be a most valuable adjunct not only in the diagnosis of orofacial pathology but also in the treatment of many conditions. These modalities include:

Blood investigations (see Appendix A)

Anatomical pathology

• Histological examination of biopsy specimens.

• Hard-tissue sectioning (e.g. diagnosis of enamel anomalies, see Figure 9.26).

• Scanning and transmission electron microscopy (e.g. hair from children with ectodermal dysplasia, see Figure 9.2B).

Photography

Extra-oral and intra-oral photography provides an invaluable record of growing children. It is important as a legal document in cases of abuse or trauma, or as an aid in the diagnosis of anomalies or syndromes. Consent will need to be obtained for photography.

Diagnostic casts

Casts are essential in orthodontic or complex restorative treatment planning, and for general record keeping.

Caries activity tests

Although these are not definitive for individuals, they may be useful as an indicator of caries risk. Furthermore, identification of defects in salivation in children with medical conditions may point to significant caries susceptibility. Such tests include assessment of:

Definitive diagnosis

The final diagnosis is based on examination and history and determines the final treatment plan.

Assessment of disease risk (see Chapters 4 and 5)

All children should have an ‘assessment of disease risk’ before the final treatment plan is determined. This is particularly important in the planning of preventive care for children with caries. This assessment should be based on:

Social factors including recent migration, language barriers, and ethnic and cultural diversities, can impact on access to dental care and will therefore influence caries risk.

Clinical conduct

Infection control

It is now considered that ‘universal precautions’ are the expected standard of care in current paediatric dental practice. The principles of universal precautions are:

• Prevention of contamination by strictly limiting and clearly identifying a ‘zone of contamination’.

• The need for elimination of contamination should be minimal if this zone of contamination is observed.

Universal precautions regard every patient as being potentially infectious. Although it is possible to identify some patients who are known to be infectious, there are many others who have an unknown infectious state. It is impossible to totally eliminate infection; thus, observing universal precautions is a sensible approach to minimizing the risk of cross-infection.

All children must be protected with safety glasses and clinicians must also wear protective clothing, eyewear, masks and gloves when treating patients.

Recording of clinical notes

Care must be taken when recording clinical information. Notes are legal documents and must be legible. Clinical notes should be succinct. The treatment plan should be reassessed at each session so that at each subsequent appointment the clinician knows what work is planned. Furthermore, at the completion of the treatment for the day, a note should be made regarding the work to be done at the next visit.

Use of rubber dam (see Chapter 8)

Wherever possible, rubber dam should be used for children. This may necessitate the use of local anaesthesia for the gingival tissues. When topical anaesthetics are used they must be given adequate time to work (i.e. at least 3 min). All rubber-dam clamps must have a tie of dental floss around the arch of the clamp to prevent accidental ingestion or aspiration.

Consent for treatment (see Chapter 3)

There is often little provision in a dental file for a signed consent for dental treatment. The consent for a dentist to carry out treatment, be it cleaning of teeth or surgical extraction, is implied when the parent or guardian and child attend the surgery. It is incumbent on the practitioner, however, to provide all the necessary information and detail in such a way as to enable ‘informed consent’. This includes explaining the treatment using appropriate language to facilitate a complete understanding of proposed treatment plans.

It is important to record that the treatment plan has been discussed and that consent has been given for treatment. This consent would cover the period required to complete the work outlined. If there is any significant alteration to the original treatment plan (e.g. an extraction that was not previously anticipated), then consent should be obtained again from the parent or guardian and recorded in the file.

Generally, when undertaking clinical work on a child patient, it is good practice to advise the parent or guardian briefly at the commencement of the appointment what is proposed for that appointment. Also it is helpful to give the parent or guardian and child some idea of the treatment anticipated for the next appointment. This is especially relevant if a more invasive procedure such as the use of local anaesthesia or removal of teeth is contemplated.