Intervention Research

This chapter describes a revolutionary new approach to intervention research that holds great promise for designing and testing nursing interventions. The approach is very new, and you are unlikely to find many published studies using the techniques. A growing number of scholars are beginning to seriously question the current approach to testing interventions, the “true experiment,” because modifications in the original design have decreased its validity (Adelman, 1986; Bergmark & Oscarsson, 1991; Chen, 1990; Egan, Snyder, & Burns, 1992; Fawcett et al., 1994; Lipsey, 1993; Nolan & Grant, 1993; Rothman & Thomas, 1994; Scott & Sechrest, 1989; Sechrest, Ametrano, & Ametrano, 1983; Sidani & Braden, 1998; Sidani, Epstein, & Moritz, 2003; Yeaton & Sechrest, 1981). The presentation of the new methodology for designing and testing interventions in this chapter is heavily based on two decisive books that reflect this new approach, Sidani and Braden’s (1998) Evaluating Nursing Interventions: A Theory-Driven Approach and Rothman and Thomas’s (1994) Intervention Research: Design and Development for Human Service, and on the works of scholars on which these books are based.

This chapter defines the term nursing intervention, discusses problems with the “true experiment,” provides an overview of intervention research, and describes the process of conducting intervention research. The intervention research process consists of planning the project, gathering information, developing an intervention theory, designing the intervention, establishing an observation system, testing the intervention, collecting and analyzing data, and disseminating results. Examples of the steps of intervention research are provided from published studies.

WHAT ARE NURSING INTERVENTIONS?

Nursing interventions are defined as “deliberative cognitive, physical, or verbal activities performed with, or on behalf of, individuals and their families [that] are directed toward accomplishing particular therapeutic objectives relative to individuals’ health and well-being” (Grobe, 1996, p. 50). We would expand this definition to include nursing interventions that are performed with, or on behalf of, communities. Sidani and Braden (1998, p. 8) defined interventions as “treatments, therapies, procedures, or actions implemented by health professionals to and with clients, in a particular situation, to move the clients’ condition toward desired health outcomes that are beneficial to the clients.”

A nursing intervention can be defined in terms of (1) a single act (e.g., changing the position of a patient), (2) a series of actions at a given point in time (e.g., management by an intensive care nurse of an abrupt increase in the intracranial pressure of a patient with brain injury, responding to the grief of a family whose loved one has died), (3) a series of actions over time (e.g., implementing a protocol for the management of a newly diagnosed diabetic patient by a primary care nurse practitioner, management of a chronically depressed patient), or (4) a series of acts performed collaboratively with other professionals (e.g., implementing a clinical pathway, conducting a program to reduce smoking in a community). Rather than targeting patients, some interventions target health care providers (e.g., a continuing education program), the setting (e.g., a change in staffing pattern), or the care delivery (e.g., a change in the structure of care).

Historically, nursing interventions have tended to be viewed as discrete actions, for example, “Position the limb with sandbags,” “Raise the head of the bed 30 degrees,” or “Explore the need for attention with the patient.” There is little conceptualization of how these discrete actions fit together (McCloskey & Bulechek, 2008). Interventions must be described more broadly as all of the actions required to address a particular problem (Abraham, Chalifoux, & Evers, 1992).

Some of the purposes of interventions are risk reduction, treatment or resolution of a health-related problem or symptom, management of a problem or symptom, and prevention of complications associated with a problem. Some interventions have multiple purposes or multiple outcomes or both. Desired outcomes vary with the purpose and might include continued absence of a problem, resolution of a problem, successful management of a problem, or absence of complications (Sidani & Braden, 1998).

The terminology and operationalization of a nursing intervention varies with the clinical setting and among individual nurses. Each nurse may describe a particular intervention differently. Nursing intervention vocabulary varies in different settings, such as intensive care, home care, extended care, and primary care. There is little consistency in how interventions are performed. An intervention is often applied differently each time by a single nurse and is even less consistently applied by different nurses. Even in published nursing studies, descriptions of interventions tested lack the specificity and clarity given to describing the methods of measurement used in a study (Egan et al., 1992).

The problem with definition and operationalization of nursing interventions is illustrated by the work of Schmelzer and Wright (1993a, 1993b), gastroenterology nurses who, in 1993, began a series of studies that examined the procedure for administering an enema. They found no research in nursing or medical literature that tested the effectiveness of various enema procedures. There is no scientific evidence to justify the use of various procedures for administering enemas. The amount of solution, temperature of solution, speed of administration, content of the solution (soap suds, normal saline, water), positioning of the patient, measurement of expected outcomes, or possible complications are based on tradition and have no scientific basis.

For their first study, Schmelzer and Wright (1996) conducted telephone interviews with nurses across the country in an effort to identify patterns in the methods used to administer enemas. They found none. They developed a protocol for administering enemas and pilot-tested it on hospitalized patients awaiting liver transplantation. In their subsequent study, using a sample of liver transplant patients, these researchers tested for differences in the effects of different enema solutions (Schmelzer et al., 2000). Schmelzer (1999–2001) then conducted a study funded by the National Institute for Nursing Research to compare the effects of three enema solutions on the bowel mucosa. Well subjects were paid $100 for each of three enemas, after which a small biopsy specimen was collected.

The strategy that these researchers adopted must be used to test the effectiveness of many current nursing interventions. What methods should be used for this testing, however? The “true experiment,” quasi-experimental studies, or the new intervention research methods? The “gold standard” has been the “true experiment.”

PROBLEMS WITH THE TRUE EXPERIMENT

Clark (1998) pointed out that the true experiment is based on a logical-positivist approach to research, an atheoretical strategy that focuses on discovering laws through the accumulation of facts. Few nurse researchers hold to the logical-positivist perspective. The logical-positivist approach is not consistent with nursing philosophy or with the theory-based approach through which nursing is building its body of knowledge.

Traditionally, adherence to rigid rules was required to define a study as a true experiment (Fisher, 1935). These rules were (1) random sampling from individuals representative of the population, (2) equivalence of groups, (3) complete control of the treatment by the researcher, (4) a control group that receives no treatment or a placebo treatment, (5) control of the environment in which the study is conducted, and (6) precise measurement of hypothesized outcomes. True experiments powerfully demonstrate the validity of the cause. However, the method is easier to apply when studying corn (as Fisher did) than when studying humans (as we do).

Studying humans requires modifications in the true experiment that have weakened the power of the design and threatened its validity. Because of requirements related to the use of human subjects and problems related to accessing sufficient numbers of subjects, most health care researchers have abandoned random sampling. This change has decreased the representativeness of the sample. Subjects in “true experiments” (e.g., clinical trials) are increasingly unlike the target population. Compared with the patients in a typical clinical practice, subjects selected for experimental studies are less likely to include, for example, individuals who have comorbidities; who are being cared for by a primary care provider; who are not receiving treatment; who are in a managed care program or health maintenance organization (HMO); who receive Medicare benefits; who are uninsured, undereducated, or poor; or who are members of minority groups. Treatments affect various groups differently and for some groups have no effect. Knowing how various groups are affected has become increasingly important with the advent of managed care (Orchid, 1994). Equivalence of groups, a critical element of the experimental design, continues to be addressed through random assignment. In analyzing data from clinical trials, however, Ottenbacher (1992) found random assignment ineffective in making groups more equivalent.

Complete control of the intervention is a problem in many experimental studies. Often clinicians, unskilled staff, or family members—rather than the researchers—apply the intervention. It is sometimes difficult to determine the extent to which (or even whether) a subject received the defined experimental treatment. Sometimes the intervention must be modified to meet the needs of particular subjects, a practice problematic to the assumptions of the experimental design. Comparison groups are often given the usual treatment, but the “usual treatment” or “standard care” is seldom defined. In most cases, there is wide variation in usual treatment that makes valid comparisons with the treatment group problematic and increases the risk of a type II error.

Dependent variables selected to test the intervention sometimes do not reflect actual outcomes. In many clinical situations, the desired outcomes occur a considerable time after the intervention, making them difficult, if not impossible, to measure during a reasonable period (in a funded study). Intermediate outcomes may be substituted, with the assumption that end outcomes can be inferred from intermediate outcomes, a questionable assumption in many cases (Orchid, 1994).

“True experiments,” as they were originally designed, are the most effective way to determine the validity of the cause; modifications make them less valid. Using quasi-experimental designs creates more threats to internal validity. A number of problems related to the newly defined “true experiment” threaten the validity of statistical conclusion, the most important of which is the absence of a random sample. External validity is threatened by problems with representativeness.

As a nurse researcher, to what extent can you deviate from the original definition of a true experiment and be justified in using the term to refer to your study? To what extent can quasi-experimental studies justifiably replace the true experiment as a means to validate the effectiveness of an intervention? Does an atheoretical, modified true experiment provide sufficient evidence to justify implementing an intervention in clinical practice?

With the growing demand for evidence-based practice, it is essential that nursing interventions be clearly defined and tested for effectiveness, including those that have become part of nursing through history, tradition, or trial and error, and that new interventions be designed and tested to address unresolved nursing problems (Abraham et al., 1992). What strategies, however, do we use to accomplish this goal?

INTERVENTION RESEARCH

Intervention research is a revolutionary new methodology that holds great promise as a more effective way of testing interventions. It shifts the focus from causal connection to causal explanation. In causal connection, the focus of a study is to provide evidence that the intervention causes the outcome. In causal explanation, in addition to demonstrating that the intervention causes the outcome, the researcher must provide scientific evidence to explain why the intervention causes changes in outcomes, how it does so, or both. Causal explanation is theory based. Thus, research focused on causal explanation is guided by theory, and the findings are expressed theoretically. Researchers employ a broad base of methodologies, including qualitative ones, to examine the effectiveness of the intervention (Rothman & Thomas, 1994; Sidani & Braden, 1998).

It is becoming increasingly clear that the design and testing of a nursing intervention require an extensive program of research rather than a single well-designed study (Rothman & Thomas, 1994; Sidani & Braden, 1998). It is also clear that a larger portion of nursing studies must focus on designing and testing interventions.

PROCESS OF INTERVENTION RESEARCH

The process of intervention research described here was derived from strategies currently being used in a variety of disciplines, including evaluation research and the design and development approach used in engineering. To begin the process, the researcher launches an extensive search for relevant information that can be applied to the development of an intervention theory. The intervention theory guides the design and development of an intervention, which is then extensively tested, refined, and retested. When the intervention is sufficiently refined and evidence of effectiveness has been obtained, field testing is used to ensure that the intervention can be effectively implemented in clinical settings. The researcher uses the results of these field tests to further refine the intervention and improve its clinical application. An observation system is developed for use throughout the design and development process, allowing the researcher to observe events related to the intervention naturalistically and to analyze these observations. Efforts to disseminate the newly refined intervention are extensive and are planned as an integral part of the research program.

Project Planning

Because an intervention research project comprises multiple studies conducted over a period of years, nurse researchers are advised to engage in careful planning before initiating the project. You will need to determine issues such as (1) who will be included on your project team, (2) how the team will function, and (3) whether or not to use participatory research methods, which stipulate the inclusion of stakeholders and key informants as members of the project team.

Forming a Project Team

Because of the nature of intervention research, you may need to gather a multidisciplinary project team to facilitate distribution of the work and a broader generation of ideas. Because both quantitative data and qualitative data will be gathered during the research program, your team should include members experienced in various qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis approaches. Including a team member with marketing expertise will be beneficial, because the final step of the project will be to market the intervention. Teams are enhanced by the inclusion of undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral nursing students.

Recruiting colleagues located in other areas of the country or the world for the research team can add an important dimension, permitting multisite evaluation studies. To achieve this goal, (1) contact researchers with similar interests; (2) attend specialty conferences related to the research area, during which you can dialogue with researchers and possibly extend an invitation to participate in the project; (3) invite colleagues to join the project after presentations at a professional meeting; (4) develop a project website that invites other researchers to participate; and (5) develop or participate in an Internet mailing list (Listserv) or a blog related to the topic. The process of developing a team is dynamic rather than static, with changes occurring as development of the research program continues.

Work of the Project Team

There is almost always a core group in a project team that carries on most of the work, maintains group activities, and encourages the achievement of tasks. However, other people can contribute in lesser ways to benefit the project. For example, you may want to establish liaison groups from the clinical facilities in which the intervention will be studied. In some cases, the addition of other advisory groups can be helpful.

The initial focus of the team is to clarify the problem. In analyzing identified problems, the team should answer the questions listed in Table 13-1. Considering these questions may provide new insights that redefine of the problem and may lead to a more effective intervention. Sidani and Braden (1998) have cautioned the project team to be alert to the risk of making a type III error. A type III error is the risk of asking the wrong question—a question that does not address the problem of concern. This error is most likely to occur when the researchers do not thoroughly analyze the problem and, as a result, have a fuzzy or inaccurate understanding of the issue of concern. The solution, then, does not fit the problem. A study conducted on the basis of a type III error provides the right answer to the wrong question, leading to the incorrect conclusion that the newly designed intervention will resolve the problem.

TABLE 13-1

1. For whom is the situation a problem?

2. What are the negative consequences of the problem for the affected individuals?

3. What are the negative consequences of the problem for the community (health care providers, system, or agency)?

4. Who (if anyone) benefits from conditions as they are now?

6. Who should share the responsibility for “solving” the problem?

7. What (or whose) behaviors must change for patients to consider the problem solved?

8. What conditions must change to establish or support needed change?

9. What is an acceptable level of change?

10. At what level should the problem be addressed?

11. Is this a multilevel problem requiring action at various levels of change?

12. Is it feasible (technically, financially, politically) to make changes at each identified level?

13. What (or whose) behaviors must change for providers to consider the problem solved?

15. What does each stakeholder have invested in the status quo?

Questions 1 through 12 adapted from Fawcett, S. B., Suarez-Belcazar, Y., Belcazar, F. E., White, G. W., Paine, A. L., Blanchard, K. A., et al. (1994). Conducting intervention research: The design and development process. In J. Rothman & E. J. Thomas (Eds.), Intervention Research: Design and Development for Human Service (pp. 25–54). New York: Haworth Press.

Once the problem to be examined is clarified, you must establish your goals and objectives. Project team tasks include gathering information, developing an intervention theory, designing the intervention, establishing an observation system, testing the intervention, collecting and analyzing data, and disseminating the intervention. Seeking funding for the various studies of the project will be an ongoing effort.

Using Participatory Research Methods

Some supporters of intervention research recommend establishing a participatory research strategy, which involves including representatives from all groups that will be affected by the change (stakeholders) as collaborators. (For more details on participatory research methods, see Chapter 23.) This strategy facilitates broad-based support for the new intervention from the target population, the professional community, and the general public. Disadvantaged groups are recommended as stakeholders in interventions that would or should affect members of that group (Fawcett et al., 1994). Table 13-2 lists examples of stakeholder groups.

TABLE 13-2

Examples of Stakeholder Groups

Other allied health professionals

Representatives of the target population

Residents of low-income groups

Groups for whom English is a second language

People with poor access to care

People not currently receiving care

Institutionalized psychiatric patients

Recipients of public health services

The selection of key informants is also recommended, unless the researchers are currently practicing in the setting or settings in which the intervention will be implemented (Fawcett et al., 1994). Key informants can help researchers become familiar with settings. Whether the setting is a clinical agency or an element of the community, key informants can help researchers to understand local ways and gain access to the settings. Interactions with key informants can also help you to identify what you and your research team can offer to the setting and how to articulate the benefits of the project to groups or organizations. Key informants in stakeholder groups—such as “natural leaders,” advocates, community leaders, and service providers—can furnish information useful for determining and addressing the concerns or needs of these groups as the intervention project is being planned (Fawcett et al., 1994).

If you choose a participatory research approach, your project team will consist of the researchers, stakeholders, and key informants. At the initial meeting, members of the team familiar with the process of intervention research can explain the process to the team. Next, the team can discuss the problem and possible solutions. One rule of team meetings should be that team members will avoid imposing their views of the problem or its solution on the group but, rather, will attempt to understand issues of importance to others on the project team. Use consensus to arrive at decisions. Involve all members of the team in activities such as reviewing and integrating literature and other information gathered, developing the intervention theory, designing studies, interpreting results, and disseminating findings (Fawcett et al., 1994).

Gathering Information

Conduct an extensive search for information related to the project. This gathering of information is considerably more extensive than the traditional literature review. Various methods are used to gather information. These include the methods listed in Table 13-3, which uncover in-depth information on the topics listed in Table 13-4. It is particularly important to gather sources of information about the intervention. In designing your study, you and your team do not need to reinvent the wheel. Therefore, researchers must know what others have done to address the problem.

TABLE 13-3

TABLE 13-4

Topic for Information Gathering

Problem

Intervention

How people who have actually experienced the problem have addressed it

Previous interventions designed to address the problem

Sensitivity to cultural diversity

Mediating Processes

Expected Outcomes

Potential sources of information about interventions for the problem of concern are listed in Table 13-5 and discussed here. As you explore each source of information, be sure to address the queries listed in Table 13-6. Information gathered from all sources requires careful analysis and synthesis. Undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral nursing students, as well as clinicians, working with the project team, could play a major role in gathering and synthesizing information.

TABLE 13-5

Sources of Information about Interventions

Nursing intervention taxonomies

Computerized databases containing data on nursing interventions

State-of-the-art journal articles on nursing interventions

Previous intervention studies (theses, dissertations, publications)

Clinical guidelines: www.guidelines.gov

Interviews with patients who have experienced the problem and related interventions

Interviews with providers who have addressed the problem

Interviews with researchers who have tested previous interventions

Probing of personal experiences

Observations of care provided to patients with the problem

Consumer groups who are stakeholders (e.g., Gilda Clubs, Reach for Recovery)

TABLE 13-6

Queries Relevant to All Sources

1. Are there existing interventions or practices that have been successful?

2. What made a particular practice effective?

3. Are there existing interventions or practices that were unsuccessful?

5. Which events appeared to be critical to success (or failure)?

6. What conditions (e.g., organizational features, patient characteristics, broader environmental factors) may have been critical to success (or failure)?

7. What specific procedures were used in the practice?

8. Was information provided to patients or change agents about how and under what conditions to act?

9. Were modeling, role-playing, practice, feedback, or other training procedures used?

10. What positive consequences, such as rewards or incentives, and negative consequences, such as penalties or disincentives, helped establish and maintain desired changes?

11. What environmental barriers, policies, or regulations were removed to make it easier for the changes to occur?

12. What proportion of people experiencing a specific cluster of symptoms were diagnosed (correctly or not) as having a particular diagnosis, and of this group, who received what treatment?

13. Should a treatment or procedure have been performed?

14. Did persons with a particular diagnosis receive appropriate treatment?

15. What proportion of people with the cluster of symptoms did not receive treatment?

Adapted from Fawcett, S. B., Suarez-Belcazar, Y., Belcazar, F. E., White, G. W., Paine, A. L., Blanchard, K. A., et al. (1994). Conducting intervention research: The design and development process. In J. Rothman & E. J. Thomas (Eds.), Intervention research: Design and development for human service, (pp. 25–54). New York: Haworth Press.

Taxonomies

An intervention taxonomy is an organized categorization of all interventions performed by nurses. A number of classifications of nursing interventions have been developed: the Nursing Diagnosis Taxonomy (Warren & Hoskins, 1995), Home Health Care Classifications (Saba, 1995), the Omaha System (Martin & Scheet, 1995), the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) (Bulechek & McCloskey, 1999; Bulechek, McCloskey, & Donahue, 1995; and the Nursing Intervention Lexicon and Taxonomy (NILT) (Grobe, 1996). Grobe (1996, p. 50) suggested that “theoretically, a validated taxonomy that describes and categorizes nursing interventions can represent the essence of nursing knowledge about care phenomena and their relationship to one another and to the overall concept of care.” Although taxonomies may contain brief definitions of interventions, they do not provide sufficient detail to allow one to implement the intervention. Also, the actions identified in taxonomies may be too discrete for testing and may not be linked to the resolution of a particular patient problem (Sidani & Braden, 1998).

Databases

Many health care agencies have databases that store information about patient care activities. Researchers can use these databases for secondary analyses examining many of the topics listed in Table 13-3. For example, a group of 17 home health care agencies in Tarrant County, Texas, arranged to establish a joint patient care database. All the home care nurses were provided with laptops linked to the database. They entered data related to their patient care visits into the database and were able to access information about a patient while in the patient’s home. The central database site employed nurses with master’s degrees and a statistician, as well as computer technicians. Reports from the database were generated and sent to the individual nursing homes. Data could be pooled for analysis purposes. It was possible to query the database for information on patients receiving a particular intervention. Researchers could search the database to obtain information related to patient characteristics, the timing of the intervention in relation to the emergence of the problem, costs, outcomes, and characteristics of the intervener.

Textbooks

Textbooks often provide little or no instruction on how the interventions listed should be implemented. If they provide any information, it is usually in the form of a long list of actions that nurses should take in a particular patient situation. The lists given for the same patient situation vary with the textbook (McCloskey & Bulechek, 1992). One exception is a textbook by Bulechek and McCloskey (1999) titled Nursing Interventions: Effective Nursing Treatments, which is organized by the NIC taxonomy and provides detailed descriptions of nursing interventions with a known research base. Two more recent publications describing nursing interventions for clinical practice are Gulanick and Myers’s (2007) Nursing Care Plans: Nursing Diagnosis and Intervention and Elkin, Perry, and Potter’s (2007) Nursing Interventions and Clinical Skills. Available also are Eslinger’s (2002) Neuropsychological Interventions: Clinical Research and Practice and Steckler and Linnan’s (2002) Process Evaluation for Public Health Interventions and Research.

State-of-the-Art Journal Articles

Articles delineating state-of-the-art care in relation to particular patient care situations are appearing in nursing journals. These articles generally result from an extensive review of the literature and may be a good source of information when available. They often contain a discussion of the problem and elements of an intervention theory and propose strategies for future research. References cited in such articles can often add valuable information to that obtained by computer search. Letters to the editor sections of practice journals are also good sources of information about the strategies clinicians use.

Previous Studies

Previous studies are also an important source of information about the intervention. A previous study usually discusses the problem, describes the intervention procedure, presents measurement methods for variables, offers approaches to design and analysis, gives information that can be used to determine effect size, and discusses problems related to the intervention or the research methodology. Your examination of previous studies should include theses and dissertations that may not be published. A search for other unpublished studies may yield valuable information. Use of nursing listservs can be an effective way to seek unpublished studies. As with state-of-the-art journals, references from previous studies often yield sources not identified through computer searches.

Clinical Guidelines

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and other organizations have developed clinical guidelines for patient care situations. These guidelines are available at the National Guideline Clearinghouse website at www.guidelines.gov and at the AHRQ website at www.ahcpr.gov; they are discussed in Chapters 2 and 27. Clinical guidelines define the standard of care for particular patient situations, are interdisciplinary, and are based on an extensive review of the literature focused on findings from previous studies. Although these guidelines are not specific to nursing, elements of the guidelines specify nursing actions.

Critical or Clinical Pathways

Health care agencies often develop critical or clinical pathways that define the expected care activities and the expected outcomes of the care in specific patient care situations. Critical pathways may be developed through the use of findings from previous research, analyses of agency databases, and clinical experiences of the practitioners in the agency. Some agencies consider their critical pathways to be proprietary information, limiting the possibilities of testing them and publishing the results. However, written documentation related to the pathway or interaction with committee members involved in developing the pathway can help you and other researchers to specify the problem, define the intervention, and obtain information related to moderator or mediator variables (see later discussion) and outcomes.

Evidence-Based Practice

When designing an intervention for a study, it is critical that you be aware of and current in your knowledge of evidence-based practice in the area of the intervention. Check the date that current guidelines were reviewed. Search the literature for recent interventions that may have been developed since the latest review. Broaden your search beyond the particular intervention of interest to you to include interventions in the relevant area of practice.

Provider Interviews

Clinicians are an important source of information about the intervention. They have firsthand experience in implementing interventions for the patient problem. They are more familiar than most with the nuances and variations of the situation. Their knowledge often is not sought and seldom is available in journal articles. Information from these sources about unsuccessful practices is particularly valuable (Fawcett et al., 1994).

Researcher Interviews

Interviews with researchers who have developed or tested previous interventions for the problem of concern can provide excellent information to guide the development and testing of a new intervention. Obtaining information from such interviews can often help the project team avoid repeating mistakes in designing the intervention or in developing the methodology for testing it. You can contact these researchers by phone, e-mail, webcasting, or letter. In some cases, it may be important for you to visit a site for an interview (Fawcett et al., 1994).

Patient Interviews

Patients who have experienced the problem under study can provide valuable information often not available from other sources. They offer a completely different perspective from that of providers. Patients, their family members, or both may have used interventions not documented in the literature and may have insights about what is lacking in the intervention that may not have been considered (Fawcett et al., 1994).

Probing of Personal Experience

Because of the sparseness of information in the literature on nursing interventions, you may have to rely heavily on a personal knowledge base emerging from expertise in clinical practice. You can elicit this knowledge through introspection and dialogue with colleagues.

Observations of Patient Care

Observations of patient care are essential in determining the dynamics of the process of patient care, because in many cases, the care activities are so familiar to clinicians that, in describing it, they leave out components important to the overall process. These observations will be components of the observation system described later in the chapter.

Developing an Intervention Theory

Use the knowledge obtained through a synthesis of collected information to develop a middle-range intervention theory. An intervention theory is explanatory and combines characteristics of descriptive, middle-range theories and prescriptive, practice theories. A descriptive theory describes the causal processes occurring. A prescriptive theory specifies what must be done to achieve the desired effects, including (1) the components, intensity, and duration required; (2) the human and material resources needed; and (3) the procedures to be followed to produce the desired outcomes.

An intervention theory is also action oriented, guiding the team on how to design, test, and implement the intervention. The intervention theory should contain conceptual definitions, propositions, hypotheses, and any empirical generalizations available from previous studies (Chen, 1990; Chen & Rossi, 1989; Finney & Moos, 1989; Rothman & Thomas, 1994; Sidani & Braden, 1998). The theory will be further refined during the design and development process. Master’s and doctoral nursing students, working in collaboration with faculty researchers or with the project team, can provide valuable input for the development of the intervention theory by (1) conducting literature reviews and synthesis; (2) developing class papers related to the intervention theory; (3) conducting class discussions about the intervention theory, which are then communicated to the project team; or (4) meeting with the project team to participate in discussions during development of the intervention theory.

An intervention theory must include a careful description of the problem the intervention will address, the intervening actions that must be implemented to address the problem, moderator variables that might change the impact of the intervention, mediator variables that might alter the effect of the intervention, and expected outcomes of the intervention. Table 13-7 lists the components of an intervention theory. Further detail about developing each intervention theory element is provided in the following discussion.

TABLE 13-7

Elements of Intervention Theory

Problem

Critical Inputs

Mediating Processes

Stages of change that occur after the intervention

Expected Outcomes

Aspects of health status affected

Spiritual v Timing and pattern of changes

Treatment Delivery System Resources

Problem

The problem that the intervention theory addresses might be one of alterations in function or of inadequacies in functioning that have the potential of resulting in dysfunction. The problem might also be expressed as a nursing diagnosis. Your theoretical description of the problem must include a discussion of its causal dynamics and how the problem is manifested. You must address the causal processes through which the intervention is expected to affect the problem. You must also clarify variations of the problem in different populations and in different conditions. The following excerpt, from a study by Colling and Buettner (2002), is an example description of a problem that an intervention theory might address.

Intervention

The theoretical presentation of the intervention must specify what actions, procedures, and intervention strength are required to produce the desired effects. Causal interactions among various elements of the intervention must be explored.

Strong interventions contain large amounts of the elements constituting the intervention. Strength of intervention is defined in terms of amount, frequency, and duration. Intensity of an intervention defines the amount of each activity that must be given and the frequency with which each activity is implemented. Duration of an intervention is the total length of time the intervention is to be implemented (Scott & Sechrest, 1989; Sechrest et al., 1983; Sidani & Braden, 1998; Yeaton & Sechrest, 1981). For example, if the intervention were mouth care for stomatitis (controlling for severity, white blood count, and day in the treatment cycle), strength would be (1) the amount or concentration of mouth solution used, (2) the frequency with which the mouth care was given, and (3) the number of days (duration) that the mouth care was provided.

Some interventions are relatively simple, and others may be complex. The complexity of the intervention is determined by the type and number of activities to be performed. Complex, multicomponent interventions may require multiple, highly skilled interveners. The research team must explore the effect of moderator variables (see later discussion) on the effectiveness of the intervention. The theoretical presentation given here guides the operational development of an intervention design by Colling and Buettner (2002).

Table 13-8 lists examples of items developed and what behaviors the items were used for.

TABLE 13-8

| Name of Item | Behavior Item Used For |

| Activity apron | Repetitive motor patterns |

| Stuffed butterfly or fish | Verbal repetitiveness |

| Cart for wandering | Wandering and taking med cart |

| Electronic busy box | Passivity |

| Fishing box | Hand restlessness |

| Fleece covered hot water bottle | Screaming |

| Flower arranging | Hand restlessness |

| Electronic busy box | Passivity |

| Hang the laundry | Wandering and restlessness |

| Home decorator books | Sad, weepy, upset |

| Latch box-doors | Verbal agitation |

| Look inside purse | Wandering, upset, hand restlessness |

| Message magnets | Difficulty making needs known |

| Muffs | General agitation and anxiety |

| Rings on hooks game | Motor restlessness |

| Sewing cards | Passivity and hand restlessness |

| Squeezies | Anxiety and hand restlessness |

| Table ball game | Wandering and trying to leave |

| Tablecloth with activities | Boredom, isolation, hand restlessness |

| Tetherball game | Verbal or motor repetitiveness |

| Vests/sensory | Verbal or motor repetitiveness |

| Wave machines | Repetitive hand movements |

From Fitzsimmons, S., & Buettner, L. L. (2002). Therapeutic recreation interventions for need-driven dementia-compromised behaviors in community-dwelling elders. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 17(6), 367–381.

Moderator Variables

A moderator variable is, in effect, a separate independent variable affecting outcomes. A moderator variable alters the causal relationship between the intervention and the outcomes. The moderator effect occurs simultaneously with the intervention effect. A moderator variable also may interact with elements of the intervention to alter the direction or strength of changes caused by the intervention. Thus, a moderator variable could cause the intervention to have a negative rather than a positive effect or to have a less powerful effect on outcomes. Moderator variables could also increase the maximum effectiveness of the treatment. An understanding of the causal links between moderator variables and the intervention is critical to implementing an effective intervention in various patient care situations. Moderator variables may be characteristics of patients or of interveners, or they may be situational (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Lindley & Walker, 1993).

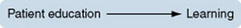

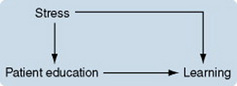

One of the most familiar moderators is the effect of stress on learning from the intervention of patient education. The causal relationship in this case can be modeled as follows:

The level of stress occurring during patient education can change the effect of the education. In very low stress, the patient may not experience a need to know what he or she is being taught; thus, learning is reduced. High stress during patient education interferes with the patient’s ability to incorporate and apply the information provided and thus reduces learning. Moderate stress during patient education maximizes the effect of the intervention.

The level of stress also has a direct effect (as an independent variable) on learning. The relationship of stress in this case could be modeled as follows:

Colling and Buettner (2002), in developing their intervention, used the middle-range theory of the Needs-Driven Dementia-Compromised Behavior Model (Algase et al., 1996).

Mediator Variables and Processes

A mediator variable brings about treatment effects after the treatment has occurred. The effectiveness of the treatment process relies on mediator variables. The intervention may have a direct effect on the outcomes, a direct effect on the mediator or mediators, and an indirect effect on outcomes through the mediator variables. The relationship could be modeled as follows:

In other cases, the effect of the intervention occurs only through its effect on the mediator, as follows:

The expected outcomes of an intervention are the result of a transformational process that occurs as a series of changes in participants and mediator variables after the intervention has been initiated. The series of changes are referred to as mediating processes. For any intervention, a number of mediating processes may ensue before the implementation leads to the outcomes. Although broadly the intervention causes the outcomes, defining the mediating processes explains exactly how the intervention causes the outcomes.

To understand each mediating process, the researcher must dissect the causal processes to identify hypothesized relations among the mediator variables that result in the outcomes. Because the same variable can function as a mediator in some situations and as a moderator in other situations, it is important for the intervention theory to specify the mediator-moderator role of the different variables important to the understanding of the phenomenon of interest. The stages of change through which a participant progresses in the transition to the desired state can be expressed in the map of the intervention theory (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Lindley & Walker, 1993; Sidani & Braden, 1998).

Colling and Buettner (2002) provided the following discussion of mediating processes in their intervention theory:

Expected Outcomes

Outcomes are determined by the problem and purpose of the intervention and are the various effects of the intervention. They reflect the changes that occur as a consequence of the intervention. Outcomes may be physical, mental, social, spiritual, or any combination of these types. The timing and pattern of changes must also be specified. Timing is the point in time after the intervention that a change is expected to occur. Some changes occur immediately after an intervention, whereas others may not appear for some time. Mediators are referred to in some studies as intermediate outcomes. Hypothesized interrelationships among the outcomes must be indicated in the theory.

Extraneous Factors

Extraneous variables are elements of the environment or characteristics of the patient that significantly affect the problem, the treatment process, or the outcomes. Unlike mediator variables, extraneous factors tend not to be well understood and often are unidentifiable until a study has been initiated. They are seldom included in explanations of the causal links between intervention and outcomes. Thus, they are extraneous to existing theoretical explanations of cause. They are sometimes referred to as confounding variables. If the researcher recognizes their potential effect, extraneous factors may be held constant (not allowed to vary) or measured so that they can be statistically controlled during analysis. Careful analyses may indicate that some variables defined as extraneous are actually moderator or mediator variables (Sidani & Braden, 1998).

Patient Characteristics

Researchers are increasingly attending to the influence of individual characteristics on the patients’ response to illness or to treatment. Sidani and Braden (1998, p. 64) pointed out that “client characteristics may affect the clients’ general susceptibility to illness; the nature and extent of the presenting problem; the design and selection of interventions; the clients’ beliefs, values, and preferences for treatments; and the clients’ response to illness and to treatment.” Patient characteristics also affect the extent to which the patient becomes involved in health-promoting lifestyles.

Patient characteristics of importance to a particular intervention can be identified (1) during the information-gathering period, (2) through pilot studies designed to test the intervention, and (3) through the established observation system. The intervention theory must identify and categorize patient characteristics that have the potential of influencing response to the treatment (Frank-Stromborg, Pender, Walker, & Sechrist, 1990; Johnson, Ratner, Bottroff, & Hayduk, 1993). As the nurse researcher, you must identify or develop methods to measure patient characteristics relevant to the intervention using the observation system. Table 13-9 lists patient characteristics that researchers have identified as influencing the response to illness or treatment.

TABLE 13-9

Personal Characteristics

Illness or Health-Related Characteristics

Environmental Factors

An intervention “occurs in a sociocultural, economic, political, and organizational context, any part of which may affect both the processes and the outcomes, usually in ways we little understand” (Hegyvary, 1992, p. 21). Two environmental factors of particular importance to the problem, the intervention, and the outcomes in many intervention theories are intervener characteristics and setting characteristics.

Intervener Characteristicsh: Interveners are individuals who help to deliver the study intervention. They are usually health care professionals functioning in the role of clinicians or researchers. In some cases, however, the intervener may be a family member, a neighbor, the patient, or an unskilled staff person employed within the treatment delivery system. The personal and professional characteristics of interveners affect interpersonal and technical aspects related to implementing the intervention. Thus, it is essential for researchers to identify important intervener characteristics in the intervention theory. Develop measurement methods that you can use to gather data on the interveners for the observation system. Table 13-10 lists some of the personal and professional intervener characteristics identified by Sidani and Braden (1998) that might modify the implementation of an intervention.

Setting Characteristics: The setting in which the intervention will be delivered has a potential influence on the expected intervention outcomes. For example, variation in the clinical activities performed by the staff nurses in different settings can affect outcomes. The setting can serve as a moderator variable either by facilitating or impeding implementation of the intervention or by muting or intensifying intervention effects (Conrad & Conrad, 1994). In addition, the setting may modify the way the intervention is implemented. Such influences can threaten the external validity of conclusions and cannot be ignored.

Other aspects of the setting that the intervention theory must address are the resources needed to carry out the activities of the intervention. Resources include (1) equipment, (2) space for the intervention, (3) the availability of adequately educated professional interveners with the experience needed to provide the intervention, (4) adequate support staff, (5) a political-social environment that facilitates implementation of the intervention, and (6) access to telephones and computers (Sidani & Braden, 1998). Table 13-11 lists some of the setting characteristics identified by Sidani and Braden (1998).

Health Care System: In today’s health care arena, factors related to the system of care within which the intervention is provided may play an important role in the effectiveness of the intervention. The system of care may be a managed care system, a health maintenance organization (HMO), a home health care system, a nursing home corporation, the community, a primary care provider’s office, a public health clinic in the community, or the patient’s home. In some cases, the patient may be the community, and a group of committed citizens may be the health care system of interest.

Developing a Conceptual Map of the Intervention Theory

The researcher should develop a map illustrating the elements of the intervention and the causal links among them. Elements must be clearly defined, and causal links explained. Your map should show all causal pathways described in the intervention theory, including moderator and mediator variables. List all of the testable propositions that the theory has generated.

Designing the Intervention

During the design period, and guided by the intervention theory, the project team specifies the procedural elements of the intervention and develops an observation system (Fawcett et al., 1994). The intervention may be (1) a strategy, (2) a technique, (3) a program, (4) informational or training materials, (5) environmental design variables, (6) a motivational system, or (7) a new or modified policy. The intervention must be specified in sufficient detail to allow interveners to implement it consistently.

During the design process, the intervention will emerge in stages, as it is repeatedly tested, redesigned, and retested. Training materials and programs for interveners also must be developed and repeatedly tested and revised. Design criteria are established to evaluate the implementation of the intervention and outcomes.

In addition to a detailed development of the intervention, an operational development of the design guided by the theory should include the following activities:

• Define the target population.

• List acceptable strategies for selecting a sample.

• Identify subgroups that might show differential effects of the intervention.

• Specify essential characteristics of interventionists.

• Indicate appropriate measures of variables.

• Specify the appropriate time or times to measure outcomes.

• Indicate what analyses to perform and what relationships to test on the basis of the relationships among the treatment and the moderator, mediator, and outcome variables specified by the intervention theory.

Intervention Fidelity

Intervention fidelity occurs when the interventionist reliably and competently delivers the experimental treatment (Stein et al., 2007). An interventionist is a person who has been formally prepared to provide a particular intervention and is accountable for the fidelity of the intervention. Methods to adhere to the intervention protocol are critical to the success of an intervention study. The internal validity of a study requires the independent variable (the intervention) to be administered systematically and consistently. The interventionists must conform to the intervention protocol and have sufficient competence to administer the intervention. The behaviors proscribed by the intervention protocol are delivered in sessions or classes designed to prepare the interventionists. Strategies to improve intervention fidelity may include intervention manuals, formal training, and clinical supervision. To evaluate intervention fidelity, before and during the study, coders may be used to evaluate audio or audiovisual tapes, to observe of the interventionist during practice, and to apply other means using rating scales. These coders are part of the observation system described later. The coders’ observation activities may occur during pilot studies and periodically during the study. They are implemented during the study to test for drift. Drift is a gradual change in the consistency in treatment delivery over the course of the study.

Interventionists

Interventionist behaviors in relation to the administration of the intervention are usually evaluated in pilot tests before a study has been initiated and during the period of the study. Three behaviors of interventionists concern us here: (1) those prescribed by the intervention, (2) those that are universal in therapeutic interactions, and (3) those proscribed by the intervention. These three constitute the distinctiveness and purity of the intervention. Prescribed behaviors are those that are elements of the interventions. Universal behaviors are those that any practitioner in the situation would commonly do, such as establishing rapport with the patient, explaining the goals of the interventionist, or explaining the intervention process to the patient. Proscribed behaviors are those that the interventionist must not do or discuss. For example it is essential that the interventionist not use strategies from competing interventions, as this will weaken the capacity to test for differences in the experimental intervention and comparison interventions (Stein et al., 2007).

Establishing an Observation System

The use of an observation system is a novel idea in nursing research. They are not used frequently. However, the observation system is one of the important strengths of intervention research. It is designed and implemented before any changes are made in the patient care situation. An observation system allows you and other researchers to (1) observe events related to the phenomenon naturalistically, (2) discover the extent of the problem, (3) observe the intervention being implemented, and (4) detect effects of the intervention. Patients affected by the problem under study can help identify behaviors and environmental conditions that must be observed. Observations should be made also of patient characteristics, intervener characteristics, setting characteristics, dynamics of the health care system, and use of resources (Fawcett et al., 1994; Sidani & Braden, 1998). Possible elements of the observation system are listed in Table 13-12.

TABLE 13-12

Elements of Observation System

Before the Intervention

Characteristics of the problem

Characteristics of patients with the problem who receive the intervention

Characteristics of patients with the problem who do not receive the intervention

Professional and personal characteristics

Resources used (e.g., equipment and supplies)

Events occurring during the study that affected the intervention

During the Intervention

Who were the target population?

How many participants were recruited?

How many who were approached refused to participate?

What reasons did they give for refusal?

What were the characteristics of the participants?

What were the characteristics of those who refused to participate?

How do those who accepted and those who refused compare with the target population?

Professional and personal characteristics

Were training sessions provided?

What interveners attended training sessions?

How did interveners relate to participants?

Did more than one intervener care for a participant?

Administrative arrangements made

Events occurring during intervention that might affect implementation

After the Intervention

Observations lead to insights about what must be changed by the intervention or in the system so that the intervention can be effective. The observation system also serves as a means of feedback for refining early prototypes of the intervention and, thus, is closely tied to designing and pilot-testing the intervention. Behavioral events that are elements of the intervention or that are components of the environment that could influence the effectiveness of the intervention must be defined and observed. The observation activities provide information that is important for specifying the procedural elements of the intervention. These elements include (1) the use of information, (2) the use of skills, (3) training, (4) environmental change strategies, (5) the policy changes or enforcement strategies used, and (6) reinforcement and punishment procedures (Fawcett et al., 1994; Sidani & Braden, 1998).

Nursing students at all levels of education could participate in the observation system. The system could give undergraduate students the chance to participate clinically in nursing research activities. Students involved in research projects, theses, or dissertations might gather or analyze data for the observational system.

The observational methods used and the extent of observations vary with the financial and personnel resources available. The observation system should be developed based on knowledge acquired through the information-gathering process. The observation system must include measures of variables in the setting that might affect the problem, the intervention, or the outcomes. Possible elements of the observation system are listed in Table 13-12.

Researchers must design the observation system carefully and include methods for measuring the elements of interest. Your procedures should be specified in enough detail that they can be replicated. Observers must be carefully trained. Observations must be made before initiation of the intervention, during the intervention, and after the intervention. Your observation system must allow monitoring of the extent to which the intervention was implemented as planned during the period in which it was provided.

The types of measurement you will use depend on a number of factors, such as (1) the number of individuals and behaviors being observed, (2) the length of observations, (3) the size of observation intervals during an observation session, and (4) the availability of observers. You might include measures such as tape-recorded interviews, field notes of observers, coding forms, checklists, knowledge tests, scales to measure aspects such as attitudes or beliefs, measures of physiological dimensions of the patient state, videotapes of the intervention being provided, and event logs. In addition to measures for direct observation, you may need to establish measures for patients or interveners to self-monitor or self-report about events that are difficult for you or your team to observe directly (Barlow, Hayes, & Nelson, 1989).

The validity and reliability of measurement methods used must be evaluated. You must develop criteria for the observer to apply when determining whether or not the event being studied has occurred. Use these criteria to determine the start of an observation period (Fawcett et al., 1994). Steps of the observation process are listed in Table 13-13.

TABLE 13-13

Steps of the Observation Process

1. Determine elements that must be observed on the basis of the intervention theory.

2. Develop methods of measuring essential elements.

3. Develop criteria for determining whether or not the event to be observed has occurred.

6. Develop scoring instructions to guide recording of desired behaviors or products.

7. Develop a schedule of observations to include the following:

a. What is happening before the intervention is implemented

8. Perform preliminary analysis of preintervention data.

9. Apply preliminary analysis results to further develop the intervention.

10. Analyze changes in environment and behaviors before, during, and after the intervention.

Testing the Intervention

The intervention is tested in stages, revised, and retested until a satisfactorily designed intervention emerges. The stages of testing are (1) development of a prototype, (2) analogue testing, (3) pilot testing, (4) formal testing, (5) advanced testing, and (6) field testing.

Developing a Prototype

A prototype is a primitive design that has evolved to the point that it can be tested clinically. The prototype is defined by the intervention theory. Developing a prototype involves establishing and selecting a mode of delivering the intervention. Considerable refinement would be required before a prototype could be used in an intervention study (Fawcett et al., 1994).

Analogue Testing

For some interventions, before the pilot test, it is useful to test prototypes in analogue situations, using actors to play roles in the intervention. Members of the project team, staff from the settings to be used for the project, or nursing students might perform these roles. The actor interveners follow the intervention steps prescribed by the prototype. Videotapes of the proceedings will allow you to carefully analyze the adequacy of the prototype. Observers also make notes during the prototype test of missing elements, insights gained, or questions that the project team must explore (Fawcett et al., 1994).

Pilot Testing

Multiple pilot tests are needed for intervention research. These pilot studies are used for the following purposes:

1. To determine whether the prototype will work.

2. To guide refinement of the prototype. The intervention is first evaluated according to standards established in that particular care situation. The established design criteria are then used to evaluate the effectiveness of the prototype. This evaluation enables the researchers to optimize the intervention before further testing.

3. To test and refine instructions, manuals, or training programs.

4. To determine whether the intervention has been described in sufficient detail to allow clinicians and other researchers to replicate the work. Clinicians should also be queried about their reasoning and decisions during the implementation of the intervention.

5. To examine reliability, validity, and usability of measurement methods in the target population.

Pilot tests should be conducted in settings similar to those in which the intervention will be used and with subjects similar to those who will typically be receiving the intervention. Use observation techniques to gather the information you will need to revise the prototype. Pilot tests are ideal for graduate nursing student research projects, theses, or dissertations conducted in collaboration with the project team. Colling and Buettner (2002) described the development of their observational system and intervention as follows.

Three different Simple Pleasures items were introduced each week at a short staff in-service and family education session. Staff, family, and visitors were asked to try the various items and provide feedback to the research team.

Formal Testing

The most desirable formal test of the intervention is a conventional experimental design to determine whether the intervention causes the intended effects. The design should be as rigorous as possible. Use power analyses to determine a sample size sufficient to avoid a type II error. Perform analyses to ensure that the treatment and control groups are comparable on important variables. Use measurement instruments whose reliability and validity has been documented. Report the effect size for each outcome examined. The observation system established before the initiation of testing is continued, and patient characteristics, intervener characteristics, and setting characteristics are measured (Sidani & Braden, 1998). Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or multivariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) is commonly used to test for effects of the intervention.

Identifying the Required Resources:

The formal test of an intervention must occur in a setting that can provide the required resources to implement the intervention optimally. The nature of the intervention and its level of complexity define the resources needed. The resources required include (1) institutional support for testing the intervention, (2) the availability of equipment and materials needed to administer the intervention, (3) the availability of target participants who would benefit most from the intervention, and (4) interveners with the full range of skills needed to implement the intervention. If any of these resources is at a level less than required, delivery of the intervention may vary, affecting the intervention outcomes (Chen, 1990; Lipsey, 1993; Rosen & Proctor, 1978; Sidani & Braden, 1998).

Maintaining the Integrity of the Intervention: In a formal test of an intervention, it is critical that the integrity of the intervention be maintained. Integrity of an intervention is the extent to which the intervention is implemented as it was designed. The design defines what activities are to be done and when, where, how, and by whom they are to be carried out.

Lack of intervention integrity is a discrepancy between what was planned and what was actually delivered. It may occur if the intervention is not clearly described or if the interveners do not have a clear understanding of what activities to perform, when, or with whom. Lack of integrity can occur because interveners were not sufficiently trained or lacked guidance during the period of formal testing. In some cases, interveners may not interpret instructions as the researchers expected. This is most likely to occur when elements of the intervention are not well defined and clearly circumscribed, leading to different interpretations by the interveners (Kirchhoff & Dille, 1994; Rezmovic, 1984; Sechrest et al., 1983; Sidani & Braden, 1998; Yeaton & Sechrest, 1981).

Loss of integrity can also occur because participants are exposed to different elements of the intervention or given different levels of strengths of the intervention. Loss of integrity may occur because the intervention is not provided in a consistent manner, interveners tailor the intervention to the needs of individual patients, or the intervention requires the participants to implement the intervention in settings away from the intervener’s immediate supervision. These differences lead to disparities in levels of outcomes and can result in an inability to detect significant treatment effects; thus, they may lead to incorrect conclusions about the effectiveness of the intervention (Rezmovic, 1984; Rossi & Freemen, 1993; Sidani & Braden, 1998; Yeaton & Sechrest, 1981). Level of response and motivation of subjects is another factor that causes outcomes to vary. Factors affecting intervention integrity are listed in Table 13-14.

TABLE 13-14

Factors Affecting Integrity of Intervention

Inadequate training of interveners

Variation in strength of intervention provided

Variation in elements of intervention provided

Ease in implementing intervention activities

Intervention’s level of complexity

Inadequate guidance during study

Level of staff commitment to the intervention

Level of organizational commitment to the intervention

Number of sites involved in implementing the intervention

Level of compliance of staff with treatment protocol

Interactional style of interveners

Changes in organization policies after initiation of study

Kirchhoff and Dille (1994) described problems they experienced in maintaining the integrity of their study intervention:

On the basis of these experiences, which they were good enough to share with us, Kirchhoff and colleagues modified their intervention protocol for future studies (Dille & Kirchhoff, 1993; Dille, Kirchhoff, Sullivan, & Larson, 1993).

Advanced Testing

Advanced testing of the intervention occurs after sufficient evidence is available that the intervention is effective in achieving desired outcomes. This stage of testing might begin after a single, well-designed study indicates a satisfactory effect size but is more likely to be initiated after a series of studies in which the intervention is modified or the findings are replicated. Advanced testing focuses on identifying variations in effectiveness based on patient characteristics, intervener characteristics, and setting characteristics.

Testing Variations in Effectiveness Based on Variations in Patient Characteristics: Intervention effects that have been determined through the use of a sample of white, middle-class Americans may not have the same effect with other groups. The intervention should be tested in various ethnic groups. Pilot tests may reveal a need to refine the intervention to make it culturally appropriate. The poor and undereducated may respond differently to interventions, because (1) they have a different view of health and of preventive behaviors and (2) they may not understand educational components of interventions that were designed for people with a higher level of education. For the same reasons, scales designed for the white middle class may not be effective measures in different ethnic groups or in the undereducated. Thus, modifications in the intervention and in the design may be necessary.

Studies also must be conducted to examine the effect of the intervention on groups with comorbidities or differing levels of severity of illness. Other variations in patient characteristics, such as age, gender, and diagnosis, may be important to examine. Characteristics specific to the intervention may be identified as important for determining differential effects. If sufficiently large samples were obtained in the initial study, these patient characteristics may be available from the observation system and may involve secondary analyses of available data.

Testing Variations in Effectiveness Based on Setting:

If your setting is held constant, so that all interventions are provided in the same place, under the same conditions, and among all subjects, the effects of your setting will be potentially confounded with the treatment effects. Therefore, one component of testing the intervention is to set up multisite projects, in which the settings are varied and the effects of the settings on outcomes are examined (Sidani & Braden, 1998).

Testing Variations in Effectiveness Based on Variations in Intervener Characteristics: The initial study examining the effectiveness of an intervention is usually conducted under ideal conditions. Ideal conditions involve the selection of highly educated interveners judged to be experts in the field of practice related to the intervention. However, after the intervention is found to be effective, questions arise regarding the use of less well-prepared interveners to provide the intervention. Studies should be conducted to determine variations in the effectiveness of the intervention based on the competencies of interveners.

Testing Variations in Effectiveness Based on Strength of an Intervention: The strategy of testing the variations of an intervention’s strength is used to determine the amount of treatment that provides optimal strength in achieving the desired outcome. To test this issue, the researcher must be able to provide varying doses of the intervention. You might vary the intensity of the intervention, the length of time of a single treatment, the frequency of an intervention, or the span of time over which the intervention is continued or repeated.

Path Analyses: Path analyses examine the causal processes through which each component of an intervention has its effect, including moderator and mediator variables. The design tests the validity of the intervention theory. Reliable measures of each of the processes and each of the outcome variables are included in the design. Structural equation analysisexamines the contribution of each component to the outcome (Sidani & Braden, 1998).

Preference Clinical Trials: In the typical clinical trial, subjects are randomized into groups. However, in some cases, patient preference is an important variable. The effect of active choice on outcomes is important to understand. Wennberg, Barry, Fowler, and Mulley (1993, p. 56) indicated that “when symptom reduction and improvement in the quality of life are the main effects of treatment and the proper decision involves the evaluation of risk aversion and degree of botheredness, then these topics cannot be ignored; they must be made the object of investigation.” Thus, in preference clinical trials, rather than being randomized to subject groups, patients choose among all treatments available.

Treatment Matching: Treatment matching compares the relative effectiveness of various treatments. Treatment matching designs are used when the following conditions are met: (1) there is no clearly superior treatment for all individuals with a given problem; (2) a number of treatments with some proven efficacy have comparable effectiveness for undifferentiated groups of subjects; and (3) there is evidence of differential outcomes, either within or among treatments, for defined subtypes of patients (Donovan et al., 1994). No control group is used. The researcher selects sampling criteria to promote heterogeneity rather than homogeneity. Randomization is used, but stratification, matching, and other strategies can be used to obtain balanced distribution. Creative sampling methods may be required to fulfill sampling requirements (Carroll, Kadden, Donovan, Zweben, & Rounsaville, 1994; Connors et al., 1994; DiClemente et al., 1990; Miller & Cooney, 1994; Zweben et al., 1994).

Testing the Effectiveness of Individual Components of Complex Interventions: In complex interventions, whether all elements of the intervention or only some of them are causing the expected outcomes is not always clear. It is important in such cases to conduct studies to examine the differential effects of intervention elements.

West, Aiken, and Todd (1993) have described a series of designs that can be used to test the effectiveness of various components of such a treatment; these strategies are summarized on the following pages. Used as components of an intervention effectiveness research program, these strategies must be conducted with the guidance of the intervention theory and implementation of the observation system.

Dismantling Strategy (Subtraction Design): In dismantling strategy, the full version of the program is compared with a reduced version in which one or more components have been removed. Criteria for selecting components to delete vary but are often based on theory or on information from the literature. Components that are expensive or difficult to provide may also be selected for deletion. Components are removed one at a time, and the reduced set is tested against the full version until a single base component remains. When programs are complex and include many components, various mixes of components may be tested.

Constructive Strategy: In constructive strategy, a base intervention is identified. A component that is expected to increase the effectiveness of the base intervention is added, and the two interventions are tested. There must be a theoretical rationale for the selection of components to add to the base intervention. The components are added one at a time, and each set of components is tested for effectiveness until the full set of possible combinations has been studied. With the use of the dismantling strategy in large programs, various mixes of components may be tested.

Factorial ANOVA Designs: Commonly used in psychology, factorial ANOVA designs are potentially the most powerful way to examine all possible combinations of an intervention. Factorial designs used in intervention trials are usually limited to a 2 × 2 design, examining the presence or absence of two intervention components. Factorial ANOVA designs usually involve a multisite project with a large sample size to achieve adequate statistical power. The complexity of the design increases with the number of components in the intervention.