Chapter 23 The periodontal tissues and periodontal disease

INTRODUCTION

An overall assessment of the periodontal tissues is based on both the clinical examination and radiographic findings — the two investigations complement one another. Unfortunately, like many other indicators of periodontal disease, radiographs only provide retrospective evidence of the disease process. However, they can be used to assess the morphology of the affected teeth and the pattern and degree of alveolar bone loss that has taken place. Bone loss can be defined as the difference between the present septal bone height and the assumed normal bone height for any particular patient, taking age into account. In fact radiographs actually show the amount of alveolar bone remaining in relation to the length of the root. But this information is still important in the overall assessment of the severity of the disease, the prognosis of the teeth and for treatment planning.

SELECTION CRITERIA

Several radiographic projections can be used to show the periodontal tissues. Those recommended by the Faculty of General Dental Practice (UK) in 2004 in their booklet Selection Criteria in Dental Radiography are summarized in Table 23.1.

Table 23.1 Summary of radiographs recommended for periodontal assessment based on the Faculty of General Practice (UK)’s Selection Criteria in Dental Radiography in 2004

| Clinical indication | Radiographs |

|---|---|

| Uniform pocketing < 6 mm | Horizontal bitewings |

| Uniform pocketing > 6 mm | Vertical bitewings + selected paralleling technique periapicals |

| Irregular pocketing | Bitewings — horizontal or vertical + selected paralleling technique periapicals |

| Widespread pocketing and other dental problems | Panoramic radiograph + selected paralleling technique periapicals |

| Periodontal/endodontic lesions | Paralleling technique periapicals |

In addition, digital radiography and image manipulation including subtraction and densitometric image analysis (see Ch. 7), may assist in showing and measuring subtle changes in fine alveolar and crestal bone pattern. However, these techniques require the inclusion of a reference object of known density and a highly reproducible positioning technique to be helpful.

Important points to note

• In the interpretation of the periodontal tissues, images of excellent quality are essential — perhaps more so than in other dental specialities — because of the fine detail that is required.

• Exposure factors should be reduced when using film-based techniques to avoid burn-out of the interdental crestal bone.

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES OF HEALTHY PERIODONTIUM

A healthy periodontium can be regarded as periodontal tissue exhibiting no evidence of disease. Unfortunately, health cannot be ascertained from radiographs alone, clinical information is also required.

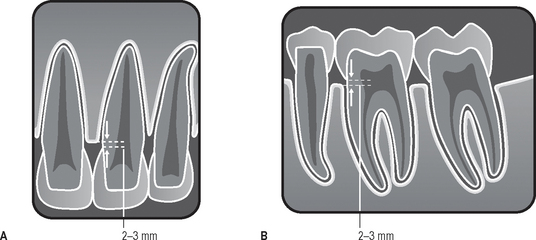

However, to be able to interpret radiographs successfully clinicians need to know the usual radiographic features of healthy tissues where there has been no bone loss. The only reliable radiographic feature is the relationship between the crestal bone margin and the cemento–enamel junction (CEJ). If this distance is within normal limits (2–3mm) and there are no clinical signs of loss of attachment, then it can be said that there has been no periodontitis.

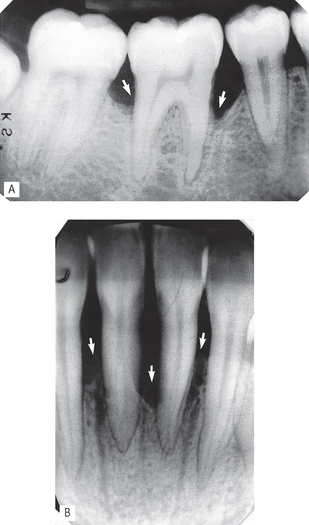

The usual radiographic features of healthy alveolar bone are shown in Figures 23.1 and 23.2 and include:

• Thin, smooth, evenly corticated margins to the interdental crestal bone in the posterior regions.

• Thin, even, pointed margins to the interdental crestal bone in the anterior regions.

• Cortication at the top of the crest is not always evident, owing mainly to the small amount of bone between the teeth anteriorly.

• The interdental crestal bone is continuous with the lamina dura of the adjacent teeth. The junction of the two forms a sharp angle.

• Thin even width to the mesial and distal periodontal ligament spaces.

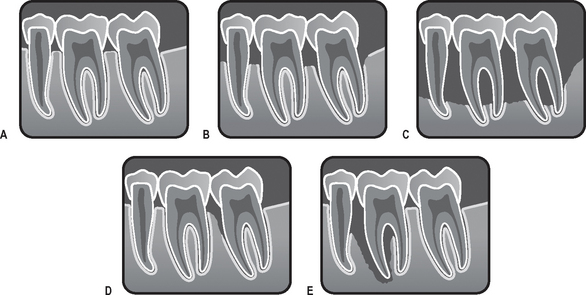

Fig. 23.1 Diagrams illustrating the radiographic appearances of a healthy periodontium. A The upper incisor region. B The lower molar region. The normal distance of 2–3mm from the crestal margin to the cemento–enamel junction is indicated.

Fig. 23.2 Paralleling technique periapical radiograph of  (slightly reduced exposure) showing the radiographic features of a healthy periodontium (arrowed).

(slightly reduced exposure) showing the radiographic features of a healthy periodontium (arrowed).

Important points to note

• Although these are the usual features of a healthy periodontium, they are not always evident.

• Their absence from radiographs does not necessarily mean that periodontal disease is present.

• Failure to see these features may be due to:

• Following successful treatment, the periodontal tissues may appear healthy clinically, but radiographs may show evidence of earlier bone loss when the disease was active. Bone loss observed on radiographs is therefore not an indicator of the presence of inflammation.

CLASSIFICATION OF PERIODONTAL DISEASE

Various classifications of periodontal disease have been put forward over the years. The most comprehensive, although not universally agreed, was produced by the International Workshop of the American Academy of Periodontology and the European Federation of Periodontology in 1999. A simplified version is shown in Table 23.2.

Table 23.2 Simplified classification of periodontal diseases and conditions based broadly on that produced by the International Workshop of the American Academy of Periodontology and the European Federation of Periodontology in 1999

| I | Gingival diseases | |

| II | Chronic periodontitis | |

| III | Aggressive periodontitis | |

| IV | Periodontitis as a manifestation of systemic disease | |

| V | Necrotizing periodontal diseases | |

| VI | Abscesses of the periodontium | |

| VII | Periodontitis in association with endodontic lesions | |

| VIII | Developmental or acquired deformities and conditions | |

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES OF PERIODONTAL DISEASE AND THE ASSESSMENT OF BONE LOSS AND FURCATION INVOLVEMENT

It is beyond the scope of this book to describe the features of all the periodontal diseases and conditions shown in the classification in Table 23.2. Discussion will be restricted to:

Gingival diseases

Radiographs provide no direct evidence of the soft tissue involvement in gingival diseases. However, in severe cases of necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) or acute ulcerative gingivitis (AUG) where there has been extensive cratering of the interdental papilla, inflammatory destruction of the underlying crestal bone may be observed.

Periodontitis

Periodontitis is the name given to periodontal disease when the superficial inflammation in the gingival tissues extends into the underlying alveolar bone and there has been loss of attachment. The destruction of the bone can be either localized, affecting a few areas of the mouth, or generalized affecting all areas. In chronic periodontitis the rate of this progression and subsequent bone destruction is usually slow and continues intermittently over many years, whereas in aggressive periodontitis it is usually rapid. The radiographic features of the different forms of periodontitis are similar; it is the distribution and the rate of bone destruction that varies.

Terminology

The terms used to describe the various appearances of bone destruction include:

The terms horizontal and vertical have been used traditionally to describe the direction or pattern of bone loss using the line joining two adjacent teeth at their cemento-enamel junctions as a line of reference. The amount of bone loss is then assessed as mild, moderate or severe as shown diagrammatically in Figure 23.3.

Fig. 23.3 Diagrams illustrating the various radiographic appearances of periodontitis. A Mild loss of the corticated crestal bone, widening of the periodontal ligament and loss of the normally sharp angle between the crestal bone and the lamina dura. B Moderate horizontal bone loss. C Severe generalized horizontal bone loss with furcation involvement. D Localized vertical bone loss affecting  . E Extensive localized bone loss involving the apex of

. E Extensive localized bone loss involving the apex of  — the so-called perio-endo lesion.

— the so-called perio-endo lesion.

Severe vertical bone loss, extending from the alveolar crest and involving the tooth apex, in which necrosis of pulp tissue is also believed to be a contributory factor, is classified as periodontitis associated with an endodontic lesion, often abbreviated to a perio-endo lesion (see Figs 23.3E and 23.14).

Fig. 23.14 Periapical radiograph showing an extensive area of bone loss (arrowed) associated with  — a so-called perio-endo lesion. The patient had presented clinically with a periodontal abscess.

— a so-called perio-endo lesion. The patient had presented clinically with a periodontal abscess.

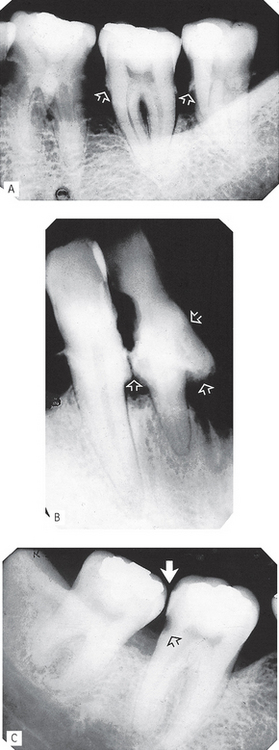

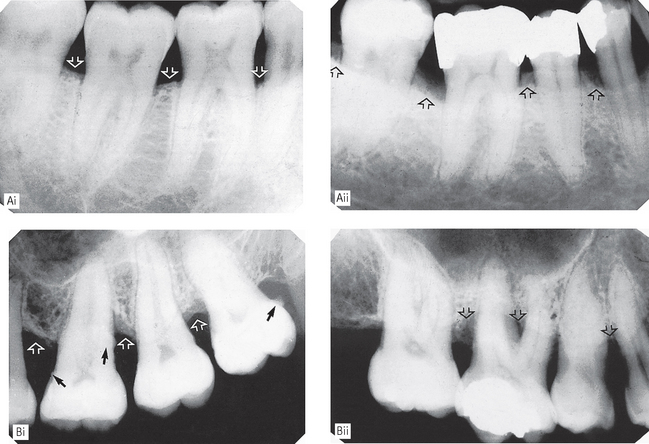

The term furcation involvement describes the radiographic appearance of bone loss in the furcation area of the roots which is evidence of advanced disease in this zone, as shown diagrammatically in Figure 23.4. Although central furcation involvements are seen more readily in mandibular molars, they can also be seen in maxillary molars despite the superimposed shadow of the overlying palatal root. In addition, early maxillary molar furcation involvement between the mesiobuccal or distobuccal roots and the palatal root produces a characteristic triangular-shaped radiolucency at the edge of the tooth (see Figs 23.8C and 23.10A).

Fig. 23.4 Diagrams illustrating the radiographic appearances of varying degrees of furcation involvement in lower molars (arrowed). A Very early involvement showing widening of the furcation periodontal ligament shadow. B Moderate involvement. C Severe involvement.

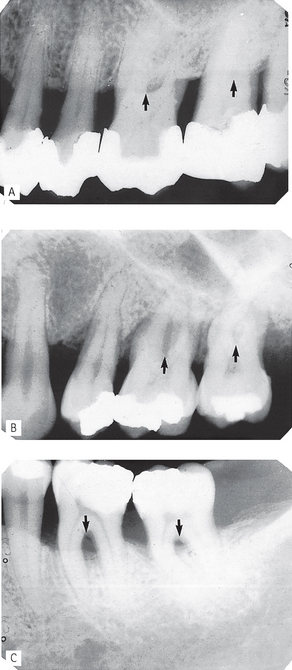

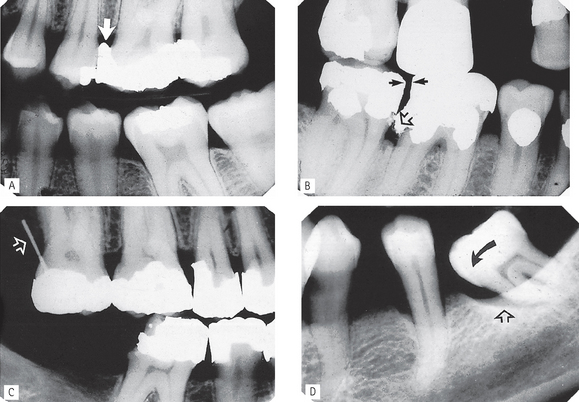

Chronic periodontitis (Figs 23.5—23.11)

This is the most common and important form of periodontal disease, affecting the majority of the dentate and partially dentate population. It is the main cause of loss of teeth in later adult life. The main pathological features of this disease are:

• Inflammation (usually a progression from chronic gingivitis)

• Destruction of periodontal ligament fibers

• Resorption of the alveolar bone

• Loss of epithelial attachment

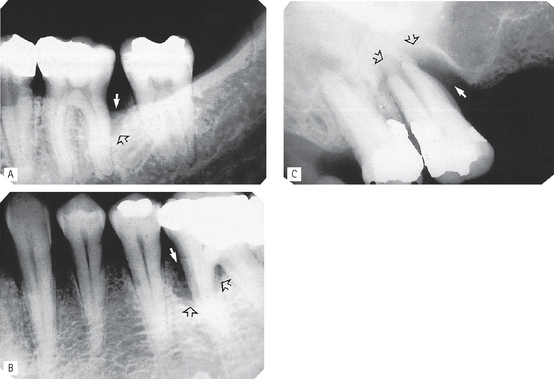

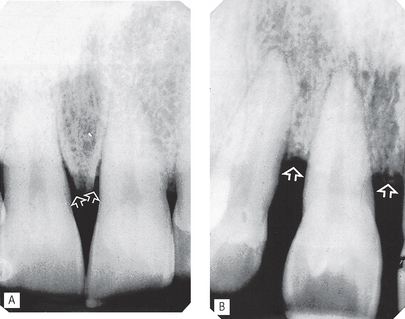

Fig. 23.5 Periapical radiographs showing the typical radiographic features of horizontal bone loss (arrowed) in periodontitis affecting maxillary incisors. A Moderate bone loss. B Severe bone loss.

Fig. 23.6A Right and B Left vertical bitewings showing severe bone loss (open arrows) typical of chronic periodontitis. The black arrows indicate calculus deposits.

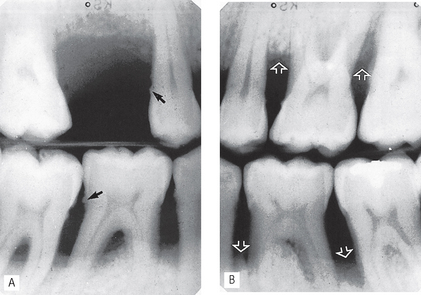

Fig. 23.7 Periapical radiographs showing the typical radiographic features of horizontal bone loss in chronic periodontitis affecting poster teeth. A (i) Early or mild and (ii) moderate bone loss (arrowed) affecting mandibular molars. B (i) Moderate and (ii) severe bone loss (open arrows) affecting maxillary molars. The black arrows indicate calculus deposits.

Fig. 23.9 Periapical radiographs showing A Moderate furcation involvement (black arrows) in maxillary molars. Note the characteristic mesial and distal cervical triangular radiolucent shadows indicating furcation involvement between the mesiobuccal and palatal roots and the distobuccal and palatal roots. B Severe degrees of furcation bone loss (arrowed) in maxillary molars. C Moderate and severe degrees of furcation bone loss (arrowed) in mandibular molars.

Fig. 23.11 Further radiographic examples of secondary local factors. A Overhanging filling ledge. B Defective contact point and overhanging filling ledge. C Pin perforated into the periodontal tissues. D Tilted tooth,

It is the resorption of the alveolar bone that provides the main radiographic features of chronic periodontitis. These include:

• Loss of the corticated interdental crestal margin, the bone edge becomes irregular or blunted

• Widening of the periodontal ligament space at the crestal margin

• Loss of the normally sharp angle between the crestal bone and the lamina dura — the bone angle becomes rounded and irregular

• Localized or generalized loss of the alveolar supporting bone

• Patterns of bone loss — horizontal and/or vertical — resulting in an even loss of bone or the formation of complex intra-bony defects

• Loss of bone in the furcation areas of multirooted teeth — this can vary from widening of the furcation periodontal ligament to large zones of bone destruction

• Widening of the interdental periodontal ligament spaces

• Associated complicating secondary local factors — although the primary cause of periodontal disease is bacterial plaque, many complicating secondary local factors may also be involved. Some of these factors can be detected on radiographs (see Fig. 23.11) and include:

Aggressive periodontitis (Figs 23.12–23.13)

As mentioned earlier, in aggressive periodontitis the progression of the disease and subsequent bone destruction is rapid and can be either generalized or localized. One example is early onset periodontitis which includes localized juvenile periodontitis and prepubertal periodontitis. Radiographic features include:

• Severe vertical bone defects affecting the first molars and/or incisors

• Arch or saucer-shaped defects

• Sometimes the bone loss is more generalized

Abscesses of the periodontium

As was shown in the classification in Table 23.1, abscesses of the periodontium are divided into three groups. These included:

Typically the patient presents with a localized acute exacerbation of underlying periodontal disease, usually originating in deep soft tissue pocket which may have become occluded. The diagnosis of an abscess is made clinically where the signs of acute inflammation and infection are evident. Vitality testing helps to differentiate between the lateral periodontal abscess and the perio-endo lesion. The underlying radiographic bone changes may be indistinguishable from other forms of periodontal bone destruction, as shown in Figure 23.14.

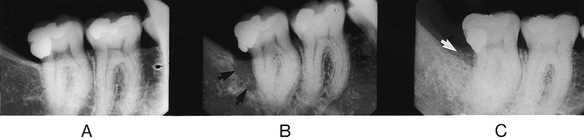

EVALUATION OF TREATMENT MEASURES

Traditional treatment of periodontal disease involves improving oral hygiene, scaling, polishing and root planing of affected teeth surfaces and the removal of any other secondary local factors in an attempt to slow down or arrest the disease process. In recent years, there has been an attempt to achieve the ultimate treatment aim of regeneration of lost tissue by the development of the procedure called guided tissue regeneration. This favours regeneration of the attachment complex to denuded root surfaces by allowing selective regrowth of periodontal ligament cells while excluding the gingival tissues from reaching contact with the root during wound healing. This is achieved by surgically interposing a barrier membrane between the gingiva and the root surface.

The success or otherwise of these treatment measures can be assessed by a combination of clinical examination, including probing and attachment loss measurements, and periodic radiographic investigation, as shown in Figures 23.15 and 23.16. Note: To provide useful information sequential radiographs ideally should be comparable in both technique and exposure factors.

Fig. 23.15 Periapicals showing evaluation of treatment. A Initial film. B 9 years later showing overhanging filling margin and distal bony defect on  (arrowed). C Follow-up film 3 years later following guided tissue regeneration showing the reduced defect (arrowed) and the bone in-fill.

(arrowed). C Follow-up film 3 years later following guided tissue regeneration showing the reduced defect (arrowed) and the bone in-fill.

(Kindly supplied by Dr A. Sidi.)

Fig. 23.16 Periapicals showing evaluation of treatment. A Preoperative film showing a perio-endo lesion affecting  with severe bony defect on the mesial aspect of the root (arrowed). B Follow-up film 2 years later following successful endodontic therapy and guided tissue regeneration. Note the reduced bony defect (arrowed).

with severe bony defect on the mesial aspect of the root (arrowed). B Follow-up film 2 years later following successful endodontic therapy and guided tissue regeneration. Note the reduced bony defect (arrowed).

(Kindly supplied by Dr A. Sidi.)

LIMITATIONS OF RADIOGRAPHIC DIAGNOSIS

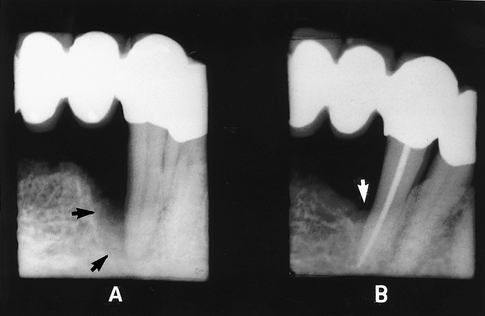

Radiographic evaluation of the periodontal tissues is somewhat limited. The main limitations include:

• Superimposition and a two-dimensional image bringing about the following problems:

• Information is provided only on the hard tissues of the periodontium, since the soft tissue gingival defects are not normally detectable.

• Bone loss is detectable only when sufficient calcified tissue has been resorbed to alter the attenuation of the X-ray beam. As a result, the histological front of the disease process cannot be determined by the radiographic appearance.

• Technique variations in image receptor and X-ray beam positions can affect considerably the appearance of the periodontal tissues; hence the need for accurate, reproducible techniques as described in Chapter 11.

• Exposure factors can have a marked effect on the apparent crestal bone height — overexposure causing burn-out when using film-based imaging.

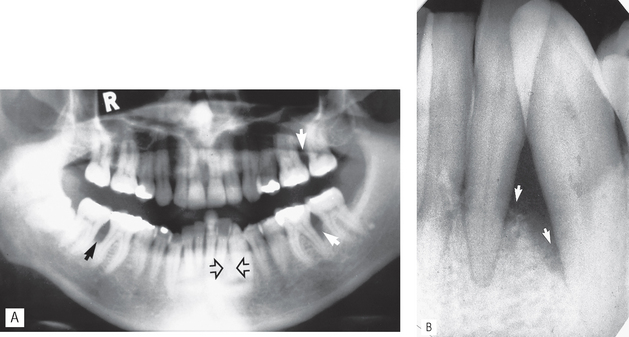

• Complete reliance cannot be placed on the inherently inferior images of dental panoramic radiographs although they do provide a reasonable overview of the periodontal status (see Fig. 23.17 and Ch. 17).

• Some of the limitations of two-dimensional conventional radiography, in visualizing three-dimensional periodontal bone defects, can be overcome by high resolution cone beam CT (see Ch. 19).

Fig. 23.17A Panoramic radiograph showing bony defects in the molar regions (arrowed) but no evidence of a similar defect in the  region (open arrows) owing to superimposition of the radiopaque artefactual shadow of the cervical vertebrae. B Periapical of

region (open arrows) owing to superimposition of the radiopaque artefactual shadow of the cervical vertebrae. B Periapical of  region taken at the same time showing the severe bony defect (arrowed) that was actually present.

region taken at the same time showing the severe bony defect (arrowed) that was actually present.