Chapter 32 Bone diseases of radiological importance

INTRODUCTION

There are many diseases and abnormalities of bone. Some are localized to the jaws while others can affect the whole skeleton. It is beyond the scope of this book to consider them all. This chapter summarizes a somewhat diverse, but important group of bone conditions which can affect the facial skeleton and which are of radiological importance.

Unfortunately, several of the bone diseases described, although totally different in nature, can present very similar appearances radiographically. To differentiate them, clinicians need to consider all relevant factors including — the age of the patient, the distribution of the disease (whether it is generalized or localized) and which bones are involved, as well as noting the specific radiographic features.

Using the atlas approach adopted in Chapter 25, an example of each of the conditions is shown together with a summary of the main radiographic features seen in the skull and facial skeleton. It is worth remembering that bone is a constantly changing, dynamic tissue. Thus diseases of bone can present a spectrum of radiographic appearances depending on the behaviour and maturity or stage of the disease and/or lesion(s). The examples shown represent only a small part of that spectrum.

DEVELOPMENTAL OR GENETIC DISORDERS

Cleidocranial dysplasia

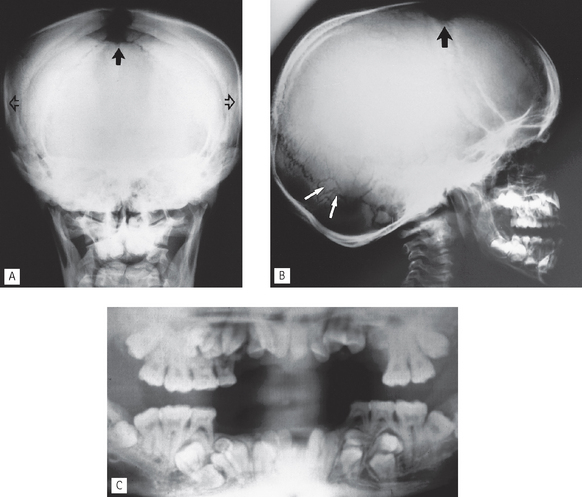

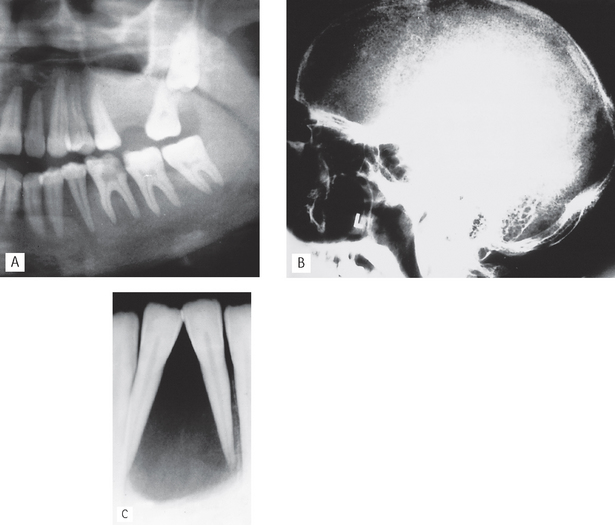

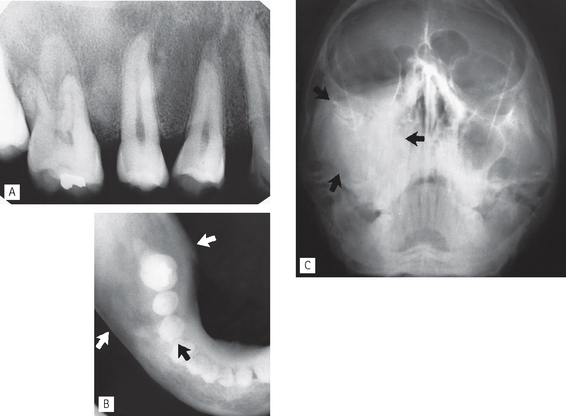

This is a rare developmental disturbance affecting the skull and clavicles. The abnormalities of dentition can be gross but usually affect only the permanent teeth. Examples are delayed eruption and multiple supernumeraries (see Fig. 32.1).

Fig. 32.1 Cleidocranial dysplasia. A PA skull showing the cranial features of widened cranium (open arrows) and open fontanelle (solid arrow). B True lateral skull of another patient also showing the open fontanelle (black arrow) and also small wormian bones (white arrows). The enlargement of the occiput is also obvious. C Panoramic radiograph showing the dental anomalies of delayed eruption and multiple supernumerary teeth.

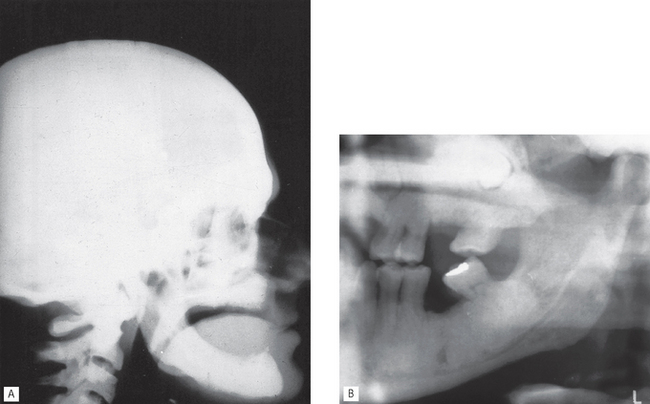

Osteopetrosis (Albers-Schönberg disease)

This hereditary disease is characterized by sclerosis of the skeleton (so called marble bones), fragile bones and secondary anaemia. Bone formation is normal but bone resorption is reduced, resulting in the presence of excessive calcified tissue and lack of marrow space (see Fig. 32.2). Cranial base changes may produce compression of the cranial nerves.

Fig. 32.2 Osteopetrosis. A True lateral skull showing the cranial features of radiopaque, dense vault and thickened base. B Left side of a panaromic radiograph showing loss of the normal trabecular pattern and replacement with dense thickened bone.

Main radiographic features

• Occasional involvement of the jaws. This involvement is always bilateral and includes:

INFECTIVE OR INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

Osteomyelitis

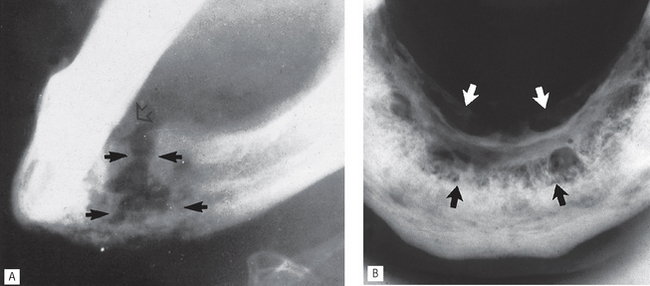

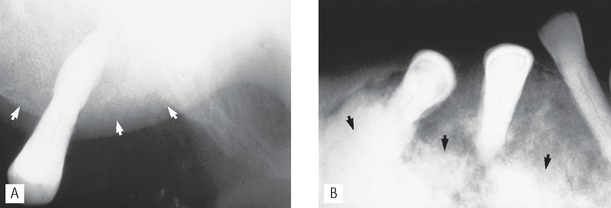

This spreading, progressive inflammation of bone and bone marrow, more frequently affects the mandible than the maxilla. It is caused usually by local factors such as periapical infection, pericoronitis, acute periodontal lesions, extractions or trauma. The inflammatory response may be acute or chronic depending on the virulence of the infecting organism and the resistance of the patient. It results ultimately in the destruction of the infected bone (see Fig. 32.3). The reaction of the surrounding bone and periosteum is very variable and often age-related. There may be surrounding sclerosis of the bone forming poorly-defined patchy opacity. Sequestra (small pieces of necrotic bone) can be exfoliated over a period of several weeks. The periosteum around the affected area can lay down new bone (the so-called periosteal reaction). In children this can be pronounced and is described as proliferative periostitis. This typically affects the mandible in young girls, following apical or pericoronal infection associated with the lower first molar producing a non-tender, bony hard swelling of the lower border. Radiographically the proliferative periostitis results in a laminated, so called onion-skin, appearance (see Fig. 32.3D)

Fig. 32.3 Osteomyelitis. A Oblique lateral of the mandible showing typical ragged or moth-eaten radiolucent areas of bone destruction (solid arrows) and a sequestrum of dead bone (open arrow). B Lower 90° occlusal showing irregular bone destruction (black arrows) and lingual involucrum formation (white arrows).

C Oblique lateral showing chronic dense sclerosing osteomyelitis (arrowed). D Proliferative periostitis-oblique lateral of a 9-year-old girl showing bone destruction around the first molar and the onion-skin layering periosteal reaction affecting the lower border (arrowed). E Part of a lower occlusal showing another example of onion-skin layering periosteal new bone formation.

Main radiographic features of acute osteomyelitis

• Ragged, patchy or moth-eaten areas of radiolucency — the outline of the area of destruction is irregular and poorly defined

• Evidence of small radiopaque sequestra of dead bone occasionally within the radiolucency

• Evidence of new subperiosteal bone formation, usually beyond the area of necrosis, particularly along the lower border of the mandible.

Main radiographic features of chronic osteomyelitis

• Localized patchy or moth-eaten areas of bone destruction

• Sclerosis of the surrounding bone

• Evidence of small radiopaque sequestra of dead bone sometimes within the area of bone destruction

• Evidence of an involucrum surrounding the area of destruction following extensive subperiosteal bone formation.

Note: The radiographic appearance of osteomyelitis varies considerably depending on the type of underlying inflammatory response and the age of the patient.

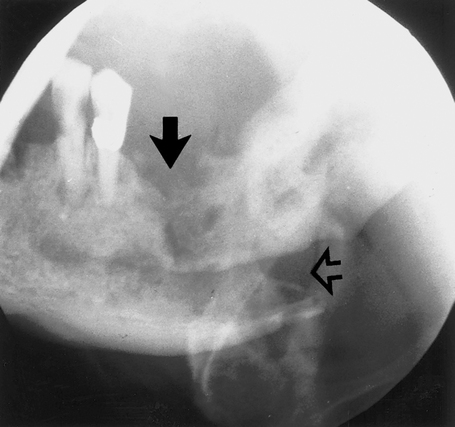

Osteoradionecrosis

The high doses of radiation used in radiotherapy reduce drastically the vascularity and reparative powers of bone. The mandible is particularly susceptible. Subsequent trauma (e.g. tooth extraction) or infection may produce osteomyelitis with rapid destruction of the irradiated bone, sequestra formation and poor healing. Radiographically osteoradionecrosis resembles other types of osteomyelitis, although the border between necrotic and normal bone may be more sharply defined and subperiosteal new bone formation is not usually evident (see Fig. 32.4). A history of radiotherapy enables the differential diagnosis to be made.

HORMONE-RELATED DISEASES

Hyperparathyroidism

Primary hyperparathyroidism, caused by either hyperplasia or an adenoma of the parathyroids, or secondary hyperparathyroidism caused by kidney disease, results in increased secretion of parathormone. This causes generalized skeletal bone resorption leading to osteopenia (generalized decrease in bone density), bone pain or even pathological fracture and raises the plasma calcium levels (see Fig. 32.5). Localized cyst-like central giant cell lesions (brown tumours) can also develop in the jaws and long bones. The term osteitis fibroa cystica is used to describe severe chronic skeletal hyperparathyroidism following brown tumour degeneration and fibrosis.

Fig. 32.5 Hyperparathyroidism. A Left side of a panoramic radiograph showing the typical bone changes including loss of the lamina dura, fine ground glass trabecular pattern, and thinning of the cortical bone of the lower border and inferior dental canal. B True lateral skull showing the pepper-pot appearance in the skull vault. C Periapical showing a radiolucent central giant cell lesion (brown tumour) between the lower incisors which have been displaced but not apparently resorbed.

Main radiographic features

• Evidence in the skull vault of osteopenia producing a fine overall stippled pattern to the bone — hence the description pepper-pot skull

Acromegaly

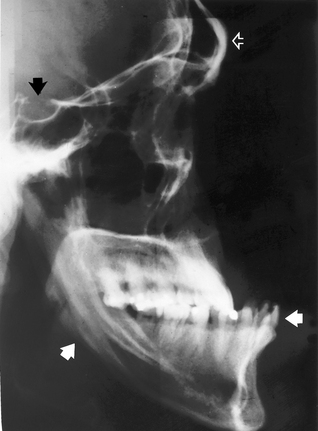

This is a disturbance of bone growth caused by hypersecretion of growth hormone (GH) usually as the result of a pituitary adenoma developing after puberty. Characteristic features include renewed growth of certain bones, particularly the jaws, hands and feet, and overgrowth of some soft tissues (see Fig. 32.6).

Fig. 32.6 Acromegaly — true lateral skull showing frontal bossing (open white arrow), enlarged pituitary fossa (black arrow), grossly enlarged and prognathic mandible with increased obliquity of the angle (solid white arrows).

BLOOD DYSCRASIAS

Sickle cell anaemia

This hereditary, chronic, haemolytic blood dis-order affects principally black populations. It is characterized by abnormal haemoglobin which results in fragile erythrocytes which become sickle-shaped under conditions of hypoxia. These abnormal red blood cells have a decreased capacity to carry oxygen and are destroyed rapidly producing anaemia.

In homozygotes, the radiographic changes reflect the haemopoietic system’s response to the anaemia including:

• Increased production of red blood cells and hyperplasia of the bone marrow at the expense of the cancellous bone

• Bone infarcts (see Fig. 32.7).

Fig. 32.7 Sickle cell anaemia. A True lateral skull showing widening of the diploic space and thinning of the inner and outer tables and early hair-on-end appearance anteriorly (arrowed). B Periapical showing the generalized coarse trabecular pattern in the mandible.

Main radiographic features

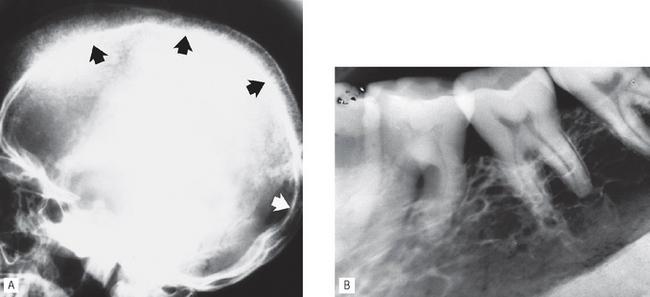

Thalassaemia (Cooley’s anaemia)

This hereditary haemoglobinopathy is characterized by chronic haemolytic anaemia and mainly affects people from the Mediterranean area. The defect lies in an inability to make enough normal globin chains thus creating abnormal red blood cells which have a shortened life expectancy. Again the radiographic features result from the bone marrow proliferation required to produce more red blood cells with subsequent remodelling of all affected bones (see Fig. 32.8).

Fig. 32.8 Thalassaemia. A True lateral skull showing pronounced hair-on-end appearance (black arrows) and involvement of the maxilla with obliteration of the antra. B Panoramic radiograph showing the altered trabecular pattern throughout the mandible and maxilla with very large marrow spaces, obliteration of the antra and thinning of the lower border cortex.

(Kindly supplied by Mrs J.E. Brown.)

DISEASES OF UNKNOWN CAUSE

Fibrous dysplasia

As mentioned in Chapter 28, fibrous dysplasia is categorized as a bone-related lesion in the WHO 2005 Classification. It is described by the WHO as a genetically-based sporadic disease of bone affecting single or multiple bones. It usually develops in childhood and is manifest before the age of 10. It is characterized by the proliferation of fibrous tissue and resorption of normal bone in one or more localized areas, and subsequent replacement with poorly formed, haphazardly arranged new bony trabeculae. Clinical varieties include:

• Monostotic fibrous dysplasia, characterized by a lesion affecting a single bone, including the jaws, particularly the posterior part of the maxilla (see Fig. 32.9).

• Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, characterized by multiple bone lesions and subdivided into:

Fig. 32.9 Fibrous dysplasia. A Periapical showing the overall fine stippled trabecular pattern (orange peel), and loss of the lamina dura around the  . B Lower 90° occlusal centred on the right side again showing the ground glass appearance and expansion but involving the mandible in the premolar and molar regions (arrowed). The anterior part of the mandible is unaffected. C 0° OM showing expansion of the right posterior maxilla spread into the zygoma and total obliteration of the right antrum (arrowed).

. B Lower 90° occlusal centred on the right side again showing the ground glass appearance and expansion but involving the mandible in the premolar and molar regions (arrowed). The anterior part of the mandible is unaffected. C 0° OM showing expansion of the right posterior maxilla spread into the zygoma and total obliteration of the right antrum (arrowed).

Main radiographic features of monostotic fibrous dysplasia affecting the jaws

• A localized rounded zone of relative radio-lucency containing a variety of fine trabecular patterns, described as ground glass, fingerprint and orange peel. The more mature the lesion the more radiopaque it appears.

• Poor definition of the edge of the lesion which merges imperceptibly with the surrounding normal bone (see Fig. 28.18).

• Loss of the lamina dura with thinning of the periodontal ligament shadow.

• Enlargement of the affected bone.

• In the maxilla encroachment on, or obliteration of, the antrum and spread into particularly the zygoma and sphenoid bones of the cranial base.

• Associated teeth occasionally displaced, but rarely resorbed.

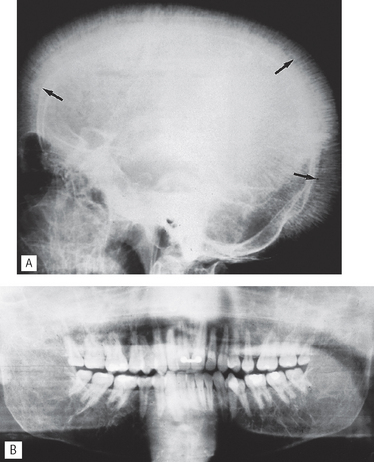

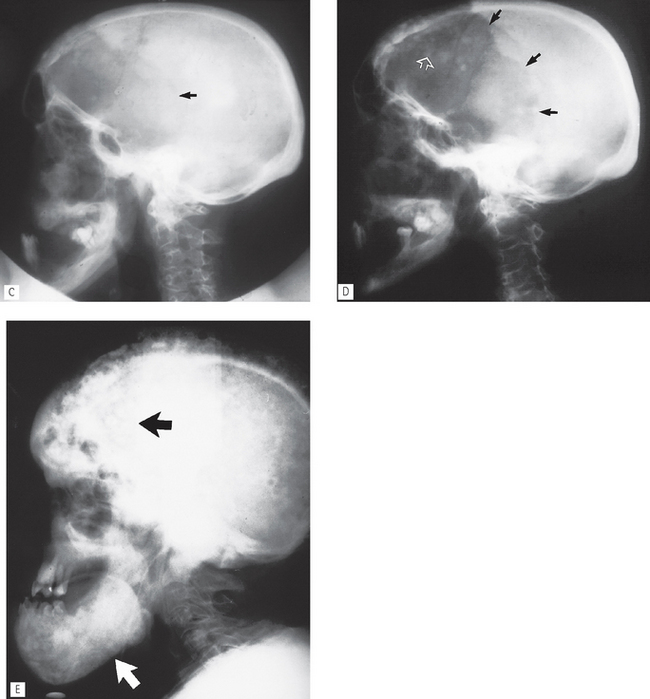

Paget’s disease of bone (osteitis deformans)

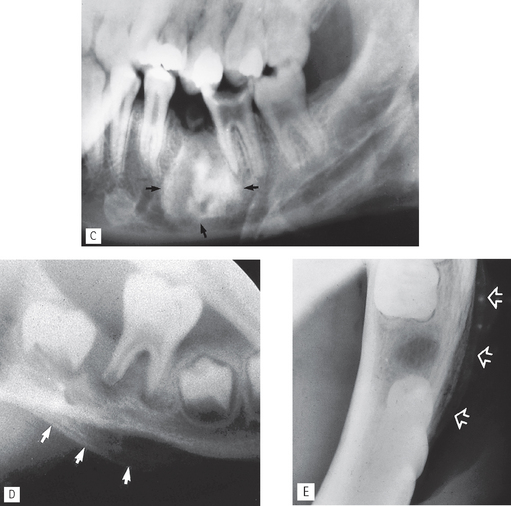

In this disease of the elderly, the normal processes of bone deposition and resorption are disturbed severely, but only in certain bones and usually symmetrically. The main features are an enlarged head and thickening of the affected long bones which bend under stress. Typically the early stages of the disease are characterized by bone resorption and the later stages by bone deposition, although there is no clear-cut distinction between the two stages (see Fig. 32.10).

Fig. 32.10 Paget’s disease of bone. A Periapical showing the early porotic stage in the maxilla; note the overall fine trabecular pattern (ground glass), loss of the lamina dura and enlargement of the maxilla (arrowed). B Periapical showing the typical late stage in the mandible. Note the cottonwool patches of sclerotic bone (arrowed), loss of the lamina dura, enlargement of the bone, malposition of the teeth and the associated hypercementosis.

C True lateral skull showing early cranial vault involvement — the frontal region appears radiolucent and the scalloped line of osteoporosis circumscripta is arrowed. D Same patient 12 months later — the scalloped line of osteoporosis circumscripta has progressed posteriorly (black arrows) and there is early haphazard deposition of bone in the frontal region (open white arrow). E True lateral skull of a different patient showing the typical late stage appearance of cottonwool patches affecting the frontal region of the skull vault (black arrows) and the mandible (white arrow). The occipital region is still in the early stages.

Main radiographic features of early-stage Paget’s disease

• In the skull vault scalloped, circumscribed zones of osteoporosis spreading gradually across the calvarium, described as osteoporosis circumscripta

• Involvement of the maxilla and/or the mandible. If either is involved, the whole of the bone concerned shows radiographic changes which include:

, showing the typical destructive appearance (solid arrow), which has resulted in a pathological fracture (open arrow). Radiotherapy had been given several years previously.

, showing the typical destructive appearance (solid arrow), which has resulted in a pathological fracture (open arrow). Radiotherapy had been given several years previously.