Pain

The material in this chapter will help you to:

describe a biopsychosocial model of pain

describe a biopsychosocial model of pain

explain the difference between nociceptive and neuropathic pain and the role of central sensitisation

explain the difference between nociceptive and neuropathic pain and the role of central sensitisation

explain the roles of beliefs, fear avoidance, distress, pain behaviour, coping strategies, learning and environment in a chronic pain presentation

explain the roles of beliefs, fear avoidance, distress, pain behaviour, coping strategies, learning and environment in a chronic pain presentation

explain the difference between acute and chronic pain and describe some of the factors that can contribute to the transition from acute to chronic

explain the difference between acute and chronic pain and describe some of the factors that can contribute to the transition from acute to chronic

list the main biomedical interventions for pain and describe the components of a cognitive-behavioural approach to managing pain

list the main biomedical interventions for pain and describe the components of a cognitive-behavioural approach to managing pain

understand that in the case of chronic pain the treatment goal shifts from trying to reduce or eliminate the pain to learning to live with the pain and return to normal activities and function despite the pain.

understand that in the case of chronic pain the treatment goal shifts from trying to reduce or eliminate the pain to learning to live with the pain and return to normal activities and function despite the pain.

Introduction

Pain is an important issue for all health professionals to be aware of. It accompanies most health presentations and is commonly understood to be a warning system signifying the need for immediate attention. Our response to it as health professionals can have a significant impact on outcome in terms of gaining the trust and cooperation of our patients, and making the appropriate decisions for management.

Pain is a multifactorial experience with sensory and emotional aspects and it is best understood within a biopsychosocial framework. Although we now have a much better understanding of the neurobiological basis of pain, the lack of direct correlation between actual injury or pathology and reported pain and pain behaviour can only be understood when all aspects of the presentation are taken into account. Psychological and environmental factors can play a particularly important role in the transition from acute to chronic pain and its ongoing maintenance. Given that approximately one in five adults may suffer from chronic pain (Blyth et al 2001) and that biomedical interventions have limitations, understanding and managing all aspects of such a presentation is essential.

What is pain?

Most of us think we know exactly what pain is through our own experience and most of us would assume that pain is clearly linked to injury. Moreover, many of us would further believe that the intensity of pain is somehow proportional to the severity of the injury that has occurred. In fact, these seemingly obvious assumptions are not simply incorrect but misleading in terms of allowing health professionals to best assist patients in assessing and managing pain.

A comprehensive overview of the history of pain concepts and treatments can be found in Cope (2010). Here you will see that pain in different eras and different cultures has been viewed both as a sensation and therefore tied to the stimulus (or injury) and as an experience with strong emotional features (e.g. a quality or passion of the soul or a form of punishment). The former view is more consistent with commonly held contemporary views of pain, especially in the Western world. However, for researchers and health professionals working in the area of pain, it has become increasingly obvious that pain is not adequately explained by linking it to a noxious stimulus. A brief paper by Wall and McMahon (1986) clearly outlines that the evidence of a relationship between perceived pain and the firing of specific types of nerve fibres, or nociception, is not simply variable but sometimes nonexistent. Melzack and Wall (1982) provide an excellent overview of the variability of this relationship, discussing a range of phenomena, for example, congenital analgesia (people who are born without the ability to feel pain and therefore have no automatic warning system of injury), episodic analgesia (the inability to feel pain in certain situations such as when trying to survive on the battlefield), phantom limb pain (the experience of pain in a limb that does not exist) and, most commonly of all for many people in our society, the persistence of pain long after the healing of whatever injury was associated with its onset.

The important points to note from the above are that pain is not nociception. Nociception is simply activity in the nervous system generated by a noxious stimulus and it is quite possible for this to take place without any conscious awareness, such as when one is under anaesthetic. Pain, on the other hand, is a conscious, subjective experience with a number of dimensions.

This more complex understanding of what pain is has led to the following definition of pain from the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) Task Force on Taxonomy (1994), that it is ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage’.

The following notes provided by the task force clearly emphasise the understanding that pain has a strong subjective, emotional component and that tissue damage can only be a poor guide to what the person may or may not be experiencing.

Pain is always subjective. Each individual learns the application of the word through experiences related to injury in early life … It is unquestionably a sensation in a part or parts of the body but it is also always unpleasant and therefore also an emotional experience.

Many people report pain in the absence of tissue damage or any likely pathophysiological cause; usually this happens for psychological reasons. There is usually no way to distinguish their experience from that due to tissue damage if we take the subjective report. If they regard their experience as pain and if they report it in the same ways as pain caused by tissue damage, it should be accepted as pain. This definition avoids tying pain to the stimulus. Activity induced in the nociceptor and nociceptive pathways by a noxious stimulus is not pain, which is always a psychological state, even though we may well appreciate that pain most often has a proximate physical cause.

(IASP 1994 p 210)

The biopsychosocial model of pain

The biopsychosocial model was discussed in Chapter 4. There it was pointed out that health or illness is influenced by a complex interplay of biological, psychological and social factors. In terms of understanding and providing a formulation of the experience of pain, the biopsychosocial model has been widely accepted by health professionals as providing the best possible template to assess and manage the presentation of pain. Given the IASP definition cited above that describes pain as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience, this of course makes perfect sense.

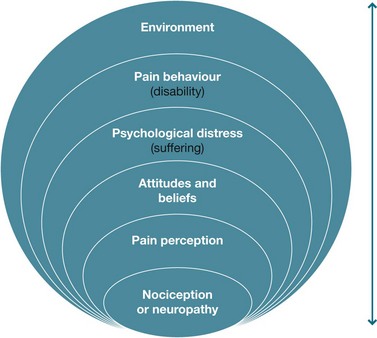

The biopsychosocial model originally delineated by Engel (1977) has been applied to pain by a number of important researchers in the field, including Fordyce (1976), Loeser (1982) and Waddell et al (1984).The broad components of the model are essentially the same in all versions and are elaborated in Figure 12.1. These components will be discussed in turn below but it is important to note that at all levels every component can impact on another level, in both directions. Therefore changes at the physiological level initiated by trauma may have impact at the psychological and behavioural levels in terms of distress and/or avoidance of activity but equally changes at the psychological or behavioural level can, in turn, have an impact at the physiological level, such as physical deconditioning (Turk & Monarch 2002).

Figure 12.1 Biopsychosocial model of pain Source: Drawn from Fordyce 1976, Loeser 1982 and Waddell et al 1984

Nociception or neuropathy

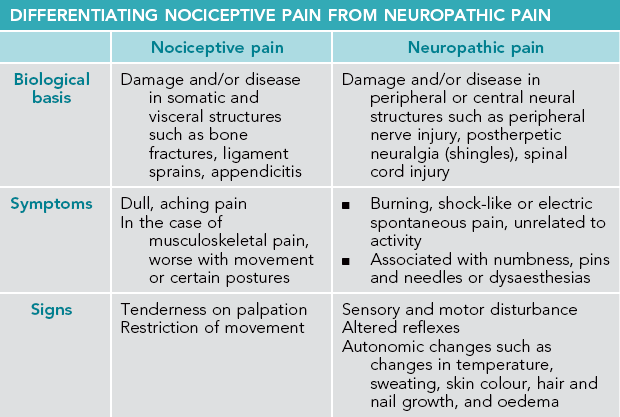

When considering the biological contributors to the experience of pain, we can divide pain into two types – nociceptive and neuropathic – depending on the structures and mechanisms involved. Pain can further be classified clinically as acute or chronic. These distinctions are important because different types of pain, with different characteristics and underlying mechanisms, have different responses to treatment.

Nociceptive pain

According to the IASP, nociceptive pain refers to pain arising from actual or threatened damage to non-neural structures and is due to the activation of nociceptors (Turk & Okifuji 2010). Nociceptive pain is generally described as aching or dull and, in the case of musculoskeletal pain, usually related to activity or posture. For example, soft tissue sprains and strains, bone fractures and appendicitis may give rise to nociceptive pain.

Neuropathic pain

Neuropathic pain refers to pain arising as a direct consequence of a lesion or disease of the somatosensory system (Turk & Okifuji 2010). Neuropathic pain is confined to a region of sensory disturbance that is consistent with the distribution of the affected peripheral nerve, root or central pathway, and is often described by patients as burning or shock-like (Haanpää et al 2011). Episodes of neuropathic pain can occur spontaneously or as an exaggerated response to minor stimulation. An exaggerated response to a non-painful stimulus, such as light touch, is called allodynia. An exaggerated response to a painful stimulus is called hyperalgesia. Patients with neuropathic pain may also describe dysaesthesias, which are unpleasant and strange sensations in the skin such as ants crawling, water running, tingling, and pins and needles (Freynhagen & Bennett 2009). Neuropathic pain may occur following traumatic nerve injury, multiple sclerosis or spinal cord injury (Haanpää & Treede 2010). Postherpetic neuralgia and diabetic polyneuropathy may also give rise to neuropathic pain (Haanpää et al 2011). Depending on the site of the lesion, other symptoms may occur, such as muscle cramps, autonomic nerve damage symptoms and motor weakness (Haanpää & Treede 2010).

This current definition distinguishes neuropathic pain from pain arising as a consequence of neuroplastic changes, as in central sensitisation (see section below on pain processing), which occur in response to strong nociceptive stimulation (Haanpää et al 2011). For example, in a patient who presents with deep aching pain in the hypothenar region of the hand, intermittent stabbing pain without obvious triggers, and the fact that this pain initiated after an injury to the area, is suggestive of an ulnar nerve lesion (Geber et al 2009). A clinical examination that finds sensory disturbance consisting of negative (hypoaesthesia or reduced sensation) and/or positive sensory signs (hyperalgesia and allodynia) would confirm a diagnosis of neuropathic pain (Geber et al 2009). Alternatively, a patient presenting with depression and widespread pain that could not be apportioned to an anatomically defined nervous system lesion, and who had a normal sensory examination with no suggestion of neurologic disease or neural damage, is unlikely to be experiencing neuropathic pain but might fulfill the criteria for fibromyalgia (Geber et al 2009).

Mixed pain

It is worth noting that, in many patients, neuropathic and nociceptive pains coexist and it is therefore important that clinicians identify these different components and treat them according to the best available evidence (Haanpää & Treede 2010) (see Table 12.1). For example, a patient presenting with low back and leg pain may have referred pain from a degenerative facet joint and/or sciatica from irritation or compression of a lumbar nerve root. A diagnosis of definite neuropathic pain would depend on a history of pain radiating along the leg, a positive MRI scan and an altered somatosensory examination (i.e. hypoaesthesia, hyperalgesia and allodynia) within the distribution of the affected nerve root.

Pain processing in the peripheral and central nervous systems

Understanding the nature of pain has consumed humankind throughout the ages. During the 19th and 20th centuries, advances in the study of anatomy, physiology and histology prompted the formulation of several physiologic theories of pain. Of these, the gate control theory (Melzack & Wall 1965) was the most influential and the first attempt to combine neurophysiological mechanisms with psychological processes such as cognitions and emotions. In this model, pain was viewed as an end product of a number of interacting processes in which the central nervous system played an active role in determining the nature and degree of pain following harmful stimulation in the periphery. Although we now know that this theory is overly simplistic, it nevertheless provides us with an understanding of the types of mechanisms involved in the processing and modulation of the experience of pain.

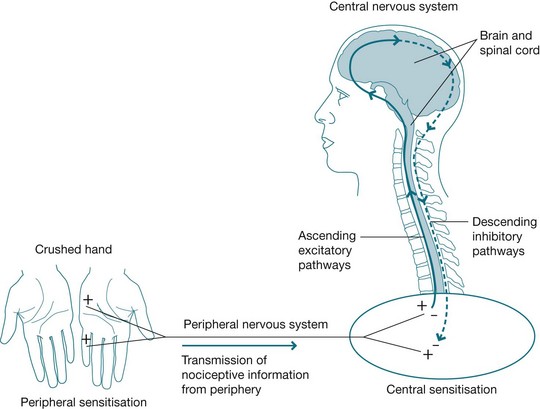

A simple explanation of the nervous system changes that occur in response to pain is that injury, disease or inflammation in tissues activates local nociceptor terminals to transmit information about physical damage to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. These nociceptors become sensitised by the release of chemicals from the damaged tissue and by the release of neurotransmitters from sensory nerve endings. This process is called peripheral sensitisation and is responsible for primary hyperalgesia or increased sensitivity to mechanical and thermal stimulation at the site of injury or pain. Once noxious information reaches the spinal cord, it is modulated by cells within the spinal cord and by the activation of descending pathways from the brain, which might be either inhibitory or excitatory. Continued transmission of noxious information from the periphery leads to a cascade of events within the central nervous system (spinal cord and brain) that contribute to an increase in responsiveness of central neurons. This is known as central sensitisation.

In the case of neuropathic pain following peripheral nerve injury, the peripheral processes of nociceptors can become traumatised and undergo numerous changes that lead to increased activation of peripheral and central pain circuits that sometimes become chronic and debilitating. As noted above, allodynia, hyperalgesia, dysaesthesias and spontaneous pain are common features of neuropathic pain and are mediated by central sensitisation.

Under normal conditions central sensitisation resolves following recovery. In some cases, however, central changes persist and symptoms associated with these changes are seen in pathological pain states such as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), failed back surgery syndrome and phantom limb pain.

From the spinal cord, noxious signals reach the brain via a number of ascending tracts that terminate in many structures throughout the brainstem, thalamus and cortex (Woolf 2011). The thalamus acts as a major relay station in the transmission of noxious signals. As these signals reach the brain, many other regions are also activated, including those that control a number of autonomic and homeostatic mechanisms such as blood pressure regulation and respiration (Woolf 2011). In addition, there are descending mechanisms mediated by a variety of neurotransmitters, acting at subcortical and spinal cord levels, modulating ascending information (Randich & Ness 2010).

The higher brain centres used in pain processing can be divided into those involved in the sensory-discriminative component of pain perception (somatosensory cortex) and the affective component of pain perception (such as the cingulate cortex). However, this may be an oversimplification. Functional imaging studies have now identified a widely distributed network of cortical and subcortical areas that are activated by noxious stimuli (Apkarian et al 2011). These include sensory, limbic, associative and motor areas. Functional imaging studies have also shown significant differences in brain activation between people with no pain, acute pain and chronic pain (Apkarian et al 2011). Figure 12.2 shows the mechanisms of pain.

Pain perception

Pain does not occur in isolation but, rather, within a context that has a direct bearing on the person's perception of pain and on their response to pain. A person's subjective perception of pain may be viewed as the net result of transduction (the conversion of energy from the initiating stimulus into an electric signal), transmission (the propagation of action potentials from the peripheral nerve terminal to the central terminal) and modulation of sensory information (Turk et al 2010). Some modulatory effects are predictable and reliable, while others are less predictable, being dependent on psychological/cognitive processes that may involve learning, motivation and emotional status (Randich & Ness 2010). Pain can be extremely variable; it can attain intolerable intensity, persist beyond tissue healing or disappear on the battlefield. The way we interact with our environment is significantly altered by pain and our behaviour changes over time as pain continues. Therefore, in order to fully understand a person's perception and response to pain, a biopsychosocial approach is required, with consideration given to the interrelationships between the biological changes, psychological status and the sociocultural context in which pain occurs (Turk et al 2010).

Given that pain is an experience that is modulated by a complex set of emotional, environmental and psychophysiological variables, one would expect pain to influence brain processing on many levels (Apkarian et al 2011). Consideration of the neural representations of pain processing should therefore also include the neural representations of the mechanisms involved in pain modulation (including the role of learning, meaning, attention, anticipation and avoidance). A number of research techniques have been used to study these representations:

injection of dyes or markers into nerves or supraspinal structures to allow researchers to trace their pathways

injection of dyes or markers into nerves or supraspinal structures to allow researchers to trace their pathways

immunohistochemical techniques to study changes in gene expression in neurons following noxious stimulation

immunohistochemical techniques to study changes in gene expression in neurons following noxious stimulation

functional neuroimaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to detect changes in regional blood flow or changes in local blood oxygen levels that coincide with changes in local functional brain activity in pain versus non-pain states (e.g. Apkarian et al 2011)

functional neuroimaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to detect changes in regional blood flow or changes in local blood oxygen levels that coincide with changes in local functional brain activity in pain versus non-pain states (e.g. Apkarian et al 2011)

anatomical imaging using voxel-based morphometry (VBM) to study the anatomical changes that occur in the brain of patients with chronic pain (e.g. Ruscheweyh et al 2011).

anatomical imaging using voxel-based morphometry (VBM) to study the anatomical changes that occur in the brain of patients with chronic pain (e.g. Ruscheweyh et al 2011).

In recent years, human functional brain imaging has added significantly to our knowledge of where and how pain is processed in the brain (Apkarian et al 2011). As pointed out earlier, the processing of pain can no longer be viewed as a simple ‘hard-wired’ system with a strong relationship between stimulus and response (Cope 2010). We now have a better understanding of the neuroplastic changes that occur within the central nervous system in the presence of pain and hence the changes that should be addressed as part of an integrative approach to pain management (Tracey & Bushnell 2009).

Attitudes and beliefs

What the pain means to a particular person at a particular time will have a clear influence on how that person subsequently responds. For example, if a person wakes in the night with stomach pain, he or she may think ‘I should not have eaten so much’, groan, roll over and eventually fall back to sleep. However, if they think that the pain may be an indicator of stomach cancer, perhaps because they saw a program on television about stomach cancer the previous evening or because they have a close relative with that disease, they are then likely to begin monitoring the pain, become worried and distressed, be unable to fall back to sleep and so on. Pain can sometimes be accepted as a necessary accompaniment to another valued goal such as in childbirth or in the pursuit of sporting success. It can even be pursued for pleasure as in certain sexual practices. Chapman and Okifuji (2004) discuss three main cognitive factors that will influence the pain experience:

The degree of attention paid to the pain modulates the pain experience such that a person is likely to experience less pain if their attention is actively engaged elsewhere. People who report greater attention to pain have been shown in a number of studies to also report higher pain intensity, emotional distress, psychosocial disability, and pain-related healthcare utilisation (e.g. McCracken 1997).

The degree of attention paid to the pain modulates the pain experience such that a person is likely to experience less pain if their attention is actively engaged elsewhere. People who report greater attention to pain have been shown in a number of studies to also report higher pain intensity, emotional distress, psychosocial disability, and pain-related healthcare utilisation (e.g. McCracken 1997).

Expectations about pain – a number of studies have demonstrated that when expectations about pain are manipulated the level of pain changes. Expectations in this context can refer to ‘response expectancies’ or the response a person predicts they will have to a certain stimulus, for example, a pain medication or an activity. Response expectancies have a significant impact on actual pain experience. For example, Whalley et al (2008) showed that placebo effects were significantly associated with response expectancy.

Expectations about pain – a number of studies have demonstrated that when expectations about pain are manipulated the level of pain changes. Expectations in this context can refer to ‘response expectancies’ or the response a person predicts they will have to a certain stimulus, for example, a pain medication or an activity. Response expectancies have a significant impact on actual pain experience. For example, Whalley et al (2008) showed that placebo effects were significantly associated with response expectancy.

Expectations can also refer to ‘efficacy expectancies’ (e.g. self-efficacy) or a person's confidence that they have the ability to cope with pain or an activity. Self-efficacy has been shown to predict pain behaviour and avoidance (Asghari & Nicholas 2001), even when controlling for ‘catastrophising’. Catastrophising is discussed below.

Expectations can also refer to ‘efficacy expectancies’ (e.g. self-efficacy) or a person's confidence that they have the ability to cope with pain or an activity. Self-efficacy has been shown to predict pain behaviour and avoidance (Asghari & Nicholas 2001), even when controlling for ‘catastrophising’. Catastrophising is discussed below.

Appraisals – what the person assumes the pain means; at the extreme level this can lead to ‘catastrophising’ about the pain which, in turn, can lead to high levels of distress and disability. A number of studies have shown that the meaning ascribed to the pain, particularly as it relates to tissue damage, can influence the experienced intensity (e.g. Arntz & Claassens 2004). Other studies have shown that pain patients with a high level of pain-related fear can have a bias to interpret innocuous or pain-related stimuli in a threatening way (e.g. Vancleef et al 2009).

Appraisals – what the person assumes the pain means; at the extreme level this can lead to ‘catastrophising’ about the pain which, in turn, can lead to high levels of distress and disability. A number of studies have shown that the meaning ascribed to the pain, particularly as it relates to tissue damage, can influence the experienced intensity (e.g. Arntz & Claassens 2004). Other studies have shown that pain patients with a high level of pain-related fear can have a bias to interpret innocuous or pain-related stimuli in a threatening way (e.g. Vancleef et al 2009).

Catastrophising

Catastrophising has been identified as a robust psychological predictor of pain-related outcomes. It refers to the tendency to exaggerate the negative consequences of actual or anticipated pain to an extreme level and comprises elements of rumination about the pain, magnification of its effects and helplessness (Sullivan & Martel 2012). A large number of studies have attested to the link between catastrophising about pain and increases in disability, distress and pain intensity. For example, Hanley et al (2008) found that changes in catastrophising and belief in one's ability to control pain were each significantly associated with greater pain interference and poorer psychological functioning, while changes in social support and specific coping strategies were not.

Fear avoidance

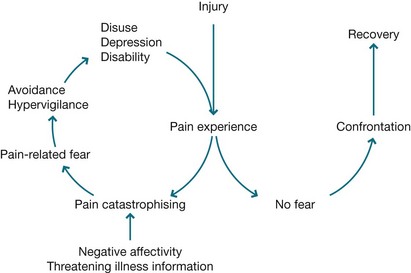

People in pain can evidence a high level of ‘fear avoidance’, such that they become fearful of engaging in physical activity due to the risk of increased pain and/or (re)injury and therefore avoid the activity (see Fig 12.3) (Vlaeyen et al 1995, Vlaeyen & Linton 2000). Over time this can result in significantly reduced activity levels, increased disability, deconditioning and depression or distress. Fear avoidance provides an excellent example of the interaction of three separate levels of the biopsychosocial model. Beliefs or appraisals of pain at one level result in anxiety or fear at the next level that, in turn, results in disability or pain behaviours at the next. The latter then further entrench the negative aspects of the pain experience and therefore fear avoidance becomes established. Leeuw et al (2007) recently published a comprehensive review of the current evidence for the fear-avoidance model and concluded that there is accumulating support for its various components.

Figure 12.3 The fear-avoidance model Figure 2 from Vlaeven Johan WS and Linton Steven J. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. PAIN® 2000 April 85(3); 317–332. This figure has been reproduced with permission of the International Association for the Study of Pain® (IASP). The figure may NOT be reproduced for any other purpose without permission.

Psychological distress (suffering)

For many people pain, by definition, entails suffering. Nevertheless the degree of suffering is clearly variable and likely to be influenced by a range of factors. For example, the duration, severity, frequency and number of sites of pain (Fishbain et al 1997) may impact on the level of suffering. The contributors to distress and suffering for a person with pain can be widespread and significant (Turk et al 2010, Williams 1998). They may experience a wide range of losses both material and intangible, covering everything from employment and finances, to changes in relationships, being able to maintain independence, issues of self-worth and so on. They also often experience symptoms such as fatigue, difficulty concentrating, muscle tension, disturbed sleep, side effects of medication and deconditioning. In addition they may have to deal with a range of health professionals, with possible disbelief and lack of understanding from some and undergo a variety of tests and interventions. They may have numerous fears or worries, including fear about the cause of the pain or that the doctors have missed something, fear of re-injury, worries about the future, financial concerns and so on.

An important point to note here, in terms of the biopsychosocial model, is the way in which each of these factors has the potential to impact on every other factor. For example, a person may avoid certain activities as a result of pain, experience weight gain, deconditioning and loss of social contact as a result, followed by a drop in mood. Then, due to low mood, they have great difficulty in being motivated to become active again and therefore the low mood and deconditioning become further entrenched.

There is often considerable overlap between the symptoms of mood disturbance and those caused by the pain or factors related to it such as inactivity and the side effects of medications. For example, disrupted sleep, low energy, poor concentration, sexual dysfunction and weight changes can be the result of any of these.

Given all the issues faced by people with persistent pain it is not surprising that a large proportion may be diagnosed as having depression or an anxiety disorder (Turk et al 2010). Although issues of measurement and definition make establishing prevalence difficult (Williams 1998), few would dispute that it is a major issue for a large number of such people. Studies in the area of depression suggest a wide range of prevalence ranging from 10% to as high as 100% but with the majority reporting it in over 50% of cases (Sullivan 2001).

There has been much debate about the relationship between depression and chronic pain, particularly regarding the question of whether pain causes depression or depression leads to pain (Turk et al 2010). A comprehensive review of the literature on the pain–depression association by Fishbain et al (1997) found little evidence for the hypothesis that depression leads to pain, while all studies relating to the hypothesis that pain can lead to depression had results consistent with that hypothesis. In addition, increased pain led to increased depression rather than the other way around. Having said that, it would of course always be important to establish if there is any history of depression or other psychiatric illness.

In addition to anxiety and depression, anger is a very common feature of a persistent pain presentation (Turk et al 2010). There are many possible sources of anger including inability of the medical profession to help, repeated treatment failures, frustration at not being able to do things, anger with people who do not appear to understand or believe the pain is real, difficulties in dealing with insurers or employers, and so on.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and chronic pain can share a specific relationship in that very often the accident or trauma that occasioned the ongoing pain has also caused post-traumatic stress symptoms (see Sharp & Harvey 2001). For example, as a result of a motor vehicle accident, a person may experience pain from physical injuries and post-traumatic stress symptoms relating to the accident. A study by Tsui et al (2010) suggested that hyperarousal (a symptom of PTSD) can be a significant predictor of pain-related disability and decreased acceptance. Not surprisingly, as with depression, having PTSD and chronic pain means an additional load and likely interactions for the patient. This means both must be addressed.

Pain behaviour (Disability)

As pointed out by Fordyce (1976), the only way in which we can know that a person is in pain is by their display of pain behaviour, by observing what they do or do not do and what they tell us. There is no objective measure of pain available to us other than this. Moreover, as pointed out earlier in the chapter, there is often no correlation between what we observe in this regard and identifiable tissue damage. Pain behaviours can take many forms from grunting, moaning and groaning, to limping, distorted posture and being hunched over. People may tell you that they are in pain but equally their lack of social engagement may be an indicator of discomfort. They may take medication, attend numerous medical appointments or treatments and they may take time off work, lie down or cease activities. Equally they may rate their pain as being very high on questionnaires or in response to questions about their pain. It is important to note in relation to pain behaviours that, because pain is a completely subjective experience and because there are no objective measures, health professionals can only go by the person's report. A change in such behaviours and reports can at least indicate that, for that person, at that time, there has been a change in their experience of the pain. Note also, suggesting to a person that they are not in pain may only serve to increase the display of pain behaviour. The important point here is that if pain is viewed as an experience, the distinction between real, exaggerated or fabricated pain becomes irrelevant. For health professionals the targets of treatment become not the pain itself but the associated suffering or disability (Fordyce 1988).

Environment

The environment or context in which pain occurs can have a significant impact on a person's experience of that pain. Environment or context can refer to a range of factors including: the situation in which the pain occurred, for example, while playing sport, during an argument or slipping on a step; the response of others such as family or health professionals to the pain; and legal or compensation matters.

The role of learning

Fordyce (1976) proposed that operant learning plays an important role in the development and maintenance of pain behaviour. Operant conditioning (see Chs 1 and 7) refers to the reinforcement or rewarding of a behaviour, such that it is more likely to occur in the future. In the case of pain, for example, reinforcement of behaviours, like groaning and grimacing by encouraging the person to rest and take medication, is likely to lead to increased groaning and grimacing in the future, especially if it allows the person to avoid aversive tasks. On the other hand, reinforcing activity and normal function, while at the same time extinguishing pain behaviours through lack of reinforcement, can be an effective intervention for pain (Eccleston et al 2009, Guzman et al 2001). Research in the area has shown that reinforcement contingencies cannot only modify pain behaviours but also influence the development and maintenance of these behaviours (Jolliffe & Nicholas 2004, see Research focus).

Classical conditioning (see Chs 1 and 7) can also play a role in maintaining pain behaviour. Linton et al (1985) proposed that pain can act as an unconditioned stimulus (UCS), eliciting physiological responses that may become conditioned to other stimuli (CS) present at the same time as the painful stimulation. For example, stimuli associated with painful experiences such as needles when having an injection or the sound of a drill when at the dentist can become conditioned (through pairings with pain) to elicit fear and physiological changes, such as muscle tension, even in the absence of pain. Recent literature has pointed out that interoceptive stimuli (internal bodily sensations) can also become predictors of pain (De Peuter et al 2011) through a process of classical conditioning. For example, stiff joints or muscle twitches can elicit a defensive or conditioned response and pain patients may try to avoid such sensations by minimising activity. This in turn can lead, through a process of operant conditioning, to a vicious circle whereby the reduced activity is reinforced by a reduction in fear or the non-occurrence of pain.

Partner or significant other

An important source of reinforcement contingencies is a person's partner and/or family. A number of studies have shown that these can play an important role in developing or maintaining pain behaviour (Cano & Leong 2012). While social support may be an important factor in helping a person to cope with pain, such support can become ‘solicitous’ and there is clear evidence that solicitous partners can maintain and even increase disability and pain behaviour. ‘Solicitous’ in this context refers to behaviours by others such as sympathy, taking over tasks, and assistance, which serve to reinforce or reward pain behaviours. Note that the dynamics can be complex, with a number of other factors influencing outcome such as the person's level of depression, their satisfaction with the marriage or relationship, and the context in which the interaction takes place, for example, in front of mates as opposed to in the hospital (Newton-John 2002). Contrary to what might be expected, punishing responses to pain behaviour from a partner can also serve to increase that behaviour, possibly by contributing to levels of depression (Cano & Leong 2012). Importantly it is the perception on the part of the pain patient of the partner's response that matters.

Gender and cultural factors

Gender appears to have an influence on pain, with a number of studies clearly demonstrating that women report more pain, both acute and chronic, than men (Fillingim 2010). The reasons for this are not clear but studies have suggested that gender differences in nociceptive processing and hormonal influences may play a role. Stereotypic gender roles appear to account for some differences, especially in the reporting of pain in experimental pain responses (Fillingim 2010), with both men and women reporting that women are more comfortable than men to report pain.

In the case of cultural factors, the research is again not conclusive, partly because culture is itself not a clear construct and can be influenced by a number of factors, including ethnicity, gender, education and religion. The information available suggests that cultural factors, particularly those influenced by ethnic background, can be important in the expression and conceptualisation of pain. For example, studies have shown that certain ethnic groups may report higher levels of pain, be more disabled and display a higher level of pain behaviour (Otis et al 2004). Although ethnicity may affect pain, this appears to be primarily through sociocultural influences rather than through genetics (Morris 2010). People's attitudes and responses to pain are shaped by social norms within particular social contexts and can change over generations. This is most clearly illustrated by differences in response to health issues between immigrants and their acculturated offspring (Morris 2010). Moreover, it is likely that there are as many differences between people of a certain cultural background as there are similarities. Therefore, in the clinical context, although it is important to be culturally sensitive to a person's background, it is equally important to avoid stereotyping (Ng et al 1996).

A number of studies in the United States have shown that health professionals are not immune to practising discrimination, whether they are aware of it or not (Morris 2010). For example, studies by Todd et al (1993) and Todd (1996) have shown that people from a Hispanic background presenting at an emergency department with fractures were twice as likely as similar Caucasian patients to go without pain medication. Other studies have shown that African-American patients with sickle cell disease seeking pain relief have been suspected of drug seeking (Wailoo 2001). Studies of pain treatment in cancer patients have also suggested that people from minority groups experience inadequate pain relief (Cleeland et al 1997). The reasons for this may be complex including language difficulties and/or socioeconomic status, but such findings also suggest the possibility of stereotyping.

The healthcare system and healthcare providers

The information and treatments provided to a person in pain can have a strong impact on both their expectations and understanding of the pain and consequent self-management. Information given to the patient such as advising a person to let pain be their guide can contribute to a sense of helplessness and increased disability (Kouyanou et al 1997). Facial expressions and the language health professionals use can inadvertently encourage catastrophising in patients (Vlaeyen & Linton 2006); for example, the term ‘degeneration’ of the spine can lead a patient to think that their spine is crumbling away and they must be very careful. This is despite the fact that an x-ray of anyone's spine over the age of 30 will show some signs of degeneration.

In the case of chronic pain, ongoing recommendations for biomedical investigations, interventions and passive treatments implies to the patient that there is indeed something wrong and that it needs to be fixed before they can resume normal life activities. This is despite the fact that, at present, there is little evidence that commonly practised medical treatments for chronic pain make any difference in terms of increasing function and returning people to work (Hansson & Hansson 2000).

A number of studies have suggested a clear link between higher fear-avoidance beliefs in healthcare practitioners and increased recommendations for rest, and less advice to maintain physical activities and higher fear-avoidance beliefs in patients (Coudeyre et al 2006, Linton et al 2002, Poiraudeau et al 2006). This may represent confusion between acute and chronic pain states, but even in acute and subacute back pain, the available evidence and a range of guidelines clearly recommend reassurance by the clinician and encouragement for resumption of activity (e.g. Van Tulder et al 2005).

The workplace and the compensation system

A number of factors relating to the workplace have been identified as impacting on outcome in terms of return to work (Shaw et al 2012). Work-related risk factors include physical work demands such as lack of modified duties and heavy or fast work; social factors such as lack of support or having little control; perceptions about work especially job dissatisfaction; and workplace disability management (Shaw et al 2012).

People with compensation claims are often regarded as having a motive for exaggerating their pain or disability, but in fact research in the area suggests that there are no important differences between compensated and non-compensated patients and the vast majority of workers do recover and get back to work (Robinson & Loeser 2012). However, a systematic review by Harris et al (2005) of a large number of postoperative cases in many countries did find that having a compensation claim was strongly associated with poorer health outcomes. Likewise an Australian study looking at people injured in motor vehicle accidents found that a compensation claim was associated with poorer health outcomes (Gabbe et al 2007).

The reasons for these poorer outcomes are unclear, but proposed contributing factors include the possibility of secondary gains such as financial compensation, avoidance of unpleasant tasks and attention from others. Note claimants may not be consciously aware of the pursuit of these gains and most also experience a wide range of secondary losses (Robinson & Loeser 2012). Other proposed contributing factors include a difficult claims and settlement process, inability to move on with life during this process, extreme dislike of medicolegal assessments, necessity of legal representation and a perceived lack of trust about having to prove an injury or disability (Murgatroyd et al 2011). Of notable importance is that people in the compensation system are required, by the system itself, to constantly report and demonstrate their symptoms in order to be compensated, which, in turn, encourages focusing on disability rather than rehabilitation (Nicholas 2002).

Acute versus chronic pain

Acute pain is short-lived; it can last from a few seconds to a few hours but generally less than three months and is associated with injury, disease or inflammation of somatic, visceral or nervous system structures. Acute pain is generally thought to have a protective biological function, for example, when a person touches a hot stove, pain alerts them to immediately withdraw their hand. Likewise, following a fracture, pain imposes significant limitation of function that is useful in preventing further damage (Hurley et al 2010). However, in some instances, the warning (pain) comes too late to avoid injury. Sunburn is such an example.

As noted above, the distinction between acute and chronic pain has traditionally relied on a measure of time; however, using time to distinguish between acute and chronic pain is subjective and can be ambiguous (Turk & Okifuji 2010). For example, pain that persists for extended periods of time in the presence of ongoing pathology might be viewed by some as acute, whereas others would classify it as chronic (Turk & Okifuji 2010). Moreover, pain can be considered chronic if it extends beyond tissue healing, even when this is only a relatively short period of time. This ambiguity has led Turk and Okifuji (2010) to propose a two-dimensional conceptualisation of acute and chronic pain, one that is based on time and physical pathology. From this two-dimensional perspective, pain of short duration or associated with high physical pathology is acute, whereas pain associated with low physical pathology or of long duration is chronic (Turk & Okifuji 2010).

The nervous system changes that occur in response to injury or disease were discussed earlier in this chapter. Acute pain may be associated with anxiety and fear, particularly if it is unexpected and severe and can have deleterious effects if left unchecked (Hurley et al 2010). The emphasis in managing acute pain therefore, should be to identify the cause and provide pain relief until healing occurs. Adequate analgesia is necessary, particularly in the case of severe trauma and postoperative pain, to reduce the risk of acute pain persisting (Hurley et al 2010). Under normal conditions, following recovery, the pain and associated nervous system responses usually disappear within days or weeks.

Chronic pain, on the other hand, results in numerous pathophysiological peripheral and central nervous system changes and is only rarely amenable to effective biomedical treatment (Turk & Okifuji 2010). It may represent a low level of underlying pathology (e.g. as in osteoarthritis), but usually such pathology fails to explain the presence and/or extent of pain. While chronic pain may have been initiated by an injury or disease, the factors that maintain it are more than likely both physically and pathogenetically removed from the originating cause (Turk & Okifuji 2010).

Persistent pain can have a strong impact on psychological function and can have significant functional consequences. People report mood and sleep disturbance, irritability, distress, helplessness and depression. They may lose confidence in their ability to perform tasks and become fear avoidant. There may be other consequences such as loss of status, relationship breakdown and loss of employment. Therefore, in order to successfully manage chronic pain, it is necessary to assess the relative contribution of physical, psychological and environmental factors, and to address the consequences of pain.

In some cases, it may be possible to address the initial pathology resulting in significant reduction or resolution of pain and its associated consequences. For example, pain and secondary changes such as central sensitisation, mood disturbance and disability will generally disappear following a procedure (e.g. hip replacement surgery) that successfully resolves the initial pathology, regardless of chronicity (e.g. Rodriguez-Raecke et al 2009). However, in other cases, it may be impossible to identify or adequately treat the initial pathology. In these cases, the focus should be on dealing with the initial pathology if possible, but of equal importance is to identify and address the functional consequences of pain, such as depression, sleep disturbance, loss of meaning in personal relationships and work, fear avoidance of activities and postural changes. Persisting with the search for a cause or a cure of their chronic pain can prevent a person from accepting and dealing with their pain and can prolong or exacerbate their suffering and disability (McCarberg 2010).

Transition from acute to chronic pain and disability

Many people with chronic pain continue to lead active lives despite ongoing pain. An epidemiological study by Blyth et al (2001) established that in Australia just over 17% of male adults and 20% of adult females report having chronic pain. Nearly half of those reported that it was having little impact on their lives, while the other half reported varying levels of interference, some to a significant degree. A more recent population study conducted in South Australia confirmed the overall prevalence of chronic pain and noted that the degree to which pain interfered ‘extremely’ with activity was 5% (Currow et al 2010).

For those who do experience this level of interference, one might assume that this is because of the severity of the injury and pain. In fact, research in this area has made it increasingly clear that many factors unrelated to the physical injury can have a significant impact on a person's recovery and return to normal function (Nicholas et al 2011). Importantly, after three to six months, the likelihood of a person recovering and returning to normal activities becomes increasingly less likely, despite ongoing consumption of healthcare resources (Cohen et al 2000).

This means, of course, that it would be very useful to be able to predict who might be at risk of developing chronic pain and a high level of disability, and provide appropriate interventions at an early stage. There has been extensive research into which factors might be relevant in the development of chronic pain and a range of psychological, social and environmental risk factors have been identified. Table 12.2 outlines some of these factors, differentiating psychological factors from work and biomedical factors according to a system of coloured flags. Some of these factors were discussed earlier in the section on the workplace and the compensation system. A number of screening tools have been developed to help health professionals identify people at risk for persisting pain and disability (Nicholas et al 2011).

Table 12.2

RISK FACTORS FOR TRANSITION OF PAIN FROM ACUTE TO CHRONIC, ACCORDING TO THE COLOURED FLAG SYSTEM

| Flag | Type | Examples |

| Red | Signs of serious pathology | Tumour; infection; cauda equina syndrome; fracture; neurological signs |

| Orange | Psychiatric issues | Major depression; schizophrenia |

| Yellow | Psychological factors | High levels of distress or anxiety; beliefs about pain (e.g. increased pain means further damage); expectation of need for resolution of pain; over-reliance on passive treatments; avoidance of activity due to fear of pain and/or damage |

| Blue | Perceptions about workplace and health | Job dissatisfaction; belief that there is a lack of support at work; belief that the job is too demanding physically and/or mentally; attribution of pain condition to work |

| Black | System factors – occupational and legal | Availability of modified duties; lack of support from the workplace; limitations imposed by legislation or the return to work system; conflict with the insurer or workplace |

Source: Nicholas MK, Linton SJ, Watson PJ, Main CJ, the ‘Decade of the Flags’ Working Group. Early identification and management of psychological risk factors (‘yellow flags’) in patients with low back pain: a reappraisal. Phys Ther. 2011;91:737–753. © 2011 American Physical Therapy Association

Interventions and management for pain

Biomedical interventions

A discussion of the interventions used to manage pain should be prefaced by a discussion of the nonspecific effects of treatment. One could argue that a positive response following treatment may come about in three ways: the specific effects of the treatment; natural history or regression to the mean; and nonspecific effects, such as attention from healthcare providers, a desire to improve, a reduction in anxiety and improved coping (Jamison 2011). In other words, the overall response to an active treatment can be viewed as the sum of the treatment itself and the context in which treatment is given (Finniss et al 2010). There is growing evidence from the placebo literature that these nonspecific or placebo effects are genuine psychobiological phenomena attributable to the therapeutic context, including individual patient and clinician factors, and the interaction between the clinician, the patient and the therapeutic environment (Finniss et al 2010). For example, in a series of large trials comparing traditional acupuncture, sham acupuncture and either no treatment or usual clinical care, patients' expectation of pain relief was the most powerful predictor of treatment benefit, regardless of group allocation to traditional or sham acupuncture (Linde et al 2007).

The emphasis in managing acute pain is to identify and treat the cause or to provide pain relief until healing occurs. Acute musculoskeletal pain can respond well to a short course of a variety of medications. Simple analgesics such as paracetamol and NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) are mostly used for mild pain, compound analgesics (e.g. paracetamol plus codeine) and weak opioids (e.g. tramadol) are used for moderate pain and strong opioids (e.g. morphine, oxycodone) are used for severe pain. The choice of medication should be individualised and should include a discussion with the patient of the potential benefits and risks of therapy (Chou 2010).

In the past 20 years there has been a swing to increased use of strong opioids for treating chronic pain. However, the use of these drugs has been linked with nausea, constipation, drowsiness, mood change, poor concentration, drug tolerance and dependence. Long-acting formulations and transdermal patches are able to provide more stable levels of analgesia but a large number of people on strong opioid medication still report ongoing pain and minimal functional gain (Nicholas et al 2006).

Neuropathic pain, on the other hand, generally does not respond well to NSAIDs, and opioids should only be considered as second- or third-line options in noncancer neuropathic pain treatment due to the risks associated with long-term use such as opioid-induced hyperalgesia (Attal & Finnerup 2010). However, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), in lower doses than would normally be used for treating depression, can be effective in treating neuropathic pain and may also help with sleeplessness and comorbid depression. Side effects include weight gain, constipation, blurred vision, drowsiness, poor concentration and clouded thinking. Anticonvulsants generally reduce the abnormal firing of sensory nerves that occurs with neuropathic pain. The newer anticonvulsants, such as gabapentin and pregabalin, have fewer side effects but are nevertheless associated with a number of adverse reactions and are more expensive. Side effects include impaired memory and reduced concentration. Additionally, the newer serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) antidepressants (e.g. duloxetine and venlafaxine) have established efficacy in the treatment of neuropathic pain and are recommended as first-line treatments, along with TCAs, gabapentin and pregabalin (Attal & Finnerup 2010).

Surgery

Surgery has a major role to play in managing some pain conditions, such as where a lesion or abnormality is able to be identified and resected, repaired, reconstructed, reinforced or replaced, but outcomes are not as good if the main reason for surgery is pain relief (Ghabrial & Bogduk 2010). For example, outcome studies have concluded that although surgery can be indicated for patients with specific spinal conditions, such as cauda equina syndrome, there is little advantage of surgery over conservative treatment at 12–24 months for patients with low back pain and sciatica (Koes et al 2007). There is also the possibility that surgery may make the pain worse.

A number of techniques are available to cut nerves in an attempt to eliminate pain. These procedures are mostly used for severe cancer pain in terminally ill patients and are not recommended for treating chronic pain. An exception is radiofrequency (RF) lesioning of the small nerves that supply the facet joints in the spine. This procedure can relieve pain by stopping nociceptive inputs from reaching the spinal cord and brain (Dreyfuss et al 2000). However, it is only suitable for a very small group of people with a specific form of spinal pain and the pain can return when the nerves re-grow.

Injections

Different types of injections can be used to treat pain; these include local anaesthetic blocks and steroid injections. Local anaesthetic blocks may be useful as a diagnostic procedure and can assist in temporarily reducing chronic pain. Steroid injections can be helpful in reducing inflammation in some acute conditions but they cannot be repeated very often and are associated with a number of side effects.

Stimulation techniques

A variety of stimulation techniques have also been used for treating pain with varying levels of success. These include acupuncture, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), spinal cord stimulation and deep brain stimulation. Acupuncture has been demonstrated to be useful for some types of acute and chronic pain but the effects are short lived and, in the case of chronic pain, treatment needs to be repeated at regular intervals. The other stimulation techniques mentioned above are thought to act on inhibitory mechanisms at the level of the spinal cord and brain and can be particularly useful for treating certain types of neuropathic pain.

Physical therapies and exercise

A number of physical and manual therapies are used in the treatment of both acute and chronic musculoskeletal pain, although there is continuing debate about the effectiveness of such treatments in the long term. Passive modalities include massage, manipulation, ultrasound, hot packs and cold packs. These can be helpful in relieving acute musculoskeletal pain but, as the effects are short lived, they are less useful in managing chronic pain and in returning people to normal activities. A greater understanding of the biopsychosocial model of pain calls for a novel approach to physical therapy, termed ‘psychologically informed practice’, whereby treatment of patients anywhere along the pain continuum incorporates systematic attention to the psychosocial factors that are associated with poorer treatment outcomes (Main & George 2011).

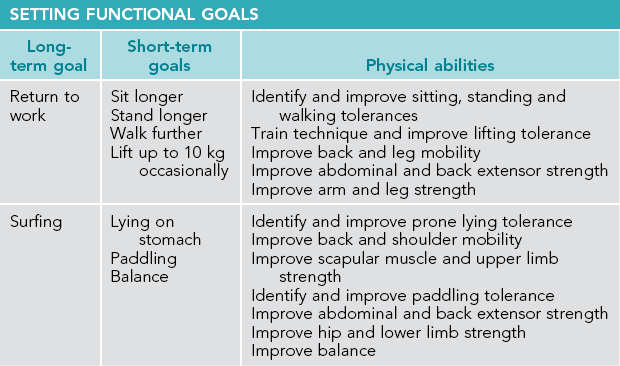

Research into the treatment of patients with subacute low back pain has demonstrated that physiotherapist-directed exercise and advice have beneficial effects on pain and function at six weeks, when compared with placebo (Pengel et al 2007). In the case of ongoing pain, the focus of treatment shifts from pain relief to a gradual resumption of normal activities despite the presence of pain. Exercise can be beneficial in reversing some of the secondary changes that occur such as decreased mobility and strength and reduced fitness. Exercise programs typically include stretching, strengthening, aerobic and functional components and should focus on encouraging a return to normal function. Exercise should be progressed gradually to minimise over-stimulation of a sensitised nervous system and should be based on the individual's functional goals. A recent systematic review of physical conditioning programs with a stated relationship to the workplace and a focus on job demands by Schaafsma and colleagues (2010) concluded that intensive physical conditioning programs improved long-term return to work outcomes for patients with chronic low back pain compared with routine clinical care. It is important to note that for patients with chronic pain, exercise is not an end in itself but a means of exposure to feared or avoided activities and forms a series of stepping stones towards achieving functional goals.

Psychological approaches

A range of psychological strategies can be used to help people manage both acute and chronic pain. In the case of acute pain, information and education about what is going to happen in a proposed treatment and what to expect in terms of pain can be helpful in terms of allaying fears and reducing distress, for example, prior to a surgical procedure. Training a patient in ways to calm themselves, such as by relaxation, forms of meditation and self-hypnosis, can also be beneficial. Attentional techniques such as distraction can be useful. However, studies on the effectiveness of all these techniques suggest they have variable rates of success (Macintyre et al 2010). Repeated practise by the patient appears to be important as does structure, specific (written) instructions, and an understanding that the primary goal is to reduce distress rather than pain. In the case of education and information it is important to check what the beliefs and concerns of the patient actually are. Simply providing education and information will not necessarily remove fear.

In the case of chronic pain the above techniques can also be of benefit but the emphasis shifts to long-term management of the pain, rather than simply dealing with the current episode of pain. In practice this means learning to live with the pain and returning to normal activities and function despite pain. The patient can sometimes interpret this as ‘a last resort’ or as an indication that they are being told their pain is ‘all in their head’. Therefore it is essential to clarify the rationale and benefits of psychological management strategies when introducing them. Education regarding the physiological mechanisms causing persisting pain can play an important role in reassuring patients that persisting pain is not necessarily a sign of further damage and that it is safe to upgrade activity levels. Psychological strategies can be introduced at the same time as biomedical interventions, or in a planned sequence. In the case of chronic pain it can sometimes be useful to introduce them when biomedical interventions have been completed because of the different goal: improved self-management and adjustment to the pain as opposed to pain reduction.

Cognitive-behavioural approaches

There is good evidence that cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to help people manage pain, particularly chronic pain, is effective for the targeted outcomes (e.g. increased function, improved mood, reduced use of medications and return to work) (Eccleston et al 2009, Guzman et al 2001, Nicholas et al 2012). It can be delivered in individual sessions with different health professionals, for example, a physiotherapist and a psychologist, but the evidence available suggests that it is more effective when delivered as part of a structured intensive program, particularly for those who are more disabled and distressed (Haldorsen et al 2002). It is of course important that all health professionals working with a patient deliver a consistent message and work within the same biopsychosocial framework.

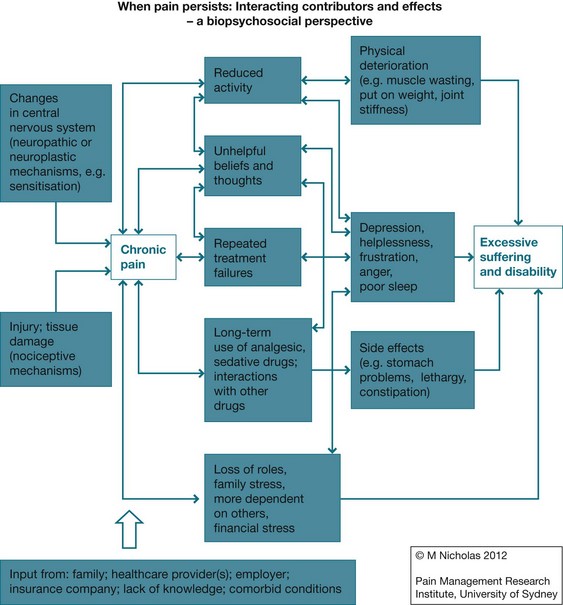

For patients who have had chronic pain for some time and who have not managed to return to normal function, the impact on many areas of their lives can be significant and seem insurmountable. They often report feeling that they have tried everything and there is now little hope for improvement. The diagram in Figure 12.4, based on the biopsychosocial model of pain, outlines the typical experience for a chronic pain patient.

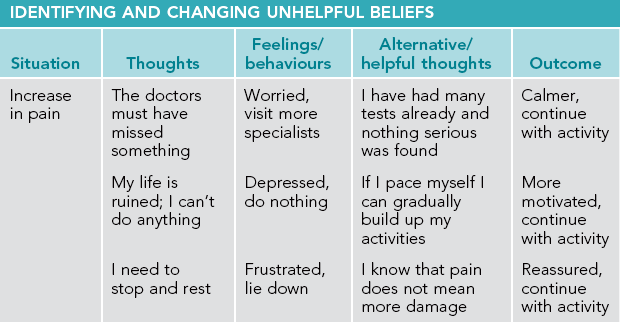

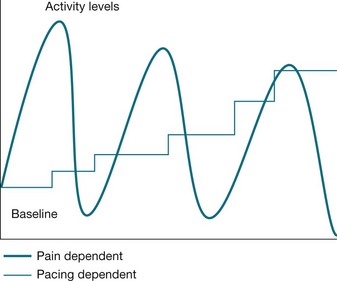

In cases such as these, a comprehensive and intensive cognitive-behavioural program can be used to target and improve all aspects of the presentation. Such a program is usually delivered by a physiotherapist and psychologist, specially trained in the area of chronic pain management, who work together as an integrated team. Other health professionals involved may include a doctor (to rationalise and/or reduce medication), a nurse and a work rehabilitation adviser. The typical components of such a program include education about pain, setting functional goals, upgrading activity levels in a paced manner so as to progress towards those goals, programmed exercises and stretches, applied relaxation training, desensitisation to the pain, identifying and changing unhelpful beliefs and thought patterns, learning effective problem-solving techniques, reduction of medication use and other passive strategies such as resting or avoidance of activities and, where relevant, formulating a plan to return to work. Some of these components are illustrated in Tables 12.3 and 12.4 and Figure 12.5. Note that pain reduction itself is not specifically targeted as this can lead to constant monitoring of the pain along with unhelpful attempts to avoid and reduce it. However, there is increasing evidence that once people are managing their pain better and are more engaged in life, they often report reduced pain (e.g. Nicholas et al 2012).

Conclusion

This chapter gives an overview of the current understanding of the experience of pain. It explains the neurobiological basis of pain, including the difference between nociceptive and neuropathic pain, the role of central sensitisation and the distinction between acute and chronic pain. It further explains that despite this neurobiological basis, the presentation of pain can only be usefully explained and understood when all relevant psychological and environmental factors are taken into account. This is particularly important in the case of chronic pain where biomedical interventions have only limited effectiveness and the emphasis shifts from pain relief to pain management and specifically to more adaptive management of relevant psychosocial factors.

Fishman S.M., Ballantyne J.C., Rathmell J.P., eds. Bonica's management of pain, fourth ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.

Hasenbring M.I., Rusu A.C., Turk D.C., eds. From acute to chronic back pain: risk factors, mechanisms, and clinical implications. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) Task Force on Taxonomy. Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms, second ed. Washington DC: IASP; 1994.

Melzack, R., Wall, P.D. The challenge of pain. New York: Basic Books; 1982.

Turk, D.C., Monarch, E.S. Biopsychosocial perspective on chronic pain. In: Turk D.C., Gatchel R.J., eds. Psychological approaches to pain management. A practitioner's handbook. second ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002:3–29.

Vlaeyen, J.W.S., Linton, S.J. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain. 2000; 85(3):317–332.

International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP)

The IASP was founded in 1973 and is the world's largest multidisciplinary organisation focused specifically on pain research and treatment. It brings together scientists, health professionals, healthcare providers and policymakers to stimulate and support the study of pain. The website gives details of all its activities, publications, events and meetings and also provides links to many other useful websites.

PAIN – the official journal of IASP

PAIN is the official journal of the International Association for the Study of Pain. The IASP publishes 18 issues per year of original research on the nature, mechanisms and treatment of pain. This peer-reviewed journal provides a forum for the dissemination of research in the basic and clinical sciences of multidisciplinary care.

Pain Management Research Institute, Royal North Shore Hospital

The Pain Management Research Institute (PMRI) is a joint initiative between the University of Sydney and Royal North Shore Hospital. It conducts basic and clinical research programs and also operates a national and international educational program leading to a master's qualification in pain management. The PMRI works in close collaboration with the Pain Management and Research Centre (PMRC), which treats patients with acute pain, cancer pain and chronic non-cancer pain. The website gives details of all these activities and provides links to a wide range of other useful websites.

APSOC was formed in 1979 as the Australian chapter of the International Association for the Study of Pain.

References

Apkarian, A.V., Hashmi, J.A., Baliki, M.N. Pain and the brain: specificity and plasticity of the brain in clinical chronic pain. Pain. 2011; 3(Suppl):S49–S64. [152].

Arntz, A., Claassens, L. The meaning of pain influences its experienced intensity. Pain. 2004; 109:20–25.

Asghari, A., Nicholas, M.K. Pain self-efficacy beliefs and pain behavior: a prospective study. Pain. 2001; 94:85–100.

Attal, N., Finnerup, N.B. Pharmacological management of neuropathic pain. IASP Pain Clinical Updates. 2010; 18(9):1–8.

Blyth, F.M., March, L.M., Brnabic, A.J.M., et al. Chronic pain in Australia: a prevalence study. Pain. 2001; 89:127–134.

Buchbinder, R., Jolley, D., Wyatt, M. Effects of a media campaign on back pain beliefs and its potential influence on management of low back pain in general practice. Spine. 2001; 26(23):2535–2542.

Cano, A., Leong, L. Significant others in the chronicity of pain and disability. In: Hasenbring M.I., Rusu A.C., Turk D.C., eds. From acute to chronic back pain: risk factors, mechanisms, and clinical implications. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Chapman, C.R., Okifuji, A., Pain mechanisms and conscious experience. Psychosocial aspects of pain: a handbook for health care providers. Progress in Pain Research and Management. Dworkin, R.H., Breitbart, W.S., eds. Psychosocial aspects of pain: a handbook for health care providers. Progress in Pain Research and Management; Vol. 27. IASP Press, Seattle, 2004.

Chou, R. Pharmacological management of low back pain. Drugs. 2010; 70(4):387–402.

Cleeland, C., Gonin, R., Baez, L., et al. Pain and treatment of pain in minority patients with cancer: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Minority Outpatient Pain Study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997; 127:813–816.

Cohen, M., Nicholas, M., Blanch, A. Medical assessment and management of work-related low back pain or neck/arm pain. Journal of Occupational Health and Safety – Australia NZ. 2000; 16:307–317.

Cope, D.K. Intellectual milestones in our understanding and treatment of pain. In Fishman S.M., Ballantyne J.C., Rathmell J.P., eds.: Bonica's management of pain (online), fourth ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.

Coudeyre, E., Rannou, F., Tuback, F., et al. General practitioners’ fear-avoidance beliefs influence their management of patients with low back pain. Pain. 2006; 124:330–337.

Currow, D.C., Agar, M., Plummer, J.L., et al. Chronic pain in South Australia – population levels that interfere extremely with activities of daily living. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2010; 34(3):232–239.

De Peuter, S., Van Diest, I., Vansteenwegen, D., et al. Understanding fear of pain in chronic pain: interoceptive fear conditioning as a novel approach. European Journal of Pain. 2011; 15:889–894.

Dreyfuss, P., Halbrook, B., Pauza, K., et al. Efficacy and validity of radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic lumbar zygapophysial joint pain. Spine. 2000; 25(10):1270–1277.

Eccleston, C., Williams, A.C.D.C., Morley, S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009. [Issue 2. Art. No.: CD007407. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub2].

Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977; 196:129–136.

Fillingim, R.B. Individual differences in pain: the roles of gender, ethnicity, and genetics. In Fishman S.M., et al, eds.: Bonica's management of pain, fourth ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.

Finniss, D.G., Kaptchuk, T.J., Miller, F. Biological, clinical, and ethical advances of placebo effects. The Lancet. 2010; 375(9715):686–695.

Fishbain, D.A., Cutler, R., Rosomoff, H.L., et al. Chronic pain-associated depression: antecedent or consequence of chronic pain? A review. Clinical Journal of Pain. 1997; 13(2):116–137.

Fordyce, W.E. Behavioural methods for chronic pain and illness. St Louis: Mosby; 1976.

Fordyce, W.E. Pain and suffering: a reappraisal. American Psychologist. 1988; 43:276–283.

Freynhagen, R., Bennett, M.I. Diagnosis and management of neuropathic pain. British Medical Journal. 2009; 339:391–395.

Gabbe, B.J., Cameron, P.A., Williamson, O.D., et al. The relationship between compensable status and long-term patient outcomes following orthopaedic trauma. Medical Journal of Australia. 2007; 187:14–17.

Geber, C., Baumgärtner, U., Schwab, R., et al. Revised definition of neuropathic pain and its grading system: an open case series illustrating its use in clinical practice. The American Journal of Medicine. 2009; 122(10A):S3–S12.

Ghabrial, Y., Bogduk, N. Surgery for low back pain. In Fishman S.M., Ballantyne J.C., Rathmell J.P., eds.: Bonica's management of pain (online), fourth ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.

Guzman, J., Esmail, R., Karjaleinan, K., et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systematic review. British Medical Journal. 2001; 322:1511–1516.

Haanpää, M., Attal, N., Backonja, M., et al. NeuPSIG guidelines on neuropathic pain assessment. Pain. 2011; 152(1):14–27.

Haanpää, M., Treede, R.D. Diagnosis and classification of neuropathic pain. IASP Pain Clinical Updates. 2010; 18(7):18–27.

Haldorsen, E.M.H., Grasdal, A.L., Skouen, J.S., et al. Is there a right treatment for a particular patient group? Comparison of ordinary treatment, light multidisciplinary treatment, and extensive multidisciplinary treatment for long-term sick-listed employees with musculoskeletal pain. Pain. 2002; 95:49–63.

Hanley, M.A., Raichle, K., Jensen, M., et al. Pain catastrophising and beliefs predict changes in pain interference and psychological functioning in persons with spinal cord injury. The Journal of Pain. 2008; 9:863–871.

Hansson, T.H., HanSson, E.K. The effects of common medical interventions on pain, back function and work resumption in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine. 2000; 25:3055–3064.

Harris, I., Mulford, J., Solomon, M., et al. Association between compensation status and outcome after surgery. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005; 293(13):1644–1652.

Hurley, R.W., Cohen, S.P., Wu, C.L. Acute pain in adults. In Fishman S.M., Ballantyne J.C., Rathmell J.P., eds.: Bonica's management of pain (online), fourth ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.

International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) Task Force on Taxonomy. Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms, second ed. Washington DC: IASP; 1994.

Jamison, R.N. Nonspecific treatment effects in pain medicine. IASP Pain Clinical Updates. 19(2), 2011.

Jolliffe, C.D., Nicholas, M.K. Verbally reinforcing pain reports: an experimental test of the operant model of chronic pain. Pain. 2004; 107:167–175.

Koes, B.W., van Tulder, M.W., Peul, W.C. Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. British Medical Journal. 2007; 334(7607):1313–1317.

Kouyanou, K., Pither, C.E., Wesley, S. Iatrogenic factors and chronic pain. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1997; 59:597–604.

Leeuw, M., Goossens, M.E.J.B., Linton, S.J., et al. The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: current state of scientific evidence. Journal of Behavioural Medicine. 2007; 30(1):77–94.

Linde, K., Witt, C.M., Streng, A., et al. The impact of patient expectations on outcomes in four randomized controlled trials of acupuncture in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2007; 128(3):264–271.

Linton, S.J., Melin, L., Stjernlof, K. The effects of applied relaxation and operant activity training on chronic pain. Behavioural Psychotherapy. 1985; 13:87–100.

Linton, S.J., Vlaeyen, J., Ostelo, R. The back pain beliefs of healthcare providers: are we fear-avoidant? Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2002; 12(4):223–232.

Loeser, J.D. Concepts of pain. In: Stanton-Hicks M., Boas R., eds. Chronic low back pain. New York: Raven Press; 1982:145–148.

Macintyre, P.E., Schug, S.A., Scott, D.A., et al, Acute pain management: Scientific evidence APM:SE Working group of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine, third ed. ANZCA & FPM, Melbourne, 2010.

Main, C.J., George, S.Z. Psychologically informed practice for management of low back pain: future directions in practice and research. Physical Therapy. 2011; 91(5):820–824.

McCarberg, B. Pain management in primary care. In Fishman S.M., Ballantyne J.C., Rathmell J.P., eds.: Bonica's management of pain (online), fourth ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.

McCracken, L.M. ‘Attention’ to pain in persons with chronic pain: a behavioral approach. Behavior Therapy. 1997; 28:271–284.

Melzack, R., Wall, P.D. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965; 150(3699):971–978.

Melzack, R., Wall, P.D. The challenge of pain. New York: Basic Books; 1982.

Morris, D.B. Sociocultural dimensions of pain management. In Fishman S.M., et al, eds.: Bonica's management of pain, fourth ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.

Murgatroyd, D.F., Cameron, I.D., Harris, I.A. Understanding the effect of compensation on recovery from severe motor vehicle crash injuries: a qualitative study. Injury Prevention. 2011; 17:222–227.

Newton-John, T.R.O. Solicitousness and chronic pain: a critical review. Pain Reviews. 2002; 9:7–27.

Ng, B., Dimsdale, J.E., Rollnick, J.D. The effect of ethnicity on prescriptions for patient-controlled analgesia for post-operative pain. Pain. 1996; 66:9–12.

Nicholas, M.K., Reducing disability in injured workers: the importance of collaborative management. New avenues for the prevention of chronic musculoskeletal pain and disability. Pain Research and Clinical Management. Linton, S.J., eds. New avenues for the prevention of chronic musculoskeletal pain and disability. Pain Research and Clinical Management; Vol. 12. Elsevier Science BV, 2002:33–46.