Health promotion

The material in this chapter will help you to:

describe the contribution of the discipline of psychology to health promotion

describe the contribution of the discipline of psychology to health promotion

distinguish between health promotion and illness prevention

distinguish between health promotion and illness prevention

identify the social determinants of health

identify the social determinants of health

describe protective factors for health

describe protective factors for health

describe risk factors for illness

describe risk factors for illness

Introduction

Health promotion consists of a set of activities and programs that aim to facilitate wellness, prevent illness and foster recovery for individuals, communities and wider society. It is a relatively new endeavour in the health field and draws on ‘the knowledge and methods of diverse disciplines and being informed by new evidence about health needs and their underlying determinants’ (Smith et al 2006 p 340). Health promotion is not only informed by research evidence, it is also underpinned by ethical and social justice principles (Carter et al 2011). This chapter will examine the development of the health promotion movement from its emergence in the 1970s as a specific intervention to change individual health and lifestyle behaviours through to its evolution to a social determinants approach in the 21st century.

Initially, health promotion programs in the 1970s sought to improve health by encouraging individuals, through health education and counselling, to make behavioural and lifestyle changes. Through the 1980s health professionals became aware that broader social, political and economic forces also played a role in health outcomes, and health promotion activities expanded to reflect this. Consequently, contemporary health promotion has evolved to include population-focused models that utilise interdisciplinary, intersectoral and partnership approaches.

What is health promotion?

Health promotion consists of a range of strategies and activities that are designed to facilitate health and wellbeing and to prevent illness. Definitions of health promotion range from those that focus more on the individual and their personal responsibility for their health outcomes (O'Donnell 2008) to definitions that take account of the wider social, political and economic forces that influence the health of individuals, communities and wider society (World Health Organization (WHO) 1998). The editor of the American Journal of Health Promotion, for example, defines health promotion as:

… the science and art of helping people change their lifestyle to move towards a state of optimal health. Optimal health is the process of striving for a dynamic balance of physical, emotional, social, spiritual and intellectual health and discovering the synergies between core passions and each of those dimensions. Lifestyle change can be facilitated through a combination of efforts to enhance awareness, increase motivation, build skills and most importantly, to provide opportunities for positive health practices.

WHO, however, defines health promotion more broadly as:

A comprehensive social and political process [that] not only embraces actions directed at strengthening the skills and capabilities of individuals, but also action directed towards changing social, environmental and economic conditions so as to alleviate their impact on public and individual health. Health promotion is the process of enabling people to increase control over the determinants of health and thereby improve their health.

(WHO 1998 pp 1–2)

While seemingly disparate the two explanations are both valid because they offer definitions that are applicable in different contexts. O'Donnell's definition can be applied to health promotion for specific people with a specific purpose, for example, diabetes education for a newly diagnosed person with diabetes or antenatal classes for prospective parents. The WHO definition, on the other hand, applies to population approaches to health promotion in which the social determinants of health, like housing, employment and education, are addressed in order to improve the health of individuals and communities.

Health promotion, therefore, is a term that can be broadly interpreted and applied to a variety of healthcare practices and research activities that range from promoting wellbeing and preventing illness through to rehabilitation and recovery from illness. Also in this chapter health promotion will be presented as distinct from illness prevention. Health promotion is defined here as being concerned with fostering protective factors for health, while illness prevention is concerned with identifying, reducing and responding to the risk factors for illness.

Protective and risk factors

Rickwood (2006), in distinguishing protective and risk factors for mental health and illness, states that protective factors reduce the likelihood of a mental disorder developing by reducing the exposure to risk, and by reducing the effect of risk factors for people exposed to risk. Protective factors also foster resilience in the face of adversity and moderate against the effects of stress. Risk factors, however, increase the likelihood that a mental disorder will develop, exacerbate the burden of an existing disorder and can indicate a person's vulnerability. Both protective and risk factors comprise individual characteristics and social influences including biological, behavioural, sociocultural and demographic conditions. Individual attributes include genetics, disposition and intelligence, while external drivers comprise the social determinants of health related to social, economic, political and environmental factors including the availability of opportunities in life and access to health services (Provencher & Keyes 2011).

Protective factors assist people to maintain physical, emotional and social wellbeing, and to cope with life experiences including adversity. They can provide a buffer against stress as well as being a set of resources to draw upon to deal with stress. Factors that have been identified as protective for healthy development in children include, for example: easy temperament, family harmony, positive social networks (e.g. peers, teachers, neighbours); access to positive opportunities (e.g. education); and religious faith (Commonwealth of Australia 2009).

Risk factors increase vulnerability to illness and injury and work against recovery from the illness or injury. Developmental risk factors in children have been identified as: ‘low birth weight, prematurity, birth injury; delayed development; poverty; low parental education; family conflict; family breakdown; parental alcoholism; and parental mental illness’ (Commonwealth of Australia 2009).

It cannot be assumed, though, that identifying protective and risk factors can lead to accurately predicting who will or will not be healthy. Demographic data, epidemiological data and research findings merely indicate levels of risk and vulnerability in certain populations, or the increased likelihood of some people for particular illnesses – and their interaction is complex. The significant contribution made by health promotion research findings is that it provides evidence for health professionals and policymakers about opportunities for intervention to promote health and wellbeing, and to prevent illness for individuals and populations.

History of health promotion

Health promotion commenced in the 1970s following the identification of lifestyle as being a major contributor to health and illness (Baum 2008) and the development of psychological models for understanding and changing health behaviours. The health belief model (see also Ch 7) was especially influential in early health promotion campaigns and was viewed as the way forward in changing unhealthy lifestyle practices, particularly in relation to diet, physical activity, tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption. Health promotion initiatives, at this time, mainly consisted of: health education and counselling of individuals regarding lifestyle; illness prevention strategies like mass vaccination and screening initiatives; and lifestyle education programs such as stress management.

Psychology and health promotion

Contributions to the field of health promotion by the discipline of psychology have been significant since the 1970s when psychological theories like the health belief model, transtheoretical model and health action process approach were first used in health education and counselling to bring about targeted individual behaviour and lifestyle changes. In later years, with the rise in the prevalence and burden of chronic illnesses in Western countries, the focus of health promotion efforts shifted from reducing mortality to reducing morbidity or the burden of disease (Taylor 2012). Additionally, psychological research that had initially focused on identifying risk factors shifted to understanding and facilitating ‘protective’ factors for health like resilience (Garmezy 1991).

In contemporary health promotion, psychological theory contributes to an interdisciplinary approach across the range of activities at all levels of intervention from that of the individual to that of the wider population. Motivational interviewing, for example, is a psychologically based counselling intervention aimed at changing unhealthy behaviours. It utilises a client-centred, semi-directed approach and focuses on reasons for and against the change to motivate the person to change to a healthier lifestyle (see also Ch 7). In larger scale health promotion interventions behavioural and cognitive principles that are derived from psychological theory are incorporated in mass media health education campaigns, particularly those targeting lifestyle.

Primary health care movement and health promotion

During the 1980s it became apparent that health education and counselling approaches, on their own, were insufficient to bring about the required changes in many instances because people's behaviour is also shaped by the social, political and economic environments in which they live (Braveman et al 2011, Marmot et al 2008). It was at this time that WHO (1986) released its seminal document, the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (see Ch 4), which subsequently became the cornerstone of the health promotion movement. The Charter shifted the emphasis of health promotion from the individual and called on governments and health services to address the wider social, political and economic drivers of health. As a consequence health promotion became located in, and was central to, the emerging primary health care movement.

The shift from an individual to a societal and population focus precipitated a change in perceptions of responsibility for health away from the individual to wider society and the environments in which people live. While both individual and population-focused approaches have a role to play in contemporary health promotion practice, a population approach that addresses the social determinants of health offers greater opportunity to influence health outcomes for a greater number of people. Nevertheless, individual approaches do continue to play a role in assisting people to engage in healthy lifestyle practices and can facilitate the utilisation of strategies of the Ottawa Charter in healthcare practice, for example, the development of personal skills through health education and counselling. Despite originating in the 1980s the Ottawa Charter remains relevant in the 21st century as a framework for health promotion, as evidenced by its frequent citing in the literature and its widespread utilisation in healthcare practice and programs (McQueen 2008).

Levels of intervention

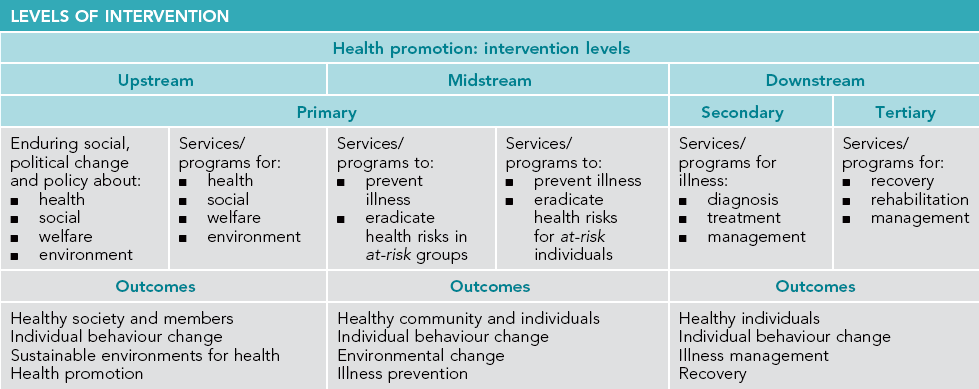

Theories and models for health promotion offer opportunities for intervention at three levels, namely, the level of the individual, the community and at a population level. These are also referred to as downstream (individual), midstream (community) and upstream (population) levels.

The upstream/midstream/downstream distinction is best illustrated by the allegory popularised by John McKinlay, a medical sociologist in the 1970s. McKinlay's tale tells of a physician who was standing by a swiftly flowing river when a drowning man floated past. The physician jumped in the water and rescued the man. However, no sooner had the physician rescued the man when another drowning person came by. Repeatedly, the physician rescued and resuscitated drowning people as they floated past. In fact the physician was so busy rescuing the drowning people that he did not have time to go upstream to see who was pushing them in (McKinlay 1974). This frequently repeated scenario is now an enduring primary health care metaphor that illustrates that while downstream interventions are effective in responding to a health problem they do nothing to address the actual upstream cause of the problem.

The medical model operates primarily as a downstream approach in which people with health problems seek assistance from their general practitioner (GP) or the healthcare system. An exception is mass immunisation programs, which are a biomedical intervention with an illness prevention focus. Downstream approaches also occur mainly at the individual level. Downstream approaches are generally limited to disease-specific interventions such as dietary advice to lower cholesterol. Midstream interventions operate at a local community level and utilise education and intervention strategies to prevent illness. Upstream interventions operate at a societal level whereby social policy and planning is utilised to address the social determinants of health and to re-dress social inequities. Psychosocial models, including primary health care, operate at all three levels. Table 13.1 summarises intervention levels in health promotion and Table 13.2 cites examples of upstream, midstream and downstream approaches to addressing poor nutrition to promote heart health as outlined by Raine (2010).

Table 13.2

ADDRESSING POOR NUTRITION TO PROMOTE HEART HEALTH

| Upstream | Midstream | Downstream |

| Policy change to improve nutritional value of food (similar to tobacco legislation) | Workplace weight-reduction programs and education | Dietary education to assist individuals to eat healthy food |

| Tax unhealthy foods | Improve access to healthy foods by offering healthy options in workplaces and school canteens | Shopping advice regarding choosing healthy food |

Primary, secondary and tertiary interventions

The terms primary, secondary and tertiary prevention are used to distinguish between levels of intervention that foster wellness, treat illness and restore function following illness (recovery) (McMurray 2011). According to Kaplan (2000) primary prevention is distinct from healthcare service delivery, which is the provision of treatment for health problems. At each level of intervention the goal of health promotion is to ensure that public policy is healthy, environments are supportive of health, community action is strengthened, personal skills are developed and that health services are reoriented. In other words, that the strategies for health promotion as articulated in the Ottawa Charter (WHO 1986) are implemented.

Primary prevention

Primary prevention aims to foster wellbeing and prevent the occurrence of illness. It includes both midstream and upstream strategies. Midstream strategies focus on ‘at-risk individuals’ and ‘at-risk groups’, with the goal of changing the individual's risky behaviour, like ceasing tobacco smoking or reducing risk in the community (by improving access to healthcare services for people who live in regional areas, for example). Further examples of population-focused primary prevention include mass vaccination programs, legislation to protect vulnerable members of the society such as anti-discrimination laws, social inclusion policy and economic policies to fund health screening and public housing.

Secondary prevention

Secondary prevention refers to interventions that are, in the main, delivered downstream when symptoms, injury or illness are identified and treated as early as possible to restore health. It includes the range of health services that the general public will be most familiar with, for example, attending an emergency department when injured or visiting a GP when symptoms are present.

In addition to treating illness and health problems a further goal of secondary prevention is early intervention. Hence, some interventions will occur midstream, such as health screening like mammograms, or hearing tests for infants. In this instance the purpose of early intervention is to identify and address health issues before they become a problem or to minimise the impact of an illness or disability on the individual. An example of the effectiveness of early intervention was demonstrated by Hakama et al (2008) whose research found that the incidence and mortality rates of cervical cancer was significantly reduced through population screening by undertaking cytological smears.

Tertiary prevention

Tertiary prevention is also a downstream approach and is implemented when the disease cannot be cured or the illness process is prolonged. Its aim is to assist individuals (and their family and carers) to cope with a change in their health status, to limit disability from the health problem and to promote health and quality of life (recovery). Interventions include: treatment programs for chronic illnesses like emphysema and irritable bowel syndrome; rehabilitation and recovery programs for conditions like mental illness, post-coronary heart disease and post-stroke; and palliative care for terminal illnesses like cancer and dementia.

Recovery, which is a goal of tertiary prevention, is a concept that evolved as part of the reform of mental health services that has occurred in Western countries over recent decades. A recovery approach has subsequently become an integral component of mental health clinical practice (Slade 2009). Recovery for the client refers to living well with a chronic illness or disability. It may include learning about the condition and what triggers episodes, and making lifestyle changes. For health professionals it means not only working with clients to manage the symptoms of care problems, but also to work in collaboration with clients to manage a life lived well despite illness or disability. The approach acknowledges that lifestyle and the social context of people's lives can positively or negatively influence the course of the ongoing illness. Hence, a recovery approach encompasses more than merely treating or managing the symptoms of the illness. It also includes recognition of and attention to social, economic and political aspects of people's lives. In a recovery-focused model of care health professionals and clients work together in partnership to maximise the quality of life for the person living with the ongoing illness (see also Ch 9).

While, to date, the recovery model has mainly focused on minimising the disability from mental illness and to enable people with mental illness to live a fulfilling life despite their condition, the approach does have wider applicability for people who live with other chronic illnesses and for those health professionals who work with people living with a chronic illness or disability. An example of a recovery-focused tertiary intervention that has a broad application is the ‘Flinders ProgramTM’ of chronic disease self-management developed by health professionals and researchers at Flinders University, Adelaide. The model is underpinned by cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) principles. It utilises a partnership approach in which health professionals and clients collaborate on problem identification, goal setting and developing an individualised care plan. The model has proved to be effective in facilitating self-management among people with chronic health conditions and improves health-related behaviour and health outcomes (Harvey et al 2008).

In summary, health promotion can be implemented at primary, secondary or tertiary levels to target individual, community or population health needs. Secondary and tertiary approaches are effective in diagnosing, treating and managing illness. However, as McKinlay's (1974) primary health care metaphor tells us, responding to health problems with a treatment response will deal with the symptoms but not necessarily the cause of the health problem. Therefore, in order to address the cause of a health problem, it is evident that primary intervention, alongside treatment and recovery models, is required. See Table 13.2, which summarises the health promotion levels of intervention.

Evidence for health promotion

There is now a growing and convincing body of evidence that shows that the health of individuals, communities and populations are influenced by a broad range of factors, many of which are outside the health sector. Research findings also demonstrate that social and economic factors have more influence on health outcomes than lifestyle or healthcare (Keleher & MacDougall 2011, WHO 2008). The challenge though is to undertake research that demonstrates that health promotion interventions make a difference to the health of individuals and communities. Difficulties in delivering evidence include the multifactorial nature of many health problems and the length of time (often decades) that elapses before outcomes are seen. Nevertheless, evidence is available to support the effectiveness of specific health promotion interventions for some health issues. One of these specific interventions – reduction of tobacco smoking – will now be examined.

Evidence for health promotion: tobacco smoking

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) tobacco smoking is ‘the single most preventable cause of ill health and death in Australia’ (AIHW 2012 p 221). It is responsible for more admissions to hospital and deaths than illicit drug use and alcohol combined, and accounts for 9.6% of the disease burden in men and 5.8% in women (7.8% overall). Illnesses for which smoking is a major risk factor include coronary heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, stroke and cancer (AIHW 2010 pp 67, 86).

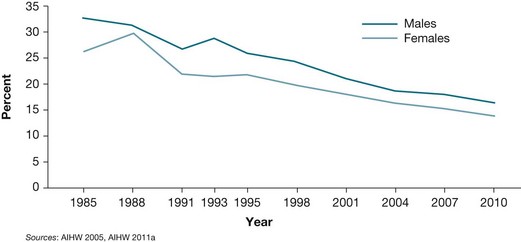

Since the 1980s public health programs with a whole-of-population focus have targeted tobacco smoking cessation and successfully reduced smoking rates in developed countries. In Australia the daily smoking rate, which is now among the lowest for OECD countries, dropped from one in three adults in 1985 to less than one in five in 2010 and the level continues to fall (AIHW 2012). Health promotion initiatives since the 1980s have successfully reduced smoking from 33% in 1985 for men to 18% in 2010, and from 26% in 1985 for women to 15% in 2010 (see Fig 13.1).

Figure 13.1 Daily smokers aged 14 years and over, 1985–2010 Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's health 2012, Cat. no. AUS 156 p. 223

This outcome has been achieved by not just one strategy but by several interventions interacting together to achieve the reduction in the percentage of the population who smoke tobacco. Health promotion strategies to reduce tobacco smoking have included a range of activities such as: increased taxation; restriction of advertising; health education in schools; social marketing in the mass media that utilises both education and fear appeal principles (graphic images on tobacco products); legislation (the banning of smoking in public places); and access to QUIT programs and other supports for smokers who wish to give it up. In summary, several Ottawa Charter strategies have been used concurrently to reduce smoking.

Health promotion approaches

Health promotion is delivered through interdisciplinary and intersectoral activities that are influenced and driven by the underlying values, theories and research findings of the relevant discipline. Interventions, therefore, vary enormously depending on the disciplinary approach and whether the interventions target individuals, communities or whole populations. Biomedical approaches, for example, identify causative factors within the individual and their environment to prevent illness (e.g. provision of clean water supply and immunisation) or early identification and intervention (health screening). Psychological theories of behaviour change, as discussed in Chapter 7, are utilised in health education and counselling approaches to assist people to engage in behaviours that contribute to a healthy lifestyle. A social determinants approach incorporates primary health care values and practices, is underpinned by social justice principles and aims to reduce health inequities and thereby improve the health of a population and its members. Each lends itself to different approaches to health promotion, which will now be examined. These are health education, social determinants/health inequities, settings for health promotion and population-focused approaches.

Health education

Health education is a health promotion strategy that generally refers to a process of enabling people to make behaviour and lifestyle changes (Baum 2008). It can be delivered in a one-on-one situation (such as health counselling) in the form of dietary advice from a nutritionist, in a group setting, for example, parenting classes, or through population-focused interventions such as social marketing media campaigns like television media advertisements to discourage drink driving or gambling. In the main these interventions utilise cognitive and behavioural strategies derived from psychological theory.

While health education is a common approach to health promotion it is also one of the most problematic because educating people about what they should do does not address the social and economic environments in which they live and that shape their behaviour (Keleher & MacDougall 2011). This critique applies particularly to early health education approaches that were delivered in the traditional biomedical model. This model was concerned with compliance and positioned the client in a dependent role with the health professional expert. Subsequent client-centred models, like the Flinders ProgramTM for chronic condition self-management, engage the client in a partnership regarding decision making about management of the health issue.

Health education can also be undertaken by adopting a population approach that targets whole communities through strategies such as social marketing. This approach uses marketing principles and theory from the disciplines of psychology, sociology and communications to identify solutions to social and health problems, and to encourage individuals and populations to lead healthy lifestyles. Successful social marketing campaigns have been undertaken, for example, to promote wearing seatbelts in cars, bicycle helmets while cycling and using sun protection. Campaigns are generally carried out through the media, which is the primary source of health information for most Australians (Janda et al 2007).

Health education: a population approach

Australia has the highest rate of skin cancer in the world, mostly caused by over exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Around 380,000 people are treated for skin cancer and 1600 people die from the disease every year (SunSmart Victoria 2012). In 1981, in response to this alarming statistic, Australia introduced a social marketing health campaign titled ‘Slip-Slop-Slap’, which was led by a seagull named Sid. Australians were encouraged to ‘slip on a shirt, slop on sunscreen and slap on a hat’ before venturing outdoors to prevent sunburn and skin cancer. The campaign included print and television media advertisements, a jingle, education resources for school teachers and visits by the mascot, Sid Seagull, to schools and public events. A similar campaign was undertaken in New Zealand where the mascot was a lobster (SunSmart NZ 2012). In subsequent years seeking shade and wearing sunglasses were added to the health message and people are now encouraged to ‘slip, slop, slap, seek (shade) and slide (on sunglasses)’.

Following this public health campaign the incidence of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), the most common forms of skin cancer, were reduced. However, the incidence of melanoma, which is the most fatal form of skin cancer, was not affected. This is most likely because the use of sunscreen does not prevent the development of melanoma, whereas sunscreen prevents BCCs and SCCs by preventing sunburn (Planta 2011). It is therefore a false confidence for a person to believe that applying sunscreen will provide protection against all forms of skin cancer.

Furthermore, despite the overall decrease in skin cancer rates, another health issue has arisen as a consequence of reduced sun exposure. Vitamin D deficiency, which predisposes people to increased risk of bone fractures, particularly in later life, has been observed in some sections of the population, especially the elderly, people with dark skin, and people who cover their body in clothing for religious or cultural reasons (Hedges & Scriven 2008, Henry et al 2007). Vitamin D deficiency is linked to insufficient sun exposure, and sunlight is the major source of vitamin D for Australians and New Zealanders. It seems that the prevention of one health problem may predispose a person to another.

These findings highlight the importance of evaluating health promotion interventions to ascertain that the intervention has the required outcome, and that other unwanted effects do not occur. Even interventions that have intuitive appeal and can demonstrate positive health outcomes (e.g. the SunSmart campaign) may not be effective for all people or all forms of skin cancer. And for some population groups, like the elderly, the intervention may have other unwanted side effects (e.g. reducing uptake of vitamin D).

Finally, while psychological behaviour change models and psychosocial principles are used in health education approaches, the social determinants of health as identified by WHO (2008) are not necessarily addressed in behaviour change programs and these may be more influential in determining lifestyle choices, as was found in the Whitehall study (see Ch 10) (Marmot et al 1997, WHO 2008). Finally, considering the inconclusive results from health education initiatives to promote health, Keleher suggests that in order for health education to be effective it must move beyond the advice giving – knowledge transfer – symptom-control model to one of empowerment (Keleher & MacDougall 2011) that is inherent in a social determinants approach.

Social determinants/health inequities approach

Social determinants refer to the ‘wide range of social (including economic and political) conditions that are strong influences on health, such as wealth and educational attainment of the family into which one is born, neighbourhood social conditions, and the social policies which determine these conditions’ (Schrecker et al 2010 p 33). A social determinants approach to health promotion addresses health inequities and is, therefore, underpinned by the principles and values of social justice, equity and respect for the rights of others. There is recognition that drivers outside the health arena influence health outcomes and a commitment to working in partnership with individuals and communities. In this approach health – not medicine – is the focus (Braveman et al 2011). The WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health report (WHO 2008) advocates strongly for a social justice approach to health that includes recognising and addressing health inequities.

Given the range of social determinants that impact on health, it is evident that at a government level the health portfolio alone cannot sufficiently redress these. This was reinforced in the recommendations made to the South Australian Government by the 2010 South Australian Thinker in Residence, Ilona Kickbusch, which stated that a whole-of-government approach was required including input from the portfolios of justice, transport, education, employment, housing and welfare (Kickbusch & Buckett 2010a, 2010b). In conclusion, health promotion that utilises a social determinants approach to address health inequities ‘is the process of enabling people to increase control over their health, resulting from the synergy of healthy policy in all sectors of society and health education for all’ (Mittelmark et al 2008 p 225).

Health inequities

Health is essential to wellbeing and quality of life, therefore, health inequities further disadvantage groups of people who are already socially disadvantaged due to poverty, gender or being a member of a disenfranchised racial, ethnic or religious group. Furthermore, equity is a social justice principle and closely related to human rights (Braveman 2010). The Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (2011) defines health inequity as the ‘unfair and avoidable differences in health status between different populations of people that are ‘evident through a range of measures, including illness and death rates, and self-reported health status’. Three dimensions of inequality are identified by the foundation, all of which need to be addressed to overcome health inequalities. They are:

1. Inequality of access – as a result of barriers to support services required for health and wellbeing. This can result from costs of the service, lack of transport to the service, services that are inaccessible for people with special needs and services that are culturally inappropriate for some population groups.

2. Inequality of opportunity – as a result of social, geographic or economic resources for health including education, employment and suitable housing.

3. Inequality of impacts and outcomes – differences in health outcomes between groups and populations such as mortality and morbidity rates or self-reported health rates (Victorian Health Promotion Foundation 2011).

Redressing health inequities for Indigenous people

Indigenous Australians and New Zealand M ori experience poorer health outcomes than the non-Indigenous people of these two countries. In addition to health inequities, many Indigenous people also experience disadvantage regarding education, employment status, economic status, housing and lack of appropriate environmental infrastructure (Baum 2008). Therefore, when planning and implementing health promotion with Indigenous people it is essential that social justice and human rights be incorporated because social conditions, health equity and human rights are interrelated (Braveman 2010).

ori experience poorer health outcomes than the non-Indigenous people of these two countries. In addition to health inequities, many Indigenous people also experience disadvantage regarding education, employment status, economic status, housing and lack of appropriate environmental infrastructure (Baum 2008). Therefore, when planning and implementing health promotion with Indigenous people it is essential that social justice and human rights be incorporated because social conditions, health equity and human rights are interrelated (Braveman 2010).

VicHealth, in collaboration with Aboriginal Affairs Victoria, conducts an Indigenous leadership health promotion program to support the development of young Indigenous leaders in order to promote the emotional and spiritual wellbeing of Indigenous communities in Victoria. The goal of the program is to build leadership potential among young people and to enable young Indigenous people to develop the skills required to combat experiences of discrimination, and to enable positive futures for the participants. The program is conducted in metropolitan and rural areas across Victoria and provides a range of personal development projects based in leadership training, mentoring by senior community members, support and providing resources to develop leadership skills and access to participation in a range of community and professional activities (VicHealth 2005).

In New Zealand health promotion practice takes account of the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi, which is the country's founding contract between M ori and the Crown and the 1986 Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. M

ori and the Crown and the 1986 Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. M ori health is understood as a holistic concept in which health is recognised as being dependent on a balance of factors that influence wellbeing. These contributing factors include spiritual (wairua), mental (hinengaro), physical (tinana), language (te reo rangatira) and family (whanau), which interact to enable wellbeing, as does the environment (te ao turoa). Therefore, in understanding M

ori health is understood as a holistic concept in which health is recognised as being dependent on a balance of factors that influence wellbeing. These contributing factors include spiritual (wairua), mental (hinengaro), physical (tinana), language (te reo rangatira) and family (whanau), which interact to enable wellbeing, as does the environment (te ao turoa). Therefore, in understanding M ori health, it is evident that the social, economic and cultural position of M

ori health, it is evident that the social, economic and cultural position of M ori must be taken into account, and that for M

ori must be taken into account, and that for M ori, health promotion means taking control of their own health to determine their own wellbeing (Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand 2012).

ori, health promotion means taking control of their own health to determine their own wellbeing (Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand 2012).

Settings for health promotion

A settings approach to health promotion was advocated in the Jakarta Declaration as the ‘organisational base of the infrastructure required for health promotion’ (WHO 1997). A settings approach to health promotion facilitates the nurturing of human and social capital. It involves providing health promotion in the settings of people's lives, such as schools, families, workplaces, ethnic communities and regional localities – thereby taking health services to the people, and not expecting people to be entirely responsible for their health outcomes. It broadens the population approach to include organisations and systems (McMurray 2011).

Health promotion settings: schools

In 1995 WHO established the Global School Health initiative to promote and support the health and wellbeing of children. The Health Promoting Schools program strives to develop the capacity of schools as a healthy setting for living, learning and working, with a focus on: caring for oneself and others; making healthy decisions and taking control over life's circumstances; creating conditions that are conducive to health (through policies, services, physical/social conditions); building capacities for peace, shelter, education, food, income, a stable ecosystem, equity, social justice and sustainable development; preventing leading causes of death, disease and disability (e.g. helminths (worms), tobacco use, HIV/AIDS/STDs, sedentary lifestyle, drugs and alcohol, violence/injuries and unhealthy nutrition); and influencing health-related behaviours (e.g. knowledge, beliefs, skills, attitudes, values and support) (WHO 2012b). Health promoting schools foster happy, healthy, supportive and caring environments for students, staff and families (Ministry of Health New Zealand n.d.).

The Walking School Bus is an example of a health promotion initiative that is conducted in the school setting and aims to foster independent mobility in children. It comprises a group of children who walk to and from school under the supervision of one or more adults on a set route each day. Children ‘board’ the ‘bus’ at designated stops on the route. Additional outcomes include increased physical activity, knowledge of road safety, familiarity with the local area and social interaction (Commonwealth of Australia 2005).

Health promotion settings: workplace

The Jakarta Declaration identified health promotion as an investment and the workplace as a potential setting in which it could be implemented (WHO 1997). Implementing health promotion not only offers advantages to workers in the form of improved health and wellbeing, but employers also gain by reduced absenteeism and fewer worksite accidents and workers' compensation claims.

The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion states that work has ‘a significant impact on health’ and can be ‘a source of health for people’ because ‘the way society organizes work should help create a healthy society’ (WHO 1986 p 2). Yet, despite this social framework for action provided by the charter, workplace health promotion has concentrated more on programs that aim to bring about individual behaviour change for healthy lifestyles, or the screening of ‘at risk’ populations, that is, illness prevention, rather than promoting health and wellbeing (Noblet & Rodwell 2010, Talbot & Verrinder 2009). This is evident in the mental health field when programs that claim to promote mental health are designed with the aim of enhancing individual skills and attitudes, or developing coping strategies, and rarely utilise health promotion methods of participation, empowerment and structural change.

Also, despite the introduction of legislation and workplace policies, structural changes have been unsuccessful in bringing about environmental modification, which fosters mental wellbeing. Bullying continues to be endemic in many work settings and research demonstrates that it affects the physical and psychological health of victims, and negatively affects their work performance (Johnson 2009). Nevertheless, while mental health promotion is appealing, there are challenges to implementing it in the workplace. These include difficulties of demonstrating the efficacy of interventions and competition for the health dollar. Additionally, entrenched institutional structures may work against change when institutions have an investment in maintaining the status quo or fear the uncertainty of change.

Population health promotion approaches

Population refers to a group of people who are bound by a common theme. This may be ethnicity, culture, geographic location, workplace or demographic characteristics like age, gender or socioeconomic status. Disparities in health exist between different populations (WHO 2008), therefore the goal of a population approach to health promotion is to reduce difference in health status and to reduce inequities and improve the health of the whole population. This approach developed following the growing awareness that factors outside an individual's control, and drivers outside the health arena, influence health outcomes. Consequently, models and approaches to health promotion shifted from being individual to population-focused.

According to Whitehead (2007) population-wide approaches target the whole of the population through: interventions that target individual behaviour (e.g. through health information social marketing campaigns); structural mechanisms and macroeconomic policies (e.g. the provision of public housing or through tobacco taxation); or interventions that address the causes of ill health (e.g. by providing free education to all citizens). Population approaches aim to improve the health of members of the group by facilitating protective factors and reducing risk factors by addressing health inequities.

Populations in Victoria, Australia, for example, that have been identified as experiencing the greatest health inequities and therefore the greatest need for intervention, include: Indigenous people; newly arrived migrants and refugees; people with disabilities; people from low socioeconomic backgrounds; and children and young people living in low socioeconomic areas (Victorian Health Promotion Foundation 2008 p 6).

Population approach: healthy cities

Healthy Cities is a global movement that originated out of the WHO European office, with the aim of implementing the Ottawa Charter at a city level. There are now Healthy Cities in the six WHO regions, namely, Africa, East Mediterranean, Europe, the Americas, South East Asia and the Western Pacific. The movement encourages local governments to engage in health development through political commitment, institutional change, capacity building, partnership-based planning and innovative projects. Projects strive to be broad-based, intersectoral, ecological and political, are innovative and encourage community participation.

Through its Healthy Cities Project WHO identified 10 key social and political areas that influence health, namely, the social gradient, unemployment, stress, social support, early life, addiction, social exclusion, food, transport and work. The organisation's publication of Social Determinants of Health: the solid facts is intended ‘to ensure that policy – at all levels in government, public and private institutions, workplaces and the community – takes proper account of recent evidence suggesting a wider responsibility for creating healthy societies’ (Wilkinson & Marmot 2006).

Healthy Cities promotes an approach to policy and planning that is comprehensive and systematic and emphasises the importance of addressing health inequalities and urban poverty (the needs of vulnerable groups). Its approach encourages participatory governance and takes account of the social, economic and environmental determinants of health. Healthy Cities also strives to put health issues on the agenda regarding economic policy and urban development efforts such as establishing dedicated bikeways to improve safety for cyclists and to facilitate community members' engagement in physical activity. Healthy Cities is now in its fourth phase and participating cities are currently working on three core themes: healthy ageing, healthy urban planning and health impact assessment. In addition, all participating cities focus on the topic of physical activity/active living (WHO 2012a).

Challenges of a health promotion approach

Despite health promotion having intuitive appeal to policymakers, health professionals and laypeople (as evidenced by colloquial sayings like ‘prevention is better than cure’), and research findings that demonstrate health promotion effectiveness, there remain challenges regarding the implementation and effectiveness of health-promoting initiatives. These include blaming individuals for lifestyle and health outcomes and issues in translating research findings into healthcare practice.

Strategies that target individuals' health behaviour, such as health education and social marketing, have the potential to lead to ‘victim blaming’ should the person not alter their behaviour following the intervention. Attributing responsibility for the health problem solely to the individual overlooks the social and external forces that also contribute to the continuation of the behaviour and stigmatises the individual whose health problems are deemed to be their own fault. Furthermore, making the individual responsible for their own health may absolve the state and health services of responsibility in addressing the health issue or the social and political factors that contribute to it.

Population approaches, too, can be problematic. The lead time for demonstrating the effectiveness of population-focused interventions is long – often decades (Jirowong & Liamputtong 2009, McQueen 2008). Given that decisions regarding health funding allocation are made in a political environment in which the term of the governing political party that allocate the funding is only three to five years, funding decisions may consequently be made that favour initiatives that deliver shorter term outcomes and these tend to be treatment rather than prevention- or promotion-focused.

A further issue with the long lead time to demonstrate effectiveness is the range and complexity of intervening factors that may contribute to the health outcome. The breadth of contributing factors poses a challenge in deciding which factors should be addressed and which factors will or will not receive funding. Moreover, the allocation of funding may be made on the magnitude of community demand, which may only be the most vocal need rather than the most pressing one.

Conclusion

Health and health outcomes are influenced by a range of factors that are located both within the person and within the contexts and environments in which people live. In this chapter health promotion was presented as an interdisciplinary field of endeavour that seeks to influence health outcomes by facilitating wellbeing, preventing illness and fostering recovery for individuals and communities, and to thereby enable people to take control of and to improve their health and quality of life. Values that underpin a social determinants approach to health promotion, such as social justice and health equity, were also identified, as were strategies for primary, secondary and tertiary intervention.

The contribution made by psychology and other disciplines was highlighted and the effectiveness of interdisciplinary and intersectoral interventions was emphasised. Finally, contemporary health promotion was located within a social justice and equity framework that sees ‘health for all’, as articulated in the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (WHO 1986), as a basic human right.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's health 2012. Canberra: AIHW; 2012.

Keleher, H., MacDougall, C. Understanding health, fourth ed. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2011.

McMurray, A. Community health and wellness: a socio-ecological approach, fourth ed. Sydney: Mosby; 2011.

Talbot, L., Verrinder, A. Promoting health: the primary health care approach, fourth ed. Sydney: Elsevier; 2009.

World Health Organization (WHO). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health; 2008.

Australian Health Promotion Association

The Australian Health Promotion Association's aim is to provide knowledge, resources and perspectives to improve health promotion research and practice.

Flinders Human Behaviour and Health Research Unit

http://www.flinders.edu.au/medicine/sites/fhbhru/self-management.cfm

FHBHRU provides details of the ‘Flinders ProgramTM’ for chronic condition self-management and links to research and publications.

International Union of Health Promotion and Education

The International Union of Health Promotion and Education aims to support everyone committed to advancing health promotion and achieving equity in health globally. The website contains information about health promotion research, publications and conferences.

Runanga Whakapiki Ake I Te Hauora o Aotearoa / Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand

The Runanga Whakapiki Ake I Te Hauora O Aotearoa/Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand is the national umbrella organisation for health promotion in New Zealand. The forum's mission is ‘Hauora – everyone's right – our commitment’.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's health 2010. Canberra: AIHW; 2010.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's health 2012. Canberra: AIHW; 2012.

Baum, F. The new public health, third ed. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Braveman, P. Social conditions and human rights. Health and Human Rights Journal. 2010; 12(2):31–48.

Braveman, P., Egerter, S., Williams, D. The social determinants of health: Coming of age. Annual Review of Public Health. 2011; 32:381–398.

Carter, S., Rychetnik, L., Lloyd, B., et al. Evidence, ethics and values: a framework for health promotion. American Journal of Public Health. 2011; 101(3):465–470.

Commonwealth of Australia. Walking school bus: a guide for parents and teachers. Online Available http://www.travelsmart.gov.au/schools/pubs/guide.pdf, 2005. [26 Sep 2012].

Commonwealth of Australia. Kids matter: how risk and protective factors affect children's mental health. Online Available http://www.catholic.tas.edu.au/Resources/documents/kidsmatter-1/risk-and-protective-overview.pdf, 2009. [22 Jan 2013].

Garmezy, N. Resiliency and vulnerability to adverse developmental outcomes associated with poverty. American Journal of Behavioral Science. 1991; 34:416–430.

Hakama, M., Coleman, M., Alexe, D., et al. Cancer screening: evidence and practice in Europe 2008. European Journal of Cancer. 2008; 44(10):1404–1413.

Harvey, P., Petkov, J., Misan, G., et al. Self-management support and training for patients with chronic and complex conditions improves health related behaviour and health outcomes. Australian Health Review. 2008; 32(2):330–338.

Health Promotion. Forum of New Zealand – Runanga Whakapiki Ake I Te Hauora o Aotearoa. Online Available www.hpforum.org.nz, 2012. [26 Sep 2012].

Hedges, T., Scriven, A. Sun safety: What are the health messages? Perspectives in Public Health. 2008; 128(4):164–169.

Henry, M., Pasco, J., Sanders, K., et al. Fracture risk (FRISK) score: Geelong osteoporosis study. Radiology. 2007; 241(1):190–196.

Janda, M., Kimlin, M., Whiteman, D., et al. Sun protection messages, vitamin D and skin cancer: out of the frying pan into the fire? Medical Journal of Australia. 2007; 186(2):52–54.

Jirowong, S., Liamputtong, P. Population health, communities and health promotion. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2009.

Johnson, S. International perspectives on workplace bullying among nurses: a review. Journal Compilation International Council of Nurses. 2009; 56:34–40.

Kaplan, M. Two pathways to prevention. American Psychologist. 2000; 55(4):382–396.

Keleher, H., MacDougall, C. Understanding health, third ed. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2011.

Kickbusch, I., Buckett, K. Implementing health in all policies. Adelaide: Government of South Australia; 2010.

Kickbusch, I., Buckett, K. Health in all policies: where to from here? Health Promotion International. 2010; 25(3):262–264.

Marmot, M., Bosma, H., Hemingway, H., et al. Contribution of job control and other risk factors to social variations in coronary heart disease incidence. The Lancet. 1997; 350:235–239.

Marmot, M., Friel, S., Bell, R., et al. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. The Lancet. 2008; 372:1661–1669.

McKinlay, J. A case for refocussing upstream: the political economy of illness. Applying behavioural science to cardiovascular risk. Washington: American Heart Association; 1974.

McMurray, A. Community health and wellness: a socio-ecological approach, fourth ed. Sydney: Elsevier; 2011.

McQueen, D. Self-reflections on health promotion in the UK and the USA. Public Health. 2008; 122:1035–1037.

Ministry of Health New Zealand/ Te Kete Ipurangi and Health promoting school. http://hps.tki.org.nz/ [nd. Online. Available 6 Apr 2012].

Mittelmark, M., Kickbusch, I., Rootman, I., et al, Health promotionHeggenhougen K., ed. International encyclopedia of public health. 2008:225–240. Online Available http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/referenceworks/9780123739605 [20 Sep 2012].

Noblet, A.J., Rodwell, J.J. Workplace health promotion. In: Leka S., Houdmont J., eds. Occupational health psychology. London: Wiley Blackwell, 2010.

O'Donnell, M. The science of health promotion: editor's notes. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2008; 23(2):iv.

Planta, M. Sunscreen and melanoma: Is our prevention message correct. Journal of American Board of Family Medicine. 2011; 24(6):735–739.

Provencher, H., Keyes, C. Complete mental health recovery: bridging mental illness with positive mental health. Journal of Public Mental Health. 2011; 10(1):57–69.

Raine, K. Addressing poor nutrition to improve heart health. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2010; 26(Supp C):21c–24c.

Rickwood, D. Pathways of recovery: a framework for preventing further episodes of mental illness. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2006.

Schrecker, T., Chapman, A., Labonté, R., et al. Advancing health equity in the global marketplace: how human rights can help. Social Sciences and Medicine. 2010; 71:1520–1526.

Slade, M. 100 ways to support recovery: a guide for mental health professionals. London: Rethink Mental Illness; 2009.

Smith, B., Tang, K., Nutbeam, D. WHO health promotion glossary: new terms. Health Promotion International. 2006; 21(4):340–345.

SunSmart New Zealan. www.sunsmart.org.nz, 2012 [Online. Available].

SunSmart Victoria. Sun protection. Online Available www.sunsmart.com.au, 2012. [20 Sep 2012].

Swinburn, B. Obesity prevention in children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2009; 8(1):209–223.

Talbot, L., Verrinder, A. Promoting health: the primary health care approach, fourth ed. Sydney: Elsevier; 2009.

Taylor, S. Health psychology, eighth ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

Toft, U., Kristoffersen, L., Ladelund, S., et al. The impact of a population-based multi-factorial lifestyle intervention on changes in long-term dietary habits: the Inter99 study. Preventive Medicine. 2008; 47:378–383.

VicHealth. Building Indigenous leadership: promoting the emotional and spiritual wellbeing of Koori communities through the Koori communities leadership program. Melbourne: Victorian Health Promotion Foundation; 2005.

Victorian Health Promotion Foundation. People, places, processes: reducing health inequalities through balanced health approaches. Online Available http://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/Publications/Health-Inequalities/People-places-processes.aspx, 2008. [13 Mar 2013].

Victorian Health Promotion Foundation. Health promotion. Online Available www.vichealth.vic.gov.au, 2011. [20 Sep 2012].

Whitehead, M. A typology of actions to tackle social inequalities in health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2007; 61:473–478.

Wilkinson, R., Marmot, M. The social determinants of health: the solid facts, third ed. Geneva: WHO; 2006.

World Health Organization (WHO). The Ottawa charter for health promotion. Geneva: WHO; 1986.

World Health Organization (WHO). The Jakarta declaration on leading health promotion into the 21st century. Geneva: WHO; 1997.

World Health Organization (WHO). Health promotion glossary. Geneva: WHO; 1998.

World Health Organization (WHO), Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health Online. Available, 2008. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/final_report/en/index.html [6 Apr 2012].

World Health Organization (WHO), Types of healthy settings: healthy cities Online. Available, 2012. http://www.who.int/healthy_settings/types/cities/en/index.html [20 Sep 2012].

World Health Organization (WHO), School and youth health: Global school health initiative: What is a health promoting school? Online. Available, 2012. http://www.who.int/school_youth_health/gshi/hps/en/index.html [20 Sep 2012].