CHAPTER 13 Older adulthood

At the completion of this chapter and with further reading, students should be able to

• Discuss the key concepts of older adulthood

• Explain the terms ageism, ageing process, age-related adjustments, dementia

• Understand how cultural factors impact on the ageing process

• Outline psychological, physical and social impacts of ageing on older adults

• Understand the impact of disability on lifestyle choices in older adults

• Identify and describe nursing interventions to promote person-centred care in residential care environments

• State primary functions of nurses in promoting quality nursing care in older clients

Ageing is an inevitable part of life. However, to think of it as something that happens in the seventh, eighth or even ninth decades of life is to miss the point that it is a process, dynamic in all parts, rather than a state, and that ageing extends across the life span. Ageing is a process that accumulates changes in organisms or objects over time. Human ageing involves multidimensional changes on physical, psychological, cultural and social levels. Physiologically, it cannot be avoided or delayed. The physical appearance of an older adult offers only a superficial view of ageing. Nurses, because of their unique work practices and relationships with clients, are in an ideal situation to promote healthy ageing, and to recognise and reinforce wellness as a desired state of ageing.

Some people are born old … others feel young for their whole lives. It is a state of mind … you’re only as old as you feel and I feel like I did when I was 20!

I do not ask to be young again; all I want is to go on getting older.

Konrad Adenauer (First Chancellor of West Germany after World War II. Lived to be 91)

It is reasonable to propose that ageing begins at birth and that we age across the lifespan. For the purposes of this chapter we will view ageing from the point in people’s lives at which they reach maturity during adulthood and at which ageing and development in later adulthood becomes apparent. This occurs around the seventh decade, when people are thinking of, or are actually, retiring from the paid workforce. This is, of course, a generalisation as some people retire in their fifties whereas others are still fully employed or work part-time well into their sixties or their seventies. Chronological age for many is not indicative of when and how they enter the later stage of life (see Clinical Interest Box 13.1).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.1 Categories of older adulthood

Older adulthood is divided into the following categories:

| Young Old (Stage1) | 65–74 years |

| Old Old (Stage II) | 75–84 years |

| Oldest Old (Stage III) | 85 years+ |

| Centenarians (Stage IV) | older adults of 100 years or more |

Theories of development in the twentieth century focused predominantly on children, adolescents and young adulthood. However, in recent decades, far more attention has become focused on the older population, using geriatrics (the study of disease process in older adults) and gerontology (the study of healthy ageing) (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

The state of ageing in Australia and New Zealand

Both Australia and New Zealand are ageing countries: they are middle aged in terms of the average age of the population (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2007; Thornton 2010). In Australia in 2010, people over the age of 65 years constituted 13.5% of the population, (approx. 3 million). Of this 13.5% of the population, 398 000 were over the age of 85 years and 3700 were over the age of 100 years (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2010a). In New Zealand, the projected growth of the population over the age of 65 years (from 2006 to 2026) is expected to increase by 84% from 521 000 to 944 000 older adults (Thornton 2010).

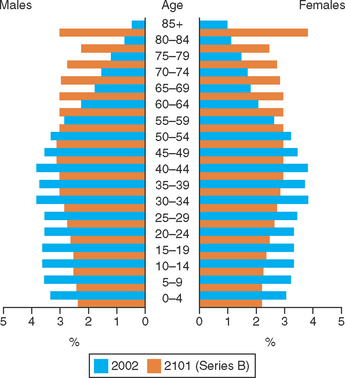

Figure 13.1 indicates the changes expected within the next 100 years in Australia. It illustrates the ‘working population’ (those aged between 16 and 65 years) decreasing in every age category, and a marked increase in population numbers greater than 60 years. To put these figures into context, there will be less of the population working to contribute to the support of the non-working population. This trend was projected many years ago and, in Australia, the implementation of compulsory superannuation, ‘user pays aged care’ and the continual rationalising of healthcare budgets is reflective of current and future trends in available resources (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2010b).

AGEISM

Ageism refers to a set of ideas and beliefs that are associated with discriminatory attitudes directed towards older adults (Quadagno 2011). It implies negative beliefs and stereotypes about older people collectively. Ageism can be apparent in the views others have of older people’s abilities, from a personal, cognitive, social or even professional perspective (Miller 2008).

Ageism is seen in all the categories of ageing, from limitations in employment, to life-changing decisions that must be made in regard to living or lifestyle choices. At no time should age be a factor in not empowering an older person to be involved in decision making. With the increasing number of older people in developed countries, ageism may face some opposition (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

The process of ageing can be viewed from the perspective of physical, social, psychological, functional and emotional ageing. Most people will follow as individuals a path in ageing, as the followed one in growth and development in their younger years. There is no one theory of ageing, but a number of theories have been developed to explain the ageing process. Biological theories look at the physiological and anatomical changes that occur, while psychological theories seek to explain the thought processes and behaviours of older people (Crisp and Taylor 2009).

Physical changes

The body’s organs and systems undergo changes as they age. These changes alter susceptibility to various diseases. Changes are often difficult to identify with just one individual system because of the inter-relatedness of the body organs, systems and functions. Understanding these processes is important for nurses because many of the effects of ageing are first noticed in body function.

Neurological and sensory systems

The nervous system has some distinctive age-related changes, but the origin of these changes may be attributed to other body system variations, such as reduced cerebral circulation attributed to cardiovascular weakening (Eliopoulos 2010). (See Clinical Interest Box 13.2.) What is evident is that there is a decline in brain weight and circulation; however, there is scant evidence that thinking and behaviour are affected early in later adulthood. Neurons, nerve fibres and cerebral circulation will decrease. Efficiency of function of the hypothalamus is altered. Lens, pupil size and corneal and retinal changes will affect visual acuity, and atrophy and sclerosis in tympanic membrane and inner ear structures will impact on hearing.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.2 Neurological and sensory systems

Vision: inability to focus or accommodate properly (presbyopia), changes in clarity and density to the lens (cataracts), narrowing of visual field (decreased peripheral vision), decreased ability to adjust to dim light, alteration to blood supply to retina (can cause macular degeneration)

Hearing: presbycusis develops (progressive hearing loss, especially high frequency sounds, progressing to low and mid-range sounds), accumulation of cerumen (ear wax)

Taste/smell: approximately 50% of all older adults experience some loss of their ability to smell. Taste acuity is dependent on smell; decreased saliva production and effects of medication may cause loss of sensitivity to taste and perception of food may be altered

Slower reflexes: delayed responses to multiply stimuli, alterations to balance and coordination may increase the risk of falls

Body temperature: regulation is less effective because of decreased function of hypothalamus, with delayed thirst, atrophy of sweat glands, decreased muscle-fat ratio

Quality of sleep (especially in stages III and IV): sleep is altered due to circadian and homeostatic factors

Tactile sensation: sensation and response to pressure and pain are reduced

Integumentary system

Flattening of the dermal-epidermal junction, reduced thickness and vascularity of the dermis and loss of collagen and uniformity of fibres make skin less elastic. Skin becomes thinner, and the change in lean-muscle-to-fat ratio means that skin is more at risk from bony prominences underneath it (Berman et al 2012). There is a reduction of melanocytes, the skin’s immune system diminishes, sweat glands atrophy and heat receptors that have typically been spread through the dermis are less receptive, resulting in delayed recognition of heat on the skin. Growth rate of hair declines (head, pubis, axillary), but facial, eyebrow, ear and nasal hair becomes more prominent in men. (See Clinical Interest Box 13.3.)

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.3 Integumentary system

As the skin becomes less elastic, it becomes drier and more fragile, increasing the risk of tearing

As subcutaneous tissue is lost, skin sags, wrinkles and becomes more irritated and more at risk of infection

Nails become brittle and growth decreases

Thinning and baldness of hair in men, greying of hair due to loss of pigment

Skin pigmentation due to clumping of melanocytes

Cardiovascular system

The heart muscles decrease in efficiency and contractile strength with age. Left ventricular hypertrophy is slight, but the aorta thickens and dilates, as do the atrioventricular valves, causing sclerosis and fibrosis. Cardiac output is reduced. Valve closure may become incomplete, causing systolic and diastolic murmurs (Eliopoulos 2010). Arteries stiffen with age, decreasing their properties of stretch and contractility, creating more resistance for the heart to pump blood through them. Veins, conversely, become less rigid and are less resistant, therefore bulging and pooling is experienced. (See Clinical Interest Box 13.4.)

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.4 Cardiovascular system

Blood pressure increases to compensate for increased peripheral resistance and decreased cardiac output (particularly systolic)

Hypertension predisposes older adult to heart failure and coronary disease, renal disease, peripheral vascular disease, stroke

Less efficient utilisation of oxygen results in less available energy, especially with strenuous exercise

Increased heart rate occurs when body is affected by anxiety, excitement, illness or strenuous activity, and there is a longer period until baseline heart rate returns

Peripheral pulses are weaker and lower extremities may be cooler

Respiratory system

As a result of age-related structural changes in the chest (see also ‘Musculoskeletal system’ below), there is a reduction in respiratory activity and efficiency. Costal cartilage calcification makes the rib cage and trachea more rigid and the anterior and posterior diameter of the chest cavity increases and, with osteoporotic changes, the appearance of kyphosis (sometimes referred to as a dowager’s hump) may be seen, particularly in women (Crisp & Taylor 2009). The inspiratory/expiratory muscles are weaker, causing a decrease in lung expansion and vital capacity and there is a decrease in strength of cough and laryngeal reflexes. In the lungs, cilia are reduced in number and effectiveness, and less elastic alveoli result in increased difficulty in clearing secretions. The maximum capacity of the lungs may decrease as much as 40% between the ages of 20 and 70 years. Spontaneous alveoli destruction increases in rate. Available energy is decreased (in conjunction with the cardiovascular system) and exercise/activity tolerance is decreased. There is increased risk of infection because of decreased efficiency in clearing secretions and expelling accumulated material and increased prevalence of shortness of breath because of decreased vital capacity (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Gastrointestinal system

Changes in the gastrointestinal system are identifiable at most levels and they may create a greater need for adaptation than do some of the other body systems. Changes can be noticed in the mouth. These changes affect the condition and effectiveness of teeth and may cause the tongue to atrophy, a decrease in production of saliva by up to two-thirds and changes to cheek musculature, which can impact on the mechanical breakdown of food and swallowing (Eliopoulos 2010). Gag reflex and oesophageal motility are diminished; in addition there are changes to gastric mucus and production of bicarbonate, which will impact on the pH of the stomach. Intrinsic factor may stop being produced (Farley et al 2006). Abdominal muscles become weaker and there is a decreased tone and peristalsis in the intestines. This means there is an increased tendency for constipation. The effects of medication may change because of changes in the metabolism capacity of the liver (Miller 2008; McCance & Huether 2006). (See Clinical Interest Box 13.5.)

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.5 Gastrointestinal system

Teeth enamel becomes harder and more brittle

Increasing numbers of cavities and the bones supporting teeth decrease in height and density

Flattening of chewing cusps occurs

Taste sensation becomes less acute

Increased risk of aspiration due to altered gag response

Risk of pernicious anaemia due to diminished or absent intrinsic factor

Musculoskeletal system

Muscle tissue atrophies and muscle strength and tone diminish in proportion to the decline in muscle mass. Joints become less elastic and flexible with the loss and calcification of cartilage. There is an alteration to the equilibrium between bone deposition and resorption, and in postmenopausal women, decreased oestrogen increases bone resorption and decreases calcium deposition (Farley et al 2006). The loss of bone density particularly affects long bones and vertebrae. The curve of the lower back changes, resulting in a change to the centre of gravity (Crisp & Taylor 2009). There is a loss of lean muscle tissue which is converted to fat. Basal metabolic rate (BMR) can decrease during mid to later adulthood; therefore an increase in body weight may be experienced early in later adulthood. Body fat moves deeper in the body with ageing. Body heat is less effectively retained. Muscle activity associated with shivering to increase body temperature is less efficient (Eliopoulos 2010). Thermoregulation is compromised (by the age-related changes in the cardiovascular, integumentary, neurological and musculoskeletal systems). Age-related changes may affect mobility and safety. The older adult is at increased risk of falls and fractures. (See Clinical Interest Box 13.6.)

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.6 Musculoskeletal system

Fibrous tissue gradually replaces muscle

Arm and leg muscles become particularly flabby and weak when the person becomes less active

Muscle cramps are more prevalent

Increased brittleness of bones, bone loss and decreased bone density, increasing the risk of fractures and damage from only minor trauma

Increased risk and prevalence of osteoporosis

Reduction in height and appearance of kyphosis

Limitation to joint mobility, appearance of spurs and points on bone ends, limiting motion and activity and increasing joint pain

Urinary system

Overall, kidney function decreases with age, although even with a 50% reduction, the body can function adequately in the absence of disease. Atherosclerosis of the renal vessels may promote atrophy of the kidney, and renal tissue growth decreases (Miller 2008). The total capacity of the bladder declines and tissues may atrophy, causing both functional and structural incontinence. The renal tubules become less efficient in exchanging substances, and balancing water and sodium. There is increased risk of hypertension, proteinuria, glucosuria and nocturia (Lueckenotte 2006).

Reproductive system

Changes in structure and function are the result of hormone alterations. In men, there is no definite cessation of fertility, but refractory periods may increase. Prostatic hypertrophy can cause incontinence, frequency and nocturia in men. Female breasts become smaller, sag and become more pendulous due to loss of breast tissue mass, loss of elasticity and tone. Lubricating vaginal secretions are reduced (Berman et al 2012). Reduced libido is not usually related to hormonal changes, but decreased sexual activity may be the result of illness, death of sexual partner or decreased socialisation (Elias & Ryan 2011).

Immune system

T-cell activity declines and T-cells take longer to replenish in older people. More immature T-cells are present in the thymus and are less able to proliferate in response to pathogens; therefore, the immune response to invading antigens is slowed. The immune system is not ineffective; it is just slower, and less responsive to invasion. Responses to vaccines (influenza, tetanus) are decreased (Berman et al 2012). Inflammatory response declines, therefore in the presence of inflammation or infection, clinical manifestations such as fever and pain may not be present. Immune system changes may precipitate insulin resistance (Berman et al 2012).

Endocrine system

The thyroid gland fibroses and becomes more nodular. Despite changes, thyroid activity remains adequate in the absence of disease. Parathyroid activity remains within normal limits. The adrenal cortex, regulated by the pituitary gland, decreases production of adrenocorticotropic hormone, and there is also a noted decrease in the production of oestrogen, testosterone and androgens (Crisp & Taylor 2009). There is delayed and insufficient release of insulin by the beta cells, and a decreased sensitivity in tissues to insulin. The ability to metabolise glucose is reduced, causing increased blood glucose concentrations.

Psychosocial changes

Much of the psychological context of the theories of ageing are based on the premise that social exchanges and interactions are reduced over time and that, as a person ages, they become more selective about whom they choose to spend their time with.

Emotional closeness may become more important with significant others (although this is not suggestive of family-only interactions, but of relationships that are significantly meaningful and productive to the older adult). Psychological theories of ageing support the belief that the older adult will choose whom they want to dedicate their time to, because time becomes more important as one ages (quality verses quantity).

For the oldest old stage of ageing (see Clinical Interest Box 13.1), time equals energy, and being selective about whom they expend energy with ensures that the expenditure of energy results in pleasure, social interaction, belonging and meaning (Farley et al 2006). As a person ages, the ability to expend energy on social, emotional and psychological needs becomes less than the energy used to meet physical needs, therefore the older person may pursue fewer social and emotional interactions (Miller 2008). This does not mean, however, that their social, emotional and spiritual needs become less; it is simply that their ability to expend energy on meeting them becomes less available.

Personality development continues even in late adulthood. Late adulthood is the developmental stage during which people clarify and use what they have learned over the years. Older adults can continue to grow and adapt when they are flexible and realistic. Older adults can use their skills to conserve their strength, adjust to change and loss and use these years productively. For some older people there is a new awareness of time and older persons may want to use the time they have left to leave a legacy to their children or to the world, pass on the fruits of their experiences and validate their lives as having been meaningful (Wadensten 2006).

Older adulthood and the experience of grief

The experience of grief is not limited to the losses experienced when someone close to us dies. For an older adult, there can be many losses that will be grieved:

• Retirement from the paid workforce

• Change of living arrangements

• Change in physical health and wellness

• Loss of body parts (or function of)

• Changes to abilities (such as being independent in ADLs)

• Loss of sensory acuity (failing sight, hearing)

• Loss of mobility (e.g. driving a car)

• Regret at recognition of stage of life (i.e. later adulthood)

• Lack of fulfilment or achievements in life

• Lack of longevity expected in rest of life (own mortality) (Jeffreys 2010).

It is anticipated that those in older adulthood will encounter loss through death of siblings, parents, partners and friends. Some older people become more accepting of death as they age, whereas others grieve for the loss of longevity in their lives in the process of adapting to the ageing process. (See Clinical Interest Box 13.7 for strategies to assist an older person who is grieving.)

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.7 Strategies for nurses to assist older people to grieve

Nurses should be aware of their own attitudes towards dying, death, grief and loss. Death is a taboo topic in many cultures and many people do not think about it or discuss it with others

Many people are very uncomfortable talking about loss or listening to someone else talk about it. Grieving people often feel alone in their experience and do not want to burden others with discussion of their feelings. Giving a grieving person an opportunity to share personal feelings can be a very powerful experience

Encourage the expression of feelings, needs and beliefs and listen closely to what is being expressed. Whether an individual is experiencing denial, anger, confusion, fear or guilt, the nurse should remain calm, even when the emotions of the grieving person are intense

Do not take anger or irrational outbursts personally. Remember that the individual is grieving. Reacting to anger with anger will only escalate the situation

Because each person experiences grief very differently, nurses should not tell a grieving person that they know what they are feeling or understand what they are going through. What should be communicated is that they are sorry for their loss and offer sympathy and support

Do not try to talk individuals out of their feelings. People experience intense emotions following a loss and need a safe place to express them. Use active listening skills, like responding to statements without agreeing, challenging or disputing the other person’s perspective. Listen carefully and acknowledge what the person has said

Allow an individual time to think about the loss. This is especially true for older adults who may be processing information more slowly

If grief is interfering with daily functioning for more than two months after the loss, referral to a grief counsellor may be beneficial

(Adapted from Christensen & Kockrow 2011, Lueckenotte 2006)

Cognitive changes

Cognitive changes that impact on everyday life are not a part of normal ageing (Berman et al 2012). Such changes should be considered abnormal. The risk of dementia does increase with age (Clinical Interest Box 13.8). Dementia is the term used to describe the symptoms of a large group of illnesses that cause a progressive decline in a person’s cognition, to a degree that it interferes with intellectual, social and occupational function.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.8 Dementia

The incidence of dementia in Australia is projected to rise from the current figure of 257 275 in 2010 to 1 130 700 by 2050 (Access Economics 2009). Its prevalence in older adulthood increases with age:

Socioeconomic changes

The majority of older adults from Australia and New Zealand continue to make valuable contributions to their families and their community. A substantial proportion of volunteering, both in the community and in the care of younger and older family members, is undertaken by people aged 55 years and over (ABS 2011; Thornton 2010). Formal, paid employment may decrease for many older adults in the population, but immeasurable economic, cultural and social contributions are made to the community through informal care and participation by older adults often for other older adults, and those who are disadvantaged or have disabilities that impact on their ability to function independently (AIHW 2007). The contribution of older adults is often not measurable until it is discontinued as a result of illness or a change in circumstance. The value of volunteering and informal care arrangements impacts on the recipient, but also on the older adult, who is active, engaged and continues to find worth and identifiable roles in the later stages of their life (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Sexuality and the older adult

Sexuality is a part of self, regardless of age or disability. As a person ages, the ways in which their sexuality is expressed, and the way they see themselves as sexual beings, may change. The expression of sexuality and self extends from basic human needs such as the ability to give and receive tactile stimulation (touching, stroking and massage), to the way we present ourselves to the world. If it was important for a woman to always wear a skirt with stockings as a part of who and how she saw and expressed herself, then her choices and expression should be continued for as long as is practicable to ensure that the maintenance of personhood (self) is preserved. Sexuality is not only about sexual intercourse or sexual activity, although both may be part of how a person, older or younger, expresses themself.

HEALTH RISKS/PROBLEMS

Australians’ life expectancy at birth continues to rise and is among the highest in the world. For older people, the main causes of death are heart disease, stroke and cancer. At age 65, Australian males can now expect to live a further 19 years to almost 84 years of age, and females a further 22 years to almost 87. The figures for 2007–2009 in New Zealand project males having a life expectancy of 78.4 years and females 82.4 years (The Social Report 2010). Life expectancy, however, is not uniform across all groups of society in Australia and New Zealand. Compared with those who have social and economic advantages, disadvantaged Indigenous populations in both countries are more likely to have shorter lives. Indigenous people are recognised as being generally less healthy compared to other cohorts in the community, die at much younger ages and have more disability and a lower quality of life. People living in rural and remote areas tend to have higher levels of disease risk factors and illness than those in major cities (AIHW 2010c). Older Māori adults in New Zealand have a reduced life expectancy as compared to non-Māori older adults of 8.6 years for females and 7.9 years for males (Ministry for Social Development 2010).

In taking into account age-related changes, the most common specific health problems of later adulthood are usually related to degenerative changes in body systems. Most older people with degenerative changes will experience at least one loss of function in a body system; therefore, comorbidities increase the complexity of disease processes, treatment and the nursing care that is required.

Chronic conditions

Although the majority of older people are in good health, chronic medical conditions do become more frequent with age and may cause disability. Older people have at least one chronic condition: the most common conditions are arthritis (48%), complete or partial deafness (33%), cardiovascular disease (24%), osteoporosis (16%) and type 2 diabetes (13%) (ABS 2010b). Another common problem of late adulthood is dental problems, especially tooth decay. This affects digestion and leads to many other problems. Older people may suffer from a wide variety of functional disorders related to ageing and chronic diseases.

People over 65 years generally have fewer colds, influenza and acute digestive problems than younger adults. The danger with older people is that a minor illness—combined with chronic conditions and loss of reserve capacity—may have serious repercussions (Victorian Government Health Information 2010). Susceptibility to illness is one of the most serious problems confronting older persons.

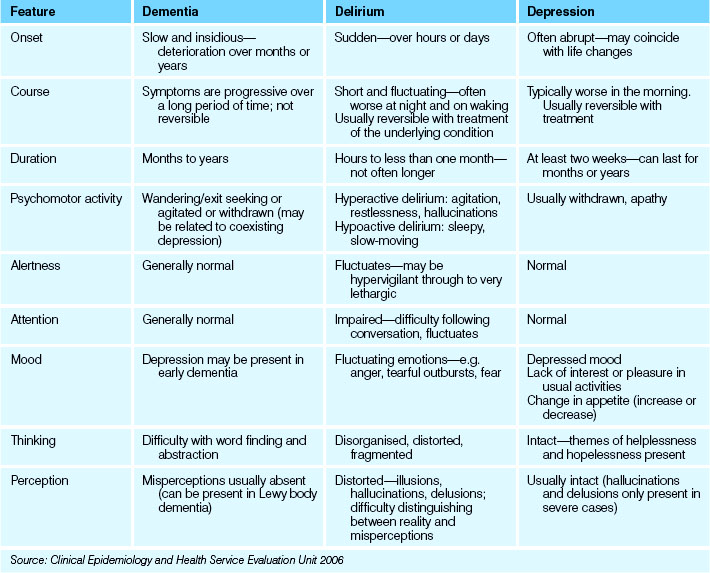

Impaired cognition

The three most common conditions affecting cognition in the older adult are dementia, delirium and depression. The nurse should be able to distinguish between the three in order to select appropriate nursing interventions (Crisp & Taylor 2009). It can sometimes be difficult to distinguish between manifestations of altered cognition and functional ability in older clients.

Dementia

Dementia is a disease process, progressive in nature. It is not a normal part of ageing, but the incidence and prevalence of this condition increases proportionately with chronological ageing. Dementia interferes with cognitive functioning to the degree that it impacts on normal social and occupational activity. The areas of function that may be affected in a person living with dementia are:

• Ability to plan and make decisions

• Ability to reason or learn new ideas

• Control mechanisms including emotions

• Orientation and spatial awareness (Alzheimer’s Australia 2010).

A person living with dementia will not necessarily have disturbance to all intellectual function, but will experience difficulties with abstract thinking and decision making (Christensen & Kockrow 2011).

Risk factors for dementia include hypertension, high cholesterol levels, poor diet, obesity, age (65+), smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, heredity (5–10%) and head injury.

There are more than 160 different types of dementia, with the highest incidence being:

Alzheimer’s disease: the most common form of dementia accounting for between 50% and 70% of all dementias. Alzheimer’s disease is a physical disease which attacks the brain, resulting in impaired memory, thinking and behaviour. As brain cells die, the substance of the brain shrinks. Abnormal material builds up as ‘tangles’ in the centre of the brain cells and ‘plaques’ outside the brain cells, disrupting messages within the brain and damaging connections between brain cells. This leads to the eventual death of the brain cells and prevents the recall of information (Alzheimer’s Australia 2011).

Vascular dementia: the broad term for dementia associated with problems of circulation of blood to the brain. There are a number of different types of vascular dementia, the most common being multi-infarct dementia. Multi-infarct dementia is caused by a number of small strokes called transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs). The strokes cause damage to the cortex of the brain, the area associated with learning, memory and language (Alzheimer’s Australia 2011).

Dementia with Lewy bodies: this is caused by the degeneration and death of nerve cells in the brain. The name comes from the presence of abnormal spherical structures, called Lewy bodies, which develop inside nerve cells. It is thought that these may contribute to the death of the brain cells. People living with dementia with Lewy bodies may experience difficulty with concentration and attention, extreme confusion, difficulties judging distances (often resulting in falls), visual hallucinations, parkinsonism and fluctuations in mental state from lucidity to extreme confusion (Alzheimer’s Australia 2011).

Fronto-temporal lobar degeneration: the name given to dementia when there is degeneration in one or both of the frontal or temporal lobes of the brain. There is considerable difference in symptoms, depending on which parts of the frontal and temporal lobes are affected. The right and left frontal lobes govern mood, behaviour, judgment and self-control. Damage leads to alterations in personality and behaviour, changes in the way a person feels and expresses emotion and loss of judgment. The right and left temporal lobes are involved in the organisation of sensory input such as what you hear or see. Damage may lead to difficulty placing words or pictures into categories (Alzheimer’s Australia 2011).

Parkinson’s disease: dementia with Lewy bodies sometimes co-occurs with Alzheimer’s disease and/or vascular dementia. It may also be hard to distinguish dementia with Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease, which is also associated with Lewy bodies, and some people who have Parkinson’s disease develop a similar dementia (Alzheimer’s Australia 2011).

Clinical Interest Box 13.9 discusses the issue of sexuality and dementia.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.9 Sexuality and dementia

If behaviour is sexually motivated and inappropriate, for example, if it is being conducted publicly, the matter may be resolved and the person’s dignity maintained by gently discouraging the behaviour or by redirecting the person with dementia to another activity. Some people who are living with dementia may behave in a sexually inappropriate manner that is totally different to behaviour before the onset of their dementia. The underlying cause is the invisible damage to the brain caused by the illness. It can be helpful to remember that the person with dementia does not intentionally seek to embarrass or annoy others (Alzheimer’s Australia 2010). Nurses need to recognise that the desires and needs of older people are not unlike their own. There is no reason to prevent older people, even those who are very old, from forming relationships. This may mean that they simply wish to spend time together, hold hands, hug or kiss. Or it may mean that a couple wish to sit, lie down together or become more intimate. This can be reassuring and comforting for both but can also cause problems in different ways.

Specific problems may arise if:

• One or both has a wife or husband but are no longer aware of their marital status because of memory impairment in dementia

• One or the other is at risk of harm or injury as a result of the relationship

• The new relationship distresses a spouse or other family members

• One client is exerting power over the other, or in any way coercing the other

• Staff are in conflict about the ‘rights and wrongs’ of the situation and cannot agree on how it should be managed

In such cases it is advisable for the healthcare facility to have a clearly formulated policy concerning residents and sexual behaviour. This should guide responses and can be shown to family members in case of conflict about what should happen. A policy may indicate that if there is no evidence of overt sexual activity the rights of the residents to have a relationship will be respected; alternatively, the policy may indicate that such relationships will be discouraged by close monitoring or by moving one client to another facility.

Ideally, relatives should be alerted to how the pathophysiology of dementia can lead to the possibility of such relationships developing and be made aware of relevant policies before the loved one is admitted to the facility.

Delirium

Delirium is an acute, transient confusional state that often has a reversible physiological cause. It is characterised by impaired cognitive function, and reduced ability to focus, sustain or shift attention (Clinical Epidemiology and Health Service Evaluation Unit 2006). The disturbance manifests in a very short time, and fluctuates throughout the day. It may last only a few days, or may persist for weeks, depending on the ability to identify and manage the cause of the confusion. Delirium in older people is often overlooked or misdiagnosed. Delirium is usually precipitated by an underlying acute health condition, which in most cases can be identified with careful assessment and investigation. Increasing old age, dementia, visual impairment and severe medical illness are important risk factors for delirium. It is estimated that 10–15% of older adults admitted to acute health facilities will experience delirium during their admission and about 40% of older adults in residential aged care facilities may be found to be in delirium state (in any 2-week period) (Clinical Epidemiology and Health Service Evaluation Unit 2006). Nurses should place importance on environmental and physiological changes that may impact on the psychosocial presentation of older adults.

Depression

Depression is not a normal part of ageing. It is under-recognised and inadequately treated in many older people. Misdiagnosis of depression delays treatment, increases the risk of functional decline and slows the rate of recovery. Depression in older adulthood is a serious condition, and can be associated with a loss of independent function, cognitive impairment, poor response to rehabilitation and diminished recovery. It also can lead to an increased risk of death. Major depression occurs in 1–3% per cent of the general older population, with a further 8–16% having clinically-significant depressive symptoms. The incidence of depression in long-term care settings is three to four times higher than in the general population (Victorian Government Health Information 2010). Sleep disturbances can result in cognitive impairment and depression. Depression can be effectively treated in older people resulting in improved mood, improved function and an increased quality of life.

With the projection of the numbers of people who will be living with dementia in the twenty-first century, and the assumption that we will live longer in adulthood, nurses must have the knowledge and skills to communicate effectively and provide appropriate care that celebrates the person who is living with a dementing illness. See Table 13.1 for a comparison of dementia, delirium and depression.

Falls

The World Health Organization defines a fall as ‘an event which results in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground or floor or other lower level’. An injurious fall is a fall that causes a fracture to the limbs, hip or shoulders (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2009). It is recognised that older adults are more at risk of falls related to both physiological (e.g. osteoporosis, decreased exercise, vision impairment) and environmental factors. See Clinical Interest Box 13.10 for general safety measures to prevent falls. These safety measures can be utilised for all hospitalised clients.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.10

General safety measures to prevent falls include:

• Ensuring that floors are free of clutter, slippery substances and loose rugs. Spills should be wiped up immediately, floor coverings should be maintained in good repair and rugs should have a non-slip backing or be removed from the area. Large, clearly worded warning signs should be displayed when floors are wet or slippery

• Installing handrails in corridors, stairways, bathrooms and toilets. These provide support for individuals who are weak or unsteady when walking and also provide support when a client is sitting down or getting up; for example, sitting on the toilet or getting out of the bath

• Placing a non-slip mat on the floor at the base of the bath or just outside the shower cubicle. A chair should be available in the bathroom for clients to sit on; for example, during a shower or while dressing or undressing. Floor tiles in any area should be of the non-slip variety

• The nurse remaining with and supporting at-risk clients during hygiene and toileting procedures and whenever there is a risk of the client falling

• The nurse frequently checking more independent clients during hygiene and toileting procedures and ensuring that every client is aware of the position of the call button in the shower or toilet area

• Adjusting the height of the bed to meet the needs of individual clients, enabling them to get into and out of the bed safely and independently whenever possible

• Placing any items that the client might need within easy reach; for example, when the client is in bed or sitting on a chair. Items required should be on the locker or over-bed table that is positioned close to the client. This avoids the risk of a fall from the bed caused by the client stretching while attempting to reach for a needed item

• Ensuring that all walking aids, for example, crutches and frames, are fitted with non-slip tips to prevent them skidding on the floor. Clients who are using walking aids should be supported adequately and supervised until they are able to use the aids safely. All walking aids should be positioned at the correct height for the individual client

• Ensuring that clear lighting is available in all areas and that a nightlight is provided in the client’s room

• Placing the signal device within the client’s easy reach so that assistance can be summoned if necessary; for example, to get out of bed

• Keeping all areas free of items that could cause a person to fall; for example, electrical cords, cleaning equipment, linen, dressing or medication trolleys

• Ensuring that ambulant clients wear shoes or slippers that are well fitting and have non-slip soles. The cord from a dressing gown should not be allowed to trail, as it could cause the person to trip

• Doors should remain fully open or closed, as people are more likely to bump into a door that is ajar

In some circumstances even the most careful nursing interventions are unable to avoid the risk of injury or harm to clients. In such cases, as a last resort, it becomes necessary to consider the use of restraining devices to protect clients.

Restraints

Restraints, sometimes called protective devices, are used to limit the freedom of movement of a client of any age, to varying degrees. Restraints may be physical or chemical. Protective or restraining devices are used to prevent clients from harm or from harming others.

The Department of Health & Ageing (2004) has produced guidelines for the use of restraints in all health and aged care settings. These guidelines state that:

• All orders for restraint must be renewed daily

• A medical officer’s order for restraint must state the reason for the restraint, the time period and the type of restraint to be used

• Restraints should only be used after all other possible ways of ensuring safety have been tried and documented as unsuccessful

• Restraints cannot be used for staff convenience

• There must be documentation that the need for the restraint was made clear to the client and family.

Protective devices include the use of:

• Side rails on a client’s bed

• Security or safety belt on trolleys or wheelchairs

• Soft material ties (extremity immobilisers) that prevent movement of the hands and feet

• Padded coverings for the hands; for example, hand mitts

• Vest or jacket chest restraint that secures a client in an upright position in a wheelchair.

Selecting a restraint

When selecting a restraint the nurse must consider the following:

• It is the least restrictive possible

• It does not interfere with treatment

Some suggestions for alternatives to the use of a restraint are identified in Clinical Interest Box 13.11.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.11 Suggestions to promote restraint minimisation

• Electronic movement sensors (see Fig 13.2)

• Planned night-time activities for those who wander at night

• Daytime recreational and social activities, provide auditory and visual stimuli such as soothing music, television or radio

• Activity areas at the end of each corridor

• Easy access to safe outdoor areas

• Structural design of units modified to enhance visibility of residents. Assign confused or disoriented clients to rooms with high visibility

• Outlets for industrious or anxious behaviour; for example, physical, occupational and recreational therapies

• Review medication to ensure they are having the desired therapeutic effect

(Adapted from Department of Health and Ageing 2004, Joanna Briggs Institute 2002)

Mistreatment of the older adult

Mistreatment or abuse may be directed towards an older person or carer and may involve physical, psychological, financial or sexual neglect (O’Keeffe et al 2007; Berman et al 2012).

Physical neglect/mistreatment may involve failure to provide food, fluid, personal care and hygiene. Overmedication may be used to cause sedation. Hitting, slapping and pushing may also occur.

Psychological mistreatment may involve name calling, swearing, threats, humiliation or bullying. Abuse may also include isolation or confinement. Misappropriation of money or valuables or denying the right to money may also occur (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

The older adult may be mistreated in their own home, an aged care facility or hospital. Abusers may be family members/carers, other relatives and in some cases healthcare providers. Older adults are usually afraid to report abuse or neglect because they are ashamed or fear retaliation. Nurses should be familiar with the laws under which they work in regard to the reporting of suspected or known cases of neglect (Berman et al 2012).

CULTURAL ASPECTS OF AGEING

Cultural aspects of ageing are often grouped with characteristics of ethnicity and linguistic diversity. In Australia the population of older people from culturally and linguistically diverse populations is increasing (Crisp & Taylor 2009). A culturally diverse background to the environment in which the older adult is ageing can create challenges for the older person, their family and friends, and to the nurses who provide their care. Isolation and feelings of alienation created by a lack of cultural interaction can be compounded by difficulties with communication and acceptance of care strategies. In Australia and New Zealand, the introduction of culturally specific residential care services is attempting to address this challenge; however, unless these services are accessible for the older adults requiring them, many culturally diverse older adults will be accommodated within mainstream care services.

For many family members of these culturally diverse older people guilt at not being able to provide care at home for their relative may increase the difficulties experienced by the older adult and the care staff.

Strategies that nurses can implement to assist with care of older adults with culturally diverse backgrounds include:

• Appreciating that all people have diversity in their backgrounds

• Considering own beliefs, attitudes and values

• Refraining from assumptions relating to the thoughts and feelings of the older adults and their families in regard to difficulties experienced. Listening and communication are paramount

• Appreciating the diversity that exists within cultures, language and values (different dialects, religions, practices within an ethnicity)

• Clarifying with the older adult and their family the importance of cultural behaviours and events

• Seeking education and familiarising self and workplace with the specific needs of people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

See also Clinical Interest Box 13.12.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.12 Attitudes to ageing

To which of these statements of negative and positive views of ageing do you agree?

Negative

• People have a poor view of turning 60 or 70 and fear getting older

• The older you get the worse your health will become

• Older people will end up in an old age home. Families will put them in a home when they become a burden

• Older people will experience age discrimination (employment, healthcare, etc)

• Women aren’t as beautiful as they age

• Older people become more cranky and have wrinkled skin and grey hair

• Many older people are sick, disabled, demented

• Older people have no sexual desire or the thought of them having sex is repulsive

• Older people are a drain on the healthcare system

• Old workers are not as effective as younger workers

• Older people live in poverty or cannot afford their medications

Positive

• People look forward to the ‘golden years’

• Society has different standards that older people are held to in comparison to younger people

• Older people have more free time to spend with friends and family

• Older people have the freedom to do the things that they couldn’t do before

• Older people are nice, warm, friendly people

• Older people have lots of knowledge and wisdom and have the time to help others

• Older people are well off financially and don’t have career and childcare issues to worry about

HEALTH ASSESSMENT AND PROMOTION

Assessments and health screening that are undertaken in wellness will assist in identifying adjustments or treatments that are required to manage age-related changes to ensure that function and quality of life are maintained. With an accumulation of age-related changes, disease processes may begin to impact on the person’s quality of life and functional ability. This impact may be identified through assessments by healthcare professionals. Hospitalisation often provides the opportunity for assessment of the older adult (Eliopoulos 2010).

The Australian Government funds some programs through Medicare and other national health strategies. In New Zealand, membership of a Primary Health Organisation makes it possible to access similar services. These may include:

CARE SETTINGS

Continuum of care—assessment as the basis for care

With the ageing of the baby boomers in Australia and New Zealand (those born after the end of World War II and up to 1964), the number of people within the population who are moving towards the ‘young old’ category of older adulthood is increasing markedly. With this rise expected to continue over the next decade, changes in care provision will continue to be refined by successive governments. What is becoming clearer is that older adulthood is no longer accepted as a time of only frailty and chronic illness, but that older adults enjoy ‘good health and wellness’ as they age and actively pursue their own choice with regard to their finances, health and occupation. Their considerable influence (and power related to numbers) means that political parties are listening more carefully to the needs and wants of older adults. The time of assumptions of knowing what is best for older people has passed.

For nurses to assist older adults in planning effective care, a familiarity with current forms and access to services is necessary.

Community care

When older people are required to make adjustments in their lives to accommodate assistance with their functionality, community services may provide this assistance. This may be in response to assistance required after an illness, surgery, hospitalisation or as a result of an assessment prompted by a general practitioner (GP) or a relative to identify areas in the activities of daily living (ADLs) that the older person may not be able to manage independently.

Community care services may assist older people to live independently with informal care for extended or short periods of time. When the decision is made, either willingly or as a necessity for more formalised, continual care, an Aged Care Assessment Team (ACAT) in Australia or a Needs Assessment Service (NASC) in New Zealand assessment/reassessment will be required.

Aged Care/Needs Assessment Teams

A formal assessment is required for any government-funded care service (federal, state or local government funded). The multidisciplinary ACAT or NASC team operates as a single point of entry to community and residential aged care services and as a point of referral to other services. A referral for ACAT/NASC assessment may be by self-referral or it may come via family or friends, healthcare practitioners or community services known to the person. Assessment of a person’s care needs takes into account physical, medical, psychological and social factors and facilitates access to appropriate care services (AIHW 2007; Ministry of Health 2010).

In Australia, care needs will be determined, and an assessment will be made regarding the requirement for ‘high’ or ‘low’ care needs (as determined by the Aged Care Funding Instrument (ACFI)). High level care indicates that the older adult requires frequent care interventions of a complex nature, and this care can be delivered in the community, or in a residential aged care facility (RACF). Low level care indicates that the degree and frequency of care is less, and care can also be delivered in the community or in an RACF.

In New Zealand, a NACS assessment will determine the Support Needs Allocation Band that is applicable. For high to very high support needs allocations, residential care will be accessible. It will then be necessary to apply for a Residential Care Subsidy (Ministry of Health 2010).

Community aged care packages

Community aged care packages allow older adults to receive the care they require without relocating; that is, they are able to remain in their own homes and communities. The services provided vary according to the needs of the individual, as assessed by ACAT/NASC.

Community care services may include meals, cleaning, transport, home and garden maintenance, and assistance with personal care. For older adults with greater needs, home nursing (district nursing), counselling and therapy may also be provided. There are three main types of community aged care packages in Australia—Community Aged Care Packages (CACP), Extended Aged Care at Home (EACH) and Extended Aged Care at Home Dementia (EACH D).

CACPs target those with low-care needs, while EACH packages are designed for those older Australians whose needs are determined to be high-care. EACH D package is specifically tailored to provide care for high-care clients with dementia-related care needs.

In 2009, there were over 44 000 older adults using community aged care packages in Australia, with most requiring a relatively low level of care. In New Zealand, Home-Based Support Services (HBSS) comprise household management (help with domestic tasks around the home) and personal care services (assistance with bathing or dressing), along with key services that provide support for informal carers (including respite care), environmental support services (equipment and mobility aids), day activities and rehabilitation. The aim is to provide options and alternatives for older adults who require assistance to continue to live in their own homes. (See Clinical Scenario Box 13.1.)

Clinical Scenario Box 13.1

Alan Porter is 75 years old and has lived alone for the past 10 years. He enjoys living in his neighbourhood and plays cards every Thursday night with some friends up the road. He also lives a suburb away from his niece and goes to church with her and her family on Sundays. His pride and joy is his modest-sized garden, in which he has a variety of fruit trees and a vegetable patch.

Recently, Alan has had trouble with his vision and, as a result, has decided to give up driving. He has also noticed that while he still loves his garden, the work needed to maintain it seems to take twice as much effort. Alan’s niece has noticed that the state of his appearance has been deteriorating as his clothes are often dirty. She also recently visited him at home and found that, while Alan spent a lot of time working on his garden, his house was quite dirty and his cupboards were pretty bare except for some tins of soup and baked beans. Alan feels very connected to his community and wants to stay there, but he has realised that in order to do this, he may need help. He is trying to decide what options might be available to him.

Acute settings

On occasions, assessment, treatment and rehabilitation of a new or existing chronic illness or a surgical or medical intervention may require admission to an acute care setting. Older people are typically more at risk in this setting than those in younger age groups. Nurses will benefit from an awareness of age-related changes to older adults and how risk is increased for this cohort. See Clinical Interest Box 13.13 for a list of risk factors for hospitalised older people.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.13 Risk factors for hospitalised older people

• Effects of immobility (loss of strength, constipation, stasis)

• Adverse reaction to anaesthetics

• Adverse reaction to medications

• Increased risk of nosocomial infection

• Loss of independence, autonomy

• Response to unfamiliar environment

• Slower recovery rate due to reduced energy reserve and response

• Slower adaptation and coping mechanisms (physical/emotional)

Discharge planning for older adults in acute settings is imperative to ensure that the older person has the required support for ADLs, as well as service provision for nursing and home care to optimise the highest level of function and independence possible. Refer to the resources in the References and Recommended Reading section at the end of this chapter.

Rehabilitation

To assist an older person to reach and maintain their optimum level of function, a phase or period of rehabilitation may be necessary. The site for rehabilitation may be in the acute care setting, as an outpatient in the community, in a specific rehabilitation unit or in the residential care setting. Nurses are an important part of the multidisciplinary rehabilitation team, often taking a role in assisting the older person in their ADLs and facilitating adjustment to their independence and ability (Berman et al 2012). See Chapter 38 for more information on rehabilitation nursing.

Residential aged care facilities

When older adults can no longer remain in their own homes, they may decide, or a decision may be made for them, to move into residential aged care facilities where their care needs can be more holistically met. Aged care facilities provide suitable accommodation, as well as services such as meals, laundry and cleaning, personal care, medication assistance, complex nursing care, as assessed by nursing staff once the older adult has taken up residence.

In Australia in 2009, there were 162 000 people (usually referred to as ‘residents’) in mainstream residential aged care services. In New Zealand in 2008, there were 32 400 people in residential care settings, typically referred to as ‘rest homes’, the largest cohort being over the age of 85 years (Thornton 2010). In Australia, females made up the majority of the residents—more than double the number of males (about 114 600 females and 47 700 males). The highest proportion of residents in residential aged care was aged 85–89 years, making up 28% of residents. The lowest proportion was aged 65–69 years, which accounted for just 3% (AIHW 2010b).

The admission to an RACF has the potential to affect an older person in physical, psychological and emotional ways. Nurses must be aware of this period and the ability of the older person to adjust to this major change in their circumstances and way that they live. Issues of privacy, dignity, self-esteem and maintenance of personhood are all factors that require the older person to undertake a period of adjustment and adaptation. Some older adults find the move to residential care comforting, while others feel isolated and alienated.

Quality of care in residential aged care

The monitoring of the standards of care is managed by a process called Aged Care Accreditation in Australia and Certification in New Zealand. This process follows a similar procedure in both countries, and ensures care facilities provide a high quality of care. Organisations must:

• Be committed to protecting their residents’ rights

• Ensure that they have appropriately qualified staff with the right mix of skills to meet residents’ needs.

The standards cover all aspects of residents’ needs from health and personal care and safety to a range of lifestyle matters including independence, privacy and dignity. Care facilities (service providers) that meet these standards are accredited/certified. Service providers that do not meet these standards may be subject to sanctions. A comprehensive guide to the most current aged care standards and accreditation information can be found at the end of the chapter.

NURSING CARE OF THE AGEING PERSON

Older Australians and New Zealanders face challenges and adjustments as they move into later adulthood. (See Clinical Interest Box 13.14.) They contend with the end of employment, at whatever age they retire, changes in health status, changes in relationships with family, children and friends and adjustments to losses. Nurses must listen to older clients, rather than making assumptions about what they value and aim for in their lives.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.14 Adjustments and adaptations to ageing required of older people

• Retirement/end of paid employment

• Health status/changes to capacity

(Adapted from AIHW 2007, Crisp & Taylor 2009)

As age-related changes and chronic illnesses affect the functioning of older adults, the assistance that they require becomes more complex. This is not to say that all older people will require full assistance with all of their care needs. It is frequently shown that with assistance to meet needs in certain areas (such as mobility or positioning), other ADLs such as nutrition or toileting can be better maintained by the older person themselves. This type of care is called person-centred care—care that is specific and individualised to that unique person.

IMPLEMENTING THE NURSING PROCESS

Nurses must recognise that holistic care needs do not disappear or become inappropriate due to changes in health circumstances. No matter what the illness, injury or disability, care delivery needs to be assessed in conjunction with the client’s previous attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, experiences and behaviours relating to their expression of self. Assessment and care planning need to incorporate physical, psychological, social and cultural elements. (See Chapter 15 for discussion of these components of the nursing process.)

Specific nursing assessments for older adults

Nutrition: Mini Nutritional Assessments (MNAs) have been developed to allow for a holistic assessment of factors that may impact on nutritional status. See Clinical Interest Box 13.15 for these factors in older adulthood.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.15 Non-physiological causes of undernutrition in older people

Psychological factors

Medical factors (mediated through anorexia, early satiation, malabsorption, increased metabolism and impaired functional status)

(Adapted from Visvanathan et al 2004)

Falls: falls are the most common cause of injury for older adults in an acute care facility (deWit 2009) but every client in every care setting should be assessed for the risk of having a fall. Falls risk is a recognised priority in Australian healthcare. There are many different falls risk assessment tools (see Table 13.2).

Table 13.2 Falls risk-assessment tool

| Place a tick in front of the items that apply to the patient. |

| General information |

| Medications

|

| Gait and balance |

* Note: A tick on any starred item indicates a risk for falls. A combination of four or more of the unstarred items indicates a risk for falls.

Source: deWit 2009

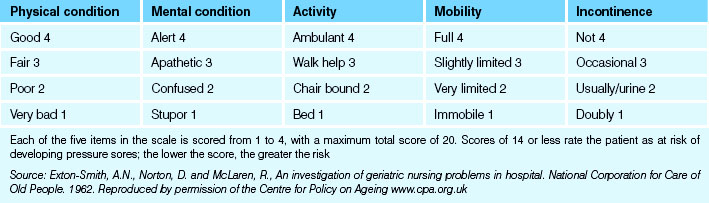

Skin assessment: relative to the level of dependence and disability in an older adult, the risk of interruptions to skin integrity and the development of pressure ulcers is a risk factor that must be managed. Refer to Table 13.3 for an example of the Norton Scale which is used to assess risk of pressure ulcers.

Continence: although incontinence can affect all age groups, assessment of urinary and faecal continence is an important component of the assessment process for the older adult.

MMSE: the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS) provide quick measures of cognitive impairment. These tests are useful to assess and document severity of cognitive impairment and to measure changes in cognitive function. Alzheimer’s Association Australia provides further explanations of the implications of these tests (see Clinical Interest Box 13.16 and References and Recommended Reading).

Care planning

The nurse and client together (or the older person’s representative) develop a care plan that responds to individual needs. Where appropriate, the client’s partner or close relative may be included in the planning. This is particularly relevant when the older person’s partner, family or significant other has been involved in the primary care of the person. The information that the older person and their primary carer can provide will ensure, where appropriate, that this care and preference can be continued, further supporting the value of person-centred care planning and delivery. Honest communication about concerns, wants and needs will assist the older adult to feel positive about their ability to maintain some degree of decision making and independence, even when faced with serious impairment (AIHW 2007). See Clinical Interest Box 13.17 for strategies to help the older adult face the challenges of ageing.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 13.17 Helping older people face the challenge of ageing

Help older adults maintain roles and relationships

Offer maximum support to facilitate older people to do or be involved in personal decision making

Discover and celebrate the uniqueness of older adults’ interest, skills and knowledge. Encourage discussion on past accomplishments and experiences to support the maintenance of personhood

Listen to the concerns of your client, regardless of their age or ability

Reminisce with older adults—their experiences can be valuable in promoting and maintaining relationships and self-esteem

(Adapted from Crisp & Taylor 2009, Eliopoulos 2010)

The nurse with excellent interpersonal skills such as listening, asking open-ended questions, using silence and summarising the discussion will help clients to share feelings, concerns and information about themselves (Stein-Parbury 2009). See Chapter 6 for more information on communication.

Nurses involved in planning care also require the following:

Summary

The older adult may access healthcare services in a variety of settings. The nurse needs to have an understanding of the ageing process and the physiological and psychological aspects of ageing. It is also important that nurses be aware of their own and others’ attitudes towards ageing. Nursing this cohort requires a thorough understanding of health teaching, promotion and person-centred care.

1. Mabel Grainger is a 70-year-old lady who has been admitted to hospital following a fall at home. She has a haematoma on her right arm and on her face but has not sustained any major injuries. What issues do you think may have led to her fall at home? What aspects of care will you consider in planning her discharge?

2. Joseph King is a resident in an RACF. He is not his usual self and when you inform him he has a visitor awaiting him in the lounge room he says he does not want to leave his room today. What might be your actions to address this change in Joseph?

3. Barry Whiteley has always been a keen bowls player but is becoming frustrated with his form and says he is not going to continue with his 3-times weekly sport. When you go to visit him with the district nursing service, he is dishevelled and noncommunicative. What might be your actions in addressing Barry’s situation?

References and Recommended Reading

Access Economics (2009) Keeping Dementia Front of Mind: Incidence and Prevalence 2009–2050

Aged and Community Services Australia. (nd) National Indigenous Aged Care Issue Paper. Online. Available: www.agedcare.org.au/what-we-do/cald/Indigenous_Issues_Paper.pdf.

Alzheimer’s Australia. Quality Dementia Care Series. Online. Available www.alzheimers.org.au/common/files/NAT/20101001_Nat_QDC_6DemSexuality.pdf, 2010.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2003) Population Projections, Australia 2002–2101. Cat. no. 3222.0. ABS, Canberra

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2010a). Population by Age and Sex, Australian States and Territories. Cat. No. 3201.0. ABS, Canberra

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2010b) National health survey: summary of results 2007–08 (reissue). Cat. No 4364.0. Canberra, ABS

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2011) Voluntary work, Australia, 2010. Cat. No. 4441.0. ABS, Canberra

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. Guidebook for Preventing Falls and Harm From Falls in Older People: Australian Community Care. Online. Available: www.health.gov.au/internet/safety/publishing.nsf/content/com-pubs_FallsGuidelines/$File/30454-RACF-Guidebook.PDF, 2009.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Older Australia at a Glance, 4th edn. Canberra: AIHW, 2007.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Aged Care Packages in the Community 2008–09: a Statistical Overview. Aged Care Statistics Series no. 30. Canberra: AIHW, 2010.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2010b) Residential Aged Care in Australia 2008–09. Aged Care Statistics Series No 31. AIHW, Canberra

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2010c) Australia’s Health 2010. Australia’s health no. 12. Cat. No AUS 122. AIHW, Canberra

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Pathways in Aged Care: Program Use after Assessment. Canberra: AIHW, 2011.

Berman A, Snyder S, Kozier B, et al. Kozier and Erb’s Fundamentals of Nursing, 2nd edn. French’s Forest, NSW: Pearson, 2012.

Christensen B, Kockrow E. Foundations of Nursing, 6th edn. St Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2011.

Clinical Epidemiology and Health Service Evaluation Unit. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Delirium in Older People. Canberra: Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC), 2006.

Crisp J, Taylor C. Potter and Perry’s Fundamentals of Nursing, 3rd edn., Sydney: Elsevier, 2009.

Curtis K. Never too old; sexuality and the elderly person. Australian Ageing Agenda. 2008;February:30–32.

Department of Health and Ageing. Decision Making Tool: Responding to Issues of Restraint in Aged Care. Online. Available: www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/ageing-decision-restraint.htm, 2004.

deWit S. Fundamental Concepts and Skills for Nursing, 3rd edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2009.

Elias J, Ryan A. A review and commentary on the factors that influence expressions of sexuality by older people in care homes. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2011;20(11–12):1668–1676.

Eliopoulos C. Gerontological Nursing, 7th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.

Farley A, McLafferty E, Hendry C. The physiological effects of ageing on activities of daily living. Nursing Standard. 2006;20(45):46–50.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198.

Jeffreys J. Understanding Grief in Older Adults. Living with Loss Magazine, Bereavement Publications Inc. Online. Available: http://griefcareprovider.com/images/understandinggrief.10.pdf, 2010.

Joanna Briggs Institute. Physical Restraint Part 2: Minimisation in Acute and Residential Care Facilities. In: Evidence Based Practice Information Sheets for Health Professionals. Best Practice. 2002;6(4):1–6.

Lueckenotte A. Gerontologic Nursing. St Louis: Elsevier, 2006.

McCance K, Huether S. Pathophysiology: The Biological Basis for Disease in Adults and Children, 5th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2006.

Miller C. Nursing for Wellness in Older Adults, 5th edn. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

Ministry of Health. Ageing New Zealand and Health and Disability Services 2001–2021: Background Information. International Responses to Ageing Populations. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2004.

Ministry of Health. Long-term Residential Care for Older People: What You Need to Know. Online. Available: www.health.govt.nz/publications/long-term-residential-care-older-people-what-you-need-know, 2010.

O’Keeffe M, Hills A, Doyle M, et al. UK Study of Abuse and Neglect of Older People. Prevalence Survey Report, London. London: National Centre for Social Research and King’s College of London, 2007.

Quadagno J. Aging and the Life Course: an Introduction to Social Gerontology, 5th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011.

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners ‘Silver Book’ National Taskforce. Medical Care of Older Persons in Residential Aged Care Facilities. Online. Available: www.racgp.org.au/silverbookonline/2-9.asp#2, 2005.

Stein-Parbury J. Patient and Person: Interpersonal Skills in Nursing, 4th edn. Sydney: Elsevier, 2009.

The Social Report. Life Expectancy. Online. Available: http://socialreport.msd.govt.nz/health/life-expectancy.html, 2010.

Thibodeau G, Patton K. Anatomy and Physiology, 6th edn. St Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2007.

Thornton G. Aged Residential Services Review. Online. Available: www.grantthornton.co.nz/Assets/documents/home/Aged-Residential-Care-Service-Review-Summary.pdf, 2010.

Victorian Government Health Information. Best Care for Older People Everywhere—The Toolkit. Minimising functional decline in older people in hospital. Online. Available: www.health.vic.gov.au/older/toolkit/01introduction/index.htm, 2010.

Visvanathan R, Newbury J, Chapman I. Malnutrition in older people—screening and management strategies. Australian Family Physician. 2004;33(10):799–806.

Wadensten B. An analysis of psychosocial theories of ageing and their practical gerontological nursing in Sweden. Scand J Caring Sci. 2006;20:347–354.

Aged Care Standards Agency (Australia), www.accreditation.org.au.

Agewell Health Promotion (New Zealand), www.agewell.org.nz/.

Alzheimer’s Australia, www.alzheimers.org.au http://www.alzheimers.org.au/victoria.aspx

Alzheimer’s New Zealand, www.alzheimers.org.nz.

Delirium, www.health.vic.gov.au/acute-agedcare/delirium-cpg.pdf

Department of Health and Ageing (Australia), www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/ageing.

Health, www.health.govt.nz/yourhealth-topics/health-care-services/services-older-people/residential-care/rest-home-certification-and-audits.

NASC needs assessment (New Zealand), www.health.govt.nz/publications/needs-assessment-and-support-services-older-people-what-you-need-know.

Nutrition assessment in older adults, www.fallssa.com.au/cms/documents/hp/Nutritional_Risk_in_Older_People-EPC_plan_flow_chart.pdf.

Older adults in hospital, www.health.vic.gov.au/older/toolkit/06Cognition/index.htm.

Sexuality and dementia, www.alzheimers.org.au/common/files/NAT/20101001_Nat_QDC_6DemSexuality.pdf.