CHAPTER 38 Rehabilitation nursing

At the completion of this chapter and with further reading, students should be able to:

• Recognise the terminology used in rehabilitation nursing to describe the client’s level of functioning

• Explain the philosophy of rehabilitation

• Outline the functions of each member of the rehabilitation team

• Describe the process of adjustment to disability

• Recognise a person-centred approach to nursing care of the client who requires rehabilitation

• Develop a plan of care for a person experiencing disability within the context of their environment

• Examine the effects of interactions between the client, carers/family, health professionals and community context in the rehabilitation process

• Demonstrate problem-solving skills appropriate to the discipline by identifying potential issues involved in assessment and nursing care for a client with a disability

Rehabilitation is a dynamic process which, to be effective, must occur as a collaborative process involving all members of the rehabilitation team, of which the client is the most important. Effective rehabilitation enables the individual to achieve optimal physical, emotional, psychological, social and vocational potential to maintain dignity and self-respect. Rehabilitation empowers the individual to make informed choices about healthcare and achieve a level of wellness that is acceptable to that individual. The rehabilitation nurse provides care, and employs education and supportive strategies based on rehabilitation philosophy, goals and concepts. Rehabilitation is a process of functional improvement that involves client, family, community and healthcare provider. Optimal function is achieved when the uniqueness and wholeness of the individual is recognised. The focus of this chapter is to introduce the nurse to the processes of rehabilitation and the many facets of rehabilitation that can be practised in any care setting.

I am just glad he is alive. I didn’t think when he first had his intracranial haemorrhage we were going to get this far. Do you know that he always used to bring me a cup of tea every morning before he went to work? Well, now it is my turn to look after him.

Sharon, wife to Glen, 48, who suffered an intracranial haemorrhage 5 months previously

Rehabilitation is a complex process with a range of dimensions including: motivation; adaptation to change; coping with stress; adjustment to altered circumstances, body capabilities and/or appearance; and regaining independence and wellness.

AIMS AND CHARACTERISTICS OF REHABILITATION

The basic aim of rehabilitation nursing is to limit the effects of disability and impairment in clients with particular conditions. It begins with immediate care to minimise the effects of damage and to prevent complications in the stage immediately after an accident or the onset of illness. It continues through the time clients are receiving restorative care and it often necessitates helping clients to adapt to a permanently changed situation and a new kind of life. Rehabilitation nursing includes a wide range of activities that include working collaboratively with other members of a rehabilitation team to:

• Retrain physically damaged clients to walk again

• Retrain cognitively damaged clients to communicate effectively orally or in writing

• Help clients adapt to impairment in a way that enables them to care for their own needs, such as showering, dressing and eating and using ordinary toilet facilities

• Promote client abilities to manage ordinary everyday modes of travel

• Teach clients how to put on, remove and care for different types of prosthetic appliances, e.g. an artificial limb or eye (Hoeman 2008; Jester 2007).

The rehabilitation process comprises the following stages:

• Goal setting: short, medium and long term

• Development of a plan to achieve goals

• Evaluation of progress (Jester 2007).

Rehabilitation also takes place in the area of mental health nursing and includes minimising impairment in function and preventing relapse in clients who experience recurrent problems with mental ill-health. Clinical Interest Box 38.1 indicates the main characteristics of rehabilitation.

Rehabilitation services can be delivered using a number of models of care including multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary teams, inpatient, outpatient, domiciliary and community-based rehabilitation services. All models include, to a varying extent, a team of people comprising the client, their family, allied health and nursing professionals and specialist rehabilitation doctors, working collaboratively to achieve the client’s goals.

Categories of individuals requiring rehabilitation

A person may experience a disability of acute or chronic onset at any stage of the life span. Those conditions requiring rehabilitation can be categorised as follows:

• Acute onset, e.g. cerebrovascular accident, head injury, myocardial infarction

• Gradual onset/relapsing course, e.g. multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis

• Acute onset/constant course, e.g. spinal cord injury

• Gradual onset/progressive course, e.g. heart failure (Derstine & Drayton-Hargrove 2001; Flannery 2004; Hoeman 2008; Jester 2007).

Rehabilitation services have four target groups:

• Clients who cannot go home from hospital without a return of, or improvement in, function

• Clients discharged after an acute admission requiring continuing care as an outpatient

• People living with congenital or acquired disability or progressive illness with the goal of preventing the need for hospitalisation

• People who are ageing and experiencing the functional losses associated with multiple chronic diseases (Royal Australian College of Physicians 2009).

Rehabilitation programs may be developed and implemented for an individual who is experiencing any of the conditions listed in Clinical Interest Box 38.2.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 38.2 Conditions frequently requiring rehabilitation

In many situations complete rehabilitation is achieved; but in others complete recovery of function is not possible and the individual faces a permanent disability or impairment (see Ch 39 for definitions of these terms). When this happens, individuals must be helped to accept, adapt to and compensate for the existing or progressive impairment to establish an optimal level of independence and quality of life. Clinical Interest Box 38.3 provides an explanation of the term adaptation.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 38.3 Explanation of adaptation

Adaptation implies the ability to adapt oneself or to modify behaviour and expectations in line with changing circumstances. Adaptation is a mechanism that affects the whole being—physically, socially and psychologically—and is a necessary process of normal life. However, in times of trauma or when facing disability, individuals may find it beyond their capabilities to adapt to circumstances without professional assistance. For a clearer understanding of adaptation it is recommended that the reader refer to Sister Callista Roy’s work The Roy Adaptation Model first published in 1984.

People involved in rehabilitation include children, adolescents, adults or older people; therefore, it is important for the nurse involved in rehabilitation nursing to apply relevant theoretical knowledge of the social, physical and psychological stages of development (Jester 2007).

The meaning of habilitation and rehabilitation

Habilitation, rather than rehabilitation, is a term that refers to the process in which a person who is born with an impairment is helped to achieve optimal independence and function by learning new skills that empower them to make choices and have degrees of control. Long-term habilitation programs are necessary for individuals born with conditions such as spina bifida, Down syndrome or intellectual or physical impairment.

One function of rehabilitation is to address long-term problems such as chronic health problems and degenerative diseases. Although there may be no cure for such conditions, a rehabilitation program can improve the quality of life. In this sense rehabilitation is directed towards the maintenance of optimal function and prevention of complications, or towards retaining the greatest amount of function and independence that the client desires for as long as possible.

Rehabilitation begins at the onset of illness or accident and continues until it is decided by the client, in consultation with the rehabilitation team, that the optimal level for that particular individual has been attained. The rehabilitation process may extend over a period ranging from a few weeks to several months or years.

Rehabilitation programs are conducted in a variety of settings, including acute care hospitals, specific rehabilitation institutions, day clinics, the home and in the community (Hoeman 2008).

PHILOSOPHY OF REHABILITATION

A philosophy is a broad statement of basic related principles, concepts and beliefs. A philosophy of rehabilitation offers a framework from which the rehabilitation process can be developed. Although rehabilitation teams devise their own philosophy, philosophies of rehabilitation are generally based on the premise that rehabilitation recognises the worth and uniqueness of the person as a valuable human resource, and that rehabilitation programs must be a major integral component of care offered by health services. Rehabilitation necessitates the participation and coordination of all health team members through constant communication with the client and significant others to develop a comprehensive rehabilitation plan acceptable to and agreed to by the client. The individual receiving rehabilitation must be viewed as an active team member, and the process must actively involve the family and significant others in the individual’s life. By doing this the rehabilitation process adopts a person-centred approach.

Rehabilitation is concerned with the whole person and includes the sociocultural aspects of the person’s life, sexuality, family and home, job, vocation, religion and community role. Rehabilitation aims to achieve the highest level of empowerment and independence possible for the individual and is client and goal focused (Derstine & Drayton-Hargrove 2001; Hoeman 2008).

Client-centred goals and empowerment

Goal setting can be seen as a way to give control back to clients and make empowerment real. As clients reach goals the nurse must help the client to realise that their achievements are due to their own abilities. The nurse can guide the client so that they are empowered in decision making, taking control and accepting that progress is due to their own effort. This knowledge will help them maintain the motivation to continue to strive for more independence.

In healthcare, empowerment is defined as an educational process designed to help clients develop the knowledge, skills, attitudes and self-awareness required to effectively assume responsibility for their health-related decisions. Empowerment is an approach that aims to establish the client’s autonomy and self-control and enables groups or individuals to change after being given the skills, resources, opportunities and authority to do so (Wang 2007). Traditionally, clients have been regarded as passive recipients of care, with healthcare providers being considered the experts. This view differs from the modern paradigm of empowerment in which the individual should become an expert in their own healthcare. This approach allows clients to acquire skills and knowledge for improving their overall health status and focuses on health promotion, clients’ abilities rather than disabilities and wellness rather than illness.

A partnership between team members and the client transfers power and builds on the client’s self-esteem and self-worth. Often clients in rehabilitation experience feelings of poor self-esteem and a sense of worthlessness. They can be grieving for what they perceive as a loss of independence and lifestyle. Client-centred goals can assist in identifying what is important to that individual. The client may not always set the goals at the level the team believes they should be able to achieve. It is not an effective use of resources if therapists aim for the client to walk 100 metres if the client only wants to walk around the house or only wants to be able to walk to the letterbox. The goals must be realistic and the client must have a desire to reach them. One of the most effective ways the nurse can empower the client is to offer choice. Asking the client what they would ‘normally’ prefer to do, and then allowing it to happen, is a step towards empowerment. The rehabilitation nurse should include the client’s own beliefs, wishes and goals in the delivery of care (Hoeman 2008).

The importance of the client feeling in control of what is happening, what is being planned and of decisions that affect their life cannot be emphasised strongly enough. Person-centred rehabilitation is precisely that—rehabilitation planned together with a client and their carers, families and friends, around their goals, needs and existing circumstances. There is great skill involved in empowering the client. This sense of control is facilitated when the client is involved in determining their own rehabilitation goals.

It is important for nurses working in the area of rehabilitation to keep in mind that throughout the process of rehabilitation the client and the family are often facing markedly changed circumstances and may be struggling to adapt to what has happened.

ADJUSTMENT TO DISABILITY

The process of adjustment as it relates to disability is similar to that in dying. (See Ch 36 for more information on loss, grief and dying.) Disability involves loss and is accompanied by an adjustment process as the individual and significant others learn to come to terms with the disability and its implications. The individual may experience loss of:

• Bowel and/or bladder control

• Ability to speak, read, write and comprehend

• Ability to relate to other people and the environment

The person whose disability has only occurred recently generally experiences four stages in adjustment during the rehabilitation process:

1. Acute disorganisation. The individual may express feelings of extreme anxiety, fear and disbelief that such an event has occurred

2. Assessment. The individual begins to assess what has happened and begins to recognise and identify changes in function and ability. The client may experience anger, depression, denial and bargaining. The individual may hope for a spontaneous recovery or a medical miracle, and tends to resist activities designed to help regain function from impairment

3. Mourning. The individual continues to experience anger and depression; however, there is generally a new awareness of the losses involved. The individual begins to accept the changed probable future and no longer denies or ignores the disability. Eventually the client begins to participate more fully in the rehabilitation program.

4. Re-entry. The individual resolves the depression of the mourning process and begins to experience more positive feelings about self and the future. They recognise that the disability does in fact exist and are keen to find means to adapt their personal lifestyle to the disability.

It is important for nurses to understand that each client will have an individual timetable for adjusting and adapting to living with a disability. Thus, while some people adjust in a relatively short time, others will take much longer. There is no normal period of time before a person finally accepts and adjusts to a disability. It must not be forgotten that the family also goes through a process of grieving and adjustment. The rehabilitation team plays an important role as it supports the individual and family during the process of adjustment and adaptation.

THE REHABILITATION TEAM

Effective rehabilitation involves client-centred care planning with the individual, family or significant others and the whole healthcare team. The special needs of the individual determine the fields of expertise that are represented in the rehabilitation team. An inter-professional team is required and consists of members from various disciplines, each with a vital role to play. Clinical Interest Box 38.4 identifies some of the people who might be included in a rehabilitation team. Which team members are included depends on the specific needs of individual clients; for example, a non-English speaking client would need an interpreter to be included.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 38.4 Members of the rehabilitation team

Members of the rehabilitation team

The client

It is essential that the individual who requires rehabilitation be viewed as the pivotal team member. The other team members must help motivate the client to be actively involved in the rehabilitation process, however slow it may be. Unless the client is encouraged, a lack of motivation and cooperation with prescribed therapy may result. It is important that each small achievement is positively reinforced (e.g. recognised, praised or rewarded). At all stages of rehabilitation, the rest of the team must consider the client’s strengths and weaknesses and the social and cultural influences that affect adjustment to disability. The team must be aware of how the client perceives the illness and the impact of the disability that has occurred.

A disturbance of an individual’s body image—for example, paralysis resulting from a cerebrovascular accident—is difficult to accept. The initial reaction is usually one of shock, followed by denial. As the individual gradually realises what has happened and that life may never be the same again, they may experience depression, anger or guilt. Self-esteem and self-worth are threatened (see Ch 36). While there is inevitable dependency initially, the overall aim of rehabilitation is to help the individual regain optimal quality of life. The motivation of the individual is crucial, and it is essential that the client be regarded as the most important team member, who must be encouraged to participate actively in all aspects of the rehabilitation process. The individual must be involved in planning the personal rehabilitation program with the team. The client must learn in detail about the disability that has been experienced and ways of accomplishing the desired goals. The team must inform the client as to what options are available so that the person can choose the best options for a successful outcome.

The family or friends

The family, or significant others, are recognised as a potential support system for the individual. Members of the family are evaluated to determine their ability to help with the rehabilitation process. All families, or significant others, cannot contribute in the same way or to the same degree. In some instances the individual can return home and receive excellent care and support, while in other situations the family may be unable or unwilling to help care for the person. As each situation presents different problems, individual evaluation is essential.

The family, or significant others, need to understand and/or be involved with the rehabilitative goals that the individual develops with the team, and the methods selected to meet these goals. Partners, family members or supportive friends need to understand that their greatest contribution may be to allow the individual to be as independent as possible. This may be difficult for them at times, as their natural instinct may be to assist and ‘do for’ their loved one. In addition, those supporting the client can be instructed in how to assist with specific therapy, thus enabling them to feel that they are playing a vital role in rehabilitation.

It is important to understand that when illness or disability occurs, family life is interrupted and altered. The effects of illness have significant implications for the family as well as for the individual. Plans for the rehabilitation process should, therefore, also address the needs of the family as well as those of the client. The nurse and the team must remember that a spouse or partner can become depressed if their loved one faces permanent lifestyle changes. It is important to inform the spouse or significant other that this is a normal reaction and encourage the person to seek assistance from a medical officer or team psychologist. Another concern with family occurs when ageing carers assisting relatives with disabilities in the home environment themselves become ill and are no longer able to provide care for their dependent relatives. People who have been cared for by their loved ones in the community for many years are sometimes suddenly faced with a crisis because that carer has become ill. This often limits the amount of support that the carer has for transition back into the community, and placement of the individual they cared for may be an issue if the carer cannot resume a level of functioning that enables a return to the role of carer.

The nurse

Rehabilitation nursing is a speciality area of practice requiring specialised knowledge, skills and attitudes (see Clinical Interest Box 38.5). The goal of rehabilitation nursing is to assist people with disability and chronic illness to attain maximal functional ability, maintain optimal health and adapt to an altered lifestyle (see Clinical Interest Box 38.6) (Hoeman 2008). Nurses are in a prime position to promote these things because they spend more time with the client than any other member of the rehabilitation team, and therefore play a pivotal role in assessing, planning, implementing and evaluating care. A nursing assessment includes an evaluation of the extent to which the individual’s physical and psychosocial needs are met.

In rehabilitation, a registered nurse (RN) makes a nursing assessment and develops a nursing care plan to meet the needs of the client, taking into account the person’s goals, both short and long term. An enrolled nurse (EN) provides care under the direction of the registered nurse. In many settings, nursing is the only component of the rehabilitation team represented throughout the entire 24 hours of each day. Nurses are therefore responsible for reinforcing the teachings of other team members, such as the physiotherapist and occupational therapist, throughout this time, so that there is continuity of the rehabilitation program. The rehabilitation nurse’s role includes preventing complications that would impede the restoration of optimal functioning; therefore, attention to potential problems as well as actual problems is necessary.

The effective rehabilitation nurse understands the short- and long-term goals of the client and the rehabilitation program. The nurse has a pivotal role in the multidisciplinary team and is aware of the need to liaise and communicate closely with all team members to achieve coordinated and effective outcomes for the client. This often means that the nurse’s role needs to be flexible and amenable to change. The nurse requires a full understanding of the role and function of each team member and needs to recognise when to refer to the expertise of others as the client’s needs indicate.

Individuals react and respond in various ways to personal health conditions and the rehabilitation program. The nurse must be able to assess accurately, monitor and educate the clients and their significant others throughout the process, so that the client’s goals and the rehabilitation goals can be achieved successfully. The nurse works in a partnership with the client, assisting them to make informed choices and have control over the process. At times the nurse might find it difficult to empower the client, especially if the client is despondent and in the early stages of denial. It is essential that the nurse takes time to build rapport and trust. Client advocacy is vital for this trust to develop. The nurse should be responsive to the client’s rights and be able to advocate for the client in team discussions. The nurse’s role involves being an educator, not only for the client but also for the family, carers and other staff. This education will involve teaching rehabilitative techniques, preventing complications and promoting a healthy lifestyle. The nurse will act as a resource for information and clarification and know when to call in other professionals to assist.

Many clinical skills are employed when working as a rehabilitation nurse. Depending on the individual client, skills employed may include pain and continence management, preventing pressure areas, wound management and behaviour management. While the rehabilitation nurse needs to acquire excellent general nursing knowledge, there may be a necessity to refer to more advanced trained rehabilitation nurses specialising in neurological, orthopaedic, cardiac/pulmonary, oncology, renal, gerontic or paediatric rehabilitation nursing. The rehabilitation nursing team members between them commonly have a skill mix that meets the needs of the client.

Rehabilitation nursing takes place in any specialty or clinical environment where the aim is to maximise independence and minimise the impact of disability and handicap in clients with particular impairments. Therefore, many nurses, including those who have not specialised in rehabilitation nursing, are involved in the rehabilitation process. However, should a nurse choose to make rehabilitation nursing a career focus, there are many different specialty areas of rehabilitation nursing, including orthopaedics, burns, spinal injury, head injury, amputation, cardiac and stroke rehabilitation (Jester 2007).

The case manager

The case manager can be of any discipline. It is fast becoming a very popular role for the rehabilitation nurse with advanced training. The case manager develops a formal, written, comprehensive needs assessment that includes a formal review of evaluations performed by other members of the rehabilitation team. The case manager assists the client and the service provider in planning and program development that meets the client’s needs as identified and prioritised in the assessment. The case manager’s role and function will vary depending on the practice setting. The case manager may be employed in an institutional setting such as a hospital or rehabilitation facility, or they may work in the insurance industry, such as the Transport Accident Commission or a health insurance organisation.

The physiotherapist

Physiotherapists evaluate the client’s physical capabilities and limitations in a collaborative assessment process. The physiotherapist administers therapies designed to correct or minimise deformity, increase strength and mobility or alleviate discomfort or pain. The physiotherapist has a client-centred approach. Treatments include the use of specific exercises, heat, cold, aqua therapy and electro-physical therapy. A physiotherapist is also involved in educating the client and their family or significant others and other team members in correct methods of positioning, transferring and mobilising so that what is taught in therapy sessions can be carried over to day-to-day activities and reinforced by the nurse.

Physiotherapy will help with weak or tight muscles, stiff joints, poor coordination, balance, stair practice, walking and general fitness along with everyday functional activities such as rolling in bed, sitting, standing up and reaching forward/using hands.

The occupational therapist

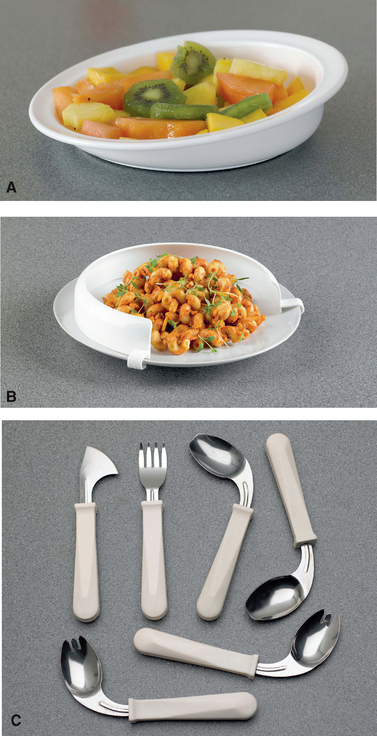

Occupational therapists are concerned with assisting the client to achieve independent performance in the activities of daily living. They also assess the need for, and provide, adaptive devices, for example aids such as specially designed cutlery or making a splint for someone’s hand so they can grasp their cutlery to feed themselves.

The occupational therapist usually assesses the client’s home in preparation for transition back into the community. This is done in conjunction with the client and family on the pre-discharge home visit. Home modifications may be required to a client’s home to ensure their wheelchair will be able to be manoeuvred in all areas of their house and ensure it is safe for them. Equipment may need to be provided to ensure that the home environment is safe and conducive to the client’s independence level. Modifications may be minor, such as installation of a handrail, or major, such as structural alterations to enlarge space in a toilet and bathroom if a wheelchair or lifting machine needs to be accommodated. The occupational therapist may also be involved in teaching someone with memory problems strategies so that, for instance, they can remember to purchase everything they need at the supermarket.

The speech pathologist/therapist

Speech pathologists, otherwise referred to as speech therapists, are also involved in the client goal-setting process. They are concerned with assessing, diagnosing and treating communication disorders, such as the formation and perception of speech, the ability to articulate words and to understand and initiate speech, retraining reading and writing skills following a stroke or teaching someone how to speak after a traumatic brain injury. As part of the rehabilitation process a speech therapist may be required to assist a person to relearn communication skills. Communication deficits present a real problem for affected clients, and much reassurance and counselling are often required. The client who cannot speak may feel hopeless and frustrated. Often, depending on the area of brain affected by a cerebrovascular accident, the client can understand fully but cannot articulate. Technical devices may need to be used to assist the client to communicate with others. If both areas of the speech centre are damaged, global aphasia may occur, in which the person cannot speak or understand the spoken word. How to empower this client is a very real challenge.

A speech pathologist may also be involved in the management of an individual whose chewing and swallowing abilities are impaired, for example, after a cerebrovascular accident. The speech pathologist liaises closely with the nurse, dietitian and family to achieve safe swallowing strategies for the client. In consultation with the client, a videofluoroscopy may be required to ascertain the extent of the swallowing deficit (see Clinical Interest Box 38.7). Often the client and family will resist the strategy of thickened fluids to prevent aspiration; therefore, in-depth education and counselling are required so that informed choices, including a full understanding of the risks, can be made. Ultimately it is the client’s choice as to whether treatment strategies are followed.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 38.7 Videofluoroscopy—a diagnostic test to identify dysphagia

Videofluoroscopy is a modified barium swallow conducted by the speech pathologist and radiologist to determine the extent of dysphagia and to identify if the client is at risk of aspiration. The test allows for the viewing of the oral cavity, laryngopharynx and cervical oesophagus. The client swallows small amounts of a liquid puree or solid mixed with barium. As the client manipulates the bolus in the oral cavity and swallows, the fluoroscopic study is recorded on videotape. Videotaping of the swallowing study allows clinicians to have repeated viewing and slow-motion analysis.

The social worker

Social workers are concerned with counselling and assisting clients and their families who are experiencing personal problems as a result of illness or injury. A social worker acts as an advocate by liaising with existing community groups and resources, and assists the individual and the family to deal with social, domestic, financial and emotional implications of the illness or condition. The social worker engages in discharge planning and often accompanies the occupational therapist and client on the pre-discharge home visit. The social worker communicates with the community services that may be required to assist the client when discharged home or, if alternative placement is required, the social worker would assist in this process.

Social workers assist clients and their carers to deal with the emotional impact of illness, traumatic injury and disability and the adjustment to hospitalisation. Social workers help clients and carers to adjust to life changes and challenges, deal with grief and loss, explore emotions, thoughts and behaviour, improve relationships and plan for the future.

Social workers provide counselling to individuals and families, assist clients with financial, accommodation, legal and other problems, run groups to provide support for carers, participate in discharge planning and link clients to community support services for assistance post-discharge.

The dietitian

Dietitians are concerned with assessing nutritional needs and planning ways to meet those needs. As part of the rehabilitation process, the client may require specific dietary restrictions or modifications, and a dietitian collaborates closely with the individual to plan an appropriate diet. The dietitian also plays an important role in ensuring that all those involved with the individual’s care understand the importance of a specific diet for the person’s recovery. Nutritional screening is also important for those clients over the age of 65.

The podiatrist

Podiatrists are concerned with assessing, preventing and treating disorders of the feet. As part of the rehabilitation process, a client may be required to relearn how to ambulate, for example, after a cerebrovascular accident. In order to mobilise, the feet must be in good condition, with no skin lesions or nail disorders, and the podiatrist plays an important role in maintaining the health and integrity of the skin and toenails. In collaboration with the client, the podiatrist determines appropriate footwear for safe mobilisation.

The prosthetist/orthotist

Prosthetists are concerned with assessing a client’s need for prosthesis, such as an artificial limb. After assessment, a prosthetist designs and supplies an appropriate prosthesis. Generally a temporary prosthesis is provided and trialled before a permanent one is supplied. Modifications to an existing prosthesis may be made by a prosthetist who also checks at regular intervals to ensure that the prosthesis is meeting the client’s needs. Some individuals may need to be fitted with splints or braces to correct deformities or provide added support. Such mechanical devices are called orthoses, and include braces for the neck, arm or leg.

The psychiatrist and psychologist

If the client is experiencing a psychiatric or emotional problem, either a psychiatrist or a psychologist is generally involved in the rehabilitation process. A psychiatrist is concerned with the causes, prevention and treatment of mental, emotional and behavioural disorders. A clinical psychologist is concerned with the causes, prevention and treatment of individual social problems especially in regard to the interaction between the client and the physical and social environment. A psychiatrist, clinical psychologist or neuropsychologist may be involved in the rehabilitation of an individual who is depressed as a result of the implications of the disability, or if behavioural problems result from the condition. The psychologist can also assist the rehabilitation team with strategies to manage clients who have behavioural disturbances that impact on the day-to-day rehabilitation process. These disciplines can also assist the family or significant others if problems of coping and adaptation are identified. Depression can be common in the client undergoing rehabilitation; family members are also vulnerable to depression.

The clinical director (medical officer)

The clinical director is commonly a medical officer specialising in rehabilitation medicine and often the first member of the team to encounter the client as a response to a referral for rehabilitation intervention. The medical officer is responsible for the medical and/or surgical management of the person and oversees the treatment that involves meeting the physical, emotional and social needs of the client. These needs must be satisfied to successfully restore the client’s quality of life to maximum potential. The medical officer collaborates with all members of the team and is usually the team leader. They assess the client’s health status regularly and explain the diagnosis and prognosis to the client and relatives. The medical officer often takes on the role of chairing the case conferences and other meetings, such as team and family meetings. Regular ward rounds are conducted by the medical officer, who also has an active educative role with team members, particularly for more junior medical members of the team.

Case conferences and team meetings

These meetings are held at regular intervals and are the forum at which team members discuss the progress and problems of every individual who is undertaking rehabilitation. During these meetings the client’s short- and long-term goals are discussed, with each member being aware of, and respecting, the roles of others in accomplishing these goals. Goals must be re-evaluated regularly with the client, so that the client and therapists can determine whether they are realistic and/or whether they have been accomplished. All goals should be set with specific time frames. Specific therapy goals are also set at these meetings. These therapy goals are compatible with the client’s goals but are usually broken up into smaller attainable sequences, with time frames; for example, John will stand for 3 minutes, with the aid of the tilt table, three times tomorrow; John will increase time on the tilt table in increments of 2–3 minutes until standing for 10 minutes three times a day.

Each team member explains to the other members the procedures and techniques to be carried out. The proceedings are documented in terms that are meaningful and valid for all persons concerned. The client and/or family may or may not be present at the case conference, depending on the time limitations of the meeting and the individual healthcare facility’s policy. Quite often a designated team member meets with the client and family before or after the meeting to discuss and inform and assist in the decision-making process. Family conferences can be conducted aside from the case conference, when more time can be given to the concerns of the client and family.

THE PROCESS OF REHABILITATION

The rehabilitation process involves assessing the client’s rehabilitation potential, planning and implementing an appropriate program and continuous evaluation of progress (Jester 2007).

Assessment of rehabilitation potential

Assessment of the client and a realistic evaluation of their rehabilitation potential is the first step towards planning a program (see Clinical Interest Box 38.8). In some instances this can be a relatively simple process, while in others it is more complicated. For example, it is comparatively easy to assess the rehabilitation potential of a healthy young adult with a fractured femur, while it is more difficult to make an assessment in an elderly person with diabetes who has experienced a cerebrovascular accident.

Assessment may take the form of observation, listening, interview, physical exam and consultation with other team members and/or family.

Assessment of each individual must take into account:

• The nature of the disability. Some conditions affect only isolated areas of the body, while others exert widespread effect. Some disorders cause progressive and diverse impairment of function

• The overall condition of the client and their ability to cope with a rehabilitation program. There may be other existing conditions that could influence the choice of rehabilitation measures; for example, chronic conditions such as arthritis or emphysema may restrict the person’s ability to engage in active exercise

• The motivation of the client and the understanding of the situation. The client’s motivation should stem from a realistic acceptance of the situation and should not be the result of over-optimism or a refusal to acknowledge limitations

• The client’s home environment and the ability of the family or significant others to be supportive.

Physical and psychological assessment of the client is performed to evaluate functional state, so that a suitable program involving both short- and long-term goals can be set (Eliopoulos 2010). Assessment includes evaluating muscle function, range of joint motion, body alignment and posture, neurological function, cardiopulmonary function, mood and cognition. The assessment should identify both the abilities and the limitations of activities of daily living and mobility.

A number of tests can be used to assess functional ability and activities of daily living and include the Functional Independence Measure and the Barthel Index. The FIM is an 18-item assessment used to measure the individual’s ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) related to self-care, elimination, locomotion, transfers, communication and cognition. The Barthel Index measures the client’s ability to perform in relation to 10 domains of motor function (see Clinical Interest Box 38.9).

Assessment of concerns/alterations to sexual function should also be taken into consideration (see Clinical Scenario Box 38.1).

Clinical Scenario Box 38.1

Jill’s experience

Jill, aged 35, was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) 3 years ago. She is married to David and has a 6-year-old daughter. She continues to work 2 days a week as an administration officer. Recently she fell and fractured her arm and needed to stay in hospital for rehabilitation.

The nurse on night duty found Jill in the day room, unable to sleep, so she made her a drink and sat with her for a while. After some small talk about Jill’s job and her daughter she asked, ‘How has having MS affected your life?’, and later, ‘How has it affected your relationship with David?’ She discovered that Jill and David were not getting on so well, mostly because they didn’t have sex anymore because it was ‘too difficult now’. The nurse asked, ‘What has changed that makes it difficult?’

She discovered that Jill was experiencing painful cramps and spasms in her legs at night that made it impossible to get comfortable and sometimes made it difficult to separate her legs at all. Jill seemed to believe that this was part of the MS that she must accept. The nurse reassured her that cramps and spasms could be helped by medication or physiotherapy and suggested that Jill think about contacting her doctor and the Multiple Sclerosis Society for expert advice. She gave Jill a copy of the Multiple Sclerosis Society information brochure and offered to contact the society on her behalf if she wished.

Assessment is an ongoing process that informs every client–nurse contact for the rehabilitation nurse. See Clinical Interest Box 38.8 for the Australasian Rehabilitation Nurses’ Association (ARNA) position statement on assessment.

Determining short- and long-term goals

Short-term goals of a rehabilitation program are those that may be achieved in a short period of time. For example, activities such as achieving a standing position, moving from a bed to a chair, managing meals independently, tying shoelaces or formulating a sentence may be set as short-term goals. Long-term goals are those that are expected to take much longer to accomplish and depend on success in achieving the short-term goals. These may include activities such as walking, managing to climb stairs, independence in the activities of daily living or returning to employment.

The value of setting goals is that both the client and the team know what they are aiming for and will be able to identify when they have achieved a specific goal. As mentioned earlier, the client and family assist in the development of the goals and this assists in empowering the client and providing a degree of control. If realistic goals are to be set the entire rehabilitation team must be involved in the planning process and must meet frequently to re-evaluate the situation.

It may be difficult for a client to maintain a high level of motivation and they may think that little progress is being made and that the set goals are unattainable. They may view the rehabilitation program as tedious, boring, exhausting or painful. As a result, they may become depressed and discouraged. The nurse may help by:

• Being empathic about the situation, which involves trying to understand how the client is feeling

• Emphasising what progress has been made and expressing honest confidence in the person’s ability to make further progress

• Spending as much time as possible with the person, particularly during activities in which active encouragement is required

• Ensuring that the client does not become over-tired or attempt to exceed the limits prescribed. Encourage the client to take one day at a time. Some days will be better than others

• Encouraging the individual to concentrate on achieving one goal at a time. An over-ambitious program may result in frustration and despair

• Encouraging the individual to express feelings. A relationship can be established by listening to the client. This creates a sense of trust so that the client feels able to express concerns and feelings to the nurse (see Ch 6).

PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTATION

Nursing aspects of rehabilitation

Based on goals set, a collaborative plan of action needs to be developed. The nursing activities involved will depend on many factors such as the client’s age, degree of independence and type of impairment. The overall purpose of rehabilitation is restoration of the individual to optimal functioning, or to assist the individual to adjust to a disability after an illness or injury. As a member of the rehabilitation team, the nurse provides support and assists the client to meet personal physical and psychological needs. Nursing care may include care of the skin, hygiene, nutritional care, continence, sexual health, activities of daily living, wound management, medication administration, mobility and transfers.

Regardless of the specific impairment, the philosophy and aims of rehabilitation remain the same. The nurse plays a key role in assisting the client to carry out the activities of daily living and must be aware that the ultimate aim is to achieve the goals that the client has developed with the team. The achievement of personal goals that the client has developed is one of the most important aspects of their rehabilitation.

For example, in a program developed for a person who has experienced a cerebrovascular accident and subsequent hemiplegia, one specific long-term goal may be that the person is able to dress themselves. For that goal to be achieved, short-term goals will be set, such as ‘The person is able to sit up in a chair’. The occupational therapist will be involved in teaching dressing and undressing techniques, and the nurse should understand the techniques the person is using so that the teaching of the occupational therapist can be reinforced in day-to-day activity (see Clinical Scenario Box 38.2).

Clinical Scenario Box 38.2

Roger, an 88-year-old, lives by himself, and has fallen over while gardening. He fractured his hip and required surgery. He was admitted to the rehabilitation unit 7 days after surgery for a reconditioning program.

He is on a combination of antihypertensive and cardiac medications. He requires the administration of aperients to keep his bowel actions regular. He suffers from occasional urinary incontinence and uses a pad at night. He is able to walk with a frame, and requires assistance with transfers, dressing his lower body and applying his antiembolic stockings. He progressed well with his therapy and after a home visit identified modifications required for his bathroom and these were attended to, he was ready to be discharged home, 2 weeks after admission.

Continuity of care is vital for effective rehabilitation outcomes. The client’s day should be planned to maximise the rehabilitation process. It is also important that the nurse working with the client is aware of the plan, and works with them to achieve their goals. There is a tendency to ‘get the work done’ and, rather than allowing the time for the client to wash and dress themself, the nurse does it for them because it is quicker than supporting them to do it themselves. It is destructive to the rehabilitation process for the nurse to take over when a client is attempting to dress themselves; for example, doing up the buttons on a shirt when a client is making slow progress may save the busy nurse time, but it undermines the importance of the client’s efforts and may deter the client from trying in the future.

One important nursing function is to prevent the complications of immobility (Crisp & Taylor 2009; Hoeman 2008) which include:

(See Ch 26 for more information concerning mobility.)

Evaluation

Progress towards achieving goals needs to be reviewed regularly, and is a collaborative approach between client, family and all the team members. Evaluation of progress may take the form of client self-reporting, physical measurements such as timed walking, range-of-joint movements, quality-of-life indices and team reports based on observation and interaction with the client. Based on this evaluation the client’s goals and action plan should be reviewed and amended as required.

Aids to daily living

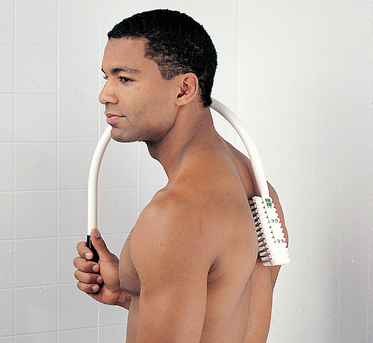

There are numerous devices to help a person with a disability perform the activities of daily living. Such devices are invaluable, as they make a degree of independence possible. For example, there are long-handled shoe horns to promote independence with dressing (Fig 38.1), long-handled brushes to promote independence with hygiene (Fig 38.2) and devices to promote independence with meals (Fig 38.3) and drinking (Fig 38.4). Nurses should be familiar with the full range of aids available and should be capable of teaching the individual and their family the correct way to use them. A range of available aids is listed in Clinical Interest Box 38.10.

Figure 38.3 Aids to promote independence with eating A: Scoop dish B: Food guard C: Easy hold utensils (knife blade cuts in both slicing and rocking)

(Patterson Medical USA)

Figure 38.4 Aids to promote independence with drinking. Tumbler with a special cut-out for the nose allows the client to drink without tipping the head back

(Patterson Medical USA)

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 38.10 Aids to independent living

• Suction devices fitted to kitchen utensils, backs of nail brushes, etc, for the benefit of a person with the use of only one hand

• Boards with spikes to hold fruit or vegetables to be peeled, or bread to be buttered

• Face washers in the shape of a mitten, with a pocket to hold the soap

• Long-handled tongs for a person who is unable to pick items up by bending or stooping

• Dressing sticks with one end covered by foam rubber to grip the sleeve or shoulder of a garment, making it easier to don and remove

• Various devices to enable socks and stockings to be put on

• Overlapping adhesive fastenings (e.g. Velcro) on clothing for people unable to manage other conventional types of fastenings

• Long-handled shoe horns to make bending or stooping unnecessary (Fig 38.1)

• Elastic shoelaces, which do not have to be untied when shoes are removed

• Cuffs which, when placed over the hand, hold a pencil, toothbrush or razor

• Chairs with an ejector seat, which rises as the occupant leans forward

• Hand grips in bathroom and toilet areas

• Long-handled brushes to enable clients to perform their own hygiene activities (Fig 38.2)

• Low-level fittings for occupants of wheelchairs (e.g. sinks, stoves, mirrors, light switches)

In Australia and New Zealand there are centres for independent living that provide a wide range of aids to assist with the tasks of daily living. A variety of community services is available to assist persons with disabilities to remain at home, including community health centres, day hospitals and day centres, drop-in centres, elderly/senior citizens clubs, self-help groups, home nursing services, home meal services and sheltered workshops. Nurses should be aware of the state/territory-specific social welfare services and agencies, most of which are can be found in the telephone directory or through an internet search for community services, in both Australia and New Zealand.

CULTURALLY RELEVANT CARE

Outcomes, interactions and responses are influenced by social and cultural factors. In rehabilitation, nurses can bridge cultural barriers to facilitate and improve outcomes. Family members or significant others are also interviewed to obtain accurate information as to pre-morbid functional status, personal interests, cultural considerations and discharge plans affecting the rehabilitation admission.

For those individuals from cultures different to that of the nurse, the nurse needs to take into consideration cultural influences—of their own and of the client—on participation and decision making.

While 65 years of age is traditionally used as the point where the term ‘older aged’ may be applied, in the non-Indigenous community, Indigenous people would regard a person over 45 years as an older person requiring aged care services. The Indigenous population experience significantly greater morbidity and premature mortality compared with non-Indigenous people (Hunter New England Health 2006). This is a result of, among other things, the increased prevalence of chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, kidney disease, chronic respiratory disease and cancer.

In New Zealand one objective of the Māori Health Strategy (Ministry of Health 2002) is to improve access for Māori to mainstream health services, of which inpatient rehabilitation units form a part. Older Māori clients may be more willing to participate in rehabilitation if their whānau (family) are able to participate more fully in their therapy.

Discharge planning

Discharge planning prepares the client for the transition to another setting, such as from hospital to home. It is the link between hospitals, community-based services, organisations, families and carers. The elements of the discharge planning process should begin on the day of admission. The overall goal of discharge planning is to promote continuous healthcare services to meet the individual’s needs (see Ch 19). Effective discharge planning can decrease the chances that a person is readmitted to the hospital, can help identify care issues and needs and enable appropriate care plans to be developed.

Although discharge planning is a significant part of a person’s overall care plan, frequently there is a lack of consistency in both the process and the quality of discharge planning across the healthcare system.

An effective discharge plan depends on the resources available to the individual who is being rehabilitated. Available resources include:

• The family or significant others—the client’s support systems

• Social and counselling agencies

• Volunteer community services

• Support and special interest groups; for example those dealing with, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, cancer, heart conditions, arthritis

• Medical supplies and equipment

• Adaptation of the home environment for safety and optimal independence.

The client and the nurse, together with other team members, assist in coordinating and developing the discharge plan, using the steps of the nursing process to achieve the final plan. A discharge planner or continuing care coordinator is sometimes part of the hospital staff and functions as a consultant for the discharge planning process within a health facility, providing education and support to hospital staff in the development and implementation of discharge plans.

Summary

Rehabilitation is a dynamic process in which clients are helped to achieve optimal quality of life by increased function and independence, within the limits of their disability. A disability is any physical, mental, emotional or social impairment that limits a person’s ability to carry out an activity in the usual manner.

Effective rehabilitation involves the client, family or significant others and professional members of the healthcare team. As part of the rehabilitation team, the nurse plays a vital role in helping the individual to meet physical and psychological needs as independently as possible. The rehabilitation process empowers the client to make informed decisions and choices about treatment modalities, care regimens and lifestyle options.

Mr Jones, 55, has experienced a motor vehicle accident in which he suffered multiple fractures of both legs. He has worked hard during the restorative phase of his illness and is able to walk short distances with the aid of forearm crutches. Plans are in progress for his discharge home. His wife and two children, aged 6 and 9, live at home. Because of financial pressures, Mrs Jones cannot give up her full-time paid work to care for him during the day.

a. Discuss the role and function of the nurse in planning for Mr Jones’ discharge.

b. Identify the issues that Mr Jones might face on returning to the community.

c. What options might need to be discussed with the client and family in relation to decreasing the potential for falls or other injury when he returns to the community?

d. Describe three community services or other resources that could help to facilitate a successful community re-entry for Mr Jones.

1. What are the main goals of a rehabilitation program?

2. What are the stages of the rehabilitation process?

3. List three (3) methods of assessment the nurse could be involved in when a rehabilitation program is being planned for a client who has experienced hemiplegia as a result of a cerebrovascular accident (stroke).

4. List three (3) ways a rehabilitation nurse can assist in empowering the client who has lost the ability to speak but can understand.

5. List three (3) areas of health education that might be helpful for the rehabilitation nurse to provide for an older client who has recently been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

6. List four (4) roles within the rehabilitation team that the nurse may undertake.

7. List four (4) settings in which the rehabilitation nurse may function, and identify six (6) types of illness, condition or injury that clients might experience in which rehabilitation would be essential.

References and Recommended Reading

Australasian Rehabilitation Nurses’ Association (ARNA). Position Statement: Rehabilitation Nursing—Scope of Practice, 2nd edn. ARNA, 2002. Available: www.arna.com.au/position.html.

Australasian Rehabilitation Nurses’ Association (ARNA). Rehabilitation Nursing Competency Standards for Registered Nurses. Available: www.arna.com.au/pdfs/competencystandards.pdf, 2004.

Association of Rehabilitation Nurses. (nd) Make a difference [brochure]. Available: www.rehabnurse.org/pubs/content/makedifference.html.

Chew D, Brook D, Sheridan K, et al. Evaluation of an integrated care plan for rehabilitation. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;25(2):62–69.

Crisp J, Taylor C. Potter & Perry’s Fundamentals of Nursing, 3rd edn., Sydney: Elsevier, 2009.

Davis S. Rehabilitation: The Use of Theories and Models in Practice. Oxford: Churchill, 2005.

Davis S, O’Connor S. Rehabilitation Nursing Foundations for Practice. Edinburgh: Baillière Tindall in association with Royal College of Nursing, 1999.

Derstine B, Drayton-Hargrove S. Comprehensive Rehabilitation Nursing. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001.

Eliopoulos C. Gerontological Nursing, 7th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.

Flannery J. Rehabilitation Nursing Secrets. Sydney: Elsevier, 2004.

Gibbon B. The contribution of the nurse to stroke units in the United Kingdom. Journal of the Australasian Rehabilitation Nurses’ Association. 2003;6(2):8–13.

Hitchcock JE, Schuber PE, Thomas SA. Community Health Nursing: Caring in Action. New York: Thomas Delmar Learning, 2006.

Hoeman SP. Rehabilitation Nursing. Process, Application & Outcomes, 3rd edn. St Louis: Mosby Year Book, 2002.

Hoeman SP. Rehabilitation Nursing. Prevention, Intervention & Outcomes, 4th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2008.

Hunter New England Health. Aged Care and Rehabilitation Services Plan 2006–2010. Available: www.hnehealth.nsw.gov.au, 2006.

Jester R. Advancing Practice in Rehabilitation Nursing. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Kearney PM, Pryor J. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) and nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;462:162–170.

Mackey H, Nancarrow S. Enabling Independence: A Guide for Rehabilitation Workers. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

Mahoney FI, Barthel D. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Maryland State Medical Journal. 1965;14:56–61.

Ministry of Health. He Korowai Oranga: Māori Health Strategy. Available: www.health.govt.nz/publication/he-korowai-oranga-maori-health-strategy, 2002.

Murphy G, Peterson C. On the death of the informal organisation. Australian Journal of Career Development. 2008;17:75–77.

Murphy G, King N, Ollendick T. Identifying and developing effective interventions in rehabilitation settings. Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling. 2007;13(1):14–19.

National Health and Medical Council (NHMRC). Strengthening Cardiac Rehabilitation and Secondary Prevention for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Available: www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines/publications/ind1-ind2, 2005.

Pryor J. Creating a rehabilitative milieu. Rehabilitation Nursing. 2000;25(4):141–144.

Pryor J, Smith C. A Framework for the Specialty Practice of Rehabilitation. Sydney: Rehabilitation Research and Development Unit, ARNA, 2000.

Pryor J, Walker A, O’Connell B, et al. Opting in and opting out: a grounded theory of nursing’s contribution to inpatient rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2009;23:1124–1135.

Rieg LS, Mason CH, Preston K. Spiritual care: practical guidelines for rehabilitation nurses. Rehabilitation Nursing. 2006;31(6):249–256.

Roper N, Logan W, Tierney A. The Roper-Logan-Tierney Model of Nursing Based on Activities of Daily Living. Sydney: Elsevier, 2000.

Royal Australian College of Physicians (RACP). National Rehabilitation Strategy Position Statement. Available: www.racp.edu.au, 2009.

Royal College of Nursing. Role of the Rehabilitation Nurse. Available: www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/111752/003178.pdf, 2007.

Smith M, ed. Rehabilitation in Adult Nursing Practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1999.

Spasser MA, Weismantel A. Mapping the literature of rehabilitation nursing. Journal of the Medical Library Association. 2006;94(2 suppl):E137–E142.

Stein J, Winstein C, Zorowitz R, et al. Stroke Recovery and Rehabilitation. New York: Demos Medical Publishing, 2008.

Wade DT. Goal setting in rehabilitation: an overview of what, why and how [editorial]. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2009;23(4):291–295.

Wang L, Dong J, Gan H, et al. Empowerment of patients in the process of rehabilitation. Peritoneal Dialysis International. 2007;27:32–34.

World Health Organization (WHO). The International Classification of Functioning: Disability and Health. Geneva: WHO, 2001.

Ability First Australia Disability Services, www.abilityfirstaustralia.com.au.

Association of Rehabilitation Nurses (USA), www.rehabnurse.org.

Australasian Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine, www.racp.edu.au/page/racp-faculties/australasian-faculty-of-rehabilitation-medicine/.

Australasian Rehabilitation Nurses’ Association, www.arna.com.au.

Enabled, www.enabledonline.com.

National Rehabilitation Centre (USA), www.cais.com.

New Zealand Rehabilitation Association, www.rehabilitation.org.au.