CHAPTER 26 Movement and exercise

At the completion of this chapter and with some further reading, students should be able to:

• Describe and implement the principles of good posture and body mechanics

• Describe the role of the musculoskeletal system in the regulation of movement

• Describe how joints are involved in movement

• State differences between isotonic, isometric and isokinetic exercise

• Describe and define range of movement (ROM)

• Identify and demonstrate joint movements involved in ROM exercises

• Define obesity and describe how variables such as family values and diet influence adult obesity

• Describe how older adults may benefit from exercise

• Identify and describe the complications associated with immobility and implement appropriate preventive measures

• State the influences and effects associated with disorders of the musculoskeletal system

• Identify the major musculoskeletal system disorders that impact movement and exercise

• Describe the major manifestations of musculoskeletal system disorders

• Briefly describe the specific disorders of the musculoskeletal system outlined in this chapter

• Define the diagnostic tests that may be used to assess musculoskeletal function

• Assess clients for impaired mobility and activity intolerance

• Assist in planning and implementing nursing care plans for clients with a musculoskeletal disorder

• According to specified role and function, perform the nursing activities described in this chapter safely and accurately in the clinical environment

isotonic/isometric/isokinetic exercise

orthostatic or postural hypotension

Movement and exercise are essential components for restoring, maintaining and enhancing physical and psychosocial health. As society becomes increasingly sedentary in both work and home environments, government and health agencies are researching and evaluating the effects of inactivity on health, disease processes, ageing and morbidity. Research suggests that despite the rising trend in health conditions related to obesity and immobility, the commencement of an exercise program can retard and even reverse the progression of conditions such as osteoporosis, heart disease, diabetes mellitus and the effects of ageing.

The human body is ideally suited to movement. Regular exercise promotes health, feelings of wellbeing and prevents illness throughout the life span. Exercise is made possible by the muscular, skeletal and nervous systems. These interconnected systems work together to make movement possible and for most human movement they must function effectively for optimal physical performance. Disease processes that disable one or more of these systems may inhibit or restrict mobility. To ensure mobility and exercise are maximised and maintained, allied health teams should devise care plans to meet individual needs and abilities based on the specific strengths and disabilities of each client in their care.

Healthcare workers are in a unique position to educate and support clients to make lifestyle changes for improvement in health and prevention of disease. Effective and timely health promotion can significantly contribute to long-term client health and potentially reduce disease progression and hospital re-admission. For those with recurring mobility issues, nurses and allied health professionals can support the transition to mobility aids and promote independence and quality of life on discharge to home or an assisted facility. Nurses who promote and encourage mobility and movement play a significant role in the client’s healthcare experience. This important contribution can have a lasting impact on the client’s recovery and rehabilitation and benefit society with its positive outcomes.

I found as I was getting older that I wasn’t as flexible as I used to be. My joints were seizing up and I decided to take positive action to prevent loss of function. Keeping active with swimming and cycling allows me to keep moving without putting pressure on painful joints. I haven’t felt this good in years.

THE PHYSIOLOGY OF MOVEMENT

The skeletal system

The skeletal system is the internal framework that supports, shapes, protects and moves the human body. The bones that form the skeleton serve many functions. These functions include support of body shape, protection of organs, movement, storage of fat and minerals and haematopoiesis or blood cell formation in bone marrow. To understand the importance of the skeletal system, imagine performing a task such as running or throwing. If the bones required in this movement are disabled due to damage or pain, this activity becomes more challenging, if not impossible, to perform (Patton & Thibodeau 2010).

The muscular system

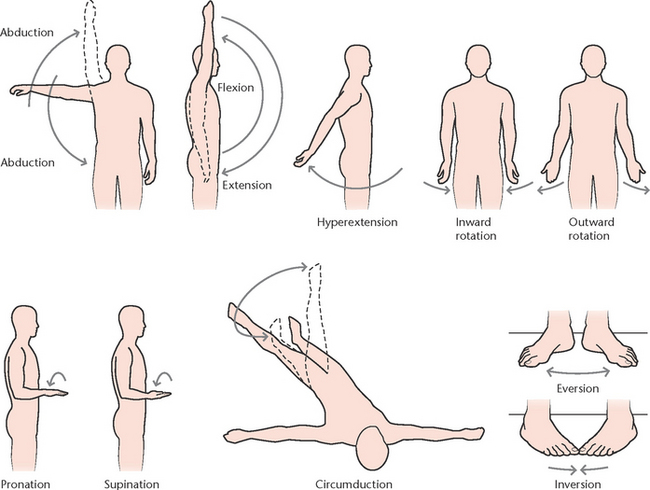

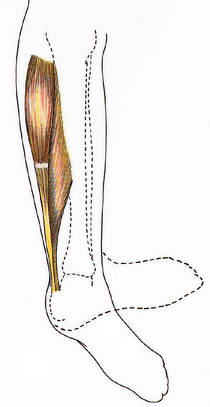

The muscular system enables body movement, joint stabilisation and maintenance of posture. The function of muscle is to contract or shorten (see Clinical Interest Box 26.1). Skeletal muscle attaches to bone and can rapidly contract to exert great power or fine movement under voluntary control. Muscles are supported by a network of connective tissue and tendons that anchor muscle to bone for strength and support. Skeletal muscle is classified by the kind of movement it makes; for example, flexors allow joints to bend or flex, while abductors allow shortening so that joints are straightened or abducted (moved away from the body). When muscle contracts it pulls on a bone or bones and produces movement at a joint, where two bones meet. As joints are weak points in the skeleton, synovial fluid, cartilage, ligaments and tendons add protection and support (Patton & Thibodeau 2010).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 26.1 Muscle coordination

The muscular system plays a vital role in maintaining correct body posture by means of good muscle tone and coordinated activity. Most skeletal muscles work in pairs or groups, with one pair or group antagonising the action of another pair or group to achieve controlled movement. For example, during elbow flexion, the triceps muscle relaxes to allow the forearm to be pulled up when the biceps muscle contracts. Extension of the arm is made possible by the relaxation of the biceps, as the triceps contracts and pulls on the arm. The erect position of the trunk is maintained as a result of coordination of groups of muscles (Marieb 2009; Patton & Thibodeau 2010).

The nervous system

Muscle movements occur as a result of stimulation by a motor or efferent nerve. These nerves activate muscles to respond to voluntary signals, such as grasping an object or towel drying hair. Muscle can respond to voluntary control, those movements controlled by human thought, or to involuntary control through the autonomic nervous system (Marieb 2009). Transmission of the impulse from the nervous system to the musculoskeletal system requires a chemical transmitter to cross the myoneural junction. Acetylcholine transfers the electric impulse from the nerve to the muscle to stimulate muscle and initiate movement (Crisp & Taylor 2009). An imbalance in this chemical neurotransmitter can result in impeded nerve transfer which delays the potential for coordinated or rapid musculoskeletal response.

The codependent relationship between the skeletal, muscle and nervous system in body movement can be demonstrated in a client with a spinal cord injury. A lesion in the spinal cord inhibits nerve transmission beyond the point of injury. With no nerve impulse to contract or react, muscle lays dormant. While still providing shape and connection with the underlying bones, the posture cannot be supported and the bones are unable to mobilise due to absence of muscle contraction and voluntary stimulation (Marieb 2009).

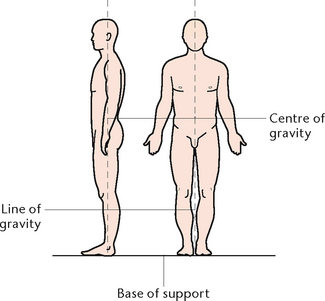

BODY MECHANICS

Fatigue, muscle strain and injury can result from improper use or positioning of the body during activity or rest. Good posture is achieved when all parts of the body are in correct alignment when sitting, lying, standing or moving. Normal spinal curves should be maintained and the joints should be supported in their normal positions. Good posture and alignment reduces strain on all muscles and enables internal organs to function without interference (Fig 26.1). Body mechanics is the term used to describe the physical coordination of all parts of the body to promote correct posture and balanced effective movement. The practice of correct body mechanics results in less fatigue and reduces the risk of muscle and joint injury (Marieb 2009).

Protection of the musculoskeletal system is essential to ensure continuing ability to undertake activities of daily living (ADLs). Everyday activities including walking, showering, cooking and employment are dependent on a functioning and healthy body support system. Nurses in their own activities and during client instruction must familiarise themselves with the mechanics of movement to protect themselves and assist their client in movement and recovery.

A national health survey of Australians (ABS 2009) revealed that 14% of adult respondents reported long-term medical conditions of back pain and disc disorders. Backache may be a symptom of various health conditions, yet up to 80% of cases result from weak muscles in the abdominal, back and hip regions. These muscles reinforce spinal posture and weakened or damaged muscles through inactivity or poor lifting techniques can result in pain, discomfort and even disability. To maintain a healthy back for optimal posture and mobility, weight control, daily exercise and correct alignment should be practised (Marieb 2009). (See Box 26.1.)

Box 26.1 Protecting the back through correct body alignment

1. Weight management. A protruding abdomen pulls the body forwards, forcing back muscles to counterbalance the weight through strong contractions

2. Wear high heels infrequently. High-heeled shoes change spinal alignment, pushing the pelvis forwards and increasing stress on abdominal and back muscles

3. Practise and maintain a good posture with your head and back aligned

4. Lift heavy objects using correct body mechanics

Principle: Every object has a centre of gravity around which weight is evenly distributed. In humans, it is in the pelvis. The principle states that the broader the base of support, and the lower the centre of gravity, the more stable the person will be.

Application to lifting: take a wider stance with feet slightly apart. Bend the knees to lower the centre of gravity. Weight is transmitted through the legs instead of the back during bending and lifting.

5. Face the direction of movement to prevent abnormal twisting of the spine

6. Use techniques of leverage, rolling, turning or pivoting to eliminate the need for lifting

7. Alternate periods of rest and activity to reduce fatigue

8. Avoid sitting for prolonged periods to reduce stress on the spine

9. Stretch for 10 minutes a day to strengthen abdomen, stretch the lower back, extensor and hip flexor muscles

(Adapted from Marieb 2009)

DISEASE PROCESSES THAT INFLUENCE BODY MECHANICS

Diseases of the bones and skeletal system

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a condition in which the amount of bone tissue is reduced because the rate of bone deposition lags behind the rate of resorption. It may be progressive, temporary or permanent. Cancellous bone is usually affected before compact bone. Osteoporosis may be localised or occur throughout the skeleton. Bones are brittle and susceptible to fracture. The factors that contribute to excessive bone loss include diminished oestrogen levels, immobility, lack of exercise, nutritional deficiencies and certain endocrine disorders. Manifestations include low back pain, kyphosis (rounded back) and spontaneous or pathological fractures from minor injuries (Christensen & Kockrow 2010).

Osteomalacia

Osteomalacia is a metabolic disease of inadequate or delayed bone mineralisation. This results in bones becoming soft, bowed and prone to fractures. Paget’s disease is found in people over 40 years of age. The disease is of unknown origin and characterised by hyperactivity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts with rapid turnover of bone tissue. Bones are soft, thick and enlarged and may ‘bow’. Usually the pelvis, long bones, lumbar vertebrae and skull are affected.

Tumours

Tumours of the bone may be benign, primary malignant or metastatic. Benign tumours may be single or multiple, or of several types. The most common benign form is giant-cell tumour, which is composed of multinucleate giant cells or osteoclasts. Clients complain of pain and tenderness, with localised swelling. Osteogenic sarcoma is the most common primary malignant bone tumour. The areas most often affected are the ends of long bones, especially the distal femur or proximal tibia, and metastases may occur most commonly in the lungs. Bone tumours are characterised by the gradual onset of pain in a limb, or the sudden onset of pain after a minor injury to the limb, with a localised mass, swelling and limp in weight-bearing limbs. Fatigue is a common symptom. Metastatic bone tumours occur when cells of a malignant primary tumour in another part of the body enter the blood or lymph and are spread to the bone (Christensen & Kockrow 2010).

Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis is an acute or chronic infection involving bone, bone marrow and surrounding soft tissues. Acute osteomyelitis is characterised by rapid onset of severe pain in the involved bone, with local heat, swelling and inflammation as well as pyrexia, tachycardia, nausea and malaise. Chronic osteomyelitis is characterised by slight pyrexia, pain and persistent drainage of purulent material from a sinus tract injury (Christensen & Kockrow 2010; Marieb 2009).

Disorders of the joints and tendons

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic disease characterised by chronic inflammation of the synovial joint linings, with periods of remission and exacerbation. Joints most commonly affected are those of the wrists, hands and feet. Rheumatoid arthritis results in muscle atrophy and osteoporosis. Signs and symptoms include swelling and stiffness of the joints, followed by marked deformities resulting from soft tissue weakness and joint destruction (Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

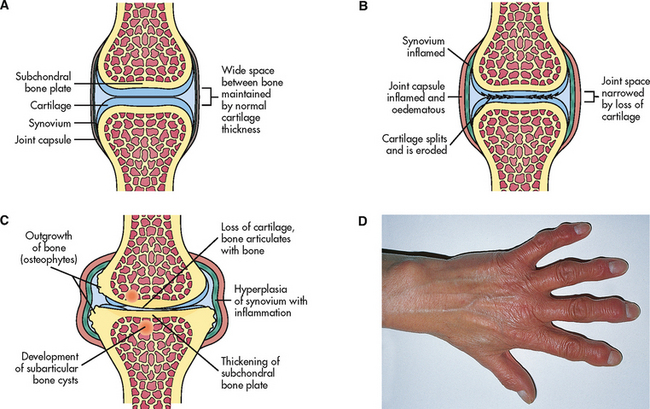

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is a degenerative non-infectious disease that causes pain and restricted movement of affected joints (Fig 26.2). Cartilage in the joints becomes thinner and eventually the two bones come into contact and begin to degenerate, followed by inflammation and effusion. Thought to be caused by excessive use, it usually develops in late middle age and affects large weight-bearing joints (hips, knees and cervical and lower lumbar spine) (Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Figure 26.2 Pathological changes in osteoarthritis A: Normal synovial joint. B: An early change in osteoarthritis is destruction of articular cartilage and narrowing of the joint space. There is inflammation and thickening of the joint capsule and synovium. C: With time, there is thickening of subarticular bone caused by constant friction of the two bone surfaces. Osteophytes form around the periphery of the joint by irregular overgrowths of bone. D: In osteoarthritis of the hands, osteophytes on the distal interphalangeal joints of the fingers are termed Heberden’s nodes and appear as small nodules

(Stevens A, Lowe J, Scott I, Core Pathology, 3rd edition, Edinburgh. Mosby, 2008)

Gout

Gout is a condition characterised by joint inflammation due to deposits of sodium urate crystals in joints and tendons. Causes include a metabolic defect responsible for increased serum uric acid production and impaired excretion of uric acid by kidneys. Use of alcohol and diuretics may precipitate attacks. The large toe is commonly affected and becomes tender, inflamed and very painful. It occurs in males more often than females (Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Diseases of the muscles

Myasthenia gravis

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disease of unknown origin. Defective muscle stimulation is caused by the development of antibodies that damage receptors in the neuromuscular junction, blocking impulses to muscle fibres. Progressive and extensive muscle weakness occurs, with the eyelids affected first, followed by the neck and limb muscles. Remissions and relapses are precipitated by exercise, infections, emotional disturbances and pregnancy (Crisp & Taylor 2009; Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Muscular dystrophies

Progressive muscular dystrophies are an inherited group of diseases in which there is progressive degeneration of groups of muscles. The major differences between these types of conditions are age of onset, rate of progression and groups of muscles involved. For example, the Duchenne type is gender-linked and presents at about five (5) years of age, while myotonic dystrophy usually begins in adulthood. Both progress without remission, and death occurs from respiratory failure or cardiac disease (Crisp & Taylor 2009; Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Diseases of the nervous system

Multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease are progressive neurological disorders that affect neurotransmission along motor pathways. With varying aetiology and signs and symptoms, these diseases affect voluntary and involuntary muscle groups and have long-term effects on gait, mobility and ability to independently undertake and complete activities of daily living (Christensen & Kockrow 2011; Crisp & Taylor 2009; Marieb 2009).

DEVELOPMENT OF MOVEMENT AND EXERCISE THROUGH THE LIFE SPAN

The provision of holistic care must consider individuals within the context of their life and development. A well-structured nursing care plan will incorporate growth and developmental changes, family and social support and cultural, spiritual and ethnic influences that give the client life, meaning and purpose (Crisp & Taylor 2009). To achieve this goal, nurses gather subjective and objective data. Care is planned and implemented based on identified nursing diagnoses and development of goals that can be measured, achievable and relevant to human stages of development.

The body changes throughout the life span (see Table 26.1). Nurses encounter people in all stages and are in a perfect position to promote health and wellbeing to assist optimal performance, regardless of an individual’s age, ability or co-existing medical conditions. The role of exercise in health and wellbeing has been found to have benefits for both people and society and should be practised by all. Yet resistance to movement and physical exertion is a well-documented phenomenon and has been proven to contribute to the development of diseases such as hypertension, diabetes and osteoporosis.

Table 26.1 Stages of development

| Infant | Flexible musculoskeletal system that matures to allow for movement from rolling to crawling and standing when lumbar spine matures |

| Toddler | Swayback and protruding abdomen gives awkward appearance as legs and feet are splayed apart for balance when walking |

| Preschool to adolescent | Greater coordination, skeletal growth and improved balance continue to adolescence when periods of rapid growth, sexual organ maturation and muscle development predominate |

| Adult | Period of greatest strength, coordination and muscle/posture changes related to pregnancy |

| Older adult | Bone density reduction related to inactivity, hormonal changes and bone tissue absorption result in weakening skeletal system with risk of fracture, injury and falls |

A child’s behaviour is modelled on that of their caregiver. Children learn the value of regular exercise if they are raised in an environment in which exercise is seen as a positive experience for the family to enjoy. If exercise is incorporated into their daily routine, these children are more likely to continue to exercise through adulthood and into old age (Fig 26.3). On the other hand, sedentary parents/carers may send the message to their children that exercise is unpleasant and a ‘chore’. If children incorporate these values into their adult lives, they may develop negative familial attitudes towards exercise and form lifetime patterns of unhealthy, inactive behaviour that is then transmitted to their own children (Berk 2009).

The role of schools in keeping children active is important as indoor activities at home lead to increased rates of childhood inactivity and obesity. While parents have to take responsibility for the attitudes and values they impart, the school community can implement physical education programs to meet the shortfall and keep children active. In addition to promoting physical fitness, school health programs can enhance self-esteem and encourage team work, participation and co-operation in a safe and supportive social environment (Berk 2009).

The challenge to keep children active into adulthood may be lost post-secondary school as a downward trend towards inactivity occurs (Crisp & Taylor 2009). While community and government initiatives support increased activity, the stresses of work, family, money and time constraints can sometimes make participation a challenge. The World Health Organization (WHO 2011) suggests that between 60% and 85% of adults lead partial or complete sedentary lifestyles and this inactivity can be attributed to death in 10% of the global population.

The findings of the National Health Survey published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (2009) indicated that as age progressed, exercise level regressed. Sedentary or low levels of exercise were more common in women and were above 70% for age groups of 15 years and above. The highest was in the 75 years and over who reported 83% were sedentary or had low levels of exercise. These findings demonstrate Australians need to increase their activity and movement levels. Not only because of the immediate benefits, but because of the associated health issues that sedentary behaviour intensifies. Healthy eating is more common in those who exercise. Half of those with low exercise levels ate less than the recommended fruit and vegetable intake per day. More were found to smoke and drink alcohol than their exercising counterparts. Inactivity is estimated to increase death rate and the chance of weight-related diseases including breast cancer, colon cancer, diabetes and heart disease (ABS 2009). By comparison, New Zealand respondents to national surveys revealed that older Māori reported lower sedentary rates and greater physical activity involvement than their non-Māori counterparts (Māori Health 2010).

OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY IN AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND

The National Health Survey (NHS) released disturbing statistics on Australia’s expanding waistline. Up to 61% of Australian residents are either overweight or obese, posing a challenging problem about how to tackle this rising statistic. Overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health (WHO 2011). Comparison with data from the 1995 National Nutrition Survey (ABS 1997) shows that the percentage of persons 18 years and over who are classified as overweight or obese has increased. The male population increased from 64% in 1995 to 68% in 2008. The increase for women was from 49% to 55%. The highest rate of obesity was in the 65–74-year-old age group. Of this category, 75% of those surveyed were classed as overweight or obese (ABS 2009). Similarly, the New Zealand Adult Nutrition Survey (2008–09) found that 37% of adults were overweight and 27% were obese (Ministry of Health 2011a). The 2006/07 New Zealand Health Survey found that 21% of children were overweight (Ministry of Health 2011b).

Childhood obesity is of particular concern because the evidence shows that one in three obese children will become obese adults, increasing their vulnerability to weight-related diseases. Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents is generally caused by lack of physical activity, unhealthy eating patterns, or a combination of the two, with genetics and lifestyle both important determinants of a child’s weight. Nurses need to be aware that inactivity is a health risk and that obesity is a serious health risk, not just a cosmetic issue (Kozier et al 2010). The 2006/07 New Zealand Health Survey found that one in twelve children (8%) were obese (Ministry of Health 2011b). Clinical Interest Box 26.2 provides an outline of some self-care behaviours and exercises.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 26.2 Self-care behaviours and exercise

• Make the most of opportunities for exercise—use stairs, park a kilometre away from work or walk to work once or twice a week, walk faster and use lunchtimes for exercise

• Choose an enjoyable physical activity

• Plan 3–4 exercise activities per week

• Before starting exercise sessions, ensure medical clearance if in a high-risk group

• Alternate different types of exercise to keep interest up; for example, Pilates followed by weight-training sessions then walking or bike riding

Fit versus fat

Obesity and fitness may be considered polar opposites, yet studies reveal that an overweight person can still be physically fit and outlive or outperform their slim peers who live a sedentary lifestyle. Studies performed by Blair and colleagues (ABC Radio National 2007) indicated that those with a body mass index of 30–39.9 (Class 1–2 obesity) who were physically active did not have elevated death rates compared with fit people of normal weight. Additionally, in follow-up 10–12 years later, normal weight unfit people were twice as likely to die compared with obese people who were fit. This study does not promote obesity, but challenges practitioners to look at the complete health profile when determining physical fitness (ABC Radio National 2007).

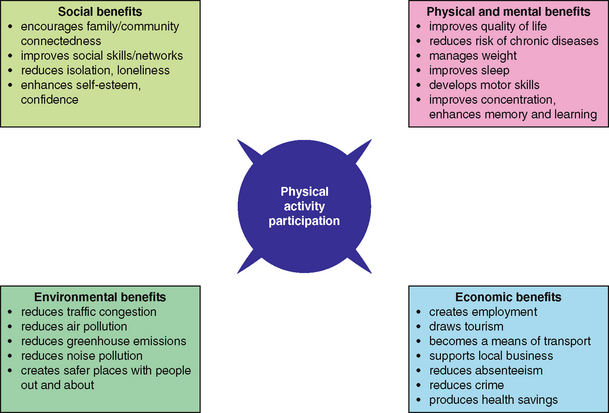

THE BENEFITS OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Participation in regular exercise can enhance the life of individuals, families, community groups and society (Fig 26.4). With 3 × 10-minute blocks of moderate intensity walking a day, immediate and dramatic health benefits can be seen. Exercise will improve fasting plasma glucose levels, reduce triglycerides, reduce blood pressure and enhance joint mobility. Some believe it may help control systemic inflammation and impact the blood clotting mechanism. In older people, exercise can improve cardiorespiratory function and muscular fitness to maintain mobility and promote independence. With commitment to exercise, fitness improves over time and the accumulated effect over an extended period can demonstrate great improvement in body functions, particularly in those with chronic illnesses (ABC Radio National 2007).

Figure 26.4 Benefits of physical activity

(Reproduced by permission of Queensland Health 2009, http://www.health.qld.gov.au/npag/benefits.asp)

Exercise and the older adult

As humans age, body systems deteriorate. Research suggests that up to half of the functional decline associated with ageing is the result of disuse and can be reversed with exercise. Exercise improves cardiopulmonary fitness, strength, coordination, mental health, motor control and cognitive function. Improved flexibility, balance and muscle tone can help prevent falls.

The benefits of physical activity can be enjoyed even if regular practice starts late in life (Fig 26.5). Physical activity improves self-confidence and self-sufficiency to enhance psychological wellbeing. Active lifestyles provide occasions to establish new friendships, maintain social networks and interact with people of all ages. Walking, swimming, stretching, dancing, gardening, hiking and cycling are excellent activities for older persons. With the number of people over 60 years of age projected to double in the next 20 years, reducing and postponing age-related disability is an essential public health measure that must be initiated now (WHO 2011).

A study by Melov et al (2007) demonstrates the benefits of exercise for older adults. An analysis of tissue samples was taken before and after completion of 6 months of twice-weekly resistance training. Findings revealed a reversal in the genetic profile of cells back to levels similar to those in younger adults, indicating a potential reversal of the ageing process. Additionally, muscle strength measured indicated a 50% improvement in older adults after exercise. This improvement was seen 4 months later in the same adults. Using soup cans and elastic bands, these adults maintained informal resistance training in the home. Despite reduced intensity, those studied remained strong as they still had the same muscle mass developed during the intensive 6-month period (Science Daily 2007).

Exercise attitudes within Indigenous communities

Identified health issues within the Indigenous communities of Australia include hypertension, stroke, diabetes, smoking, obesity and alcohol abuse. High levels of sedentary behaviour were reported in the 15 years and above age group, which accounts for 75% of the Indigenous population in non-remote areas of Australia (ABS 2010). Of those who exercised, the prevalence of arthritis, diabetes, heart and vascular diseases was significantly reduced. Similarly, those who regularly exercised at moderate levels reported good self-assessment of their general health and smoked less than their sedentary counterparts (ABS 2010).

Health concerns among Indigenous New Zealand communities are similar to those of Australian Indigenous communities. Smoking, obesity, poor eating habits and inactivity are identified health issues that lead to long-term chronic health issues such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heart disease and stroke (Māori Health 2011).

Finding exercise to suit the individual

Like any activity that humans undertake, exercise must be enjoyable or rewarding if commitment is to be assured. While some are motivated by weight loss or muscle definition, others may be encouraged by improvement in mood, freedom of movement or cardiovascular fitness.

The ideal combination for physical health is a combination of aerobic, flexibility and resistance exercise. Incorporating a daily aerobic walk with resistance exercises that use body weight against gravity (push-ups, weights) are activities that can be done outdoors. For flexibility, combine these with stretching that works the muscle groups that have problems with flexibility, that is, shoulder and chest, hip and knees, back, hamstrings and gluteals (ABC Health & Wellbeing 2007).

Movement and exercise should form part of any treatment program for individuals with neurological disorders. While the exact mechanism of effectiveness is unclear, the benefits can be demonstrated in those suffering symptoms of stroke or Parkinson’s disease. Chen (cited in Fallik 2007) believes voluntary exercise initiated at the right time post stroke can aid rewiring and healing through a ‘use it or lose it’ factor. Repetitive dance steps can help create a pathway to movement in clients with bradykinesia. Dancing uses all muscle groups and creates a sense of achievement and enjoyment. Additionally, Parkinson’s clients who sometimes ‘freeze’ during movement found the beat of the music reduced freezing and enhanced mobility and balance (Fallik 2007).

Barriers to exercise in the elderly were studied by Guerin et al (2008). Many Australian aged care facilities offer in-house exercise programs based on the Easy Moves for Active Ageing program. This chair-based program aims to maintain function and prevent physical decline in older adults by working through a low-impact series of ROM movements. While the benefits of exercise have been discussed, this study revealed factors that can cause resistance in older adults (see Box 26.2). Many residents find these sessions enjoyable, social and empowering; others may experience barriers that inhibit their participation.

Box 26.2 Barriers to chair-based exercises

Barriers to chair-based exercises in a low-level care facility:

PRINCIPLES OF MUSCLE MOVEMENT IN EXERCISE

Isotonic exercise

Isotonic exercise involves muscle shortening and active contraction and relaxation of muscles. Isotonic activity occurs with movement, such as carrying out activities of daily living, independent range-of-movement (ROM) flexing exercises, swimming, walking, running, cycling or jogging.

Isometric exercise

Isometric exercise involves muscle contraction without shortening of the muscle length. These exercises build muscle bulk and are a popular muscle activity for body builders, for example, lifting weights.

Isokinetic exercise

Isokinetic exercise causes muscle contraction, shortening and relaxation at an even speed. Isokinetic movement occurs during swimming as arms move evenly through water resistance (Marieb 2009).

Encouraging maintenance and restoration of muscle strength

As communities become increasingly sedentary, the cost is reflected in the calibre of clients in the healthcare system. With increasing numbers of cases of osteoporosis and arthritis requiring in-hospital care, nurses may frequently find themselves caring for immobilised or physically disabled clients. To aid return to mobility after the acute care phase, provision of movement activities is essential to prevent long-term complications sustained during immobility. Until this stage, nurses should undertake muscle and joint movement. Using the principles of muscle movement, a range of exercises can be incorporated into everyday situations to enhance client health and recovery (Crisp & Taylor 2009):

• Isotonic bed exercises: pushing or pulling against a stationary object, using a trapeze to lift the body off the bed, lifting the buttocks off the bed by pushing with the hands against the mattress and pushing the body to a sitting position (Crisp & Taylor 2009)

• Isometric bed exercises: Benefits of isotonic and isometric exercise include increase in muscle tone, mass and strength, improved joint mobility, increased circulation and osteoblastic activity. Examples may include: Lifting of hand weights and gripping of tennis ball to aid arm strength and mobility. Quadriceps extension: push knee into mattress while attempting to lift heel off bed to strengthen thigh muscles (Crisp & Taylor 2009)

• Isokinetic bed exercises: for example, rehabilitative exercises for knee and elbow injuries. In this case, isokinetic devices are used to take muscles and joints through a complete ROM without stopping, with resistance at each point. Mechanical devices are available for specific joints, which place these joints through continuous passive ROM (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Encouraging maintenance of joint mobility

Joints are capable of a wide range of movement (Fig 26.6). ROM or motion exercises are either active, when the clients are able to move the joints themselves, or passive, when the nurse moves clients’ joints within the normal ROM, noting joint flexibility and/or limitations of movement. Joints that are not moved regularly can develop contractures (shortening of a muscle and eventually ligaments and tendons and eventual loss of function). It must be remembered that when a nurse performs passive ROM exercises in which the client’s muscles do not exert effort, some of the potential benefits are reduced in favour of improved joint mobility and circulation (Christensen & Kockrow 2010; Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

The frequency with which ROM exercises are performed depends on the client’s condition and medical and nursing management, but they are commonly performed at least twice daily. However, it is important not to overtire the client. ROM exercises may be performed independently or with assistance. Using appropriate movements, all joints are exercised in a logical sequence. Exercise routines are normally individually designed and the intensity and frequency depend upon the client’s general condition, level of fitness and capabilities (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

ASSESSMENT OF MOVEMENT, MOBILITY AND THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

Undertaking a systematic client assessment will identify issues of movement and mobility. After prioritising care by applying first aid and pain management measures prior to examination, the nurse should obtain a musculoskeletal medical history that includes:

• Activity and exercise level prior to hospital presentation

• Past history of muscle and joint pain or injury

• Current treatment for existing muscle and joint pain or injury, including medications, physiotherapy, osteopathy, chiropractic or other complementary therapies

• Presenting problem including details of injury, cause of injury, symptoms, duration and treatment received (if hospital presentation is due to a musculoskeletal condition)

• Recent changes in mobility or movement unrelated to current hospital presentation

On completion of verbal data collection, a physical examination should be undertaken to provide a baseline for ongoing assessment and completion of a management or care plan. Identifying current and potential movement and mobility issues will tailor treatment needs and identify potential discharge issues. A physical assessment will incorporate observation of gait and posture, pain and nerve changes, limb deformities, neurovascular assessment and spinal conditions including congenital and acquired pain or abnormalities (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Gait

Gait describes the manner of walking and, while varying from one person to another, there is normally a certain rhythm to a person’s walk. Gait abnormalities may occur when there is a disorder of the musculoskeletal or nervous system; for example, unilateral hip dislocation produces a distinct ‘waddle’ with each step. A staggering, or ataxic, gait may be caused by a lesion in the brain or spinal cord, and a ‘scissors’ gait is one in which the legs cross each other in progression. An abnormal gait may also result from pain or discomfort due to a lesion on the foot, such as a corn, or from ill-fitting and uncomfortable shoes (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Pain and nerve (sensory) changes

Pain is a common symptom of musculoskeletal disorders, as a result of trauma, inflammation or degeneration. Clients describe the pain as mild, aching, severe or throbbing, and it may be localised or generalised, depending on the specific disorder. Pain may increase with movement, be exacerbated by changes in external temperature and relieved by rest. It may be worse at certain times; for example, joint discomfort from degenerative disease is often worse in the evenings. Numbness, tingling and lack of sensation are other sensory changes. Swelling from injury or tumours may cause pressure on nerves, resulting in loss of sensation (Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Swelling, deformity and impaired mobility

Swelling of an affected area may be the result of the formation of inflammatory exudate in response to injury from physical trauma, chemicals or infection. Swelling will also occur when blood is lost from the circulation into surrounding tissues (haematoma); for example, after a fracture. A joint may become swollen if there is an increase in the amount of synovial fluid or if blood or purulent discharge is present in the joint capsule. Deformity may be the result of growths, fractures, dislocations, abnormal curvature of the spine or contractures. The effects of a deformity include changes in range of joint motion, posture and gait. Mobility may be impaired to such an extent that the client is unable to move without pain or unable to carry out activities of daily living, or it may only restrict mobility at certain times, such as after activity or be related to certain positions (Fig 26.7).

Sprains

A sprain is an injury to a ligament, caused when a joint is forced beyond its normal ROM. A ligament may be stretched or torn and local bleeding and bruising present with restricted movement. Sprains commonly occur in the wrist and ankle. Treatment is aimed at resting and supporting the area and reducing pain and inflammation with anti-inflammatory medications (Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Strains

A strain is an injury to a muscle and/or a tendon, resulting from excessive physical effort. Both sprains and strains cause pain and swelling, but strains may cause muscle spasm as well. Nurses can suffer strain injuries from incorrect manual handling techniques (Crisp & Taylor 2009; Christensen & Kockrow 2010).

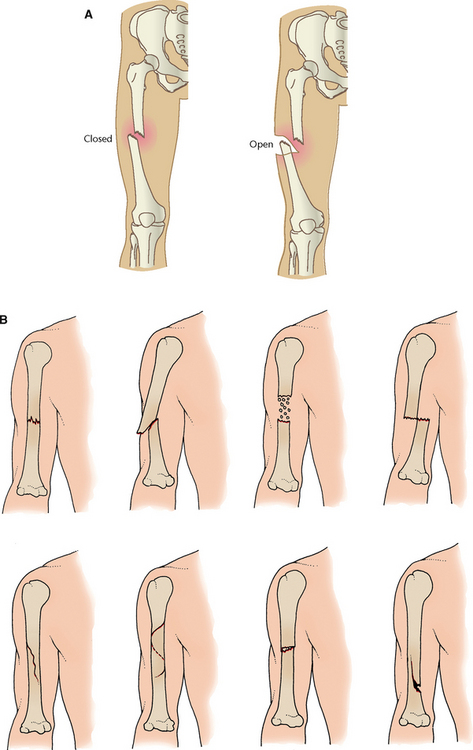

Fractures

A fracture is a broken bone, often with nearby soft tissue, blood vessel and nerve damage. A stress fracture occurs when a bone is subjected to repeated or prolonged stress such as jogging. A pathological fracture may occur in weakened bone as a result of osteoporosis. Fractures are classified as open or closed, simple or complicated. Open (or compound) fractures are those in which the bone breaks through the skin, while closed fractures are those where the skin is intact. In a simple fracture only the bone is involved, while in complicated fractures nearby blood vessels, nerves or organs are affected. Table 26.2 and Figure 26.8 demonstrate and describe the various types of fractures. Signs and symptoms vary but usually encompass pain, swelling, muscle spasm, bruising, deformity, abnormal mobility and loss of function. Crepitus (grating caused by bone fragments rubbing together) may be heard on examination or experienced and described by the client. Shock may occur as a result of haemorrhage or extensive damage (Farrell & Dempsey 2011; Patton & Thibodeau 2009).

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Greenstick | The fracture is incomplete and does not extend through the bone. The bone bends, and splits or cracks on one side |

| Transverse | The fracture line is straight across the bone |

| Oblique | The fracture line is at an angle across the bone |

| Spiral | The fracture line coils around the bone. This type of fracture generally results from twisting of the limb |

| Impacted | The fragments of broken bone are pushed (telescoped) into each other |

| Comminuted | The bone is broken into a number of fragments |

| Depressed | The broken edges are pushed below the level of the rest of the bone. This type of injury may occur when the skull is fractured |

| Avulsion | A fragment of bone, connected to a ligament, breaks off from the rest of the bone |

| Intracapsular | The fracture is within the joint capsule |

| Extracapsular | The fracture is close to a joint, but is outside the joint capsule |

Adapted from Crisp & Taylor 2009; Marieb 2009; Patton & Thibodeau 2010

Figure 26.8 A: Closed and open fracture B: Common types of fractures

(A Figure 4.22 from Christensen B L, Krokow E O (2011). Adult Health Nursing, 6th edn. Mosby, Elsevier: St Louis, pp 142–143, modified from the original in Thibodeau, G A & Patton K T (2005). The Human Body in Health and Disease, 4th edn. St Louis, Mosby; B Figure 4.23 from Christensen B L, Krokow E O (2011). Adult Health Nursing, 6th edn. Mosby, Elsevier: St Louis, pp 142–143, modified from the original in Ignatavicius D D & Workman M L (2009). Medical-surgical nursing across the healthcare continuum, 6th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders)

Neurovascular assessment

A neurovascular assessment is performed on clients who have experienced a fracture, who have been fitted with a cast, have undertaken vascular surgery or have had spinal surgery. Neurovascular protocols vary depending on the client diagnosis and treatment undertaken. Nurses should familiarise themselves with neurovascular guidelines within their place of work and employment facility. For example, a client with a fracture should have neurovascular observations undertaken every hour for 24 hours, then every 4–8 hours if fitted with a cast (Berman et al 2012; Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Assessment must be undertaken by the primary care nurse at the commencement and throughout the shift to identify early changes that can indicate a pathological deterioration. Inability to recognise significant changes in a timely manner may influence a client’s potential for recovery and rehabilitation. A neurovascular assessment might include inspection of:

• Skin: inspect area distal to the injury; palpate skin temperature with the back of the hand and compare with the opposite extremity or site

• Movement: have the client move the area distal to the injury, or move it passively; there should be no discomfort

• Sensation: enquire about feelings of numbness or tingling; check sensation with a paper clip and compare bilaterally—sensation should be the same

• Pulses: palpate pulses distal to the injury; compare bilaterally

• Capillary refill: check this in the nail beds distal to the injury. Capillary refill should occur within 3 seconds and within 5 seconds in the older adult

• Pain: enquire about the degree, location, nature and frequency of pain, noting any increase in intensity or change in the type of pain (deWit 2009).

Dislocation

Dislocation is complete displacement and subluxation to partial displacement of a joint’s articulating surfaces; both processes damage surrounding soft tissue structures. Joint effusion is the accumulation of synovial fluid in a joint and occurs if blood vessels in the synovium are damaged. Joint effusions may result from severe sprains, dislocations or fractures. Signs and symptoms of dislocation and effusion include severe pain, limited movement, joint deformity and swelling. Dislocations may affect fingers, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees and ankles and are often caused by sporting injuries or pressure on the affected area after a fall (Marieb 2009).

Lower back pain

Lower back pain is a common symptom that has a variety of causes, including poor posture, injury, inflammatory conditions, obesity, metabolic bone disorders, degenerative processes and intervertebral disc disease. Discomfort or pain may be mild, severe, continuous or intermittent and be aggravated by certain movements or posture; it may radiate into the buttocks or down the back of the legs. People with lower back pain should not sit for more than 30 minutes at any one time, and frequent stretching (thrusting the hips forwards while the upper body leans back) is recommended. Most lower back pain can be safely and effectively treated after an examination by an orthopaedic surgeon and a prescribed period of activity modification and medication to relieve the pain and diminish the inflammation. Although a brief period of rest may be helpful, most studies show that light activity speeds healing and recovery. It may not be necessary to discontinue all activities, including work. Instead, people may adjust their activity under the guidance of medical officers or physiotherapists (Marieb 2009).

When the initial pain has eased, a rehabilitation program may be suggested to increase muscle strength in the lower back and abdominal muscles, as well as stretching exercises to increase flexibility. If overweight, weight loss is recommended, as this may decrease the chance of recurrence of lower back pain. The best long-term treatment is an active program of maintaining optimal physical condition. This can be achieved by regular exercise, practising correct lifting techniques and assuming good posture (Crisp & Taylor 2009; Hoeman 2008).

DIAGNOSIS OF A MUSCULOSKELETAL DISORDER

Diagnosis of musculoskeletal disorder will be confirmed by:

• Presenting history of injury, disorder or change in range of movement

• Physical examination including observation, palpation and assessment of joint movement

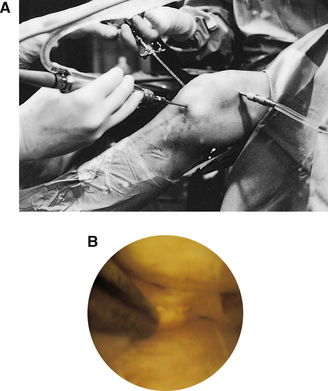

• Radiological examinations including plain x-ray, arthrogram, arthrography, bone scan, arthroscopy, biopsy, ultrasound, MRI and CT scan (Marieb 2009) (see Fig 26.9 and Table 26.3).

Figure 26.9 Arthroscopy of knee. A: Insertion of a fibreoptic light source into joint. B: Internal view of joint

(Courtesy of Lanny L. Johnson, MD, East Lansing, MI. Used with permission)

Table 26.3 Musculoskeletal diagnostic tests

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Plain x-ray | Standard x-ray of bones and joints that detects abnormalities in shape and alignment |

| Arthrogram | Outlines soft tissue (e.g. meniscus) which is not usually visualised on x-ray |

| Arthroscopy | Visual examination of a joint with a fibreoptic endoscope. Commonly performed on the knee to remove loose fragments, view suspected damage or obtain a biopsy |

| Biopsy | May be performed on bone, muscle or synovial membrane. Takes blood and tissue samples to test for tumours, enzymes, antibodies and antigens, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and calcium, phosphorus and uric acid levels |

| Arthrocentesis | Aspiration of synovial fluid for analysis of infection and inflammation |

| Bone scan | Provide imaging of the skeleton after intravenous injection of a radioactive isotope that collects in bone tissue at sites where there is increased activity (i.e. at the site of a tumour) and lesions can be detected earlier. |

| Ultrasound | 2D examination of soft tissue for signs of bleeding, haematoma and fluid collection |

| Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | Magnetism and radiowaves form cross-sections and images to detect pathological abnormalities in soft tissue and blood vessels |

| Computerised axial tomography (CT or cat scan) | 3D cross-sections that provide detail about injuries to ligaments, tendons, tumours and fractures difficult to determine on plain x-ray. May use iodine contrast medium for greater clarity of affected area to be examined |

Adapted from Crisp & Taylor 2009; Marieb 2009; Patton & Thibodeau 2010

NURSING CARE OF THE INDIVIDUAL WITH A MUSCULOSKELETAL DISORDER

While medical management and nursing care will depend on the specific disorder, the general aims of care of an individual with a musculoskeletal disorder are to:

• Promote rest and relieve pain

• Prevent complications of inactivity and promote movement when possible

• Maintain or improve nutritional status

• Prevent and recognise potential psychosocial problems

• Promote rehabilitation (Berman et al 2012; Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Clients with a bone injury

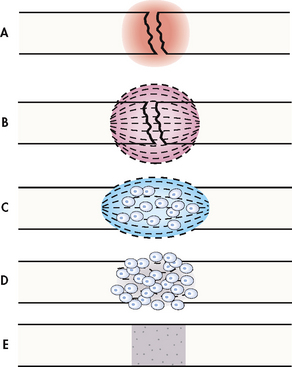

Bone fractures can take weeks or months to heal, and healing occurs in stages:

• Stage 1: The formation of a haematoma between the two ends of the bones

• Stage 2: Inflammation and accumulation of white cells to break down (phagocytose) the haematoma (this takes approximately 5 days)

• Stage 3: The development of granulation tissue and new blood vessels is followed by the development of a callus (calcified osteoblasts) and shaping of new bone by osteoclasts, which remove excess callus (Fig 26.10)

Figure 26.10 Stages in bone healing A: Bleeding at fractured ends of the bone with subsequent haematoma formation. B: Organisation of haematoma into fibrous network. C: Invasion of osteoblasts, lengthening of collagen strands and deposition of calcium. D: Callus formation: new bone is built up as osteoclasts destroy dead bone. E: Remodelling is accomplished as excess callus is reabsorbed and trabecular bone is laid down

(Fig 62-9 from Brown D & Edwards H (2012) Medical–Surgical Nursing: Assessment and management of clinical problems, 3rd edn. Sydney, Mosby. Redrawn from Phipps W, Monahan F, Sands J, Neighbors M, Marek J (2003) Medical-surgical nursing: Health and Illness Perspectives. St Louis: Mosby, with permission.)

Bone healing is individualised. For most, healing takes place within a standardised time frame; however, some healing is delayed and can be influenced by the following factors:

• Fat emboli (from the medullary canal) that lodge in the lungs

• Splinters of dead bone not removed by phagocytosis

• Ischaemia (the neck of the femur is vulnerable, as it has a poor blood supply)

• Continued mobility and client age

• Client nutritional status (Farrell & Dempsey 2011; Marieb 2009).

TREATMENT OF BONE INJURIES AND MUSCULOSKELETAL DISORDERS

Surgical repair

For some bone and joint disorders, surgical repair of the affected area is essential to restore alignment, control pain and enhance rehabilitation for full joint mobility. Simple fractures require return of bone fragments to their original position and may be achieved by surgical review and realignment with an internal or external fixature. Compound fractures require surgical debridement to remove dirt, foreign material and necrotic bone fragments (Christensen & Kockrow 2010; Patton & Thibodeau 2010).

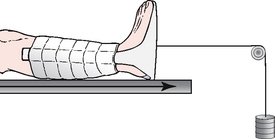

Traction

Traction reduces and immobilises fractures. A steady pull from two directions keeps the bone in place. Traction is also used for muscle spasms, to correct or prevent deformities and to relieve pressure on a nerve. Weights, ropes and pulleys are used to create the pull required to stabilise the limb. Traction can be applied to the neck, arms, legs or pelvis. Skin traction is applied to the skin. Tape, a boot or a splint is used. Weights are attached to the device. Skeletal traction is applied directly to the bone with wires or pins are inserted through the bone. Weights are attached to the device (Fig 26.11).

Casts

Casts are immobilisation devices made of plaster or fibreglass. They are applied after bone alignment by internal or external fixation. Applying the cast can be painful during manipulation for alignment and clients should be advised of the warmth they will experience as the plaster undertakes its setting process. Clients who have had a cast applied must have neurovascular observations performed as per hospital policy. Clients discharged home wearing a cast should have their cast inspected for rough edges and signs of bleeding or drainage. Clients should be educated to seek medical advice if they notice their cast is cracked, moist or emanating an offensive odour. The limb should be kept elevated to reduce swelling and advice sought if the limb becomes cool, swollen, increasingly painful or changes colour. Casts may remain in place for several weeks to some months, depending on the bone or joint requiring immobilisation (Berman et al 2012; deWit 2009; Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

GENERAL TREATMENT OF MUSCULOSKELETAL DISORDERS

Promoting rest

Rest helps minimise pain and swelling, promotes healing of injured tissues, relieves muscle spasms and prevents further tissue destruction in inflammatory conditions. Rest may be classified as general, when the individual is confined to bed (e.g. if several joints are inflamed), or local, when a specific body part is immobilised, such as a limb in a splint or cast. General care during the rest phase involves:

• Providing a suitable bed with a firm mattress, pillows and sheepskins to promote comfort

• Meeting basic needs; that is, helping those who are immobilised with activities of daily living

• Preventing complications associated with immobility

• Maintaining correct posture and body alignment (deWit 2009; Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Maintaining joint movement

Some joints require movement, not immobilisation post repair. The continuous passive movement (CPM) device provides gentle forward and backward joint movement after knee surgery. Used on clients who are resting in bed, the joint is strapped into the device and moved continuously while the client is immobilised. This movement ensures the joint remains mobile, resulting in reduced pain, swelling and eventual immobility (Crisp & Taylor 2009; Hoeman 2008).

Maintaining skin integrity

Clients who are immobilised for prolonged periods are at high risk of developing pressure sores or decubitus ulcers. Skin must be maintained in good condition and protected from irritation, friction and prolonged pressure (Crisp & Taylor 2009). General care of the skin and prevention of pressure sores are described in Chapter 27.

Positioning techniques

Clients with musculoskeletal disorders who are immobilised require help from nurses to ensure proper body alignment and comfort. Aids to comfort in bed, such as pillows, foot boards, trochanter rolls, trapeze bars, sandbags and slippery-type sheets for ease of movement in bed, are all useful to ensure that an immobilised client is comfortable (Crisp & Taylor 2009; Hoeman 2008).

Various positions and proper positioning are discussed in Chapter 21.

Maintaining or improving nutritional status

Nutrition for clients with a musculoskeletal disorder includes a well-balanced diet and maintenance of recommended body weight. The diet should contain adequate amounts of protein, calcium and vitamin D to promote healing and maintenance of the musculoskeletal system. Adequate fibre and fluids aid elimination. If the client is overweight, a weight-reduction diet is recommended to prevent stress on inflamed or diseased joints (Berman et al 2012; Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Relieving pain

While the general approaches to pain management described in Chapter 31 are relevant to clients with musculoskeletal disorders, specific measures may also be indicated. Clients may experience acute or chronic pain, depending on the specific disorder, and general measures to promote comfort and minimise pain should be implemented; that is, changing position, massage, handling a painful limb gently and rest. If not contraindicated, elevating the limb may relieve discomfort and pain. Specific measures include checking to ensure that splints, casts or dressings are not too tight or rubbing against the skin. Hot or cold packs or treatments may be used to provide relief and increase ROM. Heat is sometimes used in chronic joint disorders, as it relaxes muscles, relieves stiffness and provides analgesia, and is often applied before exercise and massage. Applying a cold pack to a limb or area is useful for acute pain or acutely inflamed joints. When these treatments are used, caution is necessary to prevent tissue damage. Analgesia may be prescribed and administered in accordance with nursing regulations and the institution’s policy (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Prevention of psychological problems

Management of a musculoskeletal disorder may require a person to be confined to bed, and possibly hospital, for an extended time, and often leads to boredom, frustration or depression. To prevent such problems, clients are encouraged to express their feelings and are allowed to participate in making decisions about their care. Active involvement in all aspects of care and self-care techniques are taught, as this allows clients to take responsibility for some of their care and can help to reduce problems associated with dependence and immobilisation. Regular programs of activity developed with the client and other allied health professionals need to be incorporated into the nursing care plan (Crisp & Taylor 2009; Farrell & Dempsey 2011; Hoeman 2008).

Promoting remobilisation and rehabilitation

As the musculoskeletal system is crucial to activity, a routine of exercise and rehabilitation is developed and implemented. A planned exercise program is generally developed by the physiotherapist, but the nurse is required to encourage and supervise regular exercise. Programs contain exercises designed to prevent muscle atrophy or joint contracture and to prepare for ambulation. Range-of-movement exercises are important during this time. A program of gradated, non-weight-bearing exercises is started, designed to regain or increase muscle tone, build muscle strength and promote joint mobility. When clients are able to bear weight on the affected limb, the exercise program is aimed at restoring as much mobility as possible (Hoeman 2008).

The overall aim of rehabilitation is independence in activities of living, and requires a multidisciplinary team approach consisting of nurses, medical officers, physiotherapists and occupational therapists. Depending on specific needs, a social worker and splint-maker may be involved. (Information on rehabilitation is provided in Ch 38.) Preparation for discharge includes informing clients of the need to continue any exercise program, on the use of splints or braces, about limits of physical activity and the importance of attending any future appointments or ongoing rehabilitation programs (Hoeman 2008).

Nursing care plan of a client requiring prolonged bed rest

Older clients are more prone to problems associated with prolonged bed rest. These clients need careful planning and enactment of care to minimise these potential problems (see Nursing Care Plan 26.1 and Clinical Scenario Box 26.1).

Nursing care plan 26.1 An immobile client

(Adapted from Crisp & Taylor 2009; Gulanick & Myers 2010; Hoeman 2008)

| Identification of issue: Potential for sacral pressure areas related to bed rest and immobility |

| Goal: Client sacral areas will remain intact and healthy with no signs of redness, pain or injury during the period of immobility |

| Nursing action | Rationale | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Reposition from side-to-side every 2 hours while resting in bed | ||

| Apply air mattress |

General treatment for exercise-related injuries

Exercise can be the cause of injuries that are mostly orthopaedic in nature and caused by irritation of bones, tendons and ligaments and/or muscle tissue. Injury may be as a result of weight-bearing stress or collision. Nurses can teach clients the acronym PRICE: prevention, rest, ice, compression and elevation, and advise of the need for a medical officer to diagnose the injury. Generally, further injury can be avoided by resting the affected limb (Christensen & Kockrow 2010; Hoeman 2008).

Meeting movement and exercise needs

To plan and implement appropriate nursing actions, a client’s ability to mobilise should be assessed. By observation and obtaining factual information, nurses are able to plan and implement measures to meet client movement and exercise needs. When admitting clients, it is important to note whether a client experiences problems that limit independent movement. Nurses observe and document posture and gait, strength and tone, ROM and other factors such as dyspnoea at rest or on exertion, which may limit exercise (Hoeman 2008).

It is important to identify potential problems that may affect a client’s ability to exercise. Impaired mobility may result from:

• A decrease in the individual’s strength

• Presence of pain or discomfort

• Impaired cognition or perception, such as dementia, severe anxiety or depression

Being in hospital is likely to alter a person’s normal movement and exercise routine and, although there is often a degree of restriction in activities, clients able to ambulate should be encouraged to do so, while those who are immobilised may require assistance to move. Nurses promote safety and comfort while encouraging, when possible, a return to independent function (Crisp & Taylor 2009; Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

When planning care to meet a client’s need for movement and exercise the nurse must consider factors such as:

• Maintaining and promoting normal mobility

• Assisting those with restricted mobility

• Providing and assisting with use of equipment to aid mobility

• Preventing and alleviating discomfort associated with reduced mobility.

A sample nursing care plan is shown in Nursing Care Plan 26.2.

Nursing care plan 26.2 A client with a musculoskeletal disorder

(Crisp & Taylor 2009; Farrell & Dempsey 2011; Gulanick & Myers 2010)

| Nursing action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Preparation of environment | Promote an area conducive to rest including pillows for elevation and bed cradle for air circulation around injured limb or newly applied cast |

| Specific equipment acquisition | Ensure availability of equipment that is requested to enhance joint mobility and repair, e.g. CPM machine, traction equipment, plaster, mobility assistance aids |

| Prevention of potential problems related to immobility | |

| Client comfort | |

| Nutrition | Plan diet for optimal healing including proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals and ensuring adequate hydration and caloric needs |

| Allied health referral | Specialist advice for mobility aids, ROM exercises and assistance for posturing and mobilisation to promote independence and rehabilitation |

AMBULATION AFTER PROLONGED IMMOBILISATION

‘Dangling’ before ambulating

Ambulating, or walking, is encouraged and facilitated to prevent the complications associated with even short-term but especially with long periods of immobility. Certain clients may need to relearn how to walk; for example, after a cerebrovascular accident or leg surgery, clients may need the assistance of aids such as a walking stick, crutches or walking frame. After an extended period of immobility, nurses need to instruct clients to mobilise progressively. Bedridden clients who are able to raise each leg 4–6 cm straight up from the bed usually possess enough strength to walk, provided that they are mentally alert.

Clinical Scenario Box 26.2

You have started working in an aged care facility. There is no exercise program for the residents to participate in.

• How will you persuade management of the importance of initiating such a program in the facility?

• With minimum funds available, how could you develop this program? Use Box 26.2 to guide your planning.

Nurses begin re-educating muscle groups by first allowing the client to sit on the edge of the bed for 1–2 minutes with their feet on the floor, a technique called dangling. Clients then progress to standing, then walk a few steps, gradually increasing the distance. Blood pressure can drop dramatically and the client could faint if they were to stand up suddenly. Dangling for a few minutes helps prevent hypotension and dizziness when a previously immobilised client stands for the first time. If a client complains of dizziness or suddenly looks pale when they are standing, quickly return the person to bed or the nearest chair (Hoeman 2008).

When the nurse assists a client who has a one-sided weakness, or hemiplegia, it is important to decide which walking aid or technique has been recommended. Although the method used to assist is individualised, most clients require assistance and support on the affected side. When assisting a person to walk it is helpful if they remain close to a railed wall and are able to rest on a chair before beginning the return walk. If an ambulant client has an intravenous infusion or urinary or wound-drainage bag, the nurse ensures that therapy or drainage is not affected, by checking tubing or drainage bags in case they have become dislodged after exercise.

Well-fitting footwear should always be worn (non-slip soles) and potential hazards eliminated, such as obstacles or liquids on floors. Clients should not be allowed to walk barefoot or with just socks or slippery footwear (e.g. women with nylon hose) on the feet. Clients are encouraged to walk at their own pace and, if they become distressed or complain of pain, faintness, giddiness or undue fatigue, should be seated and the nurse should remain with the client and call for assistance (Hoeman 2008).

WALKING AIDS

Walking aids broaden the base of support and increase stability. The type of aid used depends on the client’s condition, disability and amount of support required. Clients are commonly instructed in the use of walking aids by a physiotherapist; however, it is important for nurses to know the principles involved in the use of walking aids. Walking aids that may be required on a temporary or permanent basis include crutches, walking sticks and walking frames. Callipers, leg braces or splints may be used to provide extra support for a weak leg, to prevent or correct deformities or prevent joint movement.

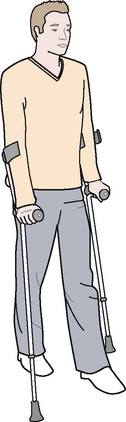

Crutches

Crutches enable a person to ambulate by taking the weight of the body off one or both legs. Successful use of crutches requires balance and upper body strength. Selection of crutches and particular type of gait depends on individual needs, but must be appropriate to be safe and effective. The two types commonly used are the underarm and forearm crutches.

Underarm crutches are often used by clients with a sprain or leg cast, while forearm crutches are more commonly used by those with a through gait, as in paraplegia. Underarm crutches must be measured so that the person’s weight is carried on their wrists and palms and not on the axillae. The axilla bar should be 4–5 cm below the axilla, and the hand bar positioned to permit 15–30 degree flexion of the elbow at rest. Forearm crutches must also allow 15–30 degree flexion of the elbow at rest. Before crutches are used they should be assessed for safety, ensuring that all screws and bolts are tightened and rubber tips are in good repair. It is important to ascertain the amount of weight bearing allowed on the affected leg(s); that is, partial or none (Berman et al 2012; Crisp & Taylor 2009; Farrell & Dempsey 2011) (Figs 26.12 to 26.14).

Crutch-walking gaits

Clients are instructed in one of several crutch-walking gaits, according to need. The most common is the three-point gait, in which weight is borne on the unaffected leg, and the crutches moved forwards first, followed by the unaffected leg, then the affected leg follows in a swinging movement because it is raised from the ground. This gait is used when a person is unable to bear weight on one leg. The two-point and four-point gaits are used when both feet can bear some weight; that is, partial weight bearing. The two-point gait requires the individual to advance one crutch and the opposite leg together, followed by the other crutch and leg. The four-point gait requires greater coordination but provides more stability, as there are always three points on the floor as each leg is moved alternately with the opposite crutch.

The swing-through gait is used when a person has no use of the lower body (i.e. in paraplegia), and both crutches are advanced simultaneously. The person swings both legs either parallel with or beyond the crutches, the pelvis moving first, followed by the shoulders and head in order to maintain balance.

When rising from a chair the individual is taught to hold both crutches in one hand, tips resting firmly on the floor, and to push up with their free hand, using the crutches for support. To sit down, the process is reversed, the person supports themselves with the crutches in one hand, holds the arm of the chair with a free hand and lowers into the chair. To use stairs, the three-point gait is easiest, so that when going up stairs a person leads with the unaffected leg, follows with both crutches then the affected leg. When going down stairs a person leads with the crutches and affected leg, followed by the unaffected leg (Hoeman 2008).

Walking sticks

A walking stick may be used for people with one-sided weakness or injury, occasional loss of balance or to reduce weight bearing on a hip or knee, as well as to provide balance and support for walking, reducing fatigue and strain on weight-bearing joints. Walking sticks should extend from the individual’s greater trochanter to the floor, and be fitted with a rubber tip to prevent slippage. Sticks are available as single-tipped, tripod or four-point, and should permit 15–30 degree flexion of the elbow. Three- and four-point sticks provide a broad base and greater stability and may be used by a client with poor balance or one-sided weakness.

To use a stick the client holds it close to the body on the unaffected side; taking the weight off the affected leg, the client moves the stick and the affected leg simultaneously, followed by the unaffected leg. Sometimes the three- or four-pronged stick is held on the affected side. Clients are encouraged to keep the stride of each leg, and the timing of each step, equal. While a client is learning to use the stick, the nurse stands behind them to support them if they become unsteady. When going up stairs the stick should be held in one hand and clients encouraged to hold the stair rail, leading with the unaffected leg; when going down stairs the affected leg leads (Farrell & Dempsey 2011; Hoeman 2008).

Walking frames

Walking frames consist of a metal frame with hand grips, four legs and one open side (Fig 26.15). A frame may be used by an older adult, as it provides greater support and sense of security than a stick and is useful for those with an unsteady gait, or when partial weight bearing is recommended. The height is selected to allow 15–30 degree flexion of the elbows when the hand grips are held. Attachments such as baskets and trays are available to meet specific needs and to promote greater independence. To safely rise from a chair, the frame is placed in front of the client, who then inches forwards in the seat of the chair and, with both feet firmly on the ground and both hands on the arms of the chair, pushes with their arms to stand and, when standing, grasps the frame. Commonly, the client picks the frame up and moves it 15–20 cm forward, then moves one foot, followed by the other, up to the frame. If a client has a one-sided weakness, the affected leg is moved first (Crisp & Taylor 2009; Hoeman 2008).

When clients are learning to use a frame, the nurse stands behind them to support the hips and encourages the client to stand upright and look straight ahead. To sit down, the person stands with the back of their knees against the front of the chair, then reaches behind to securely grip the armrests, bending their arms to lower themselves into the chair. When a walking aid is used, the person is assisted until they are confident in the use of the aid and when unassisted use is decided by their medical officer, physiotherapist or nurse, in consultation with other health professionals (Hoeman 2008).

COMPLICATIONS ASSOCIATED WITH REDUCED MOBILITY

The body works more efficiently when people are active, so when a client is confined to bed or immobilised, each system is affected in a negative way. Depending on age, health status and length and degree of immobility, inactivity can cause both short- and long-term complications. Disuse of muscles leads to degeneration and subsequent loss of function and it is important that clients receive some form of exercise to prevent muscle atrophy. Atrophy begins almost as soon as muscles are immobilised. Clients also experience a limitation in their endurance, which makes activities of daily living difficult. Restoring muscle strength and tone in clients who have been immobilised for any length of time is a slow process. Systemic effects of immobility include:

Pressure sores and decubitus ulcers

Pressure sores result from localised damage to the skin and underlying tissue caused by pressure, shear or friction (for bedridden clients, shear or amount of friction increases as their head is elevated). Pressure, especially on bony prominences, results in poor circulation, so that the area is deprived of essential nutrients and oxygen, and cellular death may occur. Any client with a mobility or activity deficit should be subject to a pressure-sore risk assessment. Pressure sores remain a significant problem in hospitals and residential care settings despite being largely preventable (Crisp & Taylor 2009; Farrell & Dempsey 2011). See Chapter 27 for factors that affect skin integrity.

Effects of immobility upon the musculoskeletal system

Effects of immobility are evident after even short periods of inactivity. People who attempt to walk after several days of bed rest are surprised at how weak their leg muscles have become. Immobilisation and the resultant disuse of muscles lead to decreased joint mobility, bone demineralisation, and atrophy of muscles with decreased size, strength and tone.

Contractures and ankylosis

Contractures are abnormal conditions of a joint. Contractures are characterised by flexion and fixation and caused by atrophy and shortening of muscle fibres. Ankylosis is joint consolidation and immobilisation. Contractures may result from improper support or positioning of a joint, or as a result of inadequate joint movement. For example, if a joint is allowed to remain in one position for an extended length of time, the muscle fibres that normally provide movement shorten to accommodate that position, and lose the ability to contract and relax. Weight-bearing activity stimulates bone formation and balance; however, during immobilisation, bone formation slows, while breakdown of bone increases. With the subsequent loss of bone calcium, phosphorus and matrix, disuse osteoporosis results, and the brittle demineralised bones fracture easily.

For prevention, encourage physical activity and isometric or isotonic active ROM exercises while the client is in correct body alignment. An immobilised person may need direction as well as assistance when they perform ROM exercises. Pressure-relieving devices, such as a bed cradle, may prevent the bedclothes pressing down and forcing joints into abnormal positions (Berman et al 2012; Crisp & Taylor 2009; Hoeman 2008).

Footdrop

Footdrop is another term for plantar flexion, which is caused by damage to the nerve supply of the muscle responsible for dorsiflexion of the foot (Fig 26.16). If a client’s feet are allowed to assume plantar flexion for long periods they become fixed in that position so that, when the client attempts to stand or walk, they will be unable to place their heels on the floor and walk normally.

Prevention includes using a foot board or firm pillow in the bed to maintain the feet in proper alignment, or dorsiflexion, as if in a standing position (if not contraindicated); that is, at a 90-degree angle. Devices and techniques to keep pressure off the feet should be used, such as a bed cradle or foot pleat in the upper bedclothes. The person’s feet should be exercised through their ROM, either actively or passively. If footdrop occurs, management includes use of an orthopaedic brace, intensive physiotherapy or surgical intervention (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Effects on the cardiovascular and pulmonary systems