CHAPTER 40 Acute care

After the completion of this chapter, and with further reading, students should be able to:

• Discuss the increased scope of practice for enrolled nurses and the impact this has on clinical practice

• Identify the impact of acute health problems on the client and family

• Describe nursing interventions to support healthcare of clients with acute health problems

• Demonstrate critical thinking and problem-solving approaches in undertaking client care

• Develop nursing care plans for the client with acute health problems

Traditionally, enrolled nurses (EN) worked in the aged care setting. With increasing scope of practice, enrolled nurses are now moving into new clinical areas. Enrolled nurses now work in nearly all nursing disciplines and have become valued, skilled members of staff, with an expanded scope of practice. However, increasing the scope of practice of enrolled nurses has not been without problems. Working in the acute care environment brings new challenges for the enrolled nurse; these are explored in this chapter.

Also explored in this chapter are clinical pathways. An understanding of clinical pathways is critical for all nurses and as the scope of practice expands for enrolled nurses it is of utmost importance that the enrolled nurse develops an understanding of these crucial tools for practice.

I work in a busy diagnostic imaging department. One day a client was brought down to the nuclear medicine department for a VQ with a suspected PE; she had had an emergency caesarean the day before and was clinically obese. We placed her on the table and put an oxygen saturation monitor on her, which was protocol. She was already on 2 L of oxygen via nasal prongs as she was having dyspnoea and desaturation. As we commenced the scan her oxygen saturation started to decrease; she was experiencing more dyspnoea but the doctors present did not want to stop the scan. I increased her oxygen to 4 L and tried to comfort her, while asking the nuclear medicine technologist to call another nurse from my department for assistance. She arrived and went to get the crash cart. All the while the client’s oxygen saturations were decreasing: she was becoming tachycardic and tachypnoeic. The doctors present, who were radiologists, not the woman’s treating unit, refused to allow us to make a medical emergency team (MET) call. As the client’s condition continued to decline in front of us, the other nurse present and I decided to override the doctors and make a MET call. As soon as she left the room to make the call, the client went into cardiac arrest. We commenced CPR immediately and called a code blue. The team arrived and took over, the client was transferred to the ICU but passed away 2 days later. What I learnt from that experience is to trust your instincts: make the MET call early—better to call it and not need it. If the MET call had been made earlier the client might have survived.

SCOPE OF PRACTICE

The healthcare system is under increasing pressure due to an ageing population, increase in chronic diseases and advancing medical technologies (Nankervis et al 2008). In every health setting there is a shortage of nurses (Haultain et al 2011), which is due in part to an ageing workforce and an increased demand by nurses and other health professionals to work part-time (Nankervis et al 2008). In order to overcome this shortage, the traditional roles of both registered nurses (RN) and ENs are developing rapidly. The RN role has traditionally been viewed as that of the assessor, planner and evaluator of care, while the EN worked under the direct supervision of the RN (Eagar et al 2010). But in recent years both the RN and the EN scope of practice has been expanded. This includes the creation of the nurse practitioner role for RNs and the ability for ENs to now administer oral and, increasingly, intravenous medications (Nankervis et al 2008). This increase in scope of practice has been met with resistance from both inside and outside the nursing profession. ENs report feeling undervalued and that the expanded scope of practice is not supported within the profession itself (Nankervis et al 2008). RNs are concerned that expanding the scope of ENs will lead to them taking over ward work, with RNs pushed into more managerial roles (Eagar et al 2010). Both groups agree that there is a lack of role definition, leading to confusion and uncertainty regarding roles (Eagar et al 2010; Nankervis et al 2008). However, expanding the scope of practice for ENs must be viewed in a positive light. It will enable ENs to practise with greater autonomy and relieve time pressures for the RNs. Nurses with higher education should only be viewed as a positive development.

WHERE IS ACUTE CARE DELIVERED?

Hospital care

When discussing acute care most people will automatically assume care takes place in a hospital and in many cases this is where care commences. For many clients suffering an acute illness their first encounter with healthcare will be in the emergency room. From there varied outcomes can result. For some clients the condition will be treated and they will be discharged home, with or without outpatient follow-up. Others will require admission to hospital and may require surgery, admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) or high dependency unit (HDU) before reaching a ward. (For more information regarding care of the client requiring surgery see Ch 41.)

ICUs care for critically ill or injured clients who have various illnesses (O’Connor 2010). The care is usually one nurse to every client and involves invasive monitoring, care and treatments not available on general wards (Martin et al 2010). In 2006, there were 181 intensive care units in private and public hospitals in Australia and New Zealand (Martin et al 2010). In both Australia and New Zealand the majority of ICUs are classified as general; however, as outlined in Table 40.1, ICUs can be classified by type.

Table 40.1 ICUs can be classified as:

| General ICU | Those that care for both medical and surgical clients |

| Combined ICU | Combined ICUs where an ICU is combined with an HDU and/or coronary care unit |

| Paediatric ICU | Specialises in care of paediatrics |

| Neonatal ICU | Specialises in care of neonates |

| Speciality ICU | Examples are cardiothoracic, neurological or oncology |

HDUs provide a level of care between ICU and the general wards (Gould et al 2010). Most hospitals will also have high dependency units, either as stand-alone wards or, more commonly, dedicated rooms on each ward. HDUs work as a step down from ICU for those clients who no longer require the invasive monitoring of an ICU but are not yet ready for a general medical or surgical ward. The aim of HDUs is to reduce the workload of ICUs by reducing the incidence of ICU admissions (Gould et al 2010).

When caring for clients from a Chinese background it is important to have an understanding of Chinese culture and beliefs. Many Chinese believe in the Yin (female, negative energy, cold) and Yang (male, positive energy, hot). If an imbalance occurs between the Yin and the Yang, illness results. Foods, illness and treatments are classified as hot or cold. Clients and their families will try to restore the balance of Yin and Yang so you may find clients with heat or cool packs, depending on how the illness has been classified. Likewise, the family may bring in food that they think will help to restore this balance.

The majority of clients with an acute illness will spend some time in a hospital on a general ward. Although referred to as general, the majority of wards in hospitals are specialised. The specialties include respiratory, cardiovascular, cardiopulmonary, neurological, burns, oncology, haematology, gastrointestinal, renal, trauma, surgery and paediatrics. When a client is admitted to acute care, the aim is always to allocate a bed on the most appropriate ward; however, with bed shortages this is not always possible.

Home care

For some clients care in the home is appropriate, even during an acute illness. In some Australian states this can be delivered via the Hospital in The Home (HITH) service or Royal District Nursing Service (RDNS). In both cases, delivery of care is done in the client’s home instead of hospital. HITH was introduced in some states of Australia in 1994 (Department of Health, Victoria 2012). When a client is treated under HITH the client is regarded as an inpatient of the hospital and remains under the care of the home unit doctor of the hospital (Department of Health, Victoria 2012). Clients admitted to HITH receive the same treatment they would receive if they were to remain an inpatient but have the benefit of being at home; this has been shown to result in better outcomes, such as reduced risk of hospital-acquired infection (Department of Health, Victoria 2012).

Many hospitals have now introduced HITH due to the cost benefits and the enhanced ability to better manage beds as clients can be discharged earlier (Department of Health, Victoria 2012). To be eligible for HITH the client must be clinically stable, have appropriate home support, live in a suitable environment, be willing to be treated by the HITH team and be suitable for treatment at home (Department of Health, Victoria 2012). The most common reasons for referral to HITH include intravenous antibiotics for cellulitis, genitourinary tract or respiratory tract infection, anticoagulation therapy and chemotherapy (Department of Health, Victoria 2012).

The Royal District Nursing Service (RDNS) was first introduced to Australia in 1885 and New Zealand in 2009 (RDNS 2011). The RDNS differs from HITH in that the client will not be considered an inpatient of a hospital. It is an independent, not-for-profit organisation that funds its service from state government funding in some states of Australia, and client fees, donations, sponsorship, corporate partnership and fundraising (RDNS 2011). Nurses working in the home care setting have to be prepared for the unexpected and be able to provide care in unconventional settings, sometimes at the kitchen table (Skott & Lundgren 2009).

IMPACT OF ACUTE ILLNESS

The client

Acute illness can occur suddenly and have devastating and long-term consequences. Once the client is diagnosed with an acute illness, there can be an increase in subsequent hospitalisations, which may be due to complications or ongoing manifestations of the initial illness (Williams et al 2010). This, of course, negatively impacts on a client’s quality of life. While they are in hospital it is important for them to be involved in making healthcare decisions and to receive education regarding their current condition so as to encourage them to take responsibility for their own health on discharge (Arnetz et al 2010).

Once discharged after an acute illness many clients will have ongoing physical and psychological issues related to their hospital admission. These issues can be related to the stress that an acute illness causes. When diagnosed with an acute illness clients have to deal with being in a foreign environment, the illness itself, physical or traumatic injury, feelings of mortality, fear, pain and the unknown impact this illness will have, not only on their own life but also the lives of their loved ones (Kelly & McKinley 2010). Post discharge clients may report fatigue, weakness, ongoing pain, sleep difficulties, nightmares and flashbacks which can all lead to mood changes and impact on the client’s ability to cope with their new-found lifestyle (Kelly & McKinley 2010). After an acute illness clients may find that their role and responsibilities in the family have altered; they may be more dependent on others, which is a big adjustment to make and which can lead to feelings of resentment (Kelly & McKinley 2010).

Clinical Scenario Box 40.1

Rebecca’s acute care experience

About 2 years ago Rebecca started experiencing intense headaches which culminated one day in her passing out at work. She worked as a nurse and her nurse unit manager put her in a wheelchair and took her around to the emergency department of the hospital that she worked in. This was the beginning of 2 months of being admitted and discharged from hospital five times. She had all the tests done, MRI, CT, blood test and even a lumbar puncture and no doctor could tell Rebecca why her head felt like it was going to explode. When admitted to the wards, she felt that once the nurses realised that they were caring for a fellow nurse, they treated her differently to other clients. Treatments didn’t get explained as it was assumed that she understood what was happening. No one explained to her the reasoning behind all the tests she was having. For Rebecca, one of the scariest experiences was when she had a drug reaction; she thought she was going to die.

On her last admission one of the nurses looking after her suggested she see an osteopath and get her back and neck looked at. Rebecca took her advice and achieved some relief. Two years on and what started as an acute episode has turned into a chronic pain issue. Rebecca has had to change jobs and work part-time as the chronic pain causes her constant exhaustion. This has had a major impact on her life and she has had to modify her lifestyle to manage the pain she experiences every day.

The family

When the nurse is caring for an acutely ill client, they must take care to include the family. Historically, nurses and doctors have not been not good at predicting what the family needs and therefore the family’s needs may not be met (Davidson 2009). When a client is unexpectedly admitted to hospital the family may display physical, emotional and behavioural responses to situations based on personal coping mechanisms and feelings for or the intensity of their love and commitment to the ill relative (Vandall-Walker 2010). It is a highly stressful time characterised by feelings of fear and anxiety caused by disruptions and changes to family relations (Davidson 2009). To help families during this time of high stress it is important to communicate expected healthcare outcomes and to keep open the lines of communication. Families reported less satisfaction with the care their loved one received when there was a lack of communication from both nursing and medical staff (Davidson 2009).

For the family of an acutely ill client the journey really only continues once the client has been discharged home. For many families this means taking on the care of the client with or without the help of community-based services. Roles in the family can be reversed, with children becoming the carer. There can be financial hardship, which adds to the stress that carers face. Studies show that partners who become carers are exhausted, excessively overprotective, burdened, anxious and suffer from the effects of ill health (Dougherty & Thompson 2009). On a more positive note, stress for the family and client is at its greatest at time of discharge and will decline over time (Dougherty & Thompson 2009).

Clinical Scenario Box 40.2

Rebecca’s acute care experience: the family’s perspective

When Rebecca started experiencing headaches I thought nothing of it; she has suffered from migraines since a young age. Then suddenly they escalated and she had to be admitted to hospital multiple times. I cannot explain the sense of helplessness I felt as her mother. I felt I should have been able to make it all better. It was very frustrating that the doctors could not give us any answers; they didn’t listen to her when she said it wasn’t a migraine. One of the worst moments for me was receiving a phone call from my sister who was visiting Rebecca when she had the drug reaction. My sister thought Rebecca was going to die. Another moment that stands out for me was being ordered from her room as nurses rushed in. No one told me what was going on. I found out later she had been given too much morphine and had a dangerously low respiratory rate. Two years on and I am proud of how Rebecca deals with the pain; most people have no idea that she has pain every day. It is lucky that I am a casual worker so I can take time off when Rebecca needs to be taken to hospital; I don’t know what would happen if I had to work full-time.

ACUTE DISORDERS

We now look at acute disorders that have not been covered in other chapters. For more information on specific systems refer to the Contents.

Cellulitis

Cellulitis is a common cause of limb swelling (Farrell & Dempsey 2011). It is an acute, localised bacterial infection of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Ruan et al 2010).

Clinical manifestations

Clinical manifestations of cellulitis include localised swelling, redness and pain. The client may also develop systemic signs of infection such as fever, chills and sweating (Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Pathophysiology

The cellulitis infection can spread due to the production of a substance known as hyaluronidase (spreading factor). This substance is produced by the causative agent and breaks down fibrin networks and other barriers that normally localise infection (LeMone et al 2011). Cellulitis can occur following a skin breakdown or surgical wound; in some instances there is no obvious causative incident (Eron 2009). Common sites of infection include cracks between toes, injection sites, abrasions and contusions, ulcers, ingrown toe nails and hang nails (Farrell & Dempsey 2011). Human and insect bites have a high risk of causing cellulitis (Eron 2009). (See Clinical Interest Box 40.1.)

Medical management

When the infection is mild, the client can be treated with oral antibiotics. For severe cases intravenous antibiotic therapy is required (Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Nursing care

When caring for the client with cellulitis the nurse should instruct the client to elevate the affected area above the heart (Farrell & Dempsey 2011). Warm, moist packs should be applied to the area every 2 to 4 hours; care must be taken in clients with decreased sensory perception to ensure burns do not occur (Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Client education

Client education for cellulitis has an emphasis on prevention of future episodes (Farrell & Dempsey 2011)

Venous thromboembolism

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) includes both deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) (Collins 2009). It is estimated that VTE will occur in between 10% and 20% of all general medical clients, 20% and 50% of clients who have suffered a cerebrovascular accident and 80% of critically ill clients (Morrison 2006).

Deep vein thrombosis

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a thrombosis in the deep veins of the body, usually involving the lower extremities (Collins 2009). The thrombosis can partially or completely obstruct the vein, restricting blood flow to the affected extremity (Collins 2009).

Clinical manifestations

A diagnosis of DVT can be difficult to make as the clinical manifestations can be similar to other diseases such as cellulitis. Clinical manifestations of a DVT may include unilateral oedema, pain, localised warmth and erythema (Carter 2010). (For information on prevention of DVTs see Ch 26).

Pathophysiology

A thrombosis can develop when there are changes in the vessel walls, changes in blood flow or changes in blood composition. These three conditions are known as Virchow’s triad (Bacon 2009).

Diagnostic tests

If a DVT is suspected, a blood test known as the D-dimer can be performed. This detects fibrin breakdown that is present in the blood post thrombus formation. The test is used for negative predictability only, meaning that a negative result indicates no DVT, while a positive will result in further tests being carried out (Carter 2010). If a positive D-dimer occurs the client may then be sent for an ultrasound—the most appropriate and accurate test for diagnosing a DVT (Carter 2010).

Medical management

Once the diagnosis of DVT is made, treatment needs to commence immediately. Traditionally clients were put on bed rest as the assumption was that movement would dislodge the thrombus and lead to a pulmonary embolism (Anderson et al 2009). The current treatment regimen includes a combination of anticoagulation therapy and thrombolytic therapy with the aim of preventing the thrombus from growing or fragmenting (Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Nursing care

When caring for the client with a DVT the nurse must monitor the client for potential complications of treatment such as bleeding and thrombocytopenia. The nurse should also maintain client comfort by elevating the affected extremity, applying compression stockings and administering analgesia; these all help to increase circulation (Farrell & Dempsey 2011). The affected leg should be assessed every shift for signs of skin breakdown down to enable early intervention. The client must also be monitored for signs of PE (see below) (LeMone et al 2011).

Client education

Prior to discharge inform the client that they need to report any unusual bleeding to their doctor. For women, menstrual bleeding may be slightly increased: they should contact their doctor if it increases significantly. Men should shave with an electric razor to reduce the risk of cuts and soft-bristle toothbrushes should be used. Contact sports should be avoided while taking anticoagulation drugs (LeMone et al 2011).

Pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a major cause of mortality and morbidity (Otair et al 2009). For 25% of clients who suffer a PE the first clinical symptom is death (Farley et al 2009). The risk factors associated with the development of a PE are very similar to those for a DVT (see Clinical Interest Box 40.2).

Clinical manifestations

The clinical manifestations of PE may include chest pain, chest wall tenderness, palpitations, back and shoulder pain, upper abdominal pain, syncope, haemoptysis, dyspnoea and painful respirations (Farley et al 2009).

Pathophysiology

PE involves obstruction of a section of the pulmonary artery tree by a thrombus or embolism (Sheares 2011). This thrombus or embolism forms in the venous system or right side of the heart (Farrell & Dempsey 2011) and commonly originates in the leg or pelvic vein (Sheares 2011).

Diagnostic tests

Diagnosis of PE can be difficult because of the non-specific symptoms that are manifested (Otair et al 2009). If the clinical manifestations indicate the possibility of PE (chest pain, chest wall tenderness, palpitations, back and shoulder pain, upper abdominal pain, syncope, haemoptysis, dyspnoea and painful respirations) (Farley et al 2009), then a D-dimer test may be ordered; if this test is positive then more investigations are required to confirm the diagnosis. Table 40.2 outlines investigations for diagnosis of PE.

Table 40.2 Investigations for diagnosis of pulmonary embolism

| Chest x-ray | May be normal but may also show atelectasis, pleural effusion, hypovascularity or peripheral lobe infarcts |

| Electro-cardiogram (ECG) | May indicate that the right ventricle is strained in the form of inversion of T waves in leads V1–V4 or QR pattern in lead V1, S1Q3T3 pattern and incomplete or complete right bundle branch block |

| Arterial blood gases | May show that the client has hypoxaemia and hypocapnia or they may be normal |

| Ventilation-perfusion scan (VQ scan) | A ventilation-perfusion scan involves injection via an intravenous line and inhalation by the client of a contrast agent. The lungs are scanned at different angles and a comparison made of the percentage of ventilation and perfusion in each area; a hypoperfused area indicates the presence of a PE |

| Pulmonary angiogram | Allows for direct visualisation of a thrombus or embolism in a pulmonary artery branch and so is the most accurate diagnostic test for PE. However while pulmonary angiogram is considered the most accurate, it is not cost effective or easily performed |

| Computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) | CTPA has replaced pulmonary angiograms in the diagnosis of PEs. This type of CT evaluates slices as narrow as 1.0 mm, allowing for accurate visualisation of a PE by enabling visualisation of the pulmonary arteries. The main disadvantages of the CTPA are that the client must be transferred to a diagnostic imaging department as the CT is not portable and the client must be injected with contrast, which can cause allergic reactions and is contraindicated in clients with renal impairment and those taking metformin |

Farrell & Dempsey 2011; Sheares 2011

In recent years the computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) has replaced pulmonary angiograms in the diagnosis of PEs (Sheares 2011). This type of CT evaluates slices as narrow as 1.0 mm (Farrell & Dempsey 2011) allowing for accurate visualisation of a PE by enabling visualisation of the pulmonary arteries (Sheares 2011). The main disadvantages of the CTPA are that the client must be transferred to a diagnostic imaging department as the CT is not portable and the client must be injected with contrast, which can cause allergic reactions and is contraindicated in clients with renal impairment and those taking metformin (Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Medical management

The best treatment for clients at risk of developing a PE is prevention (Farrell & Dempsey 2011). Many hospitals now require all clients to have a risk assessment performed on admission. Those deemed at high risk for DVT or PE are commenced on a prophylaxis regimen, such as enoxaparin (Rogers 2010). This is usually given twice a day subcutaneously and may continue even after discharge (Rogers 2010). The client with a diagnosed PE will be commenced on anticoagulation therapy, most usually heparin (Farrell & Dempsey 2011). The regimen may be changed once the international normalised ratio (INR) is stabilised by oral anticoagulants like warfarin (Farrell & Dempsey 2011). Clients can also be commenced on low-molecular weight heparin or heparinoids such as enoxaparin. The advantage of these drugs is the need for less frequent monitoring and dose adjustment than warfarin. For clinically unstable clients, thrombolytic therapy may be required (Farrell & Dempsey 2011). Thrombolytic therapy involves injecting urokinase, streptokinase or alteplase to break down a thrombus or embolism quickly. However, the client is at significant risk for haemorrhage (Farrell & Dempsey 2011). See Table 40.3 for emergency management of PE.

Table 40.3 Emergency management of pulmonary embolism

| Nasal oxygen | Relieves hypoxaemia and respiratory distress |

| Insertion of intravenous lines | Prepares for medication administration |

| ECG | Provides continuous monitoring for arrhythmias and right ventricular failure |

| Medications | May include digoxin glycosides, diuretics, enoxaparin, heparin and antiarrhythmic agents. Sedatives may be administered to relieve anxiety |

| Blood tests | Include serum electrolytes, full blood count, haematocrit and arterial blood gases |

| Indwelling urinary catheter | Inserted to monitor fluid output |

| Mechanical ventilation | Used if the clinical assessment and investigations warrant it |

Nursing care

The management of a PE depends on the severity of the client’s condition. The nurse initiates interventions aimed at improving respiratory and vascular status; these interventions include oxygen therapy and elevation of lower extremities (Farrell & Dempsey 2011). Antiembolic stockings or intermittent pneumatic leg compression devices may be used to decrease venous status (Farrell & Dempsey 2011). When caring for the client with a PE the nurse must monitor for signs of bleeding and only essential venepunctures are performed. The client’s pain and anxiety must be managed, with medication if necessary. Vital signs should be monitored every 2 hours, increasing when deterioration is noted (Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Client education

The client will require education regarding adherence to medication regimens. This will include anticoagulants therapy education (see client education for DVT above) and information regarding follow-up appointments and blood tests (LeMone et al 2011).

Diverticulitis

It is estimated that up to 40% of people over the age of 40 have diverticulosis, a disease where pouches, known as diverticula, develop in the bowel wall, usually in the sigmoid colon (Harvard Women’s Health Watch 2011).

Clinical manifestations

Clients with diverticulitis will present with left lower quadrant abdominal pain, abdominal tenderness, increased white blood cells counts and fever (Lipman 2011).

Pathophysiology

Diverticula usually develop at a weak spot in the muscle wall, allowing the inner layer of the wall to balloon outwards (Harvard Women’s Health Watch 2011). For the majority of people with diverticulosis, the diverticula cause no problems; however, some will go on to develop diverticulitis. Diverticulitis occurs when a diverticula is either eroded by pressure or faecal matter becomes trapped (Harvard Women’s Health Watch 2011), leading to infection. The damage can range from mild to severe. Perforation can occur, allowing bowel matter to leak into the abdomen causing abscess formation (Lipman 2011). The pathophysiology for this happening for some and not all people with diverticulosis is not known but research suggests that chronic inflammation may be the cause (Lipman 2011).

Diagnostic tests

For clients presenting with signs and symptoms as outlined above, diagnosis of diverticulitis is achieved via abdominal CT with contrast, as it will enable visualisation of infection, as well as any perforations and abscesses.

Medical management

Treatment of diverticulitis involves broad-spectrum antibiotics, usually metronidazole and ciprofloxacin, and a liquid diet (Lipman 2011). For some clients who develop an abscess that fails to respond to antibiotic therapy a drain tube may need to be inserted into the abdomen to drain the infected fluid (Harvard Women’s Health 2011). For some clients who suffer repeat attacks, surgery to remove the affected area of bowel may be the only option as bowel function can be permanently diminished due to scarring, narrowing and loss of normal contractions (Lipman 2011).

Nursing care

As the client with diverticulitis is at risk for bowel perforation, vital signs must be monitored 4 hourly or more frequently if clinically required. The abdomen should be assessed at the same time, measuring girth, auscultating bowel sounds and palpating for tenderness. Any changes must be immediately reported to the doctor as they may indicate spread of infection. The client will be rest in bed with limited activity to promote healing. Pain relief is paramount so the client should be assessed frequently for pain (LeMone et al 2011).

Client education

On discharge clients need education on diet. A high fibre diet is required to reduce complications. The client may benefit from a consultation with a nutritionist or dietitian, for which the nurse can make a referral (LeMone et al 2011).

Guillain-Barré syndrome

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a rare acute inflammatory polyneuropathy (Schub et al 2011). It is characterised by rapid and progressive neuromuscular paralysis (Schub et al 2011). There is no known cause of GBS; however, up to two-thirds of clients who are diagnosed with this condition have a 1 to 3 week previous history of upper respiratory or gastrointestinal infection (Lugg 2010). The pathophysiology of GBS is demyelination of nerves, most commonly peripheral nerves, by antiganglioside antibodies which attack the Schwann cells of the myelin sheath. This causes diminished nerve conduction which causes severe weakness and often paralysis (Schub et al 2011). Clients with GBS will initially complain of decreased function, weakness and decreased sensation in their arms and legs, with or without pain (Lugg 2010). This rapidly develops into muscle weakness, commencing distally then travelling to proximal with decreased reflexes and sensations (Lugg 2010). For some clients the disease progression will stop there; they will experience difficulty walking but will be able to be discharged to home (Lugg 2010). Others will progress to total paralysis. It is estimated about 30% of clients with GBS will require mechanical ventilation because of respiratory dysfunction and up to 10% will die from the syndrome (Lugg 2010). The disease progression is usually 4–8 weeks and is confirmed with a lumbar puncture, electromyography and nerve conduction studies (Pritchard 2010). Treatment of GBS is supportive. Over time the Schwann cells will re-myelinate and most clients can expect a full recovery (Schub et al 2011). When assessing the client with GBS the nurse should monitor airway and breathing, refer to speech pathology and maintain the client as nil by mouth until otherwise ordered, ensure adequate analgesia, perform pressure area care and take steps to reassure the client.

Acute renal failure

Acute renal failure (ARF) is defined as a rapid decline in kidney function causing a rise in serum creatinine and/or blood urea nitrogen levels with or without a decrease in urine output (Yaklin 2011). The decrease in renal function can be over days to weeks (Warise 2010). It can be a common complication in critical areas with as many as 5% of all critically ill clients developing ARF (Warise 2010). For the majority of cases of ARF there is an underlying problem which, if identified and treated early, can prevent the development of ARF. These problems include hypovolaemia, hypotension, reduced cardiac output and heart failure, obstruction of the kidney or lower urinary tract and bilateral obstruction of the renal arteries or veins (Farrell & Dempsey 2011). Risk factors for the development of ARF include age greater than 60, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, nephrotoxic drugs, volume depletion and underlying kidney disease (Yaklin 2011).

Clinical manifestations

When ARF is present all systems of the body are affected. The client can rapidly become critically ill, showing symptoms of lethargy, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea (Farrell & Dempsey 2011). The client may exhibit signs and symptoms of dehydration, their breath may smell of urine, they may complain of a headache, muscle twitching and may even develop seizures (Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Pathophysiology

ARF can be classified into three categories: prerenal failure, intrarenal failure and postrenal failure.

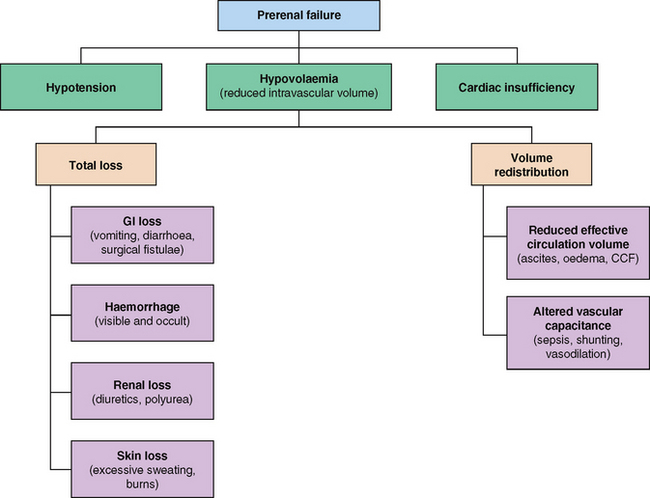

• Prerenal failure is the result of hypoperfusion of the kidneys (Yaklin 2011). The hypoperfusion may be the result of volume depletion from hypotension, hypovolaemia or cardiac insufficiency (Murphy & Byrne 2010) (Fig 40.1).

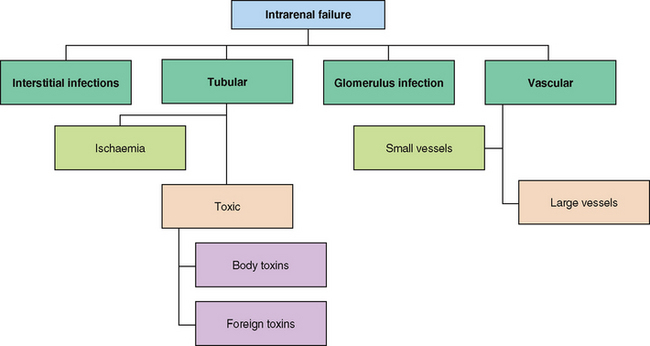

• Intrarenal failure results when there is damage to glomerulus, vessels or kidney tubules. This is most often caused by prolonged prerenal causes (Fig 40.2), infections and toxins that result in inflammation or injury (Yaklin 2011).

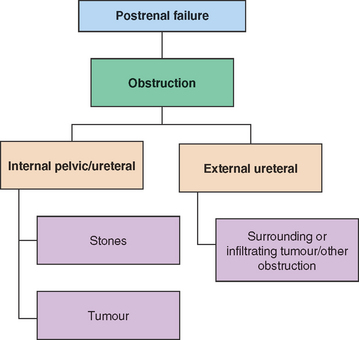

• Postrenal failure is caused by obstruction, which may be as a result of renal calculi, strictures, thrombosis, benign prostate hypertrophy, malignancies and pregnancy (Yaklin 2011) (Fig 40.3). The obstruction causes pressure to increase in the kidney resulting in injury to the kidney.

Diagnostic test

When a client is suspected of having ARF there are many investigations that may be ordered. These include:

• Blood test tests (including urea, creatinine and electrolytes, full blood examination, coagulation status, virology for hepatitis B and C and HIV)

• Renal biopsy (Murphy & Byrne 2010).

Medical management

The investigations required depend on the individual and the results of the health assessment (Murphy & Byrne 2010). Once a diagnosis is made the medical aim is to restore chemical balance and prevent complications to allow the kidney to repair itself (Farrell & Dempsey 2011). If there is a known cause it is treated and eliminated. For some clients dialysis is required (see Ch 29).

Nursing care

When caring for the client with ARF the nurse needs to closely monitor fluid balance. This can be done by commencing the client on a strict fluid balance and daily weighing regimen, ensuring that the client is weighed at the same time on the same scales and in the same clothes every time. The nurse should also monitor the client for signs of oedema and any difficulty in breathing (Farrell & Dempsey 2011). Clients with ARF are at increased risk of infection and skin breakdown, therefore the nurse should ensure asepsis when caring for these clients and meticulous skin care to prevent skin breakdown (Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Client education

The client with ARF needs education to identify complications of fluid volume excess such as increased weight or oedema. Educate to avoid nephrotoxic agents for at least 1 year post ARF. The client will need to avoid stress and infection (LeMone et al 2011). (See Table 40.4.)

Table 40.4 Differences between acute renal failure and chronic renal failure

| Acute renal failure | Chronic renal failure | |

|---|---|---|

| Health history | Recent presentation of acute illness | |

| Clinical examination | Hypotension, oedema/fluid overload | |

| Renal ultrasound |

Sepsis

Sepsis is an infection of the blood stream that spreads quickly and can be difficult to diagnose (Dellacroce 2009). For a diagnosis of sepsis to be made the client must have a known infection and systemic inflammatory reaction syndrome (SIRS) (see Clinical Interest Box 40.3).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 40.3 SIRS

For a diagnosis of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) to be made the client must display two or more of the following:

The most common sites of infection that lead to sepsis are infections in the bloodstream, skin, respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract and genitourinary tract (Schub & Schub 2011). Gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria are the usual causative agents; however, the infection can also be due to fungi, viruses and protozoa (Farrell & Dempsey 2011).

Clinical manifestations

Clinical manifestations include fever, peripheral oedema, hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnoea and hot flushed skin (LeMone et al 2011).

Risk factors for the development of sepsis include cauterisation, invasive devices, certain surgery, urinary tract infections, appendicitis, diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease, cholecystitis, renal disease, prostatitis, meningitis and complicated obstetric delivery (Schub & Schub 2011). Older adults, children and immunosuppressed clients are at an increased risk of sepsis progressing to severe sepsis and septic shock (Schub & Schub 2011).

Pathophysiology

Sepsis develops when the body is unable to contain a localised infection, enabling the infective agent to enter the blood stream (Dellacroce 2009). The associated SIRS can impair the clotting cascade, causing systemic inflammation, vasodilation and capillary leakage which contributes to hypotension and can lead to organ failure (Whitehead 2010). Sepsis can develop into severe sepsis. Severe sepsis involves all the clinical features of sepsis but has the added complication of organ dysfunction (Dellacroce 2009) (see Table 40.5). When a client is diagnosed with severe sepsis there is a 30–35% chance of death (Whitehead 2010).

Table 40.5 Signs of organ failure

| Body system | Clinical manifestation |

|---|---|

| Neurological | Decreased mental alertness |

| Urinary | Acute oliguria |

| Endocrine/metabolic | Hyperglycaemic without the presence of diabetes |

| Respiratory | Tachypnoea, hypoxaemia |

| Gastrointestinal | Paralytic ileus, no bowel sounds |

| Circulatory system | Decreased cardiac output, decreased perfusion/BP |

One of the major complications of severe sepsis is hypotension. When a client remains hypotensive in spite of adequate fluid resuscitation, the client has progressed into septic shock (Dellacroce 2009). Septic shock is a life-threatening condition, with 1400 people worldwide dying each day (Gerber 2010). After diagnosis of septic shock, 30% of clients will die within the first month and 50% within 6 months (Gerber 2010). See Clinical Scenario Box 40.3.

Clinical Scenario Box 40.3

Septic shock

Melissa, a 26-year-old female with acute myeloid leukaemia, was admitted to the ward. She had undergone a bone marrow transplant, which had yet to take and she was neutropenic. She started spiking temperatures of 38°C or more. As per protocol the medical officer ordered blood cultures every time this happened, which kept coming back negative. This continued for 2 days before she deteriorated very suddenly and was taken to the ICU in septic shock. A chest x-ray showed she had developed a fungal infection in the left lower lobe of her lung, and this was suspected as the causative agent. The medical officers made the decision to remove the affected lobe of lung to remove the source of infection. The client spent over a month in the ICU before returning to the ward and another 4 months with us before she could be discharged.

Diagnostic test

As soon as sepsis is suspected blood cultures should be taken, ideally prior to the commencement of antibiotic therapy. The cultures should be taken from all lumens of central and peripheral lines (Dellacroce 2009).

Medical management

Oxygen therapy should be commenced at high-doses to stabilise oxygen saturations (Steen 2009). Fluid resuscitation which includes both colloids (albumin and packed red blood cells) and crystalloids (normal saline and Ringer’s lactate) is commenced, with the aim of maintaining blood pressure greater than >100 systolic blood pressure (SBP) (Dellacroce 2009). Urine output is monitored with a goal of >0.5 mL/kg/hr and it is recommended that a urinary catheter be inserted (Steen 2009). Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics are commenced until an infective agent is identified; these should be commenced within 1 hour of the diagnosis (Steen 2009). The client’s serum lactate levels may need to be measured as increased levels indicate progressing disease (Steen 2009).

CLINICAL PATHWAYS

A clinical pathway is best described as a multidisciplinary, locally approved plan of care for a client based on guidelines and, wherever possible, evidenced for a particular client group (Duffy et al 2011).

The clinical pathway was introduced in the 1980s in the USA to meet the needs of healthcare professionals and improve quality of care for clients (Duffy et al 2011). The main aim is to encourage standardisation of care for all clients (Neuman et al 2009) with similar requirements throughout a specific time frame by providing clinical standards and expected outcomes (D’Entermont 2009; Neuman et al 2009).

The development of clinical pathways combines an evidence-based approach, with local policy and procedure and current practice to develop a process map which in turn is developed into a pathway (Day 2009). The pathway enables less variation and more transparency in client care (Vanhaecht et al 2009).

Clinical pathways are most advantageous when client outcomes are predictable, thus ensuring that the client receives relevant clinical interventions and assessments (Allen et al 2009). While clinical pathways cannot be used for all clients, in 80% of cases a clinical pathway is indicated (Duffy et al 2011). Pathways provide a daily care plan for the client, and include guidelines on assessment, treatment, activities of daily living, nutrition, education, referrals to be made and discharge planning (D’Entermont 2009).

The novice nurse can find pathways especially helpful by providing a guide as to what is expected of the client on any given day (D’Entermont 2009). However, it is not just the novice nurse who benefits from clinical pathways; even the most experienced nurse will encounter client conditions they are unfamiliar with and the pathway will enable them to provide the most appropriate care for these clients.

Clinical pathways can form all or part of the client’s medical records (Duffy et al 2011). At the end of a shift, providing there has been no variation from the pathway, the nurse responsible for the client’s care signs off that all expected outcomes and interventions have been met. When a variation from the plan has occurred the nurse is expected to document this in the client’s progress notes.

Studies have shown that clinical pathways improve client outcomes, promote decision making and may lead to shorter hospital stays and reductions in readmission (Allen et al 2009). Shorter hospital stays are achieved as clinical pathways act as an organisational device by encouraging proactive interventions and the use of relevant resources for the client (Allen et al 2009). However, not all clients are appropriate for clinical pathways. Clinical pathways are not effective when care needs to be flexible, such as with the care of the client post cerebrovascular accident (Allen et al 2009). Clinical pathways can never replace professional clinical judgment (D’Entermont 2009).

Summary

This chapter has presented some common and not so common conditions the enrolled nurse may encounter when working in the acute, aged or community care sectors. It has explored the area of acute care provided in venues other than hospitals and presented an introduction to clinical pathways. There are many acute conditions the enrolled nurse will come across, in various settings, and this introduction, along with further reading, provides a general introduction to a broad range of conditions that may be seen in acute settings.

1. You are looking after a client who has been admitted post a myocardial infarct. He is recovering post CABG surgery. Your client is the main income earner in his family and has three young children at home.

2. You receive handover from the morning nurse on one of your clients who is expected to be discharged this afternoon. Your client is a 39-year-old female admitted with a DVT who has responded well to treatment and will be transferred to the care of HITH. The nurse handing over to you reports that this morning the client complained of slight back and shoulder tip pain which was resolved with paracetamol. All paper work has been completed and the client is waiting for her discharge medications before she can leave. When you enter the client’s room, you find her pale and complaining of dyspnoea and chest pain.

1. You suspect your client has cellulitis. What are the common sites the infection originates from?

2. Which two (2) conditions are included under the term venous thromboembolism?

3. Identify the major risk factors associated with the development of a DVT.

4. What does a positive D-dimer test indicate?

5. Outline the treatment of a client who has been diagnosed with a pulmonary embolism.

7. List the clinical manifestations of diverticulitis.

8. What is a preceding factor for the development of Guillain-Barré syndrome?

9. Explain the pathophysiology of Guillain-Barré syndrome.

10. Provide a cause of each stage of acute renal failure.

11. What two (2) conditions must be present for a diagnosis of sepsis?

12. What are the common sites where a sepsis infection originates?

13. Define the term clinical pathway.

14. What is the main aim of clinical pathways?

15. For what clients are clinical pathways most appropriate?

References and Recommended Reading

Allen D, Gillen E, Rixson L. Systematic review of the effectiveness of integrated care pathways: what works, for whom, in which circumstances? Integrated Journal of Evidence-based Healthcare. 2009;7:61–74.

Anderson CM, Overend TJ, Godwin J, et al. Ambulation after deep vein thrombosis: a systemic review. Physiotherapy Canada. 2009;61(3):133–142.

Arnetz JE, Winblad U, Höglund AT, et al. Is patient involvement during hospitalisation for acute myocardial infarction associated with post-discharge treatment outcomes? An exploratory study. Health Expectations. 2010;13(3):298–311.

Bacon S. Understanding venous thromboembolism. Practice Nursing. 2009;20:334–341.

Blakeley S, ed. Renal Failure and Replacement Therapies. London: Springer, 2008.

Carter K. Identifying and managing deep vein thrombosis. Primary Health Care. 2010;20(1):30–38.

Cegarra-Navarro JG, Wensley AKP, Sànchez-Polo MT. Improving quality of service of home healthcare units with health information technologies. Health Information Management Journal. 2011;40(2):30–38.

Collins S. Deep vein thrombosis—an overview. Practice Nurse. 2009;37(9):23–25.

Day R. Developing care pathways for hospice and neurological care: Evaluating a pilot. British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 2009;5(2):79–84.

Davidson JE. Family-centred Care. Meeting the needs of patients’ families and helping families adapt to critical illness. Critical Care Nursing. 2009;29(3):28–35.

Dellacroce H. Surviving sepsis: the role of the nurse. RN. 2009;72:16–21.

D’Entermont B. Clinical pathways: the Ottawa hospital experience. Canadian Nurse. 2009;105:8–9.

Department of Health, Victoria. Hospital in the Home. Online. Available: http://health.vic.gov.au/hith/, 2012.

Dougherty CM, Thompson EA. Intimate partner physical and mental health after sudden cardiac arrest and receipt of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Research in Nursing & Health. 2009;32:432–442.

Duffy A, Payne S, Timmins F. The Liverpool Care Pathway: does it improve quality of dying? British Journal of Nursing. 2011;20(15):942–946.

Eagar SC, Cowin LS, Gregory L, et al. Scope of practice conflict in nursing: A new war or just the same battle? Contemporary Nurse. 2010;36(1–2):86–95.

Eron LJ. Cellulitis and soft-tissue infections. American College of Physicians. 2009;ITC1:1–16.

Farley A, McLafferty E, Hendry C. Pulmonary embolism: identification, clinical features and management. Nursing Standard. 2009;23:49–50.

Farrell M, Dempsey J. Smeltzer & Bare’s Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing, 2nd edn., Broadway, NSW: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011.

Gerber K. Surviving sepsis: a trust wide approach. A multi-disciplinary team approach to implementing evidence-based guidelines. Nursing in Critical Care. 2010;15(3):141–151.

Gould A, Ho KM, Dobb G. Risk factors and outcomes of high-dependency patients requiring intensive care unit admission: a nested care-control study. Anaesthesia & Intensive Care. 2010;38(5):855–861.

Harvard Women’s Health Watch. Diverticular disease prevention and treatment. Harvard Women’s Health Watch. 2011;18:4–5.

Haultain R, Weston K, Rolls S. Realising enrolled nurses’ full potential. Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand. 2011;17(1):28–29.

Hsu C, O’Connor M, Lee S. Understanding of death and dying for people of Chinese origin. Death Studies. 2009;23(2):153–174.

Kelly MA, McKinley S. Patient’s recovery after critical illness at early follow up. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19(5–6):691–700.

LeMone P, Burke KM, Dwyer T, et al. Medical-Surgical Nursing. Critical Thinking in Client Care. Pearson, Frenchs Forest, NSW, 2011.

Lipman M. Diverticulitis reconsidered. Consumer Reports on Health. 2011;23:11.

Lugg J. Recognising and managing Guillain-Barré syndrome. Emergency Nurse. 2010;18(3):27–30.

Martin JM, Hart GK, Hick P. A unique snapshot of intensive care resources in Australia and New Zealand. Anaesthesia & Intensive Care. 2010;38(1):149–158.

Morrison R. Venous thromboembolism: scope of the problem and the nurse’s role in risk assessment and prevention. Journal of Vascular Nursing. 2006;24(3):82–90.

Murphy F, Byrne G. The role of the nurse in the management of acute kidney injury. British Journal of Nursing. 2010;19(3):146–152.

Nankervis K, Kenny A, Bish M. Enhancing scope of practice for the second level nurse: A change process to meet growing demand for rural health services. Contemporary Nurse. 2008;29(2):159–173.

Neuman MD, Archan S, Karlawish JH, et al. The relationship between short-term mortality and quality of care for hip fractures: A meta-analysis of clinical pathways for hip fracture. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(11):2046–2054.

O’Connor T. Providing intensive care. Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand. 2010;16(4):15–17.

Own C, Hemmings L, Brown T. Lost in translation. Maximizing handover effectiveness between paramedics and receiving staff in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2009;21:102–107.

Otair H, Chaudhry M, Shaikh S, et al. Outcome of patients with pulmonary embolism admitted to the intensive care unit. Annals of Thoracic Medicine. 2009;4(1):13–16.

Pritchard J. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Clinical Medicine. 2010;10(4):399–401.

Rogers J. Risk assessment and treatment of venous thromboembolism. Emergency Nurse. 2010;18(8):24–26.

Royal District Nursing Service (RDNS). Who We Are. Fact Sheet. Online. Available: www.rdns.com.au/media_and_resources/media/Documents/2011%20Royal%20District%20Nursing%20Service%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf, 2011.

Ruan X, Liu HN, Couch JP, et al. Recurrent cellulitis associated with long-term intrathecal opioid infusion therapy: A case report and review of the literature. Pain Medicine. 2010;11(6):972–976.

Schub E, Schub T. Sepsis and Septic Shock. CINAHL Information Systems, 2011.

Sheares K. How do I manage a patient with suspected acute pulmonary embolism? Clinical Medicine. 2011;11(2):156–159.

Schub T, Caple C, Pravikott D. Guillain-Barré Syndrome. CINAHL Information Systems, 2011.

Skott C, Lundgren SM. Complexity and contradiction: home care in a multicultural area. Nursing Inquiry. 2009;16(3):223–231.

Steen C. Developments in the management of patients with sepsis. Nursing Standard. 2009;23(48):48–55.

Vandall-Walker V. The work of family members: pushing our boundaries. Dynamics. 2010;21(2):39.

Vanhaecht K, De Witte K, Panella M, et al. Do pathways lead to better organized care processes? Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2009;15:782–788.

Warise L. Update: Diuretic therapy in acute renal failure—a clinical case study. MEDSURG Nursing. 2010;19(3):149–152.

Whitehead S. Sepsis alert: recognition and treatment of a common killer. EMS magazine. 2010;39(6):29–37.

Williams TA, Knuiman MA, Finn JC, et al. Effects of an episode of critical illness on subsequent hospitalisation: a linked data study. Journal of the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. 2010;65:172–177.

Yaklin KM. Acute kidney injury: an overview of pathophysiology and treatments. Nephrology Nursing Journal. 2011;38(1):13–19.