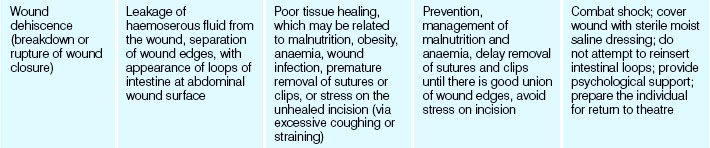

CHAPTER 41 Perioperative nursing

At the completion of this chapter, and with further reading, students should be able to:

• Describe the nature of the operative experience and outline the phases it entails

• Describe the client care roles of the perioperative nurse

• Describe the general physiological, psychological and local responses to surgical intervention

• Describe the various classifications of surgical procedures

• Assist in planning and implementing preoperative and postoperative nursing care for the client who requires surgical intervention

Perioperative nursing encompasses the care of a client who is undergoing a surgical procedure. Care takes place from the time the decision is made to have surgery, through to recovery from the procedure. Throughout the perioperative period it is essential that there is a flexible multidisciplinary team approach to ensure continuity of client care from admission, throughout the surgical experience to recovery at home. It is important for the nurse to be familiar with the types of surgery a client is likely to undergo in order to plan and implement adequate and individualised care and to provide appropriate psychological support. ‘The care encompasses safe and effective management in collaboration with other healthcare team members; the nurse also safeguards the client’s integrity by acting as an advocate for clients during their perioperative experience’ (Hamlin et al 2009).

This chapter provides an overview of the perioperative period, which comprises the preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative phases as well as the specific physiological and psychological support that each phase requires.

The first time I needed to have a surgical procedure since becoming a perioperative nurse, I felt fairly relaxed and confident. That was, until I was wheeled to the operating room. I felt like everyone was staring at me on the bed, wondering what was ‘wrong with me’. Then I was startled by how unsafe and vulnerable I felt being transferred to the table using a ‘Pat slide’. While the staff were very professional and kind, a little more explanation and talking to me, not about me, might have helped.

Then I had propofol injected into a small vein on the back of my hand. I could not believe how painful this was. I had been, for years, slightly dismissive of patients’ concerns when they complained of this very thing, thinking that they were overreacting. I believe that my practice has benefited from this experience. I was taught that pain is what patients say it is, but now I really believe it. I also believe that holistic care is optimal when the nurse is able to empathise and place him/herself in the client’s place, regardless of whether the nurse has personal experience of the situation or not.

PERIOPERATIVE CARE

The client’s experience of perioperative care is divided into three phases. Both registered nurses (RNs) and enrolled nurses (ENs) may fill any or all of the roles during the phases described below. These phases are fully described later in this chapter:

Perioperative nurses are RNs and ENs who fulfil the roles of circulating nurse (scout), instrument nurse (scrub), anaesthetic and postanaesthesia recovery nurse (see Table 41.1). The responsibilities of these nurses are specialised and multifaceted. The principal aim is to ensure that holistic, clinically effective, evidence-based care and support is given to the client throughout their perioperative experience. The perioperative nurse provides this care alongside other members of the multidisciplinary team, in an environment that is challenging, changing and fast paced. The nurse acts as the client’s advocate and provides continued and effective communication with the client, their significant others and the surgical team. The nurse undertakes efficient assessment and intervention, maintains accountability for their own practice, documents care and emphasises client safety in all phases (Crisp & Taylor 2009; Hamlin et al 2009).

Table 41.1 Role responsibilities of the perioperative nurse

In Australia professional standards, guidelines and policy statements for perioperative nursing are set by the Australian College of Operating Room Nurses (ACORN). ACORN’s ongoing focus is the improvement and standardisation, education and support of perioperative nursing care (Hamlin et al 2009).

SURGERY

Undergoing surgery is an experience that is unique to the individual; a client faces numerous stressors when confronting surgery. The anticipation of having a surgical procedure may incite fear and anxiety. Some clients associate having surgery with pain, disfigurement, loss of independence and even death. It is important for the perioperative nurse to quickly establish rapport with clients, listening to them so that their concerns are heard and relieved. What clients all have in common is the fact that, in the perioperative environment, they are at their most vulnerable and reliant on the skills and knowledge of the multidisciplinary team to achieve an optimal outcome.

The purpose of surgery

Surgery is performed for a variety of reasons:

• Diagnostic—surgical exploration that allows the surgeon to confirm a diagnosis; tissue may be removed for further diagnostic testing

• Ablative—excision or removal of a diseased body part

• Constructive—restores lost or reduced function resulting from congenital abnormalities

• Reconstructive—restores appearance or function to tissues that are traumatised or malfunctioning

• Cosmetic—performed to improve the client’s personal appearance

• Palliative—alleviates or reduces the intensity of disease symptoms, will not cure the disease (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Classifications of surgery

Surgery is classified under the descriptors of risk and urgency. The classification of the surgery for each client may change during the course of the disorder, depending on the time lapse between identification of the need for surgery, any increase in symptoms and the time surgery occurs (see Table 41.2).

Table 41.2 Classifications of surgery

Responses to surgical intervention

There is a degree of risk with any surgical procedure. Various factors and conditions increase a client’s risk during surgery. Knowledge of the risk factors allows the nurse to appropriately plan client care. Some of these risk factors include:

• Age—very young and very old clients are at risk during surgery due to their physiological status being immature or declining (see Table 41.3).

• Nutrition—the need for adequate nutrition is intensified by surgery; normal tissue repair and resistance to infection is dependent on sufficient nutrients

• Obesity—the bariatric (obese) client is at an increased surgical risk due to reduced ventilatory and cardiac function. Diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease and congestive heart failure are common in the bariatric population. They are also susceptible to wound infections and poor wound healing, due to the structure of fatty tissue which contains deficient blood supply

• Fluid and electrolyte balance—the body responds to surgery as a form of trauma; the more extensive the surgery the more severe the stress. The degree of fluid and electrolyte imbalance is influenced by the severity of the stress response evoked.

Table 41.3 Physiological factors that place older adults at risk during surgery

| Alterations | Risks | Nursing implications |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular system | ||

| Degenerative change in myocardium and valves | Reduced cardiac reserve | |

| Rigidity of arterial walls and reduction in sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation to heart | Alterations predispose client to postoperative haemorrhage and rise in systolic and diastolic blood pressure | |

| Increase in calcium and cholesterol deposits within small arteries; thickened arterial walls | Predispose client to clot formation in lower extremities | |

| Integumentary system | ||

| Decreased subcutaneous tissue and increased fragility of skin | Prone to pressure ulcers and skin tears | |

| Pulmonary system | ||

| Decreased respiratory muscle strength and cough reflex (AORN, 2010) | Increased risk for atelectasis | Instruct client in proper technique for coughing, deep breathing and use of spirometer. Ensure adequate pain control to allow for participation in exercises. |

| Reduced range of movement in diaphragm | Residual capacity (volume of air is left in lung after normal breath) increased, reducing amount of new air brought into lungs with each inspiration | When possible, have client ambulate and sit in chair frequently |

| Stiffened lung tissue and enlarged air spaces | Blood oxygenation reduced | Obtain baseline oxygen saturation; measure throughout perioperative period |

| Renal system | ||

| Decreased renal function, with reduced blood flow to kidneys | Increased risk of shock when blood loss occurs; increased risk for fluid and electrolyte imbalance (AORN, 2010) | For clients hospitalised before surgery, determine baseline urinary output for 24 hours |

| Reduced glomerular filtration rate and excretory times | Limits ability to eliminate drugs or toxic substances | Assess for adverse response to drugs |

| Reduced bladder capacity | Increases the risk for urgency incontinence and urinary tract infections (AORN, 2010) (Sensation of need to void often does not occur until bladder is filled) | |

| Neurological system | ||

| Sensory losses, including reduced tactile sense and increased pain tolerance | Decreased ability to respond to early warning signs of surgical complications | |

| Blunted febrile response during infection (AORN, 2010) | Increased risk of undiagnosed infection | Ensure careful, close monitoring of patient temperature; provide warm blankets; monitor heart function; warm intravenous fluids (AORN, 2010). |

| Decreased reaction time | Confusion and delirium after anaesthesia; increased risk for falls | Allow adequate time to respond, process information and perform tasks. Perform fall risk screening and institute fall precautions. Screen for delirium with validated tools. Orient frequently to reality and surroundings |

| Metabolic system | ||

| Lower basal metabolic rate | Reduced total oxygen consumption | Ensure adequate nutritional intake when diet is resumed, but avoid intake of excess calories |

| Reduced number of red blood cells and haemoglobin levels | Ability to carry adequate oxygen to tissues is reduced | |

| Change in total amounts of body potassium and water volume | Greater risk for fluid or electrolyte imbalance occurs | |

Potter & Perry 2013:1259

Physiological responses

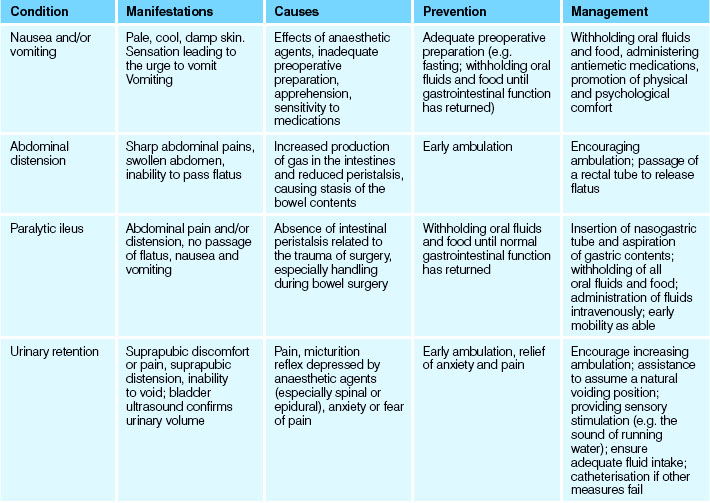

In response to surgical invasion, the body mobilises defences to maintain homeostasis. Most of these mechanisms are generally favourable to survival and healing. If, however, the mechanisms are prolonged or uncontrolled, they may contribute to the development of complications. Table 41.4 outlines the physiological responses to the stress of surgery.

Table 41.4 Physiological responses to the stress of surgery

| Response | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Increased peripheral vasoconstriction and blood coagulation | Prevents excessive blood and fluid loss |

| Increased rate and strength of heart beat, and dilation of the coronary arteries | Maintains cardiac perfusion and oxygenation |

| Increased reabsorption of sodium ions from the kidneys, causing retention of sodium and water | Maintains blood volume, blood pressure and cardiac output |

| Decreased peristalsis in the gastrointestinal tract | Reduces metabolic activity which is non-essential in the short-term emergency |

| Relaxation of smooth muscle that promotes dilation of the bronchioles | Improves gas exchange and tissue oxygenation |

| Increased breakdown of protein | Increases the availability of amino acids for repair of tissues |

| Proliferation of connective tissue | Promotes wound healing |

| Increased circulation of glucose and mobilisation of stored fat | Provides required energy |

| Increased basal metabolic rate | Provides required energy and nutrients for the tissues |

Local responses to tissue injury

After injury, local inflammatory reactions occur to promote healing. A surgical incision, even though created under sterile and controlled conditions, still constitutes injury or insult. The inflammatory response begins with the creation of a surgical wound, and the normal sequence of tissue replacement and wound healing must occur to ensure tissue recovery. The physiology of wound healing involves a specific sequence of events and is discussed in Chapter 27, as are influences on healing, and the specific care of wounds.

Psychological responses

As a result of psychological stress related to surgical intervention, the individual may experience changes in mood and/or behaviour, including:

• Anxiety, which may be related to the procedure itself, or to associated factors, including changed social circumstances, loss of independence or privacy, separation from family/support people, financial hardship or prolonged recovery time

• Fear of anticipated pain, concern of mutilation or decreased function, dread of death, panic of waking up under anaesthetic

• Grief associated with loss of health or a body part, self-image change, altered function or presence of a scar

• Inability to concentrate and/or remember

PREOPERATIVE CARE

The preoperative phase begins when surgical intervention is first considered, and ends when the individual is transferred to the operating table. This phase may be of short duration if the client is taken directly to an operating room from the emergency department or transferred soon after admission to a surgical unit. The duration depends on a number of factors, such as the amount of time required to prepare the client adequately for surgery. The preoperative phase may begin with the individual as an outpatient in a designated pre-admission clinic, where preoperative investigations are undertaken prior to the client’s procedure. In Australia it is now common practice for an individual, depending on the type of surgery to be performed, to be admitted for same-day surgery. In this instance the client is admitted in the early or late morning depending on the time of the operation or procedure. The client is prepared for and undergoes surgery, is recovered from the anaesthetic, is cared for in the day surgery unit (DSU) after the procedure and is discharged home on the same day. Clients undergoing surgery who will require inpatient care are also, in most cases, admitted through the DSU as a day of surgery admission (DOSA). DOSA clients are taken to theatre from the DSU and are taken to the ward from the recovery room. DOSA clients require comprehensive preparation and teaching about home recovery. Follow-up at home (often by telephone) must be available for continuity of care to occur. Day-stay surgery is suitable for less complex surgical procedures, or invasive techniques for which some anaesthesia is required (e.g. endoscopy). These units are staffed by both RNs and ENs.

Clinical Scenario Box 41.1

Elective hysterectomy

Mrs Jones, 45, is an elective category 3 client who is to undergo an open hysterectomy. The surgery has been recommended as she has suffered with increasing blood loss and a lowering of Hb over the last two years, due to fibroids in the uterus.

She will return to the ward with an IDC in situ and a PCA (patient-controlled analgesia) unit.

• What is the longest time Mrs Jones should have waited for her surgery?

• What effect could an extended wait have on her health status?

• Describe some fears or anxiety Mrs Jones may have in regard to her surgery.

• Identify a psychological issue Mrs Jones could face in regard to body image, self esteem.

• What are likely to be the problems and potential problems for Mrs Jones immediately on return to the ward?

• What nursing interventions could be implemented to prevent or reduce these problems?

Day surgery is now well established throughout Australia, in both the public and the private sectors. Currently up to 60% of all procedures are undertaken as day patient procedures. At present, day surgery is widely practised in over 240 freestanding day surgery centres. Many large public hospitals and over 320 private hospitals around Australia have designated DSUs in place (Australian Day Surgery Council 2004). The advantages to the client and their relatives include considerable reduction in cross-infection risk compared with clients who remain in hospital; decreased risk of thromboembolism associated with early ambulation; less anxiety for the client as an overnight stay in hospital is avoided, particularly in the case of children for whom minimal separation from parents is beneficial, and for the older client who may become disorientated when subjected to unfamiliar surroundings for extended periods of time. The client will have a quicker return to normal activities with less time off work, less stress for their relatives, a saving in time, travel and in some cases the need for accommodation to visit an inpatient in hospital (Australian Day Surgery Council 2004; Timmins & McCabe 2009).

Another trend is that overall length of stay in hospital after surgical procedures is decreasing. With this practice of earlier discharge comes the implication that clients may go home with complex medical and nursing needs and will require suitable follow-up with visiting nurses, or involvement in a ‘Hospital in the Home’ or a ‘Rehabilitation in the Home’ program.

The overall aim of preoperative preparation is to ensure that the individual is in the best physical and psychological condition possible before undergoing surgery. It is essential to gather appropriate data concerning the client’s health status through the taking of baseline observations and a detailed and accurate nursing history. Nursing assessment is based on the data collected and includes the identification of actual and potential problems that may be faced by the individual throughout any phases of the perioperative period. Although certain aspects of preoperative preparation are similar for most surgical procedures, other factors are specific, depending on the individual client’s condition and the type of operation to be performed.

Preoperative preparation generally consists of:

• Teaching activities (e.g. deep breathing and coughing techniques and leg exercises)

• Examination of the individual by the anaesthetist and surgeon

• Performing laboratory tests and diagnostic studies

• Gaining the individual’s informed consent

• Preparation of the individual both psychologically and physically.

Providing information

Initial assessment of each client’s knowledge base should be undertaken; even if the person’s past surgical experiences are extensive. The client needs to be informed about all pre- and postoperative procedures and care because knowledge and understanding promote feelings of being in control, and a sense of control helps to relieve anxiety. The information given to clients and, as appropriate, to their significant others should include:

• Preoperative procedures to be performed, and the reasons for them; for example, restriction of food and fluids, cessation of smoking or preparation of the operation site

• Immediate preparation; for example, insertion of an intravenous (IV) cannula, the administration of pre-medication and the induction of anaesthesia, and what sensations may be experienced

• Details of the recovery phase in the postanaesthetic care unit (PACU) before returning to the DSU or the ward

• Postoperative situations to be expected; for example, the presence of an IV infusion or wound drain, and why these are necessary

• Postoperative activities; for example, deep breathing and coughing, early mobilisation and why they are important

• Anticipated pain or discomfort, and options for how this will be managed

• Any additional information specific to the operation to be performed.

The information must be provided in such a way that the individual can understand it, and it should be repeated if necessary. This is essential, as anxiety about hospitalisation and/or the surgical procedure may influence the client’s ability to process and retain information. The most helpful teaching program is designed so that all clients receive the same information.

Teaching activities

Preoperative teaching (see Box 41.1) can help to reduce anxiety and stress, and teaching specific activities that the individual can undertake to promote their own recovery gives them a positive role to play. In some cases the client may visit a specialty postoperative area; that is, an intensive care unit (ICU) as familiarity with environments that will be encountered during or after surgery may help reduce the stress associated with the surgical experience.

• Deep breathing and coughing techniques to facilitate gas exchange and expectoration of accumulated mucus. The client assumes a sitting position and takes several deep breaths followed by a short breath and cough. Alternatively, the client may be taught to take a deep breath, hold it for 2–3 seconds then cough several times while exhaling. The client will be taught to support any wounds with hands, or by splinting with a pillow, to reduce pain and facilitate deep breathing

• Leg exercises performed to stimulate blood circulation and enhance venous return to reduce the risk of a DVT. The client is instructed how to bend the knees and contract the hamstring and quadricep muscles, then to dorsiflex and plantarflex the feet (see Ch 26)

• Moving and changing position helps to prevent complications such as skin breakdown and DVT. The client will be informed of any special equipment, or techniques that will be required for movement, and of any restrictions to movement

Physical examination

The anaesthetist and a medical officer each perform a thorough physical examination of the client. The anaesthetist pays particular attention to the client’s cardiovascular and respiratory systems to evaluate the general level of function and to identify any problems that may cause difficulty during induction or maintenance of anaesthesia, such as an upper airway abnormality, which may make placement of an endotracheal tube difficult, or a spinal condition which may hinder regional anaesthesia. Loose or prosthetic teeth will be identified and noted on the admission chart. The anaesthetist also evaluates possible sites for peripheral or central venous cannulation. After assessing the client, the anaesthetist may prescribe any preoperative medications deemed necessary to be administered prior to surgery.

Laboratory tests and diagnostic studies

Laboratory tests and diagnostic studies help detect any risk factors or possible issues. Specific tests and studies performed depend on the client’s condition and on the nature and complexity of the operation. Ideally, diagnostic tests are carried out with sufficient time before the scheduled procedure to allow for correction of any detected problems.

Tests can include, but are not limited to:

• Blood type and cross-match, for procedures in which significant blood loss is anticipated or possible

• Arterial blood gas and pH, to check respiratory function and oxygenation

• Blood urea nitrogen, to check renal function

• Full blood examination (FBE)

• Prothrombin and/or plasma thromboplastin time, clotting factors, especially if the client has been on anticoagulant therapy

Medical history

Clients will present at the ward for admission, with varied health and illness backgrounds. Some may have chronic illness, others a recent diagnosis that may or may not be related to the reason for this surgical admission. Many existing disorders will have an impact on the client’s recovery from surgery, and surgery may have an impact on the severity or management of the existing disorder. See Table 41.5 for an outline of common medical conditions that may increase the risk of surgery. The nurse needs to be aware of the potential challenges to an optimal recovery for these clients, in order to plan and implement effective care in all phases of the perioperative experience. The nurse also needs to be aware of the effect that the client’s medications for these medical problems may have on their ability to cope with the stresses of surgery and recovery. See Table 41.6.

Table 41.5 Medical conditions that increase the risks of surgery

| Type of condition | Reason for risk |

|---|---|

| Bleeding disorders (thrombocytopenia, haemophilia) | Increase risk of haemorrhaging during and after surgery |

| Diabetes mellitus | Increases susceptibility to infection and impairs wound healing from altered glucose metabolism and associated circulatory impairment. Stress of surgery often causes increase in blood glucose levels |

| Heart disease (recent myocardial infarction, dysrhythmias, congestive heart failure) and peripheral vascular disease | Stress of surgery causes increased demands on myocardium to maintain cardiac output. General anaesthetic agents depress cardiac function |

| Obstructive sleep apnoea | Administration of opioids increases risk of airway obstruction postoperatively. Clients will desaturate as revealed by drop in 0o saturation by pulse oximetry |

| Upper respiratory infection | Increases risk of respiratory complications during anaesthesia (e.g. pneumonia and spasm of laryngeal muscles) |

| Liver disease | Alters metabolism and elimination of drugs administered during surgery and impairs wound healing and clotting time because of alterations in protein metabolism |

| Fever | Predisposes client to fluid and electrolyte imbalances and may indicate underlying infection |

| Chronic respiratory disease (emphysema, bronchitis, asthma) | Reduces client’s means to compensate for acid-base alterations. Anaesthetic agents reduce respiratory function, increasing risk for severe hypoventilation |

| Immunological disorders (leukaemia, acquired immune defciency syndrome (AIDS), bone marrow depression, and use of chemotherapeutic drugs or immunosuppressive agents) | Increase risk of infection and delayed wound healing after surgery |

| Abuse of street drugs | Persons abusing drugs sometimes have underlying disease (HIV, hepatitis) that affects healing |

| Chronic pain | Regular use of pain medications often results in higher tolerance. Increased doses of analgesics are sometimes necessary to achieve postoperative pain control |

HIV, human immunodefciency virus

Potter & Perry 2013:1258

Table 41.6 Medications with special implications for the surgical client

| Drug class | Effects during surgery |

|---|---|

| Antibiotics | Antibiotics potentiate (enhance action of) anaesthetic agents. If taken within 2 weeks before surgery, aminoglycosides (gentamicin, tobramycin, neomycin) may cause mild respiratory depression from depressed neuromuscular transmission |

| Antidysrhythmics | Antidysrhythmics (e.g. beta blockers such as metoprolol (Lopressor)) can reduce cardiac contractility and impair cardiac conduction during anaesthesia |

| Anticoagulants | Anticoagulants, such as warfarin (Coumadin), alter normal clotting factors and thus increase risk of haemorrhaging. Discontinue at least 48 hours before surgery. Aspirin is a commonly used medication that alters clotting mechanisms |

| Anticonvulsants | Long-term use of certain anticonvulsants (e.g. phenytoin (Dilantin) and phenobarbitone) alters metabolism of anaesthetic agents |

| Antihypertensives | Antihypertensives, such as beta blockers and calcium channel blockers, interact with anaesthetic agents to cause bradycardia, hypotension and impaired circulation. They inhibit synthesis and storage of noradrenaline in sympathetic nerve endings |

| Corticosteroids | With prolonged use, corticosteroids, such as prednisone, cause adrenal atrophy, which reduces the body’s ability to withstand stress. Before and during surgery, dosages are often temporarily increased |

| Insulin | Clients’ need for insulin changes after surgery. Stress response and intravenous (IV) administration of glucose solutions often increase dosage requirements after surgery. Decreased nutritional intake often decreases dosage requirements |

| Diuretics | Diuretics such as furosemide (Lasix) potentiate electrolyte imbalances (particularly potassium) after surgery |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | NSAIDs (e.g. ibuprofen) inhibit platelet aggregation and prolong bleeding time, increasing susceptibility to postoperative bleeding |

| Herbal therapies: ginger, ginkgo, ginseng | These herbal therapies have the ability to affect platelet activity and increase susceptibility to postoperative bleeding. Ginseng is reported to increase hypoglycaemia with insulin therapy |

Informed consent

Before an operation is performed, the client must give informed consent which should be freely given without coercion. Informed consent involves the surgeon providing the client with enough information to understand the nature and consequences of the proposed procedure and informing the client about the facts and possible risks relating to the surgery concerned, in terms that ensures understanding by the client. The client then consents, in writing, to have the operation. The surgeon and the client must both sign a consent form, an important part of the documentation process that formalises the client’s agreement to undergo surgery. The nurse is not responsible for obtaining the individual’s consent, but the nursing role includes checking that informed consent has been obtained and making appropriate notifications if this is found not to be the case. In some agencies, nurses are asked to witness consent forms, but the act of witnessing only verifies that this is the person who signed the consent, and that it was given voluntarily. It does not relate to the client’s actual knowledge or understanding of the procedure. (More information on informed consent is provided in Ch 2.)

Psychological preparation

To minimise anxiety and prepare the client psychologically for the proposed procedure, the nurse must ensure that all relevant information is provided. People generally experience anxiety when they are facing the unknown, and anxiety is usually reduced somewhat when accurate and relevant information is supplied. The nurse must ensure that the client and the significant others are given opportunities to ask questions and to express any concerns they may have. It is important for the nurse to recognise that procedures that seem relatively minor or routine may not appear that way to clients or to their significant others. The prospect of any surgical intervention raises many fears about body image alteration, loss of control, pain or even the possibility of death. Some of the many factors that the client may be worried about include:

• What will happen while they are unconscious

• Whether the surgeon will start the operation before the anaesthetic is effective

• Fear of experiencing severe pain

• Who will care for their family or pets

• How long it will be before it is possible to return to work.

The family or significant others may also be worried, especially if the diagnosis is questionable or the outcome of the surgery is difficult to determine. If they choose to remain in the hospital while the operation is being performed, the nurse should ensure that they know where the waiting area is located and where they can obtain refreshments. If they prefer to remain at home they should be given an indication of what the notification process is; for example, if the surgeon will contact them after the procedure and at what time, and whom and when they can call to obtain information.

Providing cultural safety

Providing healthcare, not only for individuals but for members of minority ethnic groups whose care is defined and influenced by social disadvantage, is a concept defined as cultural safety (Hamlin et al 2009).

The traditional values and religious beliefs of members of Indigenous groups in Australia and New Zealand are emphasised in the literature on this concept, also referred to as cultural competence. An example of this is outlined by Hamlin and colleagues (2009) in a case study on a Māori client’s wish to have an amputated limb returned to him and his family for burial, rather than sent for destruction as is the usual practice.

This requirement is not unique to Māori people, so nurses and other healthcare members in the perioperative environment need to be mindful of the policy and procedure for similar cases and be aware that there is usually a system in place for meeting most of the traditional beliefs of many cultures. ‘It is important that nurses display cultural competency in their professional practice’ (Kralik & van Loon 2011). This competency can be evidenced by a sensitivity to varied beliefs and values in all areas of healthcare and a willingness to accommodate these wherever possible.

Another example is the requirement for modesty in Muslim women. There are various degrees of dress requirements while in the presence of other than family males, with some women adopting robes that cover all but the eyes, others allowing only the face to be visible, while most keep limbs covered.

‘The requirement for modesty can affect healthcare as some patients may be reluctant to expose their bodies for examination or to expose areas not directly affected’ (Queensland Health and Islamic Council of Queensland 2010) (see Clinical Interest Box 41.1).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 41.1 Cultural case study

A Muslim woman was admitted to the holding bay of a public hospital prior to undergoing an elective gastroscopy/colonoscopy for diagnostic purposes. She arrived wearing a head covering over her hospital issue gown and a long-sleeved gown over that.

The ward staff indicated that she was unwilling to expose her hair or her limbs in public.

The perioperative nurse was happy for the client to wear her scarf as long as she wore a paper cap over the top to which the client was agreeable.

The (female) anaesthetist was able to reassure the client that she would insert an IV access, for the sedation, into the back of her hand and therefore not expose her arms. The client agreed that, should an emergency occur, she consented to exposure of other areas, like her chest, to allow rescusitation.

Problems occurred when the client realised that she would have to expose her genital area to both the male scout nurse and the male gastroenterologist for the purposes of the colonoscopy. She stated that she expected that female staff only would be present in the theatre.

A female scout nurse was available from another theatre; however, the male gastroenterologist was the only one present on the day. The client refused the procedure and was discharged to return another time when staffing could be arranged to suit.

With knowledge of the likely traditional or religious beliefs affecting some clients, and some forethought, most of these beliefs can be accommodated in the perioperative environment. The responsibility for arranging any accommodations lies with all the stakeholders, from the client to the ward staff and those working in the operating room.

Physical preparation

Ideal surgical conditions include a client who is haemodynamically stable, with no current clinical infection, and with well-controlled preexisting medical conditions. Depending on the individual’s condition and the type of operation to be performed, specific measures may be implemented to minimise or eliminate any identified risks. For example, a client with breathing problems may be required to undergo active therapy such as incentive spirometry (inhalation into a specially designed spirometer, to achieve maximum inspiratory capacity and reduce risk of pulmonary consolidation) or elimination of pulmonary secretions by postural drainage (the use of positioning to drain secretions from specific segments of the lungs). An individual with dehydration or poor nutritional status may be admitted for some time before surgery so that fluid and nutritional deficiencies may be corrected. A specific diet may be prescribed, such as low fibre before bowel surgery. A person with potential for infection may be administered prophylactic antibiotics prior to the operation. Other preoperative measures may include comprehensive preparation of the gastrointestinal tract, and preparation of the skin (see Table 41.7).

Table 41.7 Physical preparation for surgery

| Preparation type | Method and rationale |

|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | Fasting: to empty the stomach and prevent aspiration of stomach contents during anaesthesia. Clients undergoing procedures under local anaesthetic may still be requested to fast in case a general anaesthetic needs to be used. Long-term fasting (over more than 6 hours) will ensure a clear operative view of the internal bowel for open and endoscopic procedures. Fasting status of client ensured by nurse |

| Bowel cleansing: orally taken preparations (Picolax, Fleet) will ensure the bowel is clear for gastrointestinal and some gynaecological procedures. Reduces contamination in open bowel procedures, and allows clear view for colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy. Bowel preparation undertaken by clients at home prior to admission unless an inpatient where the nurse will ensure application of preparation | |

| Enema: may be required for clients suffering from depressed gastrointestinal activity to prevent postoperative constipation | |

| Skin | Shower: clients will be requested to shower before surgery; the nurse will ensure this for inpatient as part of the surgical preparation. Some surgeons require that the shower be performed using antibacterial preparations |

| Removal of hair: clipping, razoring or shaving of hair near the operative site is done as near as possible to the time of surgery, usually in the operating room, to prevent bacterial colonisation due to possible skin scratches. Some authorities state that, unless hair is thick enough to interfere with the surgery, it is preferable to leave it intact. Hair removal is performed by the surgeon, the technician or the nurse | |

| Antiseptic prep: when client is anaesthetised, and prior to draping, the operative site and beyond is painted with an antiseptic skin preparation of the surgeon’s choice. Skin preps may have an aqueous or alcoholic base and are applied by the scrub nurse or the surgeon using sterile gauze pads | |

| Medication | Client’s own: the surgeon or anaesthetist may have temporarily discontinued some or all medications, or adjusted dosages. Otherwise, medications should be given as normal with a minimal amount of water |

| Preoperative: some medications may be ordered for some clients. These may be to reduce anxiety (rarely prescribed), reduce secretions (salivary, gastric, bronchial), open airways (pre-anaesthetic for COPD clients) or to provide local constriction of vessels for haemostasis (ENT cases). The nurse needs to be alert to any medications, such as sedation, that should not be given prior to giving instruction to client, or gaining consent |

Physical preparation may also include cessation or modification of certain medication administration; for example, aspirin and other anticoagulant drugs. Cessation of smoking should also be encouraged.

Preparation of the client immediately prior to surgery

Although preparation during the 1–2 hours preceding an operation may vary slightly depending on the individual and type of operation, preparation generally involves various standard procedures. These include:

• Measuring and documenting height and weight. Knowledge of the individual’s weight (mass) enables drug dosages based on body weight to be calculated accurately. It is also useful for comparison as progress is monitored postoperatively, especially in relation to assessment of fluid balance status

• Measuring and documenting vital signs. Any deviation from previous results must be reported immediately and documented, as abnormalities may result in postponement of the operation. These preoperative measurements serve as a baseline for comparison as the individual’s progress is monitored postoperatively

• Urinalysis, which is generally performed and documented. Any abnormalities must be reported immediately. As the kidneys excrete most drugs from the body, any sign of kidney dysfunction is significant

• Ensuring that the individual is not wearing any nail polish, lipstick, talcum powder or other cosmetics that could interfere with assessment of skin colour (pallor and cyanosis) or circulatory and oxygen saturation status

• Ensuring that jewellery, hairpins, prosthetic devices, spectacles, contact lenses or hearing aids are removed and stored safely. Spectacles and hearing aids are usually worn to the operating room then removed and kept for the client in recovery. Each healthcare agency has its own policy regarding the wearing of wedding rings and earrings; for example, these may be left on and secured in position with adhesive tape. This is to prevent loss of the jewellery or damage to the client if jewellery is caught or dislodged in the course of the surgery

• Whether any dentures or plates are left in the client’s mouth depends largely on the anaesthetist’s instructions. Usually dentures are left in situ, but partial plates or bridges are removed before surgery, as they may be dislodged during endotracheal intubation. It is important to check the presence of any loose teeth for the same reason.

• Attending to general hygiene and comfort needs by ensuring that appropriate clothing is worn and assisting the client to dress if necessary. Generally a plain cotton open-back gown with tie-tapes is worn. A disposable paper cap is also worn to cover the client’s hair, and some facilities also provide disposable paper undergarments worn under the gown.

• Checking that the client’s identification bands (usually two) are correct and in situ. In some agencies a red identification band is worn if the client has any known allergies. It is also important to check all documents that will accompany the client to the operating room.

Documentation

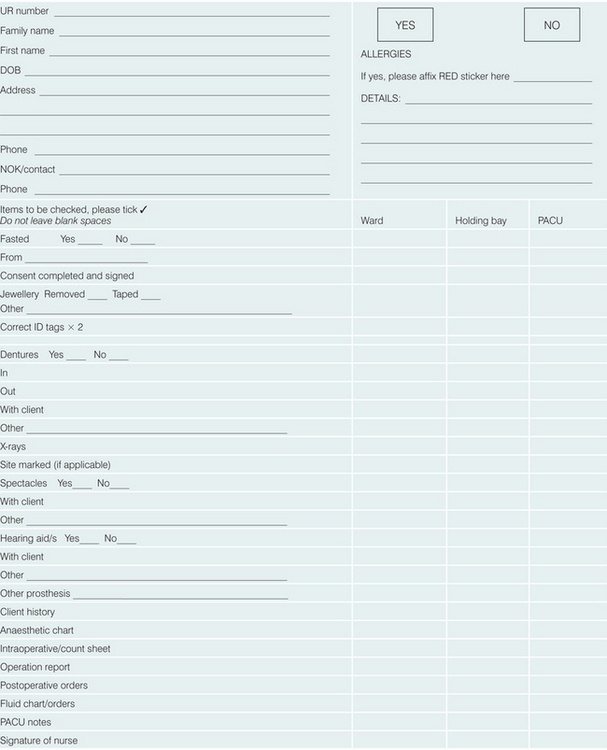

Each healthcare facility has its own preoperative forms and checklist. Usually, these checklists will require checking by the ward nurse, the operating room receiving nurse (holding bay or anaesthetic nurse) and the PACU (recovery room) nurse.

Included for checking on these lists are the other documents that are necessary to remain with the client such as consent form, x-rays, medication charts, postoperative orders and others. See Clinical Interest Box 41.2 for an example of such a checklist and Clinical Interest Box 41.3 for information about paediatric clients in the preoperative environment.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 41.3 Preoperative preparation of paediatric clients

• Young children are usually placed first, where appropriate, on the surgical list for the day, to prevent extended fasting and added anxiety

• Children need to be informed as to what is happening, in lay terms, to the level of the child’s understanding

• Children are encouraged to bring a favourite toy with them to theatre to alleviate some anxiety; the toy may be used to explain procedures and/or have a dressing applied to the same site as the child’s area for surgery

• Waiting time in the holding bay should be as brief as possible

• One parent or guardian is encouraged to accompany the child into the theatre to provide support until anaesthetised

• Where possible, if a child is traumatised by the prospect of IV insertion, the child may initially receive a gas induction, with IV insertion done when unconscious

• To alleviate distress it is helpful to have a parent or guardian waiting to be called to PACU to be present when the child wakes

• Young children and babies can usually have food or drink as soon as they are awake after a minor procedure. A distressed baby will usually settle well with a bottle upon awakening

• Children should be recovered in PACU in an area precluding a view of other, adult clients who may have had major surgeries

INTRAOPERATIVE PHASE

Perioperative nurses undertake a variety of roles within the operating suite. These include circulating (scout) nurse, instrument (scrub) nurse, anaesthetic nurse and recovery room (PACU) nurse (see Table 41.1). The circulating nurse is responsible for the documentation and management of all accountable items opened onto the sterile field. The scout supports the instrument nurse by being aware of the requirements of the surgical team and makes certain all supplies are deposited on to the surgical field aseptically. The circulating nurse performs the surgical count with the instrument nurse, and undertakes other responsibilities including client positioning, client safety issues, specimen collection, provision of equipment and being the communication link between theatre staff and those outside. The role of circulating or instrument nurse may be undertaken by an EN or RN. The instrument nurse is the one who assumes primary responsibility and accountability for all items used during the surgical procedure. The instrument nurse sets up all sterile instruments and supplies, and hands instruments to the operating team anticipating their needs. Nursing practices and interventions in the intraoperative phase also include establishing personal contact and supporting the client emotionally in the highly technical environment of the operating room. Protocols relating to the promotion of individual safety are another area of paramount importance, as during surgery, and particularly under anaesthesia, clients are unable to protect themselves from many sources of possible harm.

All personnel who enter the theatre complex wear clean scrub outfits, hair covers and shoe covers, with additional sterile gowns, gloves, masks and eye protection during procedures. Strict surgical asepsis is mandatory throughout the surgical area, and all persons in the operating room must be alert to possible contamination of sterile items. Staff must consider their responsibilities in relation to the spread of infection and restrict or modify working if they have an upper respiratory or skin infection (ACORN 2010). (See Ch 20 for further information on the control and prevention of infection, surgical scrub and surgical asepsis.)

Anaesthetic and PACU nurses are often referred to as perianaesthesia nurses. The anaesthetic nurse provides primary support to the anaesthetist and the client immediately prior to the surgical procedure by carrying out client assessment and preparation, assists the anaesthetist during intubation and the administration of the anaesthetic, helps during the operation and assists with waking the client from the anaesthetic. The anaesthetic nurse works under the direct supervision of the anaesthetist and is responsible for the preparation of the required equipment, monitoring and pharmacology. Immediately following the procedure the client is transferred to the PACU where they are cared for by the PACU/recovery room nurse. The PACU nurse is responsible for airway assessment and management, client observations, identification and prompt correct action in case of surgical or anaesthetic complications. Postoperative pain and nausea management, accurate documentation of care and administration of medication as ordered are also roles of the PACU nurse. All these roles work collaboratively, with the individual roles dependent upon each other to work as a multidisciplinary team that aims to provide evidence-based best practice and optimal client outcomes (ACORN 2010).

The anaesthetic nurse will notify the DSU or the ward that theatre is ready for the client. The client is brought to a preoperative holding bay or anaesthetic room where it is identified that they are the correct client, any allergies are highlighted, fasting status is determined and the consent form is checked. The anaesthetist will insert an intravenous (IV) cannula and may give the client some medication to relax them; they are then transferred into the operating room and onto the operating table. ECG, blood pressure and oxygen saturation monitoring is applied, the client is positioned, padding to prevent injury to nerves and to minimise pressure over bony prominences is strategically placed and safety straps secured to maintain the client’s position. Draping and preparation for surgery commences, ensuring the correct operation site is prepared.

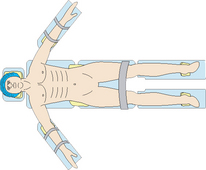

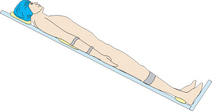

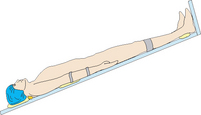

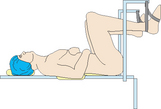

It is important that the client is correctly positioned according to the procedure being performed. Surgical positioning is an activity commonly performed by the technician, anaesthetic nurse, circulating nurse and, often, the surgeon and anaesthetist to ensure that the position is appropriate for the procedure, and safe for the client. Common positions used for surgery with potential risks outlined are illustrated in Table 41.8.

Table 41.8 Common positions for surgery

| Position | Possible surgical procedures/rationale | Pressure risks and other health and safety concerns |

|---|---|---|

Supine  |

||

Lateral  |

Elbows, hip, knees and ankles. Gel pads required, with pillow/gel pad placed between knees. Padded back support and padded straps required to keep in position. Risk of movement/fall if not secured properly, risk of injury from metal supports if not padded/covered | |

Reverse Trendelenberg  |

||

Trendelenberg  |

||

Prone  |

||

Lithotomy  |

Induction of anaesthesia

In most cases, an operative procedure requires some degree and type of anaesthesia, but not all procedures require a full general anaesthetic. There are different means by which anaesthesia can be achieved. Factors influencing the choice of anaesthetic include the nature of the surgery (length and complexity of operation), the client’s status (preexisting medical conditions), anatomical and physiological conditions and, to some degree, client preference. Anaesthetics can be classified as general anaesthetics, regional anaesthetics and local anaesthetics.

General anaesthetic

General anaesthesia promotes unconsciousness, absence of sensation, loss of reflexes and muscle relaxation. Administration is primarily by IV injection, inhalation or a combination of both. The four components of general anaesthesia are amnesia, analgesia, muscle relaxation and unconsciousness. Ventilation during general anaesthetic is separated into spontaneous or controlled. Clients whose ventilation is controlled have usually been administered muscle relaxants.

The three phases of general anaesthetic are induction, maintenance and emergence:

1. Induction—begins when the anaesthetic agents are administered and ends when the client is ready for positioning, prepping or incision. Intubation occurs during this phase

2. Maintenance—continues from the end point of induction until the procedure is nearly complete. This phase is sustained with titrated doses or continuous infusion of IV drugs, or inhalation of anaesthetic gas

3. Emergence—begins when the individual starts to emerge from anaesthesia and ceases when the client is ready to be transferred from the operating room to PACU. Extubation is usually carried out during emergence.

Regional anaesthetic

Regional anaesthesia is a form of local anaesthesia; it results in loss of sensation to an area, by blocking the conduction of nerve impulses to and from specific sites in the body. The anaesthetist injects an anaesthetic agent around nerves, thereby anaesthetising the area those nerves supply. The effect is dependent on the type of nerve concerned. Sensory (pain) nerves are more readily blocked than motor nerves, so some movement may remain. With these methods of anaesthesia the client is often awake during the procedure, but the area targeted for surgery is without sensation.

With regional anaesthesia there is no loss of consciousness, therefore considerations should be made for the fact that the client can still feel pressure and hear sound. The nurse must be sensitive that the environment is quiet and therapeutic, with no unnecessary conversation about the client, their diagnosis or the procedure being performed. Dependent on the operation being performed the anaesthetist may administer mild sedation to relieve anxiety or dull the individual’s awareness of their surroundings. Regional anaesthesia is administered by infiltration and local application, including:

• Spinal (intrathecal) anaesthesia: an injection of local anaesthetic into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) within the subarachnoid space at the lumbar level. The extent of anaesthesia can be from the xiphoid process down to the feet. Spinal anaesthesia is frequently used for surgical obstetrics, lower extremity, lower pelvic and lower abdominal procedures

• Epidural anaesthesia: local anaesthetic is injected into the epidural space, via an inserted catheter allowing a continuous infusion or intermittent boluses to be delivered. Epidural anaesthesia is frequently used in obstetric procedures and for postoperative pain relief

• Caudal block anaesthesia: injection of a local anaesthetic into the caudal (sacral) portion of the spinal canal

• Peripheral nerve block anaesthesia: injection of a local anaesthetic into a specific site, such as the brachial plexus, to block a group of sensory nerve fibres.

Local infiltration

Local infiltration anaesthesia is the injection of an anaesthetic solution into the tissues at the incision site. Loss of sensation occurs at a targeted site; for example, a skin lesion or a wound requiring sutures. Local anaesthesia is commonly used for minor procedures in DSUs or consultants’ surgeries. Surgeons may infiltrate local anaesthetic to an operative area to enhance postoperative pain relief.

Anaesthetic agents may also be applied topically, as a cream, spray or drops applied to the skin or mucous membranes. Common local anaesthetic agents for infiltration, injection or for topical use include lignocaine, bupivacaine and procaine (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Safe surgery

Universal protocol

To ensure that clients receive the correct operation on the correct site at all times, checkpoints and checklists are in place. The World Health Organization has adopted a three-step process called the Universal Protocol to be used to prevent error (Joint Commission 2003) (see Procedural Guideline 41.1).

Procedural Guideline 41.1 Safe surgery

(World Health Organization 2009)

Count protocol

The counting of surgical instruments and other accountable items is a practice that has changed vastly in fairly recent times. While some agencies may have variations on a theme, it is desirable that they follow the guidelines set out in the ACORN Standards. Standard S3: Counting of Accountable Items Used during Surgery (2010) sets out step-by-step procedures related to counting items and dealing with incorrect count situations. Included in this standard are recommendations that those who document the addition of an item, or insertion of an item, are also responsible for ensuring the removal, or out-counting of said item. It also recommends that, in the event of an incorrect count, the client remain in theatre, under anaesthesia if possible, until the count is correct. This may need to be determined with the use of x-ray to either confirm or totally disprove the presence of an accountable item left in the client. This standard, along with agency-led protocols, are designed to prevent scenarios such as those set out in Clinical Scenario Box 41.2.

Clinical Scenario Box 41.2

Incorrect count procedures

A client who underwent a septoplasty procedure had a throat pack inserted by the anaesthetist which was documented on the intraoperative count record by the nursing staff. The anaesthetist did not record that the throat pack was inserted. The pack was not documented as being removed at the final count. Neither the instrument nurse nor the circulating nurse checked to confirm removal.

When the client arrived in the postanaesthetic recovery unit the anaesthetist was questioned by the circulating nurse as to whether he had remembered to remove the throat pack—he had not. The client was checked immediately. The client was questioned by the anaesthetist whether they felt any discomfort in the throat and replied that no discomfort was felt. When a visual check was done there were no signs indicating the presence of the pack. The client had no respiratory distress at this time and was quite comfortable. The situation was explained fully to the client and their family. The client had their throat x-rayed but no pack was observed, so an upper abdominal x-ray was ordered and it revealed the pack in the client’s stomach. The pack was removed via gastroscopy (Department of Human Services 2008a).

What procedure was not followed to allow this event to occur?

• Whose responsibility was it to ensure removal of the pack was documented?

• Whose responsibility was it to check the documentation before the client was sent to PACU?

A client underwent a laparotomy for ulcerative colitis surgery. During the skin closure it was identified by the instrument nurse that an artery forcep was missing. The nurse told the circulating nurse and other members of the surgical team. A thorough search of the operating room environment failed to find the instrument. Subsequently an x-ray was taken in the postanaesthetic recovery unit where the artery forcep was revealed in the abdominal cavity. The client was returned to the operating room where the artery forcep was retrieved (Department of Human Services 2008b).

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

After completion of the operation the client is transferred to PACU, which is located within the operating theatre complex. The client is accompanied by the anaesthetist who will hand over to the PACU nurse the client’s general condition, the operation performed and the type of anaesthesia used for the procedure and any complications encountered during the surgery and anaesthesia. Immediate assessment of the client’s airway, heart rate, respirations, temperature and oxygen saturations are performed and recorded and blood loss is noted. Once these initial observations have been made it is essential to systematically assess the client, either head to toe or by systems: central nervous system (CNS), cardiovascular system (CVS), respiratory system (Resp), gastrointestinal tract (GIT), urinary function, wounds, drain tubes, fluid management, skin integrity and pallor. The client is not transferred back to the ward until fully awake, conscious and alert, motor and sensory functions have begun to return, vital signs are stable, pain is controlled and there are no immediate complications from the anaesthetic or surgery. A verbal handover is given by recovery room staff to day-surgery or ward staff receiving the client, including any allergies, anaesthetic, analgesic and antiemetic drugs administered, details of the procedure, postoperative orders, as well as any other information relating to the client’s condition.

Preparation of the client’s day surgery or ward environment

While a client is in the operating suite, the day surgery or ward nurse prepares the client’s bed area ready for their return. As discussed earlier, in many agencies it is common practice for clients to be transferred to theatre on their beds. The remaining linen, including the top bedclothes, are folded into a pack and stored in the bed area, which enables them to be unfolded over the client quickly and with minimal disruption on return to the ward. Generally, one pillow is placed at the head of the bed, and the remaining pillows are placed in a convenient location in the room (see Ch 21 for more information on making an operation or surgical bed). If the client is a day surgery client they will return to the DSU on a trolley. The furniture in the room should be arranged to provide easy access for equipment; for example, the bed may be positioned away from the wall, and the over-bed table and locker should be positioned away from the bedside. The equipment required in the room will depend on the type of operation that was performed, but generally includes:

Immediate general postoperative care and assessment

When clients are transferred back to the DSU or the ward, an appropriate position is selected depending on their condition and the type of operation. Initially, this is often a lateral position, to promote a clear airway while the client is still recovering from the anaesthetic (see Ch 21). The upper bedclothes are placed over the client to promote maintenance of body temperature and comfort. If an IV infusion is in progress, the bag of solution is suspended on a pole or stand, and the infusion is assessed to determine whether it is flowing at the prescribed rate. The client’s arm, in which the IV cannula is inserted, is positioned so that there is no obstruction to the tubing. Any drainage bags, such as urinary or wound-drainage bags, are placed in a holder or hanger and positioned to facilitate drainage by gravity.

Early postoperative assessment of the client involves monitoring and documenting:

• Level of consciousness—although some drowsiness and disorientation is normal after a general anaesthetic, it should be possible to rouse the individual by verbal stimuli or touch. Orientation to person, place and time gradually return. Inability to rouse the individual should be reported immediately. After local or regional anaesthesia, it is important to monitor for the return of normal sensation and movement to the anaesthetised area. Generalised restlessness should also be reported, as it may be due to a change in the level of consciousness; or may be associated with pain, discomfort, respiratory difficulties or haemorrhage. It is important during the early postoperative phase that details of the client’s condition and diagnosis should not be inappropriately discussed, as the client may be able to hear, even if not fully awake

• Colour—report any significant changes to the individual skin colour (extremely pale or cyanosed)

• Vital signs—any deviation from previous readings of temperature, pulse, respirations, oxygen saturation or blood pressure is reported immediately. If ordered, oxygen therapy is administered and monitored

• Presence of discomfort or pain—as individuals recover from the effects of anaesthetic, they may begin to feel pain. The level of pain experienced may vary according to the type of anaesthesia used; for example, after a spinal anaesthetic the operative area may still feel relatively numb until several hours after the procedure. The presence of any discomfort or pain must be assessed and reported immediately so that appropriate pain-relieving measures can be implemented

• Wound dressing—in the immediate postoperative period, assessing for haemorrhage is a major responsibility of the nurse. Both the dressing and the bed linen under the client should be checked for evidence of haemorrhage; an increase in blood staining on the dressing, or a sudden increase of blood in a drainage tube or bag, must be reported immediately. Body cavities that have had a surgical pack inserted (nasal or vaginal packs) also require close observation

• Urinary catheters—if the client has an indwelling catheter, the nurse must monitor the urinary output carefully. Absence of, or decreased amount of, urinary output must be reported; similarly, any unexpected presence of blood in the urine needs to be documented and reported. (See Table 41.9 for a quick reference guide to immediate care.)

Table 41.9 Immediate general postoperative care and assessment

| ABC | Level of consciousness |

| Recovery position or semi-Fowler’s unless otherwise ordered | |

| Airway support—check laryngeal mask in situ/Guedel airway | |

| Oxygen applied via LMA or Hudson mask | |

| Note colour, warmth of skin | |

| Document on arrival then at 10-minute intervals | |

| Vital signs | Automatic monitoring, BR HR, 0. sats, ECG |

| Temperature—require warm air blanket? | |

| Note reportable rates (on anaesthetic chart or postop orders) | |

| Document on arrival then at 10-minute intervals | |

| Wound/s | Dressing dry and intact |

| Change/support dressing as required | |

| Document on arrival then at 10-minute intervals | |

| Drains | Wound drainage, amount, consistency |

| Tubes unkinked, bottle attached to bed | |

| Patency of drain bottles/on suction? | |

| Indwelling urinary catheter—amount and colour | |

| IDC tube unkinked, bag attached to bed | |

| Document on arrival then at 10-minute intervals | |

| IV | Gravity feed or pump |

| Correct fluid/orders | |

| Infusion on correct rate | |

| Document on arrival and when required for change | |

| Pain | Start any ordered opioid analgesia infusion when conscious state allows |

| Pain assessment/scale | |

| Ensure adequate analgesia orders | |

| Position to enhance comfort | |

| Document on arrival and when required for change |

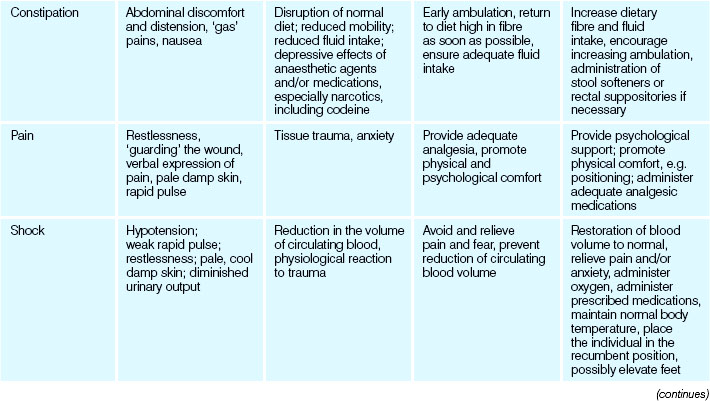

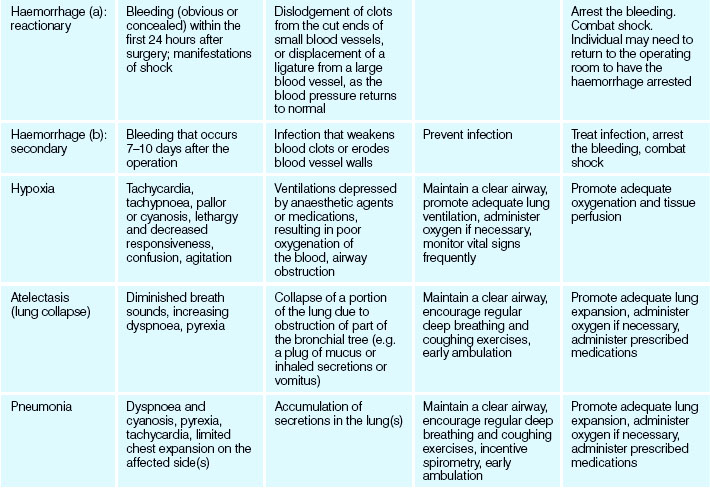

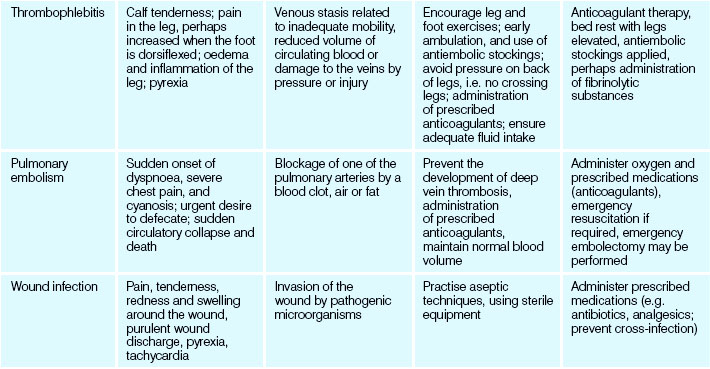

Subsequent postoperative care

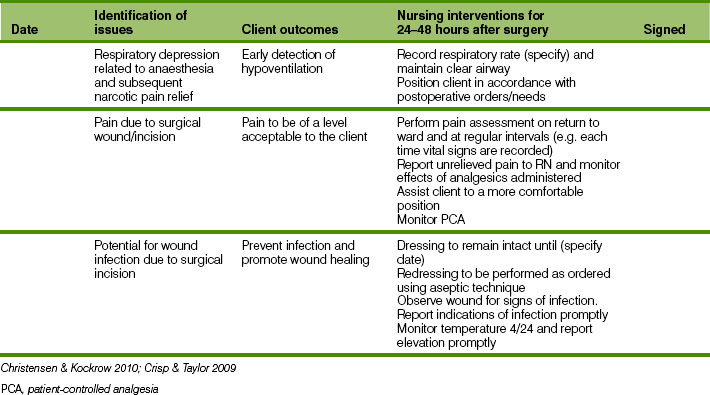

The overall aim of the postoperative nursing phase is the return of the individual to an optimal level of functioning and independence. Postoperative care is directed towards assisting the client to meet specific needs for oxygenation and circulation of blood, comfort, nutrition and fluids, elimination, movement and exercise, hygiene, psychological support, protection and safety. Nursing Care Plan 41.1 identifies the importance of continuously assessing vital signs and the need for early frequent detection of postoperative complications.

Assessing respiratory and circulatory needs

In the initial postoperative period, the frequency with which the individual’s vital signs are monitored depends on their condition. Generally, vital signs are assessed and documented every 30 minutes for the first 4 hours, then 1 hourly for 4 hours, then every 2–4 hours if the condition is satisfactory. If the client’s condition is unstable, observations may be monitored more frequently for a longer period of time. (See Ch 18 for the early warning signs indicating a deteriorating client.) Assessment is also made of colour and breathing to observe for the signs of any respiratory tract complications. Mucus secretions can accumulate, leading to pneumonia, bronchitis or atelectasis. Throughout the postoperative recovery, the individual is also at risk of thrombophlebitis and pulmonary embolus. During this period deep breathing, coughing and, if possible, leg exercises and early ambulation are encouraged to decrease the possibility of the above complications occurring.

Comfort needs

Client comfort can be promoted by ensuring that a suitable position is assumed. Unless contraindicated, the individual is encouraged and assisted to assume a semi-upright position. This position promotes adequate lung expansion, and assists urinary or wound drainage by gravity. Pillows are arranged to provide adequate support, without restricting movement. If the client is unable to move independently, the nurse must assist the client to change position every 2 to 4 hours. Regular administration of analgesia and assessment of pain levels, the prevention of nausea, tension on the surgical wound and bladder distension will all help to provide client comfort. With adequate comfort and pain relief the individual is able to rest and perform postoperative activities and exercises, all of which act to enhance recovery.

Nutritional and fluid needs

Because of the effects of stress and general anaesthesia on the gastrointestinal tract, in the initial postoperative period the individual may experience nausea and/or vomiting and be unable to tolerate oral fluids or food. Food and fluids are generally withheld until normal gastrointestinal functioning has returned, as made evident by the presence of bowel sounds and the passing of flatus. Until this has occurred, the individual receives fluids and nutrients intravenously. In some instances eating and drinking are contraindicated for an extended period, or the individual may require extensive nutritive therapy to rebuild tissue after the trauma of surgery. In such cases, hyperalimentation using parenteral nutrition may be indicated (Ch 30). Depending on the procedure and anaesthetic used, some clients may be able to tolerate sips of fluid within a short time. If sips of fluid are tolerated, and there are no contraindications, clients progress to free fluids, then to a normal diet. Day surgery clients are encouraged to eat and drink once they are fully awake and can tolerate sips of water.

Elimination needs

Generally, early ambulation and the intake of adequate fluids stimulates micturition. Some individuals may experience difficulty in passing urine; for example, due to pain or the embarrassment or difficulty of having to use a bedpan or urinal. It is important to observe urinary output on an ongoing basis. If retention of urine or inadequate emptying of the bladder occurs, it may be necessary for the client to have a urinary catheter inserted. The need for catheter insertion is based on data collected using bladder scanning techniques, and medical orders following consultation. To re-establish normal bowel function the client is encouraged to ambulate as soon as possible and to consume adequate fluids and dietary fibre, although, as described above, oral fluids and food are initially withheld until normal intestinal peristalsis returns.

Movement and exercise needs

Postoperative exercises are started soon after the client’s return to the ward. The nurse should encourage deep breathing and coughing and leg exercises to be performed at 2- to 4-hourly intervals. These exercises are best continued until the individual is fully ambulant. Mobility and activity are gradually increased as the person’s condition improves. Initially, postural hypotension and dizziness may be experienced when getting out of bed. Allowing the client to gradually raise their head position, then sit on the edge of the bed and dangle their legs, then after a few minutes assisting them to get out of bed slowly, generally reduces these symptoms (Christensen & Kockrow 2010). The individual should be encouraged to ambulate a little more each day and should be informed of the benefits of ambulation.

• Facilitates deep breathing and so prevents respiratory complications

• Stimulates the circulation of blood, thus preventing vascular complications

• Improves muscle tone and strength

• Aids in the elimination of waste from the bladder and bowel

• Reduces the risk of skin breakdown and decubitus ulcer formation

Hygiene needs

Until the individual is able to fully attend to their own personal hygiene needs, the nurse assists. Once the client has recovered from the major effects of the anaesthetic, the face and hands are washed, hair is brushed and mouth care provided. The client is assisted to get dressed into their own nightwear, and any soiled or damp bed linen is changed. In the initial postoperative period when the client is not having any oral fluids, frequent mouth care should be provided preventing dryness, soreness or cracking of the tongue and lips. When able, the client is encouraged to resume responsibility for personal hygiene needs. The nurse may be required to assist with a shower or bath and should be available to supervise activities to promote safety.

Psychological needs

Psychological support is provided by keeping the client informed, allowing expression of concerns about progress, change of body image, impact of surgery on lifestyle; and by encouraging visits from family and friends. Self-esteem is enhanced with increasing independence and should be encouraged; by allowing resumption of responsibility for own personal care, without endangering safety or recovery, the client may feel more empowered. Whenever possible, the client should be given a choice in care and in timing of activities and events. It is important that the client understands the expected time-scale to full recovery and how any problems will be managed should they arise. All procedures and activities and their rationales should be fully explained. The nurse may need to help the client and significant others to develop effective coping strategies. Coping methods may include:

• Obtaining additional information to deal with a situation more effectively

• Trying out various ways of solving a problem, to see which one is most helpful

• Talking over a problem with someone who has been in a similar situation

• Engaging in an activity that is relaxing and of interest, such as reading or listening to music.

Protection and safety needs

In the postoperative period the nurse must implement measures to protect the client from hazards in the environment. This is essential both initially, when conscious state may still be compromised and the ability to respond is diminished, and later, when changes in function may require individual adjustments when carrying out activities of daily living.

Wound care

Care of a surgical wound is directed towards promoting healing and preventing infection. Chapter 27 provides in-depth information on general wound healing and management; in this chapter we discuss specific wound management for surgical wounds.

Wounds are described as healing by first, second or third intention:

• First intention healing occurs when wound edges are brought together; for example, a sutured surgical incision. Granulation tissue is not obvious

• Second intention healing occurs when wound edges cannot be brought together; for example, a gaping wound. Granulation tissue fills in the wound until re-epithelialisation takes place and a large scar results

• Third intention healing occurs when wound closure is delayed for a few days so that an infected or contaminated wound can be debrided. Closure of contaminated wounds is usually delayed until all layers of wound tissue appear healthy, usually within 4–10 days.

Influences on wound healing

Healing is governed not only by the condition of a wound itself, but also by factors intrinsic to the individual, pertaining to the health status of the individual. External factors may also contribute to delayed wound healing, or failure of a suture line. Table 41.10 sets out some internal and external factors that create risk for optimal, timely wound healing.

Table 41.10 Influences on wound healing

| Infuencing factor | Intrinsic/internal | Extrinsic/external |

|---|---|---|

| Position of wound | Excessive strain on the incision resulting from inappropriate or over-activity | |

| Condition of wound | Infection, pus or dead tissue present will inhibit complete healing | Dressing treatment, hygiene measures |

| Nutritional status | Lack of adequate intake of required nutrients, including vitamins, and adequate hydration will delay or prevent complete healing | |

| Blood circulation | Poor circulation reduces the supply of oxygen and nutrients necessary for healing to the site | Restrictive dressings, plaster casts, positioning of wound site |

| Immune status | Advanced age, autoimmune disorders or drugs, other disorders, e.g. diabetes | Proximity to other contagious clients Infection control measures |

Crisp & Taylor 2009; Marieb 2011

Wound healing generally takes place within 7–10 days, although the time for normal healing depends on several factors:

Promotion of healing

To promote healing, a range of general measures may be implemented. These include:

• Maintenance of adequate nutritional status. Provision of a diet that contains adequate kilojoules, protein, vitamins C and A, iron and zinc

• Promoting adequate oxygenation of the tissues. Deep breathing and coughing exercises and early ambulation to promote full lung expansion will enhance oxygenation of the blood

• Encouraging adequate blood circulation to the area, promoting transport of substances required for healing and combating infection. Adequate blood volume can be maintained by ensuring sufficient fluid intake and a suitable level of exercise and mobility can stimulate circulation

• Restricting movement of the area in the early stages of healing. If strain is placed on a wound, the newly formed granulation tissue may tear. The surgical wound area should be stabilised, rested and supported.

Wound management

Surgical wounds are covered with specific dressings when the client returns to the ward. These dressings are usually left intact until the client is reviewed by the surgeon. If leakage appears on the original dressing it is important to reinforce the dressing and report and document the leakage immediately. If wound drainage is present and copious and potential exists for skin excoriation, a drainage bag or pouch may be placed over the wound to protect the skin. Before application of the pouch, an adhesive skin barrier such as a pectin wafer is placed on the surrounding skin. The pouch is placed over the draining area and secured to the barrier using gentle digital pressure. The principles of application and care relevant to a wound drainage pouch are similar to those that apply to stomal appliances. Several factors must be considered in the selection of surgical dressings, such as the client’s skin condition, allergies, the type and site of the wound, the amount of wound exudate and the availability of various dressings.

Dressing changes