Chapter Two Critical thinking in health assessment

Ellen K. is a 23-year-old unemployed female who entered a substance abuse treatment program because of numerous drug-related driving offences (Fig 2.1).

After her admission, the nurse collected a health history and performed a complete physical examination. The actual preliminary list of significant findings looked like this:

• High school academic record strong (A−/B+) in first 3 years, grades fell in final year but did complete high school

• Alcohol abuse, started age 16, heavy daily usage × 3 years prior to admission, last drink 4 days ago

• Smoked 2 packs per day × 2 years, prior use 1 pack per day × 4 years

• Diminished breath sounds, with moderate expiratory wheeze and scattered crackles at both bases

• Resolving haematoma, 2 to 3 cm, R (right) infraorbital ridge

• Missing R lower first molar, gums receding on lower incisors, multiple dark spots on all teeth

• Well-healed scar, 28 cm long × 2 cm wide, R lower leg, with R leg 3 cm shorter than L (left), sequela of car accident age 12

• Omits breakfast, daily food intake does not include fruit or vegetables, eats meals at fast food restaurants most days

• Unemployed × 6 months, previous work in a supermarket and hotel

• History of physically abusive relationship with boyfriend, today has orbital haematoma as a result of being hit; states, ‘It’s OK, I probably deserved it’

• History of sexual abuse by father when Ellen was 12 to 16 years of age

• Relationships—estranged from parents, no close women friends, only significant relationship is with boyfriend of 2 years whom Ellen describes as physically abusive and alcoholic.

The nurse analysed and interpreted all the data; clustered the information, identified the main health issues or problems for Ellen and sorted out which issue to refer and which to treat. Although the diagnostic process is discussed later, it is interesting now to note how many significant findings are derived from data the nurse collected. All of the assessment data is important when considering Ellen’s state of health. The findings are interesting when considered from a life cycle perspective; that is, Ellen is a young adult who normally should be concerned with the developmental tasks of emancipation from parents, building an independent lifestyle, establishing a vocation and choosing a mate (see Ch 3). The findings are also interesting when considered from a quality and safety perspective. For example, what symptoms is Ellen experiencing? What risks are there for Ellen? What is the impact on her physical, psychological or spiritual function? For a person to receive quality and safe care, symptoms, risk and function must be fully investigated and managed.

The registered nurse provides evidence-based nursing care for people of varying ages, experiencing physical or mental illness in a range of clinical contexts. Nursing care is aimed at promoting and maintaining health and preventing illness; that is, it is focused on outcomes. Nurses work collaboratively with healthcare team members to help the person/family/community meet their health outcomes. Regardless of role or context of care, nurses are responsible and accountable for making clinical decisions as part of their role in patient/client care delivery (Australian Nursing & Midwifery Accreditation Council, 2010; Nursing Council of New Zealand, 2007).

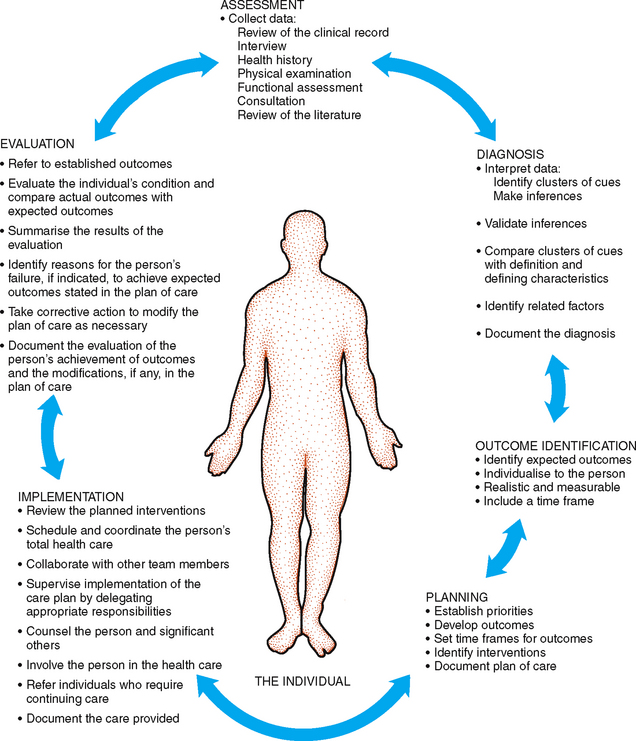

Critical thinking, clinical reasoning, diagnostic reasoning, problem solving, clinical judgment and clinical decision making are terms that tend to be used interchangeably. As outlined in Chapter 1, assessment is the ongoing collection of data about an individual’s health state. Collecting data is not enough, however. Clinical decision making is a process with which the nurse decides which data should be collected and does so using a range of sources that includes the person, their past medical and nursing history and which may also include laboratory test results and information provided by family. All of this information is organised and critical thinking is used to find meaning or form a clinical impression. More assessment may follow to identify patient/client problems or needs. Assessment data is then used to help improve the person’s situation through the nurse’s clinical judgments and clinical decisions. Following data collection, the nurse judges the quality of evidence available to inform the selection of the most appropriate interventions. Consideration is also given to the context, availability of resources, preference of the person and level of expertise of the nurse. Finally, the effectiveness of nursing interventions is evaluated in terms of achievement or non-achievement of patient outcomes.

Clinical decision making is a continuous process commencing on the first patient/client/nurse encounter as the nurse plans, implements and evaluates care. Whether the patient/client’s situation is stable or rapidly changing, the nurse’s decisions affect patient outcomes. Clinical decision making is underpinned by the nurse’s knowledge and level of experience. To ensure the effectiveness and appropriateness of clinical decisions there are a number of clinical tools, clinical guidelines, hospital/agency policies and protocols and best practice resources available to support the nurse’s clinical decision making. Use of these resources will ensure the safety of all patients. There are a number of indicators of quality and safe patient care of which the incidence of medication error, infection, falls, pressure injuries and unrelieved pain are specifically relevant to nursing (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2010). Throughout this text a range of assessment tools are referred to.

You need to be clear about the purpose of health assessment in your context as this will direct what information you collect, the time frame and frequency of assessment and what you do with the information. For example, in an acute care context you need to be clear about the person’s reasons for admission, the medical plan, the patient trajectory and the role of the multidisciplinary healthcare team. This knowledge will assist you to determine the type of assessment data required, the frequency of assessment and what should be done with this information.

CRITICAL THINKING AND CLINICAL DECISION MAKING

Because all healthcare treatments and decisions are based on the data you gather during assessment, it is paramount that your assessment be factual and complete. The way in which nurses make clinical decisions depends on level and time of experience. The novice nurse has no experience with a specified patient population and uses rules to guide performance (Benner, Tanner, Chesla, 1996). It takes time, perhaps 2–3 years in similar clinical situations, to achieve competency, where the nurse sees actions in the context of goals or daily plans for patients. With more time and experience, the proficient nurse understands a patient’s situation as a whole rather than as a list of tasks. This nurse sees long-term goals for the patient and how today’s nursing actions apply to the point the nurse wants the patient to be in, say, 6 weeks. Finally, it seems that expert nurses jump over the steps and arrive at a clinical decision or judgment in one leap. The expert nurse has an intuitive grasp of a clinical situation and zeroes in on the accurate solution (Benner et al, 1996).

The way to move from novice to expert practitioner is through the use of critical thinking. We all start as novices who need the familiarity of clear-cut rules to guide actions. Critical thinking is the means by which we learn to assess and modify, if indicated, before acting. Critical thinking is required for sound diagnostic reasoning and clinical judgment. During your career, you will need to sort through vast amounts of data and information in order to make sound judgments to manage patient care. This data will be dynamic, unpredictable and ever changing. There will not be any one protocol you can memorise that will apply to every situation. This is true particularly with expert nurses in critical care situations in which patient status changes rapidly and accurate decisions are paramount. The stakes are high, and nursing autonomy is strong. In these cases, the expert focuses on patient responses and prevents complications through anticipation and vigilant monitoring (Hoffman, Aitken, Duffield, 2009). The expert has well-developed observational skills and trusts their physical assessment skills, even if this conflicts with technologically driven data.

In a study of decision making conducted by Hoffman et al (2009) novice nurses in an intensive care unit were found to have a reactive rather than proactive approach to decision making. Novices noticed fewer cues than expert nurses and were less aware of the importance of some cues. On the other hand, expert nurses gathered more meaningful clusters of assessment data and, when they combined these with their knowledge of illness patterns, were found to anticipate patient problems and thus benefit patient planning to prevent health problems (Hoffman et al, 2009). Compare the actions of the non-expert and the expert nurse in the following situation of a young man with Pneumocystis jiroveci (P. carinii) pneumonia.

He was banging the side rails, making sounds, and pointing to his endotracheal tube. He was diaphoretic, gasping and frantic. The nurse put her hand on his arm and tried to ascertain whether he had a sore throat from the tube. While she was away from the bedside retrieving an analgesic, the expert nurse strolled by, hesitated, listened, went to the man’s bedside, reinflated the endotracheal cuff, and accepted the patient’s look of gratitude because he was able to breathe again. The non-expert nurse was distressed that she had misread the situation. The expert reviewed the signs of a leaky cuff with the non-expert and pointed out that banging the side rails and panic help differentiate acute respiratory distress from pain.

Critical thinking enables you to (Tanner, 2006):

• Analyse complex data about patients

• Make decisions about patients’ problems and alternative possibilities

• Evaluate each problem to decide which applies

• Decide on the most appropriate interventions for the situation.

Picture critical thinking ability as having three overlapping dimensions (Fig 2.2). Your critical thinking ability grows as you develop (1) a critical thinking character (a commitment to learning critical thinking characteristics, attitudes and dispositions); (2) the theoretical and experiential knowledge (what to do, when to do it, why to do it); and (3) the intellectual and manual skills (assessing systematically and psychomotor skills) (Alfaro-LeFevre, 2009). The dimensions of critical thinking include an attitude of inquiry, knowledge of the subject, and skills in using this knowledge in problem situations.

Alfaro-LeFevre (2008) presents the following 17 critical thinking skills, organised in the logical progression of the ways the skills might be used. Although each skill here is described separately, they are not used that way in the clinical area. Rather than a step-by-step linear process, critical thinking is a multidimensional thinking process. With experience, you will be able to apply these skills in a rapid, dynamic and interactive way. For now, follow Ellen’s case study through the steps.

1. Identifying assumptions. That is, recognise that you could take information for granted or see it as fact when actually there is no evidence for it. Ask yourself, ‘What am I taking for granted here?’ For example, in Ellen’s situation, you might have assumptions of a ‘typical profile’ of a person with alcohol abuse, based on your past experience or exposure to media coverage. However, the facts of Ellen’s situation are unique.

2. Identifying an organised and comprehensive approach to assessment. This depends on the patient’s priority needs and your personal or institutional preference. Ellen has many problems, but at her time of admission, she is not acutely physically ill. Thus you may use any organised format for assessment that is feasible for you: a head-to-toe approach, a body systems approach (e.g. cardiovascular, gastrointestinal), a focused area (e.g. respiratory asssessment), functional assessment or assessment of activities of daily living or the use of a preprinted assessment form developed by the clinical agency.

3. Validation, or checking the accuracy and reliability of data. For example, in addictions treatment, a clinician will corroborate data with a family member in order to verify the accuracy of Ellen’s history. In Ellen’s particular case, her significant others are absent or non-supportive, and the corroborative interview may need to be with a social worker.

4. Distinguishing normal from abnormal when identifying signs and symptoms. This is the first step to problem identification, and your ease will grow with study, practice and experience. Increased BP and wheezing are among the many abnormal findings in Ellen’s case.

5. Making inferences, or drawing valid conclusions. This involves interpreting the data and deriving a correct conclusion about the health status. This presents a challenge for the beginning examiner, because it needs a baseline amount of knowledge and experience. Is Ellen’s increased BP due to the stress of admission or a chronic condition?

6. Clustering related cues, which will help you see relationships among the data. For example, heavy alcohol use, social consequences of alcohol use, academic consequences and occupational consequences are a clustering of cues that suggest a maladaptive pattern of alcohol use.

7. Distinguishing relevant from irrelevant. A complete history and physical assessment provides a vast amount of data. Look at the clusters of data, and consider which data are important for a health problem or a health promotion need. This skill is also a challenge for beginning nurses, and one area where a clinical preceptor or educator can be invaluable.

8. Recognising inconsistencies. When Ellen gives the explanation that she ran into a door (subjective data), it is at odds with the location of the infraorbital haematoma (objective data). With this kind of conflicting information, you can investigate and further clarify the situation.

9. Identifying patterns. This helps to fill in the whole picture and discover missing pieces of information. You need to know usual function of the cardiovascular system, to decide if the elevated blood pressure is a problem for Ellen.

10. Identifying missing information, gaps in data or a need for more data to make a diagnosis. Ellen will need more interviewing regarding any increasing tolerance to alcohol, any withdrawal signs or symptoms and laboratory data regarding liver enzymes and blood count, in order to name a diagnosis.

11. Promoting health by identifying risk factors. This applies to generally healthy people and concerns disease prevention and health promotion. To achieve this skill, you need to identify and manage known risk factors for the individual’s age group and cultural status. This will drive your wellness diagnosis. For example, counselling for injury prevention is an important intervention for Ellen because motor vehicle and other unintentional injuries are a leading cause of death for this age group.

12. Diagnosing actual and potential (risk) problems from the assessment data. A full list of diagnoses (both medical and nursing) derived from Ellen K.’s health history and physical examination is found in Chapter 29.

13. Setting priorities when there is more than one nursing diagnosis. In the hospitalised, acute care setting, the initial problems are usually related to the reason for admission. However, the acuity of illness often determines the order of priorities of the person’s problems (Table 2.1).

TABLE 2.1 A common approach to identifying immediate priorities

From Alfaro-LeFevre R: Critical thinking and clinical judgment: a practical approach to outcome-focused thinking, 4th edn. Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders.

For example, first-level priority problems are those that are emergent, life threatening and immediate, such as establishing an airway or supporting breathing.

Second-level priority problems are those that are next in urgency—those requiring your prompt intervention to forestall further deterioration; for example, mental status change, acute pain, acute urinary elimination problems, untreated medical problems, abnormal laboratory values, risks of infection or risk to safety or security. Ellen has abnormal physical signs that fit in the category of untreated medical problems. For example, Ellen’s adventitious breath sounds are a cue to further assess respiratory status to determine the final diagnosis. Ellen’s mildly elevated blood pressure needs monitoring also.

Third-level priority problems are those that are important to the patient’s health but can be addressed after more urgent health problems are addressed. In Ellen’s case, the data indicating diagnoses of knowledge deficit, altered family processes and low self-esteem fit in this category. Interventions to treat these problems are more long term, and the response to treatment is expected to take more time.

Collaborative problems are those in which the approach to treatment involves multiple disciplines. Collaborative problems are certain physiological complications in which nurses have the primary responsibility to diagnose the onset and monitor the changes in status (Carpenito-Moyet, 2008). For example, the data regarding alcohol abuse represent a collaborative problem. With this problem, the sudden withdrawal of alcohol has profound implications on the central nervous and cardiovascular systems. During detoxification, Ellen’s response to the rebound effects of these systems is managed.

14. Determining patient-centred expected outcomes. What specific, measurable results will you expect that will show an improvement in the person’s problem after treatment? The outcome statement should include a specific time frame. After 5 days, Ellen will demonstrate how to manage balanced nutrition by keeping a food diary and by stating which food groups are present/absent in her diary.

15. Determining specific interventions that will achieve your outcomes. These interventions aim to prevent, manage or resolve health problems. This is the healthcare plan. For specific interventions, state who should perform the intervention, when and how often, and the method used.

16. Evaluating and correcting thinking. Look at the expected outcomes, and apply them for evaluation. Do the stated outcomes match the individual’s actual progress? Then, analyse whether your interventions were successful or not. Continually think, ‘What could I be doing differently or better?’

17. Determining a comprehensive plan/evaluating and updating the plan. Record the revised plan of care and keep it up to date. Communicate the plan to the multidisciplinary team. Be aware that this is a legal document, and accurate recording is important for evaluation, insurance reimbursement and research.

DIAGNOSTIC REASONING IN CLINICAL DECISION MAKING

Diagnostic reasoning, the process of analysing health data and drawing conclusions to identify health issues or problems, is based on the scientific method used by most health professions. It has four major components: (1) attending to initially available cues; (2) formulating diagnostic hypotheses; (3) gathering additional data relative to the tentative hypotheses; and (4) evaluating each hypothesis with the new data collected, thus arriving at a final judgment about the health issue/s. A cue is a piece of information, a sign or symptom or a piece of laboratory data. A hypothesis is a tentative explanation for a cue or a set of cues that can be used as a basis for further investigation.

For example, consider Ellen K., the case study presented at the beginning of this chapter. Ellen presents with a number of initial cues, one of which is the resolving haematoma under her eye. (1) You can recognise this cue even before history taking begins. Is it significant? (2) Ellen says she ran into a door, although she mumbles as she speaks and avoids eye contact. At this point, you formulate a hypothesis of trauma. (3) During the history and physical examination, you gather data to support or reject the tentative hypothesis. (4) You synthesise the new data collected, which support the hypothesis of trauma but eliminate the accidental cause because you discover that Ellen’s boyfriend hit her during an argument. The final diagnoses are resolving right orbital contusion and risk for trauma.

Diagnostic hypotheses are activated very early in the reasoning process. Consider this a ‘hunch’ that Ellen has suffered physical trauma. A hunch helps diagnosticians adapt to large amounts of information because it clusters cues into meaningful groups and directs subsequent data collection. Later, you can accept your hunch or rule it out.

Once you complete data collection, develop a preliminary list of significant signs and symptoms and all patient health needs. This is less formal in structure than your final list of diagnoses will be and is in no particular order. In some institutions, it is easier to generate such a list if you use a conceptual model. Examples of conceptual models are described later in this chapter.

Cluster or group together the assessment data that appear to be causal or associated. For example, with a person in acute pain, associated data are rapid heart rate and anxiety. Organising the data into meaningful clusters is slow at first; experienced nurses cluster data more rapidly because they recall proven results of earlier patient situations (Benner et al, 1996). Use of a conceptual model helps to organise data.

Validate the data you collect to make sure they are accurate. As you validate your information, look for gaps in data collection. Be sure to find the missing pieces, as identifying missing information is an essential critical thinking skill. How you validate your data depends on experience. If you are unsure of the blood pressure, validate it by repeating it yourself. Eliminate any extraneous variables that could influence results, such as recent activity or anxiety over admission. If you have less experience analysing breath sounds ask an expert to listen. Even with years of clinical experience, some signs always require validation (e.g. a breast lump). Figure 2.3 represents one approach to clinical decision making.

The step from data collection to diagnosis can be a difficult one. Most beginning nurses perform well in gathering the data, given adequate practice, but then tend to treat all the data as being equally important. Bucknall (2000) reports that novice nurses take more time to collect assessment information hence delaying problem management. This makes decision making slow and laboured.

USING A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK TO GUIDE NURSING PRACTICE

The organisation of assessment data—the database—varies depending on the conceptual model that is used by the institution. A model provides the framework in determining what to observe, how to organise the observations or data and how to interpret and use the information. Many different conceptual models exist, but they all deal with the same concepts: human beings, environment and society, health and illness and nursing.

Although all nursing models describe the same four concepts, each one has a different focus or emphasis. For example, the focus of Orem’s model (2001) is self-care. The focus of assessment using Orem’s model is on finding out whether the person can manage their activities of daily living and how much assistance is required. The focus of Gordon’s structural framework (1994) involves functional health patterns. The focus of assessment is on the person’s perception of health and health management, sleep and rest, self concept, roles and relationships, sexuality and reproduction, stress and stress responses and values and beliefs, in addition to physical health status, for example respiration, circulation, cognition and perception, elimination, nutrition and mobility. Although each model is different, these nursing models should lead to similar nursing diagnoses.

A nursing model is used along with, not in place of, a medical model. Nurses use the medical model when they work interdependently with the medical practitioner in the diagnosis and treatment of disease. The medical model is focused on physical assessment. A concurrent nursing model is therefore needed to focus assessment on core nursing concerns, such as nutrition, activity, hygiene, skin problems, coping problems or self-care limitations.

A model, or a blend of models, is useful as a framework for the assessment tool. Become familiar with the conceptual model(s) in use at your institution. Use this framework to cluster the assessment data and to prioritise the diagnoses. The use of nursing diagnoses and the companion classification systems for interventions and outcomes give nurses a common language with which to communicate nursing findings.

Patient problems or patient responses or nursing diagnoses result from the data collected through questioning (subjective) and physical assessment of the person (objective) and the information gathered from additional sources (history, family, laboratory tests) in relation to a person’s response to an actual or potential health alteration. Note that the list includes (1) actual diagnoses, existing problems that are amenable to independent nursing interventions; (2) risk diagnoses, potential problems that an individual does not currently have but is particularly vulnerable to developing; and (3) wellness diagnoses, which focus on strengths and reflect an individual’s transition to a higher level of wellness. While nursing diagnoses as per the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA) are not commonly used in clinical practice in Australia, they provide a language and structure for naming problems for nursing students and therefore may be encountered in theoretical programs and nursing text books. Throughout this book, appropriate diagnoses from this list are presented and developed as they pertain to related content in each chapter. In Chapter 29 the list of findings for Ellen K. are analysed and rewritten as diagnoses.

Regarding Ellen’s case study, the medical diagnosis describes the aetiology (cause) of disease. The nursing diagnosis describes the response or the symptoms experienced by the person/family or community to actual or potential health problems. For example, both the admitting nurse and later the physician auscultate Ellen’s lung sounds and determine that they are diminished and that wheezing is present. This is data that is relevant to a medical and a nursing diagnosis. The physician listens to diagnose the cause of the abnormal sounds (in this case, asthma) and to order specific drug treatment. The nurse listens to detect abnormal sounds, to monitor Ellen’s response to treatment and to initiate supportive measures and teaching. For example, the nurse may teach Ellen which behavioural measures may help her to quit smoking and may recommend that Ellen initiate a walking program. In addition, the nurse will administer the ordered medications, arrange the ordered laboratory tests and design a plan of care to ensure that all of Ellen’s needs are identified and met.

The medical and nursing diagnoses should not be seen as isolated from each other. It makes sense that the medical diagnosis of asthma be reflected in the nursing diagnoses, as interpreted by the nurse’s knowledge of the person’s response to asthma. In this book, common nursing diagnoses are presented along with medical diagnoses to illustrate common abnormalities. Observe how these two types of diagnoses are interrelated.

COLLECTING FOUR TYPES OF DATA

Every nurse needs to collect four different kinds of database depending on the clinical situation: complete (total), focused (episodic or problem-centred), follow-up, and emergency.

1 Complete (total) patient assessment

This includes a complete health history and a full physical examination. It describes the current and past health state and forms a baseline against which all future changes can be measured. It yields the first diagnoses.

In primary care, the complete database is collected from a person in a primary care setting, such as a community health clinic, independent private practice, university health clinic or women’s healthcare clinic. When you work in these settings, you are usually the first health professional to see the patient and have primary responsibility for monitoring the person’s healthcare. For the well person, this database must describe the person’s health state, perception of health, strengths or assets such as health maintenance behaviours, individual coping patterns, support systems, current developmental tasks, roles and relationships and any risk factors or lifestyle changes. For the ill person, the database also includes a description of the person’s health problems, perception of illness and response to the problems.

For well and ill people, the complete database includes screening for pathology as well as determining the response to that pathology or to any health problem. This factor is important because it provides additional information about the person that leads to nursing diagnoses. You will screen for pathology in order to refer the patient to another professional, to help the patient make decisions and to perform appropriate treatments.

In acute hospital care, the complete database is also gathered following admission to the hospital. In the hospital, data related specifically to pathology may be collected by the admitting physician. You will collect additional information on the patient’s perception of illness, functional ability or patterns of living, activities of daily living, health maintenance behaviours, response to health problems, coping patterns, interaction patterns and health goals. This approach completes the database from which the nursing diagnoses can be made.

2 Focused (episodic or problem-centred) assessment

This is for a limited or short-term problem. Here, you complete a focused assessment, which is smaller in scope than the total patient assessment. It concerns mainly one problem, one cue complex or one body system. It is used in all settings—hospital, primary care or long-term care. For example, 2 days following surgery, a hospitalised person suddenly has a congested cough, shortness of breath and fatigue. The history and examination focus primarily on the respiratory and cardiovascular systems. Or, in an outpatient clinic, a person presents with a rash. The history and examination follow the direction of this presenting concern, such as whether the rash had an acute or chronic onset, was associated with a fever and was localised or generalised. History and examination includes a clear description of the rash.

3 Follow-up assessment

The status of any identified problems should be evaluated at regular and appropriate intervals. What change has occurred? Is the problem getting better or worse? What coping strategies are used? This type of assessment is used in all settings to follow up short-term or chronic health problems.

4 Emergency assessment

This calls for a rapid collection of data, often compiled concurrently with lifesaving measures. Diagnosis must be swift and sure. For example, in a hospital emergency department, a person is brought in with suspected substance overdose. The first history questions are ‘What did you take?’, ‘How much did you take?’ and ‘When?’ The person is questioned simultaneously while their airway, breathing, circulation, level of consciousness and disability are being assessed. Clearly, the emergency assessment requires more rapid collection of data than the focused episodic assessment.

FREQUENCY OF ASSESSMENT

The interval of assessment varies with the person’s illness and wellness needs. Most ill people seek care because of pain or some abnormal signs and symptoms they have noticed. This prompts an assessment—gathering a total, a focused or an emergency assessment.

There is now a focus on health and health promotion so that healthy living, working and recreational environments are emphasised. This is in line with the World Health Organization’s definition of health promotion: ‘the process of enabling people to increase control over the determinants of health and thereby improve their health’. Opinions are changing about the health checkup intervals. The term ‘annual checkup’ is vague. What does it constitute? Is it necessary or cost effective? Does it sometimes give an implicit promise of health and thus provide false security? What about the classic situation of a person suffering a heart attack 2 weeks after a routine checkup and normal findings on electrocardiogram? The timing of some formerly accepted procedures is now variable—for example, the annual Papanicolaou test for cervical cancer in women. The same annual routine physical examination cannot be recommended for all persons because health priorities vary among individuals, different age groups and risk categories, and because some preventive services are effective only in certain populations. The routine periodic examination for Ellen K.’s age group (11 to 24 years old) would be recommended to include the following services for preventive healthcare:

1. Screening history for dietary intake, physical activity, tobacco/alcohol/drug use and sexual practices

2. Physical examination for height and weight, blood pressure and Papanicolaou test for sexually active females

3. Counselling for injury prevention (lap/shoulder belts, bicycle/motorcycle/ATV (all terrain vehicle) helmets, smoke detector, safe storage/removal of firearms), substance use (avoid tobacco, avoid underage drinking and illicit drug use, avoid alcohol/drug use while driving, swimming, boating), sexual behaviour (STD (sexually transmitted disease) prevention, abstinence, avoidance of high-risk behaviour, use of condoms or female barrier with spermicide, unintended pregnancy, contraception), diet and exercise (limit fat and cholesterol; maintain caloric balance; emphasise grains, fruits and vegetables; adequate calcium intake for females; regular physical activity) and dental health (regular visits to provider, floss, brush with fluoride toothpaste)

4. Immunisations for tetanus–diphtheria (11 to 16 years); hepatitis B, MMR (measles–mumps–rubella), varicella and HPV vaccine (11 to 12 years); and rubella (females over 12 years)

5. Chemoprophylaxis to include multivitamin with folic acid (females capable of or planning pregnancy).

Additionally, the leading causes of death in Ellen K.’s age group are listed as accidental injuries in Australia and New Zealand, and in Australia, poisoning (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2006; New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2010). Obviously, Ellen’s individual health problems demand immediate intervention and preclude a strict adherence to this preventive list. Indeed, many of Ellen’s findings are seen as ‘red flags’ based on predictable risk factors from this list.

HIGH-LEVEL ASSESSMENT SKILLS

This attention to life cycle, symptom, risk and alteration in function does not detract from the importance of assessment skills themselves. Assessment skills must be practised with hands-on experience and refined to a high level. In many community settings, the nurse is the first and often the only health professional to see an individual. In the hospital, the nurse is the only health professional continually present at the bedside.

Current efforts in cost containment result in a hospital population composed of people who have increased acuity, a shorter stay and an earlier discharge than in the past. This situation requires faster, more efficient assessments from the nurse. Procedures that used to require a standard hospital stay of several days (e.g. surgery for inguinal hernia, or removal of cataracts) are now done in day procedure centres. As a result, nurses go to people’s homes for follow-up assessment and diagnosis. These situations require first-rate assessment skills that are grounded in a holistic approach and a knowledge of age-specific problems.

Alfaro-Lefevre R. Applying nursing process—a tool for critical thinking, 7th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

Alfaro-Lefevre R. Critical thinking and clinical judgment: a practical approach to outcome-focused thinking, 4th edn. St Louis: Saunders/Elsevier, 2008.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Mortality over the twentieth century in Australia. Trends and patterns in major causes of death. Available at http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/phe/motca/motca.pdf, 2006.

Australian Nursing & Midwifery Accreditation Council. National competency standards for registered nurses. Available at http://www.anmc.org.au/, 2010.

Banning M. 2008 The think aloud approach as an educational tool to develop and assess clinical reasoning in undergraduate students. Nurse Educ Today. 2008;28(1):8–14.

Banning M. Clinical reasoning and its application to nursing practice: concepts and research studies. Nurse Educ Pract. 2008;8(3):177–183.

Benner P, Tanner CA, Chesla CA. Becoming an expert nurse. Am J Nurs. June 1997;97(6):16. 16

Benner P, Tanner CA, Chesla CA. Expertise in nursing practice. New York: Springer, 1996.

Benner P. From novice to expert—excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Menlo Park, California: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1984.

Bucknall T. Critical care nurses’ decision-making activities in the natural settings. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2000;9(1):25–36.

Carpenito-Moyet L. Handbook of nursing diagnosis. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

Clinical Excellence Commission. Resources, tools and toolkits. Available at http://www.cec.health.nsw.gov.au/resources.html, 2009.

Fesier-Birch D. Critical thinking and patient outcomes: a review. Nursing Outlook. 2005;53(2):59–65.

Gobet F, Chassy P. Towards an alternative to Benner’s theory of expert intuition in nursing: a discussion paper. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2008;45(1):129–139.

Gordon M. Nursing diagnosis: process and application, 3rd edn. St Louis: Mosby, 1994.

Hanneman SK. Advancing nursing practice with a unit-based clinical expert. Image. 1996;28(4):331–337.

Hoffman K, Aitken L, Duffield C. A comparison of novice and expert nurses’ cue collection during clinical decision-making: verbal protocol analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2009;46:1335–1344.

Joanna Briggs Institute. Evidence based nursing. Available at http://www.joannabriggs.edu.au/about/eb_nursing.phpI, 2009.

National Public Health Partnership, 2005: The national injury prevention and safety promotion plan: 2004–2014. Available at http://www.nphp.gov.au/publications/sipp/nipspp.pdf.

New Zealand Ministry of Health. Mortality and demographic data 2007. Available at http://www.moh.govt.nz, 2010.

Nursing Council of New Zealand. Framework for professional standards. Available at http://www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/download/48/framework-standards-march-2007.pdf, 2007.

Oermann MH. Critical thinking, critical practice. Nurs Manage. 1999;30(4):40. 40

Orem DE, Taylor SG, Renpenning KM. Nursing: concepts of practice, 6th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2001.

Simmons B. Clinical reasoning: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(5):1151–1158.

Tanner C. Thinking like a nurse: a research-based model of clinical judgment in nursing. Journal of Nursing Education. 2006;45(6):204–211.

Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Health Care, 2010. http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/.