Chapter Twenty Bowel function

INTRODUCTION

Bowel assessment is a frequent focus for nurses. Because so many body systems are involved as you progress through this chapter you also need to take into account the structure and function related to eating (mouth, teeth and throat, and nutrition—Chs 13 and 16) and the small and large bowel (Ch 19) as well as the anus and rectum described in this chapter.

ANUS AND RECTUM

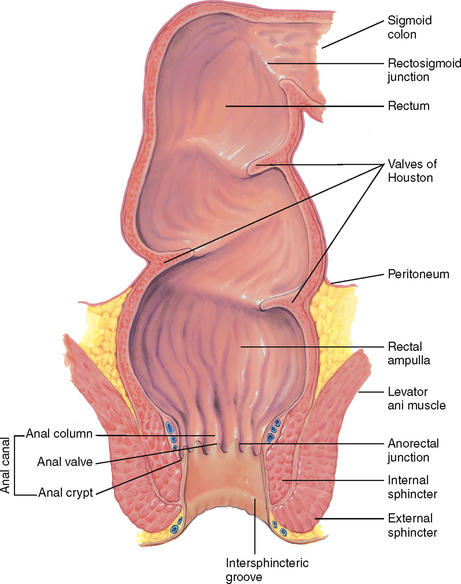

The anal canal is the outlet of the gastrointestinal tract, and is about 3.8 cm long in the adult. It is lined with modified skin (having no hair or sebaceous glands) that merges with rectal mucosa at the anorectal junction. The canal slants forwards towards the umbilicus, forming a distinct right angle with the rectum, which rests back in the hollow of the sacrum. Although the rectum contains only autonomic nerves, numerous somatic sensory nerves are present in the anal canal and external skin, so a person feels sharp pain from any trauma to the anal area.

The anal canal is surrounded by two concentric layers of muscle, the sphincters (Fig 20.1). The internal sphincter is under involuntary control by the autonomic nervous system. The external sphincter surrounds the internal sphincter but also has a small section overriding the tip of the internal sphincter at the opening. It is under voluntary control. Except for the passing of faeces and gas, the sphincters keep the anal canal tightly closed. The intersphincteric groove separates the internal and external sphincters and is palpable.

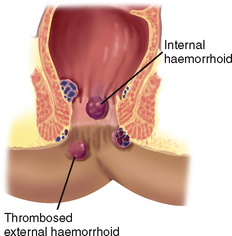

The anal columns (or columns of Morgagni) are folds of mucosa. These extend vertically down from the rectum and end in the anorectal junction (also called the mucocutaneous junction, pectinate or dentate line). This junction is not palpable, but it is visible on proctoscopy. Each anal column contains an artery and a vein. Under conditions of chronic increased venous pressure, the vein may enlarge, forming a haemorrhoid. At the lower end of each column is a small crescent fold of mucous membrane, the anal valve. The space above the anal valve (between the columns) is a small recess, the anal crypt.

The rectum, which is 12 cm long, is the distal portion of the large intestine. It extends from the sigmoid colon, at the level of the third sacral vertebra, and ends at the anal canal. Just above the anal canal, the rectum dilates and turns posteriorly, forming the rectal ampulla. The rectal interior has three semilunar transverse folds called the valves of Houston. These cross half the circumference of the rectal lumen. Their function is unclear, but they may serve to hold faeces as the flatus passes. The lowest is within reach of palpation, usually on the person’s left side, and must not be mistaken for an intrarectal mass.

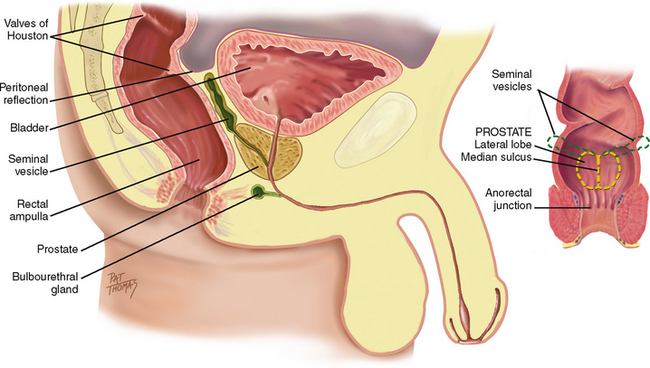

Peritoneal reflection.

The peritoneum covers only the upper two-thirds of the rectum. In the male, the anterior part of the peritoneum reflects down to within 7.5 cm of the anal opening, forming the rectovesical pouch (Fig 20.2) then covers the bladder. In the female, this is termed the recto-uterine pouch, and extends down to within 5.5 cm of the anal opening.

REGIONAL STRUCTURES

In the female, the uterine cervix lies in front of the anterior rectal wall and may be palpated through it.

The combined length of the anal canal and the rectum is about 16 cm in the adult. The average length of the examining finger is from 6 cm to 10 cm, bringing many rectal structures within reach.

The sigmoid colon is named from its S-shaped course in the pelvic cavity. It extends from the iliac flexure of the descending colon and ends at the rectum. It is 40 cm long and is accessible to examination only through the colonoscope. The flexible fibreoptic scope in current use provides a view of the entire mucosal surface of the sigmoid, as well as the colon.

DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Infants

The first stool passed by the newborn is dark green meconium and occurs within 24 to 48 hours of birth, indicating anal patency. From that time on, the infant usually has a stool after each feeding. This response to eating is a wave of peristalsis called the gastrocolic reflex. It continues throughout life, although children and adults usually produce no more than one or two stools per day.

The infant passes stools by reflex. Voluntary control of the external anal sphincter cannot occur until the nerves supplying the area have become fully myelinated, usually around 1½ to 2 years of age. Toilet training usually starts after age 2 years.

Late adulthood (65+ years)

There is a widely accepted belief that people are more likely to develop health problems related to bowel function as they age. However, gut transit time and colonic motility are consistent throughout life (Marieb and Hoehn, 2010), and most older people maintain the same frequency of bowel movements that they had in their younger years. Bowel function is more likely to be influenced by other factors such as chronic disease, immobility and the various treatments for these health problems (Harari, 2004). There is an increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer with ageing, rising sharply after the age of 50 years. The lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer for Australians to age 75 is 1 in 19 men and 1 in 25 women, and lifetime risk to age 85 is 1 in 10 men and 1 in 15 women (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2008). There is a similar incidence in New Zealand (New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2010). For more information about colorectal cancer and screening programs see ‘Promoting a healthy lifestyle’ below.

SUBJECTIVE DATA

Assessment of bowel function is a frequent assessment area for nurses in a variety of healthcare settings. The extent of the questioning and examination will depend on the person’s main health concern. Some people will focus on their bowel function and have strong beliefs about what they consider normal. It is also an area of health that people will frequently self-manage. You need to screen hospitalised patients for risk for development of constipation and put interventions in place to prevent constipation developing. Many people with bowel problems, in particular faecal incontinence, will be reluctant to discuss their problem so you need to approach these questions with tact and empathy.

3. History of change or disturbance in bowel function

| Assessment guidelines | Clinical significance and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| Consider food poisoning. | |

| Consider parasitic infection. | |

| Consider constipation. | |

4. Bowel symptoms. Rectal bleeding, blood in the stool: have you ever had black or bloody stools? When did you first notice blood in the stools? What is the colour, bright red or dark red-black? How much blood: spotting on the toilet paper or outright passing of blood with the stool? Do the bloody stools have a particular smell? |

Black stools may be tarry due to occult blood (melaena) from gastrointestinal bleeding, or nontarry from ingestion of iron medications. Red blood in stools occurs with gastrointestinal bleeding or localised bleeding around the anus, and also with colon and rectal cancer. The person should be referred to a medical practitioner for further assessment. |

| • Have you ever had clay-coloured stools? | Clay colour indicates absent bile pigment. |

| • Frothy stool? | Steatorrhoea is excessive fat in the stool as in malabsorption of fat. |

| • Flatus: Can you control wind? Passage of flatus is a normal finding. Do you feel that you have excessive wind? Are you able to distinguish between flatus and stool? | |

| Consider faecal incontinence. If the person is unable to defer defecation even when the stool consistency is normal they are likely to have poor external anal sphincter function. In this situation the person should be referred to a continence nurse advisor or medical practitioner for further assessment. | |

| • Passive soiling: Do you ever experience any leakage from the bowel? Were you aware of this happening? Was it liquid or solid stool? How often does this happen? Does it happen only after you have used your bowels? | Any weakness of the anal sphincter can result in the sphincter not keeping the anal canal closed. Passive soiling is associated with weakness or damage to the anal sphincter. |

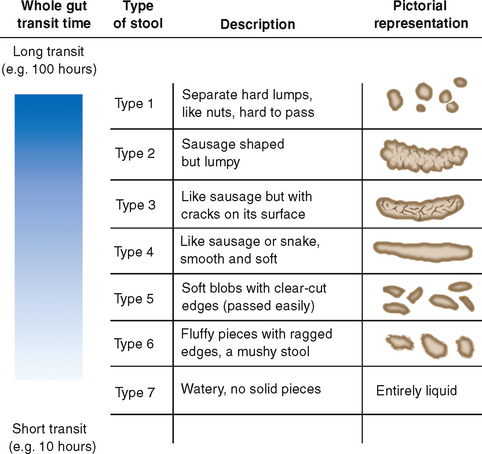

| Ask the person to describe their bowel movement using the Bristol stool chart (Fig 20.3). The Bristol stool chart is a validated tool for describing stool appearance. It is a 7-point scale. Types 3 and 4 are considered to be the most usual or ‘normal’ consistency. | |

| Pruritus. | |

| Many prescription medications can cause bowel problems. It is important to note what laxatives a person takes on a regular basis. If these are stopped abruptly for any reason this could result in sudden and severe constipation especially if the laxatives have been taken over many years. | |

7 Past history. Any family history: polyps or cancer in colon or rectum, inflammatory bowel disease, prostate cancer? Any surgery or medical condition which may have contributed to disturbed bowel function? (e.g. gynaecological surgery, abdominal surgery, neurological disease) For women—obstetric history: How many births? Were forceps used for any of these? Did you have an episiotomy? What were the babies’ birth weights? Did you have any bowel control issues after the births? |

Risk factors for colorectal cancer. Labour and delivery, especially prolonged labour and instrumental delivery, can damage the anal sphincter which can predispose the woman to faecal incontinence (Hunskar et al, 2005). |

| High-fibre foods of the soluble type (beans, prunes, barley, carrots, broccoli, cabbage) have been shown to lower cholesterol, while insoluble fibre foods (cereals, wheatgerm) reduce the risk of constipation and colon cancer. Also, fibre foods fight obesity, stabilise blood sugar and help certain gastrointestinal disorders. | |

| Inadequate fluid intake is significantly related to the development of constipation. | |

| If you find significant risk factors in this area you may need to complete a more detailed nutritional assessment–see Chapter 16. | |

| • Activity and exercise: What regular exercise do you undertake? Describe your usual day in terms of exercise and activity. If the person has a very sedentary lifestyle, what is stopping them being more active? | Lack of activity and exercise are significantly related to the development of constipation. Lack of activity may be related to another health problem; for example, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease which can cause significant breathlessness on exertion. |

| • Smoking: How much? How long? | Smoking can affect bowel function and is a risk factor for colorectal cancer. |

| • Screening: Date of last: digital rectal examination, stool occult blood test, colonoscopy. | Early detection for cancer. See ‘Promoting a healthy lifestyle’ below. |

| • Pads or pants: When people disclose bowel control issues ask them if they ever need to wear a pad to protect their clothes from leakage from their bowel. This may give you an indication of the severity of the problem. | |

9 Environmental issues related to bowel function. You need to make a judgment about whether the following questions are relevant to the individual’s situation: Do you need assistance to get to the toilet? Get the person to describe the level of assistance required. Do you need assistance with toileting (e.g. undressing, getting onto the toilet)? Get the person to describe the level of assistance required. Do you fnd it diffcult to get to the toilet (e.g. stairs, distance from living area or bedroom)? Get the person to describe the difficulty. Do you use toileting aids (e.g. commode chairs, raised toilet seats, support rails)? |

Some people will have difficulties get ting to the toilet or with activities associated with toileting that may cause them to be incontinent. These need to be investigated so that appropriate interventions can be put in place to improve the situation. |

10. Bowel diary. If the person is experiencing bowel dysfunction it is often necessary to ask them to complete a bowel diary. A bowel diary is used to collect information about the frequency, amount and consistency of bowel movements over a period of time, preferably at least one week. The person is asked to complete a simple chart which details the date and time, description (using the Bristol Stool Form Chart, Fig 20.3) and notes about bowel-related symptoms. The data from the chart provides useful information about the severity of symptoms (including incontinence episodes) and the person’s actual bowel elimination patterns. |

|

| Additional history for infants and children | |

| In children, pinworms are a common cause of intense itching and irritated anal skin. | |

| Assess usual elimination pattern. Constipation is a decrease in BM frequency, with difficult passing of very hard, dry stools. encopresis is persistent passing of stools into clothing in a child older than age 4 years, at which age continence would be expected. |

OBJECTIVE DATA

People who have bowel problems frequently have skin excoriation and/or anal abnormalities. The focus in objective assessment is on inspection of the skin and perianal area and inspection of stool.

Figure 20.3 Bristol stool form chart.

From Lewis SJ, Heaton KW: Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time, Scand J Gastroenterol 32(9):920–924, 1997.

You need to fully explain to the person the purpose of the examination and gain their consent. Make sure that the room is warm and that privacy is maintained.

| Preparation | Equipment needed |

|---|---|

Help the person assume one of the following positions (Fig 20.4): Examine the male in the left lateral position or standing position. Instruct the standing male to point his toes together; this relaxes the regional muscles, making it easier to spread the buttocks. |

|

| Procedures and normal fndings | Clinical signifcance and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

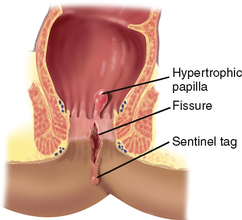

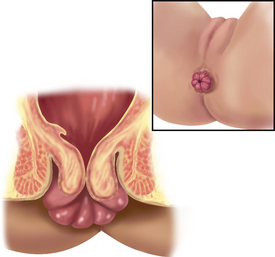

| Inflammation. Lesions or scars. Linear split–fissure. Flabby skin sac–haemorrhoid. Shiny blue skin sac—thrombosed haemorrhoid. | |

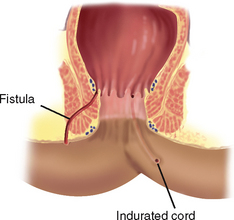

Small round opening in anal area– fistula (see Table 20.1). Perineal soiling may indicate loss of anal sphincter tone and/or poor hygiene practices. |

|

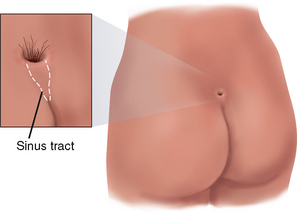

| Inspect the sacrococcygeal area. Normally, it appears smooth and even. | Infammation or tenderness, swelling, tuft of hair or dimple at tip of coccyx may indicate pilonidal cyst (see Table 20.1). |

| Instruct the person to breathe in, hold the breath and bear down by performing a Valsalva manoeuvre. No break in skin integrity or protrusion through the anal opening should be present. Describe any abnormality in clock-face terms, with 12:00 as the anterior point towards the symphysis pubis and 6:00 towards the coccyx. | |

| INSPECTION OF STOOL | |

Jelly-like mucus shreds mixed in stool indicate inflammation. Bright red blood on stool surface indicates rectal bleeding. Bright red blood mixed with faeces indicates possible colonic bleeding. Black tarry stool with distinct malodour indicates upper gastrointestinal bleeding with blood partially digested. (Must lose more than 50 mL from upper gastrointestinal tract to be considered melaena.) Black stool–also occurs with ingesting iron or bismuth preparations. Grey, tan stool–absent bile pigment, e.g. obstructive jaundice. Pale yellow, greasy stool–increased fat content (steatorrhoea), as occurs with malabsorption syndrome. |

|

| DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS | |

| Infants and children | |

| For the newborn, hold the feet with one hand and fex the knees up onto the abdomen. Note the presence of the anus. Confirm a patent rectum and anus by noting the first meconium stool passed within 24 to 48 hours of birth. To assess sphincter tone, check the anal refex. Gently stroke the anal area and note a quick contraction of the sphincter. | Imperforate anus. |

| For each infant and child, note that the buttocks are firm and rounded with no masses or lesions. Recall that the mongolian spot is a common variation of hyperpigmentation in newborns (see Ch 17). | Flattened buttocks in cystic fibrosis or coeliac syndrome. Coccygeal mass. |

| Meningocele (sac containing meninges that protrude through a defect in the bony spine). | |

| Tuft of hair or pilonidal dimple. | |

| The perianal skin is free of lesions. However, nappy rash is common in children younger than 1 year of age and is exhibited as a generalised reddened area with papules or vesicles. | |

| Fissure–common cause of constipation or rectal bleeding in child. (Painful, so the child does not defecate.) | |

| Inspect the perianal region of the school-age child and adolescent during examination of the genitalia. |

FURTHER OBJECTIVE ASSESSMENT FOR ADVANCED PRACTICE

Nurses working in the acute care setting rarely perform a screening rectal examination; however, they may need to perform a rectal examination as part of a comprehensive assessment of a person with severe constipation, prior to deciding on the most appropriate treatment. You need to make a clinical judgment about the need to perform a rectal examination. Continence nurse advisors may perform this assessment as part of a comprehensive assessment of constipation and faecal incontinence.

TABLE 20.1 Abnormalities of the anus and perianal region

You need to fully explain the procedure to be performed and get the person’s consent. Make sure that the room is warm and privacy is maintained.

| Preparation | Equipment needed |

|---|---|

| Help the person assume one of the positions described in Figure 20.4 | Lubricating jelly |

| Glove |

PALPATE THE ANUS AND RECTUM

| Procedures and normal fndings | Clinical signifcance and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| Drop lubricating jelly onto your gloved index finger. Instruct the person that palpation is not painful but may feel like needing to move the bowels. Place the pad of your index finger gently against the anal verge (Fig 20.5). You will feel the sphincter tighten, then relax. As it relaxes, flex the tip of your finger and slowly insert it into the anal canal in a direction towards the umbilicus. Never approach the anus at right angles with your index finger extended. Such a jabbing motion does not promote sphincter relaxation and is painful. | |

| Rotate your examining finger to palpate the entire muscular ring. The canal should feel smooth and even. Note the intersphincteric groove circling the canal wall. To assess tone, ask the person to tighten the muscle. The sphincter should tighten evenly around your finger with no pain to the person. | |

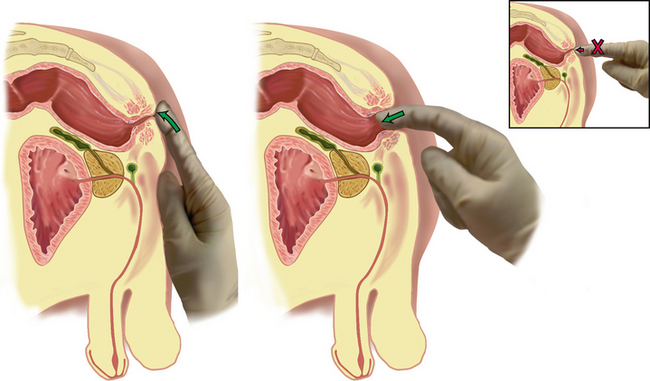

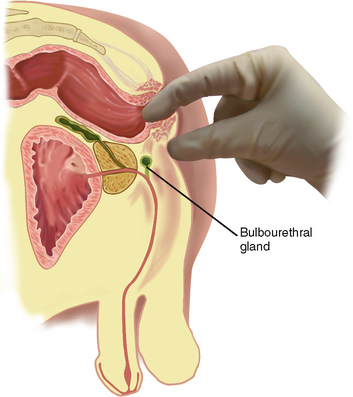

| Use a bidigital palpation with your thumb against the perianal tissue (Fig 20.6). Press your examining finger towards it. This manoeuvre highlights any swelling or tenderness and helps assess the bulbourethral glands. | |

| Above the anal canal, the rectum turns posteriorly, following the curve of the coccyx and sacrum. Insert your finger further and explore all around the rectal wall. It normally feels smooth with no nodularity. Promptly report any mass you discover for further examination. | |

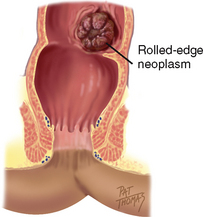

| A firm or hard mass with irregular shape or rolled edges may signify carcinoma (see Table 20.2). | |

| Palpate any stool in the rectum and assess consistency. Stool should be soft. | Presence of hard stool in the rectum in addition to a history that indicates constipation is significant and requires further assessment. You may also need to perform an abdominal palpation to determine the extent of the faecal loading before prescribing treatment for constipation. |

| Withdraw your examining finger; normally, no bright red blood or mucus is on the glove. To complete the examination, offer the person tissues to remove the lubricant and help the person to a more comfortable position. |

TABLE 20.2 Abnormalities of the rectum

|

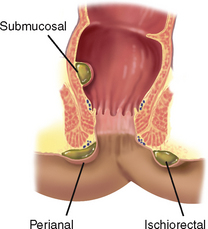

| Abscess |

| A localised cavity of pus from infection in a pararectal space. Infection usually extends from an anal crypt. Characterised by persistent throbbing rectal pain. Termed by the space it occupies, e.g. a perianal abscess is superficial around the anal skin, and appears red, hot, swollen, indurated and tender. An ischiorectal abscess is deep and tender to bidigital palpation. It occurs laterally between the anus and ischial tuberosity and is uncommon. |

|

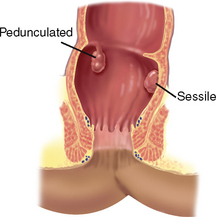

| Rectal polyp |

| A protruding growth from the rectal mucous membrane that is fairly common. The polyp may be pedunculated (on a stalk) or sessile (a mound on the surface, close to the mucosal wall). The soft nodule is diffcult to palpate. Proctoscopy is needed as well as biopsy to screen for a malignant growth. |

|

| Faecal impaction |

| A collection of hard, desiccated faeces in the rectum. The obstruction often results from decreased bowel motility, in which more water is reabsorbed from the stool. Also occurs with retained barium from gastrointestinal x-ray examination. The person may complain of constipation or of diarrhoea as a faecal stream passes around the impaction. |

|

| Carcinoma |

| A malignant neoplasm in the rectum is asymptomatic, thus the importance of routine rectal palpation. An early lesion may be a single firm nodule. You may palpate an ulcerated centre with rolled edges. As the lesion grows, it has an irregular cauliflower shape and is fixed and stone hard. Refer a person with any rectal lesion for further study because about half of such lesions are malignant. |

Promoting a healthy lifestyle Colorectal cancer screening

Screen for Life: National Bowel Screening Program

Colorectal (bowel) cancer is the second most common cancer in both men and women in Australia and the most common cancer in New Zealand (AIHW, 2008; New Zealand Cancer Registry, 2010). Risk factors include age, inherited genetic risk, inflammatory bowel disease, obesity and smoking (Cancer Council of Australia, 2010). Symptoms of colorectal cancer include a change in bowel habit with diarrhoea, constipation or the feeling of incomplete emptying; bowel movements that are narrower than usual, blood in the stool; or abdominal bloating or cramping. However, by the time symptoms are obvious the cancer may be quite advanced and more difficult to treat. Therefore a national bowel cancerscreening program was commenced in Australia and in New Zealand. The National Health and Medical Research Council (2005) recommends that all people 50 years and over should undergo faecal occult blood test (FOBT) every 2 years. Colorectal cancer screening with a FOBT has been shown to reduce the risk of dying from bowel cancer by up to one-third. People with a family history of bowel cancer or other risk factors need more intensive screening with regular colonoscopy and other diagnostic tests.

In Australia the Federal Government funds the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program. When people turn 50 years of age they receive an invitation through the mail to complete a FOBT in the privacy of their own home, free of charge. When they have collected the specimens, they return them by mail to a pathology laboratory for analysis. People with a positive FOBT result will be advised to discuss the result with their medical practitioner, who will generally refer them for further investigations, usually a colonoscopy. The New Zealand Ministry of Health has funded a similar pilot program for New Zealanders.

Take the opportunity to encourage people to collect and return their FOBT—it may just save their life! For further information go to the following websites:

National (Australian) Bowel Screening Program: http://www.cancerscreening.gov.au/internet/screening/publishing.nsf/Content/bowel-about

New Zealand Ministry of Health Bowel cancer program http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexmh/cancer control-strategyandactionplan-bowelcancerscreening

DOCUMENTATION AND CRITICAL THINKING

FOCUSED ASSESSMENT: CLINICAL CASE STUDY

Subjective

CM is a 30-year-old male who is complaining of ‘diarrhoea for 3 days’. No previous personal or family history of bowel problems.

7 days ago CM was seen at the clinic for an acute respiratory infection that was diagnosed as acute bronchitis and treated with oral ampicillin. He took medication as directed.

3 days ago: symptoms of respiratory infection improved. Following usual diet. Onset of four to five loose, unformed brown stools a day. No abdominal pain or cramping. No nausea.

Now: diarrhoea continues. No blood or mucus noticed in stool. No new foods or restaurant food in past 3 days. Wife not ill.

Abrams P, Cardozo P, Khoury S, et al. Incontinence: 4th international consultation on incontinence—Paris, 4th edn., Paris: Health Publications, 2009.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Cancer in Australia: an overview, 2008. Available at http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/index.cfm/title/10607/.

Bardsley A. Assessment and management of faecal incontinence. Journal of Community Nursing. 2009;23(4):4–10.

Barleben A, Mills S. Anorectal anatomy and physiology. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90(1):1–15.

Cancer Council of Australia. Colorectal cancer. Available at http://www.cancer.org.au/Healthprofessionals/cancertypes/colorectalcancer.htm.

Chelvanayagam S, Norton C. Nursing assessment of adults with faecal incontinence. In: Norton C, Chelvanayagam S. Bowel incontinence nursing. Beaconsfield, UK: Beaconsfield Publishers; 2004:45–62.

Doughty DB, Jensen LL. Assessment and management of the patient with faecal incontinence and related bowel dysfunction. In: Doughty DB, ed. Urinary and fecal incontinence: current management concepts. 3rd edn. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2006:457–490.

Eliopoulos C. Gerontological nursing, 7th edn. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Lippincott Williams Wilkins, 2010.

Gearhart SL, Ahuja N. Colorectal cancer. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2011.

Greenwald BJ. Clinical practice guidelines for pediatric constipation. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2010;22(7):332–338.

Harari D. Bowel care in old age. In: Norton C, Chelvanayagam S. Bowel incontinence nursing. Beaconsfield, UK: Beaconsfield Publishers, 2004.

Hunskar S, Burgio K, Clark A, et al. Epidemiology of urinary incontinence and faecal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, et al. Incontinence: Volume 1—Basics and evaluation, 2nd international consultation on incontinence—Paris. Paris: Health Publications; 2005:255–312.

Jinbo AK, Stark M. Bowel and bladder management in children. In: Doughty DB, ed. Urinary and fecal incontinence: current management concepts. 3rd edn. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2006:491–545.

Kong AP, Stamos MJ. Anorectal complications: office diagnosis and treatment, part 1. Consultant. 2005;45(7):731–734.

Kong AP, Stamos MJ. Anorectal complications: office diagnosis and treatment, part 2. Consultant. 2005;45(7):735–738.

Kyle G, Prynn P. Bowel care. In: Getliffe K, Dolman M. Promoting continence: a clinical and research resource. 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Baillière Tindall; 2007:203–238.

Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(9):920–924.

Marieb EM, Hoehn K. Human anatomy and physiology, 8th edn. San Francisco: Pearson Benjamin Cummings, 2010.

Morrison G, Headon B, Gibson P. Update in inflammatory bowel disease. Australian Family Physician. 2009;38(12):956–961.

National Health and Medical Research Council, Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, early detection and management of colorectal cancer. The Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network, Sydney, 2005. Available at http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/cp106/cp106syn.htm.

New Zealand Cancer Registry, Cancer: new registrations and deaths 2007. Ministry of Health, Wellington, 2010. Available at http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/pagesmh/10173/$File/cancer-reg-deaths-2007.pdf.

Norton C, ed. Oxford handbook of gastrointestinal nursing. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Rogers J. Mainly children. In: Getliffe K, Dolman M. Promoting continence: a clinical and research resource. 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Baillière Tindall; 2007:113–136.

Toglia MR. Pathophysiology or anal incontinence, constipation and defecatory dysfunction. Obstet Gynaecol Clin N Am. 2009;36:659–671.

Zimmaro-Bliss D, Norton C. Conservative management of faecal incontinence. AJN. 2010;110(9):20–38.