Chapter Nineteen Abdomen

INTRODUCTION

Structures relevant to abdominal assessment include all of the abdominal organs and the abdominal wall. You will find other relevant anatomy and physiology in Chapters 18 and 20. Information relevant to abdominal examination in pregnancy is detailed in Chapter 28.

SURFACE LANDMARKS

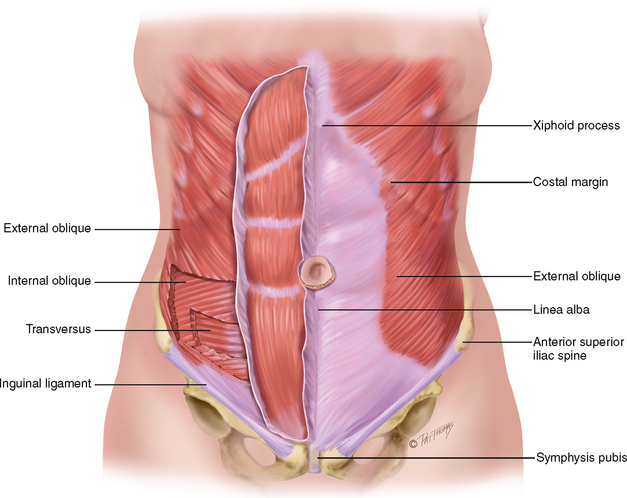

The abdomen is a large oval cavity extending from the diaphragm down to the brim of the pelvis. It is bordered at its back by the vertebral column and paravertebral muscles and at the sides and front by the lower rib cage and abdominal muscles (Fig 19.1). Four layers of large, flat muscles form the ventral abdominal wall. These are joined at the midline by a tendinous seam, the linea alba. One set, the rectus abdominis, forms a strip extending the length of the midline, and its edge is often palpable.

INTERNAL ANATOMY

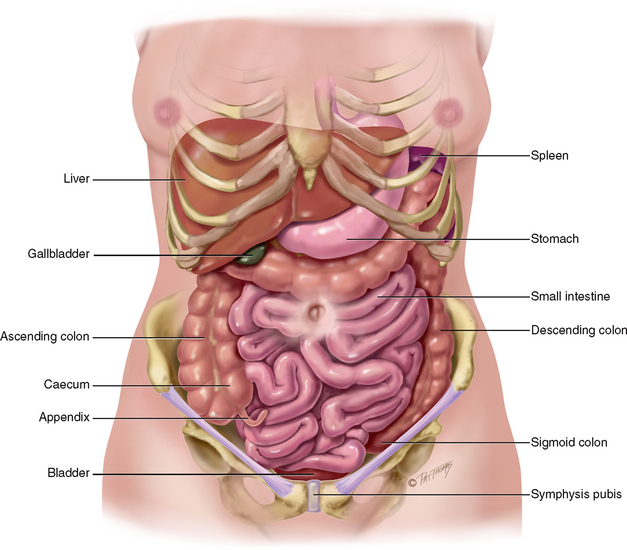

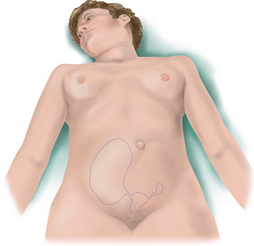

Inside the abdominal cavity, all the internal organs are called the viscera. It is important that you know the location of these organs so well that you could draw a map of them on the skin (Fig 19.2). You must be able to visualise each organ that you listen to or palpate through the abdominal wall.

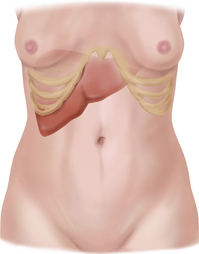

The solid viscera are those that maintain a characteristic shape (liver, pancreas, spleen, adrenal glands, kidneys, ovaries and uterus). The liver fills most of the right upper quadrant (RUQ) and extends over to the left midclavicular line. The lower edge of the liver and the right kidney may normally be palpable. The ovaries normally are palpable only on bimanual examination during the pelvic examination.

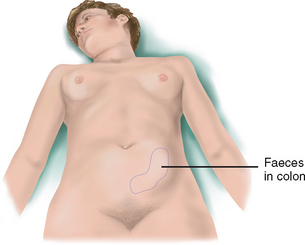

The shapes of the hollow viscera (stomach, gallbladder, small intestine, colon and bladder) depend on the contents. They usually are not palpable, although you may feel a colon distended with faeces or a bladder distended with urine. The stomach is just below the diaphragm, between the liver and spleen. The gallbladder rests under the posterior surface of the liver, just lateral to the right midclavicular line. Note that the small intestine is located in all four quadrants. It extends from the stomach’s pyloric valve to the ileocaecal valve in the right lower quadrant (RLQ), where it joins the colon. The small intestine is divided into three regions, the duodenum (approximately 25 cm long), the jejunum (approximately 1 m long) and the ileum (approximately 2 m long). The small intestine joins the large intestine at the ileocaecal valve. The large intestine is approximately 1.5 m long and extends from the ileum to the anus. It is divided into four major areas; the caecum, colon, rectum and anal canal. The colon is divided according to its position in the abdomen; the ascending colon, the transverse colon, the descending colon and the sigmoid colon. See Chapter 20 for detail about the anatomy of the anus and rectum.

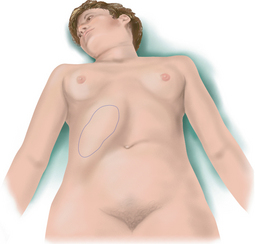

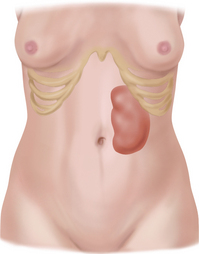

The spleen is a soft mass of lymphatic tissue on the posterolateral wall of the abdominal cavity, immediately under the diaphragm (Fig 19.3). It lies obliquely with its long axis behind and parallel to the tenth rib, lateral to the midaxillary line. Its width extends from the ninth to the eleventh rib, about 7 cm. It is not palpable. If it becomes enlarged, its lower pole moves downwards and towards the midline.

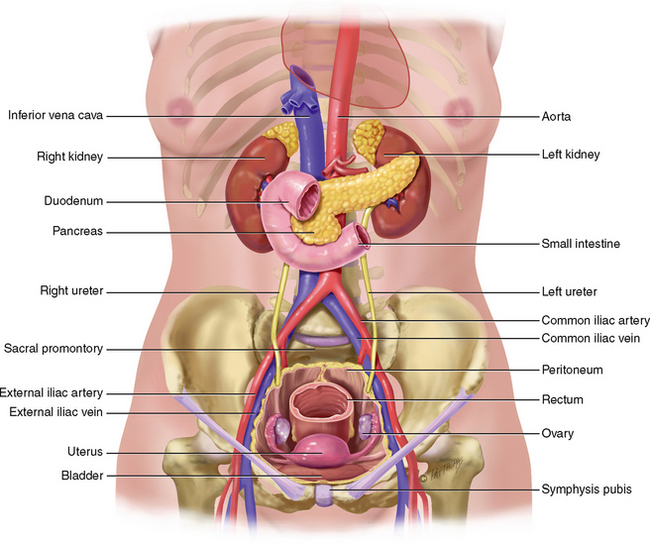

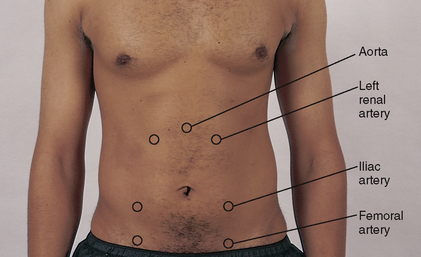

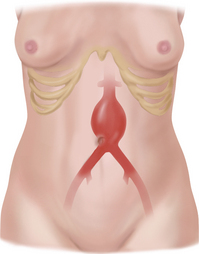

The aorta is just to the left of midline in the upper part of the abdomen (Fig 19.4). It descends behind the peritoneum and, at 2 cm below the umbilicus, it bifurcates into the right and left common iliac arteries opposite the fourth lumbar vertebra. You can palpate the aortic pulsations in the upper anterior abdominal wall. The right and left iliac arteries become the femoral arteries in the groin area. Their pulsations are easily palpated as well, at a point halfway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the symphysis pubis.

The pancreas is a soft, lobulated gland located behind the stomach. It stretches obliquely across the posterior abdominal wall to the left upper quadrant (LUQ).

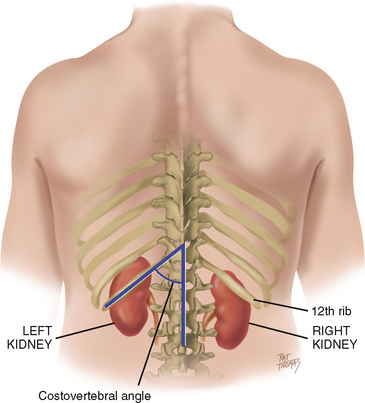

The bean-shaped kidneys are retroperitoneal, or posterior to the abdominal contents (Fig 19.5). They are well protected by the posterior ribs and musculature. The twelfth rib forms an angle with the vertebral column, the costovertebral angle. The left kidney lies here at the eleventh and twelfth ribs.

Because of the placement of the liver, the right kidney rests 1 to 2 cm lower than the left kidney and may sometimes be palpable.

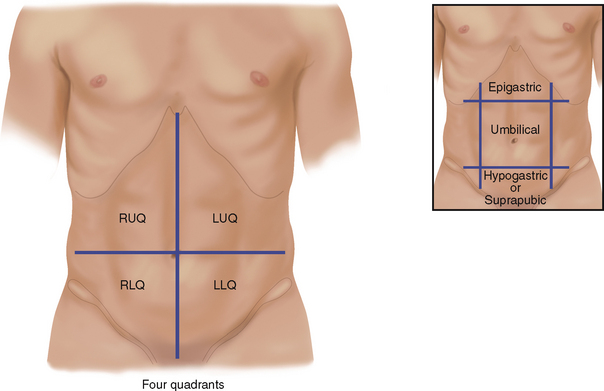

For convenience in description, the abdominal wall is divided into four quadrants by a vertical and a horizontal line bisecting the umbilicus (Fig 19.6). (An older, more complicated scheme divided the abdomen into nine regions. Although the old system generally is not used, some regional names persist, such as epigastric for the area between the costal margins, umbilical for the area around the umbilicus and hypogastric or suprapubic for the area above the pubic bone.)

The anatomical location of the organ by quadrants is:

| Right Upper Quadrant (RUQ) | Left Upper Quadrant (LUQ) |

|---|---|

| Liver | Stomach |

| Gallbladder | Spleen |

| Duodenum | Left lobe of liver |

| Head of pancreas | Body of pancreas |

| Right kidney and adrenal | Left kidney and adrenal |

| Hepatic flexure of colon | Splenic flexure of colon |

| Part of ascending and transverse colon | Part of transverse and descending colon |

| Right Lower Quadrant (RLQ) | Left Lower Quadrant (LLQ) | |

|---|---|---|

| Caecum | Part of descending colon | |

| Appendix | Sigmoid colon | |

| Right ovary and tube | Left ovary and tube | |

| Right ureter | Left ureter | |

| Right spermatic cord | Left spermatic cord | |

| Midline | ||

| Aorta | ||

| Uterus (if enlarged) | ||

| Bladder (if distended) | ||

DEVELOPMENTAL AND SOCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Infants and children

In the newborn, the umbilical cord shows prominently on the abdomen. It contains two arteries and one vein. The liver takes up proportionately more space in the abdomen at birth than in later life. In healthy term neonates, the lower edge may be palpated 0.5 to 2.5 cm below the right costal margin. Age-related values of expected liver span are listed in the Objective data section below. The urinary bladder is located higher in the abdomen than in the adult. It lies between the symphysis and the umbilicus. Also, during early childhood the abdominal wall is less muscular, so the appearance is rounded and the organs may be easier to palpate.

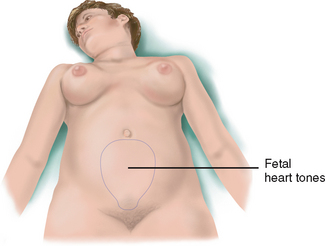

The pregnant female

Nausea and vomiting, or ‘morning sickness’, is an early sign of pregnancy for many pregnant women, starting between the first and second missed periods. The cause is unknown but may be due to hormone changes such as the production of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG). Another symptom is ‘acid indigestion’ or heartburn (pyrosis) caused by oesophageal reflux. Gastrointestinal motility decreases, which prolongs gastric emptying time. The decreased motility causes more water to be reabsorbed from the colon, which leads to constipation. The constipation, as well as increased venous pressure in the lower pelvis, may lead to haemorrhoids.

The enlarging uterus displaces the intestines upwards and posteriorly. Bowel sounds are diminished. The appendix is displaced upwards and to the right. Skin changes on the abdomen, such as striae and linea nigra, are discussed later in this chapter and in Chapter 17.

Late adulthood (65+ years)

Changes of ageing occur in the gastrointestinal system but do not significantly affect function as long as no disease is present.

• Salivation decreases, causing a dry mouth and a decreased sense of taste. Further changes are discussed in Chapter 16.

• Oesophageal emptying is delayed. This may result in a feeling of fullness after eating, dysphagia and gastro-oesophageal reflux disorder.

• Gastric acid secretion decreases with ageing. This may cause pernicious anaemia (because it interferes with vitamin B12 absorption), iron deficiency anaemia and malabsorption of calcium.

• The incidence of gallstones increases with age, occurring in 10% to 20% of middle-aged and older adults, being more common in females.

• Liver size decreases with age, particularly after 80 years, although most liver function remains normal. Drug metabolism by the liver is impaired, in part because by age 60 to 80 years blood flow through the liver is decreased by 55% to 60% (Katzung, 2006). Therefore, the liver metabolism that is responsible for the enzymatic oxidation, reduction and hydrolysis of drugs is substantially decreased with age. Prolonged liver metabolism causes increased side effects (e.g. older people taking benzodiazepines scored lower on functional status measures and had increased risk of hip fracture) (Bryant, Knights and Salerno, 2010).

• Older persons frequently report constipation. Of those older people who actually are constipated, two-thirds have slowed passage in the distal colon and delayed rectal emptying. Common causes of constipation include decreased physical activity, inadequate intake of water, a low-fibre diet, side effects of medications, irritable bowel syndrome, bowel obstruction, hypothyroidism, inadequate toilet facilities (i.e. difficulty ambulating to the toilet may cause the person to deliberately retain the stool until it becomes hard and difficult to pass).

SUBJECTIVE DATA

Abdominal assessment is commonly performed in conjunction with nutritional, mouth and throat assessment and/or assessment of bowel and bladder function. Therefore the focus of the abdominal assessment outlined below is primarily related to investigation of abdominal pain. You will need to adjust the questioning to fit with the purpose of the examination. For example, if the focus of the assessment is about bowel function you would include the questions related to bowel function; however, if the abdominal assessment is related to nutrition you would focus on the questions related to that area and expand the questions to include those related to eating, appetite etc.

| Assessment guidelines | Clinical signifcance and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| food intolerance (e.g. lactase defciency resulting in bloating or excessive gas after taking milk products). | |

Review pain assessment strategies and tools from Chapter 10. Location: Any abdominal pain? Please point to it.

• Is the pain in one spot or does it move around? Onset, duration, variation: How did it start? How long have you had it?

Quality: How would you describe the character: cramping (colic type), burning in pit of stomach, dull, stabbing, aching? Intensity: rate from 1–10. Aggravating/alleviating factors:

|

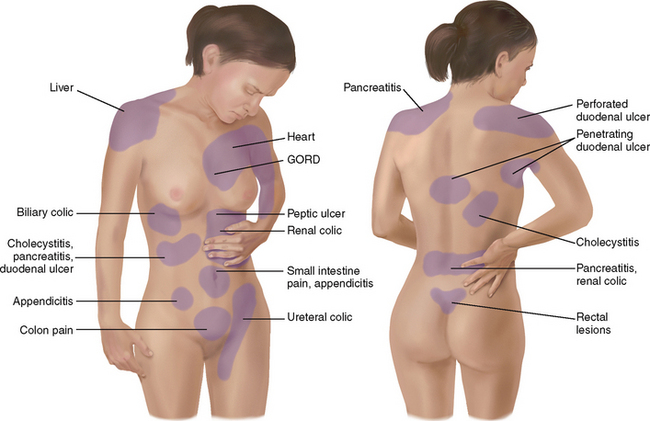

Abdominal pain may be visceral from an internal organ (dull, general, poorly localised), parietal from inflammation of overlying peritoneum (sharp, precisely localised, aggravated by movement) or referred from a disorder in another site (see Table 19.2). |

| Nausea/vomiting is a common side effect of many medications, with gastrointestinal disease, early pregnancy. | |

| Haematemesis occurs with stomach or duodenal ulcers and oesophageal varices. | |

| Consider food poisoning. | |

Detailed assessment of bowel function is covered in Chapter 20. Black stools may be tarry due to occult blood (melaena) from gastrointestinal bleeding or non-tarry from iron medications. Grey stools occur with hepatitis. Red blood in stools occurs with gastrointestinal bleeding or localised bleeding around the anus. |

|

| Peptic ulcer disease occurs with frequent use of non-steroidal anti-infammatory drugs (NSAIDs), alcohol, smoking and Helicobacter pylori infection. | |

| Additional history for infants and children | |

| This symptom is hard to assess with young children. Many conditions of unrelated organ systems are associated with vague abdominal pain (e.g. otitis media). Children cannot articulate specific symptoms and often focus on ‘the tummy’. Abdominal pain accompanies inflammation of the bowel, constipation, urinary tract infection and anxiety. |

OBJECTIVE DATA

Conduct the examination using the following sequence; inspection, auscultation, percussion and palpation. Note that this is a different sequence to other assessments.

TABLE 19.2 Common sites of referred abdominal pain

|

| When a person gives a history of abdominal pain, the pain’s location may not necessarily be directly over the involved organ. That is because the human brain has no felt image for internal organs. Rather, pain is referred to a site where the organ was located in fetal development. Although the organ migrates during fetal development, its nerves persist in referring sensations from the former location. The following are examples, not a complete list. |

| liver. Hepatitis may have mild to moderate, dull pain in right upper quadrant or epigastrium, along with anorexia, nausea, malaise, low-grade fever. |

| Oesophagus. Gastro-oesophageal refux disease (GORD) is a complex of symptoms of oesophagitis, including burning pain in midepigastrium or behind lower sternum that radiates upwards, or ‘heartburn’. Occurs 30 to 60 minutes after eating; aggravated by lying down or bending over. |

| Gallbladder. Cholecystitis is biliary colic, sudden pain in right upper quadrant that may radiate to right or left scapula, and which builds over time, lasting 2 to 4 hours, after ingestion of fatty foods, alcohol or caffeine. Associated with nausea and vomiting, and positive Murphy’s sign or sudden stop in inspiration with RUQ palpation. |

| Pancreas. Pancreatitis has acute, boring midepigastric pain radiating to the back and sometimes to the left scapula or fank, severe nausea and vomiting. |

| Duodenum. Duodenal ulcer typically has dull, aching, gnawing pain, does not radiate, may be relieved by food and may awaken the person from sleep. |

| Stomach. Gastric ulcer pain is dull, aching, gnawing epigastric pain, usually brought on by food, radiates to back or substernal area. Pain of perforated ulcer is burning epigastric pain of sudden onset that refers to one or both shoulders. |

| Appendix. Appendicitis typically starts as dull, diffuse pain in periumbilical region that later shifts to severe, sharp, persistent pain and tenderness localised in RLQ (McBurney’s point). Pain is aggravated by movement, coughing, deep breathing; associated with anorexia, then nausea and vomiting, fever. |

| kidney. Kidney stones prompt a sudden onset of severe, colicky fank or lower abdominal pain. |

| Small intestine. Gastroenteritis has diffuse, generalised abdominal pain, with nausea, diarrhoea. |

| Colon. Large bowel obstruction has moderate, colicky pain of gradual onset in lower abdomen, bloating. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has sharp or burning, cramping pain over a wide area; does not radiate. Brought on by meals, relieved by bowel movement. |

| procedures and normal findings | Clinical significance and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| GENERAL INSPECTION | |

| A comfortable person is relaxed quietly on the examining table and has a benign facial expression and slow, even respirations. | |

| INSPECT THE ABDOMEN | |

| Contour | |

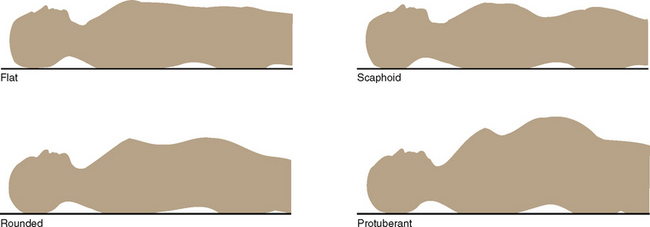

| Stand on the person’s right side and look down on the abdomen. Then stoop or sit to gaze across the abdomen. Your head should be slightly higher than the abdomen. Determine the profle from the rib margin to the pubic bone. The contour describes the nutritional state and normally ranges from fat to rounded (Fig 19.7). | Scaphoid abdomen, protuberant abdomen, abdominal distension (see also Table 19.1). |

The abdomen should be symmetrical bilaterally (Fig 19.8). Note any localised bulging, visible mass or asymmetric shape. Even small bulges are highlighted by shadow. Step to the foot of the examination table to recheck symmetry. |

Hernia–protrusion of abdominal viscera through abnormal opening in muscle wall (see Table 19.3). |

| Ask the person to take a deep breath to further highlight any change. Ask the person to place their chin on their chest and raise their head off the pillow. The abdomen should stay smooth and symmetrical. | Note any localised bulging. Hernia, enlarged liver or spleen may show. |

| Umbilicus | |

| Normally the umbilicus is midline and inverted, with no sign of discolouration, inflammation or hernia. It becomes everted and pushed upwards with pregnancy. | Everted with ascites, or underlying mass (see Table 19.1). |

| The umbilicus is a common site for skin piercings in young women. The site should not be red or crusted. | |

| Skin | |

| The surface is smooth and even, with homogeneous colour. This is a good area to judge skin colour because it is often protected from sun. | |

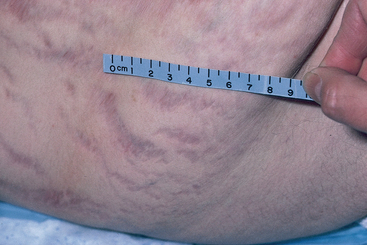

| One common pigment change is striae (lineae albicantes), silvery white, linear, jagged marks about 1 to 6 cm long (Fig 19.9). They occur when elastic fibres in the reticular layer of the skin are broken after rapid or prolonged stretching, as in pregnancy or excessive weight gain. Recent striae are pink or blue; then they turn silvery white. | |

| Pigmented naevi (moles), circumscribed brown macular or papular areas, are common on the abdomen. | Unusual colour or change in shape of mole (see Ch 17). |

| Petechiae. | |

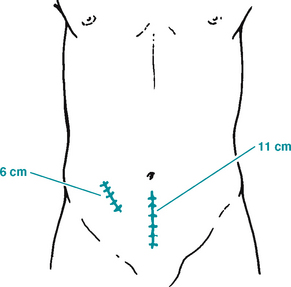

| Normally, no lesions are present, although you may note well-healed surgical scars. If a scar is present, draw its location in the person’s record, indicating the length in centimetres (Fig 19.10). (Note, a person may forget a past operation while providing the history. If you note a scar now, ask about it.) | |

| Veins are not usually seen, but a fine venous network may be visible in thin people. | Prominent, dilated veins occur with portal hypertension, cirrhosis, ascites or vena caval obstruction. Veins are more visible with malnutrition as a result of thinned adipose tissue. |

| Good skin turgor reflects healthy nutrition. Gently pinch up a fold of skin; then release. Note how long it takes the skin to return to original position. | Slow return to the original position, referred to as ‘poor turgor’, occurs with dehydration, which often accompanies gastrointestinal disease. |

| pulsation or movement | |

| Normally you may see the pulsations from the aorta beneath the skin in the epigastric area, particularly in thin persons. Respiratory movement also shows in the abdomen, particularly in males. Finally, waves of peristalsis may be visible in very thin persons. They ripple slowly and obliquely across the abdomen. | Marked pulsation of aorta occurs with widened pulse pressure (e.g. hypertension, aortic insufficiency, thyrotoxicosis) and with aortic aneurysm. |

| Marked visible peristalsis, together with a distended abdomen, indicates intestinal obstruction. | |

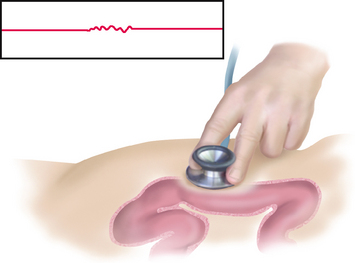

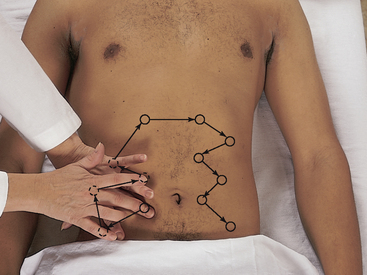

| AUSCULTATE BOWEL SOUNDS | |

| Depart from the usual examination sequence and auscultate the abdomen next. This is done because percussion and palpation can increase peristalsis, which would give a false interpretation of bowel sounds. Use the diaphragm endpiece because bowel sounds are relatively high pitched. Hold the stethoscope lightly against the skin; pushing too hard may stimulate more bowel sounds (Fig 19.11). It is usual practice to begin in the RLQ at the ileocaecal valve area because bowel sounds are normally always present here. If bowel sounds are heard in one quadrant it is likely that they will be present throughout the abdomen (Baid, 2009). | |

| Bowel sounds | |

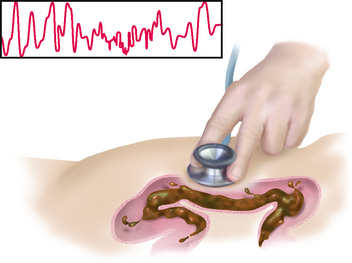

You should listen until you hear bowel sounds—then note their character and frequency. There is no accepted time that you should listen for bowel sounds— just listen until you hear them. Bowel sounds originate from the movement of air and fuid through the small intestine. Depending on the time elapsed since eating, a wide range of normal sounds can occur. Bowel sounds are high pitched, gurgling, cascading sounds, occurring irregularly anywhere from 5 to 30 times per minute. Do not bother to count them. Judge if they are normal, hypoactive or hyperactive. One type of hyperactive bowel sounds is fairly common. This is the hyper-peristalsis when you feel your ‘stomach growling’, termed borborygmus. A perfectly ‘silent abdomen’ is uncommon. From the literature it appears that best practice is to listen for at least 5 minutes if bowel sounds are not heard initially (Baid, 2009). |

Two distinct patterns of abnormal bowel sounds may occur: 1 hyperactive sounds are loud, high-pitched, rushing, tinkling sounds that signal increased motility. 2 hypoactive or absent sounds follow abdominal surgery or with inflammation of the peritoneum (see Table 19.4). The fnding of absent bowel sounds may indicate the development of a paralytic ileus and the person should be referred to a medical practitioner for further assessment if this is a new fnding or the person has other symptoms such as abdominal pain, abdominal distension, nausea and vomiting (Baid, 2009). |

| PERCUSS GENERAL TYMPANY | |

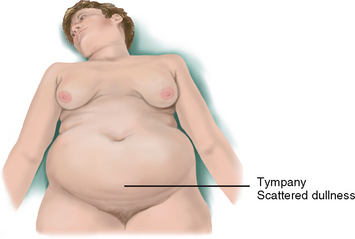

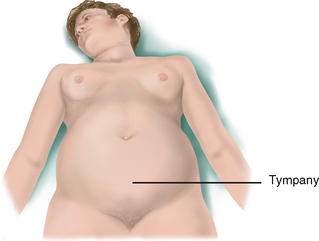

| Percuss to assess the relative density of abdominal contents, to locate organs and to screen for abnormal fluid or masses. | |

| General tympany | |

| First, percuss lightly in all four quadrants to determine the prevailing amount of tympany and dullness (Fig 19.12). Move clockwise. Tympany should predominate because air in the intestines rises to the surface when the person is supine. | |

| PALPATE SURFACE AND DEEP AREAS | |

| Perform palpation to judge the size, location and consistency of an abnormal mass or tenderness. Review comfort measures at the beginning of this section. Because most people are naturally inclined to protect the abdomen, you need to use additional measures to enhance complete muscle relaxation. | |

| Holding the hand high and pointing down could make the person tense up. | |

| Light and deep palpation | |

| Begin with light palpation. With the first four fingers close together, depress the skin about 1 cm (Fig 19.13). Make a gentle rotary motion, sliding the fingers and skin together. Then lift the fingers (do not drag them) and move clockwise to the next location around the abdomen. The objective here is not to search for masses but to form an overall impression of the skin surface and superfcial musculature. Save the examination of any identified tender areas until last. This method avoids pain and the resulting muscle rigidity that would obscure deeper palpation later in the examination. | Muscle guarding. Rigidity. Large masses. Tenderness. |

| As you circle the abdomen, discriminate between voluntary muscle guarding and involuntary rigidity. Voluntary guarding occurs when the person is cold, tense or ticklish. It is bilateral, and you will feel the muscles relax slightly during exhalation. Use the relaxation measures to try to eliminate this type of guarding, or it will interfere with deep palpation. If the rigidity persists, it is probably involuntary. | Involuntary rigidity is a constant board-like hardness of the muscles. It is a protective mechanism accompanying acute inflammation of the peritoneum. It may be unilateral, and the same area usually becomes painful when the person increases intraabdominal pressure by attempting a sit-up. |

| Now perform deep palpation using the technique described earlier, but push down about 5 to 8 cm (Fig 19.14). Moving clockwise, explore the entire abdomen. The objective of deep palpation is to identify masses and organs (location, shape and size). | |

| To overcome the resistance of a very large or obese abdomen, use a bimanual technique. Place your two hands on top of each other (Fig 19.15). The top hand does the pushing; the bottom hand is relaxed and can free to focus on the sense of palpation. With either technique, note the location, size, consistency and mobility of any palpable organs and the presence of any abnormal enlargement, tenderness or masses. | |

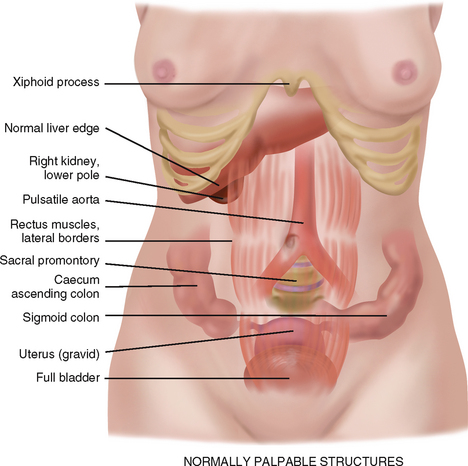

| Making sense of what you are feeling is more difficult than it looks. Inexperienced examiners complain that the abdomen ‘all feels the same’, as if they are pushing their hand into a soft sofa cushion. It helps to memorise the anatomy and visualise what is under each quadrant as you palpate. Also remember that some structures are normally palpable, as illustrated in Figure 19.16. | Tenderness occurs with local inflammation, with inflammation of the peritoneum or underlying organ and with an enlarged organ whose capsule is stretched. |

| Mild tenderness is normally present when palpating the sigmoid colon. Any other tenderness should be investigated. | Clinical alert: if the person experiences any significant abdominal tenderness stop the examination and refer the person to a medical practitioner for further assessment. |

| DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS | |

| The infant | |

| Inspection. The contour of the abdomen is protuberant because of the immature abdominal musculature. The skin contains a fine, superfcial venous pattern. | A scaphoid shape occurs with dehydration. |

| This may be visible in lightly pigmented children up to the age of puberty. | Dilated veins may indicate underlying abdominal pathology such as liver enlargement. |

Inspect the umbilical cord throughout the neonatal period. At birth, it is white and contains two umbilical arteries and one vein surrounded by mucoid connective tissue, called Wharton’s jelly. The umbilical stump dries within a week, hardens and falls off by 10 to 14 days. Skin covers the area by 3 to 4 weeks. The abdomen should be symmetrical, although two bulges are common. You may note an umbilical hernia. It appears at 2 to 3 weeks and is especially prominent when the infant cries. The hernia reaches maximum size at 1 month (up to 2.5 cm) and usually disappears by 1 year. Another common variation is diastasis recti, a separation of the rectus muscles with a visible bulge along the midline. The abdomen shows respiratory movement. The only other abdominal movement you should note is occasional peristalsis, which may be visible because of the thin musculature. |

The presence of only one artery signals the risk of congenital defects. Drainage after cord falls off. Refer any umbilical hernia larger than 2.5 cm (see Table 19.3); continuing to grow after 1 month. Refer diastasis recti lasting more than 6 years. Marked peristalsis suggests pyloric stenosis (see Table 19.4). |

| Auscultation. Auscultation yields only bowel sounds, the metallic tinkling of peristalsis. | |

| Percussion. Percussion elicits tympany over the stomach (the infant swallows some air with feeding). Percussing the spleen is not done. The abdomen sounds tympanitic, although it is normal to percuss dullness over the bladder. This dullness may extend up to the umbilicus. | |

| Palpation. Aid palpation by. exing the baby’s knees with one hand while palpating with the other (Fig 19.17). Alternatively, you may hold the upper back and. ex the neck slightly with one hand. Offer a paci.er to a crying baby. | |

Under age 4 years, the abdomen looks protuberant when the child is both supine and standing. After age 4 years, the potbelly remains when standing because of lumbar lordosis, but the abdomen looks fat when supine. Normal movement on the abdomen includes respirations, which remain abdominal until 7 years of age. |

|

| To palpate the abdomen, position the young child on the parent’s lap as you sit knee-to-knee with the parent (Fig 19.18). Flex the child’s knees up and elevate the head slightly. The child can ‘pant like a dog’ to further relax abdominal muscles. Hold your entire palm fat on the abdominal surface for a moment before starting palpation. This accustoms the child to being touched. If the child is very ticklish, hold their hand under your own as you palpate or apply the stethoscope and palpate around it. | |

| Because of the thinner, softer abdominal wall, the organs may be easier to palpate (in the absence of obesity). | Abdominal rigidity with acute abdominal conditions is less common in the older person. |

| With an acute abdomen, the older person often complains of less pain than a younger person would. | |

| FURTHER OBJECTIVE ASSESSMENT FOR ADVANCED PRACTICE | |

| The assessments that are described in the following sections require advanced skill and scope of practice. Nurses working in specialist settings and some community nurses would need to develop these skills. | |

| Preparation | Equipment needed |

| Same preparation as previously described. | Small centimetre ruler |

| Skin-marking pen | |

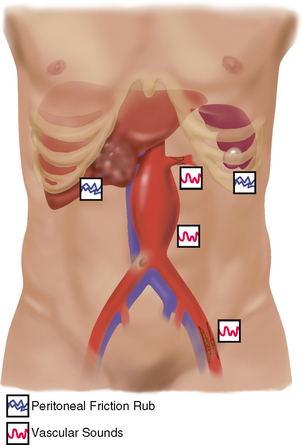

| Auscultate vascular sounds | |

| Vascular sounds | |

| As you listen to the abdomen for bowel sounds, note the presence of any vascular sounds or bruits. Using frmer pressure, listen over the aorta, renal arteries, iliac and femoral arteries, especially in people with hypertension (Fig 19.19). There should be no bruits present. | Note location, pitch and timing of a vascular sound. A systolic bruit is a pulsatile blowing sound and occurs with stenosis or occlusion of an artery. Venous hum and peritoneal friction rub are rare (see Table 19.5). |

| Percuss general tympany, liver span and splenic dullness | |

| Percuss to assess the relative density of abdominal contents, to locate organs and to screen for abnormal fuid or masses. | |

| General tympany | |

| First, percuss lightly in all four quadrants to determine the prevailing amount of tympany and dullness (see Fig 19.12). Move clockwise. Tympany should predominate because air in the intestines rises to the surface when the person is supine. | |

| Liver span | |

| Next, percuss to map out the boundaries of certain organs. Measure the height of the liver in the right midclavicular line. (For a consistent placement of the midclavicular line landmark, remember to palpate the acromioclavicular and the sternoclavicular joints and judge the line at a point midway between the two.) | |

| Begin in the area of lung resonance, and percuss down the midclavicular line the interspaces of the ribs until the sound changes to a dull quality (Fig 19.20). Mark the spot, usually in the fifth intercostal space. Then find abdominal tympany and percuss up the midclavicular line. Mark where the sound changes from tympany to a dull sound, normally at the right costal margin. | |

| Measure the distance between the two marks; the normal liver span in the adult ranges from 6 to 12 cm (Fig 19.21). The height of the liver span correlates with the height of the person; taller people have longer livers. Also males have a larger liver span than females of the same height. Overall, the mean liver span is 10.5 cm for males and 7 cm for females. | An enlarged liver span indicates liver enlargement or hepatomegaly. Accurate detection of liver borders is confused by dullness above the ffth intercostal space, which occurs with lung disease (e.g. pleural effusion or lung consolidation). Accurate detection at the lower border is confused when dullness is pushed up with ascites or pregnancy or with gas distension in the colon, which obscures lower border. |

| One variation occurs in people with chronic emphysema, in which the liver is displaced downwards by the hyperinfated lungs. Although you hear a dull percussion note well below the right costal margin, the overall span is still within normal limits. | |

| Clinical estimation of liver span is important to screen for hepatomegaly and to monitor changes in liver size. However, this measurement is a gross estimate; the liver span may be underestimated because of inaccurate detection of the upper border. | |

| Scratch test. One fnal technique is the scratch test, which may help defne the liver border when the abdomen is distended or the abdominal muscles are tense. Place your stethoscope over the liver. With one fngernail, scratch short strokes over the abdomen, starting in the RLQ and moving progressively up towards the liver (Fig 19.22). When the scratching sound in your stethoscope becomes magnifed, you will have crossed the border from over a hollow organ to over a solid one. | |

| Splenic dullness | |

| Often the spleen is obscured by stomach contents, but you may locate it by percussing for a dull note from the 9th to 11th intercostal space just behind the left midaxillary line (Fig 19.23). The area of splenic dullness is normally not wider than 7 cm in the adult and should not encroach on the normal tympany over the gastric air bubble. | A dull note forwards of the midaxillary line indicates enlargement of the spleen, as occurs with mononucleosis, trauma and infection. |

| Now percuss in the lowest interspace in the left anterior axillary line. Tympany should result. Ask the person to take a deep breath and then percuss. Normally, tympany remains through full inspiration. | At the anterior axillary line, a change in percussion from tympany to a dull sound with full inspiration is a positive spleen percussion sign, indicating splenomegaly. This method will detect mild to moderate splenomegaly before the spleen becomes palpable, as in mononucleosis, malaria or hepatic cirrhosis. |

| Costovertebral angle tenderness | |

| Indirect first percussion causes the tissues to vibrate instead of producing a sound. To assess the kidney, place one hand over the 12th rib at the costovertebral angle on the back (Fig 19.24). Thump that hand with the ulnar edge of your other first. The person normally feels a thud but no pain. (Although this step is explained here with percussion techniques, its usual sequence in a complete examination is with thoracic assessment, when the person is sitting up and you are standing behind.) | Sharp pain occurs with infammation of the kidney or paranephric area. |

| Special procedures | |

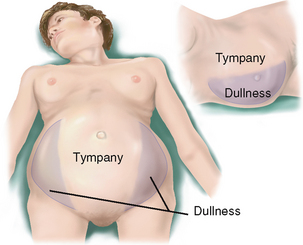

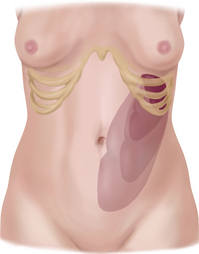

| At times, you may suspect that a person has ascites (free fluid in the peritoneal cavity) because of a distended abdomen, bulging flanks and an umbilicus that is protruding and displaced downwards. You can differentiate ascites from gaseous distension by performing two percussion tests. | Ascites occurs with heart failure, portal hypertension, cirrhosis, hepatitis, pancreatitis and cancer. |

| Fluid wave. First, test for a fluid wave by standing on the person’s right side. Place the ulnar edge of another examiner’s hand or the patient’s own hand firmly on the abdomen in the midline (Fig 19.25). (This will stop transmission across the skin of the upcoming tap.) Place your left hand on the person’s right flank. With your right hand, reach across the abdomen and give the left flank a firm strike. | |

| If ascites is present, the blow will generate a fuid wave through the abdomen and you will feel a distinct tap on your left hand. If the abdomen is distended from gas or adipose tissue, you will feel no change. | A positive fluid wave test occurs with large amounts of ascitic fluid. |

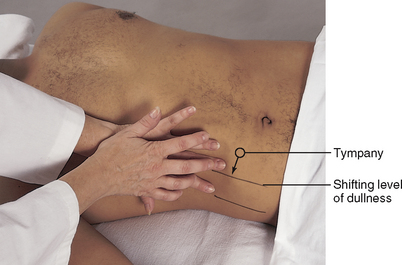

| Shifting dullness. The second test for ascites is percussing for shifting dullness. In a supine person, ascitic fuid settles by gravity into the fanks, displacing the air-flled bowel upwards. You will hear a tympanitic note as you percuss over the top of the abdomen because gas-flled intestines foat over the fuid (Fig 19.26). Then percuss down the side of the abdomen. If fuid is present, the note will change from tympany to dull as you reach its level. Mark this spot. | |

| Now turn the person onto the right side (roll the person towards you) (Fig 19.27). The fuid will gravitate to the dependent (in this case, right) side, displacing the lighter bowel upwards. Begin percussing the upper side of the abdomen and move downwards. The sound changes from tympany to a dull sound as you reach the fluid level, but this time the level of dullness is higher, upwards towards the umbilicus. This shifting level of dullness indicates the presence of fluid. | Shifting dullness is positive with a large volume of ascitic fuid: it will not detect less than 500 mL of fuid. |

| Both tests, fuid wave and shifting dullness, are not completely reliable. Ultrasound study is the defnitive tool. | |

| Palpate surface and deep areas | |

| Perform palpation to judge the size, location and consistency of certain organs and to screen for an abnormal mass or tenderness. Review comfort measures at beginning of this section. Because most people are naturally inclined to protect the abdomen, you need to use additional measures to enhance complete muscle relaxation. | |

| Liver | |

| Next, palpate for specific organs, beginning with the liver in the RUQ (Fig 19.28). Place your left hand under the person’s back parallel to the 11th and 12th ribs and lift up to support the abdominal contents. Place your right hand on the RUQ, with fngers parallel to the midline. Push deeply down and under the right costal margin. Ask the person to take a deep breath. It is normal to feel the edge of the liver bump your fingertips as the diaphragm pushes it down during inhalation. It feels like a frm regular ridge. Often, the liver is not palpable and you feel nothing firm. | Except with a depressed diaphragm, a liver palpated more than 1 to 2 cm below the right costal margin is enlarged. Record the number of centimetres it descends and note its consistency (hard, nodular) and tenderness (see Table 19.6). |

| Hooking technique. An alternative method of palpating the liver is to stand up at the person’s shoulder and swivel your body to the right so that you face the person’s feet (Fig 19.29). Hook your fngers over the costal margin from above. Ask the person to take a deep breath. Try to feel the liver edge bump your fingertips. | |

| Spleen | |

The spleen is not normally palpable and must be enlarged three times its normal size to be felt. If you feel an enlarged spleen refer the person to a medical practitioner, do not proceed with the palpation. To search for it, reach your left hand over the abdomen and behind the left side at the 11th and 12th ribs (Fig 19.30, A). Lift up for support. Place your right hand obliquely on the LUQ with the fngers pointing towards the left axilla and just inferior to the rib margin. Push your hand deeply down and under the left costal margin and ask the person to take a deep breath. You should feel nothing firm. |

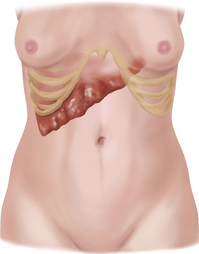

The spleen enlarges with mononucleosis and trauma (see Table 19.6). An enlarged spleen is friable and can rupture easily with overpalpation. Describe the number of centimetres it extends below the left costal margin. |

| A | |

| When enlarged, the spleen slides out and bumps your fngertips. It can grow so large that it extends into the lower quadrants. When this condition is suspected, start low so you will not miss it. An alternative position is to roll the person onto their right side to displace the spleen more forwards and downwards (Fig 19.30, B). Then palpate as described earlier. | |

| B | |

| Kidneys | |

| Search for the right kidney by placing your hands together in a ‘duck-bill’ position at the person’s right flank (Fig 19.31, A). Press your two hands together firmly (you need deeper palpation than that used with the liver or spleen) and ask the person to take a deep breath. In most people, you will feel no change. Occasionally, you may feel the lower pole of the right kidney as a round, smooth mass slide between your fngers. Either condition is normal. | Enlarged kidney. Kidney mass. |

| A | |

| The left kidney sits 1 cm higher than the right kidney and is not palpable normally. Search for it by reaching your left hand across the abdomen and behind the left fank for support (Fig. 19.31, B). Push your right hand deep into the abdomen and ask the person to breathe deeply. You should feel no change with the inhalation. | |

| B | |

| Aorta | |

| Using your opposing thumb and fingers, palpate the aortic pulsation in the upper abdomen slightly to the left of midline (Fig 19.32). Normally, it is 2.5 to 4 cm wide in the adult and pulsates in an anterior direction. | Widened with aneurysm (see Tables 19.5 and 19.6). |

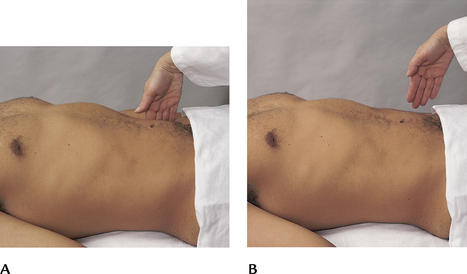

Other procedures for advanced practice nurses Rebound tenderness (Blumberg’s sign). Assess rebound tenderness when the person reports abdominal pain or when you elicit tenderness during palpation. Choose a site away from the painful area. Hold your hand at 90 degrees, or perpendicular, to the abdomen. Push down slowly and deeply; then lift up quickly (Figs 19.33, A, B). This makes structures that are indented by palpation rebound suddenly. A normal, or negative, response is no pain on release of pressure. Perform this test at the end of the examination, because it can cause severe pain and muscle rigidity. |

Pain on release of pressure confirms rebound tenderness, which is a reliable sign of peritoneal inflammation. Peritoneal inflammation accompanies appendicitis. |

| Inspiratory arrest (Murphy’s sign). Normally, palpating the liver causes no pain. In a person with inflammation of the gallbladder, or cholecystitis, pain occurs. Hold your fngers under the liver border. Ask the person to take a deep breath. A normal response is to complete the deep breath without pain. | When the test is positive, as the descending liver pushes the inflamed gallbladder onto the examining hand, the person feels sharp pain and abruptly stops inspiration midway. |

| Iliopsoas muscle test. Perform the iliopsoas muscle test when the acute abdominal pain of appendicitis is suspected. With the person supine, lift the right leg straight up, flexing at the hip (Fig 19.34); then push down over the lower part of the right thigh as the person tries to hold the leg up. When the test is negative, the person feels no change. | When the iliopsoas muscle is infamed (which occurs with an infamed or perforated appendix), pain is felt in the right lower quadrant. |

| Obturator test. The obturator test is also performed when appendicitis is suspected. With the person supine, lift the right leg, flexing at the hip and 90 degrees at the knee (Fig 19.35). Hold the ankle and rotate the leg internally and externally. A negative or normal response is no pain. | A perforated appendix irritates the obturator muscle, producing pain. |

| The infant | |

The liver flls the RUQ. It is normal to feel the liver edge at the right costal margin or 1 to 2 cm below. Normally, you may palpate the spleen tip and both kidneys and the bladder. Also easily palpated are the caecum in the RLQ, and the sigmoid colon, which feels like a sausage in the left inguinal area. Make note of the newborn’s first stool, a sticky, greenish-black meconium stool within 24 hours of birth. By the fourth day, stools of breast-fed babies are golden-yellow, pasty and smell like sour milk, whereas those of formula-fed babies are brown-yellow, frmer and more faecal smelling. |

|

| The child | |

The liver remains easily palpable 1 to 2 cm below the right costal margin. The edge is soft and sharp and moves easily. On the left, the spleen is also easily palpable with a soft, sharp, movable edge. Usually you can feel 1 to 2 cm of the right kidney and the tip of the left kidney. Percussion of the liver span measures about 3.5 cm at age 2 years, 5 cm at age 6 years and 6 to 7 cm during adolescence. In assessing abdominal tenderness, remember that the young child often answers this question affrmatively no matter how the abdomen actually feels. Use objective signs to aid assessment, such as a cry changing in pitch as you palpate, facial grimacing, moving away from you and guarding. The school-age child has a slim abdominal shape as they lose the potbelly. This slimming trend continues into adolescence. The adolescent may be embarrassed with exposure of the abdomen, and adequate draping is necessary. The physical findings are the same as those listed for the adult. |

TABLE 19.3 Abnormalities on inspection

TABLE 19.4 Abnormal bowel sounds

TABLE 19.5 Abdominal friction rubs and vascular sounds

TABLE 19.1 Abdominal distension*

|

| Obesity |

|

| Air or gas |

|

| Ascites |

Inspection. Single curve. Everted umbilicus. Bulging fanks when supine. Taut glistening skin, recent weight gain, increase in abdominal girth. Auscultation. Normal bowel sounds over intestines. Diminished over ascitic fluid. Percussion. Tympany at top where intestines float. Dull over fluid. Produces fluid wave and shifting dullness. Palpation. Taut skin and increased intraabdominal pressure limit palpation. |

|

| Ovarian cyst (large) |

Inspection. Curve in lower half of abdomen, midline. Everted umbilicus. Auscultation. Normal bowel sounds over upper abdomen where intestines pushed superiorly. Percussion. Top dull over fluid. Intestines pushed superiorly. Large cyst produces fluid wave and shifting dullness. Palpation. Transmits aortic pulsation while ascites does not. |

|

| Pregnancy† |

|

| Faeces |

|

| Tumour |

* A mnemonic device to recall the common causes of abdominal distension is the seven Fs: fat, flatus, fluid, fetus, faeces, fetal growth and fibroid.

† Obviously a normal finding, pregnancy is included for comparison of conditions causing abdominal distension.

TABLE 19.6 Abnormalities on palpation of enlarged organs

|

| Enlarged liver |

|

| Enlarged nodular liver |

| An enlarged and nodular liver occurs with late portal cirrhosis, metastatic cancer or tertiary syphilis. |

|

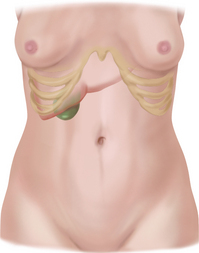

| Enlarged gallbladder |

An enlarged, tender gallbladder suggests acute cholecystitis. Feel it behind the liver border as a smooth and firm mass like a sausage, although it may be difficult to palpate because of involuntary rigidity of abdominal muscles. The area is exquisitely painful to fst percussion, and inspiratory arrest (Murphy’s sign) is present. An enlarged, nontender gallbladder also feels like a smooth, sausage-like mass. It occurs when the gallbladder is filled with stones, as with common bile duct obstruction. |

|

| enlarged spleen |

| Because any enlargement superiorly is stopped by the diaphragm, the spleen enlarges down and to the midline. When extreme, it can extend down to the left pelvis. It retains the splenic notch on the medial edge. When splenomegaly occurs with acute infections (mononucleosis), it is moderately enlarged and soft, with rounded edges. When the result of a chronic cause, the enlargement is firm or hard, with sharp edges. An enlarged spleen is usually not tender to palpation; it is tender only if the peritoneum is also inflamed. |

|

| Enlarged kidney |

| Enlarged with hydronephrosis, cyst or neoplasm. May be difficult to distinguish an enlarged kidney from an enlarged spleen because they have a similar shape. Both extend forwards and down. However, the spleen may have a sharp edge, whereas the kidney never does. The spleen retains the splenic notch, whereas the kidney has no palpable notch. Percussion over the spleen is dull, whereas over the kidney it is tympanitic because of the overriding bowel. |

|

| Aortic aneurysm |

| Most aortic aneurysms (more than 95%) are located below the renal arteries and extend to the umbilicus. About 80% of these are palpable during routine physical examination and feel like a pulsating mass in the upper abdomen just to the left of midline. You will hear a bruit. Femoral pulses are present but decreased. Additional information on abdominal aneurysm is illustrated in Table 19.5. |

Promoting a health lifestyle Keeping your liver healthy

The liver is the largest organ in the body. It has an immense capacity to heal and regenerate, but that capacity is not infinite. Unfortunately, signs of severe liver damage or disease usually do not become apparent until the liver has been significantly harmed. The best protection for the liver is prevention!

There are many things an individual can do to protect the liver:

• Be aware of your environment. Be careful with aerosol cleaners. Make sure rooms are well ventilated. Wear a mask, hat or protective clothing when using insecticides, fungicides, paint or other toxic chemicals. The liver can be damaged by what you breathe or absorb through your skin.

• Watch your diet and weight. Obesity can cause a condition called nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, which may include cirrhosis.

• Use medications wisely. Use prescription and over-the-counter medications only when needed. Be sure to take only the recommended doses.

• Do not mix medications without consulting a healthcare provider. Mixing certain medications can form toxic compounds that can cause liver damage. Be certain that all medications, including over-the-counter and herbal preparations, are reviewed with patients.

• Drink alcohol in moderation. The current Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol (National Health & Medical Research Council, 2009) recommend that healthy men and women drink no more than two standard drinks on any day to reduce the lifetime risk of harm from alcohol-related disease or injury.

• Do not mix medications and alcohol. Certain drugs can be toxic to the liver even if a person drinks in moderation.

• Do not use illegal drugs. Cocaine is one of many illegal drugs known to cause liver damage.

• Get vaccinated. A vaccine is available for both hepatitis A and hepatitis B.

• Be aware of your risk for hepatitis. The three leading causes of hepatitis are hepatitis A, hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection.

• Hepatitis A is primarily spread through food or water contaminated by faeces from an infected person. In Australia and New Zealand hepatitis A is more common among specific groups of people including:

• Hepatitis B is one of the most common infectious diseases in the world and is a serious public health problem. It is primarily spread through contact with infected blood or body fluids (including saliva, semen, vaginal secretions and breast milk). The most common ways that hepatitis is spread include:

• Hepatitis C is primarily spread through contact with infected blood by injecting drug users. Other ways in which hepatitis C can be spread include:

You can get more information about liver health and hepatitis from the following websites:

Australian Liver Foundation: http://www.liver.org.au/

Hepatitis Australia: http://www.hepatitisaustralia.com/index.html

Hepatitis Foundation of New Zealand: http://www.hepfoundation.org.nz/

DOCUMENTATION AND CRITICAL THINKING

FOCUSED ASSESSMENT: CLINICAL CASE STUDY 1

George E is a 58-year-old unemployed man with chronic alcoholism who enters the chemical dependency treatment centre.

Subjective

George has lived by himself for many years following a divorce and has no contact with his former wife and their three adult children. States that for the last 6 months he has been drinking 1 bottle of whisky/day. States that he has no appetite and can’t be bothered cooking. Has fatigue and weakness.

Objective

Inspection: Appears older than stated age. Oriented, although verbal response time slowed. Weight loss of 5.4 kg in last 3 months.

Abdomen protuberant, symmetrical, no visible masses. Poor skin turgor. Dilated venous pattern over abdominal wall.

Auscultation: Bowel sounds present.

Palpation: Soft. Obvious liver enlargement below right costal margin—non-tender on light palpation. No other masses palpated.

FOCUSED ASSESSMENT: CLINICAL CASE STUDY 2

Dan G is a 17-year-old male high school student who enters the emergency department with a history of abdominal pain for 2 days.

Subjective

Two days ago Dan noted general abdominal pain in umbilical region. Now pain is sharp and severe, and Dan points to location in right lower quadrant. No bowel movement for 2 days. Nausea and vomiting off and on for 1 day. He says that no one else in his household has these symptoms and that he has only eaten home prepared meals in the last few days.

Objective

Inspection: BP 112/70, temp 38°C, pulse 116, resp 18.

Lying on side with knees drawn up under chin. Resists any movement. Face tight and occasionally grimacing. Cries out with any sudden movement.

Auscultation: No bowel sounds present.

Palpation: Abdominal wall is rigid and board-like. Extreme tenderness to palpation in RLQ—no further assessment undertaken until medical consultation.

Baid H. A critical review of auscultating bowel sounds. British Journal of Nursing. 2009;18(18):1125–1129.

Banning M. Helicobacter pylori: Pathophysiology, assessment and treatment. Gastrointest Nurs. 2006;4:28–33.

Bryant B, Knights K, Salerno E. Pharmacology for health professionals. Chatswood, NSW: Elsevier, 2010.

Fox M, Forgacs I. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Br Med J. 2006;332:88–93.

Jacobson BC, et al. Body-mass index and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in women. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2340–2348. 2405–2408

Jenkins G, Kermnitz C, Tortora GJ. Anatomy and physiology: From science to life, 2nd edn. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

Katzung BG. Basic and clinical pharmacology, 10th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2006.

Keith SW, Redden DT, Katzmarzyk PT. Putative contributors to the secular increase in obesity. Int J Obes. 2006;30:1585–1594.

Landzberg B. Celiac disease: Could you be missing this diagnosis? Consultant. 2006;46:1458–1465.

Lawson EE, et al. Clinical estimation of liver span in infants and children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1978;132:474–476.

Longstreth G. Functional dyspepsia—managing the conundrum. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:791–793.

Malagelada J. A symptom-based approach to making a positive diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:57–63.

Marieb EN, Hoehn K. Human anatomy & physiology, 8th edn. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings, 2010.

Miller S, Alpert P. Assessment and differential diagnosis of abdominal pain. Nurse Pract. 2006;31:39–47.

National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2009. Available at http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/your_health/healthy/alcohol/index.htm#sum.

Park J, Akhtar R, Dietrich D. Chronic hepatitis C: Latest diagnosis and treatment guidelines. Consultant. 2006;46:463–468.

Robbins SL, Kumar V, Cotran RS. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease, 8th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2010.