Chapter Thirteen Nose, mouth and throat

INTRODUCTION

The nose, mouth and throat are especially important when considering the nutritional status of the person and their respiratory function. To appreciate the impact of disease, trauma and/or alteration in function of any of these intricate structures you are advised to review the structure and function of the nose, throat and mouth and the relationships to each other.

NOSE

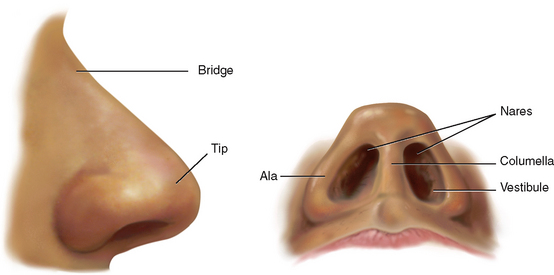

The nose is the first segment of the respiratory system. It warms, moistens and filters the inhaled air, and it is the sensory organ for smell. The external nose is shaped like a triangle with one side attached to the face (Fig 13.1). On its leading edge, the superior part is the bridge and the free corner is the tip. The oval openings at the base of the triangle are the nares; just inside, each naris widens into the vestibule. The columella divides the two nares and is continuous inside with the nasal septum. The ala is the lateral outside wing of the nose on either side. The upper third of the external nose is made up of bone; the rest is cartilage.

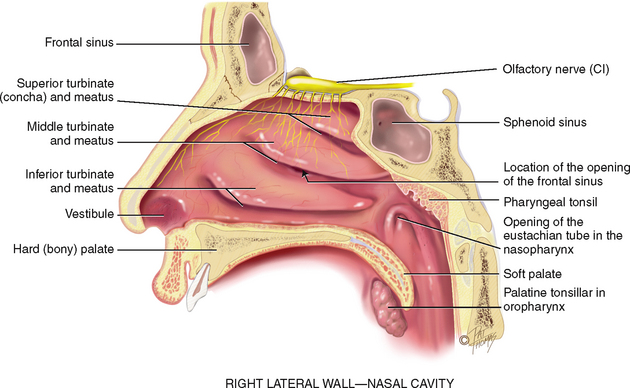

Inside, the nasal cavity is much larger than the external nose would indicate (Fig 13.2). It extends back over the roof of the mouth. The anterior edge of the cavity is lined with numerous coarse nasal hairs, or vibrissae. The rest of the cavity is lined with a blanket of ciliated mucous membrane. The nasal hairs filter the coarsest matter from inhaled air, whereas the mucous blanket filters out dust and bacteria. Nasal mucosa appears redder than oral mucosa because of the rich blood supply present to warm the inhaled air.

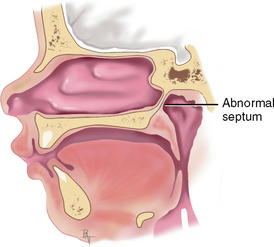

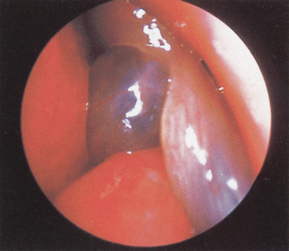

The nasal cavity is divided medially by the septum into two slit-like air passages. The anterior part of the septum holds a rich vascular network, Kiesselbach’s plexus, the most common site of nosebleeds. In many people, the nasal septum is not absolutely straight and may deviate towards one passage.

The lateral walls of each nasal cavity contain three parallel bony projections—the superior, middle and inferior turbinates. They increase the surface area so that more blood vessels and mucous membranes are available to warm, humidify and filter the inhaled air. Underlying each turbinate is a cleft, the meatus, which is named for the turbinate above. The sinuses drain into the middle meatus, and tears from the nasolacrimal duct drain into the inferior meatus.

The olfactory receptors (hair cells) lie at the roof of the nasal cavity and in the upper one-third of the septum. These receptors for smell merge into the olfactory nerve, cranial nerve I, which transmits to the temporal lobe of the brain. While smell is not considered necessary for human survival, it reduces the risks of poor nutritional intake by enhancing the smell and taste (flavour) of food (Duffy, 2007; Farmer, Raddin and Roberts, 2009).

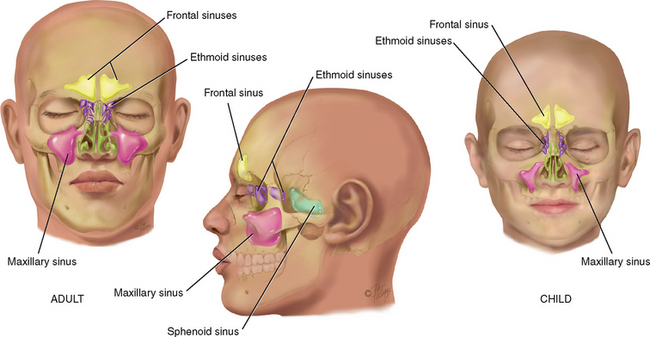

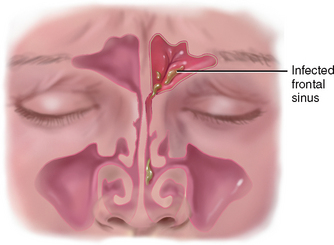

The paranasal sinuses are air-filled pockets within the cranium (Fig 13.3). They communicate with the nasal cavity and are lined with the same type of ciliated mucous membrane. They lighten the weight of the skull bones, serve as resonators for sound production and provide mucus, which drains into the nasal cavity. The sinus openings are narrow and easily occluded, which may cause inflammation or sinusitis.

Two pairs of sinuses are accessible to examination: the frontal sinuses in the frontal bone above and medial to the orbits and the maxillary sinuses in the maxilla (cheekbone) along the side walls of the nasal cavity. The other two sets are smaller and deeper: the ethmoid sinuses between the orbits and the sphenoid sinuses deep within the skull in the sphenoid bone. Sinuses support the humidification and warming of inspired air.

Only the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses are present at birth. The maxillary sinuses reach full size after all permanent teeth have erupted. The ethmoid sinuses grow rapidly between 6 and 8 years of age and after puberty. The frontal sinuses are absent at birth, are fairly well developed between 7 and 8 years of age and reach full size after puberty. The sphenoid sinuses are minute at birth and develop after puberty.

MOUTH

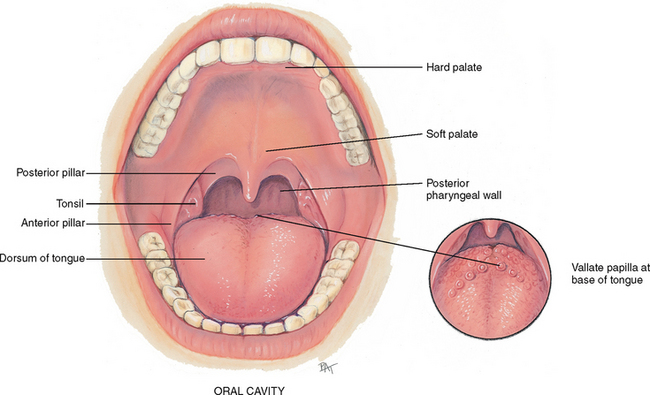

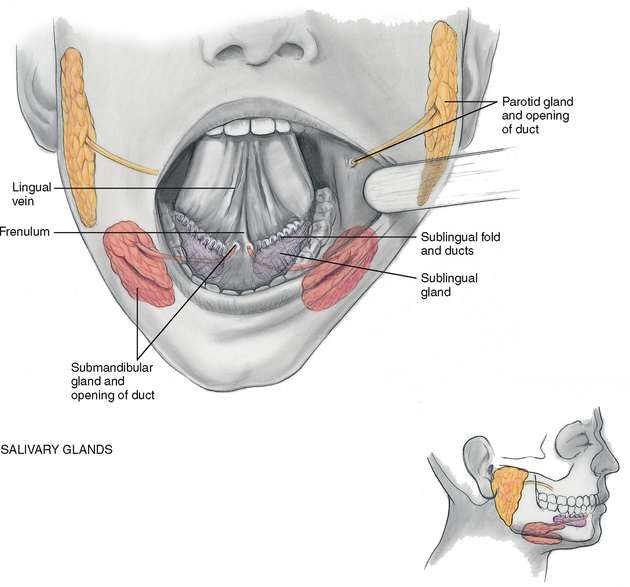

The mouth is the first segment of the digestive system and an airway for the respiratory system. The oral cavity is a short passage bordered by the lips, palate, cheeks and tongue. It contains the teeth and gums, tongue and salivary glands (Fig 13.4).

The lips are the anterior border of the oral cavity—the transition zone from the outer skin to the inner mucous membrane lining the oral cavity. The arching roof of the mouth is the palate; it is divided into two parts. The anterior hard palate is made up of bone and is a whitish colour. Posterior to this is the soft palate, an arch of muscle that is pinker in colour and mobile. The uvula is the free projection hanging down from the middle of the soft palate. The cheeks are the side walls of the oral cavity.

The floor of the mouth consists of the horseshoe-shaped mandible bone, the tongue and underlying muscles. The tongue is a mass of striated muscle arranged in a crosswise pattern so that it can change shape and position. The papillae are the rough, bumpy elevations on its dorsal surface. Note the larger vallate papillae in an inverted V shape across the posterior base of the tongue, and do not confuse them with abnormal growths. Underneath, the ventral surface of the tongue is smooth and shiny and has prominent veins. The frenulum is a midline fold of tissue that connects the tongue to the floor of the mouth.

The tongue’s ability to change shape and position enhances its functions in mastication, swallowing, cleansing the teeth and the formation of speech. The tongue also functions in taste sensation. Microscopic taste buds are in the papillae at the back and along the sides of the tongue and on the soft palate.

The mouth contains three pairs of salivary glands (Fig 13.5). The largest, the parotid gland, lies within the cheeks in front of the ear extending from the zygomatic arch down to the angle of the jaw. Its duct, Stensen’s duct, runs forwards to open on the buccal mucosa opposite the second molar. The submandibular gland is the size of a walnut. It lies beneath the mandible at the angle of the jaw. Wharton’s duct runs up and forwards to the floor of the mouth and opens at either side of the frenulum. The smallest gland, the almond-shaped sublingual gland, lies within the floor of the mouth under the tongue. It has many small openings along the sublingual fold under the tongue.

The glands secrete saliva, the clear fluid that moistens and lubricates the food bolus, starts digestion and cleans and protects the mucosa.

Adults have 32 permanent teeth—16 in each arch. Each tooth has three parts: the crown, the neck and the root. The gums (gingivae) collar the teeth. They are thick fibrous tissues covered with mucous membrane. The gums are different from the rest of the oral mucosa because of their pale pink colour and stippled surface.

THROAT

The throat, or pharynx, is the area behind the mouth and nose. The oropharynx is separated from the mouth by a fold of tissue on each side, the anterior tonsillar pillar. Behind the folds are the tonsils, each a mass of lymphoid tissue. The tonsils are the same colour as the surrounding mucous membrane, although they look more granular, and their surface shows deep crypts. Tonsillar tissue enlarges during childhood until puberty and then involutes. The posterior pharyngeal wall is seen behind these structures. Some small blood vessels may show on it.

The nasopharynx is continuous with the oropharynx, although it is above the oropharynx and behind the nasal cavity. The pharyngeal tonsils (adenoids) and the eustachian tube openings are located here (see Fig 13.2).

LYMPHATICS

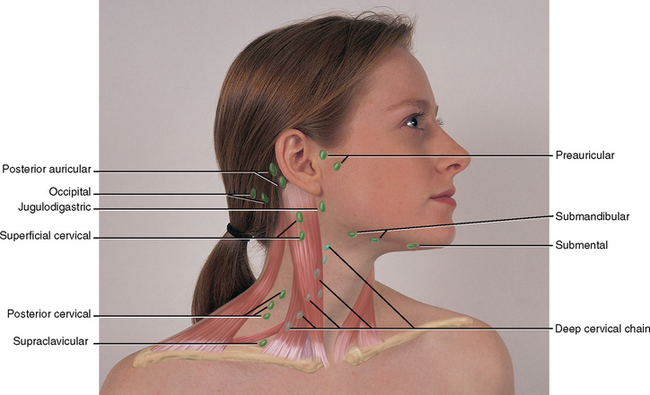

The oral cavity and throat have a rich lymphatic network (Fig 13.6). (For more discussion of the lymphatic system see Ch 11.) Although sources differ as to their nomenclature, one commonly used system is given here. Note that their labels correspond to adjacent structures.

• Preauricular, in front of the ear

• Posterior auricular (mastoid), superficial to the mastoid process

• Occipital, at the base of the skull

• Submental, midline, behind the tip of the mandible

• Submandibular, halfway between the angle and the tip of the mandible

• Jugulodigastric, under the angle of the mandible

• Superficial cervical, overlying the sternomastoid muscle

• Deep cervical, deep under the sternomastoid muscle

• Posterior cervical, in the posterior triangle along the edge of the trapezius muscle

• Supraclavicular, just above and behind the clavicle, at the sternomastoid muscle.

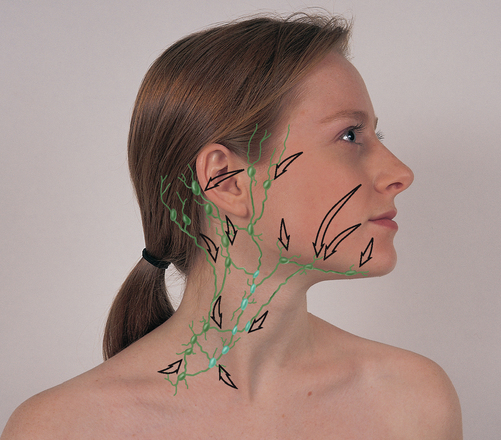

You also should be familiar with the direction of the drainage patterns of the lymph nodes (Fig 13.7). When nodes are abnormal, check the area they drain for the source of the problem. Explore the area proximal (upstream) to the location of the abnormal node.

The lymphatic system is an extensive vessel system, which is separate from the cardiovascular system and is phylogenetically older. The lymphatics are a major part of the immune system, whose job it is to detect and eliminate foreign substances from the body. The vessels allow the flow of clear, watery fluid (lymph) from the tissue spaces into the circulation. Lymph nodes are small, oval clusters of lymphatic tissue that are set at intervals along the lymph vessels like beads on a string. The nodes filter the lymph and engulf pathogens, preventing potentially harmful substances from entering the circulation. Nodes are located throughout the body but are accessible to examination only in four areas: head and neck, arms, axillae and inguinal region. The greatest supply is in the head and neck.

DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Infants and children

In the infant, salivation starts at 3 months. The baby will drool periodically for a few months before learning to swallow the saliva. This drooling does not herald the eruption of the first tooth, although many parents think it does.

The teeth, both sets, begin development in utero. Children have 20 deciduous, or temporary, teeth. These erupt between 6 months and 24 months of age. All 20 teeth should appear by 2½ years of age. The deciduous teeth are lost beginning at age 6 years through to age 12 years. They are replaced by the permanent teeth, starting with the central incisors (see Ch 16). The permanent teeth appear earlier in girls than in boys, and they erupt earlier in black children than in white children.

The nose develops during adolescence, along with other secondary sex characteristics. This growth starts at age 12 or 13 years, reaching full growth at age 16 years in females and age 18 years in males.

The pregnant female

Nasal stuffiness and epistaxis may occur during pregnancy as a result of increased vascularity in the upper respiratory tract. Also, the gums may be hyperaemic and softened and may bleed with normal toothbrushing. Contrary to superstitious folklore, no evidence exists that pregnancy causes tooth decay or loss.

Late adulthood (65+ years)

A gradual loss of subcutaneous fat starts during later middle adult years, making the nose appear more prominent in some people. The nasal hairs grow coarser and stiffer and may not filter the air as well. The hairs protrude and may cause itching and sneezing. Many older people clip these hairs, thinking them unsightly, but this practice may increase the risk of infection and airway irritation. Olfaction, or the sense of smell, may diminish for many reasons, including underlying neurodegenerative disorders. Decreased sensation may begin after age 35 or sensation may be retained intact throughout life (Mackay-Sim, Johnston, Owen et al, 2006).

In the oral cavity, the soft tissues atrophy and the epithelium thins, especially in the cheek and tongue. This results in loss of taste buds, with about an 80% reduction in taste functioning. Further impairments to taste include a decrease in salivary secretion that is needed to dissolve flavouring agents, and the presence of upper dentures that cover secondary taste sites (Kane et al, 2009).

Atrophic tissues ulcerate easily, which places the older person at risk for infections such as oral moniliasis. An increased risk of malignant oral lesions is also present.

Many dental changes occur with ageing. The tooth surface is abraded. The gums begin to recede and the teeth begin to erode at the gum line. A smooth V-shaped cavity forms around the neck of the tooth, exposing the nerve and making the tooth hypersensitive. Some tooth loss may occur from bone resorption (osteoporosis), which decreases the inner tooth structure and its outer support. Natural tooth loss is exacerbated by years of inadequate dental care, decay, poor oral hygiene and tobacco use.

If tooth loss occurs, the remaining teeth drift, causing malocclusion. The stress of chewing with maloccluding teeth causes further problems: (1) excessive bone resorption with further tooth loss occurs, (2) muscle imbalance results from a mandible and maxilla now out of alignment, which produces muscle spasms, tenderness of muscles of mastication, and chronic headaches, and (3) the temporomandibular joint is stressed, leading to osteoarthritis, pain and inability to fully open the mouth.

A diminished sense of taste and smell can decrease the ageing person’s interest in food and may contribute to malnutrition. Saliva production decreases; saliva acts as a solvent for food flavours and helps move food around the mouth. Decreased saliva also reduces the mouth’s self-cleaning property. The major cause of decreased saliva flow is not the ageing process itself but the use of medications that have anticholinergic effects. More than 250 medications have side effects that include development of a dry mouth.

Reduction in or absence of teeth and trouble with mastication encourages older people to eat soft foods (usually high in carbohydrates) and to decrease meat and fresh vegetable intake. This may increase the risk of nutritional deficit for protein, vitamins and minerals.

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

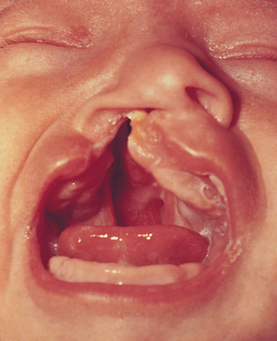

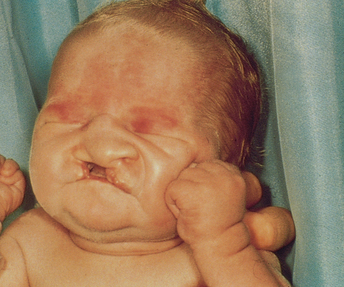

Orofacial clefts describe the incomplete closure of the hard or soft palate of the mouth with or without midline clefting of the upper or lower lip. Clefts are congenital abnormalities arising during development of the oral region. Cleft palate is relatively rare in the Australian population, indicated by rates of around 7.3 per 10 000 live births and even less common in the New Zealand population, at around 5.5 per 10 000 live births (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2008a). The incidence of cleft lip, with or without cleft palate, is somewhat higher in both regions at around 9 per 10 000 births (AIHW, 2008a). This rate is about 50% higher in Australian Indigenous infants (AIHW, 2009d).

Children tend to lose deciduous teeth at the rate of about 2–3 per year from the ages of 5 to 10. Australian and New Zealand children generally show good levels of dental health. Australian children particularly appear to have good access to dental care enhancing their good oral health, with 4 in 5 children visiting a dentist each 12 month period (AIHW, 2009a). In 2005, the majority of children and teenagers (approximately 80%) visited a dentist for a check-up and for preventative care treatments, rather than a dental or oral problem. Comparison of the number of decayed, missing or filled teeth in children across the 27 OECD countries indicated that Australian children ranked 7th, while children from New Zealand were at the OECD average, ranked 17th (AIHW, 2009a). The overall incidence of good oral health in children has increased due to factors such as provision of school dental care services, increased access to fluoridated toothpaste and drinking water and improved dental hygiene (AIHW, 2009a). However, the proportion of 6-year-old children who are free from dental decay in Australia declined between 1996 and 2002, to about 53% (AIHW, 2009c). The proportion of older children (12+ years of age) who remain decay free continues to grow, with older boys marginally more likely to develop decay than older girls (60% compared to 56%). However, good oral health varies across the population. Indigenous children, children in remote and very rural areas and those from the lowest socioeconomic groups show approximately twice the incidence of decayed, missing or filled teeth of their urbane counterparts (AIHW, 2009a).

Oral health of adults is also significantly impacted by location and age. Rural residents are twice as likely as city residents to be edentulous (9% compared to 5%) which can impact on diet and nutritional status (AIHW, 2009b). This percentage significantly increases with age; about 15% of Australian adults between 55 and 74 years are likely to have no natural teeth, while about 36% of adults over 75 have no remaining natural teeth (AIHW, 2008b). The health of teeth and gums is clearly related to access to dental care, with about 60% of city dwellers visiting the dentist regularly compared to 46% of non-city dwellers. Apparent lack of access to regular dental care, together with overall rates of dental decay, seems to impact on levels of untreated dental decay. About 20% of capital-city dwellers show previously untreated dental decay compared with about 30% in non-capital city dwellers (AIHW, 2009b).

Overall, however, oral health issues contribute only 0.9 disability-adjusted life years for Australian adults, even though about 600 Australians die each year from oral or oral-related cancers (AIHW, 2008c). Higher rates of lip and oral cancers are reported in Indigenous people, particularly Indigenous males; often presumed to be associated with higher levels of smoking (AIHW, 2008c).

SUBJECTIVE DATA

Disorders in the nose, mouth or throat cause pain, impaired function and in extreme situations could put the person at significant risk of airway obstruction or nutritional impairment. Subjective data collection should be done in conjunction with Chapters 14 and 16.

Mouth and throat

| Assessment guidelines | Clinical significance and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| Nose | |

| Rhinorrhoea occurs with colds, allergies, sinus infection, trauma. | |

| • Is the discharge watery, purulent, mucoid, bloody? | |

| Most people have occasional colds; thus, asking this more precise question yields more meaningful data. | |

| • Do you have chronic postnasal drip? | |

| Trauma may cause deviated septum, which may cause nares to be obstructed. | |

| • Can you breathe through your nose? Are both sides obstructed, or one? | |

| Epistaxis occurs with trauma, vigorous nose blowing, foreign body. | |

| • How much bleeding—a teaspoonful or does it pour out? | |

| • Colour of the blood—red or brown? Clots? | |

| • From one nostril or both? | |

| • Aggravated by nose-picking or scratching? | |

| • How do you treat the nosebleeds? Are they difficult to stop? | Person should sit up with head tilted forwards, pinch nose between thumb and forefinger for 5 to 15 minutes. |

| ‘Seasonal’ rhinitis if due to pollen; ‘perennial’ if allergen is dust. | |

| • How was this determined? | |

| • What type of environment makes it worse? Can you avoid exposure? | |

| • Use inhalers, nasal spray nose drops? How often? Which type? | Misuse of over-the-counter nasal medications irritates the mucosa, causing rebound swelling, a common problem. |

| • How long have you used this? | |

| Rationale: People are often poor at detecting changes in their smelling ability and often rely on reports from others. Sense of smell may deteriorate with chronic allergy, decreased nasal patency, prolonged cigarette smoking or the development of neurodegenerative condition such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s or motor neuron disease. | |

| Mouth and throat | |

| History helps determine whether oral lesions have infectious, traumatic, immunological or malignant aetiology. | |

| • How long have you had it? Ever had this lesion before? | |

| • Is it single or multiple? | |

| • Does it seem to be associated with stress, season change, food? | |

| • How have you treated the sore? Applied any local medication? | |

| • Is it associated with cough, fever, fatigue, decreased appetite, headache, postnasal drip or hoarseness? | |

| • Is it worse when arising? What is the humidity level in the room where you sleep? Any dust or smoke inhaled at work? | |

| • Usually get a throat culture for the sore throats? Were any documented as streptococcal? | Untreated strep throat may lead to the complication of rheumatic fever. |

| • How have you treated this sore throat: medication, gargling? How effective are these? Have your tonsils or adenoids been taken out? | |

| A disorder of the larynx with many causes, such as overuse of the voice, upper respiratory infection, chronic inflammation, lesions or a neoplasm. | |

| • Feel like having to clear your throat? Or, like a ‘lump in your throat’? | |

| • Use your voice a lot at work, recreation? | |

| • Does the hoarseness seem associated with a cold, sore throat? | |

| Tenderness suggests acute infection. | |

| • For a lump that persists, how long have you had it? Has it changed in size? | A persistent lump arouses suspicion of malignancy. For those more than 40 years old, suspect malignancy until proven otherwise. |

| • Any difficulty swallowing? | Dysphagia (see Ch 16). |

| Chronic tobacco use is associated with lung disease. | |

| • Any sores or irritation on the palate or gums? | Lesions may arise from ill-fitting dentures, or the presence of dentures may mask the eruption of new lesion. |

| • Any problems with talking—Do the dentures whistle or drop? Can you chew all foods with them? How do you clean them? | |

| Additional history for infants and children | |

OBJECTIVE DATA

The purpose of the examination of nose, mouth and/or throat is to assess patterns of pain, or any other abnormalities, and the impact these have on the person’s nutritional state and/or respiratory function. Objective examination should be done in conjunction with Chapters 14 and 16.

| Preparation | Equipment needed |

|---|---|

| Position the person sitting up straight with their head at your eye level. If the person wears dentures, offer a paper towel and ask the person to remove them. | Penlight |

| Two tongue blades |

| Procedures and normal findings | Abnormal findings and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| INSPECT AND PALPATE THE NOSE | |

| External nose | |

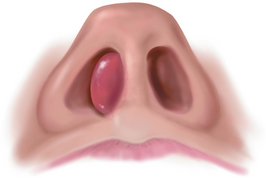

| Normally, the nose is symmetrical, in the midline and in proportion to other facial features (Fig 13.8). Inspect for any deformity, asymmetry, inflammation or skin lesions. If an injury is reported or suspected, palpate gently for any pain or break in contour. | |

| Test the patency of the nostrils by pushing each nasal wing shut with your finger while asking the person to sniff inwards through the other naris. This reveals any obstruction, which later is explored using the nasal speculum. The sense of smell, mediated by cranial nerve I, is usually not tested in a routine examination. The procedure for assessing smell is presented with cranial nerve testing in Chapter 22. | Absence of sniff indicates obstruction (e.g. common cold, nasal polyps, rhinitis). |

| PALPATE THE SINUS AREAS | |

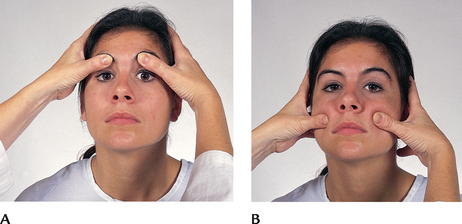

| Using your thumbs, press over the frontal sinuses below the eyebrows (Fig 13.9, A) and over the maxillary sinuses below the cheekbones (Fig 13.10, B). Take care not to press directly on the eyeballs. The person should feel firm pressure but no pain. | Sinus areas are tender to palpation in persons with chronic allergies and acute infection (sinusitis). |

| PALPATE THE TRACHEA | |

| Normally, the trachea is midline; palpate for any tracheal shift. Place your index finger on the trachea in the sternal notch, and slip it off to each side (Fig 13.10). The space should be symmetrical on both sides. Note any deviation from the midline. | • The trachea is pushed to the unaffected (or healthy) side with an aortic aneurysm, a tumour, unilateral thyroid lobe enlargement and pneumothorax. • The trachea is pulled towards the affected (diseased) side with large atelectasis, pleural adhesions or fibrosis. • Tracheal tug is a rhythmic downwards pull that is synchronous with systole and that occurs with aortic arch aneurysm. |

| INSPECT THE MOUTH | |

| Begin with anterior structures and move posteriorly. Use a tongue blade to retract structures and a bright light for optimal visualisation. | |

| Lips | |

| Inspect the lips for colour, moisture, cracking or lesions. Retract the lips and note their inner surface as well (Fig 13.11). | In light-skinned people: circumoral pallor occurs with shock and anaemia; cyanosis with hypoxaemia and chilling; cherry red lips with carbon monoxide poisoning, Herpes simplex, other lesions (see Table 13.2). |

| Tongue | |

Check the tongue for colour, surface characteristics and moisture. The colour is pink and even. The dorsal surface is normally roughened from the papillae. A thin white coating may be present. Ask the person to touch the tongue to the roof of the mouth. Its ventral surface looks smooth, glistening and shows veins. Saliva is present. If the person is able to move their own tongue, ask them to move it so you can visualise the ventral and lateral surfaces. Inspect for any white patches or lesions—normally none are present. If any occur, palpate these lesions for induration. |

Beefy red swollen tongue. Smooth glossy areas (see Table 13.5). Enlarged tongue occurs with mental retardation, hypothyroidism, acromegaly. |

| Palate | |

| Observe the uvula; it normally looks like a fleshy pendant hanging in the midline (Fig 13.12). Ask the person to say ‘ahhh’ and note the soft palate and uvula rise in the midline. This tests one function of cranial nerve X, the vagus nerve. | A bifid uvula looks like it is split in two (see Table 13.6). Any deviation to the side or absent movement indicates nerve damage, which might occur following a stroke or head injury. Clinical alert: this finding may indicate a raised risk of potential airway compromise and aspiration. Further assessment of swallow and airway patency is required. |

| INSPECT THE THROAT | |

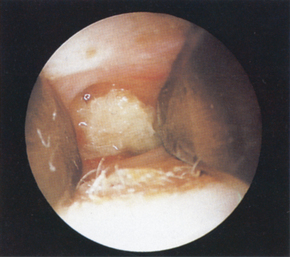

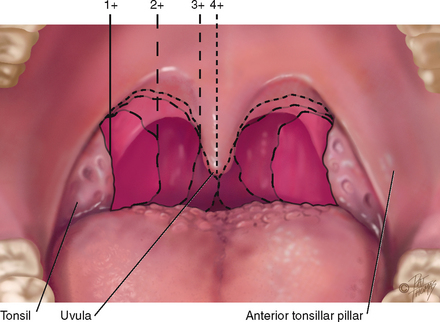

With your light, observe the oval, rough-surfaced tonsils behind the anterior tonsillar pillar (see Fig 13.12). Their colour is the same pink as the oral mucosa, and their surface is peppered with indentations or crypts. In some people the crypts collect small plugs of whitish cellular debris. This does not indicate infection. However, there should be no exudate on the tonsils. Tonsils are graded in size as follows: 2+ Halfway between tonsillar pillars and uvula You may normally see 1+ or 2+ tonsils in healthy people, especially in children, because lymphoid tissue is proportionately enlarged until puberty. |

|

| Enlarge your view of the posterior pharyngeal wall by depressing the tongue with a tongue blade (Fig 13.13). Push down halfway back on the tongue. Press slightly off centre to avoid eliciting the gag reflex. You can help the person whose gag reflex is easily triggered by offering a tongue blade to depress their own tongue. (Some people can lower their own tongue so the tongue blade is not needed.) Scan the posterior wall for colour, exudate or lesions. When finished, discard the tongue blade. | |

| During the examination, notice any breath odour. This is common and usually is due to a local cause, such as poor oral hygiene, heavy smoking. Occasionally it may indicate a systemic disease. | A foul, fetid odour may be noticed as occurs in dental or respiratory infections. |

| DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS | |

| Infants and children | |

| Because the oral examination is intrusive for the infant or young child, the timing is best towards the end of the complete examination, along with the ear examination. But if any crying episodes occur earlier, seize the opportunity to examine the open mouth and oropharynx. | |

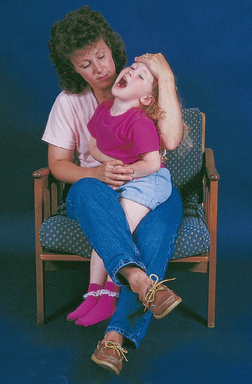

| As with the ear examination, let the parent help position the child. Place the infant supine on the examining table, with the arms restrained (Fig 13.14). The older infant and toddler may be held on the parent’s lap with one of the parent’s hands holding the arms down and the other hand securing the child’s head against the parent’s chest. Although not often needed, the parent’s leg can reach over and capture the child’s legs between the parent’s own (Fig 13.15). | |

| Use a game to help prepare the young child. Encourage the preschool child to use a tongue blade to look into a puppet’s mouth. Or place a mirror so that the child can look into the mouth while you do. The school-age child is usually cooperative and loves to show off missing or new teeth (Fig 13.16). | |

Be discriminating in your use of the tongue blade. It may be necessary for a full view of oral structures, but it produces a strong gag reflex in the infant. You may avoid the tongue blade completely with a cooperative preschooler and school-age child. Try asking the young child to open the mouth ‘as big as a lion’ and to move the tongue in different directions. To enlarge your view of the oropharynx, ask the child to stick out the tongue and ‘pant like a dog’. At some point, you will encounter an uncooperative young child who clenches the teeth and refuses to open the mouth. If all your other efforts have failed, slide the tongue blade along the buccal mucosa and turn it between the back teeth. Push down to depress the tongue. This stimulates the gag reflex, and the child opens the mouth wide for a few seconds. You will have a brief look at the throat. Make the most of it. |

|

| Nose. The newborn may have milia across the nose. There should be no nasal flaring or narrowing with breathing. | Nasal flaring in the infant indicates respiratory distress. |

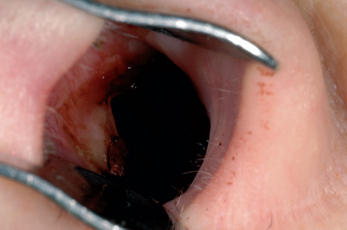

It is essential to determine the patency of the nares in the immediate newborn period because most newborns are obligate nose breathers. Nares blocked with amniotic fluid are suctioned gently with a bulb syringe. Avoid the nasal speculum when examining the infant and young child. Instead, gently push up the tip of the nose with your thumb while using your other hand to shine the light into the naris. With a toddler, be alert for the possible foreign body lodged in the nasal cavity (see Table 13.1). Only in children older than 8 years do you need to palpate the child’s sinus areas. In younger children, sinus areas are too small for palpation. |

A transverse ridge across the nose occurs in a child with chronic allergy from wiping the nose upwards with palm (see Table 13.3). Nasal narrowing on inhalation is seen with chronic nasal obstruction and mouth breathing. Inability to pass catheter through nasal cavity indicates choanal atresia, which needs immediate intervention (see Table 13.1). |

| On the palate, Epstein pearls are a normal finding in newborns and infants (Fig 13.17). They are small, whitish, glistening, pearly papules along the median raphe of the hard palate and on the gums, where they look like teeth. They are small retention cysts and disappear in the first few weeks. | A high-arched palate is usually normal in the newborn, but a very narrow or high arch also occurs with Turner’s syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan’s syndrome and Treacher Collins syndrome, or develops in the mouth-breather in chronic allergies. |

The tonsils are not visible in the newborn. They gradually enlarge during childhood, remaining proportionately larger until puberty. Tonsils appear still larger if the infant is crying or gagging. Normally the newborn can produce a strong, lusty cry. Insert your gloved finger into the baby’s mouth and palpate the hard and soft palate as the baby sucks. The sucking reflex can be elicited in infants up to 12 months old. |

|

| FURTHER OBJECTIVE ASSESSMENT FOR ADVANCED PRACTICE | |

| The assessments that are described in the following sections require advanced skill and scope of practice. Nurses working in specialist units and some community nurses need to develop these skills. | |

| Inspect and palpate the nose | |

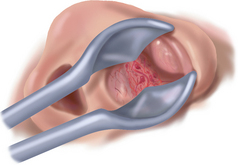

| Nasal cavity | |

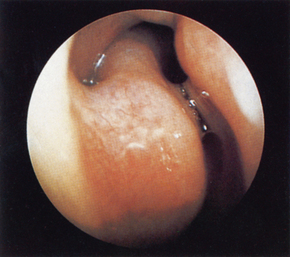

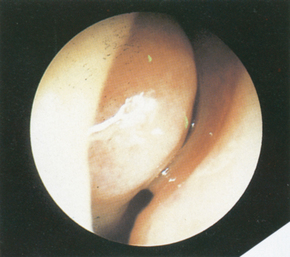

| Inspect the turbinates, the bony ridges curving down from the lateral walls. The superior turbinate will not be in your view, but the middle and inferior turbinates appear the same light red colour as the nasal mucosa. Note any swelling but do not try to push the speculum past it. Turbinates are quite vascular and tender if touched. | Turbinates swell marginally in a cyclical manner, thus apparent abnormalities, particularly asymmetries, need to be repeatedly assessed over time. |

| Note any polyps, benign growths that accompany chronic allergy, and distinguish them from the normal turbinates. | Polyps are smooth, pale grey, avascular, mobile, nontender (see Table 13.1). |

| The sinus areas | |

| Transillumination | |

| You may use this technique when you suspect sinus inflammation, although it is of limited usefulness. Darken the examining room. Affix a strong narrow light to the end of the otoscope and hold it deep under the superior orbital ridge against the location of the frontal sinus area (Fig 13.18). Cover with your hand. A diffuse red glow is a normal response. It comes from the light shining through the air in the healthy sinus. | An inflamed sinus filled with fluid does not transilluminate. |

| You may use the same technique with the maxillary sinuses, providing the person has no upper denture that would impede the light. Ask the person to tilt the head back and open the mouth. Shine the light on each cheek just under the inner corner of the eye. Note a dull glow inside the mouth on the hard palate as the light transmits through the sinuses. Healthy sinuses contain air and may light up symmetrically. But be aware that asymmetry is not a reliable sign of sinus inflammation because many healthy sinuses normally will not transilluminate. | A significant finding is one sinus illuminated and the other clouded. If one has fluid, it looks darker than the healthy one. |

| Palpate the lymph nodes in the neck area | |

| Using a gentle circular motion of your fingerpads, palpate the lymph nodes (Fig 13.19). (Normally, the salivary glands are not palpable. When symptoms warrant, check for parotid tenderness by palpating in a line from the outer corner of the eye to the lobule of the ear.) Beginning with the preauricular lymph nodes in front of the ear, palpate the 10 groups of lymph nodes in a routine order. Many nodes are closely packed, so you must be systematic and thorough in your examination. Once you establish your sequence, do not vary or you may miss | The parotid is swollen with mumps (see Table 13.7). |

| Use gentle pressure because strong pressure could push the nodes into the neck muscles. It is usually most efficient to palpate with both hands, comparing the two sides symmetrically. However, the submental gland under the tip of the chin is easier to explore with one hand. When you palpate with one hand, use your other hand to position the person’s head. For the deep cervical chain, tip the person’s head towards the side being examined to relax the ipsilateral muscle (Fig 13.20). Then you can press your fingers under the muscle. Search for the supraclavicular node by having the person hunch the shoulders and elbows forwards (Fig 13.21); this relaxes the skin. The inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle crosses the posterior triangle here; do not mistake it for a lymph node. | |

| If nodes are enlarged or tender, check the area they drain for the source of the problem. For example, those in the upper cervical or submandibular area often relate to inflammation or a neoplasm in the head and neck. Follow up on or refer your findings. An enlarged lymph node, particularly when you cannot find the source of the problem, deserves prompt attention. | The following criteria are common clues but are not definitive in all circumstances. • Acute infection—nodes are bilateral, enlarged, warm, tender and firm but freely movable. • Chronic inflammation (e.g. in tuberculosis the nodes are clumped). • Cancerous nodes are hard, unilateral, nontender and fixed. • Nodes with HIV infection are enlarged, firm, nontender and mobile. Occipital node enlargement is common with HIV infection. • A single, enlarged, nontender, hard, left supraclavicular node (Virchow’s node) may indicate neoplasm in thorax or abdomen. • Painless, rubbery, discrete nodes that gradually appear occur with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. |

TABLE 13.1 Abnormalities of the nose

TABLE 13.2 Abnormalities of the lips

|

| Cleft lip |

| Orofacial clefts are the most common congenital deformities of the head and neck. The incidence of orofacial clefts in infants born in Australia is 17 per 10 000. The incidence is 50% higher among Indigenous infants (AIHW, 2009d). Early treatment preserves the functions of speech and language formation and deglutition (swallowing). |

|

| Herpes simplex 1 |

| The cold sores are groups of clear vesicles with a surrounding indurated erythematous base. These evolve into pustules, which rupture, weep and crust, and heal in 4 to 10 days. The most likely site is the lip–skin junction; infection often recurs in same site. Caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV-1), the lesion is highly contagious and is spread by direct contact. Recurrent herpes infections may be precipitated by sunlight, fever, colds, allergy. It is a very common lesion, affecting 50% of adults. |

|

| Angular cheilitis (stomatitis, perlèche) |

| Erythema, scaling, shallow and painful fissures at the corners of the mouth occur with excess salivation and Candida infection. It is often seen in edentulous persons and in those with poorly fitting dentures causing folding in of corners of mouth, creating a warm and moist environment favouring growth of yeast. |

|

| Carcinoma |

|

| Retention ‘cyst’ (mucocele) |

| A round, well-defined translucent nodule that may be very small or up to 1 or 2 cm. It is a pocket of mucus that forms when a duct of a minor salivary gland ruptures. The benign lesion also may occur on the buccal mucosa, on the floor of the mouth or under the tip of the tongue. |

TABLE 13.3 Abnormalities of the teeth and gums

|

| Baby bottle tooth decay |

| Destruction of numerous deciduous teeth may occur in older infants and toddlers who take a bottle of milk, juice or sweetened drink to bed and prolong bottle feeding past the age of 1 year. Liquid pools around the upper front teeth. Mouth bacteria act on carbohydrates in the liquid, especially sucrose, forming metabolic acids. Acids break down tooth enamel and destroy its protein. |

|

| Malocclusion |

| Upper or lower dental arches are not in alignment and incisors protrude from developmental problem of mandible or maxilla, or incompatibility between jaw size and tooth size. The condition increases risk of facial deformity, negative body image, chewing problems or speech dysfluency. |

|

| Dental caries |

| Progressive destruction of tooth. Decay initially looks chalky white. Later, it turns brown or black and forms a cavity. Early decay is apparent only on x-ray study. Susceptible sites are tooth surfaces where food debris, bacterial plaque and saliva collect. |

|

| Epulis |

| A nontender, fibrous nodule of the gum, seen emerging between the teeth; an inflammatory response to injury or haemorrhage. |

|

| Gingival hyperplasia |

| Painless enlargement of the gums, sometimes overreaching the teeth. This occurs with puberty, pregnancy, leukaemia and with long-term therapeutic use of phenytoin (Dilantin). |

|

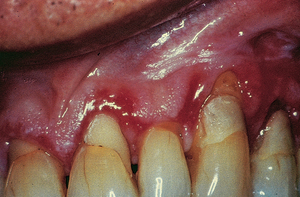

| Gingivitis |

| Gum margins are red, swollen and bleed easily. This case is severe; gingival tissue has desquamated, exposing roots of teeth. Inflammation is usually due to poor dental hygiene or vitamin C deficiency. The condition may occur in pregnancy and puberty because of changing hormonal balance. |

|

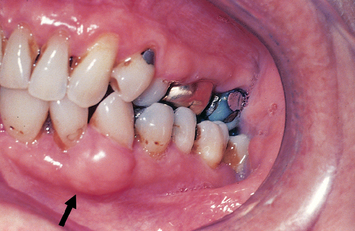

| Meth mouth |

| Illicit methamphetamine abuse (crystal meth, meth ice) leads to extensive dental caries, gingivitis, tooth cracking and edentulism. Methamphetamine causes vasoconstriction and decreased saliva, and its use increases the urge to consume sugars and starches and to give up oral hygiene. Absence of the buffering saliva leads to increased acidity in the mouth, and the increased plaque encourages bacterial growth. These conditions and the presence of carbohydrates set up an oral environment prone to caries, cracking of enamel and the damage seen here. |

From Neville BW et al: Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, 3rd edn. St Louis, 2009, Saunders.

TABLE 13.5 Abnormalities of the tongue

|

| Ankyloglossia |

| (Tongue-tie.) A short lingual frenulum, here fixing the tongue tip to the floor of the mouth and gums. This limits mobility and will affect speech (pronunciation of a, d, n) if the tongue tip cannot be elevated to the alveolar ridge. A congenital defect. |

|

| Fissured or scrotal tongue |

| Deep furrows divide the papillae into small irregular rows. The condition occurs in 5% of the general population and in Down syndrome. The incidence increases with age. (Vertical, or longitudinal, fissures also occur with dehydration because of reduced volume of the tongue.) |

|

| Geographic tongue (migratory glossitis) |

| Pattern of normal coating interspersed with bright red, shiny, circular bald areas with raised pearly borders. Pattern resembles a map, and changes in a few days. Not significant, and its cause is not known. |

|

| Smooth, glossy tongue (atrophic glossitis) |

| The surface is slick and shiny; the mucosa thins and looks red from decreased papillae. Accompanied by dryness of tongue and burning. Occurs with vitamin B12 deficiency (pernicious anaemia), folic acid deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia. Here, also note angular cheilitis. |

|

| Black hairy tongue |

| This is not really hair but the elongation of filiform papillae and painless overgrowth of mycelial threads of fungus infection on the tongue. Colour varies from black-brown to yellow. It occurs after use of antibiotics, which inhibit normal bacteria and allow proliferation of fungus. |

|

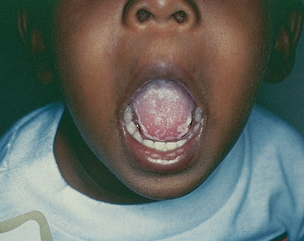

| Enlarged tongue (macroglossia) |

| The tongue is enlarged and may protrude from mouth. The condition is not painful but may impair speech development. Here, it occurs with Down syndrome; it also occurs with cretinism, myxoedema, acromegaly. Also a transient swelling occurs with local infections. |

|

| Carcinoma |

| An ulcer with rolled edges; indurated. Occurs particularly at sides, base and under the tongue. When it is in the floor of mouth, it may cause painful movement or limited movement of tongue. Risk of early metastasis is present because of rich lymphatic drainage. Heavy smoking and heavy alcohol use place persons at greater risk. |

TABLE 13.6 Abnormalities of the oropharynx

TABLE 13.7 Swelling on the neck

|

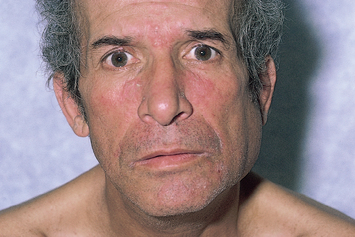

| Parotid gland enlargement |

| Rapid painful inflammation of the parotid occurs with mumps. Parotid swelling also occurs with blockage of a duct, abscess or tumour. Note swelling anterior to lower ear lobe. Stensen duct obstruction can occur in ageing adults dehydrated from diuretics or anticholinergics. |

Promoting a healthy lifestyle

Our amazing smelling ability: purpose and prediction

The sense of smell in humans is an important ‘safety’ sensory system, even though it may not be as well developed at detecting airborne chemicals as that in other mammals. People use their sense of smell every day in a number of ways. For example, smell enables people to help determine the safety of food before they eat it; ensuring detection of spoiled food which could induce gastric upset, nausea and vomiting. It also is an important contributor to food flavour which is thought to increase calorific intake and thus to help maintain good nutritional status, particularly in older people. Smell can alert people to the presence of dangerous chemicals such as solvents like petrol or gas and also about fire and smoke. Smell can alert people who are predisposed to skin and soft tissue ulceration and other peripheral wound formation, such as long-term diabetic patients, to the presence of poorly cared for or mismanaged wounds. Detecting and identifying smells is an essential part of many people’s professional duties, including that of clinical nurses, alerting nurses to the presence of infection, gangrene and other disease states such as diabetic ketoacidosis. Finally, a functioning sense of smell can support and assist patients in maintaining social connections, by helping to ensure basic personal hygiene.

Tests of smell

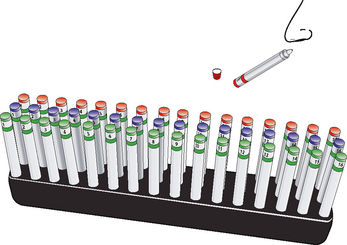

With the re/introduction of school nurses and the increasing importance of nurses in clinics and GP practices to conduct basic health screening, it is increasingly important for nurses to be aware of the various tests of sensory function, including smell. There are a number of specialist tests used to assess smell in adults. These are currently rarely used in standard clinical practice, but can accurately detect smelling ability and loss of smelling ability. The Pennsylvania Scratch’n’Sniff test is a test in which small cards are impregnated with odours that are released when the surface is scratched. When a person has scratched the card and smelt the odour, they are asked to identify the odour from 1 of 4 possible options written on the page, in a multiple choice test. This test is easy to administer and has been shown to be an excellent test of odour identification in the clinic.

Other tests of smelling ability are more detailed and time-consuming. For example, the ‘Sniffin’ Sticks’ test (Fig 13.22) requires people to sniff the barrel of a felt-tipped pen which contains different amounts (concentrations) of one of many different specific odorants. These tests enable assessment of various aspects of our ability to smell including odour identification, odour discrimination (identifying the differences between smells) and odour detection threshold (Mackay-Sim, Johnston, Owen et al, 2006). These tests come with ‘picture’ (visual) selection options for people with verbal dysfunction or reduced cognitive abilities.

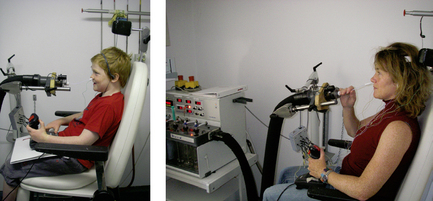

The most objective test of smell requires an olfactometer, a machine which delivers warmed and humidified air together with specific concentrations of odour directly to a person’s nose. Simultaneous EEG recordings enable clinicians to record brain activity associated with smell detection (Fig 13.23).

Why test for smell?

Smell is also a unique system because olfactory nerves (neurons), unlike those in any other human sensory system, continue to regenerate throughout life. This means that the sense of smell in otherwise healthy people can be retained throughout life (Mackay-Sim, Johnston, Owen et al, 2006). When smelling ability is reduced or lost it may be associated with the development of other neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, motor neurone disease and even schizophrenia (Hawkes, 2006). Decrement or loss of smell often occurs prior to other linical symptoms of such degenerative conditions, alerting clinicians to the need for medication or other clinical intervention. Thus, increasingly, loss of smell is being used as part of the screening tools applied to older people to detect neurological damage (Welge-Lüssen, 2009). With increasingly aged populations the need to screen effectively for neurodegeneration, often via relatively simple, nursing-applied tests, is also growing.

Exciting future possibilities

The presence of ‘stem cells’ ready to make new neurons in the human adult brain offers hope of transplantation therapies to reduce the impact and severity of many neurological dysfunctions in the future. Australian scientists are already harvesting stem cells from the olfactory mucosa of people to grow new nerve cells. It has been shown that non-neural cells such as heart, liver and kidney can also be grown from stem cells collected from the olfactory mucosa (Murrell, Feron, Wetzig et al, 2005). Research exploring the possibilities of assisting people with neurological conditions as diverse as spinal cord damage or the cell loss associated with Parkinson’s disease, using stem cells collected from the injured person, is underway in Australia and other countries. Such ‘autologous’ (collected from a person and transplanted back into the same person) transplantation therapies offer hope of some functional recovery without many of the complex ethical and technical difficulties associated with other transplantation and stem cell therapies.

DOCUMENTATION AND CRITICAL THINKING

FOCUSED ASSESSMENT: CLINICAL CASE STUDY 1

A 26-year-old male is brought in by ambulance to the emergency department after being the victim of a physical assault. On examination he is conscious with blackening of the left eye and swelling and bruising over the left zygoma.

Subjective

On presentation he appears orientated and reports no amnesia or loss of consciousness (LOC).

The patient reports decreased sensation of the cheek, nose and upper lip on the affected side, as well as double vision. He also reports anosmia and difficulty breathing through his nose but states this is a long-term problem and not related to the assault.

Objective

Vital signs: all within normal range

Cheek/face: Periorbital and mid-face swelling

Eyes: (L) subconjunctival haemorrhage and restriction of eye movement with upward gaze

Nose: Only (L) naris patent. Mucosa grey and boggy bilaterally. (R) naris has a mobile, grey, nontender mass, obstructing view of the turbinates and rest of the nasal cavity.

Mouth and throat: Mucosa pink, no lesions or abrasions. Teeth intact. Uvula midline, rises on phonation. Tonsils absent. No lumps or lesions on palpation.

Cognitive state: Alert, orientated, PEARL (Pupils equal and reacting to light), GCS (Glasgow coma scale) 15/15

FOCUSED ASSESSMENT: CLINICAL CASE STUDY 2

Esther V is a 61-year-old woman who has been admitted to the hospital for chemotherapy for carcinoma of the breast. This is her 5th day in the hospital. An oral assessment is performed when she complains of ‘soreness and a white coating’ in the mouth.

Subjective

Felt soreness on tongue and cheeks during night. Now pain persists, and EV can see a ‘white coating’ on tongue and cheeks: ‘I’m worried. Is this more cancer?’

Objective

EV generally appears restless and overly aware.

Oral mucosa pink. Large white, cheesy patches covering most of dorsal surface of tongue and buccal mucosa. Will scrape off with tongue blade, revealing red eroded area beneath.

Bleeds with slight contact. Posterior pharyngeal wall pink, no lesions. Patches are soft to palpation. No palpable lymph nodes.

ABNORMAL FINDINGS

TABLE 13.4 Abnormalities of the buccal mucosa

|

| Aphthous ulcers |

| A ‘canker sore’ is a vesicle at first, then a small, round, ‘punched-out’ ulcer with white base surrounded by a red halo. It is quite painful and lasts for 1 to 2 weeks. The cause is unknown, although it is associated with stress, fatigue and food allergy. It is common, affecting 20% to 60% of the population. |

|

| Koplik’s spots |

| Small blue-white spots with irregular red halo scattered over mucosa opposite the molars. An early sign, and pathognomonic, of measles. |

|

| Leucoplakia |

| Chalky white, thick, raised patch with well-defined borders. The lesion is firmly attached and does not scrape off. It may occur on the lateral edges of tongue. It is due to chronic irritation, and occurs more frequently with heavy smoking and heavy alcohol use. Lesions are precancerous, and the person should be referred. (Here, the lesion is associated with squamous carcinoma.) |

|

| Candidiasis or monilial infection |

| A white, cheesy, curd-like patch on the buccal mucosa and tongue. It scrapes off, leaving raw, red surface that bleeds easily. Termed ‘thrush’ in the newborn. It is an opportunistic infection that occurs after the use of antibiotics, corticosteroids and in immunosuppressed persons. |

Adams C. Poststroke complications and risk factors: Implications for primary care nurse practitioners. J Nurse Pract. 2006;2:533–539. 546

Andreae M. How to recognize and manage herpes simplex virus type 1 infections. Contemp Pediatr. 2004;21:41–60.

Armengol C, Hendley O, Schlager T. An office-based guide to diagnosing streptococcal pharyngitis. Contemp Pediatr. 2006;23:64–70.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW): 2008a: Congenital abnormalities in Australia. PSU Doc No. 41, Canberra, 2008, AIHW.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW): 2008b: The national survey of Australia’s oral health. No. DEN 175, Canberra, 2008, AIHW.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW): 2008c: Rural, regional and remote health: indicators of health status and determinants of health. Rural Health Series No. 10 Cat. No. PHE 103, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW): Dental health of Australia’s teenagers and pre-teen children. DSRU No. 52, Canberra, 2009, AIHW.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW): 2009b Geographic variation in oral health and use of dental services in the Australian population 2004–06. Doc No. 41, Canberra, 2009, AIHW.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW): 2009c Oral health impacts among children by dental visiting and treatment needs. DSRU No. 44, Canberra, 2009, AIHW.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW): 2009d A picture of Australia’s children. No. PHE 112, Canberra, 2009, AIHW.

Bernstein J. Making the distinction between allergic rhinitis and nonallergic rhinitis. J Resp Dis. 2006;27:281.

Bluestone CD, et al. Pediatric otolaryngology, 4th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2002.

Burgess J. Painful oral lesions: What to look for, how to treat, part 1. Consultant. 2006;46:1497–1504.

Curtis EK. Meth mouth: A review of methamphetamine use and its oral manifestations. Gen Dent. 2006;54(2):125–129.

Duffy VB. Variation in oral sensation: implications for diet and health. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:171–177.

Eccles R. Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:718–725.

Farmer MN, Raddin RS, Roberts JD. The relationship between taste, olfaction, and nutrition in the cancer population. J Support Oncol. 2009;7:70–72.

Gleason M, et al. Childhood allergic rhinitis: Using clinical clues and optimizing management. Am J Nurse Pract. 2006;10:45–53.

Hawkes C. Olfaction in neurodegenerative disorder. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;63:133–151.

Huang S. Nasal allergy and sinus infection: the link and therapeutic implications. Consultant. 2006;46:1357–1365.

Kane RL, et al. Essentials of clinical geriatrics, 6th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009.

Mackay-Sim A, Johnston AN, Owen C, et al. Olfactory ability in the healthy population: reassessing presbyosmia. Chemical Senses. 2006;31:763–771.

Murrell W, Feron F, Wetzig A, et al. Multipotent stem cells from adult olfactory mucosa. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:496–515.

Morris H. Managing dysphagia in older people. Primary Health Care. 2006;16:34–36.

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2005 with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD: The Center. DHHS Publication No. 2005–1232, 2006.

Welge-Lüssen A. Ageing, neurodegeneration, and olfactory and gustatory loss. Acta oto-rhino-laryngologica belgica. 2009;8:129.

Westergren A. Detection of eating difficulties after stroke: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev. 2006;53:143–149.