Chapter Twenty-five Female sexual and reproductive function

INTRODUCTION

The female reproductive structures include the external genitalia and internal structures: the vagina, cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries. The pelvic floor muscles, ligaments and fascia form an important support structure for the internal organs of the lower pelvis. As the organs and muscles of the abdomen, urinary tract and bowel are also relevant to female sexual and reproductive function you should also revise these chapters (18, 19 and 20).

EXTERNAL GENITALIA

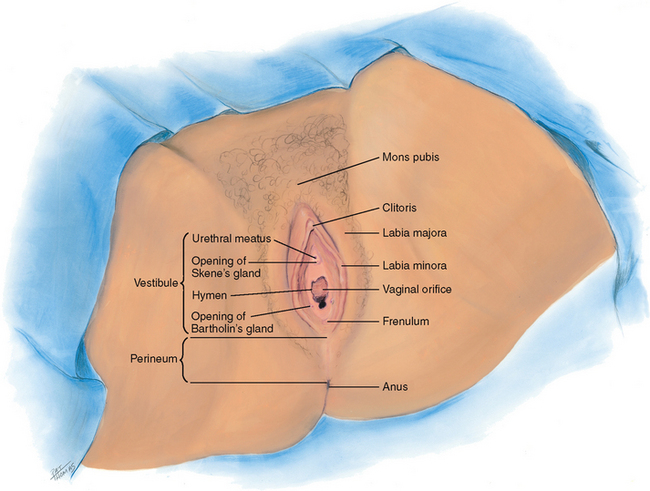

The external genitalia are called the vulva, or pudendum (Fig 25.1). The mons pubis is a round, firm pad of adipose tissue covering the symphysis pubis. After puberty, it is covered with hair in the pattern of an inverted triangle. The labia majora are two rounded folds of adipose tissue extending from the mons pubis down and around to the perineum. After puberty, hair covers the outer surfaces of the labia, whereas the inner folds are smooth and moist and contain sebaceous follicles.

Inside the labia majora are two smaller, darker folds of skin, the labia minora. These are joined anteriorly at the clitoris where they form a hood, or prepuce. The labia minora are joined posteriorly by a transverse fold, the frenulum or fourchette. The clitoris is a small, pea-shaped erectile body, homologous with the male penis and highly sensitive to tactile stimulation.

The labial structures encircle a boat-shaped space, or cleft, termed the vestibule. Within it are numerous openings. The urethral meatus appears as a dimple 2.5 cm posterior to the clitoris. Surrounding the urethral meatus are the tiny, multiple paraurethral (Skene’s) glands. Their ducts are not visible but open posterior to the urethra at the 5 and 7 o’clock positions.

The vaginal orifice is posterior to the urethral meatus. It appears either as a thin median slit or as a large opening with irregular edges, depending on the presentation of the membranous hymen. The hymen is a thin, circular or crescent-shaped fold that may cover part of the vaginal orifice or may be absent completely. On either side, and posterior to the vaginal orifice, are two vestibular (Bartholin’s) glands, which secrete a clear lubricating mucus during intercourse. Their ducts are not visible but open in the groove between the labia minora and the hymen.

PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLES AND PERINEUM

The bony pelvis forms the solid structure for the muscles and ligaments of the anterior, posterior and lateral pelvic walls and pelvic floor which play such an important role in supporting the position of the pelvic organs. The pelvic floor muscles include the coccygeus muscle and the levator ani and are referred to as the pelvic diaphragm, which stretches from the pubic bone anteriorly to the coccyx posteriorly and from the right and left lateral pelvic walls. The anal canal, urethra and vagina pass through the pelvic diaphragm. The levator ani muscles support the pelvic organs and functions as a sphincter for the anal canal and urethra (Jenkins, Kemnitz and Tortora, 2010).

The perineum is located inferior to the pelvic diaphragm. The perineum extends from the symphysis pubis anteriorly to the coccyx posteriorly and the ischial tuberosities laterally. The muscles of the perineum are in two layers, superficial and deep. The superficial layer includes the superficial transverse perineal, bulbospongiosus and the ischiocavernosus muscles which help to maintain erection of the clitoris. The deep layer of the perineum includes the deep transverse perineal muscle, the external urethral sphincter and external anal sphincter which assist in maintaining urinary and faecal continence (Jenkins, Kemnitz and Tortora, 2010).

INTERNAL GENITALIA

The internal genitalia include the vagina, a flattened, tubular canal extending from the orifice up and backwards into the pelvis (Fig 25.2). It is 9 cm long and sits between the rectum posteriorly and the bladder and urethra anteriorly. Its walls are in thick transverse folds, or rugae, enabling the vagina to dilate widely during childbirth.

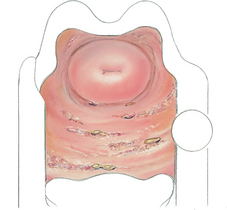

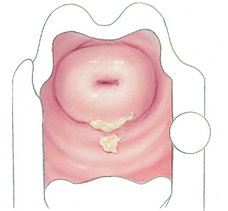

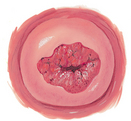

At the end of the canal, the uterine cervix projects into the vagina. In the nulliparous female, the cervix appears as a smooth doughnut-shaped area with a small circular hole, or os. After childbirth, the os is slightly enlarged and irregular. The cervical epithelium is of two distinct types. The vagina and cervix are covered with smooth, pink, stratified squamous epithelium. Inside the os, the endocervical canal is lined with columnar epithelium that looks red and rough. The point where these two tissues meet is the squamocolumnar junction and is not visible.

A continuous recess is present around the cervix, termed the anterior fornix in front and the posterior fornix at the back. Behind the posterior fornix, another deep recess is formed by the peritoneum. It dips down between the rectum and cervix to form the rectouterine pouch, or cul-de-sac of Douglas.

The uterus is a pear-shaped, thick-walled, muscular organ. It is flattened anteroposteriorly, measuring 5.5 to 8 cm long by 3.5 to 4 cm wide and 2 to 2.5 cm thick. It is freely movable, not fixed, and usually tilts forwards and superior to the bladder (a position labelled as anteverted and anteflexed, see Fig 25.19 below).

The fallopian tubes are two pliable, trumpet-shaped tubes, 10 cm in length, extending from the uterine fundus laterally to the brim of the pelvis. There they curve posteriorly, their fimbriated ends located near the ovaries. The two ovaries are located one on each side of the uterus at the level of the anterior superior iliac spine. Each is oval shaped, 3 cm long by 2 cm wide by 1 cm thick and serves to develop ova (eggs) and the female hormones.

DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Infants and adolescents

At birth, the external genitalia are engorged because of the presence of maternal oestrogen. The structures recede in a few weeks, remaining small until puberty. The ovaries are located in the abdomen during childhood. The uterus is small with a straight axis and no anteflexion.

At puberty, oestrogens stimulate the growth of cells in the reproductive tract and the development of secondary sex characteristics. The first signs of puberty are breast and pubic hair development, beginning between the ages of 8½ and 13 years. These signs are usually concurrent, but it is not abnormal if they do not develop together. They take about 3 years to complete.

Menarche occurs during the latter half of this sequence, just after the peak of growth velocity. Irregularity of the menstrual cycle is common during adolescence because of the girl’s occasional failure to ovulate. With menarche, the uterine body flexes on the cervix. The ovaries are now in the pelvic cavity.

Tanner’s table on the five stages of pubic hair development (sex maturity ratings (SMR)) is helpful in teaching girls the expected sequence of sexual development (see Table 25.1). These data may not necessarily generalise to all people as there are wide individual variations in development.

TABLE 25.1 Sex maturity ratings (SMR) in girls

| Stage 1 Preadolescent. No pubic hair. Mons and labia covered with fine vellus hair as on abdomen. | |

|

|

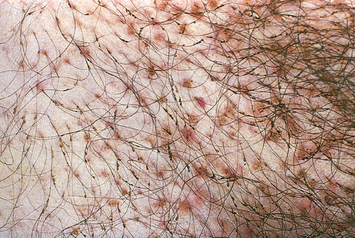

| Stage 2 Growth sparse and mostly on labia. Long, downy hair, slightly pigmented, straight or only slightly curly. | Stage 3 Growth sparse and spreading over mons pubis. Hair is darker, coarser, curlier. |

|

|

| Stage 4 Hair is adult in type but over smaller area; none on medial thigh. | Stage 5 Adult in type and pattern; inverse triangle. Also on medial thigh surface. |

Adapted from Tanner JM: Growth at adolescence, Oxford, 1962, Blackwell Scientific.

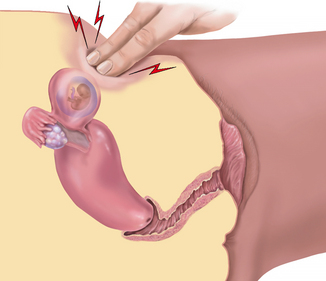

The pregnant female

A complete discussion of the pregnant female is presented in Chapter 28. In summary, shortly after the first missed menstrual period, the genitalia show signs of the growing fetus. The cervix softens (Goodell’s sign) at 4 to 6 weeks, and the vaginal mucosa and cervix look cyanotic (Chadwick’s sign) at 8 to 12 weeks. These changes occur because of increased vascularity and oedema of the cervix and hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the cervical glands. The isthmus of the uterus softens (Hegar’s sign) at 6 to 8 weeks.

The greatest change is in the uterus itself. It increases in capacity by 500 to 1000 times its nonpregnant state, at first because of hormone stimulation and then because of the increasing size of its contents (Marieb and Hoehn, 2010). The nonpregnant uterus has a flattened pear shape. Its early growth encroaches on the space occupied by the bladder, producing the symptom of urinary frequency. By 10 to 12 weeks’ gestation, the uterus becomes globular in shape and is too large to stay in the pelvis. At 20 to 24 weeks, the uterus has an oval shape. It rises almost to the liver, displacing the intestines superiorly and laterally.

A clot of thick, tenacious mucus forms in the spaces of the cervical canal (the mucus plug), which protects the fetus from infection. The mucus plug dislodges when labour begins at the end of term, producing a sign of labour called ‘bloody show’. Cervical and vaginal secretions increase during pregnancy and are thick, white and more acidic. The increased acidity occurs because of the action of Lactobacillus acidophilus, which changes glycogen into lactic acid. The acidic pH keeps pathogenic bacteria from multiplying in the vagina, but the increase in glycogen increases the risk of candidiasis (commonly called a yeast infection) during pregnancy.

The female over 65 years

In contrast to the slowly declining hormones in the ageing male, the female’s hormonal milieu decreases rapidly. Menopause is cessation of the menses. Usually this occurs around 48 to 51 years, although a wide variation of ages from 35 to 60 years exists. The stage of menopause includes the preceding 1 to 2 years of decline in ovarian function, shown by irregular menses that gradually become further apart and produce a lighter flow. Ovaries stop producing progesterone and oestrogen. Because cells in the reproductive tract are oestrogen dependent, decreased oestrogen levels during menopause bring dramatic physical changes.

The uterus reduces in size because of decreased myometrium. The ovaries atrophy to 1 to 2 cm and are not palpable after menopause. Ovulation still may occur sporadically after menopause. The sacral ligaments relax and the pelvic musculature weakens predisposing the woman to pelvic organ prolapse, particularly in women who have had vaginal births. The cervix decreases in size and looks paler with a thick, glistening epithelium.

The vagina becomes shorter, narrower and less elastic because of increased connective tissue. The vaginal epithelium atrophies, becoming thinner and drier. This results in a fragile mucosal surface that is at risk for bleeding and vaginitis. Decreased vaginal secretions leave the vagina dry and at risk for irritation and pain with intercourse (dyspareunia). The vaginal pH becomes more alkaline, and a decreased glycogen content occurs from the decreased oestrogen. These factors also increase the risk of vaginitis because they create a suitable medium for pathogens. In late older age, externally, the mons pubis looks smaller because the fat pad atrophies. The labia and clitoris gradually decrease in size. Pubic hair becomes thin and sparse. Sexual desire and the need for full sexual expression do not diminish with age.

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

There are varying cultural requirements about the examination of sexual and reproductive function in women, including for some woman the requirement to be examined only by a female healthcare practitioner. You need to ascertain the woman’s requirements before the examination commences. With the recent increase in migration to Australia and New Zealand from Africa, parts of Asia and the Middle East, nurses may care for women who have been subject to female genital mutilation (sometimes referred to as female circumcision).

Female genital mutilation refers to several procedures which involve partial or complete removal of the clitoris; partial or total removal of the clitoris and labia minora with or without excision of the labia majora; infibulation—narrowing of the vaginal introitus by repositioning the labia minora and/or labia majora; or some other form of nonmedical procedure to the genital area. Female genital mutilation is performed for cultural and social rather than religious reasons and is usually performed on young girls before the age of 15 years. The procedure is recognised internationally as a violation of the human rights of women and is illegal in Australia. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2010) 100 to 140 million girls and women are living with the consequences of female genital mutilation.

There are no health benefits of female genital mutilation and the procedure can cause significant physical and psychological harm, including infection and haemorrhage at the time of the procedure, recurrent urinary tract infection, infertility and increased childbirth complications. In 2010 the WHO released a document titled ‘Global strategy to stop health care providers performing female genital mutilation’ in response to findings of a study which found that 18% of all girls who have been subjected to female genital mutilation have had the procedure carried out by healthcare providers, including nurses (pp. 3–4). The International Council of Nurses (ICN) released a position statement in 2004 actively opposing the procedure and any medicalisation of the procedure and reiterated the ICN pledge to eliminate the practice of female genital mutilation by health professionals in any setting.

SUBJECTIVE DATA

Assessment in the area of female reproductive function is closely linked to assessment of bladder function and breast health. Health issues in this area are likely to cause significant distress to the woman (and their partner) and therefore you need to approach the assessment in a tactful and empathic manner. Privacy is of upmost importance and you need to establish a trusting relationship with the person. Detailed questions and physical examination techniques related to urinary and bowel function are covered in Chapters 18 and 20. Because of the sensitive nature of this assessment you should start with a more general health assessment then focus on the specific areas.

| Assessment guidelines and normal findings | Clinical significance and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| Tell me about your menstrual periods: | |

| • Date of your last menstrual period? | LMP–last menstrual period. |

| • Age at first period? | Menarche–mean age at onset at 12–13; delayed onset suggests endocrine or underweight problem. |

| • How often are your periods? Cycle—normally every 18 to 45 days | Amenorrhoea–absent menses. |

| • How many days does your period last? Duration—average 3 to 7 days. | |

| • Usual amount of flow: light, medium, heavy? How many pads or tampons do you use each day or hour? | Menorrhagia–heavy menses. |

| • Any clotting? | Clotting indicates heavy flow or vaginal pooling. |

| • Do you experience any pain or cramps before or during period? How do you treat it? Interfere with daily activities? Any other associated symptoms: bloating, breast tenderness, moodiness? Any spotting between periods? | Dysmenorrhoea. |

| • How many times? | Gravida–number of pregnancies. |

| • How many babies have you had? | Para–number of births (over 20 weeks gestation–live or stillborn) |

| • Any miscarriages or abortions? | Abortions–interrupted pregnancies, including elective abortions and spontaneous miscarriages. |

| • For each pregnancy, describe: duration, any complication, labour and delivery, baby’s sex, birth weight, condition. | |

| • Do you think you may be pregnant now? What symptoms have you noticed? | |

| Menopause–cessation of menstruation. | |

| • Any associated symptoms of menopause (e.g. hot flush, numbness and tingling, headache, palpitations, drenching sweats, mood swings, vaginal dryness, itching)? What have you done about these symptoms if any? | Perimenopausal period from 40 to 55 years has hormone shifts, resulting in vasomotor instability. |

| • If hormone replacement, how much? How is it working? Any side effects? | Side effects of hormone therapy include fluid retention, breast pain or enlargement, vaginal bleeding, possibly breast cancer risk. |

| • Are you using any other therapies to help relieve menopausal symptoms? For example, herbs and other complementary therapies, exercise, yoga. | |

| • How do you feel about going through menopause? | Although this is a normal life stage, reaction varies from acceptance to feelings of loss. |

| For more information on assessment of breast health see Chapter 27. | |

| Take the opportunity to reinforce the need for regular Pap smears. | |

| • Last Pap smear? Results? | |

| • Has your mother ever mentioned taking hormones while pregnant with you? | Maternal ingestion of DES (diethyl-stilboestrol) causes cervical and vaginal abnormalities in female offspring requiring frequent follow-up. |

| For more information on assessment of urinary function see Chapter 18. | |

| • Character or colour: white, yellow-green, grey, curd-like, foul smelling? | Suggests vaginal infection; character of discharge often suggests causative organism (see Table 25.5). |

| • When did this begin? | Acute versus chronic problem. |

| • Is the discharge associated with vaginal itching, rash, pain with intercourse? | |

| • Family history of diabetes? | |

| • What part of your menstrual cycle are you in now? | |

| • Any abdominal pain? | |

| • Any past surgery on uterus, ovaries, vagina? | Assess feelings. Some fear loss of sexual response after hysterectomy, which may cause problems in intimate relationships. |

8. Sexual activity. Often women have a question about their sexual relationship and how it affects their health. Do you? Begin with open-ended question to assess individual needs. Include appropriate questions as a routine:

|

There are validated sexual health/satisfaction assessment tools available (e.g. the female sexual function questionnaire (FSFI) (Rosen, Brown, Heiman et al, 2000)). Women who are concerned about their sexual function should be referred to a medical practitioner/sexual health clinic for further assessment. |

| • Do you and your partner use a contraceptive? Which method? Is this satisfactory? Do you have any questions about method? | Assess smoking history. Oral contraceptives, together with cigarette smoking, increase the risk of vascular problems. |

| • Which methods have you used in the past? Have you and partner discussed having children? | |

| • Have you ever had any problems becoming pregnant? | Infertility is considered after 1 year of engaging in unprotected sexual intercourse without conceiving. |

| An STI includes all conditions that can be transmitted during intercourse or intimate sexual contact with an infected partner. | |

| Additional history for infants and children | |

| For more information on assessment of urinary function see Chapter 18. | |

| Occurs with poor perineal hygiene or insertion of foreign body in vagina. | |

3. Questions related to suspected child abuse. Registered nurses in Australia have a legal requirement to report suspected cases of child abuse and neglect. This is known as mandatory reporting. All Australian states and territories possess mandatory reporting requirements of some description. You should make sure that you understand the requirements within your area—http://www.aifs.gov.au/nch/pubs/sheets/rs3/rs3.html Where appropriate, you need to make a judgment about the specific situation; however, examples of possible questions include: |

For more information about signs and symptoms related to child abuse refer to Chapter 5. |

| • Has anyone ever touched in between your legs and you did not want them to? Sometimes that happens to children and it’s not okay. You should know that you have not been bad. You should try to tell a big person about it. Can you tell me three different big people you trust who you could talk to? | For prevention, teach the child that it is not okay for someone to look at or touch their genitals while telling them it is a secret. Naming three trusted adults will include someone outside the family– important, since most molestation is by a parent. |

| Additional history for preadolescents and adolescents | |

| Use the following questions, as appropriate, to assess sexual growth and development and sexual behaviour. First | |

| • Ask questions that seem appropriate for girl’s age but be aware that norms vary widely. When in doubt, it is better to ask too many questions than to omit something. Children obtain information, often misinformation, from the media and from peers at surprisingly early ages. You can be sure your information will be more thoughtful and accurate. | |

| • Ask direct, matter-of-fact questions. Avoid sounding judgmental. | |

| • Start with a permission statement, ‘Often girls your age experience…’ This conveys that it is normal to think or feel a certain way. | |

| • Try the open-ended, ‘When did you…’ rather than ‘Do you…’ This is less threatening because it implies that the topic is normal and unexceptional. | |

| 1 Around age 9 or 10, girls start to develop breasts and pubic hair. Have you ever seen charts and pictures of normal growth patterns for girls? Let us go over these now. | |

| 2 Have your periods started? How did you feel? Were you prepared or surprised? | Assess attitude of girl and parents. Note inadequate preparation or attitude of distaste. |

3. Who in your family do you talk to about your body changes and about sex information? How do these talks go? Do you think you get enough information? What about sex education classes at school? Is there a teacher, a nurse or doctor, a minister, a counsellor to whom you can talk? Often girls your age have questions about sexual activity. Do you have questions? Are you going out with someone? Do you and your boyfriend have intercourse? Are you using condoms? What kind of protection did you use the last time you had sex? Avoid the term ‘sexually active’, which is ambiguous. |

|

| Teach STI risk reduction. | |

| For more information about signs and symptoms related to child abuse refer to Chapter 5. | |

| • Sometimes a person touches a girl in a way that she does not want them to. Has that ever happened to you? If that happens, the girl should remember it is not her fault. She should tell another adult about it. | |

| Additional history for the woman over 65 years | |

| Postmenopausal bleeding warrants further assessment and referral. | |

| Associated with atrophic vaginitis. | |

| Occurs with weakened pelvic musculature and uterine prolapse. |

OBJECTIVE DATA

The techniques and extent of the physical examination in this area will depend on the presenting signs and symptoms. Nurses working in sexual health clinics and some urological settings may need to develop skill in a more comprehensive assessment of female sexual and reproductive function. For most nurses asking questions about the woman’s reproductive health will be sufficient for a nursing assessment.

TABLE 25.5 Vulvovaginal inflammations

S, Subjective data; O, objective data.

| Preparation | Equipment needed |

|---|---|

| Assemble the equipment before helping the woman into position. Arrange the equipment within easy reach. |

POSITION

Initially, the woman should be sitting up. An equal-status position is important to establish trust and rapport before more invasive examination.

Before you start—after gaining the woman’s consent to be examined:

• Have her empty the bladder before the examination.

• Ask if she would like a friend, family member or chaperone present. Position this person by the woman’s head to maintain privacy.

• Explain each step in the examination before you do it.

• Assure the woman she can stop the examination at any point should she feel any discomfort.

• Communicate throughout the examination. Maintain a dialogue to share information.

| Procedures and normal findings | Abnormal findings and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| For the examination of the external genitalia (or prior to urinary catheterisation), the woman should be assisted to lie down in the supine position with one or two pillows under her head. Ensure privacy before exposing the genital area and cover as much bare skin as possible. Have the woman place her ankles together and let her knees drop to the side exposing the perineal area. | |

| EXTERNAL GENITALIA | |

| Inspection | |

| Note: | |

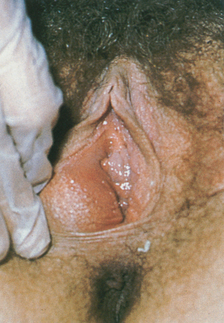

• Skin colour (Fig 25.3). |

Refer any suspicious pigmented lesion for biopsy. |

| Swelling. | |

• Clitoris (Fig 25.4). |

Excoriation, nodules, rash or lesions (see Table 25.2). |

| Inflammation or lesions. | |

| Polyp. | |

| Foul-smelling, irritating discharge. | |

| DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS | |

| Infants and children | |

| Preparation | |

• Infant—place on examination table. • Toddler/preschooler—place on parent’s lap. Frog-leg position—hips flexed, soles of feet together and up to bottom. Preschool child may want to separate her own labia. No drapes—the young girl wants to see what you are doing. • School-age child—place on examination table, frog-leg position, no drapes. During childhood, a routine screening is limited to inspection of the external genitalia to determine that (1) the structures are intact, (2) the vagina is present and (3) the hymen is patent. |

|

| The newborn’s genitalia are somewhat engorged. The labia majora are swollen, the labia minora are prominent and protrude beyond the labia majora, the clitoris looks relatively large and the hymen appears thick. Because of transient engorgement, the vaginal opening is more difficult to see now than it will be later. Place your thumbs on the labia majora. Push laterally while pushing the perineum down, and try to note the vaginal opening above the hymenal ring. Do not palpate the clitoris because it is very sensitive. | Ambiguous genitalia are rare but are suggested by a markedly enlarged clitoris, fusion of the labia (resembling scrotum), and palpable mass in fused labia (resembling testes) (see Table 25.8). |

| A sanguineous vaginal discharge or leucorrhoea (mucoid discharge) are normal during the first few weeks because of the maternal oestrogen effect. (This also may cause transient breast engorgement and secretion.) During the early weeks, the genital engorgement resolves, and the labia minora atrophy and remain small until puberty (Fig 25.5). | Lesions, rash. |

| Between the ages of 2 months and 7 years, the labia majora are flat, the labia minora are thin, the clitoris is relatively small and the hymen is tissue-paper thin. Normally, no irritation or foul-smelling discharge is present. | |

| In the young school-age girl (7 to 10 years), the mons pubis thickens, the labia majora thicken and the labia minora become slightly rounded. Pubic hair appears beginning around age 11 years, although sparse pubic hair may occur as early as age 8 years. Normally, the hymen is perforate. | |

| Almost always in these age groups, an external examination will suffice. If needed, an internal pelvic examination is best performed by a paediatric gynaecologist using specialised instruments. | |

| The woman over 65 years | |

| Natural lubrication is decreased; to avoid a painful examination, take care to lubricate the examining hand adequately. | |

| Menopause and the resulting decrease in oestrogen production cause numerous physical changes. Pubic hair gradually decreases, becoming thin and sparse in later years. The skin is thinner and fat deposits decrease, leaving the mons pubis smaller and the labia flatter. Clitoris size also decreases after age 60 years. |

FURTHER OBJECTIVE ASSESSMENT FOR ADVANCED PRACTICE

The assessments that are described in the following sections require advanced skill and scope of practice. Nurses working in specialist woman’s health and sexual health settings, and urological and continence nurses, need to develop these skills. Advanced assessment for infants and children would be performed by specialist neonatal and paediatric nurses, some midwives and maternal and child health nurses.

TABLE 25.2 Abnormalities of the external genitalia

S, Subjective data; O, objective data.

TABLE 25.8 Abnormalities in paediatric genitalia

|

| Ambiguous genitalia |

| Female pseudohermaphroditism is a congenital anomaly resulting from hyperplasia of the adrenal glands, which exposes the female fetus to excess amounts of androgens. This causes masculinised external genitalia, here shown as enlargement of the clitoris and fusion of the labia. Ambiguous means the enlarged clitoris here may look like a small penis with hypospadias, and the fused labia look like an incompletely formed scrotum with absent testes. Other forms of intersexual conditions occur, and the family must be referred for diagnostic evaluation. |

|

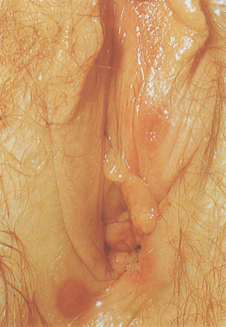

| Vulvovaginitis in child |

| This infection is caused by Candida albicans in a diabetic child. Symptoms include pruritus and burning when urine touches excoriated area. Examination shows red, shiny, oedematous vulva, vaginal discharge, excoriated area from scratching. Other, more common causes of vulvovaginitis in the prepubertal child include infection from a respiratory or bowel pathogen, sexually transmitted disease or presence of a foreign body. |

| Preparation | Equipment needed |

|---|---|

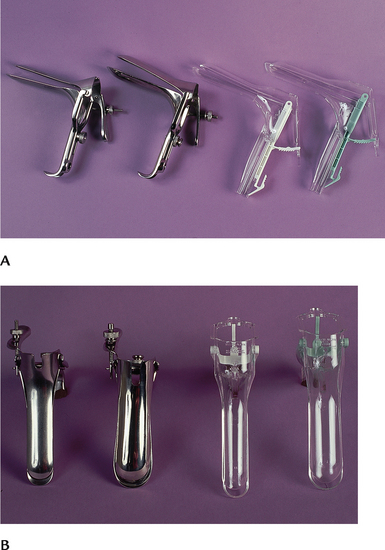

| Familiarise yourself with the vaginal speculum before the examination. Practise opening and closing the blades, locking them into position and releasing them. Try both metal and plastic types. Note that the plastic speculum locks and unlocks with a resounding click that can be alarming to the uninformed woman. | In addition to the equipment listed previously you will require: Vaginal speculum of appropriate size (Fig 25.6) Materials for cytological study–this is dependent on the preference of the laboratory. Make yourself familiar with the equipment and how to collect, prepare and transport the specimen. |

POSITION

See previous comments about positioning of the woman. Internal examination usually follows examination of external structures. Take time to reconfirm consent to be examined internally.

| Procedures and normal findings | Abnormal findings and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| Inspection | |

In addition to the detailed inspection described previously, you may need to assess for pelvic organ prolapse and stress incontinence. While observing the perineum, ask the woman to cough and note any loss of urine when coughing. Observe for any sign of bulging of the vaginal walls at the introitus and bulging of the urethral meatus. There should be no prolapse of the vaginal walls and no urine loss during coughing. |

Loss of urine when coughing is an indicator of stress incontinence. Bulging of the anterior vaginal wall is termed a cystocele where the pelvic musculature fails to support the bladder and it falls posteriorly into the vagina. This can cause voiding dysfunction and incontinence. Similarly, a bulge in the posterior vaginal wall is termed a rectocele. A rectocele can cause defecatory dysfunction and can contribute to constipation. Any degree of pelvic organ prolapse should be referred to a medical practitioner for further assessment. |

| Palpation | |

| Assess the urethra and Skene’s glands (Fig 25.7). Dip your gloved finger in a bowl of warm water to lubricate. Then insert your index finger into the vagina, and gently milk the urethra by applying pressure up and out. This procedure should produce no pain. If any discharge appears, culture it. | |

| Assess Bartholin’s glands. Palpate the posterior parts of the labia majora with your index finger in the vagina and your thumb outside (Fig 25.8). Normally, the labia feel soft and homogeneous. | Swelling (see Table 25.2). |

| Palpate the perineum. Normally, it feels thick, smooth and muscular in the nulliparous woman, and may be thinner and more rigid in the multiparous woman. | |

| Insert a gloved finger into the vagina and assess for tenderness, decent of the cervix, anterior and posterior vaginal wall | |

| Assessment of pelvic muscle strength. | |

| This is performed to: | |

• Establish a baseline of neuromuscular function and contractility of the pelvic floor muscles; • Assess the woman’s ability to identify isolate, contract and relax the pelvic floor muscles (Gray and Moore, 2009). |

|

| Good pelvic muscle function is important in maintaining the position of pelvic organs and structures and in maintaining urinary and fecal continence. | |

| Insert two gloved fingers (index and middle fingers) into the woman’s vagina (approx. 4 cm), spread the fingers laterally in the anterior–posterior position and ask the woman to squeeze the pelvic floor muscles around your fingers. | Absent or decreased contraction–little sensation of pressure on the examiner’s fingers. |

| You should feel a brisk contraction of the muscles firmly and evenly around | Inability to maintain the contraction |

| Women with poor pelvic floor muscle strength are likely to experience urinary incontinence and should be referred to a continence nurse advisor or continence physiotherapist for further assessment and development of an individualised pelvic floor muscle-strengthening program. | |

• Assess the duration of the contraction (in seconds)—normally 36 seconds • Number of contractions that can be performed before the muscle fatigues • Assess how fast the woman can contract the muscles. Make sure that you allow the woman to rest the muscles for a few seconds between contractions. • Assess extent of muscle movement. Normally the contraction should lift the examiner’s fingers upwards. Note the evenness of the contraction (anterior-posterior, circumferential) (Dolman, 2007; Gray and Moore, 2009; Neuman and Laycock, 2008) |

|

| INTERNAL GENITALIA | |

| Speculum examination | |

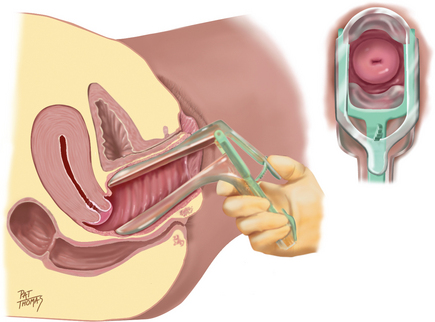

| Select the proper-sized speculum. Warm and lubricate the speculum under warm running water. Avoid gel lubricant at this point because it is bacteriostatic and would distort cells in the cytology specimen you will collect. | |

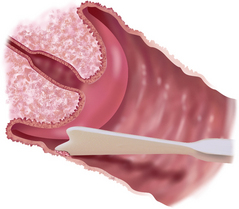

| A good technique is to dedicate one hand to the patient and the other hand to picking up equipment in the room. For example, hold the speculum in your left hand (the equipment hand), with the index and the middle fingers surrounding the blades and your thumb under the thumbscrew. This prevents the blades from opening painfully during insertion. With your right index and middle fingers (the patient hand), push the introitus down and open to relax the pubo-coccygeal muscle (Fig 25.9). Tilt the width of the blades obliquely and insert the speculum past your right fingers, applying any pressure downwards. This avoids pressure on the sensitive urethra above it. | |

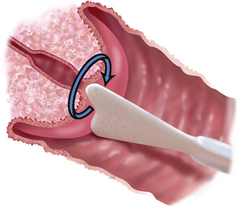

| Ease insertion by asking the woman to bear down. This method relaxes the perineal muscles and opens the introitus. (With experience, you can combine speculum insertion with assessing the support of the vaginal muscles.) As the blades pass your right fingers, withdraw your fingers. Now change the hand holding the speculum to your right hand and turn the width of the blades horizontally. Continue to insert in a 45-degree angle downwards towards the small of the woman’s back (Fig 25.10). This matches the natural slope of the vagina. | |

| After the blades are fully inserted, open them by squeezing the handles together (Fig 25.11). The cervix should be in full view. Sometimes this does not occur (especially with beginning examiners) because the blades are angled above the location of the cervix. Try closing the blades, withdrawing about halfway and reinserting in a more downwards plane. Then slowly sweep upwards. Once you have the cervix in full view, lock the blades open by tightening the thumbscrew. | |

| Inspect the cervix and its os | |

| Note: | |

| Redness, inflammation. Pallor with anaemia. Cyanotic other than with pregnancy (see Table 25.4). | |

| Lateral position may be due to adhesion or tumour. Projection of more than 3 cm may be a prolapse. | |

| Hypertrophy of more than 4 cm occurs with inflammation or tumour. | |

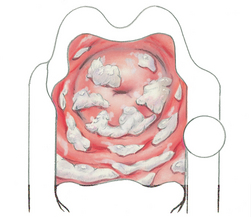

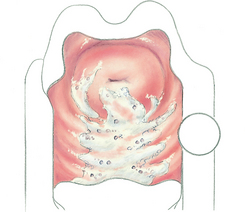

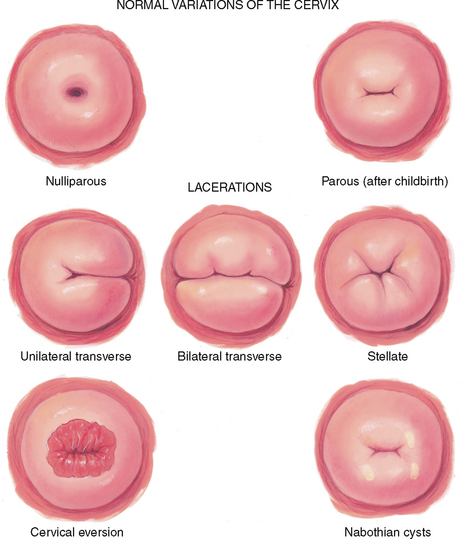

• Os. This is small and round in the nulliparous woman. In the parous woman, it is a horizontal irregular slit and also may show healed lacerations on the sides (Fig 25.12). |

|

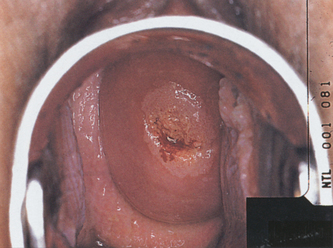

• Surface. This is normally smooth, but cervical eversion, or ectropion, may occur normally after vaginal deliveries. The endocervical canal is everted or ‘rolled out’. It looks like a red, beefy halo inside the pink cervix surrounding the os. It is difficult to distinguish this normal variation from an abnormal condition (e.g. erosion or carcinoma) and biopsy may be needed. |

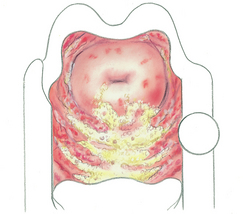

Surface reddened, granular and asymmetrical, particularly around os. Any lesions: white patch on cervix; strawberry spot. Refer any suspicious red, white or pigmented lesion for biopsy (see erosion, ulceration and carcinoma, Table 25.4). |

| Nabothian cysts are benign growths that commonly appear on the cervix after childbirth. They are small, smooth, yellow nodules that may be single or multiple. Less than 1 cm, they are retention cysts caused by obstruction of cervical glands. | Cervical polyp–bright red growth protruding from the os (see Table 25.4). |

| Foul-smelling, irritating, with yellow, green, white or grey discharge (see Table 25.5). | |

| If secretions are copious, swab the area with a thick-tipped swab. This method sponges away secretions, and you have a better view of the structures. | |

| Obtain cervical smears and cultures | |

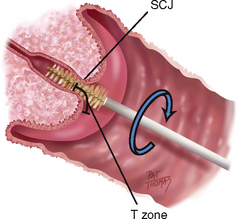

The Papanicolaou, or Pap, smear screens for cervical cancer. Do not obtain during the woman’s menses or if a heavy infectious discharge is present. Instruct the woman not to douche, have intercourse or put anything into the vagina within 24 hours before collecting the specimens. Obtain the Pap smear before other specimens so you will not disrupt or remove cells. Laboratories may vary in method, but usually the test consists of three specimens: Vaginal pool. Gently rub the blunt end of an Ayre spatula (or cervical brush depending on the equipment required by the particular laboratory) over the vaginal wall under and lateral to the cervix (Fig 25.13). Wipe the specimen on a slide and spray with fixative immediately. If the mucosa is very dry (as in a postmenopausal woman), moisten a sterile swab with normal saline solution to collect this specimen. |

|

| Cervical scrape (Fig 25.14). Insert the bifid end of the Ayre spatula into the vagina with the more pointed bump into the cervical os. Rotate it 360 to 720 degrees, using firm pressure. The rounded cervix fits snugly into the spatula’s groove. The spatula scrapes the surface of the squamocolumnar junction and cervix as you turn the instrument. Spread the specimen from both sides of the spatula onto a glass slide. Use a single stroke to thin out the specimen, not a back-and-forth motion. This specimen is important for the adolescent whose endocervical cells have not yet migrated into the endocervical canal. | |

| Endocervical specimen (Fig 25.15). Insert a cervical brush (instead of a cotton applicator) into the os. A cervical brush gives a higher yield of endocervical cells at the squamocolumnar junction, or SCJ, and is safe for use during pregnancy (Stillson, 1997). The woman may feel a slight pinch with the brush and scant bleeding may occur. For this reason, collect the endocervical specimen last so that bleeding will not obscure cytological evaluation. | |

Rotate the brush 720 degrees in ONE direction in the endocervical canal, either clockwise or counterclockwise. Then rotate the brush gently on a slide to deposit all the cells. Rotate in the opposite direction from the one in which you obtained the specimen. Avoid leaving a thick specimen that would be hard to read under the microscope. Immediately (within 2 seconds) spray the slide with fixative to avoid drying. For the woman after hysterectomy whose cervix has been removed, collect a scrape from the end of the vagina and a vaginal pool. Immediately spray the slides with fixative. The frosted ends of the slides should be labelled with the woman’s name. Send these to the laboratory with the following necessary data: |

|

| These data are important for accurate interpretation; for example, a specimen may be interpreted as positive unless the laboratory technicians know the woman has had prior radiation treatment. Newer methods of cervical screening use a liquid-based thin-layer preparation. Instead of transferring the cervical sample onto a slide, the swab with the sample is deposited into a transportation fluid. The thin uniform layer of suspended cervical cells has improved sensitivity and a lower false–positive rate (Royal College of Pathologists of Australia, 2009). | |

| To screen for STIs, and if you note any abnormal vaginal discharge, obtain a specimen of the discharge. Insert a sterile cotton applicator into the os, rotate it 360 degrees and leave it in place 10 to 20 seconds for complete saturation. Insert into labelled specimen. Follow laboratory guidelines for collection, preparation and transport of specimens for possible STIs. | |

| Inspect the vaginal wall | |

| Loosen the thumbscrew but continue to hold the speculum blades open. Slowly withdraw the speculum, rotating it as you go, to fully inspect the vaginal wall. Normally, the wall looks pink, deeply rugated, moist and smooth, and is free of inflammation or lesions. Normal discharge is thin and clear, or opaque and stringy, but always odourless. | Leucoplakia, appears as spot of dried white paint. Vaginal discharge: thick, white and curd-like with candidiasis; profuse, watery, grey-green and frothy with trichomoniasis; or any grey, green-yellow, white or foul-smelling discharge (see Table 25.5). |

| When the blade ends near the vaginal opening, let them close, but be careful not to pinch the mucosa or catch any hairs. Turn the blades obliquely to avoid stretching the opening. Place the metal speculum in a basin to be cleaned later and soaked in a sterilising and disinfecting solution; discard the plastic variety. Discard your gloves and wash hands. | |

| Bimanual examination | |

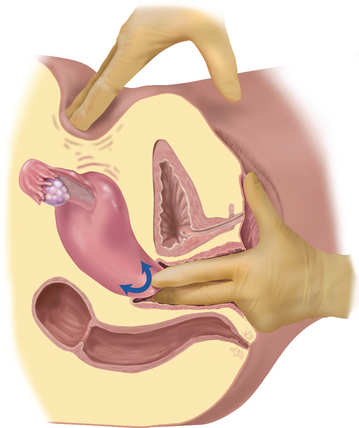

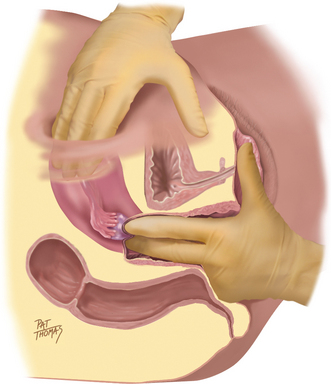

| Drop lubricant onto the first two fingers of your gloved intravaginal hand (Fig 25.16). Assume the ‘obstetric’ position with the first two fingers extended, the last two flexed onto the palm and the thumb abducted. Insert your fingers into the vagina, with any pressure directed posteriorly. Wait until the vaginal walls relax, then insert your fingers fully. | |

| You will use both hands to palpate the internal genitalia to assess their location, size and mobility and to screen for any tenderness or mass. One hand is on the abdomen while the other (often the dominant, more sensitive hand) inserts two fingers into the vagina (Fig 25.17). It does not matter which you choose as the intravaginal hand; try each way, and settle on the most comfortable method for you. | |

| Palpate the vaginal wall. Normally, it feels smooth and has no area of induration or tenderness. | |

| Cervix. Locate the cervix in the midline, often near the anterior vaginal wall. The cervix points in the opposite direction of the fundus of the uterus. Palpate using the palmar surface of the fingers. Note these characteristics of a normal cervix: | |

| Irregular. | |

• Mobility—With a finger on either side, move the cervix gently from side to side. Normally, this produces no pain (Fig 25.18). |

Immobile with malignancy. |

| Palpate all around the fornices; the wall should feel smooth. | Painful with inflammation or ectopic pregnancy. |

| Next, use your abdominal hand to push the pelvic organs closer for your intravaginal fingers to palpate. Place your hand midway between the umbilicus and the symphysis; push down in a slow, firm manner, fingers together and slightly flexed. Brace the elbow of your pelvic arm against your hip, and keep it horizontal. The woman must be relaxed. | |

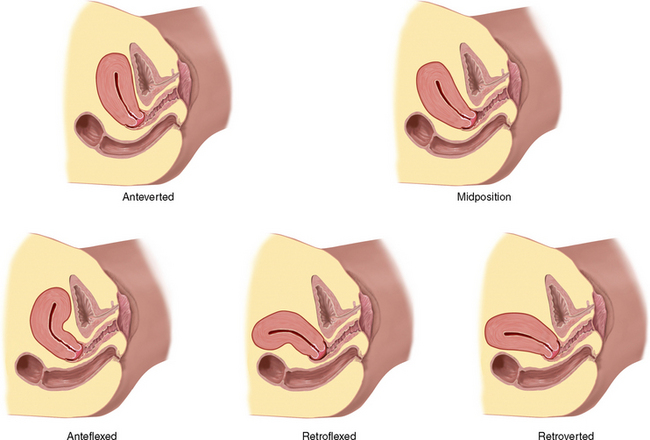

| Uterus. With your intravaginal fingers in the anterior fornix, assess the uterus. Determine the position, or version, of the uterus (Fig 25.19). This compares the long axis of the uterus with the long axis of the body. In many women, the uterus is anteverted; you palpate it at the level of the pubis with the cervix pointing posteriorly. Two other positions occur normally (midposition and retroverted), as well as two aspects of flexion, where the long axis of the uterus is not straight but is flexed. | |

| Palpate the uterine wall with your fingers in the fornices. Normally, it feels firm and smooth, with the contour of the fundus rounded. It softens during pregnancy. Bounce the uterus gently between your abdominal and intravaginal hand. It should be freely movable and nontender. | Enlarged uterus (see Table 25.6). |

| Adnexa. Move both hands to the right to explore the adnexa. Place your abdominal hand on the lower quadrant just inside the anterior iliac spine and your intravaginal fingers in the lateral fornix (Fig 25.20). Push the abdominal hand in and try to capture the ovary. Often, you cannot feel the ovary. When you can, it normally feels smooth, firm and almond shaped, and is highly movable, sliding through the fingers. It is slightly sensitive but not painful. The fallopian tube is not palpable normally. No other mass or pulsation should be felt. | Enlarged adnexa. Nodules or mass in adnexa. Markedly tender (see Table 25.7). Pulsation or palpable fallopian tube suggests ectopic pregnancy; this warrants immediate referral. |

A note of caution—normal adnexal structures are often not palpable. Be careful not to mistake an abnormality for a normal structure. To be safe, consider abnormal any mass that you cannot positively identify, and refer the woman for further study. Move to the left to palpate the other side. Then, withdraw your hand and check secretions on the fingers before discarding the glove. Normal secretions are clear or cloudy and odourless. Following the examination make sure that you give the woman some tissues to clean herself and allow time for her to redress before completing the assessment. |

|

| DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR ADVANCED PRACTICE | |

| The adolescent | |

| The adolescent girl has special needs during the genitalia examination. Examine her alone, without the parent present. Assure her of privacy and confidentiality. Allow plenty of time for health education and discussion of pubertal progress. Assess her growth velocity and menstrual history, and use the SMR charts to teach breast and pubic hair development. Assure her that increased vaginal fluid (physiological leucorrhoea) is normal because of the oestrogen effect. | |

For advanced practice: Perform pelvic examination when contraception is desired, when the girl’s sexual activity includes intercourse. Start periodic Pap smears when intercourse begins. Although the techniques of the examination are listed in the adult section, you will need to provide additional time and psychological support for the adolescent having her first pelvic examination. The experience of the first pelvic examination determines how the adolescent will approach future care. Your accepting attitude and gentle, unhurried approach are important. You have a unique teaching opportunity here. Take the time to teach, using the girl’s own body as illustration. Your frank discussion of anatomy and sexual behaviour communicates that these topics are acceptable to discuss and not taboo with healthcare providers. This affirms the girl’s self-concept. |

|

| During the bimanual examination, note that the adnexa are not palpable in the adolescent. | Pelvic or adnexal mass. |

| The pregnant female | |

Depending on the week of gestation of the pregnancy, inspection shows the enlarging abdomen (see Fig. 28.1). The height of the fundus ascends gradually as the fetus grows. At 16 weeks, the fundus is palpable halfway between the symphysis and umbilicus; at 20 weeks, at the lower edge of the umbilicus; at 28 weeks, halfway between the umbilicus and the xiphoid; and at 34 to 36 weeks, almost to the xiphoid. Then, close to term, the fundus drops as the fetal head engages in the pelvis. The external genitalia show hyperaemia of the perineum and vulva because of increased vascularity. Varicose veins may be visible in the labia or legs. Haemorrhoids may show around the anus. Both are caused by interruption in venous return from the pressure of the fetus. Internally, the walls of the vagina appear violet or blue (Chadwick’s sign) because of hyperaemia. The vaginal walls are deeply rugated and the vaginal mucosa thickens. The cervix looks blue, feels velvety and feels softer than in the nonpregnant state, making it a bit more difficult to differentiate from the vaginal walls. During bimanual examination, the isthmus of the uterus feels softer and is more easily compressed between your two hands (Hegar’s sign). The fundus balloons between your two hands; it feels connected to, but distinct from, the cervix because the isthmus is so soft. |

|

| Search the adnexal area carefully during early pregnancy. Normally, the adnexal structures are not palpable. | An ectopic pregnancy has serious consequences (see Table 25.7). |

| The female over 65 years | |

| Natural lubrication is decreased; to avoid a painful examination, take care to lubricate instruments and the examining hand adequately. Use the Pedersen speculum (rather than the Graves) because its narrower, flatter blades are more comfortable in women with vaginal stenosis or dryness. | |

| Menopause and the resulting decrease in oestrogen production cause numerous physical changes. Pubic hair gradually decreases, becoming thin and sparse in later years. The skin is thinner and fat deposits decrease, leaving the mons pubis smaller and the labia flatter. Clitoris size also decreases after age 60 years. | |

| Internally, the rugae of the vaginal walls decrease, and the walls look pale pink because of the thinned epithelium. The cervix shrinks and looks pale and glistening. It may retract, appearing to be flush with the vaginal wall. In some, it is hard to distinguish the cervix from the surrounding vaginal mucosa. Alternatively, the cervix may protrude into the vagina if the uterus has prolapsed. | |

With the bimanual examination, you may need to insert only one gloved finger if vaginal stenosis exists. The uterus feels smaller and firmer, and the ovaries are not palpable normally. Prior surgery for hysterectomy does not preclude the need for routine gynaecological care, including the Pap smear. The Pap smear can help detect gynaecological malignancies even when the cervix has been removed. Be aware that older women may have special needs and will appreciate the following plans of care: for those with arthritis, taking a mild analgesic or anti-inflammatory before the appointment may ease joint pain in positioning; schedule appointment times when joint pain or stiffness is at its least; allow extra time for positioning and ‘unpositioning’ after the examination; and be careful to maintain dignity and privacy. |

Refer any mass for prompt evaluation. |

TABLE 25.4 Abnormalities of the cervix

S, Subjective data; O, objective data.

TABLE 25.6 Uterine enlargement

S, Subjective data; O, objective data.

TABLE 25.7 Adnexal enlargement

S, Subjective data; O, objective data.

Promoting a healthy lifestyle Human papillomavirus vaccine

Vaccine to prevent cervical cancer—a breakthrough in cancer prevention

In November 2006, the Australian Government announced funding for a human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination program. The New Zealand Government commenced a similar vaccination program in 2008. HPV consists of a group of viruses that can cause skin and genital warts and some cancers, including cervical cancer. The vaccine targets HPV, the virus responsible for most cases of cervical cancer. It is recommended for girls and women before they become sexually active because it is not effective if the individual is already infected with HPV. The vaccine (Gardasil®) is given in three separate injections over a 6-month period. HPV is a very common sexually transmitted virus. Most people who have had sex, both men and women, have been infected at some point in their lives. Most people never even know they have HPV because the virus usually does not cause any symptoms. However, sometimes the virus lingers in a woman’s cervix and can cause changes that may eventually lead to cervical cancer. Other than the vaccine, the only way to prevent HPV is to abstain from all sexual activity. It is not known how much protection condoms provide against HPV because those areas not covered by a condom can be exposed to the virus.

However, it is important to remind women that being immunised against HPV does not mean that women can forget about routine pelvic exams and Pap tests. The vaccine will protect against the major types of HPV that cause cervical cancer, but not all types. Pap tests are able to detect cell changes in the cervix before they turn into cancer, at an early, curable stage. The current cervical screening recommendations are that women should have a Pap smear every two years from the age of 18 or two years after having sex, whichever is later.

Australian HPV Vaccination program: http://www.immunise.health.gov.au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/nips2

National (Australian) Cervical Cancer Screening Program: http://www.cancerscreening.gov.au/internet/screening/publishing.nsf/Content/guide

New Zealand Government National Cervical Screening Program: http://www.nsu.govt.nz/current-nsu-programmes/564.asp

New Zealand Ministry of Health HPV Program: http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexmh/immunisation-diseasesandvaccines-hpv-programme

DOCUMENTATION AND CRITICAL THINKING

FOCUSED ASSESSMENT: CLINICAL CASE STUDY

JK, a 27-year-old woman, presents at clinic with ‘urinary burning, vaginal itching and discharge (4 days)’.

Subjective

3 weeks ago: treated at clinic for bronchitis with erythromycin. Improved within 5 days. She is married and has never been pregnant.

4 to 5 days ago: noted burning on urination, intense vaginal itching, thick, white, ‘smelly’ discharge.

No previous history of vaginal infection, urinary tract infection or pelvic surgery. Monogamous sexual relationship, has used low-oestrogen birth control pills for 3 years with no side effects.

ABNORMAL FINDINGS FOR ADVANCED PRACTICE

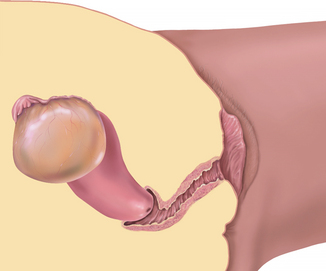

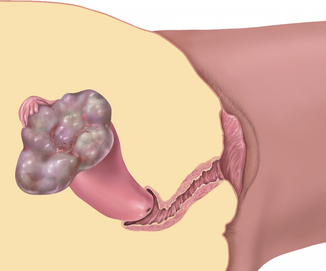

TABLE 25.3 Abnormalities of the pelvic musculature

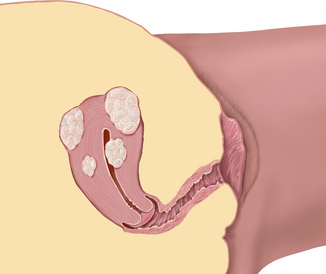

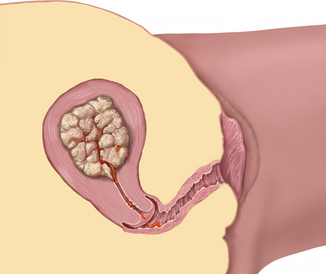

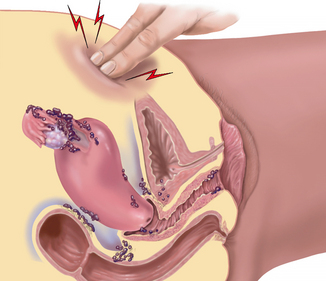

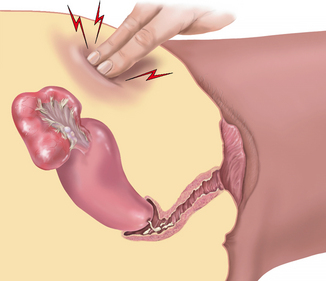

|

| Cystocele (with prolapse) |

|

| Rectocele |

|

| Uterine prolapse |

| O: With straining or standing, uterus protrudes into vagina. Prolapse is graded: first degree, cervix appears at introitus with straining; second degree, cervix bulges outside introitus with straining; third degree (in this case), whole uterus protrudes even without straining–essentially, uterus is inside out. |

S, Subjective data; O, objective data.

Baessler K, Schussler B, Burgio KL, et al. Pelvic floor reeducation: principles and practice, 2nd edn., London: Springer-Verlag, 2008.

Bo K, Sherburn M. Evaluation of female pelvic-floor muscle function and strength. Physical Therapy. 2005;85(3):269–282.

Carcio HA, Secor MC. Advanced health assessment of women, 2nd edn. New York: Springer Publishing Company, 2010.

Cardozo L, Staskin D. Textbook of female urology and urogynaecology, 2nd edn. Abingdon: Informa Healthcare, 2010.

Dean BB, et al. Evaluating the criteria used for identification of PMS. J Womens Health. 2006;15:546–555.

Dolman M. Mainly women. In: Getliffe K, Dolman M. Promoting continence: a clinical and research resource. 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Baillière Tindall; 2007:55–84.

Fraser DM, Cooper MA. Myles textbook for midwives, 15th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2009.

Freeto J, Jay S. “What’s really going on down there?” A practical approach to the adolescent who has gynecologic complaints. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:529–545.

Gohm J, Flynn M. Examination obstetrics and gynaecology, 3rd edn. Chatswood: Elsevier, 2010.

Gray M, Moore KN. Urologic disorders: adult and paediatric care. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2009.

International Council of Nurses (ICN), Position statement: elimination of female genital mutilation. ICN, Geneva, 2004. Available at http://www.icn.ch/images/stories/documents/publications/position_statements/A04_Elimination_Female_Genital_Mutilation.pdf.

Jenkins G, Kemnitz C, Tortora GJ. Anatomy and physiology: from science to life, 2nd edn. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

Jones S. A step-by-step approach to HIV/AIDS. Nurse Pract. 2006;31:26–41.

Kingsberg S. Taking a sexual history. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33:535–547.

Lonergan S, Hern G. Refresher course on sexually transmitted diseases. Emerg Med. 2006;38:33–42.

Marieb EM, Hoehn K. Human anatomy and physiology, 8th edn. San Francisco: Pearson Benjamin Cummings, 2010.

Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291–303.

Montif GRG, Baker DA. Infectious disease in obstetrics and gynaecology. London: Informa Healthcare, 2008.

Moore KN, Pathology and management of acute and chronic urinary retention. Doughty DB, ed. Urinary and fecal incontinence: current management concepts, 2nd edn., St Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2006.

Neuman D, Laycock J. Clinical evaluation of the pelvic floor. In: Baessler K, Schussler B, Burgio KL, et al. Pelvic floor reeducation: principles and practice. 2nd edn. London: Springer-Verlag; 2008:91–104.

Patel D, Pearlman M. Point-of-care diagnosis of STI’s in women. Contemp OB/GYN. 2006;51:68–74.

Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2000;26:191–208.

Royal College of Pathologists of Australia. RCPA Manual. Available at http://www.rcpamanual.edu.au/.

Stillson T, Knight AL, Elswick RK. The effectiveness and safety of two cervical cytologic techniques during pregnancy. J Fam Pract. 1997;45:159–163.

World Health Organization. 2010: Female genital mutilation. Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global strategy to stop healthcare providers from performing female genital mutilation, WHO/RHR/10.9, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNFPA, UNICEF, UNHCR, UNIFEM, WHO, FIGO, ICN, IOM, WCPT, WMA, MWIA. Geneva, 2010, WHO. Available at http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/en/index.html.

Xu F, et al. Trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 sero-prevalence in the United States. JAMA. 2006;296:964–973.