Chapter 6 Community-based nursing care

1. Describe how factors changing the healthcare delivery system are influencing the place of nursing care from hospital to community.

2. Outline the role of community nurses.

3. Describe community-based care settings and the services provided in these settings.

4. Describe the challenges of nurses working in community settings.

The Australian population is ageing, creating an unprecedented demand for nurses and increased pressure on the healthcare system. In addition, social, economic, technological and health factors such as an increase in the prevalence of chronic conditions are driving the demand for a shift in healthcare delivery from hospitals into community settings. History provides the context for this current situation, as this can be seen as a return to a mode of care delivery that was prevalent in Australia for more than 100 years. Since at least the late 19th century in Australia and New Zealand (and earlier in the UK) community nurses have had an important role to play in primary healthcare as well as in the delivery of acute care in people’s homes. Nurses 100 years ago were often sponsored by or had affiliations with religious orders, which laid the foundations of faith-inspired models of community nursing that remain strong today.1 Nurses’ early work placed an emphasis on education about sanitation and public health at a time when running water was not accessible, many parts of the larger cities still had open sewerage systems and infant mortality was very high. Nurses were actively involved in their local communities, improving the health and wellbeing of families living in these conditions. Indigenous Australians had their own approaches to nursing and caring for their family groups; however, there is little documented evidence about how this healthcare was actually undertaken.

During the latter part of the 20th century in Australia, and slightly earlier in New Zealand, healthcare became synonymous with hospital care due to advances in anaesthesia, surgical intervention and antibiotics, and most healthcare occurred in the hospital setting.2,3 However, in the 1980s and 1990s the advent of escalating healthcare costs and the introduction of case payments associated with the tertiary sector saw hospitals consider the community as a way of reducing or shifting costs and improving health outcomes for patients. Hospitals began to either outsource to community-based nursing and care services or create their own outreach services, such as Hospital in the Home programs. Economics has not been the only driver of this change, as there has been recognition that hospitals are risky places for people to be when it comes to complications such as healthcare-associated infections, falls and medication errors. In addition, rehabilitation can be markedly improved when the patient is transferred to a more recuperative setting where technology is available (e.g. peripherally inserted central lines) for a safer and more manageable recovery. This has resulted in community nurses being involved in more specialised kinds of care as well as significantly earlier patient discharge from hospital.

Today, all over the Western world nurses are providing patient care in a wide variety of healthcare settings outside hospitals. An emphasis on chronic disease management has provided a greater role for community nurses in health promotion and patient education in areas such as respiratory and heart disease and diabetes management. Meanwhile, in developing countries, as well as in developed nations, nurses continue to maintain a role in primary healthcare in the community through immunisation and other illness prevention or health promotion programs.

Consistent with the trend for patient care outside of hospitals it is now expected that an increasing amount of nursing care will be provided in the community. This trend is set to continue in Australia as people are living longer and need to manage disability and chronic diseases.4 Australia and New Zealand are shifting healthcare services back into the community and this will require even more nurses to work in community care. Community nurses themselves have been very active in the development of innovative models of care that have been successful in avoiding hospitalisation, particularly for older people.5

Community-based nursing practice can be defined as the care of individuals and families throughout the life span. Its goal is to help individuals and families to manage their health in community and home settings. Community-based nurses may be referred to as domiciliary nurses, community nurses, nurse practitioners, general practice nurses, remote area nurses, public health nurses, district nurses and community health nurses. There is considerable overlap between some of these community-based nursing categories due to the increasing diversity in methods of care delivery, and an attempt to distinguish them could lead to an inaccurate or incomplete description of their roles. The one constant thread is that they all work outside the confines of a hospital and deliver care in a range of community settings using a variety of means, including assessment, direct care delivery, consultation, case management, education, health promotion and illness prevention programs. Community-based nursing can also involve acute care, such as in Hospital in the Home programs. Community-based nursing has as its primary focus the healthcare of individuals, families and groups within the community, whereas at the other end of the spectrum public health nursing focuses on the healthcare of the community. Generally speaking, community-based nursing is about the promotion of wellness and quality of life in the community, including those who are at the end of life and in need of palliative care.1

Factors influencing change in the healthcare system

SOCIOECONOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

Nursing care in the community is provided by public, private and not-for-profit organisations that are funded in a variety of ways and administered by both Commonwealth and state governments in Australia and by District Health Boards, religious organisations and other non-government organisations in New Zealand.

Medicare is the predominant source of funds available for healthcare in Australia and is distributed by the Commonwealth government to the states under the Medicare Agreements 1988 and the Medicare Act 1999 (Cwlth). Medicare, introduced into Australia in 1984, is a universal health insurance scheme whereby all those who earn above the minimum taxable income pay a proportionate levy to the government as part of their taxes. This levy is increased after income reaches a specified point so that those over a certain level of income pay a larger proportion of the levy. At present, Medicare provides access to free or subsidised treatment by general practitioners and other providers of healthcare, such as specialist doctors and surgeons. It also provides free public treatment in public hospitals. Medicare funds community-based nursing services that are supplied by hospitals and also general practice nursing services through specific items available on the Medical Benefits Scheme. Information about Medicare is available online (see the Resources on p 104).

In New Zealand, public community health services are funded by the Ministry of Health through District Health Boards, which act as the ‘purchasers’ of services. The legislation under which the system operates is set out in the New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act 2000. The ‘providers’ of services sign a contract with the District Health Board. The main providers are known as Primary Health Organisations (PHOs), although District Health Boards also provide some services, such as district nursing and hospice care. The PHOs were set up under the New Zealand primary healthcare strategy in 2001,6 primarily to provide comprehensive, culturally appropriate services at an affordable price to all New Zealanders. Some primary healthcare services are provided by non-government organisations, which also contract with the District Health Boards—for example, The Royal New Zealand Plunket Society, Nurse Maude Association and Salvation Army Home Care Services.

To enable the New Zealand government’s health targets to be achieved, the Ministry of Health also provides some targeted funding in areas of public health concern (e.g. diabetes, heart disease, obesity and destigmatisation of mental illness). The Ministry of Health is required by the government to improve access to primary healthcare services for people on low incomes and with high health needs. An example is the Services to Improve Access (SIA) funding, which is available to PHOs and other providers, and the Care Plus scheme, which funds initiatives for people with complex health demands. Public health nurses in New Zealand also work in the area of health promotion and health protection. A major immunisation campaign against meningococcal B disease (the MeNZB program), which attempted to immunise every child and young person under the age of 20 in New Zealand, was a good example of this type of nursing work.7 Further information about the work of the Ministry of Health and its policies and projects can be found online (see the Resources on p 104).

In Australia, the most notable event related to changing public hospital reimbursement was the institution of case payments and the use of Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs; now superseded by Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups [AR-DRGs]) as part of the Medicare Agreements 1988.8 Funding for all public hospitals in Australia is allocated per admission based on a case mix classification. The best known case mix classification is the AR-DRG. In many instances the implementation of AR-DRGs has shifted patient care from acute care settings to community settings through a process of early discharge to home care. This is because hospitals can reduce the costs of healthcare delivery by providing a quality service in the patient’s own home. Case mix funding has been and continues to be one of the most significant factors affecting healthcare. In contrast to the Australian model of healthcare funding, New Zealand operates on a population-based funding model for health services.

In both New Zealand and Australia patients have access to private health cover through insurance options if they wish to pay an insurance premium, although the manner in which the insurance schemes operate is different. In New Zealand, all public hospital services are free and private insurance reimburses part of the cost of private care. An insurance company can refuse to enrol clients if they appear to be poor insurance risks (i.e. have high health needs). Insurance does not provide for rehabilitation or long-term mental health services. Private insurance premiums are not tax deductible under New Zealand legislation.

In contrast, the Australian government offers a tax rebate on the premiums paid to those who take out private health insurance cover in an effort to encourage people to utilise the private health system and reduce pressure on the public health sector. Insurance companies pay private hospitals for services on a per diem basis or in Episodic Case-Based Payments. The latter allows hospitals to find cost-effective ways of providing services in the community, as the insurance company pays a set fee for the duration of a patient’s hospital stay. In situations where insurance companies’ preferred providers engage in this type of managed care, charges are negotiated in advance of the delivery of care by the health insurance companies and private agencies or hospitals through contracts using predetermined reimbursement rates or capitation fees for medical care, hospitalisation and other healthcare services. These contracts are regulated under the Health Insurance Act 2000. Like Medicare, this form of contracting has caused a shift in the delivery of care from acute care hospital settings to less expensive community settings.

The US system of managed care has been available to Americans since the 1970s and is characterised by Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) controlled by insurers. This system evolved as a means of offering cost-effective healthcare delivery.9 The HMO contracts with healthcare professionals and facilities to provide the specified care for a negotiated fixed sum of money paid in advance for a specified period of time. Generally, a client cannot seek care outside the healthcare provider and/or hospitals under contract with the HMO. In managed care systems, capitation fees for medical care, hospitalisation and other healthcare services are based on competitive market forces. Consistent with the market-driven philosophy of managed care, HMOs have also caused a shift in the delivery of care from the acute care hospital setting to less expensive community settings.

While the New Zealand and Australian healthcare systems have both become more corporate over time, with more funding decisions being made by administrators rather than health professionals, policy makers have, from time to time, mooted the idea of introducing managed care to the public system, but this has not transpired to a significant extent. To transpose the US system onto the Australian system would take a high degree of state and Commonwealth cooperation. There are also concerns that managed care is profit driven, so that those most in need of services may have the least access to quality care. In the US, large numbers of people are denied care by HMOs and there are doubts as to whether managed care organisations set fair and equitable capitation rates.10

In Australia and New Zealand, government policies and recent advances in technology have resulted in nurses caring for increasingly complex clients in community and home settings, while new opportunities are developing for nurses to take an increasing role in the provision of community healthcare. The development of the nurse practitioner scope of practice is one example whereby government policy and professional leadership by the nursing discipline have come together to develop a new role and career path for nurses working in community and hospital-based settings.11,12

Due to the large and diverse range of funding sources and contracted services in community-based nursing care, Australian governments are now calling for collaboration and partnership approaches in order to streamline services and avoid gaps and duplication. This was given priority at the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) in February 2006 and presented in government discussion papers, such as the Commonwealth government’s A new strategy for community care: the way forward 2004 and the Queensland government’s Smart state: health 2020—a vision for the future. Evidence of collaboration on a large scale has occurred in Victoria’s Primary Care Partnerships (PCPs), whereby more than 800 community-based service providers, including general practitioners, non-government and government organisations have formed partnerships in 32 PCPs across Victoria to improve the coordination and communication required to deliver high-quality and efficient patient care.13

CHANGING DEMOGRAPHICS

The average age of people in Australia and New Zealand is increasing. The rate of growth in the number of Australians and New Zealanders aged over 65 is increasing more rapidly than that of the general population, and centenarians (people aged over 100 years) are also a fast-growing population group.14,15 As a result, healthcare needs and demands are changing. It is predicted that our ageing populations will demand more healthcare and financial resources, such as Medicare, to fund their health and care as they age. It is not that our population has never aged before, but the proportions of people over the ages of 65 and 85 are increasing, while the nursing workforce is shrinking proportionally.16 Older people are more likely to have complex medical and healthcare needs, including multiple chronic conditions that may compromise their ability to remain independent without supportive community or professional help. Physical and functional problems, dementia, fixed incomes and limited family or community support can put older people at an increased need for social and healthcare assistance.

NATURE AND PREVALENCE OF ILLNESS

The expanded life expectancy of the population and lifestyle factors are contributing to increases in the number, severity and duration of chronic conditions. Many chronic diseases are, in large part, related to lifestyle behaviours. Tobacco use, alcohol misuse, lack of physical activity and poor nutrition (including obesity) are major contributors to many of Australia’s identified health priority areas (e.g. cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, diabetes mellitus and cancer). Chronic diseases affect at least one in four Australians, and cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and depression are considered endemic.14 The health status of New Zealanders is similar, and is reflected in the health priorities set by the New Zealand government.17

As a result, the focus of healthcare is shifting away from intervention in the acute phase of disease towards early screening, detection and prevention. Nursing practice directed towards the prevention and management of chronic illness occurs in community-based settings through: (1) promoting regular screening and use of positive health behaviours; and (2) assisting individuals and families to manage chronic illness in the home. Chronic disease self-management is becoming a more prevalent strategy for community nurses in many areas where there is a high degree of chronic illness, and it is comprised of either disease-specific or generic client-centred approaches to self-management support.18

TECHNOLOGY

Surgical innovations (e.g. advances in cardiac surgery and laparoscopic techniques) and medical interventions (e.g. new drugs for cystic fibrosis and human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]) are enabling individuals to live longer, shifting both acute and long-term care to community-based settings and the home. New technology is improving diagnostic procedures and the management of client care. Computers, lifesaving drugs and tele-health interventions are simplifying diagnosis and treatment and shortening hospital stays.19

Client care has moved to settings, such as surgical centres, which provide services traditionally delivered only in hospitals. Complex client care treatments, such as intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy and total parenteral therapy, are increasingly being delivered in the home. Evolving technology, the focus on reducing rapidly increasing healthcare costs and client preference to be at home have stimulated the movement to provide healthcare in the community and home settings.

Australian state and Commonwealth governments and the New Zealand Ministry of Health are starting to explore common databases for holding and maintaining patient information as a way of improving communication between the large range of healthcare professionals who can be involved in the patient’s care over a continuum in both community and hospital settings. Australia has been attempting to introduce a personal E health record for the past decade.20 New Zealand’s developments follow the Health Information Strategy for New Zealand 2005 (see the Resources on p 104). Issues such as patient privacy, confidentiality, consent and ownership of information are still being discussed to ensure access to patient information is secure while providing the most effective means of information sharing between healthcare professionals. Such a system would offer the advantage of reducing numbers of patient assessments and improving the availability of more accurate information, such as medication therapy for general practitioners, pharmacists and community nurses. This would be particularly useful when a patient is discharged from hospital and commenced on multiple new medications, as there is a positive correlation between polypharmacy and adverse health outcomes for older people. A lack of effective communication between hospital and community-based healthcare providers can compound this problem.

Community nurses also utilise technology in their delivery of nursing care. For example, they may carry hand-held communication devices no bigger than a mobile phone that give them access to all organisational policies and procedures, schedules and client information and enable them to be connected to the organisation no matter where they are.19 They also use similar equipment to that used in the hospital setting during their delivery of nursing care.

INCREASING CONSUMERISM

Healthcare is becoming more consumer-focused and people are becoming increasingly involved in their own healthcare.16 Many people eagerly seek out information about their health from the media and internet sources. They also expect that information will be provided so that they may collaborate with healthcare providers in making the right decisions about their healthcare. In addition, the public has come to recognise healthcare as an entitlement or a fundamental human right. Universal healthcare in Australia underscores equal access to healthcare services, regardless of ability to pay. This notion of equality is particularly important when it comes to people who are culturally and linguistically diverse. To ensure that people from minority groups gain access to mainstream services, many community-based nursing services deliver programs specifically targeted towards the needs of traditionally marginalised groups and those with the highest health needs. The provision of culturally competent care is a standard that all members of the community can expect from their nurses (see Ch 2).

Australian state and Commonwealth government funding bodies and the New Zealand Ministry of Health each have quality standards and expectations with which providers of community-based services are compelled to comply. Auditing and performance review occur as a routine part of these accreditation processes. Organisations are also encouraged to carry out client satisfaction surveys to monitor and improve service delivery to clients who are receivers of community-based nursing care and to identify gaps in service areas. As increasing demands are made on resources, community nurses are also becoming more active partners with clients in promoting wellness through education and advocacy and in negotiating care with clients and their carers, family and extended family.

Community-based nursing

CONTINUUM OF CARE

Depending on the individual’s health status and the care required, clients can move among different healthcare settings. There is a continuum of care whereby different settings accommodate the varying needs of the client. Within this continuum, many people today are cared for in community-based settings. For example, a patient may be hospitalised in a trauma unit following a motor vehicle accident. After she is stabilised, she may be transferred to a general medical–surgical unit and then to an acute rehabilitation facility. After a period of rehabilitation, she may be discharged home to continue with rehabilitation. In Australia, such ongoing rehabilitation will be provided by community nurses from a non-government organisation funded by Home and Community Care (HACC).21 In New Zealand, the funding for such ongoing rehabilitative care will very likely fall under the Accident Compensation Corporation’s accident compensation scheme, which provides personal injury cover for all New Zealand citizens, residents and temporary visitors.

The continuum of care does not always include hospitalisation. Most clients receive community-based care without experiencing an acute problem requiring hospitalisation. Health problems may be identified in a variety of clinic settings or in the client’s own home. In addition, individuals or families may seek specific assistance from healthcare resources in the community. For example, a client may be screened for diabetes mellitus in a community-based screening program and, when indicated, referred to a clinic where a diagnosis of diabetes can be established. A community-based diabetes clinical nurse specialist may function as a case manager to coordinate the diabetes management team, consisting of diabetes educators, nurses, dieticians, pharmacists, specialist consultants, general practitioners and other healthcare professionals. Services may include care and education in a variety of settings, as well as follow-up by generalist community nurses. This can be facilitated by documentation, such as best practice guidelines, and clinical pathways so that the continuum of care remains intact.

COMMUNITY NURSES

Nurses practising in community settings provide direct care for acutely or chronically ill people where they reside, work or go to school.22 They also case manage people who are not unwell but who may be in need of support services from multiple different service providers. For example, disability nurse specialists visit people with intellectual disabilities at home and coordinate their service needs so that they can maintain independence in their own home. Nursing roles include district or domiciliary nurses, school nurses, occupational health and safety nurses (see Fig 6-1), community health nurses, community mental health nurses and nurses working in outpatient clinics, general practice and day-care centres. Nurses in nurse-managed clinics provide direct care to patients in a day-care setting. Nurses working in the community complement each other’s work and the work of other healthcare workers, acting as a liaison with nursing services and other community welfare and health resources.

CASE MANAGEMENT

Case management or care management is an approach used to coordinate and link healthcare services to clients and their families in the changing healthcare environment. This is a common approach in Australia, New Zealand and the US. Although healthcare agencies or organisations may define and practise case management in various ways, the concept of case management involves coordination throughout the entire period of care across every setting where the client receives care.23 The goals of case management are to provide quality care along a continuum, decrease fragmentation of care across many settings, enhance the client’s quality of life and contain costs.

Case managers are an extremely important part of managed care, community-based nursing and home healthcare. The case manager assesses the client’s needs, establishes a plan of care with the client and family, coordinates multidisciplinary teams, updates the client and family on the progress of care, and facilitates selection of appropriate healthcare resources. For example, a client with severe coronary artery disease may be assigned a nurse as a case manager in a clinic setting. When the client is hospitalised for coronary bypass surgery, the same case manager coordinates care so that all healthcare providers understand the client’s unique needs. When the client is discharged, the case manager, in consultation with the medical and allied healthcare team, determines whether home nursing or other services are necessary for the client. If the latter are chosen, the case manager may visit the client in other settings to follow up on the healthcare measures that have been implemented.

Case management is a significant part of community nurses’ work for clients with complex care needs who need to be linked with multiple service providers—for example, in the areas of drug and alcohol rehabilitation and mental health, and in the care and support of people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness.

Community care settings

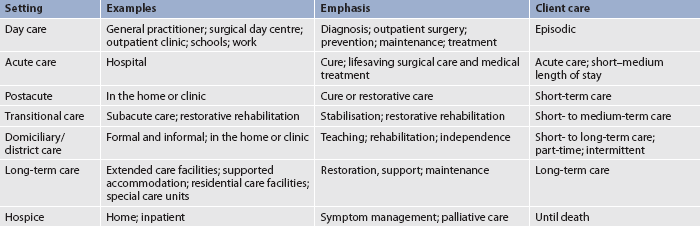

The following sections provide an overview of selected community care settings where community-based nursing is provided. A key factor in community-based nursing is the environment. Nurses in community settings are autonomous practitioners who often deliver care in the client’s own home. This is empowering for the client rather than dehumanising, as may be the case in hospital settings, because the nurse attends to the client’s individualised care needs as a guest in the client’s home.19 The environment for community nurses may be complex from a workplace health perspective as they may be entering territory that they are unfamiliar with after dark and in isolated areas. Community nurses therefore need well-honed assessment skills. Table 6-1 compares a variety of care settings.

In the past 20 years there has been an explosive growth in community-based nursing and other home healthcare services, coupled with a steady decline in hospital bed numbers and length of hospital stay. The growth in community-based care has been stimulated by AR-DRGs, shortened lengths of stay in hospital even for those clients with complex health conditions and client preferences to be cared for at home. Community-based care is one of the most rapidly growing segments in healthcare today, with the primary motivation being cited as the requirement to shift healthcare to less costly alternatives and provide better health outcomes for people.

DAY CARE

Day-care settings include general practitioner and nurse practitioner offices, emergency departments, community health centres, surgical centres, schools, employee health clinics, adult day-care centres and a multitude of public and private clinics serving general or specific populations. Nurse-managed clinics, such as wound clinics provided by district/domiciliary nursing services, are also proliferating. An innovative variation on this is the Leg Club model, where clients receive the social benefit of interacting with other clients at the same time as wound healing.24

Nurses in day-care settings may assist a doctor in their practice (e.g. as a general practice nurse) or, with additional training, assume a nurse practitioner or other advanced practice role. Nurses in day-care settings assess clients’ problems, evaluate the need for resources and information, and provide the appropriate interventions that allow clients to care for themselves. Client teaching and telephone follow-up are routine practices in ambulatory care settings. Nurses in surgical centres may assist with the preoperative and postoperative care for clients who will be discharged home the same day.

TRANSITIONAL CARE

Transitional care or interim care is a growing form of care delivery in both Australia and New Zealand and refers to the intermediary care between the acute care setting and the home, where home may include a residential care facility. Clients who have recently been admitted to the acute hospital but who cannot care for themselves may be placed temporarily in a transitional care setting. Transitional care may take place in a distinct part of a hospital, in a long-term care facility or in the home. If transitional care is successful at home, then the client may choose to stay at home or opt for placement in a low- or high-care residential care facility as determined by their healthcare needs. Many District Health Boards in New Zealand are developing models of transitional care, while in Australia the Commonwealth government has recently funded new Transitional Care programs for the express purpose of providing care options in the place that is most appropriate for the client’s recovery.

An example of transitional care is subacute care. Subacute care is postacute care designed for clients who need a greater intensity of care than that generally provided in a long-term care facility but who no longer require acute care. Typically, those people requiring subacute care may be chronically ill, require palliative care or rehabilitation, be ventilator-dependent or need specialised monitoring, equipment and nursing care. Many people who require subacute care may move to rehabilitation or extended care wards where their needs can be better met by specialised healthcare workers with access to specialised equipment. In New Zealand, some private hospitals are designed specifically for the care of older people requiring transitional care—that is, restorative care post-hospitalisation. Restorative care is particularly important for older people who may have de-conditioned and become frail and weak during an extended hospital stay. Nurses working in subacute care need to be familiar with tracheostomy care, ventilators, complex wound management and care of people at the end of life. Although clients requiring this type of care are usually medically stable, they require multiple and complex treatments. Short-term acute care is designed to return the client to the community or transition the client to a lower level of care.

LONG-TERM CARE

Long-term care can include extended care or slow-stream rehabilitation units, residential care and special care units that are often placed within large retirement communities. Long-term care may be necessary when a person is no longer able to live independently. Residential care may be the most suitable option for people who have severe developmental disabilities, are cognitively impaired or who have physical disabilities requiring continuous medical or nursing management. This may include people who are in need of long-term rehabilitation, have a condition from which there are enduring effects (such as a mental illness) or who have a condition that will lead to greater levels of dependency as the condition progresses (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease). The term resident is usually used to refer to people who live in residential care facilities. (See Ch 5 for information on the care of older adults and residential care facilities.)

In Australia and New Zealand, nurses employed in extended care units, special care units and residential care tend not to be categorised as community nurses, essentially due to prevailing differences in funding arrangements between the residential and community sectors. However, there is an important role for community nurses in liaising with residential care nurses when the client is taking the sometimes difficult step towards leaving their own home and entering residential care.

Retirement communities

Retirement communities or villages have grown rapidly in New Zealand and Australia over the last two decades. Some retirement communities provide a range of options, including housing complexes, independent living units, serviced apartments and residential care (low care, high care or a mixture of both). Some provide the whole continuum of independent housing, services, supported care, residential care and healthcare. There is usually a written agreement or contract between the resident and the retirement village that is generally intended to last the resident’s lifetime or for a specific period of time. Community nurses provide care to people in independent living units as the need arises.

Supported accommodation

Supported accommodation provides community-based housing for people who require ongoing support and accommodation. Individuals may live in hostels or in community group houses and obtain additional assistance with their activities of daily living (ADLs), such as grooming and meal preparation, or supervision with their medications and other healthcare needs. Group housing for people with intellectual disabilities arose out of a deinstitutionalisation process that occurred in Australia and in New Zealand in the 1980s. Disability nurse specialists (see Fig 6-2) in the community aim to improve the individual’s enjoyment of life and maximise their potential by offering case management and support to people who live in group homes as well as their families. Many people who live in group homes are linked with other facilities that provide day programs, social support and programs to improve quality of life. Hostels and community group houses are funded in Australia through the Commonwealth government, state governments and non-government organisations, combining to provide social, psychological and healthcare needs. In New Zealand, funding is provided through the Ministry of Health via the District Health Boards, or non-government organisations, often in partnership with local councils.

Figure 6-2 Disability nurse specialists work in group housing contexts for people with disabilities.

Supported accommodation is also available in the community for people with severe and disabling effects of mental illness, such as those living with schizophrenia. The move to more adequate support in the community through HACC funding and community mental health programs has been brought about as a result of the 1993 Burdekin Report into the human rights of the severely mentally ill.25 This report provided the impetus for the Australian Health Ministers’ National Mental Health Plans (1 and 2) and the National Mental Health Strategy and led to the deinstitutionalisation of the mentally ill.26,27 Developments in New Zealand were similar to those in Australia, although the specifics of funding are a little different. The national inquiry that sparked many of the changes in mental health services in New Zealand was the Mason Report in 1988,28 later followed by the second Mason Report in 1996.29 Some consider that progress in improving the care and environments of supported accommodation has been slow.

There is a significant role for community nurses, such as disability nurse specialists and mental health nurses, as well as generalist community nurses, in caring for people in supported accommodation.

DOMICILIARY/DISTRICT NURSING

Domiciliary/district nursing refers to community-based nursing delivered in the home or clinic setting. People may define ‘home’ in a number of different ways but it generally refers to where the client lives and is not restricted to a house as it may be a caravan, an independent living unit, supported accommodation or other dwelling. Domiciliary/district nursing services may include postacute care such as wound care or administration of intravenous antibiotics, health maintenance, education, illness prevention, diagnosis and treatment of disease, palliative care and rehabilitation. Clients may require intermittent services or full-time care.

Funding for care in the community in Australia is derived from a number of sources. The HACC program is the main funding source for home-based health and care (particularly for people aged over 65 years or those with disability) and contributes funding to government and non-government care providers, such as domiciliary/district nursing services. Some of the largest and oldest community nursing services in Australia are Silverchain in Western Australia, the Royal District Nursing Service (RDNS) in Victoria, the RDNS in South Australia and Blue Care in Queensland. Each of these organisations provides services with HACC funding, including home nursing, personal care, respite, domestic help, meals and transport. Other funding comes from the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (reflecting the care needs of veterans of military service and war widows) and state governments, which may provide funding for postacute services in the community. Most agencies charge a small fee for service, which is based on an assessment of the individual’s ability to pay. In addition, the government funds other services to assist people with more extensive care needs. These include Community Aged Care Packages (CACPs), which support older people who prefer to remain at home but who would normally require low-level residential care; Extended Aged Care at Home (EACH) packages, which support older people who prefer to remain at home but who would normally require high-level residential care; and Extended Aged Care at Home packages for people with dementia (EACH-D).

New Zealand’s funding structure is different from that of Australia. As mentioned earlier, district nursing services are provided through each of the 21 District Health Boards, which also offer contracts to the providers of most other home-based services.

Domiciliary/district nursing has been in existence for a very long time. In fact, until hospitals became the predominant source of healthcare, nurses often made visits to clients’ homes to teach and provide care. In the US, it was not until the mid-1960s that home nursing became established, but in Australia and New Zealand home nursing has been provided by nurses and midwives working in the community since the late 19th century. The first District Nursing Service in Australia was established in Melbourne in 1884, followed by the other states during the rest of the century. New Zealand’s first community (district) nursing program began at the end of the 19th century in Christchurch by Nurse Maude (Sybylla Emily Maude), and an association still bears her name today.

Domiciliary/district nurses may have generalist or specialist roles and sometimes these roles overlap with those of community health nurses who generally work for government services in community development projects, health promotional work and counselling roles. Community health nurses also care for people with mental health problems. More recently, domiciliary/district nursing services have been augmented by outreach services from acute care hospitals and surgical clinics, and nursing services provided by private agencies. The overlap in roles between district, community health and hospital outreach nurses is becoming less distinct as organisations are diversifying to meet community needs.

NURSING CARE OF THE HOMELESS

Increasing numbers of people are living in homeless situations or are at risk of homelessness in Australia and New Zealand. A number of community-based support services are available for people who are homeless, including nursing services for people with acute or chronic care needs. Community nurses who work with people who are homeless may do so from a clinic or provide an outreach service into the parklands or other areas where people who are homeless are located. Nurses working with people who are homeless have strong collaborative links with extended community support services, such as general practitioners, social workers, mental health, drug and alcohol and family services. Nurses working with homeless youth also actively collaborate with youth workers. There are a number of resources available to assist nurses working in this field and some of these are listed in the Resources section on p 104.

RURAL AND REMOTE SETTINGS

Rural and remote area nursing is a specialised field of community-based nursing in Australia and one that involves advanced clinical practice and a diverse range of skills—such as emergency care, palliative care and chronic disease management—as well as knowledge of Indigenous health issues. Rural nurses in New Zealand also deal with a wide range of health issues. In many instances these nurses are isolated, independent practitioners who rely on communication and technology to keep in touch with medical services that can often be many hundreds of kilometres away. Rural and remote area nurses may be clinic-based or they may travel vast distances to provide care and support to isolated rural communities. Chapter 11 discusses the complexities of rural and remote nursing in the Australian and New Zealand contexts.

Service providers of community-based nursing care in Australia and New Zealand continue to lobby for increased funding to keep pace with growing demand. Increasingly, community nurses are working with personal care assistants to provide many home healthcare services. In these instances, registered nurses are the coordinators of client care and are accountable for nursing care, the supervision of personal care services by care assistants and case management services. This adds an element of complexity to the notion of supervision when the care assistant in many cases is also working on their own in the community and relying on direction from the nurse in the form of documentation such as care plans.

Client care

In an effort to streamline access to community services the Australian government has been encouraging the use of common screening and assessment tools.30 For many community organisations, screening occurs at referral, whereas a comprehensive and/or specialist assessment is carried out when the client is visited. An assessment of the environment is also carried out for workplace health and safety purposes and can incorporate an after-dark risk assessment, for example when it is anticipated that the client will be receiving visits from palliative care nurses at night. Nurses working in the community must have advanced assessment skills to holistically assess the client with multiple healthcare needs. Assessment and review occur routinely throughout the client’s period of care with the agency.

Common reasons for clients to be referred to a district, domiciliary or community-based nursing service include: wound management (see Fig 6-3); medication management, including insulin administration; assisting schoolchildren with regular asthma medications during the school day; topical medications following eye surgery; and analgesia for palliative care. Some of these nursing services have a strong palliative care focus and usually employ clinical nurse consultants to provide a range of palliative care services to clients, carers and other staff.

Treatments commonly performed in the home also include administration of infusion therapy (i.e. antibiotic administration), patient-controlled analgesia for pain control, enteric feedings, parenteral nutrition, chemotherapy and hydration therapy (see Box 6-1). The nurse and a rehabilitation team member may also provide medical equipment in the home to facilitate medical treatment and safety. This may include electric beds, wheelchairs, commodes, walkers and other assistive devices.

BOX 6-1 Examples of domiciliary healthcare nursing activities

Assessment

Performance of in-depth holistic assessment of the client, family and home environment. Assessment of community services as a source of referral for client/carer needs. Ongoing evaluation of the client’s progress.

Wound care

Dressing changes. Observation, assessment and culture of wounds. Debridement and irrigation of wounds. Instructing the client and family in wound care.

Respiratory care

Management of oxygen therapy, mechanical ventilation, chest physiotherapy. Suctioning and care of tracheostomies.

Vital signs

Monitoring blood pressure and cardiopulmonary status. Teaching the client and family to take blood pressure and pulse.

Elimination

Assistance with colostomy irrigation and skin care procedures. Insertion of urinary catheters, irrigation and observation for infection. Instructing the family in intermittent catheterisation. Insertion, replacement and sterile irrigation of urethral and suprapubic catheters. Bowel and bladder training.

Nutrition

Assessment of nutrition and hydration status. Teaching about prescribed diet. Administration of nasogastric and percutaneous tube feedings, including gastrostomy and jejunostomy tubes, and teaching the family about tube feedings. Placement and replacement of tubes and ongoing management and evaluation.

Rehabilitation

Teaching the client and family to use assistive devices, range-of-motion exercises, ambulation and transfer techniques.

Medications

Teaching the client and family about the administration and side effects of medications. Monitoring compliance and effectiveness of prescribed drugs. Administration of and teaching about insulin injections.

Intravenous therapy

Assessment and management of dehydration. Giving antibiotic drugs, parenteral nutrition, blood products, and analgesic and chemotherapeutic agents. Use of peripheral and central lines.

Clients have benefited from sophisticated technology in the home care setting. The miniaturisation of infusion pumps makes it possible for clients to go to work while receiving antibiotics or total parenteral nutrition. The use of central venous catheter devices and peripherally inserted central catheters has eliminated many problems associated with short-term and less reliable IV therapy. Table-top ventilators allow clients who are dependent on mechanical ventilation to be cared for in the home setting, enabling even greater mobility when the equipment is strapped to the back of a wheelchair. Oxygen delivery in a variety of forms is also frequently provided in the home for clients requiring respiratory support (see Ch 28).

Care in the community is now the ‘norm’ for mental health patients in Australia and New Zealand, with an increasing emphasis on integrated health promotion and preventative care (particularly in rural and remote areas). Community mental health nurses provide therapeutic care (in conjunction with the multidisciplinary team) for acute and long-term care clients wherever they live. The aim is to provide care for clients in the community except when intensive care and protective care are required in an inpatient setting. Many mental health clients now receive their entire therapeutic care (e.g. supportive groups, medication, counselling, rehabilitation) in the community through day programs, visits from nurses and other members of the mental health team, and social support from HACC workers. Non-government organisations and consumer support groups also provide care, drop-in facilities and information for mental health clients to ensure that community care is sustained. Mental health nurses may also assist clients to find employment, housing and financial assistance.

Concerns of clients requiring home healthcare are presented in Box 6-2, and examples of nursing diagnoses for clients requiring home healthcare are presented in Box 6-3. Although the client in the community is the centre of care and visit reimbursement is based on what is done for the client, nursing care in the home must also be family centred. An illness experienced by one family member or carer will affect the entire family/extended family and alter family interactions. Families often provide care for family members who are unwell or frail or who have disabilities, and they assist in decision making about the type and extent of care provided.

BOX 6-2 Concerns of clients requiring home healthcare organised by functional health patterns

Source: Adapted from Crisp J, Taylor C. Potter and Perry’s fundamentals of nursing. 3rd edn. Sydney: Elsevier; 2009.

BOX 6-3 Clients requiring home healthcare*

NURSING DIAGNOSES

Acute pain related to the disease process, therapy, decreased joint mobility

Carer role strain related to assuming total care of the client

Chronic pain related to chronic physical/psychosocial disability

Constipation related to decreased fluid intake, lack of mobility, opioid analgesics

Deficient fluid volume related to inadequate nutrition and hydration, dysphasia and confusion

Fatigue related to the disease process and therapy

Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements related to inability to ingest or digest food, inability to absorb nutrients

Impaired home maintenance related to decreased mobility, decreased endurance

Impaired skin integrity related to physical immobility, radiation, pressure

Risk of aspiration related to enteral tube feedings, impaired gag reflex or swallowing, inability to expectorate sputum

Risk of infection related to inadequate primary or secondary defences, impaired immune status, malnutrition

Risk of injury related to altered mobility, confusion, fatigue

Self-care deficit (any combination of the following): bathing/hygiene, dressing/grooming, feeding or toileting related to pain, musculoskeletal impairment, decreased endurance

Social isolation related to physical immobility, alteration in physical appearance

*The nursing diagnoses in this table are examples of possible nursing diagnoses for a client receiving home healthcare.

Care provided by healthcare professionals is usually episodic, leaving the family with the burden of care day in, day out. In some situations, an older client may be cared for by a spouse of similar age with chronic illnesses. In other situations, an older parent needing care may live with a busy middle-aged son or daughter with dependent children. In any home care situation it is common for carers to become physically, emotionally and economically overwhelmed with the responsibilities and demands of caring for a family member. The community nurse needs to help family members to understand and cope with changing roles, responsibilities and stresses. Referral to various support groups in the community or on the internet is one way the nurse can help family members to cope with the experience of providing home care. Community nurses can also assist to arrange short-term respite in a residential care facility for the client in order to provide much-needed rest for the carer.

Teaching needs to involve both the client and the family/extended family. Family members who are providing care should learn how to administer treatments and manage equipment. For example, diet modification is a cornerstone of diabetes management. Although the client may be an older diabetic, the client’s spouse or daughter may do the grocery shopping and cooking. Dietary teaching that does not include the family/extended family may not be as successful. The community nurse should provide education that is supported with clear and accurate documentation to assist safe and appropriate sharing of care with the client and their carer.

Nursing in the home involves a very different set of dynamics from that of care provided in the hospital. In the hospital setting, the healthcare team has the dominant role and the environment is controlled. In the home, the family and/or the client play the dominant role, and the nurse is a visitor in the healthcare setting.31 Community-based nursing is delivered within the context of the family’s cultural values and beliefs. In the home, the nurse is more likely to encounter the client’s use of healing practices arising from cultural beliefs and the use of home remedies and complementary and alternative therapies. The community nurse must be respectful of cultural practices and knowledgeable about alternative therapies to guide the client and family in their safe and effective use. (Culture is discussed in Ch 2 and complementary and alternative therapies are discussed in Ch 7.)

Clients visited by domiciliary/district nurses are most often discharged from hospital settings. However, they may also be referred directly from a medical practitioner, or the client or carer may request the service themselves. Depending on the needs of the client, community-based nursing visits may be as frequent as twice daily or as infrequent as once a month. Visits may be extensive and require significant time, such as the initial assessment visit, or they may be shorter in length, such as visits to review a healing wound. Visits may be characterised by a predetermined routine or treatment regimen, such as insulin administration and blood glucose monitoring or wound care.

HOME HEALTHCARE TEAM

The home healthcare team has many members—the client, family, nurses, general practitioner, specialist consultant, social worker, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, speech therapist, care assistant, pharmacist, podiatrist and dietician. Nursing care is one of the primary services in the home setting (see Fig 6-4).

Physical conditions or diagnoses that may trigger a referral to a physiotherapist include orthopaedic conditions, such as hip or knee surgeries, or neuromuscular deterioration commonly seen with multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and stroke. The physiotherapist will work with clients on strengthening and endurance, gait training, transfer training and developing a client education program. Occupational therapists may assist the client with fine motor coordination, performance of ADLs, cognitive perceptual skills, sensory testing and the construction or use of assistive or adaptive equipment. Podiatrists can help clients with diabetes (and their families) to care for their feet, advise about suitable footwear, and assess and help lessen the risk of falls for clients who have difficulties with balance or ambulation. Speech therapists focus on various speech pathologies for those who have suffered speech or swallowing disorders, which are seen with stroke, laryngectomy or progressive neuromuscular diseases. The social worker assists clients with coping skills, carer concerns, securing adequate financial resources or housing assistance, or making referrals to social service or volunteer agencies. Personal care assistants assist clients with their personal care needs, such as bathing, dressing, hair washing or homemaking activities like meal preparation or light housekeeping.

Other members of the home healthcare team may include pharmacists, who are involved in the preparation of infusion products, and dieticians for dietary consultation. The members of the home healthcare team work collaboratively with the community-based nurse to plan and evaluate the client’s progress on a regular basis, with a significant emphasis placed on home education programs.

Community-based nursing skills and attributes

Community nurses must have expert organisational skills, be able to make independent decisions and know how to set priorities and respond to problems promptly. They must adapt to a variety of circumstances that challenge their assessment, planning and intervention abilities. For example, the nurse may need to modify the technique for dressing changes for a client with limited manual dexterity and no running water in his home. Nurses who work in the community require additional skills in time and case management, communication, assessment and diagnosis, community resource identification, teaching and discharge planning. Attributes of community nurses include flexibility, empathy, client advocacy and the ability to function independently in a diverse range of settings. Nurses need to balance administrative and agency demands and productivity standards with client care needs.

Documentation is the key to continuing services in the client’s home. Provision of sufficient support services requires excellent assessment and communication of these requirements to the variety of health and care agencies in the community. Nurses must use concise and accurate documentation to ensure both legal and professional accountability. Documentation is the only way to substantiate recommendations about the client’s needs, the care provided and the client’s response. These are all necessary to ensure meeting the criteria for the services rendered.

The use of computerised client records in home care is a growing trend. Some community nurses document care as it is delivered using laptop or hand-held computers. If computer records are fully integrated, the client record can be retrieved by modem at many different sites. The record is accessible to the nurse and others at the client’s home, nurse’s office, doctor’s office and hospital. In the client’s home the nurse can review the client’s history and plan of care and update the record as care is given. The accessibility of computerised records leads to better continuity of care and reduced documentation time. It also helps create a database for developing protocols for treating specific outcomes and the use of critical pathways. Caution must be used in terms of client confidentiality and privacy in the storage and use of client data. Client consent must be sought when health information is being communicated or transferred to other healthcare providers.

Another technological innovation used in home healthcare and community-based nursing is tele-visiting or tele-health.19 Tele-health allows the nurse to provide advice, counselling and referral for a client’s health problem using the telephone, a videophone or computers with cameras. The client may be at home and the nurse at a different site, or the nurse may be in the client’s home and contact another member of the home healthcare team for consultation. This is particularly useful in remote and isolated communities or for those people who may not want the intrusion of face-to-face contact with the nurse. The community nurse has a definite role in using advanced information technology in the delivery of care to clients and their families. An example is provided by RDNS SA, where nurses use videophone technology to prompt and observe people taking medications. Using this technology means that the client can be prompted to take their medications several times a day, and the nurse can check the medications and observe the client taking the medications through the use of the video phone.

Community nurses must also be knowledgeable about the adaptive equipment or assistive devices used in the client’s home to promote independent functioning. Understanding rehabilitation terminology is helpful in collaborating with therapists and evaluating the client’s plan of care. Medical supplies provided through most home healthcare agencies include urinary catheters, wound care products and IV therapy supplies.

Continuous quality improvement is a priority for community nurses and their agencies. Infection control rates, readmission to hospitals and other facets of clinical care should be monitored and evaluated with respect to quality care and client outcomes. Community-based nursing agencies experience many of the economic influences and constraints on availability of care faced by other healthcare agencies. Community nurses are increasingly expected to provide the maximum amount of quality care in a shorter period of time. In the US, this has led to the implementation of federal regulations requiring client outcome monitoring by home healthcare agencies. The focus on outcome monitoring and length of service is increasingly a part of home healthcare work in Australia and New Zealand.

A holistic, non-judgemental and family-centred philosophy is essential for nurses in the community. In addition to drawing on distinct knowledge, community-based nursing uses a different process of decision making. Community nurses have advanced assessment skills suited to working in a sometimes unpredictable and uncontrolled environment. They focus on empowering the client and family to meet their own needs so that they feel in control of their lives. Goals aim for long-term rather than short-term results. Decision making and priority setting become shared negotiated activities among the client, family and nurse.

Hospice care

Hospice care exists to provide support and care for clients in the last phases of life-limiting diseases so that they might live as fully and as comfortably as possible. Hospice is not a place but a concept of care that provides compassion, concern and support for the dying.32 Hospice care represents a return to previous times when dying individuals were helped to remain at home and to die at home, if possible, surrounded by familiar sights, sounds and smells, and by the love of those who care for them.

Many people wish to die in the comfort of their own home, surrounded by family and friends, but only a relatively small percentage actually do die at home (approximately 17%). Community nurses often work with other healthcare providers to support terminally ill clients to die with dignity in the comfort and familiarity of home without the active medical intervention commonly seen in acute care settings. (Hospice care and palliative care are discussed in Ch 9.)

Home healthcare for the cardiac client

CASE STUDY

Client profile

Mike Makos is 72 years old and was discharged from hospital 8 days after a myocardial infarction. His primary language is Greek. He and his wife live in a large house 8 km from the hospital. His doctor and social worker at the hospital referred him to a community-based nursing agency for follow-up care. Neither Mike nor his wife can drive, and he is presently house-bound because of weakness and shortness of breath. He is unable to attend weekly church services because of his debilitated state and is depressed over his current condition.

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

1. What are the initial priorities for the community nurse?

2. What other members of the home healthcare team should be involved in the care of this client? What are their roles and responsibilities?

3. What type of client education program should be implemented? What are the priority teaching goals?

4. What should the nurse consider in the nutrition assessment? How will the nurse address the cultural considerations related to this client’s diet?

5. How can the nurse address this client’s coping skills and utilise community resources to intervene with his depression?

6. What types of medical equipment will this client need? What teaching should accompany the use of this equipment?

7. His wife inquires about an outpatient cardiac rehabilitation program. What would be an appropriate response from the home healthcare nurse?

8. What are the long-term expected outcomes for this client?

1. Recent changes in the healthcare delivery system are most largely attributed to:

2. In providing community-based client care, nurses:

1 van Loon A. Community nursing in Australia: past, present and future. In: Kralik D, van Loon A, eds. Community nursing in Australia. Oxford: Wiley, 2011.

2 Sargison PA. Gender, class and power: ideologies and conflict during the transition to trained female nursing at two New Zealand hospitals, 1889–95. Women’s History Rev. 1997;6(2):183–200.

3 Grehan M, Nelson S. Visioning the future by knowing the past. In Daly J, et al, eds.: Contexts of nursing, 2nd edn., St Louis: Elsevier, 2006.

4 National Health Priority Action Council (NHPAC). National chronic disease strategy. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing; 2006. Available at www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/pq-ncds-strat accessed 15 April 2011.

5 Littleford A, Kralik D. Making a difference to older people through integrated community care. J Nursing Health Chron Ill. 2010;3(2):178–186.

6 New Zealand Ministry of Health. The primary health care strategy. Available at www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/pagesmh/756, 2001. accessed 15 April 2011.

7 Sexton K, Lennon D, Oster P, et al. The New Zealand meningococcal vaccine strategy: a tailor-made vaccine to combat a devastating epidemic. NZ Med J. 2004;117(1200):U1015.

8 Parliament of Australia. First report: public hospital funding and options for reform. Available at www.aph.gov.au/Senate/committee/clac_ctte/completed_inquiries/1999-02/phealth_first/report/index.htm, 11 July 2000. accessed 15 April 2011.

9 Maurer F, Smith C. Community/public health nursing practice: health for families and populations. St Louis: Elsevier, 2005.

10 Heslop L, Peterson C. The ‘managed care’ idea: implications for health service systems in Australia. Nurs Inq. 2003;10(3):161–169.

11 New Zealand Ministry of Health. Evolving models of primary health care nursing practice. Available at www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/by+unid/7B8611D77164266ECC25705B001BB6BA?Open. accessed 15 April 2011.

12 Duffield C, Gardner G, Chang A. Advanced nursing practice: a global perspective. Collegian. 2009;16:55–62.

13 Klein H. Reforming primary care in Victoria: will primary care partnerships do the job? Aust J Primary Health. 2002;8(1):23–29.

14 Australian Institute of Health & Welfare (AIHW). Australia’s health, 2010. Australia’s heath series no. 12. Cat. no. AUS 122. Canberra: AIHW, 2010.

15 Statistics New Zealand. Our ageing population. Available at www.stats.govt.nz/tools_and_services/services/schools_corner/activities/secondary/teacher-our-ageing-population.aspx. accessed 15 April 2011.

16 McMurray A, Clendon J. Community health and wellness. Primary health care in practice. St Louis: Elsevier, 2010.

17 New Zealand Ministry of Health. Statement of intent, 2006–2009. Part 3. Health priorities for 2006/2007–2008/2009. Available at www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexmh/soi-part-3-health-priorities. accessed 15 April 2011.

18 Swiadek J. The impact of health care issues on the future of the nursing profession: the resulting increased influence of community-based and public health nursing. Nursing Forum. 2009;44(1):19–24.

19 Smith J, King S. The organisation of community nursing in Australia. In: Kralik D, van Loon A, eds. Community nursing in Australia. Oxford: Blackwell, 2008.

20 Electronic Health Records: Australia. eGovernment Resource Centre. Available at www.egov.vic.gov.au/focus-on-countries/australia/trends-and-issues-australia/e-health-australia/electronic-health-records-australia/electronic-health-records-australia.html. accessed 16 April 2011.

21 Department of Health and Ageing. Home and Community Care program overview. Available at www.agedcareaustralia.gov.au/internet/agedcare/publishing.nsf/Content/HACC. accessed 16 April 2011.

22 Stanhope M, Lancaster J. Public health nursing: population centered health care in the community. St Louis: Mosby, 2008.

23 Case Management Society of America (CMSA). Definition of case management. Available at www.cmsa.org/Consumer/tabid/61/Default.aspx, 2008. accessed 16 April 2011.

24 Edwards H, Courtney M, Finlayson K, et al. Chronic venous leg ulcers: effect of a community nursing intervention on pain and healing. Nurs Stand. 2005;19(52):47–54.

25 National Inquiry Concerning the Human Rights of People with Mental Illness (Australia). Human rights and mental illness: report of the National Inquiry Concerning the Human Rights of People with Mental Illness/Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (Burdekin Report). Canberra: AGPS, 1993.

26 Australian Health Ministers. National mental health policy. Canberra: AGPS, 1995.

27 Australian Health Ministers. Second national mental health policy. Canberra: Mental Health Branch, Department of Health and Family Services, 1998.

28 Mason K. Report of the Committee of Inquiry into Procedures Used in Certain Psychiatric Hospitals in Relation to Admission, Discharge, or Release on Leave of Certain Classes of Patients. Wellington: Government Printer, 1988.

29 Mason K. Inquiry under Section 47 of the Health and Disability Services Act 1993 in respect of Certain Mental Health Services: Report of the Ministerial Inquiry to the Minister of Health Hon. Jenny Shipley. Wellington: New Zealand Ministry of Health, 1996.

30 Department of Health and Ageing. A new strategy for community care: the way forward. Available at www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-mediarel-yr2003-ka-ka03142.htm. accessed 16 April 2011.

31 Nay R, O’Donnell M. Caring for older people living in the community. In: Kralik D, van Loon A, eds. Community nursing in Australia. Oxford: Blackwell, 2008.

32 Department of Health and Ageing. National palliative care strategy: a national framework for palliative care service development. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing; 2000. Available at www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/palliativecare-pubs-npcstrat.htm accessed 16 April 2011.

Australian Institute of Health & Welfare. www.aihw.gov.au

Case Management Society of Australia. www.cmsa.org.au

Child Health Nursing Network. www.nurse.org.nz/child-health-nursing-html

College of Nurses Aotearoa (New Zealand). www.nurse.org.nz

Council of Australian Governments. www.coag.gov.au

Council of Remote Area Nurses of Australia. www.crana.org.au

Department of Health and Ageing (Australia). www.health.gov.au

Department of Veterans’ Affairs: Veterans’ Home Care Program. www.dva.gov.au/health/homecare/mainvhc.htm

Elder Person Nursing Network. http://old.nurse.org.nz/epn_nw.htm

HealthConnect. www.health.gov.au/internet/hconnect/publishing.nsf/Content/home

Health Information Strategy for New Zealand 2005. www.oag.govt.nz/2006/wave

Homelessness Australia. www.homelessnessaustralia.org.au

Medicare. www.medicareaustralia.gov.au

Mission Australia. www.missionaustralia.com.au

National Homelessness Information Clearinghouse. www.homelessnessinfo.net.au

New Zealand Ministry of Health. www.health.govt.nz

Nurse Practitioner (New Zealand). www.nursepractitioner.org.nz

Primary Health Nursing Network. http://old.nurse.org.nz/phn_nw.htm

Royal College of Nursing Australia. www.rcna.org.au

Links for Australian nurses working in the community are available at: www.rcna.org.au/pages/networks.php.