Chapter 7 Complementary and alternative therapies

1. Describe the differences between complementary, alternative and integrative therapies.

2. Outline global and national perspectives on complementary and alternative medicine.

3. Discuss the perspectives of integrative healthcare.

4. Discuss ways in which traditional Chinese medicine differs from the practice of conventional medicine.

5. Outline the types, principles and effectiveness of mind–body interventions.

6. Discuss the general types of herbal therapy.

7. Outline the principles of therapeutic touch and healing touch.

8. Explain the scope of practice of chiropractic therapy.

9. Outline roles of the nurse regarding complementary and alternative therapies.

10. Describe a process for assessing patients’ use of complementary and alternative therapies.

complementary and alternative modalities (CAMs)

complementary and alternative therapies (CATs)

Complementary and alternative medicine

The general health of individuals is steadily improving, as evidenced by lower mortality rates and increased life expectancies. Biomedical and technological advances have contributed to these improvements. However, conventional therapy has been less helpful in alleviating some chronic illnesses, such as chronic back pain, fatigue, lymphoedema, anxiety, arthritis, fibromyalgia, insomnia and headaches. Additionally, conventional (allopathic, Western, mainstream) approaches to healthcare tend to be depersonalised and reductionist and often fail to take into consideration all aspects of an individual, including body, mind and spirit connection—that is, a holistic model. Increasing access to global perspectives has resulted in greater exposure to healing philosophies from many cultures, suggesting many new ideas and reviews of traditional systems about health and healing to consumers and healthcare professionals.1

TERMINOLOGY

A variety of terms have been used to describe health-related approaches that are considered outside the mainstream of the dominant system of healthcare. The terms currently used in Western cultures to describe such approaches include alternative, complementary, integrative, non-traditional, unconventional, holistic, natural and unorthodox. Currently, the most frequently used term to refer to such modalities and practices is complementary and alternative therapies. Complementary and alternative therapies (CATs) are defined as a ‘broad domain of healing resources that encompasses all health systems, modalities, and practices and their accompanying theories and beliefs, other than those intrinsic to the politically dominant health system of a particular society or culture in a given historical period’.2 The definition highlights that what may be considered complementary and alternative in one country or at one period in time may be considered conventional in another place or time. Notably, most of these therapies were developed outside the mainstream of conventional biomedical approaches and are generally available without medical authorisation. Furthermore, many of these modalities, now labelled complementary and alternative modalities (CAMs), are often health promotion and lifestyle practices, and are similar to autonomous nursing interventions—such as touch, massage, stress management and activities to facilitate coping—that have been used for centuries. Nursing needs to identify these and other interventions that demonstrate core values of creating healing relationships and caring which differentiate nursing from the biomedical approach to caring.

The year 2010 was the centenary year of Florence Nightingale (1820–1910) and the International Year of the Nurse—a timely opportunity for nurses to reflect on health/nursing care based on holistic and relationship-centred care and optimal healing environments. Healthcare is changing from an impersonal, expensive, high-technology system that is doctor-directed to one that recognises the need for patients to be empowered so that they take responsibility for achieving high levels of wellness and to heal from illness.3 Within this new arena nurses have opportunities to reframe their relationships with patients as they integrate scientific and evidence-based advancements with healing traditions and philosophies. As nurses blend the art and science of evidence-informed practice for each therapy, they recognise the use of intention: ‘Intention is the conscious awareness of being in the present moment to help facilitate the healing process.’4

INTEGRATIVE HEALTHCARE

Integrative healthcare (IHC) is evolving as a new direction in healthcare in line with primary healthcare philosophies. It combines CAT with the creation of healing relationships with patients to establish a holistic blend of biomedical and caring modalities to provide greater harmony and balance in life.5,6 IHC has been referred to as a perspective of healthcare that holds a ‘whole person’ philosophy of health and healing, blending alternative, complementary and conventional interventions that enhance curing and healing.7 The integrative nurse clinician is ‘a certified holistic nurse who performs needs assessments of patients and the clinical environments and initiates appropriate healing interventions to enable positive changes in health’.7

The public has started to realise the limitations of Western medicine and wants more attention paid to the health and healing of the whole person. Consumers are influencing changes in the conventional healthcare system, with a recognition of their rights, increasing healthcare costs and dissatisfaction with the paternalism of some providers resulting in many consumers taking a more active role in their healthcare.3 Often, without their traditional healthcare provider’s knowledge or consent, consumers seek the services of complementary and alternative therapists. As ways of delivering care become more diverse and primary healthcare teams more flexible, the potential will grow for more complementary practitioners to play a role in meeting the changing needs of patients.

Integrative healthcare is particularly helpful for meeting these needs, especially for chronic and degenerative conditions that do not respond well to the treatments of conventional medicine, such as irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue and chronic pain syndrome.8 IHC assumes that the body has an innate capacity for healing. Consequently, the primary goal of IHC should be to support, facilitate and augment that innate ability.9 Complementary and alternative therapists work in harmony with the natural healing processes of the body by:

• engaging in a relationship of partnership-centred care, where the client has an active role

• recognising that the healthcare professional’s self and energy play a part in the therapeutic relationship

• integrating conventional and complementary methods of prevention and treatment

• removing barriers to activate the body’s healing response

• using natural, less invasive interventions before invasive, high-risk ones wherever possible

• engaging mind, body, spirit and community to facilitate healing

• valuing subjective data as a highly important adjunct to objective data

• recognising that healing is always possible, even when curing is not.3,8

It is essential to build an infrastructure that supports an integrative healthcare emphasis and this may be guided by the implementation of interprofessional education.10 Tovey and Broom note that assessment of the appropriateness of CAM integration is ‘mediated by engagement with the issues of evidence, risk, cost location of provision and professional and epistemological identity of providers’.10 A tension for both integrative healthcare and nursing relates to whether people’s ability to use CAM alongside biomedical treatments, without losing their faith in medicine, is a use of multiple health modalities or a true shift in philosophy towards integrative health. ‘The development of an integrative healthcare system will necessitate a major change in the current system of healthcare’ and, while some models of integrative healthcare are available, ‘there remains a paucity of evidence to demonstrate IHC is more effective than conventional care at improving client health outcomes and quality of life’.10 Urgent research is needed to facilitate a more rapid movement towards IHC.9

GLOBAL CONTEXT

People are increasingly seeking alternatives or supplements to conventional approaches. The World Health Organization (WHO) and healthcare professionals have raised important questions about the effectiveness and safety of complementary and alternative approaches in the face of their increased use by consumers. In response to this need, WHO released the report, Traditional medicine strategy, 2002–2005, which acknowledges the regional diversity in the use and role of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine.11 This was followed up with the report, National policy on traditional medicine and regulation of herbal medicines, which indicates that the development of national policies and regulations is an essential indicator of the level of integration of such medicine within a national health care system.12 This report also notes that countries face many challenges in regulating traditional, complementary and herbal medicines. These challenges are based around an assessment of safety and efficacy, quality control, safety monitoring and lack of knowledge about traditional medicine and CAM within national drug regulation authorities. WHO also provides a fact sheet on traditional medicine, which is a valuable resource.13

Early significant studies in the US show an estimated US$15 billion per annum is spent on complementary therapies, with approximately one in four Americans using some aspect of complementary therapy.14 The most common therapies used include massage, chiropractic therapy, hypnosis, biofeedback and acupuncture. CATs are harmonious with many of the values of nursing. These include a view of humans as holistic beings, an emphasis on healing, recognition that the provider–client relationship should be a partnership, and a focus on health promotion and illness prevention. Braun and Cohen suggest that the holistic approach to healthcare can be summarised by a SENSE approach: stress management, exercise, nutrition, social and spiritual interaction, and education.15

Nursing’s interest in holistic nursing and CATs is reflected in the formation of specialty nursing groups. For example, the American Holistic Nurses’ Association was established in 1980 to facilitate care for the ‘whole’ patient and significant others by focusing on holistic principles of health, preventative education and the integration of caring–healing modalities.16 The Holistic Nurses Association of Australia was founded in 1991, and became known as the Australian College of Holistic Nurses (ACHN) in 1998, fostering similar philosophies until the group disbanded in 2004. The loss of this voluntary group through financial and geographical issues has been unfortunate for nurses who support a holistic perspective.

There is mounting evidence that CAMs are growing in popularity in Australia, and it is estimated that about 60% of Australians access some form of complementary healthcare.17–20 One study that sought to identify hospital patients’ reported use of CAMs found the use as high as 90.4% among respondents, with a high proportion reporting using non-herbal supplements (60.3%) and massage therapy (45%).21 Much work has focused on traditional Chinese medicine,22 and a discussion paper on establishing minimum standards for the conduct and safety of CATs was supported out of session by the Australian Health Minister’s Advisory Council.20 In September 2003, an expert committee reported on complementary medicines in the Australian healthcare system,23 and in March 2005 a government response to these recommendations was issued.24 Although the report mentions complementary therapies, the thrust of the information and the government response specifically relates to the safety of research concerning complementary medicines, with strong links to the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). In Australia, minimal formal investigation has been undertaken regarding complementary therapies per se, and CAM has been described as a popular, diverse and unofficial form of healthcare that runs in parallel with mainstream healthcare but has little interaction with it.25 At the third International Congress on Complementary Medicine in 2008 the Australian government announced funding of more than $7 million in grants for CAM, indicating that Australians spend more than $2 billion nationally on complementary medicine, with up to two-thirds of Australian adults using at least one product and one-quarter using complementary medicine services.26 There is growing testimony that complementary medicine can make a significant, cost-effective contribution to public health in chronic disease management and in preventative care. The TGA has provided the Australian Regulatory Guidelines for Complementary Medicines (ARGCM), which are structured in five parts.26

In New Zealand, there are an estimated 10,000 CAM practitioners nationally, even though the regulatory systems are still being developed and the process of integration is in its infancy.27 A Ministerial Advisory Committee on Complementary and Alternative Health (MACCAH) was established in 2001 and results from a survey by MACCAH in 2002–2003 indicated that approximately one in four adults had visited a CAM practitioner over a 12-month period. As a result, a policy document was presented to the Minister for Health in 2003, followed by advice to the Minister in 2004. These documents resulted in the recognition that there was a demand for greater integration of CAM into mainstream healthcare practice.27 In an effort to provide guidance, the Australia New Zealand Therapeutic Products Authority proposed regulatory definitions for complementary and homeopathic medicines.28

In the UK in the last decade CAM research has been highly successful, despite a lack of financial support.29 Important landmarks include a report on CAM in 2000 by the House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology, which indicates how far the CAM movement has progressed over the past decade and provides a description of CAM disciplines.

The use of and research into CAM in Canada is growing rapidly, as in other countries.30 One initiative has been the establishment of IN-CAM, the Canadian Interdisciplinary Network for Complementary and Alternative Medicine Research, to foster excellence in CAM research. Another initiative, the Holistic Health Research Foundation of Canada, is a national registered charitable organisation dedicated to funding research, as well as public and health professional education, in complementary and alternative healthcare.31 The association provides an introductory booklet describing various complementary therapies and the philosophy behind them.32 Canada also hosts one of the few paediatric support associations, the Pediatric Complementary and Alternative Medicine Research and Education (PedCAM) Network, created in 2004, to support and facilitate the safe and effective use of complementary and alternative medicine in children. This organisation provides a valuable poster encouraging parents to discuss their use of complementary therapies for their children with their doctor and other healthcare practitioners.32

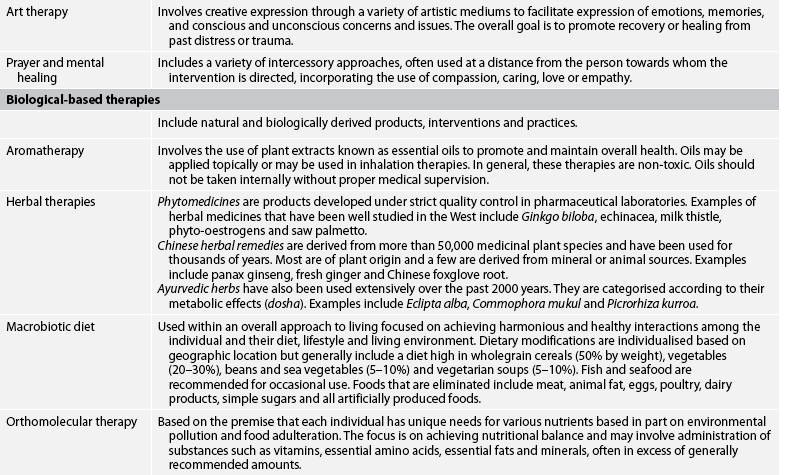

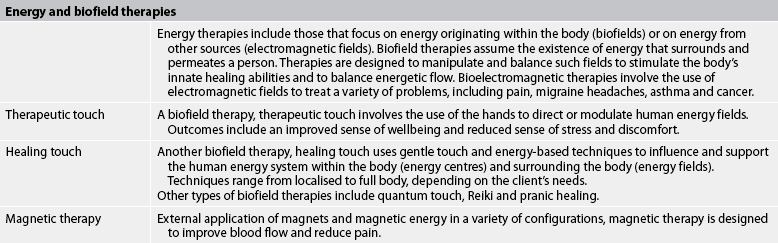

In the US, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) was established as part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to: (1) conduct and support basic and applied research and research training on complementary and alternative approaches; and (2) disseminate scientifically based information on complementary and alternative research, practice and findings to healthcare providers and consumers. In conjunction with NCCAM, the Cochrane Collaboration established a focus area on complementary and alternative approaches, providing a valuable source for synthesised evidence on this topic.33 NCCAM has proposed a classification system for CATs that includes five major categories with various types of approaches under each category: (1) alternative medical systems; (2) mind–body interventions; (3) biological-based therapies; (4) manipulative and body-based methods; and (5) energy therapies.17 Table 7-1 includes descriptions of the major categories and selected approaches within each category. The list continually changes as practices proven safe and effective become accepted as mainstream healthcare practices. This chapter discusses CATs using NCCAM’s major categories as an example of a classification system and addresses selected therapies in more detail.

Alternative medical systems

Alternative medical systems involve complete methods of health-related theory and practice that have been developed outside the Western biomedical model. Many are traditional systems that are practised by individual cultures throughout the world. Traditional Aboriginal medicine is one system that is currently a new area of consideration as a holistic approach. Indigenous Australian medicine takes a holistic approach to the mind–body–spirit perspective, including the environment or the health of the land as part of this. It has used the properties of many Australian native plants (e.g. Eucalyptus [gum tree] and Melaleuca [tea-tree]) for medicinal purposes for more than 60,000 years.34 Knowledge of such use has been inherited through the oral tradition and is in danger of being lost or fragmented. Flower remedies or essences also fit into this category and are becoming increasingly popular as part of the natural remedies.35 A number of cultures, including Egyptian, African and medieval European, demonstrated the use of flowers to treat emotional states. Indigenous Australians obtained the beneficial effects of a flower essence by eating the whole flower, including the dew containing the essence. Flower remedies provide support for many problems and are a valuable aid to self-care.36 However, the research into flower remedies is currently limited.

Māori practices have similar philosophical, holistic foundations, and traditional healing includes mirimiri (massage), rongoa (herbal treatments) and karakia (spiritual prayer). The New Zealand Ministry of Health (MOH) is attempting to incorporate Māori healthcare into mainstream practice and, in collaboration with the National Body of Traditional Māori Healers (TMH), has released national standards for traditional Māori healing (see the Resources on pp 124–125).28

Traditional Chinese medicine and acupuncture is one of the alternative medical system subcategories that NCCAM has identified.

TRADITIONAL CHINESE MEDICINE

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is one of the world’s oldest and most comprehensive medical systems. Over the past several thousand years, it has evolved based on cultural and philosophical developments, as well as extensive clinical observation and testing. Several major concepts constitute TCM. The principle of Yin and Yang (see Fig 7-4) is a core tenet of Chinese art, philosophy and science, as well as TCM. Yin and Yang are viewed as dynamic, interacting and interdependent energies, neither of which can exist without the other, each containing some part of the other within it. These energies are a part of everything in nature and must be maintained in a harmonious state of balance to achieve optimal health. Balance in Yin and Yang emphasises coexistence, dynamic change without fixing one’s ideas and mutual acceptance in the spirit of differences.37 Various states are associated with Yin (cold, moist, heavy, negative) and Yang (hot, dry, light, positive) energies. Imbalance is associated with illness. Causes of imbalance include situations such as excessive wetness, dryness, cold, heat and emotional states, and other factors, such as dietary irregularities, imbalanced living habits, hereditary conditions and social forces. In the case of imbalance, Yang treatments are used to restore balance to excessive or deficient Yin conditions, and vice versa.

Figure 7-4 Yin–Yang symbol. The circle representing the whole is divided into Yin (black) and Yang (white). The small circles of opposite shading illustrate that within the Yin there is Yang and within the Yang there is Yin. The dynamic curve dividing them indicates that Yin and Yang are continuously merging. Thus, Yin and Yang create each other, control each other and transform each other. When Yin and Yang are in balance, Qi (pronounced ‘chee’), or the fundamental life force, flows evenly through the body, leading to good health.

Practitioners of TCM view human beings in terms of five inseparable dimensions. These include Qi (pronounced ‘chee’—energy or the primal life force resulting from the interaction of Yin and Yang), Jing (genetic material of the physical body), Shen (spirit or all aspects of the mind, including mental, emotional, spiritual and creative activity), blood (considered the physical manifestation of Qi) and Jin Ye fluids (responsible for lubricating and moistening the organs). In addition, the Five Element Theory addresses various cyclical transformations that occur in nature. The five elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, water) correspond to the five energetic organ networks (liver/gall bladder, heart/small intestine, spleen/stomach, lung/large intestines, kidney/urinary bladder). These networks include not only physical but also psychological and spiritual functions. Additionally, the body is believed to contain a series of energetic pathways, known as the meridian systems, through which Qi and other life energies flow, nourishing the body. TCM recognises 12 major meridian pathways. Specific sites along the pathways, referred to as acupoints, allow access to the meridian system. There are several hundred acupoints, each corresponding to particular organs and their functions.

Treatment modalities used in TCM include acupuncture, Chinese herbal medicines, dietary therapy, massage, scraping, moxibustion (explained below), exercise therapy (Tai Chi or Qigong) and meditation.37 The most well-known of these in the Western hemisphere is acupuncture. In acupuncture, Qi is accessed and modified by stimulating specific acupoints (see Fig 7-5). Small (30–36 gauge) needles are used and, once inserted in a painless process, are left in place for 20–40 minutes. A process known as moxibustion may be used to warm the needles after they are inserted, thus increasing Qi and blood flow. Electrical stimulation may also be used and is helpful for persistent pain and numbness. Findings from research conducted from the perspective of Western biomedicine indicate that acupuncture can cause multiple biological responses. These include the release of endorphins, activation of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, alterations in immune function, and alterations in the levels of neurotransmitters and neurohormones.

Clinical applications of acupuncture

Acupuncture is the primary treatment modality used by doctors of TCM and it is one of the most common complementary therapies recommended by general practitioners. Many allopathic or conventional doctors and healthcare professionals are also being trained and certified in acupuncture. WHO lists more than 40 disorders that may benefit from acupuncture (see Box 7-1). An NIH Consensus Panel concluded that although additional research is needed, clinical studies have indicated that acupuncture is clearly effective in treating adult postoperative and chemotherapy-associated nausea and vomiting, as well as postoperative dental pain. Scientific evidence shows acupuncture to be effective for conditions such as knee pain (including osteoarthritis), tension headache, and nausea and vomiting.38–40

Limitations of acupuncture

Acupuncture is considered a safe therapy when: (1) the practitioner has been appropriately trained; and (2) the practitioner uses sterilised or disposable needles. Although complications, such as a slight risk of pneumothorax or infection, have been noted, they are rare if appropriate steps are taken to ensure the safety of equipment and the patient. Acupuncture should be used with caution in people who have a history of seizures, are carriers of hepatitis B or have chronic hepatitis C, or have human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, bleeding disorders, thrombocytopenia or skin infections.

Mind–body interventions

Mind–body interventions include a variety of techniques designed to facilitate the mind’s capacity to affect bodily function. These include behavioural, psychological, social and spiritual approaches to health. Specific examples of therapies and approaches are included in Table 7-1. It should be noted that behavioural approaches such as health counselling, certain uses of hypnosis, biofeedback, patient education and support groups are considered by NCCAM as mainstream within the category of mind–body methods. Nurses frequently use many of these biobehavioural approaches (see Box 7-2).

BOX 7-2 Mind–body interventions that can be used by nurses

Meditation (see Fig 7-2)

• Variety of techniques designed to create a sustained period of time in which one focuses attention and increases self-awareness.

• May include passive meditation (sitting meditation) or more active forms of meditation (walking meditation).

• Health benefits include increased oxygen uptake; reduction in blood pressure, heart rate and muscle tension; and enhanced pain tolerance and immune response.

• Once learned (and it can be self-taught) it is an appropriate self-care technique.

Relaxation

• Variety of relaxation techniques can be used to create a state of physical and mental calmness, peacefulness and wellbeing, or the ‘relaxation response’.

• Assists people in increasing self-awareness of their stress level and its physical manifestations.

• Most relaxation techniques focus on some aspect of the physical body (e.g. breathing, muscle tension).

• Used to reduce blood pressure and to decrease heart, respiratory and metabolic rates, as well as in the treatment of pain, anxiety, depression and other conditions related to stress.

• Once learned (and it can be self-taught), relaxation is appropriately practised as a part of self-care.

Imagery

• Process of using mental images to create a desired state.

• Desired states may include relaxation, enhanced sports performance, pain relief or immune modulation.

• Should be individualised, using an individual’s dominant sensory mode (e.g. visual, auditory, kinaesthetic) and avoiding images that are individually distressing.

• Once learned (and it can be self-taught), the use of imagery is well suited as a self-care technique.

Biofeedback (see Fig 7-6)

• Biofeedback training involves the use of various monitoring devices that help people become more aware of and able to control their own physiological responses, such as heart rate, body temperature, muscle tension and brain waves.

• During biofeedback training, people use information (e.g. electroencephalogram, electrocardiogram, electromyogram, galvanic skin response, skin temperature) to recognise normal or desirable physiological states and then use techniques such as imagery or relaxation training to achieve those states.

• Desirable states include normal heart rate, slow deep breathing, warm skin and decreased galvanic skin response.

• Biofeedback training requires specialised training for both practitioners and patients. After such training, patients can appropriately use the techniques as part of self-care.

• After the individual is able to achieve the desired states, biofeedback is no longer needed.

Health counselling

• Most popular forms include classic or Freudian, Jungian, cognitive–behavioural, humanistic–existential, solution-focused and family.

• Emphasis is generally on an exploration of psychological issues, although each of these approaches has its own unique approaches and outcomes.

• Has been shown to be effective in addressing a variety of mental and emotional problems and may also contribute to positive physical changes.

• Advanced education programs are recommended if counselling extends beyond that which is integrated with other techniques.

Figure 7-6 Biofeedback monitoring. Electrodes are placed on the frontalis and trapezius muscles, as well as the fingers on the left hand. Pneumograph measurements are also made.

TAI CHI

Tai Chi is an ancient system of exercise that integrates slow and graceful movement with focused breathing and visualisation to stimulate the flow of Qi (energy) throughout the body. The improved flow of Qi leads to increased self-awareness, vitality, oxygenation of the blood, resistance to disease and improved sleep. Tai Chi developed within the context of TCM and reflects its concern with the regulation of balance within the mind, body and spirit. Tai Chi consists of a sequence of standardised movements, each sequence of which is known as a form. When properly performed, the movements are precise and synchronised with breathing. The movements are low impact and low velocity. After the basic forms are learned, Tai Chi can be practised in any location without special clothing or equipment.

Clinical applications of Tai Chi

Tai Chi is a gentle movement process. It is recommended for the reduction of muscular stress and tension, the promotion of relaxation, increase in flexibility, improvement of posture and overall health enhancement. Tai Chi appears to be effective in reducing pain and functional disability in people with fibromyalgia.41 Use of Tai Chi has been shown to increase balance, decrease falls and reduce fears of falling, as well as increase the flexibility and sense of wellbeing in older adults. When a group of elderly Tai Chi practitioners was compared with sedentary controls, the Tai Chi group had higher oxygen uptake, lower body fat and better spine flexibility.42,43 One study that aimed to investigate the effectiveness of Tai Chi arm and breathing exercises in reducing upper limb volumes, tissue hardness and subjective symptoms (including fatigue) in women who had clinically discernable lymphoedema following treatment for breast cancer concluded that Sibashi exercises improved subjective lymphoedema symptoms but not fluid volumes, tissue hardness or fatigue.44

SPIRITUALITY

Spirituality includes prayer and other unifying practices that: (1) help people to have a connection with something beyond themselves; (2) help give a sense of purpose and meaning to life; and (3) facilitate personal transcendence beyond the present context of reality.45 The term spirituality is derived from the Latin word spiritus, meaning breath. It is also related to the Greek term pneuma (breath), which refers to the vital spirit or soul.46,47 Healing is essentially a spiritual process that attends to the wholeness of the person—that is, the body–mind–spirit connection where caring relationships help to create the sacred space of healing.47 Prayer is an intervention that is widely used to promote health and alleviate illness. Intercessory prayer is an organised and regular form of prayer in which an individual communicates with a higher power on behalf of another who is in need.

Other spiritual practices include meditation, appreciating nature, connecting with friends and family, reading inspirational literature, helping others and participating in community groups with a spiritual or holistic focus.48 A number of these spiritual practices have derived almost exclusively from a Judeo-Christian tradition and may fail to consider perspectives on spirituality inherent in Islam or other religious traditions.49 There are longstanding debates about the relationship between spirituality and religion. Religion can be viewed as one, but not the only, way that people can access, develop and practise their spirituality. Meditation can be considered a spiritual practice on a more universal level. Meditation can be described as a process that maintains physical and mental balance by combining controlled breathing with focused concentration. Originally, meditation appears to have been developed independently by traditional drummers, singers, dancers and hermits, each in their own way. Although associated with both religious and Eastern traditions, such as yoga, it did not come from India or Tibet ‘but rather those places where it was widely practised before it was written down’.5 The benefits associated with a developed spiritual practice include an improved sense of wellbeing and lower levels of depression.50 During times of illness, effective spiritual coping strategies may help an individual find meaning in the illness and lead to increased coping abilities and decreased emotional distress.

Clinical applications of spirituality

Frequently used nursing interventions to address spirituality include referral to ministers or chaplains, prayer, active listening, facilitating and validating of patients’ thoughts and feelings, conveying acceptance and instilling hope. Several randomised clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of intercessory prayer for a variety of illnesses. A meta-analysis of these clinical trials concluded that although there were positive effects in some studies, overall the data were insufficiently conclusive to make definitive statements about the effectiveness of intercessory prayer.51 However, additional research is needed to further clarify the relationships between intercessory prayer and health outcomes.

If appropriate, nurses can assess patients’ usual spiritual coping strategies and develop a plan to support those strategies as needed. Nurses may also work in collaboration with others, particularly ministers, pastors and chaplains, to meet the complex spiritual needs of all patients. Nurses who are specifically interested in a practice focused on spiritual intervention can explore parish nursing, a specialty that emphasises the relationship between spirituality and health.52 Nurses may also find supporting or teaching meditation a valuable health practice.

Self-care for complementary therapy practitioners is also an important aspect. The Sacred Space Foundation is a British charity that provides peaceful and confidential rest, retreat and recuperation facilities. It was founded by a group of doctors and nurses almost 20 years ago and helps those suffering from the extremes of stress, burnout, emotional exhaustion or spiritual crisis.53 The Foundation’s website provides valuable information regarding strategies for maintaining spiritual health (see the Resources on pp 124–125).

Limitations of spirituality

No adverse effects have been documented as a result of spiritual interventions. A potential problem may occur when the nurse and patient have differing views of spirituality. For example, the nurse needs to examine carefully the ethics of praying for a patient who has indicated no interest in spiritual interventions. If a patient asks for assistance with a particular spiritual intervention that is inconsistent with the nurse’s beliefs, assistance from another nurse or a chaplain may be needed.

Biological-based therapies

Biological-based therapies include herbal therapies (phytotherapy; see below), special diet therapies, aromatherapy and orthomolecular medicine see (see Table 7-1).

Aromatherapy is unique among the healing modalities in using aromas to link the sense of smell into the healing process. In many countries it has sustained increasing interest and consideration within nursing through such methods as massage via carrier oils, compress and vaporisation. Essential oils used in aromatherapy are volatile substances extracted from plant materials by a variety of methods. The use of aromatherapy in nursing has developed significantly over recent years. Safe practice requires an excellent knowledge of the chemical properties of essential oils and their therapeutic indications and contraindications.7 In relation to healing, essential oils can have a physical effect as well as bactericidal, anti-inflammatory and antifungal effects, while at the same time affecting the mind and the emotions to sedate, calm and uplift.54 The effect of essential oils on the limbic system has been ‘mapped’ using computer-generated tomographics, which produces brain electrical activity maps (BEAM) that indicate the psychological effect.55 Research exists supporting the use of aromatherapy, although some authors suggest that strategies that are more compatible with the holistic nature of complementary therapies should be sought.56

Orthomolecular medicine (sometimes referred to as megavitamin therapy) aims to prevent or treat diseases through dietary supplements that are seen as the right nutritional molecules in the right amounts for the individual.

HERBAL THERAPY

Herbal therapy uses individual herbs or mixtures of herbs for therapeutic value (see Fig 7-7). A herb is a plant or plant part (bark, roots, leaves, seeds, flowers, fruit) that produces and contains chemical substances that act on the body. It is estimated that approximately 25,000 plant species are used medicinally throughout the world and approximately 30% of modern prescription drugs are derived from plants. Botanical medicine is the oldest known form of medicine and archaeological evidence suggests that Neanderthals used plant-based remedies 60,000 years ago. Use of herbal therapy gained widespread popularity in many countries as early as 3000 BC, but began to decline with the development of modern scientific medicine in the early 18th century. However, approximately 80% of the world’s population currently relies extensively on plant-derived remedies.

In the US, nearly one in five adults reported using a natural product such as herbs for health purposes in a 2007 survey.57 In Australia, naturopathy forms an eclectic healthcare practice comprising the core modalities of herbal medicine and nutritional medicine. For Australia, naturopaths rate with chiropractors and acupuncturists as the most commonly consulted complementary medicine practitioners.18 Naturopathy makes use of orthodox diagnostic techniques and techniques such as iridology, dark field microscopy, bioelectrical impedance, humoral theory and adapted traditional Chinese medicine diagnostic techniques.57

Over the past 30 years, a resurgence of interest has occurred in herbal therapies in countries whose healthcare is dominated by conventional medicine. Interest in herbal products is related to several factors, including the high cost and the potential for severe side effects associated with pharmaceutical drugs. Herbal remedies are considered ‘natural’ and therefore may be viewed as healthier and safer. They are available directly to consumers and appeal to people who desire personal control and autonomy over their health, as well as to people who have limited access to conventional healthcare.58 Commonly used herbs include Echinacea, garlic, comfrey, ginger, aloe, ginkgo, cranberry, ginseng, St John’s wort, valerian, lavender and eucalyptus.

Regulating agencies in Germany, France, the UK and Canada enforce standards of quality and safety assessments on manufacturers. In contrast, in the US herbal products used for their medicinal value are classified as dietary supplements. As such, they lie outside the jurisdiction of many of the safety and regulatory rules covering foods and drugs, and so can be marketed without proven safety or efficacy and with no standards for quality control. Regulation in Australia falls within the TGA, and the Office of Complementary Medicine was established in 1999 as part of the Commonwealth complementary medicines reform package. For a complementary product to be listed under the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 it must demonstrate evidence of safety rather than efficacy.22

The practice of phytotherapy is also regulated in many parts of the world. For example, in France all phytotherapists are also credentialled doctors, and in Germany 70% of all general medical practitioners prescribe herbal remedies to their patients. The governments of China and Japan officially support herbal therapies within their national healthcare systems. However, in Australia and New Zealand information about herbal remedies is most often obtained at health food stores, through informal word of mouth and from books, magazines and the internet.

Clinical applications of herbal therapy

Medicinal plants work in much the same way as drugs; both are absorbed and trigger biological effects that can be therapeutic. Many have more than one physiological effect and thus have more than one condition for which they can be used. The range of action of herbs is extensive. A number of internet resources provide information on herbal therapies (see the Resources on pp 124–125) to healthcare providers and consumers. Internet sites that provide information should be evaluated carefully. Information used in evaluation should include the sponsoring organisation and its credibility, the frequency of updates, the types of supporting evidence included and whether advertising for specific products is used.

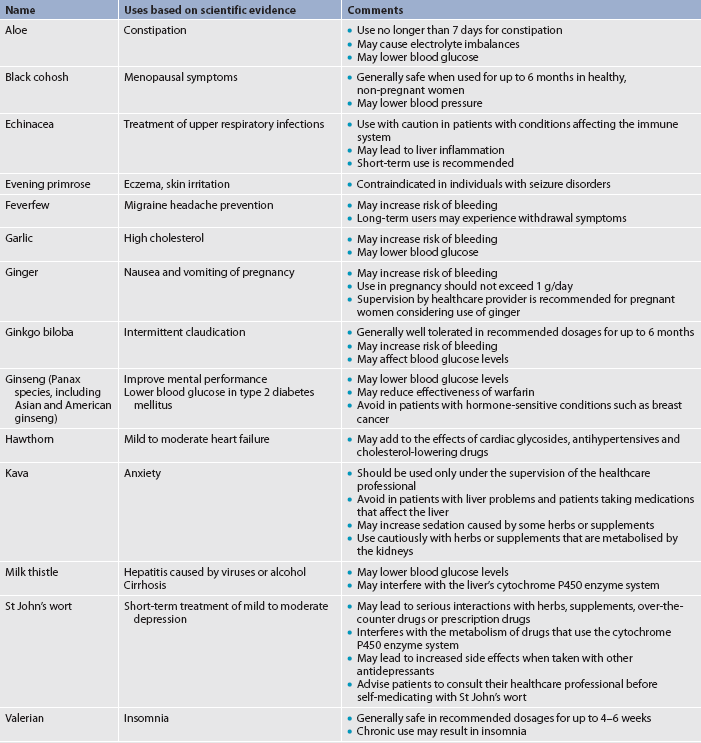

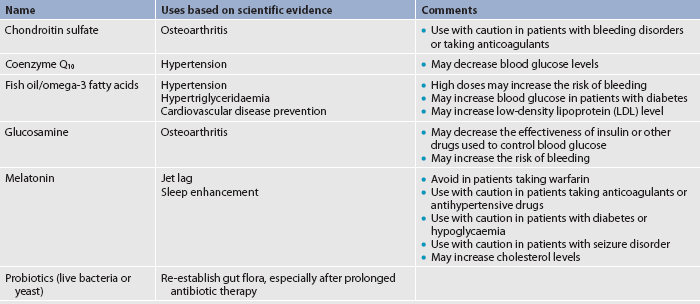

A number of herbs have been determined to be safe and effective for a variety of conditions. These herbs, as well as the most frequently used herbal remedies, are included in Table 7-2. Commonly used dietary supplements are found in Table 7-3. Boxes outlining herbs related to specific diseases are found throughout the book (see the Complementary & alternative therapies box on p 116).

TABLE 7-2 Commonly used herbs*

* Advise patients who are pregnant or lactating to consult their healthcare practitioner before using any herbs. There is limited scientific evidence for the use of most herbs during pregnancy or lactation.

Source: Data from www.naturalstandard.com.

TABLE 7-3 Commonly used dietary supplements*

* Advise patients who are pregnant or lactating to consult their healthcare practitioner before taking any supplements. There is limited scientific evidence for the use of most supplements during pregnancy or lactation.

Source: Data from www.naturalstandard.com.

Limitations of herbal therapy

Although herbal therapies have been shown to provide beneficial effects for a variety of conditions, side effects and interactions with prescription drugs have been described. There is concern that side effects resulting from the use of herbal remedies are underreported, thus promoting the impression that herbal remedies are completely safe to use. Because people tend not to share their use of herbal remedies and dietary supplements with their primary healthcare provider, herb–drug interactions may also be underreported. For example, patients who are scheduled for surgery should be advised to stop taking herbal remedies 2–3 weeks before surgery.59 Herbal products that interfere with surgical procedures are discussed in Chapter 17. Patients who are being treated with conventional drug therapy should be advised to discontinue herbal remedies with similar pharmacological effects because the combination may lead to an excessive reaction or to unknown interaction effects. General patient teaching guidelines related to herbal therapy use are presented in Box 7-3.

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

• Ask the patient about their use of herbal therapies. Take a complete history of herbal use, including amounts, brand names and frequency of use. Ask the patient about allergies.

• Investigate whether herbs are used instead of or in addition to traditional medical treatments. Find out whether herbal therapies are used to prevent disease or to treat an existing problem.

• Instruct the patient to inform their healthcare provider before taking any herbal treatments.

• Make the patient aware of the risks and benefits associated with herbal use, including drug reactions when taken in combination with other drugs.

• Advise the patient using herbal therapies to be aware of any side effects while taking herbal treatments and to report them immediately to their healthcare provider.

• Advise patients to avoid using herbs for serious medical conditions (e.g. heart disease, bleeding conditions).

• Explain that moisture, sunlight and heat may alter the components of herbal treatments.

• Inform the patient of the need to be aware of the reputation of the manufacturers of herbal products and the safety of the product before buying herbal treatments.

• Encourage the patient to read the labels of herbal therapies carefully. Advise the patient not to take more than the recommended amount.

• Explain that most herbal therapies should be discontinued at least 2–3 weeks before surgery.

• Inform the patient that the employees of health-food stores are not trained healthcare professionals.

• Inform the patient that many ‘herbal therapies’ available on the internet contain traditional drugs, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or corticosteroids.

Some herbs, even in small amounts, are toxic. For example, germander, used in some weight loss programs, has been associated with cases of fatal fulminant hepatitis. Some herbs have also been found to contain toxic products that can cause cancer. For example, comfrey has been widely used for its wound-healing properties and comfrey leaf continues to be sold in ointment form for topical application. However, comfrey root has especially high concentrations of certain pyrrolizidine alkaloids, which are highly carcinogenic. Comfrey should not be used internally, although ointments containing comfrey leaf are considered safe when applied to intact skin for limited amounts of time.60

Patients should be advised that if they take herbal therapies, they should adhere to the suggested dosage. If herbal preparations are taken in high doses, they can be toxic. The potency of a particular herbal remedy can vary widely because of factors such as where and how it was grown, as well as harvesting and processing methods. Patients who take herbal remedies should be advised to be cautious when changing brands of herbal products used. Contamination of herbal products with other herbs or substances such as pesticides or heavy metals (e.g. arsenic, lead, mercury) used in processing has been documented. A major source of many of these problems is the lack of control and standardisation in the manufacture of herbal preparations. For this reason, herbal medicine should be purchased only from reputable manufacturers. In addition, labels on herbal products should contain the scientific name(s) of the herb(s), the name and address of the actual manufacturer, the batch or lot number, the date of manufacture and the expiry date. An ongoing concern expressed by practitioners of conventional medicine is that the use of herbs may cause patients to forgo potentially curative conventional care. Another concern is that patients will treat themselves for diseases not recommended for self-treatment (e.g. clinical depression or HIV).

Because of the potential for adverse effects, herbal products should be used with caution in pregnant women, nursing mothers, children and older adults with liver or cardiovascular disease. Much is still unknown about herbal remedies. Research efforts are focused on identifying the biologically active components of herbal remedies, documenting their biological effects and evaluating their effectiveness when compared to either placebo or traditional drug therapy. Use of whole herb products and examination of subtle effects on biological and emotional functioning must also be studied before a complete understanding of the effects of herbal therapy can be achieved. Braun and Cohen note: ‘It is also important to recognise that a lack of evidence for a particular effect does not mean that there is evidence for a lack of effect.’15

Manipulative and body-based methods

Manipulative and body-based methods include interventions and approaches to healthcare that are based on manipulation or movement of the body. Examples include chiropractic therapy, massage and body work such as reflexology, osteopathy and unconventional physical therapies such as hydrotherapy (see Table 7-1). Reflexology has been used in some form since ancient times, with evidence of foot treatments particularly strong in Egyptian, Indian, Chinese and Native American Indian cultures. In addition to general relaxation, reflexology can be used to treat a variety of conditions, such as pain, especially chronic pain (e.g. back, arthritis), skin problems and gastrointestinal tract conditions. Research is limited, with some evidence pointing to a relaxation effect, although criticism has been raised regarding rigour in the methodologies.61 Potentially, reflexology could be a valuable therapeutic nursing skill, but more research-based evidence is needed to allow its integration into mainstream healthcare.

Information related to various complementary and alternative therapies can be found in the following boxes throughout the book.

COMPLEMENTARY & ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

| Title | Chapter |

|---|---|

| Acupuncture | 63 |

| Bilberry | 21 |

| Biofeedback for urinary incontinence | 45 |

| Echinacea | 26 |

| Ginger | 41 |

| Ginkgo biloba | 59 |

| Glucosamine | 64 |

| Goldenseal | 26 |

| Herbs and dietary supplements that affect blood clotting | 37 |

| Herbs that affect blood glucose levels | 48 |

| Herbs and supplements used for menopause | 53 |

| Herbs and surgical patients | 17 |

| Imagery | 51 |

| Music therapy | 18 |

| Natural lipid-lowering agents | 33 |

| Saw palmetto | 54 |

| Zinc | 26 |

Touch permeates people’s lives in subtle but influential ways to connect and communicate. The importance of touch has long been recognised in the nursing profession. Massage therapy involves using (primarily) the hands to physically manipulate the body’s soft tissues to effect a desirable change in the individual.62 Massage has been shown to produce therapeutic effects on multiple body systems and a relaxation response that is closely connected to the reduction of pain.4 Nurses may perform therapeutic massage on patients’ backs, hands and feet, and an understanding of basic techniques and strokes, such as effleurage (smooth stokes), kneading and compression (petrissage), can be taught as part of undergraduate nursing programs.

Massage is often combined with other therapies, such as music, aromatherapy and acupressure. This use of multiple therapies is a valuable adjunct for patients, supporting an integrated approach. However, from a research perspective it makes it difficult to differentiate the specific effects of massage from those of the other therapies.4 Although research on the effectiveness of massage therapy is ongoing, limited reliable evidence is available. Studies indicate that massage may be effective in relieving low back pain63 and reducing agitation in patients with dementia.64

CHIROPRACTIC THERAPY

Chiropractic therapy, a manual healing art, was developed in 1895 in the US, although spinal and soft-tissue manipulation has been practised since early recorded history. The primary aim of chiropractic therapy is to restore and maintain health by properly aligning the spine. Correct spinal alignment reduces interference from the nervous system, facilitates self-healing, and improves health and wellbeing. Incorrect spinal alignment, termed subluxation, can result from mechanical, physical or psychological factors, as well as from illness, poor diet or exposure to environmental toxins. After a thorough diagnostic examination, chiropractors use various adjustment and manipulation techniques to facilitate spinal alignment based on the patient’s particular problem. Chiropractic care may be acute, corrective or preventative. Chiropractic practice does not typically include drug therapy or surgery but may include suggestions for improved nutritional intake, massage, podiatry or exercises.4

Clinical applications of chiropractic therapy

Chiropractic therapy is best known for treating back pain. A systematic review has shown that while combined chiropractic interventions slightly improved pain and disability in the short term and pain in the medium term for acute and subacute low back pain, there is currently no evidence to support or refute the claim that combined chiropractic interventions provide a clinically meaningful advantage over other treatments for pain or disability in people with low back pain.65 Future research involving well conducted randomised trials is required to compare combined chiropractic interventions with other established therapies for low back pain. Chiropractic interventions are also used to treat musculoskeletal abnormalities, headaches, dysmenorrhoea, dizziness, tinnitus and visual disorders.

Limitations of chiropractic therapy

Several diseases or joint conditions should not be treated with manipulation. If a malignancy is suspected or determined through diagnostic testing, the patient should be referred to a doctor for further evaluation and treatment. Bone and joint infections also require pharmacological or surgical intervention. Contraindications for chiropractic therapy include acute myelopathy, fractures, dislocations and rheumatoid arthritis. Nerve damage and paralysis are extremely rare complications of chiropractic intervention.

Energy and biofield therapies

Energy and biofield therapies involve the manipulation of energy fields. They focus on energy fields originating within or surrounding the body (biofields) or from other sources (electromagnetic fields). Examples of biofield therapies include therapeutic touch, healing touch and Reiki (see Table 7-1). Biofield healing therapies are based on the theory that energy systems in the body need to be balanced in an effort to enhance healing. Some forms of energy therapy manipulate biofields by applying pressure and/or manipulating the body by placing the hands in, or through, these fields. Evidence is still being sought to explain subtle energy fields, to provide verifiable scientific evidence and to demonstrate how these therapies interact with such fields. Some evidence is being provided through new technologies, such as Kirlian photography and detectors able to detect electromagnetic fields. For example, a study undertaken with a therapeutic touch practitioner showed a signal to pulse at a variable frequency, ranging from 0.3 to 30 Hz, with most activity in the range 7–8 Hz.66,67 This represents a preliminary but important line of investigation into energy medicine.

Creating an optimal healing environment (OHE)—that is, a healing place and space—is being recognised as significant in supporting individual innate healing capacities, and a base of evidence is emerging from a number of disciplines, including nursing, interior design, architecture, neuroscience, psychoneuroimmunology and environmental psychology. Nurses have traditionally been leaders in creating an OHE, with Florence Nightingale recognising the nurse’s role in caring for the patient and managing the physical environment. Nurses need to be informed about how an OHE affects health outcomes so that they can contribute to the design of patient care units and clinical facilities. Neuroscience studies are contributing to the understanding of health outcomes, patient satisfaction and outcomes for staff, including decreased staff stress, increased staff effectiveness and productivity, and satisfaction.4 Sternberg has written about the effects and evidence of view, pattern, colour and light on emotions, stress levels and healing, stating: ‘We can understand how sense perceptions trigger emotions that send molecules flowing through our bloodstream and nerve cells … So we can truly begin to understand how space and place … could turn the tide against illness and speed the course of healing.’68

Today’s nurses are integrating many touch techniques into their practice.69 Two specific energetic touch therapies are therapeutic touch and healing touch.

THERAPEUTIC TOUCH

Therapeutic touch is a method of detecting and balancing human energy (see Fig 7-8). It is a contemporary interpretation of several ancient healing practices. The structure of its current practice was developed in the US in the early 1970s by Dolores Krieger and Dora Kunz and has become known as the Krieger–Kunz method. The Nurse Healers–Professional Associates International Inc. continues to promote and support the development of this method (see the Resources on pp 124–125). In Australia, therapeutic touch education and training are provided by Therapeutic Association of Australasia Inc. (see the Resources on pp 124–125).

Figure 7-8 In therapeutic touch, the practitioner directs and remodulates the energy towards rebalancing the flow and symmetry of the energy field to facilitate the individual’s healing.

Therapeutic touch assumes that the human being is an open energy system, that a balanced flow of energy underlies good health, that illness is a reflection of an imbalance in an individual’s energy field, and that human beings have the innate capacity to transform and transcend their current state of being. Additionally, practitioners assume that anyone can learn therapeutic touch, as long as they have a desire to learn, a willingness to help and a sense of compassion for others. Therapeutic touch is believed to help restore balance in the human energy field, leading to an opportunity for healing that incorporates the whole person. There is a dynamic relationship between the healer and the client and the vital role of expanded levels of consciousness as they relate to the healing process.70

Therapeutic touch involves the conscious use of the hands to direct or modulate human energy fields. Energy imbalances can be identified by the practitioner. During the actual treatment, the practitioner directs and modulates the energy, attempting to rebalance the energy flow and achieve symmetry throughout the energy field. This remodulation of energy is achieved by the practitioner either lightly touching the body or maintaining the hands in a position 5–10 cm away from the body and consciously directing the flow of energy.

Clinical applications of therapeutic touch

The North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA) has accepted the nursing diagnosis ‘energy field disturbance’, for which therapeutic touch is currently the only identified intervention. Research has been conducted on the effectiveness of therapeutic touch for a wide range of conditions, including wound healing, sleep promotion, enhancement of immune functioning, and the reduction of anxiety, agitation, postoperative pain, tension headache and stress.71 Reviews of research on therapeutic touch indicate that findings are inconsistent but clinically important and that further research is warranted.

Limitations of therapeutic touch

Although there is great enthusiasm in nursing about the use of therapeutic touch, its research base needs further development. Scientifically acceptable methods for detecting human energy fields are currently lacking, contributing to a great deal of controversy about the basic assumptions underlying therapeutic touch. There is concern that literature reviews about therapeutic touch may overestimate its effectiveness.72 Researchers widely cite the need for additional well-controlled studies that use consistent definitions of therapeutic touch, consistent intervention practices and larger sample sizes before scientifically sound decisions can be reached about the clinical effectiveness of this therapy.

Although documentation of adverse consequences of therapeutic touch is absent in the research literature, it may need to be modified in certain patient populations who may be sensitive to energy repatterning and who should be exposed only to short and gentle energy-based interventions. Such patients include infants, pregnant women, older or debilitated people and those in unstable mental states or with head injuries.73

HEALING TOUCH

Healing touch is an energy-based approach to health and healing developed by Mentgen and colleagues in 1989. It uses gentle touch and energy-based techniques to ‘influence and support the human energy system within the body (energy centres) and surrounding the body (energy fields)’.74 A certification program for healing touch has been developed by Healing Touch International.74,75 The American Holistic Nurses Association, formed in 1997, endorses Healing Touch International’s certificate programs. The Australian Foundation for Healing Touch is an affiliate of Healing Touch International that administers the healing touch program in Australia (see the Resources on pp 124–125). Revision of the scope of practice for healing touch in 2002 assisted in demonstrating the uniqueness of healing touch compared to its counterpart, therapeutic touch.

Clinical applications of healing touch

Healing touch may be valuable in an integrative approach as many medical procedures, such as surgery, chemotherapy and complex diagnostic testing, produce anxiety in patients, and a simple healing touch technique performed before a procedure can help relax patients.75 A number of techniques are used, from simple to complex and ranging from localised to full body techniques depending on the patient’s needs. Research into this modality is increasing, with a number of studies completed and 33 in progress.69

BIOELECTROMAGNETIC-BASED THERAPIES

Bioelectromagnetics refers to the unconventional use of electromagnetic fields for medical purposes. Magnets have been used to enhance health for thousands of years. Currently, magnetic therapy is widely accepted in China, Japan, Korea, Germany, Switzerland and Russia. In North America, magnetic therapy is becoming more popular, especially with athletes.

Numerous mechanisms have been proposed to explain the effects of magnetic therapy. These include: (1) increasing endorphin levels or blocking pain signals to the brain, thus reducing pain; (2) increasing blood flow, thus enhancing cellular and tissue healing; (3) facilitating the movement of calcium away from arthritic joints and towards areas of need in the body; (4) enhancing enzyme functioning and thus overall functioning of the body; and (5) increasing serotonin levels, thus enhancing a sense of wellbeing. The changes induced by magnetic therapy may be so subtle that they are difficult to assess and measure with current technology.76,77

Permanent magnets are used in a variety of configurations, including the placement of magnets directly over pain sites or specific acupuncture meridians. People may sleep on magnetic pads and mattress covers or wear magnetic bands, belts or insoles in their shoes. Magnetic therapy is also provided as a pulsed electromagnetic field and is used to stimulate the growth of bone and cartilage with potential for the treatment of arthritis.77 A systematic review of acumagnet therapy (using acupuncture points) using six electronic databases reported that 37 of 42 studies that met the criteria found therapeutic benefit, particularly for management of diabetes and insomnia.4 An objective measurement used to indicate changes in the body’s magnetic field is the superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID), a sensitive magnetometer for mapping the magnetic fields around the human body that can detect an increase or a decrease in the biomagnetic field.66

Clinical use of magnetic therapy

Therapeutic permanent magnets are used most frequently for low back pain and are popular for a variety of other musculoskeletal complaints, although results of studies on the effectiveness of magnet therapy are inconsistent.76 Findings may be inconsistent because the optimal length of treatment time and the optimal strength of the magnetic field have not been determined.

Limitations of magnetic therapy

No adverse consequences have been documented from the use of magnetic therapy. People with metal plates and screws and with implanted devices, such as defibrillators and pacemakers, should avoid exposure to magnetic fields. People with seizure disorders and bleeding disorders are advised to avoid using magnet therapy without proper medical supervision.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

NURSING MANAGEMENT: COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

The role of the nurse with respect to CATs is evolving. This role may include: (1) assessing patients’ use of CATs and their risk of complications or adverse interactions with conventional therapies; (2) serving as a resource about CATs, including teaching patients about complementary and alternative options, providing information about evidence concerning effectiveness, and making referrals to qualified practitioners; (3) serving as a provider of therapies for which the nurse obtains training and certification, such as therapeutic touch, healing touch or aromatherapy; and (4) conducting research about complementary and alternative approaches. These endeavours will contribute to and, in turn, be enhanced by the evolving theoretical shift originally evident in the contributions of prominent nursing theorists such as Martha Rogers (1970), Jean Watson (1988) and Margaret Newman (1994).78 These three theorists proposed the core values of a holistic approach: nurse–client–environment interconnectedness, consciousness as a force and the primacy of the healing relationship. The use of CATs can be the support and tools alongside this practice.

In Australia, with the commencement of the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme in 2010, the states’ Nurses and Midwives Boards were replaced by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA), which is responsible for the registration and accreditation of 10 health professions across Australia. When these state boards ceased to operate, so too did the previous guidelines and standards for the use of complementary therapies in nursing. Currently, there is no information from the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia regarding guidelines on the use of complementary therapies in nursing and midwifery practice, but the Royal College of Nursing Australia and the Australian Nursing Federation provide a position statement and guideline, respectively.79,80 In New Zealand, the policy of the College of Nurses Aotearoa (NZ) Inc. supports the use of complementary therapies by nurses as part of their overall nursing practice in hospital or community settings.81 The Royal College of Nursing (UK) guidelines cite professional codes of conduct, indicating that the use of any complementary therapy must always be in the best interests of the patient and that informed consent must be obtained.82 Consequently, guidelines for practice have become limited.

Nurses can have an influence on the development of standards and clinical guidelines related to complementary therapies to ensure safety and promote a culture of holistic care. As nurses seek to include complementary and alternative approaches in their practice, questions that must be addressed include the following:

1. What institutional or workplace policies must be in place to support the use of complementary and alternative approaches?

2. What are the liability issues affecting complementary therapy practice? What are the basic risk management strategies that minimise exposure to legal challenges? What consent or permission from patients is necessary before complementary or alternative approaches are used?

3. What monitoring or evaluation systems should be instituted to document the use and effectiveness of such interventions?

4. What qualifications, professional indemnity insurance and affiliation with an appropriate professional body (that produces a code of ethics) is required for practitioners/staff/nurses who offer CAT?17,83

Assessment

Assessment

It is important for patients to inform healthcare practitioners of their use of alternative approaches and for nurses to recognise that patients may be reluctant to report such usage. Extrapolation from other Western populations suggests that significant numbers of Australians and New Zealanders may be at risk of prescription drug–herb interactions. In addition to assessment of drug–herb interactions, it is important to assess patients’ risk of untoward effects and to document the effectiveness of those interventions being used. The incorporation of complementary and alternative approaches in the plan of care may also be appropriate, given a patient’s current use of or interest in these strategies.

In assessing the use of complementary and alternative approaches, the degree of use must first be determined. In one study, Shorofi and Arbon found that although 24.4% of patients rated themselves as having no knowledge of CAMs and 42.5% said they had very little knowledge, 46.4% had a positive attitude towards CAMs.21 Patients with a desire to be actively involved in their healthcare or who desire an approach to healthcare that includes emotional and spiritual aspects are likely to use complementary or alternative approaches. Specific problems for which patients use complementary and alternative approaches include addiction problems, anxiety, chronic pain, chronic fatigue syndrome, chronic urinary tract infections, headaches, and sprains or muscle strains.21 These problems are often resistant to treatment with conventional therapies. Assessment questions to ask the patient include the following:

1. What are you doing to maintain or improve your health and wellbeing?

2. How involved are you in planning and carrying out your health-related care?

3. What is your view of the ideal relationship between yourself and your primary healthcare provider?

4. Do you have any conditions or health concerns that have not responded to conventional medicine? If so, have you tried any other approaches?

5. Are you using any vitamin, mineral, dietary or herbal supplements or other therapy approaches?

6. Are you interested in obtaining information about alternative or complementary approaches?84,85

Asking these questions in a way that conveys respect for the patient and genuine interest in their answers will be most effective in eliciting information. The nurse can then determine whether the patient is a non-user, an occasional user or a primary user. Patients who are non-users but open to CAMs may like to receive further information. Nurses work closely with patients and are in the unique position of becoming familiar with patients’ spiritual and cultural values and beliefs. Nurses may be able to determine which CATs would be more appropriate to a patient’s values and beliefs and offer recommendations accordingly.

Patients who are identified as occasional or primary users should have their knowledge assessed regarding the therapies they are using, including the extent of their knowledge and the sources of information they use. This will enable a determination to be made as to whether the patient is adequately informed and has reliable sources of information. Additionally, the nurse should document the effectiveness and any unexpected or adverse consequences of the intervention. Patients should also be assessed for risk related to their use of these therapies. Known high-risk therapies include those involving unsafe herbs and there are also potential adverse interactions when some herbs are used concurrently with prescribed drug (see Table 7-2). Surgery may create short-term risks related to interactions of herbal therapies. Other high-risk therapies include those that are high in cost but provide low-to-uncertain benefits, as well as those that mask potentially life-threatening conditions or substitute for effective conventional therapies in life-threatening conditions.

Patients identified as being at high risk of complications related to the use of CATs must have a specific plan developed to inform them and other healthcare providers of their risk status. While recognising that patients have the ultimate responsibility for decisions on the use of therapies, they need to be clearly and fully informed about the potential adverse consequences of their use of CATs. Documentation of high-risk status must be included in patient records and communicated to other healthcare providers.

Serving as a resource

Serving as a resource

To serve as a resource for patients, nurses must first develop their own knowledge base. Even if specific information about CATs is not provided in nursing programs, nurses are educated as critical thinkers and problem solvers. Thus, nurses are prepared to seek ongoing education regarding CATs and to continue to read and critique research conducted on such therapies. It is important for nurses to be aware of the current research being done in this area so that they can provide accurate information to both patients and other healthcare professionals. Bright sums this up very appropriately:

Conventional practitioners are also participating in the expression of CAM: referrals to CAM therapies are frequently made by such practitioners. We can expect to see this trend in health care continue. Practitioners must assume responsibility of becoming informed about complementary and alternative practices in which their clients engage, so they can:

• be credible and trustworthy sources of information and guidance

• be alert to potential adverse interactions between conventional and CAM treatments

• communicate with other health professionals and coordinate care

• facilitate an integration of all health-related activities in partnership with the client.78

Most of the information available at present to the general public regarding CATs comes through the media. Although some media articles may provide balanced information, others present CAMs as offering a ‘magical cure’, and it is imperative that nurses present a balanced message that is based on evidence-based consensus of best clinical practice and guidance on healthier lifestyles.86 Resources for complementary and alternative approaches have dramatically increased with the development of the internet, and examples of internet resources are included on pp 124–125. Nurses should be prepared to assist patients in differentiating between internet sites that promote untested approaches and those that include systematically reviewed information. Knowledge of internet sites or other listings that include information about local practitioners of various therapies who are certified, registered or licensed is also useful.

Serving as a provider

Serving as a provider

Nursing has a long history of providing therapies that have been considered complementary and alternative within the context of contemporary biomedical approaches to health. These include massage, relaxation therapy, music therapy, therapeutic touch and, more recently, healing touch, as well as other strategies to promote comfort, reduce stress, improve coping and promote symptom relief. These and other complementary therapies are generally included within the scope of nursing practice, although they are not specifically addressed in Australian nursing practice Acts. The requirements for use of CATs are no different from those for the use of other nursing interventions. The nurse should have specific training in the use of the therapy and should be aware of the evidence base that addresses the conditions for which the therapy is indicated, the effectiveness of the therapy and the potential for adverse outcomes or synergistic effects. The nurse’s reasons for undertaking this training—for example, using such therapies in conjunction with nursing skills, developing a new career or enhancing self-awareness—will influence the type and level of course undertaken. Training providers include private colleges or training institutes, colleges of further education and universities, and it is useful to investigate what the professional organisations for the therapy recognise or accredit. Hover-Kramer and Murphy note that ‘because of the subtleties implied in our innovative practices, there are many possible areas where misinterpretation by clients and perceived overstepping of boundaries can occur’.86 Careful understanding of the use of CAM assists in giving credibility to these therapies, particularly if guidelines are provided and acknowledged within a code of ethics produced by the relevant CAM associations.

Involvement in research

Involvement in research

The lack of an established evidence base in complementary therapies is viewed as a major obstacle to the inclusion and integration of these therapies into mainstream healthcare. There continue to be issues and debates associated with the practice of evidence-based medicine and what constitutes ‘evidence’.86 While these debates need to continue, this does not mean that therapies should be rejected purely due to poor research or inappropriate design, especially if this was carried out a number of years ago.87 Further work in the development of suitable outcome measures is needed so that the full benefits experienced by users of complementary therapies can be properly evaluated. These outcome measures should reflect symptomatic as well as curative treatments, and they should be developed in close consultation with practitioners, researchers and users.