Chapter 52 NURSING MANAGEMENT: sexually transmitted infections

1. Identify the factors contributing to the high incidence of sexually transmitted infections.

2. Explain the aetiology, clinical manifestations, complications and diagnostic abnormalities of gonorrhoea, syphilis, Chlamydia infections, genital herpes and genital warts.

3. Compare primary genital herpes to recurrent genital herpes.

4. Explain the multidisciplinary care and drug therapy of gonorrhoea, syphilis, Chlamydia infections, genital herpes and genital warts.

5. Identify nursing assessments and nursing diagnoses for patients who have sexually transmitted infections.

6. Discuss the nursing role in the prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections.

7. Describe the nursing management of patients with sexually transmitted infections.

Sexually transmitted infections

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are infections most commonly transmitted through sexual contact (see Table-52-1). Historically they have been referred to as venereal diseases or sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). In 1999 the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that the term sexually transmitted diseases be replaced with the term sexually transmitted infections as the latter term better incorporates asymptomatic infections and recognises recent scientific research outcomes.1

TABLE 52-1 Microorganisms responsible for infections transmitted by sexual activity

| Organism | Disease |

|---|---|

| Chlamydophila trachomatis | Non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU);cervicitis; lymphogranuloma venereum |

| Cytomegalovirus (CMV) | Multiple diseases |

| Hepatitis B virus | Hepatitis B |

| Herpes simplex virus (HSV) | Genital herpes |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | HIV infection, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) |

| Human papillomavirus | Genital warts |

| Poxvirus | Molluscum contagiosum |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Gonorrhoea |

| Treponema pallidum | Syphilis |

STIs can be bacterial (gonorrhoea, Chlamydia, syphilis) and/or viral (genital herpes, genital warts). Most infections start as lesions on the genitalia and other sexually exposed mucous membranes. Wide dissemination to other areas of the body can then occur. A latent or subclinical phase is present with all STIs, which can lead to a long-term persistent infection and the transmission of disease from an asymptomatic (yet infected) person to another contact. Different STIs can coexist within one person. For example, if a person has gonorrhoea, a Chlamydia infection may also be present. Many of the agents causing STIs are easily inactivated by drying, heating and washing.

In Australia, communicable diseases are reported to the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) through notification by the states and territories to the Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing. The STIs classified nationally for surveillance, in addition to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and hepatitis B and C, are: syphilis, donovanosis, gonorrhoea and Chlamydia.2 In New Zealand, most STIs are not notifiable and statistical data come from regional sexual health clinics, which submit STI surveillance data to the Institute of Environmental Science and Research.3 These clinic types are sexual health clinics (SHCs), family planning clinics (FPCs) and student youth health centres (SYHCs).3

Diseases that are associated with sexual transmission can also be contracted by other routes including blood, blood products and autoinoculation.

The more commonly diagnosed STIs are discussed in this chapter. HIV infection and related problems are discussed in Chapter 14, and hepatitis B infection and related problems are discussed in Chapter 43.

FACTORS AFFECTING INCIDENCE OF SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS

Many factors contribute to current STI rates. Earlier reproductive maturity and increased longevity have resulted in a longer sexual life span. The increase in the total population has resulted in an increase in the number of susceptible hosts. Other factors include greater sexual freedom, the changing roles of women, decreased social control by religious institutions, increases in the number of people screened, improved sensitivity of diagnostic tests1 and an increased emphasis on sexuality in the media. In addition, increased leisure time, inexpensive travel and urbanisation have brought together people with varying social behaviours and value systems. The complexity inherent in the interactions between cultural and social determinants and how diseases cluster, particularly STIs, has been referred to as syndemics.4

Changes in methods of contraception are also reflected in the incidence of STIs. The condom is considered to be the only contraceptive device that is prophylactic against STIs; however, it is important to emphasise its role in risk reduction as opposed to prevention of STIs.5 Although condom use has been historically higher in selected populations, such as those with a previous history of STIs and men who have sex with men, they are not used frequently in the general population. Despite this, an alarming trend is being seen in men who have sex with men, whereby unprotected anal intercourse is more likely in venues such as bars and saunas.6 In one study, Flores and colleagues found that one-third of their research respondents had unprotected anal sex.6 However, it is in the general population where the knowledge of routes of transmission for STIs is found to be poor.

Commonly used oral contraceptives cause the secretions of the cervix and the vagina to become more alkaline. This change produces a more favourable environment for the growth of organisms that cause STIs at these sites. Women who take oral contraceptives have a lower risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) as a result of the ability of the cervical mucus to act as a barrier against bacteria. However, the proliferation of Chlamydia, the leading cause of non-gonococcal PID, may be enhanced by oral contraceptive use. Whether or not intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD) users are at increased risk of PID is controversial, but it is clear that IUCDs confer no protection against STIs.5 Use of long-acting contraceptives, such as levonorgestrel and medroxyprogesterone, has been shown to lower the concurrent use of condoms, even among women with risk factors for STIs.5 Both levonorgestrel and medroxyprogesterone confer no protection against STIs. Lack of awareness of this fact may be a factor leading to STIs in people using these products.

Gonorrhoea

The incidence of gonorrhoea varies between different groups in the population, and recently in Australia there has been a stabilising of infection rates, although incidence varies between the states and territories.2 Trends in sex-specific rates show a general increase in infection rates in people aged between 15 and 29 years: the greatest increase is in males aged 15–19 years and 25–29 years.7 The highest incidence of gonorrhoea in New Zealand is seen mainly in those aged less than 20 years and in the 20–24-year age group.8 Although not as prevalent as Chlamydia, the diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae is increasing at a greater rate, and Māori accounted for more cases of gonorrhoea diagnosed in sexual health clinics than any other ethnic group.3 Overall, there seems to be increasing complacency about ‘safe sex’ and increasing high-risk behaviours, such as multiple and concurrent partners and inconsistent condom use. These behaviours are likely to see an inevitable rise in the transmission of this infection. There is some evidence that the disease may be increasing in the population of men who have sex with men, which is thought to be related to complacency about the need to use ‘safe sex’ precautions.2,3

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Gonorrhoea is caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a Gram-negative diplococcus. The disease is spread by direct physical contact with an infected host, usually during sexual activity (vaginal, oral or anal). Mucosa with columnar epithelium is susceptible to gonococcal infection. This tissue is present in the genitalia (urethra in men, cervix in women), the rectum and the oropharynx. Neonates can develop a gonococcal infection during delivery from an infected mother. The delicate gonococcus is easily killed by drying, heating or washing with an antiseptic solution. Consequently, indirect transmission by instruments or linen is rare. The incubation period is 3–4 days. The disease confers no immunity to subsequent reinfection. Gonococcal infection elicits an inflammatory response, which, if left untreated, leads to the formation of fibrous tissue and adhesions. This fibrous scarring is subsequently responsible for many complications, such as strictures and tubal abnormalities, which can lead to tubal pregnancy, chronic pelvic pain and infertility.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The initial site of infection in heterosexual men is usually the urethra. Symptoms of urethritis consist of dysuria and profuse, purulent urethral discharge developing 2–5 days after infection (see Fig 52-1). Painful or swollen testicles may also occur. Men generally seek medical evaluation early in the disease because their symptoms are usually obvious and distressing. It is unusual for men with gonorrhoea to be asymptomatic.

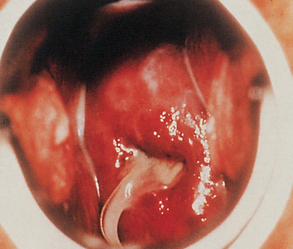

Most women who contract gonorrhoea are asymptomatic or have minor symptoms that are often overlooked, making it possible for them to remain a source of infection. A few women may complain of vaginal discharge, dysuria or frequency of urination. Changes in menstruation may be a symptom but these changes are often disregarded by the woman. After the incubation period, redness and swelling occur at the site of contact, which is usually the cervix or urethra (see Fig 52-2).

A purulent exudate often develops with a potential for abscess formation. The disease may remain local or can spread by direct tissue extension to the uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries. Although the vulva and vagina are uncommon sites for a gonorrhoeal infection, they may become involved when little or no oestrogen is present, as is the case in prepubertal girls and postmenopausal women. Because the vagina acts as a natural reservoir for infectious secretions, transmission is often more efficient from men to women than it is from women to men.

Anorectal gonorrhoea may be present and is usually caused by anal intercourse. Symptoms may include soreness, itching and discharge. Most patients with rectal infections or infections in the throat have few symptoms. A small percentage of individuals develop gonococcal pharyngitis resulting from orogenital sexual contact. When the gonococcus can be demonstrated by a laboratory culture, individuals of either gender are infectious to their sexual partners.

COMPLICATIONS

Men often seek treatment early in the course of the disease, so they are less likely to develop complications. The complications that do occur in men are prostatitis, urethral strictures and sterility from orchitis or epididymitis. Because women who are asymptomatic seldom seek treatment, complications are more common and usually constitute the reason for seeking medical attention. PID, Bartholin’s abscess, ectopic pregnancy and infertility are the main complications of gonorrhoea in women. A small percentage of infected people, mainly women, may develop a disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI). In DGI the appearance of skin lesions, fever, arthralgia or arthritis usually causes the patient to seek medical help (see Fig 52-3).

Figure 52-3 Disseminated gonococcal infection. Skin lesion with grey, necrotic centre on erythematous base.

Eye infections in newborns

Gonorrhoeal eye infections in newborns (ophthalmia neonatorum) can be prevented by careful cleaning of the infant’s eyes immediately after birth with 1% silver nitrate or 1% tetracycline ointment. WHO recommends that infants born to mothers with gonococcal infection should also receive additional treatment with ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg by intramuscular injection (IMI) or spectinomycin 25 mg/kg IMI.1 Untreated infected infants develop permanent blindness.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The immediate identification of N. gonorrhoeae is usually made with a Gram stain of smears made from the exudate. The slides should be interpreted by an experienced technician so that a correct diagnosis is made initially, because some patients fail to return for follow-up care. A reliable way to confirm gonococcal infection is to isolate the organism in culture. Cultures of the discharge or secretion can provide a definitive diagnosis after incubation for 24–48 hours. Urethral discharge is collected on a Dacron- or rayon-tipped swab and an air-dried smear is made before the specimen is placed into a modified Stuart’s transport medium. If an air-dried smear cannot be prepared, the laboratory staff member prepares one from the swab placed in the transport medium, although a smear made at the time of specimen collection is of a superior quality.

For men, a presumptive diagnosis of gonorrhoea is made if there is a history of sexual contact with a new or infected partner followed within a few days by a urethral discharge. Typical clinical manifestations, combined with a positive finding in a Gram-stained smear of the purulent discharge from the penis, give an almost certain diagnosis. A culture of the discharge is indicated for men whose smears are negative in the presence of strong clinical evidence.

Making a diagnosis of gonorrhoea in women on the basis of symptoms is difficult because most women are symptom-free or have complaints that may be confused with other conditions. Smears and purulent discharge do not establish a diagnosis of gonorrhoea because the female genitourinary tract normally harbours a large number of organisms that resemble N. gonorrhoeae. A culture must be performed to confirm the diagnosis. Although the cervix is the most common site of sampling, specimens for culture may also be taken from the urethra, anus or oropharynx to confirm the diagnosis. It is generally recommended that a proctoscope be used when taking a rectal swab for detecting gonorrhoea, as rectal swabs taken without a proctoscope are of little value in detecting gonorrhoea or Chlamydia.

A newer technique, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) amplification using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or ligase chain reaction (LCR), is being used to diagnose gonorrhoea. (PCR is discussed in Ch 13.) This testing technique does not involve culture and is a quicker approach to detecting infection. DNA amplification has a high rate of sensitivity and specificity. The test can be performed on urine, vaginal fluid or discharge, or urethral secretions. This eliminates the need for a urethral swab in male patients and potentially the necessity for pelvic examination in female patients.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Drug therapy

Due to the short incubation period and high infectivity, treatment is generally instituted without awaiting culture results, even in the absence of any signs or symptoms. The treatment of gonorrhoea in the early stage is curative. Traditionally, the drug of choice for gonorrhoeal therapy was penicillin, but changes have been made because of resistant strains of N. gonorrhoeae. As a result, ceftriaxone, a penicillinase-resistant cephalosporin, ciprofloxacin or spectinomycin has become part of the treatment plan (see Box 52-1).

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Collaborative therapy

Recommended regimens

Ceftriaxone 125 mg IM in a single dose OR cefixime 400 mg orally in a single dose or 400 mg by suspension (200 mg/5 mL)*

If Chlamydia infection is not ruled out: azithromycin 1 g orally in a single dose or doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 7 days

Patients who are allergic to cephalosporins or quinolones should be treated with spectinomycin

Patients who have gonorrhoea and who are treated with any of the above therapies need to be followed up within 48 hours and return to confirm that they are cured 5–7 days after treatment

Source: Modified from Centres for Disease Control. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. Available at www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/STD-Treatment-2010-RR5912.pdf; and World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the management of sexually transmitted infections. Geneva: WHO; 2003. Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241546263.pdf.

*These regimens are recommended for all adult and adolescent patients, regardless of travel history or sexual history.

Resistance to the quinolones, such as ciprofloxacin, has been reported as a major problem in many parts of the Western Pacific region.9 In many parts of Australia the use of quinolones has been discontinued due to the high levels of resistance.10 In addition, there has been an increase in the number of decreased-susceptibility gonococci being reported. The high frequency (up to 20% in men and 40% in women) of coexisting Chlamydia and gonococcal infections has led to the addition of azithromycin and doxycycline to the treatment regimen. As a result, current guidelines recommend patients who have comorbid Chlamydia receive anti-Chlamydia treatment concurrently.11 Patients with coexisting syphilis are likely to be cured by the same drugs used for gonorrhoea.

All sexual contacts of patients with gonorrhoea must be evaluated and treated to prevent reinfection after resumption of sexual relations. The ‘ping-pong’ effect of re-exposure, treatment and reinfection can cease only when infected partners are treated simultaneously. Additionally, the patient should be counselled to abstain from sexual intercourse and alcohol during treatment. Sexual intercourse allows the infection to spread and can delay complete healing. Alcohol has an irritant effect on the healing urethral walls. Men should be cautioned against squeezing the penis to look for further discharge. Follow-up examination and repeat culture should be done at least once after treatment, usually in 5–10 days. Reinfection, rather than treatment failure, is the main cause for infections identified after treatment has ended.

Syphilis

Until the beginning of the 21st century, the incidence of syphilis seemed to be stable or dropping. However, since 2004, increases in infection rates have been reported in Australia.7 Although the overall number of cases of syphilis in New Zealand remains low compared to other STIs, case numbers have more than doubled in the past five years.3 Eighty per cent of reported cases involve males of European descent with a mean age of 40 years, with the majority of cases being in men who have sex with men.3 Syphilis remains an important health problem and is more prevalent among Indigenous communities, with syphilis notification rates being the highest between the ages of 15 and 29 years.12 Syphilis notification rates have been found to be much higher for Indigenous people living in remote and very remote areas than for those living in major cities and inner and outer regional areas. For non-Indigenous people, notification rates tend to be highest in major cities and in very remote areas.12

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The causative organism of syphilis is Treponema pallidum, a spirochaete. This bacterium is thought to enter the body through very small breaks in the skin or mucous membranes. Its entry is facilitated by the minor abrasions that often occur during sexual intercourse.13 Syphilis is a complex disease in which many organs and tissues of the body can become infected by T. pallidum. The infection causes the production of antibodies, which also react with normal tissues. After a short period of protection, the antibody levels decrease and the person is susceptible to reinfection.14 Not all people who are exposed to syphilis acquire the disease; about one-third become infected after intercourse with an infected person. In addition to sexual contact, syphilis may be spread through contact with infectious lesions and sharing of needles among intravenous (IV) drug users. T. pallidum is extremely fragile and is easily destroyed by drying, heating or washing. The incubation period for syphilis ranges from 10 to 90 days (average 21 days). Congenital syphilis is transmitted from an infected mother to the fetus in utero after the tenth week of pregnancy. The infant death rate is up to 40% in women who have untreated syphilis.15

People with untreated syphilis tend to be young and of low educational and socioeconomic level, with limited access to healthcare. There is an association between syphilis and HIV infection.16 Those at high risk of acquiring syphilis are also at an increased risk of acquiring HIV. Often, both infections may be present in the same person. The presence of syphilitic lesions on the genitals enhances HIV transmission. HIV-infected patients with syphilis appear to be at greatest risk of clinically significant central nervous system (CNS) involvement and may require more intensive treatment with penicillin than do other patients with syphilis. Therefore, the evaluation of all patients with syphilis should also include testing for HIV (with the patient’s consent).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

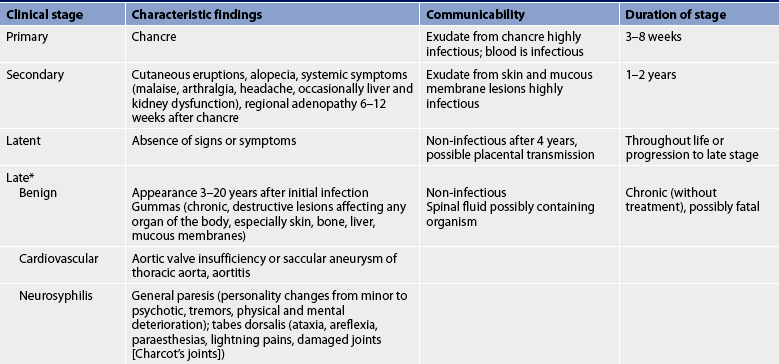

Syphilis has a variety of signs and symptoms that can mimic those of a number of other diseases. Consequently, compared to other STIs, it is more difficult to recognise syphilis. If it is not treated, specific clinical stages are characteristic of the progression of the disease (see Table 52-2).

* Several forms, such as cardiovascular and neurosyphilis, occur together in approximately 25% of untreated cases.

In the primary stage of the bacterial invasion (see Fig 52-4), chancres appear. These are painless indurated lesions on the penis, vulva, lips, mouth, vagina and rectum. They frequently occur 10–90 days after inoculation. The chancre lasts 3–6 weeks, eventually healing on its own. During this time, the draining of the microorganisms into the lymph nodes causes regional lymphadenopathy. Genital ulcers may also be present. Without treatment the infection progresses to the secondary stage.

The secondary stage is systemic. The stage begins a few weeks after the chancres are first seen. During this stage blood-borne bacteria spread to all major organ systems. Manifestations that are characteristic of the secondary stage can include cutaneous eruptions, fever, alopecia (hair loss), sore throat, headaches, weight loss, tiredness and generalised adenopathy. The cutaneous eruptions include a bilateral, symmetrical rash usually involving the palms and soles (see Fig 52-5); mucous patches in the mouth, tongue or cervix; and condylomata lata (moist, weeping papules) in the anal and genital area.

The latent or hidden stage follows the secondary stage and is a period during which the immune system is able to suppress the infection. The latent stage can be further divided into an early stage, in which the infection has been acquired in the preceding year, and a late stage, in which the infection has been present for more than 1 year. There are no signs or symptoms of syphilis during this time. During the latent stage, the diagnosis is established by a positive specific treponemal antibody test for syphilis together with a normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination and the absence of clinical manifestations on physical examination and chest X-rays. About 70% of untreated patients with latent syphilis never develop clinically evident, third-stage syphilis, but the occurrence of a spontaneous cure of syphilis is doubtful.14

The third stage (also called late or tertiary syphilis) is the most severe stage of the disease. Because antibiotics can cure syphilis, manifestations of late syphilis are rare. However, when it does occur, it causes significant morbidity and mortality. The pathogenesis of the manifestations of this stage is unclear. Gummas (destructive skin, bone and soft-tissue nodular lesions associated with late syphilis) are probably caused by a severe hypersensitivity reaction to the microorganism. Within the cardiovascular system, late syphilis may cause aneurysms, heart valve insufficiency and heart failure. Within the CNS the presence of T. pallidum in CSF may cause manifestations of neurosyphilis (general paresis; see Table 52-2).

COMPLICATIONS

Complications of the disease occur mostly in late syphilis. The gummas of benign late syphilis may produce irreparable damage to bone, liver or skin but seldom result in death. In cardiovascular syphilis, the resulting aneurysm may press on structures such as the intercostal nerves, causing pain. The possibility of a rupture exists as the aneurysm increases in size. Scarring of the aortic valve may result in aortic valve insufficiency and eventually in heart failure.

Neurosyphilis is responsible for degeneration of the brain with mental deterioration. Evidence of other neurological deficits may be present. Problems related to sensory nerve involvement are a result of tabes dorsalis (progressive locomotor ataxia). There may be sudden attacks of pain anywhere in the body, which can confuse the diagnosis with other conditions. Loss of vision and sense of position in the feet and legs can also occur. Walking may become even more difficult as joint stability is lost. (Late syphilis is also discussed in Ch 58.)

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The first step in diagnosis is to obtain a detailed and accurate sexual history. A physical examination should be done to identify any suspicious lesions, as well as to note other significant signs and symptoms.

The presence of spirochaetes on dark-field microscopy and direct fluorescent antibody tests of lesion exudate or tissue can confirm a clinical diagnosis of syphilis. However, syphilis is more commonly diagnosed by a serological test. Tests for syphilis may be classified as those performed for screening and those performed for confirmation of a positive screening test. Non-specific anti-treponemal antibodies can be detected by tests such as the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test and the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. These non-treponemal tests are suitable for screening purposes and usually become positive 10–14 days after the appearance of a chancre. The fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-Abs) test and the microhaemagglutination (MHA) test detect specific anti-treponemal antibodies and are suitable for confirming the diagnosis.

False-negative and false-positive test results do occur with the non-treponemal tests (VDRL, RPR). A false-negative test result may be obtained in cases of primary syphilis if the test is done before the individual has had time to produce antibodies. A false-positive finding may occur with other diseases or conditions such as hepatitis, infectious mononucleosis, after smallpox vaccination, collagen diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus), pregnancy or ageing. Positive non-treponemal test results should be confirmed by more specific treponemal tests to rule out other causes. In the CSF, changes such as increased white blood cell count, increased total protein and a positive treponemal antibody test are diagnostic of asymptomatic neurosyphilis.

If a patient is treated with antibiotics early in the course of the disease on the basis of the history and the symptoms, serological testing may not indicate the presence of syphilis. Once a person has positive serological findings for syphilis, indicating the presence of antibodies, these findings may remain positive for an indefinite period in spite of successful treatment.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Drug therapy

Management of syphilis is aimed at eradication of all syphilitic organisms (see Box 52-2). However, treatment cannot reverse damage that is already present in the late stage of the disease. Benzathine penicillin G or aqueous procaine penicillin G remain the treatment of choice for all stages of syphilis. To date, after four decades of use, there is no evidence to suggest a decrease in the effectiveness of penicillin against T. pallidum. Table 52-3 describes therapy for the various stages of syphilis, based on WHO guidelines for the management of STIs.1 All stages of syphilis should be treated. Patients having persistent or recurring symptoms after drug therapy has ended should be retreated.11,13,14 All patients with neurosyphilis must be carefully monitored for many years with periodic serological and CSF testing, and clinical and radiological examinations. Specific management is based on the symptoms.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Collaborative therapy

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Source: Modified from Centers for Disease Control. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. Available at www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/STD-Treatment-2010-RR5912.pdf.

| Stage | Type of penicillin | Other antibiotics* |

|---|---|---|

| Early syphilis (primary, secondary and early latent) | 2.4 million IU IM of penicillin G benzathine (Bicillin) in a single dose | Doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 14 days, or tetracycline 500 mg orally four times a day for 14 days |

| Alternative regimen | 1.2 million IU of Bicillin IM daily for 10 consecutive days | |

| Late latent syphilis | 2.4 million IU of Bicillin given as three doses of 1.8 g IM of Bicillin each at 1-week intervals OR 1.2 million IU of procaine benzylpenicillin IM daily for 20 consecutive days | Doxycycline or tetracycline given for 30 days at same dosage/routes as for early syphilis |

| Tertiary syphilis | ||

| Gumma, cardiovascular | Same as for retreatment and late latent stage | Same as for late latent stage |

| Neurosyphilis | Aqueous benzylpenicillin 12–24 million IU IV daily given as 2–4 g every 4 h for 14 days | Procaine penicillin 1–2 g IM once daily plus probenecid 500 mg orally four times a day; both drugs given for 10–14 days |

IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous.

*Given when penicillin is contraindicated.

Source: modified from Centers for Disease Control. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. Available at www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/STD-Treatment-2010-rr5912.pdf; and World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the management of sexually transmitted infections. Geneva: WHO; 2003. Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241546263.pdf.

Appropriate penicillin treatment according to the stage of syphilis before the 18th week of pregnancy prevents maternal transmission to the fetus. Appropriate treatment after 18 weeks of pregnancy usually cures both mother and fetus because the antibiotics can cross the placental barrier. Treatment administered in the second half of pregnancy may pose a risk of premature labour and fetal distress. Some authorities recommend hospitalisation and fetal monitoring of women at 20 weeks of gestation or greater.15,16

Chlamydia infections

Chlamydia infections are the most reported STIs in Australia and New Zealand, and are far more common in Indigenous populations than in non-Indigenous ones.11 Notifications of Chlamydia infections in Australia increased by 65% between 2002 and 2005.2 Most infections tend to occur in people under 25 years of age: mainly males aged between 20 and 24 years and females aged between 15 and 19 years.3 In New Zealand there was a 6.5% decrease in the number of reported cases in 2009.3 However, Māori and Pacific Islanders have twice the infection rate of the European population.8 Underreporting is substantial because most people are asymptomatic and do not seek testing. Chlamydia infections are a major contributor to PID, ectopic pregnancy and infertility among women, and non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU) and epididymitis in men.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Chlamydia infections are caused by Chlamydophila trachomatis (previously known as Chlamydia trachomatis), a Gram-negative bacterium. Chlamydia can be transmitted during vaginal, anal or oral sex. Numerous different serotypes, or strains, of C. trachomatis cause urogenital infections (e.g. NGU in men and cervicitis in women), ocular trachoma and lymphogranuloma venereum. Women with Chlamydia infections during the second week of pregnancy are two to three times more likely to have a premature birth.16 While strong links have been found to exist between STIs in pregnant women and preterm and low-birth-weight infants, the links with C. trachomatis are uncertain. In addition, treatment for the condition was not found to be associated with any decrease in second trimester births.16 However, it is recommended that at-risk women be screened when pregnant.

Chlamydia infection is largely underreported because most people infected are asymptomatic and do not seek healthcare. By age 30 years, it is estimated that at some time during their lives 50% of all sexually active women have had a Chlamydia infection. Women with Chlamydia infection may also be at higher risk of acquiring HIV from an infected partner.

CLINICAL PRACTICE

Situation

A nurse in a clinic gives the positive results of a test for Chlamydia to a patient and advises him to tell his sexual partners that he has this disease. The patient refuses to tell his wife because she will know that he has had sex with another partner. Should the nurse contact the wife?

Important points for consideration

• Nurses and other healthcare professionals have both a legal and an ethical obligation to maintain confidentiality of patient information. If confidentiality is violated, trust is eroded and patients may not share privileged information that is essential to planning effective care.

• Healthcare providers have an obligation to maintain confidentiality unless there is a risk to the health or life of innocent third parties. Each jurisdiction has requirements for reporting communicable diseases and other health-related data.

• The nurse’s primary obligation is to the patient seeking care. However, there are long-term health consequences for this patient, as well as the public in general.

• Patient teaching is one way to establish a partnership with this man. Information should be shared about the effects of the disease being untreated, the consequences of reinfection and the results that the disease may have on others who may not know they are infected. The patient can then be encouraged to inform his partners of the diagnosis for the good of everyone.

Because Chlamydia infections are closely associated with gonococcal infections, clinical differentiation may be difficult. Both infections are usually treated concurrently, even without diagnostic evidence. (Box 52-1 describes the multidisciplinary care for gonococcal infection and Box 52-3 describes the multidisciplinary care for Chlamydia.)

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Collaborative therapy

Doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 7 days or azithromycin 1 g in a single dose

Alternative regimen: erythromycin, ofloxacin or levofloxacin

Instruction on abstinence from sexual intercourse for 7 days after completing treatment

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; STIs, sexually transmitted infections.

The incubation period of 1–3 weeks for Chlamydia infection is longer than that for gonorrhoea and the symptoms are often milder. The high incidence of recurrence may be because of failure to treat the sexual partners of infected persons. Box 52-4 lists the risk factors for Chlamydia infection. Because of the high prevalence of asymptomatic infections, screening of high-risk populations is needed to identify those who are infected.

BOX 52-4 Risk factors for Chlamydia infection

• Women and men aged under 24 years

• New or multiple sexual partners

• Sexual partners who have had multiple partners

• History of Chlamydia infection or other STIs and cervical ectopy

STIs, sexually transmitted infections.

From United States Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydial infection: US Preventative Services Taskforce recommendation statement. Ann Int Med 2007; 147(2):128-134.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Chlamydia infection is known as a silent disease because symptoms may be absent or minor in most infected women and in many men. As with gonorrhoea, infection results in a superficial mucosal infection that can become more invasive. Signs and symptoms in men include urethritis (dysuria, urethral discharge), epididymitis (unilateral scrotal pain, swelling, tenderness, fever; see Fig 52-6) and proctitis (rectal discharge and pain during defecation). Signs and symptoms in women include cervicitis (mucopurulent discharge and hypertrophic ectopy [area that is oedematous and bleeds easily]), urethritis (dysuria, frequent urination, pyuria), bartholinitis (purulent exudate), PID (abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, malaise, abnormal vaginal bleeding, menstrual abnormalities) and perihepatitis (fever, nausea, vomiting, right upper quadrant pain). A large number of women with Chlamydia cervicitis have been found to have a male partner with NGU.

COMPLICATIONS

Complications often develop from poorly managed, inaccurately diagnosed or undiagnosed infections. The infection is often not diagnosed until complications appear. Complications in men may result in epididymitis, with possible infertility and Reiter’s syndrome (a systemic condition characterised by urethritis, conjunctivitis, arthritis and mucocutaneous lesions). Complications in women may result in PID, which can lead to chronic pelvic pain and infertility. To address the continuing increase in Chlamydia infection among adolescents and young adults, a number of health services have developed targeted educational programs about Chlamydia.17

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES AND MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Chlamydia infections in men can be diagnosed by excluding gonorrhoea. The cervical or urethral discharge appears to be less purulent, watery and painful in Chlamydia infections than in gonorrhoea. If no Gram-negative diplococci are found on the Gram-stained smear of male urethral discharge or the sediment of a first-catch urine specimen, a culture for both C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae may be appropriate. If both cultures are negative and signs of inflammation are present (e.g. polymorphonuclear leucocytes on the Gram-stained smear), a diagnosis of NGU Chlamydia infection can be made.

The availability of non-culture tests has allowed the screening and confirmation of diagnoses in both men and women. Direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) tests, enzyme immunoassay (EIA), the PCR test and DNA amplification do not require special handling of specimens and are easier to perform than cell cultures. In addition, they can be done with urine samples rather than urethral and cervical swabs. DNA amplification tests are the most sensitive diagnostic methods available. Another diagnostic test specific to C. trachomatis is the LCR test, which is highly sensitive, with ease of sample collection and handling.18

Drug therapy

When diagnosed, Chlamydia infection can be easily treated and cured. The infection responds to treatment with doxycycline or azithromycin. For doxycycline, the dosage is 100 mg two times a day for 7 days. Azithromycin (1 g in a single dose) offers the advantage of ease of administration and current evidence indicates that it is efficacious for Chlamydia infection.1 Due to the simplicity of the treatment regimen, this has been found to be effective in people with demonstrated poor health-seeking behaviours and treatment compliance. Alternative regimens include erythromycin or amoxycillin. Follow-up care should include advising the patient to return within 1 week after completing the medication and, if the symptoms persist or recur, treating sexual partners and encouraging the use of condoms during all sexual contacts.

LYMPHOGRANULOMA VENEREUM

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is an STI caused by specific strains of C. trachomatis. LGV is rare in New Zealand and Australia and was removed from the NNDSS list in 2001. It remains endemic in other areas of the world, however, including Africa, India, South-East Asia, South America and the Caribbean, and has also spread to Europe and North America.19 The majority of cases are reported in men who have sex with men.19 Up until recently, cases in Australia and New Zealand developed only in people who had contact with the disease in areas where LGV is endemic. However, the first case of LGV detected in a person without a history of overseas travel was diagnosed in a bisexual man in Australia in 2005.20

The strain of C. trachomatis that causes LGV is transmitted through intercourse or through contact with exudate from active lesions. LGV begins as a genital lesion and spreads via the lymph nodes of the genital–rectal areas. It may also spread systemically through the bloodstream and enter the CNS. Penile, vulvar and anal infection can lead to inguinal and femoral lymphadenopathy. Marked inflammation occurs, resulting in necrosis, buboes (greatly enlarged, inflamed lymph nodes), abscesses of inguinal lymph nodes and infection of surrounding tissue. Healing occurs by fibrosis after several weeks or months and can result in chronic scarring, which damages the lymph nodes and disrupts nodal function.

Constitutional symptoms that occur during the stage of regional lymphadenopathy include fever, chills, headaches, meningismus (meningitis-like symptoms), anorexia, myalgia and arthralgia. Complications of untreated anorectal infection include strictures, fissures, constipation, perirectal abscesses and rectovaginal and perianal fistulas. LGV is generally treated with doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 14–21 days. Erythromycin 500 mg orally four times a day for 14–21 days is also effective. Buboes may require aspiration to prevent inguinal and femoral ulcerations from occurring. Sexual partners should also be treated.

Genital herpes

Because genital herpes is not a reportable disease in Australia and New Zealand, its true incidence is difficult to determine. However, in New Zealand during 2005 the incidence of patients with genital herpes presenting to SYHCs increased by 50%, and by 2009 it had increased again by a further 41.1%.3 A majority of those were male and under 25 years of age.3 According to the Australian Herpes Management Forum (AHMF), genital herpes is underdiagnosed, with up to 80% of cases not recognised by clinicians.21 In a recent Australian study, herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) was found in 12% of adults, with women and Indigenous Australians having the highest incidence. Herpes simples virus type 1 (HSV-1) was found to be prevalent in 76% of the population, with variance dependent on gender and ethnicity.22

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

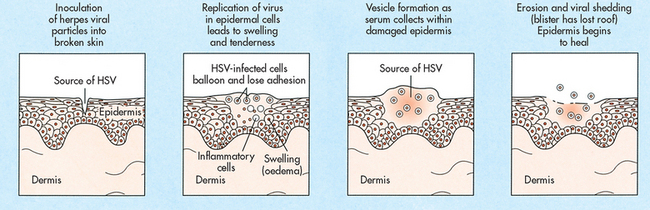

The herpes simplex virus (HSV) enters through the mucous membranes or breaks in the skin during contact with an infected person (see Fig 52-7). The virus reproduces inside the cell and spreads to the surrounding cells. It then enters the peripheral or autonomic nerve endings and ascends to the sensory or autonomic nerve ganglion, where it often becomes dormant. Viral reactivation (recurrence) may occur when the virus descends down to the initial site of infection, either the mucous membranes or skin. When a person is infected with HSV, the virus usually persists within the individual for life. The virus can remain in a nerve cell in a quiescent state and not cause a partner to become infected. Once the virus becomes active and is infective again, it ‘sheds’ and is excreted from the host. Shedding of the virus, even in the absence of an identifiable lesion, is a well-established phenomenon.

Two different strains of HSV cause infection. In general, HSV-1 causes infection above the waist, involving the gingivae, dermis, upper respiratory tract and CNS. HSV-2 most frequently infects the genital tract and the perineum (i.e. locations below the waist). However, either strain can cause disease on the mouth or genitals. Because HSV is readily inactivated at room temperature and by drying, airborne and fomitic (non-living objects) spread have not been documented as a significant means of transmission. Most people infected with HSV-1 or HSV-2 are asymptomatic or unaware of their infection.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

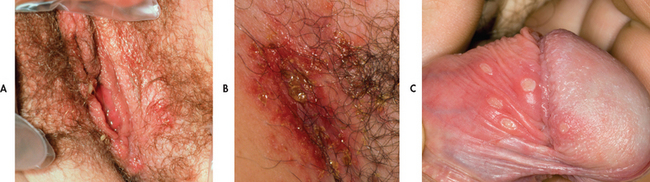

In the primary (initial) episode of genital herpes the patient may complain of burning or tingling at the site of inoculation. Vesicular lesions, which may occur on the penis, scrotum, vulva, perineum, perianal region, vagina or cervix, contain large quantities of infectious viral particles (see Fig 52-8). The lesions rupture and form shallow, moist ulcerations. Finally, crusting and epithelialisation of the erosions occur. Primary infections tend to be associated with local inflammation and pain, accompanied by systemic manifestations of fever, headache, malaise, myalgia and regional lymphadenopathy.

Figure 52-8 Unruptured vesicles of herpes simplex virus type 2. A, Vulvar area. B, Groin area. C, Penile herpes simplex ulcerative stage.

Urination may be painful from the urine touching active lesions. Urinary retention may occur as a result of HSV urethritis or cystitis. A purulent vaginal discharge may develop with HSV cervicitis. The duration of symptoms is longer and the frequency of complications is greater in women. Primary lesions are generally present for 17–20 days but new lesions sometimes continue to develop for 6 weeks. The lesions heal spontaneously unless secondary infection occurs.

Recurrent genital herpes occurs in about 50–80% of individuals during the year following the primary episode. Stress, fatigue, sunburn and menses are commonly noted trigger factors. Many patients can predict a recurrence by noticing the early prodromal symptoms of tingling, burning and itching at the site where the lesions will eventually appear. The symptoms of recurrent episodes are less severe and the lesions usually heal within 8–12 days. Over time the recurrent lesions will generally occur less frequently.

Women with recurrent symptomatic genital herpes can shed the virus up to 1% of the time even when no visible lesions are present. Suppressive therapy with antiviral agents can reduce but not eradicate asymptomatic shedding. Barrier forms of contraception, especially condoms, used during asymptomatic periods may decrease transmission of the virus. When lesions are present, the patient should avoid sexual activity altogether because even barrier protection is not sufficient to eliminate disease transmission.

COMPLICATIONS

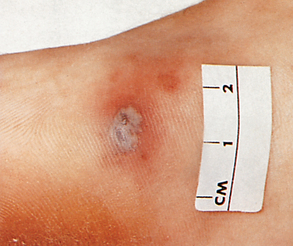

Although most infections are of a relatively benign nature, complications of genital herpes may involve the CNS, causing aseptic meningitis and lower motor neuron damage. Neuron damage may result in atonic bladder, impotence and constipation. Another complication is autoinoculation of the virus to extragenital sites, such as the lips, breasts and, most commonly, the fingers (herpetic whitlow) (see Fig 52-9).

Herpes simplex virus infection in pregnancy

Studies indicate no difference in the duration or severity of symptoms between pregnant and non-pregnant women. Women with a primary episode of HSV near the time of delivery have the highest risk of transmitting genital herpes to the neonate. The risk of transmission is lowest for women who acquire HSV early in the pregnancy or have a history of recurrent HSV. Although women with recurrent HSV infections are not at higher risk of transmitting the virus to their infants, an active genital lesion at the time of delivery is usually an indication for caesarean section delivery because most neonates are infected during birth.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A diagnosis of genital herpes is usually based on the patient’s symptoms and history. Absence of clinical symptoms is common in those with HSV infections and hence diagnosis is recommended based on results from laboratory testing.21 However, it is vital to obtain an accurate history too, in order to aid diagnosis. The diagnosis can be confirmed through isolation of the virus from active lesions by means of tissue culture. Tzanck- or Pap-stained smears from lesions may show the cellular characteristics of viral infection, including multinucleated giant cells and intranuclear inclusions. HSV infection can be confirmed by isolation of the virus in culture; however, these have been found to be insensitive and non-specific methods of diagnosis related to genital lesions. Other techniques to detect HSV include direct immunofluorescence and EIA. In addition, DNA amplification can be performed to detect HSV. These tests permit more rapid identification of HSV than a culture. Highly accurate serological methods for detecting the HSV type are available.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Drug therapy

Three antiviral agents are available for the treatment of HSV: aciclovir, valaciclovir and famciclovir. These drugs inhibit herpetic viral replication and are prescribed for primary and recurrent infections (see Box 52-5). Aciclovir, valaciclovir and famciclovir are also used to suppress frequent recurrences (more than six episodes per year). Although not a cure, these drugs reduce the duration of viral shedding and the healing time of genital lesions and reduce outbreaks by 75%.1,22 Continued use of oral aciclovir as suppressive therapy for up to 5 years is safe and effective but some experts recommend discontinuing aciclovir after 1 year for reassessment. Adverse reactions are mild and include headaches, occasional nausea and vomiting, and diarrhoea. The safety of these drugs for the treatment of pregnant women has not been established. Aciclovir ointment appears to have no clinical benefit in the treatment of recurrent lesions, either in the speed of healing or in the resolution of pain, and is not commonly recommended. IV aciclovir is reserved for severe or life-threatening infections in which hospitalisation is required for the treatment of disseminated infections, CNS infections (meningitis) or pneumonitis. Nephrotoxicity has been observed with high-dose IV use.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Collaborative therapy

Recurrent episodic infection

Aciclovir 400 mg three times a day or aciclovir 800 mg twice a day or famciclovir 125 mg twice a day or valaciclovir 500 mg twice a day or valaciclovir 1 g once a day; these drugs are given orally for 5 days or valaciclovir twice a day for 3 days or famciclovir 1000 mg twice a day for 1 day

Attempt to identify trigger mechanisms

Abstinence from sexual contact while lesions are present; however, virus may be shed without lesions

Source: Modified from Centers for Disease Control. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. Available at www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/STD-Treatment-2010-RR5912.pdf.

Symptomatic care

Symptomatic treatment, such as good genital hygiene and the wearing of loose-fitting cotton undergarments, should be encouraged. The lesions should be kept clean and dry. To ensure complete drying of the perineal area, women may use a hair dryer set on a cool setting. Frequent saline baths may soothe the area and reduce inflammation and may provide some relief from the burning and itching. Application of Betadine paint and/or exposing the ulcers to the warmth of a reading light may also be helpful. To reduce pain on urination, pouring a warm jug of water onto the perineal area while voiding to dilute the urine may give some relief. Pain may require a systemic analgesic, such as codeine and aspirin. Sexual transmission of HSV has been documented during asymptomatic periods. The use of barrier methods, especially condoms, should be encouraged.

Genital warts

Genital warts (condylomata acuminata) are caused by the human papilloma virus (HPV). Visible genital warts are usually caused by HPV types 6 and 11. These types can also cause warts on the anus, urethra and vagina. Other HPV types in the genital region (e.g. types 16, 18, 31, 33 and 35) are associated with vulval, penile, anal and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. HPV is highly contagious and may occur in up to 80% of sexually active people. Minor trauma during intercourse can cause abrasions that allow HPV to enter the body. The epithelial cells infected with HPV undergo transformation and proliferation to form a warty growth. The incubation period of the virus is generally 1–6 months but may be longer. Prevention is hampered by a high proportion of asymptomatic infections and lack of curative treatment. Genital warts are not reportable in either Australia or New Zealand.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Genital warts are discrete single or multiple papillary growths that are white to grey and flesh coloured. They may grow and coalesce to form large, cauliflower-like masses. Most patients have from one to 10 genital warts. In men, the warts may occur on the penis and scrotum, around the anus or in the urethra. In women, the warts may be located on the vulva, vagina or cervix and in the perianal area (see Fig 52-10). There are usually no other signs or symptoms. Itching may occur with anogenital warts. Bleeding on defecation may occur with anal warts.

COMPLICATIONS

During pregnancy, genital warts tend to grow rapidly. An infected mother may transmit the condition to her newborn. Caesarean delivery is not routinely indicated.

Subclinical human papilloma virus infections

HPV infection has been linked with cervical and vulvar cancer in women and with anorectal and squamous cell carcinoma of the penis in men. To date more than 100 types of HPV have been identified, at least 33 of which invade the genital tract. Some of these types appear to be harmless and self-limiting (e.g. types 6 and 11 commonly found in genital warts), whereas others are thought to have oncogenic (cancer-causing) potential (e.g. types 16 and 18). Up to two-thirds of the early lesions caused by HPV are undetectable by visual examination. Flat subclinical lesions are commonly found on the cervix and anal mucosa of women and on the penis and anal mucosa of men. These lesions are strongly associated with the development of dysplasia and neoplasia at these sites.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A diagnosis of genital warts can be made on the basis of the gross appearance of the lesions. However, the warts may be confused with condylomata lata of secondary syphilis, carcinoma or benign neoplasms. Serological and cytological testing should be done to rule out these conditions. If dysplasia is confirmed by Pap smear, a colposcopic examination and biopsies should be performed. Currently, HPV cannot be confirmed by culture.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

The primary goal when treating visible genital warts is the removal of symptomatic warts. The removal may or may not decrease infectivity. Genital warts are difficult to treat and often require multiple visits with a variety of treatment modalities. None of the treatments are superior to other treatments. Many patients will have a course of therapy rather than one treatment. The therapy should be modified if a patient has not improved after three treatments or if after six treatments the warts have not completely disappeared.

One common treatment is the use of 80–90% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) applied directly to the wart surface. Vaseline is applied to the surrounding normal skin to minimise irritation before a small amount of TCA is applied to the wart with a cottonwool swab. A sharp stinging pain is often felt with initial acid contact but this quickly subsides. TCA is not washed off after treatment. It can also be used in pregnant women. Podophyllin resin (10–25%), a cytotoxic agent, is recommended therapy for small external genital warts. When podophyllin is used, it is applied carefully to each wart, with normal tissue being avoided, and is then thoroughly washed off in 1–4 hours. This substance encourages the sloughing off of skin containing viral particles. Podophyllin has local (e.g. pain, burning) and systemic (e.g. nausea, dizziness, leucopenia, respiratory distress) toxic symptoms. It is contraindicated in pregnant women. In general, warts located on moist surfaces respond better to topical treatment (e.g. TCA, podophyllin) than do warts on drier surfaces.

Patient-managed treatment such as podophyllotoxin is an option. The patient applies the solution twice daily for 2–3 days followed by 4 days of no treatment. It can be repeated for up to five cycles. Imiquimod cream is an immune response modifier that is applied once daily at bedtime, three times a week for up to 16 weeks. Neither of these treatments is recommended for use during pregnancy or lactation.

If the warts do not regress with any of these therapies, treatments such as cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen, electrocautery, laser therapy and surgical excision may be indicated.23 Because treatment does not destroy the virus, merely the infected tissue, recurrences and reinfection are possible and careful long-term follow-up is advised.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

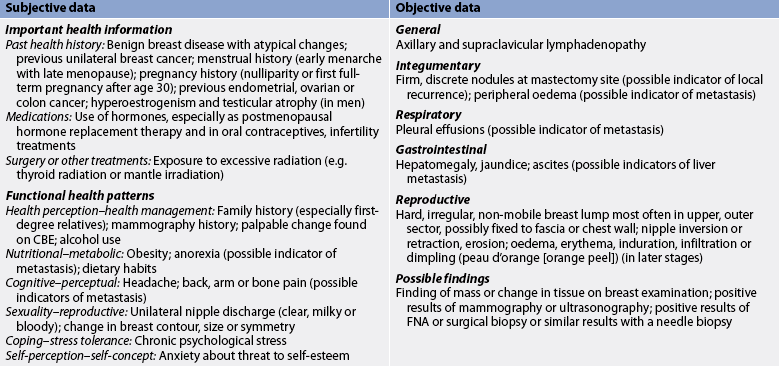

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from the patient with an STI are presented in Table 52-4.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with an STI include, but are not limited to, the following:

• risk of infection related to lack of knowledge about mode of transmission, inadequate personal and genital hygiene, and failure to practise precautionary measures

• anxiety related to impact of condition on relationships, disease outcome and lack of knowledge of disease

• ineffective health maintenance related to lack of knowledge about disease process, appropriate follow-up measures and possibility of reinfection.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with an STI will: (1) demonstrate understanding of the mode of transmission of STIs and the risk posed by STIs; (2) complete treatment and return for appropriate follow-up; (3) notify or assist in notification of sexual contacts about their need for testing and treatment; (4) abstain from intercourse until infection is resolved; and (5) demonstrate knowledge of safer sex practices.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

Many approaches to reducing the spread of STIs have been advocated and have met with varying degrees of success. Nurses should be prepared to discuss practices with all patients, not only those who are perceived to be at risk. These ‘safe sex’ practices include abstinence, monogamy with an uninfected partner, avoidance of certain high-risk sexual practices and use of condoms and other barriers to limit contact with potentially infectious body fluids or lesions. Sexual abstinence is a way of avoiding all STIs but few adults consider this a feasible alternative to sexual expression. Limiting sexual intimacies outside a well-established monogamous relationship can reduce the risk of contracting an STI. A patient and family teaching guide related to the patient with an STI is presented in Box 52-6.

BOX 52-6 Sexually transmitted infections

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

1. Instruct the patient in hygienic measures, such as washing and urinating after intercourse, to destroy many causative organisms.

2. Explain the importance of taking all antibiotics as prescribed. Symptoms will improve after 1–2 days of therapy but organisms may still be present.

3. Teach the patient about the need for treatment of sexual partners with antibiotics to prevent transmission of disease.

4. Instruct the patient to abstain from sexual intercourse during treatment and to use condoms when sexual activity is resumed to prevent spread of infection and reinfection.

5. Explain the importance of follow-up examination and re-culture at least once after treatment if appropriate to confirm complete cure and prevent relapse.

6. Allow the patient and partner to verbalise concerns to clarify areas that need explanation.

7. Instruct the patient about symptoms of complications and the need to report problems to ensure proper follow-up and early treatment of reinfection.

8. Explain precautions to take, such as being monogamous; asking potential partners about sexual history; avoiding sex with partners who use intravenous drugs or who have visible oral, inguinal, genital, perineal or anal lesions; using condoms; voiding and washing genitalia after coitus to reduce the occurrence of reinfection.

9. Inform the patient regarding the state of infectivity to prevent a false sense of security, which might result in careless sexual practices and poor personal hygiene.

All sexually active women should be screened for cervical cancer. Women with a history of STIs are at greater risk of cervical cancer than women without this history. Pap smears are discussed in Chapter 53.

Measures to prevent infection

Measures to prevent infection

An inspection of the sexual partner’s genitals before coitus is recommended. The presence of discharge, sores, blisters or rash should be viewed with concern.24 A patient who is aware of specific signs and symptoms of infection can intelligently make the decision to continue the sexual interaction with modifications or elect not to have sexual relations. The patient should remember that, when engaging in sex, there is exposure to the infections of everyone with whom the partner has ever had sex. Men should be told that some protection is provided if they void immediately following intercourse and wash their genitalia and the adjacent areas with soap and water. Women may also benefit from postcoital voiding and washing. However, it should not be assumed that this provides adequate protection against STIs after exposure to infection. Although spermicidal jellies and creams have a mild detergent effect that may reduce the risk of contracting STIs, this has not been proven. These same barriers can serve as supplementary lubrication, thereby decreasing irritation and friction and the chance for development of a minor laceration that could serve as an entry point for the organism.

Proper use of a latex condom provides a highly effective mechanical barrier to infection. The condom should be undamaged and correctly in place throughout all phases of sexual activity. It is unknown if a condom lubricated with a spermicide such as nonoxynol-9 further reduces the risk of STIs. Vaginal spermicides, when used alone without a condom, reduce the risk of Chlamydia infection and gonorrhoea.11 However, the patient should be strongly cautioned that although condoms and spermicides are helpful in preventing pregnancy, they do not protect against most STIs. Deterrents to condom usage include alcohol and drug use, embarrassment in purchasing condoms, reduced sensations of pleasure, becoming sexually active at a younger age and multiple partners.22 Studies indicate that IV drug users do not consistently use condoms. Use of barrier contraceptives requires planning and motivation, both of which are impaired with alcohol or illegal drug ingestion. The patient should be given specific verbal and written instructions on the proper use of condoms. The objections to condom usage, such as interference with spontaneity and the presence of a barrier, should be discussed by the partners. Information about the mechanics of sexual arousal and incorporating a condom into lovemaking can help in overcoming patient or partner resistance to its use. Female condoms are lubricated polyurethane sheaths with a ring at each end designed for vaginal wear. Laboratory studies indicate that they are an effective barrier to microorganisms, including viruses, but clinical trials are currently lacking for STIs.

Sexual contact with persons known or suspected to have HIV infection should be avoided (Ch 14). Among couples with one infected partner, consistent and scrupulous condom use can reduce transmission to the uninfected partner. Men who have sex with men can reduce their risks of contracting STIs by minimising the number of sexual contacts. Unprotected anal intercourse and other high-risk behaviours should be eliminated and condoms should be used if sexual contact continues.

The nurse can initiate an interview to establish the patient’s risk of contracting an STI. Questions to ask include the number of partners, type of birth control used, use of condoms, use of IV drugs and sexual preference. Patient education can be planned based on the response to these questions. Interpersonal skills that are necessary for this interview include respect, compassion and a non-judgemental attitude. Counselling should be tailored to the needs of the individual patient.

Screening programs

Screening programs

Screening programs that are used to detect infected patients can also help prevent certain STIs. Screening programs have been developed and implemented for the detection of gonorrhoea and Chlamydia. These programs are targeted at women because women are more likely to have asymptomatic gonorrhoea and thereby serve as sources of infection. Routine gonorrhoeal and Chlamydia testing during pelvic examinations and prenatal visits are being performed as a major part of these programs. Their effectiveness is well documented.8,11,23 Mass application of screening programs for genital Chlamydia infections, genital herpes and HPV infections (warts) may also be possible with the advent of rapid, cost-effective tests.

Case finding

Case finding

Interviewing and case finding are other processes used to control STIs. These activities are directed towards locating and examining all contacts of each known patient with an STI as soon after sexual exposure as possible so that effective treatment can be initiated. Trained interviewers may often find cases even if they are supplied with only limited information. Sexual health professionals, who are often nurses, are aware of the social implications of these diseases and the need for discretion. Sexual contacts are often not informed about the origin of the information naming them as a contact so that greater cooperation and privacy is ensured.

Educational and research programs

Educational and research programs

Nurses can actively encourage their communities to provide better education about STIs for their citizens. Teenagers, who are known to have a high incidence of infection, should be a prime target for such educational programs. Websites, school nurses, nurse practitioners, women’s health nurses and specialist sexual health services throughout regions, territories and states provide educational support. Knowledge and understanding can decrease the STI epidemic. Currently, efforts are being made to develop immunising agents for syphilis, gonorrhoea, genital herpes, HPV and HIV. The development of effective vaccines is viewed by many clinicians as the only means of eradicating STIs.

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

Psychological support

Psychological support

The diagnosis of an STI may be met with a variety of emotions, such as shame, guilt, anger and a desire for vengeance. The nurse should provide counselling and try to help the patient to verbalise their feelings. Couples in marital or committed relationships are confronted with an added problem when an STI is diagnosed. The implication of sexual activity with a person outside the relationship by one of the partners must be faced. Other concerns about their relationship may be present and the acute problem may serve as an incentive for further problem solving. Support and counselling for the couple are needed. A referral for professional counselling to explore the ramifications of an STI in their relationship may be indicated.

A patient who has genital herpes is faced with the fact that repeated infections can occur and that no cure is available. This can be frustrating and disruptive to the patient’s physical, emotional, social and sexual lives. Helping the patient to identify and avoid any factors that may precipitate the condition is indicated. Informing the patient that the incidence and severity of recurrences will decrease over time may provide some support.

HPV infections involve a prolonged course of treatment. The patient can become frustrated and distressed because of frequent healthcare visits, associated costs, the potential for unpleasant side effects as a result of treatment, and effects of the infection on future health and sexual relationships. The nurse needs to show tremendous support and a willingness to listen to the patient’s concerns.

Compliance and follow-up

Compliance and follow-up

Nurses working in public health facilities, clinics or other outpatient settings may care for patients with an STI more often than nurses in a hospital. These nurses are in a position to explain and interpret treatment measures such as the purpose and possible side effects of prescribed drugs and the need for follow-up care.

Frequently, single-dose treatment for gonorrhoea, Chlamydia infection and syphilis helps prevent the problems associated with non-compliance with drug therapy. The patient requiring multiple-dose therapy should be given special instructions in completing the prescribed regimen and should be informed about problems resulting from non-compliance. All patients should return to the treatment centre for a repeat culture from the infected sites or for serological testing at designated times to determine the effectiveness of the treatment. Informing the patient that cures are not always obtained on the first treatment can reinforce the need for a follow-up visit. The patient should also be advised to inform sexual partners of the need for testing and treatment, regardless of whether they are free of symptoms or experiencing symptoms.

Hygiene measures

Hygiene measures

The patient with an STI should have certain hygiene measures emphasised. An important measure is frequent hand-washing and bathing. Bathing and cleaning of the involved areas can provide local comfort and prevent secondary infection. Douching may spread the infection or undermine local immune responses and is therefore contraindicated. Synthetic materials used in most undergarments frequently increase or exacerbate local irritations by trapping moisture. Cotton underwear provides better absorption and is cooler and more comfortable for the patient with an STI.

Sexual activity

Sexual activity

Sexual abstinence is indicated during the communicable phase of the disease. If sexual activity occurs before treatment of the patient has been completed, the use of condoms may prevent the spread of infection and reinfection. Condom usage after treatment should be encouraged to prevent future exposure to infection. The patient can also choose to relate to a partner in an intimate way that avoids both coitus and oral–genital contact. It is important to note that even single-dose treatments can take up to 1 week to be effective and thus the patient is infective during this period.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

Because many STIs are cured with a single dose or short course of antibiotic therapy, many patients are casual about the outcome of these diseases. The consequences of this attitude can include delays in treatment, non-compliance with instructions and the subsequent development of complications. Complications are serious and costly, and they can result in disfigurement and destruction of important tissues and organs.

Surgery and prolonged therapy are indicated for many patients with disease-related complications. Major surgical procedures, such as resection of an aneurysm or aortic valve replacement, may be necessary to treat cardiovascular problems caused by syphilis. Pelvic surgery and procedures to correct fertility problems secondary to an STI may include lysis of adhesions, dilation of strictures, reconstructive tuboplasty and in-vitro fertilisation.

Evaluation

Evaluation

Expected outcomes for the patient with an STI are that the patient: (1) describes modes of transmission; (2) uses appropriate hygienic measures; (3) experiences no reinfection; and (4) demonstrates compliance with the follow-up protocol.

CASE STUDY

Patient profile

Jade Kohl is a 17-year-old female who visits the outpatient family planning clinic seeking birth control pills.

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

1. What were this patient’s risk factors for acquiring Chlamydia infection?

2. What complications could have occurred if her infection had not been detected?

3. What impact is this patient’s diagnosis likely to have on her self-image? On her relationship with her boyfriend?

4. What instructions should she receive to ensure successful treatment? To prevent reinfection? To prevent further transmission of the infection?

5. What does this patient need to know about other STIs? What other testing would you recommend?

6. Based on the assessment data presented, write one or more nursing diagnoses. Are there any collaborative problems?

1. What are the best strategies for encouraging safer sex practices and condom use among high-risk populations?

2. What is the level of teenagers’ knowledge of the risk, transmission and impact of STIs? How can teaching about STIs best be adapted to their development level?

3. Does education about safer sex practices increase preventative behaviours?

1. The individual with the lowest risk of sexually transmitted pelvic inflammatory disease is a woman who:

2. While obtaining subjective assessment data from a woman reported as a sexual contact of a man with Chlamydia infection, the nurse understands that symptoms of Chlamydia infections in women:

3. A primary herpes simplex virus infection differs from recurrent episodes in that:

4. The nurse explains to a patient with gonorrhoea that treatment will include both ceftriaxone and a doxycycline agent because:

5. A patient with a sexually transmitted infection (STI) who is most likely to have a nursing diagnosis of disturbed body image that hinders future sexual relationships is the patient with:

6. Teaching by the nurse to prevent infection and transmission of STIs includes explanations of:

7. An appropriate nursing intervention to provide emotional support to a patient with an STI is to:

1 World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the management of sexually transmitted infections. Geneva: WHO; 2003. Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241546263.pdf accessed 23 August 2010.

2 Australian Institute of Health & Welfare (AIHW). Australia’s health, 2010. Canberra: AIHW, 2010.

3 Best Practice Advocacy Centre (BPACNZ). The STI handbook: sexually transmitted infections in New Zealand. Available at www.bpac.org.nz/resources/handbook/sti/sti.asp, 2009. accessed 28 December 2010.

4 Singer MC, Erickson PI, Badiane L, et al. Syndemics, sex and the city: understanding sexually transmitted diseases in social and cultural context. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(8):2010–2021.

5 Sheary B, Dayan L. Contraception and sexually transmitted infections. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34(10):869–872.

6 Flores SA, Mansergh G, Marks G, Guzman R, Colfax G. Gay identity-related factors and sexual risk among men who have sex with men in San Francisco. AIDS Ed Prevent. 2009;21(2):91–103.

7 NNDSS Annual Report Writing Group. Australia’s notifiable disease status, 2008: annual report of the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. CDI vol. 34, no. 3. Canberra: Department of Health & Ageing; 2010. Available at www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/cda-cdi3403-pdf-cnt.htm/$FILE/cdi3403a.pdf accessed 28 December 2010.

8 STI Surveillance Team. Sexually transmitted infections in New Zealand: annual surveillance report, 2009. Auckland: Institute of Environmental Science and Research, 2010.

9 WHO Western Pacific Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme. Surveillance of antibiotic resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the WHO Western Pacific region, 2000. Commun Dis Intell. 2001;25(4):274–276.

10 Australian Gonococcal Surveillance Programme. Annual report of the Australian Gonococcal Surveillance Programme, 2005. Commun Dis Intell. 2006;30(2):205–210.

11 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Available at www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/STD-Treatment-2010-RR5912.pdf, 2010. accessed 28 December 2010.

12 Australian Indigenous Health Infonet. Overview of Indigenous health, 2010. Communicable Diseases. Available at www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/health-facts/overviews/selected-health-conditions/communicable-disease. accessed 28 December 2010.

13 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis elimination effort. Available at www.cdc.gov/stopsyphilis/default.htm. accessed 23 August 2010.

14 BetterHealthVictoria. Syphilis. Available at www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/bhcv2/bhcarticles.nsf/pages/Syphilis. accessed 28 December 2010.

15 Andrews WW, Goldenberg RL, Mercer B, et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: association of second-trimester genitourinary Chlamydia infection with subsequent spontaneous birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(3):662–668. Seminal paper

16 Andrews WW, Klebanoff MA, Thom EA, et al. Midpregnancy genitourinary tract infection with Chlamydia trachomatis: association with subsequent preterm delivery in women with bacterial vaginosis and Trichomonis vaginalis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(2):493–500.

17 Toro M. Combating infection: closing in on chlamydia. Nursing. 2008;38:61.

18 Braverman PK, Schwarz DF, Deforest A, et al. Use of ligase chain reaction for laboratory identification of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in adolescent women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2002;15(1):37–41.

19 van Hal SJ, Hillman R, Stark DJ, Harkness JL, Marriott D. Lessons from practice. Lymphogranuloma venereum: an emerging anorectal disease in Australia. Med J Aust. 2007;187(5):309–310.

20 Eisen DP. Locally acquired lymphogranuloma venereum in a bisexual man. Med J Aust. 2005;183(4):218–219.

21 Australian Herpes Management Forum (AHMF). Guidelines for clinicians: managing genital herpes. Sydney: AHMF, 2009.

22 Abel G, Brunton C. Young people’s use of condoms and their perceived vulnerability to sexually transmitted infections. Aust New Zeal J Publ Health. 2005;29(3):254–260.

23 Cunningham AL, Taylor R, Taylor J, et al. Prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in Australia: a nationwide population based survey. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(2):164–168.