Other Challenges in Pain Assessment

SOME patients with pain are simply incapable of providing self-reports of pain. They may be cognitively impaired or unconscious. Such circumstances necessitate using other, less reliable indicators of pain, always being mindful that in the absence of self-reports all else is an educated guess.

This group includes patients who have a wide range of communication difficulties, from those who are conscious but unable to speak to those who are unconscious and, of course, unable to speak. Examples are adults who have cognitive impairment, as discussed in the previous chapter; who have severe emotional disturbances; who are intubated; who are developmentally delayed; who speak a language other than English; or whose educational or cultural backgrounds are significantly different from those of the health care team (APS, 2003). Such patients pose assessment challenges and are at risk for undertreatment.

Patients who are critically ill, intellectually disabled, mentally ill, or unconscious are discussed in this chapter. Cultural considerations are also included.

Patients Who Are Critically Ill

Some critically ill patients are mistakenly believed to be unconscious or pain-free, but pain in critically ill patients has been well documented for some time. For example, patients with endotracheal tubes and those who have received neuromuscular blocking agents such as pancuronium (which does not alter sensitivity to pain) may be fairly alert, and some are fully capable of feeling pain and are able to self-report pain if given the appropriate opportunity. In a sample of 24 patients in an intensive care unit (ICU), interviews after transfer from the ICU revealed that all but 1 patient recalled their ICU stays, and 63% recalled moderate to severe pain (Puntillo, 1990). The patients described pain caused by surgical incisions, movement, coughing, endotracheal suctioning, and chest tube removal. Those who could not talk (80% had endotracheal tubes) described numerous behaviors they used in attempts to tell staff they were in pain, such as signaling with their eyes and moving their legs up and down. These patients are actually capable of giving self-reports of pain. Some can use writing materials and can be taught to use a pain rating scale. Some can use the call button, which should be placed within easy reach. Others can be asked questions and be taught to signal with their eyes that pain is present. For example, the clinician can establish with the patient that when asked about pain, squeezing the eyes once means yes and twice means no.

Clinicians are prone to overlook pain at rest as well as pain resulting from common procedures such as turning and suctioning. In a study of 30 critically ill, traumatically injured patients, pain was measured at rest in a supine position and after being turned onto their sides (Stanik-Hutt, Soeken, Belcher, 2001). On a visual analog scale (VAS) (0 to 100 mm), mean at-rest scores were 34.5, which indicates mild pain bordering on moderate pain. Immediately after the turns, the mean scores were 48.1 on the VAS, indicating moderate pain. Terms commonly used to describe pain at rest included throbbing, sharp, sore, hurting, and annoying. After turning, the pain was often described with the same words used for pain at rest (except for hurting) plus pressing, pulling, tender, tiring, and miserable. Of these patients, 13 were not included in the study because they refused to be turned, giving as the reason severe pain at rest or anticipated pain with turning. Their pain at rest was 47.1 on the VAS. Based on their review of the literature, the researchers concluded that pain intensity at rest in this study was in the same range as that in other studies of critically ill patients.

Endotracheal suctioning also causes considerable pain. In a study of 45 adults having cardiovascular (CV) surgery, patients rated their pain during endotracheal suctioning on a 0-to-10 scale (Puntillo, 1994). The mean pain intensity score was 4.5, and more than one third of the patients reported a pain intensity of 7 or greater, indicating severe pain. Patients described the pain as tiring-exhausting, stabbing, tender, sharp, and heavy.

The results of the Thunder Project II, a multisite study, provide extensive information about procedural pain in acute and critically ill patients (Puntillo, White, Morris, et al., 2001). In a total of 153 clinical sites, information was collected from 6201 patients, 5957 of whom were 18 years or older. Patients were alert and able to answer questions. Data were obtained about pain related to six procedures: turning, wound drain removal, tracheal suctioning, femoral catheter removal, placement of a central venous catheter, and nonburn-wound dressing change. Adults rated their procedural pain intensity as 2.65 to 4.93 on a 0-to-10 numerical rating scale (NRS). The most painful and distressing procedure for adults was turning; the mean pain intensity was 4.93 and the mean distress score was 3.47 on a scale of 0 to 10. After turning, the most painful procedures in adults, in descending order, with mean pain intensity in parentheses, were wound drain removal (4.67); wound care (4.42); tracheal suctioning (3.94); central line placement (2.72); and femoral sheath removal (2.65). Pain at rest was usually described as aching, and procedural pain was often described as sharp.

Thus, critically ill patients experience mild to moderate pain throughout the day. At rest, the pain is commonly mild, but turning, which usually occurs at least every 2 hours, is associated with moderate pain and, compared to other painful procedures, is the most distressing.

In a follow-up to the study just described, Puntillo, Wild, Morris, and others (2002) examined analgesic and local anesthetic administration in the 5957 adults they assessed prior to and during the six procedures. Undertreatment of procedural pain was apparent. More than 63% of the patients received no analgesics before or during the procedures, and less than 20% received opioids. The patients most likely to receive opioids were those undergoing femoral sheath removal (28.6%), and those least likely to were undergoing tracheal suctioning (3.7%). A total of 18.4% of patients received local anesthetics, and 89.5% of them were undergoing placement of a central venous catheter. Part of this undertreatment may be the result of failure to assess pain or anticipate pain. All of these patients were alert, and pain could have been assessed at least during the procedure or prior to the procedure for those who had already experienced the procedure, such as turning or tracheal suctioning.

Further analysis of data available from the previously mentioned study of 5957 critically ill adults revealed information about behavioral responses associated with the six procedures being studied (Puntillo, Morris, Thompson, et al., 2004). All the patients in this study were alert and able to self-report, but many critical care patients are unable to provide self-reports of pain because of intubation, motor impairments, cultural or language barriers, or altered levels of consciousness. Behavioral responses to pain may then become one of the most valuable contributions to pain assessment. A 30-item behavioral tool was used to observe patients’ behaviors before and during the procedures. Significantly more behaviors were exhibited by patients with procedural pain than by those without that pain. Behaviors specific to procedural pain were grimacing, rigidity, wincing, shutting of eyes, verbalizations, moaning, and clenching of fists.

The FLACC (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability) Behavioral Scale has recently been studied in 29 critically ill adults and children who could not self-report pain (Voepel-Lewis, Zanotti, Dammeyer, 2010). This is the first study to provide support of the FLACC in this population, but further study is warranted.

Several behavioral scales for use with adult patients in critical care and unable to self-report are being developed, and the psychometric properties of six of these scales have been compared (Li, Puntillo, Miaskowski, 2008). They are listed here with references that include the actual tool:

• The Behavioral Pain Rating Scale (BPRS) (Mateo, Krenzischek, 1992)

• The Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS) (Payen, Bru, Bosson, et al., 2001)

• Pain Behavior Assessment Tool (PBAT) (Puntillo, Morris, Thompson, et al., 2004)

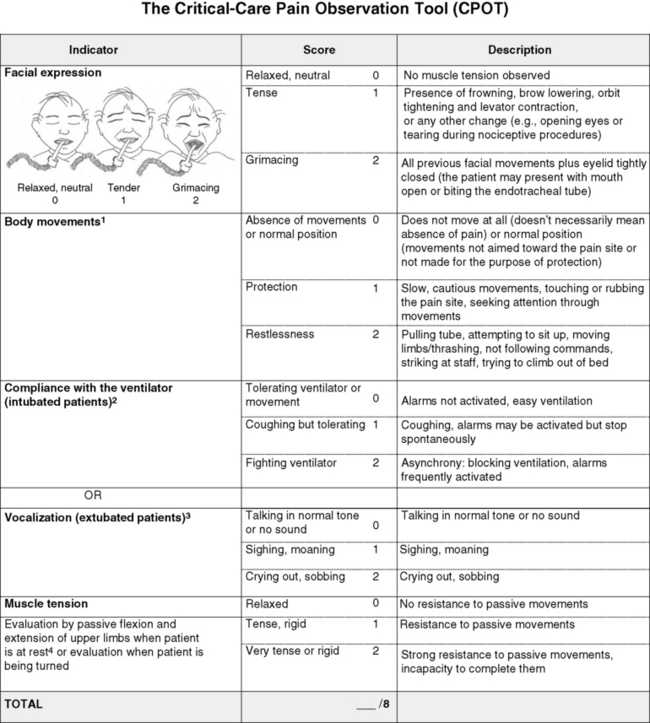

• Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) (Gelinas, Fillion, Puntillo, et al., 2006)

• Pain Assessment and Intervention Notation (PAIN Algorithm) (Puntillo, Miaskowski, Kehrie, et al., 1997)

• Nonverbal Pain Scale (NVPS) (Odhner, Wegman, Freeland, et al., 2003).

Review of these assessment tools revealed that none had undergone vigorous validation or had been accepted as standardized measures, but two showed good evidence of validity and reliability—the BPS and the CPOT (Li, Puntillo, Miaskowski, 2008). Both are described here, and both are easy to use. However, we feel that the CPOT is a slightly better choice for clinical practice because it includes four behavioral domains instead of the three that are in the BPS, and because the CPOT divides the domain of patients on ventilators into two groups, patients who are intubated and patients who are not; whereas the BPS addresses only ventilated patients. Therefore, the actual tool for the CPOT is included (Form 4-1).

Form 4-1 As appears in Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. (2011). Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 145, St. Louis, Mosby. Instructions Form modified from Gélinas, C., Fillion, L., Puntillo, K. A., et al. (2006). Validation of the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) in adult patients. Am J Crit Care, 15(4), 420-427. 1Puntillo, K. A., Miaskowski, C., Kehrle, K., et al. (1997). Relationship between behavioral and physiological indicators of pain, critical care self-reports of pain, and opioid administration. Crit Care Med, 25(7), 1159-1166; 2Devlin, J. W., Boleski, G., Mlynarek, M., et al. (1999). Motor activity assessment scale: A valid and reliable sedation scale for use with mechanically ventilated patients in an adult surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med, 27(7), 1271-1275; 3Harris, C. E., O’Donnell, C. MacMillan, R. R., et al. (1991). Use of propofol by infusion for sedation of patients undergoing haemofiltration: Assessment of the effect of haemofiltration on the level of sedation and on blood propofol concentration. J. Drug Dev, 4(Suppl 3), 37-39; 4Payen, J. F., Bru, O., Bosson, J. L., et al. (2001), Assessing pain in the critically ill sedated patients by using a behavioral pain scale. Crit Care Med, 29(12), 2258-2263; 5Mateo, O. M., Krenzischek, D. A. (1992). A pilot study to assess the relationship between behavioral manifestations and self-report of pain in postanesthesia care unit patients. J Post Anes Nurs, 7(1), 15-21; 6Ambuel, B., Hamlett, K. W., Marx, C. M., et al. (1992). Assessing distress in pediatric intensive care environments: The COMFORT scale. J Pediat Pscych, 17(1), 95-109. Gélinas C.

The CPOT evaluates four behavioral domains: facial expressions, movements, muscle tension, and ventilator compliance (Gelinas, Fillion, Puntillo, et al., 2006) . Each domain has three behaviors, which are scored from 0 to 2. The critical review of assessment tools used with seriously ill patients points out that a weakness of the CPOT is that generally low scores were reported in all patients during painful procedures (Li, Puntillo, Miaskowski, 2008). This should be kept in mind when using the tool, and clinicians should remember that pain behaviors are merely indicators of pain and that the number of behaviors do not equate with pain intensity (Pasero, McCaffery, 2005).

The sensitivity and specificity of the CPOT was studied in a sample of 105 adults in an ICU following cardiac surgery (Gelinas, Harel, Fillion, et al., 2009). Pain was evaluated during the painful procedure of turning. Sensitivity was high during turning, meaning that the tool could detect when pain was not present. The specificity of the CPOT was also high; that is, it correctly identified the patients who did have pain. This reduces the likelihood of administering an analgesic to a patient who does not have pain.

The BPS consists of three behavioral domains: facial expression, movements of upper limbs, and compliance with ventilation. Each domain contains four behaviors, each rated from 1 to 4 (Payen, Bru, Bosson, et al., 2001). In the critical review of assessment tools used with critically ill patients, the point is made that the observation of no body movement is equated with a pain-free state in the BPS (Li, Puntillo, Miaskowski, 2008). However, no body movement may simply reflect sedation, restraints, or other restrictions of movement. Another criticism concerns the numbering system, which starts with 1, meaning no pain behavior. It is suggested that starting with 0 more readily reflects no pain behaviors.

The American Society for Pain Management Nursing (ASPMN) published a position statement on pain assessment in the nonverbal patient (available at http://www.aspmn.org/Organization/documents/NonverbalJournalFINAL.pdf) that includes a section about intubated and unconscious patients (Herr, Coyne, Key, et al., 2006). Recommendations for assessment utilize the template for the hierarchy of pain measures, as presented previously (see Box 3-9, p. 123):

• The hierarchy begins with an attempt to obtain a self-report. If that fails, the following indicators should be assessed, and one can assume pain is present (APP) if any of the measures indicates pain. Again, the abbreviation APP may be used for documentation if approved by institutional policy and procedure.

• Potential causes of pain, such as procedures or existing painful conditions, are next on the hierarchy. These should include noting that pain at rest can cause aching and that the following procedures have been found to be painful: turning (the most painful of this group), wound drain removal, tracheal suctioning, femoral catheter removal, placement of a central venous catheter, and nonburn wound dressing change.

• Following assessment for causes of pain, clinicians look for patient behaviors that may indicate pain. This is the point at which a behavioral pain assessment tool is used, and we recommend using the CPOT for critically ill patients.

• Next, reports of pain or observations of behaviors that might indicate pain are elicited, when possible, from people who know the patient well, such as caregivers and family members. They may know of previously existing painful conditions such as arthritis that have been causing pain.

• Finally, when in doubt about the presence of pain or when wanting to confirm the suspicion of pain, an analgesic trial may be helpful. The analgesic trial is used as the basis for developing the pain treatment plan once pain has been confirmed. (See Boxes 3-9 and 3-11, pp. 123 and 126, for more ideas about using the analgesic trial.)

Physiologic indicators of pain such as changes in blood pressure are omitted from the hierarchy of pain assessment techniques. Their limited usefulness in assessing pain is discussed in Chapter 2, pp. 27-28. They are occasionally helpful but, especially in critically ill patients, these measures are often influenced by factors other than pain, such as medications, mechanical ventilation, change in level of consciousness, and patients’ illnesses or surgeries. In critically ill patients, behavioral indicators have been found to provide more valid information for pain assessment than physiologic indicators (Arbour, Gelinas, 2009; Gelinas, Arbour, 2009; Gelinas, Johnston, 2007).

For example, a study of 254 critically ill patients in intensive care units who were mechanically ventilated (144 conscious and 114 unconscious) examined potential behavioral and physiologic indicators of pain and their association with self-reports of pain (Gelinas, Arbour, 2009). These patients were observed at rest, during a nociceptive procedure (such as endotracheal suctioning), and 20 minutes postprocedure. Behaviors were measured with the CPOT, and physiologic indicators were obtained from the available monitoring. Patients able to self-report pain were asked if they had pain or not immediately after being scored with the CPOT. This prevented bias in the raters because the CPOT was used before requesting a self-report. Based on the patient’s self-report, only the CPOT score, not changes in vital signs, could predict the presence or absence of pain; consequently, only behavioral observation was recommended for pain assessment in unconscious patients. The researchers noted that changes in vital signs could be used as a cue to begin further assessment of pain.

Probably because the physiologic changes are so readily able to be observed in the ICU, critical care nurses are tempted to use them as indicators of pain, especially in patients who are unable to self-report. However, as mentioned above, many patients actually are able to self-report pain if the right approaches are used, such as eye blinking and the CPOT. Research strongly recommends use of behaviors to assess pain in unconscious patients and warns that vital signs should be used with caution (Gelinas, Arbour, 2009).

Patients Who Are Unconscious

Some critically ill patients appear to be unconscious due to injury such as brain trauma or disease, sedating medications, or neuromuscular blocking agents. But unconscious patients also exist outside the critical care setting. For example, patients in vegetative states may be found in long-term care facilities. Terminally ill patients may become unconscious as death approaches.

If unconsciousness is defined as no awareness of self or environment, how is it possible that an unconscious patient could feel pain and suffer from it? The problem is that unconsciousness is not easily determined, and there are varying levels of unconsciousness. A minimally conscious state is described as one in which there is some evidence of awareness of self and environment, and a persistent vegetative state is defined as wakefulness without awareness of self or environment (Boly, Faymonville, Schnakers, et al., 2008). Anecdotal evidence and some research strongly suggest that quite a few patients who appear to be unconscious and unresponsive to painful stimuli actually feel and recall pain. Thus, clinicians should assume that the unconscious patient may feel pain and should provide analgesia if anything known to be painful is present.

In a study of 100 critically ill patients whose records indicated that they were unconscious, interviews with the patients revealed that only about one quarter of them were actually unaware of themselves and their surroundings (Lawrence, 1995). The remaining three quarters had some awareness of themselves and their environments, and about 25% were able to hear and to feel pain.

During general anesthesia, some patients experience periods of awareness that they recall postoperatively. In a study of 26 patients who had experienced awareness during general anesthesia, hearing sounds and feeling paralyzed were reported by 89% and 85%, respectively (Moerman, Bonke, Oosting, 1993). Of those patients, 10% reported feeling pain. Aftereffects such as sleep disturbances, nightmares, and flashbacks occurred in 70%, and pain was recalled by one half of these patients. In another study of 45 patients who experienced awareness during general anesthesia, 8 patients reported feeling severe pain (Schwender, Kunze-Kronawitter, Dietrich, et al., 1998). A large study of 3921 patients undergoing general anesthesia identified an incidence of 1% (39 patients) who experienced awareness with recall (Errando, Sigl, Robles, et al., 2008). Pain was felt by 11 patients.

An anecdotal report illustrates the tragedy of assuming an unconscious patient does not feel pain. A terminally ill patient was receiving intravenous morphine for cancer-related pain; as her disease progressed, she gradually became unresponsive to voices and no longer grimaced during position changes, which previously had been painful for her. Because she appeared to be unconscious and unresponsive to painful stimuli, morphine was no longer administered. After 3 days the patient regained consciousness and immediately asked for morphine. The patient reported that during the apparent “coma,” she had heard voices and felt intense pain (Stephens, 1994).

Regarding pain in terminally ill patients who appear to be unconscious, a recommendation made almost 3 decades ago is worth repeating: “When patients are no longer able to verbally communicate whether they are in pain or not, the best approach is to assume that their cancer is still painful and to continue them on their regular medications…. a therapeutic narcotic level should be maintained…. continued narcotics simply ensure that the death will be as peaceful and painless as possible” (Levy, 1985, pp. 397-398).

Whether patients in persistent vegetative states feel pain remains controversial. This state is defined as complete unawareness of self and environment, including lack of the cortical capacity to feel pain. However, some have voiced reservations about assuming that patients in vegetative states do not feel pain and have suggested that, until it can be proved otherwise, clinicians should assume that such patients feel pain and should treat that pain (Bushnell, 1997; Klein, 1997).

This position is also advocated by researchers who studied brain activation during noxious stimulation consisting of electrical stimulation of the median nerve, comparing 5 patients in minimally conscious states, 15 normal controls, and 15 patients in persistent vegetative states (Boly, Faymonville, Schnakers, et al., 2008). No brain area was less activated in patients in minimally conscious states than in the controls. All areas of the cortical pain matrix showed greater activation in these patients than in patients in persistent vegetative states. The researchers concluded that this evidence confirmed the need for analgesic treatment for patients in minimally conscious states. They pointed out, however, that misdiagnosis of patients in persistent vegetative states and minimally conscious states is common and concluded that analgesic treatment is indicated in both groups. Analgesics for patients in persistent vegetative states are indicated also to prevent potentially damaging defensive hormonal reactions such as the production of adrenal stress hormones, despite the possible absence of feelings of pain.

For some unconscious patients the CPOT, discussed earlier (see Form 4-1, pp. 145-146), may be appropriate if they are capable of responding in the four behavioral domains: facial expressions, movements, muscle tension, and ventilator compliance (Gelinas, Fillion, Puntillo, et al., 2006). If these behaviors are absent, documenting procedures or pathologies that probably cause pain may be relied upon to assume pain is present (APP), as is suggested in Box 3-9 (p. 123). A behavioral tool is appropriate only with patients who are able to respond with the tool’s requisite behaviors.

Clinicians often wonder which dose of opioid to administer on an ongoing basis to a patient who cannot respond with any behaviors to indicate the effectiveness of a dose one way or another. In such cases, opioid therapy should be initiated and maintained at the recommended starting dose (e.g., 2.5 mg/hr morphine IV for adults in possibly severe pain). However, clinicians should not hesitate to increase doses if there are any behaviors whatsoever that might indicate pain (see Chapter 27 for more about analgesic administration in the ICU).

Patients Who Are Intellectually Disabled

The term developmental disabilities encompasses mental or physical disabilities that are evident in childhood and continue throughout life (Craig, 2006). Intellectual disability (ID), as defined for this chapter, is a type of developmental disability in which some form of intellectual disability or cognitive impairment is noted in childhood. The ID may or may not be accompanied by physical disability. Conversely, physical disabilities such as cerebral palsy are not always accompanied by mental disabilities. IDs are commonly defined by IQ scores. An IQ score of 50 to 70 indicates mild cognitive impairment, a score of 35 to 49 indicates moderate impairment, a score of 20 to 34 indicates severe impairment, and profound impairment is an IQ score below 20 (Bottos, Chambers, 2006; Grossman, 1983). Individuals with mild cognitive impairment make up 85% of those with IDs and usually acquire about a sixth grade level of academic skills (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994). Moderate cognitive impairment occurs in about 10% of cases of ID, and severe and profound impairment constitute 1% to 4% of cases of ID.

This chapter focuses on adults with IDs, that is, adults who have been cognitively impaired since birth or early childhood. This state is not to be confused with that of adults who have been cognitively intact for most of their lives but become cognitively impaired in their later years. Dementia is an example of a cognitive impairment that occurs late in life in individuals who were cognitively intact previously. The literature can be confusing because the publications that use the term cognitive impairment in their titles may be focusing on adults who have become impaired as they have grown older or on adults who have been cognitively impaired since childhood. Pain assessment strategies previously discussed in the section on cognitively impaired older patients probably are not useful in assessing pain in adults with mental retardation. Adults who have been cognitively impaired since childhood require assessment tools that have been specially designed for them because these individuals do not have the same understandings and experiences as adults who have been cognitively intact for many years and become cognitively impaired in later life.

Most of the research on pain and ID has been conducted in infants and children, but many of the issues raised in those studies, such as assessment, are regarded as being relevant to the care of adults with IDs (Symons, Shinde, Gilles, 2008). Consequently, some studies of children are reviewed here even though this book focuses on adults. Some pain assessment tools used with children with IDs have been adapted and studied in adults with IDs.

A long-standing misconception is that persons with IDs, or mental retardation, are insensitive or indifferent to pain (Symons, Shinde, Gilles, 2008). After reviewing several studies of children with IDs, Symons and others (2008) concluded that caregivers of children with IDs frequently underestimated pain intensity. Consequently, these individuals are undertreated. This conclusion appears to be based on observations of behavior, not measurements of sensitivity to pain. It is hypothesized that what may be confusing about behavioral observations of these patients is that behavioral indicators of pain may be delayed or unconventional, contributing to the belief that this population has a lowered sensitivity to pain or a greater tolerance. However, testing of patients with mild intellectual disabilities by measuring heat-pain thresholds showed that their pain threshold was significantly lower than that of normal controls (Defrin, Pick, Peretz, et al., 2004). Thus, these individuals not only are sensitive to pain but also may be more sensitive to some types of pain than persons without IDs.

Along the same lines, children with autism have also been thought to be insensitive to pain, but this is not supported by research. In a study comparing 21 children with autism with 22 without autism, all of them undergoing venipuncture, the children with autism manifested significant facial reactions quite similar to those in the unimpaired group but characterized by more facial activity (Nader, Oberlander, Chambers, et al., 2004). A perplexing finding was that the children who were the most reactive during the venipuncture had been identified by the parents as being less sensitive and less reactive to pain.

Understanding the misconceptions of caregivers of children with disabilities may be helpful in recognizing the possibility that the same misconceptions may occur in reference to adults with IDs. The degree of agreement between parent and child regarding pain intensity was examined in 68 children with spina bifida who were able to communicate (Clancy, McGrath, Oddson, 2005). Children rated their pain, and their parents completed a proxy report of the pain. Parents tended to underestimate the intensity of the pain their children felt. In another study, 65 caregivers of children with IDs completed questionnaires about their beliefs regarding pain in this population and revealed complex beliefs (Breau, MacLaren, McGrath, et al., 2003). Caregivers believed that children’s sensations of pain increased as the severity of the ID increased. They also believed that children with mild cognitive impairment might overreact to pain. Perhaps most alarming was the finding that the more caregivers had learned about ID, the more they believed that those with IDs experienced less pain than those without IDs. The authors suggested several reasons for this finding, including the possibility that the information that was being taught was inaccurate or misunderstood.

Educational materials for caregivers of individuals with IDs should be carefully examined. Caregivers may enter the learning situation already harboring misconceptions. If these are not addressed, they may persist. Underestimation of pain by caregivers of individuals with IDs may result in underreporting of pain to clinicians, leading to undertreatment.

In a literature review, Bottos and Chambers (2006) identified types of pain likely to occur in individuals with IDs. Pain in children with IDs, particularly cerebral palsy, includes gastrointestinal discomfort, such as gastroesophageal reflux and constipation, and musculoskeletal pain. Children with autism also tend to experience gastrointestinal disorders. Individuals with Down syndrome are prone to developing leukemia, hence experiencing all the usual pain associated with the disease, diagnostic tests, and treatment. They also tend to have hip abnormalities and oral health problems such as periodontal disease. In adults with severe to profound mental retardation, pain is more often chronic than acute. An extensive review of the literature about this population revealed that a significant percentage of these people experience significant intensities of pain on a daily basis (Bodfish, Harper, Deacon, et al., 2006).

A review of the literature found that in the adult population of individuals with cerebral palsy, as much as 84% reported one or more types of chronic pain; 56% experienced pain daily and 53% reported moderate to severe pain (Bottos, Chambers, 2006). In one study of 63 women with cerebral palsy, of the 53 who had pain, the most common sites were the head (28%), back (26%), and arms (23%) (Turk, Geremski, Rosenbaum, et al., 1997). Activities of daily living, such as assisted sitting, walking, stretching, toileting, and standing, are especially painful and common, being reported by 35% to 93% of individuals with cerebral palsy (Bottos, Chambers, 2006). Some of the musculoskeletal pain may worsen with aging. It is important to note that studies of the prevalence of pain in adults with cerebral palsy have usually been restricted to those with mild or no cognitive impairment, although those with greater cognitive impairment are not known to be less sensitive to pain or to have fewer types of pain. In fact, the prevalence of pain in children with IDs is higher than in healthy children, and children with greater cognitive impairment tend to experience the most intense and most frequent pain but are least able to communicate their pain (Bottos, Chambers, 2006). Thus, studies suggest that the prevalence of pain in adults with IDs is higher than in adults without IDs.

Assessment of individuals with IDs is extremely challenging and, although considerable research has gone into creating assessment tools for children with IDs, few studies have included adults with IDs. A large majority of adults with IDs achieve a sixth grade level of functioning, so many may be able to provide self-reports of pain, and others with greater cognitive impairment may also be able to self-report. The greatest challenge is the assessment of those without verbal ability. The following studies suggest what to look for as indicators of pain in adults with IDs who cannot self-report.

To identify differences in the pain indicators used by nurses to assess pain in children and adults with severe versus profound IDs, a questionnaire consisting of 158 possible indicators of pain was completed by 109 nurses (Zwakhalen, van Dongen, Hamers, et al., 2004). More than 50% of the nurses found the following seven indicators to be very important: moaning during manipulation, crying during manipulation, painful facial expression during manipulation, swelling, screaming during manipulation, not using the affected body part, and moving the body in “a specific way of behaving.” Pain appeared to be assessed differently in those with severe versus profound IDs. Physiologic indicators, such as gasping for breath, vomiting, and turning red in the face, were scored somewhat higher by the group of nurses specializing in individuals with profound IDs (N = 47). Nurses specializing in the care of persons with severe IDs (N = 42) gave the highest score to “unusual way of crying.” Other indicators used by nurses specializing in the care of those with severe IDs included seeking comfort and being grouchy. (The remaining 53 nurses were taking care of both groups of patients.)

Interviews with eight nurses caring for patients with learning disabilities, who might be in pain but who could not communicate their feelings verbally, identified numerous behaviors they used as indicators of pain (Donovan, 2002). The ages of the patients were not given but some were probably adults because mention was made of nurses’ developing close relationships with patients over a long period of time. Change in facial expression was the most frequently cited nonverbal behavior indicative of pain or distress. Crying was also mentioned frequently. Other behaviors the nurses thought were possible indicators of pain were pacing, out-stretched arms, self-harm such as picking at the skin, aggressive behaviors such as biting or kicking others, pallor, altered rates of breathing, wincing, clenching teeth, and changes in activities such as avoiding weight bearing. One nurse described a patient with limited verbal ability that used the word arm for pain in any part of the body. These nurses emphasized the importance of caring for patients over time so that changes in behavior could be noted. Because changes in usual daily activities are often mentioned as clues to the presence of pain, it is noteworthy that these nurses mentioned that the patients were often determined to carry out normal activities even when seriously injured.

In one study, 40 adults with IDs who were undergoing intramuscular injections were studied to identify the usefulness of facial expressions in detecting pain (LaChapelle, Hadjistavropoulos, Craig, 1999). Only 65% of the subjects were able to provide self-reports. Observing the intensity of facial expressions, specifically brow lowering and chin raising, proved to be useful for assessing pain in these adults. Further, the frequency and intensity of facial expressions did not vary with level of cognitive functioning. In other words, persons with levels of ID that prevented self-report of pain showed facial expressions similar to those shown by persons with less intellectual impairment, providing further evidence against pain insensitivity in persons with IDs.

Somewhat contrary to that study, which found that facial expression did not vary with level of cognitive functioning, another study of adults with IDs found that facial expressions differed in individuals with mild to moderate cognitive impairment compared to those with severe to profound ID (Defrin, Lotan, Pick, 2006). In a study of 159 adults with varying levels of mental retardation and a control group of 38 with normal cognition, behavior was observed before and during the painful stimulus of a vaccination. During the vaccination, facial expression increased in those with mild to moderate IDs and in those without impairment. However, in those with severe to profound impairment, 47% to 50% exhibited stillness, or a “freezing reaction” (face and body not moving for several seconds), suggesting that pain assessment tools based only on facial expressions might contribute to the misconception that these patients are insensitive to pain. An increase in cognitive impairment was associated with a significant increase in freezing. In a few patients, freezing was accompanied by a full-blown smile, and some laughed, reactions that could easily be misinterpreted as insensitivity to pain. Freezing was exhibited by only 8% to 13% of individuals with mild to moderate IDs.

One reason for the differing conclusions in the studies described may be related to the sizes of the samples. It is possible that the study of 40 adults (LaChapelle, Hadjistavropoulos, Craig, 1999) did not include a large enough sample to allow for the detection of differences in behavior among the levels of ID, whereas the study of 159 adults with IDs (Defrin, Lotan, Pick, 2006) did allow for such detection.

Two behavioral pain scales were used in the study of 159 adults with ID: the Non-Communicating Children’s Pain Checklist-Revised (NCCPC-R) and the Facial Action Coding System (FACS) (Defrin, Lotan, Pick, 2006). The FACS is impractical to use in daily clinical practice because it involves coding video tapes. The NCCPC-R involves observing and rating behaviors (over a 2-hour period) and was found to be more sensitive to changes occurring in individuals at all levels of cognitive functioning, whereas the FACS was more sensitive to those with mild to moderate IDs. The NCCPC-R consists of 30 behaviors divided into seven categories: vocal, eating/sleeping, social, facial, activity, body/limb, and physiologic signs (Breau, McGrath, Camfield, et al., 2002). An observer scores the frequency of occurrence of the behaviors on a scale of 0 to 3: not at all, just a little, fairly often, and very often. The NCCPC-R was found to be reliable for measuring acute pain in adults with IDs.

One problem with the NCCPC-R is that it was validated by using a 2-hour observation period, which is impractical in many clinical settings. For that reason Breau, McGrath, and Zabalia (2006) recommend using the Non-Communicating Children’s Pain Checklist-Postoperative Version (NCCPC-PV) over a 10-minute period when a 2-hour period is not feasible. Research using the NCCPC-PV in adults with IDs and acute pain is needed. A variety of versions of the NCCPC are currently being researched in various populations with IDs. So far, the NCCPC-R and the NCCPC-PV have the greatest support for use with children because of their psychometric properties.

Assessment of location of pain may be difficult, especially in those with Down syndrome. In a study involving cold stimuli applied to the wrists and the temples of 26 individuals with Down syndrome, all were able to express themselves verbally but had some difficulty locating the site of the cold stimuli (Hennequin, Morin, Feine, 2000). In a later study of parents’ perceptions of pain in their children with Down syndrome (ages 1 to 39 years), the parents reported having greater difficulty in identifying locations of pain in their children with Down syndrome than in their children without Down syndrome (Hennequin, Faulks, Allison, 2003). Their abilities improved as the children grew older.

Two of the pain assessment tools that have been researched in adults with severe to profound mental retardation are the Pain and Discomfort Scale (PADS) (developed from the NCCPC-R) and the Pain Examination Procedure (PEP), and it is recommended that they be used together (Bodfish, Harper, Deacon, et al., 2006). These tools have acceptable levels of reliability and validity. The research into the development of these tools is extensive and is summarized in the chapter by Bodfish and others (2006) cited earlier. Studies indicate that the PADS is sensitive to nonverbal signs of pain in adults with severe IDs and is sensitive to everyday pain, acute pain responses, chronic pain, and effects of treatments to relieve pain. The authors found that administering the PADS plus the PEP takes trained personnel approximately 10 minutes. However, training for administering the PADS and PEP is extensive. A CD-ROM that includes a manual and workbook for the PADS and a DVD training video are available by calling 919-966-4896.

Other researchers disagree with the soundness of using the PADS in adults with IDs (Burkitt, Breau, Salsman, et al., 2009). They state that research to date is insufficient to support the general use of the PADS with adults with IDs. Indeed, further research is needed to identify pain assessment tools for this population. Meanwhile, the PADS plus the PEP may be a good alternative to using no tool at all.

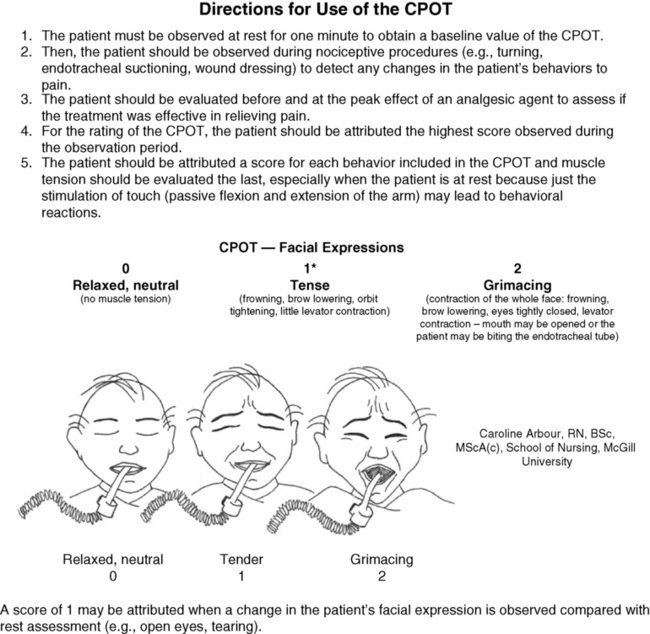

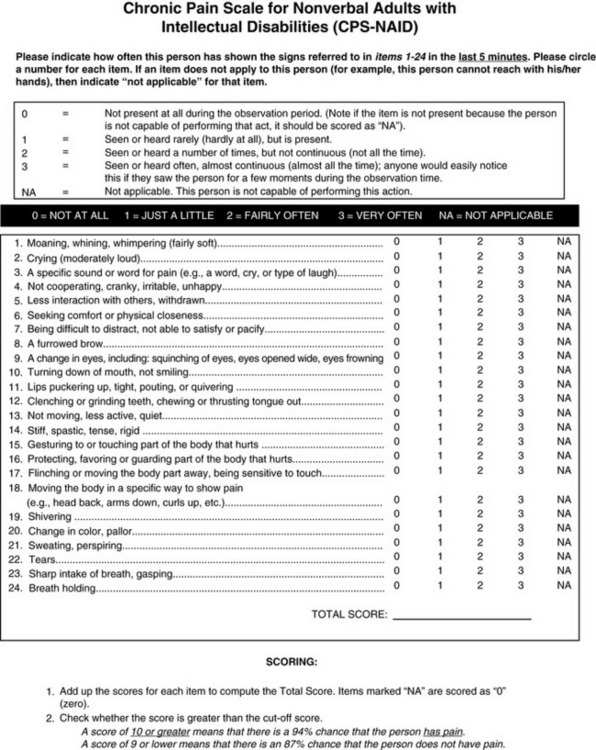

Another potential tool, the Chronic Pain Scale for Nonverbal Adults with Intellectual Disabilities (CPS-NAID) (Form 4-2), is being researched (Burkitt, Breau, Salsman, et al., in press; reported in Breau, Burkett, 2009). This scale was arrived at by having two observers use the NCCPC-R to observe 16 nonverbal adults with IDs and chronic or recurrent pain conditions for a period of 5 minutes under conditions of pain and no pain. The observers also rated the pain using a VAS. Analyses indicated that six items should be removed from the NCCPC-R, resulting in a 24-item scale. This yielded 94% sensitivity to pain and 87% specificity for the presence of pain. These researchers concluded that the CPS-NAID has sound psychometric properties and can be used to assess chronic pain in adults with IDs. They think that this tool is superior to the original NCCPC-R, but further studies are needed to compare the two.

Form 4-2 As appears in Pasero, C., & McCaffery M. (2011). Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 152, St. Louis, Mosby. From Burkitt, J. C., Breau, L. M., Salsman, S., et al. (2009). Pilot study of the feasibility of the non-communicating children’s pain checklist revised for pain assessment for adults with intellectual disabilities. J Pain Manage, 2(1).

An attempt was made to establish cutoff points for pain on the basis of the total score of the CPS-NAID. However, it was based on proxy pain reports. As mentioned previously, in the section on behavioral scales for cognitively impaired adults, given current knowledge, scores on behavioral pain scales do not equate with pain-intensity scores (Pasero, McCaffery, 2005). In most studies of pain assessment tools, there are low correlations between proxy judgments of pain severity and patients reports of severity. This raises concern about comparing pain-behavior scores with pain-intensity scores. If clinicians could reliably determine the intensity of pain in patients who cannot self-report, there would be no need for a behavioral assessment tool (Zwakhalen, Hamers, Abu-Saad, et al., 2006).

The hierarchy of pain assessment techniques (see Box 3-9, p. 123) is helpful in the assessment of patients with IDs. Following are the steps in that hierarchy, with comments related to assessing adults with IDs, starting with attempts to obtain self-reports.

• Try to obtain a self-report. A large majority of adults with IDs achieve a sixth grade level of academic skill and may be able to use some of the self-report scales mentioned in the section on self-report tools for adults who have difficulty with the commonly used tools such as the 0 to 10 NRS (pp. 92-95).

• Identify pathologic conditions and procedures that commonly cause pain, paying particular attention to those sources of pain characteristic of the type of ID. For example, individuals with cerebral palsy or autism often experience gastrointestinal discomfort such as gastroesophageal reflux. Individuals with Down syndrome are prone to developing leukemia, with all the usual pain associated with the disease and its treatment. Chronic pain is very common, one source being musculoskeletal pain in cerebral palsy.

• Observe behaviors indicative of pain. Changes in facial expression, especially brow lowering and chin raising, are probably the most frequently cited indicators of pain in persons with IDs, and they do not seem to vary with the level of cognitive functioning. Numerous other behaviors are cited in research into pain in adults with IDs. Some behaviors indicative of pain are unconventional, such as kicking others, picking at own skin, or freezing. Consider using the CPS-NAID (see Form 4-2) to assess chronic pain in adults with IDs.

• Physiologic indicators such as vital signs are not usually very helpful in assessing pain, but in the ID literature physiologic indicators often refer to the following behaviors, which may be helpful in assessing individuals with severe or profound IDs: gasping for breath, vomiting, and becoming red in the face.

• Obtaining information from caregivers who know the patient well, sometimes over a period of years, is a common way of assessing pain in individuals with IDs and is high on the hierarchy of pain assessment.

• Finally, when in doubt about the presence of pain or when wanting to confirm the suspicion of pain, an analgesic trial may be helpful. Assess for changes in behavior following use of an analgesic. (See Box 3-11, p. 126, for suggestions concerning analgesic trials.)

Patients Who Are Mentally Ill

Most of this part of the chapter focuses on assessment of pain in patients who have one of two mental disorders: (1) schizophrenia, in which decreased sensitivity to pain (hyppoalgesia) or impaired pain responsiveness has been documented in some patients (Singh, Giles, Nasrallah, 2006); and (2) posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), in which both decreased and increased sensitivity to pain have been reported(Geuze, Westenberg, Jochims, et al., 2007). The occurrence and the perception of pain in persons who have these two mental disorders are examined. Depression and anxiety in relation to pain are discussed briefly in Chapter 2 (pp. 31-32).

Schizophrenia

The extent of apparent insensitivity to pain in patients with schizophrenia can be extreme, as revealed in some clinical case reports. One such example is a patient with diagnosed schizophrenia for 20 years who burned his arm so severely it had to be amputated (Virit, Savas, Altindag, 2008). The patient explained, “I put my hand on the burning flames of the LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) cylinder in order to get warm…. I did not feel any pain” (p. 384).

Insensitivity to pain by schizophrenic patients has been suggested for more than 100 years, and failure to respond to pain is clearly associated with increased morbidity and mortality rates. A literature review of physical diseases in patients with schizophrenia documented the long-held observation that many types of physical illness, such as CV diseases, HIV infections, and dental problems, are more common in these patients than in the general population (Leucht, Burkard, Henderson, et al., 2007). This is thought to be caused in part by the stigma attached to patients with schizophrenia; it leads to undertreatment. Further, the tendency to ascribe patients’ expressions of physical illness to the mental illness sometimes leads to missing a medical diagnosis. In addition, patients themselves simply fail to report symptoms of physical illness. It appears that patients with schizophrenia who fail to respond to pain also seek medical care at later stages of disease. For example, in a small study of 55 patients with schizophrenia undergoing appendectomy, 34 appendixes were perforated and 9 were gangrenous (Cooke, Magas, Virgo, et al., 2007).

In a literature search for studies of postoperative complications in seriously mentally ill patients, 10 studies relating to patients with schizophrenia were identified (Copeland, Zeber, Pugh, et al., 2008). Of the studies, 9 had fewer than 100 patients, but one large retrospective study included 466 patients with schizophrenia and 338,257 patients without schizophrenia (Daumit, Pronovost, Anthony, et al., 2006). Those with schizophrenia had higher rates of postoperative complications, such as respiratory failure and deep-vein thrombosis, than did patients without schizophrenia. Again, it appears that patients with schizophrenia are insensitive to pain and seek medical care at later stages of disease.

One small study of 50 schizophrenic patients and 25 controls found that those with schizophrenia reported significantly lower pain intensity postoperatively and consumed 60% less analgesic medication (Kudoh, Ishihara, Matsuki, 2000). This shows that schizophrenic patients seem to be less responsive to postoperative pain. Nevertheless, postoperative pain in schizophrenic patients is a risk factor for postoperative confusion (Kudoh, Takahira, Katagal, et al., 2002), which occurs more commonly in schizophrenic patients than in those without schizophrenia. Although pain scores do not reflect very much conscious awareness of pain, adequate postoperative pain relief is necessary to prevent postoperative confusion (Kudoh, 2005).

The lack of responsiveness to pain of schizophrenic patients is poorly understood. One way of comprehending the denial of pain and the low pain ratings in the presence of noxious stimuli that ordinarily cause severe pain is that the mental illness overwhelms the patient’s thought processes (e.g., hallucinations, intrusive thoughts), and the patient simply does not focus on pain. Patients with schizophrenia also may be preoccupied with their psychotic symptoms and may suffer from fatigue and a lack of drive, consequently failing to seek help for physical symptoms (Leucht, Burkard, Henderson, et al., 2007). Some studies find that patients with schizophrenia, when compared to healthy controls, have higher sensory perception thresholds, such as the perception of warmth and the onset of thermal pain. This trait seems to be caused by abnormalities in information processing (Jochum, Letzsch, Greiner, et al., 2006). The tests for these sensations required sustained attention, and the researchers noted that the patients had difficulty focusing. A review of 12 studies of individuals with schizophrenia revealed that their responses to experimental pain were diminished (Potvin, Marchand, 2008).

Antipsychotic medications have sometimes been thought to have analgesic effects, and that could help explain seeming decreased sensitivity to pain in individuals with schizophrenia. However, in the previously mentioned study, antipsychotic medications did not alter the finding of high sensory thresholds. Drug-free patients also had hypoalgesic responses. Therefore, hypoalgesia could not be explained solely by the effects of antipsychotic drugs (Potvin, Marchand, 2008).

Another explanation for hypoalgesia is derived from a review of the literature that suggests that seeming pain insensitivity may be a familial trait rather than a function of the psychotic state (Singh, Giles, Nasrallah, 2006). One study compared the responses to finger pressure by college students who did not have diagnoses of schizophrenia, but who had relatives who did, with the responses of students with no family history of schizophrenia (Hooley, Delgado, 2001). Pain threshold and tolerance were higher in the healthy adults who had relatives diagnosed with schizophrenia, suggesting that pain insensitivity may be a familial trait.

To summarize, apparent insensitivity to pain in patients with schizophrenia may reflect a true lack of pain sensitivity or may be caused by other factors such as failure to focus on pain or respond to pain in the presence of a psychotic state. Unfortunately, a review of the literature did not produce sufficient evidence of whether hypoalgesia is present in schizophrenic patients when they are stable as well as during acute phases of psychosis (Potvin, Marchand, 2008).

More recently, researchers have questioned whether some patients with schizophrenia are insensitive to pain or just seem insensitive to pain because of communication impairments that accompany schizophrenia (Bonnot, Anderson, Cohen, et al., 2009). A review of the scientific literature on pain in patients with schizophrenia yielded 431 articles, of which 57 were considered relevant to examining sensitivity to pain. These included 9 case reports, 23 clinical studies, 20 experimental research, and 5 review articles. Only 1 experimental study used a neurophysiologic measure of pain reactivity, and it showed a normal pain threshold in schizophrenia. Misconceptions about patients with schizophrenia being insensitive to pain are probably derived from observations that many of these patients show reduced pain reactivity in the form of decreased behavioral responses and self-reported pain.

How can pain be assessed in patients who do not report pain or report low intensities of pain? A survey was conducted of 74 staff members of a geriatric psychiatry service to explore pain assessment and management issues in that population (Stolee, Hillier, Esbaugh, et al., 2007). Part of the survey consisted of a list of 37 potential indicators of pain, and staff were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed that these could be indicators of pain. Those pain indicators that were endorsed most often were facial grimacing or wincing, verbal pain complaints, diagnoses of painful conditions (such as arthritis), body positioning, and groaning or moaning. The accuracy of these indicators of pain was not assessed. Also, in this population of patients both mental illness and cognitive impairment existed, so the extent to which each condition influenced the perception of pain is unknown. However, the majority of respondents (more than 80%) were not so much interested in specific behaviors but rather in identifying changes in usual behaviors as indicators of pain in patients with mental illness. This preliminary research provides a clue to the assessment of pain in patients with schizophrenia, namely, notation of changes in the patients’ usual behaviors.

Many behaviors, such as personality changes, sleep disturbances, and fatigue, may occur as the result of either pain or exacerbations in mental illness (McCaffery, Pasero, 2001; Rutledge, Donaldson, 1998). Because apparent insensitivity to pain and impaired pain responsiveness are common in mental illness, it is recommended that such behaviors be interpreted as potential indicators of pain and that the pain be treated first, before attempting to determine whether the behaviors are a result of a mental disorder.

The finding of the appearance of insensitivity to pain in many, but not all, patients with schizophrenia presents clinicians with assessment challenges. In some ways assessment is comparable to that in previous recommendations that pain in nonverbal patients and those unable to respond with behavioral indicators should be assumed and treated when usually painful underlying pathologies or procedures are present. Because pain is rarely experienced as a hallucination (Watson, Chandarana, Merskey, 1981), any report of pain should always be taken seriously.

The assessment of pain in patients with schizophrenia should not differ from the assessment of pain in mentally healthy individuals. For example, if an institution’s policy recommends assessment of pain during every shift, it should also be done on units caring for patients with mental illness, bearing in mind that a patient with schizophrenia may deny pain, even in the presence of a disease known to be painful such as an infected appendix.

For the assessment of pain in adult patients with schizophrenia, information from the previous discussion can be applied to the hierarchy-of-pain assessment techniques, Box 3-9 (p. 123), as follows:

• As in all patients, give priority to obtaining self-reports of pain. Beware of ascribing reports of pain to the mental illness. If reports of pain are ignored, diagnosis of physical illness may be delayed, subjecting a patient to complications such as a ruptured appendix. Pain is rarely a hallucination. In fact, clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion of pain in these patients because they are known for late reporting of the symptoms of physical illnesses.

In schizophrenic patients with the intellectual capacity for self-reporting of pain, reports of no pain or mild pain may indicate lack of responsiveness to pain, not lack of pain. However, each patient should be assessed for a history of lack of responsiveness to pain.

• Identify pathologic conditions and procedures that commonly cause pain such as surgery. Consider obtaining a consultation for assistance in diagnosing a physical illness. Clinicians skilled in the care of patients with mental illness may not be as skilled in the detection of physical illness.

• Observe behaviors indicative of pain. Consider the possibility that pain is present when changes in patients’ usual behaviors occur, such as increased fatigue, sleep disturbances, postoperative confusion, or personality changes. In one study, clinicians identified facial grimacing or wincing and groaning or moaning as common indicators of pain. Studies have shown that clinicians value changes in usual behavior as the most important indicators of pain. “Absence of pain reactivity does not mean absence of pain sensitivity” (Bonnot, Anderson, Cohen, 2009, p. 246).

• Obtain information from caregivers and medical records regarding past or current pain, potential causes of pain, and any indications of lack of responsiveness to pain.

• Finally, when in doubt about the presence of pain or when wanting to confirm the suspicion of pain, an analgesic trial may be helpful. Behavior changes that could be caused by either pain or exacerbation of mental illness should first be treated as pain before initiating treatment for the mental illness. Assessment of behavior after a trial use of analgesic may help to determine whether changes in behavior are due to a physical illness or to the mental illness.

In conclusion, when addressing the problem of pain in patients with serious mental illness, two important considerations are (1) patients with chronic pain who also have mental disorders have a poorer quality of life than those without mental disorders; and (2) better treatment outcomes are likely when both pain and the mental illness are treated than when only one or the other is treated (Nicholas, 2007). Thus, whether the mental illness causes pain or is a consequence of pain, both pain and the mental illness should be treated.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an anxiety disorder that can occur following an extremely traumatic event that involves being threatened by or witness to a situation that involves death or injury (APA, 1994). Traumatic events may include military combat, physical attacks, torture, or severe automobile accidents. The prevalence rates of individuals’ at risk for developing PTSD, such as combat veterans and victims of criminal violence, range from 3% to 58%.

Soldiers returning from the Iraqi war report very high levels of combat exposure, with 90% describing being shot at and a high percentage report handling dead bodies, knowing someone who was injured or killed, or killing an enemy combatant (Hoge, Castro, Messer, et al., 2004) Research has shown that soldiers with extensive combat exposure are four times more likely to develop PTSD than those with low combat exposure (Kulka, Schlenger, Fairbank, et al., 1990). In a convenience sample of Iraqi veterans, 71% had pain, 57% had PTSD, and 64% had mild traumatic brain injury; 36% had all three (Tan, Fink, Dao, et al., 2009). This population also displayed compromised autonomic nervous system function, suggesting that autonomic abnormality may contribute to, result from, or be a useful marker of symptoms of pain in traumatic brain injury and PTSD.

Soon after a traumatic event, “psychic numbing” or “emotional anesthesia” occurs; it is a symptom of decreased responsiveness to the external world (APA, 1994). Symptoms of PTSD usually begin within the first 3 months of the precipitating event, and approximately half of patients experiencing such symptoms completely recover within 3 months, whereas many others have persistent symptoms for longer than 12 months. PTSD is characterized by distress or impairment in functioning, socially or occupationally; persistent anxiety; sleep disturbances; and recurrent nightmares about the traumatic event. The patient may develop hypervigilence, irritability, exaggerated startle responses; and difficulty concentrating. When persons are exposed to events that are reminders of the original traumatic event, extreme psychologic distress or physiologic reactions commonly occur. Usually, they make deliberate efforts to avoid all reminders.

The prevalence of PTSD has been estimated to be between 6% and 9% or more in the general population of the United States (Breslau, 2001). Unfortunately, PTSD is much more common and is often underdiagnosed in primary care and mental health settings. For example, in a study of 295 psychiatric outpatients, 46% had PTSD but only 7% were diagnosed as such by physicians (Villano, Rosenblum, Magura, et al., 2007).

The presence of high levels of pain during the peritrauma period has been associated with increased risk for the development of PTSD (Norman, Stein, Dimsdale, et al., 2008). Related to this finding is a study of 24 children admitted to the hospital for acute burns (Saxe, Stoddard, Courtney, et al., 2001). The children were assessed for PTSD while in the hospital and 6 months after discharge. All children received morphine, but those who received higher doses of morphine showed greater reduction in PTSD symptoms over 6 months. It is interesting that in another study, of 147 soldiers in Iraq who were treated in a military treatment center for burns and had had at least one surgery, 119 who had received ketamine during surgery were compared with 28 who had not (McGhee, Maani, Garza, et al., 2008). The prevalence of PTSD was 27% in those who had received ketamine and 46% in those who had not received ketamine despite the fact that their burns were larger and their injury severity scores higher. A pilot study of placebo versus 40 mg of propranolol (Inderal) four times a day following acute, psychologically traumatic events found that propranolol had a preventive effect on subsequent PTSD (Pitman, Sanders, Zusman, et al., 2002). This offers the hope that ketamine, propranolol, morphine, or perhaps some other medications can be used soon after trauma or injury to prevent or reduce the symptoms of PTSD.

When PTSD involves a physically painful injury, it has been suggested that pain may be a flashback to the original traumatic injury (Asmundson, Coons, Taylor, et al., 2002). Therefore, it may be possible to prevent or minimize the development of pain-related PTSD flashbacks by assessing pain and treating it with analgesics at an early stage. Another small study (N = 6) of veterans with both chronic pain and PTSD examined the effects of using components of cognitive processing therapy for PTSD and cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain (Otis, Keane, Kerns, et al., 2009). A 12-session integrated treatment for veterans with both chronic pain and PTSD was developed and used by the participants. Although half the participants withdrew from the study, participants appeared to benefit from the treatment, and further research is being conducted to evaluate the efficacy of this approach.

PTSD and chronic pain often occur together and are frequently observed within the Department of Veterans Affairs health care system (Otis, Keane, Kerns, 2003). When patients with PTSD are being assessed, chronic pain is commonly identified, regardless of the nature of the traumatic experience, and vice versa; when patients with chronic pain are being assessed, PTSD is commonly found too (Asmundson, Coons, Taylor, et al., 2002; Schwartz, Bradley, Penza, et al., 2006). In a study of 295 psychiatric outpatients, 24% had both PTSD and chronic severe pain (Villano, Rosenblum, Magura, et al., 2007). In another study of 85 veterans seeking treatment for PTSD, 66% had chronic pain diagnoses (Shipherd, Keyes, Jovanovic, et al., 2007).

Unfortunately, because of the stigma placed on seeking psychiatric help, most veterans do not seek help from this source. If they develop painful conditions, they are more likely to seek help from pain clinics (DeCarvalho, Whealin, 2006). Because PTSD may hamper treatment for chronic pain, pain specialists should know about the possibility that PTSD can coexist with chronic pain and should watch for symptoms, such as being easily startled, hypervigilence, isolation, and use of alcohol or other substances to deal with PTSD or pain. An appropriate screening tool for PTSD should be used.

Studies have reported both increased and decreased sensitivity to pain in individuals with PTSD (Geuze, Westenberg, Jochims, et al., 2007). Decreased sensitivity to pain in patients with PTSD has been documented in only a few experimental studies. In a small study of 12 veterans with PTSD and 12 without PTSD, neuroimaging was done while each group was exposed to heat stimuli (Geuze, Westenberg, Jochims, et al., 2007). Subjects rated pain using an NRS of 0 to 100. Compared to controls, individuals with PTSD rated the heat stimuli as being significantly less painful, and neuroimaging revealed an analgesic response and altered pain processing in certain brain areas.

In another small, double-blind, crossover study, eight Vietnam veterans with PTSD and a control group of eight veterans without PTSD, matched for combat severity, watched a videotape of dramatized combat (Pitman, van der Kolk, Orr, et al., 1990). None were receiving opioid analgesics. The tape was viewed by each group while under the effects of naloxone hydrochloride or placebo. In the placebo condition, those with PTSD experienced a 30% decrease in pain ratings, but no decreases in pain ratings occurred in the naloxone condition, which suggests that naloxone blocked endogenous opioid analgesia. The veterans without PTSD showed no decrease in pain ratings under either condition. It appeared that veterans with PTSD had opioid-mediated analgesic responses (endogenous opioids). Thus, decreased sensitivity to pain in patients with PTSD appears to occur briefly when a patient is exposed to acute pain or something that triggers memories of or reminds the patient of the original trauma.

Patients with PSTD and chronic pain tend to have increased sensitivity to pain. The mechanisms most often proposed to understand the cooccurrence of chronic pain and PTSD are shared vulnerability and mutual maintenance (Asmundson, Coons, Taylor, et al., 2002). For example, in terms of the concept of shared vulnerability, it seems possible that anxiety sensitivity is shared by patients with both PTSD and chronic pain. With respect to the concept of mutual maintenance, it seems possible that certain cognitive or affective components of chronic pain exacerbate symptoms associated with PTSD and that certain affective and behavioral components of PTSD exacerbate symptoms associated with chronic pain.

Analysis of pain intensity was compared in three groups, all members of which had chronic pain; but one group had accident-related pain and high PTSD symptoms, one group had accident-related pain and few or no symptoms of PTSD, and the third group had pain that was not accident related and had no symptoms of PTSD (Geisser, Roth, Bachman, et al., 1996). Patients with accident-related pain and strong PTSD symptoms reported higher levels of pain than did the other two groups.

To examine sensitivity to pain, three groups of subjects—32 outpatients with combat- and terror-related PTSD, 29 outpatients with anxiety disorder, and 20 healthy individuals—were compared (Defrin, Ginzburg, Solomon, et al., 2008). The first two groups were randomly selected from an outpatient psychiatric clinic and contacted by telephone to request participation in the study. Higher rates of chronic pain, more intense chronic pain, and more painful body regions were found in the subjects with PTSD than in the other two groups. Further, the greater the severity of PTSD, the greater the severity of chronic pain.

A review of the literature also confirms this finding (Smith, Egert, Winkel, et al., 2002). In addition to being at high risk for PTSD, individuals with persistent pain who do develop PTSD are also likely to experience more intense and pervasive pain than those who do not develop PTSD.

In the study by Defrin and others (2008), differences emerged when the groups were tested for measurement of warmth, cold, light touch, and heat-pain thresholds and for responses to acute suprathreshold heat and mechanical stimuli. Although the patients with PTSD were less sensitive to thresholds for warmth, cold, touch, and heat-pain than the other two groups, they found the suprathreshold heat and mechanical stimuli much more intense than did the other groups. The researchers offered several possible explanations for this paradoxical finding, such as altered sensory processing in subjects with PTSD, and recommended further research. Other researchers suggest that the increased sensitivity to suprathreshold pain may reflect in part that the subjects were exposed to this type of pain for a longer time (repeated painful stimuli) in the experimental situation than when tested for the heat-pain threshold in which they were simply asked to identify the point at which the heat stimulus became painful (Asmundson, Katz, 2008).

A study of 145 individuals with diagnoses of HIV/AIDS who also had persistent pain was conducted to examine the relationship between PTSD and pain (Smith, Egert, Winkel, et al., 2002). In this sample, approximately half (51.8%) had diagnoses of PTSD. Individuals with PTSD reported higher levels of pain at its worst, worse physical and mental health, and higher levels of pain that interfered with daily activities and mood than did those without PTSD. One obvious implication of the study is that individuals with HIV should be assessed for symptoms of PTSD.

A study of 93 patients diagnosed with the chronic pain condition of fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) was undertaken to determine the prevalence of PTSD-like symptoms (not the diagnostic category of PTSD) and to evaluate the relationship between PTSD symptoms, FMS symptoms, and disability (Sherman, Turk, Okifuji, 2000). More than half (56%) of the sample reported significant levels of PTSD-like symptoms, and this group reported significantly greater levels of pain, interference with life, emotional distress, difficulty adapting to FMS, depressive symptoms, and disability than did individuals without clinically significant levels of PTSD symptoms. Another study of PTSD and FMS yielded similar results. The frequency of occurrence of PTSD was examined in 77 patients with FMS, and 57% were found to have significant levels of PTSD symptoms (Cohen, Neumann, Haiman, et al., 2002). The most frequently reported traumatic event associated with PTSD was the unexpected death of a loved one (as is true for the other patients with PTSD). These patients did not regard their FMS as a traumatic event.

Clearly PTSD symptomatology is prevalent in individuals with FMS and probably has a negative impact on coping with FMS, suggesting that interventions for the treatment of PTSD, such as stress management, may be helpful for patients with FMS. These interventions overlap with interventions for persistent pain and probably can be incorporated easily in a pain management program for patients with FMS.

The relationship between analgesic use and PTSD was studied in 173 African-Americans who were outpatients at a mental health center (Schwartz, Bradley, Penza, et al., 2006). Those with PTSD, 43.5% of the sample, used significantly more opioid and nonopioid analgesic medications than did those who did not have PTSD. Of the patients with PTSD, 68% were prescribed analgesics, and 59% received opioids, whereas only 51% of patients without PTSD received analgesics, 42% of them receiving opioids. (Pain ratings were not reported in this article.) Patients receiving opioids had the highest severity of PTSD symptoms. PTSD was notably underdiagnosed in this group of patients; only 6.5% of the total sample had documented diagnoses of PTSD.

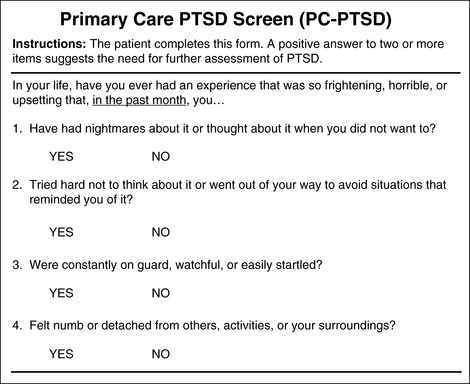

Chronic pain and PTSD often coexist, and PTSD exacerbates chronic pain but is frequently underdiagnosed. It is therefore critical to assess patients with chronic pain for the symptoms of PTSD and to assess patients with PTSD for chronic pain. This makes it possible to recognize and arrange for both the pain and the PTSD to be addressed. A convenient screening tool for PTSD in the primary care setting is the Primary Care PTSD (PC-PTSD) screen shown in Form 4-3 (Prins, Quimette, Kimerling, et al., 2003). It is psychometrically sound, identifying PTSD in 78% of 188 men and women in a primary care setting at the Veterans Administration. It is brief, written at an eighth grade reading level, and easy to score. It consists of four yes/no questions, and a positive answer to two or more items suggests the need for further assessment of PTSD.

Form 4-3 As appears in Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. (2011). Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 158, St. Louis, Mosby. Used with permission. From Prins, A., Ouimette, P., Kimerling, R., et al. (2003). The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): Development and operating characteristics. Prim Care Psychiat, 9(1), 9-14. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

Based on the previous discussion of PTSD, suggestions for assessment of pain and PTSD, along with possible prevention of or decrease in symptoms of PTSD are as follows:

• Obtain self-reports of pain as indicated in the hierarchy of pain assessment techniques (see Box 3-9, p. 123). PTSD itself does not seem to hinder the ability to provide a self-report of pain, but chronic pain is often underdiagnosed, although it is common in patients with PTSD. Other steps in the hierarchy of pain assessment should be followed if self-report is hampered by some other condition such as brain injury.

• At times of extremely traumatic events, assess for pain and, if present, treat it aggressively in the hope of preventing or decreasing the symptoms of PTSD. If individuals are unable to respond at the time of the traumatic event and physical stimuli suggest that pain is present, assume that pain is present and treat it aggressively as a prophylactic measure

• Clinicians treating patients with PTSD should assess for the cooccurrence of chronic pain.

• Clinicians treating patients with chronic pain, especially soldiers with long exposure to combat, should assess for the cooccurrence of PTSD or PTSD symptomatology. Watch for symptoms such as hypervigilence, isolation, being easily startled, and use of alcohol and other drugs to cope with pain or PTSD. A useful screening tool is PC-PTSD (Form 4-3).

• If a patient with PTSD also has pain, recognize the possibility of increased sensitivity to pain, higher pain ratings, and the need for more analgesia than required by other patients with comparable injuries but no PTSD.

• Be alert to diagnoses such as the HIV and advanced cancer that expose individuals to a number of psychologically traumatic events, such as receiving the diagnosis, disclosing the diagnosis to others and, in some cases such as infection by HIV, infecting significant others. Assess for symptoms of PTSD and chronic pain.

To summarize the implications of these assessment suggestions, when PTSD or PTSD symptomatology and pain cooccur, a cognitive-behavioral therapy program is appropriate but will have to be modified to address both problems (Asmundson, Coons, Taylor, et al., 2002). No data yet exist to suggest that either PTSD or chronic pain should be treated first when they cooccur. Thus, treating the conditions simultaneously seems indicated.

Specific treatment of coexisting pain and PTSD is beyond the scope of this chapter, but DeCarvalho and Whealin (2006) suggest additional practical ideas that can be quickly initiated after PTSD is suspected. Educate the patient about the symptoms of PTSD, and provide written materials when possible. One short patient education sheet about chronic pain and PTSD can be obtained from http://www.ncptsd.va.gov/ncmain/ncdocs/fact_shts/fs_chronic_pain_and_patients.html?opm=1&rr=rr102&srt=d&echorr=true. When possible, give returning service members with pain and possible PTSD the option of attending a military or a civilian pain clinic. This may reduce their fear of stigmatization. Relaxation therapy may be helpful, although some patients find that it allows for disturbing intrusive thoughts.

Cultural Considerations

As racial and cultural diversity increases in the United States, clinicians are increasingly likely to care for patients from backgrounds quite different from their own. There is little doubt that various ethnic groups express pain and suffering differently. The same can be said of people in general. Fortunately, many of the pain assessment tools used in English in the United States can be used successfully in other cultures if they are translated into the appropriate languages. Culture affects behavioral responses to pain and treatment preferences. However, patients of many different cultures may be assessed using similar pain assessment tools, and the findings will have similar meanings across cultures. Following is a reminder of some of the assessment tools discussed in this section that have been used in other cultures.