Misconceptions that Hamper Assessment and Treatment of Patients Who Report Pain

Patient versus Caregivers/Family

Health Care Conditions that Influence Clinicians’ Judgments of Pain

Pain Threshold: Uniform versus Variable

Pain Tolerance: High versus Low

Behavioral and Physiologic Responses to Pain

Acute Pain Model versus Adaptation

Responses Clinicians Expect of Patients with Pain

Patients’ Knowledge of Clinicians’ Expectations of Pain Behaviors

Correction of the Misconceptions Concerning the Acute Pain Model

Seeking Drugs versus Seeking Pain Relief

Definitions Related to Addiction

Likelihood of Occurrence of Addictive Disease

Addiction as a Stigmatizing Label: Societal versus Medical Views

Misconceptions about the Meaning of Positive Placebo Responses

Misconceptions about Using Placebos for Pain Relief

Recommendations against the Use of Placebos

REGARDLESS of what patients say about their pain, the subjectivity of pain seems to invite speculation from everyone—clinicians, families, and acquaintances—about the “true” nature of patients’ pain. Numerous reasons are given by clinicians to explain why they find it difficult to accept some patients’ reports of pain and why they fail to respond with appropriate treatment. These reasons include lack of a known cause for the pain or lack of behavioral indicators such as grimacing. Still other reasons remain less obvious, often below the level of awareness, but still cause clinicians to have doubts. For example, the patients’ gender or ethnic origins may unknowingly influence clinicians’ decisions about pain management.

Subjectivity of Pain

Patient versus Caregivers/Family

Who is the authority on patients’ pain? Whose pain is it? Clinicians sometimes believe they know more about the patient’s pain than the patient does. No matter how appealing that belief may be, it is false. Nevertheless, privately or among themselves, clinicians may comment about a patient, “He doesn’t have as much pain as he thinks he does” or “The pain is not that bad,” implying that the clinicians are the true authorities on patients’ pain. In research cited earlier, clinicians’ tendencies to underestimate patients’ pain is noted.

No objective measures of pain exist. The sensation of pain is completely subjective. Pain cannot be proved or disproved. One definition of pain used in clinical practice says “Pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever he says it does” (McCaffery, 1968, p. 95). Statements by the American Pain Society (APS) have echoed the same approach to patients’ reports of pain by statements such as:

• “The clinician must accept the patient’s report of pain.” (APS, 2003, p. 1)

• “Self-report should be the primary source of pain assessment when possible.” (APS, 2003, p. 33).

• “…the patient’s self-report should be used as the foundation for the pain assessment.” (Miaskowski, Cleary, Burney, et al., 2005, p. 19)

The gold standard for assessing the existence and intensity of pain is patients’ self-reports. No other source of information has ever been shown to be more accurate or reliable than what a patient says. Patients’ behaviors, the opinions of nurses and physicians delivering care, patients’ vital signs—none of these is as reliable as patients’ reports of pain and should never be used instead of what a patient says.

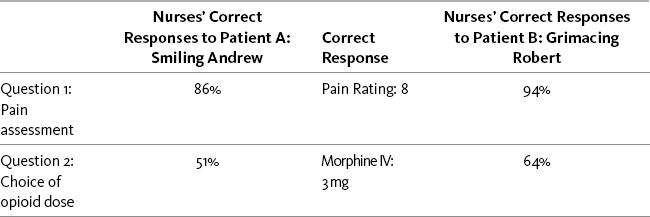

The Andrew-Robert survey presented in Box 1-1 (p. 18) illustrates what happens when clinicians do not adopt the patient’s self-report as the standard for assessment of pain intensity. This survey has been used by many nurse educators in hundreds of educational programs to explain the necessity of accepting the patient’s report of pain as the standard for assessment. The survey has become so familiar to staff nurse educators that it is often referred to simply as the Andrew-Robert survey. Several publications have reported the results of studies using this survey and modifications of it (McCaffery, Ferrell, 1991a, 1991b, 1992a, 1992b, 1994a, 1997a; McCaffery, Ferrell, O’Neil-Page, 1992). A summary of survey findings from 1990 to 2006 has been published by the originators of the survey (McCaffery, Pasero, Ferrell, 2007). The results of the Andrew-Robert survey as presented in Table 2-1 are based on the responses of 615 registered nurses who attended pain programs throughout the United States. The survey was administered to registered nurses before the pain conference began. In viewing the nurses’ responses to pain assessment (question 1), it is apparent that not all nurses understood that the patient’s self-report of pain is the single most reliable indicator of pain. Both of these patients reported their postoperative pain as 8, but 14% of the nurses did not record 8 for the smiling patient and 5% did not record 8 for the grimacing patient. Those nurses who did not record 8 falsified the record and made it impossible for the next nurse to evaluate previous treatment for pain.

Table 2-1

Nurses’ Responses to the Survey: Assessment and Use of Analgesics*

*Data collected in 2006; N = 615.

As appears in Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. (2011). Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 21, St. Louis, Mosby. Data from McCaffery, M., Pasero, C., & Ferrell, B. (2007). Nurses’ decisions about opioid dose. Am J Nurs, 107, 35-39. McCaffery M, Pasero C, Ferrell B. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

The percentages of nurses who recorded what the patients said are high but there is no room for false entries in the chart. If these results were from a single institution, then one would have to say that up to 14% of the nurses were not recording what the patients said, and this is made more complex because we do not know who they are. Thus, all recordings of pain intensity would have to be viewed with some suspicion.

The Andrew-Robert survey is a quick and easy survey to use in small and large populations of nurses. The results of the survey help to generate discussion of common problems that arise in patient care. Another brief and more comprehensive survey of staff knowledge is titled Pain Knowledge and Attitude Survey and is available in Appendix A.

The survey findings illustrate what is sometimes seen in clinical practice—each person caring for a patient may have a different opinion about the intensity of a patient’s pain. Without a standard for assessing pain, chaos quickly ensues. For example, four different clinicians caring for the same patient may arrive at four different pain ratings, all of which are different from the patient’s own pain rating (and usually are underestimations of a patient’s pain). How do you resolve five different pain ratings so that intervention can be planned?

The need to establish the patient’s self-report as the standard becomes apparent. There appears to be no alternative. It is reassuring to realize that the validity and reliability of patients’ self-reports of pain are testified to in the numerous double-blind studies of analgesics, in which the patients’ pain ratings always determine the analgesic effect of the drugs being tested. Initial recommended doses of analgesics and equianalgesic charts have relied on the patient’s self-report for decades.

When a patient reports pain, the health care professional’s responsibility is to accept and respect the report and to proceed with appropriate assessment and treatment based upon the self-report. All reports of pain are taken seriously. When difficulties arise in accepting the patient’s report of pain, some of the strategies listed in Box 2-1 may be helpful.

Health Care Conditions that Influence Clinicians’ Judgments of Pain

Numerous factors influence clinicians’ tendencies to doubt patients’ reports of pain. This section discusses the effects of length of time caring for patients with pain, environmental cues that promote suspicion of patients’ pain reports, and the effects of the nature of one’s clinical practice.

Studies report conflicting results about the effects of length of time caring for patients with pain. As reported earlier, clinicians frequently underestimate patients’ pain ratings. This has been explained as being a process of habituation. Repeated exposure to patients’ pain seems to promote the development of insensitivity to pain (Kappesser, Williams, Prkachin, 2006). Yet other studies have not shown this (Everett, Patterson, Marvin, 1994; Hamers, van den Hout, Halfens, 1997). In a study of 50 registered nurses randomly selected from 2 general surgical units, two general medical units, and a combined intensive care unit/coronary care unit, participants completed an instrument that contained 60 vignettes describing a patient’s illness or injury (Dudley, Holm, 1984). Nurses were instructed to rate each patient on the degree of pain and psychologic distress. Nurses inferred significantly less pain than psychologic distress. Correlation analysis revealed a markedly weak and statistically insignificant correlation between years of practice and pain scores.

Other factors that may influence clinicians’ estimates of patients’ pain may be access to the patients’ self-reports and the atmosphere of suspicion surrounding particular patients. In one study, 60 physicians and nurses from the emergency department (ED) and 60 from the oncology setting watched videotapes of facial expressions of patients with shoulder pain undergoing range-of-motion exercises (Kappesser, Williams, Prkachin, 2006). Participants were divided into three groups and given different information: Group 1, videotape only; Group 2, the same videotape plus the patients’ reported pain intensity; and Group 3, the same videotape plus being told the patient pain reports and that some of the people were faking pain to obtain opioid drugs. All participants were asked to rate the patients’ pain, and participants in groups 2 and 3 were asked to state whether they had the impression that any of the patients had faked pain or hidden pain. Clinicians in all three groups underestimated patient pain intensity. The least discrepancy between clinicians’ and patients’ pain ratings occurred when the clinicians were given the patients’ self-reports but were not told that some patients were faking pain to obtain opioids.

The greatest discrepancy occurred when clinicians were given the patients’ pain reports but were told that patients might be faking pain to obtain opioids. This suggests that a clinical atmosphere of suspicion, such as sometimes occurs in trauma units or EDs, may cause an increase in clinicians’ doubting patients’ reports of pain. In all clinical areas clinicians need to be cognizant of the attitudes they convey when they discuss patient care with their colleagues. Managers and supervisors can be alert to stigmatizing labels and help staff to avoid them. For example, the term drug-seeking, which has no universally accepted definition, commonly conveys that a patient is addicted to opioids, abusing pain medicine, or manipulative (McCaffery, Grimm, Pasero, et al., 2005). In fact, the American Society for Pain Management Nurses (ASPMN; 2002) recommends that this term not be used because it creates bias and prejudice that subsequently have negative effects on pain management.

The nature of a particular clinical practice may influence clinician estimates of patient pain intensity. The effect of repeatedly inflicting pain on patients was studied by using brain scans to compare the responses of physicians who practice acupuncture with the responses of naïve participants while watching animated visual stimuli depicting body parts in both a nonpainful situation (being touched by a Q-tip) and a potentially painful situation (acupuncture [being pricked by needles]) (Cheng, Lin, Liu, et al., 2007). The acupuncturists rated these situations as being significantly less painful and unpleasant than did the naïve control participants.

In addition, the brain scans supported the notion that mechanisms are triggered in the areas of the brain that regulate emotions and cognitive control. The authors commented that without some regulatory mechanism, it is likely that clinicians would experience personal distress and anxiety that would interfere with their ability to perform. Acupuncturists know that they may be inflicting pain and seem to have learned throughout their training to inhibit the empathy-pain response.

Many other clinical practices, such as burn care and surgery, involve repeated infliction of pain. A study of burn care found that staff members who had spent more time working with burned patients believed débridement was less painful than did the staff members who had spent less time working with burned patients (Perry, Heidrich, 1982). To continue to manage pain effectively, such clinicians need to be aware of their tendencies to underestimate the painful impacts of what they do and to recognize that doing so may be an essential mechanism that allows them to continue to give care. Rather than be embarrassed or ashamed of this reaction, they can acknowledge it to themselves (and perhaps others) and try to compensate by obtaining and listening carefully to information from their patients.

Other examples are clinicians who perform venipunctures or bone marrow aspirations daily; they may become less sensitive to the amount of pain they are inflicting. Clinicians who work in a pain clinic several days a week may grow weary of and less sensitive to patients who continue to report pain despite their best efforts to relieve the pain. Again, to continue to practice effectively in such conditions it may be necessary to make a conscious personal inventory that honestly admits to having less empathy for patients as time goes by. Once this is acknowledged, the clinician can plan a systematic approach to obtaining information from the patient and ensure that it is acted upon.

Considerations When Doubts Arise

On occasion, accepting and acting on the patient’s report of pain are difficult. Because pain cannot be proved, health care professionals are vulnerable to being fooled by the patient who wishes to lie about pain. However, although accepting and responding to the report of pain will undoubtedly result in giving analgesics to some patients who do not have pain, doing so ensures that everyone who does have pain receives attentive responses. Health care professionals do not have the right to deprive a patient of appropriate assessment and treatment simply because they believe a patient is lying.

An important distinction exists between believing the patient’s report of pain and accepting the report. Following the recommendations of the clinical practice guidelines does not require that the clinician agree 100% with what the patient says. Clinicians are not required to believe a patient but are required to accept what a patient says, convey acceptance to the patient, and take the appropriate action. Clinicians are entitled to their personal doubts and opinions, but they cannot be allowed to interfere with appropriate patient care. Box 2-1 summarizes some strategies that can be used when the patient’s report of pain is not accepted.

Although accepting the patient’s report of pain occasionally results in being fooled, no stigma or blame should be attached to being duped. In any relationship, each party has certain responsibilities. Fault is assigned to the parties who fail to meet their responsibilities (Wesson, Smith, 1990). If the clinicians fulfills his or her responsibility to respond to all reports of pain with appropriate assessment and treatment, the clinician will be able to say, “Although I was probably fooled by some patients, I never failed to help those who did have pain. No one can find fault with my behavior or professional conduct.”

Furthermore, accepting the patient’s report of pain avoids an adversarial relationship. When a clinician conveys to a patient that a report of pain has not been accepted, it amounts to accusing the patient of lying. Understandably, this is upsetting and frightening to a patient who has asked the health care provider for help with pain. Much has been written in the literature about the distinction between suffering and pain. It is worth noting that in his analysis of suffering, Eric Cassell (1982) mentions that one source of suffering is physicians who do not validate a patient’s pain but rather ascribe it to psychologic causes or accuse the patient of faking. Clinicians ask patients to trust them. At some point clinicians must return the favor.

The term malingering may be encountered when a patient’s report of pain is doubted. Malingering can be defined as a conscious effort to produce symptoms such as pain for the purpose of deceiving or misrepresenting the facts, usually for monetary or other gains. Malingering seems to be suspected most commonly in patients with persistent pain, especially low back pain. A review of the literature prior to 1999 reveals 68 references to research of persistent pain malingering or disease simulation (Fishbain, Cutler, Rosomoff, et al., 1999). These studies conclude that malingering does occur, perhaps in 1.25% to 10.4% of patients, but these figures are not reliable because of the quality of the studies. This review concludes that there are no reliable methods of identifying malingering. The International Association for the Study of Pain notes that the process of identifying malingering is, in the final analysis, a legal, not a medical, process (Merskey, Bogduk, 1994).

On reflection, one might ask whether it is justifiable to be suspicious of all patients in an attempt to avoid being fooled by the few who lie. It is a burden to the clinician and an insult to the patient to wrestle with potential dishonesty at each encounter.

Pain Threshold: Uniform versus Variable

Pain threshold may be defined as the point at which an increasing intensity of stimuli is felt as painful. Several decades ago, preliminary research erroneously suggested that everyone perceives the same intensity of pain from the same stimuli (Hardy, Wolff, Goodell, 1943). This has been called the uniform pain threshold. However, further research failed to support the uniform pain threshold theory (Beecher, 1956). For half a century it has been known that comparable stimuli in different people do not produce the same intensities of pain. A uniform relationship does not exist between tissue damage and pain. A given type of tissue damage may produce more or less pain than one might expect. Not only does pain intensity vary among patients, but duration and other characteristics also vary.

In a small study, healthy volunteer subjects were asked to rate experimental pain consisting of nerve shocks. Given the same intensity of pain stimulus, various persons did not always give the same pain ratings, and the same intensity of pain stimulus given to the same person repeatedly did not always result in the same pain rating (Mader, Blank, Smithline, et al., 2003).

The idea that a particular patient “shouldn’t hurt that much” probably is based on the misconception that comparable stimuli produce comparable pain in different people. A more appropriate appraisal might be that a painful event hurts one patient more than it hurts another. Concluding that one patient is exaggerating the pain is judgmental and may result in a number of potentially harmful effects, such as failing to detect a complication or providing inadequate analgesia. When a patient reports pain that is considerably more than expected, it is always wise to reassess that patient.

Pain Tolerance: High versus Low

Pain tolerance is not the same as pain threshold; it may be defined as the duration or intensity of pain that a person is willing to endure. An example of high pain tolerance is the willingness to endure prolonged and severe pain without desiring relief, whereas low pain tolerance might be the desire for relief of brief, mild pain.

Pain tolerance varies from person to person and within the same person depending on numerous factors, such as past experiences with pain, coping skills, motivation to endure pain, and energy level. For example, a patient may be willing to endure intense pain during childbirth to minimize the infant’s exposure to medications but may be unwilling to endure mild episiotomy pain later if she is not breast-feeding.

Society places a high value on a high pain tolerance. The findings of one study suggest that nurses do not like patients who have severe pain or who are perceived as coping poorly with their pain (Salmon, Manyande, 1996). When patients were perceived as being unable to cope with pain, they were evaluated by the nurses as demanding and were unpopular with the staff.

Low pain tolerance seems to be regarded as a weakness, a character flaw, a lack of will power, or perhaps even self-indulgence. The implication appears to be that the patient should be stronger and muster the energy to cope with pain more successfully.

The routine use of the phrase complains of pain suggests a negative attitude toward patients with pain and may reflect a desire for patients to cope better and talk less about pain. Saying that patients “report pain” is much less evaluative. It is probably worthwhile making a conscious effort to avoid using the word complain. The reader may note that throughout this book, the authors never use the word complain in reference to patients’ reports of pain.

One cannot escape the fact that this society and many others value a stoic response to pain, which is probably very closely aligned with valuing a high pain tolerance. No doubt most readers share this value. However, health care providers must guard against requiring this of patients and certainly must avoid criticizing patients who are unable to meet this expectation. Patients have a right to determine their own pain tolerance.

Expecting a high pain tolerance may translate into deciding that patients ought to be able to tolerate particular painful experiences. There may be procedures; persistent pain conditions, such as arthritis or low back pain; surgeries; wound care; or a variety of other circumstances. In cases of procedural pain, it is not unusual for clinicians to voice their belief that providing sedation/analgesia is unnecessary for very short, but very painful procedures, believing that patients should be able to “tolerate” brief pain.

A common misconception is that increased experience with pain should teach a person to be more tolerant of it and better able to cope with it. However, repeated experience with pain often teaches a person how severe pain can become and how difficult it is to get pain relief. Thus, a person who has repeated experiences with pain may have higher levels of anxiety and lower pain tolerance. In one study of adults, previous surgeries appeared to result in greater pain intensity and emotion during later surgical experiences (Wells, 1989).

Identifying the patient’s pain tolerance is a critical part of providing pain relief. Setting pain rating and activity goals (discussed later in this section) is an effort to identify the level of pain a patient can endure without distress and still perform necessary activities easily.

Patients, as well as clinicians, value stoicism. When a patient is unable to meet his or her own expectations of being able to tolerate unavoidable pain or minimize behavioral expressions of pain, the clinician can at least minimize the psychologic trauma to the patient by conveying that the patient’s response to pain is fully acceptable. Simply saying, “This is tough. You’re doing well,” may help reduce the patient’s distress.

Behavioral and Physiologic Responses to Pain

Acute Pain Model versus Adaptation

The acute pain model says that if the patient has pain, visible signs of discomfort, behavioral or physiologic, will be present. Examples of behavior usually expected of patients with pain include grimacing, rigid body posture, limping, frowning, or crying. Physiologically, elevated vital signs are commonly expected. Clinicians and laymen alike usually fail to appreciate that both physiologic and behavioral adaptation occurs, leading to periods of minimal or no signs of pain. Absence of behavioral or physiologic signs of pain does not necessarily mean absence of pain.

The acute pain model is of limited value for assessing pain. When pain is sudden or severe, behavioral and physiologic indicators may be present for a brief time. However, very quickly the patient may make an effort to cease behaviors such as crying or moaning. Behavioral adaptation or suppression of pain behaviors may occur because the patient values the stoic response or simply becomes exhausted. Physiologic indicators such as increased blood pressure (BP) or heart rate may also disappear. In a healthy individual, the body seeks homeostasis or equilibrium, returning to the former physiologic state despite severe pain. Or a patient may have a medical condition that causes low BP, such as hypothyroidism or dehydration, which has a much greater impact on vital signs than pain has. In such patients, sudden, severe pain may elevate the vital signs only briefly and minimally.

The APS addresses the misconceptions about the acute pain model by stating the following:

• With regard to acute pain, the APS (2003) says, “Often but not always [italics ours], it is associated with objective physical signs of sympathetic branch autonomic nervous system activity, including tachycardia, hypertension. . . .” (p. 2).

• With regard to persistent cancer pain, the APS (2003) says, “The lack of objective signs may prompt the inexperienced clinician to wrongly conclude the patient does not appear to be in pain” (p. 3).

Responses Clinicians Expect of Patients with Pain

Nurses’ responses to the Andrew-Robert survey (see Table 2-1, p. 21) reveal that patients’ behavioral responses have significant effect on nurses’ pain assessments and treatment decisions (McCaffery, Pasero, Ferrell, 2007). The only difference between Andrew and Robert is their behavior—Andrew smiles and laughs with visitors, whereas Robert lies in bed and grimaces. This simple difference has a startling effect on nurses’ decisions about opioid doses.

Although the patients were exactly alike except for their behaviors, the nurses were more likely to increase the morphine dose for the grimacing patient. Both patients had received morphine, 2 mg IV, 2 hours before; half-hourly pain ratings had ranged from 6 to 8 out of 10 and were currently 8; and no clinically significant adverse effects such as sedation had occurred. The pain rating goal was 2. Nurses were given a choice of administering no morphine or 1 mg, 2 mg, or 3 mg IV. Morphine, 3 mg IV, was the correct choice for both patients because the previous dose of 2 mg was safe but ineffective. However, only 50.6% of the nurses would increase the dose for the smiling patient, whereas 64.3% would increase the dose for the grimacing patient. Both patients were undertreated, but at least 14% of the nurses knew that it was safe to increase the dose for the smiling patient, but they did not. Over the years since 1990, other similar vignette surveys conducted by these authors have shown similar findings, which show little improvement in nurses’ choices of opioid doses (McCaffery, Pasero, Ferrell, 2007).

The same discouraging results were found when the Andrew-Robert survey was adapted to reflect the needs of elderly patients in a long-term care facility (Katsma, Souza, 2000). The participants were 89 licensed nurses working in long-term care facilities. As in the original vignette, one patient was described as smiling and the other as grimacing. After receiving medication, hourly pain ratings were 6 to 8, and the patients showed no serious adverse effects. In response to the question about which analgesic dose they would now give, only 30% correctly selected a higher dose for the smiling patient, but 43% did so for the grimacing patient.

These same biases about behavior also exist in laypersons. The Andrew-Robert survey was revised to be appropriate for a nonnurse audience and was administered to 85 college students who were not enrolled as medical or nursing majors (McCaffery, Ferrell, 1996a). College students’ responses to assessment and relief of pain showed trends similar to those of practicing nurses. The smiling patient’s pain rating was accepted by 38% of the college students, whereas 55% accepted the grimacing patient’s report of pain.

Vital signs also influence nurses’ willingness to record a patient’s report of pain. A survey using the same format as the original Andrew-Robert survey was constructed; the only difference between the patients was their vital signs (McCaffery, Ferrell, 1992a, 1992b). One patient had low to normal vital signs, and the other patient had elevated vital signs. The responses of 166 nurses revealed that more nurses were willing to accept the report of severe pain from the patient with elevated vital signs than from the patient with low to normal vital signs.

As part of the Missoula Demonstration Project, a 15-year process to study end-of-life issues, surveys about pain knowledge and attitudes were sent to 942 nurses and produced 311 responses (Mayer, Torma, Byock, et al., 2001). The survey revealed that 93% of the nurses knew that vital signs were not reliable indicators of pain, but 75% said that vital signs moderately or greatly influenced their decisions to treat or not to treat pain.

In a small study designed to identify the criteria nurses use to assess postoperative pain, 10 nurses were interviewed about their pain assessments of 30 postoperative patients (Kim, Schwartz-Barcott, Tracy, et al., 2005). The strategy most frequently reported by the nurses relied on the patient’s appearance and drew on past experience of which physical signs to look for, such as facial expression, body movement, and heart rate. For example, nurses mentioned frowning or wincing as being indicative of pain and a patient’s being able to fall asleep as a sign of little or no pain. The researchers commented on the fact that the predominant strategy of looking for objective signs of pain was in marked contrast to current guidelines that emphasize the patient’s self-report of pain.

Expectations that certain behaviors indicate pain also influence the prescribing of analgesics. To identify factors that affect physicians’ decisions to prescribe opioids for persistent noncancer patients, the records of 191 patients referred to a pain center were examined to determine pain severity, physical findings, pain duration, age, gender, observed pain behaviors, reported functional limitations, and affective distress (Turk, Okifuji, 1997). Of all these variables, only observed pain behaviors were significantly related to receiving opioid prescriptions. In other words, patients who exhibited pain behaviors were most likely to receive opioids for pain relief. The extent of physical findings and the severity of the pain did not appear to influence the decision to prescribe opioids. Because opioids are prescribed for the purpose of pain relief, it would seem more logical to find that severity of pain determined prescription of opioids, but this was not the case.

Similar findings also were reported regarding patients with low back pain. Decisions about lumbar surgery were not made on the basis of physical pathologic conditions but rather on behaviors demonstrated by patients during their evaluations (Waddell, Main, Morris, et al., 1984). As summarized by Turk and Okifuji (1997), “physicians appear to believe that behavioral demonstrations of pain, such as limping and grimacing, indicate something important about the nature of the patient’s pain and the need for prescribing specific treatments such as surgery and opioids” (p. 334).

Patients’ Knowledge of Clinicians’ Expectations of Pain Behaviors

Interviews with patients who had used intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV PCA) for opioid administration after surgery revealed that a major reason for patients’ valuing PCA was related to the fact that PCA decreased the need to interact with the nursing staff regarding pain (Hall, Salmon, 1997; Taylor, Hall, Salmon, 1996a, 1996b). Not only did patients see PCA as being better than waiting for a nurse to administer opioids intramuscularly, they also believed it protected them from having to show distress to the nurses.

Apparently many patients with pain are aware of the behaviors expected of them, or they learn them quickly. Patients may learn from early childhood experiences with pain, television, the responses of their clinicians, and a variety of other sources how to behave to signal others that pain exists and that help is needed. It is a common observation that patients with pain change their behavior in the presence of clinicians and in other selected circumstances. Patients may appear to be calm and to read or have lively telephone conversations, but as soon as clinicians enter, patients may replace these activities with a solemn facial expression and may even grimace, moan, and restrict movement—just the behaviors clinicians want to see when patients report pain, but not necessarily the behavior patients prefer.

Consider what might happen if the patients in the Andrew-Robert survey were roommates. It would not take long for smiling Andrew to realize that grimacing Robert was receiving better pain relief, and the reason probably would be quite apparent to smiling Andrew. Andrew might take pride in looking energetic and happy in front of his visitors or may find that such distraction is very helpful as a coping mechanism. But if he wants better pain relief, he may decide to change that behavior, at least during the time clinicians are present. When clinicians see this change occur, they often regard patients as being manipulative, not realizing that it is the expectations that clinicians convey to patients that cause this behavior change.

Taking this hypothetical situation further, by succumbing to expectations of pain behavior to obtain relief, Andrew may begin to jeopardize his recovery. For example, both patients might be told to ambulate. Smiling Andrew may walk the hall until he begins to hurt and then go to the nurses’ station and ask for something for relief. The staff may feel that if Andrew can be this active, he could not hurt enough to require an analgesic. Grimacing Robert, on the other hand, may remain in bed grimacing rather than ambulating and may also ask for an analgesic. Robert may very well be more likely to receive the analgesic than Andrew. Andrew may then learn to stay in bed, prolonging his recovery time and increasing the risk of complications, but increasing his chances of receiving pain relief.

Comparable circumstances were observed in a study of cancer patients (Cleeland, Gonin, Hatfield, et al., 1994). The more active patients were more likely to receive inadequate pain management.

Because clinicians differ in how they expect patients to behave in response to pain, patients may have difficulty learning which behaviors will effectively convince which clinicians. An analysis of staff and patient behavior in an orthopedic unit revealed that the staff assessed pain by observing patients’ behaviors and that their expectations about how patients should express their pain varied within and between shifts (Wiener, 1975). Some, but not all, patients were adept at reading the explicit and implicit cues given by staff and changed their behaviors accordingly. Patients sometimes felt forced to use tactics that they believed were unacceptable but were expected by the staff and were necessary to obtain pain relief.

Expecting patients to behave in certain ways to verify their pain becomes more confusing when clinicians are especially particular about the intensity or type of behavior that a patient should display. Sometimes clinicians say that a patient does not appear to be in pain, but when a patient exhibits pain behavior, clinicians may say that a patient is making too much fuss about the pain.

Correction of the Misconceptions Concerning the Acute Pain Model

One of the most interesting aspects of the misconception that the patient’s behavioral response is more reliable than the patient’s self-report of pain is that it is totally illogical. Virtually every human being has had the personal experience of trying to hide pain and to function in spite of it, smiling when appropriate and even deliberately using humor as distraction. One of the oldest maxims in health care is that laughter is the best medicine. Why couldn’t the nurses and college students responding to the Andrew-Robert survey use this folk wisdom and their own personal experiences with pain to realize that patients with severe pain most certainly may smile and laugh? Nurses are probably the largest group of clinician advocates for nondrug pain relief measures, of which distraction and laughter are highly ranked. And no research has ever even suggested that smiling and joking are incompatible with feeling pain. Why clinicians seem to have such difficulty accepting and acting on reports of pain from smiling and active patients remains a mystery, at least to these authors.

A substantial amount of research refutes the value of the acute pain model, showing that neither behavioral indicators nor physiologic responses are dependably related to the intensity of a patient’s pain. Physiologic indicators appear to be even less valuable than a patient’s behavioral responses to pain.

Most nurses seem to have been taught to use elevated vital signs to assess or verify the presence of pain, especially severe pain. However, in literature reviews, investigators found very little research that supported using physiologic manifestations as specific indicators of pain (Herr, Coyne, Key, et al., 2006; van Cleve, Johnson, Pothier, 1996). In a study of 1063 patients admitted to the ED with conditions that could be verified to be painful, such as fractures and nephrolithiasis, no clinically significant associations were identified between pain scores self-reported on a scale of 0 to 10 and heart rate, BP, or respiratory rate (Marco, Plewa, Buderer, et al., 2006). In a study published in French, investigators found that absence of increased vital signs does not mean absence of pain (reported in Gelinas, Johnston, 2007).

Critical care nurses usually consider vital signs to be relevant indicators of pain, possibly because the signs are readily available, and it is often difficult to obtain pain reports from critically ill patients, whose behavioral responses may be compromised and who may be unconscious, intubated, or otherwise unable to communicate. In a study involving 30 conscious patients in an intensive care unit, no significant relationship was found between physiologic indicators and patients’ self-reports of pain, reinforcing the fact that physiologic indicators should not be considered primary indicators for pain assessment (Gelinas, Johnston, 2007). In other words, physiologic indicators were not related to patients’ reports of pain.

In another study of 755 patients, primarily in intensive care units, physiologic responses were monitored while the patients were undergoing tracheal suctioning (Arroyo-Novoa, Figueroa-Ramos, Puntillo, et al., 2007). Statistically significantly higher increases were noted in heart rate and systolic and diastolic BP, but these changes were not clinically significant. The authors suggest that methods of measuring these physiologic parameters may not be sensitive enough to capture the response to acute pain. For further discussion of the limited usefulness of physiologic measures in assessing pain, see the discussion of patients who are critically ill in Chapter 4, pp. 143-147.

The usefulness of physiologic measures of pain is further compromised by the presence of dementia in older adults. In a small study of adults 65 years old and older, 50 of whom were cognitively intact and 44 of whom had varying degrees of dementia, heart rate and other physiologic responses were monitored before and during venipuncture (Porter, Malhotra, Wolf, et al., 1996). Increasing severity of dementia was associated with the blunting of physiologic responses as measured by diminished heart rate increase in the preparatory phase and during venipuncture.

Thus, little research supports vital signs as being relevant indicators of pain, although they can be used as indicators of the need for further assessment of pain. A position statement by the ASPMN regarding assessment of pain in nonverbal patients (available at http://www.aspmn.org/Organization/documents/NonverbalJournalFINAL.pdf) suggests that physiologic indicators should not be used alone to assess pain but should be considered cues for further assessment of the possibility of pain (Herr, Coyne, Key, et al., 2006).

Considerable research demonstrates that the behavioral expressions of pain that clinicians expect to see in patients are often absent. In the late 1970s, investigators interviewed 102 adult patients with various types of pain, acute and persistent (Jacox, 1979). Many patients did not report pain and made strong efforts to conceal it. When the patients were asked whether they discussed pain with others, 70% said no or were ambivalent. When they were asked how they responded to pain, 66% said they tried to remain calm and not show pain. More than a decade later a similar finding was reported in a study of 45 patients with pain related to lung cancer (Wilkie, Keefe, 1991). Of the patients, 42% revealed that they coped with pain by trying not to let others know about it (Wilkie, Keefe, 1991).

Some researchers have attempted to use facial movements as a method of studying malingering. A review of the literature found that the results of these studies were inconsistent and concluded that it is unclear whether facial expressions of pain can be used as a reliable method for identifying malingering (Fishbain, Cutler, Rosomoff, et al., 1999). A few years after this literature review, facial expressions were studied in 40 patients with low back pain who were videotaped during rest and painful straight-leg raises (Hill, Craig, 2002). During painful movement they were asked to express their pain genuinely or to pretend that it did not hurt. Without moving, they were asked to fake pain. Although distinctions could be made between faked and genuine painful facial expressions, this research confirmed the difficulty of discriminating between them.

Patients with pain may deliberately engage in certain behaviors that are incompatible with those of the acute pain model but are helpful in coping with pain. In a study of 13 patients with pain related to advanced cancer, the patients reported that behaviors they used to control their pain included watching television (9 patients) or chatting with family and friends (Wilkie, Lovejoy, Dodd, et al., 1988). A questionnaire survey of 53 patients with persistent cancer pain asked them to identify and rate the effectiveness of the self-initiated, noninvasive pain control measures they used to cope with their pain (Fritz, 1988). Patients rated laughing as being the most effective.

Recently, researchers have identified that patients actually smile during painful situations, yet they did not find one tool for behavioral observation to assess pain that included smiling (Kunz, Prkachin, Lautenbacher, 2009). The facial expression of pain has been studied in both experimental and clinical research, and facial expression is often a part of behavioral observation tools to assess pain in both children and adults who cannot self-report. When these researchers viewed several videotapes of patients undergoing painful stimulation, one of the most unexpected findings in response to pain was the oblique raising of the lip that results in a smile. Their research revealed that the percentage of patients who smile at least once during painful stimulation ranges from 22% to 57%. A satisfactory explanation for this requires more research, but clinicians should not discount pain just because the patient smiles. Among other things, the smile could represent embarrassment over other behavioral responses to pain, an attempt to mask feelings of pain, or a willingness to endure the pain.

Sleep may be mistakenly equated with lack of pain, but even patients with severe pain may sleep. Some patients use sleep to help control their pain (Wilkie, Lovejoy, Dodd, et al., 1988). In one study, 100 patients were interviewed about the experiences of pain and sleep following abdominal surgery (Closs, 1992). Pain was the most common cause of sleep disturbance at night, demonstrating that pain occurs during sleep. Analgesics helped more patients get back to sleep than any other intervention. Also, about half of the patients felt that pain was worse at night.

Further, an appreciation of the fact that sleeping patients may have pain is demonstrated in analgesic research. When the effectiveness of analgesics is studied, trained observers ask patients to rate their pain at specific intervals, such as every hour, after the administration of the analgesic. When the observer finds the patient asleep at the time a pain rating is required, the observer awakens the patient to obtain a pain rating (Forbes, 1991).

This information does not necessarily indicate that in clinical practice sleeping patients should always be awakened to assess pain. If a patient has been given an analgesic and assessment of pain ratings afterward has shown that the analgesic has been effective, when the patient is given further doses, there usually is no need to awaken the patient to assess pain rating following a dose. Pain assessments can be made when the patient awakens. However, it may be wise to awaken the patient for the next analgesic dose if the analgesic lasts only 4 hours and the patient has continuous pain. This option can be discussed with the patient, explaining that if he or she is allowed to sleep beyond 4 hours, the pain may return to awaken him or her. If this happens, pain control is jeopardized. The patient must notify the nurse or obtain the analgesic on his or her own, take the analgesic, and then wait for it to be effective. In this scenario, a patient’s sleep is interrupted for longer than it would have been had the patient been awakened at 4 hours and given an analgesic before pain returned. Once this is explained to a patient, he or she may opt to be awakened or to wait to be awakened by pain. If the latter is chosen, a patient should be cautioned to notify the nurse immediately so the analgesic can be given. (If a patient’s sedation levels needs to be assessed, then it may be wise to awaken the patient. See the discussion of sedation levels on pp. 510-511.)

Very little research has been done to evaluate pain control using around-the-clock (ATC) dosing of analgesics versus administering them as needed, and the results are often inconclusive. However, one small study compared these two types of dosing schedules in 35 patients following abdominal surgery (De Conno, Ripamonti, Gamba, et al., 1989). Patients who received ATC analgesia had significantly better pain control, slept longer, and spent more time out of bed rather than lying down over the first postoperative week. Another study of medical inpatients compared ATC dosing of opioids to a control group and found that patients with ATC dosing reported lower pain intensity ratings than those reported by the control group yet did not take higher doses than the control group (Paice, Noskin, Vanagunas, et al., 2005).

Sedation is erroneously equated with analgesia. However, in a study of sedation and pain relief in the postanesthesia care unit, researchers found that opioid-induced sedation did not ensure adequate self-reported pain relief (Lentschener, Tostivint, White, et al., 2007). About half of the 26 patients who experienced opioid-induced sedation had persistently high pain scores in the postanesthesia care unit and during the initial 24-hour postoperative period. Further, morphine-induced sedation did not suppress the patients’ memories of early postoperative pain. Still another study confirmed that opioid-induced sedation could not arbitrarily be equated with analgesia (Paqueron, Lumbroso, Mergoni, et al., 2002). Of patients receiving intravenous morphine in whom morphine was discontinued because of sedation, 25% still had pain levels on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) above 50. (In patients receiving morphine whose pain relief is unacceptable, a multimodal approach to analgesia should be considered; see pp. 9-10.)

Many sedating drugs, such as benzodiazepines and phenothiazines, are given to patients who are experiencing pain, but most of them provide no analgesia, and the resulting sedation may limit the amount of opioid that can be given safely to a patient in pain. Except for pain related to muscle spasm, benzodiazapines do not relieve pain. Further, available phenothiazines neither relieve pain nor potentiate opioid analgesia (APS, 2003).

When a patient’s report of pain is not accepted and acted on, an effective strategy is to ask, “Why is it so difficult to believe this patient has pain?” When the problem revolves around expecting the acute-pain model to exist, the answer is likely to be “He doesn’t look like he’s in pain.” When you find yourself thinking this or hearing someone say it, try asking, “How would this person have to act for us to believe he has pain?” A clinician might answer that a patient in that much pain would grimace or be less active. Unfortunately, expecting a patient to “act like he is in pain” may lead to those behaviors and contribute to manipulative behavior and physical harm such as disability or complications resulting from decreased function.

Causes of Pain

When a patient reports pain and the cause clearly is established, clinicians are almost always more willing to treat the pain than when the cause of pain is in doubt. Surveys of nurses’ responses to hypothetical patients who report pain show that nurses tend to assume less intense pain when no physical pathologic condition is present (Halfens, Evers, Abu-Saad, 1990; Taylor, Skelton, Butcher, 1984) and when pain is persistent rather than acute (Burgess, 1980; Taylor, Skelton, Butcher, 1984). Also, nurses take fewer actions to relieve pain in patients with persistent pain (Burgess, 1980).

Lack of Physical Evidence of Pain

A previously suggested strategy for addressing clinicians’ reluctance to accept a patient’s report of pain is also useful here. Once again, try asking, “Why is it so difficult to believe this patient has pain?” If lack of a known physical cause is the reason, the answer is likely to be “There’s no reason for this patient to hurt.” A more accurate and appropriately humble response would be that we are as yet unable to establish the cause of the pain (Teasell, Merskey, 1997).

Statements that may help us reconsider our misconceptions include a reminder that the study of pain is a new and inexact science and that it would be foolish of us to think that we will be able to determine the causes of all the pains that patients report. It also may be helpful to articulate the underlying thought process, which is “We seem to be thinking that if there is pain, there is a cause. If there is a cause, we can find it. If we cannot find the cause, there is no pain.” Once it has been stated, we begin to recognize the absurdity of this idea.

Available assessment tools are not infallible and do not exhaust all possible means for determining the causes of pain. This has been especially true of chronic noncancer pain. In a study of 60 patients with persistent pain who had been referred to a diagnostic center, the overall rate of inaccurate or incomplete diagnosis at referral was 66.7% (Hendler, Kozikowski, 1993). In particular, neuropathic pain, which is often severe burning or shooting pain, tends to be underdiagnosed. It is not detectable by ordinary diagnostic tests because nerves, not muscles or other somatic structures, are involved.

Sometimes the physical cause of pain is known, but the pain is more intense or lasts longer than expected. In the 1980s (when hospital stays were longer than they are now), a study examined the belief that postoperative pain subsides rapidly over the first 3 days and is negligible by the fourth day. Research did not support this. Of 88 patients on a general surgical unit, 31% had pain that persisted beyond day 4, often related to being older or to complications such as infection (Melzack, Abbott, Zackon, et al., 1987). These patients typically received inadequate pain control because less effective analgesics were prescribed. Probably the staff believed there was no reason for these patients to hurt that much or for that long.

Clearly, the causes of pain cannot always be determined. This does not mean that the pain is absent or that clinicians are entitled to ignore a patient’s report of pain. Pain is subjective, and it seems rather easy to engage in faulty reasoning about it. An analogy that may clarify our responsibility to such patients is our response to patients with objective symptoms that have unknown causes. For example, if a patient vomits, we may not know why it has occurred, but because it is objective (an undeniable symptom), we treat it anyway. The cause of the vomiting is sought, but meanwhile treatment, such as antiemetics, is provided. Pain deserves the same respect as objective symptoms.

Belief that Noncancer Pain Is not as Painful as Cancer Pain

When persistent pain is not associated with a terminal illness, especially when the cause of the pain is unclear, that pain seems to be regarded as being more suspicious, less painful, or less in need of relief. Doubting the trustworthiness of the patient with persistent noncancer pain is thought by some to be at the heart of most treatment problems that arise with these patients (Richeimer, Case, 2004). For example, the patient’s motive for seeking care may be under suspicion. The cause of pain may not be identifiable or obvious, and the clinician may be suspicious that a patients is seeking opioids or disability compensation (Victor, Richeimer, 2005). Negative attitudes toward patients with noncancer low back pain have been recognized for many years (Burgess, 1980; Wiener, 1975).

Even when the causes of pain are known, non-life-threatening pain is less likely to be treated than is pain associated with terminal illnesses. In one study of physicians treating patients with cancer, inadequate pain management was more likely when pain was not attributed to cancer (Cleeland, Gonin, Hatfield, et al., 1994). A mail survey responded to by 368 physicians in Michigan asked them to identify their treatment goals for acute pain, cancer pain, pain due to terminal illness, and persistent noncancer pain (Green, Wheeler, Marchant, et al., 2001). Although their goals for pain relief for terminally ill patients and patients with cancer pain were similar, the goals were significantly lower for patients with persistent noncancer pain.

Surveys of laypeople also reveal differing attitudes toward various types of pain. A telephone survey of 1000 Americans asked whether high doses of analgesics should be prescribed for any of these three conditions: severe persistent pain, cancer pain, and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (The Mayday Fund, 1998). Approximately 80% supported high doses for cancer pain, approximately 70% supported high doses for severe persistent pain, but only about 50% supported high doses for RA. Perhaps both the public and clinicians tend to believe that some types of pain should be tolerated or are not very painful. In any case, the study reflects the tendency to provide less aggressive analgesia for one type of noncancer pain.

However, non-life-threatening conditions can result in very intense and prolonged pain. In a survey of 204 people with persistent noncancer pain, respondents revealed that their average length of time in pain was 9.5 years, with a range of 6 months to 74 years (Hitchcock, Ferrell, McCaffery, 1994). They were in pain an average of 80% of the time. For 30% the usual intensity of pain was severe, with a rating of 4 to 5 out of 5.

A common temporal classification of pain types is acute, cancer, and nonmalignant. Turk (2002) proposes that the mechanisms underlying cancer pain and nonmalignant pain are no different and that it makes no sense to discriminate between cancer pain and nonmalignant pain. He says that to do so results in paying insufficient attention to knowledge gained about cancer pain, and he suggests that greater effort be made to classify and treat pain according to the underlying mechanisms causing that pain as opposed to basing all treatment of persistent pain on whether the pain is caused by cancer. As a consequence, both cancer pain and persistent nonmalignant pain are now more often grouped together and referred to as persistent or prolonged pain.

Treating noncancer pain in the same way as cancer pain does raise legitimate concerns about the prolonged administration of medications. Certainly the chronic use of opioids remains controversial to some extent because of questions about the occurrence of addictive disease, hyperalgesia, hormonal changes, and other outcomes. (See Addiction on pp. 32-42 and Opioid Analgesics in Section IV for discussions of these conditions.) Prolonged use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs is of even greater concern than the use of opioids because of the possibility of life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding or adverse cardiovascular events. (See Nonopioid Analgesics in Section III for a discussion of this subject.) Thus, long-term treatment by pharmacologic measures poses many challenges but cannot be ignored as a possible source of relief for persistent pain.

Implication that Anxiety or Depression Is the Cause

In a previously described study, 50 registered nurses completed an instrument that contained 60 vignettes describing patients’ illnesses or injuries (Dudley, Holm, 1984). Nurses were instructed to rate the patients on the degree of their pain and psychologic distress. Nurses inferred significantly less pain than psychologic distress, whereas in actuality, patients were experiencing both. Unfortunately, patients are then likely to receive psychologic support but not the analgesic needed to decrease pain.

When the physical cause of pain is unknown or seems insufficient to account for the severity of pain a patient reports, clinicians may attribute the pain to the patient’s emotional state and cease treating the pain. A comment that suggests this is so is, “The patient is just upset.” It is interesting that in a survey of the public’s attitude toward stress and pain, 95% of respondents agreed with the statement that stress increases pain (The Mayday Fund, 1998). Actually, evidence that stress increases pain is limited.

An erroneous and simplistic view promoted around the middle of the 20th century was that physical and psychologic causes of pain were mutually exclusive; that is, that pain is caused by either organic or psychologic factors (IASP ad hoc Subcommittee for Psychology Curriculum, 1997). Gagliese and Katz (2000) state that Melzack’s gate control theory argues against the simplistic thinking that leads to categorizing pain as being either organic or psychogenic. The authors believe that medically unexplained pain is not caused by psychopathology and that thinking that separates mind and body should be abandoned. Trying to differentiate between psychogenic and physical pain is usually fruitless. Pain caused solely by psychologic factors is rare, as is pain caused solely by physical causes. Most pain is a combination of physical and psychologic factors and is best treated as such. The subsequent discussion concerns the as yet unclear relationships between pain and anxiety or depression.

The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience which we primarily associate with tissue damage or describe in terms of such damage, or both” (Mersky, Bogduk, 1994, p. 210). By definition, pain is always unpleasant and always subjective, so pain is always an emotional experience. But what are the relationships between pain and various emotions? A common assumption is that anxiety or depression makes pain worse, but this is not always true.

One review of the literature found that research findings are conflicting and inconsistent regarding the relationship between depression and pain and between anxiety and pain (Zimmerman, Story, Gaston-Johansson, et al., 1996). Another literature review pointed out that a high proportion of patients with persistent pain have some kind of depressive syndrome; however, the depression may precede, follow, or develop concomitantly with the persistent pain (Dellemijn, Fields, 1994).

For the purposes of discussion, it is helpful to consider how anxiety and depression affect coping with pain as well as how they affect the intensity of pain. Although certain levels of anxiety are actually helpful in mobilizing appropriate coping mechanisms, high levels of anxiety and possibly any level of depression may adversely affect a patient’s ability to cope with pain.

Roughly 50% of patients with persistent pain also have depression or an anxiety disorder (Weisberg, Boatwright, 2007). It has been relatively well established that persistent pain is often the precipitating factor for mood disorders and for anxiety disorders, yet the interaction between persistent pain and such disorders is less well understood (Weisberg, Boatwright, 2007). Depression may adversely affect coping by causing a patient to be less motivated to engage in activities and try new ideas for rehabilitation or treatment.

Pain-related anxiety or pain-related fear may also immobilize patients. Such fear or anxiety may cause hypervigilence and avoidance of activities that a patient fears may cause pain. This concern with avoiding painful activities may result in a patient’s having difficulty freeing attention to focus on nonpainful activities (Vlaeyen, Crombez, 2007). One approach to helping these patients to improve their functioning has been exercise and graded activity programs in which patients gradually increase their physical activities. Another approach is verbal reassurance, but this can have an opposite effect unless done carefully. Simply telling patients not to worry, that they do not have a severe disease, or that their tests have shown negative results may increase their distress. Fearful patients may become more puzzled because they still hurt and no explanations have been offered. Such patients need credible explanations of why they hurt (Vlaeyen, Crombez, 2007).

How anxiety and depression influence pain intensity is an even more complicated issue. Anxiety certainly is associated with many types of pain, and depression is common in patients with persistent pain. However, the cause-and-effect relationship is unclear. Does anxiety cause pain or is it the result of pain? Is depression the cause or the result of pain? Some studies show a relationship between depression and pain, and some do not. Likewise, anxiety has been correlated with increased pain in some studies but not in others. Anxiety unrelated to pain may actually decrease pain, possibly because the anxiety increases the production of endorphins (Janssen, Arntz, 1996).

In a study of 120 patients with cancer pain, no difference was found in pain intensity measures or functional status between the depressed patients and those who were not depressed (Grossman, Sheidler, Sweeden, et al., 1991). In other words, the depression associated with pain did not alter a patient’s report of the intensity of the pain. In another study of patients who had cancer, the presence of depression, hostility, and anxiety did not correlate with the effectiveness of attempts at pain relief (Cleeland, 1984). Cleeland warns us that when patients do not respond to analgesics, clinicians should be wary of blaming this result on the patients’ depression rather than on inappropriate analgesic therapy.

The relationship between preoperative-state and postoperative-state anxiety and pain magnitude has been addressed by a few studies. (State anxiety is situational, whereas trait anxiety is a general level of anxiety.) A study of 96 patients after coronary artery bypass graft surgery examined the relationship between postoperative-state anxiety and the perception of postoperative pain. The results showed that even in the range of low to moderate state anxiety, higher anxiety postoperatively was associated with higher pain intensities (Nelson, Zimmerman, Barnason, et al., 1998). The correlations between postoperative-state anxiety and postoperative pain ranged from low to moderate but were nevertheless statistically significant. However, again, the direction of causality has not been established. In other words, although increased pain and increased anxiety may occur together, it is not always clear whether the anxiety causes the pain or the pain causes the anxiety.

An exploratory study of 24 patients undergoing varicose vein surgery examined the relationship between pain ratings and preoperative state anxiety (Terry, Niven, Brodie, et al., 2007). Pre- and postoperative-state anxiety and pain ratings in the postoperative period were significantly positively correlated. However, the actual postoperative pain ratings were relatively low, with a mean VAS rating of 28.1 mm on a 100-mm linear scale. Nevertheless, the authors point out that the findings show the need to decrease anxiety in the clinical setting whenever possible. Suggestions about how to reduce anxiety were not included.

Another small study of women undergoing termination of pregnancy investigated the links between preoperative-state and trait anxiety and pain magnitude (Pud, Amit, 2005). About 1 hour before the procedure the women completed Spielberger’s State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Postoperatively, patients were asked to mark a 100-mm VAS at 50, 30, and 60 minutes. State anxiety was able to predict pain magnitude at 15 minutes, and trait anxiety predicted pain magnitude at 30 minutes. The authors explained this finding on the basis that state anxiety was expected to disappear when patients felt the immediate threat had been removed, whereas patients with trait anxiety needed more time to relax. The authors suggest that patients with high anxiety may require additional information relevant to the impending pain along with effective pain-relief protocols.

The belief that anxiety causes pain is reflected in the common practice of combining anxiolytics and opioids. Based on a literature review, Pud and Amit (2005) found that two methods, information giving and relaxation techniques, were beneficial in relieving anxiety and pain but that the use of pharmacologic approaches to anxiety such as benzodiazepines was more controversial. In one study, lorazepam (Ativan) preoperatively did not significantly relieve pain (Wiebe, Podhradsky, Dijak, 2003). The findings in a study of postoperative patients who had access to IV PCA morphine and midazolam (Versed) separately revealed that use of midazolam did not influence pain scores or amount of PCA morphine used (Egan, Ready, Nessly, et al., 1992). In another study of postoperative pain, the administration of diazepam (Valium) preoperatively was shown to have an ongoing antianalgesic effect on morphine analgesia (Gear, Miaskowski, Heller, et al., 1997). In a double-blind study, combinations of various doses of midazolam and meperidine were administered to 150 patients with postoperative pain and, once again, midazolam did not significantly enhance the analgesic effect of the opioid (Miller, Eisenkraft, Cohen, et al., 1986).

No doubt exists that pain results in considerable distress for many patients, causing anxiety, depression, and hostility and interfering with all domains of quality of life (e.g., Ferrell, Grant, Funk, et al., 1997; Zimmerman, Story, Gaston-Johansson, et al., 1996). Until the relationships among pain and anxiety, depression, and other emotional states are clarified, the most practical initial approach to patients who are both in pain and anxious or depressed probably is to assume that pain causes these emotional responses rather than to assume that the emotional responses cause or intensify pain. Anxiety and depression appear to be normal responses to pain. When a patient is both in pain and anxious, initial intervention probably should be aimed at reducing the pain. The APS (2003) states, “In anxious patients with pain, opioid titration should precede treatment with benzodiazepines” (p. 46). Pain relief may well reduce the anxiety and minimize the need for a benzodiazepine. Likewise, for patients who are in pain and depressed, the most logical initial approach probably is to relieve the pain, which may then reduce the depression. If anxiety or depression persists following pain relief, other interventions, such as behavioral and pharmacologic approaches, are indicated.

Addiction

Seeking Drugs versus Seeking Pain Relief

Perhaps the most common reason for not accepting and acting on a patient’s report of pain is the belief that the patient is or will become addicted to an opioid. A previously suggested strategy for addressing clinicians’ reluctance to accept a patient’s report of pain is to ask, “Why is it so difficult to believe this patient has pain?” Suspicion of addiction is often the answer. Clinicians may say, “The patient is drug seeking,” “He just wants drugs,” or “He’s getting addicted.” At present, in many clinical settings, the term drug seeking, though poorly defined, is used to mean addiction to opioids, abuse of opioids, or manipulative behavior (McCaffery, Grimm, Pasero, et al., 2005). Although patients seek drugs for many legitimate purposes, such as treating an infection, diabetes, or heart disease, somehow the term drug seeking has become associated with seeking opioids for reasons clinicians believe are inappropriate.

Questions, discussed later, that may be helpful in clarifying the confusion that surrounds beliefs about addiction are:

Definitions Related to Addiction

Tolerance to opioids and physical dependence on opioids are not the same as addiction to opioids, but these three terms are often confused. Following are the definitions proposed by the American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM), the APS, and the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) (AAPM, APS, ASAM, 2001; APS, 2003):

• Physical dependence is a normal response that occurs with repeated administration of an opioid for more than 2 weeks and cannot be equated with addictive disease. It is a state of adaptation that is manifested by the occurrence of withdrawal symptoms when the opioid is suddenly stopped or rapidly reduced or an antagonist such as naloxone (Narcan) is given. When the opioid is no longer needed for pain relief, withdrawal symptoms usually are easily suppressed by the natural, gradual reduction of the opioid as pain decreases or by gradual, systematic reduction, referred to as tapering (not detoxification, which is a term used when opioids are decreased in a person with addictive disease).

• Tolerance is also a normal response that occurs with regular administration of an opioid and consists of a decrease in one or more effects of the opioid (e.g., decreased analgesia, decreased sedation or decreased respiratory depression). It cannot be equated with addictive disease. Tolerance to analgesia usually occurs in the first few days to 2 weeks of opioid therapy but is uncommon after that. It may be treated with increases in dose. However, disease progression, not tolerance to analgesia, appears to be the reason for most dose escalations. Stable pain usually results in stable doses. Fortunately, tolerance to opioid-induced respiratory depression, sedation, and other adverse effects (except for constipation) occur to some degree within a few days of starting regular doses of opioids. So tolerance poses very few clinical problems.

• Opioid addiction or addictive disease is a chronic neurologic and biologic disease. Its development and manifestations are influenced by genetic, psychosocial, and environmental factors. No single cause of addiction, such as taking an opioid for pain relief, has been found. It is characterized by behaviors that include one or more of the following: impaired control of drug use, compulsive use, continued use despite harm, and craving. The diagnosis of addictive disease is not based on a single event but is based on a pattern of behavior that is observed over time. Most pain specialists and addiction specialists agree that in patients treated with prolonged opioid therapy, addictive disease is not a predictable drug effect and does not usually occur. The actual risk is not known. The disease of addiction is complex and multicausal and occurs over time, certainly not as a result of one hospital experience.

Each of these conditions—physical dependence, tolerance, and addictive disease—is a separate entity requiring different treatment. One may occur alone, any two together, or all three together. Physical dependence and tolerance are a result of repeated administration of the opioid and should be expected if regular daily doses of opioids are taken for 2 to 4 weeks or longer. Addiction, however, is a rare consequence of using opioids for pain relief.

Pseudoaddiction, as the name implies, is a mistaken diagnosis of addictive disease. The term was first used and the behaviors described by Weissman and Haddox (1989). Patients with undertreated pain may manifest behaviors very similar to those typical of addictive disease, such as escalating demands for more or different medications, repeated requests for opioids before the prescribed interval between doses has elapsed, illicit drug use (such as obtaining opioids from others), and deception (APS, 2003). Pseudoaddiction can be distinguished from true addictive disease in that the behaviors resolve when pain is effectively treated.

Likelihood of Occurrence of Addictive Disease

To address concerns about the likelihood of the occurrence of addictive disease in patients who receive opioids for pain relief, two separate questions must be addressed:

• What is the likelihood that a patient will develop addictive disease as the result of taking opioids for pain relief?

• What is the likelihood that a patient taking opioids for pain relief already has addictive disease?

Inconsistency in Defining Terms Related to Problematic Opioid-Taking Behavior

To attempt to answer either question, one must admit that it is extremely difficult to design studies about addiction and that the findings of studies done to date are certainly open to question. One of the major difficulties in interpreting and comparing these studies is inconsistency in the definitions and criteria used to determine addictive disease, opioid abuse, and other problematic drug-taking behaviors (a term usually used to cover all uses of opioids that are of concern). Many of the studies used the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; APA, 1994) criteria for substance dependence, a term usually equated with addictive disease. This definition of addiction, however, is not the same as that proposed by AAPM, the APS, and the ASAM (2001), cited above. The term substance abuse, also used in these studies and defined by DSM-IV, is not the same as substance dependence or addictive disease. Substance abuse as it applies to opioids is generally reserved for behaviors somewhat similar to those of addictive disease but not as severe. The behaviors are destructive to the life of the individual and persist over time. They may include use of opioids in situations in which drug use is physically hazardous such as driving an automobile, or legal problems may occur such as forging prescriptions. The term substance misuse as it applies to opioids is generally reserved for behaviors less severe than substance abuse, such as calling for early refills, not taking the opioid as prescribed, giving the medication to someone else, or unauthorized dose escalation.

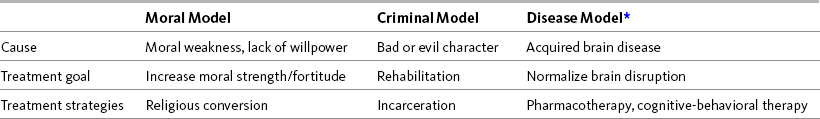

Since the DSM-IV (1994) does not use the term addictive disease but rather the term substance dependence, which incorporates symptoms of addiction, this creates confusion. DSM-IV (1994) incorporates symptoms of addiction. To minimize confusion, an effort has been made to resolve this (Heit, Gourlay, 2009). Pain specialists argue that dependence is too misleading because it gets confused with physical dependence, which is expected, and physical dependence differs from DSM-IV’s use of the term substance dependence. As the DSM-IV manual is being updated, pain specialists are encouraging the American Psychiatric Association DSM-5 committee to restore the term addiction (Heit, Gourlay, 2009). One of the committee’s objections to this is that the word addiction is too stigmatizing. However, in recognition of the need to clarify terminology and establish addiction as a disease (Heit, Gourlay, 2009), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) may be changed to the National Institute on Diseases of Addiction. Another example of the term addiction being more commonly used by professionals is the creation of the ASAM. Use of the word addiction promotes understanding that it is a disease and should be treated as one. As this book goes to print, the decision of the DSM-5 committee is not known.

Despite this confusion about the meaning of terms used in research when referring to addictive disease, we review some of the studies to identify trends in the currently available information.

Development of Addictive Disease in Patients Who Are Taking Opioids

In response to the first question, the findings of several studies have shown that addiction as a result of using opioids for pain relief occurs in less than 1% of patients. Possibly the most interesting research in this area was conducted in the 1970s during a time when heroin was widely used as an analgesic in England. Heroin was used for a variety of types of pain, such as postoperative pain and pain associated with terminal illness. In fact, the popular “magic” mixture called Brompton’s Cocktail, which originated in England, contained heroin, cocaine, gin, and honey. It was modified and used in the United States in the 1970s for pain relief in terminal illness. Many clinicians are unaware that the Brompton’s Cocktail initially was used in England as an analgesic for postthoracotomy pain (Kerrane, 1975). Thus the use of heroin as an analgesic was widespread in England in the 1970s. In two studies of more than 500 patients taking regular doses of heroin orally or parenterally for pain relief for weeks or months, no patients could be documented as having become addicted (Twycross, 1974; Twycross, Wald, 1976).