Physical examination

At the end of the subjective examination it is often important to first summarize the main information of the interview, to clarify open questions and to find agreement with the patient on activity limitations which need to be rehabilitated and coping strategies regarding pain control.

The subsequent physical examination should be considered and communicated as the examination of movement impairments which often, but not always, are prerequisites to the restoration of optimum functional capacity. From a clinical reasoning perspective the physical examination is one of the stages in the therapeutic process in which hypotheses may be confirmed and/or modified.

Planning the physical examination procedures

As already stated, regular planning in critical phases of the therapeutic process is essential to comprehensive clinical practice. Regular planning may have become an automatic, implicit process for the more experienced MSK-physiotherapist, as they will be able to ‘reflect in action’ more frequently (Schön 1983). However, novices may actively enhance their path to professional expertise if they explicitly go through reflection and planning phases after having performed certain procedures of the physiotherapy process (‘reflection on action’). In this learning process it is essential not only to document the results of examination procedures and therapeutic interventions, but also to record the reflections and the planned procedures.

After completion of the subjective examination, it is often useful to summarize its main points and the goals of treatment agreed with the patient so far. It may also be necessary to explain to the patient the objectives of the next stage of the initial assessment – the physical examination.

Planning after the subjective examination as a preparation for the physical examination has three phases:

• Reflection on the subjective examination process – the physiotherapist needs to verify that the subjective examination is sufficiently complete in order to be able to perform a comprehensive physical examination, respecting precautions and contraindications, as well as performing subjective reassessment procedures in subsequent sessions (see Reflection on the subjective examination process, below).

• Expressing hypotheses which will influence the physical examination process. Hypotheses regarding pathobiological mechanisms, sources, contributing factors, precautions and contraindications and management in particular need to be made explicit (see Hypotheses, below).

• Planning the procedures of examination, including anticipation on possible findings, the kind of examination (dosage or extent of examination procedures), sequence of testing and reassessment procedures (see Planning of the physical examination procedures, below).

Precautions to examination procedures

Hypotheses with regard to precautions and contraindications to physical examination and treatment procedures serve to determine the extent of the physical examination that can be safely undertaken. Furthermore, they aid in the decision if contraindications to examination procedures or treatment interventions are present.

The precautions and contraindications are mostly determined by hypotheses with regard to pathobiological processes and neurophysiological pain mechanisms and may include the following factors:

Physical examination and the lumbar spine

Physical examination procedures should follow a structured, integrated format, but they should be flexible enough to be individualized to the patient's needs. This includes precautions to the test-procedures as well as the patient's preferences to move. Sometimes a phenomenological perspective with salutogenic approach to examination may be more beneficial than a therapist-directed approach to testing (see Chapters 1 and 2 of Volume 2 and Chapter 8 of this volume).

The scope of practice of a physiotherapist is reflected in the examination procedures. Making a movement diagnosis is a key issue, rather than making a structural diagnosis (although this hypothesis of pathobiological is an important element in clinical reasoning) and to design examination around safety, interventions and outcomes. In cases where the pain and disability are based on peripheral nociceptive and/or neurogenic processes, one of the goals of examination procedures will be reproduction of the patient's symptoms. However, other information regarding motor control patterns, habitual movement patterns, joint-position sense and proprioceptive feedback, as well as neurological conduction tests, may also be integrated into the examination procedures.

During the physical examination process, it needs regular phases of ‘brief appraisal’, in which the therapist reflects on the findings so far and if the examination procedures can be carried on as planned, or if they have to be adjusted and adapted to the patient's situation.

The physical examination should aim to confirm the hypotheses established through clinical evidence gathering in the subjective examination.

The main aim therefore, using movement analysis and manual examination, is to establish:

• The level of functioning of the movement system, including an impression of the movement potential

• The movement impairments and evidence for the need for movement therapy interventions

• Measures of the effectiveness of such interventions [P/E ASTERISKS***]

• Patient's confidence to move, at times in spite of the pain.

Specific aims of the physical examination should include (Higgs et al. 2008):

• Reproduce the patient's symptoms

• Find comparable signs-adaptive, protective, restrictive

• Find the source/cause of the source/contributing factors

• Establish components, mechanisms, dimensions for each symptom area

• Identify movement impairments (range, symptom response, quality of movement)

• Establish functional activity limitations

• Examine relative to the severity, irritability and nature of the symptoms (movement to P1 or limit with overpressure if necessary)

• Screen other potential components, predisposing factors

• Carry out special testing where appropriate

• Establish the role and desired effects of mobilization/manipulation.

Physical examination procedures place an emphasis on range, symptom response and quality of movements. They are mainly, but not exclusively, impairments based. However, functional demonstration tests may encompass all activities from daily life, which patients have been avoiding.

It is essential to link the therapeutic interventions to the physical examination findings, expressed in reassessment procedures after the application of the intervention. Furthermore, they need to be linked to the results from the subjective examination, which usually are compared at the beginning of subsequent sessions.

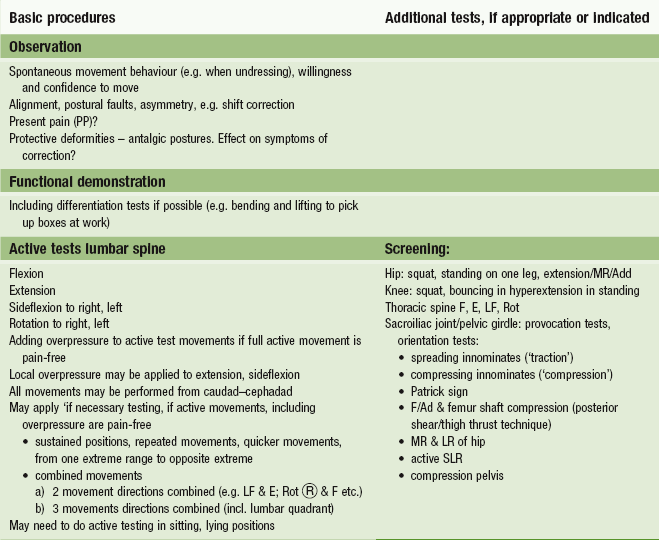

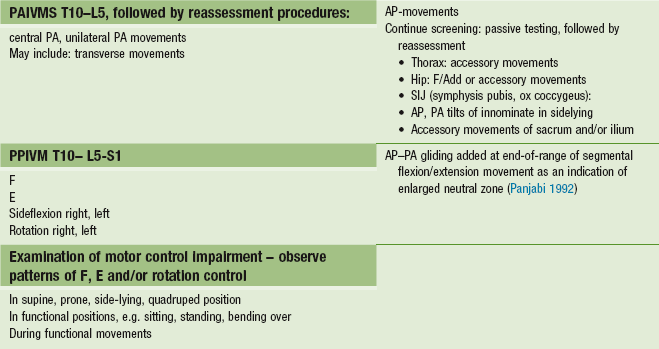

Table 6.8 provides an overview of the general test procedures related to the examination of the lumbar spine and related structures. It should be noted that reassessment procedures are part of the overall physical examination, even if not all planned tests may have been performed. If there is a pain sensation at the beginning of the physical examination (‘present pain’), this needs to be reassessed regularly to ascertain whether this present pain is changing as a result of, for example, active tests. Furthermore, it is possible that examination procedures, e.g. for accessory movements of the spine, may have a therapeutic effect, which has to be evaluated before, for example, hip movements are passively examined.

Table 6.8

Possible physical examination procedures of the lumbar spine and associated movement components

Observation

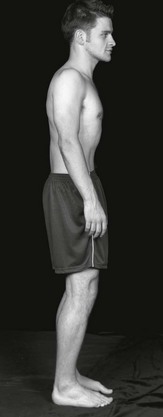

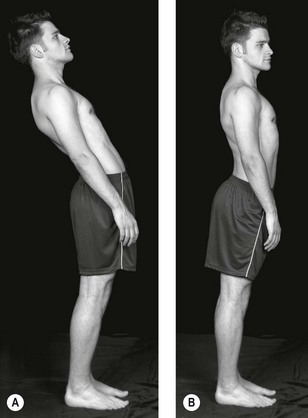

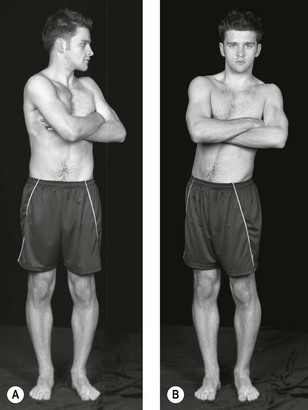

Observing the patient in a variety of positions and a variety of views while standing, sitting and/or lying will enable the clinician to start to identify structural faults, signs of impairment such as wasting or bruising, adaptive and protective mechanisms resulting in postural asymmetry, balance and alignment of body parts, including common faults associated with the risk of developing low back pain (such as sway back, flat back and kypholordosis).

• Furthermore, the therapist gains an impression about the willingness and confidence to move.

• The therapist's in-depth knowledge of alignment, pelvis neutral position, neutral zone, tone etc. will enhance an ability to recognize motor control faults, which could be contributing to deficits in movement (Sahrmann 2011)

• Present pain: any symptoms at resting postures need to be established before embarking on active examination procedures

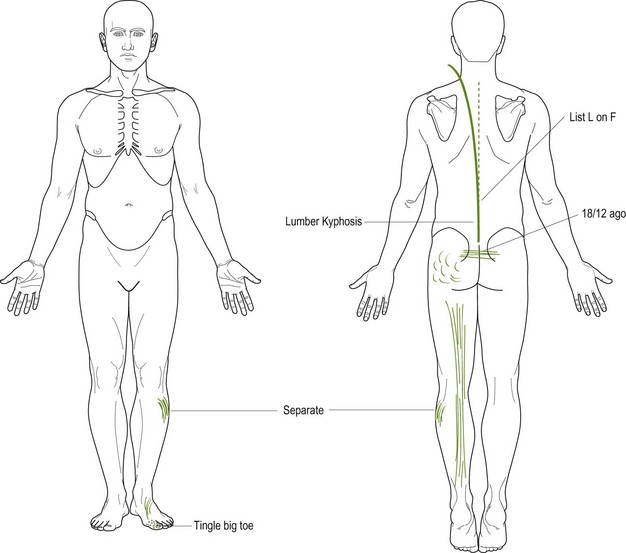

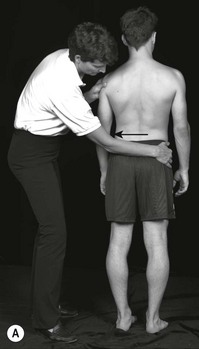

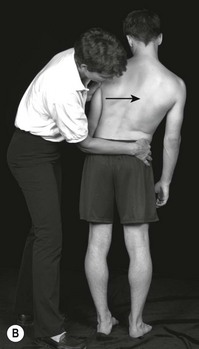

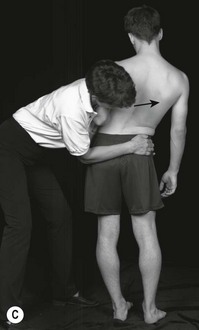

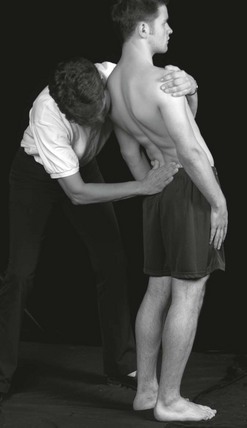

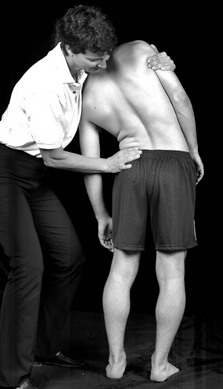

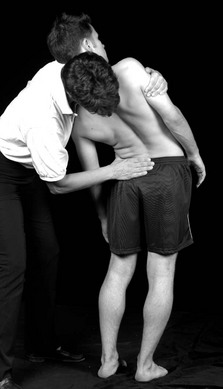

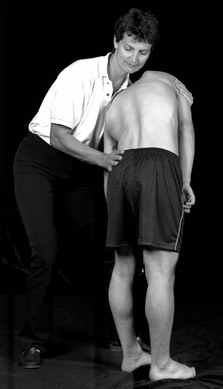

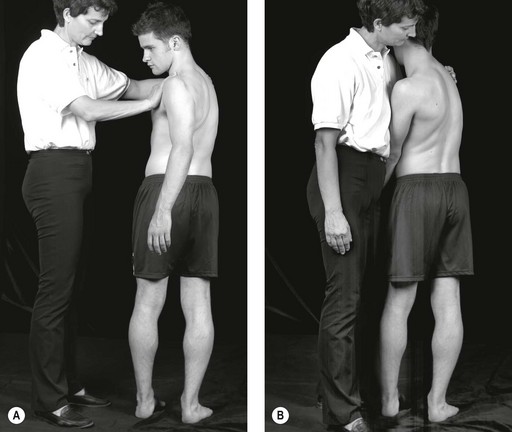

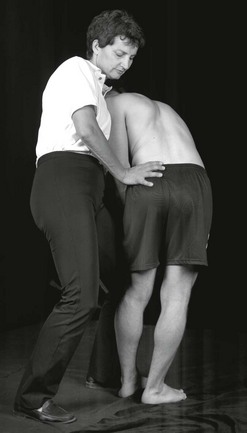

• Correction of faults will clarify whether or not these faults are related to the current patient's symptoms. With the reproduction of symptoms on correction, the posture can be considered as an antalgic posture or protective deformity. See pelvic shift correction in Figure 6.4.

Functional demonstration

Functional demonstration testing may serve different purposes:

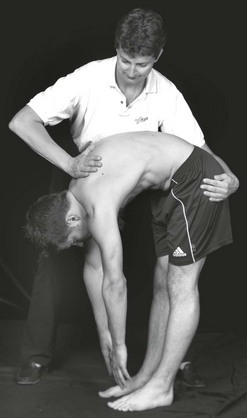

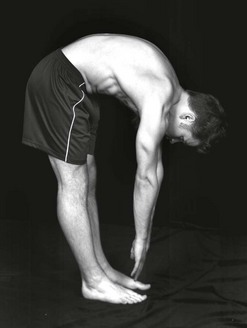

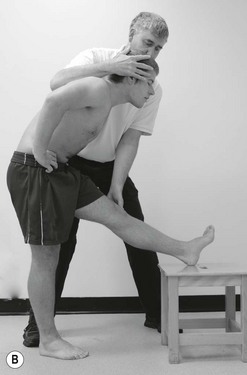

• The patient will often be able to demonstrate a movement or activity, involving the lumbar spine, which reproduces his symptoms. This may be a daily activity that he knows hurts his back, such as bending forwards to tie his shoelaces. He may also be able to demonstrate the movement he was doing when his back was strained – for instance, a backhand at tennis. By asking the patient to demonstrate such an activity to the onset on pain (P1), or to the limit, the therapist can analyze the range of movement, symptom response and quality of movement. This test movement may serve as a parameter (‘asterisk’) for reassessment procedures.

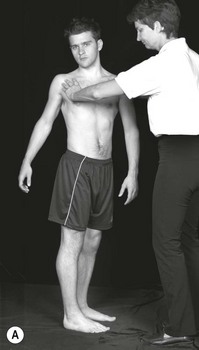

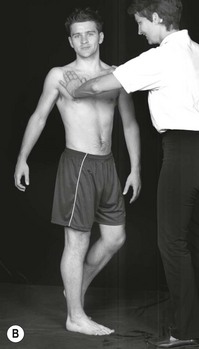

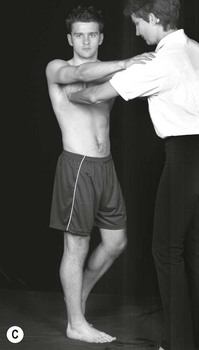

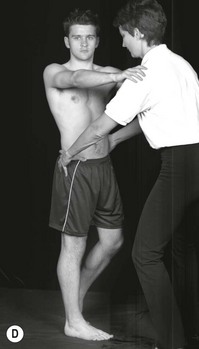

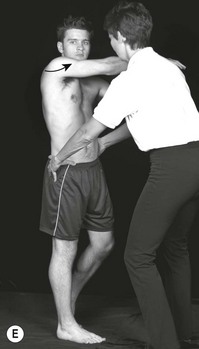

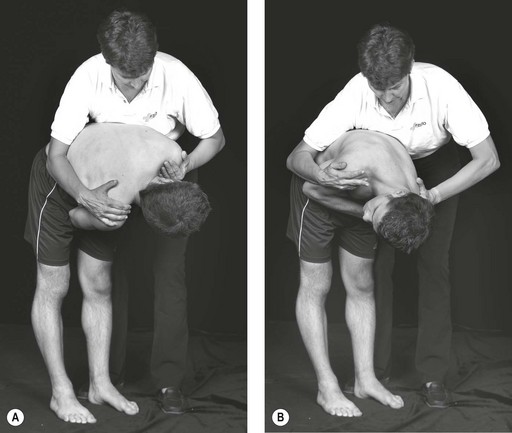

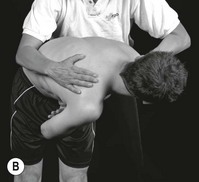

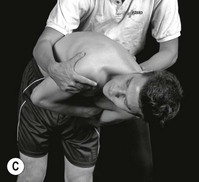

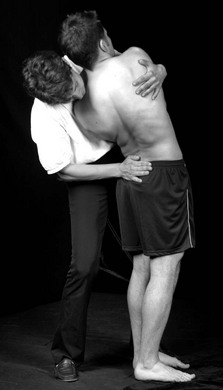

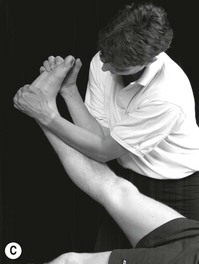

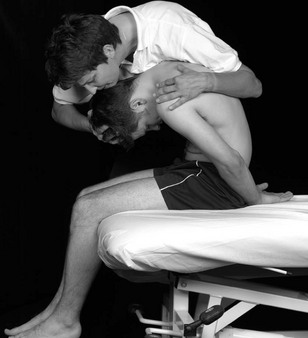

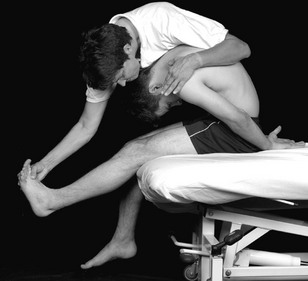

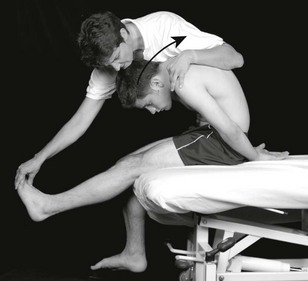

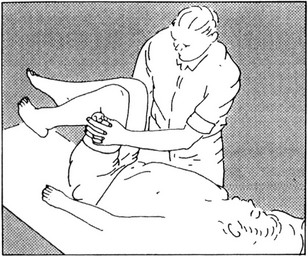

• Differentiation at this stage may help to confirm the movement components at fault if there is any doubt. For example, the patient may be able to reproduce his left buttock pain by demonstrating the backhand tennis shot that injured him. This movement principally involves rotation of the spine and hip. By using the lumbar spine/ hip differentiation test involvement of the spine rather than the hip may be revealed (or vice versa) (Fig. 6.5).

• Further brief appraisal of the spine with active movements and hip with for example the observation of squatting and one-leg hip extension will confirm the need to examine the spine or hip in more detail. Treatment should then reinforce the initial hypothesis.

Further differentiation of the functional demonstration or injuring movement may be of value when improvement has slowed or stopped. For example, after several sessions of treatment, the patient may have to stretch a lot further into the backhand shot to reproduce his pain. Further differentiation may reveal that lumbar extension and lateral flexion to the painful side adds to the buttock pain being reproduced by rotation of the spine during the backhand shot. Therefore a lumbar rotation treatment technique in lumbar extension and ipsilateral lateral flexion will be a valuable technique as a progression of treatment.

Active tests lumbar spine

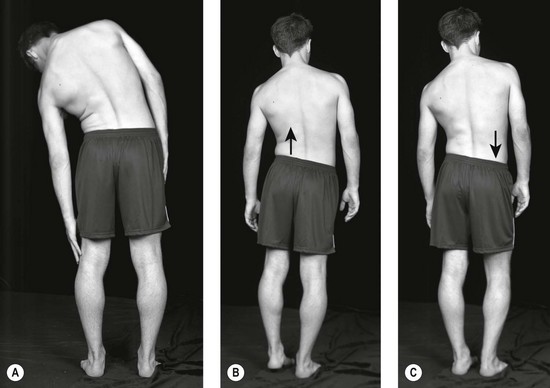

Active testing of the lumbar spine includes flexion, extension, rotation and sideflexion of the trunk.

Initially the gross spinal range and pain response to the movement should be noted. Furthermore it is important to notice the quality of the local intervertebral movement and the pain response. These three aspects serve as parameter for reassessment-procedures (‘asterisks’).

If, for example lateral flexion is limited, the statement may be recorded that the limitation occurs mainly from L3 downwards. Watching the movements from these two aspects (i.e. the gross movements and the local movements) can be likened to taking a photograph with a wide-angle lens for the gross movement, and a second movement using a telephoto lens to highlight the localized limited movement.

However, if these movements do not reproduce any symptoms of the patient, additional stress may be added to the movement, as for example:

• Applying overpressure at the end of the available active ROM. Frequently more range will be gained, when the structures are moved further into the movement in a passive or assisted active way. Overpressure should be applied in a light oscillatory manner, while progressing further into the end of the range of the movement. Any symptom-response by the patient as well as the quality of the resistance perceived by the therapist has to be noted:

overpressure may be applied to the overall movement

overpressure may be applied to the overall movement

overpressure may be applied locally to the intervertebral segments in E, LF and/or rotation.

overpressure may be applied locally to the intervertebral segments in E, LF and/or rotation.

• Application of the movements F, E, LF or Rot:

repeated: do the symptoms increase? Then the movement serves as a parameter for reassessment procedures

repeated: do the symptoms increase? Then the movement serves as a parameter for reassessment procedures

do the symptoms decrease with the repetition of the movement? Then the movement may be adapted to serve as a self-management exercise to control the pain

do the symptoms decrease with the repetition of the movement? Then the movement may be adapted to serve as a self-management exercise to control the pain

moving from one extreme position to the other. This is frequently useful in later treatment sessions, to check if the structures have been cleared sufficiently

moving from one extreme position to the other. This is frequently useful in later treatment sessions, to check if the structures have been cleared sufficiently

sustained: maintaining the movement into end-of-range position, with a slight overpressure. This test variation may be particularly helpful in those cases, where symptoms occur only in sustained daily life positions.

sustained: maintaining the movement into end-of-range position, with a slight overpressure. This test variation may be particularly helpful in those cases, where symptoms occur only in sustained daily life positions.

• Most movements of the trunk in lumbar spine testing occur from a cephadad to caudad direction. However, at times it is more informative to test the movements from caudad to cephadad upwards

• Combination of movement directions. These combinations may give almost endless variations, as two directions, three movement directions may be combined. In some exceptional cases even an accessory movement has to be applied to the movement combination, before symptoms may be reproduces.

• Changing position of the patient: some symptoms may only be reproduced if the tests are being performed while the patient is sitting or lying.

The active tests, including a selection of test variations, are described below.

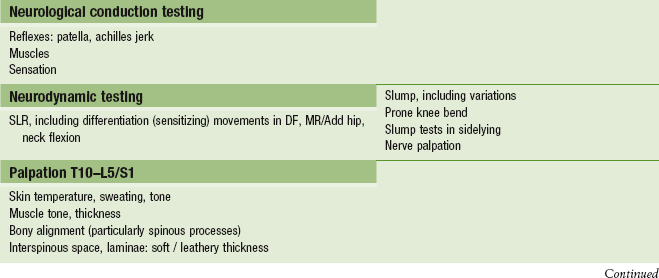

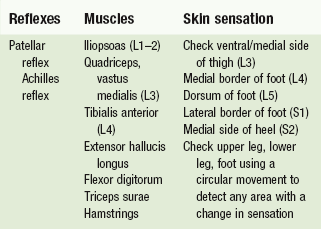

Neurological conduction testing

Neurological conduction testing is the manual testing of reflexes, muscle reactivity and skin sensation to support in clinical decision-making processes.

If recent changes occur, the tests should be monitored regularly during the therapeutic process.

They are indicative of numerous processes in the nervous system (Butler 2000), but they may be particularly helpful in hypothesis generation regarding precautions to examination and treatment procedures and sources of the movement dysfunction, provided that the tests are placed within the overall context of subjective and physical examination findings.

Palpation

Manual diagnosis of the spine, including soft tissue palpation and passive intervertebral testing, has been found to be a reliable means in identifying symptomatic lumbar segmental levels. This is the case when manual diagnosis is compared with spinal anaesthetic block procedures (Jull et al. 1988, Phillips & Twomey 1996). Studies like these demonstrate that inter-tester reliability coefficients may be very high if a reference standard other than the comparison between individual therapist's palpating is chosen. Furthermore, it shows that training enhances the discriminative qualities of palpation skills (Jull et al.1997).

It is suggested to perform palpation examination as follows:

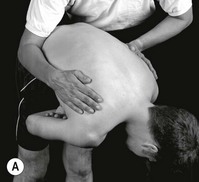

Small differences in temperature can be detected by the skilled therapist (Lando 1994). A small increase in temperature, sweating and skin tone may be indicating the spinal level at fault. All lumbar interspinous processes should be palpated with discernment, as should the lateral surface of the spinous processes. Thickening can occur on one or both sides of the process or in the space, event to the extent where the interspinous process can be completely obliterated by thickened hard tissue.

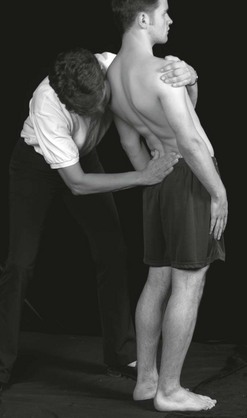

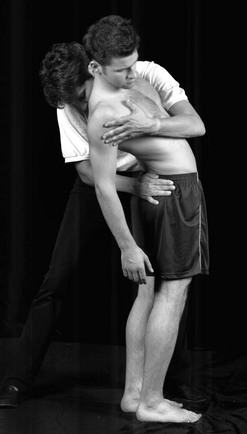

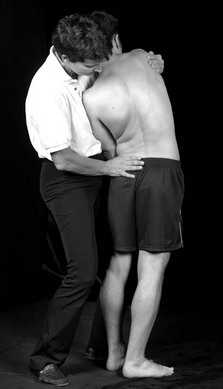

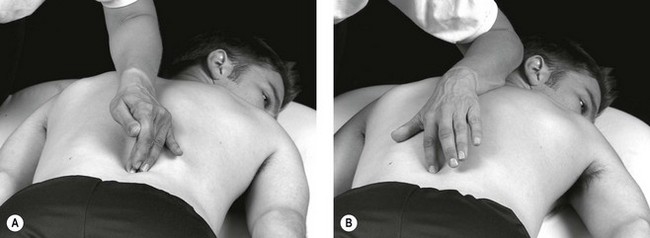

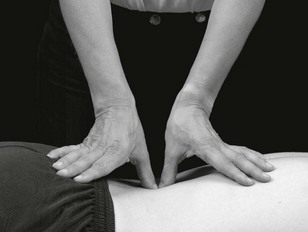

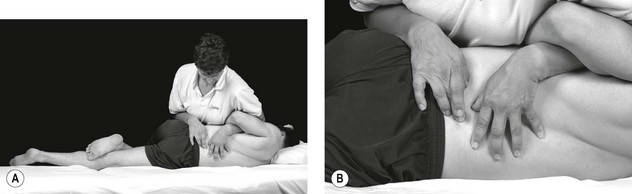

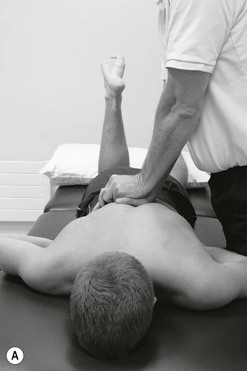

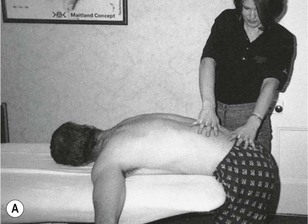

Figure 6.43 shows how this can be performed without the examiner having to move her position. She stands alongside the patient facing his feet, and uses her middle fingertip to probe into the right space and her index finger to dig medially into the left space. She can change rapidly from side to side, and equally rapidly from one level to the next, upwards or downwards.

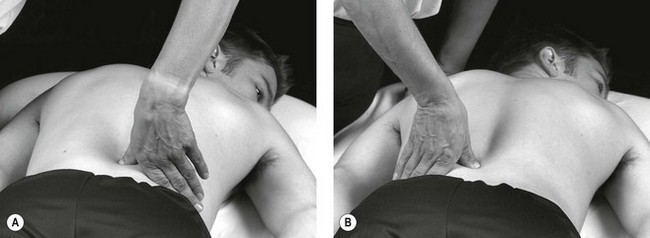

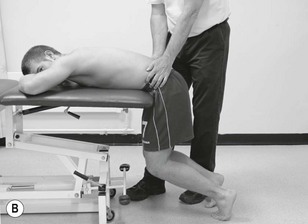

It is also necessary to use the index and middle fingers to palpate into the interspinous space. When doing so, the fingers are held tightly together and oscillated back and forth sideways in an attempt to sink deeply into the space (Fig. 6.44).

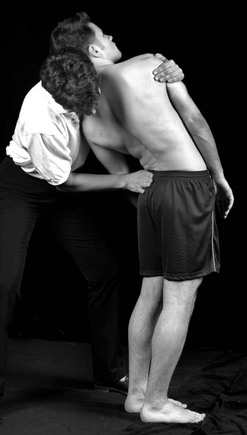

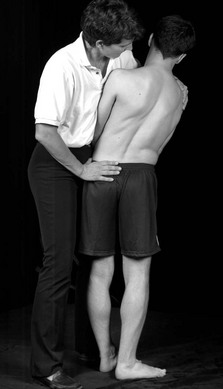

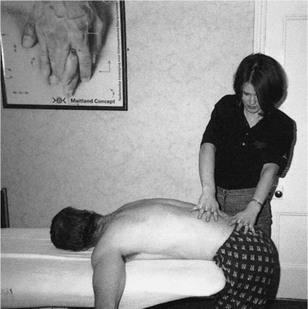

Deeper palpations of the interspinous area are illustrated in Figure 6.45. By using the tip of the thumb a greater depth, even as deep as the lamina, can be reached. An assessment of this depth should be carried out if the more superficial area is normal.

Palpation of the paravertebral soft-tissue structures is illustrated in Figure 6.46. Both thumb tips are utilized, and the probing deep palpation should be carried out in many different directions – medially, lateral, caudally and cephalad. Also, the palpation should not be limited to the interlaminar area but should be extended to the adjacent upper and lower borders of the lamina and over the lamina itself.

B Passive movement testing, as passive intervertebral movement (PAIVMs), and if needed, passive physiological intervertebral movements (PPIVMs). See below.

Nerve palpation may be a diagnostic aid in the assessment of mechanosensitivity of the neural system (Butler 2000). Under normal circumstances peripheral nerves are painless to non-noxious stimuli. However, in cases such as nerve inflammation, gentle provocation, e.g. palpation, can cause pain, protective muscles responses or abnormal tingling-responses (Hall & Quintner 1996).

A comparative study investigating reliability of nerve palpation clinical examination in comparison to pain pressure threshold demonstrated excellent validity, reliability and diagnostic accuracy of nerve palpation in clinical examination at three different sites in the leg (Walsh & Hall, 2009).

Nerves can be palpated at various sites of the buttock and leg, as for example (Butler 2000):

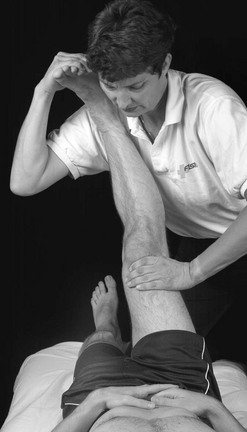

Passive testing

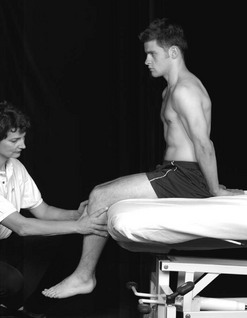

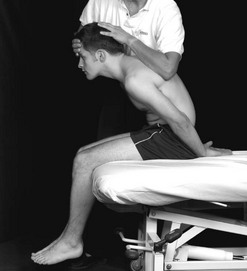

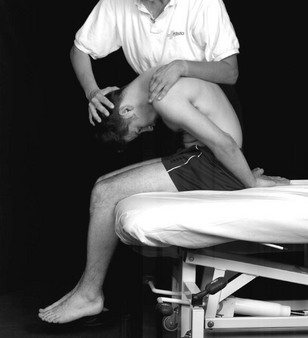

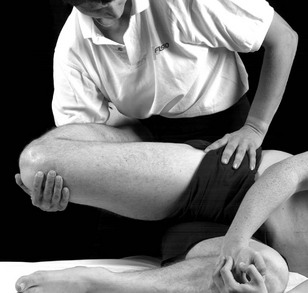

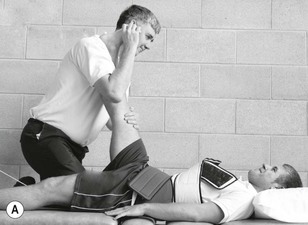

Passive physiological intervertebral movements (PPIVMs): Passive physiological intervertebral movements are performed to examine the intervertebral mobility of one segment of the spine in relation to the neighbouring segment in more detail. Particularly discrepancies in mobility between mobile and stiff neighbouring segments are of interest, which may be indicative of a stability dysfunction of the motion segment.

Over many years it has been debated that the reliability coefficients of intervertebral movement examination may be insufficient; however, it is essential to consider the results from these tests within the overall information of subjective examination findings and other physical examination tests. There are various studies available which demonstrate an increase in reliability values if combinations of test procedures are being used in physical examination (Cibulka et al. 1988). It has been suggested not to condemn examination procedures without offering meaningful clinical alternatives and research from different perspectives with different reference standards (Bullock-Saxton 2002).

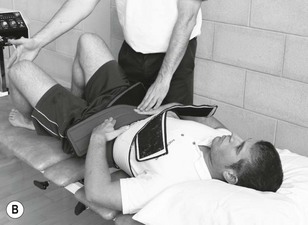

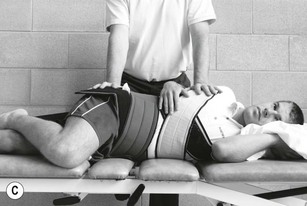

Passive accessory intervertebral movements (PAIVMs)

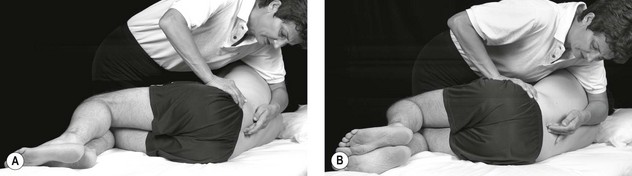

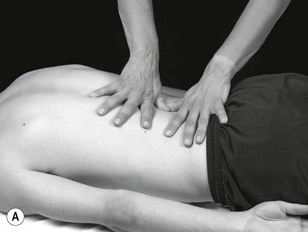

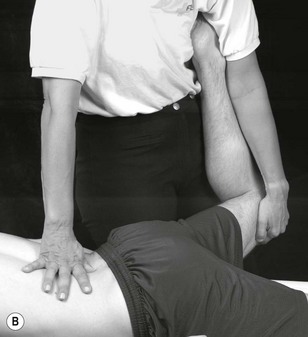

Movement testing with intervertebral accessory movements should be carried out in the posteroanterior, unilateral posteroanterior and transverse directions of the spine. Additionally, anteroposterior movement of the lumbar spine may be performed.

On the one hand accessory movements are essential test procedures in physical examination, but on the other hand all accessory movements may be performed as a treatment technique as well.

Examination of motor control impairment

Comprehensive strategies for motor control of the lumbar spine are widely available in companion texts and supporting references: Sahrmann (2011), O'Sullivan (2005), Richardson et al. (2004). Furthermore, examples of techniques integrating motor control strategies with mobilization techniques are detailed on page 313 of this chapter in the subsection entitled ‘integrated treatment techniques’.

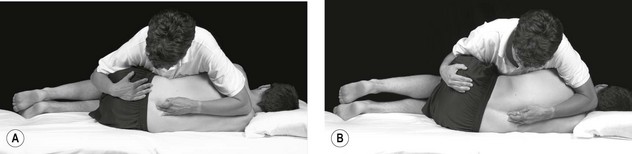

Mobilization and manipulation treatment techniques

As stated before, accessory movements of the spine can be used as treatment techniques. It is a special feature of the clinical reasoning processes of this concept of NMS-physiotherapy that the techniques may be applied in any physiological position of the spine, depending on the symptoms of patient. Also, physiological movements may be applied as a treatment technique. Furthermore, both accessory movements and physiological movements may be combined in an active of passive manner.

For example if the objective of treatment is the mobilization of sideflexion, it is possible to position the patient in sideflexion and then to apply accessory movement techniques and vice versa (see Fig. 6.68).

In this way a clinical rehabilitative approach to the normalization of movement impairments may be pursued. Next to the variations of active and passive arthrogenic techniques, integrated approaches of joint oriented techniques with neurodynamic treatment or motor control strategies often aid in the optimization of treatment results.

In this way almost endless variations of the treatment are possible. Hence the selection, the progression and adaption of treatment techniques must be based upon thorough examination procedures and the effects need to be monitored with disciplined reassessment procedures (see Box 6.5).

More details regarding selection and progression of treatment techniques can be found in Chapter 8 Management of knee disorders (Hengeveld & Banks 2014).

Neurodynamic techniques

The neurodynamic system can be treated in different ways. On the one hand the direct surroundings of the nerves may be treated, for example with passive mobilizations or soft tissue techniques, or directly in which it is distinguished between ‘slider’ and ‘tensioner’ techniques (Butler 2000, Coppieters & Butler 2008, Shacklock 2005)

Lumbar spine mobilization and manipulation techniques linked to clinical and supporting research evidence

In a number of studies it has been demonstrated that the grade, rhythm and direction of movement in which treatment techniques are being performed have an important influence on treatment outcomes. This has been demonstrated in a number of studies with treatment techniques in other joints such as the shoulder (Johnson et al. 2007a, Vermeulen et al. 2006), knee (Moss et al, 2007), elbow (Paungmali et al. 2003), ankle (Yeo & Wright 2011) or hip (Makofsky et al. 2007)

An increasing number of studies demonstrate physiological effects of lumbar mobilization techniques, such as accessory movements or rotation mobilization techniques:

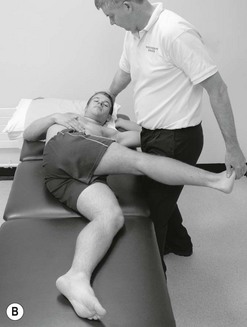

• Perry and Green (2008), in a randomized controlled trial on normal male subjects, found that a grade III oscillatory mobilization applied at 2Hz to the left L4/5 facet joint had an effect on sympathetic activity in the left lower extremity over and above the effects produced in a control and placebo group (see Fig. 6.52).

• Krouwel et al. (2010), in a single blind randomized within subject repeated measurement study design, found in 30 asymptomatic subjects that a posteroanterior mobilization applied to L3 using a force platform to regulate force and frequency of oscillation (1.5Hz) had a significant (p= 0.013) effect on raising measured pressure pain threshold but this was independent of whether the amplitude of the mobilization was large (50–200N) or small (150–200N) (see Figs 6.55 & 6.56).

• Adams et al. (2010), in a review of intervertebral disc healing, suggest that a rotational mobilization might facilitate inter-lamella movements and prevent extensive scarring. In clinical practice, controlled mobilization of a recently-injured spinal level can be difficult due to pain and muscle spasm, but manual therapy can help to reduce pain and normalize muscle tone (Boal & Gillette 2004) and thereby decrease stress concentrations in the disc. Gentle early mobilization could also benefit the bony endplate, because repetitive micromovement stimulates fracture healing in adult long bones (Kenwright et al. 1991; see Fig. 6.69).

• Perry et al. (2011) in a quasi-experimental random design on 50 healthy participants, found that there was a significant (0.0005) increase in lower extremity sympathetic activity after grade V rotation manipulation, compared with extension exercises (see Fig. 6.71A).

Integrated treatment

In clinical practice, physiotherapists have established competencies and skills to deal with impairments of segmental mobility (arthrogenic), motor control and postural stability (myogenic) and nerve mechanosensitivity.

Physiotherapists should design individualized treatment programmes, collaboratively with the patient, based on the contemporary scope of practice, including an understanding of contextual mediators of the pain and disability and a comprehension of whether they would be modifiable or not. All impairment oriented treatments should follow up with an emphasis on restoring functional capacity, and guiding patients in the transition from health care needs to healthy life-styles/healthy living.

It is important that the treatment interventions, being arthrogenic, myogenic and/or neurodynamic oriented, are linked to examination findings. If possible clinical predictor rules may be applied to the selection of low back pain interventions and validated outcome measures such as Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile† (MYMOP; Paterson 1996) may be incorporated in the reassessment processes. Assessment during the application of an intervention and retrospective assessment are outlined in Box 6.8.

Research and best practice clinical guidelines have demonstrated that segmental mobilization and manipulation have a role to play in the treatment of patients with low back pain originating from the lumbar spine (NICE 2009).

Advances in knowledge in neuromuscular function have informed therapists how to fine tune movement, activate muscles and utilize motor control strategies to help patients recover from episodes of back pain (Macedo et al. 2009).

Clinical studies have demonstrated that restoration of ideal nerve gliding and tensioning after nerve injury or entrapment are important therapeutic considerations (Schafer et al. 2011).

What is not well known is the impact on recovery and outcome if these strategies are used in combinations and integrated into functional activities. The following example may illustrate this principle:

What if an SLR is mobilized whilst activating transverse abdominus muscles (TrAb).Will functional recovery be enhanced? The answers to such questions are beyond the scope of this text and the domain of the researcher. The next logical step, however, in selection of manual and movement therapy interventions for movement related NMS disorders of the lumbar spine is the merging of examination findings with treatment. For example, a patient may feel low back pain and neurogenic type symptoms in the back of the leg when bending forwards. The leg symptoms increase when the patient is asked to flex his cervical spine, in addition a posteroanterior glide on L4 reduces the leg pain and with a further addition of abdominal bracing the pain is less still, allowing greater range of cervical flexion. The logical treatment technique must be based on these findings, given that there is no nerve conduction loss and the leg symptoms settle quickly after provocation. The treatment technique is designed around the clinical evidence (supported by C/O evidence that the patient is troubled by leg pain when sitting or bending, the back feels stiff and the whole trunk feels weak).

A possible treatment technique in this case is:

In forward bending to pain + a posteroanterior pressure to L4 + activation of TAb

Active cervical flexion from neutral to full flexion (Fig. 6.78)

The challenge for the therapist is to take manual therapy and movement therapy interventions for low back pain into the domain of impairment interrelationships. Recovery may be enhanced by a lumbar accessory movement in PA-direction, abdominal activation or neural gliders alone; however, the challenge to clinical reasoning and handling skills is to merge integrated examination findings with treatment and design treatment techniques which address the relationship between movement impairments.

Below is a selection of such techniques. The reader is encouraged to reason how and why such techniques have been designed.

Case studies

The following two case examples are included in this chapter to demonstrate:

• The gathering and analysis of patient reported problems and information

• The use of clinical reasoning strategies to enable open-minded and effective sorting out of the clinical information

• Linking patient problems to examination and interventions driven by the patient's functional and cognitive needs

• Evidence informed selection of the most appropriate interventions and treatment techniques

• The use of evaluation to drive progression of treatment towards patient reported outcomes.

References

Adams, MA, Dolan, P. Spine biomechanics. J Biomech. 2005;38(10):1972–1983.

Adams, MA, Stefanakis, M, Dolan, P. Healing of a painful intervertebral dis should not be confused with reversing disc degeneration: Implications for physical therapies for discogenic pain. Clin Biomech. 2010.

Airaksinen, O, Hildebrandt, J, Mannion, AF, et al. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2004;15(Suppl 2):S192–S300.

Abenhaim, L, et al. The role of activity in the treatment of low back pain. Spine. 2000;25(4):1S–31S.

Apkarian, AV, Robinson, JP. Low back pain. IASP Pain Clinical Updates. VXIII(Issue 6), 2010.

Asenlöf, P, Denison, E, Lindberg, P. Individually tailored treatment targeting activity, motor behaviour and cognition reduces pain-related disability: a randomised controlled trial in patients with musculoskeletal pain. J Pain. 2005;6:588–603.

Asenlöf, P, Denison, E, Lindberg, P. Long-term follow-up of tailored behavioural treatment and exercise based physical therapy in persistent musculoskeletal pain: a randomised clinical trial in primary care. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:1080–1088.

Banks, K, The Maitland Concept as a clinical practice framework of NMS disorders, Maitland's Peripheral Manipulation. ed 5. Hengeveld, E, Banks, K, eds. Maitland's Peripheral Manipulation. Edinburgh:Elsevier; 2014;vol 2.

Banks, K, Hengeveld, E. Maitland's Clinical Companion: An Essential Guide for Students. Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

Billis, EV, McCarthy, CJ, Oldham, J. Subclassification of low back pain: a cross-country comparison. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:865–879.

Boal, RW, Gillette, RG. Central Neuronal Plasticity, Low Back Pain and Spinal Manipulative Therapy. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004;27(5):314–326.

Bogduk, N. On the definitions and physiology of pain, referred pain and radicular pain. Pain. 2009;147:17–19.

Borkan, JM, Koes, B, Reis, J, et al. A report from the second international forum for primary care research on low back pain. Spine. 1998;23:1992–1996.

Briggs, AM, Buchbinder, R. Back pain; a national health priority area in Australia. Med J Aust. 2009;190:499–502.

Bruton, A, Conway, JH, Holgate, ST. Reliability: what is it and how is it measured? Physiotherapy. 2000;86(2):94–99.

Bullock-Saxton, J. The palpation reliability debate – the experts respond. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2002;6(1):19–21.

Bunzli, S, Gillham, D, Esterman, A. Physiotherapy-provided operant conditioning in the management of low back pain disability: a systematic review. Physiother Res Int. 2011;16(2011):4–19.

Burton, K, Muller, G, Balagne, F, et al. Chapter 2: European Guidelines for the prevention of low back pain November 2004. Eur Spine J. 2009;15(Suppl. 2):S136–S168.

Butler, D. The sensitive nervous system. Adelaide: NOI-Group publications; 2000.

Butler, D, Moseley, L. Explain pain. Adelaide, Australia: Noi Group Publications; 2003.

Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Scope of Practice. CSP. 2008:1–17.

Cibulka, M, Delitto, A, Koldehoff, R. Changes in innominate tilt after manipulation of the sacroiliac joint in patients with low back pain. Phys Ther. 1988;68:1359–1363.

Cleland, JA. Foreword. In: Glyn PE, Weisbach PC, eds. Clinical Prediction Rules. A Physical Therapy Reference Manual. Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publisher Sudbury, 2011.

Coaz, W. Paradigmenwechsel – auch in der Physiotherapie? Physiother Bull. 1993;33:1–12.

Cook, C, Hegedus, E. Systematic review.Diagnostic utility of clinical tests for spinal dysfunction. Man Ther. 2010.

Coppieters, M, Butler, DS. Do ‘sliders’ slide and ‘tensioners’ tension? Man Ther. 2008;13:213–221.

Cott, CA, Finch, E, Gasner, D, et al. The movement continuum theory for physiotherapy. Physiother Can. 1995;47:87–95.

CSAG. Report on Back Pain. London: Clinical Standards Advisory Group. HMSO; 1994.

Dankaerts, W, O'Sullivan, P. The validity of O'Sullivan classification system (CS) for a subgroup of NS-CLBP with motor control impairment (MCI): Overview of a series of studies and review of the literature. Man Ther. 2011;16:9–14.

Davies, P. Starting again: early rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1994.

De Groot, AD. Het denken van den schaker. Eenexperimenteelpsychologischestudie. Amsterdam: Noord-HollandseUitgeversmaatschappij; 1946.

Edwards, I. Clinical Reasoning in three different fields of physical therapy - A qualitative case study. Adelaidem: School of Physiotherapy, Division of Health Sciences, University of South Australia; 2000.

Fishbain, DA. Secondary gain concept. Definition problems and its abuse in medical practice. APS Journal. 1994;3:264–273.

Flynn, T, Fritz, J, Whitman, J, et al. A Clinical Prediction Rule for Classifying Patients with Low Back Pain Who Demonstrate Short-Term Improvement With Spinal Manipulation. Spine. 2002;27(24):2835–2843.

Ford, JJ, Hahne, J. Pathoanatomy and classification of low back disorders. Man Ther. 2012.

Fordyce, WE. A behavioural perspective on pain. Br J Clin Psychol. 1982;21:313–320.

Fordyce, WE. On pain, illness and disability. J Back Musculoskeletal Res. 1995;5:259–264.

Gifford, L. Pain, the tissues and the nervous system: a conceptual model. Physiotherapy. 1998;84:27–36.

Glynn, PE, Weisbach, PC. Clinical prediction rules.a physical therapy reference manual. Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers Sudbury; 2011.

Gowers, WR. Lumbago: Its lessons and analogues. Br Med J. 1904;1:117–121.

Greenhalgh, T, Hurwitz, B. Why study narratives. In: Greenhalgh T, Hurwitz B, eds. Narrative Based Medicine. London: British Medical Journal Press, 1998.

Hadler, NM. If you have to prove you are ill, you can't get well. Spine. 1996;20:2397–2400.

Hall, T, Quintner, J. Responses to mechanical stimulation of the upper limb in painful cervical radiculopathy. Aust J Physiother. 1996;42(4):277–285.

Hall, AM, Ferreira, PH, Maher, CC, et al. The Influence of the Therapist-Patient Relationship on Treatment Outcome in Physical Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. Phys Ther. 2010;90:1099–1110.

Hancock, MJ, Maher, CG, Laslett, M, et al. Discussionpaper: what happened to the ‘bio’ in the bio-psycho-social model of low back pain? Eur Spine J. 2011;20:2105–2110.

Hayden, JA, van Tulder, MW, Tomlinson, G. Systematic review: strategies for using exercise therapy to improve outcomes in chronic low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:776–785.

Heath, J. Following the story: continuity of care in general practice. In: Greenhalgh T, Hurwitz B, eds. Narrative Based Medicine. London: British Medical Journal Press, 1998.

Hengeveld, E. Clinical Reasoning in Manueller Therapie – eine klinische Fallstudie. Manuelle Therapie. 1998;2:42–49.

Hengeveld, E. Gedanken zum Indikationsbereich der Manuallen Therapie. Teil 1, Teil 2. Manuelle Therapie. 1999;2(3):176–181.

Hengeveld, E. Psychosocial issues in physiotherapy in Switzerland: manual therapists’ perspectives and observations. London: University of East London; 2001.

Hengeveld, E. A behavioural perspective on severity and irritability. IMTA Newsletter. 2002;7:5–6.

Hengeveld, E, Banks, K. Maitland's Peripheral manipulation (vol 2), ed 5. Edinburgh, UK: Elsevier; 2014.

Hides, J, Stanton, WR, Wilson, J, et al. 2010. Retraining motor control of abdominal muscles among elite cricketers with low back pain. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20:834–842.

Higgs, J, Jones, M, Loftus, S, et al. Clinical Reasoning in the Health Professions, ed 3. Amsterdam: Elsevier Butterworth Heinemann; 2008.

Hodges, PW. Pain and motor control: from laboratory to rehabilitation. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2011;21:220–228.

Huijbregts, PA. Introduction. In: Glyn PE, Weisbach PC, eds. Clinical Prediction Rules. A Physical Therapy Reference Manual. Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishes Sudbury, 2011.

IFOMPT (International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Physiotherapists). Educational Standards in Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapy. www.ifompt.com, 2008.

Jensen, GM, Gwyer, J, et al. Expertise in Physical Therapy Practice. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1999.

Johnson, AJ, Godges, JJ, Zimmerman, GJ, et al. The effect of anterior versus posterio glide joint mobilization on external rotation range of motion in patients with shoulder adhesive capsulitis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37(3):88–99.

Johnson, RE, Jones, GT, Wiles, NJ, et al. Active exercise, education and cognitive behavioral therapy for persistent disabling low back pain. A randomised clinical trial. Spine. 2007;32(15):1578–1585.

Jones, M. Clinical reasoning and pain. Man Ther. 1995;1:17–24.

Jull, G, Bogduk, N, Marsland, A. The accuracy of manual diagnosis for cervical zygapophysial joint pain syndromes. Med J Aust. 1988;148:233–236.

Jull, G, Zito, G, Trott, P, et al. Inter-examiner reliability to detect painful upper cervical joint dysfunction. Aust J Physiother. 1997;43:125–129.

Kamper, SJ, Maher, CG, Hancock, MJ, et al. Treatment-based subgroups of low back pain: A guide to appraisal of research studies and a summary of current evidence. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:181–191.

Keating, J, Matyas, T. Unreliable inferences from reliable measurements. Aust J Physiother. 1998;44:5–10.

Kendall, NAS, Linton, SJ, Main, CJ, et al. Guide to assessing psychosocial yellow flags in acute low back pain: risk factors for long-term disability and work loss. Wellington, New Zealand: Accident Rehabilitation & Compensation Insurance Corporation of New Zealand and the National Health Committee; 1997.

Kent, PM, Keating, J. Do primary-care clinicians think that nonspecific low back pain is one condition? Spine. 2004;29(9):1022–1031.

Kent, PM, Kjaer, P. The efficacy of targeted interventions for modifiable psychosocial risk factors of persistent nonspecific low back pain. A systematic review. Man Ther. 2012.

Kent, PM, Keating, JL, Buchbinder, R. Searching for a conceptual framework for nonspecific low back pain. Man Ther. 2009;14:387–396.

Kent, PM, Keating, JL, Taylor, NF. Primary care clinicians use variable methods to assess acute nonspecific low back pain and usually focus on impairments. Man Ther. 2009;14:88–100.

Kenwright, J, Richardson, JB, Cunningham, JL, et al. Axial movement and tibial fractures – a controlled randomized trial of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73-B:654–659.

Kleinmann, A. The illness narratives: suffering, healing and the human condition. New York: Basic Books Harpers; 1988.

Krouwel, O, Hebron, C, Willett, E. An investigation into the potential hypoalgesic effects of different amplitudes of PA mobilisations on the lumbar spine as measured by pressure pain thresholds (PPT). Man Ther. 2010;15:7–12.

Lando, A. Temperature testing by manipulative physiotherapists in spinal examination. In Boyling JD, Palastanga N, eds.: Grieve's Modern Manual Therapy, ed 2, Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingstone, 1994.

MacDermid, JC, Walton, D, Avery, S, et al. Measurement properties of the neck disability index: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(5):400–417.

Macedo, LG, Maher, CG, Latimer, J, et al. Motor control exercises for persistent, nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2009;89(1):9–25.

Macedo, LG, Latimer, J, Maher, CG, et al. Effect of motor control exercises versus graded activity in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: A randomiszed controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2012;92(3):363–377.

Makofsky, H, Panicker, S, Abbruzzese, J, et al. Immediate effect of Grade IV inferior hip joint mobilisation on hip abductor torque: a pilot study. J Man Manipulative Ther. 2007;15(2):103–111.

Maher, C, Latimer, J, Refshauge, K. Prescription of activity for low back pain: what works? Aust J Physiother. 1999;45:121–132.

Main, CJ, Spanswick, CS. Pain management – a multidisciplinary approach. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

Maitland, GD. Movement of pain-sensitive structures in the vertebral canal in a group of physiotherapy students. S Afr J Physiother. 1980;36:4–12.

Maitland, GD. Vertebral Manipulation, ed 5. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1986.

Maitland, GD. The development of manipulative physiotherapy. SVMP-Bulletin. 1995;10:3–5.

Maitland, GD, Hengeveld, E, Banks, K, et al. Maitland's Vertebral manipulation, ed 7. Edinburgh: Elsevier. Butterworth-Heinemann; 2005.

Maluf, KS, Sahrmann, SA, Van Dillen, LR. Use of a classification system to guide nonsurgical management of a patient with chronic low back pain. Phys Ther. 2000;80:1097–1111.

Mattingly, C. What is clinical reasoning? Am J Occup Ther. 1991;45:998–1005.

McGill, SM. The biomechanics of low back injury: implications on current practice in industry and in the clinic. J Biomech. 1997;30(5):465–475.

May, S, Aina, A. Centralization and directional preference: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2012.

McCarthy, CJ, Arnall, FA, Strimpakos, N, et al. The biopsychosocial classification of nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Phys Ther Rev. 2004;9:17–30.

McKenzie, R. The lumbar spine. Mechanical diagnosis and therapy. New Zealand: Spinal Publications; 1981.

Mead, J. Patient partnership. Physiotherapy. 2000;86:282–284.

Moseley, L. Evidence for the direct relationship( between cognitive and physical change during an education intervention in people with chronic low back pain. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(1):39–45.

Moss, P, Sluka, K, Wright, A. The initial effects of knee joint mobilisation on oateoarthritic hyperalgesia. Man Ther. 2007;12:109–118.

Nachemson AL, Jonsonn E, eds. Back and neck pain: Scientific evidence of Cause, diagnosis and treatment. Swedish Council of technology assessment and health care (SBU). Philidelphia: Lippincott Willams and Wilkins, 2000.

Nakao, M, Shinozaki, Y, Nolido, N, et al. Responsiveness of hypochondriacal patients with chronic low-back pain to cognitive-behavioral therapy. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:139–147.

NICE. Low back pain: early management of persistent non-specific low back pain. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (UK). 2009:1–10.

O'Neill, CW, Kurgansky, ME, Derby, R, et al. Disc stimulation and patterns of referred pain. Spine. 2002;27(4):2776–2781.

O'Sullivan, P. 2005. Diagnosis and classification of chronic low back pain disorders: maladaptive movement and motor control impairments as underlying mechanisms. Man Ther. 2005;10(4):242–255.

O'Sullivan, P. It's time for change with the management of non-specific chronic low back pain. Editorial. Br J Sports Med. 2011:4–6.

Paterson, C. 1996. Measuring outcomes in primary care: a patient generated measure, MYMOP, compared with the SF-36 health survey. BMJ. 1996;312:1016–1020.

Panjabi, M. The stabilising system of the spine: Part II Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. J Spinal Disord. 1992;5(4):390–396.

Paungmali, A, O'Leary, S, Souvlis, T, et al. Hypoalgesic and sympathoexcitatory effects of mobilisation with movement for lateral epicondylalgia. Phys Ther. 2003;83:374–383.

Perry, J, Green, A. An investigation into the effects of a unilateral mobilisation techniques on peripheral sympathetic nervous system activity in the lower limbs. Man Ther. 2008;13:492–499.

Perry, J, Green, A, Watson, P. A preliminary investigation into the magnitude of effect of lumbar extension exercises and a segmental rotatory manipulation on sympathetic nervous system activity. Man Ther. 2011;16(2):190–195.

Phillips, DR, Twomey, LT. A comparison of manual diagnosis with a diagnosis established with a lumbar block procedure. Man Ther. 1996;2:82–87.

Pilowsky, I. Abnormal illness behaviour. Chichester: John Wiley; 1997.

Pincus, T, Vlaeyen, JWS, Kenall, NAS, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy and psychosocial factors in low back pain – directions for the future. Spine. 2002;27(5):E133–E138.

Prochaska, J, DiClemente, C. Stages of change and decisional balance for twelve problem behaviours. Health Psychol. 1994;13(1):39–46.

Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders. Scientific approach to the assessment and management of activity-related spinal disorders. A monograph for clinicians. Report of the Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders. Spine. 1987;12(Suppl 7):S1–S59.

RCGP. Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Acute Low Back Pain. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 1999.

Richardson, C, Hodges, P, Hides, J. Therapeutic exercise for motor control and lumbopelvic stabilisation: a motor control approach for the treatment and prevention of low back pain. Edinburgh: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2004.

Sahrmann, S. Movement system impairment syndromes of the extremities, Cervial and Thoracic Spine, ed 2. St Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2011.

Sayres, LR. Defining irritability: the measure of easily aggravated symptoms. Br J Ther Rehabil. 1997;4:18–20.

Schafer, A, Hall, T, Muller, G, et al. Outcomes differ between subgroups of patients with low back and leg pain following neural manual therapy: a prospective cohort study. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:482–490.

Schön, DA. The reflective practitioner. How professionals think in action. Aldershurt: Arena; 1983.

Schmidt, H, Boshuyzen, H. On acquiring expertise in medicine. Educ Psych Rev. 1993;5(3):205–221.

Shacklock, M. Clinical neurodynamics: a new system of musculoskeletal treatment. Edinburgh: Elsevier. Churchill Livingstone; 2005.

Sheehan, NJ. Magnetic resonance imaging for low back pain: indications and limitations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:7–11.

Sims, K. Assessment and treatment of hip osteoarthritis. Man Ther. 4(3), 1999. [136–114].

Slater, SL, Ford, JJ, Richards, MC, et al. The effectiveness of sub-group specific manual therapy for low back pain: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2012;17(2012):201–212.

Smart, K, Blake, C, Staines, A, et al. Self-reporting pain severity, quality of life, disability, anxiety and depression in patients classified with ‘nociceptive’, ‘peripheral neurogenic’ and ‘central sensitisation’ pain. The discriminant validity of mechanism- based classification of low back (+/− leg) pain. Man Ther. 2012;17:119–125.

Stier-Jarmer, M, Cieza, A, Borchers, M, et al. How to apply the ICF and ICF core sets for low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2009;25:29–38.

Thomas-Edding D: Clinical problem solving in physical therapy and its implications for curriculum development. Proceedings of the 10th International Congress of the World Confederation of Physical Therapy, Sydney, 1987.

Thomson, D. Counseling and clinical reasoning: the meaning of practice. Br J of Therapy and Rehabilitation. 1998;5:88–94.

Turner, JA, LeResche, L, Korff Von, M, et al. Backpain in primary care – patient characteristics, content of initial visit and short-term outcome. Spine. 1998;23:463–469.

Van Baar, ME, Assendelft, WJ, Dekker, J, et al. Effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;42:1361–1369.

Van Tulder, M, Becker, A, Bekkering, T, et al, European Guidelines for the management of acute low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2006;(Suppl 15):131–300.

Vermeulen, HM, Rozing, PM, Obermann, WR, et al. Comparison of high-grade and low grade mobilisation techniques in the managemnt of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2006;86(3):355–368.

Vlaeyen, JWS, Crombez, G. Fear of movement/(re)injury, avoidance and pain disability in chronic low back pain patients. Man Ther. 1999;4:187–195.

Vleeming, A, Albert, HB, Östgaard, HC, et al. European Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:794–819.

Waddell, G. A new clinical model for the treatment of low back pain. Spine. 1987;12:632–644.

Waddell, G. The Back Pain Revolution. Edinburgh: Elsevier. Churchill Livingstone; 1998.

Waddell, G. The back pain revolution, ed 2. Edinburgh: Elsevier. Churchill-Livingstone; 2004.

Walsh, J, Hall, T. Reliability, validity and diagnostic accuracy of palpation of the sciatic, tibial and common peroneal nerves in the examination of low back related leg pain. Man Ther. 2009;14(2006):623–629.

Wand, BM, O'Connell, NE. Chronic non-specific low back pain – subgroups or a single mechanism? MBC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:11.

Watson, P, Kendall, N. Assessing psychosocial yellow flags. In Gifford LS, ed.: Topical Issues in Pain, ed 2, Swanpool, UK: CNS Press, 2000.

Watters, W, Baisdenn, J, et al. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis: an evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of degenerative lumbar pinal stenosis. Spine J. 2008;8:305–310.

WHO. ICF – International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva: WHO; 2001.

WHO. WHO global strategy on diet, physical activity and health – A framework to monitor and evaluate implementation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

WHO/EUROPE, What is the best way to treat low back pain?. Health Evidence Network/Publications; 2000. www.euro.who.int.

Yeris, S, Makofsky, H, Byrd, C, et al. Effect of mobilisation of the anterior hip capsule on gluteus maximus strength. J Man Manipulative Ther. 2002;10(4):218–224.

Yeo, H, Wright, A. Effects of performing a passive accessory mobilization technique in patients with lateral ankle pain. Man Ther. 2011;16:373–377.

†MYMOP is a patient-generated, or individualized, outcome questionnaire. It is problem-specific but includes general wellbeing. It is applicable to all patients who present with symptoms, and these can be physical, emotional or social. On the first occasion the questionnaire is completed within the consultation, or with some confidential help. The patient chooses one or two symptoms that they are seeking help with, and that they consider to be the most important. They also choose an activity of daily living that is limited or prevented by this problem. These choices are written down in the patient's own words and the patient scores them for severity over the past week on a seven-point scale. Lastly, wellbeing is scored on a similar scale. On follow-up questionnaires the wording of the previously chosen items is unchanged, and follow-up questionnaires may be administered by post if required. (Source: www.sites.pcmd.ac.uk/mymop/)

; B F + LF

; B F + LF  + Rot L; C F + LF

+ Rot L; C F + LF  + Rot R.

+ Rot R.

flexed position (depending on the daily life activity which provokes the symptoms e.g. pain occurs while brushing teeth)

flexed position (depending on the daily life activity which provokes the symptoms e.g. pain occurs while brushing teeth)

.

.

generalized overpressure.

generalized overpressure.

+ E

+ E

+ F.

+ F.

+ Rot

+ Rot  .

.

+ Rot

+ Rot  .

.

+ E.

+ E.

+ LF

+ LF  .

.

+ LF

+ LF  .

.

+ F + LF

+ F + LF  .

.

).

).

Do

Do

, do

, do  x axis).

x axis).

, do Th).

, do Th).

, do

, do

if I have walked for half an hour so I have to sit down

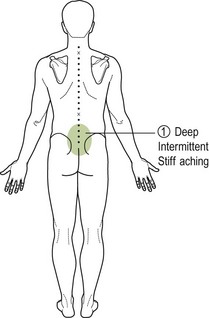

if I have walked for half an hour so I have to sit down An area from just above the iliac crests to the mid-sacral area, in the middle of the spine, deep, intermittent stiff and aching. Radiating both sides but more to the left (

An area from just above the iliac crests to the mid-sacral area, in the middle of the spine, deep, intermittent stiff and aching. Radiating both sides but more to the left (

when I have to bend and twist when sitting. I am a bit worried about going back to work because I have to do a lot of bending and twisting.

when I have to bend and twist when sitting. I am a bit worried about going back to work because I have to do a lot of bending and twisting. more and more. If I sit down for a while, I am ok after 10 minutes.

more and more. If I sit down for a while, I am ok after 10 minutes.

. It is a lot better now but still not fully better, so the Doctor has sent me here. I was lifting a plank of wood and it slipped in my hand. This jarred my back

. It is a lot better now but still not fully better, so the Doctor has sent me here. I was lifting a plank of wood and it slipped in my hand. This jarred my back  as I bent and twisted to catch it before it fell on my leg.

as I bent and twisted to catch it before it fell on my leg. increased in intensity].

increased in intensity]. when stretches [lumbar flexion and rotation, hip flexion 90° and lateral rotation 30°, reaches ankle].

when stretches [lumbar flexion and rotation, hip flexion 90° and lateral rotation 30°, reaches ankle].  ISQ with activation of abdominal muscles, lateral glide of the hip and neural loading [cervical flexion in lumbar flexion and left lateral flexion].

ISQ with activation of abdominal muscles, lateral glide of the hip and neural loading [cervical flexion in lumbar flexion and left lateral flexion]. . ISQ with activation of abdominals and neural loading.

. ISQ with activation of abdominals and neural loading.

. ISQ with activation of abdominal and neural loading.

. ISQ with activation of abdominal and neural loading.

unilateral posteroanterior pressure grade III+ for 3 minutes, repeated twice. Grade III+: with slight pain in rhythm of the movement. The aim is to reduce the pain and restriction in a compression pattern which is occurring through the active range of movement. Assessment during treatment. After 2–3 minutes sense of resistance changing (‘freer’) and patient felt less pain.

unilateral posteroanterior pressure grade III+ for 3 minutes, repeated twice. Grade III+: with slight pain in rhythm of the movement. The aim is to reduce the pain and restriction in a compression pattern which is occurring through the active range of movement. Assessment during treatment. After 2–3 minutes sense of resistance changing (‘freer’) and patient felt less pain. unilateral posteroanterior pressure inclined medially grade IV+ for as a progression of treatment 3 minutes, repeated twice. The aim is to reduce the pain and restriction compression pattern. During treatment pain was provoked with the stiffness at end of range. The pain reduced as the stiffness reduced and full range was achieved.

unilateral posteroanterior pressure inclined medially grade IV+ for as a progression of treatment 3 minutes, repeated twice. The aim is to reduce the pain and restriction compression pattern. During treatment pain was provoked with the stiffness at end of range. The pain reduced as the stiffness reduced and full range was achieved. for 3 minutes repeated once. Effects during treatment – after 2 minutes each time discomfort settled, resistance improved.

for 3 minutes repeated once. Effects during treatment – after 2 minutes each time discomfort settled, resistance improved.