Management of Open-Bite Malocclusion

Flavio Andres Uribe, Nandakumar Janakiraman, Ravindra Nanda

Achieving an ideal treatment outcome depends on an accurate diagnosis in three dimensions, a good understanding of the interaction between the neuromuscular components of the orofacial region and the craniofacial skeleton, and the ability to provide individualized treatment mechanics.1 Early research in the 1950s and 1960s clearly showed the mutual dependence in three dimensions of the dentofacial complex.2 Despite the interest in three-dimensional (3D) diagnosis and treatment planning in orthodontics, the most widely used classification, introduced by Edward Angle, describes the malocclusion only in the anteroposterior dimension,2 providing little information about the vertical or transverse facial and dental relationships.

The importance of the vertical dimension of the face was first recognized by Downs and later discussed by Wylie and Johnson.3 Sassouni and Nanda2 comprehensively described the skeletal characteristics caused by dimensional and positional imbalances in both vertical and anteroposterior dimensions. Their classification of the facial types included an assessment of vertical disproportions. The terms skeletal deep bite and skeletal open bite were used to describe the two extremes observed in this dimension.2,4

Sassouni4 further investigated the vertical dimension of the dentofacial complex and found that disproportions in this dimension can be a cause for anteroposterior dysplasia. He further stated that addressing the vertical component of the malocclusion would bring about the desired outcome in the anteroposterior dimension.

During the same period, Schudy introduced the concept of facial divergence as the proportion of facial height to facial depth. He surmised that the ratio of depth to height affects not only the facial type but also the overbite. Hyperdivergent and hypodivergent facial types were described as the two extremes of facial divergence.5 Later, Nanda showed that these vertical patterns are established early in life, even before the eruption of permanent teeth.6

Various terms used to describe increased vertical facial dimension have been used interchangeably, describing angles, growth tendencies, and occlusal traits and even implying etiology. The following terms are used most commonly to describe an increased vertical facial pattern: dolichofacial, leptoprosopic, hyperdivergent, skeletal open bite, high angle, backward rotator, adenoid faces, long face syndrome, and vertical maxillary excess. Although the relationship is not necessarily direct, an increased vertical facial pattern has been associated with an anterior open-bite malocclusion.

Open bite has been defined as an occlusal characteristic in which upper and lower teeth are not in contact and vertical overlap does not exist. The term was first introduced by Caravelli as early as 1842.7 Although this type of malocclusion can occur unilaterally or bilaterally in the buccal segments, it most often occurs in the anterior segment. The anterior open-bite malocclusion is most obvious when a clearance is apparent between the upper and lower incisors from the frontal view. Of course, clinical diagnosis of an anterior open bite then becomes somewhat subjective because the diagnosis depends on the horizontal plane of assessment (Fig. 9-1).

Figure 9-1 Evaluation of an anterior open bite from different planes. A, Minimal amount of anterior open bite is evident from the uppermost view angle. B, Increased open bite compared to A. Plane of assessment is almost perpendicular to the occlusal plane. C, The lowermost view angle reflects an extensive open bite, one that does not appear as extensive from the top view. The apparent magnitude of the open bite depends on the steepness of the occlusal plane and/or the plane of evaluation.

This chapter describes the characteristics of anterior open bite, its etiology and differential diagnosis, contemporary and evidence-based treatment approaches in growing and nongrowing patients, treatment alternatives and retention protocols for successful management, and increased predictability of stability in the long-term.

Characteristics of Anterior Open Bite

Björk8 described the skeletal and dental characteristics common in patients with anterior open bite. He discussed the morphological characteristics associated with downward and backward mandibular rotation during growth. These characteristics include distal condylar inclination, short ramus, antegonial notching, obtuse gonial angle, excessive maxillary height, straight mandibular canal, thin and long symphysis, long anterior facial height, short posterior facial height, steep mandibular plane, divergent occlusal planes, acute intermolar and interincisal angulation, anteriorly tipped-up palatal plane, and extruded molars. Among all of these characteristics, the steepness of the mandibular plane has been considered the key skeletal finding and thus the term high-angle patients.

Most soft tissue characteristics parallel those of the hard tissues: long lower facial height, steep mandibular plane, and short posterior facial height. In addition, a large interlabial gap is most evident on clinical examination of patients with a skeletal open bite9–11 (Fig. 9-2).

Figure 9-2 A large interlabial gap (>3 mm) is the most significant soft tissue characteristic of a skeletal open bite. A, Profile view. B, Frontal view with lips closed, showing the mentalis strain resulting from a large interlabial gap.

Although all of the skeletal characteristics just mentioned are associated with an anterior open bite, in one study12 only 13% of patients who had a cephalometric criterion for open-bite tendency had a vertical space between the incisors perpendicular to the occlusal plane. In many instances the skeletal open bite is camouflaged by overeruption of the anterior teeth. This issue makes classification of an open bite as either skeletal or dentoalveolar difficult. Often this malocclusion is the result of a combination of both factors.

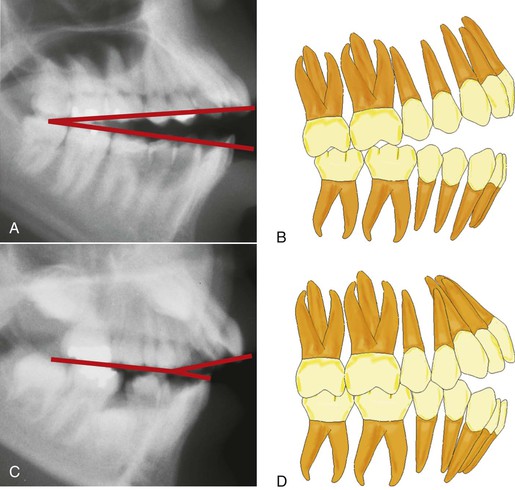

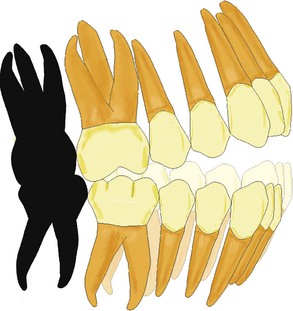

Studies10,11,13 have indicated that skeletal open bites are often related to excessive vertical growth of the dentoalveolar complex, especially in the region of the posterior maxillary molar (Fig. 9-3). Conversely, dental anterior open bites are primarily due to reduced incisor dentoalveolar vertical height14 (Fig. 9-4). The difference between these two types of open bites is also reflected in the occlusal planes. The skeletal type of malocclusion generally has occlusal contacts only at the molar level, with both occlusal planes diverging anteriorly,15 whereas the occlusal planes in the dentoalveolar open bite usually diverge from the first premolar forward (Fig. 9-5).

Figure 9-3 Excessive vertical height of the buccal segments is a common characteristic of skeletal anterior open-bite patients.

Figure 9-4 Reduced anterior dentoalveolar height characterizes a dental anterior open bite. A, Reduced incisal display as a result of restricted eruption of the maxillary incisors from a thumb-sucking habit. B, Anterior open bite from the finger habit. C, Reduced distance from the apex of the maxillary central incisors to the palatal plane.

Etiology

The causes of open-bite malocclusions are often related to the environment. Among the environmental factors, the concept of form following function has been singled out as a primary cause. An example is the role of the muscular posture affecting, directly or indirectly, the development of skeletal and dental open bites.

Airway and Craniofacial Pattern

Airway maintenance is an important factor in determining the posture of various orofacial musculatures. Nasopharyngeal obstruction induced experimentally in primates16,17 contributed to a lower position of the tongue and mandible, with the lips separated to maintain airway patency. This positional change led to increased anterior facial height, steeper mandibular plane, and larger gonial angle. Of note, the responses of the primates varied greatly. When extrapolating these findings to humans, clinicians should be aware of the individual variations in response to similar stimuli when assessing the contribution of mouth breathing to craniofacial deformity.16,17 Additionally, the experimental animal model does not translate well to humans because complete nasal obstruction is uncommon; the usual mode of respiration is oronasal.18

The association between mouth breathing and the vertical pattern of facial growth is rather weak. With the evidence available, predicting which children are at risk, at what age the growth pattern will change due to nasal obstruction, how much nasal obstruction must occur to alter the growth pattern, and finally if the acquired pattern is reversible is difficult.18 Fields et al.19 compared the mode of breathing in adolescents with normal and hyperdivergent vertical facial patterns. In patients with the hyperdivergent pattern, tidal volume and minimum nasal cross-sectional area were similar to those of patients with normal facial patterns but nasal respiration was significantly reduced. The authors concluded that the mode of breathing could be behaviorally determined rather than being anatomically dependent. Hence the relationship between nasopharyngeal obstruction and long face syndrome in children appears to be multifactorial.

Shanker et al.20 conducted a longitudinal assessment of the interrelationships between the upper respiratory parameters (nasal resistance, breathing mode) and dentofacial morphology in 8- to 12-year-old children. The results indicated that the pattern of respiration was neither constantly oral nor constantly nasal and that the children often switched from one pattern to the other over time. This alteration in breathing pattern over time may not have a clinically significant effect on the dentofacial complex. Further, in a comparison of the indicators of the long face pattern, no indicator differed significantly either statistically or clinically between nasal and oral breathers. On the basis of these findings, the transient mode of respiration may not significantly alter the pattern of craniofacial growth; thus surgical intervention to alter the mode of respiration may not be recommended. Souki et al.21 reported that the vertical growth pattern in a group of mouth breathers was no different after tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy than in a control group of mouth breathers.

With the advent of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), research is being conducted to evaluate the relationship of the airway to the craniofacial dimensions.22,23 In the past, these studies focused on the airway relationship in the two dimensions registered by lateral cephalograms.24–26 With a 3D view, the contribution of the transverse dimension and the possibility of analyzing volumes will provide better evidence of this relationship. Three-dimensional CBCT-based evaluation of the upper airway is more accurate and more reliable than evaluation based on two-dimensional (2D) images.27

CBCT data may indicate an association between size of the airway and different craniofacial patterns and possibly relate the 3D anatomy to function. Using CBCT, Alves et al.28 found that the dimensions of the pharyngeal airway were greater in nasal breathers than in mouth breathers. However, a consideration of variables that might affect the findings of these studies is important. The variables include positioning of patients during image acquisition, impact of the respiratory phase, airway patency, head posture, mandibular morphology, and the position of the tongue and hyoid bone. Hence standardization of CBCT settings and definition of the anatomic boundaries of the airway are necessary.23,27 Because a standardized protocol for airway imaging is not available, making a reasoned judgment of the validity and reliability of upper airway models based on three-dimensional CBCT imaging is often difficult.29

Muscle and Its Contribution to Facial Pattern

A generally accepted notion is that hyperdivergent patients have weaker mandibular muscles and a weaker bite force than hypodivergent patients do. However, this relationship between the dentofacial complex (form) and jaw muscles (function) is still a matter of controversy. Whether or not the strength of the masticatory muscles is the primary determinant of the dentofacial complex is still not clear.30 The influence of muscles of mastication on the orofacial region is difficult to understand but can be at least theoretically determined by analyzing its geometric properties (size of the muscle, orientation of the muscle, and mechanical advantage), intrinsic properties (muscle fiber size and distribution), and muscle recruitment patterns.31

Muscle Size

The total force exerted by a muscle is directly related to its cross-sectional area of muscle fibers, which can be measured by using computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The cross-sectional area can give some insight into the strength of the masticatory muscle in the various facial types. The size of masseter and medial pterygoid muscles was larger by 50% in brachyfacial subjects than in dolicofacial subjects. The size difference was about 30% larger in brachyfacial subjects for the temporalis muscles and about 6% larger for the anterior digastric muscle. Among the masticatory muscles, the cross-sectional area of the masseter is highly sensitive to the variation in long face subjects. The difference in size indicates a different loading pattern during function in hyperdivergent and hypodivergent patients.31

Muscle Orientation

When analyzed in the sagittal plane, the masseter was obliquely oriented in long face subjects and vertically oriented in short face subjects. Because of the difference in the spatial orientation of the masseter and medial pterygoid muscles in the two groups, the vertical force component of the muscles was 3% and 2% higher in short face subjects than in long face subjects respectively. Due to this difference in orientation of masseter and medial pterygoid muscles, Spronsen31 concludes that the brachyfacial subjects are more efficient in producing vertically directed bite forces. However, the differences in bite force between the two groups were quite small, even though they were statistically significant.31

The moment arm in the masticatory muscular force system is the perpendicular distance from the summit of the mandibular condyle to the line of action of the force. Small differences in values in the moment arm of the masseter and medial pterygoid muscles were observed in subjects with normal, hypodivergent, and hyperdivergent facial patterns. The moment arm at the region of the lower first molar was 8% smaller in the short face group than in the long face group. This difference is due to the morphology of the mandible and the spatial orientation of the masticatory muscles to the morphology between the short face and long face subjects. Because of the smaller moment arm and the associated biomechanical advantage, slightly larger bite forces were produced in brachyfacial subjects when compared with dolicofacial subjects.31

The maximum biting force was 155 N in long face subjects and 356 N in normal face subjects.32 In other studies33 bite force was 380 N in long face subjects and 720 N in short face subjects. However, the bite forces in children with hyperdivergent and normal facial patterns are similar,34 although the forces differ significantly in adults of both groups. Explaining why the maximum bite forces are lower in long face groups than in other groups is difficult. Can this difference in bite forces be due to differences in the composition of muscle fiber? Rowlerson et al.35 found that subjects with open bites had a higher percentage of type I fibers (slow contracting and fatigue resistant) in masseter muscle than did deep bite subjects. In contrast, compared with open-bite subjects, deep bite subjects had more type II fibers (fast contracting and relatively fatigable). A correlation exists between the vertical growth pattern and particular muscle fibers but further studies are necessary to evaluate the cause and effect relationship between the type of muscle fiber and vertical growth pattern of the face.

Based on the above findings, Van Spronsen31 concludes that the influences of muscle orientation, moment arms, and biomechanical advantage on the open-bite malocclusion are generally weak. The influence of maximum bite forces in determining craniofacial morphology is controversial, because electromyographic studies have shown that maximum bite forces are produced for only 6 minutes per day.36 The influence of the bite force of jaw muscle due to shorter duration of action on the developing craniofacial complex may be negligible or small.37 Furthermore, Ueda et al.38 reported that 90% of masticatory muscle activity is of low amplitude and may be related to long face morphology.

Finally, the vertical growth pattern is established early in life39,40; the craniofacial morphology is visible even before the development of weak musculature. Therefore the strength of association between the long face and weak musculature is rather weak and questionable. A hyperdivergent growth pattern, which is under a strong genetic influence, might result in a dentofacial morphology with weak musculature. These environmental interactions (weak musculature and others) on the genetically determined craniofacial structures could possibly determine the final expression of long face morphology.31

Role of the Tongue in Anterior Open Bite

Another major etiologic factor that reportedly contributes to open bites is an imbalance between the tongue and the perioral musculature.41 Various habits, such as tongue thrusting and thumb- and finger-sucking, and anatomic conditions, such as macroglossia, have been reported as causative factors. These factors contribute to the development of an open-bite malocclusion by adversely affecting the development of the anterior dentoalveolar complex and inhibiting the normal eruption of teeth.42 The force of the tongue or finger against the lingual surface of the incisors also causes concurrent flaring of the upper anterior teeth.43

Clinicians should carefully consider the role that the tongue plays in the etiology of open bite. Both the function and the anatomy of the tongue must be evaluated. From an anatomic point of view, a large tongue (macroglossia) can be responsible for splaying the anterior teeth and thus cause an open bite. Unfortunately, macroglossia is difficult to diagnose because no simple method is available to measure the volume of the tongue.44 Certain features noted during clinical examination that indicate macroglossia include spacing and flaring of the anterior teeth, indentations on the lateral borders of the tongue, and lateral extension of the tongue onto the occlusal surface of the lower teeth45 (Fig. 9-6).

Figure 9-6 Patient with a large tongue. A, Intraoral clinical exam shows indentations on the lateral borders of the tongue and coverage of the occlusal surfaces of all lower teeth. B and C, Upper and lower arches depict generalized spacing.

From a functional point of view, deviant patterns of swallowing or tongue thrusting may contribute to the development of anterior open bite. However, some researchers claim that tongue thrusting appears to be a compensatory or adaptive behavior to the altered craniofacial skeleton. Swallowing, chewing, and speaking have little impact on the morphology of the dentition but the consequences of postural aberrations leading to changes in the resting pressure and posture of the tongue are marked.46 Some clinicians have proposed that the resting posture of the tongue is a more significant factor contributing to the open bite, compared to any of the temporal active functional muscular activity.

Several techniques, such as cineradiography, videofluoroscopy, ultrasonography, and, more recently, kinetic MRI, have been used to evaluate tongue movements during deglutition.47 Akin et al.47 used cine MRI to compare tongue movements during swallowing between subjects with anterior open bite and control subjects. The images were obtained during stage 1 (loss of contact of the dorsal tongue with the soft palate), stage 2 (passage of the bolus head across the posterior/inferior margin of the ramus of the mandible), and stage 3 (passage of the bolus head through the opening of the esophagus). Significant differences were found between stages 2 and 3, the pharyngeal and esophageal stages, which are involuntary. The posture of the tip of the tongue was more anterior during all stages in the open-bite subjects than in the control subjects. These results indicate that, during swallowing, the tip of the tongue is thrust forward in open-bite subjects to maintain the anterior oral seal. During normal swallowing the position of the posterior dorsum of the tongue was significantly elevated in stages 2 and 3, a change that might be a normal movement for propulsion of a food bolus and protection of the airway. However, in the open-bite group, the anterior part of the dorsum of the tongue is lowered and its middle part is elevated. As a compensatory mechanism to avoid aspiration during swallowing, the rear part of the tongue has minimal or no movement and marked movements occur in the anterior and middle parts of the tongue.

Thumb-Sucking

Prolonged thumb-sucking is another common environmental factor often associated with anterior open bite. Children who suck their thumbs have a higher prevalence of anterior open bite than do control subjects of a similar age group.48 Additionally, finger-sucking and a hyperdivergent facial pattern are significant risk factors not only for development but also for increased severity of an open bite.49

Trauma

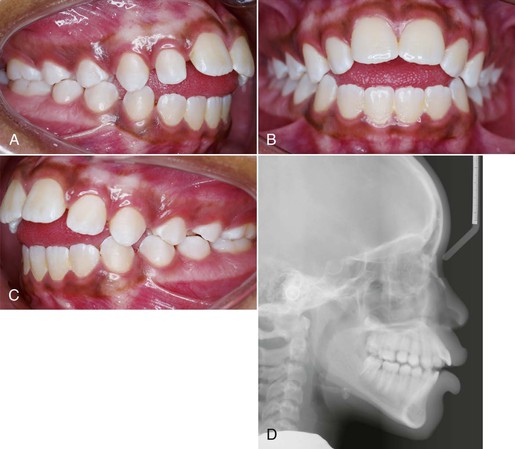

Skeletofacial and dentoalveolar trauma are also etiologic factors of anterior open bite. Skeletal trauma involving the condyles can cause severe anterior open bites.50 Arrested condylar growth or ankylosis of the condyle results in altered vertical growth of the mandible, clinically manifested as an anterior open bite. Trauma to the dentition, particularly the incisors, can result in localized anterior open bite if the damaged teeth become ankylosed before the patient finishes growing51 (Fig. 9-7).

Figure 9-7 Anterior open bite exacerbated by an ankylosed maxillary left central incisor due to previous trauma. A, Smile view showing the reduced smile display in the ankylosed incisor. B, Frontal intraoral view showing the significant anterior open bite as a result of the ankylosed incisor.

Finally, anterior open bites may develop in patients with degenerative diseases involving the condyles. Idiopathic condylar resorption52 and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis53 are two pathological conditions that involve condylar resorption.

Genetics

The genetic component of an open bite is related primarily to the patient's inherent growth potential. Traits such as anterior facial heights are, to a large degree, inherited.54 Obtaining a thorough family history will help in predicting a patient's growth potential.

Although the main goal in a child is to predict the vertical skeletal relationships at the end of growth, growth patterns are established early in life and maintained in most people.55,56 Therefore a skeletal open-bite pattern could be evident in the early mixed dentition. Numerous cephalometric planes have been used independently and combined to detect the early skeletal open-bite pattern. The overbite depth indicator index of the primary dentition might be useful for predicting a skeletal open-bite tendency in adolescence.57 This index is a composite of cephalometric measurements involving the mandibular and palatal plane angles in relation to the A-B line and the Frankfort horizontal plane, respectively.

The Björk indicators are another useful method to help predict vertical growth patterns. However, these indicators are based on patients with extreme variations in vertical facial growth; thus they may be of limited value in patients with less severe open-bite skeletal patterns.58,59

The genetic component is an important contributing factor to open-bite malocclusion. Control of the vertical growth pattern by orthodontic means alone is difficult. However, changes in the dentoalveolar complex may directly affect the most representative skeletal features of an anterior open bite. For example, controlling the vertical eruption of the molars allows the mandible to rotate in a counterclockwise direction, reducing the excessive vertical skeletofacial pattern.

Treatment Strategies

As described in Chapter 1, treatment strategies should address the cause of the malocclusion. Environmental factors that contribute to a patient's malocclusion, such as thumb-sucking or finger-sucking, should be identified during the clinical examination and then eliminated. The treatment of excess in the vertical dimension often mimics that of the treatment of anterior open bite. The different approaches can be separated according to the age of the patient. In growing patients, the focus of the approach is controlling the eruption of the molars, thereby affecting the skeleton. The same focus will also be beneficial if the patient has an anterior open bite. In adults, the excess vertical length has traditionally been treated with surgery, especially if the hyperdivergent features are associated with a marked dentofacial deformity that affects esthetics. These features are maxillary excess, increased mandibular plane angle, excessive gingival display, retrognathic mandible, long lower facial height, and excessive interlabial gap. Recently, these patients have been treated by using temporary anchorage devices (TADs). However, this approach is most often attempted only when the vertical excess is associated with an anterior open bite.

Treatment of Thumb-Sucking or Finger-Sucking

Children often have a habit of sucking on a finger or a thumb. Many children stop this habit on their own; others need assistance. Children should be encouraged by their parents to stop the sucking habit before the age of 4 years. Before this age, most adverse dental and skeletal effects caused by the habit usually return to the original state, creating a favorable environment for the eruption of permanent teeth.42 Communication and positive reinforcement by the parents may help to modify any undesirable behaviors but unless a child is willing to stop the habit, these attempts may be unsuccessful.60

To help a child stop the habit, parents should note the time of the day at which the behavior occurs and then try to intervene. For example, if a child sucks a thumb or finger during sleep, mechanically obstructing the hand with a sleeping gown may be helpful.61 If initial attempts are unsuccessful, an intraoral appliance that acts as a mechanical obstruction and reminder can be used.

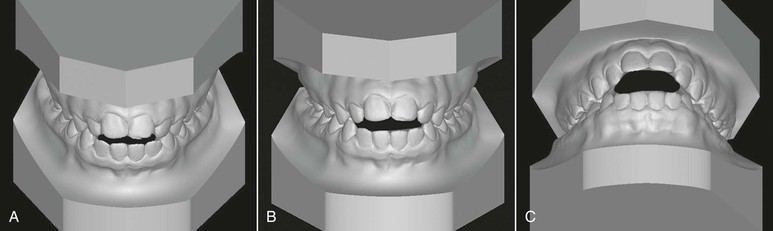

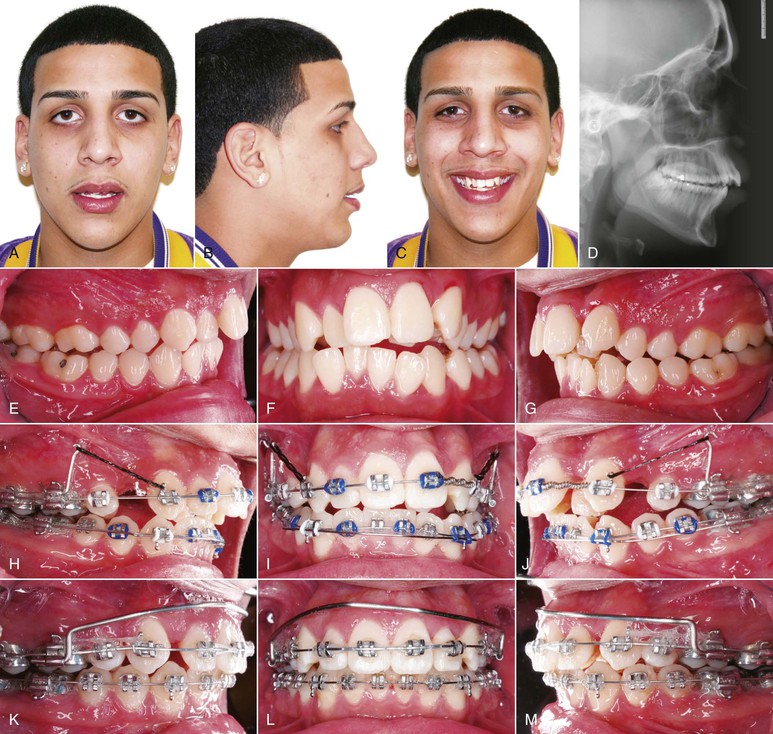

Different intraoral appliances are available for behavior modification. These appliances consist of a stiff archwire with a series of loops that sit closely to the anterior part of the palate and attach to two upper molar bands. The loops act as a mechanical obstruction and a reminder of the habit. Usually, after 3 months spontaneous correction of any dentoalveolar or eruption problem occurs without use of any other appliance (Fig. 9-8).

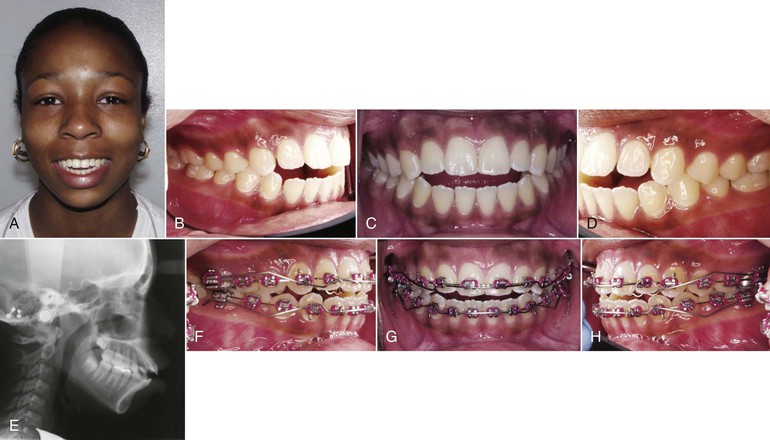

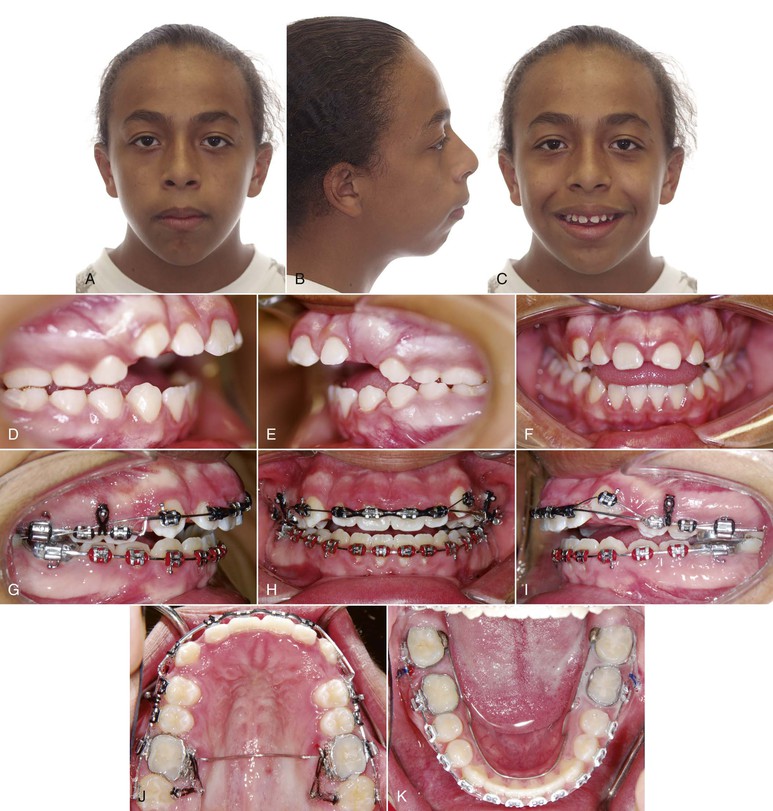

Figure 9-8 A–C, Patient with a finger-sucking habit resulting in an anterior open bite mesial to the first premolars. D, Lateral cephalogram showing characteristics of a dental open bite. E–H, Habit appliance with loops acting as a mechanical obstruction in close approximation to the anterior portion of the palate. I–K, Spontaneous correction of the anterior open bite after habit appliance delivery. L, Lateral cephalogram showing the open-bite closure. M, Superimposition reflecting the incisor extrusion that results with spontaneous closure of an anterior open bite with the habit appliance.

Treatment of Tongue Thrusting

Patients with tongue thrusting can be treated effectively in the same manner as that used for patients who suck on a thumb or finger (Fig. 9-9), although different appliances, such as the habit appliance with lingual spurs or cribs (Fig. 9-10), have been suggested. In one study,62 immediately after crib placement the tip of the tongue was positioned posteriorly during all stages of deglutition. Additionally, the anterior and middle parts of the dorsum of the tongue were at a lower position, reflecting a compensatory functional change for bolus propulsion and airway protection. However, no significant change occurred in the posterior part of the dorsum. Taslan et al.63 reported a decrease in resting tongue pressure and swallowing pressure from 21 g/cm2 to 13 g/cm2 and 216 g/cm2 to 143 g/cm2, respectively, after 10 months of tongue crib therapy in patients with anterior open bite. This decrease in tongue pressure at rest and swallowing pressure after crib therapy was suggestive of tongue adaptation in response to the altered environmental changes. This altered tongue posture aided in the correction of an anterior open bite through an increase in overbite of 3.6-mm. The increase in overbite was attained by lingual inclination of the maxillary and mandibular incisors by 4 degrees each and by extrusion of 1.4-mm and 1-mm, respectively.64

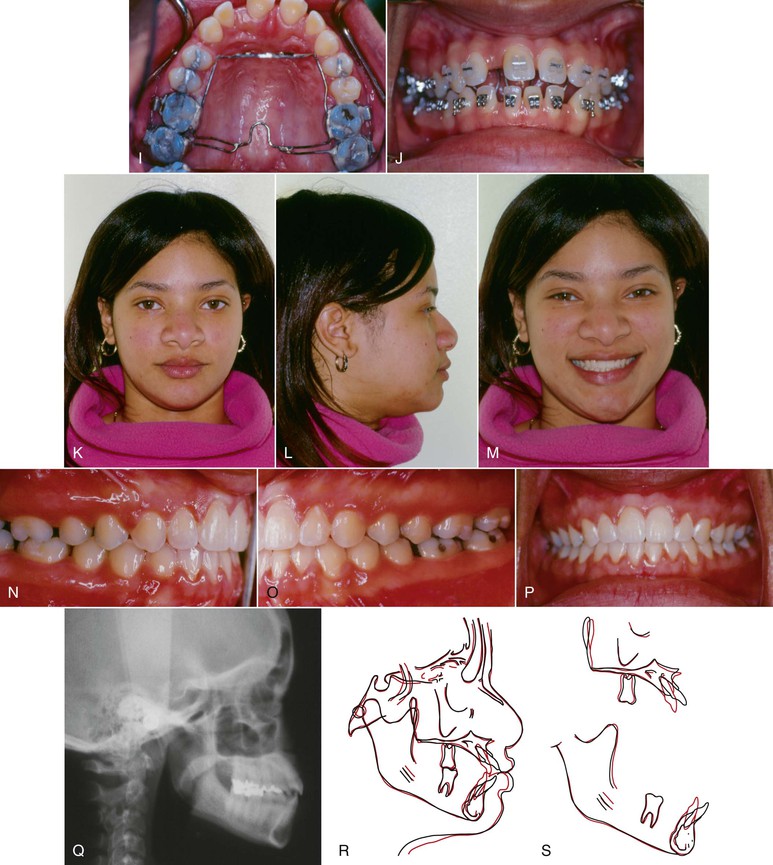

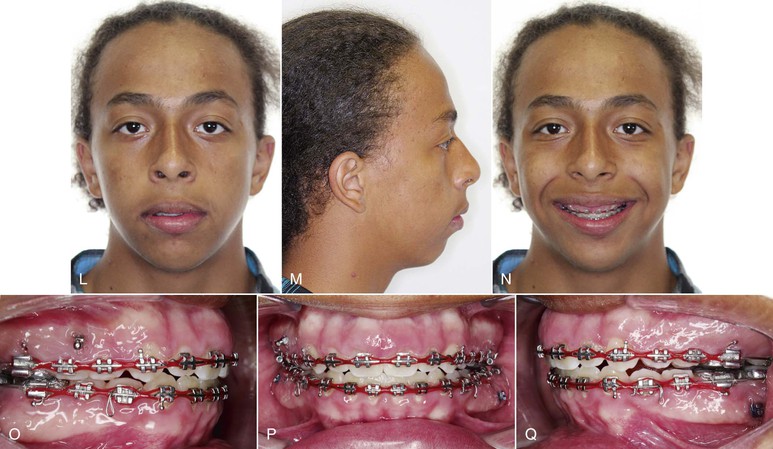

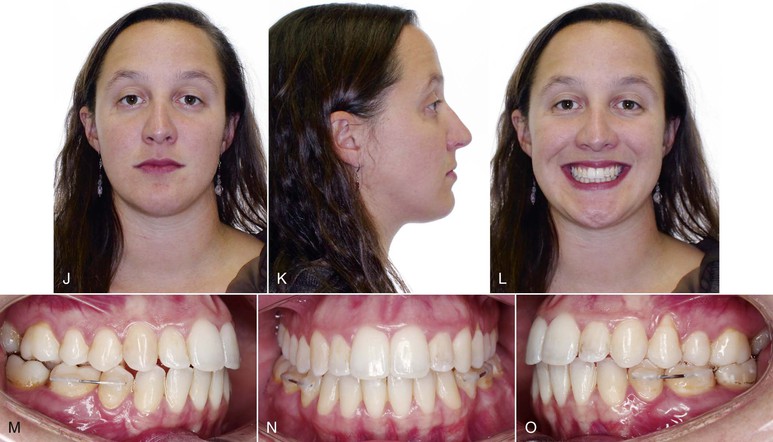

Figure 9-9 Female patient, age 18, with a tongue thrust. A–C, Extraoral views. On smile, only 50% of the incisors are displayed and an anterior tongue posture is evident. A reverse smile arc is consistent with the tongue thrusting habit. D–F, Intraoral views show a 3-mm anterior open bite with divergent occlusal planes from the first premolars. G, Lateral cephalogram shows a dental anterior open bite with dentoalveolar protrusion. H, Habit appliance with first and second molar bands and anterior loop design close to the palate. I, Intraoral view of the cemented habit appliance. J, Brackets are placed after 6 months of exclusive treatment with the habit appliance. Fifty percent of the negative open bite self-corrected. K–M, Extraoral views after treatment. A positive smile arc was obtained, with approximately 90% incisor show on smile. N–P, Adequate overbite was achieved with a good Class I relationship. Q, Final lateral cephalogram shows the overbite correction. R, General superimposition shows no maxillary or mandibular growth. Controlled lingual tipping of the upper and lower incisors reduced the dentoalveolar protrusion and anterior open bite. S, Regional maxillary and mandibular superimpositions show the same dental movements described previously (pre-treatment age, 18.8 years; post-treatment age, 21.5 years).

Other devices to retrain the tongue posture, known as myofunctional appliances, are also effective in treating tongue thrusts. Myofunctional therapy aids in muscle retraining by using a series of tongue exercises to correct the deleterious resting and functional postures65 and corrects the tendency for hyperdivergent growth. Types of functional appliances include the Frankel functional regulator, bionators, activators, and twin blocks.

In a longitudinal study,66 considerable decreases in mandibular plane angle, palatal plane to mandibular plane angle, and gonial angle occurred in a group of patients treated with functional regulators. Compared with findings in the control group, the ratio of the upper to the lower anterior facial height and the ratio of the anterior to the posterior facial height changed to normal values in the treatment group. Improvement in skeletal open bite was due to lengthening of the ramus and favorable compensatory growth at the condyles. The functional regulator did not remove the wedge by intruding the molars. The authors66 hypothesize that the forward rotation of the mandible is due to postural balance between the forward and backward rotating muscles brought about by lip seal exercises. Of note, the goal of most treatment strategies for patients with hyperdivergent facial patterns is to intrude the molars. On the contrary, correction with the functional regulator was primarily achieved by changing the existing deviant functional pattern of muscular environment.

Treatment of Macroglossia

If macroglossia is diagnosed, surgical resection may be performed to reduce the volume of the tongue. The open bite can then be corrected by retraction of the anterior teeth. After treatment, stability most likely will be enhanced, because the reduced tongue volume will better match the reduced arch length obtained after retraction of the incisors (Fig. 9-11). Although this procedure may help in the reduction and stability of anterior open-bite correction, the morbidity of the procedure, with potential sequelae in taste, sensation, and motor dysfunction, explains why this approach is not often chosen.45,67

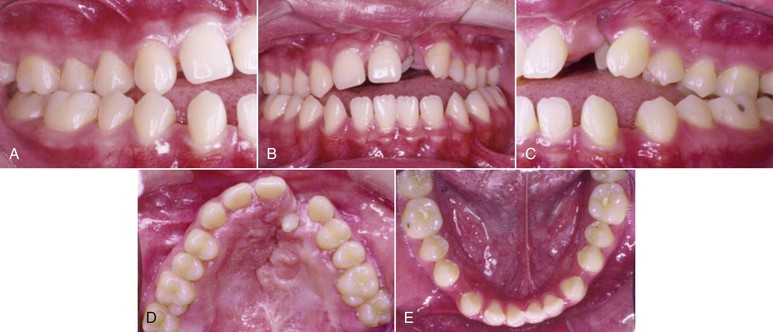

Figure 9-11 A–E, Intraoral views of a patient with a unilateral left cleft lip and palate. Significant spacing is observed in the lower arch due to a large tongue. F, Keyhole-design glossectomy. G–I, Lateral borders of the tongue to be approximated after tissue mass reduction. J, Anterior open-bite closure after surgical orthodontic treatment. K–M, Intraoral views illustrating 9-year stable result.

Treatment of Airway Obstruction

Procedures that promote better breathing through the nose (turbinate surgery, adenoid and tonsil removal, allergy treatment) may help to reestablish normal growth patterns.68 However, the growth direction of the mandible among patients varies greatly after any of these procedures.69 This variability makes the decision to intervene with a resective surgical procedure difficult. Therefore the diagnosis of upper airway obstruction and the decision for surgical intervention should always be made by an appropriate team of specialists.

Correction of Open Bite by Incisor Extrusion

Extrusion of the upper and lower incisors is a common orthodontic treatment for anterior open bites. This treatment is appropriate if the patient has an open bite with a normal skeletal pattern but may also be used in patients with vertical dysplasias who have deficient incisor display at rest and when they smile. However, most patients with long face morphology and anterior open bite have posterior as well as anterior vertical maxillary excess (Fig. 9-12). Thus correction of the malocclusion in these patients by extrusion of the upper incisors may result in an excessive display of the incisors and gingival tissues, compromising not only the esthetic results but also the long-term stability of the outcome. Nonetheless, the short-term occlusal results are usually satisfactory.

Figure 9-12 A, A Patient with posterior vertical maxillary excess and anterior open bite with slightly increased incisor display at smile. B, Correction of the anterior open bite by extrusion of the anterior teeth will accentuate the anterior vertical maxillary excess in detriment of facial esthetics.

Here the compliant and noncompliant are treatment methods. Vertical elastics are the most common method used for incisor extrusion in compliant patients. Extrusion arches are used in noncompliant patients.

Extrusion Arches

Extrusion arches are efficient tools used to correct upper and lower occlusal planes that diverge anterior to the first premolars. These archwires are indicated (1) when spontaneous correction of an anterior open bite does not occur after tongue crib therapy, (2) when a constant extrusive force is desired in the anterior teeth with minimal posterior side effects, and (3) in noncompliant patients who will not wear anterior vertical elastics.

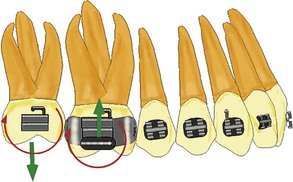

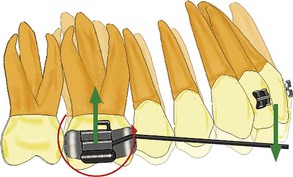

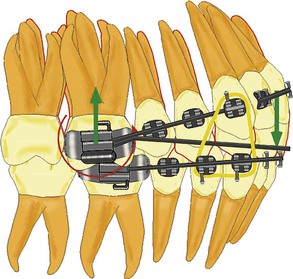

The extrusion arch is a one-couple force system (Fig. 9-13) that applies a single extrusive force to the anterior teeth and a tip-forward moment and intrusive force to the posterior segment. Often the tip-forward moment is undesirable.70 On the other hand, the intrusive force on the molar is favorable in patients with anterior open bites; however, the magnitude of this force, which is the same as the extrusive force on the anterior teeth, most likely would not result in molar intrusion.

Figure 9-13 Extrusion arch force system. A one-couple force system with an anterior extrusive and a posterior intrusive force. The couple on the molar produces a tip-forward moment.

Different options are available to negate the tip-forward side effect. First, a buccal stiff sectional wire from the upper first molar to the first premolar is added. Second, the magnitude of the extrusive force should be kept low (extrusion of the incisors requires light forces) to maintain the posterior moment at a minimal level. Finally, adding vertical elastics off the posterior segment to negate this tip-forward moment is helpful71 (Fig. 9-14).

Figure 9-14 Vertical elastic added to the upper buccal segment to negate the tip-forward tendency produced by the one-couple force system in the extrusion arch.

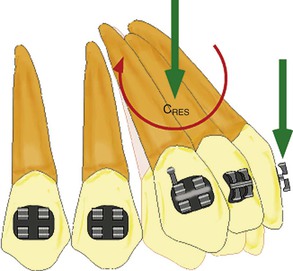

The extrusive force of an extrusion arch applied to divergent occlusal planes anterior to the premolars is favorable, especially if the upper incisors are flared. As this force is applied labially to the center of resistance (CRES) of the incisors, the moment of the force will produce an uprighting movement (crown lingual) (Fig. 9-15). Figure 9-16 shows a patient with anterior open bite that was corrected by using upper and lower extrusion arches.

Figure 9-15 Effects of the anterior force of the extrusion arch on the upper incisors. The applied force at the bracket will produce in the center of resistance (CRES) of the incisors a clockwise moment plus an extrusive force of equal magnitude.

Figure 9-16 Treatment of a patient with extrusion arches on the upper and lower dentition. A, Frontal view on smile showing approximately 90% of incisor display. B–D, Preoperative intraoral photos showing a 3-mm anterior open bite and occlusal plane diverging anteriorly from the first premolars. E, Lateral cephalogram showing undererupted maxillary incisors. F–H, Upper extrusion arch with buccal segments to prevent molar tip forward. Lower extrusion arch tied to the lateral incisors with a continuous nickel-titanium (Ni-Ti) 0.016-inch wire. I–K, Good anterior open-bite correction with maintenance of the vertical relationship on the buccal segments. L–O, Final records showing the improved smile arc and good occlusion with positive overbite.

In some instances, lingual tipping of the incisors is undesirable. Instead, a translatory extrusion type of movement is the goal. The same mechanics can be applied (one-couple force system); however, the force on the anterior segment is placed close to the canine in an anteroposterior direction by means of a three-piece extrusion arch (Fig. 9-17).

Figure 9-17 Three-piece extrusion arch. A–C, Intraoral records showing an anterior open bite with upright incisors. D–F, Three-piece extrusion arch delivered to extrude the incisors and slightly correct the incisor inclination by delivering a force posterior to the center of resistance. G-I, Incisor extrusion evident by referencing the movement to the adjacent canines. J-L, Intraoral final records showing good buccal occlusion, adequate overbite, and good incisor maxillary inclination.

Vertical Elastics

Traditionally, vertical elastics have been used for closure of an open bite. Inter-arch mechanics with vertical elastics are indicated in patients with anterior open bites in which the occlusal planes diverge anteriorly. Vertical elastics from the lower incisors to the upper incisors result in a consistent force system of equal and opposite forces (Fig. 9-18). Reduction of the overbite by extrusion of the incisors is the result.

Figure 9-18 Force system of anterior vertical elastics (equal and opposite forces), which is favorable in anterior open bite with divergent occlusal planes anterior to the first premolars and reduced incisor display.

Although vertical elastics are a common method for incisor extrusion, certain problems are inherent with this type of treatment. First, response varies greatly among patients because of poor control of the force magnitude and degrees in compliance. Second, specific goals defined in the treatment plan (occlusal plane, position of incisors) cannot be achieved predictably because good mechanical control is difficult to achieve with indiscriminate use of elastics.

Multiloop Edgewise Archwire

The appliance known as the multiloop edgewise archwire (MEAW) relies on a combination of compliant and noncompliant mechanics in which archwires with specific shapes in conjunction with vertical elastics are used to correct an anterior open bite. Most of the reduction in the overbite is achieved by extrusion of the anterior teeth with negligible molar intrusion.72 Additionally, the inter-molar angle is partially corrected, a change that may aid in stability after treatment.

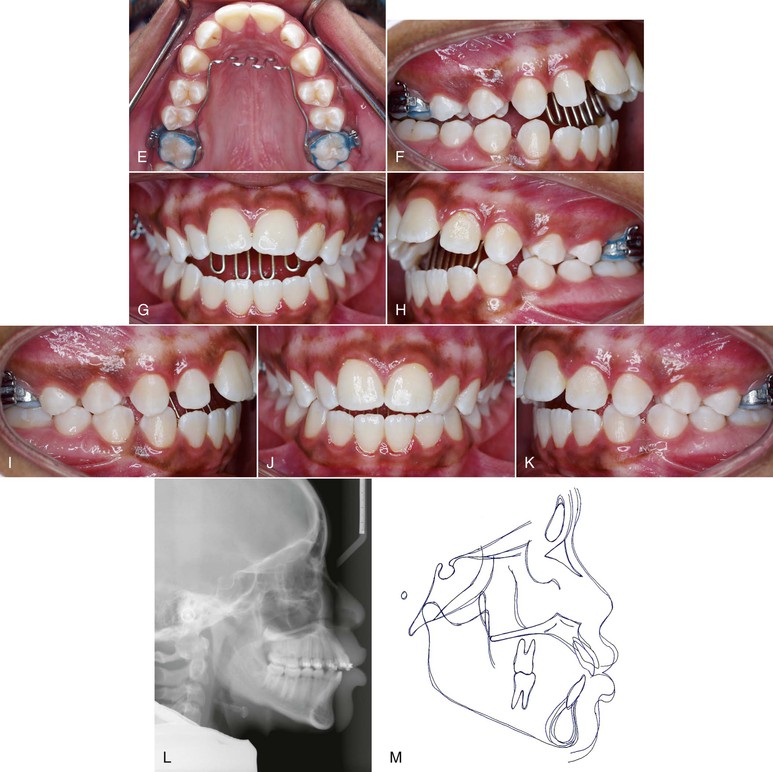

Treatment in Growing Patients

The prevalence of open bite is two to three times higher in children than in adults.73 Spontaneous correction of the malocclusion occurs in more than two-thirds of patients during the mixed dentition period.74 Early treatment options are available for open bites that do not self-correct.7 However, managing skeletal open-bite malocclusions and the long-term stability of the outcome depend on the orthodontist's ability to address the cause and to alleviate the 3D problems in skeletal, dental, and soft tissues. The primary aim is to inhibit the vertical development or intrusion of buccal dentoalveolar segments and to aid in favorable forward and upward rotation of the mandible. Various methods have been used to manage hyperdivergent facial patterns in growing patients: habit-breaking appliances, functional appliances, headgear, posterior bite blocks, vertical-pull chin cups, and clenching exercises.

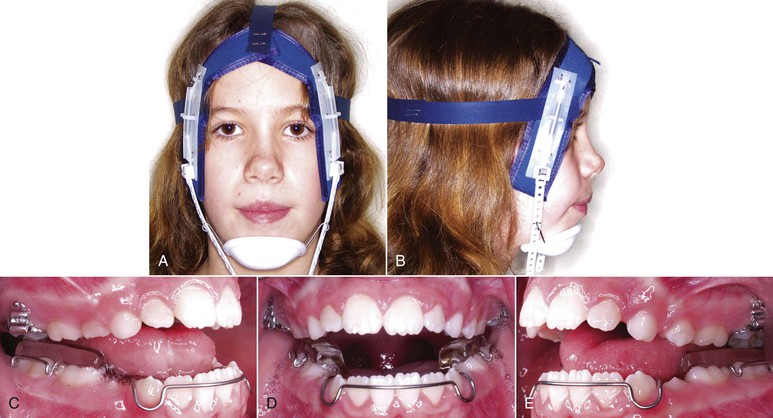

Headgear

Extraoral maxillary traction appliances are commonly used to control the vertical dimension. Occipital and vertical-pull headgears have an intrusive force on the maxillary molars. In addition to the intrusive component of force, occipital headgears also have a distal force. This force system is ideal in patients with a Class II hyperdivergent growth pattern. However, evidence indicates little therapeutic benefit from use of a high-pull headgear, because an increase in the angle of the mandibular plane can occur.75 Although control of the eruption of maxillary molars is effective, compensatory overeruption of the mandibular molars often occurs as well.76

Orthodontists generally avoid using cervical-pull headgear in patients with hyperdivergent facial patterns because molar extrusion can occur, leading to clockwise rotation of the mandible. However, contrary to this popular notion, clockwise rotation of the mandible does not always occur.77,78 Haralabakis et al.79 found counterclockwise rotation of the mandible in high angle patients treated with cervical headgear. Additionally, in another study80 changes in vertical dimension in dolicofacial patients did not differ significantly between patients treated with cervical headgear and those treated with occipital headgear.

Posterior Bite Blocks

Passive acrylic bite blocks are functional appliances that open the mandible beyond the interocclusal distance by 3- to 4-mm and maintain the pressure applied by the masticatory muscles on the posterior teeth.81 On the other hand, spring-loaded bite blocks82 and magnetic bite blocks (active vertical correctors)83 provide continuous vertical force on the occlusal surfaces of posterior teeth within the neuromuscular system. In experimental studies84 in animals, an alteration in vertical dimension led to structural adaptations in the craniofacial complex. Although these appliances were effective in reducing the vertical dimension in growing patients, absolute intrusion of posterior teeth was minimal (0.5-mm).82

Vertical-Pull Chin Cup

Vertical-pull chin cups (VPCCs) have been used to control the increase in anterior facial height during the time of mixed and early permanent dentition.85–87 VPCCs have been used in conjunction with fixed appliances, functional appliances, posterior bite blocks, and removable appliances (Fig. 9-19). The magnitude of force applied is 400 g per side and, according to recommendations, the VPCC should be worn up to 12 hours per day. The direction of the force is through the anterior and inferior region of the mandibular corpus and 3 cm from the outer canthus of the eye. Iscan et al.88 reported that skeletal and dental open bites were successfully corrected by upward and forward rotation of the mandible, significant eruption of the mandibular incisors, and inhibition of eruption in the mandibular posterior dentoalveolar region.

Masticatory Muscle Exercises

Isometric masticatory muscle exercise has been recommended as an adjunctive to orthodontic treatment89,90 or alone in patients with hyperdivergent facial patterns. Isometric clenching exercises increase the contractile forces of the elevator muscles of the mandible. Masticatory exercises can produce favorable skeletal and occlusal changes in growing children. Significant reductions in anterior facial height, gonial angle, and counterclockwise rotation of the mandible have been reported.91,92 Clenching exercises on a soft bite block93,94 and chewing exercises with a hard gum91,95 or tough pine tree resin92 are the common methods of masticatory muscle exercises. A minimum of 45 to 150 minutes per day for 12 to 30 months of exercise appears to be necessary to produce clinically significant morphological changes in the dentofacial complex.89

Transpalatal Arch

The tongue affects the dentoalveolar complex during mastication, swallowing, and speech and at rest. Harnessing the forces generated by the musculature of the tongue on the palatal arch during swallowing can prevent the vertical development of the maxillary molars.96 During deglutition, mean tongue pressure ranges from 37 to 709 g/cm2.97 Chiba et al.97 measured the tongue pressure exerted on the palatal bar by altering the anteroposterior and vertical position of the transpalatal arch. Increased levels of pressure were recorded when the loop of palatal arch was 6-mm from the roof of the palate and anteroposteriorly between the second molars. DeBerardinis et al.96 retrospectively analyzed the vertical holding appliance, which is a transpalatal arch with an acrylic pad. Compared with control subjects, for the duration of treatment patients with the appliance had eruption of the maxillary molars restrained by 0.41-mm.

Treatment in Nongrowing Patients

Management of adult patients with vertical maxillary excess and excessive vertical dimension has been addressed primarily through orthognathic surgery.98 Surgical procedures to address long face patients have been associated with acceptable treatment outcomes and long-term stability.99,100 However, the introduction of skeletal anchorage devices has been a major shift in orthodontics, enabling predictable, effective, and efficient tooth movements with direct occlusal and skeletal benefit to long face patients.101,102 The molars can be intruded directly from TADs to correct the vertical dimension without the need for compliance by the patient.103–105

A major advantage of molar intrusion with TADs is the favorable skeletal changes that enhance a patient's dentofacial esthetics (Fig. 9-20). With conventional orthodontics in patients with anterior open bite, closure of the overbite is achieved mainly through dentoalveolar changes; however, the skeletofacial complex may worsen because of extrusive mechanics. On the other hand, TADs target the intrusion of the posterior segment, which is often the cause of the increased vertical dimension.

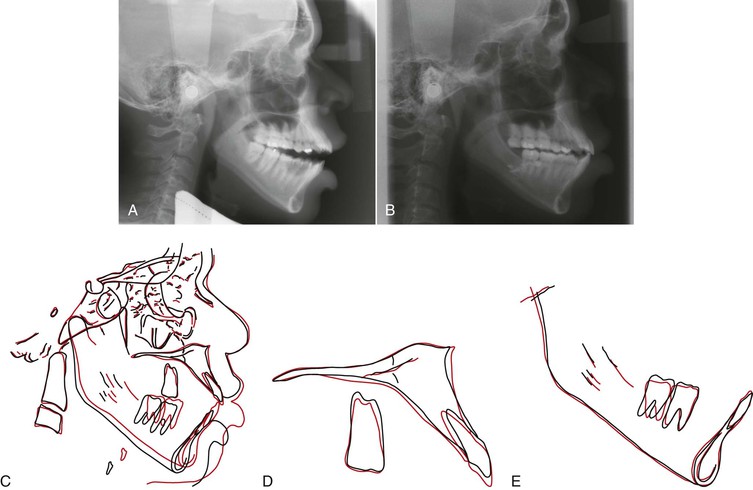

Figure 9-20 Adult patient with a moderate skeletal anterior open bite treated with temporary anchorage devices (TADs). A–C, Extraoral views show increased lower facial height and adequate incisor display at smile. D–F, Anterior open bite with occlusal planes that diverge anteriorly from the second molars. G–I, Four TADs (two in the infrazygomatic crest and two in the external oblique ridge) were placed to assist in the intrusion of the first and second molars. J–L, Final extraoral views showing good esthetic result, including maintenance of the incisor display upon smiling. M-O, Final intraoral views depicting anterior open-bite closure. Note that the mandibular right second molar was intentionally overintruded to leave adequate space for a restoration since this tooth had significant occlusal wear through dentin with the pre-treatment occlusion. P-R, General and regional superimpositions show molar intrusion and vertical maxillary incisor control.

The suggested magnitude of force for molar intrusion is about 50 to 200 g per tooth. For en masse intrusion of premolars and molars, a force of approximately 200 to 400 g has been suggested. The rate of intrusion of a single maxillary molar is 0.75-mm per month, whereas the rate for en masse intrusion of a posterior segment is 0.5-mm per month. Usual time for intrusion of maxillary molars is 5 to 7 months for a mean intrusion of 2- to 4-mm.106 Sugawara et al.107 reported mean intrusions of 1.7-mm and 2.8-mm for mandibular first molars and second molars, respectively, when mini-plates were used.

Molar intrusion can be accomplished with different types of TADs. However, before anchorage devices are placed, defining the desired tooth movement in three dimensions of space is important. The line of force for molar intrusion determines the number of mini-implants, buccal or palatal placement, direct anchorage or indirect anchorage, and anatomic location of TAD placement. Locating the center of resistance (CRES) of the active unit is important to produce a force system designed for intended tooth movement. According to holographic studies,108 the CRES of upper dentition is located near the key ridge. However, according to a finite element study,109 the CRES of maxillary dentition is 11-mm from the tip of the cusp of the second premolar.

In another finite element study, Çifter and Saraç110 evaluated three methods of using mini-implants for intrusion of segmental maxillary posterior teeth. Balanced intrusion with minimal buccal tipping occurred when buccal and palatal forces were applied simultaneously via mini-screws. In other models with one or two transpalatal arches and a buccal line of force application via mini-screws, vestibular tipping was greater. Mesiodistal cant also occurred in a model in which one palatal arch was modeled along with application of one-point buccal intrusive force. To minimize the bowing effect vertically, Çifter and Saraç110 recommend establishing uniform stress distribution along the posterior segments by using separate force applications and differential force levels for the molar and premolar sites. Furthermore, because of the dynamic nature of biomechanical force systems after the initial tooth movement, appropriate changes in the magnitude and direction of force are necessary during treatment to prevent side effects in second and third order.

Buschang et al.103 intruded the maxillary and/or maintained the mandibular posterior teeth in a controlled manner by using two mini-screws palatally in the parasagittal region mesial to the first molar in the upper arch and two mini-screws in the lower arch between the second premolar and the first molar. Maxillary molars and premolars were rigidly held by a rapid palatal expander. A lower lingual arch was used along with a 0.016-inch × 0.022-inch stainless steel archwire. The primary advantage of this approach was that during the intrusion of maxillary posterior teeth, mandibular molars were either intruded or maintained, thereby preventing them from compensatory eruption in response to the intrusion of maxillary molars. Forward rotation of the mandible, increase in chin projection, decrease in lower anterior facial height, and decrease in mandibular plane angle were all favorable outcomes. These outcomes can be achieved in patients with hyperdivergent facial patterns by clockwise rotation of the maxillary occlusal plane and counterclockwise rotation of the mandibular occlusal plane.

Figure 9-21 shows the management of an adolescent with Class II skeletal open-bite malocclusion with intrusion of maxillary and mandibular posterior teeth. He had an anterior open bite of 8-mm, a large interlabial gap of 9-mm, two different occlusal planes, a retrusive chin, and mentalis strain with an adequate incisor display when he smiled. The treatment plan was to intrude the maxillary posterior teeth by 3- to 4-mm and the mandibular posterior teeth by 1-mm by using skeletal anchorage devices. Mini-screws were placed palatally, mesial to the upper second molar, and between the premolars buccally. Additionally, two mini-implants were placed mesial to the mandibular second molars. To increase the rigidity of the segments, transpalatal and lingual arches were fabricated. Positive overbite with a leveled maxillary occlusal plane, increased chin projection, improvement in soft tissue profile, decrease in lower anterior facial height, and interlabial gap with improvement in mentalis strain were achieved.

Figure 9-21 A–C, Growing patient with a significant skeletal and dental anterior open bite. Poor mandibular projection and mentalis strain upon lip closure were observed. D–F, Anterior open bite with divergent occlusal planes anterior to the first premolars. Class II occlusion noticed bilaterally. G–K, Four mini-screws were placed in the maxilla (two in the palate and two interdentally between the premolars) to intrude the buccal segments. L–N, Progress showing improved lip seal and intrusion of the buccal segments with maintenance of the incisor display at smile. O–Q, Two mini-screws were added to the mandible between the first and second molars bilaterally to prevent supraeruption of the lower molars. Good overbite observed with a Class I occlusion after posterior intrusion in this growing patient.

Orthognathic Surgery

A segmental Le Fort I osteotomy is routinely performed to reduce the vertical maxillary excess in patients with two maxillary occlusal planes and a transverse deficiency. This procedure allows superior positioning and expansion of the maxilla (Fig. 9-22). At the same time, the occlusal plane is leveled. In one study, three degrees of forward autorotation of the mandible was achieved when the maxilla was impacted 1.3-mm posteriorly and 3-mm anteriorly.111 The autorotation increased the sella-nasion B point (SNB) angle, decreased the anterior facial height, and decreased the angle of facial divergence (mandible plane angle) with minor forward movement of the pogonion. In addition to a Le Fort I osteotomy, mandibular surgery may be performed to correct any associated mandibular deformity.

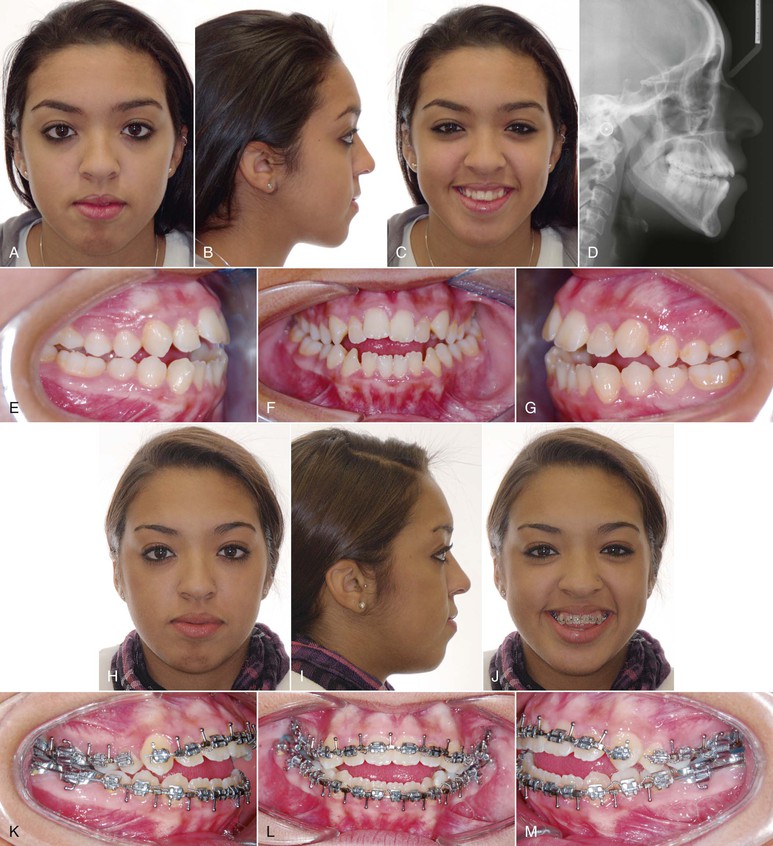

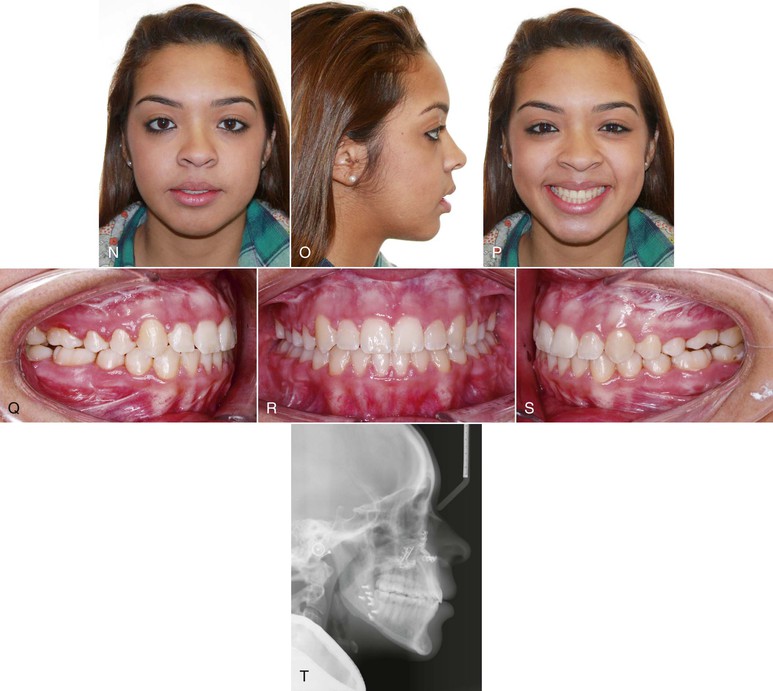

Figure 9-22 A–D, Patient with skeletal open-bite characteristics. E–G, Anterior open bite with diverging occlusal planes from the first premolar and bilateral posterior crossbite. H–M, Presurgical extraoral and intraoral views after segmental leveling for a three-piece maxilla Le Fort I osteotomy. N–T, Final records after maxillary impaction with expansion and mandibular setback. Improved facial and smile esthetics and correction of the anterior open bite.

The timing of surgical intervention is critical in a young adolescent because the subsequent effects of orthognathic surgery on the dentofacial complex are poorly understood and controversial. Washburn et al.112 evaluated surgical superior repositioning of the maxilla in 16 growing individuals. Stable dental, skeletal, and esthetic results were still apparent after 3 years of follow-up. The authors suggest that early surgical intervention may have a favorable effect on excessive growth in patients with vertical maxillary excess. Nanda et al.113 had similar results in studies in animals. Mojdehi et al.111 and Mogavero et al.114 retrospectively assessed growth changes in the maxilla and mandible after Le Fort I osteotomy. Early surgery did not normalize or inhibit the vertical pattern of growth and the growth after surgery was comparable to growth in an untreated control sample. In a consensus conference115 on the timing of facial osteotomies, the participants recommended that most of the surgical procedures be done after completion of growth. Early surgical intervention can be an exception to the rule for psychosocial reasons,115 especially for patients with problems in the vertical dimension, but the patients and their parents must be informed that additional surgery may be necessary later.114

Extractions for Open-Bite Closure

Different types of extraction patterns have been suggested to correct anterior open bites, including extracting the second molars, extracting the first molars, extracting the second premolars, and extracting the first premolars.116 The extraction pattern is individually tailored to the patient to extrude the anterior segment, move the posterior teeth anteriorly (wedge effect),15,117 or achieve a combination of the two.

Second Molar Extractions

The extraction of second molars has been suggested as a practical option in patients who have an anterior open bite with contact solely on these teeth and divergent occlusal planes (wedge effect; Fig. 9-23).15 Although this option is feasible, the magnitude of divergence of the occlusal plane is the limiting factor to full overbite correction. A potential problem, depending on the age of the patient, is the necessary continual monitoring of the third molars until full eruption and correct positioning in the arch are achieved.118 However, this method provides an advantage over the other extraction patterns because no space closure is needed and vertical forces are not likely to be generated (see Premolar Extractions later in this chapter). Interestingly, patients with this anterior open-bite pattern (divergent occlusal planes with only the second molars contacting) are generally considered surgical patients.

Figure 9-23 Anterior open bite with occlusal planes diverging from the second molars anteriorly. All second molars are extracted for correction of the open bite. The magnitude of the open-bite correction is dependent on the angle of divergence of the upper and lower occlusal planes. Full correction of the anterior open bite may not be obtained in extremely divergent occlusal planes.

First Molar Extractions

Typically, first molars are extracted only if they are compromised by extensive decay. In theory, this treatment alternative should contribute to closure of an anterior open bite, and in one study119 this extraction pattern maintained or slightly reduced the vertical skeletal relationships. However, in most patients the second molar replaces the first molar and the anterior open bite is not resolved. As the molar is protracted into the extraction space, extrusion of the distal aspect usually occurs because of poor mechanics, thereby increasing or maintaining the anterior open bite. Overall, if this extraction option is considered, space closure mechanics are the deciding factor in the success of the overbite correction.117,120

This treatment alternative is most effective if proper timing is considered. If the second molars have not erupted and if the only contact is between the first molars, extraction of the first molars would eliminate the increased vertical height and the second molars could not erupt beyond the newly established vertical height.

Premolar Extractions

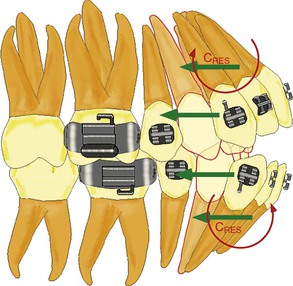

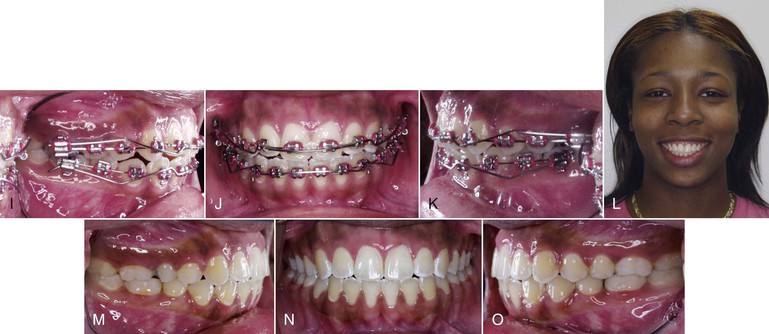

Extractions of the first or second premolars are the most commonly considered alternatives for the treatment of anterior open bites associated with crowding and/or overjet. Deciding which premolars to extract depends on the amount of incisor retraction. In patients who have premolars extracted, extrusion of the anterior segment rather than the wedge effect aids in closing the open bite. This treatment alternative works well in patients with occlusal planes that diverge anteriorly from the first or second premolars. The mechanics are easier when the anterior teeth are flared (the usual situation in this type of divergence of the occlusal plane).121 A single distal force (ideally controlled tipping) will produce lingual tipping of the incisor crowns. Because the center of rotation (Crot) is close to the apex, the net effect is extrusion and retraction of the incisors to close the bite (Fig. 9-24).

Biomechanics of Space Closure in Open Bites

Although the biomechanics of space closure is discussed more fully in Chapter 6, specific aspects that pertain to anterior open bite are reviewed here.

Group A Space Closure Mechanics

Group A space closure is the most difficult to perform in patients with an anterior open bite if non-TAD-supported intraoral anchorage is desired. The use of differential moments to maintain anchorage in the force system results in a large moment and an extrusive force posteriorly. Anteriorly, a smaller moment and an intrusive force are generated. This force system is highly undesirable in patients with an open bite.122 Figure 9-25 shows how the vertical forces are antagonistic with group A space closure. An alternative would be to use a one-couple system (intrusion arch) in which a couple is created at the level of the molar and an additional base archwire (0.018-inch stainless steel) is placed for canine sliding mechanics. The base arch would minimize the intrusive force in the anterior teeth and the moment from the intrusion arch would contribute to anchorage in the posterior end.

Figure 9-25 Differential moment force system in group A space closure is unfavorable for anterior open-bite correction. Vertical forces tend to accentuate the open bite.

Another alternative is the extension of a rigid power arm from the band of the molar gingivally to its center of resistance (CRES). From this arm a force is extended incisally to the canine. The same base archwire (0.018-inch stainless steel) as that just described for the intrusion arch mechanics can be used (Fig. 9-26). The effect would be differential tooth movement; the molar will bodily translate (more difficult tooth movement to achieve therefore it enhances anchorage) with the application of the force at the CRES and the canine will tip (easier type of tooth movement). Although the mechanics of this method have positive effects on anchorage, the vector of the force has a slight negative extrusive component on the molar and a slight intrusive component on the canine.

Figure 9-26 Alternative mechanics for Group A space closure. A–G, Initial records of a patient with a mild anterior open bite and a full cusp molar Class II occlusion. H–J, Retraction force extended from power arms in the maxillary first molars (promotes translation) to the crown of the canines (promotes tipping), resulting in differential anchorage. K–M, Progress showing canine retraction to Class I with minimal anchorage loss. Large-dimension labial bar from molar to molar was placed temporarily after the patient lost the transpalatal arch.

Perhaps the best approach in space closure when group A anchorage is needed is the use of skeletal anchorage. The mini-screw or mini-plate can be used not only to prevent loss of molar anchorage but also to achieve intrusion of the posterior teeth if required.

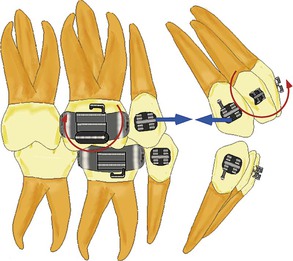

Group B Space Closure Mechanics

Mechanically, Group B space closure is the simplest.123 No vertical forces are generated and only two equal and opposite moments are needed (Fig. 9-27). Careful monitoring is essential to ensure that equal moment to force ratios are delivered to the anterior and posterior segments. If a high magnitude of force in relation to the moment is delivered in the posterior end, excessive crown tipping will result, extruding the distal cusps of the molar and possibly increasing the open bite.

Group C Space Closure Mechanics

Group C space closure mechanics are the most favorable for correction of an anterior open bite. Intraoral anchorage by means of differential moments yields a consistent force system. Figure 9-28 shows a larger moment in the anterior segment and an extrusive force that will maintain the anteroposterior position of the incisor. A smaller moment in the posterior area and an intrusive force will allow this segment to tip as a mesial force is applied. The vertical forces will aid in closure of the anterior open bite.

Figure 9-28 Mechanics for Group C space closure are the most favorable for open-bite correction. Vertical forces are consistent with the open-bite correction in the anterior (extrusive) and posterior (intrusive) segments.

Temporary anchorage devices such as mini-screws are also greatly indicated in this anchorage situation. Because the posterior teeth are protracted (if direct anchorage is used), the force vector has an intrusive component on these teeth that is beneficial to correction of the open bite.

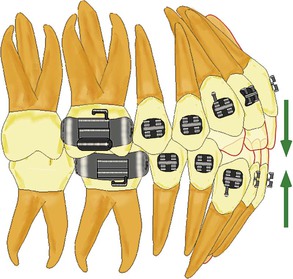

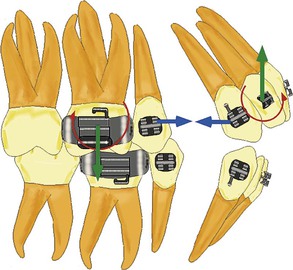

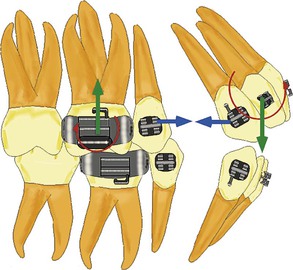

Bonding Second Molars

Traditionally, orthodontists have thought that bonding the second molars in a patient with an open bite most likely would result in an increased open bite.124 The reason for this is that as the second molar is incorporated into the arch, it is usually more gingival than the first molar in the upper arch and more occlusal in the lower arch (curve of Spee). When a straight wire is placed, a step geometry is generated, causing the lower first molar to supraerupt. Although the second molar experiences an intrusive force, intrusion seldom occurs, probably because of the magnitude of the force, which is lower than the threshold needed for intrusion. Additionally, a tip-forward moment is generated in the anterior segment that can open the bite (Fig. 9-29). In the upper arch the effect is extrusion of the second molar. If this extrusive force is not negated by the muscle forces, the mandible will rotate downward and backward (aggravating the open bite). The anterior moment generated is favorable for closure of the open bite but may be unfavorable for the esthetic objective, because the visibility of the incisor (incisor display) when the patient smiles will increase (Fig. 9-30). In summary, if alignment of the second molar is needed, care must be taken to engage the second molar passively in the second order.124

Esthetics and Open Bite

The three major esthetic factors to consider when planning the correction of an open bite are the incisor display, the occlusal plane, and the interlabial gap. In patients with anteriorly divergent occlusal planes, deciding which occlusal plane to treat is important.125 Depending on the decision, the treatment will be either orthodontics or a combination of surgery and orthodontics.

The functional occlusal plane in a patient with an open bite with two divergent occlusal planes anterior to the premolars is the limiting factor to the amount of correction that can be obtained with orthodontics. This functional occlusal plane dictates the position of the upper incisors within a 1- to 2-mm range vertically. The incisors must be erupted to this level to achieve a positive overbite. If the amount of incisor display at rest and during smiling is reduced, extrusion of the upper incisors is maintained until an acceptable level of display is achieved. Correction of the remaining amount of overbite can be achieved by extruding the lower incisors. In some instances this extrusion will accentuate the lower curve of Spee in an effort to obtain a positive overbite yet avoid excessive extrusion of the upper incisors.

To achieve additional vertical correction of the anterior segments, the functional occlusal plane must be modified by using either a clockwise (steepening) or a counterclockwise movement. Steepening the occlusal plane can be somewhat easily achieved, although it is rarely desired. The reverse movement (counterclockwise rotation) is often indicated in skeletal open bites (Fig. 9-31) but unfortunately it can rarely be achieved by orthodontic means only. The long face patient with adequate or excessive gingival display and an anterior open bite is a good example of a patient for whom a counterclockwise rotation of the mandibular occlusal plane is recommended (Fig. 9-32). In this type of patient the upper incisors should be maintained or intruded and the upper occlusal plane should be either intruded or rotated in a clockwise direction.

Figure 9-31 A, Pretreatment lateral cephalogram. B, Posttreatment lateral cephalogram. C-E, Superimposition showing counterclockwise rotation of the lower occlusal plane by intruding the lower molars via use of skeletal anchorage only in the lower arch. The net result is anterior open-bite reduction with mandibular autorotation.

Figure 9-32 A–F, Lateral and anterior open bite in an adult patient with congenitally missing second premolars. G–I, Treatment plan included closure of the remnant space after extraction of the deciduous second molars and four mini-screws to intrude the posterior segments. J–O, Final records show improved smile esthetics without increasing the incisor display at smile. Gingival display of the maxillary buccal segments was reduced and a good smile arc was obtained. Adequate overbite and buccal occlusion were achieved.

Treatment planning for a patient with divergent occlusal planes from molar to molar requires careful consideration of the esthetics and the occlusion. A treatment occlusal plane must be selected between the upper plane, the lower plane, or an intermediate plane of occlusion. Generally, the upper plane, or a constructed plane bisecting the upper and lower occlusal planes, is considered. The lower occlusal plane is seldom used because doing so usually results in excessive incisor display and considerable extrusion of the upper buccal segments.

The upper occlusal plane is selected if the vertical relationship at the incisor (incisor display) and molar level is good. A surgical procedure is needed to rotate the mandible in a counterclockwise direction to match the upper plane. Because of the long-term instability of this surgical movement, a two-jaw surgery is usually done. The maxilla is impacted posteriorly with a center of rotation around the upper incisal edge. Some autorotation of the mandible follows and a minimal additional surgical counterclockwise rotation is performed to correct the anterior open bite. These movements can also be achieved to a lesser degree by using skeletal anchorage and orthodontics for molar intrusion.

The final major aspect related to esthetics in patients with an open bite is the interlabial gap. Excessive interlabial gap is one of the most notorious soft tissue characteristics of patients with skeletal open bites. This problem can be addressed in two ways. First, the interlabial gap can be reduced by retracting the upper and lower incisors, although the magnitude of the vertical lip change in response to the incisor retraction can be unpredictable. The other alternative is to reduce the posterior facial height.

During growth, the posterior facial height can be decreased by the methods described earlier that control the dentoalveolar molar eruption. Once growth ceases, the interlabial gap can be reduced by using molar intrusion (via maxillary impaction with mandibular autorotation or implants) or sliding genioplasty. Sliding genioplasty provides an additional advantage in patients with vertical dysplasia. The procedure not only reduces the anterior vertical height but also allows a more anterior positioning of the chin (limited invasive surgical procedure with good esthetic result) (see Chapter 21).

Finally, of note, the interlabial gap per se is not an indication of vertical skeletal dysplasia. Evaluating the length and characteristics of the lips is important because lip lengthening procedures can be used to reduce the interlabial gap in patients who do not have vertical skeletal excess.126

Stability and Retention

The management and retention of the obtained results brought about by treatment of the malocclusion in the vertical dimension are challenging because the etiology is multifactorial, involving hereditary, skeletal, dental, respiratory, and habitual factors.127 The stability of treatment in growing and nongrowing patients with hyperdivergent facial patterns depends on the clinician's ability to address the cause of the malocclusion. Elimination of habits, weak musculature, and respiratory obstructions might decrease the rate and severity of relapse. Various protocols have been used, with a 67% to 100% success rate, in the early management of patients with hyperdivergent facial patterns.128 Although these appliances have been effective in correcting the skeletal open bite in growing patients, long-term follow-up studies are lacking. Because the hyperdivergent growth pattern is established early and subsequently maintained until adulthood, only long-term clinical studies will help in precisely understanding the consequences of early treatment in the growth of these patients.129

In a 10-year follow-up130 of patients with anterior open bite who were treated orthodontically, 35% of treated patients had a relapse of 3-mm or more. The relapse group had deficient mandibular anterior dental height, deficient upper anterior facial height, increased lower anterior facial height, and deficient posterior facial height. However, the amount of open bite, the angle of facial divergence (mandibular plane angle), and other parameters before treatment were not found to be valid predictors for post-treatment relapse. In one study131 the long-term stability of the corrected open bite was greater in patients treated with extraction than in patients who did not have extraction. However, the open bite was not the reason for extraction in these patients. Among the extraction group, 74% of the patients had a stable open-bite correction 8 years after treatment.132

Analysis of various long-term studies indicates that orthognathic surgery is an effective method for the management of anterior open bite. Superior repositioning of maxilla by one-piece Le Fort I osteotomy is considered one of the most stable procedures in the hierarchy of stability. Whenever indicated, even the three-piece Le Fort I osteotomy is a stable procedure.133 According to a meta-analysis,127 correction of an open bite via surgery is prone to some amount of relapse, although the long-term stability was greater than 75%. Possible reasons for postoperative relapse are preoperative orthodontic treatment, type of surgery, type of surgical fixation, condylar positioning during bimaxillary surgery, growth after surgery, and finally the soft tissue adaptation.134 Moderate skeletal changes after surgery are common in the long-term; however, minimal effects in the overbite are due to compensatory eruption of the incisors.134

The introduction of TADs has enabled orthodontists to intrude the maxillary and mandibular molars, correcting the anterior open bite nonsurgically and obtaining adequate long-term stability (Fig. 9-33). Lee and Park,135 who used mini-screws to intrude maxillary molars, reported a 10.36% relapse rate for the intruded molars and an 18% relapse of overbite after 18 months in retention. Sugawara et al.107 reported a 30% relapse rate after intrusion of mandibular molars 12 months after treatment. In a 3-year long-term stability study by Baek et al.136 in patients who had intrusion of maxillary molars, the relapse rates were 23% for intruded molars and 17% for overbite. A total of 80% of the relapse of maxillary molars occurred in the first year of retention. Relapse of maxillary molars after treatment leads to clockwise rotation of the mandible, an increase in anterior facial height, and a change in the pogonion in a downward and backward direction. However, compensatory eruption of maxillary anterior teeth occurred during the first and third years, events that subsequently maintained the overbite. The major relapse of maxillary molars occurs in the first year after intrusion with mini-screws.

Figure 9-33 A–C, Pre-treatment intraoral views of a patient with an anterior open bite that relapsed after orthodontic treatment. D–F, Final intraoral views of the patient treated by intrusion of upper and lower buccal segments by means of skeletal anchorage without extrusion of the incisors. G–I, Intraoral views 1 year after debonding show very good stability of the anterior open-bite correction. J-L, Intraoral views 3 years after debonding show very good stability of treatment.

An effective method of retention is recommended to improve the long-term stability of molar intrusion with skeletal anchorage. However, an appropriate protocol for retention of an intruded tooth is lacking. Baek et al.136 advocate using an active retainer, which consists of a clear vacuum-formed retainer with buttons attached to either the buccal or the palatal side of the maxillary molar. Elastics can be engaged from the mini-screws or mini-plates to the buttons.

Positioners are routinely suggested during the retention phase. The elasticity of positioners between the molars applies an intrusive force through daily chewing exercises.137 Deguchi et al.138 recommend the use of myofunctional appliances because muscular imbalance has also been attributed to relapse of a treated anterior open bite. Masticatory muscle exercise involving a chewing gum or soft bite wafer during retention might aid in retaining the obtained result.139

Summary

The etiology of the long face and anterior open-bite malocclusions is multifactorial. Distinguishing between a dentoalveolar and a skeletal open bite is important. Treatments to correct this malocclusion rely mainly on the molar vertical control and/or extrusion of the anterior segments in growing patients. With the advent of implant anchorage, skeletofacial changes can also be obtained with molar intrusion in nongrowing patients. If esthetic results are desired in patients with severe long face morphology, surgical options should be explored. Although all of these treatments provide the possibility of attaining satisfactory outcomes, long-term stability remains the major challenge regardless of the therapy chosen.

References

1. Ellis E 3rd, McNamara JA Jr. Components of adult Class III open-bite malocclusion. Am J Orthod. 1984;86(4):277–290.

2. Sassouni V, Nanda S. Analysis of dentofacial vertical proportions. Am J Orthod. 1964;50(11):801–823.

3. Schudy FF. Cant of the occlusal plane and axial inclinations of teeth. Angle Orthod. 1963;33(2):69–82.

4. Sassouni V. A classification of skeletal facial types. Am J Orthod. 1969;55(2):109–123.

5. Schudy FF. Vertical growth versus anteroposterior growth as related to function and treatment. Angle Orthod. 1964;34(2):75–93.

6. Nanda SK. Patterns of vertical growth in the face. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1988;93(2):103–116.

7. Parker JH. The interception of the open bite in the early growth period. Angle Orthod. 1971;41(1):24–44.

8. Björk A. Prediction of mandibular growth rotation. Am J Orthod. 1969;55(6):585–599.