Socio-behavioural aspects of health and illness

The importance of social and behavioural sciences to pharmacy

The importance of social and behavioural sciences to pharmacy

The meaning of health and illness

The meaning of health and illness

Changing health-related behaviour and the related models

Changing health-related behaviour and the related models

How people behave when they are ill

How people behave when they are ill

Introduction

To develop a full understanding of the use of medicines by individuals and society and the role that pharmacy contributes to health care, an understanding of the sociology and psychology of health is required. These two factors are closely interwoven, and help the pharmacist to understand the influences on an individual’s behaviour in relation to their health and any illness they encounter.

In pharmacy practice research, sociological and psychological influences on health have often been under researched, with research often focused on adherence in a mechanistic manner. However, if pharmacy as a profession wishes to understand and resolve medicine and medicine-related problems, we need to broaden our perspectives to incorporate relevant social and behavioural theory and research.

The purpose of this, and the following chapter is to provide the reader with a broad overview of the health-related issues from a health sociological and psychological perspective; emphasizing the need to understand the wider influences on individual behaviour in order to enhance our pharmacy practice. The social sciences have a shared focus on understanding patterns and meaning of human behaviour, which distinguishes them from the physical and biological sciences.

Illness can be perceived as either a solely biophysical state, or a more comprehensive view may be taken, viewing illness as a human societal state where behaviour varies with culture and other social factors. It is argued that viewing illness as purely a malfunction of a physical process or structure underemphasizes the influence of the individual and psychosocial issues on their beliefs, thoughts and behaviour.

Pharmacists have to deal with many social and behavioural issues in their daily work, either directly or indirectly through health-related behaviour. The contribution of social sciences to pharmacy and pharmacy practice can be summarized in the following three areas:

Analysing the practice of pharmacy – helping to identify important questions relating to the use of medicines, pharmacy practice and the pharmacy profession

Analysing the practice of pharmacy – helping to identify important questions relating to the use of medicines, pharmacy practice and the pharmacy profession

Providing conceptual and explanatory frameworks for understanding human behaviour in a social context

Providing conceptual and explanatory frameworks for understanding human behaviour in a social context

Providing appropriate approaches to study the use of medicines and the practice of pharmacy.

Providing appropriate approaches to study the use of medicines and the practice of pharmacy.

It is impossible in two chapters to provide a comprehensive review of all the aspects of health sociology and psychology that may be relevant to pharmacy. Instead, the aim is to highlight the relevant key areas that may lead the reader to explore the sociological and psychological literature in more detail; a good starting point is the books and articles on the topic that are included in the further reading (Appendix 4).

This chapter will focus on defining health and illness and exploring the determinants of health and illness for an individual. It is important for a pharmacist to understand the influences and processes involved in illness behaviour and treatment to enable effective, patient-centred practice. In each area, the major concepts and theories that provide a deeper understanding of health and illness are briefly discussed.

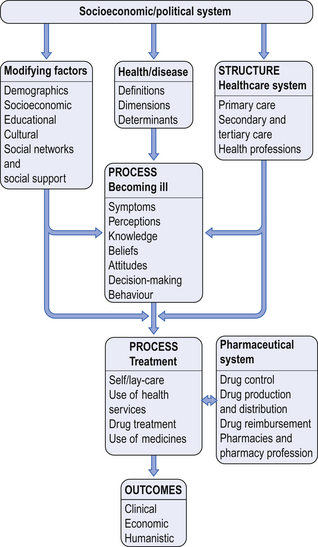

An overall framework is presented in Figure 2.1.

Defining health and illness

Health and illness mean different things to different people, it is very subjective, and it is easy to take good health for granted. Commonly, health is seen as the absence of signs that the body is not functioning properly or absence of symptoms of disease or injury. Health is often perceived as a dichotomy; you are either healthy or you are not, but in reality, health is a continuum of different states, and both societal and individual perceptions influence our understanding of health.

However, disease, in contrast to illness, is something professionally defined. The organization of current health care around the world uses this concept of illness to frame its structures, yet research has shown that physicians and experts vary in their views on both physical and mental disease, such that it is difficult to argue that disease can be easily defined.

In reality, illness is more often a state defined by the individual patient based on their own subjective reaction to a perceived biological alteration of body or mind. It has both physical and social connotations. Our perception of illness is influenced by individual, cultural, social and other factors. Illness is also a socially defined condition, resulting in the individual being assigned a particular social status by other members of their society. Parson’s concept of a societal ‘sick role’ and its effect on illness and health care will be explored in more detail.

It is important to understand that an individual may have a disease and not be ill, might be ill but not have a disease or might have both an illness and a disease.

The most widely used definition of health or wellness is that of the WHO, which states that: ‘health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of diseases and infirmity’. This definition incorporates all aspects of health and although holistic and widely quoted, it is used less by policy makers in the healthcare arena, as it does not provide guidance on which to base funding decisions.

The WHO definition offers a goal for health that is actively sought through positive actions and not merely through a passive process of avoiding disease-causing agents.

Dimensions of health

The WHO definition of health distinguishes between three aspects; physical, mental and social health, but very often healthcare systems use a narrower definition of health incorporating only physical and mental health to focus their resource allocation.

In utilizing the wider definition of health, there is a danger that we begin to ‘medicalize’ our society – issues such as loneliness, domestic violence and attention deficit disorder become the responsibility of medicine and public health, when they may not need medical treatment in the way that other diseases require. In opposing the argument, the broad definitions allow us to examine health issues in a holistic manner.

Physical health

Most of us see physical health as being free from pain, physical disability, acute and chronic diseases and bodily discomfort. However, our prior experiences of illness, our age, education and a variety of other personal and social factors will influence our perception of physical health. Health has to be understood to be subjective – what one individual may consider to be poor health may not be perceived as such by another. In dealing with patients and their health, the pharmacist needs to work to understand the individual’s perceptions to facilitate effective interactions.

Mental health

Mental health comprises of an individual’s ability to deal constructively with reality and to adapt effectively to change, to hold a positive self-image and to cope with stressors and develop intimate relationships. Furthermore, enjoying the pleasures of ordinary life and making plans for the future are important aspects of mental health.

Spiritual health

Spiritual health is considered by some as part of the mental health dimension, while others argue that it is a separate dimension. It should not be confused with religion or religiousness. A sense of spiritual well-being is possible without belonging to an organized religion. Spiritual health has been characterized as the ability to articulate and act on one’s own basic purpose of life, giving and receiving love, trust, joy and peace, having a set of principles to live by, having a sense of selflessness, honour, integrity and sacrifice and being willing to help others achieve their full potential. By contrast, negative spiritual health can be described by loss of meaning in one’s life, self-centredness, lack of self-responsibility and a hopeless attitude.

Social health

The impact of social health on the well-being of the individual has been widely demonstrated. Social integration, social networks and social support have both direct and indirect influences on health. A low socioeconomic status defined by educational level, income and occupation is closely related to higher morbidity and mortality.

Determinants and models of health

Throughout history, the concepts of disease have changed. Early explanations involved evil spirits causing disease. Hippocrates (460–370 bc) suggested that the imbalance of the four body fluids caused disease, while during the Middle Ages, illness was seen as God’s punishment.

Later in time, in the post-Renaissance period, René Descartes suggested that the body could be viewed as a machine and he theorized how action and sensation occur. In addition, he proposed that the body and mind were separate but could communicate, and that the soul leaves the human body at death.

Since Descartes’ time, advances in science have led scientists to develop a more advanced understanding of the working of the body and the processes of illness and disease. The role of microbes and other agents in causing disease is understood, along with the effect of nutrition, hygiene and other lifestyle factors.

The biomedical model of disease proposes that all diseases and illness can be explained by disturbed physiological processes. The disturbances may be caused by injury, biochemical changes and bacterial, viral or fungal infection. This model separates the physical from the psychological and sociological influences on health. The biomedical model has dominated healthcare processes for a significant period of time, but in more recent years, there has been a recognition that it is not possible, or helpful, to separate out the components of an individual’s life; the biopsychosocial model incorporates the interplay of biological, psychological and social aspects of a person’s life on their health.

Individuals in both industrialized and less developed cultures continue to be influenced in their health behaviours by both cultural and religious beliefs. These may relate to ‘bad’ behaviour, weather, accidents, black magic, witchcraft, spirits and one or more Gods, to name but a few.

Genetic and biological determinants

In line with scientific developments, current medicine is interested in the genetic basis of disease and it does seem that it may be possible to determine an origin of many health problems in the human genes. Newspapers proclaim each discovery loudly, such as the possibility of genes that predispose to alcoholism and obesity, along with many others. This may lead to the belief that all health problems develop from a genetic ‘fault’ and these lie beyond the control of each individual, which may legitimize poor health behaviour. In reality, the picture is more complex, with health, and conversely disease, arising from an interaction of individual genetic, psychosocial and physical factors.

The scientific interest in this field lies in interactions between genetic predisposition and psychosocial factors encountered in early childhood. For example, research has shown that genetically predisposed, spontaneously hypertensive rat pups who were fostered to normotensive mothers did not develop hypertension as they matured, suggesting that genetic predisposition can be overcome by a favourable environment in the early years.

Behavioural determinants

The major leading causes of death in Western society today – heart disease, cancer, stroke and accidents – are all associated with behavioural risk factors. The origin of many chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension can be found in lifestyle factors. A sedentary lifestyle predisposes an individual to develop these diseases, regardless of genetic factors. Simple changes to behaviour, such as effective weight control, stopping smoking and regular exercise, will often prevent the onset of diseases such as heart disease and diabetes. It is possible, however, that for some individuals, the inheritance of a protective genetic profile protects them from poor health caused by poor health-related habits.

Health psychology is a branch of psychology focusing on the behavioural and mental processes that contribute to health and illness. It focuses on cognition, emotion and motivation. Cognition involves perceiving, knowing, learning, remembering, thinking, interpreting, believing and problem solving. Emotion is a subjective feeling that affects and is affected by our thoughts, beliefs and behaviour. Emotions can be positive/pleasant or negative/unpleasant. Those individuals whose emotions are more positive have reduced incidence of disease and have much faster recovery times than those whose emotions are more negative. Motivation is the driver for individuals to behave the way that they do, influences individuals adopting new health-related behaviour, and the way they choose to take their medication or otherwise. Health psychology studies the effects of interpersonal relationships on individuals; our interactions with others, their thoughts, feelings and actions which in turn influences our own thinking and behaviour.

In studying a particular situation, there can be components of cognitive, affective (emotional), behavioural and interpersonal influences and separating these may be difficult. For example, an individual experiencing anxiety in a given situation may think that they lack control (cognitive), feel fear (affective), experience physical symptoms such as sweating palms and raised heart rate (behavioural) and seek out support and reassurance from others (interpersonal).

One of the major psychological issues that affects health is stress. Stress is an increasing factor in modern lives and arises when an individual experiences a situation in which they perceive that they are not able to cope with what is being asked of them, either physically emotionally or socially. Due to the interconnection of body and mind, the mental stress causes physical responses, including the release of catecholamines and corticosteroids, which may contribute to illness with continued exposure. The cardiovascular system can be affected and the emotional response to stress can result in anxiety and depression, which in turn have been shown to reduce the effectiveness of the immune system, putting the individual at risk of other diseases.

Stress can also affect an individual’s health through altered health-related behaviour. People experiencing high levels of stress often consume more alcohol, drugs and smoke more than those with less stress, and they also experience more accidents.

Stress is therefore of concern when helping individuals to improve their health, and needs to be considered when advising patients in a pharmacy, as it will be affecting their behaviour and thinking.

Environmental determinants

Environmental factors (biological, chemical, physical, mechanical) that affect human health are widely understood and have been studied in detail. External contaminants can enter the body through the air we breathe, the items we ingest, either through direct contamination on food, or indirectly through the food produced from the soil.

The role of air-borne pollen in hayfever, other allergens such as pet dander and dust mites in asthma and the risks to health from contaminated water are well understood, but there are other contaminants from the environment that need to be considered, such as drug residues in the meat and meat products we eat, that can have an effect on health from the time of conception onwards.

Environmental risk factors can affect a far greater number of people at a given time than more individual factors such as genetic susceptibility or psychological responses. While individual risk factors can account for some of the differences seen in disease occurrence, they cannot account for all. Work to reduce individuals’ risk factors for a given disease has only a limited impact on the disease occurrence, and Rose (1985) suggested that the causes of individual differences in disease may be different from the causes of differences between populations. Even where there is a strong link between a risk factor and the incidence of a disease, the disease may never develop in a particular individual.

Socioeconomic determinants

Socioeconomic determinants of health are socially situated factors that influence health, or may predispose an individual or population to poor health. Each society develops its own set of health-related values, both positive and negative, and these are reflected in the media used within the society. Western society sees being fit and healthy as ‘good’ and this exemplifies a positive value, while individuals in the public eye seen undertaking activities such smoking cigarettes or using illegal drugs exemplify a negative value. These societal values influence individuals and the way in which they behave, but the primary influence on an individual’s behaviour is often their families.

An individual’s family is the closest and most constant social relationship for the majority of people. Therefore, we learn and model many of our health-related habits, behaviours and attitudes on those of our close family. The degree of support or encouragement provided by family and friends when an individual undertakes a health-related activity can be an important factor in the potential for success.

The economic situation of an individual has been shown to have a great influence on their health. In developing countries, factors such as poverty, poor nutrition and poor resistance to pathogens are all interrelated in producing poor health status for the population, and in reducing the average life expectancy. Individuals living in the more industrialized, richer countries have improved health and greater life expectancy.

In addition to the international correlation between health and socioeconomics, the relationship between socioeconomic status and ill health can also be seen across the levels of the social hierarchy within a population. Those individuals who are wealthier within a society also have better health. Health is also linked to education, and those with better education levels tend to be healthier – their increased education level may also lead to a better financial situation, and this also correlates to improved health and longevity.

The relationship between socioeconomic status and health may therefore be related more to relative deprivation rather than absolute deprivation. Having less within your own society, even where this does not mean that the individual is deprived of the basic needs for life, or health care, still has a negative impact on your health. Better lifestyle habits may partially explain these social hierarchy differences, with those of a higher socioeconomic status potentially having healthier habits than those from lower socioeconomic groups, but does not provide a full explanation for the observed differences in health.

These differences in social situations that produce an effect on health are referred to as ‘health inequalities’. Health inequalities within a society are often targeted with resources and interventions in order to try and produce population-wide improvements and equality in health (see Ch. 13).

Interaction of different factors

It is evident that no single influencing factor provides an explanation for the health of a nation, demographic group or individual. The factors discussed above interlink and provide a complex picture in which to determine the defining influences on the health. In considering an individual’s health and illness, it is necessary to assess the impact of all aspects of a person’s life as a total entity – this approach is called ‘holism’.

There are models that try to describe the interactions between factors influencing health, and one such comprehensive model is the ‘nested model of health’. This model consists of two levels of activity: the individual and the community level. The individual level is composed of five different categories:

Psychosocial environment (e.g. personal relationships, housing)

Psychosocial environment (e.g. personal relationships, housing)

Microphysical environment (e.g. chemicals and noise)

Microphysical environment (e.g. chemicals and noise)

Work environment (e.g. work stress)

Work environment (e.g. work stress)

Behavioural environment (e.g. smoking, alcohol use, exercise)

Behavioural environment (e.g. smoking, alcohol use, exercise)

These categories are thought to affect each other and to affect and be affected by the individual. The individual level is nested/located in the centre of the community level.

This community level, which is the main focus of health policy decision-makers, is composed of four components:

The political/economic climate (e.g. unemployment level)

The political/economic climate (e.g. unemployment level)

The macro-physical environment (e.g. air quality)

The macro-physical environment (e.g. air quality)

These four components are interrelated and changes in them are expected to lead to changes in the health of individuals.

This model shows the potential influences on the health of an individual and provides the healthcare professional with an idea of the complexity of the influences on an individual’s health status.

Process of illness

Becoming ill

As pharmacists, we need to understand how and why people respond to illness in such differing ways. Health-related behaviour varies between individuals for all the reasons discussed above, and this may help to explain the subjective way in which patients respond to seemingly similar symptoms, such as pain or discomfort. Generally, individuals perceive themselves as ‘well’ if they have a feeling of well-being, experience no symptoms and are able to perform normal functions. This is the baseline situation against which any changes in health are measured. As an individual’s health status changes, there will be a corresponding change in their health-related behaviour.

Kasl and Cobb in 1966 defined three types of behaviour that characterize three stages in the progress of disease:

Health behaviour, which refers to ‘any activity undertaken by people believing themselves to be healthy for the purpose of preventing disease or detecting it at an asymptomatic stage’

Health behaviour, which refers to ‘any activity undertaken by people believing themselves to be healthy for the purpose of preventing disease or detecting it at an asymptomatic stage’

Illness behaviour, which involves an activity undertaken by people experiencing illness, in order to determine their state of their health and receive appropriate treatment

Illness behaviour, which involves an activity undertaken by people experiencing illness, in order to determine their state of their health and receive appropriate treatment

Sick-role behaviour, which refers to the activity that individuals, who consider themselves ill, undertake in order to get well.

Sick-role behaviour, which refers to the activity that individuals, who consider themselves ill, undertake in order to get well.

Health behaviour is undertaken to benefit health, while illness behaviour and sick-role behaviour are aimed at minimizing the effects of illness.

Identifying and reacting to symptoms

Individuals can, and do react differently to symptoms of disease. Different symptoms may be perceived very differently, depending on the person, setting and situation. A behaviour which in some situations is regarded as normal and natural, can in other situations be regarded as a sign of illness. For example, being tired after a long day at work or after an exercise session is normal, while continuous tiredness without due cause may be a sign of illness.

We all use our current and past experiences of illness, our social exposure to illness, through family and friends and societal derived values to judge our illness, and these affect our health behaviour. The significance of symptoms is judged according to the degree of interference with normal activities, the familiarity and clarity of symptoms, the person’s tolerance threshold, preconceptions about cause and prognoses, and the influence of friends and family. The presence of other stressors and life crises may also make the symptoms appear more severe to the individual. These subjective and psychosocial aspects may exert a greater influence over the individual’s decisions and actions than the symptoms themselves.

The way in which an individual experiences illness involves affective and cognitive reactions, resulting in emotional changes in the person as they attempt to understand the illness. Bernstein and Bernstein have described these emotional reactions to illness and treatment in the following ways:

Those directly related to illness or treatment, including fear, anxiety and a feeling of damage and frustration caused by loss of pleasure and enjoyment

Those directly related to illness or treatment, including fear, anxiety and a feeling of damage and frustration caused by loss of pleasure and enjoyment

Reactions determined primarily by life experience before or during illness, such as anger, dependency and guilt

Reactions determined primarily by life experience before or during illness, such as anger, dependency and guilt

These three emotional responses interact to produce the overall response in an individual and produce complex and varied reactions to illness.

In general, women are more likely to interpret discomfort as a medical symptom and they also recall and report more symptoms when consulting a healthcare professional. These differences may partly be explained by a higher interest in and concern with health issues among women.

An individual’s family often plays an active role in the symptom identification process, as other family members may recognize some symptoms before the person does. The family also takes part in the interpretation process of symptoms.

The individual’s cultural background is also an important factor influencing the process of symptom identification and evaluation. Some cultures more readily describe common symptoms as medical, while others tend to suppress signs of illness. There might also be differences between generations in this respect, in so much as symptoms previously considered as normal may today be seen as something requiring medical attention.

Sick-role behaviour

When people perceive themselves to be sick, they adopt the so-called ‘sick-role behaviour’; a socially determined role. This includes the following components:

The patient is not blamed for being sick

The patient is not blamed for being sick

The patient is exempt from work and other responsibilities

The patient is exempt from work and other responsibilities

The illness is seen as legitimate as long as the patient accepts that being ill is undesirable

The illness is seen as legitimate as long as the patient accepts that being ill is undesirable

The patient is expected to seek competent help to get well again.

The patient is expected to seek competent help to get well again.

Not all people follow the patterns of the sick role but it does provide a general framework to help understanding illness behaviour. However, this framework is not able to explain variations within illness behaviour; it is not applicable to chronic disease, where getting better may not be realistic and often does not apply to mental illness. In addition, there may be certain diseases, such as alcoholism, where there might be unwillingness within society to grant exemptions from blame.

The role of personality in illness

Aspects of an individual’s personality have been shown to be associated with illness and poor health. People who have high levels of anxiety, depression and anger/hostility traits seem to be more disease prone than others. Emotions, such as anxiety and depression may be a reaction to different types of stress. People handle stressful situations in different ways and an individual’s approach to stress affects the impact of stress on their health. People who approach stressful situations more positively and hopefully, are less disease prone and also tend to recover in a shorter time if they get ill. Those who are ill will recover faster if they can overcome their negative thoughts and feelings.

Friedman and Rosenman in 1974 described differences in behavioural and emotional style, and their effects on health, when studying the behaviour of cardiac patients. They named the behaviour patterns they saw as ‘Type A’ and ‘Type B’.

Type A behaviour pattern is characterized by:

A competitive achievement orientation, with high levels of self-criticism and striving towards goals while not experiencing a sense of joy in achievements

A competitive achievement orientation, with high levels of self-criticism and striving towards goals while not experiencing a sense of joy in achievements

Time urgency, e.g. tight scheduling of commitments, impatience with time delays and unproductive time

Time urgency, e.g. tight scheduling of commitments, impatience with time delays and unproductive time

Anger/hostility which is easily aroused. Type A individuals respond faster and with more emotion to stress, often seeing stressors as threats to their personal control – this behaviour seems to be particularly detrimental to health.

Anger/hostility which is easily aroused. Type A individuals respond faster and with more emotion to stress, often seeing stressors as threats to their personal control – this behaviour seems to be particularly detrimental to health.

The Type A pattern may also increase the person’s probability of getting into stressful situations. The relationship between Type A behaviour and psychosocial factors is very complex. Type B individuals take life more easily with little competitiveness, time urgency and hostility.

Interestingly, the overall evidence for an association between Type A and Type B behaviour and general illnesses is weak and inconsistent. However, many studies, have shown a clear association between Type A behaviour and coronary heart disease.

Health knowledge, beliefs and attitudes

The concept of health knowledge may include a variety of components such as beliefs, expectations, norms and cognitive perceptions. Health knowledge is therefore more than merely having some factual knowledge about diseases and treatment.

Knowledge about a disease can improve a patient’s health by improving their problem-solving capacity. Preventive behaviours, participation in the treatment process and taking medications all require a certain amount of knowledge. The current trend emphasizing guided self-care in chronic diseases such as asthma, diabetes and hypertension, requires a well-informed patient. The aim is to produce patients who actively participate in their own treatment. The starting point is providing the necessary information and improving the factual knowledge of the patient. It has been shown, however, that knowledge alone is insufficient to ensure behaviour change, which is often the goal.

In addition to improving patients’ knowledge, there also needs to be a change in attitude in order for them to undertake new health-related behaviours. Attitudes have been defined as states of readiness or predisposition, feelings for or against something, which predisposes to particular responses. They involve emotions (feelings) and knowledge (or beliefs) about the object and result in behaviour changes. Attitudes are not inherited but learned and, though relatively stable, are modifiable by education.

There are a number of models that have been suggested to explain the interaction between knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and behaviour in health:

The health belief model

The health belief model, developed by Rosenstock and colleagues in 1966, to predict the use of preventive health services, has been extensively used during the last two decades to try to explain various health behaviours. The model has been further developed to predict health behaviour in chronic diseases and compliance with healthcare regimens.

According to the model, the probability that a person will take a preventive health action – that is, perform some health, illness or sick-role behaviour – is a function of:

Their perception of their own susceptibility to the health problem or disease (How likely am I to get it?)

Their perception of their own susceptibility to the health problem or disease (How likely am I to get it?)

Their perception of the severity of medical and social consequences of the disease (How ill would it make me?)

Their perception of the severity of medical and social consequences of the disease (How ill would it make me?)

Their perception of the benefits and barriers (costs) related to the recommended behaviour (What will I gain and what will it cost me?).

Their perception of the benefits and barriers (costs) related to the recommended behaviour (What will I gain and what will it cost me?).

All three of these aspects are based on subjective perceptions which can be modified, at least in theory.

According to the model, the more vulnerable the person feels and the more serious the disease the more likely it is the person will act. Various factors that result from the perceptions are expected to modify this motivating force. These factors include demographic, socioeconomic and therapy-related factors as well as the illness itself and the prescribed regimen. Prior contact with the disease or knowledge about the disease may modify the behaviour. Some incidents, so-called ‘cues to action’, are also expected to trigger the desired behaviour. These cues to action might include a mass media campaign, magazine article, advice from others or illness of a family member.

The concept of perception is important in the health-belief model. It is the patient’s and not the pharmacist’s perceptions that drive the decisions and behaviours of the patient. Once an individual has been diagnosed with an illness then their concept of personal susceptibility has been modified because they know they have an illness. Studies into health belief try to overcome these issues by examining the individual’s estimate of or belief in the accuracy of the diagnosis. This concept has also been extended to measuring the individual’s subjective feelings of vulnerability to various other diseases or to illness in general. Studies show that in hypertension, for example, the threat posed by hypertension and the perceived effectiveness of treatment in reducing this threat are important predictors of compliance. Likewise the perceived control over one’s own health is important. There is some controversy about the chronology of these beliefs and whether they precede or develop simultaneously with health behaviour.

The health belief model and common sense might tell us that the patient’s decision to seek health care, accept a diagnosis and engage in health-related behaviours would be related to the seriousness of the disease. Research indicates this may not always be the case. Patients’ health behaviours are a function of many psychosocial variables. (Reasons why humans may behave illogically are dealt with below in ‘The conflict theory’ and ‘Decision analysis and behavioural decision theory’).

The theory of planned behaviour

The theory of planned behaviour offers an explanation of the factors that help to determine an individual’s health-related behaviour. The actions of each individual are determined by their intention to perform, or not, any particular action; and their intention is determined by both personal and social influences. Two personal influences exert an effect on an individual’s intentions. The first is ‘attitudinal considerations’, which are related to the individual’s beliefs in the positive or negative effects of their behaviour, i.e. will it make me better or not? The second is the individual’s perception of the ease or difficulty of performing the action, their ‘perceived behavioural control’. The social influences, or ‘subjective norm’ relates to the pressure from the society in which they are present to undertake the behaviours or otherwise. The pressure exerted by the normative beliefs acts independently of the individual’s personal beliefs, and so may be in opposition to them. So in the case of individuals contemplating changing their behaviour, their own opinions on the new behaviour, and the illness it may avoid, will exert an influence over the chances of them undertaking the new behaviour, as will their perception of the difficulty or ease of doing this new activity or acting in a new way. They will also be affected by how their friends, family and society see the new behaviour; if positive and a good idea, then the individual is more likely to undertake it, while if they get negative comments these may justify not undertaking the new behaviour. In a situation where there is a conflict between the attitudinal considerations on one side, and the perceived behavioural control and subjective norms on the other, the action itself helps to determine which takes precedence in determining action or non-action.

The theory of planned behaviour proposes that the subjective norm and the attitude regarding the behaviour combine to produce an intention, which leads to the behaviour.

If behaviour is determined by beliefs, then what factors determine beliefs? Factors such as age, sex, education, social class, culture and personality traits all influence an individual’s beliefs. These variables influence behaviour indirectly rather than directly. One of the problems with the theory is that people do not always do what they plan, i.e. intentions and behaviour are only moderately related. Another problem is that people do not always act rationally. Irrational decisions such as delaying medical treatment when symptoms exist cannot be explained by the model. Neither does the model include prior experiences with the behaviour, which might be an important factor to consider, since past behaviour is a strong predictor of future practice of that behaviour.

The conflict theory

The conflict theory has been used to explain rational and irrational decision-making. According to the model how a person arrives at a health-related decision involves five stages. It starts when something challenges the person’s current course of action. It can be a threat (e.g. symptom) or a mass media alert about, for example, the danger of narcotics or an opportunity (e.g. free membership to a health club). The different stages of the conflict theory model are:

Assessing the challenge, i.e. whether the risk is serious enough. The assessment may involve thoughts such as the risk is not real, it is irrelevant or inapplicable. If the risk is not considered serious enough, the behaviour continues as before and the decision-making process stops

Assessing the challenge, i.e. whether the risk is serious enough. The assessment may involve thoughts such as the risk is not real, it is irrelevant or inapplicable. If the risk is not considered serious enough, the behaviour continues as before and the decision-making process stops

Assessing alternatives, i.e. the search for alternatives for dealing with the risk starts when the risk is acknowledged. This stage ends when the suitability of available alternatives has been surveyed

Assessing alternatives, i.e. the search for alternatives for dealing with the risk starts when the risk is acknowledged. This stage ends when the suitability of available alternatives has been surveyed

Weighing alternatives, i.e. the pros and cons of each alternative are weighed to find the best option

Weighing alternatives, i.e. the pros and cons of each alternative are weighed to find the best option

Making a final choice and committing to it

Making a final choice and committing to it

Adhering despite negative feedback, i.e. after starting a new behaviour people may have second thoughts about it if the environment is not supportive or it gives negative feedback.

Adhering despite negative feedback, i.e. after starting a new behaviour people may have second thoughts about it if the environment is not supportive or it gives negative feedback.

The decision process can be aborted at any point. Errors in decision-making are often caused by stress, which affects health, information overload, group pressure and other factors. According to the conflict theory, a person’s coping with a conflict is dependent on the presence and absence of risks, hope and adequate time. Different combinations of these may result in different types of behavioural response. For example, when there are perceptions of high risk in changing the behaviour and no hope in finding a better alternative, a high level of stress is experienced. Denial and shifting responsibility to someone else are typical responses, with delays in seeking care. The perception of serious risk and belief in a better alternative, but also a perception of running out of time, also create high levels of stress. People search desperately for solutions and may choose an alternative hastily if promised immediate relief. The perception of serious risk, with a belief that a better alternative will become available, along with time to search for it, results in low levels of stress and more rational choices.

Locus of control

It has been claimed that individuals’ perception of their ability to influence disease and their treatment is an important determinant of health behaviour. People have been categorized into two groups: those with an internal locus of control and those with an external locus of control. The former tend to perceive that they are in control of their own health by their actions and behaviour, while the latter consider that health is externally determined and their actions have little or no effect. Therefore those with a strongly internal locus of control should tend to practise behaviours that prevent illness and promote health. Research has shown that this is the case, but the relationship is not very strong. This locus of control is just one factor among many others that determine health behaviour. Belief in internal control is likely to have a greater impact among people who place a higher value on their health than among those who do not.

Self-efficacy and social learning

Sometimes performing a health action is hard to do because it is technically difficult or it may involve several steps. Therefore the belief in the success in doing something – called self-efficacy – may be an important determinant in choosing or not choosing to change behaviour. People develop a sense of efficacy through their successes and failures, observations of others’ experiences and assessments of their abilities by others. People assess their efficacy based on the effort that is required, complexity of the task and situational factors, e.g. the possibility of receiving help if needed. People who think they are not able to quit smoking will not even try, while people who believe they can succeed will try and eventually some may succeed.

Those with a strong sense of self-efficacy show less psychological strain in response to stressors than those with a weak sense of efficacy. People differ in the degree to which they believe they have control over the things that happen in their lives. Those who experience prolonged, high levels of stress and lack a sense of personal control tend to feel helpless. Having a strong sense of control seems to benefit health and adjustment to sickness.

As environmental factors and expectations directed towards the individuals change, they must either intensify their activities or change their environment. Individuals have different capabilities of coping and different coping strategies. According to the Social Learning Theory, people change their environment with the help of symbols they choose in accordance with their values, norms and goals. On the other hand, the environment changes the individual’s behaviour by rewarding beneficial activities and punishing or not rewarding activities that harm the environment. Through the socialization process the individual adopts the values and norms of the community, is socialized as its member and gains identity. Through this process the individual has learned to act efficiently in social systems.

Antonowsky has used the ‘sense of coherence’ concept, which is an extensive and constant feeling of an individual’s internal and external environment being in harmony with each other. Every individual has characteristic psychosocial potentials that include material resources, intelligence, knowledge, coping strategies, social support, arts, religion, philosophy and health behaviour. Antonowsky calls a sense of coherence ‘salutogenic’ or health generating. Disease–health is a continuum, at one end of which is a high degree of coherence and health (‘ease’) and at the other end a low degree of coherence and illness (‘dis-ease’). External factors that the individual considers threatening mobilize the defence mechanisms and cause stress conditions in the individual. Prolonged stress is disease generating and causes the condition ‘dis-ease’.

Coping

Because of the emotional and physical strain that accompanies it, stress is uncomfortable and people are motivated to do things that reduce their stress. The concept of coping is used to describe how people adjust to stressful situations in their life. Coping is the process by which people try to manage the perceived discrepancy between the demands and resources they appraise in stressful situations. Coping means the ability to meet the demands of new situations and solve the problems with which one is confronted. Coping is determined by situational and personal determinants. At the individual level, external factors turn into stress factors if previous experiences together with personality traits, consciously or unconsciously, are considered as threatening or diminish self-esteem. Coping efforts can be quite varied and do not necessarily lead to a solution of the problem. It can help the person to alter his perception of a discrepancy, tolerate or accept the harm or threat and escape or avoid the situation.

Coping mechanisms

Coping can alter the problem or it can regulate the emotional response causing the stress reaction to the problem. Behavioural approaches include using alcohol or drugs, seeking social support from friends or simply watching TV. Cognitive approaches involve how people think about the stressful situation, e.g. changing the meaning of the situation. Emotion-focused approaches are used when people think they cannot do anything to change the stressful situation. Problem-focused coping is used to reduce the demands of the stressful situation or to expand the capacity and resources to deal with it. The two types of coping can also be used together. Commonly used methods of coping are:

The direct method, i.e. doing something specifically and directly to cope with a stressor, e.g. negotiating, consulting, arguing, running away

The direct method, i.e. doing something specifically and directly to cope with a stressor, e.g. negotiating, consulting, arguing, running away

Seeking information and acquiring knowledge about the stressful situation

Seeking information and acquiring knowledge about the stressful situation

Turning to others, i.e. seeking help, reassurance and comfort from family and friends

Turning to others, i.e. seeking help, reassurance and comfort from family and friends

Resigned acceptance, i.e. the person comes to terms with the situation and accepts it

Resigned acceptance, i.e. the person comes to terms with the situation and accepts it

Emotional discharge, i.e. expressing feelings or reducing tension by taking, e.g. alcohol, drugs or smoking cigarettes

Emotional discharge, i.e. expressing feelings or reducing tension by taking, e.g. alcohol, drugs or smoking cigarettes

Intrapsychic processes, i.e. cognitive redefinition, e.g. the ‘things could be worse’ attitude.

Intrapsychic processes, i.e. cognitive redefinition, e.g. the ‘things could be worse’ attitude.

Decision analysis and behavioural decision theory

Decision analysis is a systematic way of studying the process of decision-making among patients and healthcare professionals. It is a widely used tool in pharmacoeconomics today (see Ch. 22) and usually involves assigning numbers to perceived values of therapeutic outcomes and the probability that the outcome will occur. This gives a utility of each outcome and the one with the highest utility would be chosen. One problem is that humans do not always make decisions logically or treat information as value free.

Why don’t humans behave logically? One explanation that has been offered is that humans are biased when making decisions under uncertainty because we fail to appreciate randomness. We believe that there are known causes and effects for all phenomena and we have a need to be able to explain outcomes. It is easier to explain, even incorrectly, than to have to deal with uncertain situations. People also tend to be inconsistent in their judgement, often because of difficulties in remembering how a judgement was made. Another reason is that we seldom receive feedback from negative decisions, for example if we decide not to take the medicine, we do not know how effective it would have been.

Behaviour decision theory has been used to understand how patients make decisions about their medicine and health-related behaviour. These include acquisition of information, information processing, making decisions under uncertainty and interpreting outcomes of that decision. It has been found that patients are more likely to take a health risk to avoid an aversive situation than to gain a positive health outcome. Patients are more likely to choose a certain outcome than an outcome with a high probability of occurrence, even if the certain outcome is less valued than that one with a high probability of occurrence. When a person has already invested time and money on a product or activity, they are likely to continue it, even if it does not appear to be effective.

Hogarth has described different biases that influence decision-making, which may be helpful in understanding patient choices about health behaviour. Individuals tend to believe more in well-publicized events than in those that are less publicized – think about the consumer’s choice of well-advertised OTC medicines rather than the cheaper generic alternatives. There is a tendency to selective perception, i.e. we believe what matches our existing beliefs and this has direct implications for health education in pharmacies. We tend to believe real incidents more than abstract statistics. Positive experiences from a family member quitting smoking is more likely to be effective than showing statistics about future (uncertain) consequences of smoking. Two incidents occurring close in time and place tend to be regarded as causal. Becoming ill after having taken a medicine, regardless of cause and effect, often triggers an aversive response with the same medicine in future. We are reluctant to change our beliefs, even when given new data. Very few instances of an occurrence are needed for us to form a new belief if it has a strong effect upon us and this has implications for an individual experiencing side-effects from drugs. We also believe something is more likely to happen if we want it to happen. A decision that was successful is more likely to be considered to be due to the knowledge and wisdom of the decision maker. On the other hand, a decision resulting in bad outcomes is likely to be blamed on others.

Theory into practice – the process of behaviour change

A lot of pharmacists’ activities will focus on changing the behaviour of patients. Without going into the ethical aspects of behaviour change, we will concentrate on the process of change. It has been proved several times that merely using common sense is not enough to reach permanent behaviour change. Using a common-sense approach would assume that, given the facts, people will be able to change their behaviour in a direction anticipated by the healthcare professional. A simple example illustrates the limits of this approach – why do so many people still smoke cigarettes despite knowing all the negative consequences of smoking?

Even if many of the behavioural theories are far from complete or comprehensive, they may guide us in improving the outcome of behavioural interventions. Behaviour change includes a long list of steps that need to be taken before it is finalized:

The process starts with attention. The person needs to be exposed to the message; via a counselling session by the pharmacist or a health campaign in the media. If the same message is repeated from different sources and these sources are regarded as credible, the likelihood of change grows. Therefore it is important that the information received from all healthcare professionals is congruent. If patients receive mixed messages they are more likely to ignore them

The process starts with attention. The person needs to be exposed to the message; via a counselling session by the pharmacist or a health campaign in the media. If the same message is repeated from different sources and these sources are regarded as credible, the likelihood of change grows. Therefore it is important that the information received from all healthcare professionals is congruent. If patients receive mixed messages they are more likely to ignore them

Attention is followed by motivation. The person must feel motivated to change their behaviour. It is well known that immediate rewards are more motivating than anticipated rewards after several years

Attention is followed by motivation. The person must feel motivated to change their behaviour. It is well known that immediate rewards are more motivating than anticipated rewards after several years

Next the person has to comprehend the message to be able to act upon it, but they also need to learn some facts, i.e. improve their knowledge base. These facts need to be simple and match the local culture

Next the person has to comprehend the message to be able to act upon it, but they also need to learn some facts, i.e. improve their knowledge base. These facts need to be simple and match the local culture

The following step is persuasion, i.e. the person needs to ‘change their attitude’. Furthermore, they might need to learn some new techniques and skills in how to take or handle the medication. Demonstration and guided practice are the best ways of handling this step

The following step is persuasion, i.e. the person needs to ‘change their attitude’. Furthermore, they might need to learn some new techniques and skills in how to take or handle the medication. Demonstration and guided practice are the best ways of handling this step

The person must also be able to perform the skills and maintain the learned skills, which include self-efficacy training and feedback of success. Many experiments with a long enough follow-up show that positive results can be achieved with pharmacists’ interventions, but when the experiment is over, the results soon deteriorate to pre-experiment levels

The person must also be able to perform the skills and maintain the learned skills, which include self-efficacy training and feedback of success. Many experiments with a long enough follow-up show that positive results can be achieved with pharmacists’ interventions, but when the experiment is over, the results soon deteriorate to pre-experiment levels

Continuous reinforcement is necessary to maintain good results in any intervention, be it changing medicine-taking behaviour or modification of preventive health behaviour.

Continuous reinforcement is necessary to maintain good results in any intervention, be it changing medicine-taking behaviour or modification of preventive health behaviour.

Pharmacists can help individuals change their health-related behaviour by providing information, advice and support as appropriate to each of the stages the individual will pass through. Pharmacist involvement in smoking cessation and weight loss has shown that the pharmacist can play an important role in helping individuals to live healthier lives.

The treatment process

Self- and lay-care

During the latter part of the twentieth century, a new trend emphasizing the role of the individual and patient in their own health care emerged as a part of a more general trend called ‘consumerism’. People have become more committed to taking control of their own lives and assessing the impact of their behaviour on their health, resulting in various self-care and self-help movements. The same trend has been obvious internationally, although the starting time and speed of adoption has varied. At the same time, the dominant role of healthcare professionals has diminished. Patients are asking more questions, seeking more information and taking a more active role in their health care. They have greater knowledge about their own disease and potential treatments.

These changes put increasing demands on pharmacists regarding their knowledge base, especially in therapeutics, and it also tests their communication skills. The priorities in treatment and the goals may differ between the patient and the prescribing professional and requires careful negotiation.

According to the self-care philosophy, people should be given more responsibility for their own health. One way this can be achieved is to emphasize the role of self-care in treating minor ailments using home remedies and an increasing number of self-medication products.

The most common ‘action’ in response to a perceived health problem has been to ignore the problem or wait for a few days. It is estimated that some 30–40% of health problems are dealt with in this way. Of those who take some action, 75–80% self-diagnose and use self-treatment, while only 20–25% seek professional care. Therefore a seemingly small change in this ratio (towards using more professional care) has a substantial impact and burden on the official healthcare system. Of those who use self-treatment, some 70–90% self-medicate, and of these, 80% use OTC drugs. Home remedies such as lemon, honey and garlic as well as different herbal products, vitamins and minerals, are widely used all over the world.

Before people decide to seek medical care for their symptoms, they seek advice from friends, relatives and co-workers. This lay referral network provides information and interpretation regarding the symptoms, home remedies, self-medication and gives advice on the need for professional help or consulting another ‘lay expert’ who may have had a similar problem.

The pharmacy is often the first place for people to seek help within the healthcare system due to its accessibility. The pharmacist can help distinguish between serious and non-serious symptoms and can refer on to other healthcare professions if needed. Certain situations may demand professional care without further delay caused by inappropriate self-medication practices. The lay referral network can in some cases be guilty of causing delay in seeking care. This treatment delay has been divided into three stages:

Appraisal delay is the time it takes to interpret a symptom as a part of an illness. If friends and relatives do not see the symptoms as important, then the individual may delay seeking help

Appraisal delay is the time it takes to interpret a symptom as a part of an illness. If friends and relatives do not see the symptoms as important, then the individual may delay seeking help

Illness delay is the time between recognizing the illness and the decision to seek care

Illness delay is the time between recognizing the illness and the decision to seek care

Utilization delay is the time between the decision to seek care and actually using a health service.

Utilization delay is the time between the decision to seek care and actually using a health service.

There has also been concern about misuse of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, including laxatives and codeine-containing pain relief. However, there is also a cost-saving in the reduced reliance on healthcare professionals. Pharmacists can help the public to become aware of the potential dangers of OTC medications, and can provide guidance on their safe and appropriate use.

Primary care

Simultaneously with emerging self-care, the concept of primary health care was introduced. In 1977, the World Health Assembly of the WHO adopted the concept of Health for All by the year 2000 and this concept was translated into the so-called ‘Alma Ata Declaration’. The focus was on making health care more accessible and lowering healthcare costs leading to an improvement in quality of life for the whole population. According to the declaration, primary health care should include:

Education about prevailing health problems

Education about prevailing health problems

Methods of identifying, preventing and controlling them

Methods of identifying, preventing and controlling them

Promotion of food supply and proper nutrition

Promotion of food supply and proper nutrition

Adequate water supply and basic sanitation

Adequate water supply and basic sanitation

Maternal and child health care including family planning

Maternal and child health care including family planning

Immunization against the major infectious diseases

Immunization against the major infectious diseases

Prevention and control of locally endemic diseases

Prevention and control of locally endemic diseases

Primary health care focuses on principal health problems and must be part of national health policy and planning. The conference called for cooperation and commitment in striving for an acceptable level of health for all people by the year 2000. In 2003, the WHO undertook a review of the progress in achieving an improved health status for the world population. They found that there was an international commitment, across most governments, to primary health care and the Alma Ata goal. In countries where the development had not been successful, there was usually a lack of practical guidance on implementation, poor leadership to help achieve the change, insufficient political commitment, inadequate resources and unrealistic expectations of what could be achieved in a given timeframe.

The scope of public health is population based rather than individually based. Public health problems are considered in the context of the community. It is a public health problem to determine the prevalence of a disease in the community, compare that with figures from previous years and plan health services to reduce the prevalence. Public health includes enumeration, analysing and planning, as well as identifying the specific actions to be taken. Public health exists on two levels: the micro-level, for example performing some public health function such as immunization or preventing inappropriate use of illicit drugs, and the macro-level, with activities like planning or policy formulation (see Ch. 13).

Factors influencing the use of healthcare services

The structures of the healthcare systems in different countries have a lot of similarities but also a lot of differences. The system is the sum of historical development, culture and economic factors. In some countries, there are actually several different systems in place within the healthcare system. The country you happen to live in, the organization and financing of health care, the environment of medical care, social and cultural factors all influence the care that you will receive.

Demographic factors

Several important differences have been reported between different age groups and between genders. It is well known that women report more symptoms and are more likely to seek care. Men are more hesitant than women to admit to having symptoms and to seek medical care for these symptoms. This can be a result of perceived sex-role stereotypes – men should be tough and independent and ignore or endure pain. Women use physician services more than men in all age groups except for the first few years of life. Men have a higher mortality and shorter life expectancy at all ages.

In general, young children and the elderly use physician services more often than adolescents and young adults. Age differences in health behaviour cannot be explained by biological ageing alone. Elderly people have different views from other age groups and each other on health and illness, symptoms, healthcare use and drugs. Certain ideas are more prevalent among the elderly than the young. The differences can partly be explained by so-called cohort effects, meaning people of the same age have been exposed to the same kind of experiences and attitudes in society and therefore are also likely to share certain behavioural characteristics.

Cultural and socioeconomic factors

Ethnic and cultural background may explain some differences in symptom experience, how people seek medical care and how they take their medicines. A classic 1950’s study about how people deal with pain found big differences between Italian, Jewish, Irish and Yankee (Old American) hospitalized patients. Italian and Jewish patients were more likely to respond emotionally and expressively to pain than Irish or Yankee patients, who tended to deny pain. Italian and Jewish patients showed their pain by crying, complaining and demanding, while the Irish and Yankee patients preferred to hide their pain and withdraw from others. More recent studies among immigrants in the USA found that the differences in willingness to tolerate pain diminish in succeeding generations. Other similar studies have shown cultural differences among European countries and the USA, e.g. in perception of fever and the need to medicate children with a fever.

There are also differences in seeking care according to social class, education and income – those who are better off access more healthcare services. Different models of why people seek or do not seek healthcare services have been proposed, but no one model appears to offer a full explanation of this aspect of people’s behaviour.

Social support

Social environments and networks are important in the growth, development and health of individuals. Social support is an important factor in all phases of an illness and in the treatment process. Social support relates directly to the general and universal needs of people. Maslow’s theory claims that, human needs are hierarchical, starting with basic physiological needs, followed by safety needs, belongingness and love needs, esteem needs, and finishing with the highest – self-actualization. Needs occupying the lower levels of the hierarchy need to be met before the individual will concern themselves with needs at a higher level. According to the Finnish sociologist, Erik Allardt, people’s needs can be simplified to include standard of living (‘having’), social relations (‘loving’) and forms of self-actualization (‘being’). Social relations include social networks and belonging to them is the basis of one’s identity and social existence. Social support is the term used for different forms of emotional and material support. The nature of social support is reciprocal. It can be support provided directly by one person to another or indirectly through the system or community.

Forms and levels of social support

Material or instrumental support includes money, goods, auxiliary appliances and medicine

Material or instrumental support includes money, goods, auxiliary appliances and medicine

Operational support includes service, transportation and rehabilitation

Operational support includes service, transportation and rehabilitation

Informational support includes advice, directions, feedback, education and training

Informational support includes advice, directions, feedback, education and training

Emotional support involves the expression of caring, empathy, love and encouragement

Emotional support involves the expression of caring, empathy, love and encouragement

Mental support involves a common ideology, belief and philosophy.

Mental support involves a common ideology, belief and philosophy.

Social support has two dimensions, a qualitative and a quantitative dimension and the quality of social support can be measured only by subjective assessments. When providing material support the quantitative aspect is more prominent (medicines are an exception to this); in the other support forms the qualitative aspect (including timing) is more important than the quantitative aspect. Thus a small functioning support network is better than a broad but passive one.

Social support has been divided into three levels based on the intimacy of the social relationships;

Primary level includes family and close friends

Primary level includes family and close friends

Secondary level includes friends, colleagues and neighbours

Secondary level includes friends, colleagues and neighbours

Tertiary level includes acquaintances, authorities, public and private services.

Tertiary level includes acquaintances, authorities, public and private services.

Social support can be provided by a lay person (usually on the primary and secondary level) or a professional (usually on the tertiary level). Recently, different organizations have started training courses for lay providers of support aiming at strengthening the second level of support. Social support has both direct effects on health and well-being and indirect stress-buffering effects on coping in stressful situations.

Early research showed that lack of social support exposes people to recurrent accidents, suicide and risk of catching tuberculosis. Later the emphasis was on relationships between social support structures and health in communities. It was shown that the lack of social support increases the incidence of coronary heart disease, mortality due to myocardial infarction and total mortality in the population. It has also been shown that social support is important in perceived health and in reducing hypertension. Social support has a positive effect on physical, social and emotional recovery. It reduces the need for medication and speeds up symptom amelioration.

However, having too much support may make the patient passive, create dependence and reduce self-confidence and self-esteem. Social support needs to empower the individual and not remove all control to exert a positive effect on health.

Key Points

Social and behavioural issues can help explain non-biological aspects of health

Social and behavioural issues can help explain non-biological aspects of health

Illness is a person’s reaction to a perceived alteration of body or mind, while disease is something which is professionally defined

Illness is a person’s reaction to a perceived alteration of body or mind, while disease is something which is professionally defined

Health has been defined by the WHO

Health has been defined by the WHO

Apart from biophysical factors, health is also affected by behavioural, environmental and socioeconomic determinants

Apart from biophysical factors, health is also affected by behavioural, environmental and socioeconomic determinants

People react differently to symptoms as a consequence of many factors, including family, gender and age

People react differently to symptoms as a consequence of many factors, including family, gender and age

Certain behaviour types put the individual at increased risk of disease

Certain behaviour types put the individual at increased risk of disease

Knowledge influences an individual’s response to illness

Knowledge influences an individual’s response to illness

According to the Health Belief Model, the patient’s perception is of primary importance in determining patient behaviour

According to the Health Belief Model, the patient’s perception is of primary importance in determining patient behaviour

The Theory of Planned Behaviour suggests that beliefs give rise to attitudes, which form intentions which lead to behaviour

The Theory of Planned Behaviour suggests that beliefs give rise to attitudes, which form intentions which lead to behaviour

The Conflict Theory can be used to explain rational and irrational decision-making

The Conflict Theory can be used to explain rational and irrational decision-making

Humans may not reach decisions logically for many reasons

Humans may not reach decisions logically for many reasons

Behaviour is seldom changed as a result of providing facts, but results from a series of stages of change

Behaviour is seldom changed as a result of providing facts, but results from a series of stages of change

The self-care philosophy encourages patients to be responsible for their own health and this opens up opportunities for pharmacists to influence health

The self-care philosophy encourages patients to be responsible for their own health and this opens up opportunities for pharmacists to influence health

The 1978 Alma Ata Declaration defines the content of primary care which should be universally accessible

The 1978 Alma Ata Declaration defines the content of primary care which should be universally accessible

Demographic, cultural and socioeconomic factors influence the use of health services

Demographic, cultural and socioeconomic factors influence the use of health services

Social support networks occur at different levels and all are important for the health of individuals

Social support networks occur at different levels and all are important for the health of individuals