Chapter 384 Emphysema and Overinflation

Pulmonary emphysema is distention of air spaces with irreversible disruption of the alveolar septa. It can be generalized or localized, involving part or all of a lung. Overinflation is distention with or without alveolar rupture and is often reversible. Compensatory overinflation can be acute or chronic and occurs in normally functioning pulmonary tissue when, for any reason, a sizable portion of the lung is removed or becomes partially or completely airless, which can occur with pneumonia, atelectasis, empyema, and pneumothorax. Obstructive overinflation results from partial obstruction of a bronchus or bronchiole, when it becomes more difficult for air to leave the alveoli than to enter; there is a gradual accumulation of air distal to the obstruction, the so-called bypass, ball valve, or check valve type of obstruction.

Localized Obstructive Overinflation

When a ball-valve type of obstruction partially occludes the main stem bronchus, the entire lung becomes overinflated; individual lobes are affected when the obstruction is in lobar bronchi. Segments or subsegments are affected when their individual bronchi are blocked. Localized obstructions that can be responsible for overinflation include foreign bodies and the inflammatory reaction to them, abnormally thick mucus (cystic fibrosis, Chapter 395), endobronchial tuberculosis or tuberculosis of the tracheobronchial lymph nodes (Chapter 207), and endobronchial or mediastinal tumors. When most or all of a lobe is involved, the percussion note is hyperresonant over the area, and the breath sounds are decreased in intensity. The distended lung can extend across the mediastinum into the opposite hemithorax. Under fluoroscopic scrutiny during exhalation, the overinflated area does not decrease, and the heart and the mediastinum shift to the opposite side because the unobstructed lung empties normally.

Unilateral Hyperlucent Lung

Unilateral hyperlucent lung can be associated with a variety of cardiac and pulmonary diseases of children, but in some patients, it occurs without demonstrable underlying active disease. More than half the cases follow one or more episodes of pneumonia; a rising titer to adenovirus (Chapter 254) has been documented in several children. This condition can follow bronchiolitis obliterans and can include obliterative vasculitis as well, accounting for the greatly diminished perfusion and vascular marking on the affected side.

Patients with unilateral hyperlucent lung can present with clinical manifestations of pneumonia, but in some patients the condition is discovered only when a chest radiograph is obtained for an unrelated reason. A few patients have hemoptysis. Physical findings can include hyperresonance and a small lung with the mediastinum shifted toward the more abnormal lung. This condition has been labeled Swyer-James or Macleod syndrome. The condition is thought to result from an insult to the lower respiratory tract. Some patients show a mediastinal shift away from the lesion with exhalation. CT scanning or bronchography can demonstrate bronchiectasis. In some patients, previous chest radiographs have been normal or have shown only an acute pneumonia, suggesting that a hyperlucent lung is an acquired lesion. No specific treatment is known; it may become less symptomatic with time. Indications as to which children would benefit from surgery remain controversial.

Congenital Lobar Emphysema

Congenital lobar emphysema (CLE) can result in severe respiratory distress in early infancy and can be caused by localized obstruction. Familial occurrence has been reported. In 50% of cases, a cause of CLE can be identified. Congenital deficiency of the bronchial cartilage, external compression by aberrant vessels, bronchial stenosis, redundant bronchial mucosal flaps, and kinking of the bronchus caused by herniation into the mediastinum have been described as leading to bronchial obstruction and subsequent CLE and commonly affects the left upper lobe.

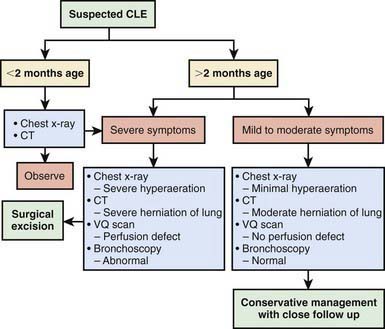

Clinical manifestations usually become apparent in the neonatal period but are delayed for as long as 5-6 mo in 5% of patients. Many cases are diagnosed by antenatal ultrasonography. Babies with prenatally diagnosed cases are not always symptomatic at birth. In some patients, CLE remains undiagnosed until school age or beyond. Signs range from mild tachypnea and wheeze to severe dyspnea with cyanosis. CLE can affect one or more lobes; it affects the upper and middle lobes, and the left upper lobe is the most common site. The affected lobe is essentially nonfunctional because of the overdistention, and atelectasis of the ipsilateral normal lung can ensue. With further distention, the mediastinum is shifted to the contralateral side, with impaired function seen as well (Fig. 384-1). A radiolucent lobe and a mediastinal shift are often revealed by radiographic examination. A CT scan can demonstrate the aberrant anatomy of the lesion, and MRI or MR angiography can demonstrate any vascular lesions, which might be causing extraluminal compression. Nuclear imaging studies are useful to demonstrate perfusion defects in the affected lobe. Figure 384-2 outlines evaluation of an infant presenting with suspected CLE. The differential diagnosis includes pneumonia with or without an effusion, pneumothorax, and cystic adenomatoid malformation.

Figure 384-1 Congenital left upper lobe emphysema. Note the extension of the emphysematous lobe into the left lower lobe and its displacement of the mediastinum toward the right.

Figure 384-2 Algorithm for evaluation and treatment of congenital lobar emphysema (CLE).

(Adapted from Senocak ME, Ciftci AO, et al: Congenital lobar emphysema: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations, J Pediatr Surg 34:1347–1351, 1999. Cited in Chao MC, Karamzadeh AM, Ahuja G: Congenital lobar emphysema: an otolaryngologic perspective, Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 69:553, 2005.)

Treatment by immediate surgery and excision of the lobe may be lifesaving when cyanosis and severe respiratory distress are present, but some patients respond to medical treatment. Selective intubation of the unaffected lung may be of value. Some children with apparent congenital lobar emphysema have reversible overinflation, without the classic alveolar septal rupture implied in the term emphysema. Bronchoscopy can reveal an endobronchial lesion.

Overinflation of All Three Lobes of the Right Lung

Overinflation of all three lobes of the right lung has been produced by anomalous location of the left pulmonary artery, which impinges on the right main stem bronchus. Hyperinflation also occurs in patients with the absent pulmonary valve type of tetralogy of Fallot (Chapter 424.1) and secondary aneurysmal dilatation of the pulmonary artery, which partially compresses the main stem bronchi. A number of neonates have lobar overinflation while being treated for hyaline membrane disease with assisted ventilation, suggesting an acquired cause. Medical management with selective intubation of the unaffected bronchus or high-frequency ventilation has occasionally been successful and lobectomy avoided.

Generalized Obstructive Overinflation

Acute generalized overinflation of the lung results from widespread involvement of the bronchioles and is usually reversible. It occurs more commonly in infants than in children and may be secondary to a number of clinical conditions, including asthma, cystic fibrosis, acute bronchiolitis, interstitial pneumonitis, atypical forms of acute laryngotracheobronchitis, aspiration of zinc stearate powder, chronic passive congestion secondary to a congenital cardiac lesion, and miliary tuberculosis.

Pathology

In chronic overinflation, many of the alveoli are ruptured and communicate with one another, producing distended saccules. Air can also enter the interstitial tissue (i.e., interstitial emphysema), resulting in pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax (Chapters 405 and 406).

Clinical Manifestations

Generalized obstructive overinflation is characterized by dyspnea, with difficulty in exhaling. The lungs become increasingly overdistended, and the chest remains expanded during exhalation. An increased respiratory rate and decreased respiratory excursion result from the overdistention of the alveoli and their inability to be emptied normally through the narrowed bronchioles. Air hunger is responsible for forced respiratory movements. Overaction of the accessory muscles of respiration results in retractions at the suprasternal notch, the supraclavicular spaces, the lower margin of the thorax, and the intercostal spaces. Unlike the flattened chest during inspiration and exhalation in cases of laryngeal obstruction, minimal reduction in the size of the overdistended chest during exhalation is observed. The percussion note is hyperresonant. On auscultation, the inspiratory phase is usually less prominent than the expiratory phase, which is prolonged and roughened. Fine or medium crackles may be heard. Cyanosis is more common in the severe cases.

Diagnosis

Radiographic and fluoroscopic examinations of the chest assist in establishing the diagnosis. Both leaves of the diaphragm are low and flattened, the ribs are farther apart than usual, and the lung fields are less dense. The movement of the diaphragm during exhalation is decreased, and the excursion of the low, flattened diaphragm in severe cases is barely discernible. The anteroposterior diameter of the chest is increased, and the sternum may be bowed outward.

Bullous Emphysema

Bullous emphysematous blebs or cysts (pneumatoceles) result from overdistention and rupture of alveoli during birth or shortly thereafter, or they may be sequelae of pneumonia and other infections. They have been observed in tuberculosis lesions during specific antibacterial therapy. These emphysematous areas presumably result from rupture of distended alveoli, forming a single or multiloculated cavity. The cysts can become large and might contain some fluid; an air-fluid level may be demonstrated on the radiograph (Fig. 384-3). The cysts should be differentiated from pulmonary abscesses. In most cases, the cysts disappear spontaneously within a few mo, although they can persist for a yr or more. Aspiration or surgery is not indicated except in cases of severe respiratory and cardiac compromise.

Figure 384-3 Increased transradiancy in the right lower zone. A large emphysematous bulla occupies the lower half of the right lung, and the apical changes are in keeping with previous tuberculosis.

(From Padley SPG, Hansell DM: Imaging techniques. In Albert RK, Spiro SG, Jett JR, editors: Clinical respiratory medicine, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2008, Mosby, Fig 1-48.)

Subcutaneous Emphysema

Subcutaneous emphysema results from any process that allows free air to enter into the subcutaneous tissue. The most common causes include pneumomediastinum or pneumothorax. Additionally, it can be a complication of fracture of the orbit, which permits free air to escape from the nasal sinuses. In the neck and thorax, subcutaneous emphysema can follow tracheotomy, deep ulceration in the pharyngeal region, esophageal wounds, or any perforating lesion of the larynx or trachea. It is occasionally a complication of thoracentesis, asthma, or abdominal surgery. Rarely, air is formed in the subcutaneous tissues by gas-producing bacteria.

Tenderness over the site of emphysema and a crepitant quality on palpation of the skin are classic manifestations. Subcutaneous emphysema is usually a self-limited process and requires no specific treatment. Minimization of activities that can increase airway pressure (cough, performance of high-pressure pulmonary function testing maneuvers) is recommended. Resolution occurs by resorption of subcutaneous air after elimination of its source. Rarely, dangerous compression of the trachea by air in the surrounding soft tissue requires surgical intervention.

Chao MC, Karamzadeh AM, Ahuja G. Congenital lobar emphysema: an otolaryngologic perspective. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:549-554.

Cumming GR, Macpherson RI, Chernick V. Unilateral hyperlucent lung syndrome in children. J Pediatr. 1971;78:250-260.

Horak E, Bodner J, Gassner I, et al. Congenital cystic lung disease: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Clin Pediatr. 2003;42:251-261.

Karnak I, Senocak ME, Ciftci AO, et al. Congenital lobar emphysema: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1347-1351.

Kim CK, Koh JY, Han YS, et al. Swyer-James syndrome with finger clubbing after severe measles infection. Pediatr Int. 2008;50:413-415.

McKenzie SA, Allison DJ, Singh MP, et al. Unilateral hyperlucent lung: the case for investigation. Thorax. 1980;35:745-750.

Mei-Zahar M, Konen O, Manson D, et al. Is congenital lobar emphysema a surgical disease? J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1058-1061.

Mura M, Zompatori M, Mussoni A, et al. Bullous emphysema versus diffuse emphysema: a functional and radiologic comparison. Respir Med. 2005;99:171-178.

Ulku R, Onat S, Ozçelik C. Congenital lobar emphysema: differential diagnosis and therapeutic approach. Pediatr Int. 2008;50:658-661.

Wong KS, Liu HP, Cheng KS, et al. Pathological case of the month. Primary bullous emphysema with spontaneous pneumothorax. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:845-856.