Chapter 1 Eyelids

Introduction

Anatomy

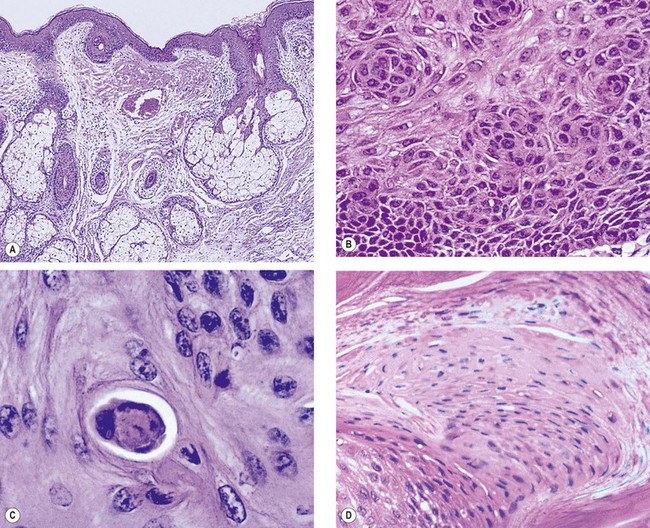

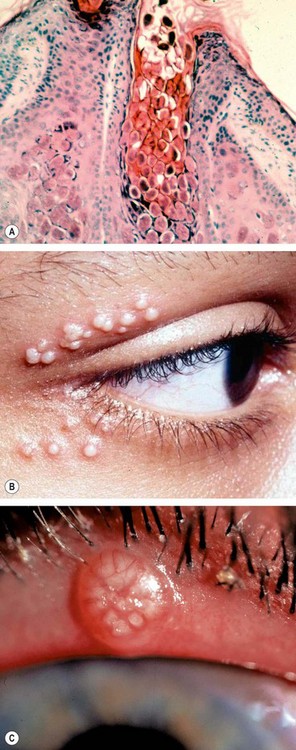

The skin consists of the epidermis, dermis and skin appendages (Fig. 1.1A), comprising a wide range of cell types capable of proliferation and neoplastic transformation. The range of cutaneous tumours is thus very extensive, ranging from common papillomas and basal cell carcinomas to much rarer skin appendage and soft tissue tumours in the dermis. Both benign and malignant tumours are classified according to their cell of origin as well as to their location in the epidermis, dermis or one of the skin appendages. This chapter considers only those of interest to ophthalmologists.

Fig. 1.1 Eyelid skin (A) Normal skin is composed of keratinized stratified epithelium that covers the surface; pilosebaceous elements are conspicuous in the dermis and a few blood vessels and sweat glands are also seen; (B) dysplasia with loss of cell polarity; (C) dyskeratosis – a non-surface epithelial cell producing keratin; (D) parakeratosis – retention of cell nuclei into the surface keratin layer

(Courtesy of J Harry – Fig. A; J Harry & G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2001 – Figs B, C and D)

Epidermis

The epidermis consists of four layers of keratin-producing cells (keratinocytes). It also contains melanocytes, Langerhans cells and Merkel cells. From superficial to deep, the layers of the epidermis are:

Dermis

The dermis is much thicker than the epidermis. It is composed of connective tissue and contains blood vessels, lymphatics and nerve fibres in addition to fibroblasts, macrophages and mast cells. Upward dermal projections (papillae) interdigitate with downward epidermal projections (rete ridges). In the eyelid the dermis lies on the orbicularis muscle. Skin appendages (adnexae) lie deep in the dermis or within the tarsal plates.

Terminology

Clinical

Histological

General considerations

Benign skin lesions are much more common and varied than malignancies.

Benign nodules and cysts

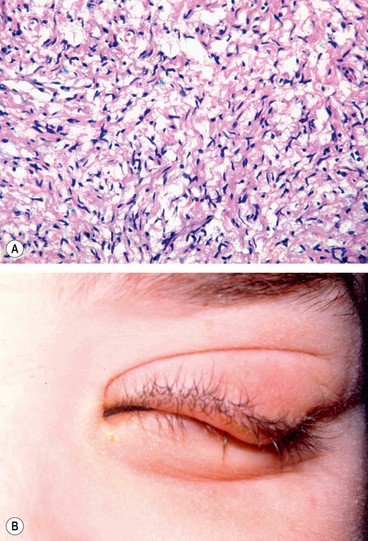

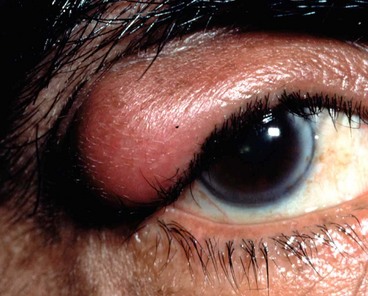

Chalazion

Pathogenesis

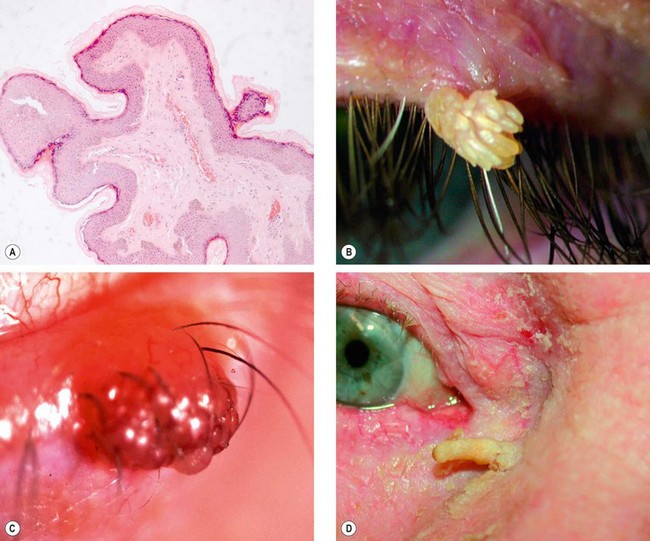

A chalazion (meibomian cyst) is a chronic, sterile, granulomatous inflammatory lesion caused by retained sebaceous secretion leaking from the meibomian or other sebaceous glands into adjacent stroma. A chalazion secondarily infected is referred to as an internal hordeolum.

Diagnosis

Fig. 1.2 Chalazion. (A) Histology shows a lipogranuloma; the large pale cells are epithelioid cells and the well-demarcated empty space contained fat which has been dissolved out during processing; (B) chalazion involving the lower lid; (C) conjuctival granuloma; (D) multiple chalazia in a patient with acne rosacea; (E) chalazion clamp

(Courtesy of J Harry and G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology, Butterworth-Heinemann 2001 – fig. A; S Tuft – fig. D; J Nerad, K Carter and M Alford, from Oculoplastic and Reconstructive Surgery, in Rapid Diagnosis in Ophthalmology, Mosby 2008 – fig. E)

Treatment

Treatment may not be required because at least a third of chalazia resolve spontaneously and an internal hordeolum may discharge and disappear. Persistent lesions may be treated as follows:

Other cysts

Benign epidermal tumours

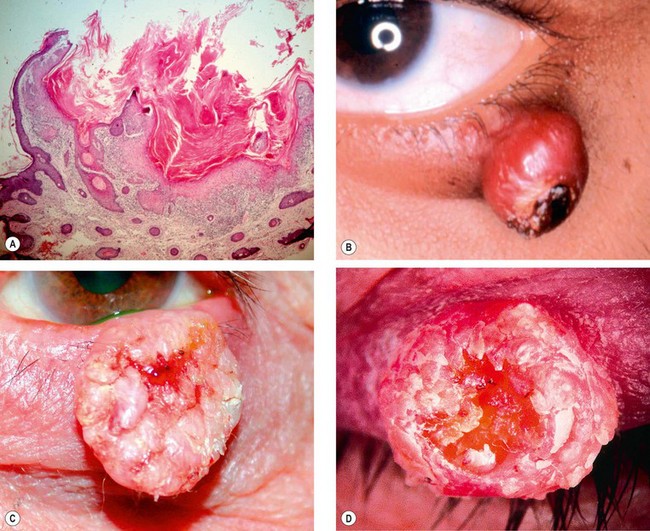

Squamous cell papilloma

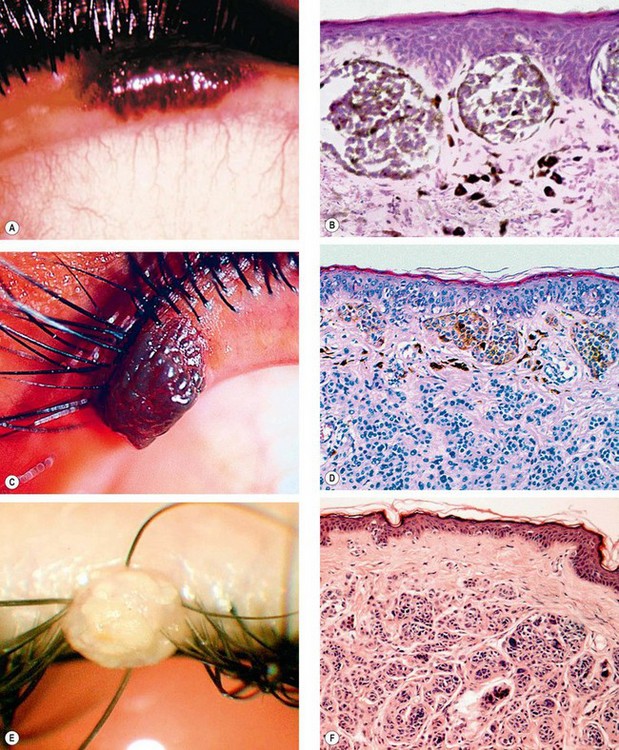

A squamous cell papilloma (fibroepithelial polyp) is a very common condition that has a variable clinical appearance but common histological features.

Fig. 1.5 Squamous cell papilloma. (A) Histology shows finger-like projections of fibrovascular connective tissue covered by irregular acanthotic and hyperkeratotic squamous epithelium; (B) skin tag; (C) sessile lesion with a raspberry-like surface; (D) hyperkeratotic filiform lesion

(Courtesy of J Harry – fig. A; A Pearson – fig. D)

Basal cell papilloma

Basal cell papilloma (seborrhoeic keratosis, seborrhoeic wart, senile verruca) is a common, slow-growing condition found on the face, trunk and extremities of elderly individuals.

Actinic keratosis

Actinic (solar, senile) keratosis is a common slow-growing lesion that rarely develops on the eyelids. It typically affects elderly, fair-skinned individuals who have been exposed to excessive sunlight and most frequently occurs on the forehead and backs of the hands. It has a low potential for transformation into squamous cell carcinoma.

Benign pigmented lesions

Freckle (ephelis)

A brown macule due to increased melanin in the epidermal basal layer, generally in sunlight-exposed areas (Fig. 1.8).

Congenital melanocytic naevus

Congenital naevi are uncommon and histologically resemble their acquired counterparts. Large lesions have potential for malignant transformation of up to 15%.

Acquired melanocytic naevus

Fig. 1.10 Acquired melanocytic naevus. (A) Junctional naevus; (B) histology shows heavily pigmented naevus cells at the epidermal/dermal junction.

(C) Compound naevus; (D) histology shows naevus cells both at the epidermal/dermal junction and within the dermis. (E) Intradermal naevus; (F) histology shows naevus cells within the dermis separated by a clear zone from the epidermis

(Courtesy of J Harry – figs B, D and F)

Benign adnexal tumours

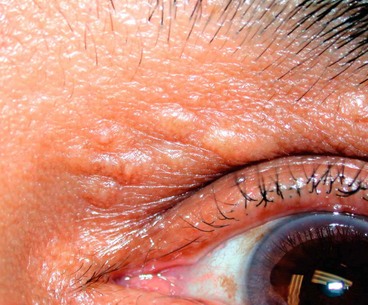

Syringoma

Syringomas are benign proliferations arising from eccrine sweat glands. They are characterized by small papules that are often multiple and bilateral (Fig. 1.11).

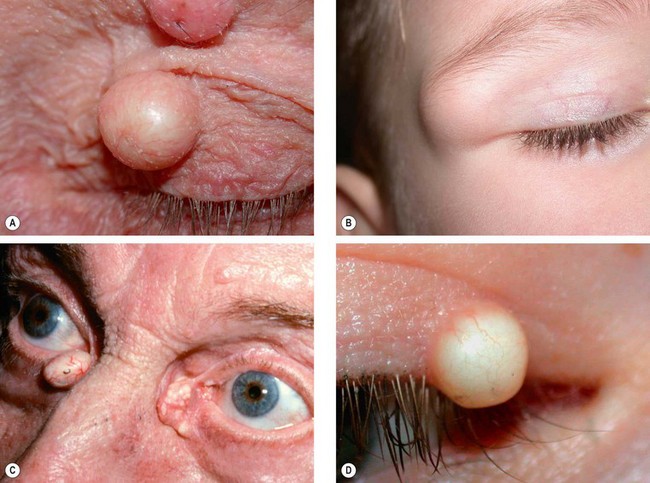

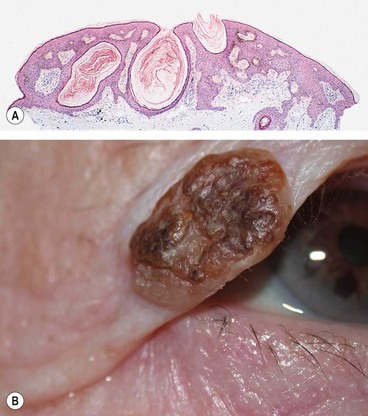

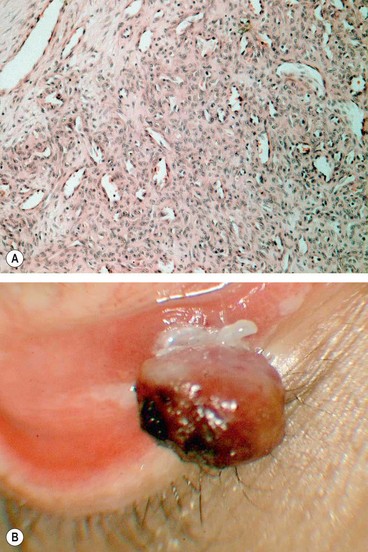

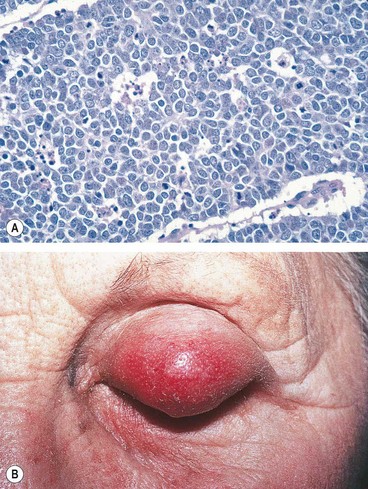

Pilomatricoma

Pilomatricoma (pilomatrixoma, calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe) is derived from the germinal matrix cells of the hair bulb. It affects children and young adults and is more common in females. It is the commonest hair follicle proliferation seen by ophthalmologists. Malignant change is rare.

Fig. 1.12 Pilomatricoma. (A) Histology shows viable basophilic cells to the right and degenerate shadow cells to the left; (B) clinical appearance

(Courtesy of J Harry and G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology, Butterworth-Heinemann 2001 – fig. A; J Krachmer, M Mannis and E Holland, from Cornea, Elsevier 2005 – fig. B)

Other less common hair follicle proliferations include trichofolliculoma, trichoepithelioma and trichilemmoma.

Miscellaneous benign tumours

Capillary haemangioma

Capillary haemangioma (strawberry naevus), although rare, is one of the most common tumours of infancy and presents shortly after birth. The female to male ratio is 3:1. Eyelid haemangiomas have a predilection for the upper lid and may have orbital extensions. Occasionally the lesion may also involve the skin of the face and some patients have strawberry naevi on other parts of the body. It is important to be aware of the association between multiple cutaneous lesions and visceral haemangiomas.

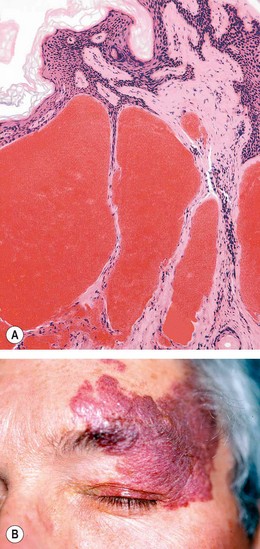

Port-wine stain

A port-wine stain (naevus flammeus, cavernous haemangioma) is a rare congenital, subcutaneous lesion consisting of large ectatic vessels of varying calibre. It most frequently occurs on the face and is usually unilateral and segmental but occasionally may be bilateral. Some patients have associated Sturge–Weber syndrome (see below).

Cutaneous features

Sturge–Weber syndrome

Sturge–Weber syndrome (encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis) is a congenital, sporadic phacomatosis.

Pyogenic granuloma

A pyogenic granuloma is a fast-growing vascularized proliferation of granulation tissue which is usually antedated by surgery, trauma or infection, although some cases are idiopathic.

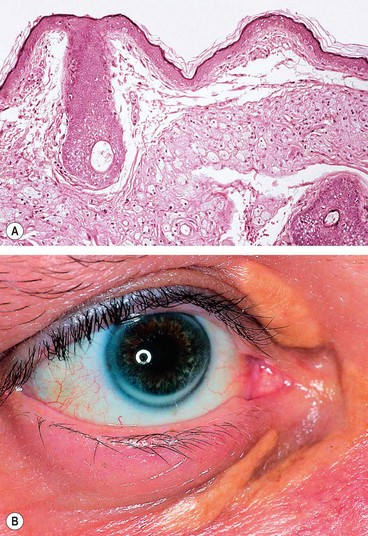

Xanthelasma

Xanthelasma is a common, frequently bilateral condition which is usually found in middle-aged and elderly individuals. Xanthelasma (and corneal arcus) (see Fig. 1.18B) can be associated with increased levels of serum cholesterol, especially in young males.

Neurofibroma

Plexiform neurofibromas typically affect children who also have neurofibromatosis type I (NF1). Solitary neurofibromas typically occur in adults, 25% of whom have NF1.

Malignant tumours

Rare predisposing conditions

Young patients who suffer from one of the following conditions may develop eyelid malignancies:

Basal cell carcinoma

General features

BCC is the most common human malignancy and most frequently affects elderly patients. The most important risk factors are fair skin, inability to tan and chronic exposure to sunlight. Ninety per cent of cases occur in the head and neck and about 10% of these involve the eyelid. BCC is by far the most common malignant eyelid tumour, accounting for 90% of all cases. It most frequently arises from the lower eyelid, followed in relative frequency by the medial canthus, upper eyelid and lateral canthus. The tumour is slow-growing and locally invasive but non-metastasizing. Tumours located near the medial canthus are more prone to invade the orbit and sinuses, are more difficult to manage than those arising elsewhere and carry the greatest risk of recurrence. Tumours that recur following incomplete treatment tend to be more aggressive.

Histology

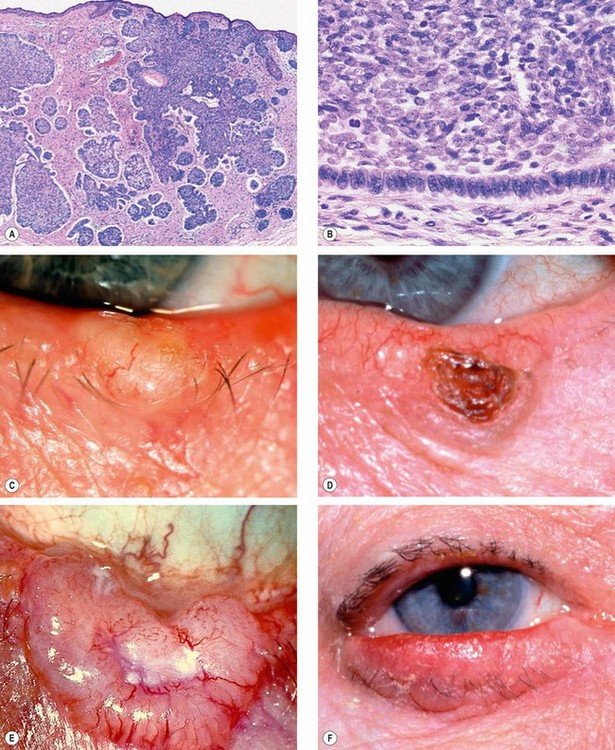

The tumour arises from the cells that form the basal layer of the epidermis. The cells proliferate downwards (Fig. 1.21A) and characteristically exhibit palisading at the periphery of a tumour lobule of cells (Fig. 1.21B). Squamous differentiation with the production of keratin results in a hyperkeratotic type of BCC. There can also be sebaceous and adenoid differentiation while the growth of elongated strands and islands of cells embedded in a dense fibrous stroma results in a sclerosing (morphoeic) type of tumour.

Fig. 1.21 Basal cell carcinoma. (A) Histology shows downward proliferation of lobules of basal (purple) cells; (B) histology shows palisading of cells at the periphery of a tumour lobule; (C) nodular tumour; (D) rodent ulcer; (E) large rodent ulcer; (F) sclerosing tumour

(Courtesy of J Harry – figs A and B)

Clinical types

The main clinical features of epidermal cell malignancy are ulceration, lack of tenderness, induration, irregular borders and destruction of lid margin architecture.

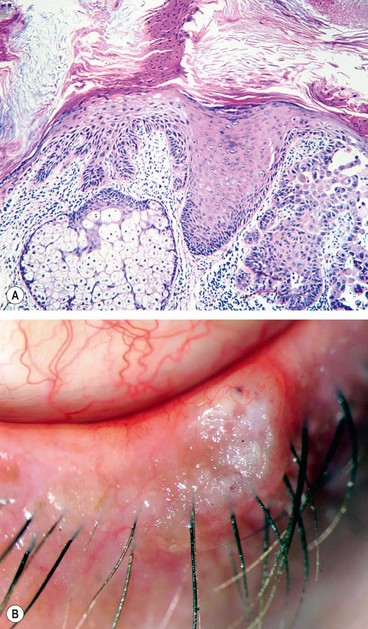

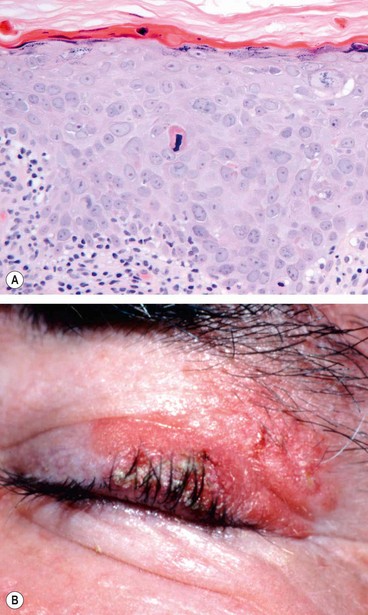

Squamous cell carcinoma

General features

SCC is a much less common, but typically more aggressive tumour than BCC with metastasis to regional lymph nodes in about 20% of cases. Careful surveillance of regional lymph nodes is therefore an important aspect of initial management. The tumour may also exhibit perineural spread to the intracranial cavity via the orbit. SCC accounts for 5–10% of eyelid malignancies and may arise de novo or from pre-existing actinic keratosis or carcinoma in situ (Bowen disease, intraepidermal carcinoma; Fig. 1.22). Immunocompromised patients such as those with AIDS or following renal transplants are at increased risk. The tumour has a predilection for the lower eyelid and the lid margin. It occurs most commonly in elderly individuals with a fair complexion and a history of chronic sun exposure. The diagnosis of SCC may be difficult because certain ostensibly benign lesions such as keratoacanthoma and cutaneous horn may reveal histological evidence of invasive SCC at deeper levels of sectioning.

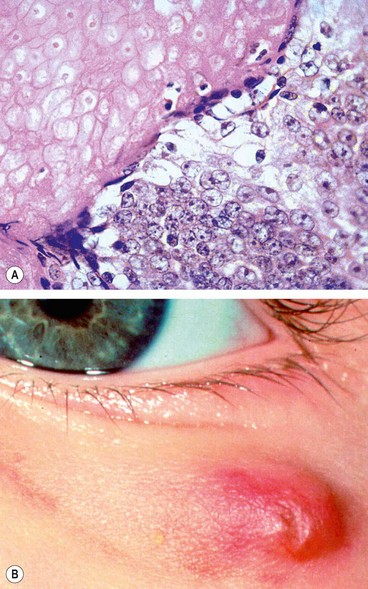

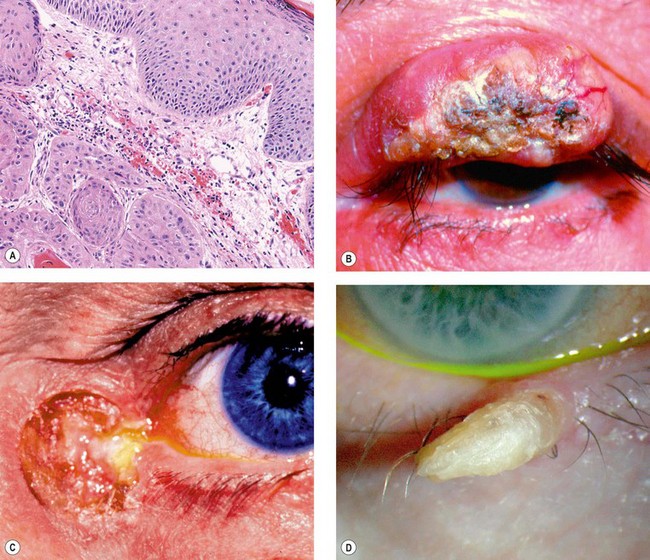

Histology

The tumour arises from the squamous cell layer of the epidermis. It is composed of variable-sized groups of atypical epithelial cells with prominent nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm within the dermis (Fig. 1.23A). Well-differentiated tumours may show characteristic keratin ‘pearls’ and intercellular bridges (desmosomes).

Fig. 1.23 Squamous cell carcinoma. (A) Histology shows acanthotic squamous epithelium and eosinophilic (pink) islands of dysplastic squamous epithelium within the dermis; (B) nodular tumour with surface keratosis; (C) ulcerating tumour; (D) cutaneous horn

(Courtesy of L Horton – fig. A; A Singh, from Clinical Ophthalmic Oncology, Saunders 2007 – fig. B; H Frank – fig. C; S Farley, T Cole and L Rimmer – fig. D)

Clinical types

The clinical types are variable and there are no pathognomonic characteristics. The tumour may be indistinguishable clinically from a BCC but surface vascularization is usually absent, growth is more rapid and hyperkeratosis is more often present.

Keratoacanthoma

Keratoacanthoma is a rare tumour that usually occurs in fair-skinned individuals with a history of chronic sun exposure. It is found more frequently than would be expected by chance in patients on immunosuppressive therapy. Histopathologically, keratoacanthoma is regarded as part of the spectrum of SCC.

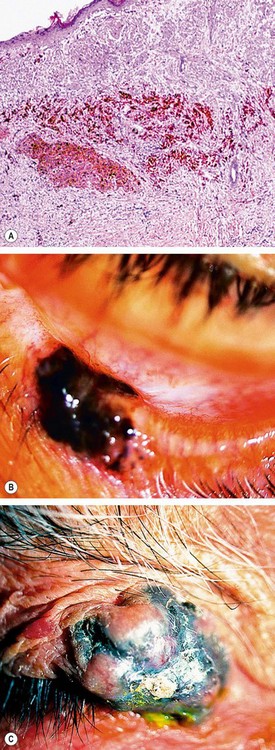

Sebaceous gland carcinoma

General features

Sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC) is a very rare slowly-growing tumour which most frequently affects the elderly, with a predisposition for females. It usually arises from the meibomian glands, although on occasion it may arise from the glands of Zeis or from sebaceous glands in the caruncle. In contrast to BCC and SCC, the tumour occurs more commonly on the upper eyelid where meibomian glands are more numerous. In about 5% of cases there is simultaneous involvement of both lids on one side, probably due to intraepithelial spread or to spontaneous development of multiple primaries. The clinical diagnosis of SGC is frequently difficult because, in its early stages, external signs of malignancy may be subtle so that the tumour may resemble a chalazion or blepharitis. However, the presence of yellowish material within the tumour is highly suggestive of SGC. Because of frequent difficulties in diagnosis and delay in treatment, the overall mortality rate is about 5–10%. Adverse prognostic features include upper lid involvement, tumour size of 10 mm or more and duration of symptoms of over 6 months. SGC that arises from the glands of Zeis is thought to have a more favourable prognosis.

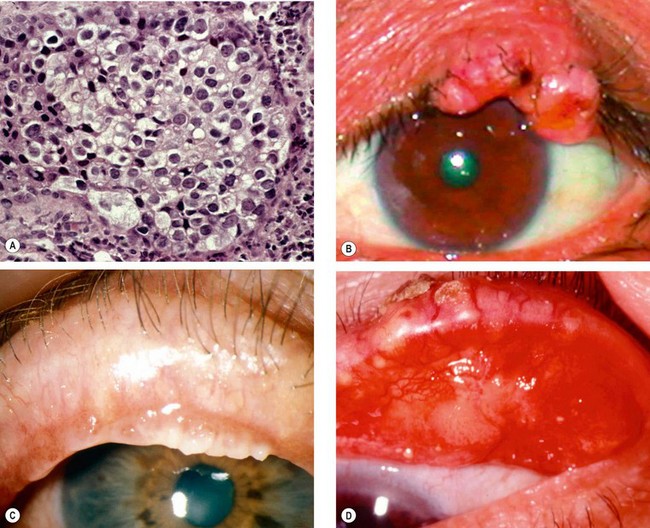

Histology

The tumour consists of lobules of cells with pale foamy vacuolated lipid-containing cytoplasm and large hyperchromatic nuclei (Fig. 1.25A).

Fig. 1.25 Sebaceous gland carcinoma. (A) Histology shows cells with large hyperchromatic nuclei and vacuolated cytoplasm; (B) nodular tumour; (C) spreading tumour; (D) pagetoid spread

(Courtesy of A Garner – fig. A; A Singh, from Clinical Ophthalmic Oncology, Saunders 2007 – fig. B; S Tuft – fig. C; H Frank fig. D)

Clinical types

Although SGC does not have a characteristic clinical appearance it may present with the following:

Lentigo maligna and melanoma

Melanoma rarely develops on the eyelids but is potentially lethal. Although pigmentation is a hallmark of skin melanomas, half of lid melanomas are non-pigmented and this may give rise to diagnostic difficulties. Features suggestive of melanoma include recent onset of a pigmented lesion, change in an existing pigmented lesion, irregular margins, asymmetrical shape, colour change or presence of multiple colours, and diameter greater than 6 mm in diameter.

Lentigo maligna

Lentigo maligna (melanoma in situ, intraepidermal melanoma and Hutchinson freckle) is an uncommon condition that develops in sun-damaged skin in elderly individuals. Malignant change may occur, with infiltration of the dermis.

Melanoma

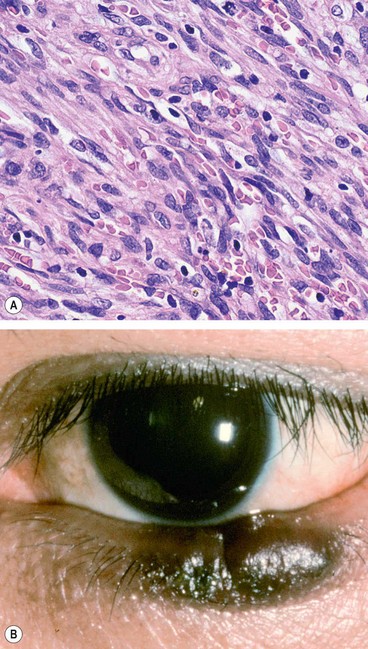

Merkel cell carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma is a fast-growing tumour which typically affects the elderly. Although Merkel cells lie within the epidermis, the tumour appears to arise from the dermis. Its rarity may lead to difficulty in diagnosis and delay in treatment. The tumour is highly malignant and 50% of patients have metastatic spread at presentation.

Kaposi sarcoma

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular tumour which typically affects patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Many patients have advanced systemic disease although in some instances the tumour may be the only clinical manifestation of HIV infection.

Treatment of malignant tumours

Biopsy

The two types of biopsy are (a) incisional, using a blade or a biopsy punch, in which only part of the lesion is removed to allow histological diagnosis, and (b) excisional, in which the entire lesion is removed and a histological diagnosis made; the latter may be:

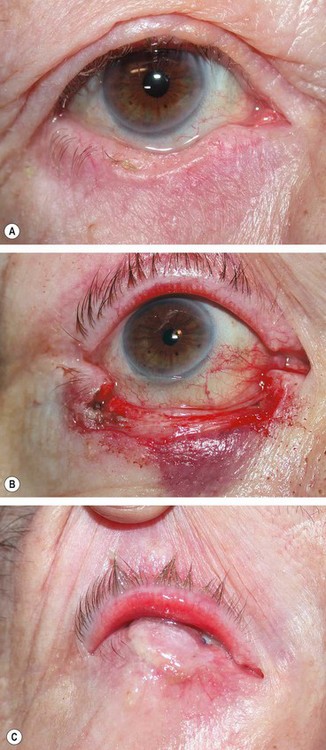

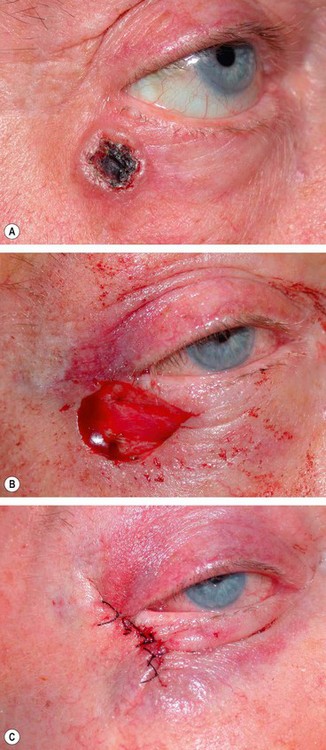

Surgical excision

Surgical excision aims to remove the entire tumour with preservation of as much normal tissue as possible. Smaller tumours can be removed via an excision biopsy and the defect closed directly, whilst awaiting histological confirmation of complete clearance. Most small BCCs can be cured by excision of the tumour together with a 2–4 mm margin of clinically normal tissue. More radical surgical excision is required for large BCC and aggressive tumours such as SCC, SGC and melanoma. It may not be possible to close the defect at the time of initial removal, but it is necessary to ensure complete clearance of tumour prior to undertaking any reconstruction. Rapid processing of paraffin-embedded specimens can reduce the interval to confirmation of histological clearance but still requires closure as a separate procedure. Faster confirmation can be achieved using either frozen-section control or micrographic surgery, and reconstruction can then take place on the same day.

Reconstruction

The technique of reconstruction depends on the extent of tissue removed and whether this is full- or partial-thickness. It is important to reconstruct both anterior and posterior lamellae. If one of the lamellae has been sacrificed during excision of the tumour, it must be reconstructed with similar tissue. Anterior lamellar defects may be closed directly or with a local flap or skin graft. Full-thickness defects may be repaired as follows:

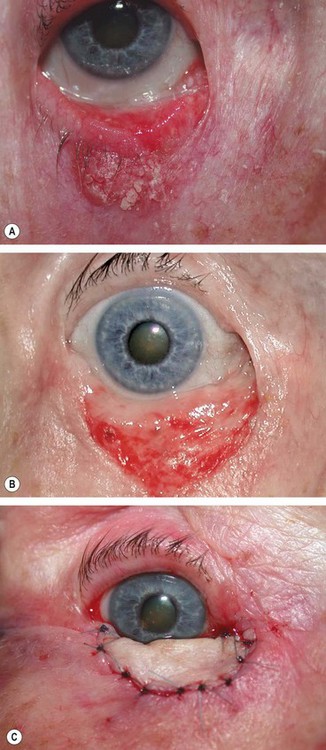

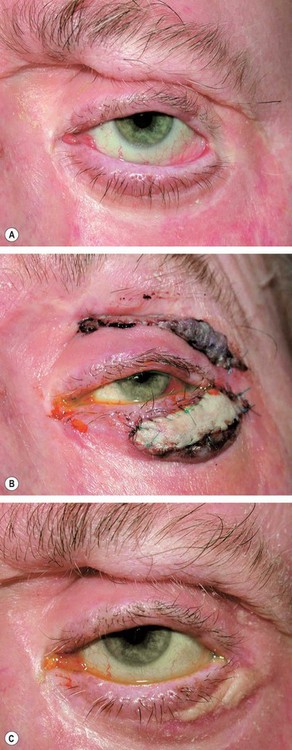

Fig. 1.30 Direct closure. (A) Pre-operative appearance of a basal cell carcinoma; (B) appearance following excision; (C) direct closure of defect

(Courtesy of A Pearson)

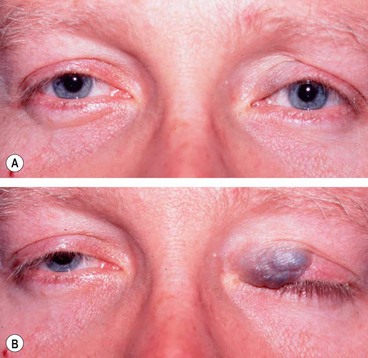

Fig. 1.31 Tenzel flap. (A) Pre-operative appearance; (B) appearance following excision; (C) appearance following closure of the flap

(Courtesy of A Pearson)

Laissez-faire

Full reconstruction of the defect created by tumour removal may not always be required. In the laissez-faire approach the wound edges are approximated as far as possible and the defect is allowed to granulate and heal by secondary intention. Even large defects can often achieve a satisfactory outcome with time.

Radiotherapy

The recurrence rate following irradiation is higher than after surgery, and radiotherapy does not allow histological confirmation of tumour eradication. Recurrences following radiotherapy are difficult to treat surgically because of the poor healing properties of irradiated tissue.

Many of these complications can be avoided if the globe is protected by a special shield during irradiation.

Disorders of lashes

Anatomy

The lashes (cilia) are slightly more numerous in the upper (approximately 100) than in the lower lid. The lash roots lie against the anterior surface of the tarsus. The cilia pass between the orbicularis oculi and the muscle of Riolan, exiting the skin at the anterior lid margin and curve away from the globe. Scarring of the tarsal plate and conjunctiva can alter their position and direction. Following intense inflammation lashes may grow abnormally from meibomian gland openings (distichiasis).

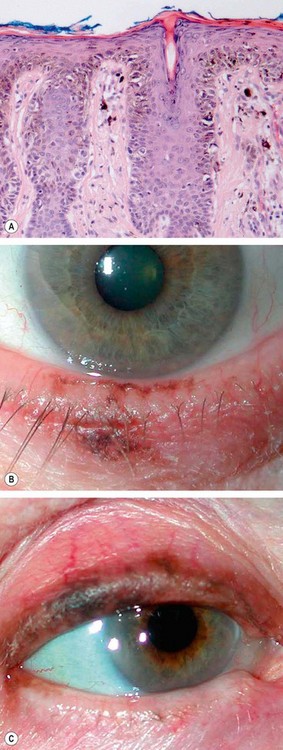

Trichiasis

Trichiasis is a very common acquired condition which may occur in isolation or as a result of scarring of the lid margin secondary to chronic blepharitis and herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Trichiasis should not be mistaken for pseudotrichiasis secondary to entropion when in some cases the in-turning of the eyelid may be intermittent and the condition may be mistaken for true trichiasis and inappropriately treated.

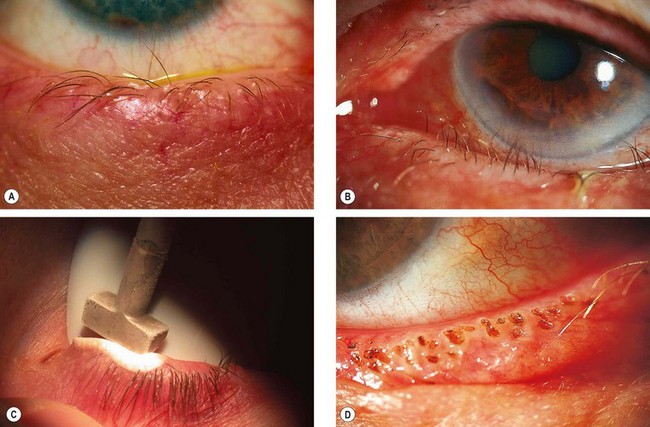

Signs

Trichiasis is characterized by posterior misdirection of lashes arising from normal sites of origin (Fig. 1.34A and B). Trauma to the corneal epithelium may cause punctate epithelial erosions, with ocular irritation worsened by blinking. Corneal ulceration and pannus formation may occur in severe long-standing cases.

Treatment

Congenital distichiasis

Congenital distichiasis is a rare condition that occurs when a primary epithelial germ cell destined to differentiate into a specialized sebaceous gland (meibomian gland) of the tarsus develops into a complete pilosebaceous unit. The condition is frequently inherited in an AD manner with high penetrance but variable expressivity. The majority of patients also manifest primary lymphoedema of the legs (lymphoedema–distichiasis syndrome).

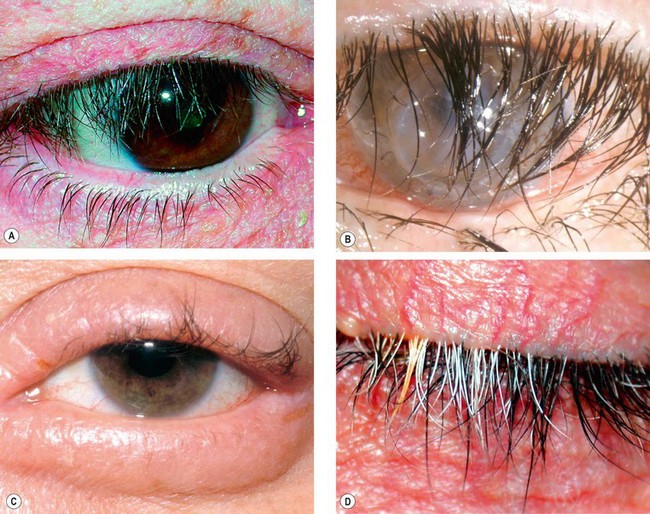

Acquired distichiasis

Acquired distichiasis (metaplastic lashes) is caused by metaplasia and dedifferentiation of the meibomian glands to become hair follicles. The most important cause is late stage cicatrizing conjunctivitis associated with chemical injury, Stevens–Johnson syndrome and ocular cicatricial pemphigoid.

Eyelash ptosis

Eyelash ptosis is a downward sagging of upper eyelid lashes (Fig. 1.37A). The condition may be idiopathic or associated with floppy eyelid syndrome, dermatochalasis with anterior lamellar slip or long-standing facial palsy.

Trichomegaly

Trichomegaly is excessive eyelash growth (Fig. 1.37B); the main causes are listed in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Causes of trichomegaly

Madarosis

Madarosis is a decrease in the number of lashes (Fig. 1.37C); the main causes are shown in Table 1.2

Poliosis

Poliosis is a premature localized whitening of hair, which may involve the lashes and eyebrows (Fig. 1.37D); the main causes are shown in Table 1.3.

Allergic disorders

Acute allergic oedema

Acute allergic oedema is usually caused by pollen or by insect bites.

Contact dermatitis

Contact dermatitis is an inflammatory response that usually follows exposure to a medication or preservative, cosmetics or metals. An irritant can also cause a non-allergic toxic dermatitis. The individual is sensitized on first exposure and develops an immune reaction on further exposure. Reaction is mediated by a delayed type IV hypersensitivity response.

Atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (eczema) is a very common idiopathic condition, typically associated with asthma and hay fever. Eyelid involvement is relatively infrequent but when present is invariably associated with generalized dermatitis.

Bacterial infections

External hordeolum

An external hordeolum (stye) is an acute staphylococcal abscess of a lash follicle and its associated gland of Zeis. It is more common in children and young adults.

Impetigo

Impetigo is an uncommon superficial skin infection caused by S. aureus or S. pyogenes which most frequently affects children. Involvement of the eyelids is usually associated with painful infection of the face.

Erysipelas

Erysipelas (St Anthony’s fire) is an uncommon, acute subcutaneous spreading cellulitis, usually caused by S. pyogenes through a site of minor skin trauma.

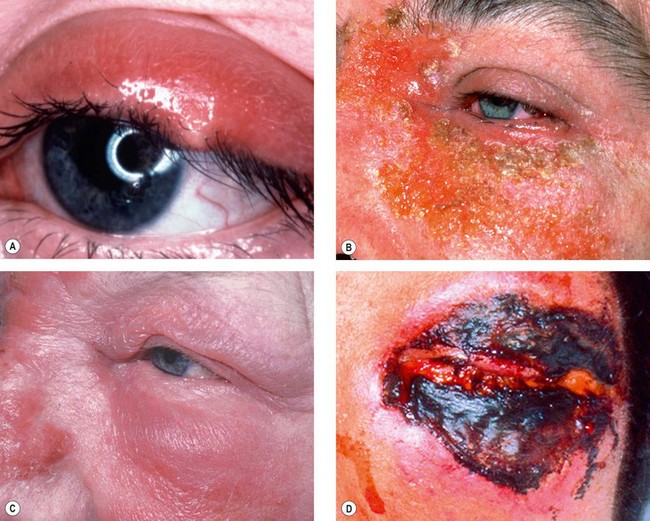

Necrotizing fasciitis

Necrotizing fasciitis is an extremely rare rapidly progressive necrosis initially involving subcutaneous soft tissues and later the skin. It is usually caused by S. pyogenes and occasionally S. aureus. The most frequent sites of involvement are the extremities, trunk and perineum, as well as postoperative wound sites. Unless treatment is early and appropriate death may result. Periocular infection is rare and may be secondary to trauma or surgery.

Viral infections

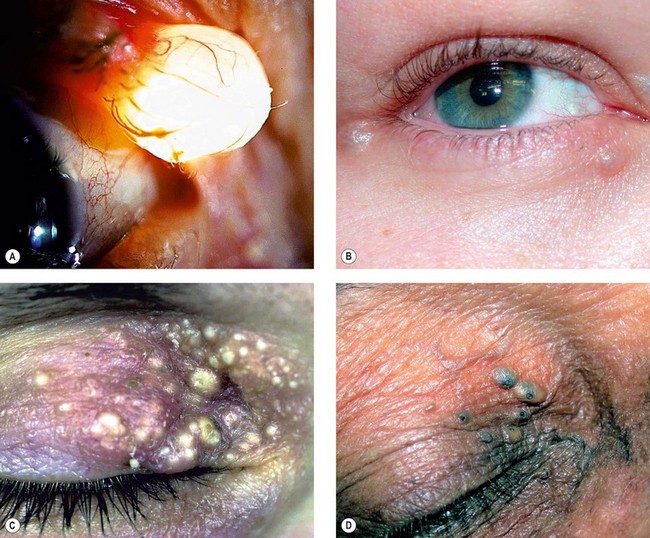

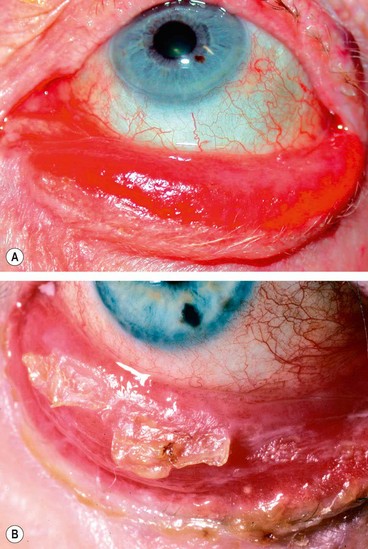

Molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum is a skin infection caused by a human specific double-stranded DNA poxvirus which typically affects otherwise healthy children, with a peak incidence between 2 and 4 years. Transmission is by contact and subsequently by autoinoculation. Multiple, and occasionally confluent, lesions may develop in immunocompromised patients. A distribution in the chin-strap region is common in HIV-positive individuals.

Fig. 1.40 Molluscum contagiosum. (A) Histology shows lobules of hyperplastic epidermis and a pit containing intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies which are small and eosinophilic near the surface and larger and basophilic more deeply; (B) multiple molluscum nodules; (C) lid margin nodule

(Courtesy of A Garner – fig. A; N Rogers – fig. B)

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) is a common, unilateral infection caused by varicella-zoster virus. It typically affects the elderly but may occur at an earlier age. It tends to be more severe in immunocompromised individuals.

Blepharitis

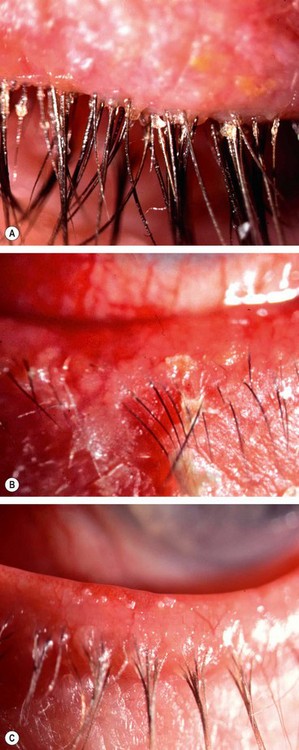

Chronic anterior blepharitis

Chronic marginal blepharitis is a very common cause of ocular discomfort and irritation. Involvement is usually bilateral and symmetrical. Blepharitis may be subdivided into anterior and posterior although there is considerable overlap and both are often present. The poor correlation between symptoms and signs, the uncertain aetiology and mechanisms of the disease process all conspire to make management difficult.

Pathogenesis

Anterior blepharitis affects the area surrounding the bases of the eyelashes and may be staphylococcal or seborrhoeic. The former is thought to be the result of an abnormal cell mediated response to components of the cell wall of S. aureus which may also be responsible for the red eyes and the peripheral corneal infiltrates seen in some patients. Seborrhoeic blepharitis is often associated with generalized seborrhoeic dermatitis that may involve the scalp, nasolabial folds, behind the ears, and the sternum. Because of the intimate relationship between the lids and ocular surface, chronic blepharitis may cause secondary inflammatory and mechanical changes in the conjunctiva and cornea.

Diagnosis

Treatment

There is little evidence to support any particular treatment protocol for anterior blepharitis. Patients should be advised that a permanent cure is unlikely, but control of symptoms is usually possible.

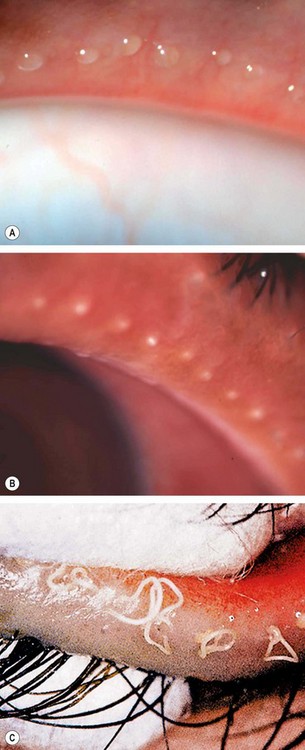

Chronic posterior blepharitis

Pathogenesis

Posterior blepharitis is caused by meibomian gland dysfunction and alterations in meibomian gland secretions. Bacterial lipases may result in the formation of free fatty acids. This increases the melting point of the meibum preventing its expression from the glands, contributing to ocular surface irritation and possibly enabling growth of S. aureus. Loss of the tear film phospholipids that act as surfactants results in increased tear evaporation and osmolarity, and an unstable tear film.

Diagnosis

There is poor correlation between the severity of symptoms and the clinical signs.

Treatment

It is very important to inform the patient that a cure is unlikely. Although remission may be achieved recurrence is usual, particularly when treatment is stopped prematurely.

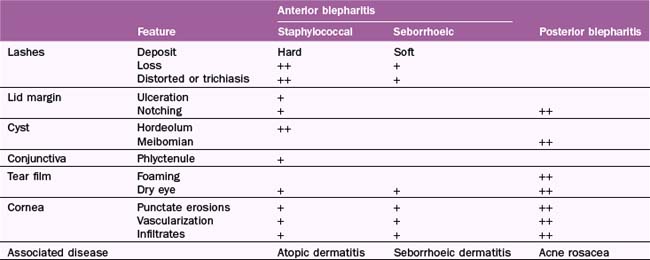

Associations of chronic blepharitis

Table 1.4 summarizes the features of chronic blephoritis.

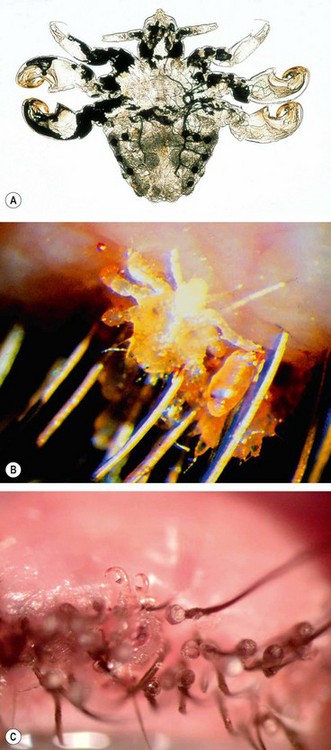

Phthiriasis palpebrarum

Angular blepharitis

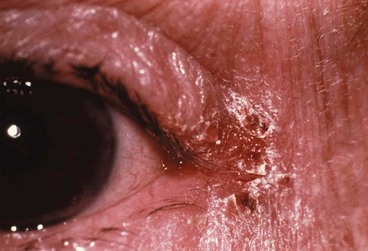

Childhood blepharokeratoconjunctivitis

Childhood blepharokeratoconjunctivitis is a poorly defined condition which tends to be more severe in Asian and Middle Eastern populations.

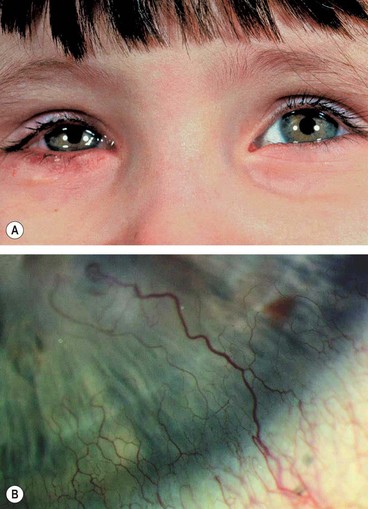

Ptosis

Classification

Ptosis is an abnormally low position of the upper lid which may be congenital or acquired.

Clinical evaluation

History

The age at onset of ptosis and its duration will usually distinguish congenital from acquired cases. If the history is ambiguous, old photographs may be helpful. It is also important to enquire about symptoms of possible underlying systemic disease, such as associated diplopia, variability of ptosis during the day and excessive fatigue.

Pseudoptosis

A false impression of ptosis may be caused by the following:

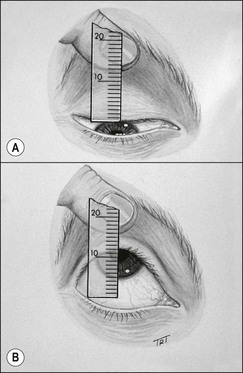

Measurements

Associated signs

Simple congenital ptosis

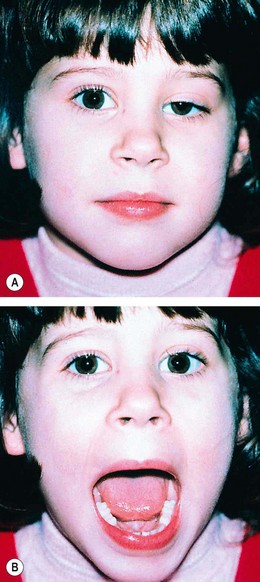

Marcus Gunn jaw-winking syndrome

About 5% of all cases of congenital ptosis manifest the Marcus Gunn jaw-winking phenomenon. The vast majority are unilateral. Although the exact aetiology is unclear, it has been postulated that a branch of the mandibular division of the 5th cranial nerve is misdirected to the levator muscle.

3rd nerve misdirection syndromes

3rd nerve misdirection syndromes may be congenital, or more frequently may follow acquired 3rd nerve palsies. Ptosis may also occur following aberrant facial nerve regeneration.

Involutional ptosis

Involutional ptosis is an age-related condition caused by dehiscence, disinsertion or stretching of the levator aponeurosis, restricting transmission of force from a normal levator muscle to the upper lid. Due to fatigue of the Müller muscle it frequently worsens towards the end of the day, so that it can sometimes be confused with myasthenic ptosis.

Mechanical ptosis

Mechanical ptosis is the result of impaired mobility of the upper lid. It may be caused by dermatochalasis, large tumours such as neurofibromas (Fig. 1.56), heavy scar tissue, severe oedema and anterior orbital lesions.

Surgery

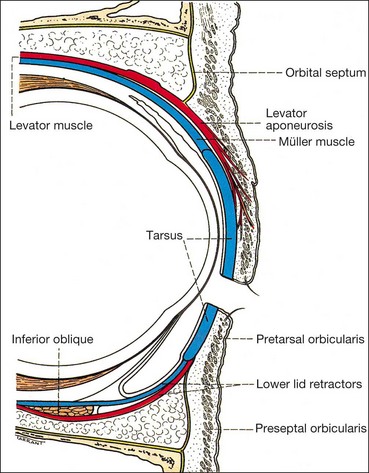

Anatomy

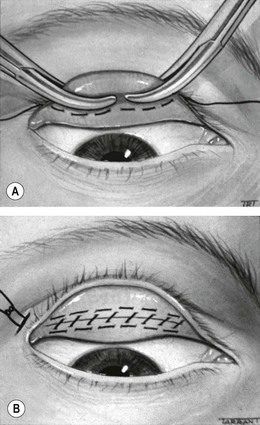

Conjunctiva–Müller resection

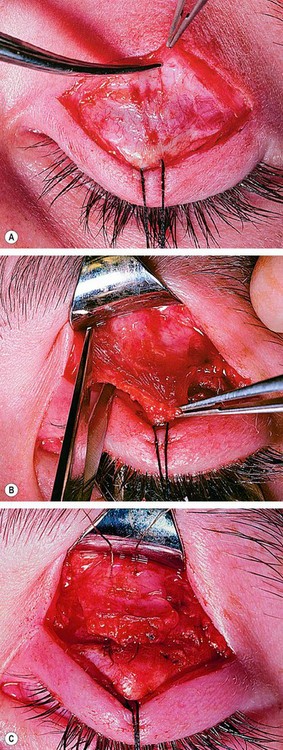

Levator resection

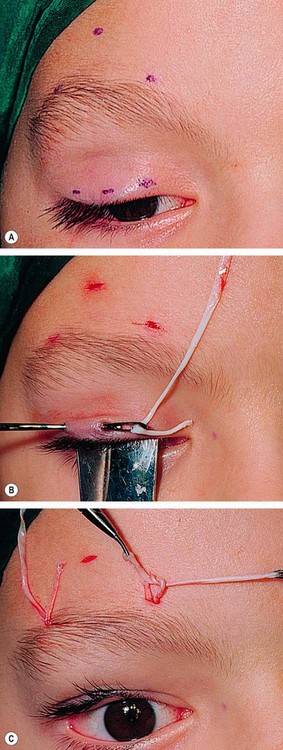

Brow suspension

Ectropion

Involutional ectropion

Involutional (age-related) ectropion affects the lower lid of elderly patients. It results in epiphora and in long-standing cases the tarsal conjunctiva may become chronically inflamed, thickened and keratinized (Fig. 1.61).

Fig. 1.61 (A) Severe long-standing involutional ectropion; (B) keratinization of the tarsal conjunctiva

(Courtesy of R Bates– fig. B)

Pathogenesis

The following age-related changes are contributory:

Treatment

The methods of repair depend on the underlying aetiology and the predominant location of the ectropion as follows:

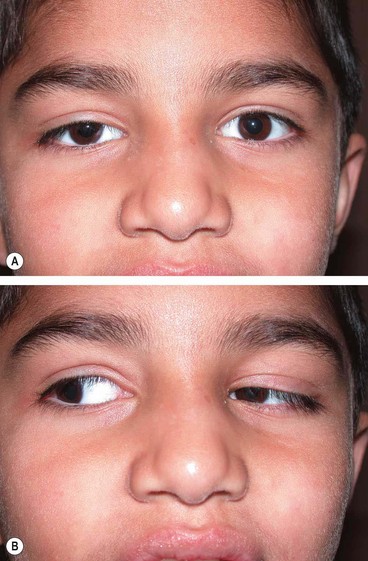

Cicatricial ectropion

Cicatricial ectropion is caused by scarring or contracture of the skin and underlying tissues which pulls the eyelid away from the globe (Fig. 1.64A). If the skin is pushed up over the orbital margin with a finger the ectropion will be relieved and the lids will close. Opening the mouth tends to accentuate the ectropion. Depending on the cause, both lids may be involved and the defect may be local (e.g. trauma) or general (e.g. burns, dermatitis and ichthyosis).

Paralytic ectropion

Paralytic ectropion is caused by ipsilateral facial nerve palsy (Fig. 1.65A) and is associated with retraction of the upper and lower lids and brow ptosis; the latter may mimic narrowing of the palpebral aperture.

Fig. 1.65 Paralytic ectropion. (A) Left facial palsy and severe ectropion; (B) lagophthalmos

(Courtesy of A Pearson)

Temporary treatment

Temporary treatment is aimed at protecting the cornea in anticipation of spontaneous recovery of facial nerve function.

Permanent treatment

Permanent treatment should be considered when there is irreversible damage to the facial nerve as may occur following removal of an acoustic neuroma, or when no further improvement is likely after Bell palsy. Treatment is aimed at reducing the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the palpebral aperture by one of the following procedures:

Fig. 1.66 Permanent treatment of paralytic ectropion. (A) Medial canthoplasty; (B) lateral canthal sling – refashioned canthal tendon from the lower lid is passed through a button hole in the tendon from the upper lid

(Courtesy of AG Tyers and JRO Collin, from Colour Atlas of Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery, Butterworth-Heinemann 2001)

Mechanical ectropion

Mechanical ectropion is caused by tumours on or near the lid margin (Fig. 1.67) which mechanically evert the lid. Treatment involves removal of the cause if possible, and correction of significant horizontal lid laxity.

Entropion

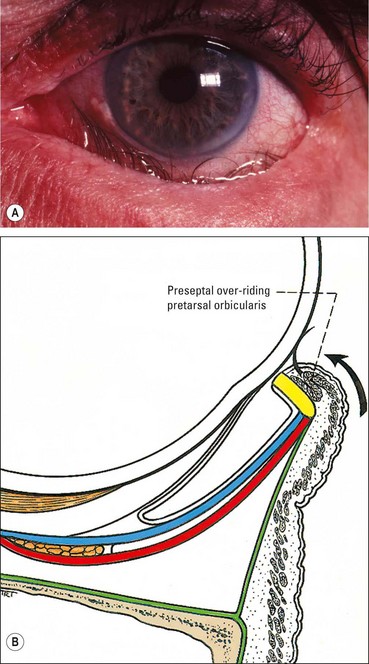

Involutional entropion

Involutional (age-related) entropion affects mainly the lower lid because the upper has a broader tarsus and is more stable. The constant rubbing of the lashes on the cornea in long-standing entropion (pseudotrichiasis – Fig. 1.68A) may cause irritation, corneal punctate epithelial erosions and, in severe cases, ulceration and pannus formation.

Fig. 1.68 (A) Involutional entropion and pseudotrichiasis; (B) preseptal orbicularis over-riding the pretarsal orbicularis

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis involves age-related degeneration of elastic and fibrous tissues within the eyelid resulting in the following:

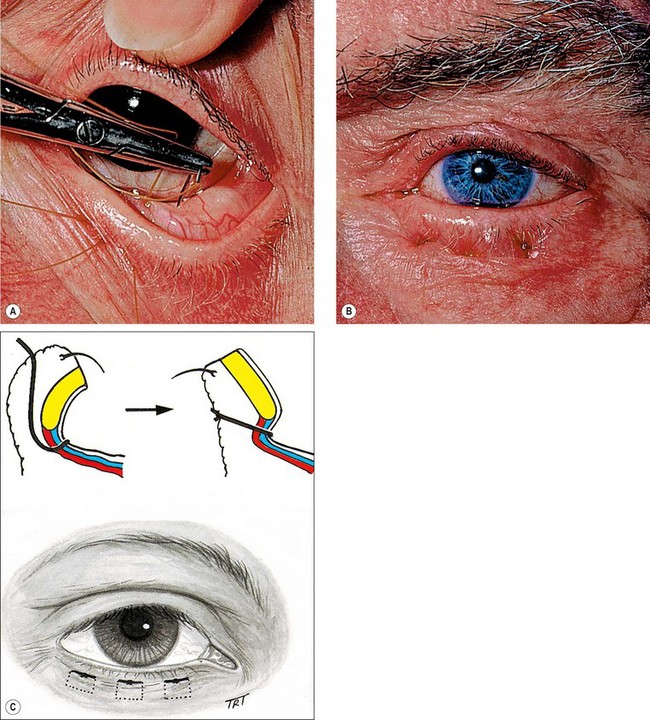

Treatment

Temporary treatment is with lubricants, taping, soft bandage contact lenses or orbicularis chemodenervation with botulinum toxin injection. Surgical treatment aims to correct the underlying problems as follows:

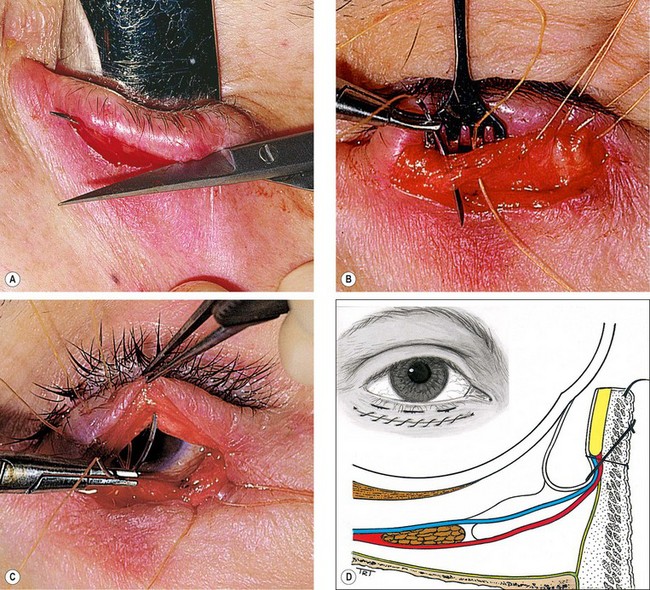

Fig. 1.69 Lid everting suture for entropion. (A) Three double armed sutures are passed blow the tarsal plate; (B) sutures are tied; (C) schematic

(Courtesy of AG Tyers and JRO Collin, from Colour Atlas of Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery, Butterworth-Heinemann 2001)

Fig. 1.70 Wies procedure for entropion. (A) Full-thickness incision; (B) sutures are passed through the conjunctiva and lower lid retractors; (C) sutures are passed anterior to the tarsal plate to exit inferior to the lashes; (D) schematic

(Courtesy of AG Tyers and JRO Collin, from Colour Atlas of Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery, Butterworth-Heinemann 2001 – figs A–C).

Fig. 1.71 Jones procedure for entropion. (A) Incision exposes the lower border of the tarsal plate; (B) reflection of the orbital septum and fat pad to expose the lower lid retractors; (C) tightening of retractors by plication; (D) schematic

(Courtesy of AG Tyers and JRO Collin, from Colour Atlas of Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery, Butterworth-Heinemann 2001)

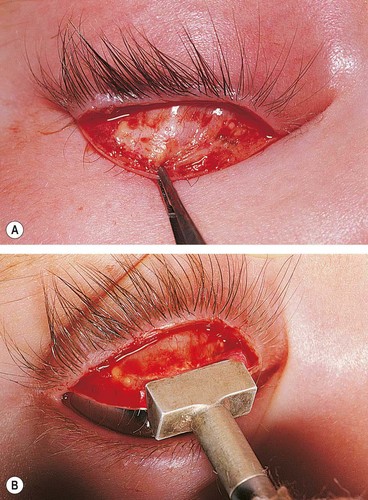

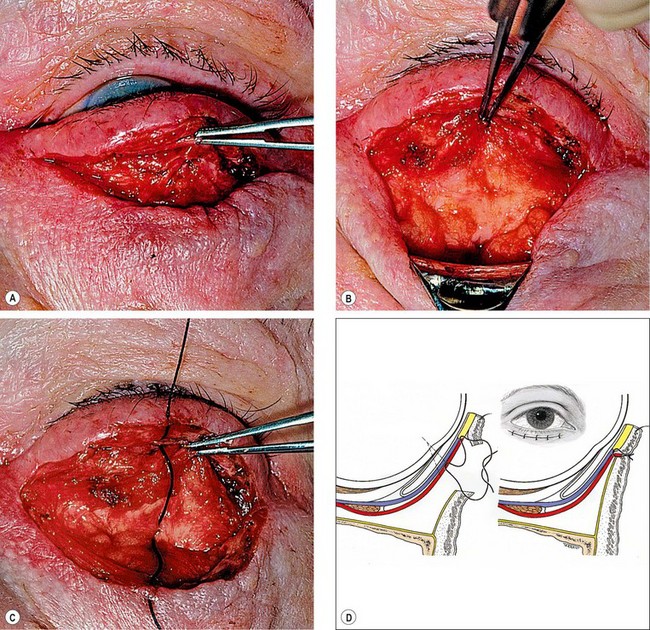

Cicatricial entropion

Miscellaneous acquired disorders

Varices

Eyelid varices are usually associated with orbital involvement (see Ch. 3). They appear as unilateral dark red or purple lesions subcutaneous lesions which in some cases become apparent only with a Valsalva manoeuvre (Fig. 1.72).

Blepharochalasis

Blepharochalasis is an uncommon condition characterized by recurrent episodes of painless, non-pitting oedema of both upper lids which usually resolves spontaneously after a few days.

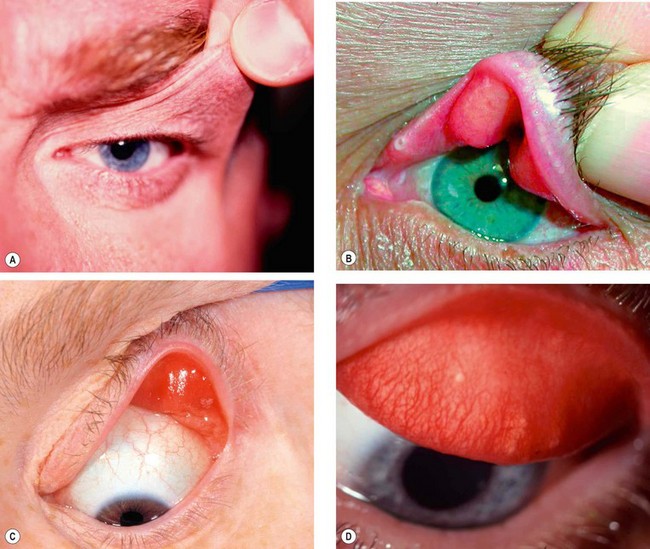

Floppy eyelid syndrome

Floppy eyelid syndrome is an uncommon unilateral or bilateral condition, which is often misdiagnosed. It typically affects obese middle-aged men who sleep face down with their lids everted by the pillow. Nocturnal exposure and poor contact of the lax lid with the globe in combination with tear film abnormalities result in keratoconjunctivitis.

Fig. 1.74 Floppy eyelid syndrome. (A) Redundant upper lid skin; (B) loose and rubbery tarsal plates; (C) easily everted eyelid; (D) papillary conjunctivitis of the upper tarsal conjunctiva

(Courtesy of J Nerad, K Carter and M Alford, from Oculoplastic and Reconstructive Surgery, in Rapid Diagnosis in Ophthalmology, Mosby 2008 – fig. B; S Tuft – fig. C)

Eyelid imbrication syndrome

Eyelid retraction

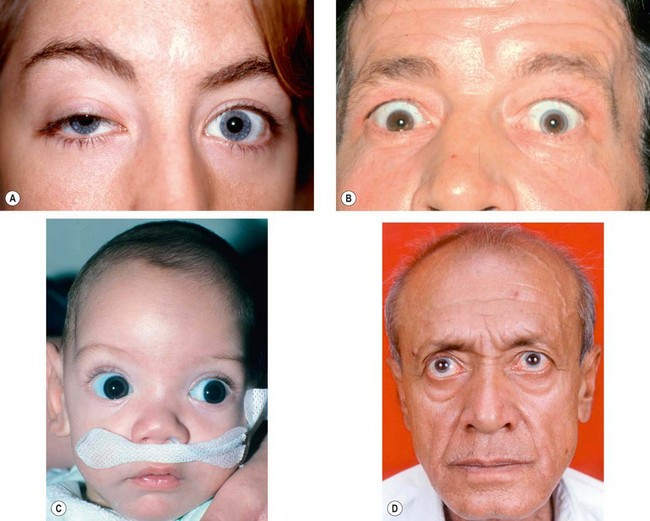

Lid retraction is suspected when the upper lid margin is either level with or above the superior limbus (Fig. 1.75A); the causes are listed in Table 1.5.

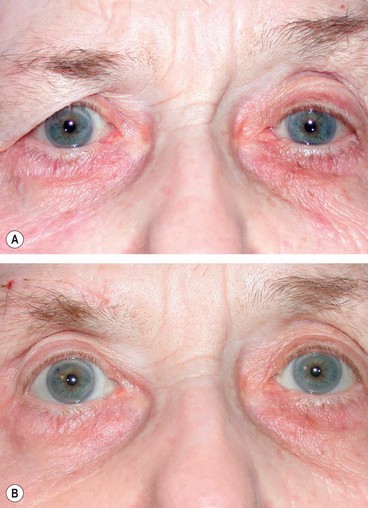

Fig. 1.75 (A) Left lid retraction in thyroid eye disease; (B) following eyelid lowering procedure

(Courtesy of A Pearson)

Table 1.5 Causes of lid retraction

Fig. 1.76 Causes of lid retraction. (A) Unilateral myasthenic ptosis with contralateral lid retraction; (B) Collier sign; (C) ‘setting sun’ sign in infantile hydrocephalus; (D) Parkinsonism

(Courtesy of R Bates– fig. C)

Treatment

Where there is no loss or tightness of upper eyelid skin, retraction is corrected by surgical release of the eyelid retractors, usually via a transconjunctival posterior approach. Mild retraction may be treated with Müller muscle recession (see Fig. 1.75B). Moderate to severe retraction may require levator aponeurosis recession.

Cosmetic eyelid and periocular surgery

Involutional changes

The following involutional (age-related) changes around the eyes can lead to both functional and cosmetic concerns that may require treatment:

Non-surgical techniques

Botulinum toxin injections to periocular muscles

Surgical techniques

Upper eyelid blepharoplasty

Lower eyelid blepharoplasty

Brow ptosis correction

Congenital malformations

Epicanthic folds

Epicanthic folds are bilateral vertical folds of skin that extend from the upper or lower lids towards the medial canthi. They may give rise to a pseudoexotropia.

Telecanthus

Telecanthus is an uncommon condition that may occur in isolation or in association with blepharophimosis syndrome.

Blepharophimosis ptosis and epicanthus inversus syndrome

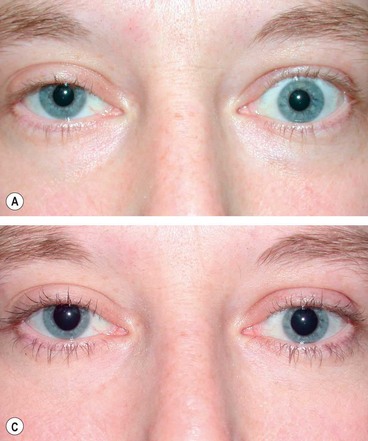

Epiblepharon

Epiblepharon is very common in Orientals and should not be confused with the much less common congenital entropion.

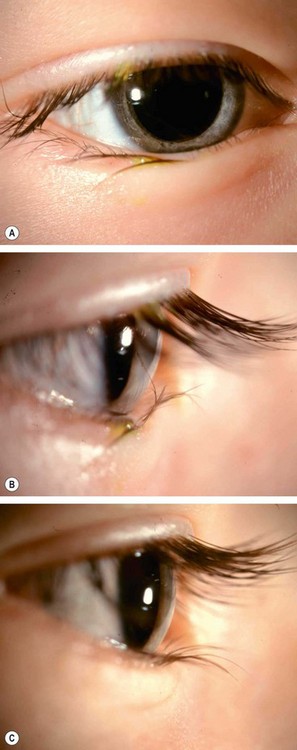

Fig. 1.83 (A) Epiblepharon; (B) lashes pointing upwards; (C) normal position of lashes following manual correction

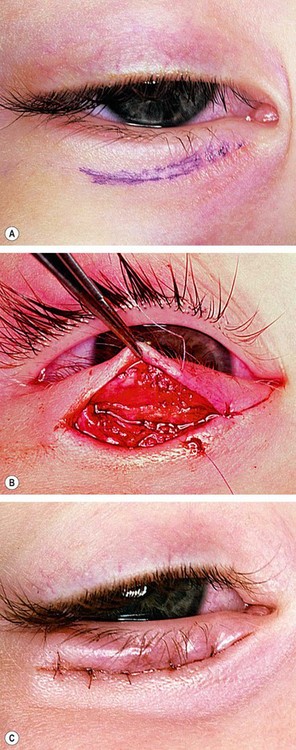

Fig. 1.84 Hotz procedure. (A) Incision marks on the medial two-thirds of the eyelid; (B) skin sutures passed deeply through the inferior tarsal border; (C) skin crease created by the sutures

(Courtesy of AG Tyers and JRO Collin, from Colour Atlas of Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery, Butterworth-Heinemann 2001)

Congenital entropion

Upper lid entropion

Upper lid entropion is usually secondary to mechanical effects of microphthalmos, which cause variable degrees of upper lid inversion.

Coloboma

A coloboma is an uncommon, unilateral or bilateral, partial or full-thickness eyelid defect. It occurs when eyelid development is incomplete, due to either failure of migration of lid ectoderm to fuse the lid folds, or to mechanical forces such as amniotic bands.

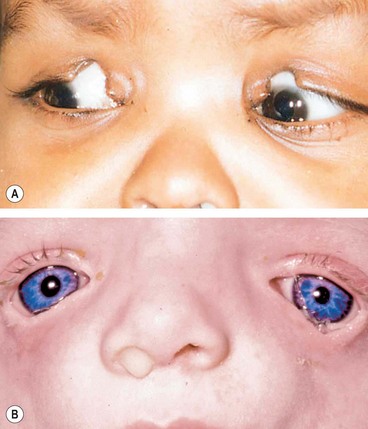

Fig. 1.86 (A) Upper lid colobomas; (B) lower lid colobomas in Treacher Collins syndrome

(Courtesy of U Raina – fig. A)

Treacher Collins syndrome

Treacher Collins syndrome (mandibulofacial dysostosis)is characterized by malformation of derivatives of the first and second branchial arches.

Euryblepharon

Microblepharon

Microblepharon is characterized by small eyelids, often associated with anophthalmos (Fig. 1.89).

Ablepharon

Cryptophthalmos

Congenital upper lid eversion

Congenital upper lid eversion is a rare condition more frequently seen in infants of Afro-Caribbean origin, in Down syndrome and in congenital ichthyosis (collodion skin disease – Fig. 1.92). It is typically bilateral and symmetrical. It may either resolve spontaneously with conservative treatment or may require surgery.