Caring for Families

• Discuss how the term family reflects family diversity.

• Explain how the relationship between family structure and patterns of functioning affects the health of individuals within the family and the family as a whole.

• Discuss the way family members influence one another’s health.

• Discuss the role of families and family members as caregivers.

• Discuss factors that promote or impede family health.

• Compare family as context to family as patient and explain the way these perspectives influence nursing practice.

• Use the nursing process to provide for the health care needs of the family.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

The Family

The family is a central institution in American society; however, the concept, structure, and functioning of the family unit continue to change over time. Families face many challenges, including the effects of health and illness, childbearing and childrearing, changes in family structure and dynamics, and caring for older parents. Family characteristics or attributes such as durability, resiliency, and diversity help families adapt to challenges.

Family durability is the term for the intrafamilial system of support and structure that extends beyond the walls of the household. For example, the parents may remarry or the children may leave home as adults, but in the end the “family” transcends long periods and inevitable lifestyle changes.

Family resiliency is the ability of the family to cope with expected and unexpected stressors. The family’s ability to adapt to role and structural changes, developmental milestones, and crises shows resilience. For example, a family is resilient when the wage earner loses a job and another member of the family takes on that role. The family survives and thrives as a result of the challenges they encounter from stressors.

Family diversity is the uniqueness of each family unit. For example, some families experience marriage for the first time and then have children in later life. Another family may include parents with young children as well as grandparents living in the home. Every person within a family unit has specific needs, strengths, and important developmental considerations.

As you care for patients and their families, you are responsible for understanding family dynamics, which include the family makeup (configuration), structure, function, problem-solving, and coping capacity. Use this knowledge to build on the family’s relative strengths and resources (Duhamel, 2010). The goal of family-centered nursing care is to promote, support, and provide for the well-being and health of the family and individual family members (Astedt-Kurki et al., 2002; Joronen and Astedt-Kurki, 2005).

Concept of Family

The term family brings to mind a visual image of adults and children living together in a satisfying, harmonious manner (Fig. 10-1). For some this term has the opposite image. Families represent more than a set of individuals, and a family is more than a sum of its individual members (Kaakinen et al., 2010). Families are as diverse as the individuals who compose them. Patients have deeply ingrained values about their families that deserve respect. You need to understand how your patients define their family. Think of the family as a set of relationships that the patient identifies as family or as a network of individuals who influence one another’s lives, whether or not there are actual biological or legal ties.

Definition: What Is a Family?

Defining family initially appears to be a simple undertaking. However, different definitions result in heated debates among social scientists and legislators. The definition of family is significant and affects who is included on health insurance policies, who has access to children’s school records, who files joint tax returns, and who is eligible for sick-leave benefits or public assistance programs. The family is defined biologically, legally, or as a social network with personally constructed ties and ideologies. For some patients family includes only persons related by marriage, birth, or adoption. To others, aunts, uncles, close friends, cohabitating persons, and even pets are family. Your personal beliefs do not have to be the same as those of your patient. Understand that families take many forms and have diverse cultural and ethnic orientations. In addition, no two families are alike. Each has its own strengths, weaknesses, resources, and challenges.

Current Trends and New Family Forms

Family forms are patterns of people considered by family members to be included in the family (Box 10-1). Although all families have some things in common, each family form has unique problems and strengths. Maintain an open mind about what makes up a family so you do not overlook potential resources and concerns.

Although the institution of the family remains strong, the family itself is changing. The “typical” family (two biological parents and children) is no longer the norm. People are marrying later, women are delaying childbirth, and couples are choosing to have fewer children or none at all. The number of people living alone is expanding rapidly and represents approximately 26% of all households. Divorce rates continue to be high; it is estimated that 54% of marriages will end in divorce (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2008). A number of divorced adults remarry; the median interval between divorce and remarriage is about 3 years. Remarriage often results in a blended family with a complex set of relationships among stepparents, stepchildren, half brothers and sisters, and extended family members.

Marital roles are also more complex as families increasingly comprise two wage earners. The majority of women work outside the home, and about 60% of mothers are in the workforce (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2008). Balancing employment and family life creates a variety of challenges in terms of child care and household work for both parents. The balance for working parents between child care and household duties is positive when the working parents’ job and life satisfactions remain high (Hill, 2005). There is no proof that maternal employment is damaging for children (Hill, 2005; Shpancer et al., 2006). However, finding quality child care is a major issue. Managing household tasks is another challenge. Although equal division of labor receives verbal approval, most household tasks remain “women’s work.” There is some evidence that the father’s role is changing. Fathers now participate more fully in day-to-day parenting responsibilities. Twenty-four percent of children (ages 0 to 4) have their fathers as caretakers whether or not the fathers are employed (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2008).

The number of single-parent families, which doubled from the 1970s to the 1990s, seems to be stabilizing. Forty-one percent of children are living with mothers who have never married; many of these children are a result of an adolescent pregnancy. Although mothers head most single-parent families, father-only families are on the rise.

Adolescent pregnancy is an ever-increasing concern. The majority of adolescent mothers continue to live with their families. A teenage pregnancy has long-term consequences for the mother. For example, adolescent mothers frequently quit high school and have inadequate job skills and limited health care resources. The overwhelming task of being a parent while still being a teenager often severely stresses family relationships and resources. In addition, there is an increased risk for subsequent adolescent pregnancy, inability to obtain quality job skills, and poor lifestyles (Harper et al., 2010). Stressors are also placed on teenage fathers when their partner becomes pregnant. These young men have poorer support systems and fewer resources to teach them how to parent. In addition, adolescent fathers report early adverse family relationships such as exposure to domestic violence and parental separation or divorce and lack positive fathering role models (Biello, Sipsma, and Kershaw, 2010). As a result, both adolescent parents often struggle with the normal tasks of development and identity but must accept a parenting role that they are not ready for physically, emotionally, socially, and/or financially.

Many homosexual couples define their relationship in family terms. Approximately half of all gay male couples live together compared with three fourths of lesbian couples. These couples are more open about their sexual preferences and more vocal about their legal rights. Some homosexual families include children, either through adoption or artificial insemination or from prior relationships.

The fastest-growing age-group in America is 65 years of age and over. For the first time in history the average American has more living parents than children, and children are more likely to have living grandparents and even great-grandparents. This “graying” of America continues to affect the family life cycle, particularly the “sandwich generation”—made up of the children of older adults (see section on restorative care). These individuals, who are usually in the middle years, have to meet their own needs along with those of their children and their aging parents. This balance of needs often occurs at the expense of their own well-being and resources. In addition, many of the family caregivers report that support from professional health professionals is lacking (Touhy and Jett, 2010). Most family caregivers are women; the average age is 46, with 13% being 65 years of age or older, and they frequently provide more than 20 hours of care per week (Schumacher, Beck, and Marren, 2006a). Caring for a frail or chronically ill relative is a primary concern for a growing number of families. It is not uncommon for people in their 60s and 70s to be the major caregivers for one another. Box 10-2 provides a list of family nursing gerontological concerns.

More grandparents are raising their grandchildren (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2008). This new parenting responsibility is the result of a number of societal factors: the increase in the divorce rate, dual-income families, and single parenthood. Most often it is a consequence of legal intervention when parents are unfit or renounce their parental obligations.

Families face many challenges, including changing structures and roles in the changing economic status of society. In addition, social scientists identify four further trends as threats or concerns facing the family: (1) changing economic status (e.g., declining family income and lack of access to health care), (2) homelessness, (3) family violence, and (4) the presence of acute or chronic illnesses.

Changing Economic Status

Making ends meet is a daily concern because of the declining economic status of families. Although two-income families have become the norm, real family income has not increased since 1973. Families at the lower end of the income scale have been particularly affected, and single-parent families are especially vulnerable. Because of recent economic trends adult children are often faced with moving back home after college because they cannot find employment or in some cases lose their jobs.

The number of American children living below the poverty level continues to rise. The number of children living below poverty increased by 2 million since 2000, and 8.1 million children are uninsured (Children’s Defense Fund [CDF], 2010). A majority of uninsured children have at least one parent who works but is unable to afford insurance. When caring for these families, the nurse needs to be sensitive to their desire for independence but also help them with obtaining appropriate financial and health care resources. For example, you inform the family where to go within the community to obtain assistance with energy bills, dental and health care, and assistance with school supplies.

Homelessness

Homelessness is a major public health issue. According to public health organizations, absolute homelessness describes people without physical shelter who sleep outdoors, in vehicles, in abandoned buildings, or in other places not intended for human habitation. Relative homelessness describes those who have a physical shelter, but one that does not meet the standards of health and safety (National Coalition for the Homeless, 2010).

The fastest growing section of the homeless population is families with children. This includes complete nuclear families and single-parent families. It is expected that 3.5 million people are homeless and 1.35 million are families with children. Poverty, mental and physical illness, and lack of affordable housing are primary causes of homelessness (National Coalition for the Homeless, 2010). Homelessness severely affects the functioning, health, and well-being of the family and its members. Children of homeless families are often in fair or poor health and have higher rates of asthma, ear infections, stomach problems, and mental illness (see Chapter 3). As a result, usually the only access to health care for these children is through an emergency department.

Children who are homeless face difficulties such as meeting residency requirements for public schools, inability to obtain previous enrollment records, and enrolling in and attending school. As a result, they are more likely to drop out of school and become unemployable (National Coalition for the Homeless, 2010). Homeless families and their children are at serious risk for developing long-term health, psychological, and socioeconomic problems. For example, the children are frequently underimmunized and at risk for childhood illnesses; they may fall behind in school and are at risk of dropping out; or they can develop risky behaviors.

Family Violence

The statistics regarding family violence are even more disturbing. Approximately 3.3 to 10 million children reported being abused or neglected in the period from 1991 to 2004 (Family Violence Prevention Fund, 2008a). Emotional, physical, and sexual abuse occurs toward spouses, children, and older adults and across all social classes. Factors associated with family violence are complex and include stress, poverty, social isolation, psychopathology, and learned family behavior. Other factors such as alcohol and drug abuse, pregnancy, sexual orientation, and mental illness increase the incidence of abuse within a family (Family Violence Prevention Fund, 2008b). Although abuse sometimes ends when one leaves a specific family environment, negative long-term physical and emotional consequences are often evident. One of the consequences includes moving from one abusive situation to another. For example, an adolescent girl sees marriage as a way to leave her parents’ abusive home and in turn marries a person who continues the abuse in her marriage.

Acute or Chronic Illness

Any acute or chronic illness influences the entire family economically, emotionally, socially, and functionally and affects the family’s decision-making and coping resources. Hospitalization of a family member is stressful for the whole family. Hospital environments are foreign, physicians and nurses are strangers, the medical language is difficult to understand or interpret, and family members are separated from one another.

During an acute illness such as a trauma, myocardial infarction, or surgery, family members are often left in waiting rooms to anticipate information about their loved one. Communication among family members may be misdirected from fear and worry. Sometimes previous family conflicts rise to the surface, whereas others are suppressed. When implementing a patient-centered care model, patients’ family members and surrogate decision makers must become active partners in decision making and care (Davidson, 2009). Understand the family’s cultural beliefs and values and need for communication and support.

Chronic illnesses are a global health problem. Adaptations to chronic illnesses pose unique challenges for the family (Weinert et al., 2008). Frequently family patterns and interactions, social activities, work and household schedules, economic resources, and other family needs and functions must be reorganized around the chronic illness or disability. Despite the stressors, families also learn how to manage many aspects of their loved one’s illness or disability. Astute nursing care helps the family prevent and/or manage medical crises, control symptoms, learn how to provide specific therapies, adjust to changes over the course of the illness, avoid isolation, obtain community resources, and assist in helping the family resolve conflict.

Chronic illnesses are common in a majority of family units. Chronic illness impacts a family’s quality of life. Families must work at developing working partnerships with the health care delivery system to identify available health care and community resources for disease management (Weinert et al., 2008). The chronic illness continuum ranges from newly diagnosed illness to end stages of the disease. The patient’s level of independence changes over time, and family members need to adapt to changing caregiving needs (Tamayo et al., 2010). Common chronic illnesses include but are not limited to asthma, diabetes, cardiovascular illnesses, renal disease, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and cancer.

Trauma

Trauma is a sudden unplanned event. Family members often struggle to cope with the challenges of a severe, life-threatening event, which can include the stressors associated with a family member hospitalized in an intensive care environment, loss of a family member, or an acute psychiatric illness. The powerlessness that family members experience makes them very vulnerable and less able to make important decisions about the health of the family. In caring for family members, answer their questions honestly. When you do not know the answer, find someone who does. Provide realistic assurance; giving false hope breaks the nurse-patient trust and also affects how the family can adjust to “bad news.” When the victim of trauma is hospitalized, take time to make sure that the family is comfortable. You can bring them something to eat or drink, give them a blanket, or encourage them to get a meal. Sometimes telling the family that you will stay with their loved one while they are gone is all they need to feel comfortable in leaving. Most family members have a cell phone and can be reached easily if their loved one’s condition changes.

End-of-Life Care

You will encounter many families with a terminally ill member. Although people equate terminal illness with cancer, many diseases have terminal aspects (e.g., heart failure, pulmonary and renal diseases, and neuromuscular diseases). Although some family members may be prepared for their loved one’s death, their need for information, support, assurance, and presence is great (see Chapter 36). The more you know about your patient’s family, how they interact with one another, their strengths, and their weaknesses, the better. Each family approaches and copes with end-of-life decisions differently. Give the family information about the dying process. Help the family set up home care if they desire and obtain hospice and other appropriate resources, including grief support. Make sure that the family knows what to do at the time of death. If you are present at the time of death, be sensitive to the family’s needs (e.g., provide for privacy and allow sufficient time for saying good-byes).

Theoretical Approaches: An Overview

A number of different perspectives can be applied when caring for families. It is important that you understand some of the broader perspectives for family nursing. The family health system (FHS) and developmental theories are two perspectives used in this chapter to help you provide nursing care to the family as a whole and the individuals within the family structure. These theoretical perspectives and their concepts provide the foundation for family assessment and interventions.

Family Health System

When assessing the family, it is important to use a guide such as the FHS to identify all of their needs. The FHS is a holistic model that guides the assessment and care for families (Anderson, 2000; Anderson and Friedemann, 2010). The FHS includes five realms/processes of family life: interactive, developmental, coping, integrity, and health. The FHS approach is one method for family assessment to determine areas of concern and strengths, which helps you develop a plan of care with family nursing interventions and outcomes. As with all systems, the FHS has both unspoken and spoken goals, which vary according to the stage in the family life cycle, family values, and individual concerns of the family members. When working with families, the goal of care is to improve family health or well-being, assist in family management of illness conditions or transitions, and achieve health outcomes related to the family areas of concern.

Developmental Stages

Families, like individuals, change and grow over time. Although they are far from identical to one another, they tend to go through common stages. Each developmental stage has its own challenges, needs, and resources and includes tasks that need to be completed before the family is able to successfully move on to the next stage. Societal changes and an aging population have caused changes in the stages and transitions in the family life cycle. For example, adult children are not leaving the nest as predictably or as early as in the past, and many are returning home. In addition, more people are living into their 80s and 90s. Sixty-five is now considered the “backside of middle age,” and the length of the midlife stage in the family life cycle has increased, as has the later stage in family life.

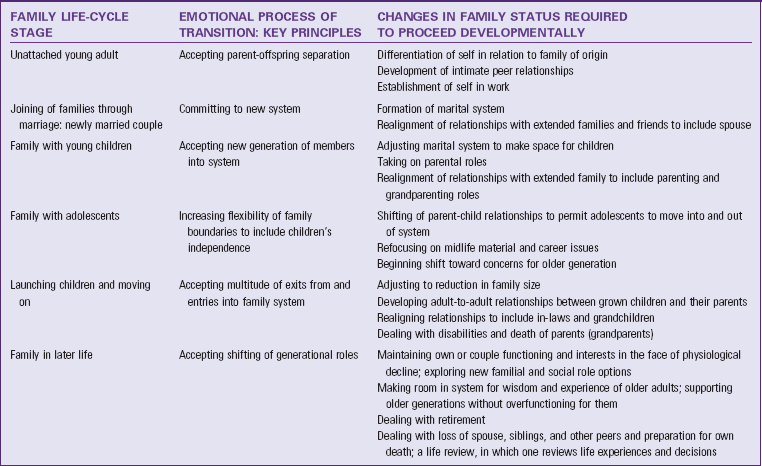

McGoldrick and Carter based their 1985 classic model of family life stages on expansion, contraction, and realignment of family relationships that support the entry, exit, and development of the members (Hanson et al., 2005). This model describes the emotional aspects of lifestyle transition and the changes and tasks necessary for the family to proceed developmentally (Table 10-1). Use this model to promote family behaviors to achieve essential tasks and help families prepare for later transitions such as when helping families prepare for a new baby (see Chapter 13).

Attributes of Families

Families have a structure and a way of functioning. Structure and function are closely related and continually interact with one another. Structure is based on the ongoing membership of the family and the pattern of relationships, which are often numerous and complex. For example, a woman’s relationships frequently include wife-husband, mother-son, mother-daughter, employee-boss, and colleague-colleague, each with different demands, roles, and expectations. Patterns of relationships form power and role structures within the family. Determine a family’s structures by observing family members’ behaviors and interactions.

Structure promotes or impedes the family’s ability to respond to stressors. Very rigid or very flexible structures impair functioning. A rigid structure specifically dictates who is able to accomplish a task and may limit the number of persons outside the immediate family who can assume these tasks. For example, in one family the mother is the only acceptable person to provide emotional support for the children, or the husband is the only one to provide financial support. A change in the health status of the person responsible for a task places a burden on the family because no other person is available or considered acceptable to assume that task. A family must adapt its structure. For example, when a homemaker is ill, the tasks of managing the household (e.g., preparing the meals, maintaining the house, and driving school-age children to appointments and events) need to be shared. The older children may help prepare the meals, and the other parent or a family member drives the children to the events, or perhaps the events are rescheduled.

An extremely open structure also presents problems for the family. When the family structure is extremely open, consistent patterns of behavior that lead to automatic action do not exist. An example is an inconsistent parenting role. The parent sometimes is a strict authoritarian figure and at other times treats the child as a “best friend and confidant.” This type of conduct causes family members to become confused about what behavior is appropriate and who is reliable for support. During a crisis or rapid change, family members do not have a defined structure to “fall back on,” and family disintegration is sometimes a result.

Function

Family functioning is what the family does. Specific functional aspects include the way a family reproduces, interacts to socialize its young, cooperates to meet economic needs, and relates to the larger society. Family functioning also focuses on the processes used by the family to achieve its goals. Some processes include communication among family members, goal setting, conflict resolution, caregiving, nurturing, and use of internal and external resources. Traditional reproductive, sexual, economic, and educational goals that were once universal family goals no longer apply to all families. For example, a married couple who decides not to have children still consider themselves a family. Another example includes a blended family whose spouses bring school-age children into the new marriage. However, the spouses decide not to co-mingle their finances and have separate educational goals for their minor children. As a result, this family does not have the traditional economic patterns of a nuclear family.

Families achieve goals more successfully when communication is clear and direct. Clear communication enhances problem solving and conflict resolution, and it facilitates coping with life-changing or life-threatening stressors. Another process to facilitate goal achievement includes the ability to nurture and promote growth. For example, families might have a specific celebration for a good report card, a job well done, or specific milestones. They also nurture by helping children know right and wrong. In this situation a family might have a specific form of discipline such as “time out” or taking away privilege, and the children know why the discipline is given. Thus when a situation occurs, the child is disciplined and learns not to behave like that again.

Families need to have multiple resources available. For example, a social network is an excellent resource. Social relationships such as friends or churches within the community are important for family celebrations but also act as buffers, particularly during times of stress, and reduce a family’s vulnerability.

The Family and Health

Many factors influence the health of the family (e.g., its relative position in society, economic resources, and geographical boundaries). Although American families exist within the same culture, they live in very different ways as a result of race, values, social class, and ethnicity. In some minority groups multiple generations of single-parent families live together in one home. Class and ethnicity produce differences in the access of families to the resources and rewards of society. This access creates differences in family life, most significantly in different life chances for its members.

Distribution of wealth greatly affects the capacity to maintain health. Low educational preparation, poverty, and decreased social support compound one another, magnifying their effect on sickness in the family, and magnifying the amount of sickness in the family. Economic stability increases a family’s access to adequate health care, creates more opportunity for education, increases good nutrition, and decreases stress (National Coalition of the Homeless, 2010; Children’s Defense Fund, 2010).

The family is the primary social context in which health promotion and disease prevention take place. The family’s beliefs, values, and practices strongly influence health-promoting behaviors of its members (Epley et al., 2010). In turn the health status of each individual influences how the family unit functions and its ability to achieve goals. When the family satisfactorily functions to meet its goals, its members tend to feel positive about themselves and their family. Conversely, when they do not meet goals, families view themselves as ineffective.

Some families do not place a high value on good health. In fact, some families accept harmful practices. In some cases a family member gives mixed messages about health. For example, a parent continues to smoke while telling children that smoking is bad for them. Family environment is crucial because health behavior reinforced in early life has a strong influence on later health practices. In addition, the family environment is a crucial factor in an individual’s adjustment to a crisis. Although relationships are strained when confronted with illness, research indicates that family members can have the potential to be a primary force for coping (Bluvol and Ford-Gilboe, 2004).

Attributes of Healthy Families

The family is a dynamic unit; it is exposed to threats, strengths, changes, and challenges. Some families are crisis proof, whereas others are crisis prone. The crisis-proof, or effective, family is able to combine the need for stability with the need for growth and change. This type of family has a flexible structure that allows adaptable performance of tasks and acceptance of help from outside the family system. The structure is flexible enough to allow adaptability but not so flexible that the family lacks cohesiveness and a sense of stability. The effective family has control over the environment and influences the immediate environment of home, neighborhood, and school. The ineffective, or crisis-prone, family lacks or believes it lacks control over the environments.

Health promotion research often focuses on the stress-moderating effect of hardiness and resiliency as factors that contribute to long-term health. Family hardiness is the internal strengths and durability of the family unit. A sense of control over the outcome of life, a view of change as beneficial and growth producing, and an active rather than passive orientation in adapting to stressful events characterize family hardiness (McCubbin, McCubbin, and Thompson, 1996). Family resiliency is the ability to cope with expected and unexpected stressors. It helps to evaluate healthy responses when individuals and families are experiencing stressful events. Resources and techniques that a family or individuals within the family use to maintain a balance or level of health assist in understanding a family’s level of resiliency.

Family Nursing

To provide compassion and caring for your patients and their families, you need a scientific knowledge base in family theory and knowledge in family nursing. A focus on the family is necessary to safely discharge patients back to the family or community settings. The members of the family may need to assume the role of primary caregiver. Family caregivers have unique nursing and caregiving needs and too often feel abandoned by the health care system (Reinhard, 2006). When a life-changing illness occurs, the family has to make major adjustments to care for a family member. Often the psychological, social, and health care needs of the caregiver go unmet (Tamayo et al., 2010).

Family nursing is based on the assumption that all people, regardless of age, are members of some type of family form, such as the traditional nuclear family or an alternate family. The goal of family nursing is to help the family and its individual members reach and maintain maximum health throughout and beyond the illness experience (Box 10-3). Family nursing is the focus of the future across all practice settings and is important in all health care environments.

There are different approaches for family nursing practice. For the purposes of this chapter, family nursing practice has three levels of approaches: (1) family as context; (2) family as patient; and (3) the newest model, called family as system, which includes both relational and transactional concepts. If only one family member receives nursing care, it is realistic and practical to view the family as context. When all family members are involved in the daily care of one another, nursing intervention with one individual necessitates some change in the activities of the others, suggesting that family as patient is the best approach. All three approaches are useful in providing effective nursing care.

Family As Context

When you view the family as context, the primary focus is on the health and development of an individual member existing within a specific environment (i.e., the patient’s family). Although the focus is on the individual’s health status, assess how much the family provides the individual’s basic needs. Needs vary, depending on the individual’s developmental level and situation. Because families provide more than just material essentials, you will also need to consider their ability to help the patient meet psychological needs. Some family members need direct interventions themselves.

Family As Patient

When the family as patient is the approach, family processes and relationships (e.g., parenting or family caregiving) are the primary focuses of nursing care. Focus your nursing assessment on family patterns versus individual member characteristics. Concentrate on patterns and processes that are consistent with reaching and maintaining family and individual health. Plan care to meet not only the patient’s needs, but also the changing needs of the family. Dealing with very complex family problems often requires an interdisciplinary approach. Always be aware of the limits of nursing practice and make referrals when appropriate.

Family As System

It is important to understand that, although you are able to make theoretical and practical distinctions between the family as context and the family as patient, they are not necessarily mutually exclusive. When you care for the family as a system, you are caring for each family member (family as context) and the family unit (family as patient), using all available environmental, social, psychological, and community resources.

The following clinical scenario illustrates three levels of approaches to family care.

You are assisting with end-of-life care for David Daniels, who is 35 years old. David and his wife, Lisa, have three school-age children. David expressed a wish to die at home and not in a hospital or extended care facility. Lisa is on family leave from her job to help David through this period. Both Lisa and David are only children. David’s parents are no longer living, but Lisa’s mother is committed to stay with the family to help Lisa and David.

When you view this family as context, you focus on the patient (David) as an individual. You assess and meet David’s comfort, hygiene, and nutritional needs. You also meet David’s social and emotional needs. When viewing the family as patient, you assess and meet David’s family’s comfort and nutritional needs. You determine the family’s need for rest and their stage of coping. It is important to determine the demands placed on David and the family. In addition, you need to continually evaluate the family’s available resources such as time, finances, coping skills, and energy level to support David through the end of life.

When viewing the family as system, you use elements from both of the previous perspectives, but you also assess the resources available to the family. Using the knowledge of the family as context, patient, and a system, individualize care decisions based on the family assessment and your clinical judgment. For example, based on your assessment, you determine that the family is not eating adequately. You also determine that Lisa is experiencing more stress, not sleeping well, and trying to “do it all” regarding her children’s school and after-school activities. In addition, Lisa does not want to leave David’s bedside when members of their church come to help. You recognize that this family is under enormous stress and that their basic needs such as meals, rest, and school activities are not adequately met. As a result, you determine that (1) the family needs assistance with meals, (2) Lisa needs time to rest, and (3) the family’s church is eager to help with David’s day-to-day care. On the basis of these decisions, you work with Lisa, David, and the family to set up a schedule among Lisa, her mother, and two close church members to provide Lisa with some time away from David’s bedside. However, David and Lisa determine when this time will be. Because of the church involvement, members of the church begin to take responsibility for groceries and all meal preparation for the family. In addition, other members of the church help with the children’s school and after-school activities.

Nursing Process for the Family

Nurses interact with families in a variety of community-based and clinical settings. The nurse uses the nursing process to care for an individual within a family (e.g., the family as context) or the entire family (e.g., the family as patient). When initiating the care of families, three factors organize the family approach to the nursing process:

1. The nurse views all individuals within their family context.

Assessing the Needs of the Family

Family assessment is a priority in order to provide adequate family care and support. You have an essential role in helping families adjust to acute and chronic illness, but first you need to understand the family unit and what a patient’s illness means to the family members and family functioning. You also need to understand how the illness has affected the family structure and the support the family requires (Kaakinen et al., 2010). Although the family as a whole differs from individual members, the measure of family health is more than a summary of the health of all members. The form, structure, function, and health of the family are areas unique to family assessment. Box 10-4 includes the five areas of family life to include in an assessment.

During an assessment, incorporate knowledge of the patient’s illness and assess the primary patient and the family. When focusing on the family, begin the family assessment by determining the patient’s definition of and attitude toward the family. The concept of family is highly individualized. The patient’s definition will influence how much you are able to incorporate the family into nursing care. To determine family form and membership, ask who the patient considers family or with whom the patient shares strong emotional feelings. If the patient is unable to express a concept of family, ask with whom the patient lives, spends time, and shares confidences and then ask whether the patient considers them to be family or like family. To further assess the family structure, ask questions that determine the power structure and patterning of roles and tasks (e.g., “Who decides where to go on vacation?” “How are tasks divided in your family?” “Who mows the lawn?” “Who usually prepares the meals?”).

You need to assess family functions such as the ability to provide emotional support for members, the ability to cope with current health problems or situations, and the appropriateness of its goal setting and progress toward achievement of developmental tasks (Fig. 10-2). Also determine whether the family is able to provide and distribute sufficient economic resources and whether its social network is extensive enough to provide support.

FIG. 10-2 Nurse providing family education. (From Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D: Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 9, St Louis, 2011, Mosby.)

Always recognize and respect the family’s cultural background (see Chapter 9). Culture is an important variable when assessing the family because race and ethnicity affect structure, function, health beliefs, values, and the way the family perceives events (Box 10-5). The United States is increasingly more diverse. A large number of immigrants enter the country daily, adding to both the number and variety of the many ethnic groups that make up the population. American health care institutions tend to operate from a white, middle-class perspective; and immigrant populations have particular difficulty understanding and “fitting into” the system. Cultural assessment educators encourage the use of a “culturagram,” which allows you to assess and empower culturally diverse families and encourages ethnic-sensitive practice. This tool assesses a variety of factors such as language spoken in the home; impact of crisis events; and values regarding family, education, and work.

Drawing conclusions based on cultural backgrounds requires critical thinking and careful consideration. It is imperative to remember that categorical generalizations are misleading (e.g., all Asian Americans are good at mathematics). As many caution, overgeneralizations in terms of racial and ethnic group characteristics do not lead to greater understanding of the culturally diverse family. Culturally different families vary in meaningful and significant ways; however, neglecting to examine similarities leads to inaccurate assumptions and stereotyping. For example, more similarities than differences exist in parenting behaviors among white, African American, Hispanic, and Asian American parents. In addition, Asian American families use alternative therapies for illnesses and ailments. Other cultures such as Latino prefer to stay with their family members during illness (see Chapter 9). A comprehensive, culturally sensitive family assessment is critical in order for you to understand family life, the current changes within it, and the family’s overall goals and expectations. These data provide the foundation for family-centered nursing care (Anderson and Friedemann, 2010).

Family-Focused Care

Use a family-focused approach to enhance your nursing care. When you establish a relationship with a patient and his or her family, it is important to identify potential and external resources. A complete patient and family assessment provides this information. Together with patients and their families, develop plans of care that all members clearly understand and mutually agree to follow. Goals that you establish need to be concrete and realistic, compatible with a family’s developmental stage, and acceptable to family members.

Collaboration with family members is essential, whether the family is the patient or the context of care. Collaborate closely with all appropriate family members when determining what they hope to achieve with regard to the family’s health. You base a positive collaborative relationship on mutual respect and trust. The family needs to feel “in control” as much as possible. By offering alternative actions and asking family members for their own ideas and suggestions, you help to reduce the family’s feelings of powerlessness. For example, offering options for how to prepare a low-fat diet or how to rearrange the furnishings of a room to accommodate a family member’s disability gives the family an opportunity to express their preferences, make choices, and ultimately feel as though they have contributed. Collaborating with other disciplines increases the likelihood of a comprehensive approach to the family’s health care needs, and it ensures better continuity of care. Using other disciplines is particularly important when discharge planning from a health care facility to home or an extended care facility is necessary (Bluvol and Ford-Gilboe, 2004).

When you view the family as the patient, you need to support communication among all family members. This ensures that the family remains informed about the goals and interventions for health care. Often you participate in conflict resolution between family members so each member is able to confront and resolve problems in a healthy way. Help the family identify and use external and internal resources as necessary. For example, who in the family can run errands to get groceries while the patient is unable to drive? Are there members from the church who can come and provide respite care? Ultimately your aim is to help the family reach a point of optimal function, given the family’s resources, capacities, and desire to become healthier.

Challenges for Family Nursing

If a patient has been hospitalized or is in a rehabilitation setting, discharge planning begins with the initiation of care and includes the family. You are responsible for an accurate assessment of what will be needed for care in the home at the time of discharge, along with any shortcomings in the home setting. For example, if a postoperative patient is discharged to home and the older adult husband does not feel comfortable with the dressing changes required, you need to find out if anyone else in the family or neighborhood is willing and able to do this. If not, you will need to arrange for a home care service referral. If the patient also needs exercise and strength training, you consult with the primary health care provider to recommend referral for physical therapy.

Cultural sensitivity (see Chapter 9) in family nursing requires recognizing not only the diverse ethnic, cultural, and religious backgrounds of patients but also the differences and similarities within the same family. When providing family-centered care, recognize and integrate cultural practices, religious ceremonies, and rituals. Using effective and respectful communication techniques enables you to collaborate with the family to determine how best to integrate their beliefs and practices within the prescribed health care plan. For example, traditional Asian and Mexican American cultures frequently want to remain at the bedside around the clock and provide personal care for their loved ones. Integrating the family’s values and needs into the care plan involves teaching family members how to provide simple direct care measures, thus providing culturally sensitive and competent care. Together the nurse and the family blend the cultural and health care needs of the patient.

Implementing Family-Centered Care

Whether caring for a patient with the family as context, directing care to the family as patient, or providing care to the family as a system, nursing interventions aim to increase family members’ abilities in certain areas, remove barriers to health care, and do things that the family is not able to do for itself. Assist the family in problem solving, provide practical services, and express a sense of acceptance and caring by listening carefully to family members’ concerns and suggestions.

One of the roles you need to adopt is that of educator. Health education is a process by which the nurse and patient share information in a two-way fashion (see Chapter 25). Sometimes you recognize family/patient needs for information through direct questioning, but the methods for recognizing these needs are generally far more subtle. For example, you recognize that a new father is fearful of cleaning his newborn’s umbilical cord or that an older adult woman is not using her cane or walker safely. Respectful communication is necessary. Often you find the subtle needs for information by saying, “I notice you are trying to not touch the umbilical cord; I see that a lot.” Or “You use the cane the way I did before I was shown a way to keep from falling or tripping over it; do you mind if I show you?” When you are confident and skillful instead of coming across as an authority on the subject, your patient’s defenses are down, making the patient more willing to listen without feeling embarrassed. You will also recognize patient and family learning needs on the basis of the patient’s health condition and physical and mental limitations. Your focus as an educator may become the family caregiver, so that he or she can become prepared to manage the skills and processes needed to manage the patient’s needs within the home. When educating patients and families, identify the best time to provide accurate health information about diagnosis, necessary self-care activities, and the projected course of the patient’s condition. Such information helps the family caregiver to interpret behavior correctly and not to “blame” the patient (Schumacher, Beck, and Marren, 2006a).

Health Promotion

Although the family is the basic social context in which members learn health behaviors, the primary focus on health promotion has traditionally been on individuals. When implementing family nursing, health promotion interventions improve or maintain the physical, social, emotional, and spiritual well-being of the family unit and its members (Duhamel, 2010; Rosenthal et al., 2008). Health promotion behaviors need to be tied to the developmental stage of the family (e.g., adequate prenatal care for the childbearing family or adherence to immunization schedules for the childrearing family). Your interventions should be designed to enable individual members and the total family to reach their optimal levels of wellness.

One approach for meeting goals and promoting health is the use of family strengths. Families do not often look at their own system as one that has inherent, positive components. Family strengths include clear communication, adaptability, healthy childrearing practices, support and nurturing among family members, the use of crisis for growth, a commitment to one another and the family unit, and a sense of cohesiveness and spirituality (Schumacher, Beck, and Marren, 2006a). Help the family focus on their strengths instead of on problems and weaknesses. For example, point out that a couple’s 10-year marriage has endured many crises and transitions. Therefore they are likely to be able to adapt to this latest challenge. Refer families to health promotion programs aimed at enhancing these attributes as needed. For example, some communities have low-cost fitness activities for school-age children designed to reduce the risk for obesity.

Acute Care

Because the family is becoming more of a focus in nursing care, you need to emphasize family needs within the context of today’s health care delivery system. Be aware of the implication of early discharge for patients and their families. Remember that increasing numbers of people within the household are now being employed outside the home. These factors are challenges in preparing family members to assist with health care or locate appropriate community resources. Often when family members assume the role of caregiver, they lose support from significant others and are at risk for caregiver role strain (Schumacher, Beck, and Marren, 2006a). You need to be sure that families are willing to assume care responsibilities.

Family nursing requires a holistic view not only of the patient but also of the family. Nursing care in the acute environment is very complex, making it a challenge for the patient to feel cared for and to keep family members involved. A helpful tool is an independent journal in which patients and family members communicate their thoughts, ideas, and reactions. The patient or family members use the journal as an open communication tool, updating entries based on their needs and observations of the acute care experience. It is also helpful for a family member to use the journal as a record of care activities. It also provides data about when the patient was turned, who visited, when the last pain medication was administered, and any special patient requests. This information helps patients and families who are trying to “keep up” with what is happening in the acute care environment.

Restorative and Continuing Care

In restorative and continuing care settings the challenge in family nursing is in trying to maintain patients’ functional abilities within the context of the family. This includes having home care nurses help patients remain in their homes following acute injuries or illnesses, surgery, or exacerbation of a chronic illness. It also requires finding ways to better the lives of chronically ill and disabled individuals and their families.

Family Caregiving: One way you provide family care is through support of family caregivers. In 2007, the economic value of family caregiving was estimated at $375 billion, which exceeded the total amount of 2007 Medicaid expenditures ($311 billion) and approached the total expenditures in Medicare ($432 billion) (AARP Public Policy Institute, 2008). Research shows that millions of Americans are taking on the burden of caregiving without acknowledging the effect that it has on their lives and without realizing that relief is available. Multiple national outreach programs such as the National Family Caregivers Association (www.thefamilycaregiver.org) and the National Alliance for Caregiving (www.caregiving.org) connect family caregivers to information and services that can help improve their lives and the level of care they can offer their loved ones.

Family caregiving is a family process that occurs in response to an illness and encompasses multiple cognitive, behavioral, and interpersonal processes (Schumacher et al., 2006b). It typically involves the routine provision of services and personal care activities for a family member by spouses, siblings, friends, or parents. Caregiving activities include finding resources, providing personal care (bathing, feeding, or grooming), monitoring for complications or side effects of an illness or treatments, providing instrumental activities of daily living (shopping or housekeeping), and the ongoing emotional support and decision making that is necessary (Schumacher, Beck, and Marren, 2006a). Family caregiving can create caregiver burden and strain. The physical and emotional demands are high, and the disease itself creates changes in the family structure and roles. Family caregivers often feel ill prepared to take on the demands of care for their loved ones (Tamayo et al., 2010). Providing education to the family caregiver helps relieve some of the stress of caregiving (Box 10-6).

Whenever an individual becomes dependent on another family member for care and assistance, significant stress affects both the caregiver and the care recipient. In addition, the caregiver needs to continue to meet the demands of his or her usual lifestyle (e.g., raising children, working full time, or dealing with personal problems or illness). In many instances adult children, the sandwich generation, are trying to take care of their parents while meeting the needs of their own family (Box 10-7). Without adequate preparation and support from health care providers, caregiving puts the family at risk for serious problems, including a decline in the health of the caregiver and that of the care receiver and dysfunctional and even abusive relationships (Schumacher, Beck, and Marren, 2006a; Tamayo et al., 2010).

Despite its demands, family caregiving can be a positive and rewarding experience. It is more than simply a series of tasks and usually occurs within the context of a family. Whether it is a wife caring for a husband or a daughter caring for a mother, caregiving is an interactional process. The interpersonal dynamics among family members influence the ultimate quality of caregiving. Thus the nurse plays a key role in helping family members develop better communication and problem-solving skills to build the relationships needed for caregiving to be successful (Stajduhar et al., 2008; Tamayo et al., 2010).

Variables such as caregiver and care-recipient expectations of one another influence caregiving quality. Carruth (1996) studied the concept of reciprocity, acknowledging the importance of the capability of care recipients to share exchanges that contribute to a caregiver’s perception of self-worth. When the caregiver knows that the care recipient appreciates his or her efforts and values the assistance provided, a healthier and more satisfying caregiving relationship exists. When a caregiver and patient solve problems together, this helps them avoid overprotection or oversolicitous behavior. Patients feel in control of their care and responsible for care decisions. The caregiver also feels very positive and enjoys the caregiving experience (Isaksen, Thuen, and Hanestad, 2003).

Providing care and support for family caregivers enhances patient safety and involves using available family and community resources. Establishing a caregiving schedule that enables all family members to participate, helping patients to identify extended family members who can share any financial burdens posed by caregiving, and having distant relatives send cards and letters communicating their support is very helpful. However, it is imperative for you to understand the relationship between potential caregivers and care recipients. If the relationship is not a supportive one, community services are often a better resource for the patient and family.

Use of community resources includes locating a service required by the family or providing respite care so the family caregiver has time away from the care recipient. Examples of services that are beneficial to families include caregiver support groups, housing and transportation services, food and nutrition services, housecleaning, legal and financial services, home care, hospice, and mental health resources. Before referring a family to a community resource, it is critical that the nurse understand the family’s dynamics and know whether the family wants support. Often a family caregiver resists help, feeling obligated to be the sole source of support to the care recipient. Be sensitive to family relationships and help caregivers understand the normalcy of caregiving demands. Given the appropriate resources, caregivers are able to acquire the skills and knowledge necessary to effectively care for their loved ones within the context of the home while maintaining rich and rewarding personal relationships.

Key Points

• Family structure and functions influence the lives of its individual members.

• Family members influence one another’s health beliefs, practices, and status.

• The concept of family is highly individual; care focuses on the patient’s attitude toward the family rather than on an inflexible definition of family.

• The family’s structure, functioning, and relative position in society significantly influence its health and ability to respond to health problems.

• A nurse can view the family in three ways: as context, as the patient, or as a system.

• Measures of family health involve more than a summary of individual members’ health.

• Family members as caregivers are often spouses who are either older adults themselves or adult children trying to work full-time, care for aging parents, and launch teenagers successfully.

• Cultural sensitivity is vital to family nursing. Some members have differing beliefs, traditions, and restrictions, even within the same generation.

• Family caregiving is an interactive process that occurs within the context of the relationships among its members.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

Kathy is a home health nurse working with the Kline family. This is a family of four: Carol, a 45-year-old single mother; her two adolescent sons, Matt and Kent; and Sara, her 76-year-old mother, who is in the last stages of Alzheimer’s disease. The mother has lived with Carol and her children for 10 years. Sara was a great support to Carol when her husband died 11 years ago. She helped Carol raise Matt and Kent. The family has decided to care for Sara in the home until she dies. Kathy is helping the family care for Sara in the home.

1. What type of assessments are important to determine family functioning and structure?

2. What should Kathy assess to determine how the family can achieve their goal of caring for Sara?

3. How does Kathy help the family determine their strengths, weaknesses, and resources?

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. The Collins family includes a mother, Jean; stepfather, Adam; two teenage biological daughters of the mother, Lisa and Laura; and a biological daughter of the father, 25-year-old Stacey. Stacey just moved home following the loss of her job in another city. The family is converting a study into Stacey’s bedroom and is in the process of distributing household chores. When you talk to members of the family, they all think that their family can adjust to lifestyle changes. This is an example of family:

2. The most common reason grandparents are called on to raise their grandchildren is because of:

3. A family’s access to adequate health care, opportunity for education, sound nutrition, and decreased stress is affected by:

4. David Singer is a single parent of a 3-year-old boy, Kevin. Kevin has well-managed asthma and misses day care infrequently. David is in school studying to be an information technology professional. His income and time are limited, and he admits to going to fast-food restaurants frequently for dinner. However, he and his son spend a lot of time together. David receives state-supported health care for his son, but he does not have health insurance or a personal physician. He has his son enrolled in a government-assisted day care program. Which of the following are risks to this family’s level of health? (Select all that apply.)

5. The Cleric family, which includes a mother, stepfather, two teenage biological daughters of the mother, and a biological daughter of the father is an example of a(n):

6. Which of the following are possible outcomes with clear family communication? (Select all that apply.)

7. Communication among family members is an example of family:

8. Which of the following contribute to family hardiness? (Select all that apply.)

9. Which of the following demonstrate family resiliency? (Select all that apply.)

1. Resuming full-time work when spouse loses job

2. Arguing ways to deal with problems among siblings

10. When nurses view the family as context, their primary focus is on the:

1. Family members within a system.

2. Family process and relationships.

11. Diane is a hospice nurse who is caring for the Robinson family. This family is providing end-of-life care for their grandmother, who has terminal breast cancer. When Diane visits the home 3 times a week, she focuses on symptom management for the grandmother and assists the family with coping skills. Diane’s approach is an example of which of the following?

12. Which of the following are included in a family function assessment? (Select all that apply.)

13. Karen Johnson is a single mother of a school-age daughter. Linda Brown is also a single mother of two teenage daughters. Karen and Linda are active professionals, have busy social lives, and date occasionally. Three years ago they decided to share a house and housing costs, living expenses, and child care responsibilities. The children consider one another as their family. This family form is considered a(n):

14. During a visit to a family clinic the nurse teaches the mother about immunizations, car seat use, and home safety for an infant and toddler. Which type of nursing interventions are these?

15. Which best defines family caregiving? (Select all that apply.)

Answers: 1. 3; 2. 2; 3. 4; 4. 1, 3; 5. 2; 6. 1, 2, 3; 7. 2; 8. 1, 2, 3; 9. 1, 3; 10. 4; 11. 2; 12. 1, 2, 3; 13. 4; 14. 1; 15. 2, 3, 4.

References

AARP Public Policy Institute (2008). Issue Brief: Valuing the invaluable: A new look at the economic value of family caregiving. http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/il/i13_caregiving.pdf, 2008. [Update Accessed November 1, 2010.].

Anderson, KH, Friedemann, ML. Strategies to teach family assessment and intervention through an online international curriculum. J Fam Nurs. 2010;16(2):213.

Children’s Defense Fund, State of America’s Children—2010 Report. Washington, DC: Children’s Defense Fund; 2010. http://www.childrensdefense.org/child-research-data-publications/data/state-of-americas-children-2010-report.html [Accessed August 19, 2010].

Davidson, JE. Family-centered care: meeting the needs of patients’ families and helping families adapt to critical illness. Crit Care Nurse. 2009;29(3):28.

Duhamel, F. Implementing family nursing: how do we translate knowledge into clinical practice? Part 2. J Fam Nurs. 2010;16(1):8.

Epley, P, et al. Characteristics and trends in family-centered conceptualizations. J Fam Social Work. 2010;13:269.

Family Violence Prevention Fund. Domestic violence is a serious widespread social problem in America: the facts. http://www.endabuse, 2008. [Accessed August 19, 2010].

Family Violence Prevention Fund. The facts on children and domestic violence. http://www.endabuse.org, 2008. [Accessed August 19, 2010].

Galanti, GA. Caring for patients from different cultures, ed 4. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2008.

Giger, JN, Davidhizar, RE. Transcultural nursing: assessment and intervention, ed 5. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

Hanson, SM, et al. Family health care nursing, theory, practice and research, ed 3. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 2005.

Kaakinen, JR, et al. Family health care nursing: theory, practice, and research, ed 4. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 2010.

National Coalition for the Homeless, Homeless families with children: NCH fact sheet. Washington, DC: The Coalition; 2010. http://www.nationalhomeless.org/publications/facts [Accessed August 19, 2010].

Reinhard, SC. Wanted nurses who support caregivers. Am J Nurs. 2006;106(8):13.

Schumacher, K, Beck, C, Marren, JM. Family caregivers. Am J Nurs. 2006;106(8):40.

Stajduhar, KI, et al. Factors influencing family caregivers’ ability to cope with providing end-of-life cancer care at home. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(1):77.

Touhy, TA, Jett, KF. Ebersole and Hess: Gerontological nursing healthy aging, ed 3. St Louis: Mosby; 2010.

US Bureau of the Census, Population profile of the United States: 2008 (Internet release, 2008 update). Washington, DC: The Bureau; 2008. http://www.census.gov [Accessed August 15, 2010].

Research References

Anderson, KH. The family health system approach to family systems nursing. J Fam Nurs. 2000;6(2):103.

Astedt-Kurki, P, et al. Development and testing of a family nursing scale. West J Nurs Res. 2002;24(5):567.

Biello, KB, Sipsma, HL, Kershaw, T. Effect of teenage parenthood on mental health trajectories: does sex matter? Am J Epidemiol. 2010;162(3):279.

Bluvol, A, Ford-Gilboe, M. Hope, health work and quality of life in families of stroke survivors. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48(4):322.

Carruth, AK. Development and testing of the caregiver reciprocity scale. Nurs Res. 1996;45:92.

Duggleby, W, et al. Metasynthesis of the hope experience of family caregivers of persons with chronic illness. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(2):148.

Harper, CC, et al. Abstinence and teenagers: prevention counseling practices of health care providers serving high-risk patients in the United States. Perspect Sexual Reprod Health. 2010;42(2):125.

Hill, EJ. Work-family facilitation and conflict, working fathers and mothers, work-family stressors and support. J Fam Issues. 2005;26(6):793.

Isaksen, AS, Thuen, F, Hanestad, B. Patients with cancer and their close relatives: experiences with treatment, care, and support. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26(1):68.

Joronen, K, Astedt-Kurki, P. Familial contribution to adolescent subjective well-being. Int J Nurs Pract. 2005;11:125.

McCubbin, MA, McCubbin, HI, Thompson, AI. Family Hardiness Index (FHI). In: McCubbin HI, Thompson AI, McCubbin MS, eds. Family assessment: resiliency, coping, and adaptation, inventories for research and practice. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996.

Rosenthal, MS, et al. Family child care provider’s experience in health promotion. Fam Commun Health. 2008;31(4):326.

Schumacher, KL, et al. A transactional model of cancer family caregiving skill. ANS. 2006;29(3):271.

Shpancer, N, et al. Quality of care attributions to employed versus stay-at-home mothers. Early Child Dev Care. 2006;176(2):183.

Tamayo, GJ, et al. Caring for the caregiver. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(1):E50.

Weinert, C, et al. Evolution of a conceptual model for adaptation to chronic illness. J Nurs Scholarship. 2008;40(4):364.