Young and Middle Adults

• Discuss developmental theories of young and middle adults.

• List and discuss major life events of young and middle adults and the childbearing family.

• Describe developmental tasks of the young adult, the childbearing family, and the middle adult.

• Discuss the significance of family in the life of the adult.

• Describe normal physical changes in young and middle adulthood and pregnancy.

• Discuss cognitive and psychosocial changes occurring during the adult years.

• Describe health concerns of the young adult, the childbearing family, and the middle adult.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Young and middle adulthood is a period of challenges, rewards, and crises. Challenges may include the demands of working and raising families, although there are many rewards with these as well. Adults also face crises such as caring for their aging parents, the possibility of job loss in a changing economic environment, and dealing with their own developmental needs and those of their family members.

Classic works by developmental theorists such as Levinson et al (1978), Diekelmann (1976), Erikson (1963, 1982), and Havighurst (1972) attempted to describe the phases of young and middle adulthood and related developmental tasks (see Chapter 11 for an in-depth discussion of developmental theories).

Traditional masculine roles include providing and protecting. However, these roles are now shared with women. Faced with a societal structure that differs greatly from the norms of 20 or 30 years ago, both men and women are assuming different roles in today’s society. Men were traditionally the primary supporter of the family. Today many women pursue careers and contribute significantly to their families’ incomes. In 2006 60% of women participated in the U.S. labor force and constituted 46% of all U.S. workers in the U.S. labor force. Thirty-eight percent of employed women worked in management or professional and related occupations, 34% worked in sales and office occupations; and another 20% worked in service occupations (Business and Professional Women’s Foundation, 2007). However, according to the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) (2008) workers’ union, women in the United States are paid 77.6 cents for every dollar men receive for comparable work.

Developmental theories provide nurses with a basis for understanding the life events and developmental tasks of the young and middle adult. Patients present challenges to nurses who themselves are often young or middle adults coping with the demands of their respective developmental period. Nurses need to recognize the needs of their patients even if they are not experiencing the same challenges and events.

Young Adults

Young adulthood is the period between the late teens and the mid to late 30s (Edelman and Mandle, 2010). In recent years young adults between the ages of 18 and 29 have been referred to as part of the millennial generation. In 2009 young adults made up approximately 33% of the population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). According to the Pew Research Center (2010), today’s young adults are history’s first “always connected” generation, with digital technology and social media major aspects of their lives. They adapt well to new experiences, are more ethnically and racially diverse than previous generations, and are the least overtly religious American generation in modern times. Young adults increasingly move away from their families of origin, establish career goals, and decide whether to marry or remain single and whether to begin families; however, often these goals may be delayed (e.g., because of the economic recession of recent years).

Physical Changes

The young adult usually completes physical growth by the age of 20. An exception to this is the pregnant or lactating woman. The physical, cognitive, and psychosocial changes and the health concerns of the pregnant woman and the childbearing family are extensive.

Young adults are usually quite active, experience severe illnesses less commonly than older age-groups, tend to ignore physical symptoms, and often postpone seeking health care. Physical characteristics of young adults begin to change as middle age approaches. Unless patients have illnesses, assessment findings are generally within normal limits.

Cognitive Changes

Critical thinking habits increase steadily through the young- and middle-adult years. Formal and informal educational experiences, general life experiences, and occupational opportunities dramatically increase the individual’s conceptual, problem-solving, and motor skills.

Identifying an occupational direction is a major task of young adults. When people know their skills, talents, and personality characteristics, educational preparation and occupational choices are easier and more satisfying. A bachelor’s or associate’s degree is the most significant source of postsecondary education for 12 of the 20 fastest-growing occupations.

An understanding of how adults learn helps you to develop patient education plans (see Chapter 25). Adults enter the teaching-learning situation with a background of unique life experiences, including illness. Therefore always view adults as individuals. Their adherence to regimens such as medications, treatments, or lifestyle changes such as smoking cessation involves decision-making processes. When determining the amount of information that an individual needs to make decisions about the prescribed course of therapy, consider factors that possibly affect the individual’s adherence to the regimen, including educational level, socioeconomic factors, and motivation and desire to learn.

Because young adults are continually evolving and adjusting to changes in the home, workplace, and personal lives, their decision-making processes need to be flexible. The more secure young adults are in their roles, the more flexible and open they are to change. Insecure persons tend to be more rigid in making decisions.

Psychosocial Changes

The emotional health of the young adult is related to the individual’s ability to address and resolve personal and social tasks. The young adult is often caught between wanting to prolong the irresponsibility of adolescence and assume adult commitments. However, certain patterns or trends are relatively predictable. Between the ages of 23 and 28, the person refines self-perception and ability for intimacy. From 29 to 34 the person directs enormous energy toward achievement and mastery of the surrounding world. The years from 35 to 43 are a time of vigorous examination of life goals and relationships. People make changes in personal, social, and occupational areas. Often the stresses of this reexamination results in a “midlife crisis” in which marital partner, lifestyle, and occupation change.

Ethnic and gender factors have a sociological and psychological influence in an adult’s life, and these factors pose a distinct challenge for nursing care. Each person holds culture-bound definitions of health and illness. Nurses and other health professionals bring with them distinct practices for the prevention and treatment of illness. Knowing too little about a patient’s self-perception or beliefs regarding health and illness creates conflict between the nurse and the patient. Changes in the traditional role expectations of both men and women in young and middle adulthood also lead to greater challenges for nursing care. For example, women often continue to work during the childrearing years, and many women struggle with the enormity of balancing three careers: wife, mother, and employee. This is a potential source of stress for the adult working woman. Men are more aware of parental and household responsibilities and find themselves having more responsibilities at home while achieving their own career goals (Fortinash and Holoday Worret, 2008). An understanding of ethnicity, race, and gender differences enables a nurse to provide individualized care (see Chapter 9).

Support from a nurse, access to information, and appropriate referrals provide opportunities for achievement of a patient’s potential. Health is not merely the absence of disease but involves wellness in all human dimensions. The nurse acknowledges the importance of the young adult’s psychosocial needs and needs in all other dimensions. The young adult needs to make decisions concerning career, marriage, and parenthood. Although each person makes these decisions based on individual factors, a nurse needs to understand the general principles involved in these aspects of psychosocial development while assessing the young adult’s psychosocial status.

Lifestyle

Family history of cardiovascular, renal, endocrine, or neoplastic disease increases a young adult’s risk of illness. Your role in health promotion is to identify modifiable factors that increase the young adult’s risk for health problems and provide patient education and support to reduce unhealthy lifestyle behaviors (Sanchez et al., 2009).

A personal lifestyle assessment (see Chapter 6) helps nurses and patients identify habits that increase the risk for cardiac, malignant, pulmonary, renal, or other chronic diseases. The assessment includes general life satisfaction, hobbies, and interests; habits such as diet, sleeping, exercise, sexual habits, and use of caffeine, tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs; home conditions and pets; economics, including type of health insurance; occupational environment, including type of work and exposure to hazardous substances; and physical or mental stress. Military records, including dates and geographical area of assignments, may also be useful in assessing the young adult for risk factors. Prolonged stress from lifestyle choices increases wear and tear on the adaptive capacities of the body. Stress-related diseases such as ulcers, emotional disorders, and infections sometimes occur (see Chapter 37).

Career

A successful vocational adjustment is important in the lives of most men and women. Successful employment not only ensures economic security, but it also leads to friendships, social activities, support, and respect from co-workers.

Two-career families are increasing. The two-career family has benefits and liabilities. In addition to increasing the family’s financial base, the person who works outside the home is able to expand friendships, activities, and interests. However, stress exists in a two-career family as well. These stressors result from a transfer to a new city; increased expenditures of physical, mental, or emotional energy; child care demands; or household needs. To avoid stress in a two-career family, partners should share all responsibilities. For example, some families may decide to limit recreational expenses and instead hire someone to do routine housework. Others set up an equal division of household, shopping, and cooking duties.

Sexuality

The development of secondary sex characteristics occurs during the adolescent years (see Chapter 12). Physical development is accompanied by the ability to perform sex acts. The young adult usually has emotional maturity to complement the physical ability and therefore is able to develop mature sexual relationships and establish intimacy. Young adults who have failed to achieve the developmental task of personal integration sometimes develop relationships that are superficial and stereotyped (Fortinash and Holoday Worret, 2008).

Masters and Johnson (1970) contributed important information about the physiological characteristics of the adult sexual response (see Chapter 34). The psychodynamic aspect of sexual activity is as important as the type or frequency of sexual intercourse to young adults. To maintain total wellness, encourage adults to explore various aspects of their sexuality and be aware that their sexual needs and concerns change. As the rate of early initiation of sexual intercourse continues to increase, young adults are at risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Consequently there is an increased need for education regarding the mode of transmission, prevention, and symptom recognition and management for STIs.

Childbearing Cycle

Conception, pregnancy, birth, and the puerperium are major phases of the childbearing cycle. The changes during these phases are complex. Education such as Lamaze classes can prepare pregnant women, their partners, and other support persons to participate in the birthing process (Fig. 13-1). A current trend in some health care agencies is to provide either professional labor support (Sauls, 2006) or a lay doula, a support person to be present during labor to assist women who have no other source of support (Campbell et al., 2006). The stress that many women experience after childbirth has a significant impact on postpartum women’s health (Box 13-1).

Types of Families

During young adulthood most individuals experience singlehood and the opportunity to be on their own. Those who eventually marry encounter several changes as they take on new responsibilities. For example, many married couples choose to become parents (Fig. 13-2). Some young adults choose alternative lifestyles. Chapter 10 reviews forms of families.

Singlehood

Social pressure to get married is not as great as it once was, and many young adults do not marry until their late 20s or early 30s or not at all. For young adults who remain single, parents and siblings become the nucleus for a family. Some view close friends and associates as “family.” One cause for the increased single population is the expanding career opportunities for women. Women enter the job market with greater career potential and have greater opportunities for financial independence. More single individuals are choosing to live together outside of marriage and become parents either biologically or through adoption. Similarly many married couples choose to separate or divorce if they find their marital situation unsatisfactory.

Parenthood

The availability of contraception makes it easier for today’s couples to decide when and if to start a family. Social pressures may encourage a couple to have a child or influence them to limit the number of children they have. Economic considerations frequently enter into the decision-making process because of the expense of childrearing. General health status and age are also considerations in decisions about parenthood because couples are getting married later and postponing pregnancies, which often results in smaller families.

Alternative Family Structures and Parenting

Changing norms and values about family life in the United States reveal basic shifts in attitudes about family structure. The trend toward greater acceptance of cohabitation without marriage is a factor in the greater numbers of infants being born to single women. In addition, approximately 1.5 million parents are gay or lesbian. More than one third of lesbians have given birth, and one in six gay men have fathered or adopted a child. Gay and lesbian parents are raising 3% of foster children in the United States (Gates et al., 2007). The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), in recognizing the needs of gay and lesbian parents and their children, published a policy statement supporting adoption of children and the parenting role by same-sex parents (AAP, 2002). However, many times parents from alternative family structures still feel a lack of support and even bias from the health care system (Makadon, 2006; McManus et al., 2006).

Hallmarks of Emotional Health

Most young adults have the physical and emotional resources and support systems to meet the many challenges, tasks, and responsibilities they face. During psychosocial assessment of young adults, assess for 10 hallmarks of emotional health (Box 13-2) that indicate successful maturation in this developmental stage.

Health Risks

Health risk factors for a young adult originate in the community, lifestyle patterns, and family history. The lifestyle habits that activate the stress response (see Chapter 37) increase the risk of illness. Smoking is a well-documented risk factor for pulmonary, cardiac, and vascular diseases in smokers and the individuals who receive secondhand smoke. Inhaled cigarette pollutants increase the risk of lung cancer, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis. The nicotine in tobacco is a vasoconstrictor that acts on the coronary arteries, increasing the risk of angina, myocardial infarction, and coronary artery disease. Nicotine also causes peripheral vasoconstriction and leads to vascular problems.

Family History

A family history of a disease puts a young adult at risk for developing it in the middle or older adult years. For example, a young man whose father and paternal grandfather had myocardial infarctions (heart attacks) in their 50s has a risk for a future myocardial infarction. The presence of certain chronic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus in the family increases the family member’s risk of developing a disease. Regular physical examinations and screening are necessary at this stage of development.

Personal Hygiene Habits

As in all age-groups, personal hygiene habits in the young adult are risk factors. Sharing eating utensils with a person who has a contagious illness increases the risk of illness. Poor dental hygiene increases the risk of periodontal disease. Individuals avoid gingivitis (inflammation of the gums) and periodontitis (loss of tooth support) through oral hygiene (see Chapter 39).

Violent Death and Injury

Violence is a common cause of mortality and morbidity in the young-adult population. Factors that predispose individuals to violence, injury, or death include poverty, family breakdown, child abuse and neglect, drug involvement (dealing or illegal use), repeated exposure to violence, and ready access to guns. It is important for the nurse to perform a thorough psychosocial assessment, including such factors as behavior patterns, history of physical and substance abuse, education, work history, and social support systems to detect personal and environmental risk factors for violence. Death and injury occur from physical assaults, motor vehicle or other accidents, and suicide attempts. In 2007, homicides occurred at a higher rate among men and people ages 20 to 24 years than other violent deaths (USDHHS, CDC, 2010a).

Intimate partner violence (IPV), formerly referred to as domestic violence, is a global public health problem. It exists along a continuum from a single episode of violence to ongoing battering (USDHHS, CDC, 2009a). IPV often begins with emotional or mental abuse and may progress to physical or sexual assault. Each year women in the United States experience approximately 4.8 million intimate partner–related physical assaults and rapes, and men are the victims of approximately 2.9 intimate partner–related physical assaults. Physical injuries from IPV range from minor cuts and bruises to broken bones, internal bleeding, and head trauma. IPV is linked to such harmful health behaviors as smoking, alcohol abuse, drug use, and risky sexual activity. Risk factors for the perpetration of IPV include using drugs or alcohol, especially drinking heavily; unemployment; low self-esteem; antisocial or borderline personality traits; desire for power and control in relationships; and being a victim of physical or psychological abuse (El-Bassel et al., 2007; Gil-Gonzalez et al., 2008). The greatest risk of violence occurs during the reproductive years. A pregnant woman has a 35.6% greater risk of being a victim of IPV than a nonpregnant woman. Women experiencing IPV may be more likely to delay prenatal care and are at increased risk for multiple poor maternal and infant health outcomes such as low maternal weight gain, infections, high blood pressure, vaginal bleeding, and delivery of a preterm or low-birth-weight infant (NACCHO, 2008).

Substance Abuse

Substance abuse directly or indirectly contributes to mortality and morbidity in young adults. Intoxicated young adults are often severely injured in motor vehicle accidents, resulting in death or permanent disability to other young adults as well.

Dependence on stimulant or depressant drugs sometimes results in death. Overdose of a stimulant drug (“upper”) stresses the cardiovascular and nervous systems to the extent that death occurs. The use of depressants (“downers”) leads to an accidental or intentional overdose and death.

Caffeine is a naturally occurring legal stimulant that is readily available in carbonated beverages; chocolate-containing foods; coffee and tea; and over-the-counter medications such as cold tablets, allergy and analgesic preparations, and appetite suppressants. It is the most widely ingested stimulant in North America. Caffeine stimulates catecholamine release, which in turn stimulates the central nervous system; it also increases gastric acid secretion, heart rate, and basal metabolic rate. This alters blood pressure, increases diuresis, and relaxes smooth muscle. Consumption of large amounts of caffeine results in restlessness, anxiety, irritability, agitation, muscle tremor, sensory disturbances, heart palpitations, nausea or vomiting, and diarrhea in some individuals.

Substance abuse is not always diagnosable, particularly in its early stages. Nonjudgmental questions about use of legal drugs (prescribed drugs, tobacco, and alcohol), soft drugs (marijuana), and more problematic drugs (cocaine or heroin) are a routine part of any health assessment. Obtain important information by making specific inquiries about past medical problems, changes in food intake or sleep patterns, or problems of emotional lability. Reports of arrests because of driving while intoxicated, wife or child abuse, or disorderly conduct are reasons to investigate the possibility of drug abuse more carefully.

Unplanned Pregnancies

Unplanned pregnancies are a continued source of stress that may result in adverse health outcomes for the mother, infant, and family. Often young adults have educational and career goals that take precedence over family development. Interference with these goals affects future relationships and parent-child relationships.

Determination of situational factors that affect the progress and outcome of an unplanned pregnancy is important. Exploration of problems such as financial, career, and living accommodations; family support systems; potential parenting disorders; depression; and coping mechanisms is important in assessing the woman with an unplanned pregnancy.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

STIs are a major health problem in young adults. Examples of STIs include syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, genital herpes, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). STIs have immediate physical effects such as genital discharge, discomfort, and infection. They also lead to chronic disorders, infertility, or even death. They remain a major public health problem for sexually active people, with almost half of all new infections occurring in men and women younger than 24 years of age (USDHHS, CDC, 2009b). In 2008 20- to 24-year-old men had the highest rate of chlamydia among men (1056.1 per 100,000 population); chlamydia rates in men of this age-group increased by 12.6% from the previous year.

Environmental or Occupational Factors

A common environmental or occupational risk factor is exposure to work-related hazards or agents that cause diseases and cancer (Table 13-1). Examples include lung diseases such as silicosis from inhalation of talcum and silicon dust and emphysema from inhalation of smoke. Cancers resulting from occupational exposures may involve the lung, liver, brain, blood, or skin. Questions regarding occupational exposure to hazardous materials should be a routine part of your assessment.

TABLE 13-1

Occupational Hazards/Exposures Associated with Diseases and Cancers

| JOB CATEGORY | OCCUPATIONAL HAZARD/EXPOSURE | WORK-RELATED CONDITION/CANCER |

| Agricultural workers | Pesticides, infectious agents, gases, sunlight | Pesticide poisoning, “farmer’s lung,” skin cancer |

| Anesthetists | Anesthetic gases | Reproductive effects, cancer |

| Automobile workers | Asbestos, plastics, lead, solvents | Asbestosis, dermatitis |

| Carpenters | Wood dust, wood preservatives, adhesives | Nasopharyngeal cancer, dermatitis |

| Cement workers | Cement dust, metals | Dermatitis, bronchitis |

| Dry cleaners | Solvents | Liver disease, dermatitis |

| Dye workers | Dyestuffs, metals, solvents | Bladder cancer, dermatitis |

| Glass workers | Heat, solvents, metal powders | Cataracts |

| Hospital workers | Infectious agents, cleansers, latex gloves, radiation | Infections, latex allergies, unintentional injuries |

| Insulators | Asbestos, fibrous glass | Asbestosis, lung cancer, mesothelioma |

| Jackhammer operators | Vibration | Raynaud’s phenomenon |

| Lathe operators | Metal dusts, cutting oils | Lung disease, cancer |

| Office computer workers | Repetitive wrist motion on computers; eyestrain | Tendonitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, tenosynovitis |

From Stanhope M, Lancaster J: Foundations of nursing in the community, ed 3, St Louis, 2010, Mosby.

Health Concerns

Lifestyles (e.g., use of tobacco or alcohol) of young adults may put them at risk for illnesses or disabilities during their middle- or older-adult years. Young adults are also genetically susceptible to certain chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and familial hypercholesterolemia (Huether and McCance, 2008). Some diseases that may appear in later years are avoidable if identified early. Encourage adults to perform monthly skin, breast, or male genital self-examination (see Chapter 30). Breast cancer is the most common major cancer among women in the United States, with a steadily increasing incidence. A nurse’s role is extremely important in educating female patients about breast self-examinations (BSEs) and the current breast screening recommendations. Encourage routine assessment of the skin for recent changes in color or presence of lesions and changes in their appearance. Prolonged exposure to ultraviolet rays of the sun by adolescents and young adults increase the risk for development of skin cancer later in life. Crohn’s disease, a chronic inflammatory disease of the small intestine, most commonly occurs between 15 and 35 years of age. Many young adults have misconceptions regarding transmission and treatment of STIs. Encourage partners to know one another’s sexual history and practices. Be alert for STIs when patients come to clinics with complaints of urological or gynecological problems (see Chapter 34). Assess young adults for knowledge and use of safe-sex practices and genital self-examinations. Provide information on safe sex practice (e.g., use of condoms and having only one sex partner).

Psychosocial Health

The psychosocial health concerns of the young adult are often related to job and family stressors. As noted in Chapter 37, stress is valuable because it motivates a patient to change. However, if the stress is prolonged and the patient is unable to adapt to the stressor, health problems develop.

Job Stress: Job stress can occur every day or from time to time. Most young adults are able to handle day-to-day crises (Fig. 13-3). Situational job stress occurs when a new boss enters the workplace, a deadline is approaching, or the worker has new or greater numbers of responsibilities. A recent trend in today’s business world and a risk factor for job stress is corporate downsizing, leading to increased responsibilities for employees with fewer positions within the corporate structure. Job stress also occurs when a person becomes dissatisfied with a job or the associated responsibilities. Because individuals perceive jobs differently, the types of job stressors vary from patient to patient. A nurse’s assessment of a young adult includes a description of the usual work performed. Job assessment also includes conditions and hours, duration of employment, changes in sleep or eating habits, and evidence of increased irritability or nervousness.

Family Stress: Because of the multiplicity of changing relationships and structures in the emerging young adult family, stress is frequently high (see Chapter 10). Situational stressors occur during events such as births, deaths, illnesses, marriages, and job losses. Stress is often related to a number of variables, including the career paths of both husband and wife, and leads to dysfunction in the young adult family. This is reflected in the fact that the highest divorce rate occurs during the first 3 to 5 years of marriage for young adults under the age of 30. When a patient seeks health care and presents stress-related symptoms, the nurse needs to assess for the occurrence of a life-change event.

Each family member has certain predictable roles or jobs. These roles enable the family to function and be an effective part of society. When they change as a result of illness, a situational crisis often occurs. Assess environmental and familial factors, including support systems and coping mechanisms commonly used by family members.

Infertility

The term infertility refers to a prolonged time to conceive. An estimated 10% to 15% of reproductive couples are infertile, and many are young adults. However, approximately half of the couples evaluated and treated in infertility clinics become pregnant. In about 15% of infertile couples the cause is unknown. Female factors such as ovulatory dysfunction or a pelvic factor is responsible for infertility in 50% of couples, and infertility in 35% of couples is caused by a male factor such as sperm and semen abnormalities. For some infertile couples a nurse is the first resource they identify. Nursing assessment of the infertile couple includes both comprehensive histories of the male and female partners to determine factors that have affected fertility and pertinent physical findings (Lowdermilk and Perry, 2007).

Obesity

Obesity is a major health problem in young adults and is recognized as a risk factor for other health problems later in life. Obesity, influenced by poor diet and inactivity, has been linked to the development of conditions such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, asthma, joint problems, psoriatic arthritis, and poor health status (Ogdie and Gelfand, 2010; Soltani-Arabshashi et al., 2010; USDHHS, CDC, 2010b). Studies are linking time spent by young adults in sedentary behaviors such as watching television or being on the computer with increased abdominal obesity (Cleland et al, 2008). Nursing assessment of diet and physical activity of young adults is an important part of data collection. All young adults should be counseled about the benefits of a healthful diet and physical activity.

Exercise

People of all ages, both male and female, benefit from regular physical activity (USDHHS, 2002); however, young adults are spending increasingly more time with technology and less time engaged in physical activity. Exercise in young adults is important to prevent or decrease the development of chronic health conditions such as high blood pressure, obesity, and diabetes that develop later in life. Exercise improves cardiopulmonary function by decreasing blood pressure and heart rate; increases the strength and size of muscles; and decreases fatigability, insomnia, tension, and irritability. Conduct a thorough musculoskeletal assessment and exercise history to develop a realistic exercise plan. Encourage regular exercise within the patient’s daily schedule.

Pregnant Woman and Childbearing Family

A developmental task for most young adult couples is the decision to begin a family. Although the physiological changes of pregnancy and childbirth occur only in the woman, cognitive and psychosocial changes and health concerns affect the entire childbearing family, including the baby’s father, siblings, and grandparents. Single-parent families and young single mothers tend to be particularly vulnerable both economically and socially.

Health Practices: Women who are anticipating pregnancy benefit from good health practices before conception; these include a balanced diet, exercise, dental checkups, avoidance of alcohol, and cessation of smoking.

Prenatal Care: Prenatal care is the routine examination of the pregnant woman by an obstetrician or advanced practice nurse such as a nurse practitioner or certified nurse midwife. Prenatal care includes a thorough physical assessment of the pregnant woman during regularly scheduled intervals; provision of information regarding STIs, other vaginal infections, and urinary infections that adversely affect the fetus; and counseling about exercise patterns, diet, and child care. Regular prenatal care addresses health concerns that may arise during the pregnancy.

Physiological Changes: The physiological changes and needs of the pregnant woman vary with each trimester. Be familiar with them, their causes, and implications for nursing. All women experience some physiological changes in the first trimester. For example, they commonly have morning sickness, breast enlargement and tenderness, and fatigue. During the second trimester growth of the uterus and fetus results in some of the physical signs of pregnancy. During the third trimester increases in Braxton Hicks contractions (irregular, short contractions), fatigue, and urinary frequency occur.

Puerperium: The puerperium is a period of approximately 6 weeks after delivery. During this time the woman’s body reverts to its prepregnant physical status. Determine the woman’s knowledge of and ability to care for both herself and for her newborn baby. Assessment of parenting skills and maternal-infant interactions is particularly important. The process of lactation or breastfeeding offers many advantages to both the new mother and baby. For the inexperienced mother breastfeeding can be a source of anxiety and frustration. Be alert for signs that the mother needs information and assistance (Dunn et al., 2006).

Needs for Education: The entire childbearing family needs education about pregnancy, labor, delivery, breastfeeding, and integration of the newborn into the family structure.

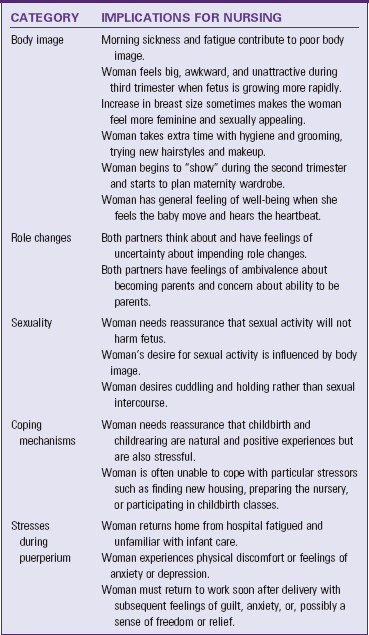

Psychosocial Changes: Like the physiological changes of pregnancy, psychosocial changes occur at various times during the 9 months of pregnancy and in the puerperium. Table 13-2 summarizes the major categories of psychosocial changes and implications for nursing intervention.

Acute Care

Young adults typically require acute care for accidents, substance abuse, exposure to environmental and occupational hazards, stress-related illnesses, respiratory infections, gastroenteritis, influenza, urinary tract infections, and minor surgery. An acute minor illness causes a disruption in life activities of young adults and increases stress in an already hectic lifestyle. Dependency and limitations posed by treatment regimens also increase frustration. To give them a sense of maintaining control of their health care choices, it is important to keep them informed about their health status and involve them in health care decisions.

Restorative and Continuing Care

Chronic conditions are not common in young adulthood, but they sometimes occur. Chronic illnesses such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, and diabetes have their onset in young adulthood but may not be recognized until later in life. Causes of chronic illness and disability in the young adult include accidents, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, AIDS, and cancer. Chronic illness or disability threatens a young adult’s independence and results in the need to change personal, family, and career goals. Nursing interventions for the young adult faced with chronic illness or disability need to focus on problems related to sense of identity, establishing independence, reorganizing intimate relationships and family structure, and launching a chosen career (Santacroce and Lee, 2006).

Middle Adults

In 2009 39.8% of the population was middle-age adults between the ages of 35 and 64, a slight increase over the 2005 data (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). In middle adulthood the individual makes lasting contributions through involvement with others. Generally the middle-adult years begin around the early to mid 30s and last through the late 60s, corresponding to Levinson’s developmental phases of “settling down” and the “payoff years.” During this period personal and career achievements have often already been experienced. Many middle adults find particular joy in helping their children and other young people become productive and responsible adults (Fig. 13-4). They also begin to help aging parents while being responsible for their own children, placing them in the sandwich generation. Using leisure time in satisfying and creative ways is a challenge that, if met satisfactorily, enables middle adults to prepare for retirement.

Although most middle adults have achieved socioeconomic stability, recent trends in corporate downsizing have left many either jobless or forced to accept lower-paying jobs. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2009), the real median household income in the United States fell 3.6% between 2007 and 2008, and the number of people without health insurance coverage rose from 45.7 million in 2007 to 46.3 million in 2008. As a result, a greater proportion of the population became unable to afford adequate health care.

Men and women need to adjust to inevitable biological changes. As in adolescence, middle adults use considerable energy to adapt self-concept and body image to physiological realities and changes in physical appearance. High self-esteem, a favorable body image, and a positive attitude toward physiological changes occur when adults engage in physical exercise, balanced diets, adequate sleep, and good hygiene practices that promote vigorous, healthy bodies.

Physical Changes

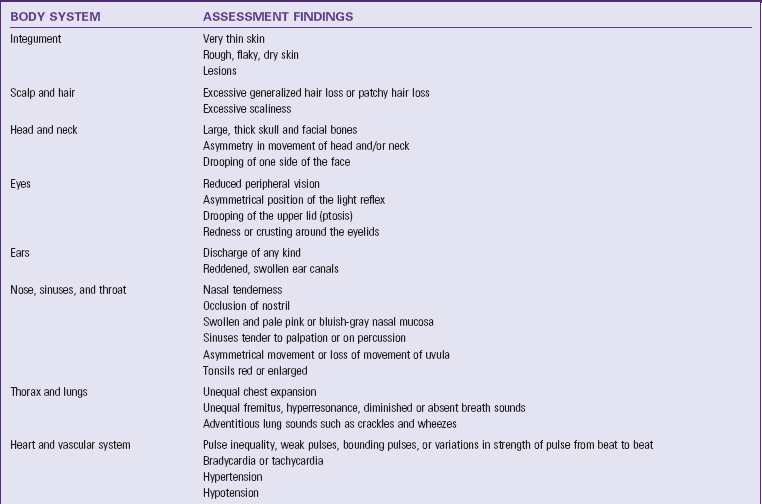

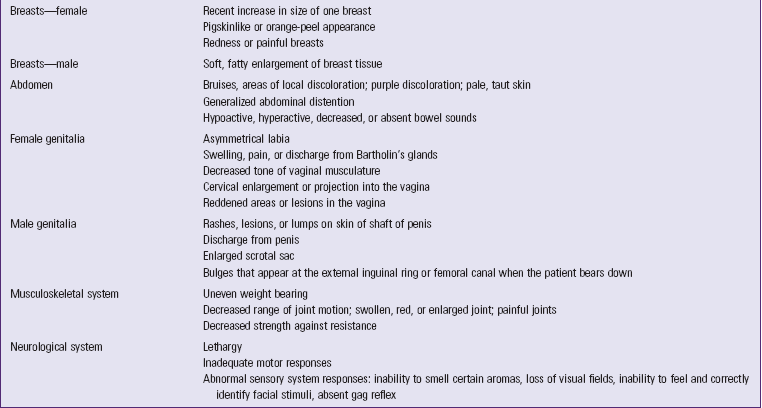

Major physiological changes occur between 40 and 65 years of age. Because of this it is important to assess the middle adult’s general health status. A comprehensive assessment offers direction for health promotion recommendations and planning and implementing any acutely needed interventions. The most visible changes during middle adulthood are graying of the hair, wrinkling of the skin, and thickening of the waist. Decreases in hearing and visual acuity are often evident during this period. Often these physiological changes during middle adulthood have an impact on self-concept and body image. Table 13-3 summarizes abnormal findings to consider when conducting a physical examination (see Chapter 30). The most significant physiological changes during middle age are menopause in women and the climacteric in men.

Perimenopause and Menopause

Menstruation and ovulation occur in a cyclical rhythm in women from adolescence into middle adulthood. Perimenopause is the period during which ovarian function declines, resulting in a diminishing number of ova and irregular menstrual cycles, and generally lasts 1 to 3 years. Menopause is the disruption of this cycle, primarily because of the inability of the neurohormonal system to maintain its periodic stimulation of the endocrine system. The ovaries no longer produce estrogen and progesterone, and the blood levels of these hormones drop markedly. Menopause typically occurs between 45 and 60 years of age (see Chapter 34). Approximately 10% of women have no symptoms of menopause other than cessation of menstruation, 70% to 80% are aware of other changes but have no problems, and approximately 10% experience changes severe enough to interfere with activities of daily living.

Climacteric

The climacteric occurs in men in their late 40s or early 50s (see Chapter 34). Decreased levels of androgens cause climacteric. Throughout this period and thereafter a man is still capable of producing fertile sperm and fathering a child. However, penile erection is less firm, ejaculation is less frequent, and the refractory period is longer.

Cognitive Changes

Changes in the cognitive function of middle adults are rare except with illness or trauma. Some middle adults enter educational or vocational programs to prepare themselves with new skills and information for entering the job market or changing jobs.

Psychosocial Changes

The psychosocial changes in the middle adult involve expected events such as children moving away from home and unexpected events such as a marital separation or the death of a close friend.

The nurse assesses major life changes occurring in any middle adult for whom he or she cares and the impact that the changes have on that person’s state of health. Individual psychosocial factors such as coping mechanisms and sources of social support should also be included in the assessment.

In the middle-adult years, as children depart from the household, the family enters the postparental family stage. Time and financial demands on the parents decrease, and the couple faces the task of redefining their own relationship. It is during this period that many middle adults take on healthier lifestyles. Assessment of health promotion needs for the middle adult includes adequate rest, leisure activities, regular exercise, good nutrition, reduction or cessation in the use of tobacco or alcohol, and regular screening examinations. Assessment of the middle adult’s social environment is also important, including relationship concerns; communication and relationships with children, grandchildren, and aging parents; and caregiver concerns with their own aging or disabled parents.

Career Transition

Career changes occur by choice or as a result of changes in the workplace or society. In recent decades middle adults change occupations more often for a variety of reasons, including limited upward mobility, decreasing availability of jobs, and seeking an occupation that is more challenging. In some cases downsizing, technological advances, or other changes force middle adults to seek new jobs. Such changes, particularly when unanticipated, result in stress that affects health, family relationships, self-concept, and other dimensions.

Sexuality

After the departure of their last child from the home, many couples recultivate their relationships and find increased marital and sexual satisfaction during middle age. The onset of menopause and the climacteric affect the sexual health of the middle adult. Some women may desire increased sexual activity because pregnancy is no longer possible. Menopausal women also experience vaginal dryness and dyspareunia or pain during sexual intercourse (see Chapter 34).

During middle age a man may notice changes in the strength of his erection and a decrease in his ability to experience repeated orgasm. Other factors influencing sexuality during this period include work stress, diminished health of one or both partners, and the use of prescription medications. For example, antihypertensive agents have side effects that influence sexual desire or functioning. Sometimes both partners experience stresses related to sexual changes or a conflict between their sexual needs and self-perceptions and social attitudes or expectations (see Chapter 34).

Family Psychosocial Factors

Psychosocial factors involving the family include the stresses of singlehood, marital changes, transition of the family as children leave home, and the care of aging parents.

Singlehood: Many adults over 35 years of age in the United States have never been married. Many of these are college-educated people who have embraced the philosophy of choice and freedom, delayed marriage, and delayed parenthood. Some middle adults choose to remain single but also opt to become parents either biologically or through adoption. Many single middle adults have no relatives but share a family type of relationship with close friends or work associates. Consequently some single middle adults feel isolated during traditional “family” holidays such as Thanksgiving or Christmas. In times of illness middle adults who have chosen to remain single and childless have to rely on other relatives or friends, increasing caregiving demands of family members who also have other responsibilities. Nursing assessment of single middle adults needs to include a thorough assessment of psychosocial factors, including the individual’s definition of family and available support systems.

Marital Changes: Marital changes occurring during middle age include death of a spouse, separation, divorce, and the choice of remarrying or remaining single. A widowed, separated, or divorced patient goes through a period of grief and loss in which it is necessary to adapt to the change in marital status. Normal grieving progresses through a series of phases, and resolution of grief often takes a year or more. You need to assess the level of coping of the middle adult to the grief and loss associated with certain life changes (see Chapter 36).

Family Transitions: The departure of the last child from the home is also a stressor. Many parents welcome freedom from childrearing responsibilities, whereas others feel lonely or without direction. Empty nest syndrome is the term used to describe the sadness and loneliness that accompany children leaving home. Eventually parents need to reassess their marriage and try to resolve conflicts and plan for the future. Occasionally this readjustment phase leads to marital conflicts, separation, and divorce (see Chapter 10).

Care of Aging Parents: Increasing life spans in the United States and Canada have led to increased numbers of older adults in the population. Therefore greater numbers of middle adults need to address the personal and social issues confronting their aging parents. Many middle adults find themselves caught between the responsibilities of caring for dependent children and those of caring for aging and ailing parents. These middle adults thus find themselves in the sandwich generation, in which the challenges of caregiving can be stressful. The needs of family caregivers are being given more emphasis in the health care system.

Housing, employment, health, and economic realities have changed the traditional social expectations between generations in families. The middle adult and older-adult parent often have conflicting relationship priorities while the older adult strives to remain independent. Negotiations and compromises help to define and resolve problems. Nurses deal with middle and older adults in the community, long-term care facilities, and hospitals. Help identify the health needs of both groups and assist the multigenerational family in determining the health and community resources available to them as they make decisions and plans. Evaluate family relationships to determine family members’ perceptions of responsibility and loyalty in relation to caring for older-adult members. Assessment of environmental resources (e.g., number of rooms in the house or stairwells) in relation to the complexity of health care demands for the older adult is also important.

Health Concerns

Health Promotion and Stress Reduction

Because middle adults experience physiological changes and face certain health realities, their perceptions of health and health behaviors are often important factors in maintaining health. Today’s complex world makes individuals more prone to stress-related illnesses such as heart attacks, hypertension, migraine headaches, ulcers, colitis, autoimmune disease, backache, arthritis, and cancer. When adults seek health care, nurses focus on the goal of wellness and guide patients to evaluate health behaviors, lifestyle, and environment.

Throughout life people have many stressors (see Chapter 37). After identifying these stressors, work with the patient to intervene and modify the stress response. Specific interventions for stress reduction fall into three categories. First minimize the frequency of stress-producing situations. Together with the patient identify approaches to preventing stressful situations such as habituation, change avoidance, time blocking, time management, and environmental modification. Second, increase stress resistance such as increasing self-esteem, improving assertiveness, redirecting goal alternatives, and reorienting cognitive appraisal. Finally, avoid the physiological response to stress. Use relaxation techniques, imagery, and biofeedback to recondition the patient’s response to stress. Chapters 36 and 37 explain these general interventions in greater detail.

Obesity

Obesity is a growing, expensive health concern for middle adults. It can reduce quality of life and increases risk for many serious chronic diseases and premature death. In 2007 no state in the United States had met the Healthy People 2010 objective to reduce obesity prevalence among adults to 15% (USDHHS, CDC, 2010b). Health consequences of obesity include such ailments as high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, type 2 (noninsulin dependent) diabetes, coronary heart disease, osteoarthritis, and obstructive sleep apnea. Continued focus on the goal of wellness helps patients evaluate health behaviors and lifestyle that contribute to obesity during the middle adult years. Counseling related to physical activity and nutrition is an important component of the plan of care for overweight and obese patients.

Forming Positive Health Habits

A habit is a person’s usual practice or manner of behavior. Frequent repetition reinforces this behavior pattern until it becomes the individual’s customary way of behaving. Some habits support health such as exercise and brushing and flossing the teeth each day. Other habits involve risk factors to health such as smoking or eating foods with little or no nutritional value.

During assessment a nurse frequently obtains data indicating positive and negative health behaviors by a patient. Examples of positive health behaviors include regular exercise, adherence to good dietary habits, avoidance of excess consumption of alcohol, participation in routine screening and diagnostic tests (e.g., laboratory screening for serum cholesterol or mammography) for disease prevention and health promotion, and lifestyle changes to reduce stress. The nurse helps the patient maintain habits that protect health and offers healthier alternatives to poor habits.

Health teaching and counseling often focus on improving health habits. The more you understand the dynamics of behavior and habits, the more likely it is that your interventions will help patients achieve or reinforce health-promoting behaviors.

To help patients form positive health habits, you act as a teacher and facilitator. By providing information about how the body functions and how patients form and change habits, patients’ levels of knowledge regarding the potential impact of behavior on health are raised. You cannot change your patients’ habits. They have control of and are responsible for their own behaviors. Explain psychological principles of changing habits and offer information about health risks. Offer positive reinforcement (such as praise and rewards) for health-directed behaviors and decisions. Such reinforcement increases the likelihood that the behavior will be repeated. However, ultimately the patient decides which behaviors will become habits of daily living.

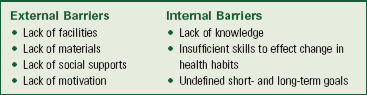

Help middle adults consider factors such as prevention of STIs, substance abuse, and accident prevention in relation to decreasing health risks. For example, provide patients with factual information on STI causes, symptoms, and transmission. Discuss methods of protection during sexual activity with a patient in an open and nonjudgmental manner and reinforce the importance of practicing safe sex (see Chapter 34). Provide counseling and support for patients seeking treatment for substance abuse. Help them recognize and alter unsafe and potential health hazards. In addition, encourage them to express their feelings so they become proficient in solving problems and recognizing risk factors themselves. Barriers to change exist (Box 13-3). Unless you minimize or eliminate these barriers, it is futile to encourage the patient to take action.

Psychosocial Health

Anxiety: Anxiety is a critical maturational phenomenon related to change, conflict, and perceived control of the environment. Adults often experience anxiety in response to the physiological and psychosocial changes of middle age. Such anxiety motivates the adult to rethink life goals and stimulates productivity. However, for some adults this anxiety precipitates psychosomatic illness and preoccupation with death. In this case the middle adult views life as being half or more over and thinks in terms of the time left to live.

Clearly a life-threatening illness, marital transition, or job stressor increases the anxiety of a patient and family. Use crisis intervention or stress-management techniques to help a patient adapt to the changes of the middle-adult years (see Chapter 37).

Depression: Depression is a mood disorder that manifests itself in many ways. Although the most frequent age of onset is between ages 25 and 44, it is common among adults in the middle years and has many causes. The risk factors for depression include being female; disappointments or losses at work, at school, or in family relationships; departure of the last child from the home; and family history. In fact, the incidence of depression in women is twice that of men. Persons experiencing mild depression describe themselves as feeling sad, blue, downcast, down in the dumps, and tearful. Other symptoms include alterations in sleep patterns such as difficulty in sleeping (insomnia) or sleeping too much (hypersomnia), irritability, feelings of social disinterest, and decreased alertness. Physical changes such as weight gain or loss, headaches, or feelings of fatigue regardless of the amount of rest are also depressive symptoms. Individuals with depression that occurs during the middle years commonly experience moderate-to-high anxiety and have physical complaints. Mood changes and depression are common occurrences during menopause. The abuse of alcohol or other substances makes depression worse. Nursing assessment of the depressed middle adult includes focused data collection regarding individual and family history of depression, mood changes, cognitive changes, behavioral and social changes, and physical changes. Collect assessment data from both the patient and the patient’s family because family data are often particularly important, depending on the level of depression the middle adult is experiencing.

Community Health Programs

Community health programs offer services to prevent illness, promote health, and detect disease in the early stages. Nurses make valuable contributions to the health of the community by taking an active part in planning screening and teaching programs and support groups for middle adults.

Family planning, birthing, and parenting skills are program topics in which adults are usually interested. Health screening for diabetes, hypertension, eye disease, and cancer is a good opportunity for the nurse to perform assessment and provide health teaching and health counseling.

Health education programs promote changes in behavior and lifestyle. As a health teacher, offer information that enables patients to make decisions about health practices within the context of health promotion for young-to-middle adults. Make sure that educational programs are culturally appropriate. Changes to more positive health practices during young and middle adulthood lead to fewer or less complicated health problems as an older adult. During health counseling, collaborate with the patient to design a plan of action that addresses the patient’s health and well-being. Through objective problem solving, you can help the patient grow and change.

Acute Care

Acute illnesses and conditions experienced in middle adulthood are similar to those of young adulthood. However, injuries and acute illnesses in middle adulthood require a longer recovery period because of the slowing of healing processes. In addition, acute illnesses and injuries experienced in middle adulthood are more likely to become chronic conditions. For middle adults in the sandwich generation, stress levels also increase as he or she tries to balance responsibilities related to employment, family life, care of children, and care of aging parents while recovering from an injury or acute illness.

Restorative and Continuing Care

Chronic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis, or multiple sclerosis affect the roles and responsibilities of the middle adult. Some results of chronic illness are strained family relationships, modifications in family activities, increased health care tasks, increased financial stress, the need for housing adaptation, social isolation, medical concerns, and grieving. The degree of disability and the patient’s perception of both the illness and the disability determine the extent to which lifestyle changes occur. A few examples of the problems experienced by patients who develop debilitating chronic illness during adulthood include role reversal, changes in sexual behavior, and alterations in self-image. Along with the current health status of the chronically ill middle adult, you need to assess the knowledge base of both the patient and family. This assessment includes the medical course of the illness and the prognosis for the patient. In addition, you must determine the coping mechanisms of the patient and family; adherence to treatment and rehabilitation regimens; and the need for community and social services, along with appropriate referrals.

Key Points

• Adult development involves orderly and sequential changes in characteristics and attitudes that adults experience over time.

• Many changes experienced by the young adult are related to the natural process of maturation and socialization.

• Young adults are in a stable period of physical development, except for changes related to pregnancy.

• Cognitive development continues throughout the young- and middle-adult years.

• Emotional health of young adults is correlated with the ability to address and resolve personal and social problems.

• Young adults choose a career and decide whether to remain single or marry and begin a family.

• Pregnant women need to understand physiological changes occurring in each trimester.

• Psychosocial changes and health concerns during pregnancy and the puerperium affect the parents, the siblings, and often the extended family.

• Prenatal care reduces maternal and fetal mortality and morbidity.

• Midlife transition begins when a person becomes aware that physiological and psychosocial changes signify passage to another stage in life.

• Two significant physiological changes of the middle years are menopause in women and the climacteric in men.

• Cognitive changes are rare in middle age except in cases of illness or physical trauma.

• Psychosocial changes for middle adults are often related to career transition, sexuality, marital changes, family transition, and care of aging parents.

• Health concerns of middle adults commonly involve stress-related illnesses, health assessment, and adoption of positive health habits.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

A 24-year-old female patient who smokes two packs of cigarettes per day has come to the clinic to talk with the nurse about quitting smoking. She began smoking when she was 14 years old. She complains to the nurse at the clinic, “I just can’t seem to kick the habit no matter how hard I try. I am smoking more now because of increased stress from my job.”

1. What information does the nurse need to know to help this patient quit smoking?

2. Which factors will have the greatest impact on health promotion related to smoking cessation in this patient?

3. What steps should the nurse take to help this patient decrease her stress?

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. With the exception of pregnant or lactating women, the young adult has usually completed physical growth by the age of:

2. The nurse is completing an assessment on a male patient, age 24. Following the assessment, the nurse notes that his physical and laboratory findings are within normal limits. Because of these findings, nursing interventions are directed toward activities related to:

1. Instructing him to return in 2 years.

2. Instructing him in secondary prevention.

3. When determining the amount of information that a patient needs to make decisions about the prescribed course of therapy, many factors affect the patient’s compliance with the regimen, including educational level and socioeconomic factors. Which additional factor affects compliance?

4. A patient is laboring with her first baby, which is coming 2 weeks early. Her husband is in the military and might not get back in time, and both families are unable to be with her during labor. The doctor decides to call in which of the following people employed by the birthing area to be a support person to be present during labor?

5. A single young adult female interacts with a group of close friends from college and work. They celebrate birthdays and holidays together. In addition, they help one another through many stressors. She views these individuals as:

6. Sharing eating utensils with a person who has a contagious illness increases the risk of illness. This type of health risk arises from:

7. A 50-year-old woman has elevated cholesterol profile values that increase her cardiovascular risk factor. One method to control this risk factor is to identify current diet trends and describe dietary changes to reduce the risk. This nursing activity is a form of:

8. A 34-year-old female executive has a job with frequent deadlines. She notes that, when the deadlines appear, she has a tendency to eat high-fat, high-carbohydrate foods. She also explains that she gets frequent headaches and stomach pain during these deadlines. The nurse provides a number of options for the executive, and she chooses yoga. In this scenario yoga is used as a(n):

9. A 50-year-old male patient is seen in the clinic. He tells the nurse that he has recently lost his job and his wife of 26 years has asked for a divorce. He has a flat affect. Family history reveals that his father committed suicide at the age of 53. The nurse should assess for the following:

10. Middle-age adults frequently find themselves trying to balance responsibilities related to employment, family life, care of children, and care of aging parents. People finding themselves in this situation are frequently referred to as being a part of:

11. Intimate partner violence (IPV) is linked to which of the following factors? (Select all that apply.)

12. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) continue to be a major health problem in young adults. Men ages 20 to 24 years have the highest rate of which STI?

13. Formation of positive health habits may prevent the development of chronic illness later in life. Which of the following are examples of positive health habits? (Select all that apply.)

14. Chronic illness (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis) may affect a person’s roles and responsibilities during middle adulthood. When assessing the knowledge base of both the middle-age patient with a chronic illness and his family, the assessment should include which of the following? (Select all that apply.)

1. The medical course of the illness

2. The prognosis for the patient

15. A 45-year-old obese woman tells the nurse that she wants to lose weight. After conducting a thorough assessment, the nurse concludes that which of the following may be contributing factors to the woman’s obesity? (Select all that apply.)

1. The woman works in an executive position that is very demanding.

2. The woman works out at the corporate gym at 5 am two mornings per week

3. The woman says that she has little time to prepare meals at home and eats out at least four nights a week.

4. The woman says that she tries to eat “low cholesterol” foods to help lose weight.

Answers: 1. 2; 2. 3; 3. 3; 4. 4; 5. 1; 6. 4; 7. 3; 8. 4; 9. 2; 10. 1; 11. 1, 2, 3, 4; 12. 1; 13. 1, 3; 14. 1, 2, 3, 4; 15. 1, 3.

References

AFL-CIO. AFL-CIO celebrates international women’s day. http://www.aflcio.org/mediacenter/prsptm/pr03072008a.cfm, March 7, 2008. [Accessed July 15, 2011].

American Academy of Pediatrics, Technical report: coparent or second-parent adoption by same-sex parents. Pediatrics 2002;109(2):341. http://www.aappolicy.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/pediatrics;102/2/339 [Accessed October 12, 2011].

Beacham, T, et al. Assessing postpartum depression in women. Home Healthcare Nurse. October 2008;26(9):553.

Beck, C. Postpartum depression: it isn’t just the blues. Am J Nurs. 2006;106(5):40.

Business and Professional Women’s Foundation. 101 facts on the status of working women. http://www.bpusa.org/files/public/101factsPct07.pdf, October 2007. [Accessed July 15, 2011].

Diekelmann, J. The young adult: the choice is health or illness. Am J Nurs. 1976;76:1276.

Dunn, S, et al. The relationship between vulnerability factors and breastfeeding outcome. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(1):87.

Edelman, C, Mandle, C. Health promotion throughout the life span, ed 7. St Louis: Mosby; 2010.

Erikson, E. Childhood society, ed 2. New York: WW Norton; 1963.

Erikson, E. The lifecycle completed: a review. New York: WW Norton; 1982.

Fortinash, K, Holoday Worret, P. Psychiatric mental health nursing, ed 4. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

Gates, G, et al. Adoption and foster care by gay and lesbian parents in the United States, The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. http://www.law.ucla.edu/williamsinstitute/publications/FinalAdoptionReport.pdf, March 2007. [Accessed July 15, 2011].

Gil-Gonzalez, D, et al. Childhood experiences of violence in perpetrators as a risk factor of intimate partner violence: a systematic review. J Public Health. 2008;30(1):14.

Havighurst, R. Successful aging. In: Williams, RH, Tibbits, C, Donahue, W, eds. Process of aging, vol 1. New York: Atherton; 1972.

Huether, S, McCance, K. Understanding pathophysiology, ed 4. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

Knitzer, J, Theberge, S, Johnson, K. Reducing maternal depression and its impact on young children, National Center for Children in Poverty, Project THRIVE, Issue Brief No. 2. http://www.nccp.org/publications/pdf/text_791.pdf, January 2008.

Levinson, D, et al. The seasons of a man’s life. New York: Knopf; 1978.

Lowdermilk, D, Perry, S. Maternity and women’s health care, ed 9. St Louis: Mosby; 2007.

Makadon, H. Improving health care for the lesbian and gay communities. N Eng J Med. 2006;354:895.

Masters, W, Johnson, V. Human sexual response. Boston: Little, Brown; 1970.

National Association of County & City Health Officials (NACCHO). Intimate partner violence among pregnant and parenting women: local health department strategies for assessment, intervention, and prevention. http://naccho.org/, 2008. [Washington, D.C. Accessed July 15, 2011].

Pew Research Center. Millennials: a portrait of generation. http://pewsocialtrends.org/assets/pdf/millennials-confident-connected-open-to-change.pdf, February 2010. [Accessed July 15, 2011].

Sanchez, A, et al, Modeling innovative interventions for optimizing healthy lifestyle promotion in primary care. BMC Health Services Research 2009;9(103). http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1472-6963-9-103.pdf [Accessed July 15, 2011].

US Census Bureau. Income, poverty and health insurance coverage in the United States, 2008. http://www.census.gov/prod/2009pubs/p60-236.pdf, September 2009. [Accessed July 15, 2011].

US Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the white alone or in combination resident population by sex and age for the United States, April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2009 (NC-EST2009-04-WAC). http://www.census.gov/popest/national/asrh/NC-EST2009-asrh.html, August 2010. [Accessed July 15, 2011].

US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS). Healthy People 2010, ed 2. McLean, Va: International Medical Publishing; 2002.

US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Understanding intimate partner violence fact sheet. http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/IPV_factsheet-a.pdf, 2009. [Accessed July 15, 2011].

US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2008. http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats08/surv2008-Complete.pdf, November 2009. [Accessed July 15, 2011].

US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Surveillance for violent deaths—national violent death reporting system, 16 states, 2007. MMWR 2010;59(No SS-4). May 14 www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/ss/ss5904.pdf [Accessed July 15, 2011].

US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: State-specific prevalence of obesity among adults—United States, 2009. MMWR. 2010;59:1. [early release August 3].

US Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF). Screening for depression in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(11):784.

Research References

Akincigil, A, et al. Predictors of maternal depression in the first year postpartum: marital status and mediating role of relationship quality. Soc Work Health Care. 2010;49(3):227.

Bei, B, et al. Subjective perception of sleep, but not its objective quality, is association with immediate postpartum mood disturbances in health women. Sleep. 2010;33(4):531.

Campbell, DA, et al. A randomized control trial of continuous support in labor by a lay doula. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(4):456.

Cleland, V, et al. Television viewing and abdominal obesity in young adults: is the association mediated by food and beverage consumption during viewing time or reduced leisure-time physical activity? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1148.

Doucet, S, et al. Differentiation and clinical implications of postpartum depression and postpartum psychosis. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38(3):269.

El-Bassel, N, et al. Perpetration of intimate partner violence among men in methadone treatment programs in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1230.

McManus, A, et al. Lesbian experiences and needs during childbirth: guidance for health care providers. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(1):13.

Ogdie, A, Gelfand, J. Identification of risk factors for psoriatic arthritis: scientific opportunity meets clinical need. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:785.

Poobalan, A, et al. Effects of treating postnatal depression on mother-infant interaction and child development. Br J Psych. 2007;191:378.

Records, K, et al. Psychometric assessment of the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory-Revised. J Nurs Measurement. 2007;15(3):189.

Robertson, K. Understanding the needs of women with postnatal depression. Nurs Stand. 2010;24(46):47.

Santacroce, SJ, Lee, YL. Uncertainty, posttraumatic stress, and health behavior in young adult childhood cancer survivors. Nurs Res. 2006;55(4):259.

Sauls, DJ. Dimensions of professional labor support for intrapartum practice. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006;38(1):36.

Soltani-Arabshashi, R, et al. Obesity in early adulthood as a risk for psoriatic arthritis. Arch Derm. 2010;146(7):721.