The Experience of Loss, Death, and Grief

• Identify the nurse’s role when caring for patients who are experiencing loss, grief, or death.

• Describe the types of loss experienced throughout life.

• Describe characteristics of a person experiencing grief.

• Discuss variables that influence a person’s response to grief.

• Develop a nursing care plan for a patient and family experiencing loss and grief.

• Identify ways to collaborate with family members and the interdisciplinary team to provide palliative care.

• Describe interventions for symptom management in patients at the end of life.

• Discuss the criteria for hospice care.

• Describe care of the body after death.

• Discuss the nurse’s own grief experience when caring for dying patients.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Nurses have a primary duty to prevent illness and injury and help patients return to health. They also play a vital role in helping patients and families cope with things that cannot be changed and facilitate a peaceful death. Patients and families need expert nursing care through grief and death, perhaps more than at any other time. Caring for patients at the end of life requires knowledge and caring to bring comfort, even when the hope for cure or continued life is not possible. Although specialized roles and a sophisticated knowledge base for palliative and hospice care nurses have expanded greatly in the last two decades, nurses in all settings (i.e., residential facilities, hospitals, nursing homes, critical care units, and home health) provide most of the care for the seriously ill and dying.

Despite the pervasiveness of serious chronic illness and the high incidence of death in health care settings, many health care professionals feel apprehensive about providing end-of-life care (Weigel et al., 2007). Talking openly about death is discouraged in American society (i.e., in our everyday lives, our language, and even our thinking) (Matzo and Sherman, 2010). Terminal illness reminds friends and family members of their own mortality, which often causes them, sometimes unconsciously, to withdraw from the dying person. Nurses also grieve when witnessing the suffering of others.

You need to know that you are capable of providing the asset most valued by patients and family members at the end of life: a compassionate, attentive, and patient-centered approach to care. With each experience of caring for people at the end of life, you gain more confidence, courage, and compassion to accompany patients and family members through this intimate and meaningful phase of human transition. Your skills and knowledge base develop quickly if you have the desire and willingness to learn, be present, and seek the help needed to learn how to give excellent care at the end of life.

Scientific Knowledge Base

Throughout a lifetime people grieve the loss of multiple things: body parts or function, self-esteem, friendships, confidence, or income. Children develop independence from the adults who raise them, begin and leave school, change friends, begin careers, and form new relationships. From birth to death people form attachments and suffer losses. Illness also changes or threatens a person’s identity, and at some point everyone dies. People experience loss when another person, possession, body part, familiar environment, or sense of self changes or is no longer present (Table 36-1). The values learned in one’s family, religious community, society, and culture shape what a person regards as loss and how to grieve (Walter and McCoyd, 2009).

TABLE 36-1

| DEFINITION | IMPLICATIONS OF LOSS |

| Loss of possessions or objects (e.g., theft, deterioration, misplacement, or destruction) | Extent of grieving depends on value of object, sentiment attached to it, or its usefulness. |

| Loss of known environment (e.g., leaving home, hospitalization, new job, moving out of a rehabilitation unit) | Loss occurs through maturational or situational events or by injury/illness. Loneliness in an unfamiliar setting threatens self-esteem, hopefulness, or belonging. |

| Loss of a significant other (e.g., divorce, loss of friend, trusted caregiver, or pet) | Close friends, family members, and pets fulfill psychological, safety, love, belonging, and self-esteem needs. |

| Loss of an aspect of self (e.g., body part, job, psychological or physiological function) | Illness, injury, or developmental changes result in loss of a valued aspect of self, altering personal identity and self-concept. |

| Loss of life (e.g., death of family member, friend, co-worker, or one’s own death) | Loss of life grieves those left behind. Dying persons also feel sadness or fear pain, loss of control, and dependency on others. |

Life changes are natural and often positive. As people move forward in life, they learn that change always involves a necessary loss, which is a part of life. They learn to expect that most necessary losses are eventually replaced by something different or better. However, some losses cause them to undergo permanent changes in their lives and threaten their sense of belonging and security. The death of a loved one, divorce, or loss of independence changes life forever and often significantly disrupts a person’s physical, psychological, and spiritual health. A maturational loss is a form of necessary loss and includes all normally expected life changes across the life span. A mother feels loss when her child leaves home for the first day of school. A grade school child does not want to lose her favorite teacher and classroom. Maturational losses associated with normal life transitions help people develop coping skills to use when they experience unplanned, unwanted, or unexpected loss. Some losses seem unnecessary and are not part of expected maturation experiences. Sudden, unpredictable external events bring about situational loss. For example, a person in an automobile accident sustains an injury with physical changes that make it impossible to return to work or school, leading to loss of function, income, life goals, and self-esteem.

Losses may be actual or perceived. An actual loss occurs when a person can no longer feel, hear, see, or know a person or object. Examples include the loss of a body part, death of a family member, or loss of a job. Lost valued objects include those that wear out or are misplaced, stolen, or ruined by disaster. A child grieves the loss of a favorite toy washed away in a flood. A perceived loss is uniquely defined by the person experiencing the loss and is less obvious to other people. For example, some people perceive rejection by a friend to be a loss, which creates a loss of confidence or changes their status in a group. How an individual interprets the meaning of the perceived loss affects the intensity of the grief response. Perceived losses are easy to overlook because they are experienced so internally and individually, but they are grieved in the same way as an actual loss.

Each person responds to loss differently. The type of loss and the person’s perception of it influence the depth and duration of the grief response. For some individuals the loss of an object (e.g., home or treasured inherited gift) generates the same level of distress as the loss of a person, depending on the value the person places on the object. Chronic illnesses, disabilities, and hospitalization produce multiple losses. When entering an institution for care, patients lose access to familiar people and environments, privacy, and control over body functions and daily routines. A chronic illness or disability adds financial hardships for most people and often brings about changes in lifestyle and dependence on others. Even brief illnesses or hospitalizations cause temporary changes in family role functioning, daily activities, and relationships.

Death is the ultimate loss. Although it is a necessary part of the continuum of life and of being human, death represents the unknown and generates anxiety, fear, and uncertainty for many people. Death permanently separates people physically from important persons in their lives and causes fear, sadness, and regret for the dying person, family members, friends, and caregivers. A person’s culture, spirituality, personal beliefs and values, previous experiences with death, and degree of social support influence the way he or she approaches death.

Grief

Grief is the emotional response to a loss, manifested in ways unique to an individual and based on personal experiences, cultural expectations, and spiritual beliefs (Walter and McCoyd, 2009) (see Chapters 9 and 35). Coping with grief involves a period of mourning, the outward, social expressions of grief and the behavior associated with loss. Most mourning rituals are culturally influenced, learned behaviors. For example, the Jewish mourning ritual of Shivah incorporates the helping behaviors of the community toward those experiencing death, sets expectations for survivor behavior, and sustains the community with tradition and rituals (Bauer-Wu et al., 2007). The term bereavement encompasses both grief and mourning and includes the emotional responses and outward behaviors of a person experiencing loss (AACN, 2008). Recognizing that there are different types of grief can help nurses plan and implement appropriate care.

Normal Grief

Normal (uncomplicated) grief is a common, universal reaction characterized by complex emotional, cognitive, social, physical, behavioral, and spiritual responses to loss and death. Feelings of acceptance, disbelief, yearning, anger, and depression are displayed in normal bereavement grief. Although manner of death (violent, unexpected, or traumatic) poses greater risk to survivors, it does not always determine how an individual will grieve. Helpful coping mechanisms for grieving people include hardiness and resilience, a personal sense of control, and the ability to make sense of and identify positive possibilities after a loss.

Anticipatory Grief

A person experiences anticipatory grief, the unconscious process of disengaging or “letting go” before the actual loss or death occurs, especially in situations of prolonged or predicted loss (Simon, 2008). When grief extends over a long period of time, people absorb loss gradually and begin to prepare for its inevitability. They experience intense responses to grief (e.g., shock, denial, and tearfulness) before the actual death occurs and often feel relief when it finally happens. The idea that people actually grieve in anticipation (rather than following a loss) is debated by researchers. Another way to think about anticipatory grief is that it is a forewarning or cushion that gives people time to prepare or complete the tasks related to the impending death. However, this idea may not apply in every situation. Although forewarning is a buffer for some individuals, it increases stress for others, creating an emotional roller coaster of highs and lows.

Disenfranchised Grief

People experience disenfranchised grief, also known as marginal or unsupported grief, when their relationship to the deceased person is not socially sanctioned, cannot be openly shared, or seems of lesser significance. The person’s loss and grief do not meet the norms of grief acknowledged by his or her culture, cutting the grieving person off from social support and the sympathy given to persons with “legitimate” losses. The grieving person often wonders if he or she should call the experience a loss. Examples include the death an ex-spouse, a gay partner, or a pet or death from a stigmatized illness such as alcoholism or during the commission of a crime (Hooyman and Kramer, 2008; Walter and McCoyd, 2009).

Ambiguous Loss: Sometimes people experience losses that are marked by uncertainty. Ambiguous loss, a type of disenfranchised grief, occurs when the lost person is physically present but not psychologically available, as in cases of severe dementia or severe brain injury. Other times the person is gone (e.g., after a kidnapping or as a prisoner of war); but the grieving person maintains an ongoing, intense psychological attachment, never sure of the reality of the situation. Ambiguous losses are particularly difficult to process because of the lack of finality and unknown outcomes (Walter and McCoyd, 2009).

Complicated Grief

Some people do not experience a normal grief process. In complicated grief a person has a prolonged or significantly difficult time moving forward after a loss. He or she experiences a chronic and disruptive yearning for the deceased; has trouble accepting the death and trusting others; and/or feels excessively bitter, emotionally numb, or anxious about the future. Complicated grief occurs more often when a person had a conflicted relationship with the deceased, prior or multiple losses or stressors, mental health issues, or lack of social support. Loss associated with homicide, suicide, sudden accidents, or the death of a child has the potential to become complicated. Specific types of complicated grief include exaggerated, delayed, and masked grief.

Exaggerated Grief: A person with an exaggerated grief response often exhibits self-destructive or maladaptive behavior, obsessions, or psychiatric disorders. Suicide is a risk for these people.

Delayed Grief: A person’s grief response is unusually delayed or postponed, often because the loss is so overwhelming that the person must avoid the full realization of the loss. A delayed grief response is frequently triggered by a second loss, sometimes seemingly not as significant as the first loss.

Masked Grief: Sometimes a grieving person behaves in ways that interfere with normal functioning but is unaware that the disruptive behavior is a result of the loss and ineffective grief resolution (AACN, 2008).

Theories of Grief and Mourning

Knowledge of grief theories and normal responses to loss and bereavement will help you better understand these complex experiences and how to help a grieving person. Grief theorists describe the physical, psychological, and social reactions to loss. Remember that people who vary from expected norms of grief or theoretical descriptions are not abnormal. The variety of theories supports the complexity and individuality of grief responses. Although most grief theories describe how people cope with death, they also help to understand responses to other significant losses. A review of some classic grief theories follows.

Stages of Dying

Basing her research on interviews with dying people, Kübler-Ross (1969) describes five stages of dying in her classic behavioral theory: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. A person in the denial stage cannot accept the fact of the loss, which often provides psychological protection from a loss that the person cannot yet bear. When experiencing the anger stage of adjustment to loss, a person expresses resistance and sometimes feels intense anger at God, other people, or the situation. Bargaining cushions and postpones awareness of the loss by trying to prevent it from happening. Grieving or dying people make promises to self, God, or loved ones that they will live or believe differently if they can be spared death. When a person realizes the full impact of the loss, depression occurs. Some individuals feel overwhelmingly sad, hopeless, and lonely. In acceptance the person incorporates the loss into life; develops the capacity to have a breadth of emotions, even positive ones; and finds ways to move forward. The stages of dying are not linear. Patients will move back and forth through the stages.

Attachment Theory

Bowlby’s (1980) attachment theory, also a stage theory, describes the experience of mourning based on his studies of children separated from their parents during World War II. Attachment, an instinctive behavior, leads to the development of bonds between children and their primary caregivers. Relational bonds are present and active throughout the life cycle, and individuals later generalize them to persons in other relationships. Attachment behavior ensures survival because it keeps people close to those who offer love, protection, and support.

Bowlby describes four stages of mourning: numbing, yearning and searching, disorganization and despair, and reorganization. Numbing, the shortest stage of mourning, may last from a few hours to a week or more. The grieving person describes this stage as feeling “stunned” or “unreal.” Numbing protects the person from the full impact of the loss. Emotional outbursts of tearful sobbing and acute distress characterize the second bereavement stage, yearning and searching (separation anxiety). Common physical symptoms in this stage include tightness in the chest and throat, shortness of breath, a feeling of lethargy, insomnia, and loss of appetite. A person also experiences an inner, intense yearning for the lost person or object. This stage lasts for months or considerably longer. During the stage of disorganization and despair, a person endlessly examines how and why the loss occurred or expresses anger at anyone who seems responsible for the loss. The grieving person retells the loss story again and again and gradually realizes that the loss is permanent. With reorganization, which usually takes a year or more, the person begins to accept change, assume unfamiliar roles, acquire new skills, and build new relationships. Persons who are reorganizing begin to separate themselves from their lost relationship without feeling that they are lessening its importance.

Grief Tasks Model

Worden (1982) proposes a task-based grief theory. He describes how individuals actively engage in behaviors by responding to outside interventions to help themselves. Working through the grief tasks typically requires a minimum of a full year, although the time varies from person to person.

• Task I: Accept the reality of the loss. Even when a death is expected, survivors register some disbelief and surprise that it has really happened. Task I involves the process of accepting that the person or object is gone and will not return.

• Task II: Experience the pain of grief. Even though people respond to loss differently, it is impossible to experience a significant loss without some emotional pain. People react with sadness, loneliness, despair, or regret and work through painful feelings using the coping mechanisms most familiar and comfortable to them.

• Task III: Adjust to a world in which the deceased is missing. A person does not realize the full impact of a loss for at least 3 months. Family members or friends pay less attention to the bereaved person at about the same time, just as the finality of the loss becomes real. People completing this task begin to take on roles formerly filled by the deceased, including some jobs they do not want.

• Task IV: Emotionally relocate the deceased and move on with life. The deceased person is not forgotten but rather takes a different and less prominent place in the survivor’s emotional life. People often fear that in making new attachments they will forget their loved one or seem disloyal, making this a potentially difficult task to complete. Realizing that it is possible to love other people without betraying the deceased, the person moves forward.

Rando’s “R” Process Model

Rando (1993) describes grief as a series of processes instead of stages or tasks. However, her processes are similar to the stages and tasks already described. Rando’s processes include recognizing the loss, reacting to the pain of separation, reminiscing, relinquishing old attachments, and readjusting to life after loss. Reminiscence is an important activity in grief and mourning. A person recollects and reexperiences the deceased and the relationship by mentally or verbally anecdotally reliving and remembering the person and past experiences.

Dual Process Model

Newer theories account for gender and cultural variations and address the limitations of theories focused mainly on internal, emotional responses to grief. The dual process model describes the everyday life experiences of grief as moving back and forth between loss-oriented and restoration-oriented activities (Wright and Hogan, 2008). Loss-oriented behaviors include grief work, dwelling on the loss, breaking connections with the deceased person, and resisting activities to move past the grief. Restoration-oriented activities such as attending to life changes, finding new roles or relationships, coping with finances, and participating in distractions provide balance to the loss-oriented state. The extent to which an individual engages in loss or restoration-oriented processes depends on factors such as personality, coping styles, or cultural practices.

Post Modern Grief Theories

Some experts believe the stage and task theories described previously lack empirical evidence, do not allow for cultural differences, and assume there is an end point in grieving (Walter and McCoyd, 2009). More recent grief theories take into consideration that human beings construct their own experiences and truths differently and make their own meanings when confronted with loss and death. Differences in social and historical context, family structure, and cognitive capacities shape an individual’s truths and grief experiences. No one’s grief follows a predetermined path.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Nurses develop plans of care to help patients and family members who are undergoing loss, grief, or death experiences. Based on nursing research, practice evidence, nursing experience, and patient and family preferences, nurses implement plans of care in acute care, nursing home, hospice, home care, and community settings. Extensive nursing education programs support the improvement of end-of-life care at every level of practice. The End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) provides nurses with basic and advanced curricula to care for patients and families experiencing loss, grief, death, and bereavement (AACN, 2008); and nursing textbooks provide advanced discussions on multiple dimensions of palliative and end-of-life care (Ferrell and Coyle, 2010; Matzo and Sherman, 2010). In conjunction with the Hospice and Palliative Care Nurses Association, the American Nurses Association has developed the Scope and Standards of Hospice and Palliative Nursing Practice (2007). Professional nursing organizations such as the American Society of Pain Management Nurses and the American Association of Critical Care Nurses offer evidence-based practice guidelines for managing clinical and ethical issues at the end of life in many health care settings.

Factors Influencing Loss and Grief

Multiple factors influence the way a person perceives and responds to loss. They include developmental factors, personal relationships, the nature of the loss, coping strategies, socioeconomic status, and cultural and spiritual influences and beliefs.

Human Development

Patient age and stage of development affect the grief response. For example, toddlers cannot understand loss or death but often feel anxiety over the loss of objects and separation from parents. They sometimes express the sense of absence they feel with changes in eating and sleeping patterns, fussiness, or bowel and bladder disturbances. School-age children understand the concepts of permanence and irreversibility but do not always understand the causes of a loss. Some have intense periods of emotional expression. Young adults undergo many necessary developmental losses related to their evolving future. They leave home, begin school or a work life, or form significant relationships. Illness or death disrupts the young adult’s future and establishment of an autonomous sense of self. Midlife adults also experience major life transitions such as caring for aging parents, dealing with changes in marital status, and adapting to new family roles (Walter and McCoyd, 2009). For older adults the aging process leads to necessary and developmental losses. Some older adults experience age discrimination, especially when they become dependent or are near death; but they show resilience after a loss as a result of their prior experiences and developed coping skills (Box 36-1).

Personal Relationships

When loss involves another person, the quality and meaning of the lost relationship influence the grief response. When a relationship between two people was very rewarding and well connected, the survivor often finds it difficult to move forward. Grief resolution is hampered by regret and a sense of unfinished business, especially when people are closely related but did not have a good relationship at the time of death. Social support and the ability to accept help from others are critical variables in recovery from loss and grief. When patients do not receive supportive understanding and compassion from others, grief becomes complicated or prolonged (Hooyman and Kramer, 2008).

Nature of the Loss

Exploring the meaning a loss has for your patient helps you better understand the effect of the loss on the patient’s behavior, health, and well-being. Highly visible losses generally stimulate a helping response from others. For example, the loss of one’s home from a tornado often brings community and governmental support. A more private loss such as a miscarriage brings less support from others. A sudden and unexpected death poses different challenges than those in a debilitating chronic illness. When the death is sudden and unexpected, the survivors do not have time to let go. In chronic illness survivors have memories of prolonged suffering, pain, and loss of function. Death by violence or suicide or multiple losses by their very nature complicate the grieving process in unique ways (Walter and McCoyd, 2009).

Coping Strategies

Life experiences shape the coping strategies that a person uses to deal with the stress of loss. Patients rely first on familiar coping strategies. When the usual coping strategies do not work, they need new ones. Emotional disclosure (i.e., venting, talking about one’s feelings, or expressing anger or other negative feelings) is one way to cope with loss. Negative themes that are present when people talk about grief sometimes predict more distressful reactions (Maciejewski, 2007). However, some individuals cope better in situations of loss when they instead focus on positive emotions and optimistic feelings. Emotional disclosure is often accomplished by having people write about their feelings in letters to lost loved ones or personal journals.

Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic status influences a person’s ability to access support and resources for coping with loss and physical responses to stress (Cohen et al., 2006). When people lack financial, educational, or occupational resources, the burdens of loss multiply. For example, a patient with limited finances is not able to replace a car demolished in an accident and pay for the associated medical expenses.

Culture and Ethnicity

Culture and family or religious affiliation influences interpretations of loss and the ability to establish acceptable expressions of grief, which affects the ability to provide stability and structure in the midst of chaos and loss. Expressions of grief in one culture do not always make sense to people from a different culture (see Chapter 9). Try to understand and appreciate each patient’s cultural values related to loss, death, and grieving. Grief theories commonly used to understand loss and death have cultural limitations. For example, some theorists describe grief as a process of “work” or “tasks” that occurs in stages or on projected timelines. North Americans may better understand work, tasks, and time expectations for grief compared to other cultural groups not as defined by work achievements or with a different sense of time. Some cultural groups experience grief as a timeless, communal expression or state of being. Many people in Western European and American cultures hold back their public displays of emotion. In other cultures behaviors such as public wailing and physical demonstrations of grief, including survivor body mutilation, show respect for the dead. Core American cultural values of individualism and self-determination stand in contrast with communal, family, or tribal ways of life. Americans value and expect honesty and truth telling in end-of-life situations, but some cultures have strict taboos surrounding what should be discussed regarding the diagnosis and prognosis in serious illness (Erichsen et al., 2010; Johnstone and Kanitsaki, 2009). Cultural differences influence processes such as obtaining informed consent or making life-support decisions. Research has shown that ethnicity is strongly related to attitudes toward life-sustaining treatments during terminal illness and the use of hospice services (Rosenfeld et al., 2007).

Spiritual and Religious Beliefs

The care of seriously ill patients usually involves medical interventions to restore or maintain health. A contrasting set of practices (i.e., transformative strategies) acknowledge life limits and help dying people find meaning in suffering so they are able to transcend (go beyond) their personal existence. Transformative practices are associated with healing and spiritual or religious beliefs. Spiritual resources include faith in a higher power, communities of support, friends, a sense of hope and meaning in life, and religious practices. Spirituality affects the patient’s and family members’ ability to cope with loss. Positive correlations show that spiritual well-being, peacefulness, comfort, and serenity are all important aspects of a peaceful death (Kruse et al., 2007). Findings in the literature verify that religious beliefs provide a sense of structure in end-of-life situations and are linked to more positive attitudes toward death (Ladd, 2007).

Hope, a multidimensional concept considered to be a component of spirituality, energizes and provides comfort to individuals experiencing personal challenges. Hopefulness gives a person the ability to see life as enduring or having meaning or purpose. As a future-shaping, motivating force, hope helps patients maintain anticipation of a continued good, an improvement in their circumstances, or a lessening of something unpleasant (Clayton et al., 2008). With hope a patient moves from feelings of weakness and vulnerability to living as fully as possible. Maintaining a sense of hope depends in part on a person having strong relationships and emotional connectedness to others. On the other hand, spiritual distress often arises from a patient’s inability to feel hopeful or foresee any favorable outcomes. Spirituality and hope play a vital role in a patient’s adjustment to loss and death (see Chapter 35).

Critical Thinking

To provide appropriate and responsive care for the grieving patient and family, use critical thinking skills to synthesize scientific knowledge from nursing and nonnursing disciplines, professional standards, evidence-based practice, patient assessments, previous caregiving experiences, and self-knowledge. Critical thinking informs all steps of the nursing process (see Chapter 15).

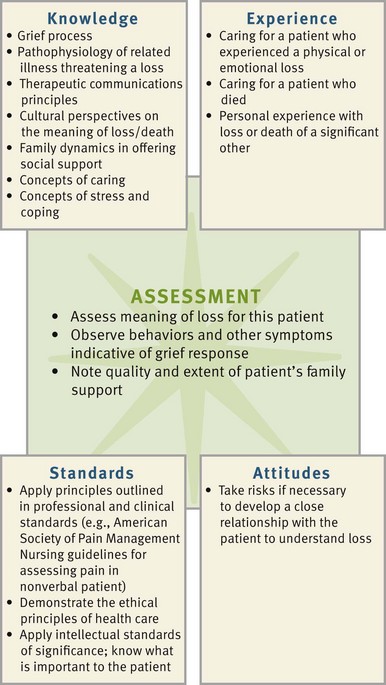

During the assessment phase use critical thinking to gather and analyze the data that lead to the selection of appropriate nursing diagnoses (Fig. 36-1). To understand a patient’s subjective experiences of loss, form assessment questions based on your theoretical and professional knowledge of grief and loss but then listen carefully to the patient’s perceptions. A culturally competent nurse also uses culture-specific understanding of grief to explore the meaning of loss with a patient.

Being familiar with commonly experienced responses to loss enables you to better understand a patient’s emotions and behaviors. Some patients ignore, lash out, plead with, or withdraw from other people as part of a normal response to loss. Instead of “taking things personally,” a critically thinking nurse integrates theory, prior experience, appreciation of subjective experiences, and self-knowledge to respond to the patient’s emotions with patience and understanding. In designing plans of care, use professional standards, including the Nursing Code of Ethics (see Chapter 22), the dying person’s bill of rights (Box 36-2), the American Nurses Association Scope and Standards of Hospice and Palliative Nursing Practice (2007), and clinical standards such as the American Society of Pain Management Nurses’ guidelines for pain assessment in the nonverbal patient (Herr et al., 2006).

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care.

Assessment

During the assessment process, thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care. A trusting, helping relationship with grieving patients and family members is essential to the assessment process. A caring nurse encourages a patient to tell his or her story, which then becomes a primary source of assessment data (Betcher, 2010). Look for opportunities to invite patients to share their experiences, being aware that attitudes about self-disclosure; sharing emotions; or talking about illness, fears, and death are shaped by an individual’s personality, coping style, and culture.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

Explore with patients their unique responses to grief or their preferences for end-of-life care, which may include advance directives. Patient perceptions and expectations influence how you prioritize your nursing diagnoses. To assess patient perceptions, you ask, “What is the most important thing I can do for you right now?” You usually gather information from patients first, but with advanced illness and as death approaches, patients often rely on family members to communicate for them. Encourage family members to share their goals and perceptions with you. Whether or not they accurately represent a patient’s viewpoints or wishes has been the topic of extensive research (Gardner and Kramer, 2010). Most often they provide valuable information about patient preferences and clarify misunderstandings or identify overlooked information. Assess patients’ and family members’ understanding of treatment options to implement a mutually developed care plan. Assessment of grief responses extends throughout the course of an illness into the bereavement period following a death. Patients with advanced chronic illness and their families eventually face end-of-life care decisions and should discuss the content of any advance directives together. Because most deaths are now “negotiated” among patients, family members, and the health care team, discuss end-of-life care preferences early in the assessment phase of the nursing process. If you feel uncomfortable in assessing a patient’s wishes for end-of-life care by yourself, ask a health care provider experienced in discussing these issues to help you. Communicate what you have learned about patient preferences during any RN hand-off, at health care team conferences, in written care plans, and through ongoing consultation (see Chapter 26).

Speak to patients and family members using honest and open communication, remembering that cultural practices influence how much information the patient shares. Keep an open mind, listen carefully, and observe the patient’s verbal and nonverbal responses. Facial expressions, voice tones, and avoided topics often disclose more than words. Anticipate common grief responses, but allow patients to describe their experiences in their own words. Open-ended questions such as “What do you understand about your diagnosis?” or “You seem sad today. Can you tell me more?” may open the door to a patient-centered discussion. Many people find it difficult to talk about loss, fear, death, or grief. The use of pauses, gentle questioning, and silence honors the patient’s privacy and readiness to talk. Talk to patients and family members in a private, quiet setting. Many times a patient wants to have family members present so everyone hears the same thing and has an opportunity to add to the conversation. However, some people want their concerns and questions addressed privately. Ask patients and family members about their preferences. As you gather assessment data, summarize and validate your impressions with the patient or family member. Information from the medical record and other members of the health care team, physicians, social workers, and spiritual care providers contributes to your assessment data.

Because of the importance of symptom management and priority of comfort in end-of-life care, prioritize your initial assessment to encourage patients to identify any distressing symptoms. Completing a thorough assessment is difficult when patients are in pain, anxious, depressed, or short of breath.

Grief Variables

Conversations about the meaning of loss to a patient often leads to other important areas of assessment, including the patient’s coping style, the nature of family relationships, social support systems, the nature of the loss, cultural and spiritual beliefs, life goals, family grief patterns, self-care, and sources of hope (Box 36-3). Use skills appropriate for assessing a patient’s culture, family, self-concept, or spiritual beliefs (see Chapters 9, 10, 33, and 35) to acquire a deeper understanding of his or her loss.

Knowing the commonly experienced reactions to grief and loss and grief theories guides your critical thinking and assessment skills. A single behavior can occur in all types of grief. If a grieving patient describes loneliness and difficulty falling asleep, consider all factors surrounding the loss in context. What was the loss? When did it occur? What was the meaning of the loss to the patient? For example, when your patient exhibits signs of a normal grief reaction, but you learn that the loss occurred 2 years ago, the patient’s response most likely indicates a complicated, chronic grief experience. Focus your assessment on how a patient is reacting to loss or grief and not on how you believe that patient should be reacting.

Grief Reactions

Use psychological and physical assessment skills to assess a patient’s unique grief responses. Most grieving people show some common outward signs and symptoms (Box 36-4). Analyze assessment data and identify possible related causes for the signs and symptoms that you observe. For example, after a significant loss a person has a sad affect, withdrawn behaviors, headaches, upset stomach, and decreased ability to concentrate. You associate these symptoms with several potential causes, including anxiety, gastrointestinal disturbances, medication side effects, or impaired memory. Careful analysis of the symptoms in context leads you to an accurate nursing diagnosis. Ask: How are the symptoms related to one another when they occur? When did they begin? Were they present before the loss? To what does the person attribute them?

Loss takes place in a social context; thus family assessment is a vital part of your data gathering. If a father of a young family is dying, he will not be able to fulfill certain roles, causing a change in family structure. When a person develops a disability, the patient and family members realign their roles and responsibilities to meet new demands. Family members also experience a variety of physical and psychological symptoms. Assess the family’s response to loss and recognize that sometimes they are dealing with their grief at a different pace.

Nursing Diagnosis

Use critical thinking to cluster assessment data cues, identify defining characteristics, draw conclusions regarding the patient’s actual or potential needs or resources, and identify nursing diagnoses applicable to the patient’s situation (Box 36-5). In addition to numerous diagnoses related to physical symptoms at the end of life, additional nursing diagnoses relevant for patients experiencing grief, loss, or death include:

You cannot make accurate nursing diagnoses on the basis of just one or two defining characteristics. Carefully review the data to consider if more than one diagnosis applies. For example, a dying patient who cries often, has angry outbursts, and reports nightmares gives evidence of several possible nursing diagnoses: pain (acute or chronic), ineffective coping, grieving, or spiritual distress. Examine the available data, validate assumptions with the patient, and look for other validating behaviors and symptoms before making a diagnosis.

As part of the diagnostic process, identify the appropriate “related to” factor for each diagnosis. Clarification of the related factors ensures that you select appropriate interventions. For example, a nursing diagnosis of complicated grieving related to the permanent loss of mobility requires different interventions than a diagnosis of complicated grieving related to infertility after an ectopic pregnancy.

When identifying nursing diagnoses related to a patient’s grief or loss, you sometimes identify other related diagnoses. Some patients experiencing grief or impending death have nursing diagnoses such as disturbed body image or impaired physical mobility. A patient entering the phase of active dying often has diagnoses related to physical changes, including impaired urinary elimination, bowel incontinence, acute pain, nausea, disturbed sensory perception, and ineffective breathing pattern.

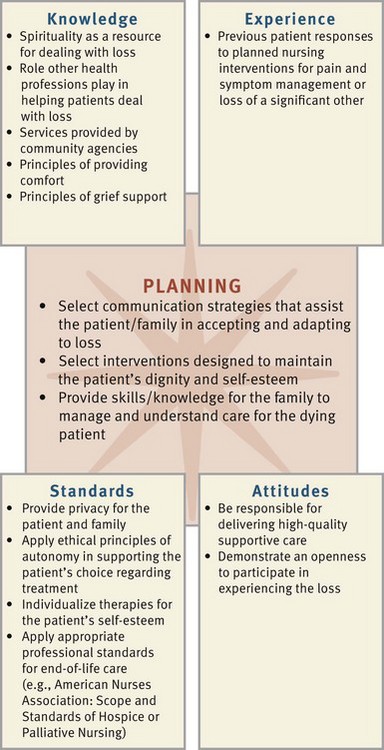

Planning

Nurses provide holistic, physical, emotional, social, and spiritual care to patients experiencing grief, death, or loss. Fig. 36-2 illustrates the interrelatedness of critical thinking factors during the planning phase of the nursing process. The use of critical thinking ensures a well-designed care plan that supports a patient’s self-esteem and autonomy by including him or her in the planning process. A care plan for the dying patient focuses on comfort; preserving dignity and quality of life; and providing family members with emotional, social, and spiritual support (see the Nursing Care Plan).

Goals and Outcomes

During planning establish realistic goals and expected outcomes based on the nursing diagnoses. Consider a patient’s own resources such as physical energy and activity tolerance, family support, and coping style. A nursing diagnosis of powerlessness related to experimental cancer therapy with a goal of “Patient will be able to describe the expected course of disease” is realistic for a patient who frequently asks for clarification about the treatment plan and participates in educational discussions. In contrast, an expected outcome of “Patient will identify a minimum of three effective coping skills” is appropriate for a patient with the same nursing diagnosis who is experiencing depression from feeling powerless about having experimental cancer treatment.

The goals of care for a patient experiencing loss are either short or long term, depending on the nature of the loss and the patient’s condition. Some nursing care goals for patients facing loss or death include accommodating grief, accepting the reality of a loss, or maintaining meaningful relationships. A possible goal for a young woman with advanced breast cancer is “Maintain a sense of control,” with the following potential expected outcomes:

Setting Priorities

Encourage patients and family members to share their priorities for care at the end of life. Patients at the end of life or with advanced chronic illness are more likely to want their comfort, social, or spiritual needs met rather than pursuing medical cures. Give priority to a patient’s most urgent physical or psychological needs while also considering his or her expectations and priorities. If a terminally ill patient’s goals include pain control and promoting self-esteem, pain control takes priority when the patient experiences acute physical discomfort. When comfort needs have been met, then you address other issues important to the patient and family. When it is realistic for the patient to remain independent, strategies that foster his or her sense of autonomy and ability to function independently take priority. A patient’s condition at the end of life often changes quickly; therefore maintain an ongoing assessment to revise the plan of care according to patient needs and preferences.

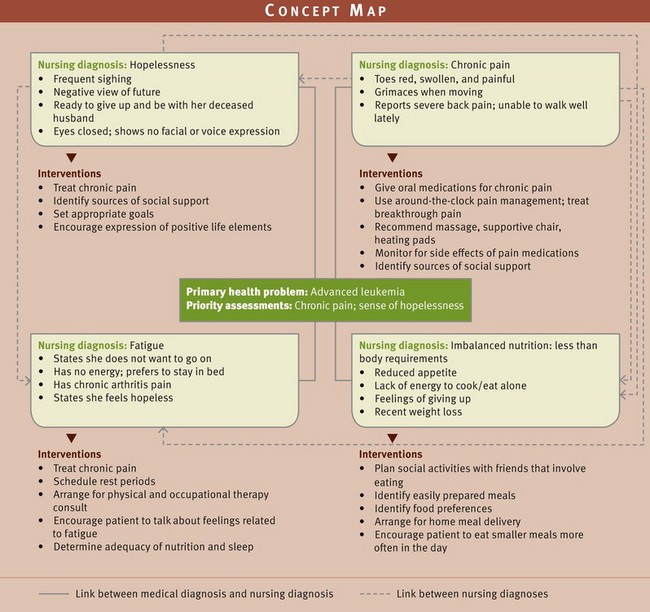

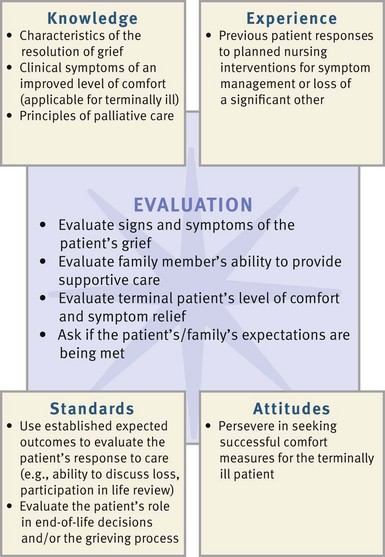

When a patient has multiple nursing diagnoses, it is not possible to address them all simultaneously. Fig. 36-3 illustrates a concept map developed for Mrs. Allison, an elderly patient with a medical diagnosis of advanced cancer (leukemia). In conjunction with her recent medical diagnosis, she experiences associated health problems identified in the nursing diagnoses chronic pain, imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements, fatigue, and hopelessness. In such a situation determine which of the four diagnoses should take priority. The chronic pain experienced by the patient is often the first focus. Until the patient’s pain is under control, it will not be possible for her to feel more energized, eat well, or regain her sense of hopefulness.

Teamwork and Collaboration

As described previously, grief, loss, and death affect people physically, emotionally, spiritually, and culturally. No one is able to address all of these dimensions alone. A team of nurses, physicians, social workers, spiritual care providers, nutritionists, pharmacists, physical and occupational therapists, patients, and family members works together to provide palliative care, grief care, and care at the end of life. Massage or music/art therapists who provide alternative therapies are sometimes part of the team (see Chapter 32). As a patient’s care needs change, team members take a more or less active role, depending on the patient’s shifting priorities. Team members communicate with one another on a regular basis to ensure coordination and effectiveness of care.

Implementation

Health promotion in serious chronic illness or death focuses on facilitating successful coping and optimizing physical, emotional, and spiritual health. Many people continue to look for and find meaning even in difficult life circumstances. They often find personal growth and spiritual insights they have not previously experienced and need family and nurse support as they strive to maintain a degree of normalcy; live with loss; make health care decisions; prepare for death; and adjust to disappointments, frustration, and anxieties along the way (Box 36-6).

Palliative Care in Acute and Restorative Settings: Interventions for people who face chronic life-threatening illnesses or who are at the end of life need palliative care. Palliative care focuses on the prevention, relief, reduction, or soothing of symptoms of disease or disorders throughout the entire course of an illness, including care of the dying and bereavement follow-up for the family. The primary goal of palliative care is to help patients and families achieve the best possible quality of life. Although it is especially important in advanced or chronic illness, it is appropriate for patients of any age, with any diagnosis, at any time, or in any setting.

Patients who have complex serious illnesses often benefit from palliative care throughout the course of their illness, even while seeking treatment for their disease. As the goals of care change and cure for illnesses becomes less likely, the focus shifts to more palliative care strategies. Palliative care interventions are not only appropriate at the end of life. Making this distinction is important because some patients, family members, or health care professionals refuse helpful palliative care interventions, believing that palliative care is only for the dying.

Hospice Care: Hospice care is a philosophy and a model for the care of terminally ill patients and their families. Hospice is not a place but rather a patient- and family-centered approach to care. It gives priority to managing a patient’s pain and other symptoms; comfort; quality of life; and attention to physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs and resources. Patients accepted into a hospice program usually have less than 6 to 12 months to live. Hospice services are available in home, hospital, extended care, or nursing home settings.

Many patients prefer to die at home in a familiar setting, whereas others fear burdening their families or prefer to die in a hospital or nursing home. It is important that the hospice team knows the patient’s preference. When family issues complicate the options, hospice caregivers try to support the patient’s wishes but also consider what is best for everyone. Sometimes the complexity and severity of patients’ symptoms prevent them from being cared for at home, despite the willingness of family and friends to provide care. Patients receiving hospice care are active participants in all aspects of care, and caregivers prioritize care according to patient wishes. Patient care goals are mutually set, and all participants fully understand the patient’s care preferences and try to honor them. Hospice services provide bereavement visits made by the staff after the death of the patient to help the family move through the grieving process.

To be eligible for home hospice services, a patient must have a family caregiver to provide care when the patient is no longer able to function alone. Home care aides offer help with hygienic needs, and a nurse is available to coordinate and manage symptom relief. Nurses providing hospice care use therapeutic communication, offer psychosocial care and expert symptom management, promote patient dignity and self-esteem, maintain a comfortable and peaceful environment, provide spiritual comfort and hope, protect against abandonment or isolation, offer family support, assist with ethical decision making, and facilitate mourning. Hospice team members offer 24-hour accessibility and coordinate care between the home and inpatient setting. A patient receiving home hospice care may enter the hospital for stabilization of symptoms or for caregiver respite. As a patient’s death comes closer, the hospice team provides intensive support to the patient and family (Hospice Foundation of America, 2010).

Use Therapeutic Communication: Establish a caring, trusting relationship with a patient and family by using an “open hearted,” nonassuming communication style (Galvin and Todres, 2009; Wright et al., 2009). Open-ended questions invite patients to expand on their thoughts and tell their stories. Patients usually give short answers (yes or no) when you use closed-ended questions, which limits what you can learn about a patient’s situation. Use active listening, learn to be comfortable with silence, and use prompts (e.g., “go on,” “tell me more”) to encourage continued conversation (Fig. 36-4). Empathize with the patient’s grief; offer your caring, transformative presence and use intentional, meaningful touch (Newman, 2008).

Feelings of sadness, numbing, denial, or anger make talking about these situations especially difficult. For example, a grieving patient experiences anger and becomes hostile with family members or caregivers. Some patients become demanding and accusing. Remain supportive by letting patients and family members know that feelings such as anger are normal by saying, “You are understandably upset right now. I just want you to know I’m here to talk with you if you want.” Invite patients to reveal the emotions and concerns of greatest importance to them and acknowledge their feelings and concerns in a nonjudgmental manner. If a patient chooses not to share feelings or concerns, express a willingness to be available at any time. Some patients do not discuss emotions for personal or cultural reasons, and other patients hesitate to express their emotions for fear that others will abandon them. If you are reassuring and respectful of a patient’s privacy, a therapeutic relationship likely develops. Sometimes patients need to begin resolving their grief privately before they discuss their loss with others, especially strangers.

Avoid communication barriers such as denying a patient’s grief, providing false reassurance, or avoiding discussion of sensitive issues (see Chapter 24). When you sense that a patient wants to talk about something, make time immediately if at all possible. This is very challenging if you have limited experience with dying patients or are in a busy acute care setting. Above all, remember that a patient’s emotions are not something you can “fix.” Instead view emotional expression as a necessary part of the patient’s adjustment to significant life changes and development of effective coping skills. Help family members access other professional resources. For example, call on a spiritual care provider to help patients and family members discuss difficult issues related to personal meanings, faith beliefs, and values.

Provide Psychosocial Care: Patients at the end of life experience a range of psychological symptoms, including anxiety, depression, altered body image, denial, powerlessness, uncertainty, and isolation (Taylor and Ashelford, 2008). Patients experience anguish from not knowing or being unaware of aspects of their health status or treatment. Worry or fear is common in many patients and often heightens their perception of discomfort and suffering. Providing information helps patients understand their condition, the course of their disease, and the benefits and burdens of treatment options. Suffering, a complex social and psychological response to illness, loss, and death, goes beyond psychological diagnoses. Nurses validate and support those who suffer (Ferrell and Coyle, 2008).

Manage Symptoms: Managing the multiple symptoms commonly experienced by chronically ill or dying patients remains a primary goal of palliative care nursing. Symptom distress, discomfort, and anguish often complicate a patient’s dying experience. Despite the availability of effective treatment options for pain, many patients suffer with avoidable pain at the end of life. Maintain an ongoing assessment by reassessing pain and medication side effects, using pain management expertise, and advocating for change if the patient does not obtain relief from the prescribed regimen. Implement evidence-based pain management protocols (Paice, 2010) (see Chapter 43). It is essential for you to learn how to assess patients who are debilitated or dying because they often lose their ability to communicate or self-advocate (Herr et al., 2006). During the dying process, patients’ renal and liver function decline, decreasing metabolism and rate of drug clearance and leading to a need for decreased medication dosages to avoid toxicities. Also be aware that advancing disease pathology, anxiety, or delirium sometimes requires the use of higher doses or different drug therapies.

Remain alert to the potential side effects of opioid administration: constipation, nausea, sedation, respiratory depression, or myoclonus. Family members often worry about potential addiction to opioid medications. Not only is the incidence of true addiction very low, but a patient’s need for pain relief at the end of life takes priority. Table 36-2 provides a basic overview of nursing care for common symptoms experienced at the end of life.

TABLE 36-2

Promoting Comfort in the Terminally Ill Patient

| SYMPTOMS | CHARACTERISTICS OR CAUSES | NURSING IMPLICATIONS |

| Pain | Multiple causes, depending on patient diagnosis. | See Chapter 43 for a full discussion of pain management. |

| Skin and mucous membrane discomfort | Any source of skin irritation increases discomfort. | Provide skin care as needed based on patient comfort or preference. Apply lotion to skin; dry, clean bed linens to reduce irritants (see Chapter 39). |

| Mucous membrane discomfort | Mouth breathing or dehydration leads to dry mucous membranes; tongue and lips become dry or chapped. | Provide oral care, including tongue, every 2 to 4 hours with soft toothbrushes or foam swabs and using nonabrasive toothpaste or water. Apply a light film of lip balm for dryness. Apply topical analgesics to oral lesions (see Chapter 39). |

| Corneal irritation | Blinking reflexes diminish near death, causing drying of cornea. | Optical lubricants or artificial tears reduce corneal drying. Eye care with warm water removes crusts from eyelid margins. |

| Fatigue | Metabolic demands, stress, disease states, decreased oral intake, and heart function cause weakness and fatigue. | Balance activity and rest periods according to patient’s priorities and preferred time of day. Conserve patient energy by modifying environment (Kehl, 2008). |

| Anxiety | Physical, social, or spiritual distress causes anxiety; causes may be situational or event specific. | Address underlying cause; provide calm, supportive environment, active listening; use benzodiazepines for acute anxiety (Pasacreta et al., 2010). |

| Nausea | Medications, pain, or decreased intestinal blood flow with impending death | Administer antiemetics or promotility agents; discontinue medications or foods that cause nausea; provide oral care at least every 2 to 4 hours; offer clear liquid diet and ice chips; avoid liquids that increase stomach acidity (Acreman, 2009). |

| Constipation | Opioids, medications, and immobility slow peristalsis. Lack of bulk in diet or reduced fluid. |

Use a stimulant laxative with opioids. Make dietary alterations as preferred or tolerated; increase fluid intake if tolerated (Enck, 2009). |

| Diarrhea | Disease processes, treatment or medications, and gastrointestinal (GI) infections. | Assess for fecal impaction. Confer with health care provider to change medication if identified as the cause. Protect skin with moisture barrier (Kyle, 2010). |

| Urinary incontinence | Progressive disease and decreased level of consciousness. | Protect skin from irritation or breakdown by maintaining dry linens and clothing. Use indwelling urinary catheter or condom catheters for comfort or prevention of skin problems (Kyle, 2010). |

| Altered nutrition | Medications, depression, decreased activity, and decreased blood flow to the GI tract; nausea produces anorexia. | Offer smaller portions of patient-preferred foods. Treat underlying cause of anorexia if patient still wants to eat. Do not force food on patients (Acreman, 2009). |

| Dehydration | Patient is less willing or able to maintain oral fluid intake; has fever. | Reduce discomfort from dehydration; give mouth care at least every 2 to 4 hours; offer ice chips or moist cloth to lips. Keep lips and tongue moist. |

| Ineffective breathing patterns (e.g., dyspnea, shortness of breath) | Anxiety; fever; pain; increased oxygen demand; disease processes; and anemia, which reduces oxygen-carrying capacity. | Treat or control underlying cause. Position for comfort and maximal respiratory excursion, provide supplemental oxygen if comforting; reduce anxiety or fever; and provide effective pain management. Use fan for air movement, stimulating trigeminal nerve in cheek, which decreases dyspneic sensation. Administer anxiolytics, bronchodilators, inhaled steroids, or opioids to suppress cough and ease breathing and apprehension (Balkstra, 2010). |

| Noisy breathing (“death rattle”) | Noisy breathing is the sound of secretions moving in the airway during inspiratory and expiratory phases caused by thick secretions, decreased muscle tone, swallow, and cough. | Elevate head to facilitate postural drainage. Turn from side to side to mobilize and drain secretions. Stop oral intake; avoid suctioning because of discomfort and ineffectiveness. Anticholinergic medications are sometimes helpful (Hipp and Letizia, 2009). |

Promote Dignity and Self-Esteem: A sense of dignity includes a person’s positive self-regard, an ability to invest in and gain strength from one’s own meaning in life, feeling valued by others, and how one is treated by caregivers. Nurses promote patients’ self-esteem and dignity by respecting them as a whole (i.e., as people with feelings, accomplishments, and passions independent of the illness experience). Giving importance to the things that a patient cares about validates the person, at the same time strengthening communication among the patient, family members, and the nurse. Spending time with patients as they share their life stories helps you know him or her better and facilitates the development of individualized interventions. Show respect for older patients by calling them by surnames and titles and obtaining their permission to include others in private conversations.

Attending to the patient’s physical appearance promotes dignity and self-esteem. Cleanliness, absence of body odors, and attractive clothing give patients a sense of worth. When caring for a patient’s bodily functions, show patience and respect, especially after the patient becomes dependent. Allow patients to make decisions such as how and when to administer personal hygiene, diet preferences, and timing of nursing interventions. Keep the patient and family members informed about daily activities, tests, or therapies; their purposes; and anticipated effects. Provide privacy during nursing care procedures and be sensitive to when the patient and family need time alone together.

Maintain a Comfortable and Peaceful Environment: A comfortable, clean, pleasant environment helps patients relax, promotes good sleep patterns, and minimizes symptom severity. Keep a patient comfortable through frequent repositioning, making sure that bed linens are dry and controlling extraneous environmental noise and offensive odors. Pictures, cherished objects, and cards or letters from family members and friends create a familiar and comforting environment for the patient dying in an institutional setting. Consider nonpharmacological interventions to increase patient comfort (Running et al., 2008). Family members are often able to provide these interventions, increasing their sense that they are making a positive contribution. Research supports the use of soft massage and brief hand massages for reducing stress (Osaka et al., 2009). Use patient-preferred music in the background, provide guided-imagery exercises, and dim the lights to provide a soothing environment for the patient and family. Patient-preferred forms of complementary therapies offer noninvasive methods to increase comfort and well-being at the end of life (Mariano, 2010) (see Chapter 32).

Promote Spiritual Comfort and Hope: Help patients make connections to their spiritual practice or cultural community. Patients are comforted when they have assurance that some aspect of their lives will transcend death. Draw on the resources of spiritual care providers in an institutional setting or collaborate with the patient’s own spiritual or religious leaders and communities. Making an audiotape or videotape for the family, writing letters, or keeping a journal assures patients that something of their essence will survive past their death.

The spiritual concept of hope takes on special significance near the end of life. Nursing strategies that promote hope are often quite simple: be present and provide holistic care that affirms a patient’s life and maintains dignity (Daaleman et al., 2008). Patients perceive the love of family and friends, faith, goal setting, positive relationships with professional caregivers, humor, and uplifting memories as hope promoting. Circumstances that hinder the preservation of hope include abandonment or isolation, uncontrolled symptoms, or being devalued as a person. Patients and their families hope for different things over the course of their experience with illness and death. Some hope to live for an anniversary, sit outdoors for a meal, see an important person one last time, gain pain relief, or have a peaceful death. Listen for shifts in patients’ hopes and find ways to help them meet their desired goals.

Protect Against Abandonment and Isolation: Many patients with terminal illness fear dying alone. Patients feel more hopeful when others are near to help them. Nurses in institutional settings need to answer call lights promptly and check on patients often to reassure them that someone is close at hand. Consider carefully whether or not to place a patient who is actively dying in a private room. If family members plan to stay with the patient at all times or if you have assessed high privacy needs for the patient and family, a private room is best. On the other hand, many patients appreciate being able to stay involved and interact with others, which is possible when sharing a room.

Some family members who have a difficult time accepting a patient’s impending death cope by making fewer visits. When family members do visit, inform them of the patient’s status and share meaningful insights or encounters that you have had with the patient. Find simple and appropriate care activities for the family to perform such as offering food, cooling the patient’s face, combing hair, or filling out a menu. Nighttime can be particularly lonely. Suggest that a family member stay through the night if possible. Make exceptions to visiting policies, allowing family members to remain with patients who are dying at any time. Family members appreciate having open access or closeness to their loved one through their experiences at the end of life. Record contact information for them so you can reach them at any time.

Support the Grieving Family: In palliative care patients and family members constitute the unit of care. When a patient becomes debilitated or approaches the end of life, family members also suffer. They describe caregiving at the end of life as unpredictable, frightening, and anguishing. On the other hand, they report being deeply moved by their experiences and describe their activities as affirming (Phillips, 2009). In these extremely intimate and emotionally challenging times, offer holistic, family-centered support, compassion, and education that incorporates the uniqueness of each patient. Often family members face challenging and complex situations long before their loved one is actively dying. Family members caring for people with serious life-limiting illness need attention and support early and consistently throughout the experience of illness and death (Box 36-7).

Families report that they especially value having access to the information they need to make important decisions (Spichiger, 2008). Educate family members in all settings about the symptoms that the patient will likely experience and the implications for care. For example, patients in the last days of life often develop anorexia or feel nauseated by food. Illness, decreased activity, treatments, and fatigue decrease a patient’s caloric needs and appetite. Family members, distressed with the decline, often believe that they need to encourage the patient to eat. Forcing food or fluids stresses the patient’s compromised gastrointestinal and cardiovascular systems, potentially creating increased discomfort (Acreman, 2009). Help families shift their focus to other helping activities during this time.

Family members who have limited prior experience with death do not know what to expect. They may need personal time with the nurse to share their concerns, ask about treatment options, validate perceived changes in the patient’s status, or explore the possible meaning of patient behaviors. Whenever possible, communicate news of a patient’s declining condition or impending death when family members are together so they can support each other. Provide information privately and stay with the family as long as needed or desired. Reduce family member anxiety, stress, or fear by describing what to expect as death approaches. Become familiar with common manifestations of impending death (Box 36-8), remembering that patients usually experience some but not all of these changes. Do not try to predict the time of death; instead use your assessments to help family members anticipate what is happening. Share your observations and through your role modeling encourage a sense of patience, compassion, and comfort throughout the dying process.

After death assist the family with decision making such as notification of a funeral home, transportation of family members, and collection of the patient’s belongings. Nurses are a primary source of family support. Remember that, because of differing responses to grief, some family members prefer to be alone at the time of a death, whereas others want to be surrounded by a support community. When uncertain about what a family member prefers for support, pose simple questions and offer suggestions for assistance.

With the death of a patient, family members benefit from the many resources of the health care team. When the patient chooses to die at home, family members provide direct care, which is often emotionally stressful and physically exhausting. In the home setting fatigued family caregivers benefit from respite care. During respite care, a patient temporarily receives care from others so family members are able to get away to rest and relax. Hospice program benefits include some days of respite care. Inform family members of home care, hospice, and community service options so they can access the best resources for their situation.

Assist with End-of-Life Decision Making: Patients and family members often face complex treatment decisions at the end of life. Decisions the family often need to make include: Which medical interventions would the patient want to use? Should life-extending treatments be stopped if there appears to be little chance of recovery? Should artificial nutrition and hydration be provided when a patient is near death and no longer able to eat? (Wainwright and Gallagher, 2007). They need time and careful explanations by nurses and other health care providers to make decisions (Mahon, 2010).

Difficult ethical decisions at the end of life complicate a survivor’s grief, create family divisions, or increase family uncertainty at the time of death (see Chapter 22). When ethical decisions are handled well, survivors achieve a sense of control and experience a meaningful conclusion to their loved one’s death. Suggest to patients that they clearly communicate their wishes for end-of-life care so family members are able to act as faithful surrogates when the patient can no longer speak for himself or herself. Advance directives often decrease the stress of family members when end-of-life decisions must be made (see Chapter 23) (Tilden et al., 2001). Some patients and family members rely on the nurse and other members of the health care team to initiate discussions regarding end-of-life care. Nurses often provide options that family members do not know are available and are advocates for patients and family members making decisions at the end of life.

Facilitate Mourning: Nurses who work with grieving family members often provide bereavement care after the patient’s death. Helpful strategies for assisting grieving persons include the following:

• Help the survivor accept that the loss is real. Discuss how the loss or illness occurred or was discovered, when, under what circumstances, who told him or her about it, and other factual topics to reinforce the reality of the event and put it in perspective.

• Support efforts to adjust to the loss. Use a problem-solving approach. Have survivors make a list of their concerns or needs, help them prioritize, and lead them step-by-step through a discussion of how to proceed. Encourage survivors to ask for help.

• Encourage establishment of new relationships. Reassure people that new relationships do not mean that they are replacing the person who has died. Encourage involvement in nonthreatening group social activities (e.g., volunteer activities or church events).

• Allow time to grieve. “Anniversary reactions” (i.e., renewed grief around the time of the loss in subsequent years) are common. A return to sadness or the pain of grief is often worrisome. Openly acknowledge the loss, provide reassurance that the reaction is normal, and encourage the survivor to reminisce.

• Interpret “normal” behavior. Being distractible, having difficulty sleeping or eating, and thinking that they have heard the deceased’s voice are common behaviors following loss. These symptoms do not mean that an individual has an emotional problem or is becoming ill. Reinforce that these behaviors are normal and will resolve over time.

• Provide continuing support. Survivors need the support of a nurse with whom they have bonded for a time following a loss, especially in home care or hospice nursing. The nurse has become an important “actor” in the drama of the deceased’s life and death and has helped them through some very intimate and memorable times. Attachment for awhile after the death is appropriate and healing for both the survivor and the nurse.

• Be alert for signs of ineffective, potentially harmful coping mechanisms such as alcohol and substance abuse or excessive use of over-the-counter analgesics or sleep aids.

Care After Death

Federal and state laws require institutions to develop policies and procedures for certain events that occur after death: requesting organ or tissue donation, performing an autopsy, certifying and documenting the occurrence of a death, and providing safe and appropriate postmortem care. In accordance with federal law, a specially trained professional (e.g., transplant coordinator or social worker) makes requests for organ and tissue donation at the time of every death. The person requesting organ or tissue donation provides information about who can legally give consent, which organs or tissues can be donated, associated costs, and how donation affects burial or cremation.

In extremely stressful circumstances created by the loss of a loved one, grieving survivors usually cannot remember all they were told. Nurses provide support and reinforce and clarify explanations given to them during the request process. In addition, understanding the physiology of organ donation is often difficult for family members. Even though a patient who is brain dead is legally declared dead, he or she remains on life support to provide the vital organs with blood and oxygen before transplant. The appearance of a live-looking body confuses the family, and they need help to understand that the life support is only preserving the vital organs. Nonvital tissues such as corneas, skin, long bones, and middle ear bones are taken at the time of death without artificially maintaining vital functions. If the deceased has not left behind instructions concerning organ and tissue donation, the family gives or denies consent at the time of death. Review your state organ retrieval laws and institutional policy and procedure regarding the formal consent process. Be aware that the laws governing who to approach for organ donation may not be acceptable in other cultures.

Family members give consent for an autopsy (i.e., the surgical dissection of a body after death) to determine the exact cause and circumstances of death or discover the pathway of a disease (see Chapter 23). In most cases a coroner or medical examiner determines the need to perform an autopsy. Law sometimes requires that an autopsy be performed when death is the result of foul play; homicide; suicide; or accidental causes such as motor vehicle crashes, falls, the ingestion of drugs, or deaths within 24 hours of hospital admission. Unattended deaths or those that occur in the workplace or during incarceration also usually require an autopsy (AMA, 2004).

Usually the physician or other designated health care provider asks for autopsy permission while the nurse answers questions and supports the family’s choices. Inform family members that an autopsy does not deform the body and that all organs are replaced in the body. Family members are often comforted to know that others may be helped by either the gift of organ and tissue donation or through autopsy. Respect and honor family wishes and final decisions.

Documentation of a death provides a legal record of the event. Follow agency policies and procedures carefully to provide an accurate and reliable medical record of all assessments and activities surrounding a death. Physicians or coroners sign some medical forms such as a request for autopsy, but the registered nurse gathers and records much of the remaining information surrounding a death. Nurses also usually witness or delegate the signing of forms (e.g., release of body or personal belongings forms). Nursing documentation becomes relevant in risk management or legal investigations into a death, underscoring the importance of accurate, legal reporting. Documentation also validates success in meeting patient goals or provides justification for changes in treatment or expected outcomes. Box 36-9 lists important documentation elements for end-of-life care.

Family members deserve and expect a clear description of what happened to their loved one, especially in cases of sudden, unusual, or unexpected circumstances. Give only factual information in a nonjudgmental, objective manner and avoid sharing your opinions. State law and agency policy govern the sharing of the written medical record information, which usually involves a written request. Follow legal guidelines for documentation and sharing of medical records (see Chapter 23).

When a patient dies in an institutional or home care setting, nurses provide or delegate postmortem care, the care of a body after death. Above all, a human body deserves the same respect and dignity as a living person and needs to be prepared in a manner consistent with the patient’s cultural and religious beliefs. Death produces physical changes in the body quite quickly; thus you need to perform postmortem care as soon as possible to prevent discoloration, tissue damage, or deformities.

Maintaining the integrity of cultural and religious rituals and mourning practices at the time of death gives survivors a sense of fulfilled obligations and promotes acceptance of the patient’s death (Box 36-10). The ability of families to mourn in a manner consistent with cultural values helps survivors experience some predictability and control in an otherwise uncertain and confusing time. Some cultures consider “family” as more than a nuclear biological unit. Health care providers need to understand the makeup of a family network and know which individuals to involve in end-of-life decisions and care.