Culture and Ethnicity

• Describe social and cultural influences in health, illness, and caring patterns.

• Differentiate culturally congruent from culturally competent care.

• Describe steps toward developing cultural competence.

• Identify major components of cultural assessment.

• Use cultural assessment to identify significant values, beliefs, and practices critical to nursing care of individuals experiencing life transitions.

• Demonstrate nursing interventions that achieve culturally congruent care.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

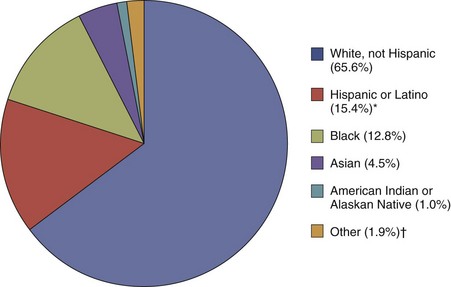

The demographic profile of the United States is changing dramatically as a result of immigration patterns and significant increases in culturally diverse populations already residing in the country. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, approximately 33% of the population currently belongs to a racial or ethnic minority group (Fig. 9-1). The U.S. Census also projects that this percentage will increase to 50% by the year 2050 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Because it is important to care for people holistically, nurses need to integrate culturally congruent care within their nursing practice.

FIG. 9-1 Summary of U.S. Census Data. (Data from U.S. Census Bureau: State and county quick facts, 2010, http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html.) *Hispanics may be of any race, so they are also included in applicable race categories; therefore total percentages are greater than 100%. †Includes Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and people reporting two or more races.

Health Disparities

Despite significant improvements in the overall health status of the U.S. population in the last few decades, disparities in health status among ethnic and racial minorities continues to be a serious local and national challenge. The Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities (2007a) reports that minority populations are more likely to have poor health and die at an earlier age because of a complex interaction among genetic differences, environmental and socioeconomic factors, and specific health behaviors such as the use of herbs to prevent or treat illnesses. Racial and ethnic minorities are more likely than white non-Hispanics to be poor or near poor. In addition, Hispanics, African Americans, and some Asian subgroups are less likely than white non-Hispanics to have a high school education. In general, racial and ethnic minorities often experience poorer access to health care and lower quality of preventive, primary, and specialty care. Eliminating such disparities in health status of people from diverse racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds has become one of the two most important priorities of Healthy People 2020 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010). Populations with health disparities have a significantly increased incidence of diseases or increased morbidity and mortality when compared to the health status of the general population.

Understanding Cultural Concepts

The Office of Minority Health (OMH) (2005) describes culture as the thoughts, communications, actions, customs, beliefs, values, and institutions of racial, ethnic, religious, or social groups. Culture is a concept that applies to a group of people whose members share values and ways of thinking and acting that are different from those of people who are outside the group (Srivastava, 2007).

Culture has both visible (easily seen) and invisible (less observable) components. The invisible value-belief system of a particular culture is often the major driving force behind visible practices. For example, although an Apostolic Pentecostal woman can be identified by her long hair, no makeup, and the wearing of a skirt or dress, nurses cannot appreciate the meanings and beliefs associated with her appearance without further assessment. Apostolic Pentecostals believe that a woman’s hair is her glory and should never be cut. Likewise, they believe that men and women need to dress differently and women need to be modest (wearing no makeup). These outward signs symbolize their belief in the scriptural definition of womanhood (United Pentecostal Church International, 2011). Cutting a woman’s hair without consent of the individual or her family is sacrilegious and violates the ethnoreligious identity of the person. On the other hand, a woman of another faith who wears her hair long does not attach meaning to the length of her hair but wears it long because of a fashion preference.

In any society there is a dominant culture that exists along with other subcultures. Although subcultures have similarities with the dominant culture, they maintain their unique life patterns, values, and norms. In the United States the dominant culture is Anglo-American with origins from Western Europe. Subcultures such as the Appalachian and Amish cultures are examples of ethnic and religious groups with characteristics distinct from the dominant culture. Primary and secondary characteristics of culture are defined by the degree to which an individual identifies with his or her cultural group. Primary characteristics include nationality, race, gender, age, and religious beliefs. Secondary characteristics include socioeconomic and immigration status, residential patterns, personal beliefs, and political orientation.

Significant influences such as historical and social realities shape an individual’s or group’s worldview. Worldview is woven into the fabric of one’s culture. It determines how people perceive others, how they interact and relate with reality, and how they process information (Walker et al., 2010). It is important that the nurse advocates for the patient based on the patient’s worldview. Plan and provide nursing care in partnership with the patient to ensure that it is safe, effective, and culturally sensitive (McFarland and Eipperle, 2008).

Ethnicity refers to a shared identity related to social and cultural heritage such as values, language, geographical space, and racial characteristics. Members of an ethnic group feel a common sense of identity. Some declare their ethnic identity to be Irish, Vietnamese, or Brazilian. Ethnicity is different from race, which is limited to the common biological attributes shared by a group such as skin color (Dein, 2006). Examples of racial classifications include Asian and Caucasian.

Worldview refers to “the way people tend to look out upon the world or their universe to form a picture or value stance about life or the world around them” (Leininger, 2006). In any intercultural encounter there is an insider or native perspective (emic worldview) and an outsider perspective (etic worldview). For example, after giving birth, a Korean woman requests seaweed soup for her first meal. This request puzzles the nurse. Although the nurse has an emic view of professional postpartum care, as an outsider to the Korean culture he or she is not aware of the significance of the soup to the patient. Conversely, the Korean patient who has an etic view of American professional care assumes that seaweed soup is available in the hospital because it cleanses the blood and promotes healing and lactation (Edelstein, 2011). Unless the nurse seeks the patient’s emic view, he or she is likely to suggest other varieties of soups available from the dietary department, disregarding the cultural meaning of the practice to the patient.

The processes of enculturation and acculturation facilitate cultural learning. Socialization into one’s primary culture as a child is known as enculturation. In contrast, acculturation is a second-culture learning that occurs when the culture of a minority is gradually displaced by the culture of the dominant group in the process of assimilation (Cowan and Norman, 2006). When the process of assimilation occurs, members of an ethnocultural community are absorbed into another community and lose their unique characteristics such as language, customs, and ethnicity. Assimilation may be spontaneous, which is usually the case with immigrants, or forced, as is often the case of the assimilation of ethnic minority communities. Biculturalism (sometimes known as multiculturalism) occurs when an individual identifies equally with two or more cultures (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008).

It is easy for nurses to stereotype cultural groups after reading generalized information about various ethnic minority practices and beliefs (Dein, 2006). Avoid stereotypes or unwarranted generalizations about any particular group that prevents further assessment of the individual’s unique characteristics. It is also important to determine how many of an individual’s life patterns are consistent with his or her heritage (Armer and Radina, 2006).

Culturally Congruent Care

Leininger (2002) defines transcultural nursing as a comparative study of cultures to understand similarities (culture universal) and differences (culture-specific) across human groups. The goal of transcultural nursing is culturally congruent care, or care that fits the person’s life patterns, values, and a set of meanings. Patterns and meanings are generated from people themselves rather than predetermined criteria. Culturally congruent care is sometimes different from the values and meanings of the professional health care system. Discovering patients’ culture care values, meanings, beliefs, and practices as they relate to nursing and health care requires nurses to assume the role of learners and partner with patients and families in defining the characteristics of meaningful and beneficial care (Leininger and McFarland, 2002). Effective nursing care needs to integrate the cultural values and beliefs of individuals, families, and communities (Webber, 2008).

Cultural competence is the process of acquiring specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes to ensure delivery of culturally congruent care (Campinha-Bacote, 2002). This process has five interlocking components:

1. Cultural awareness: An in-depth self-examination of one’s own background, recognizing biases, prejudices, and assumptions about other people

2. Cultural knowledge: Obtaining sufficient comparative knowledge of diverse groups, including their indigenous values, health beliefs, care practices, worldview, and bicultural ecology

3. Cultural skills: Being able to assess social, cultural, and biophysical factors influencing treatment and care of patients

4. Cultural encounters: Engaging in cross-cultural interactions that provide learning of other cultures and opportunities for effective intercultural communication development

5. Cultural desire: The motivation and commitment to caring that moves an individual to learn from others, accept the role as learner, be open and accepting of cultural differences, and build on cultural similarities

Specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes are required in the delivery of culturally congruent care to individuals and communities. Nurses who provide culturally competent care bridge cultural gaps to provide meaningful and supportive care for patients. For example, a nurse assigned to a female Egyptian patient decides to seek information about the Egyptian culture. On learning that Egyptians value female modesty and gender-congruent care, the nurse encourages female relatives to help the patient meet her needs for personal hygiene. The nurse’s cultural encounter enhances understanding of the nonverbal cues of the patient’s discomfort with lack of privacy.

Implementing culturally competent care requires support from health care agencies. For example, a nurse who is aware of Gypsy culture and skilled in dealing with Gypsy families is not able, as an individual, to provide for a Gypsy family’s need to be present in groups near the bedside of a hospitalized family member. The nurse needs organizational support in adapting space resources to accommodate the volume of visitors who will remain with the patient for long periods.

Because patients who seek care could be from countless different world cultures, it is unlikely that a nurse could be competent in all cultures of the world. However, nurses can have general knowledge and skills to prepare them to provide culturally sensitive care, regardless of the patient’s and family’s culture (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008).

Cultural Conflicts

Culture provides the context for valuing, evaluating, and categorizing life experiences. Cultural groups transmit their values, morals, and norms from one generation to another, which predisposes members to ethnocentrism, a tendency to hold one’s own way of life as superior to others. Ethnocentrism is the cause of biases and prejudices that associate negative permanent characteristics with people who are different from the valued group. When a person acts on these prejudices, discrimination occurs. For example, a nurse refuses to give prescribed pain medication to a young African male with sickle cell anemia because of the nurse’s belief (stereotyped bias) that young male Africans are likely to be drug abusers. Nurses and other health care providers who have cultural ignorance or cultural blindness about differences generally resort to cultural imposition and use their own values and lifestyles as the absolute guide in dealing with patients and interpreting their behaviors. Thus a nurse who believes that people should bear pain quietly as a demonstration of strong moral character is annoyed when a patient insists on having pain medication and denies the patient’s discomfort.

Cultural Context of Health and Caring

Culture is the way in which groups of people make sense of their experiences relevant to life transitions such as birth, illness, and dying. For example, in most African groups a thin body is a sign of poor health. In some Hispanic cultures a plump baby is perceived as healthy. Traditionally in Arab culture pregnancy is not a medical condition but rather a normal life transition; thus a pregnant woman does not always go to a health care provider unless she has a problem (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008).

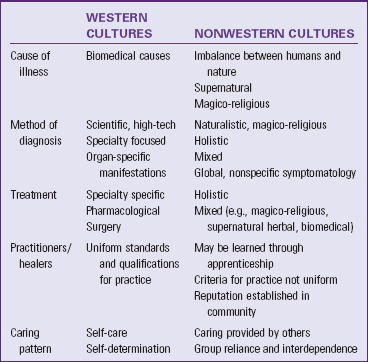

Table 9-1 provides a comparison of cultural contexts of health and illness in western and nonwestern cultures. Cultural beliefs highly influence what people believe to be the cause of illness. For example, many Hmong refugees (group of people who originated from the mountainous regions of Laos) believe that epilepsy is caused by the wandering of the soul. Treatment includes intervention by a shaman who performs a ritual to retrieve the patient’s soul (Fadiman, 1997; Helsel et al., 2005). Their belief is distinct from the scientifically determined neurological abnormality causing seizures. The biomedical orientation of western cultures emphasizing scientific investigation and reducing the human body to distinct parts is in conflict with the holistic conceptualization of health and illness in nonwestern cultures. Holism is evident in the belief in continuity between humans and nature and between human events and metaphysical and magico-religious phenomena. Therefore for the Hmong people epilepsy is connected to the magical and supernatural forces in nature. Establishing a diagnosis of epilepsy in western cultures requires scientifically proven techniques and confirmed criteria for the abnormality. Such medical criteria are meaningless to the Hmong, who believe in the global causation of the illness that goes beyond the mind and body of the person to forces in nature. A Hmong seeks a shaman, whereas a westerner seeks a neurologist. A shaman has an established reputation in the Hmong community, whose qualifications for healing are neither determined by published standardized criteria nor confined to specific bodily systems. A shaman uses rituals symbolizing the supernatural, spiritual, and naturalistic modalities of prayers, herbs, and incense burning.

TABLE 9-1

Comparative Cultural Contexts of Health and Illness

Data from Foster G: Disease etiologies in non-Western medical systems, Am Anthropol 78:773,1976; Kleinman A: Patients and healers in the context of culture, Berkeley, 1979, University of California Press; and Leininger MM, McFarland MR: Transcultural nursing: concepts, theories, research and practice, ed 3, New York, 2002, McGraw-Hill.

The dominant value orientation in North American society is individualism and self-reliance in achieving and maintaining health. Caring approaches generally promote the patient’s independence and ability for self-care. In collectivistic cultures that value group reliance and interdependence such as traditional Asians, Hispanics, and Africans, caring behaviors require actively providing physical and psychosocial support for family or community members. An adult patient is not expected to be solely responsible for his or her care and well-being; rather, family and kin are relied on to make decisions and provide care (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008). For example, a traditional older Chinese woman refuses to independently perform rehabilitation exercises after hip surgery until her daughter is present. The western health care provider interprets this as a lack of self-responsibility and motivation for her care. In contrast, the patient interprets the nurse’s insistence on self-care as uncaring behavior.

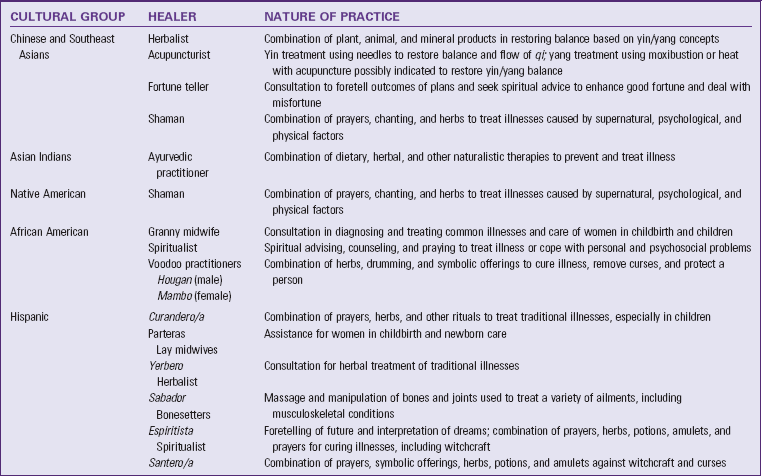

Cultural Healing Modalities and Healers

Foster (1976) identified two distinct categories of healers cross-culturally. Naturalistic practitioners attribute illness to natural, impersonal, and biological forces that cause alteration in the equilibrium of the human body. Healing emphasizes use of naturalistic modalities, including herbs, chemicals, heat, cold, massage, and surgery. In contrast, personalistic practitioners believe that an external agent, which can be human (i.e., sorcerer) or nonhuman (e.g., ghosts, evil, or deity), causes health and illness. Personalistic beliefs emphasize the importance of humans’ relationships with others, both living and deceased, and with their deities. For example, a voodoo priest uses modalities that combine supernatural, magical, and religious beliefs through the active facilitation of an external agent or personalistic practitioner. A Haitian woman who believes in voodoo attributes her illness to a curse placed by someone and seeks the services of a voodoo priest to remove the cause. Personalistic approaches also include naturalistic modalities such as massage, aromatherapy, and herbs (see Chapter 32). Some patients seek both types of practitioners and use a combination of modalities to achieve health and treat illness. Different cultural groups in the United States use a variety of cultural healers (Table 9-2).

TABLE 9-2

Data from Hautman MA: Folk health and illness beliefs, Nurse Pract 4(4):23, 1976; Loustaunau MO, Sobo EJ: The cultural context of health, illness and medicine, Westport, Conn, 1997; Spector RE: Cultural diversity in health and illness, ed 6, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 2004, Prentice Hall.

Avoid making rash judgments about patients’ practices when they use both healing systems at the same time. In addition, gain knowledge and understanding of remedies used by patients to prevent cultural imposition. For example, many Southeast Asian cultures practice folk remedies such as coining (rubbing a coin roughly on the skin), cupping (placing heated cups on the skin), pinching, and burning to relieve aches and pains and remove bad wind or noxious elements that cause illness. Other groups, including eastern Europeans, use cupping as treatment for respiratory ailments. These remedies leave peculiar visible markings on the skin in the form of ecchymosis, superficial burns, strap marks, or local tenderness. Cultural ignorance of these practices causes a practitioner to call authorities for suspicion of abuse.

Culture-Bound Syndrome

Human groups create their own interpretation and descriptions of biological and psychological malfunctions within their unique social and cultural context (Dein, 2006). Culture-bound syndromes are illnesses that are specific to one culture. They are used to explain personal and social reactions of the members of the culture. Culture-bound syndromes occur in any society. In the United States “going postal,” which refers to extreme and uncontrollable anger in the workplace that may result in shooting people, is now considered a culture-bound syndrome (Flaskerud, 2009). Hwa-byung is a Korean culture-bound syndrome observed among middle-age, low-income women who are overwhelmed and frustrated by the burden of caregiving for their in-laws, husbands, and children. Symptoms are generally somatic manifestations consisting of insomnia, fatigue, anorexia, indigestion, feelings of an epigastric mass, palpitations, heat, panic, feelings of impending doom, and dyspnea. Women unconsciously avoid expressions of symptoms that counter the cultural ideal of females as the caretaker of older adults, husbands, and children. Symptoms reflect the cultural definition of illness as imbalance between heat (yang) and cold (yin) (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008).

Culture and Life Transitions

Cultures generally mark transitions to different phases of life by rituals that symbolize cultural values and meanings attached to these life passages. Van Gennep (1960) originated the concept of rites of passage as significant social markers of changes in a person’s life. Examining the practices surrounding these life events provides a view of the cultural meanings and expressions relevant to these transitions. For example, sending flowers and get-well greetings to a sick person is a ritual showing love and care for the patient in the dominant American culture in which privacy is valued. In collectivistic groups such as the Hispanic culture, physical presence of loved ones with the patient during illness demonstrates caring.

Pregnancy

All cultures value reproduction because it promotes continuity of the family and community. Pregnancy is generally associated with caring practices that symbolize the significance of this life transition in women. Infertility in a woman is considered grounds for divorce and rejection among Arabs. Pregnancy that occurs outside of accepted societal norms is generally taboo. Among traditional Muslims pregnancy out of wedlock sometimes results in the family’s imposing severe sanctions against the female member (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008).

Some cultures that subscribe to the hot and cold theory of illness such as many Asian and Hispanic cultures view pregnancy as a hot state; thus they encourage cold foods such as milk and milk products, yogurt, sour foods, and vegetables (Edelstein, 2011). They believe that hot foods such as chilies, ginger, and animal products cause miscarriage and fetal abnormality. Modesty is a strong value among Afghan (Omeri et al., 2006) and Arab women (Kulwicki et al., 2005). These women sometimes avoid or refuse to be examined by male health care providers because of embarrassment. Religious beliefs sometimes interfere with prenatal testing, as in the case of a Filipino couple refusing amniocentesis because they believe that the outcome of pregnancy is God’s will and not subject to testing.

Childbirth

How individuals express pain and the expectation about how to treat suffering varies cross-culturally and in different religions. For example, Vietnamese women are often stoic regarding the pain of childbirth because their culture views childbirth pain as a normal part of life (McLachlan and Waldenstrom, 2005). Traditional Puerto Rican and Mexican women often vocalize their pain during labor and avoid breathing through their mouths because this causes the uterus to rise. Traditional Arab Americans are sometimes physically or verbally more expressive when experiencing pain. Fear of drug addiction and the belief that pain is a form of spiritual atonement for one’s past deeds motivate most Filipino mothers to tolerate pain without much complaining or asking for medication. Religious beliefs sometimes prohibit the presence of males, including husbands, from the delivery room. This often occurs among devout Muslims, Hindus, and Orthodox Jews (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008).

Health care providers other than physicians attend childbirth in some groups such as parteras among Mexicans, herb doctors among Appalachian and southern African Americans, and hilots among Filipinos (Nelms and Gorski, 2006). Known in their communities, these practitioners are affordable and accessible in remote areas. They use a combination of naturalistic, religious, and supernatural modalities combining herbs, massage, and prayers.

Newborn

The definition of newborn and how age is counted in children varies in some cultures. Among traditional Vietnamese and Koreans a newborn is 1 year old at birth. Once acculturated to the U.S. culture, they assume a bicultural view, deducting 1 year from the age of the child when speaking to an outsider. Naming ceremonies vary by culture. In the Yoruba tribes in Nigeria, the baby is named at the official naming ceremony that occurs 8 days after birth and coincides with circumcision. Many cultures around the world greatly celebrate the birth of a son, including Chinese, Asian Indians, Islamic groups, and Igbos in West Africa.

The name of the child often reflects cultural values of the group. It is typical for a Hispanic baby to have several first names followed by the surnames of the father and mother (e.g., Maria Kristina Lourdes Lopez Vega). The bilineal tracing of descent from both the mother’s and father’s side in Hispanic groups differs from the patrilineal system, in which the last name of the father precedes the child’s first name. In the Chinese culture individuals trace descent only from the paternal side. Thus the name Chen Lu means that Lu is the daughter of Mr. Chen.

Newborns and young children are often considered vulnerable, and societies use a variety of ways to prevent harm to the child. Among the mostly Catholic Filipinos, parents keep the newborn inside the home until after the baptism to ensure the baby’s health and protection. Traditional Arabs and Iranians believe that babies are vulnerable to cold and wind; thus they wrap them in blankets.

Postpartum Period

In many nonwestern cultures the postpartum period is associated with vulnerability of the mother to cold. To restore balance mothers do not shower and take sponge baths. Some groups have special dietary practices to restore balance. Cultural groups have preferences in terms of what types of foods are appropriate to restore balance in women after birth. Some Chinese mothers prefer soups, rice, rice wine, and eggs; whereas Guatemalan women avoid beans, eggs, and milk during the postpartum period (Edelstein, 2011). The length of the postpartum period is generally much longer (30 to 40 days) in nonwestern cultures to provide support for the mother and her baby (Chin et al., 2010).

Filipino, Mexicans, and Pacific Islanders use an abdominal binder to prevent air from entering the woman’s uterus and to promote healing (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008). Among Orthodox Jewish, Islamic, and Hindu cultures, bleeding is associated with pollution. A woman goes into a ritual bath after bleeding stops before she is able to resume relations with her husband (Lewis, 2003). In some African cultures such as in Ghana and Sierra Leone some women do not resume sexual relations with their husbands until the baby is weaned.

Grief and Loss

Dying and death bring traditions that are meaningful to groups of people for most of their lives (see Chapter 36). When traditional medical measures fail, cultural beliefs and practices that are religious and spiritual become the focus. Societies assign different meanings to death of a child, a young person, and an older adult (Box 9-1). In western cultures with strong future time orientation and in which a child is expected to survive his or her parents, death of a young person is devastating. However, in other cultures, in which infant mortality is very high, the emotional distress over a child’s death is tempered by the reality of the commonly observed risks of growing up. Thus the untimely death of an adult is sometimes mourned more deeply.

People such as devout Hindus and Buddhists who believe in the concept of reincarnation view death as a step toward rebirth. Care of the dying focuses on supporting the patient’s preparation for a good death. The family prays and reads religious scriptures to the patient to improve his or her chances in the next cycle. Buddhists generally believe that life is suffering and suffering ends when a person moves beyond the earthly desires and atones for past misdeeds. When a Hindu dies, the body is bathed, massaged in oil, dressed in clean clothes, and cremated before the next sunrise to ensure that the soul passes quickly from this life to the next (Lobar et al., 2006).

Culture strongly influences pain expression and need for pain medication. A typical American believes that individual freedom and autonomy are synonymous with freedom from pain and suffering, but other groups accept suffering. Do not assume that all people value pain relief equally. Patients suffer cultural pain when health care providers disregard values or cultural beliefs (Maputle and Jali, 2006). Inability of Orthodox Jews to pray in groups at the bedside with the dying patient because of limitations in the number of visitors allowed causes cultural pain in the patient and family. Working with the family and their religious/spiritual leader facilitates culturally congruent care (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008).

Organizational policies need to be sensitive to patients’ cultural life patterns, especially during times of grief and loss. The dominant values in American society of individual autonomy and self-determination are often in direct conflict with diverse groups. Advance directives, informed consent, and consent for hospice are examples of mandates that sometimes violate patients’ values. Informed consent and advance directives protect the right of the individual to know and make decisions ensuring continuity of these rights, even when the individual is incapacitated. However, in some cultures the designated family members assume decision making during illness and are trusted to make the right decision for the individual. Some groups such as African Americans, Asian Americans, and Hispanics expect their families to make decisions for them; and family members prefer to protect the individual from unnecessary suffering by knowing the reality of imminent death. These cultures value group interdependence and view individual autonomy as an unnecessary burden for a loved one who is ill (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008).

The meaning and expressions of grief vary from culture to culture. The color black is not always a symbol of grief. Hindu mourners wear white. Among the usually reserved East Asians, the extent to which mourners publicly express grief reflects the social position and status of the deceased. Muslims do not encourage wailing, but crying is permitted. Muslim women are discouraged from visiting cemeteries (Lobar et al., 2006). Korean families sometimes hire people to lead the open grieving. Loud crying and screaming are common.

Religious beliefs also affect attitudes toward cremation, organ donation, and the treatment of body parts. Devout Muslims refuse an autopsy or organ donation for fear of desecrating the dead and because of their belief that one has to be whole to appear in front of the creator. Many prefer burial over cremation (Lobar et al., 2006).

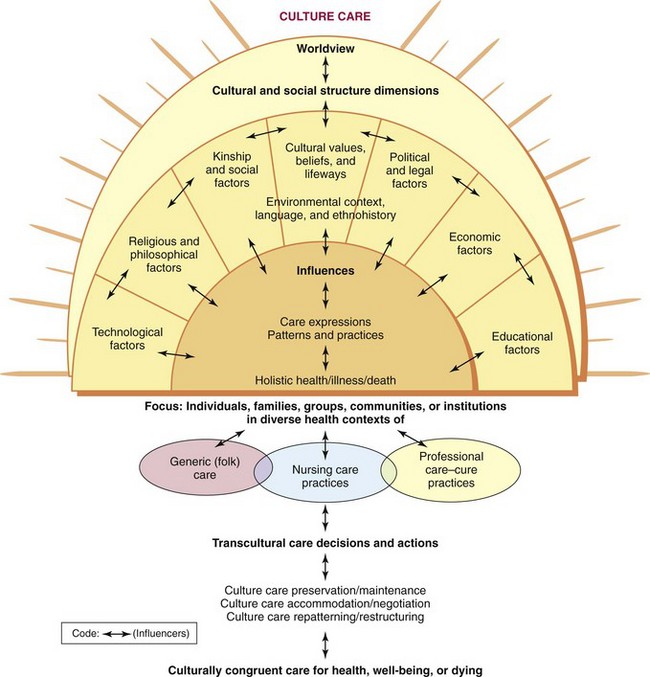

Cultural Assessment

Cultural assessment is a systematic and comprehensive examination of the cultural care values, beliefs, and practices of individuals, families, and communities. The goal of cultural assessment is to gather significant information from the patient that enables the nurse to implement culturally congruent and safe patient care (Box 9-2). For example, it allows the nurse to gather information about which foods are culturally acceptable and whether the person practices alternative medicine and to assess pain (Maier-Lorentz, 2008). There are several models for cultural assessment, each involving different levels of skill and knowledge. Leininger’s Sunrise Model (2002) in Fig. 9-2 demonstrates the inclusiveness of culture in everyday life and helps to explain why cultural assessment needs to be comprehensive. The model assumes that cultural care values, beliefs, and practices are fixed in the cultural and social structural dimensions of society, which include environmental context, language, and ethnohistory. Ethnohistory refers to significant historical experiences of a particular group. For example, many older Americans tend to be frugal and save everything because of their experience with the Great Depression. These patient’s stories reveal the broad picture of who they are and the cultural lifestyle they embrace. Leininger’s model differentiates folk care, which is caring as defined by the people, from health care, which is provided by health care professionals and based on the scientific, biomedical caring system.

FIG. 9-2 Leininger’s culture care theory and sunrise model. (Reprinted with permission from Leininger MM, McFarland MR: Transcultural nursing: concepts, theories, research and practice, ed 3, New York, 2002, McGraw-Hill.)

Census Data

A nurse begins cultural assessment by knowing population demographic changes in the community setting of practice. Having background knowledge of a culture assists the nurse in conducting a focused assessment. Gather demographics from the local and regional census data and from the demographic breakdown of patients who come to the health care setting. Population demographics include the distribution of ethnic groups, education, occupations, and incidence of the most common illnesses. Comprehensive cultural assessment requires skill and time; preparation and anticipation of need are important.

Asking Questions

One problem in cultural assessment is failing to assess the insider or emic perspective of patients and interpret information during the assessment. Use open-ended, focused, and contrast questions. The aim is to encourage patients to describe values, beliefs, and practices that are significant to their care that health care providers will take for granted unless otherwise uncovered. Culturally oriented questions are by nature broad and require many descriptions (Box 9-3).

Establishing Relationships

In contrast to other types of interviews, cultural assessment is intrusive and time consuming and requires a trusting relationship between participants. Miscommunication commonly occurs in intercultural interactions. This is because of language and communication differences between and among participants and differences in interpreting each other’s behaviors. Nurses use transcultural communication skills to interpret the patient’s behavior within his or her own context of meanings and to behave in a culturally congruent way. Transcultural communication manages the impression the nurse makes on the patient to achieve desired outcomes of communication (Purnell and Paulanka, 2008). Transcultural communication requires linguistic skills, culturally congruent interpretation of behaviors of others, listening, and observation skills. In a cultural assessment the goal is to generate knowledge about the patient’s values, beliefs, and practices about nursing and health care. If the nurse’s behavior is offensive to the patient, he or she will not likely participate in the interaction.

To provide safe and effective patient care, you need to develop and use transcultural communication skills and be able to work with interpreters (Box 9-4). Interpreters are more effective when they have knowledge of the culture of the patient. They provide accurate accounts of what is said and, just as important, offer information regarding the cultural beliefs of the patient and family. Interpreters tactfully formulate culturally sensitive questions that provide the health care provider with needed information (Dysart-Gale, 2007). On admission nurses assess and document language(s) patients speak and write and determine if patients need an interpreter.

Federal mandates for culturally sensitive health care delivery require accommodation for language differences. According to the Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities (2007b), national standards regarding language services include:

• Providing language assistance services free of charge to all patients with limited English at all points of contact.

• Notifying patients, both verbally and in writing, of their rights to receive language-assistance services.

• Using interpreters for patients with limited English proficiency (unless the patient requests that family or friends interpret for them).

The Joint Commission (2010) requires that informed consent materials be in the patient’s language whenever possible and that an interpreter be available whenever discussing informed consent with a patient. If informed consent documents are not available in the patient’s language, The Joint Commission also recommends that the health care provider obtain verbal consent from the patient via the interpreter and that this is thoroughly documented in the patient’s medical record.

Nurses need to know their agencies’ policies and procedures regarding these mandates. Working with interpreters and patients with little or no fluency in English requires skill development. In hospital settings use an interpreter to communicate information about the patient’s medical condition. It is not suitable for family members to translate health care information, but they can assist with ongoing interaction during the patient’s care (Box 9-5).

Consider what needs to be discussed with a patient when selecting an interpreter. In some Hispanic and Asian groups a woman’s breasts and genitals generally are not discussed with members of the opposite sex, including male members of one’s family. In some societies, adults occupy a higher status than the young. Children in immigrant groups learn the English language faster than their parents because of their schooling experience in the new culture when they immigrate at a young age. However, assuming that children are ideal interpreters for their parents is an insult to the authority of the parent who has to take directions from a child.

Compatibility between the ethnic backgrounds of the interpreter and patient is another consideration to facilitate trust. An Israeli interpreter may cause much anxiety and distrust in a Palestinian immigrant who experienced violence from these groups in the home country. Socioeconomic and educational differences between interpreters and patients sometimes become barriers to effective interpretation. Interpreters need training not only in interpretation but also in knowing their role, which is to repeat back what the patient said without judging the content.

Selected Components of Cultural Assessment

Nurses learn various skills needed to gather an accurate and comprehensive cultural assessment. The following components of cultural assessment provide insight into the type of information that is useful in planning and delivering nursing care.

Family Structure

Integrate patients’ and families’ concepts of meaningful and supportive care into nursing care (see Chapter 7). Caring expressions integrate the central values of a culture. In collectivistic cultures caring means active involvement of the group, emphasizing mutual and reciprocal obligations of members to care for one another. When caring for patients from collective cultures, work with patients’ families as a group, looking for ways the family can participate in basic care activities. Understand the family’s social hierarchy and assume a collaborative role with patients and their families.

Culture differentiates caring roles of males and females. In many cultures caretaking tasks are the primary responsibility of women; men provide financial support and make major decisions. Age and position in the social hierarchy also influence caring roles and responsibilities. In some cultures older women are the first group consulted during illness of family members and in the care of women and children.

Ethnic Heritage and Ethnohistory

Knowledge of a patient’s country of origin and its history and ecological contexts are significant to health care. For example, Haitian immigrants have linguistic and communication patterns distinct from those of Jamaicans, even though they both come from the Caribbean and have a common history of slavery. Differences come from their colonial history and intermingling with the local indigenous people. As a result of cultural differences between India and Jamaica, Hindu immigrants from Jamaica have different cultural characteristics from those originating from India. Hindu immigrants from Jamaica often have nutritional, communication, and health patterns more similar to African Jamaicans than South Asian Hindus. In caring for an Indian Hindu who grew up in Jamaica, expect the patient to interact more like a Jamaican, even though the person looks like he or she is from south India.

Immigration from one country to another occurs for various reasons. Refugees are relocated without any choice in their initial residence, in contrast to immigrants, who have options as to where they go. Refugees experience greater dislocation and deprivation than immigrants who enter a new country with specialized skills and education and have the option to return to their homeland. Age of immigration often determines the level of acculturation, with younger immigrants acculturating faster than older immigrants. Although acculturation and length of residence in the new culture are related, other factors such as education, racial characteristics, and familiarity with the language affect the extent of a person’s acculturation. Ask patients about the condition or situation that brought them to the United States and how they think they are adjusting. Socioeconomic status in the new society is often not comparable to one’s previous status in the country of origin. New immigrants often begin with small resources but keep the values and desires of their previous economic status. Assess for problems (such as financial hardships, becoming comfortable with the language, or understanding the routines used to set medical appointments) to make reasonable and appropriate adjustments to care. Refer patients to community resources when possible.

Bicultural Effects on Health

Identify patients’ health risks related to sociocultural and biological history on admission. Some distinct health risks are the result of the ecological context of the culture. For example, immigrants originating from the region near the Nile River are generally at risk for parasitic infestations that are prevalent in that area. Immigrants from the Third World with poor sanitary conditions and water supply are at risk for infections such as hepatitis. Certain genetic disorders are also linked with specific ethnic groups such as Tay-Sachs among Ashkenazi Jews and malignant hypertension among African Americans. Lactose intolerance is frequently observed among Asians, Africans, and Hispanics (Office of Minority Health, 2005).

Social Organization

Cultural groups consist of units of organization defined by kinship, status, and appropriate roles for their members. In the dominant American society the most common unit of social organization is the nuclear family, in which married children and adults establish separate residences from their parents. Although different configurations of a family exist, the most common is the nuclear household made up of parents and their young children (see Chapter 10). In collectivistic cultures families are made up of distant blood relatives across three generations and fictive or nonblood kin. Kinship extends to both the father’s and mother’s side of the family (bilineal) or is limited to the side of either father (patrilineal) or mother (matrilineal). Patrilineally extended families exist among Chinese and Hindus, in which a woman moves into her husband’s clan after marriage and minimizes ties with her own parents and siblings. Consider all options when determining a patient’s next of kin. This is especially relevant to new immigrants and refugees, who often have not relocated with all members of their family. Collectivistic groups often regard members of their ethnic group as closest kin and want to consult them for health care decisions and permit them to speak on their behalf.

A patient’s status within the social hierarchy is generally linked with qualities such as age, gender, and achieved status such as education and position. The dominant culture in the United States emphasizes achievement as the determinant of status, whereas most collectivistic cultures give higher priority to age and gender. The eldest male is next to his father in terms of authority in many Asian and African cultures. A Korean mother is subject to the authority of her oldest son in the absence of her husband. Sometimes an adult Hispanic woman will not sign informed consent for surgery or other medical procedures without consulting her husband, oldest son, or brothers. Older adults occupy higher status in some societies, resulting in grandparents forcing their decisions over their married children regarding the care of the grandchildren. Determine who has authority for making decisions within the family and how to communicate with the proper individuals.

Culture defines the expected roles of its members. Certain behaviors are acceptable in children but not in adults. Gender also differentiates role expectations. For example, among devout Muslims females perform the task of caregiving, whereas males are the financial providers and major decision makers. Thus nurses need to anticipate that some Muslim women insist on staying at the bedside of their children, in-laws, or husbands. However, do not assume that, just because the woman is the primary caregiver, she will make decisions independently. Determine the family social hierarchy as soon as possible to prevent offending patients and their families. Working with established family hierarchy prevents delays and achieves better patient outcomes.

Religious and Spiritual Beliefs

Religious and spiritual beliefs frequently influence the patient’s worldview about health and illness, pain and suffering, and life and death. Determine the patient’s religious and spiritual beliefs and their effect on health care during admission. Also understand the emic perspective of your patients. For example, to a Hmong animist spirits are dead ancestors or forces external to the person. To some Americans spirituality means an inner, personal relationship with God. Although it is sometimes difficult to find the appropriate time to discuss religion and spirituality in a hospital setting, nurses need to assess what is important to the spiritual well-being of patients and learn as much as possible about their spiritual and religious practices (see Chapter 35).

Devout Muslims pray five times daily and undergo an obligatory ritual cleansing of some parts of their body before praying. Anticipate the ritual cleansing needs of the patient and provide privacy for praying. For example, reschedule diagnostic procedures to allow Buddhist patients to participate in the festivities of their New Year. Anticipating the needs of Orthodox Jewish patients during the Sabbath, when they refrain from using electrical appliances, requires creative accommodations by the staff such as placing articles of care near the patient so he or she does not need to use the call light or telephone to get assistance. Determine how to contact the patient’s next of kin who are unreachable by telephone during the Sabbath in case emergencies arise.

Religious beliefs are evident in patients’ dietary practices (Box 9-6). Devout Hindus avoid beef, and many are vegetarians. Many Buddhists are vegetarians as well. Halal foods, which include meat, fish, fresh fruit, vegetables, eggs, milk, and cheese, are permissible for Muslims. Halal meat comes from animals slaughtered during a prayer ritual. Prohibited, or Haram, foods include non-Halal meat, animals with fangs, pork products, gelatin products, and alcohol (Edelstein, 2011). Muslims fast during the daylight hours for the 28 days of Ramadan, which occurs during the ninth lunar month. Although children and sick and frail individuals are exempt from fasting, do not assume that these individuals eat regular meals during Ramadan. Rescheduling treatments and medications is often necessary to prevent complications such as hypoglycemia.

Jewish patients who follow a kosher diet avoid meat from carnivores, pork products, and fish without scales or fins. Kosher meat comes from permissible animals that are slaughtered with the least amount of suffering. Kosher foods must not be contaminated by nonkosher foods. Thus meat is served separately from dairy, and dishes used for serving and eating these products are also separated (Edelstein, 2011).

The nursing staff needs to have background information available about major holy days and practices for commonly encountered religions. Such information prevents scheduling nonemergency treatments and procedures on major holy days such as the Jewish holidays Yom Kippur, Rosh Hashanah, or Passover. Religious mandates followed by Jehovah’s Witnesses require followers to have bloodless surgery and avoid blood transfusions. Identify and contact patients’ religious and spiritual leaders before problems occur and work with these leaders to mediate in times of crisis.

Life transitions are often manifested in religious and spiritual beliefs. Male circumcision occurs among Jewish and Islamic groups. Female circumcision is common among some African and Muslim groups. Anointing of the sick is a Roman Catholic sacrament. Hospitalized Catholic patients often receive daily communion. The family of a critically ill Jewish patient turns his or her head eastward or to the right side. The family of a dying Hindu remains at the bedside to place a drop of the holy water from the River Ganges on the patient’s lips immediately after death to help his or her soul to the next life. A dying Hispanic patient is not left alone so a close kin is able to hear the patient’s wishes, allowing the soul to leave in peace.

Foods with Cultural Significance

Many foods have cultural significance and are adopted for traditional celebrations, medicinal purposes, and general nutritional health. For instance, in Italy it is a tradition to eat eel on Christmas Eve. It symbolizes a new beginning because eels replace their skin as they shed it. In Sweden the smorgasbord is an important part of special events such as holidays and weddings (Edelstein, 2011). Cake is a part of birthday and wedding celebrations in the United States. Russians consider honey to have healing qualities and use it to treat colds and coughs. Many Japanese follow traditional beliefs that food should be consumed as close to its natural state as possible, for instance raw fish (sashimi) used in making sushi.

Communication Patterns

Cultural groups have distinct linguistic and communication patterns. These patterns reflect core cultural values of a society. In the dominant American culture that supports individualism, people value assertive communication because it manifests the ideal of individual autonomy and self-determination. In collectivistic cultures the context of relationships among participants shapes communication. Promoting group harmony is a priority; thus participants interact based on their expected positions and relationships within the social hierarchy. Individuals are more likely to remain respectful and show deference to older adults or family leaders, even though they disagree on an issue. Differences in status and position, age, gender, and outsider versus insider determine the content and process of communication (Box 9-7). Among Asian cultures face-saving communication promotes harmony by indirect, ambiguous communication and conflict avoidance. In this culture spoken messages often have little to do with their meanings. Saying “no” to a superior or older person is not permissible. An affirmative response only means that “I heard you”; it is not full agreement. This type of response is likely to happen in a health care setting because a health care provider is perceived as a person of authority to some Asian, African, or Hispanic patients. Observing a patient’s behavior and clarifying messages heard from a trusted insider prevents misinterpretation.

In cultural groups with distinct linear hierarchy, negotiation of conflict occurs among people within the same level of position or authority. Identifying and working with established family hierarchy prevents miscommunication. In cultures with highly differentiated gender roles some patients place more value on the advice of a man than a woman. By recognizing and working within this cultural context, nurses become more effective in achieving outcomes.

Culture also shapes nonverbal communication. It influences the distance between participants in an interaction, the degree of eye contact, the extent of touching, and how much private information the patient shares. Patients use less distance when speaking to trusted insiders and persons of the same age, gender, and position in the social hierarchy. Many ethnic groups tend to speak their own dialect with insiders for ease and privacy and as a marker of insider status. To minimize this distance when communicating with patients, nurses establish rapport and behave in a culturally congruent manner through impression management.

Time Orientation

All cultures have past, present, and future time dimensions. This information is useful in planning a day of care, setting up appointments for procedures, and helping a patient plan self-care activities in the home. The dominant American culture is future-time oriented, and people from this culture tend to schedule their time. When working with patients who are future-time oriented, it is important to plan and adhere to a schedule (Srivastava, 2007). Future-time orientation minimizes present time; thus communication tends to be direct and focused on task achievement. The rushed, hurried, and businesslike communication of a future-time oriented person may appear uncaring or disrespectful to those who are present or past-time oriented.

In some cultures time is oriented to the present, and events take place when the person arrives. Present-time orientation is in conflict with the dominant future-time orientation in health care that emphasizes punctuality and adherence to appointments. Within present-time oriented cultures it is acceptable to be late to appointments. When making appointments and referrals, explore and manage anticipated barriers to time adherence with the patient. Anticipate conflicts and make adjustments when caring for ethnic groups that value present-time orientation. African Americans, Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, Chinese, and Native Americans are some of the groups that value present-time orientation (Giger and Davidhizar, 2008). Past-time orientation is associated with adaptive cultures and populations who are exposed to situations that require immediate action such as immigrant populations (Crockett et al., 2009). Improving a patient’s access to health services mandates culturally congruent time schedules that accommodate cultural patterns.

Caring Beliefs and Practices

Obtain information about folk remedies and cultural healers that the patient uses. Assessment data yield information about the patient’s beliefs about the illness and the meaning of the signs and symptoms. Focus assessment on the emic perspective of the patient. Allowing the patient to describe the meanings of care and identify caring behaviors is fundamental to culturally congruent care.

Experience with Professional Health Care

Understanding the emic perspective of the patient about professional health care is valuable in correcting misconceptions and preventing culturally offensive actions. Previous encounters with professional caregivers affect patients’ adherence to therapies and continuing access of services. For example, if a patient previously had problems with male caregivers, assign female caregivers to the patient whenever possible. If a patient perceives an essential health care resource to be inaccessible, help to find a way to connect the patient with the resource. Partnership between health care professionals and the community provides proactive and open feedback from culturally diverse patient groups. Use of comparative assessment questions gives nurses insight into patients’ perceptions and reactions to different aspects of the health care system and facilitates evaluation of patient outcomes.

Culturally Congruent Care

To provide culturally congruent care it is important to identify potential conflicts between patients’ health care needs and their health care practices and cultural values. Leininger (2006) identified three nursing decision and action modes to achieve culturally congruent care. All three modes of professional decisions and actions assist, support, facilitate, or enable people of particular cultures.

1. Cultural care preservation or maintenance—Retain and/or preserve relevant care values so patients maintain their well-being, recover from illness, or face handicaps and/or death.

2. Cultural care accommodation or negotiation—Adapt or negotiate with others for a beneficial or satisfying health outcome.

3. Cultural care repatterning or restructuring—Reorder, change, or greatly modify patients’ lifestyles for a new, different, and beneficial health care pattern.

Nurses are able to use any or all of these action modes simultaneously. These actions require that nurses have knowledge of patients’ culture and the willingness, commitment, and skills to work with patients and families in decision making. The intended outcome of these actions and decisions is meaningful, supportive, and facilitative care as judged by the patient.

Key Points

• Culture is the context for interpreting human experiences such as health and illness and provides direction to decisions and actions.

• Culturally congruent care is meaningful, supportive, and facilitative because it fits valued life patterns of patients.

• Nurses achieve culturally congruent care through cultural assessment and the application of cultural preservation, accommodation, and repatterning.

• Culturally competent care requires knowledge, attitudes, and skills supportive of implementation of culturally congruent care.

• Cultural assessment requires a comprehensive and thorough investigation of a patient’s cultural values, beliefs, and practices.

• Transcultural nursing is a comparative study and understanding of cultures to identify specific and universal caring constructs across cultures.

• Impression management facilitates culturally congruent communication and intercultural relationships.

Clinical Application QUESTIONS

Preparing for Clinical Practice

A 43-year-old male patient, who is an Orthodox Jew, is hospitalized following a motor vehicle accident. The nurse caring for the patient notes that he has not touched most of the food on his plate and has only eaten his bread and fruit. In reviewing the patient’s intake over the past 2 days, the nurse notes that this patient has eaten very little. The nurse reviews the patient’s diet order and finds that his diet orders indicate that he is to receive no pork products. The patient was served meatloaf, macaroni and cheese, green beans, a dinner roll, and a fresh peach for lunch. For dinner he was served lasagna, breadsticks, a salad, and a pear for dessert.

1. Explain possible causes for the patient’s poor appetite.

2. Identify nursing interventions to help increase the patient’s food intake.

3. Of the three nursing decisions and action modes described by Leininger (2006), explain which one is the most appropriate for this patient.

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. A 6-month-old child from Guatemala was adopted by an American family in Indiana. The child’s socialization into the American midwestern culture is best described as:

2. A 46-year-old woman from Bosnia came to the United States 6 years ago. Although she did not celebrate Christmas when she lived in Bosnia, she celebrates Christmas with her family now. This woman has experienced assimilation into the culture of the United States because she:

2. Adapted to and adopted the American culture.

3. Had an extremely negative experience with the American culture.

4. Gave up part of her ethnic identity in favor of the American culture.

3. To enhance their cultural awareness, nursing students need to make an in-depth self-examination of their own:

1. Motivation and commitment to caring.

2. Social, cultural, and biophysical factors.

4. Which of the following is required in the delivery of culturally congruent care?

1. Learning about vast cultures

2. Motivation and commitment to caring

5. A registered nurse is admitting a patient of French heritage to the hospital. Which question asked by the nurse indicates that the nurse is stereotyping the patient?

1. “What are your dietary preferences?”

2. “What time do you typically go to bed?”

3. “Do you bathe and use deodorant more than one time a week?”

4. “Do you have any health issues that we should know about?”

6. When action is taken on one’s prejudices:

2. Delivery of culturally congruent care is ensured.

3. Effective intercultural communication develops.

4. Sufficient comparative knowledge of diverse groups is obtained.

7. A nursing student is doing a community health rotation in an inner-city public health department. The student investigates sociodemographic and health data of the people served by the health department, and detects disparities in health outcomes between the rich and poor. This is an example of a(n):

1. Illness attributed to natural and biological forces.

2. Creation of the student’s interpretation and descriptions of the data.

3. Influence of socioeconomic factors in morbidity and mortality.

4. Combination of naturalistic, religious, and supernatural modalities.

8. Culture strongly influences pain expression and need for pain medication. However, cultural pain is:

1. Not expressed verbally or physically.

2. Expressed only to others from a similar culture.

3. Usually more intense than physical pain.

4. Suffered by a patient whose valued way of life is disregarded by practitioners.

9. Which of the following best represents the dominant values in American society on individual autonomy and self-determination?

10. The nurse at an outpatient clinic asks a patient who is Chinese American with newly diagnosed hypertension if he is limiting his sodium intake as directed. The patient does not make eye contact with the nurse but nods his head. What should the nurse do next?

1. Ask the patient how much salt he is consuming each day

2. Discuss the health implications of sodium and hypertension

3. Remind the patient that many foods such as soy sauce contain “hidden” sodium

11. A female Jamaican immigrant has been late to her last two clinic visits, which in turn had to be rescheduled. The best action that the nurse could take to prevent the patient from being late to her next appointment is:

1. Give her a copy of the city bus schedule.

2. Call her the day before her appointment as a reminder to be on time.

3. Explore what has prevented her from being at the clinic in time for her appointment.

12. A nursing student is taking postoperative vital signs in the postanesthesia care unit. She knows that some ethnic groups are more prone to genetic disorders. Which of the following patients is most at risk for developing malignant hypertension?

13. A community health nurse is making a healthy baby visit to a new mother who recently emigrated to the United States from Ghana. When discussing contraceptives with the new mom, the mother states that she won’t have to worry about getting pregnant for the time being. The nurse understands that the mom most likely made this statement because:

1. She won’t resume sexual relations until her baby is weaned.

2. She is taking the medroxyprogesterone (Depo-Provera) shot.

14. During their clinical postconference meeting, several nursing students were discussing their patients with their instructor. One student from a middle-class family shared that her patient was homeless. This is an example of caring for a patient from a different:

15. When interviewing a Native American patient on admission to the hospital emergency department, which questions are appropriate for the nurse to ask? (Select all that apply.)

Answers:1. 4; 2. 2; 3. 4; 4. 4; 5. 3; 6. 1; 7. 3; 8. 4; 9. 2; 10. 1; 11. 3; 12. 3; 13. 1; 14. 2; 15. 1, 2, 3.

References

Baker, C. Globalization and the cultural safety of an immigrant Muslim community. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57(3):296. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04104.x].

Campinha-Bacote, J. The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services: a model of care. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13(3):181.

Dein, S. Race, culture and ethnicity in minority research: a critical discussion. J Cult Diversity. 2006;13(2):68.

Dysart-Gale, D. Clinicians and medical interpreters: negotiating culturally appropriate care for patients with limited English ability. Family Commun Health. 2007;30(3):237.

Edelstein, S. Food, cuisine and cultural competency for culinary, hospitality and healthcare professionals. Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett; 2011.

Fadiman, A. The spirit catches you and you fall down. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux; 1997.

Flaskerud, J. What do we need to know about the culture-bound syndromes? Iss Ment Health Nurs. 2009;30:406.

Foster, G. Disease etiologies in non-Western medical systems. Am Anthropol. 1976;78:773.

Giger, J, Davidhizar, R. Transcultural nursing: assessment and intervention, ed 5. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

Leininger, MM. Culture care theory: a major contribution to advance transcultural nursing knowledge and practices. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13(3):189.

Leininger, MM, McFarland, MR. Transcultural nursing: concepts, theories, research and practice, ed 3. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2002.

Leininger, MM. Culture care diversity and universality theory and evolution of the ethnonursing method. In Leininger MM, McFarland MR, eds.: Culture care diversity and universality: a worldwide theory of nursing, ed 2, Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett, 2006.

Lewis, JA. Jewish perspectives on pregnancy and childbearing. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2003;28(5):306.

Lobar, SL, et al. Cross-cultural beliefs, ceremonies, and rituals surrounding death of a loved one. Pediatr Nurs. 2006;32(1):44.

Maier-Lorentz, MM. Transcultural nursing: its importance in nursing practice. J Cult Diversity. 2008;15(1):37.

McFarland, MM, Eipperle, MK. Culture care theory: A proposed practice theory guide for nurse practitioners in primary care settings. Contemp Nurse. 2008;28:48. [1].

Meiner, SE. Gerontologic nursing, ed 4. St Louis: Mosby; 2011.

Office of Minority Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. A patient-centered guide to implementing language across services in healthcare organizations. http://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/Assets/pdf/Checked/HC-LSIG.pdf, 2005. [Accessed July 10, 2011].

Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities. About minority health. http://www.cdc.gov/omhd/AMH/AMH.htm, 2007. [Accessed July 10, 2011].

Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities. National standards on culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS). http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/assets/pdf/checked/executive.pdf, 2007. [Accessed July 10, 2011].

Purnell, LD, Paulanka, BJ. Transcultural healthcare: a culturally competent approach, ed 3. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 2008.

Srivastava, RH. The healthcare professional’s guide to clinical competence. Toronto: Elsevier; 2007.

The Joint Commission. Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient-and family-centered care: a roadmap for hospitals (monograph). http://www.jointcommission.org//PatientSafety/HLC, 2010. [accessed October 2, 2010].

US Census Bureau. State and county quick facts. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html, 2010. [Accessed July 10, 2011].

US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC: USDHHS; 2010.

United Pentecostal Church International. Our doctrinal foundation. http://www.upci.org/about-us/beliefs/21-about-us/beliefs/91, 2011. [Accessed July 10, 2011].

Van Gennep, A. The rites of passage. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (translated by Vizedom MB, Caffee GL); 1960.

Webber, P. Yes, Virginia, nursing does have laws. Nurs Sc Q. 2008;21(1):68.

Research References

Armer, J, Radina, M. Definition of health and health promotion behaviors. J Multicult Nurs Health. 2006;13(3):443.

Chan, CKL, Yau, MK. Death preparation among the ethnic Chinese well-elderly in Singapore: an exploratory study. OMEGA. 2009-2010;60(3):225.

Chin, YM, et al. Zuo yuezi practice among Malaysian Chinese women: traditional versus modernity. Br J Midwifery. 2010;18(3):170.

Cowan, DT, Norman, I. Cultural competence in nursing: new meanings. J Transcult Nurs. 2006;17(1):82.

Crockett, R, et al. Time orientation and health-related behaviour: measurement in general population samples. Psychol Health. 2009;24(3):333.

Helsel, D, et al. Chronic illness and Hmong Shamans. J Transcult Nurs. 2005;16(4):150.

Johnstone, MJ, Kanitsaki, O. Health care provider and consumer understanding of cultural safety and cultural competency in health care: an Australian study. J Cult Diversity. 2007;14(2):96.

Kulwicki, A, et al. Collaborative partnership for culture care: enhancing health services for the Arab community. J Transcult Nurs. 2005;11(1):31.

Lobar, SL, et al. Cross-cultural beliefs, ceremonies, and rituals surrounding death of a loved one. Pediatr Nurs. 2006;32(1):44.

Maputle, MS, Jali, MN. Dealing with diversity: incorporating cultural sensitivity into midwifery practice in the tertiary hospital of Capricorn district, Limpopo province. Curationis. 2006;29(4):61.

McLachlan, H, Waldenstrom, U. Childbirth experiences in Australia of women born in Turkey, Vietnam and Australia. Birth: Issues Perinatal Care. 2005;34(4):272.

Nelms, LW, Gorski, J. The role of the African traditional healer in women’s health. J Transcult Nurs. 2006;17(4):184.

Omeri, A, et al. Beyond asylum: implications for nursing and health care delivery for Afghan refugees in Australia. J Transcult Nurs. 2006;17(1):30.

Walker, RL, et al. Ethnic group differences in reasons for living and moderating role of cultural worldview. Cult Diversity Ethnic Minority Psychol. 2010;16(3):372. [DOI:10.1037/a0019720].