Spiritual Health

• Discuss the influence of spiritual practices on the health status of patients.

• Describe the relationship among faith, hope, and spiritual well-being.

• Compare and contrast the concepts of religion and spirituality.

• Perform an assessment of a patient’s spirituality.

• Explain the importance of establishing a caring relationship with patients to gain spiritual insight.

• Discuss nursing interventions designed to promote spiritual health.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

The word spirituality derives from the Latin word spiritus, which refers to breath or wind. The spirit gives life to a person. It signifies whatever is at the center of all aspects of a person’s life (Smith, 2008). Florence Nightingale believed that spirituality was a force that provided energy needed to promote a healthy hospital environment and that caring for a person’s spiritual needs was just as essential as caring for his or her physical needs (Dolamo, 2010). Today spirituality is often defined as an awareness of one’s inner self and a sense of connection to a higher being, nature, or some purpose greater than oneself (Smith, 2008; Vachon, Fillion, and Achille, 2009). A person’s health depends on a balance of physical, psychological, sociological, cultural, developmental, and spiritual factors. Spirituality is important in helping individuals achieve the balance needed to maintain health and well-being and cope with illness. Research shows that spirituality positively affects and enhances health, quality of life, health promotion behaviors, and disease prevention activities (Jurkowski, Kurlanska, and Ramos, 2010; Lee, 2009).

Too often nurses and other health care providers fail to recognize the spiritual dimension of their patients because spirituality is not scientific enough, it has many definitions, and it is difficult to measure. In addition, some nurses and health care providers do not believe in God or an ultimate being, some are not comfortable with discussing the topic, and others claim that they do not have time to address spiritual needs (Tanyi, McKenzie, and Chapek, 2009). The concepts of spirituality and religion are often interchanged, but spirituality is a much broader and more unifying concept than religion (Vachon, Fillion, and Achille, 2009).

The human spirit is powerful, and spirituality has different meanings for different people (Pesut et al., 2008). Therefore nurses need to be aware of their own spirituality to provide appropriate and relevant spiritual care to others. They need to care for the whole person and accept a patient’s beliefs and experiences when providing spiritual care (Ellis and Narayanasamy, 2009; Mueller, 2010). Being able to determine the importance that spirituality holds for patients depends on a nurse’s ability to develop a caring relationship (see Chapter 7). Nursing care involves helping patients use their spiritual resources as they identify and explore what is meaningful in their lives and find ways to cope with the impact of illness and the ongoing stressors of life.

Scientific Knowledge Base

The relationship between spirituality and healing is not completely understood. However, the individual’s intrinsic spirit seems to be an important factor in healing. Healing often takes place because of believing. Current evidence shows a link between mind, body, and spirit. An individual’s beliefs and expectations often have effects on his or her physical and psychological well-being (Burris et al., 2009). Many of these effects are tied to hormonal and neurological function. For example, relaxation exercises and guided imagery improve immune function in certain situations (Lahmann et al., 2010; Weigensberg et al., 2009) and reduce perceptions of pain and anxiety (Casida and Lemanski, 2010). Laughter raises pain thresholds, boosts the immune system, reduces stress and anxiety, relieves tension, and elevates mood (Harkins 2009; Swetz et al., 2009). A person’s inner beliefs and convictions are powerful resources for healing. Nurses who support the spirituality of patients and their families are successful in helping patients achieve desirable health outcomes.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Nursing research shows the association between spirituality and health. For example, Pierce et al. (2008) found that caregivers used spirituality to cope with the daily aspects of providing care to family members who have had strokes. Hollywell and Walker (2009) found that prayer often helps those who attend church or who are older, female, or less educated cope with chronic illnesses and maintain feelings of well-being. The increased interest in studying the relationship between spirituality and health has greatly contributed to nursing science.

Current Concepts in Spiritual Health

A variety of concepts describe spiritual health. To provide meaningful and supportive spiritual care, it is important to understand the concepts of spirituality, spiritual well-being, faith, religion, and hope. Each concept offers direction in understanding the views that individuals have of life and its value.

Spirituality

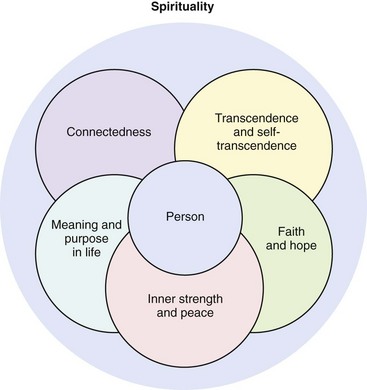

Spirituality is a complex concept that is unique to each individual; it depends on a person’s culture, development, life experiences, beliefs, and ideas about life (McSherry, 2007). Furthermore, spirituality is an inherent human characteristic that exists in all people, regardless of their religious beliefs. It gives individuals the energy needed to discover themselves, cope with difficult situations, and maintain health (Villagomeza, 2006). Energy generated by spirituality helps patients feel well and guides choices made throughout life. Spirituality enables a person to love, have faith and hope, seek meaning in life, and nurture relationships with others. Because it is subjective, multidimensional, and personal, researchers and scholars cannot agree on a universal definition of spirituality (Tanyi, McKenzie, and Chapek, 2009). However, five distinct but overlapping constructs are frequently found in definitions of spirituality (Fig. 35-1).

Self-transcendence is a sense of authentically connecting to one’s inner self (Vachon, Fillion, and Achille, 2009), whereas transcendence is the belief that a force outside of and greater than the person exists beyond the material world (Bailey et al., 2009). Individuals usually see this force as positive, and it allows people to have new experiences and develop new perspectives that are beyond ordinary physical boundaries. Examples of transcendent moments include the feeling of awe when holding a new baby or looking at a beautiful sunset. Spirituality offers a sense of connectedness intrapersonally (connected within oneself), interpersonally (connected with others and the environment), and transpersonally (connected with the unseen, God, or a higher power). Through connectedness patients are able to move beyond the stressors of everyday life and find comfort, faith, hope, peace, and empowerment (Nelson-Becker, Nakashima, and Canda, 2007). Faith allows people to have firm beliefs despite lack of physical evidence. It enables them to believe in and establish transpersonal connections. Although many people associate faith with religious beliefs, it exists without religious beliefs (Villagomeza, 2006). Hope has several meanings that vary on the basis of how it is being experienced; it usually refers to an energizing source that has an orientation to future goals and outcomes (Phillips-Salimi et al., 2007; Vachon, Fillion, and Achille, 2009).

Spirituality gives people the ability to find a dynamic and creative sense of inner strength that is often used when making difficult decisions. Inner strength is a source of energy that instills hope, provides motivation, and promotes a positive outlook on life (Lundman et al., 2010). Inner peace fosters calm, positive, and peaceful feelings despite life experiences of chaos, fear, and uncertainty. These feelings help people feel comforted even in times of great distress (Hanson et al., 2008). Spirituality also helps people find meaning and purpose in life in both positive and negative life events (Bailey et al., 2009; Vachon, Fillion, and Achille, 2009).

Some people do not believe in the existence of God (atheist) or they believe that there is no known ultimate reality (agnostic). This does not mean that spirituality is not an important concept for the atheist or agnostic (Smith-Stoner, 2007). Atheists search for meaning in life through their work and their relationships with others. Agnostics discover meaning in what they do or how they live because they find no ultimate meaning for the way things are. They believe that people bring meaning to what they do.

Spirituality is an integrating theme. A person’s concept of spirituality begins in childhood and continues to grow throughout adulthood (Narayanasamy et al., 2004; Smith and McSherry, 2004). It represents the totality of one’s being, serving as the overriding perspective that unifies the various aspects of an individual. It spreads through all dimensions of a person’s life, whether or not the person acknowledges or develops it.

Spiritual Well-Being

The concept of spiritual well-being is often described as having two dimensions. The vertical dimension supports the transcendent relationship between a person and God or some other higher power. The horizontal dimension describes positive relationships and connections that people have with others (Gray, 2006; Smith, 2006). Spiritual well-being has a positive effect on health. Those who experience spiritual well-being feel connected to others and are able to find meaning or purpose in their lives. Spiritual well-being leads to spiritual health. Those who are spiritually healthy experience joy, are able to forgive themselves and others, accept hardship and mortality, report an enhanced quality of life, and have a positive sense of physical and emotional well-being (Whelan-Gales et al., 2009; Yampolsky et al., 2008).

Faith

In addition to being a part of the definition of spirituality, the concept of faith has other common definitions. Faith is a cultural or institutional religion such as Judaism, Buddhism, Islam, or Christianity. It is also a relationship with a divinity, higher power, authority, or spirit that incorporates a reasoning faith (belief) and a trusting faith (action). Reasoning faith provides confidence in something for which there is no proof. It is an acceptance of what reasoning cannot explain. Sometimes faith involves a belief in a higher power, spirit guide, God, or Allah. Faith is also the manner in which a person chooses to live. It gives purpose and meaning to an individual’s life, allowing for action. Many times patients who are ill have a positive outlook on life and continue to pursue daily activities rather than resign themselves to the symptoms of the disease. Their faith often becomes stronger because they view their illness as an opportunity for personal growth (Alcorn et al., 2010; Ford et al., 2010).

Religion

Religion is associated with the “state of doing,” or a specific system of practices associated with a particular denomination, sect, or form of worship. Religion refers to the system of organized beliefs and worship that a person practices to outwardly express spirituality. Many people practice a faith or belief in the doctrines and expressions of a specific religion or sect such as the Lutheran church or Orthodox Judaism. People from different religions view spirituality differently. For example, a Buddhist believes in Four Noble Truths: life is suffering; suffering is caused by clinging; suffering can be eliminated by eliminating clinging; and to eliminate clinging and suffering, one follows an eightfold path. The path includes right understanding, intention, speech, action, livelihood, effort, mindfulness, and concentration. It promotes wisdom, moral behavior, and meditation (Wilkins, Mailoo, and Kularatne, 2010). A Buddhist turns inward, valuing self-control, whereas a Christian looks to the love of God to provide enlightenment and direction in life.

When providing spiritual care to a patient, it is important to understand the differences between religion and spirituality. Many people tend to use the terms spirituality and religion interchangeably. Although closely associated, these terms are not synonymous. Religious practices encompass spirituality, but spirituality does not need to include religious practice. Religious care helps patients maintain their faithfulness to their belief systems and worship practices. Spiritual care helps people identify meaning and purpose in life, look beyond the present, and maintain personal relationships and a relationship with a higher being or life force.

Hope

Spirituality and faith bring hope. When a person has the attitude of something to live for and look forward to, hope is present. It is a multidimensional concept that provides comfort while people endure life-threatening situations, hardships, and other personal challenges. It is closely associated with faith and is energizing, giving individuals a motivation to achieve and the resources to use toward that achievement. People express hope in all aspects of their lives to help them deal with life stressors. Hope is a valuable personal resource whenever someone is facing a loss (see Chapter 36) or a difficult challenge (Duggleby, Cooper, and Penz, 2009).

Spiritual Health

People gain spiritual health by finding a balance between their values, goals, and beliefs and their relationships within themselves and others. Throughout life a person often grows more spiritual, becoming increasingly aware of the meaning, purpose, and values of life. In times of stress, illness, loss, or recovery, a person often uses previous ways of responding or adjusting to a situation. Often these coping styles lie within the person’s spiritual beliefs.

Spiritual beliefs change as patients grow and develop. Spirituality begins as children learn about themselves and their relationships with others. Nurses who understand a child’s spiritual beliefs are able to care for and comfort the child (Mueller, 2010). As children mature into adulthood, they experience spiritual growth by entering into lifelong relationships. An ability to care meaningfully for others and self is evidence of a healthy spirituality.

Beliefs among older people vary based on many factors such as gender, past experience, religion, economic status, and ethnic background. Healthy spirituality in older adults is one that gives peace and acceptance of the self. It is often based on a lifelong relationship with a Supreme Being. Illness and loss sometimes threaten and challenge the spiritual developmental process. Older adults often express their spirituality by turning to important relationships and giving of themselves to others (Edelman and Mandle, 2010).

Factors Influencing Spirituality

When illness, loss, grief, or a major life change occurs, either people use spiritual resources to help them cope or spiritual needs and concerns develop. Spiritual distress is the “impaired ability to experience and integrate meaning and purpose in life through connectedness with self, others, art, music, literature, nature, and/or a power greater than oneself” (NANDA International, 2011). Spiritual distress causes a person to feel doubt, loss of faith, and a sense of being alone or abandoned. Individuals often question their spiritual values, raising questions about their way of life, purpose for living, and source of meaning. Spiritual distress also occurs when there is conflict between a person’s beliefs and prescribed health regimens or the inability to practice usual rituals.

Acute Illness

Sudden, unexpected illness frequently creates significant spiritual distress. For example, both the 50-year-old patient who has a heart attack and the 20-year-old patient who is in a motor vehicle accident face crises that threaten their spiritual health. The illness or injury creates an unanticipated scramble to integrate and cope with new realities (e.g., disability). People often look for ways to remain faithful to their beliefs and value systems. Some pray, attend religious services more often, or spend time reflecting on the positive aspects of their lives. Often conflicts develop around a person’s beliefs and the meaning of life. Anger is common; and patients sometimes express it against God, their families, themselves, or the nurse. The strength of a patient’s spirituality influences how he or she copes with sudden illness and how quickly he or she moves to recovery. Nurses use knowledge of a person’s spiritual well-being and implement spiritual interventions to maximize inner peace and healing (Yeager et al., 2010).

Chronic Illness

Many chronic illnesses threaten the person’s independence, causing fear, anxiety, and spiritual distress. Dependence on others for routine self-care needs often creates feelings of powerlessness. Powerlessness and the loss of a sense of purpose in life impair the ability to cope with alterations in functioning. Spirituality significantly helps patients and their family caregivers adapt to the changes that result from chronic illness (Box 35-1). Successful adaptation often provides spiritual growth. Patients who have a sense of spiritual well-being, feel connected with a higher power and others, and are able to find meaning and purpose in life are better able to cope with and accept their chronic illness (Daaleman and Dobbs, 2010; Ebadi et al., 2009).

Terminal Illness

Terminal illness commonly causes fears of physical pain, isolation, the unknown, and dying. It creates an uncertainty about what death means, making patients susceptible to spiritual distress. However, some patients have a spiritual sense of peace that enables them to face death without fear. Spirituality helps these patients find peace in themselves and their death. Individuals experiencing a terminal illness often find themselves reviewing their life and questioning its meaning. Common questions they ask include “Why is this happening to me?” or “What have I done?” Terminal illness often affects family and friends just as much as the patient. It causes members of the family to ask important questions about its meaning and how it will affect their relationship with the patient (see Chapter 36). In addition to managing patients’ physical and psychosocial symptoms experienced at the end of life, empower them to have a greater sense of control over their disease, regardless of whether they receive care in a hospital or at home. Providing holistic care is essential because dying is a part of life that encompasses the patient’s physical, social, psychological, and spiritual health (Wasserman, 2008).

Near-Death Experience

Some nurses care for patients who have had a near-death experience (NDE). An NDE is a psychological phenomenon of people who either have been close to clinical death or have recovered after being declared dead. It is not associated with a mental disorder. Persons who experience an NDE often tell the same story of feeling themselves rising above their bodies and watching caregivers initiate lifesaving measures. Most individuals describe passing through a tunnel to a bright light, encountering people who had preceded them in death, and feeling an inner tranquility and peace. Instead of moving toward the light, they learn that it is not time for them to die, and they return to life (Rominger, 2010).

Patients who have an NDE are often reluctant to discuss it, thinking that others will not understand. However, individuals experiencing an NDE who discuss it with family or caregivers find acceptance and meaning from this powerful experience. They are often no longer afraid of death. After a patient has survived an NDE, it is important to remain open and give him or her a chance to explore what happened. Provide support if the patient decides to share the experience with significant others (Duffy, 2007).

Critical Thinking

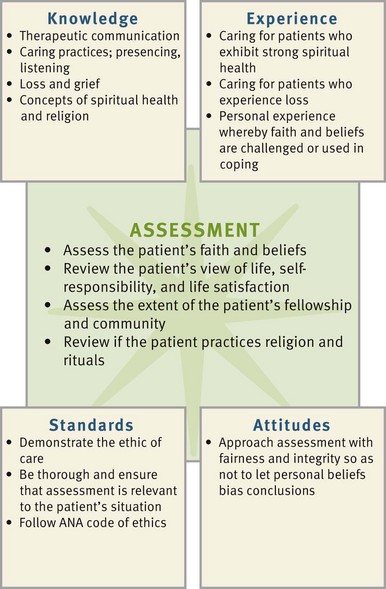

The helping role is important in nursing practice (Benner, 1984). Patients look to nurses for help that is different than the help they seek from other health care professionals. Expert nurses acquire the ability to anticipate personal issues affecting patients and their spiritual well-being. Critical thinking, knowledge, and skills help nurses enhance patients’ spiritual well-being and health. While using the nursing process, apply knowledge, experience, attitudes, and standards in providing appropriate spiritual care (Fig. 35-2). Nurses who are comfortable with their own spirituality often are more likely to care for their patients’ spiritual needs. Nurses who foster their own personal, emotional, and spiritual health become resources for their patients and use their own spirituality as a tool when caring for themselves and their patients (Chism and Magnan, 2009; Ellis and Narayanasamy, 2009).

FIG. 35-2 Critical thinking model for spiritual health assessment. ANA, American Nurses Association.

Taking a faith history reveals patient’s beliefs about life, health, and a Supreme Being. Knowing patients’ cultural preferences provides additional insight into their spiritual practices. Applying knowledge of spiritual concepts, principles of caring (see Chapter 7), and therapeutic communication skills (see Chapter 24) helps nurses readily recognize and understand patients’ spiritual needs. Convey caring and openness to successfully promote honest discussion about patients’ spiritual beliefs.

A sound understanding of ethics and values (see Chapter 22) is essential when providing spiritual care. A person’s values or beliefs about the worth of a given idea, attitude, or custom are linked to his or her spiritual well-being. Application of ethical principles ensures respect for a patient’s spiritual and religious convictions.

Personal experience in caring for patients in spiritual distress is valuable when helping patients select coping options. You need to determine if your spirituality is beneficial in assisting patients. Nurses who sense a personal faith and hope regarding life are usually better able to help their patients. Previous personal and professional experiences with dying patients, patients with chronic disease, or those who have experienced significant losses provide lessons in how to help patients face difficult challenges and how to offer support to family and friends.

Because each person has a unique spirituality, you need to know your own beliefs so you are able to care for each patient without bias (Tiew and Creedy, 2010). Use critical thinking when assessing each patient’s reaction to illness and loss and when determining if spiritual intervention is necessary. Humility is essential, especially when caring for patients from diverse cultural and/or religious backgrounds. Recognize personal limitations in knowledge about patients’ spiritual beliefs and religious practices. Effective nurses show genuine concern as they assess their patients’ beliefs and determine how spirituality influences their patients’ health. You demonstrate integrity by refraining from voicing your opinions about religion or spirituality when your beliefs conflict with those of your patients.

The application of intellectual standards helps you make accurate clinical decisions and helps patients find meaningful and logical ways to acquire spiritual healing. Critical thinking ensures that you obtain significant and relevant information when making decisions about patients’ spiritual needs. The nature of a person’s spirituality is complex and highly individualized. Therefore avoid making assumptions about his or her religion and beliefs. Significance and relevance are standards of critical thinking that ensure that you explore the issues that are most meaningful to patients and most likely to affect spiritual well-being.

In setting standards for quality health care, The Joint Commission (2010) requires health care organizations to assess patients’ denomination, beliefs, and spiritual practices and acknowledge their rights to spiritual care. Health care organizations also need to provide for patients’ spiritual needs through pastoral care or others who are certified, ordained, or lay individuals.

The American Nurses Association Code of Ethics for Nurses (Fowler, 2010) requires nurses to practice nursing with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and uniqueness of each patient despite socioeconomic status, personal characteristics, or type of health problem. It is essential to promote an environment that respects patients’ values, customs, and spiritual beliefs. Routinely implementing nursing interventions such as prayer or meditation is coercive and/or unethical. Therefore determine which interventions are compatible with the patient’s beliefs and values before selecting them. An ethic of caring (see Chapter 22) provides a framework for decision making and places the nurse as the patient’s advocate.

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to use to develop and implement an individualized plan of care. The core of nursing includes a commitment to caring and respect for an individual’s uniqueness. Application of the nursing process from the perspective of a patient’s spiritual needs is not simple. It goes beyond assessing his or her religious practices. Understanding a patient’s spirituality and then appropriately identifying the level of support and resources needed require a compassionate perspective. Remove any personal biases or misconceptions from patient assessments and be willing to share and discover another person’s meaning and purpose in life, illness, and health. Love, trust, hope, forgiveness, meaning, and community are universal spiritual needs. Learning to share these needs helps you find a way to give patients spiritual care and support. Patients bring certain spiritual resources that help them assume healthier lives, recover from illness, or face impending death. Supporting and recognizing the positive side of a patient’s spirituality goes a long way toward delivering effective, individualized nursing care.

Assessment

During the assessment process thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care. Because spirituality is deeply subjective, it means different things to different people (Bailey et al., 2009).

Through the Patient’s Eyes

It is essential to take the time to assess the patient’s viewpoints and establish a trusting relationship with him or her. Focus nursing assessment on aspects of spirituality that life experiences and events most likely influence. As you and your patients reach a point of learning together, spiritual caring occurs.

Spiritual assessment is therapeutic because it expresses a level of caring and support. It is also a fundamental part of the nursing assessment. Because completing a spiritual assessment takes time, conduct an ongoing assessment over the course of the patient’s stay in the health care setting if possible. Establish trust and rapport and make the opportunity to conduct meaningful discussions with patients a priority.

You can assess a patient’s spiritual health in several different ways. One way is to ask direct questions (Box 35-2). This approach requires you to feel comfortable asking others about their spirituality. Several assessment tools are available to help nurses clarify values and assess spirituality. For example, the spiritual well-being (SWB) scale has 20 items that assess the individual’s view of life and relationship with a higher power (Gray, 2006). The B-E-L-I-E-F assessment tool helps nurses evaluate a child’s and family’s spiritual and religious needs (McEvoy, 2003). The acronym stands for the following:

Effective spiritual assessment tools such as the SWB and B-E-L-I-E-F help nurses remember important areas to assess. A patient’s response to items on assessment tools often indicates areas that need further investigation. For example, if after using an assessment tool, a nurse finds that a patient has difficulty accepting change, the nurse needs to spend time understanding how the patient is accepting and managing the new illness. Whether you use an assessment tool or direct an assessment with questions that are based on principles of spirituality, it is important not to impose your personal value systems on the patient. This is particularly true when the patient’s values and beliefs are similar to those of your own because it then becomes very easy to make false assumptions. When nurses understand the overall approach to spiritual assessment, they are able to enter into thoughtful discussions with their patients, gain a greater awareness of the personal resources that patients bring to a situation, and incorporate the resources into an effective plan of care.

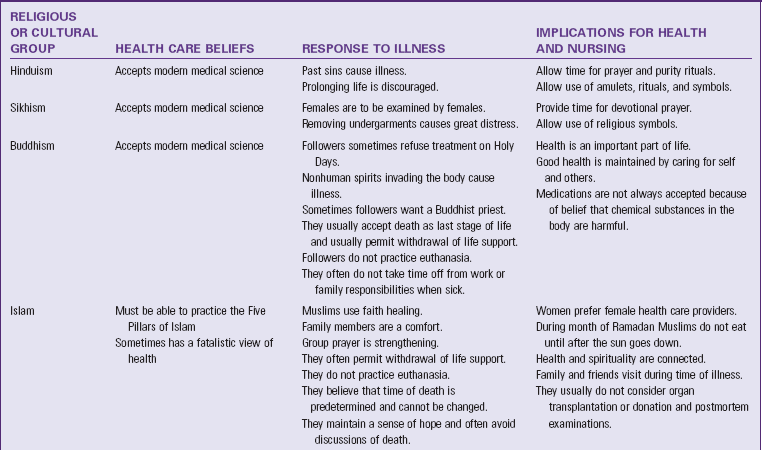

Faith/Belief

Assess the source of authority and guidance that patients use in life to choose and act on their beliefs. Determine if the patient has a religious source of guidance that conflicts with medical treatment plans and affects the option that nurses and other health care providers are able to offer patients. For example, if a patient is a Jehovah’s Witness, blood products are not an acceptable form of treatment. Christian Scientists often refuse any medical intervention, believing that their faith heals them. It is also important to understand a patient’s philosophy of life. Assessment data reveal the basis of the patient’s belief system regarding meaning and purpose in life and the patient’s spiritual focus. This information often reflects the impact that illness, loss, or disability has on the person’s life. Considerable religious diversity exists in the United States. A patient’s religious faith and practices, views about health, and the response to illness often influence how nurses provide support (Table 35-1).

Life and Self-Responsibility

Spiritual well-being includes life and self-responsibility. Individuals who accept change in life, make decisions about their lives, and are able to forgive others in times of difficulty have a higher level of spiritual well-being. During illness patients often are unable to accept limitations or do not know how to regain a functional and meaningful life. Their sense of helplessness reflects spiritual distress. However, patients often use their spiritual well-being as a resource as they adapt to changes and seek solutions to deal with limitations. Assess the extent to which a patient understands the limitations or threats posed by an illness and the manner in which he or she chooses to adjust to them.

Connectedness

People who are connected to themselves, others, nature, and God or another Supreme Being cope with the stress brought on by crisis and chronic illness. Patients remain connected with God by praying (Fig. 35-3). Prayer is personal communication with one’s god. It provides a sense of hope, strength, security, and well-being; and it is a part of faith (Hollywell and Walker, 2009; Krause and Bastida, 2009). Help patients become or remain connected by respecting each patient’s unique sense of spirituality. Assess whether the patient loses the ability to express a sense of relatedness to something greater than the self.

Life Satisfaction

Spiritual well-being is tied to a person’s satisfaction with life and what he or she has accomplished (Katerndahl, 2008). Assessing a person’s satisfaction with life often provides insight to appropriate nursing care. When people are satisfied with life, more energy is available to deal with new difficulties and resolve problems.

Culture

Spirituality is a personal experience within a cultural context. It is important to know a patient’s culture of origin and assess his or her values (Tiew and Creedy, 2010). It is common in many cultures for individuals to believe that they have led a worthwhile and purposeful life. Remaining connected with their cultural heritage often helps patients define their place in the world and express their spirituality. Asking them about their faith and belief systems is a good beginning for understanding the relationship between culture and spirituality (Box 35-3).

Fellowship and Community

Fellowship is a type of relationship that an individual has with other persons (e.g., family, close friends, fellow members of a church, or neighbors). Explore the extent and nature of the patient’s support networks. It is unwise to assume that a given network offers the kind of support that a patient desires. For example, calling the patient’s clergy to request a visit is inappropriate if the patient finds little fellowship with that individual.

Ritual and Practice

Assessing the use of rituals and practices helps nurses understand a patient’s spirituality. Rituals include participation in worship, prayer, sacraments (e.g., baptism, Holy Eucharist), fasting, singing, meditating, scripture reading, and making offerings or sacrifices. Different religions have different rituals for life events. For example, Buddhists practice baptism later in life and find burial or cremation acceptable at death. Muslims wash the body of a dead family member and wrap it in white cloth with the head turned toward the right shoulder. Orthodox and Conservative Jews circumcise their newborn sons 8 days after birth. Determine whether illness or hospitalization has interrupted a patient’s usual rituals or practices. A ritual often provides the patient with structure and support during difficult times. If rituals are important to the patient, use them as part of nursing intervention.

Vocation

Individuals express their spirituality on a daily basis in life routines, work, play, and relationships. Spirituality is often a part of a person’s identity and vocation in life. Determine if illness or hospitalization alters the ability to express some aspect of spirituality as it relates to the person’s work or daily activities. Expression of spirituality is highly individual and includes showing an appreciation for life in the variety of things people do, living in the moment and not worrying about tomorrow, appreciating nature, expressing love toward others, and being productive. When illness or loss prevents patients from expressing their spirituality, understand the psychological, social, and spiritual implications and provide appropriate guidance and support.

Nursing Diagnosis

A spiritual assessment allows a nurse to learn a great deal about the patient and the extent that spirituality plays in his or her life. Exploring the patient’s spirituality sometimes reveals responses to health problems that require nursing intervention or the existence of a strong set of resources that allow the patient to cope effectively. Analyze data to find patterns of defining characteristics and select appropriate nursing diagnoses (Box 35-4). In identifying diagnoses, recognize the significance that spirituality has for all types of health problems. Be sure that each diagnosis has an accurate related factor to guide the selection of individualized, purposeful, and goal-directed interventions. Potential nursing diagnoses for spiritual health include the following:

Three nursing diagnoses accepted by NANDA International (2011) pertain specifically to spirituality. Readiness for enhanced spiritual well-being is based on defining characteristics that show a person’s ability to experience and integrate meaning and purpose in life through connectedness with self and others. A patient with this nursing diagnosis has potential resources on which to draw when faced with illness or a threat to well-being. If the patient does not know how to engage personal resources to cope with health problems, offer support in exploring options.

The nursing diagnoses of spiritual distress and risk for spiritual distress create different clinical pictures. Defining characteristics from a nurse’s assessment reveal patterns that reflect a person’s actual or potential dispiritedness (e.g., expressing lack of hope, meaning, or purpose in life; anger toward God; or verbalizing conflicts about personal beliefs). Patients likely to be at risk for spiritual distress include those who have poor relationships, have experienced a recent loss, or are suffering some form of mental or physical illness.

Accurate selection of diagnoses requires critical thinking. Review all concrete data (e.g., religious rituals and sources of fellowship), your assessment of previous patient experiences, your own spirituality, and your appraisal of the patient’s spiritual well-being. Validate and clarify defining characteristics with the patient before making a diagnosis and plan of care. Commonly patients have multiple nursing diagnoses.

Planning

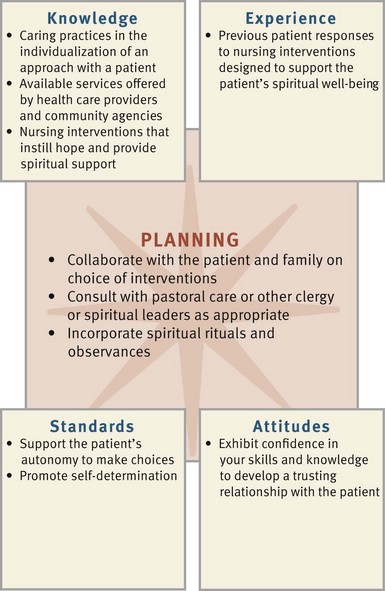

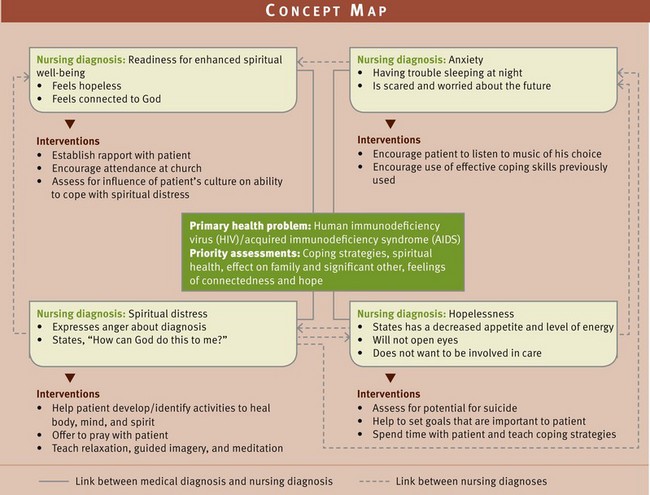

During the planning step of the nursing process, develop a plan of care for each of the patient’s nursing diagnoses. Critical thinking at this step is important because you reflect on previous experiences and apply knowledge and critical thinking attitudes and standards in selecting the most appropriate nursing interventions (Fig. 35-4). Prior experience with other patients is valuable when selecting interventions to support spiritual well-being. Integrate assessment data with knowledge about resources and therapies available for spiritual care to develop an individualized plan of care (see the Nursing Care Plan). Match the patient’s needs with evidence-based interventions that are supported and recommended in the clinical and research literature. Use a concept map (Fig. 35-5) to organize patient care and show how the patient’s medical diagnosis, assessment data, and nursing diagnoses are interrelated.

Confidence, an important critical thinking attitude, builds trust, enabling you and a patient to enter into a healing relationship together. Attempting to meet or support patients’ spiritual needs is not simple; frequently you need additional resources. For example, sometimes a nurse’s skills in helping patients interpret and understand the meaning of illness and loss are limited. Because spiritual care is so personal, standards of autonomy and self-determination are critical in supporting the patient’s decisions about the plan of care.

Goals and Outcomes

A spiritual care plan includes realistic and individualized goals along with relevant outcomes. It is important to collaborate closely with patients when setting goals and choosing related interventions. Setting realistic goals requires you to know a patient well. When spiritual care requires helping patients adjust to loss or stressful life situations, goals are long term. However, short-term outcomes such as renewing participation in religious practices help the patient progressively reach a more spiritually healthy situation. In establishing a plan of care, an example of a goal and associated outcomes follows:

The patient will improve personal harmony and connections with members of his or her support system.

Setting Priorities

Spiritual care is very personalized. Your relationship with a patient allows you to understand the patient’s priorities. When establishing a mutually agreed-on plan with the patient, he or she is able to identify what is most important. Spiritual priorities do not need to be sacrificed for physical care priorities. For example, when a patient is in acute distress, focus care to provide the patient a sense of control. When a patient is terminally ill, spiritual care often is the most important nursing intervention.

Teamwork and Collaboration

If the patient participates in a formal religion, involve members of the clergy or members of the church, temple, mosque, or synagogue in the plan of care. In a hospital setting the pastoral-care department is a valuable resource. These professionals provide insight about how and when to best support patients and their families. In addition, significant others such as spouses, siblings, parents, and friends need to be involved in the patient’s care as appropriate. This means that the nurse learns from the assessment which individuals or groups have formed a relationship with the patient. These individuals sometimes become involved in all levels of the nurse’s plan. They often assist in giving physical care, providing emotional comfort, and sharing spiritual support.

Implementation

Establish caring relationships with patients to discover their beliefs about the meaning of illness or loss and the effect they have on the meaning and purpose of life. Achieving this level of understanding with patients enables you to deliver care in a sensitive, creative, and appropriate manner.

Health Promotion

Spiritual care needs to be a central theme in promoting an individual’s overall well-being (Lopez et al., 2009). Spirituality is one personal resource that affects the balance between health and illness. In settings where health promotion activities occur, patients often need information, counseling, and guidance to make the necessary choices to remain healthy.

Establishing Presence: Nurses contribute to a sense of well-being and provide hope for recovery when they spend time with their patients (Tiew and Creedy, 2010). Behaviors that establish the nurse’s presence include paying attention, answering questions, listening, and having a positive and encouraging (but realistic) attitude. Establishing presence is part of the art of nursing. It is not simply being in the same room with a patient while performing procedures or sharing technical information with him or her. Presence involves “being with” a patient versus “doing for” a patient (Benner, 1984). It involves offering closeness with the patient physically, psychologically, and spiritually (see Chapter 7).

When health promotion is the focus of care, a nurse’s presence gives patients the confidence needed to remain healthy. Demonstrate a caring presence by listening to patients’ concerns and willingly involving family in discussions about the patients’ health. Show self-confidence when providing health instruction and support patients as they make decisions about their health. The patient who seeks health care is often fearful of experiencing an illness that threatens loss of control and looks for someone to offer competent direction. Encouraging words of support and a calm, decisive approach establish a presence that builds trust and well-being.

Supporting a Healing Relationship: Learn to look beyond isolated patient problems and recognize the broader picture of a patient’s holistic needs. For example, do not just look at a patient’s back pain as a problem to solve with quick remedies; rather look at how the pain influences the patient’s ability to function and achieve goals established in life. A holistic view enables you to establish a helping role and a healing relationship. Three factors are evident when a healing relationship develops between nurse and patient:

1. Mobilizing hope for the nurse and patient

2. Finding an interpretation or understanding of the illness, pain, anxiety, or other stressful emotion that is acceptable to the patient

3. Helping the patient use social, emotional, and spiritual resources (Benner, 1984)

Mobilizing the patient’s hope is central to a healing relationship. Hope motivates people with strategies to face challenges in life (Duggleby, Cooper, and Penz, 2009). Help patients find things for which to hope. For example, a patient newly diagnosed with diabetes wants to learn how to manage the disease to continue a productive and satisfying way of life. An adult daughter who has decided to become caregiver to her older adult parent hopes to be able to protect the parent from injury or worsening disability. Hope helps a patient work toward recovery. To help patients achieve hope, work together to find an explanation of the situation that is acceptable to the patient. Help the patient realistically exercise hope by supporting a positive attitude toward life or a desire to be informed and make decisions.

To further support a healing relationship, remain aware of the patient’s spiritual resources and needs. It is always important for patients to be able to express and exercise their beliefs and find spiritual comfort. When life stressors or illness create confusion or uncertainty, recognize the possible effect on a patient’s well-being. How does the nurse use and strengthen spiritual resources? Begin by encouraging a patient to discuss the effect that illness has had on personal beliefs and faith, thus giving the chance to clarify any misconceptions or inaccuracies in information. Having a clear sense of what illness will be like for an individual helps the person to apply all resources toward recovery.

Acute Care

Within acute care settings patients experience multiple stressors that threaten their sense of control. Ongoing assessment of spiritual needs is essential because the patient’s needs often change rapidly (Smith, 2006). Support and enhancement of a patient’s spiritual well-being are challenges when the focus of health care seems to be on treatment and cure rather than care (Tiew and Creedy, 2010). To overcome these challenges display a soothing presence and supportive touch when providing nursing care. The artful use of hands, encouraging words of support, promotion of connectedness, and a calm and decisive approach establish a presence that builds trust.

Support Systems: Use of support systems is important in any health care setting. They provide patients with the greatest sense of well-being during hospitalization and serve as a human link connecting the patient, the nurse, and the patient’s lifestyle before an illness. Part of the patient’s caregiving environment is the regular presence of supportive family and friends. Provide privacy during visits and plan care with the patient and the patient’s support network to promote the interpersonal bonding that is needed for recovery. The support system is a source of faith and hope and an important resource in conducting meaningful religious rituals.

When patients look to family and friends for support, encourage them to visit the patient regularly. Help family members feel comfortable in the health care setting and use their support and presence to promote the patient’s healing. For example, including family members in prayer is a thoughtful gesture if it is appropriate to the patient’s religion and if family members are comfortable participating. Having the family bring meaningful religious symbols to the patient’s bedside offers significant spiritual support.

Other important resources to patients are spiritual advisors and members of the clergy. Many hospitals have pastoral-care departments. Pastoral-care professionals have expertise in understanding how an illness influences a person’s beliefs and how the beliefs of the person influence illness and recovery. Ask if patients desire to have a member of the clergy visit during their hospitalization. When requested by patients or families, keep clergy informed of any physical, psychosocial, or spiritual concerns affecting the patient. Show respect for patients’ spiritual values and needs by allowing time for pastoral-care members to provide spiritual care and facilitating the administration of sacraments, rites, and rituals.

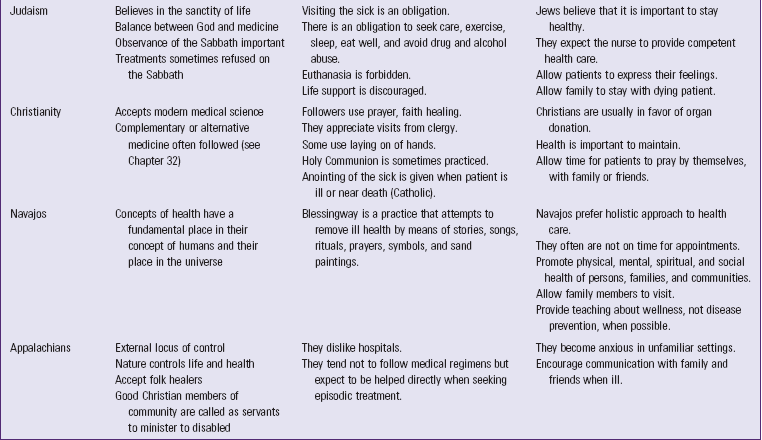

Diet Therapies: Food and nutrition are important aspects of patient care and often an important component of some religious observances (Table 35-2). Food and the rituals surrounding the preparation and serving of food are sometimes important to a person’s spirituality. Consult with a dietitian to integrate patients’ dietary preferences into daily care. In the event that a hospital or other health care agency cannot prepare food in the preferred way, ask the family to bring meals that fit into dietary restrictions posed by the patient’s condition.

TABLE 35-2

Religious Dietary Regulations Affecting Health Care

| RELIGION | DIETARY PRACTICES |

| Hinduism | Some sects are vegetarians. The belief is not to kill any living creature. |

| Buddhism | Some are vegetarians and do not use alcohol. Many fast on Holy Days. |

| Islam | Consumption of pork and alcohol is prohibited. Followers fast during the month of Ramadan. |

| Judaism | Some observe the kosher dietary restrictions (e.g., avoid pork and shellfish, do not prepare and eat milk and meat at the same time). |

| Christianity | Some Baptists, Evangelicals, and Pentecostals discourage the use of alcohol and caffeine. |

| Some Roman Catholics fast on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday. Some do not eat meat on Fridays during Lent. | |

| Jehovah’s Witnesses | Members avoid food prepared with or containing blood. |

| Mormonism | Members abstain from alcohol and caffeine. |

| Russian Orthodox Church | Followers observe fast days and a “no meat” rule on Wednesdays and Fridays. During Lent all animal products, including dairy products and butter, are forbidden. |

| Native Americans | Individual tribal beliefs influence food practices. |

Supporting Rituals: Nurses provide spiritual care by supporting patients’ participation in spiritual rituals and activities. Plan care to allow time for religious readings, spiritual visitations, or attendance at religious services. Allow family members to plan a prayer session or an organized reading of scriptures on a regular basis. Make arrangements with pastoral-care staff for the patient and family to participate in religious practices (e.g., receiving sacraments). Clergy often visit people who are unable to attend religious services. Taped meditations, classical or religious music, and televised religious services provide other effective options. The nurse respects icons, medals, prayer rugs, or crosses that patients bring to a health setting and ensures they are not accidentally lost, damaged, or misplaced. Supporting spiritual rituals is especially important for older adults (Box 35-5).

Restorative and Continuing Care

For patients who are recovering from a long-term illness or disability or who suffer chronic or terminal disease, spiritual care becomes especially important. Many of the nursing interventions applicable in health promotion and acute care apply to this level of health care as well.

Prayer: Prayer offers an opportunity to renew personal faith and belief in a higher being in a specific, focused way that is either highly ritualized and formal or quite spontaneous and informal. It is an effective coping resource for physical and psychological symptoms (Hollywell and Walker, 2009). Patients pray in private or pursue opportunities for group prayer with family, friends, or clergy. Nurses are supportive of prayer by giving patients privacy, suggesting prayer when they know that patients use it as a coping resource, and participating in prayer with patients. If prayer is not suitable for a patient, alternatives include listening to music or reading a book, poetry, or other inspirational texts selected by the patient.

Meditation: Meditation effectively creates a relaxation response that reduces daily stress. It reduces blood pressure, reduces stress and pain, and enhances the function of the immune system (Horowitz, 2009). Nurses often use guided imagery to help patients learn meditation (see Chapter 32). When patients use meditation in conjunction with their spiritual beliefs, they often report an increased spirituality that they commonly describe as experiencing the presence of a power, force, or energy or what was perceived as God (Box 35-6).

Supporting Grief Work: Patients who experience terminal illness or who have suffered permanent loss in body function because of a disabling disease or injury require the nurse’s support in grieving over and coping with their loss. Chapter 36 summarizes interventions to use in grief work. Your ability to enter into a therapeutic and spiritual relationship with patients supports them during times of grief.

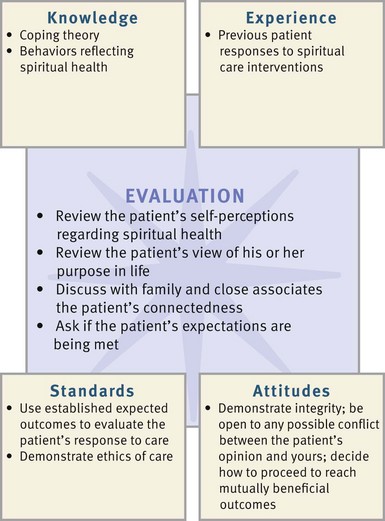

Evaluation

The evaluation of a patient’s spiritual care requires you to think critically in determining if efforts at restoring or maintaining the patient’s spiritual health were successful (Fig. 35-6). Include the patient in your evaluation of care. Outcomes established during the planning phase serve as the standards to evaluate the patient’s progress. Ask him or her if you and the health care team met their expectations and if there is anything else you can do to enhance their spiritual well-being. In addition, evaluate ethical concerns that arise in the course of the patient’s spiritual care and support. Apply critical thinking attitudes and use therapeutic communication techniques to ensure sound nursing judgments.

Patient Outcomes

Attaining spiritual health is a lifelong goal. In evaluating outcomes, compare the patient’s level of spiritual health with the behaviors and perceptions noted in the nursing assessment. Evaluation data related to spiritual health are usually subjective. For example, if a nurse’s assessment finds the patient losing hope, the follow-up evaluation involves asking the patient if feelings of hope have been restored. Include family and friends when gathering evaluative information. Successful outcomes reveal the patient developing an increased or restored sense of connectedness with family; maintaining, renewing, or reforming a sense of purpose in life; and for some a confidence and trust in a Supreme Being or power. When outcomes are not met, ask questions to determine appropriate continuing care. Examples of questions to ask include the following:

• Do you feel the need to forgive someone or to be forgiven by someone?

• What spiritual activities such as prayer or meditation were helpful in the past?

• Would you like for me to ask a friend, family member, or someone from pastoral care to talk with you?

• What can I do to help you feel more at peace?

• Sometimes people need to give themselves permission to feel hope when they experience difficult events. What can you do to allow yourself to feel hope again?

Key Points

• Attending to a patient’s spirituality ensures a holistic focus to nursing practice.

• Beneficial health outcomes occur when individuals are able to exercise their spiritual beliefs.

• Frequently spirituality and religion are interchanged, but spirituality is a much broader and more unifying concept than religion.

• Spirituality is highly personal and unique to each individual.

• Faith and hope are closely linked to a person’s spiritual well-being, providing an inner strength for dealing with illness and disability.

• When patients experience acute or chronic illness or a terminal disease, spiritual resources either help them move to recovery, or spiritual distress develops.

• A spiritual assessment is most successful when the nurse applies knowledge that is relevant to therapeutic communication, principles of loss and grief, and knowledge of caring practices.

• The personal nature of spirituality requires open communication and the establishment of trust between nurse and patient.

• Nurses need to determine if a patient’s religious beliefs conflict with medical treatment.

• An important part of spiritual assessment is learning who makes up the patient’s community of faith.

• Establishing presence involves giving attention, answering questions, having an encouraging attitude, and expressing a sense of trust.

• Connectedness and fellowship with other persons are a source of hope for a patient.

• Part of a patient’s caregiving environment is the regular presence of family, friends, and spiritual advisors.

• Prayer is an effective coping resource for physical and psychological symptoms.

• When evaluating spiritual care, successful outcomes reveal the patient developing an increased or restored sense of connectedness with family and maintaining, renewing, or reforming a sense of purpose in life.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

1. Jose continues to regularly visit the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) clinic. The nurse wants to incorporate a spiritual assessment with the physical assessment. During the assessment the nurse asks Jose if he has any questions. Jose asks her about a Buddhist ritual that he heard about from a friend. The nurse has not heard about that ritual before and states, “I’m not sure what you’re asking about. After we’re finished here, I’ll try to get some information for you.” In this interaction the nurse is exhibiting the attitude for critical thinking known as _________.

2. Jose’s mother comes with Jose to a clinic visit. During the visit the nurse asks Jose’s mother, “Which spiritual activities are part of your life?” Jose’s mother responds that she goes to daily Mass, listens to religious music, and spends time praying while she sits in her garden. When asked if there is anything the nurse can do for Jose’s mother, she responds that she would like to meet with a priest while she is visiting Jose. She then states, “My biggest concern is remaining strong for Jose. It is so hard to watch your child die.” Which nursing diagnosis is appropriate for Jose’s mother at this time?

3. Jose is too ill to come to the clinic. He now is being seen every other day by the hospice team. Jose’s family and his partner, Will, are at his side. Describe two nursing interventions the hospice nurse could implement to enhance the family’s connectedness.

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. An emergency department nurse is caring for a patient who was severely injured in a car accident. The patient’s family is in the waiting room. They are crying softly. The nurse sits down next to the family, takes the mother’s hand, and says, “I can only imagine how you’re feeling. What can I do to help you feel more at peace right now?” In this example the nurse is demonstrating:

2. A patient states that he does not believe in the existence of God. This patient most likely is an:

3. As the nurse cares for a patient in an outpatient clinic, the patient states that he recently lost his position as a volunteer coordinator at a local community center. He expresses that he is angry with his former boss and with God. The nurse knows that the priority at this time is to assess the patient’s spirituality in relation to his:

4. A patient who is hospitalized with heart failure states that she sees her illness as an opportunity and a challenge. Despite her illness, she is still able to see that life is worth living. This is an example of:

5. Which of the following statements made by an older adult whose husband recently died most indicates the need for follow-up by the nurse?

1. “I planted a tree at church in my husband’s honor.”

2. “I have been unable to talk with my children lately.”

3. “My friends think that I need to go to a grief support group.”

6. Which of the following nursing interventions support(s) a healing relationship with a patient? (Select all that apply):

2. Giving pain medications before a painful procedure

3. Telling a patient that it is time to take a bath before family arrive to visit

4. Making the patient’s bed following hospital protocol

5. Helping a patient see positive aspects related to a chronic illness

7. A patient expresses the desire to learn how to meditate. What does the nurse need to do first?

1. Answer the patient’s questions

2. Help the patient get into a comfortable position

3. Select a teaching environment that is free from distractions

4. Encourage the patient to meditate for 10 to 20 minutes 2 times a day

8. An older adult is receiving hospice care. Which nursing intervention(s) help the patient cope with feelings related to death and dying? (Select all that apply.)

1. Teaching the patient how to use guided imagery

2. Encouraging the family to visit the patient frequently

3. Taking the patient’s vital signs every time the nurse visits

4. Teaching the patient how to manage pain and take pain medications

5. Helping the patient put significant photographs in a scrapbook for the family

9. Which of the following questions would best assess a patient’s level of connectedness?

1. What gives your life meaning?

2. Which aspects of your spirituality would you like to discuss right now?

3. Who do you consider to be the most important person in your life at this time?

4. How do you feel about the accomplishments you’ve made in your life so far?

10. A nurse is using the B-E-L-I-E-F tool to complete a spiritual assessment on a 12-year-old male who has recently been diagnosed with acute lymphocytic leukemia. Which of the following questions would the nurse use to assess the child’s involvement in the spiritual community?

1. Which church do you attend?

2. Which sports do you like to play?

11. A nurse is caring for a patient who refuses to eat until after the sun sets. Which religion does this patient most likely practice?

12. A Catholic patient with diabetes receives the following items on his meal tray on the Friday before Easter. For which of the foods does the nurse offer to substitute?

13. A nurse is working in a health clinic on a Navajo reservation. He or she plans care for the patients knowing which of the following is true?

1. The patients may not be on time for their appointments.

2. The patients most likely do not trust the doctors and nurses.

3. The patients probably are not comfortable if they have to remove their undergarments.

4. Terminally ill patients probably want to receive the sacrament, the anointing of the sick.

14. A 62-year-old male patient has just been told he has a terminal illness. Which of the following statements supports a nursing diagnosis of spiritual distress related to diagnosis of terminal illness?

1. “I have nothing to live for now.”

2. “What will happen to my wife when I die?”

15. Which of the following would be the most appropriate outcome for a patient who has a nursing diagnosis of spiritual distress related to loneliness?

Answers: 1. 2; 2. 2; 3. 1; 4. 1; 5. 2; 6. 1, 5; 7. 3; 8. 1, 2, 5; 9. 3; 10. 4; 11. 1; 12. 3; 13. 1; 14. 1; 15. 2.

References

Alcorn, SR, et al. “If God wanted me yesterday, I wouldn’t be here today”: religious and spiritual themes in patients’ experiences of advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(5):581.

Benner, P. From novice to expert. Menlo Park, Calif: Addison-Wesley; 1984.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Chronic diseases and health promotion 2010. www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm [accessed August 21, 2011.].

Dolamo, BL. Spiritual nursing. Nurs Update. 2010;34(4):22.

Duffy, N. Supporting a patient after a near-death experience. Nursing. 2007;37(4):46.

Ebersole, P, et al. Toward healthy aging: human needs and nursing response, ed 7. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

Edelman, CL, Mandle, CL. Health promotion throughout the life span, ed 7. St Louis: Mosby; 2010.

Fowler, MDM. Guide to the code of ethics for nurses: interpretation and application. Silver Spring, Md: American Nurses Association; 2010.

Gray, J. Measuring spirituality: conceptual and methodological considerations. J Theory Construction Testing. 2006;10(2):58.

Horowitz, S. Health benefits of meditation: what the newest research shows. Altern Complement Ther. 2010;16(4):223.

Lundman, B, et al. Inner strength: a theoretical analysis of salutogenic concepts. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(2):251.

McEvoy, M. Culture and spirituality as an integrated concept in pediatric care. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2003;28(1):39.

McSherry, W. The meaning of spirituality and spiritual care within nursing and health care practice. London: Quay Books; 2007.

Mueller, CR. Spirituality in children: understanding and developing interventions. Pediatr Nurs. 2010;36(4):197.

NANDA International. NANDA-I nursing diagnoses: definitions and classification 2012-2014. Philadelphia: The Association; 2012.

Narayanasamy, A. Palliative care and spirituality. Indian J Palliat Care. 2007;13(2):32.

Nelson-Becker, H, Nakashima, M, Canda, ER. Spiritual assessment in aging: a framework for clinicians. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2007;48(3/4):331.

Pesut, B, et al. Conceptualising spirituality and religion for healthcare. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:2803.

Smith, AR. Using the synergy model to provide spiritual nursing care in critical care settings. Crit Care Nurse. 2006;26(4):41.

Smith, S. Toward a flexible framework for understanding spirituality. Occupational Ther Health Care. 2008;22(1):39.

Smith, J, McSherry, W. Spirituality and child development: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(3):307.

The Joint Commission (TJC), Standards FAQ details 2010. http://www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/jcfaqdetails.aspx?StandardsFaqId=290&ProgramId=1

Vachon, M, Fillion, L, Achille, M. A conceptual analysis of spirituality at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2009;21(1):53.

Wasserman, LS. Respectful death: a model for end-of-life care. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(4):621.

Wilkins, A, Mailoo, VJ, Kularatne, U. Care of the older person: a Buddhist perspective. Nurs Residential Care. 2010;12(6):295.

Yeager, S, et al. Embrace hope: an end-of-life intervention to support neurological critical care patients and their families. Crit Care Nurs. 2010;30(1):47.

Research References

Anderberg, P, Berglund, A. Elderly persons’ experiences of striving to receive care on their own terms in nursing homes. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16(1):64.

Bailey, ME, et al. Creating a spiritual tapestry: nurses’ experiences of delivering spiritual care to patients in an Irish hospice. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2009;15(9):42.

Burris, JL, et al. Factors associated with the psychological well-being and distress of university students. J Am Coll Health. 2009;57(5):536.

Campesino, M, et al. Spirituality and cultural identification among Latino and non-Latino college students. Hispanic Health Care Int. 2009;7(2):72.

Casida, J, Lemanski, SA. An evidence-based review on guided imagery utilization in adult cardiac surgery. Clin Scholars Rev. 2010;3(1):22.

Chism, LA, Magnan, MA. The relationship of nursing students’ spiritual care perspectives to their expressions of spiritual empathy. J Nurs Educ. 2009;48(11):597.

Choi, G, Tirrito, T, Mills, F. Caregiver’s spirituality and its influence on maintaining the elderly and disabled in a home environment. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2008;51(3-4):247.

Daaleman, TP, Dobbs, D. Religiosity, spirituality, and death attitudes in chronically ill older adults. Res Aging. 2010;32(2):224.

Duggleby, W, Cooper, D, Penz, K. Hope, self-efficacy, spiritual well-being and job satisfaction. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(11):2376.

Ebadi, A, et al. Spirituality: a key factor in coping among Iranians chronically affected by mustard gas in the disaster of war. Nurs Health Sci. 2009;11(4):344.

Elias, ACA, Giglio, JS, Pimenta, CAM. Analysis of the nature of spiritual pain in terminal patients and the process through the resignification relaxation, mental images and spirituality (RIME) intervention. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2008;16(6):959.

Ellis, HK, Narayanasamy, A. An investigation into the role of spirituality in nursing. Br J Nurs. 2009;18(14):886.

Ford, D, et al. Factors associated with illness perception among critically ill patients and surrogates. CHEST. 2010;138(1):59.

Gallia, KS, Pines, EW. Narrative identity and spirituality of African American churchwomen surviving breast cancer survivors. J Cult Diversity. 2009;16(2):50.

Hampton, MC, Halkitis, PN, Mattis, JS. Coping, drug use, and religiosity/spirituality in relation to HIV serostatus among gay and bisexual men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22(5):417.

Hanson, LC, et al. Providers and types of spiritual care during serious illness. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(6):907.

Harkins, LE. Literature analysis of humor therapy research. Am J Recreation Ther. 2009;8(4):35.

Herrera, AP, et al. Religious coping and caregiver well-being in Mexican-American families. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(1):84.

Hollywell, C, Walker, J. Private prayer as a suitable intervention for hospitalised patients: a critical review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(5):637.

Horowitz, S. Effect of positive emotions on health: hope and humor. Altern Complement Ther. 2009;15(4):196.

Jurkowski, JM, Kurlanska, C, Ramos, BM. Latino women’s spiritual beliefs related to health. Am J Health Promotion. 2010;25(1):19.

Katerndahl, DA. Impact of spiritual symptoms and their interactions on health services and life satisfaction. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(5):412.

Krause, N, Bastida, E. Core religious beliefs and providing support to others in late life. Ment Health Religion Cult. 2009;12(1):75.

Lahmann, C, et al. Effects of functional relaxation and guided imagery on IgE in dust-mite allergic adult asthmatics: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(2):125.

Lee, CJ. A comparison of health promotion behaviors in rural and urban community-dwelling spousal caregivers. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(5):34.

Lopez, AJ, et al. Spiritual well-being and practices among women with gynecologic cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36(3):300.

Narayanasamy, A, et al. Responses to the spiritual needs of older people. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48(1):6.

Phillips-Salimi, CR, et al. Psychometric properties of the Herth Hope Index in adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Nurs Measurement. 2007;15(1):3.

Pierce, LL, et al. Spirituality expressed by caregivers of stroke survivors. West J Nurs Res. 2008;30(5):606.

Rominger, R. Postcards from heaven and hell: understanding the near-death experience through art. Art Ther. 2010;27(1):18.

Roscoe, LA. Well-being of family caregivers of persons with late-stage Huntington’s disease: lessons in stress and coping. Health Commun. 2009;24(3):239.

Sanders, S, et al. The experience of high levels of grief in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia. Death Studies. 2008;32(6):495.

Smith-Stoner, M. End-of-life preferences for atheists. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(4):923.

Stranahan, S. A spiritual screening tool for older adults. J Relig Health. 2008;47:491.

Strudwick, A, Morris, R. A qualitative study exploring the experiences of African-Caribbean informal stroke carers in the UK. Clin Rehabil. 2010;24(2):159.

Swetz, KM, et al. Strategies for avoiding burnout in hospice and palliative medicine: peer advice for physicians on achieving longevity and fulfillment. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(9):773.

Tanyi, RA, McKenzie, M, Chapek, C. How family practice physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants incorporate spiritual care in practice. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21(12):690.

Tiew, LH, Creedy, DK. Integration of spirituality in nursing practice: a literature review. Singapore Nurs J. 2010;37(1):15.

Villagomeza, LR. Mending broken hearts: the role of spirituality in cardiac illness: a research synthesis, 1991-2004. Holist Nurs Pract. 2006;20(4):169.

Weigensberg, MJ, et al. Acute effects of stress-reduction interactive guided imagery (SM) on salivary cortisol in overweight Latino adolescents. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(3):297.

Whelan-Gales, MA, et al. Spiritual well-being, spiritual practices, and depressive symptoms among elderly patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. Geriatr Nurs. 2009;30(5):312.

Yampolsky, MA, et al. The role of spirituality in coping with visual impairments. J Vis Impair Blind. 2008;102(1):28.