Communication

• Describe aspects of critical thinking that are important to the communication process.

• Describe the five levels of communication and their uses in nursing.

• Describe the basic elements of the communication process.

• Identify significant features and therapeutic outcomes of nurse-patient helping relationships.

• Identify a nurse’s communication approaches within the four phases of a nurse-patient helping relationship.

• Identify significant features and desired outcomes of nurse–health care team member relationships.

• Describe qualities, behaviors, and communication techniques that affect professional communication.

• Discuss effective communication techniques for older patients.

• Identify patient health states that contribute to impaired communication.

• Discuss nursing care measures for patients with special communication needs.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Communication and Nursing Practice

Communication is a lifelong learning process. Nurses make the intimate journey with patients and their families from the miracle of birth to the mystery of death. As a nurse you communicate with patients and families to collect meaningful assessment data, provide education, and interact using therapeutic communication to promote personal growth and attainment of health-related goals. Despite the complexity of technology and the multiple demands on nurses’ time, it is the intimate moment of connection that makes all the difference in the quality of care and meaning for a patient and a nurse.

Communication is an essential part of patient-centered nursing care. Patient safety also requires effective communication among members of the health care team as patients move from one caregiver to another or from one care setting to another. Breakdown in communication among the health care team is a major cause of errors in the workplace and threatens professional credibility (World Health Organization, 2007). Effective team communication and collaboration skills are essential to ensure patient safety and high-quality patient care (Cronenwett et al., 2007). Competency in communication helps maintain effective relationships within the entire sphere of professional practice and meets legal, ethical, and clinical standards of care.

The qualities, behaviors, and therapeutic communication techniques described in this chapter characterize professionalism in helping relationships. Although the term patient is often used, the same principles apply when communicating with any person in any nursing situation.

Communication and Interpersonal Relationships

Caring relationships formed among a nurse and those affected by a nurse’s practice are at the core of nursing (see Chapter 7). Communication is the means of establishing these helping-healing relationships. All behavior communicates, and all communication influences behavior. For these reasons communication is essential to the nurse-patient relationship.

Nurses with expertise in communication express caring by the following (Watson, 1985):

• Becoming sensitive to self and others

• Promoting and accepting the expression of positive and negative feelings

• Developing helping-trust relationships

• Promoting interpersonal teaching and learning

• Providing a supportive environment

A nurse’s ability to relate to others is important for interpersonal communication. This includes the ability to take initiative in establishing and maintaining communication, to be authentic (one’s self), and to respond appropriately to the other person. Effective interpersonal communication also requires a sense of mutuality, a belief that the nurse-patient relationship is a partnership and that both are equal participants. Nurses honor the fact that people are very complex and ambiguous. Often more is communicated than first meets the eye, and patient responses are not always what you expect. By giving all of your attention to a patient, you attend to the patient’s needs and aid the healing process (Tavernier, 2006). Most nurses embrace the profession’s view of the holistic nature of people and experience synergy in human interaction. When patients and nurses work together, much can be accomplished.

Therapeutic communication occurs within a healing relationship between a nurse and patient (Arnold and Boggs, 2011). Like any powerful therapeutic agent, the nurse’s communication can result in both harm and good. Every nuance of posture, every small expression and gesture, every word chosen, every attitude held—all have the potential to hurt or heal, affecting others through the transmission of human energy. Knowing that intention and behavior directly influence health gives nurses tremendous ethical responsibility to do no harm to those entrusted to their care. Respect the potential power of communication and do not carelessly misuse communication to hurt, manipulate, or coerce others. Skilled communication empowers others and enables people to know themselves and make their own choices, an essential aspect of the healing process. Nurses have wonderful opportunities to bring about good things for themselves, their patients, and their colleagues through this kind of therapeutic communication.

Developing Communication Skills

Gaining expertise in communication requires both an understanding of the communication process and reflection about one’s communication experiences as a nurse. Nurses who develop critical thinking skills make the best communicators. They draw on theoretical knowledge about communication and integrate this knowledge with knowledge previously learned through personal experience. They interpret messages received from others, analyze their content, make inferences about their meaning, evaluate their effect, explain rationale for communication techniques used, and self-examine personal communication skills (Balzer-Riley, 2007).

Critical thinking in nursing, based on established standards of nursing care and ethical standards, promotes effective communication. When you consider a patient’s problems, it is important to apply critical thinking standards to ensure sound effective communication (Chitty, 2010). For example, curiosity motivates a nurse to communicate and know more about a person. Patients are more likely to communicate with nurses who express an interest in them. Perseverance and creativity are also attitudes conducive to communication because they motivate a nurse to communicate and identify innovative solutions. A self-confident attitude is important because a nurse who conveys confidence and comfort while communicating more readily establishes an interpersonal helping-trusting relationship. In addition, an independent attitude encourages a nurse to communicate with colleagues and share ideas about nursing interventions. Such an attitude often involves risk taking because colleagues sometimes question suggested nursing interventions. At the same time, an attitude of fairness goes a long way in the ability to listen to both sides in any discussion. Integrity allows nurses to recognize when their opinions conflict with those of their patients, review positions, and decide how to communicate to reach mutually beneficial decisions. It is also very important for a nurse to communicate responsibly and ask for help if uncertain or uncomfortable about an aspect of patient care. An attitude of humility is necessary to recognize and communicate the need for more information before making a decision (Paul, 1993).

It is challenging to understand human communication within interpersonal relationships. Each individual bases his or her perceptions about information received through the five senses of sight, hearing, taste, touch, and smell (Arnold and Boggs, 2011). An individual’s culture and education also influence perception. Critical thinking helps nurses overcome perceptual biases, or human tendencies that interfere with accurately perceiving and interpreting messages from others. People often assume that others think, feel, act, react, and behave as they would in similar circumstances. They tend to distort or ignore information that goes against their expectations, preconceptions, or stereotypes (Beebe et al., 2010). By thinking critically about personal communication habits, you learn to control these tendencies and become more effective in interpersonal relationships.

As communication skills develop, competence in the nursing process also grows. You need to integrate communication skills throughout the nursing process as you collaborate with patients and health care team members to achieve goals (Box 24-1). Use communication skills to gather, analyze, and transmit information and accomplish the work of each step of the process. Assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation all depend on effective communication among nurse, patient, family, and others on the health care team. Although the nursing process is a reliable framework for patient care, it does not work well unless you master the art of effective interpersonal communication.

The nature of the communication process requires you to constantly make decisions about what, when, where, why, and how to convey a message. A nurse’s decision making is always contextual (i.e., the unique features of any situation influence the nature of the decisions made). For example, the explanation of the importance of following a prescribed diet to a patient with a newly diagnosed medical condition differs from the explanation to a patient who has repeatedly chosen not to follow diet restrictions. Effective communication techniques are easy to learn, but their application is more difficult. Deciding which techniques best fit each unique nursing situation is challenging. Communication about specific diagnoses such as cancer or end of life and dealing with patient and family emotions can be challenging, and some nurses struggle to cope with their own reactions and emotions (Sheldon et al., 2006).

Throughout this chapter brief clinical examples guide you in the use of effective communication techniques. Situations that challenge a nurse’s decision-making skills and call for careful use of therapeutic techniques often involve the types of persons described in Box 24-2. Because the best way to acquire skill is through practice, it is useful for you to discuss and role-play these scenarios before experiencing them in the clinical setting. Consider who is involved in the situation to decide which communication will be most effective.

Levels of Communication

Nurses use different levels of communication in their professional role. A competent nurse uses a variety of techniques in each level.

Intrapersonal communication is a powerful form of communication that occurs within an individual. This level of communication is also called self-talk, self-verbalization, or inner thought. People’s thoughts strongly influence perceptions, feelings, behavior, and self-concept. You need to be aware of the nature and content of your own thinking. Self-talk provides a mental rehearsal for difficult tasks or situations so individuals deal with them more effectively and with increased confidence (Gibson and Foster, 2007; White, 2008). Nurses and patients use intrapersonal communication to develop self-awareness and a positive self-concept that enhances appropriate self-expression. For example, you improve your health and self-esteem through positive self-talk by replacing negative thoughts with positive assertions.

Interpersonal communication is one-on-one interaction between a nurse and another person that often occurs face to face. It is the level most frequently used in nursing situations and lies at the heart of nursing practice. It takes place within a social context and includes all the symbols and cues used to give and receive meaning. Because meaning resides in persons and not in words, messages received are sometimes different from intended messages. Nurses work with people who have different opinions, experiences, values, and belief systems; thus it is important to validate meaning or mutually negotiate it between participants. For example, use interaction to assess understanding and clarify misinterpretations when teaching a patient about a health concern. Meaningful interpersonal communication results in exchange of ideas, problem solving, expression of feelings, decision making, goal accomplishment, team building, and personal growth.

Transpersonal communication is interaction that occurs within a person’s spiritual domain. Study of the influence of religion and spirituality has increased dramatically in recent years, and ongoing research helps us understand the role of nurses in addressing a patient’s spiritual needs (Pesut et al., 2008). Many people use prayer, meditation, guided reflection, religious rituals, or other means to communicate with their “higher power.” Nurses have a responsibility to assess a patient’s spiritual needs and intervene to meet those needs (see Chapter 35).

Small-group communication is interaction that occurs when a small number of persons meet. This type of communication is usually goal directed and requires an understanding of group dynamics. When nurses work on committees, lead patient support groups, form research teams, or participate in patient care conferences, they use a small-group communication process. Small groups are most effective when they are cohesive and committed and have an appropriate meeting place with suitable seating arrangements (Arnold and Boggs, 2011). A nurse’s role varies with the function of a group. He or she frequently coordinates the group, provides recognition and acceptance of the contributions of each group member, and provides encouragement and motivation to help the group meet its goals (Townsend, 2009).

Public communication is interaction with an audience. Nurses have opportunities to speak with groups of consumers about health-related topics, present scholarly work to colleagues at conferences, or lead classroom discussions with peers or students. Public communication requires special adaptations in eye contact, gestures, voice inflection, and use of media materials to communicate messages effectively. Effective public communication increases audience knowledge about health-related topics, health issues, and other issues important to the nursing profession.

Basic Elements of the Communication Process

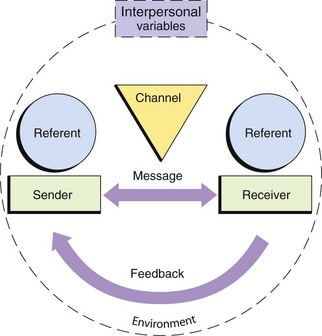

Communication is an ongoing, dynamic, and multidimensional process. Fig. 24-1 shows the basic elements of the communication process. This simple linear model represents a very complex process with its essential components. Nursing situations have many unique aspects that influence the nature of communication and interpersonal relationships. As a professional, you will use critical thinking to focus on each aspect of communication so your interactions are purposeful and effective.

Referent

The referent motivates one person to communicate with another. In a health care setting sights, sounds, odors, time schedules, messages, objects, emotions, sensations, perceptions, ideas, and other cues initiate communication. Knowing which stimulus initiates communication enables you to develop and organize messages more efficiently and better perceive meaning in another’s message. A patient request for help prompted by difficulty breathing brings a different nursing response than a request prompted by hunger.

Sender and Receiver

The sender is the person who encodes and delivers the message, and the receiver is the person who receives and decodes the message. The sender puts ideas or feelings into a form that is transmitted and is responsible for the accuracy of its content and emotional tone. The sender’s message acts as a referent for the receiver, who is responsible for attending to, translating, and responding to the sender’s message. Sender and receiver roles are fluid and change back and forth as two persons interact; sometimes sending and receiving occurs simultaneously. The more the sender and receiver have in common and the closer the relationship, the more likely they will accurately perceive one another’s meaning and respond accordingly.

Messages

The message is the content of the communication. It contains verbal, nonverbal, and symbolic language. Personal perceptions sometimes distort the receiver’s interpretation of the message. Two nurses can provide the same information yet convey very different messages because of their personal communication styles. Two persons understand the same message differently. You send effective messages by expressing clearly, directly, and in a manner familiar to the receiver. You determine the need for clarification by watching the listener for nonverbal cues that suggest confusion or misunderstanding. Communication is difficult when participants have different levels of education and experience. “Your incision is well approximated without purulent drainage” means the same as “Your wound edges are close together, and there are no signs of infection,” but the latter is easier to understand. You can also send messages in writing, but make sure that patients are able to read.

Channels

Channels are means of conveying and receiving messages through visual, auditory, and tactile senses. Facial expressions send visual messages, spoken words travel through auditory channels, and touch uses tactile channels. Individuals usually understand a message more clearly when the sender uses more channels to convey it. For example, when teaching about insulin self-injection, the nurse talks about and demonstrates the technique, gives the patient printed information, and encourages hands-on practice with the vial and syringe. Nurses use verbal, nonverbal, and mediated (technological) communication channels. They send and receive information in person, by informal or formal writing, over the telephone or pager, by audiotape and videotape, through fax and electronic mail, and through interactive and informational websites.

Feedback

Feedback is the message the receiver returns. It indicates whether the receiver understood the meaning of the sender’s message. Senders seek verbal and nonverbal feedback to evaluate the effectiveness of communication. The sender and receiver need to be sensitive and open to one another’s messages, clarify the messages, and modify behavior accordingly. In a social relationship both persons assume equal responsibility for seeking openness and clarification, but the nurse assumes primary responsibility in the nurse-patient relationship.

Interpersonal Variables

Interpersonal variables are factors within both the sender and receiver that influence communication. Perception is one such variable that provides a uniquely personal view of reality formed by an individual’s expectations and experiences. Each person senses, interprets, and understands events differently. A nurse says, “You have been very quiet since your family left. Is there something on your mind?” One patient may perceive the nurse’s question as caring and concerned; another perceives the nurse as invading privacy and is less willing to talk. Other interpersonal variables include educational and developmental levels, sociocultural backgrounds, values and beliefs, emotions, gender, physical health status, and roles and relationships. Variables associated with illness such as pain, anxiety, and medication effects also affect nurse-patient communication.

Environment

The environment is the setting for sender-receiver interaction. For effective communication the environment needs to meet participant needs for physical and emotional comfort and safety. Noise, temperature extremes, distractions, and lack of privacy or space create confusion, tension, and discomfort. Environmental distractions are common in health care settings and interfere with messages sent between people. You control the environment as much as possible to create favorable conditions for effective communication.

Forms of Communication

Messages are conveyed verbally and nonverbally, concretely and symbolically. As people communicate, they express themselves through words, movements, voice inflection, facial expressions, and use of space. These elements work in harmony to enhance a message or conflict with one another to contradict and confuse it.

Verbal Communication

Verbal communication uses spoken or written words. Verbal language is a code that conveys specific meaning through a combination of words. The most important aspects of verbal communication are presented in the following paragraphs.

Vocabulary

Communication is unsuccessful if senders and receivers cannot translate one another’s words and phrases. When a nurse cares for a patient who speaks another language, an interpreter is often necessary. Even those who speak the same language use subcultural variations of certain words (e.g., dinner means a noon meal to one person and the last meal of the day to another). Medical jargon (technical terminology used by health care providers) sounds like a foreign language to patients unfamiliar with the health care setting. Limiting use of medical jargon to conversations with other health care team members improves communication. Children have a more limited vocabulary than adults. They may use special words to describe bodily functions or a favorite blanket or toy. Teenagers often use words in unique ways that are unfamiliar to adults.

Denotative and Connotative Meaning

Some words have several meanings. Individuals who use a common language share the denotative meaning: baseball has the same meaning for everyone who speaks English, but code denotes cardiac arrest primarily to health care providers. The connotative meaning is the shade or interpretation of the meaning of a word influenced by the thoughts, feelings, or ideas people have about the word. For example, health care providers tell a family that a loved one is in serious condition, and they believe that death is near; but to nurses serious simply describes the nature of the illness. You need to carefully select words, avoiding easily misinterpreted words, especially when explaining a patient’s medical condition or therapy. Even a much-used phrase such as “I’m going to take your vital signs” may be unfamiliar to an adult or frightening to a child.

Pacing

Conversation is more successful at an appropriate speed or pace. Speak slowly and enunciate clearly. Talking rapidly, using awkward pauses, or speaking slowly and deliberately conveys an unintended message. Long pauses and rapid shifts to another subject give the impression that you are hiding the truth. Think before speaking and develop an awareness of the rhythm of your speech to improve pacing.

Intonation

Tone of voice dramatically affects the meaning of a message. Depending on intonation, even a simple question or statement expresses enthusiasm, anger, concern, or indifference. Be aware of voice tone to avoid sending unintended messages. For example, a patient interprets a nurse’s patronizing tone of voice as condescending, and this inhibits further communication. A patient’s tone of voice often provides information about his or her emotional state or energy level.

Clarity and Brevity

Effective communication is simple, brief, and direct. Fewer words result in less confusion. Speaking slowly, enunciating clearly, and using examples to make explanations easier to understand improve clarity. Repeating important parts of a message also clarifies communication. Phrases such as “you know” or “OK?” at the end of every sentence detract from clarity. Use short sentences and words that express an idea simply and directly. “Where is your pain?” is much better than “I would like you to describe for me the location of your discomfort.”

Timing and Relevance

Timing is critical in communication. Even though a message is clear, poor timing prevents it from being effective. For example, you do not begin routine teaching when a patient is in severe pain or emotional distress. Often the best time for interaction is when a patient expresses an interest in communicating. If messages are relevant or important to the situation at hand, they are more effective. When a patient is facing emergency surgery, discussing the risks of smoking is less relevant than explaining presurgical procedures.

Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal communication includes the five senses and everything that does not involve the spoken or written word. Researchers have estimated that approximately 7% of meaning is transmitted by words, 38% is transmitted by vocal cues, and 55% is transmitted by body cues. Thus nonverbal communication is unconsciously motivated and more accurately indicates a person’s intended meaning than the spoken words (Jones, 2009). When there is incongruity between verbal and nonverbal communication, the receiver usually “hears” the nonverbal message as the true message.

All kinds of nonverbal communication are important, but interpreting them is often problematic. Sociocultural background is a major influence on the meaning of nonverbal behavior. In the United States, with its diverse cultural communities, nonverbal messages between people of different cultures are easily misinterpreted. Because the meaning attached to nonverbal behavior is so subjective, it is imperative that you verify it (Stuart, 2009). Assessing nonverbal messages is an important nursing skill.

Personal Appearance

Personal appearance includes physical characteristics, facial expression, and manner of dress and grooming. These factors help communicate physical well-being, personality, social status, occupation, religion, culture, and self-concept. First impressions are largely based on appearance. Nurses learn to develop a general impression of patient health and emotional status through appearance, and patients develop a general impression of the nurse’s professionalism and caring in the same way.

Posture and Gait

Posture and gait (way of walking) are forms of self-expression. The way people sit, stand, and move reflects attitudes, emotions, self-concept, and health status. For example, an erect posture and a quick, purposeful gait communicate a sense of well-being and confidence. Leaning forward conveys attention. A slumped posture and slow shuffling gait indicates depression, illness, or fatigue.

Facial Expression

The face is the most expressive part of the body. Facial expressions convey emotions such as surprise, fear, anger, happiness, and sadness. Some people have an expressionless face, or flat affect, which reveals little about what they are thinking or feeling. An inappropriate affect is a facial expression that does not match the content of a verbal message (e.g., smiling when describing a sad situation). People are sometimes unaware of the messages their expressions convey. For example, a nurse frowns in concentration while doing a procedure, and the patient interprets this as anger or disapproval. Patients closely observe nurses. Consider the impact a nurse’s facial expression has on a person who asks, “Am I going to die?” The slightest change in the eyes, lips, or facial muscles reveals the nurse’s feelings. Although it is hard to control all facial expressions, try to avoid showing shock, disgust, dismay, or other distressing reactions in a patient’s presence.

Eye Contact

People signal readiness to communicate through eye contact. Maintaining eye contact during conversation shows respect and willingness to listen. Eye contact also allows people to closely observe one another. Lack of eye contact may indicate anxiety, defensiveness, discomfort, or lack of confidence in communicating. However, persons from some cultures consider eye contact intrusive, threatening, or harmful and minimize or avoid its use (see Chapter 9). Always consider a person’s culture when interpreting the meaning of eye contact. Eye movements communicate feelings and emotions. Looking down on a person establishes authority, whereas interacting at the same eye level indicates equality in the relationship. Rising to the same eye level as an angry person helps establish autonomy.

Gestures

Gestures emphasize, punctuate, and clarify the spoken word. Gestures alone carry specific meanings, or they create messages with other communication cues. A finger pointed toward a person communicates several meanings; but, when accompanied by a frown and stern voice, the gesture becomes an accusation or threat. Pointing to an area of pain is sometimes more accurate than describing its location.

Sounds

Sounds such as sighs, moans, groans, or sobs also communicate feelings and thoughts. Combined with other nonverbal communication, sounds help to send clear messages. They have several interpretations: moaning conveys pleasure or suffering, and crying communicates happiness, sadness, or anger. Validate nonverbal messages with the patient to interpret them accurately.

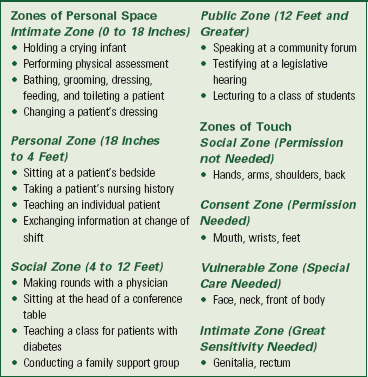

Territoriality and Personal Space

Territoriality is the need to gain, maintain, and defend one’s right to space. Territory is important because it provides people with a sense of identity, security, and control. It is sometimes separated and made visible to others such as a fence around a yard or a bed in a hospital room. Personal space is invisible, individual, and travels with the person. During interpersonal interaction, people maintain varying distances between each other, depending on their culture, the nature of their relationship, and the situation. When personal space becomes threatened, people respond defensively and communicate less effectively. Situations dictate whether the interpersonal distance between nurse and patient is appropriate. Box 24-3 provides examples of nursing actions within zones of personal space and touch (Kneisl and Trigoboff, 2009; Stuart, 2009). Nurses frequently move into patients’ territory and personal space because of the nature of caregiving. You need to convey confidence, gentleness, and respect for privacy, especially when your actions require intimate contact or involve a patient’s vulnerable zone.

Symbolic Communication

Good communication requires awareness of symbolic communication, the verbal and nonverbal symbolism used by others to convey meaning. Art and music are forms of symbolic communication used by nurses to enhance understanding and promote healing. Lane (2006) found that creative expressions such as art, music, and dance have a healing effect on patients. Patients reported decreased pain and a greater sense of joy and hope.

Metacommunication

Metacommunication is a broad term that refers to all factors that influence communication. Awareness of influencing factors helps people better understand what is communicated (Arnold and Boggs, 2011). For example, a nurse observes a young patient holding his body rigidly, and his voice is sharp as he says, “Going to surgery is no big deal.” The nurse replies, “You say having surgery doesn’t bother you, but you look and sound tense. I’d like to help.” Awareness of the tone of the verbal response and the nonverbal behavior results in further exploration of the patient’s feelings and concerns.

Professional Nursing Relationships

A nurse’s application of knowledge, understanding of human behavior and communication, and commitment to ethical behavior help create professional relationships. Having a philosophy based on caring and respect for others helps you be more successful in establishing relationships of this nature.

Nurse-Patient Helping Relationships

Helping relationships are the foundation of clinical nursing practice. In such relationships you assume the role of professional helper and come to know a patient as an individual who has unique health needs, human responses, and patterns of living. Therapeutic relationships promote a psychological climate that facilitates positive change and growth. Therapeutic communication between you and your patients allows the attainment of health-related goals (Arnold and Boggs, 2011). The goals of a therapeutic relationship focus on a patient achieving optimal personal growth related to personal identity, ability to form relationships, and ability to satisfy needs and achieve personal goals (Stuart, 2009). There is an explicit time frame, a goal-directed approach, and a high expectation of confidentiality. A nurse establishes, directs, and takes responsibility for the interaction; and a patient’s needs take priority over a nurse’s needs. Your nonjudgmental acceptance of a patient is an important characteristic of the relationship. Acceptance conveys a willingness to hear a message or acknowledge feelings. It does not mean that you always agree with the other person or approve of the patient’s decisions or actions. A helping relationship between you and a patient does not just happen—you create it with care, skill, and trust.

A natural progression of four goal-directed phases characterizes the nurse-patient relationship. The relationship often begins before you meet a patient and continues until the caregiving relationship ends (Box 24-4). Even a brief interaction uses an abbreviated version of the same preinteraction, orientation, working, and termination phases (Stuart, 2009). For example, the nursing student gathers patient information to prepare in advance for caregiving, meets the patient and establishes trust, accomplishes health-related goals through use of the nursing process, and says goodbye at the end of the day.

Socializing is an important initial component of interpersonal communication. It helps people get to know one another and relax. It is easy, superficial, and not deeply personal; whereas therapeutic interactions are often more intense, difficult, and uncomfortable. A nurse often uses social conversation to lay a foundation for a closer relationship: “Hi, Mr. Simpson, I hear it’s your birthday today. How old are you?” A friendly, informal, and warm communication style helps establish trust, but you have to get beyond social conversation to talk about issues or concerns affecting the patient’s health. During social conversation some patients ask personal questions such as those about your family or place of residence. Students often wonder whether it is appropriate to reveal such information. The skillful nurse uses judgment about what to share and provides minimal information or deflects such questions with gentle humor and refocuses conversation back to the patient.

Creating a therapeutic environment depends on your ability to communicate, comfort, and help patients meet their needs. Comfort is a critical value inherent in the practice of nursing. Therapeutic interactions increase feelings of personal control by helping a person feel secure, informed, and valued. Optimizing personal control facilitates emotional comfort, which minimizes physical discomfort and enhances recovery activities (Williams and Irurita, 2006).

In a therapeutic relationship it is important to encourage patients to share personal stories. Sharing stories is called narrative interaction. Through narrative interactions you begin to understand the context of others’ lives and learn what is meaningful for them from their perspective. For example, a nurse uses narratives to understand a patient’s perception of risk and the meaning of risk when taking medication that increases the risk of bleeding (Andreas et al., 2010) and to explore patient experiences of dignity in care (Dawood and Gallini, 2010). It is important to listen to patient stories to better understand their concerns, experiences, and challenges. This information is not usually revealed using a standard history form that elicits short answers.

Nurse-Family Relationships

Many nursing situations, especially those in community and home care settings, require you to form helping relationships with entire families. The same principles that guide one-on-one helping relationships also apply when the patient is a family unit, although communication within families requires additional understanding of the complexities of family dynamics, needs, and relationships (see Chapter 10).

Nurse–Health Care Team Relationships

Communication with other members of the health care team affects patient safety and the work environment. Breakdown in communication is a frequent cause of serious injuries in health care settings (World Health Organization, 2007). When patients move from one nursing unit to another or from one provider to another, also known as hand-offs, there is a risk for miscommunication. Accurate communication is essential to prevent errors (Cronenwett et al., 2007).

Use of common language when communicating critical information helps prevent misunderstandings. SBAR is a popular communication tool that helps standardize communication among health care providers. SBAR stands for Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation (Pope et al., 2008). Research indicates that effective communication between health care providers and other members of the health care team ensures patient safety and promotes optimal patient outcomes (Amato-Vealey, Barba, and Vealey, 2008). Evidence identifies nursing actions that increase effectiveness of nurse-to-nurse interaction and interprofessional communication (Box 24-5).

Professional nursing care requires nurses to interact with members of the nursing team and interdisciplinary health care providers. Effective communication leads to a healthy work environment (Triola, 2006). Communication focuses on team building, facilitating group processes, collaborating, consulting, delegating, supervising, leading, and managing (see Chapter 21). Social, informational, and therapeutic interactions help team members build morale, accomplish goals, and strengthen working relationships. Lateral violence between colleagues sometimes occurs and includes behaviors such as withholding information, backbiting, making snide remarks, and nonverbal expressions of disapproval such as raising eyebrows or making faces. Lateral violence has an adverse effect on the work environment, leading to job dissatisfaction, poor retention of qualified nurses, nurses leaving the profession, and poor teamwork (Sheridan-Leos, 2008). It interferes with effective health care team communication and jeopardizes patient safety (Harter and Moody, 2010). Intimidation decreases the likelihood that a nurse will report a near-miss, question an order, or take action to improve the quality of patient care. There must be zero tolerance of lateral violence. Develop skill in conflict management and assertive communication to stop the spread of lateral violence in the workplace (Patterson, 2007).

Nurse-Community Relationships

Many nurses form relationships with community groups by participating in local organizations, volunteering for community service, or becoming politically active. You need to establish relationships with your community to be an effective change agent (see Chapter 3). Effective health communication requires awareness of language, nonverbal communication, and respect for contextual and cultural influences (Greef et al., 2009). Communication within the community occurs through channels such as neighborhood newsletters, health fairs, public bulletin boards, newspapers, radio, television, and electronic information sites. Use these forms of communication to share information and discuss issues important to community health.

Elements of Professional Communication

Professional appearance, demeanor, and behavior are important in establishing trustworthiness and competence. They communicate that you have assumed the professional helping role, are clinically skilled, and are focused on your patients. Nothing harms the professional image of nursing like an individual nurse’s inappropriate appearance or behavior.

A professional is expected to be clean, neat, well groomed, conservatively dressed, and odor free. Visible tattoos and piercings are not acceptable in the professional setting. Professional behavior reflects warmth, friendliness, confidence, and competence. Professionals speak in a clear, well-modulated voice; use good grammar; listen to others; help and support colleagues; and communicate effectively. Being on time, organized, well prepared, and equipped for the responsibilities of the nursing role also communicate professionalism.

Courtesy

Common courtesy is part of professional communication. To practice courtesy, say hello and goodbye to patients and knock on doors before entering. State your purpose, address people by name, and say “ ‘please” and “thank you” to team members. When a nurse is discourteous, others perceive him or her as rude or insensitive. It sets up barriers between nurse and patient and causes friction among team members.

Use of Names

Always introduce yourself. Failure to give your name and status (e.g., nursing student, registered nurse, or licensed practical nurse) or acknowledge a patient creates uncertainty about the interaction and conveys an impersonal lack of commitment or caring. Making eye contact and smiling recognizes others. Addressing people by name conveys respect for human dignity and uniqueness. Because using last names is respectful in most cultures, nurses usually use a patient’s last name in an initial interaction and then use the first name if the patient requests it. Ask how your patients and co-workers prefer to be addressed and honor their personal preferences. Using first names is appropriate for infants, young children, patients who are confused or unconscious, and close team members. Avoid terms of endearment such as “honey,” “dear,” “grandma,” or “sweetheart.” Avoid referring to patients by diagnosis, room number, or other attribute, which is demeaning and sends the message that you do not care enough to know the person as an individual.

Trustworthiness

Trust is relying on someone without doubt or question. Being trustworthy means helping others without hesitation. To foster trust, communicate warmth and demonstrate consistency, reliability, honesty, competence, and respect. Sometimes it isn’t easy for a patient to ask for help. Trusting another person involves risk and vulnerability; but it also fosters open, therapeutic communication and enhances the expression of feelings, thoughts, and needs. Without trust a nurse-patient relationship rarely progresses beyond social interaction and superficial care. Avoid dishonesty at all costs. Withholding key information, lying, or distorting the truth violates both legal and ethical standards of practice. Sharing personal information or gossiping about others sends the message that you cannot be trusted and damages interpersonal relationships.

Autonomy and Responsibility

Autonomy is being self-directed and independent in accomplishing goals and advocating for others. Professional nurses make choices and accept responsibility for the outcomes of their actions (Townsend, 2009). They take initiative in problem solving and communicate in a way that reflects the importance and purpose of the therapeutic conversation (Arnold and Boggs, 2011). Professional nurses also recognize a patient’s autonomy.

Assertiveness

Assertiveness allows you to express feelings and ideas without judging or hurting others. Assertive behavior includes intermittent eye contact; nonverbal communication that reflects interest, honesty, and active listening; spontaneous verbal responses with a confident voice; and culturally sensitive use of touch and space. An assertive nurse communicates self-assurance; communicates feelings; takes responsibility for choices; and is respectful of others’ feelings, ideas, and choices (Stuart, 2009; Townsend, 2009). Assertive behavior increases self-esteem and self-confidence, increases the ability to develop satisfying interpersonal relationships, and increases goal attainment. Assertive individuals make decisions and control their lives more effectively than nonassertive individuals. They deal with criticism and manipulation by others, learn to say no, set limits, and resist intentionally imposed guilt. Assertive responses contain “I” messages such as “I want,” “I need,” “I think,” or “I feel” (Townsend, 2009).

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care. It guides care for patients who need special assistance with communication. Use therapeutic communication techniques as an intervention in an interpersonal nursing situation.

Assessment

During the assessment process thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

Patient-centered care requires careful assessment of a patient’s values, preferences, and cultural, ethnic, and social backgrounds (Cronenwett et al., 2007). Internal and external factors affect a patient’s ability to communicate (Box 24-6). Assessing these factors keeps the focus on the patient and helps you make patient-centered decisions during the communication process.

Physical and Emotional Factors

It is especially important to assess the psychophysiological factors that influence communication. Many altered health states and human responses limit communication. Persons with hearing or visual impairments often have difficulty receiving messages (see Chapter 49). Facial trauma, laryngeal cancer, or endotracheal intubation often prevents movement of air past vocal cords or mobility of the tongue, resulting in inability to articulate words. An extremely breathless person needs to use oxygen to breathe rather than speak. Persons with aphasia after a stroke or in late-stage Alzheimer’s disease often cannot understand or form words. Some mental illnesses such as psychoses or depression cause patients to jump from one topic to another, constantly verbalize the same words or phrases, or exhibit a slowed speech pattern. Persons with high anxiety are sometimes unable to perceive environmental stimuli or hear explanations. Finally, patients who are unresponsive or heavily sedated cannot send or respond to verbal messages.

Review of a patient’s medical record provides relevant information about his or her ability to communicate. The medical history and physical examination document physical barriers to speech, neurological deficits, and pathophysiology affecting hearing or vision. Reviewing a patient’s medication record is also important. For example, opiates, antidepressants, neuroleptics, hypnotics, or sedatives may cause a patient to slur words or use incomplete sentences. The nursing progress notes sometimes reveal other factors that contribute to communication difficulties such as the absence of family members to provide more information about a confused patient.

Assessment includes communicating directly with patients to determine their ability to attend to, interpret, and respond to stimuli. If patients have difficulty communicating, it is important to assess the effect of the problem. Patients who cannot communicate effectively often have difficulty expressing needs and responding appropriately to the environment. Patients who are unable to speak are at risk for injury unless nurses identify an alternate communication method. If barriers exist that make it difficult to communicate directly with patients, family or friends become important sources concerning the patients’ communication patterns and abilities.

Developmental Factors

Aspects of a patient’s growth and development also influence nurse-patient interaction. For example, an infant’s self-expression is limited to crying, body movement, and facial expression; whereas older children express their needs more directly. Adapt communication techniques to the special needs of infants and children. Communicating with children and their parents requires special consideration. Depending on the child’s age, include the parents, child, or both as sources of information about the child’s health. Giving a young child toys or other distractions allows parents to give you their full attention. Children are especially responsive to nonverbal messages; sudden movements, loud noises, or threatening gestures are frightening. They often prefer to make the first move in interpersonal contacts and do not like adults to stare or look down at them. A child who has received little environmental stimulation possibly is behind in language development, thus making communication more challenging.

Age alone does not determine an adult’s capacity for communication. Hearing loss and visual impairments are common changes that occur during aging that contribute to communication barriers (Lubinski, 2010). Communicate with older adults on an adult level and avoid patronizing or speaking in a condescending manner. Simple measures facilitate communication with older individuals who have hearing loss (Box 24-7).

Sociocultural Factors

Culture influences thinking, feeling, behaving, and communicating. Be aware of the typical patterns of interaction that characterize various cultures. For example, European Americans are more open and willing to discuss private family matters; whereas Hispanics, African Americans, and Asian Americans are sometimes reluctant to reveal personal or family information to strangers. Hispanics and Asian Americans value a quiet demeanor and self-restraint; to be open or argumentative reflects negatively on family honor. Native Americans also value silence and are comfortable with it.

Foreign-born persons do not always speak or understand English. Those who speak English as a second language often experience difficulty with self-expression or language comprehension. To practice cultural sensitivity in communication, understand that persons of different cultures use different degrees of eye contact, personal space, gestures, loudness of voice, pace of speech, touch, silence, and meaning of language. Make a conscious effort not to interpret messages through your cultural perspective, but consider the communication within the context of the other individual’s background. Avoid stereotyping, patronizing, or making fun of other cultures. Language and cultural barriers are not only frustrating but also dangerous, causing delay in care (Box 24-8).

Gender

Gender is another factor influencing how we think, act, feel, and communicate. Men tend to use less verbal communication but are more likely to initiate communication and address issues more directly. They are also more likely to talk about issues. Women tend to disclose more personal information and use more active listening, answering with responses that encourage the other person to continue the conversation. It is important for you to recognize a patient’s gender communication pattern. Being insensitive blocks therapeutic nurse-patient relationships. Newer research questions the differences between male and female communication patterns (Arnold and Boggs, 2011). Assess communication patterns of each individual and do not make assumptions simply based on gender.

Nursing Diagnosis

Most individuals experience difficulty with some aspect of communication. Patients sometimes lack skills in attending, listening, responding, and self-expression as a result of illness or the effects of treatment. You will use creative communication techniques with individuals who experience more serious impairments in communication.

The primary nursing diagnostic label used to describe a patient with limited or no ability to communicate verbally is impaired verbal communication. This is the state in which an individual experiences a decreased, delayed, or absent ability to receive, process, transmit, and use symbols (Doenges et al., 2010). A patient has defining characteristics such as the inability to articulate words, inappropriate verbalization, difficulty forming words, and difficulty comprehending, which you cluster together to form the diagnosis. This diagnosis is useful for a wide variety of patients with special problems and needs related to communication such as impaired perception, reception, and articulation. Although a patient’s primary problem is impaired verbal communication, the associated difficulty in self-expression or altered communication patterns may also contribute to other nursing diagnoses:

The related factors for a nursing diagnosis focus on the causes of the communication disorder. In the case of impaired verbal communication, these are physiological, mechanical, anatomical, psychological, cultural, or developmental in nature. Accuracy in identifying related factors is necessary so you select interventions that effectively resolve the diagnostic problem. For example, you manage the diagnosis of impaired verbal communication related to cultural difference (Hispanic heritage) very differently than the diagnosis of impaired verbal communication related to hearing loss.

Planning

Once you have identified the nature of a patient’s communication dysfunction, consider several factors when designing the care plan. Motivation is a factor in improving communication, and patients often require encouragement to try different approaches that involve significant change. It is especially important to involve the patient and family in decisions about the plan of care to determine whether suggested methods are acceptable. Meet basic comfort and safety needs before introducing new communication methods and techniques. Allow adequate time for practice. Participants need to be patient with themselves and one another to achieve effective communication. When the focus is on practicing communication, arrange for a quiet, private place that is free of distractions such as television or visitors. Communication aids such as a writing or picture board for a patient with a tracheostomy or a special call system for a paralyzed patient enhance communication.

Goals and Outcomes

In general, the goal of effective nursing care is that the patient experiences a sense of trust in the nurse and health care team. Expected outcomes for the patient with impaired communication are also important to identify. Outcomes are very specific and measurable and a way to determine if the broader goal is met. For example, outcomes for the patient possibly include the following:

• Patient initiates conversation about diagnosis or health care problem.

• Patient is able to attend to appropriate stimuli.

• Patient conveys clear and understandable messages with health care team.

• Patient expresses increased satisfaction with the communication process.

At times you care for patients whose difficulty in sending, receiving, and interpreting messages interferes with healthy interpersonal relationships. In this case impaired communication is a contributing factor to other nursing diagnoses such as impaired social interaction or ineffective coping. Plan interventions to help these patients improve their communication skills. Expected outcomes for a patient in this situation possibly include demonstrating the ability to appropriately express needs, feelings, and concerns; communicating thoughts and feelings more clearly; engaging in appropriate social conversation with peers and staff; and increasing feelings of autonomy and assertiveness.

Setting Priorities

It is essential to always maintain an open line of communication so a patient is able to express emergent needs or problems. This sometimes involves an intervention as simple as keeping a call light in reach for a patient restricted to bed or providing communication augmentative devices (e.g., message board or Braille computer). When you plan to have lengthy interactions with a patient, it is important to address physical care priorities so the discussion is not interrupted. Make the patient comfortable by ensuring that any symptoms are under control and elimination needs have been met.

Teamwork and Collaboration

To ensure an effective plan of care, you sometimes need to collaborate with other health care team members who have expertise in communication strategies. Speech therapists help patients with aphasia, interpreters are often necessary for patients who speak a foreign language, and mental health nurse specialists help angry or highly anxious patients to communicate more effectively.

Implementation

In carrying out any plan of care, use communication techniques that are appropriate for a patient’s individual needs. Before learning how to adapt communication methods to help patients with serious communication impairments, it is necessary to learn the communication techniques that serve as the foundation for professional communication. It is also important to understand communication techniques that create barriers to effective interaction.

Therapeutic Communication Techniques

Therapeutic communication techniques are specific responses that encourage the expression of feelings and ideas and convey acceptance and respect. Learning these techniques helps you develop awareness of the variety of nursing responses available for use in different situations. Although some of the techniques seem artificial at first, skill and comfort increase with practice. Tremendous satisfaction results from developing therapeutic relationships and achieving desired patient outcomes.

Active Listening: Active listening means being attentive to what a patient is saying both verbally and nonverbally. Active listening facilitates patient communication. Inexperienced nurses sometimes feel the need to talk to prove they know what they are doing or to decrease anxiety (Stuart, 2009). It is often difficult at first to be quiet and really listen. Active listening enhances trust because you communicate acceptance and respect for a patient. Several nonverbal skills facilitate attentive listening. You identify them by the acronym SOLER (Townsend, 2009):

S—Sit facing the patient. This posture conveys the message that you are there to listen and are interested in what the patient is saying.

O—Observe an open posture (i.e., keep arms and legs uncrossed). This posture suggests that you are “open” to what the patient says. A “closed” position conveys a defensive attitude, possibly provoking a similar response in the patient.

L—Lean toward the patient. This posture conveys that you are involved and interested in the interaction.

E—Establish and maintain intermittent eye contact. This behavior conveys your involvement in and willingness to listen to what the patient is saying. Absence of eye contact or shifting the eyes gives the message that you are not interested in what the patient is saying.

R—Relax. It is important to communicate a sense of being relaxed and comfortable with the patient. Restlessness communicates a lack of interest and a feeling of discomfort to the patient.

Sharing Observations: Nurses make observations by commenting on how the other person looks, sounds, or acts. Stating observations often helps a patient communicate without the need for extensive questioning, focusing, or clarification. This technique helps start a conversation with quiet or withdrawn persons. Do not state observations that will embarrass or anger a patient, such as telling someone, “You look a mess!” Even if you make such an observation with humor, the patient can become resentful.

Sharing observations differs from making assumptions, which means drawing unnecessary conclusions about the other person without validating them. Making assumptions puts a patient in the position of having to contradict the nurse. Examples include the nurse interpreting fatigue as depression or assuming that untouched food indicates lack of interest in meeting nutritional goals. Making observations is a gentler and safer technique: “You look tired …,” “You seem different today …,” or “I see you haven’t eaten anything.”

Sharing Empathy: Empathy is the ability to understand and accept another person’s reality, accurately perceive feelings, and communicate this understanding to the other. To convey empathy, accurately perceive the patient’s situation, communicate that understanding to the patient, and act on your understanding to help the patient (Varcarolis and Halter, 2009). To express empathy, you reflect that you understand and feel the importance of the other person’s communication. Such empathetic understanding requires you to be both sensitive and imaginative, especially if you have not had similar experiences. Strive to be empathetic in every situation because it is a key to unlocking concern and communicating support for others. Statements reflecting empathy are highly effective because they tell a person that you heard both the emotional and the factual content of the communication. Empathetic statements are neutral and nonjudgmental and help establish trust in difficult situations. For example, the nurse says to an angry patient who has low mobility after a stroke, “It must be very frustrating to know what you want and not be able to do it.”

Sharing Hope: Nurses recognize that hope is essential for healing and learn to communicate a “sense of possibility” to others. Appropriate encouragement and positive feedback are important in fostering hope and self-confidence and for helping people achieve their potential and reach their goals. You give hope by commenting on the positive aspects of the other person’s behavior, performance, or response. Sharing a vision of the future and reminding others of their resources and strengths also strengthen hope. Reassure patients that there are many kinds of hope and that meaning and personal growth can come from illness experiences. For example, the nurse says to a patient discouraged about a poor prognosis, “I believe that you’ll find a way to face your situation because I’ve seen your courage and creativity.”

Sharing Humor: Humor is an important but often underused resource in nursing interactions. It is a coping strategy that adds perspective and helps a nurse and patient adjust to stress. The Association for Applied and Therapeutic Humor (2008) defines therapeutic humor as “any intervention that promotes health and wellness by stimulating a playful discovery, expression or appreciation of the absurdity or incongruity of life’s situations.” Humor provides emotional support to patients and humanizes the illness experience. Patients use humor to establish relationships with care providers; relieve anxiety about illness, diagnostic procedures, or treatments; and release anger in a socially acceptable manner (Buxman, 2008). The goals of using humor as a health care provider are to bring hope and joy to the situation and enhance a patient’s well-being and the therapeutic relationship. You use humor during the orientation phase of a relationship to establish a therapeutic relationship and during the working phase as you help a patient cope with a situation.

Today it is common that nurses care for patients from different cultures. When you interact with patients who do not have a full grasp of the language, it is important to realize that they may misunderstand or misinterpret jokes and statements meant to be humorous. It is also important to recognize that, when either a nurse or patient tries to speak in another language, mistakes sometimes occur.

Dean and Major (2008) found that humor enhances teamwork, relieves tension, and helps nurses reframe difficult situations, allowing them to gain perspective. It also increases emotional flexibility, allowing nurses to shift rapidly from one situation to another. Huntley (2009) noted that humor helps nurses cope with serious situations and improves the work environment. Laughter provides a diversion from stress-related tension.

Health care professionals sometimes use a kind of dark, negative humor after difficult or traumatic situations as a way to deal with unbearable tension and stress. This coping humor has a high potential for misinterpretation as uncaring by persons not involved in the situation. For example, nursing students are sometimes offended and wonder how staff are able to laugh and joke after unsuccessful resuscitation efforts. When nurses use coping humor within earshot of patients or their loved ones, great emotional distress results.

Sharing Feelings: Emotions are subjective feelings that result from one’s thoughts and perceptions. Feelings are not right, wrong, good, or bad, although they are pleasant or unpleasant. If individuals do not express feelings, stress and illness may worsen. You help patients express emotions by making observations, acknowledging feelings, encouraging communication, giving permission to express “negative” feelings, and modeling healthy emotional self-expression. At times patients will direct their anger or frustration prompted by their illness toward you. Do not take such expressions personally. Acknowledging patients’ feelings communicates that you listened to and understood the emotional aspects of their illness situation.

When you care for patients, be aware of your own emotions because feelings are difficult to hide. Students sometimes wonder whether it is helpful to share feelings with patients. Sharing emotion makes nurses seem more human and brings people closer. It is appropriate to share feelings of caring or even cry with others, as long as you are in control of the expression of these feelings and expresses them in a way that does not burden the patient or break confidentiality. Patients are perceptive and sense your emotions. It is usually inappropriate to discuss negative personal emotions such as anger or sadness with patients. A social support system of colleagues is helpful; and employee assistance programs, peer group meetings, and the use of interdisciplinary teams such as social work and pastoral care provide other means for nurses to safely express feelings away from patients.

Using Touch: Because of modern fast-paced technical environments, nurses are required more than ever to bring the sense of caring and human connection to their patients (see Chapter 7). Touch is one of the most potent forms of communication. Historically physical touch played a central role in healing (Leder and Krucoff, 2008). Nurses are privileged to experience more of this intimate form of personal contact than almost any other professional. Touch is used during procedures and assessment or to convey emotion (Playfair, 2010). It conveys many messages such as affection, emotional support, encouragement, tenderness, and personal attention. Comfort touch such as holding a hand is especially important for vulnerable patients who are experiencing severe illness with its accompanying physical and emotional losses (Fig. 24-2). When people are ill, they may feel detached from their body and become isolated from others. Touch helps them increase awareness of their body and gain connection with another person (Leder and Krucoff, 2008).

Students often initially find giving intimate care to be stressful, especially when caring for patients of the opposite gender. They learn to cope with intimate contact by changing their perception of the situation. Since much of what nurses do involves touching, you need to learn to be sensitive to others’ reactions to touch and use it wisely. It should be as gentle or as firm as needed and delivered in a comforting, nonthreatening manner. Sometimes you withhold touch (e.g., highly suspicious or angry persons respond negatively or even violently to a nurse’s touch).

Using Silence: It takes time and experience to become comfortable with silence. Most people have a natural tendency to fill empty spaces with words, but sometimes these spaces really allow time for a nurse and patient to observe one another, sort out feelings, think about how to say things, and consider what has been communicated. Silence prompts some people to talk. It allows a patient to think and gain insight (Stuart, 2009). In general, allow a patient to break the silence, particularly when he or she has initiated it.

Silence is particularly useful when people are confronted with decisions that require much thought. For example, it helps a patient gain the necessary confidence to share the decision to refuse medical treatment. It also allows the nurse to pay particular attention to nonverbal messages such as worried expressions or loss of eye contact. Remaining silent demonstrates patience and a willingness to wait for a response when the other person is unable to reply quickly. Silence is especially therapeutic during times of profound sadness or grief.

Providing Information: Providing relevant information tells other people what they need or want to know so they are able to make decisions, experience less anxiety, and feel safe and secure. It is also an integral aspect of health teaching. It usually is not helpful to hide information from patients, particularly when they seek it. If a health care provider withholds information, the nurse clarifies the reason with him or her. Patients have a right to know about their health status and what is happening in their environment. Information of a distressing nature needs to be communicated with sensitivity, at a pace appropriate to a patient’s ability to absorb it, and in general terms at first: “John, your heart sounds have changed from earlier today, and so has your blood pressure. I’ll let your doctor know.” A nurse provides information that enables others to understand what is happening and what to expect: “Mrs. Evans, John is getting an echocardiogram right now. This test uses painless sound waves to create a moving picture of his heart structures and valves and should tell us what is causing his murmur.”

Clarifying: To check whether understanding is accurate, restate an unclear or ambiguous message to clarify the sender’s meaning. In addition, ask the other person to rephrase it, explain further, or give an example of what the person means. Without clarification you may make invalid assumptions and miss valuable information. Despite efforts at paraphrasing, sometimes you do not understand the patient’s message. You need to let the patient know if this is the case: “I’m not sure I understand what you mean by ‘sicker than usual.’ What is different now?”

Focusing: Focusing centers on key elements or concepts of a message. If conversation is vague or rambling or patients begin to repeat themselves, focusing is a useful technique. Do not use focusing if it interrupts patients while they are discussing an important issue. Rather use it to guide the direction of conversation to important areas: “We’ve talked a lot about your medications; now let’s look more closely at the trouble you’re having in taking them on time.”

Paraphrasing: Paraphrasing is restating another’s message more briefly using one’s own words. Through paraphrasing you send feedback that lets a patient know that he or she is actively involved in the search for understanding. Practice is required to paraphrase accurately. If the meaning of a message is changed or distorted through paraphrasing, communication becomes ineffective. For example, a patient says, “I’ve been overweight all my life and never had any problems. I can’t understand why I need to be on a diet.” Paraphrasing this statement by saying, “You don’t care if you’re overweight,” is incorrect. It is more accurate to say, “You’re not convinced that you need a diet because you’ve stayed healthy.”

Asking Relevant Questions: Nurses ask relevant questions to seek information needed for decision making. Ask only one question at a time and fully explore one topic before moving to another area. During patient assessment questions follow a logical sequence and usually proceed from general to more specific. Open-ended questions allow patients to take the conversational lead and introduce pertinent information about a topic. For example, “What’s your biggest problem at the moment?” Use focused questions when more specific information is needed in an area: “How has your pain affected your life at home?” Allow patients to respond fully to open-ended questions before asking more-focused questions. Closed-ended questions elicit a yes, no, or one-word response: “How many times a day are you taking pain medication?” Although they are helpful during assessment, they are generally less useful during therapeutic exchanges.

Asking too many questions is sometimes dehumanizing. Seeking factual information does not allow a nurse or patient to establish a meaningful relationship or deal with important emotional issues. It is a way for a nurse to ignore uncomfortable areas in favor of more comfortable, neutral topics. A useful exercise is to try conversing without asking the other person a single question. By using techniques such as giving general leads (“tell me about it . . .”), making observations, paraphrasing, focusing, and providing information, you discover important information that would have remained hidden if you limited the communication process to questions alone.

Summarizing: Summarizing is a concise review of key aspects of an interaction. It brings a sense of satisfaction and closure to an individual conversation and is especially helpful during the termination phase of a nurse-patient relationship. By reviewing a conversation, participants focus on key issues and add relevant information as needed. Beginning a new interaction by summarizing a previous one helps a patient recall topics discussed and shows him or her that you analyzed their communication. Summarizing also clarifies expectations, as in this example of a nurse manager who has been working with an unsatisfied employee: “You’ve told me a lot of things about why you don’t like this job and how unhappy you’ve been. We’ve also come up with some possible ways to make things better, and you’ve agreed to try some of them and let me know if any help.”

Self-Disclosure: Self-disclosures are subjectively true personal experiences about the self that are intentionally revealed to another person. This is not therapy for a nurse; rather it shows patients that the nurse understands their experiences and their experiences are not unique. You choose to share experiences or feelings that are similar to those of the patient and emphasize both the similarities and differences. This kind of self-disclosure is indicative of the closeness of the nurse-patient relationship and involves a particular kind of respect for the patient. You offer it as an expression of sincerity and honesty, and it is an aspect of empathy (Stuart, 2009). Self-disclosures need to be relevant and appropriate and made to benefit the patient rather than yourself. Use them sparingly so the patient is the focus of the interaction: “That happened to me once, too. It was devastating, and I had to face some things about myself that I didn’t like. I went for counseling, and it really helped. . . . What are your thoughts about seeing a counselor?”

Confrontation: When you confront someone in a therapeutic way, you help the other person become more aware of inconsistencies in his or her feelings, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors (Stuart, 2009). This technique improves patient self-awareness and helps him or her recognize growth and deal with important issues. Use confrontation only after you have established trust, and do it gently with sensitivity: “You say you’ve already decided what to do, yet you’re still talking a lot about your options.”

Nontherapeutic Communication Techniques

Certain communication techniques hinder or damage professional relationships. These specific techniques are referred to as nontherapeutic or blocking and often cause recipients to activate defenses to avoid being hurt or negatively affected. Nontherapeutic techniques discourage further expression of feelings and ideas and engender negative responses or behaviors in others.

Asking Personal Questions: “Why don’t you and John get married?” Asking personal questions that are not relevant to the situation simply to satisfy your curiosity is not appropriate professional communication. Such questions are nosy, invasive, and unnecessary. If patients wish to share private information, they will. To learn more about a patient’s interpersonal roles and relationships, ask a question such as: “How would you describe your relationship with John?”

Giving Personal Opinions: “If I were you, I’d put your mother in a nursing home.” When a nurse gives a personal opinion, it takes decision making away from the other person. It inhibits spontaneity, stalls problem solving, and creates doubt. Personal opinions differ from professional advice. At times people need suggestions and help to make choices. Suggestions that you present are options; the other person makes the final decision. Remember that the problem and its solution belong to the other person and not to you. A much better response is, “Let’s talk about which options are available for your mother’s care.”

Changing the Subject: “Let’s not talk about your problems with the insurance company. It’s time for your walk.” Changing the subject when another person is trying to communicate their story is rude and shows a lack of empathy. It tends to block further communication, and the sender then withholds important messages or fails to openly express feelings. Thoughts and spontaneity are interrupted, ideas become tangled, and information provided is sometimes inadequate. In some instances changing the subject serves as a face-saving maneuver. If this happens, reassure the patient that you will return to his or her concerns: “After your walk let’s talk some more about what’s going on with your insurance company.”

Automatic Responses: “Older adults are always confused.” “Administration doesn’t care about the staff.” Stereotypes are generalized beliefs held about people. Making stereotyped remarks about others reflects poor nursing judgment and threatens nurse-patient or team relationships. A cliché is a stereotyped comment such as, “You can’t win them all,” that tends to belittle the other person’s feelings and minimize the importance of his or her message. These automatic phrases communicate that you are not taking concerns seriously or responding thoughtfully. Another kind of automatic response is parroting (i.e., repeating what the other person has said word for word). Parroting is easily overused and is not as effective as paraphrasing. A simple “oh?” gives you time to think if the other person says something that takes one by surprise.