Caring in Nursing Practice

• Discuss the role that caring plays in building the nurse-patient relationship.

• Compare and contrast theories on caring.

• Discuss the evidence that exists about patients’ perceptions of caring.

• Explain how an ethic of care influences nurses’ decision making.

• Describe ways to express caring through presence and touch.

• Describe the therapeutic benefit of listening to patients.

• Explain the relationship between knowing a patient and clinical decision making.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

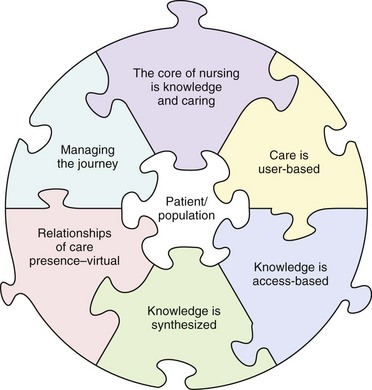

Caring is central to nursing practice, but it is even more important in today’s hectic health care environment. The demands, pressure, and time constraints in the health care environment leave little room for caring practice, which results in nurses and other health professionals becoming dissatisfied with their jobs and cold and indifferent to patient needs (Watson, 2006, 2009). Increasing use of technological advances for rapid diagnosis and treatment often causes nurses and other health care providers to perceive the patient relationship as less important. Technological advances become dangerous without a context of skillful and compassionate care. Despite these challenges, more professional organizations are stressing the importance of caring in health care. Nursing’s Agenda for the Future (ANA, 2002) states that “Nursing is the pivotal health care profession highly valued for its specialized knowledge, skill, and caring in improving the health status of the individual, family, and the community.” The American Organization of Nurse Executives (AONE, 2005) describes caring and knowledge as the core of nursing, with caring being a key component of what a nurse brings to a patient experience (Fig. 7-1).

FIG. 7-1 AONE guiding principles for future care delivery. (Copyright © 2005 by the American Organization of Nurse Executives [AONE]. All rights reserved.)

It is time to value and embrace caring practices and expert knowledge that are the heart of competent nursing practice (Benner and Wrubel, 1989; Benner et al., 2010). When you engage patients in a caring and compassionate manner, you learn that the therapeutic gain in caring makes enormous contributions to the health and well-being of your patients.

Have you ever been ill or experienced a problem requiring health care intervention? Think about that experience. Then consider the following two scenarios and select the situation that you believe most successfully demonstrates a sense of caring.

A nurse enters a patient’s room, greets the patient warmly while touching him or her lightly on the shoulder, makes eye contact, sits down for a few minutes and asks about the patient’s thoughts and concerns, listens to the patient’s story, looks at the intravenous (IV) solution hanging in the room, briefly examines the patient, and then checks the vital sign summary on the bedside computer screen before departing the room.

A second nurse enters the patient’s room, looks at the IV solution hanging in the room, checks the vital sign summary sheet on the bedside computer screen, and acknowledges the patient but never sits down or touches him or her. The nurse makes eye contact from above while the patient is lying in bed. He or she asks a few brief questions about the patient’s symptoms and leaves.

There is little doubt that the first scenario presents the nurse in specific acts of caring. The nurse’s calm presence, parallel eye contact, attention to the patient’s concerns, and physical closeness all express a person-centered, comforting approach. In contrast, the second scenario is task-oriented and expresses a sense of indifference to patient concerns. Both of these scenarios take approximately the same amount of time but leave very different patient perceptions. It is important to remember that, during times of illness or when a person seeks the professional guidance of a nurse, caring is essential in helping the individual reach positive outcomes.

Theoretical Views on Caring

Caring is a universal phenomenon influencing the ways in which people think, feel, and behave in relation to one another. Since Florence Nightingale, nurses have studied caring from a variety of philosophical and ethical perspectives. A number of nursing scholars have developed theories on caring because of its importance to nursing practice. This chapter does not detail all of the theories of caring, but it is designed to help you understand how caring is at the heart of a nurse’s ability to work with all patients in a respectful and therapeutic way.

Caring Is Primary

Benner offers nurses a rich, holistic understanding of nursing practice and caring through the interpretation of expert nurses’ stories. After listening to nurses’ stories and analyzing their meaning, she described the essence of excellent nursing practice, which is caring. The stories revealed the nurses’ behaviors and decisions that expressed caring. Caring means that persons, events, projects, and things matter to people (Benner and Wrubel, 1989; Benner et al., 2010). It is a word for being connected.

Caring determines what matters to a person. It underlies a wide range of interactions, from parental love to friendship, from caring for one’s work to caring for one’s pet, to caring for and about one’s patients. Benner and Wrubel (1989) note: “Caring creates possibility.” Personal concern for another person, an event, or thing provides motivation and direction for people to care. Caring as a professional framework has practical implications for transforming nursing practice (Drenkard, 2008). Through caring, nurses help patients recover in the face of illness, give meaning to their illness, and maintain or reestablish connection. Understanding how to provide humanistic caring and compassion begins early in nursing education and continues to mature through experiential practice (Gallagher-Lepak and Kubsch, 2009).

Patients are not all the same. Each person brings a unique background of experiences, values, and cultural perspectives to a health care encounter. Caring is always specific and relational for each nurse-patient encounter. As nurses acquire more experience, they typically learn that caring helps them to focus on the patients for whom they care. Caring facilitates a nurse’s ability to know a patient, allowing the nurse to recognize a patient’s problems and find and implement individualized solutions.

Leininger’s Transcultural Caring

From a transcultural perspective, Madeleine Leininger (1991) describes the concept of care as the essence and central, unifying, and dominant domain that distinguishes nursing from other health disciplines (see Chapter 4). Care is an essential human need, necessary for the health and survival of all individuals. Care, unlike cure, helps an individual or group improve a human condition. Acts of caring refer to nurturing and skillful activities, processes, and decisions to assist people in ways that are empathetic, compassionate, and supportive. An act of caring depends on the needs, problems, and values of the patient. Leininger’s studies of numerous cultures around the world found that care helps protect, develop, nurture, and provide survival to people. It is needed for people of all cultures to recover from illness and to maintain healthy life practices.

Leininger (1991) stresses the importance of nurses’ understanding cultural caring behaviors. Even though human caring is a universal phenomenon, the expressions, processes, and patterns of caring vary among cultures (Box 7-1). Caring is very personal; thus its expression differs for each patient. For caring to be effective, nurses need to learn culturally specific behaviors and words that reflect human caring in different cultures to identify and meet the needs of all patients (see Chapter 9).

Watson’s Transpersonal Caring

Patients and their families expect a high quality of human interaction from nurses. Unfortunately many conversations between patients and their nurses are very brief and disconnected. Watson’s theory of caring is a holistic model for nursing that suggests that a conscious intention to care promotes healing and wholeness (Watson, 2005, 2010). The theory integrates the human caring processes with healing environments, incorporating the life-generating and life-receiving processes of human caring and healing for nurses and their patients (Watson, 2006). The theory describes a consciousness that allows nurses to raise new questions about what it means to be a nurse, to be ill, and to be caring and healing. The transpersonal caring theory rejects the disease orientation to health care and places care before cure (Watson, 1996, 2008). The practitioner looks beyond the patient’s disease and its treatment by conventional means. Instead, transpersonal caring looks for deeper sources of inner healing to protect, enhance, and preserve a person’s dignity, humanity, wholeness, and inner harmony (see also Chapter 4).

In Watson’s view caring becomes almost spiritual. It preserves human dignity in the technological, cure-dominated health care system (Watson, 2006). The emphasis is on the nurse-patient relationship. The focus is on the people behind the patient and nurse and the caring relationship (Table 7-1). A nurse communicates caring-healing to the patient through the consciousness of the nurse. This takes place during a single caring moment between nurse and patient. A connection forms between the one cared for and the one caring. The model is transformative because the relationship influences both the nurse and the patient for better or for worse (Watson, 2006, 2010). Caring-healing consciousness promotes healing. Application of Watson’s caring model in practice enhances nurses’ caring practices (Box 7-2).

TABLE 7-1

Watson’s 10 Carative Factors (Watson, 2005, 2008)

| CARATIVE FACTOR | EXAMPLE IN PRACTICE |

| Forming a human-altruistic value system | Use loving kindness to extend yourself. Use self-disclosure appropriately to promote a therapeutic alliance with your patient. |

| Instilling faith-hope | Provide a connection with the patient that offers purpose and direction when trying to find the meaning of an illness. |

| Cultivating a sensitivity to one’s self and to others | Learn to accept yourself and others for their full potential. A caring nurse matures into becoming a self-actualized nurse. |

| Developing a helping, trusting, human caring relationship | Learn to develop and sustain helping, trusting, authentic, caring relationships through effective communication with your patients. |

| Promoting and expressing positive and negative feelings | Support and accept your patients’ feelings. In connecting with your patients you show a willingness to take risks in sharing in the relationship. |

| Using creative problem-solving, caring processes | Apply the nursing process in systematic, scientific problem-solving decision making in providing patient-centered care. |

| Promoting transpersonal teaching-learning | Learn together while educating the patient to acquire self-care skills. The patient assumes responsibility for learning. |

| Providing for a supportive, protective, and/or corrective mental, physical, societal, and spiritual environment | Create a healing environment at all levels, physical and nonphysical. This promotes wholeness, beauty, comfort, dignity, and peace. |

| Meeting human needs | Assist patients with basic needs with an intentional care and caring consciousness. |

| Allowing for existential-phenomenological-spiritual forces | Allow spiritual forces to provide a better understanding of yourself and your patient. |

Swanson’s Theory of Caring

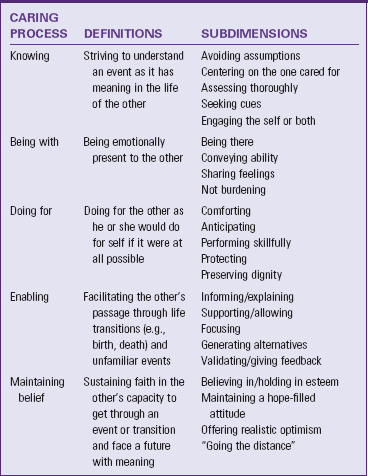

Kristen Swanson (1991) studied patients and professional caregivers in an effort to develop a theory of caring for nursing practice. This middle-range theory of caring was developed from three perinatal studies that interviewed women who miscarried, parents and health care professionals in a newborn intensive care unit, and socially at-risk mothers who received long-term public health intervention. All groups were in a perinatal (before, during, or after the birth of a child) setting or context and experienced the phenomenon of caring. Researchers asked each group questions regarding how they experienced or expressed caring in their situations (Swanson, 1999a, 1999b). After analyzing the stories and descriptions of the three groups, Swanson developed a theory of caring. The theory describes caring as consisting of five categories or processes (Table 7-2). Swanson (1991) defines caring as a nurturing way of relating to a valued other toward whom one feels a personal sense of commitment and responsibility. This theory supports the claim that caring is a central nursing phenomenon but not necessarily unique to nursing practice.

Swanson’s work (1991) provides direction for how to develop useful and effective caring strategies. Each of the caring processes has definitions and subdimensions that serve as the basis for nursing interventions. Nursing care and caring are crucial in making positive differences in patients’ health and well-being outcomes (Swanson, 1999a). Thus research findings develop and refine the theory and continue to guide clinical nursing practice (Andershed and Olsson, 2009). For example, Swanson (1999b) tested the effects of caring-based counseling on women’s emotional well-being in the first year after miscarrying. Caring-based counseling was significant in reducing women’s depression and anger, particularly for women in the first 4 months following miscarriage.

Summary of Theoretical Views

Nursing caring theories have common themes. Duffy, Hoskins, and Seifert (2007) identify these commonalities as human interaction or communication, mutuality, appreciating the uniqueness of individuals, and improving the welfare of patients and their families. Caring is highly relational. The nurse and the patient enter into a relationship that is much more than one person simply “doing tasks for” another. There is a mutual give-and-take that develops as nurse and patient begin to know and care for one another (Hudacek, 2008; Sumner, 2010). Caring theories are valuable when assessing patient perceptions of being cared for in a multicultural environment (Suliman et al., 2009). Frank (1998) described a personal situation when he was suffering from cancer: “What I wanted when I was ill was a mutual relationship of persons who were also clinician and patient.” It was important for Frank to be seen as one of two fellow human beings, not the dependent patient being cared for by the expert technical clinician.

Caring seems highly invisible at times when a nurse and patient enter a relationship of respect, concern, and support. The nurse’s empathy and compassion become a natural part of every patient encounter. However, when caring is absent, it becomes very obvious. For example, if the nurse shows disinterest or chooses to avoid a patient’s request for help, his or her inaction quickly conveys an uncaring attitude. Benner and Wrubel (1989) relate the story of a clinical nurse specialist who learned from a patient what caring is all about: “I felt that I was teaching him a lot, but actually he taught me. One day he said to me (probably after I had delivered some well-meaning technical information about his disease), ‘You’re doing an OK job, but I can tell that every time you walk in that door you’re walking out.’ ” In this nurse’s story the patient perceived that the nurse was simply going through the motions of teaching and showed little caring toward the patient. Patients quickly know when nurses fail to relate to them.

As you practice caring, your patient will sense your commitment and willingness to enter into a relationship that allows you to understand the patient’s experience of illness. In a study of oncology patients, one patient described a nurse’s caring as “putting the heart in it” and “having an investment” that makes “patients feel that you are with them” (Radwin, 2000). Thus the nurse becomes a coach and partner rather than a detached provider of care.

One aspect of caring is enabling, when a nurse and patient work together to identify alternatives in approaches to care and resources. Consider a nurse working with a patient recently diagnosed with diabetes mellitus who must learn how to administer daily insulin injections. The nurse enables the patient by providing instruction in a manner that allows the patient to successfully adapt diabetes management strategies such as self-medication, exercise, and diet to his own lifestyle.

Another common theme of caring is to understand the context of a person’s life and illness. It is difficult to show caring for another individual without gaining an understanding of who the person is and his or her perception of the illness. Exploring the following questions with your patients helps you understand their perceptions of illness: How was your illness first recognized? How do you feel about the illness? How does your illness affect your daily life practices? Knowing the context of a patient’s illness helps you choose and individualize interventions that will actually help the patient. This approach is more successful than simply selecting interventions on the basis of your patient’s symptoms or disease process.

Patients’ Perceptions of Caring

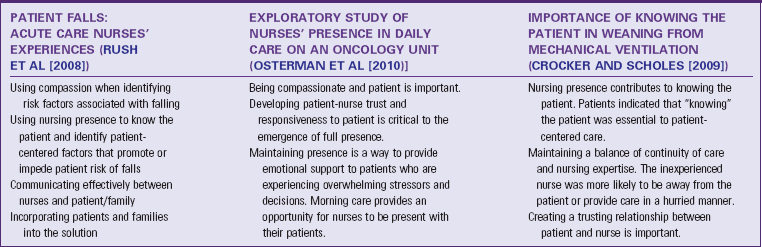

Leininger’s, Watson’s, and Swanson’s theories provide an excellent beginning to understanding the behaviors and processes that characterize caring. Researchers explored nursing care behaviors as perceived by patients (Table 7-3). Their findings emphasize what patients expect from their caregivers and thus provide useful guidelines for your practice. Patients continue to value nurses’ effectiveness in performing tasks; but clearly patients value the affective dimension of nursing care.

TABLE 7-3

Comparison of Research Studies Exploring Nurse Caring Behaviors (as Perceived by Patients)

The study of patients’ perceptions is important because health care is placing greater emphasis on patient satisfaction (see Chapter 2). Duffy, Hoskins, and Seifert (2007) developed the Caring Assessment Tool (CAT) to measure caring from a patient’s perspective. This tool and other caring assessments help you, as a beginning professional, to appreciate the type of behaviors that hospitalized patients identify as caring. When patients sense that health care providers are sensitive, sympathetic, compassionate, and interested in them as people, they usually become active partners in the plan of care (Gallagher-Lepak and Kubsch, 2009). Suliman et al. (2009) studied the impact of Watson’s caring theory as an assessment framework in a multicultural environment. Patients in the study indicated that they did not perceive any cultural bias when they perceived nurses to be caring. Radwin (2000) found that oncology patients associated excellent nursing care with attentiveness, partnership, individualization, rapport, and caring. As institutions look to improve patient satisfaction, creating an environment of caring is a necessary and worthwhile goal. Patient satisfaction with nursing care is an important factor in their decision to return to a hospital.

As you begin clinical practice, consider how patients perceive caring and the best approaches to provide care. Behaviors associated with caring offer an excellent starting point. It is also important to determine an individual patient’s perceptions and unique expectations. Frequently patients and nurses differ in their perceptions of caring (Hudacek, 2008). For that reason focus on building a relationship that allows you to learn what is important to your patients (Gallagher-Lepak and Kubsch, 2009). For example, your patient is fearful of having an intravenous catheter inserted, and you are still a novice at catheter insertion. Instead of giving a lengthy description of the procedure to relieve anxiety, you decide that the patient will benefit more if you obtain assistance from a skilled staff member. Knowing who patients are helps you select caring approaches that are most appropriate to their needs.

Ethic of Care

Caring is a moral imperative, not a commodity to be bought and sold. Caring for other human beings protects, enhances, and preserves human dignity. It is a professional, ethical covenant that nursing has with its public (Watson, 2010). Caring science provides a disciplinary foundation from which you deliver patient-centered care (Watson, 2005, 2008). Chapter 22 explores the importance of ethics in professional nursing. The term ethics refers to the ideals of right and wrong behavior. In any patient encounter a nurse needs to know what behavior is ethically appropriate. An ethic of care is unique so professional nurses do not make professional decisions based solely on intellectual or analytical principles. Instead, an ethic of care places caring at the center of decision making. For example, what resources should be used to care for an indigent patient? Is it caring to place a disabled relative in a long-term care facility?

An ethic of care is concerned with relationships between people and with a nurse’s character and attitude toward others. Nurses who function from an ethic of care are sensitive to unequal relationships that lead to an abuse of one person’s power over another—intentional or otherwise. In health care settings patients and families are often on unequal footing with professionals because of the patient’s illness, lack of information, regression caused by pain and suffering, and unfamiliar circumstances. An ethic of care places the nurse as the patient’s advocate, solving ethical dilemmas by attending to relationships and by giving priority to each patient’s unique personhood.

Caring in Nursing Practice

It is impossible to prescribe ways that guarantee whether or when a nurse becomes a caring professional. Experts disagree as to whether caring is teachable or more fundamentally a way of being in the world. For those who find caring a normal part of their lives, it is a product of their culture, values, experiences, and relationships with others. Persons who do not experience care in their lives often find it difficult to act in caring ways. As you deal with health and illness in your practice, you grow in your ability to care. Caring behaviors include providing presence, offering a caring touch, and listening.

Providing Presence

Providing presence is a person-to-person encounter conveying a closeness and sense of caring. Fredriksson (1999) explains that presence involves “being there” and “being with.” “Being there” is not only a physical presence; it also includes communication and understanding. Presence is an interpersonal process that is characterized by sensitivity, holism, intimacy, vulnerability, and adaptation to unique circumstances. It results in improved mental well-being for nurses and patients and improved physical well-being in patients (Finfgeld-Connett, 2006). The interpersonal relationship of “being there” depends on the fact that a nurse is attentive to the patient. Presence can be translated into an actual caring art that affects the healing and well-being of both the nurse and patient. It is often used in conjunction with other nursing interventions such as establishing the nurse-patient relationship, providing comfort measures, providing patient education, and listening. The outcomes of nursing presence include alleviating suffering, decreasing a sense of isolation and vulnerability, and personal growth (Zyblock, 2010). This type of presence is something the nurse offers to the patient in achieving patient care goals.

Nursing requires being present with patients at a moment of crisis or need (Zyblock, 2010). “Being with” is also interpersonal. The nurse gives himself or herself, which means being available and at a patient’s disposal. If patients accept the nurse, they will invite him or her to see, share, and touch their vulnerability and suffering. One’s human presence never leaves one unaffected (Watson, 2008). The nurse then enters the patient’s world. In this presence the patient is able to put words to feelings and understand himself or herself in a way that leads to identifying solutions, seeing new directions, and making choices.

When a nurse establishes presence, eye contact, body language, voice tone, listening, and a positive and encouraging attitude act together to create openness and understanding. The message conveyed is that the other’s experience matters to the one caring (Swanson, 1991). Establishing presence enhances the nurse’s ability to learn from the patient. This strengthens the nurse’s ability to provide adequate and appropriate nursing care.

It is especially important to establish presence and caring when patients are experiencing stressful events or situations. Awaiting a physician’s report of test results, preparing for an unfamiliar procedure, and planning for a return home after serious illness are just a few examples of events in the course of a person’s illness that can create unpredictability and dependency on care providers. The nurse’s presence and caring help to calm anxiety and fear related to stressful situations (Finfgeld-Connett, 2008a, 2008b). Giving reassurance and thorough explanations about a procedure, remaining at the patient’s side, and coaching the patient through the experience all convey a presence that is invaluable to the patient’s well-being.

Touch

Patients face situations that are embarrassing, frightening, and painful. Whatever the feeling or symptom, patients look to nurses to provide comfort. The use of touch is one comforting approach that reaches out to patients to communicate concern and support. Touch is relational and leads to a connection between nurse and patient. It involves contact and noncontact touch. Contact touch involves obvious skin-to-skin contact, whereas noncontact touch refers to eye contact. It is difficult to separate the two. Both in turn are described within three categories: task-oriented touch, caring touch, and protective touch (Fredriksson, 1999).

Nurses use task-oriented touch when performing a task or procedure. The skillful and gentle performance of a nursing procedure conveys security and a sense of competence. An expert nurse learns that any procedure is more effective when administered carefully and in consideration of any patient concern. For example, if a patient is anxious about having a procedure such as the insertion of a nasogastric tube, the nurse offers comfort through a full explanation of the procedure and what the patient will feel. Then the nurse performs the procedure safely, skillfully, and successfully. This is done as the nurse prepares the supplies, positions the patient, and gently manipulates and inserts the nasogastric tube. Throughout a procedure the nurse talks quietly with the patient to provide reassurance and support.

Caring touch is a form of nonverbal communication, which successfully influences a patient’s comfort and security, enhances self-esteem, increases confidence of the caregivers, and improves mental well-being (Osterman et al, 2010). You express this in the way you hold a patient’s hand, give a back massage, gently position a patient, or participate in a conversation. When using a caring touch, you connect with the patient physically and emotionally (Zyblock, 2010).

Protective touch is a form of touch that protects the nurse and/or patient (Fredriksson, 1999). The patient views it either positively or negatively. The most obvious form of protective touch is preventing an accident (e.g., holding and bracing the patient to avoid a fall). Protective touch is also a kind of touch that protects the nurse emotionally. A nurse withdraws or distances herself or himself from a patient when he or she is unable to tolerate suffering or needs to escape from a situation that is causing tension. When used in this way, protective touch elicits negative feelings in a patient (Fredriksson, 1999).

Because touch conveys many messages, use it with discretion. Touch itself is a concern when crossing cultural boundaries of either the patient or the nurse (Benner et al., 2010; Benner, 2004). The patient generally permits task-orientated touch because most individuals give nurses and physicians a license to enter their personal space to provide care (see Box 7-1, p. 80). Know and understand if patients accept touch and how they interpret your intentions.

Listening

Caring involves an interpersonal interaction that is much more than two persons simply talking back and forth (Bunkers, 2010). Listening is a critical component of nursing care and is necessary for meaningful interactions with patients (Shipley, 2010). It is a planned and deliberate act in which the listener is present and engages the patient in a nonjudgmental and accepting manner. It includes “taking in” what a patient says and interpreting and understanding what the patient is saying and then giving back that understanding to the patient (Shipley, 2010). Listening to the meaning of what a patient says helps create a mutual relationship. True listening leads to truly knowing and responding to what really matters to the patient and family.

When an individual becomes ill, he or she usually has a story to tell about the meaning of the illness. Any critical or chronic illness affects all of a patient’s life choices and decisions, sometimes the individual’s identity. Being able to tell that story helps the patient break the distress of illness. Thus a story needs a listener. Frank (1998) described his own feelings during his experience with cancer: “I needed a [health care professional’s] gift of listening in order to make my suffering a relationship between us, instead of an iron cage around me.” He needed to be able to express what he needed when he was ill. The personal concerns that are part of a patient’s illness story determine what is at stake for the patient. Caring through listening enables the nurse to be a participant in the patient’s life.

To listen effectively you need to silence yourself and listen with openness (Fredriksson, 1999). Fredriksson describes silencing one’s mouth and also the mind. It is important to remain intentionally silent and concentrate on what the patient has to say. Give patients your full, focused attention as they tell their stories.

When an ill person chooses to tell his or her story, it involves reaching out to another human being. Telling the story implies a relationship that develops only if the clinician exchanges his or her stories as well. Frank (1998) argues that professionals do not routinely take seriously their own need to be known as part of a clinical relationship. Yet, unless the professional acknowledges this need, there is no reciprocal relationship, only an interaction. There is pressure on the clinician to know as much as possible about the patient, but it isolates the clinician from the patient. By contrast, in knowing and being known, each supports the other (Frank, 1998).

Through active listening you begin to truly know your patients and what is important to them (Bernick, 2004). Learning to listen to a patient is sometimes difficult. It is easy to become distracted by tasks at hand, colleagues shouting instructions, or other patients waiting to have their needs met. However, the time you take to listen effectively is worthwhile, in both the information gained and the strengthening of the nurse-patient relationship. Listening involves paying attention to the individual’s words and tone of voice and entering his or her frame of reference (see Chapter 24). By observing the expressions and body language of the patient, you find cues to help the patient explore ways to achieve greater peace.

Knowing the Patient

One of the five caring processes described by Swanson (1991) is knowing the patient. Knowing the patient comprises both the nurse’s understanding of a specific patient and his or her subsequent selection of interventions (Radwin, 2000). It is essential when providing patient-centered care. Two elements that facilitate knowing are continuity of care and clinical expertise. When patient care is fragmented, knowing the patient declines, and patient-centered care is compromised (Crocker and Scholes, 2009).

Knowing develops over time as a nurse learns the clinical conditions within a specialty and the behaviors and physiological responses of patients. Intimate knowing helps the nurse respond to what really matters to the patient. To know a patient means that the nurse avoids assumptions, focuses on the patient, and engages in a caring relationship with the patient that reveals information and cues that facilitate critical thinking and clinical judgments (see Chapter 15). Knowing the patient is at the core of the clinical decision-making process.

Factors that contribute to knowing the patient include time, continuity of care, team work of the nursing staff, trust, and experience. Barriers to knowing the patient are often related to the organizational structure of the organization and economic constraints. Organizational changes often result in decreasing the amount of time that registered nurses are able to spend with their patients, which in turn affects the nurse-patient relationships. Decreased length of stay also reduces the interactions’ between nurses and their patients (Crocker and Scholes 2009; MacDonald, 2008).

Consequences of not knowing the patient are many. In the acute care setting, not knowing the patient contributes to risk for falls and actual falls (Rush et al., 2008). Patients and their families don’t understand the complexities of treatment and their participation in care (MacDonald, 2008). Finally, patients do not adequately understand their discharge guidelines and may administer their home medications or treatments incorrectly. By establishing a caring relationship, the understanding that develops helps the nurse to better know the patient as a unique individual and choose the most appropriate and efficacious nursing therapies (Hobbs, 2009).

The caring relationships that a nurse develops over time, coupled with the nurse’s growing knowledge and experience, provide a rich source of meaning when changes in a patient’s clinical status occur. Expert nurses develop the ability to detect changes in patients’ conditions almost effortlessly (Benner et al., 2010). Clinical decision making, perhaps the most important responsibility of the professional nurse, involves various aspects of knowing the patient: responses to therapies, routines and habits, coping resources, physical capacities and endurance, and body typology and characteristics. Experienced nurses know additional facts about their patients such as their experiences, behaviors, feelings, and perceptions (Benner et al., 2010; MacDonald, 2008). When you make clinical decisions accurately in the context of knowing a patient well, improved patient outcomes result. When a nurse bases care on knowing a patient, the patient perceives care as personalized, comforting, supportive, and healing.

The most important thing for a beginning nurse to recognize is that knowing a patient is more than simply gathering data about the patient’s clinical signs and condition. Success in knowing the patient lies in the relationship you establish. To know a patient is to enter into a caring, social process, which results in a nurse-patient relationship whereby the patient comes to feel known by the nurse (Bunkers, 2010; MacDonald, 2008).

Spiritual Caring

Spiritual health occurs when a person finds a balance between his or her own life values, goals, and belief systems and those of others (see Chapter 35). Research shows a link between spirit, mind, and body. An individual’s beliefs and expectations have effects on the person’s physical well-being.

Establishing a caring relationship with a patient involves interconnectedness between the nurse and the patient. This interconnectedness is why Watson (2008, 2009, 2010) describes the caring relationship in a spiritual sense. Spirituality offers a sense of connectedness: intrapersonally (connected with oneself), interpersonally (connected with others and the environment), and transpersonally (connected with the unseen, God, or a higher power). In a caring relationship the patient and the nurse come to know one another so both move toward a healing relationship by (Watson, 2008):

• Mobilizing hope for the patient and the nurse.

• Finding an interpretation or understanding of illness, symptoms, or emotions that is acceptable to the patient.

• Assisting the patient in using social, emotional, or spiritual resources.

• Recognizing that caring relationships connect us human to human, spirit to spirit.

Relieving Pain and Suffering

Relieving pain and suffering is more than giving pain medications, repositioning the patient, or cleaning a wound. The relief of pain and suffering encompasses caring nursing actions that give a patient comfort, dignity, respect, and peace. Ensuring that the patient care environment is clean and pleasant and includes personal items makes the physical environment a place that soothes and heals the mind, body, and spirit (Gallagher-Lepak and Kubsch, 2009).

Through skillful and accurate assessment of a patient’s level and type of pain you are able to design patient-centered care to improve the patient’s level of comfort. There are multiple interventions for pain relief, but knowing about the patient and the meaning of his or her pain guides your care (see Chapter 43). Often conveying a quiet caring presence, touching a patient, or listening helps you to assess and understand the meaning of your patient’s pain or discomfort. The caring presence helps you and your patient design goals for pain relief.

Human suffering is multifaceted, affecting a patient physically, emotionally, socially, and spiritually. It also affects the patient’s family and friends. You may find yourself working with a young family whose newborn baby has multiple developmental challenges. Their emotional suffering encompasses anger, guilt, fear, or grief. You cannot fix it, but you can provide comfort through a listening, nonjudgmental caring presence. Patients and their families are comforted by a caring listener (Hudacek, 2008).

Family Care

People live in their worlds in an involved way. Each person experiences life through relationships with others. Thus caring for an individual cannot occur in isolation from that person’s family. As a nurse it is important to know the family almost as thoroughly as you know a patient (Fig. 7-2). The family is an important resource. Success with nursing interventions often depends on their willingness to share information about the patient, their acceptance and understanding of therapies, whether the interventions fit with their daily practices, and whether they support and deliver the therapies recommended.

Families of patients with cancer perceived many nurse caring behaviors to be most helpful (Box 7-3). It is critical that the nurse ensures the patient’s well-being and helps the family members to be active participants. Although specific to families of patients with cancer, these behaviors offer useful guidelines for developing a caring relationship with all families. Begin a relationship by learning who makes up the patient’s family and what their roles are in the patient’s life. Showing the family that you care for and are concerned about the patient creates an openness that then enables a relationship to form with the family. Caring for the family takes into consideration the context of the patient’s illness and the stress it imposes on all members (see Chapter 10).

The Challenge of Caring

Assisting individuals during a time of need is the reason many enter nursing. When nurses are able to affirm themselves as caring individuals, their lives achieve a meaning and purpose (Benner, 2004; Benner et al., 2010). Caring is a motivating force for people to become nurses, and it becomes a source of satisfaction when nurses know that they have made a difference in their patients’ lives.

It is becoming more of a challenge to care in today’s health care system. Being a part of the helping professions is difficult and demanding. Nurses are torn between the human caring model and the task-oriented biomedical model and institutional demands that consume their practice (Watson and Foster, 2003). Nurses have increasingly less time to spend with patients, making it much harder to know who they are. A reliance on technology and cost-effective health care strategies and efforts to standardize and refine work processes all undermine the nature of caring. Too often patients become just a number, with their real needs either overlooked or ignored.

The American Nurses Association (ANA), National League for Nursing (NLN), American Organization of Nurse Executives (AONE), and American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) recommend strategies to reverse the current nursing shortage. A number of these strategies have potential for creating work environments that enable nurses to demonstrate more caring behaviors. Environmental factors promote a more artful nursing and caring presence that further enhances patient-centered care (Finfgeld-Connett, 2008a; Hobbs, 2009). Strategies include introducing greater flexibility into the work environment structure, rewarding experienced nurse mentors, improving nurse staffing, and providing nurses with autonomy over their practice (Brown et al., 2005; Watson, 2009).

If health care is to make a positive difference in their lives, patients cannot be treated like machines or robots. Instead, health care must become more holistic and humanistic. Nurses play an important role in making caring an integral part of health care delivery. This begins by making caring a part of the philosophy and environment in the workplace. Incorporating caring concepts into standards of nursing practice establishes the guidelines for professional conduct. Finally, during day-to-day practice with patients and families, nurses need to be committed to caring and willing to establish the relationships necessary for personal, competent, compassionate, and meaningful nursing care. “Consistent with the wisdom and vision of Nightingale, nursing is a lifetime journey of caring and healing, seeking to understand and preserve the wholeness of human existence and to offer compassionate, informed knowledgeable human caring …” (Watson, 2009).

Key Points

• Caring is the heart of a nurse’s ability to work with people in a respectful and therapeutic way.

• Caring is specific and relational for each nurse-patient encounter.

• For caring to achieve cure, nurses need to learn the culturally specific behaviors and words that reflect human caring in different cultures.

• Because illness is the human experience of loss or dysfunction, any treatment or intervention given without consideration of its meaning to the individual is likely to be worthless.

• Caring involves a mutual give and take that develops as nurse and patient begin to know and care for one another.

• It is difficult to show caring to individuals without gaining an understanding of who they are and their perception of their illness.

• Presence involves a person-to-person encounter that conveys closeness and a sense of caring that involves “being there” and “being with” patients.

• Research shows that touch, both contact and noncontact, includes task-orientated touch, caring touch, and protective touch.

• The skillful and gentle performance of a nursing procedure conveys security and a sense of competence in the nurse.

• Listening is not only “taking in” what a patient says; it also includes interpreting and understanding what the patient is saying and giving back that understanding.

• Knowing the patient is at the core of the process that nurses use to make clinical decisions.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

1. Mrs. Lowe is a 52-year-old patient being treated for lymphoma (cancer of the lymph nodes) that occurred 6 years after a lung transplant. Mrs. Lowe is discouraged about her current health status and has a lot of what she describes as muscle pain. The unit where Mrs. Lowe is receiving care has a number of very sick patients and is short staffed.

a. You enter her room to do a morning assessment and find Mrs. Lowe crying. How are you going to use caring practices to help her, knowing that your day has just begun and you have many nursing interventions to complete?

b. When you listen to Mrs. Lowe, she explains that her muscle pain is very bothersome and it was worse when she was alone. Both you and Mrs. Lowe determine that an injection for her pain would be beneficial. In what way can you show caring in the way you administer the injection to Mrs. Lowe?

c. Mrs. Lowe’s day is getting better. She seems more comfortable and is crying less. You find that your day is more controlled. What else can you do for Mrs. Lowe?

2. During your next clinical practicum, select a patient to talk with for at least 15 to 20 minutes. Ask the patient to tell you about his or her illness. Review the skills of listening in this chapter and in Chapter 24. Immediately after your discussion, reflect on the discussion with the patient and determine if you have enough information about him or her to answer the following questions:

a. What do you believe the patient was trying to tell you about his or her illness?

b. Why was it important for the patient to share his or her story?

c. What did you do that made it easy or difficult for the patient to talk with you? What did you do well? What could you have done better?

d. Would you rate yourself a good listener? How can you listen better?

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. A nurse hears a colleague tell a nursing student that she never touches a patient unless she is performing a procedure or doing an assessment. The nurse tells the student that from a caring perspective:

1. She does not touch the patients either.

2. Touch is a type of verbal communication.

2. Of the five caring processes described by Swanson, which describes “knowing the patient”?

1. Anticipating the patient’s cultural preferences

2. Determining the patient’s physician preference

3. A Muslim woman enters the clinic to have a woman’s health examination for the first time. Which nursing behavior applies Swanson’s caring process of “knowing the patient?”

1. Sharing feelings about the importance of having regular woman’s health examinations

2. Gaining an understanding of what a woman’s health examination means to the patient

3. Recognizing that the patient is modest; obtaining gender-congruent caregiver

4. Helping a new mother through the birthing experience demonstrates which of Swanson’s five caring processes?

5. A patient is fearful of upcoming surgery and a possible cancer diagnosis. He discusses his love for the Bible with his nurse, who recommends a favorite Bible verse. Another nurse tells the patient’s nurse that there is no place in nursing for spiritual caring. The patient’s nurse replies:

1. “Spiritual care should be left to a professional.”

2. “You are correct, religion is a personal decision.”

3. “Nurses should not force their religious beliefs on patients.”

4. “Spiritual, mind, and body connections can affect health.”

6. Which of the following is a strategy for creating work environments that enable nurses to demonstrate more caring behaviors?

1. Increasing the working hours of the staff

2. Increasing salary benefits of the staff

3. Creating a setting that allows flexibility and autonomy for staff

4. Encouraging increased input concerning nursing functions from physicians

7. When a nurse helps a patient find the meaning of cancer by supporting beliefs about life, this is an example of:

8. An example of a nurse caring behavior that families of acutely ill patients perceive as important to patients’ well-being is:

1. Making health care decisions for patients.

2. Having family members provide a patient’s total personal hygiene.

3. Injecting the nurse’s perceptions about the level of care provided.

4. Asking permission before performing a procedure on a patient.

9. A nurse demonstrates caring by helping family members:

1. Become active participants in care.

2. Provide activities of daily living (ADLs).

10. Listening is not only “taking in” what a patient says; it also includes:

1. Incorporating the views of the physician.

2. Correcting any errors in the patient’s understanding.

11. A nurse is caring for an older adult who needs to enter an assisted-living facility following discharge from the hospital. Which of the following is an example of listening that displays caring?

1. The nurse encourages the patient to talk about his concerns while reviewing the computer screen in the room.

2. The nurse sits at the patient’s bedside, listens as he relays his fear of never seeing his home again, and then asks if he wants anything to eat.

3. The nurse listens to the patient’s story while sitting on the side of the bed and then summarizes the story.

4. The nurse listens to the patient talk about his fears of not returning home and then tells him to think positively.

12. Presence involves a person-to-person encounter that:

1. Enables patients to care for self.

2. Provides personal care to a patient.

13. A nurse enters a patient’s room, arranges the supplies for a Foley catheter insertion, and explains the procedure to the patient. She tells the patient what to expect; just before inserting the catheter, she tells the patient to relax and that, once the catheter is in place, she will not feel the bladder pressure. The nurse then proceeds to skillfully insert the Foley catheter. This is an example of what type of touch?

14. A hospice nurse sits at the bedside of a male patient in the final stages of cancer. He and his parents made the decision that he would move home and they would help him in the final stages of his disease. The family participates in his care, but lately the nurse has increased the amount of time she spends with the family. Whenever she enters the room or approaches the patient to give care, she touches his shoulder and tells him that she is present. This is an example of what type of touch?

15. Match the following caring behaviors with their definitions.

Answers: 1. 4; 2. 3; 3. 2; 4. 2; 5. 4; 6. 3; 7. 1; 8. 4; 9. 1; 10. 4; 11. 3; 12. 3; 13. 3; 14. 1; 15. 1 b, 2 c, 3 d, 4 a.

References

American Nurses Association. http://www.nursingworld.org/naf, 2002, [Accessed May 9, 2008].

American Organization of Nurse Executives. Guiding principles for patient care delivery toolkit. http://www.aone.org, 2005. [Accessed July 3, 2011].

Bernick, L. Caring for older adults: practice guided by Watson’s care-healing model. Nurs Sci Q. 2004;17(2):128.

Benner, P. Relational ethics of comfort, touch, solace-endangered arts. Am J Critical Care. 2004;13(4):346.

Benner, P, Wrubel, J. The primacy of caring: stress and coping in health and illness. Menlo Park, Calif: Addison Wesley; 1989.

Benner, P, et al. Educating nurses: a call for radical transformation. Stanford, Calif: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 2010.

Bunkers, SS. The power and possibility in listening. Nurs Sci Quarterly. 2010;23(1):22.

Crocker, C, Scholes, J. The importance of knowing the patient in weaning from mechanical ventilation. Nurs Crit Care. 2009;14(6):289.

Drenkard, KN. Integrating human caring science into a professional nursing practice model. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2008;20:403.

Frank, AW. Just listening: narrative and deep illness. Fam Syst Health. 1998;16(3):197.

Galanti, GA. Caring for patients from different cultures, ed 4. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2008.

Gallagher-Lepak, S, Kubsch, S. Transpersonal caring: a nursing practice guideline. Holisitic Nurs Pract. 2009;23(3):171.

Leininger, MM, Culture care diversity and universality: a theory of nursing. Pub No 15-2402. New York: National League for Nursing Press; 1991.

MacDonald, M. Technology and its effect on knowing the patient: a clinical issue analysis. Clin Nurse Spec. 2008;22(3):149.

Shipley, SD. Listening a: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2010;45(2):125.

Swanson, K. What is known about caring in nursing science. In: Hinshaw AS, et al, eds. Handbook of clinical nursing research. Sherman Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications, 1999.

Watson, J. Caring science as sacred science. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 2005.

Watson, J. Caring theory as an ethical guide to administrative and clinical practices. Nurs Adm Q. 2006;30(1):8.

Watson, J. The philosophy and science of caring. Boulder: University Press of Colorado; 2008.

Watson, J. Caring science and human caring theory: transforming personal and professional practices of nursing and health care. J Health Human Services Admin. 2009;31(4):466.

Watson, J. Caring science and the next decade of holistic healing: transforming self and system from the inside out. Am Holistic Nurses Assoc. 2010;30(2):14.

Zyblock, DM. Nursing presence in contemporary nursing practice. Nurs Forum. 2010;45(2):120.

Research References

Andershed, B, Olsson, K. Review of research related to Kristen Swanson’s middle-range theory of caring. Scand J Caring Sci. 2009;23:598.

Brown, CL, et al. Caring in action: the patient care facilitator role. Int J Human Caring. 2005;9(3):51.

Duffy, JR, Hoskins, L, Seifert, RF. Dimensions of caring: psychometric evaluation of the caring assessment tool. Adv Nurs Sci. 2007;30(3):235.

Finfgeld-Connett, D. Meta-synthesis of caring in nursing. J Clin Nurs. 2006;17:196.

Finfgeld-Connett, D. Qualitative convergence of three nursing concepts: art of nursing, presence, and caring. J Adv Nurs. 2008;63(5):527.

Finfgeld-Connett, D. Qualitative comparison and synthesis of nursing presence and caring. Intl J Nurs Terminol Classifications. 2008;19(3):111.

Fredriksson, L. Modes of relating in a caring conversation: a research synthesis on presence, touch, and listening. J Adv Nurs. 1999;30(5):1167.

Hobbs, JL. A dimensional analysis of patient-centered care. Nurs Res. 2009;58(1):52.

Hudacek, SS. Dimensions of caring: a qualitative analysis of nurses’ stories. J Nurs Educ. 2008;47(3):124.

Osterman, PLC, et al. An exploratory study of nurses’ presence in daily care on an oncology unit. Nurs Forum. 2010;45(3):197.

Radwin, L. Oncology patients’ perceptions of quality nursing care. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(3):179.

Rush, KL, et al. Patient falls: acute care nurses’ experiences. J Clin Nurs. 2008;18:357.

Suliman, WA, et al. Applying Watson’s nursing theory to assess patient perceptions of being cared for in a multicultural environment. J Nurs Res. 2009;17(4):293.

Sumner, J. A critical lens on the instrumentation of caring in nursing theory. Adv Nurs Sci. 2010;33(1):E17.

Swanson, KM. Empirical development of a middle-range theory of caring. Nurs Res. 1991;40(3):161.

Swanson, KM. Effects of caring, measurement, and time on miscarriage impact and women’s well being. Nurs Res. 1999;48(6):288.

Watson, J, Foster, R. The Attending Nurse Caring Model: integrating theory, evidence and advanced caring-healing therapeutics for transforming professional practice. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:360.