Activity and Exercise

• Describe the role of the musculoskeletal and nervous systems in the regulation of movement.

• Discuss physiological and pathological influences on body alignment and joint mobility.

• Describe how to maintain and use proper body mechanics.

• Describe how exercise and activity benefit physiological and psychological functioning.

• Describe the benefits of implementing an exercise program for the purpose of health promotion.

• Describe important factors to consider when planning an exercise program for patients across the life span and for those with specific chronic illnesses.

• Assess patients for impaired mobility and activity intolerance.

• Formulate nursing diagnoses for patients experiencing problems with impaired mobility and activity intolerance.

• Write a nursing care plan for a patient with impaired mobility and activity intolerance.

• Describe interventions for maintaining activity tolerance and mobility.

• Evaluate the nursing care plan for maintaining activity and exercise for patients across the life span and with specific chronic illnesses.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

A program of regular physical activity and exercise has the potential to enhance all aspects of a patient’s biopsychosocial and spiritual model of health. This chapter provides you with knowledge of exercise and activity as they relate to health promotion, the acute phase of illness, and the restorative and continuing care of patients, as well as nursing strategies to help plan an individualized exercise and activity program for a variety of patients with specific disease entities and needs.

Scientific Knowledge Base

Regular physical activity and exercise contribute to both physical and emotional well-being (Edelman and Mandle, 2010; Ferrand et al., 2008). Knowing the physiology and regulation of body mechanics, exercise, and activity helps provide individualized care.

Overview of Exercise and Activity

The coordinated efforts of the musculoskeletal and nervous systems maintain balance, posture, and body alignment during lifting, bending, moving, and performing activities of daily living (ADLs). Proper balance, posture, and body alignment reduce the risk of injury to the musculoskeletal system and facilitate body movements, allowing physical mobility without muscle strain and excessive use of muscle energy.

Body Alignment

Body alignment refers to the relationship of one body part to another along a horizontal or vertical line. Correct alignment involves positioning so no excessive strain is placed on a person’s joints, tendons, ligaments, or muscles, thereby maintaining adequate muscle tone and contributing to balance.

Body Balance

Body balance occurs when a relatively low center of gravity is balanced over a wide, stable base of support and a vertical line falls from the center of gravity through the base of support. When the vertical line from the center of gravity does not fall through the base of support, the body loses balance. Proper posture or a body position that most favors function, requires the least muscular work to maintain, and places the least strain on muscles, ligaments, and bones enhances body balance (Patton and Thibodeau, 2010). Nurses use balance to maintain proper body alignment and posture through two simple techniques. First widen the base of support by separating the feet to a comfortable distance. Second, increase balance by bringing the center of gravity closer to the base of support. For example, you raise the height of the bed when performing a procedure such as changing a dressing to prevent bending too far at the waist and shifting the base of support.

Coordinated Body Movement

Coordinated body movement is a result of weight, center of gravity, and balance. Weight is the force exerted on a body by gravity. When an object is lifted, the lifter must overcome the weight of the object and be aware of the center of gravity of the object. In symmetrical objects the center of gravity is located at the exact center of the object. The force of weight is always directed downward. An unbalanced object has its center of gravity away from the midline and falls without support. Because people are not geometrically perfect, their centers of gravity are usually midline, at 55% to 57% of standing height. Like unbalanced objects, patients who are unsteady do not maintain a balance with their center of gravity, which places them at risk for falling. You need to be able to identify these patients and intervene to maintain their safety.

Friction

Friction is a force that occurs in a direction to oppose movement. Reduce friction by following some basic principles. When you move objects, those with a greater surface area create more friction. To reduce friction, you need to decrease the object’s surface area. For example, when helping patients move up in bed, place their arms across the chest. This decreases surface area and reduces friction.

A patient who is passive or immobilized produces greater friction to movement (see Chapter 47). When possible, use some of your patients’ strength and mobility when positioning and transferring them. Explain the procedure and tell your patients when to move. You decrease friction when your patients bend their knees as you help them move up in the bed.

You can also reduce friction by using an air-assisted device when performing lateral patient transfers (Baptiste et al., 2006). Air-assisted devices are commercially available transfer devices that are effective solutions to reducing injury to health care employees and patients.

Exercise and Activity

Exercise is physical activity used to condition the body, improve health, and maintain fitness. Sometimes exercise is also a therapeutic measure. A patient’s individualized exercise program depends on the patient’s activity tolerance or the type and amount of exercise or activity that the patient is able to perform. Physiological, emotional, and developmental factors influence the patient’s activity tolerance.

An active lifestyle is important for maintaining and promoting health; it is also an essential treatment for chronic illnesses (Perez et al., 2009). Regular physical activity and exercise enhance functioning of all body systems, including cardiopulmonary functioning (endurance), musculoskeletal fitness (flexibility and bone integrity), weight control and maintenance (body image), and psychological well-being (ACSM, 2007; Edelman and Mandle, 2010).

The best program of physical activity includes a combination of exercises that produces different physiological and psychological benefits. Three categories of exercise are isotonic, isometric, and resistive isometric. The type of muscle contraction involved determines the classification of the exercise. Isotonic exercises cause muscle contraction and change in muscle length (isotonic contraction). Examples are walking, swimming, dance aerobics, jogging, bicycling, and moving arms and legs with light resistance. Isotonic exercises enhance circulatory and respiratory functioning; increase muscle mass, tone, and strength; and promote osteoblastic activity (activity by bone-forming cells), thus combating osteoporosis.

Isometric exercises involve tightening or tensing muscles without moving body parts (isometric contraction). Examples are quadriceps set exercises and contraction of the gluteal muscles. This form of exercise is ideal for patients who do not tolerate increased activity. A patient who is immobilized in bed can perform isometric exercises. The benefits are increased muscle mass, tone, and strength, thus decreasing the potential for muscle wasting; increased circulation to the involved body part; and increased osteoblastic activity.

Resistive isometric exercises are those in which the individual contracts the muscle while pushing against a stationary object or resisting the movement of an object (Hoeman, 2006). A gradual increase in the amount of resistance and length of time that the muscle contraction is held increases muscle strength and endurance. Examples of resistive isometric exercises are push-ups and hip lifting, in which a patient in a sitting position pushes with the hands against a surface such as a chair seat and raises the hips. In some long-term care settings, footboards are placed on the end of beds; patients push against them to move up in bed. Resistive isometric exercises help promote muscle strength and provide sufficient stress against bone to promote osteoblastic activity.

Regulation of Movement

Coordinated body movement involves the integrated functioning of the skeletal, muscular, and nervous systems. Because these three systems cooperate so closely in mechanical support of the body, they are often considered as a single functional unit.

Skeletal System

Bones perform five functions in the body: support, protection, movement, mineral storage, and hematopoiesis (blood cell formation). In the discussion of body mechanics, two of these functions (i.e., support and movement) are most important (see Chapter 47). Bones serve as support by providing the framework and contributing to the shape, alignment, and positioning of the body parts. Bones, together with their joints, constitute levers for muscle attachment to provide movement. As muscles contract and shorten, they pull on bones, producing joint movement (Patton and Thibodeau, 2010).

Joints: An articulation, or joint, is the connection between bones. Each joint is classified according to its structure and degree of mobility. On the basis of connective structures, joints are classified as fibrous, cartilaginous, or synovial (Huether and McCance, 2008). Fibrous joints fit closely together and are fixed, permitting little, if any, movement such as the syndesmosis between the tibia and fibula. Cartilaginous joints have little movement but are elastic and use cartilage to unite separate body surfaces such as the synchondrosis that attaches the ribs to the costal cartilage. Synovial joints, or true joints, such as the hinge type at the elbow, are freely movable and the most mobile, numerous, and anatomically complex body joints.

Ligaments, Tendons, and Cartilage: Ligaments, tendons, and cartilage support the skeletal system (see Chapter 47). Ligaments are white, shiny, flexible bands of fibrous tissue that bind joints and connect bones and cartilage. They are elastic and aid joint flexibility and support. Tendons are white, glistening, fibrous bands of tissue that connect muscle to bone. Cartilage is nonvascular, supporting connective tissue with the flexibility of a firm, plastic material. Because of its gristle-like nature, cartilage sustains weight and serves as a shock absorber between articulating bones.

Skeletal Muscle

Contraction of skeletal muscles allows people to walk, talk, run, breathe, or participate in physical activity. There are more than 600 skeletal muscles in the body. In addition to facilitating movement, these muscles determine the form and contour of our bodies. Most of our muscles span at least one joint and attach to both articulating bones. When contraction occurs, one bone is fixed while the other moves. The origin is the point of attachment that remains still; the insertion is the point that moves when the muscle contracts (Patton and Thibodeau, 2010).

Muscles Concerned with Movement: The muscles of movement are located near the skeletal region, where a lever system causes movement (Patton and Thibodeau, 2010). The lever system makes the work of moving a weight or load easier. It occurs when specific bones such as the humerus, ulna, and radius and the associated joints such as the elbow act as a lever. Thus the force applied to one end of the bone to lift a weight at another point tends to rotate the bone in the direction opposite that of the applied force. Muscles that attach to bones of leverage provide the necessary strength to move the object.

Muscles Concerned with Posture: Gravity continually pulls on parts of the body; the only way the body is held in position is for muscles to pull on bones in the opposite direction. Muscles accomplish this counterforce by maintaining a low level of sustained contraction. Poor posture places more work on muscles to counteract the force of gravity. This leads to fatigue and eventually interferes with bodily functions and causes deformities.

Muscle Groups: The nervous system coordinates the antagonistic, synergistic, and antigravity muscle groups that are responsible for maintaining posture and initiating movement. Antagonistic muscles cause movement at the joint. During movement the active mover muscle contracts while its antagonist relaxes. For example, during flexion of the arm the active mover, the biceps brachii, contracts; and its antagonist, the triceps brachii, relaxes. During extension of the arm the active mover, now the triceps brachii, contracts; and the new antagonist, the biceps brachii, relaxes.

Synergistic muscles contract to accomplish the same movement. When the arm is flexed, the strength of the contraction of the biceps brachii is increased by contraction of the synergistic muscle, the brachialis. Thus with synergistic muscle activity there are now two active movers (i.e., the biceps brachii and the brachialis), which contract while the antagonistic muscle, the triceps brachii, relaxes.

Antigravity muscles stabilize joints. These muscles continuously oppose the effect of gravity on the body and permit a person to maintain an upright or sitting posture. In an adult the antigravity muscles are the extensors of the leg, the gluteus maximus, the quadriceps femoris, the soleus muscles, and the muscles of the back.

Skeletal muscles support posture and carry out voluntary movement. The muscles are attached to the skeleton by tendons, which provide strength and permit motion. The movement of the extremities is voluntary and requires coordination from the nervous system.

Nervous System

The nervous system regulates movement and posture. The major voluntary motor area, located in the cerebral cortex, is the precentral gyrus, or motor strip. A majority of motor fibers descend from the motor strip and cross at the level of the medulla. Thus the motor fibers from the right motor strip initiate voluntary movement for the left side of the body, and motor fibers from the left motor strip initiate voluntary movement for the right side of the body.

Transmission of the impulse from the nervous system to the musculoskeletal system is an electrochemical event and requires a neurotransmitter. Basically neurotransmitters are chemicals (e.g., acetylcholine) that transfer the electrical impulse from the nerve across the myoneural junction to stimulate the muscle, causing movement. Several disorders impair movement. For example, Parkinson’s disease alters neurotransmitter production, myasthenia gravis disrupts transfer from the neurotransmitter to the muscle, and multiple sclerosis impairs muscle activity (Huether and McCance, 2008).

Proprioception: Proprioception is the awareness of the position of the body and its parts (Huether and McCance, 2008). Proprioceptors located on nerve endings in muscles, tendons, and joints monitor proprioception. The nervous system regulates posture, which requires coordination of proprioception and balance. As a person carries out ADLs, proprioceptors monitor muscle activity and body position. For example, the proprioceptors on the soles of the feet contribute to correct posture while standing or walking. In standing, pressure is continuous on the bottom of the feet. The proprioceptors monitor the pressure, communicating this information through the nervous system to the antigravity muscles. The standing person remains upright until deciding to change position. As a person walks, the proprioceptors on the bottom of the feet monitor pressure changes. Thus, when the bottom of the moving foot comes in contact with the walking surface, the individual automatically moves the stationary foot forward.

Balance: A person needs adequate balance to stand, run, lift, or perform ADLs. The nervous system controls balance specifically through the cerebellum and the inner ear. The cerebellum coordinates all voluntary movement, particularly highly skilled movements such as those required in skiing.

Within the inner ear are the semicircular canals, three fluid-filled structures that help maintain balance. Fluid within the canals has a certain inertia; when the head is suddenly rotated in one direction, the fluid remains stationary for a moment, but the canal turns with the head. This allows a person to change position suddenly without losing balance.

Principles of Transfer and Positioning Techniques

Using principles of safe patient transfer and positioning during routine activities decreases work effort (Box 38-1). Teach colleagues and patients’ families how to transfer or position patients properly. Teaching a patient’s family to transfer the patient from bed to chair increases and reinforces the family’s knowledge about proper transfer and position techniques.

Whether you are moving a patient who is immobile, assisting a patient from the bed to the chair, or teaching a patient to carry out ADLs efficiently, knowledge of safe patient transfer and positioning is crucial. You also incorporate knowledge of physiological and pathological influences on body alignment and mobility.

Pathological Influences on Body Alignment and Mobility

Many pathological conditions affect body alignment and mobility. These conditions include congenital defects; disorders of bones, joints, and muscles; central nervous system damage; and musculoskeletal trauma.

Congenital Defects: Congenital abnormalities affect the efficiency of the musculoskeletal system in regard to alignment, balance, and appearance. Osteogenesis imperfecta is an inherited disorder that affects bone. Bones are porous, short, bowed, and deformed; as a result, children experience curvature of the spine and shortness of stature. Scoliosis is a structural curvature of the spine associated with vertebral rotation. Muscles, ligaments, and other soft tissues become shortened. Balance and mobility are affected in proportion to the severity of abnormal spinal curvatures (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Disorders of Bones, Joints, and Muscles: Osteoporosis, a well-known and well-publicized disorder of aging, results in the reduction of bone density or mass. The bone remains biochemically normal but has difficulty maintaining integrity and support. The cause is uncertain, and theories vary from hormonal imbalances to insufficient intake of nutrients (Huether and McCance, 2008).

Osteomalacia is an uncommon metabolic disease characterized by inadequate and delayed mineralization, resulting in compact and spongy bone (Lewis et al., 2011). Mineral calcification and deposition do not occur. Replaced bone consists of soft material rather than rigid bone.

Joint mobility is altered by inflammatory and noninflammatory joint diseases and articular disruption. Inflammatory joint disease (e.g., arthritis) is characterized by inflammation or destruction of the synovial membrane and articular cartilage and by systemic signs of inflammation. Noninflammatory diseases have none of these characteristics, and the synovial fluid is normal (Huether and McCance, 2008). Joint degeneration, which can occur with inflammatory and noninflammatory disease, is marked by changes in articular cartilage combined with overgrowth of bone at the articular ends. Degenerative changes commonly affect weight-bearing joints.

Articular disruption involves trauma to the articular capsules and ranges from mild, such as a tear resulting in a sprain, to severe, such as a separation leading to dislocation. Articular disruption usually results from trauma but sometimes is congenital, as with developmental dysplasia of the hip (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Central Nervous System Damage: Damage to any part of the central nervous system that regulates voluntary movement causes impaired body alignment and immobility. For example, a patient with a traumatic head injury experiences damage in the motor strip in the cerebrum. The amount of voluntary motor impairment is directly related to the amount of destruction of the motor strip. For example, a patient with a right-sided cerebral hemorrhage and permanent damage to the right motor strip has left-sided hemiplegia, whereas a patient with a right-sided head injury experiences cerebral edema around (but not destruction of) the motor strip. The patient with hemiplegia does not regain movement, whereas the second patient’s voluntary movement gradually returns to the left side following extensive physical therapy.

Musculoskeletal Trauma: Musculoskeletal trauma often results in bruises, contusions, sprains, and fractures. A fracture is a disruption of bone tissue continuity. Fractures most commonly result from direct external trauma. They also occur because of some deformity of the bone (e.g., with pathological fractures of osteoporosis) (see Chapter 47).

Nursing Knowledge Base

Application of nursing knowledge allows you to think critically about the holistic needs of patients. Nursing knowledge as it pertains to activity and exercise helps you assess, identify, and intervene when patients have decreased activity tolerance or physical limitation that affects their ability to exercise.

Factors Influencing Activity and Exercise

Factors influencing activity and exercise include developmental changes, behavioral aspects, family and social support, cultural and ethnic origin, and environmental issues. Consider these areas of knowledge and incorporate into the plan of care whether the patient is seeking health promotion, acute care, or restorative and continuing care.

Developmental Changes

Throughout the life span the appearance and functioning of the body undergo change. The greatest change and effect on the maturational process occurs in childhood and old age.

Infants Through School-Age Children: The newborn infant’s spine is flexed and lacks the anteroposterior curves of the adult. The first spinal curve occurs when the infant extends the neck from the prone position. As growth and stability increase, the thoracic spine straightens, and the lumbar spinal curve appears, which allows sitting and standing.

The toddler’s posture is awkward because of the slight swayback and protruding abdomen. As the child walks, the legs and feet are usually far apart, and the feet are slightly everted (turned outward). Toward the end of toddlerhood, posture appears less awkward, curves in the cervical and lumbar vertebrae are accentuated, and foot eversion disappears.

By the third year the body is slimmer, taller, and better balanced. Abdominal protrusion decreases, the feet are not as far apart, and the arms and legs have increased in length. The child appears more coordinated. From the third year through the beginning of adolescence, the musculoskeletal system continues to grow and develop (see Chapter 12).

Adolescence: The period of adolescence usually begins with a tremendous growth spurt. Growth is frequently uneven. As a result, the adolescent appears awkward and uncoordinated. Adolescent girls usually grow and develop earlier than boys. Hips widen; and fat deposits in the upper arms, thighs, and buttocks. The adolescent boy’s changes in shape are usually a result of long-bone growth and increased muscle mass (see Chapter 12).

Young to Middle Adults: An adult with correct posture and body alignment feels good, looks good, and generally appears self-confident. The healthy adult also has the necessary musculoskeletal development and coordination to carry out ADLs (see Chapter 13). Normal changes in posture and body alignment in adulthood occur mainly in pregnant women. These changes result from the adaptive response of the body to weight gain and the growing fetus. The center of gravity shifts toward the anterior. The pregnant woman leans back and is slightly swaybacked; as a result, pregnant women often complain of back pain.

Older Adults: A progressive loss of total bone mass occurs with the older adult. Some of the possible causes of this loss include physical inactivity, hormonal changes, and increased osteoclastic activity (i.e., activity by cells responsible for bone tissue absorption). The effect of bone loss is weaker bones, causing vertebrae to be softer and long shaft bones to be less resistant to bending.

In addition, older adults may walk more slowly and appear less coordinated. They often take smaller steps and keep their feet closer together, which decreases the base of support. Thus body balance is unstable, and they are at greater risk for falls and injuries (see Chapter 14).

Behavioral Aspects

Patients are more likely to incorporate an exercise program into their daily lives if supported by family, friends, nurses, health care providers, and other members of the health care team. The nurse takes into consideration the patient’s knowledge of exercise and activity, barriers to a program of exercise and physical activity, and current exercise habits. Patients are more open to developing an exercise program when they are at a stage of readiness to change their behavior (Prochaska, Norcross, and DiClemente, 1994). Information about the benefits of regular exercise is often helpful to the patient who is not at the stage of readiness to act. Patients’ decisions to change behavior and include a daily exercise routine in their lives sometimes occur gradually with repeated information individualized to patients’ needs and lifestyle (Box 38-2). Once the patient is at the stage of readiness, collaborate with him or her to develop an exercise program that fits his or her needs and provide continued follow-up support and assistance until the exercise program becomes a daily routine.

Environmental Issues

Work Site: A common barrier for many patients is the lack of time needed to engage in a daily exercise program. Some work sites help their employees overcome the obstacle of time constraints by offering opportunities, reminders, and rewards for those committed to physical fitness (Kuoppala, Lamminpää, and Husman, 2008). Reminders such as signs that encourage employees to use the stairs instead of elevators are useful. Rewards such as free parking or discounted parking fees are also effective for employees who park in distant lots and walk.

Schools: Children today are less active, resulting in an increase in childhood obesity (Harper, 2006; Ward et al., 2010). Schools are excellent facilitators of physical fitness and exercise. Strategies for physical activity incorporated early into a child’s daily routine often provide a foundation for lifetime commitment to exercise and physical fitness.

Community: Community support of physical fitness is instrumental in promoting the health of its members (e.g., providing walking trails and track facilities in parks and physical fitness classes). Success in implementing physical fitness programs depends on a collaborative effort from public health agencies, parks and recreational associations, state and local government agencies, health care agencies, and the members of the community (Bors et al., 2009; Harper, 2006).

Cultural and Ethnic Influences

Exercise and physical fitness are beneficial to all people. When developing a physical fitness program for culturally diverse populations, consider what motivates them and what they see as appropriate and enjoyable. It is also important to know which specific disease entities are associated with different cultural and ethnic origins (Box 38-3).

Family and Social Support

Social support is one motivational tool to encourage and promote exercise and physical fitness. For example, a patient engages a friend or significant other to participate in a “buddy system” where they walk together each day at a specified time. This companionship provides for socialization, increases the enjoyment, and develops a lifelong commitment to physical fitness. Parents support their children in sports and physical activity by providing encouragement, praise, and transportation (Davison and Jago, 2010; Dunton, 2010). Other parents support physical activity by including their children in family outings such as bicycling or a basketball game in the neighborhood schoolyard.

Critical Thinking

Successful critical thinking requires a synthesis of knowledge, experience, information gathered from patients, critical thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. Patients’ conditions are always changing. Clinical judgments require you to anticipate the necessary information, analyze the data, and make decisions regarding patient care.

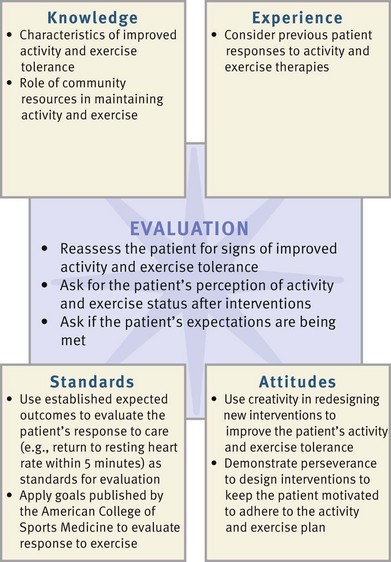

To understand activity tolerance, physical fitness, and the effect on the patient, you integrate knowledge from nursing and other disciplines, previous experiences, and information gathered from patients. As you plan patient care, consider the relationship among a variety of concepts to provide the best outcome for the patient. For example, you lay the foundation for planning and decision making by understanding the relationship between the musculoskeletal system and health alterations that create problems with activity and exercise, positioning, and transferring. Professional standards such as those developed by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) (2007) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) (2007) provide valuable guidelines for exercise and physical fitness. In addition, using the recommendations from the American Nurses Association (ANA) (2008) reduces the risk for work-related musculoskeletal disorders.

Any acquired or congenital condition that affects the structure of the musculoskeletal or nervous system impairs activity, body alignment, or joint mobility to some degree. The impairment is sometimes temporary, such as casting of an extremity, or is permanent, such as a contracture. For patients with limited range of motion (ROM) or mobility, the nursing care plan needs to include interventions that maintain the present level of alignment and joint mobility and increase the level of motor function.

Your experiences and critical thinking attitude affect the problem-solving approach with patients and are evaluated with each new patient. Remember that some patients have the capacity for recovery in spite of the loss of some physical function. Restoration of function begins early in the care of patients whose ability to perform self-care is disrupted. Encouragement, support, commitment, and perseverance are important attitudes in critical thinking for these patients.

Perseverance is necessary when caring for patients who depend on you for assistance with positioning, turning, or ambulation. Hourly responsibility for turning often becomes repetitive, and some nurses lose sight of its importance. Perseverance is especially important in delegating these activities to other personnel. Making certain that the task is performed correctly is an essential nursing function. Problems with activity and mobility are often prolonged; creativity is necessary when designing interventions for improving activity tolerance and mobility skills.

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care.

Assessment

During the assessment process, you thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care. Complete the assessment of body alignment and posture with the patient standing, sitting, or lying down. Use assessment to determine normal physiological changes in growth and development; deviations related to poor posture, trauma, muscle damage, or nerve dysfunction; and any learning needs of patients. In addition, provide opportunities for patients to observe their posture and obtain important information about other factors that contribute to poor alignment such as inactivity, fatigue, malnutrition, and psychological problems. Ask questions related to the patient’s exercise and activity tolerance to gather important information (Box 38-4). During assessment (Fig. 38-1) consider all of the elements that help you make appropriate nursing diagnoses. The first step in assessing body alignment is to put the patient at ease so he or she does not assume unnatural or rigid positions. When assessing body alignment of a patient who is immobilized or unconscious, remove pillows from the bed if not contraindicated and place the patient in the supine position.

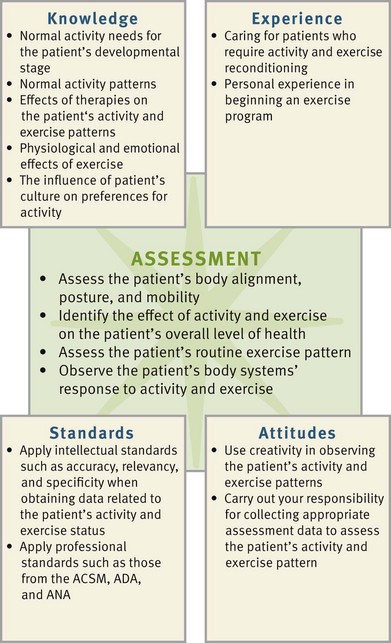

FIG. 38-1 Critical thinking model for activity and exercise assessment. ACSM, American College of Sports Medicine; ADA, American Diabetes Association; ANA, American Nurses Association.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

In patient-centered care, assessing the patient’s expectations concerning activity and exercise and determining individual perceptions of what is normal or acceptable is of utmost importance in developing a plan of care. For example, one of the factors affecting physical activity is freedom from pain. When patients experience pain or fatigue following exercise, they often lack commitment to desired interventions. When patients are content with their present physical activity and fitness, they do not perceive a need for improvement.

Standing

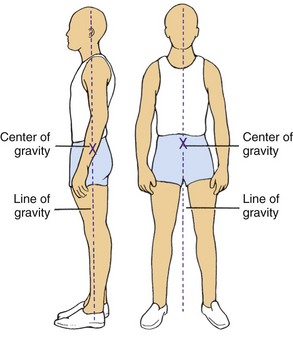

Assessment of the standing patient includes the following: the head is erect and midline, body parts are symmetrical, the spine is straight with normal curvatures (cervical concave, thoracic convex, lumbar concave), the abdomen is comfortably tucked, the knees are in a straight line between the hips and ankles and slightly flexed, the feet are flat on the floor and pointed directly forward and slightly apart to maintain a wide base of support, and the arms hang comfortably at the sides (Fig. 38-2). The patient’s center of gravity is in the midline, and the line of gravity is from the middle of the forehead to a midpoint between the feet. Laterally the line of gravity runs vertically from the middle of the skull to the posterior third of the foot (Wilson and Giddens, 2009).

Sitting

Assessment of the patient in the sitting position includes the following: the head is erect, and the neck and vertebral column are in straight alignment; the body weight is distributed on the buttocks and thighs; the thighs are parallel and in a horizontal plane (be careful to avoid pressure on the popliteal nerve and blood supply); the feet are supported on the floor; and the forearms are supported on the armrest, in the lap, or on a table in front of the chair.

Assessment of alignment in the sitting position is particularly important for the patient with muscle weakness, muscle paralysis, or nerve damage. A patient with these alterations has diminished sensation in affected areas and is unable to perceive pressure or decreased circulation. Proper sitting alignment reduces the risk of musculoskeletal system damage.

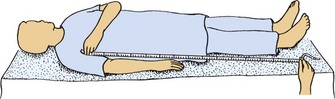

Recumbent Position

When assessing the patient in the recumbent position, you place the patient in the lateral position, removing all positioning supports and all but one pillow. The vertebrae are in straight alignment without observable curves. This assessment provides baseline data concerning the patient’s body alignment.

Conditions that create a risk of damage to the musculoskeletal system when lying down include impaired mobility (e.g., traction), decreased sensation (e.g., hemiparesis from a stroke), impaired circulation (e.g., diabetes), and lack of voluntary muscle control (e.g., spinal cord injuries).

When a patient is unable to change position voluntarily, assess the position of body parts while the patient is lying down. Make sure that the vertebrae are in straight alignment without any observable curves. Also check that the extremities are in alignment and not crossed over one another. The head and neck need to be aligned without excessive flexion or extension.

Mobility

Assessment of mobility helps to determine the patient’s coordination and balance while walking, the ability to carry out ADLs, and the ability to participate in an exercise program. The assessment of mobility has three components: ROM, gait, and exercise.

Range of Motion: Assessing ROM is one assessment technique used to determine the degree of damage or injury to a joint (see Chapter 47). By measuring the ROM of a joint you are able to answer questions about joint stiffness, swelling, pain, limited movement, and unequal movement. Limited ROM often indicates inflammation such as arthritis, fluid in the joint, altered nerve supply, or contractures. Increased mobility (beyond normal) of a joint sometimes indicates connective tissue disorders, ligament tears, or possible joint fractures.

Gait: Gait is the manner or style of walking, including rhythm, cadence, and speed. Assessing gait allows you to draw conclusions about balance, posture, and the ability to walk without assistance. Assessment findings in patients with normal gait include a regular, smooth rhythm; symmetry in the length of leg swing; smooth swaying related to the gait phase; and a smooth, symmetrical arm swing (Wilson and Giddens, 2009).

Exercise: Exercise conditions the body, improves health, maintains fitness, and provides therapy for correcting a deformity or restoring the overall body to a maximal state of health. When a person engages in physical activity, physiological changes occur in body systems (Box 38-5). Determine how much the patient exercises regularly.

Activity Tolerance

Activity tolerance is the kind and amount of exercise or activity that a person is able to perform. Assessment of activity tolerance is necessary when planning physical activity for health promotion and for patients with acute or chronic illness. This assessment provides baseline data about the patient’s activity patterns and helps determine which factors (physical, psychological, or motivational) affect activity tolerance (Box 38-6).

Nursing Diagnosis

Assessment of the patient’s activity tolerance, physical fitness, body alignment, and joint mobility provides clusters of data or defining characteristics to support a nursing diagnosis. You need to be accurate when identifying diagnoses. For example, you consider nursing diagnoses of activity intolerance or fatigue in a patient who reports being tired and weak. Further review of assessed defining characteristics (e.g., abnormal heart rate and dyspnea) leads to the definitive diagnosis (activity intolerance).

When patients have problems with activity and exercise, nursing diagnoses often focus on the ability to move. The diagnostic label and related factors direct nursing interventions. This requires the correct selection of the related factors. For example, activity intolerance related to excess weight gain requires very different interventions than if the related factor is prolonged bed rest. Box 38-7 provides an example of how the diagnostic process leads to accurate diagnosis selection. The following are examples of nursing diagnoses related to activity and exercise:

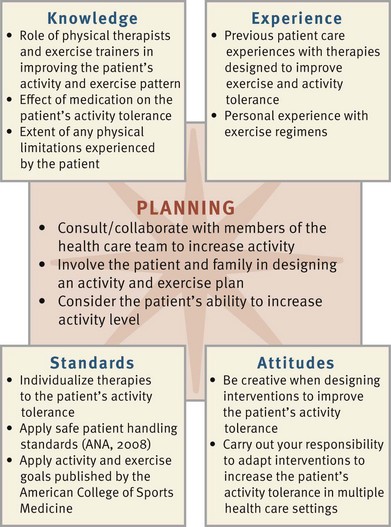

Planning

During planning synthesize information from multiple resources (Fig. 38-3). Critical thinking ensures that the patient’s plan of care integrates all patient information. Professional standards are especially important to consider when developing a plan of care. These standards often establish scientifically proven guidelines for selecting effective nursing interventions.

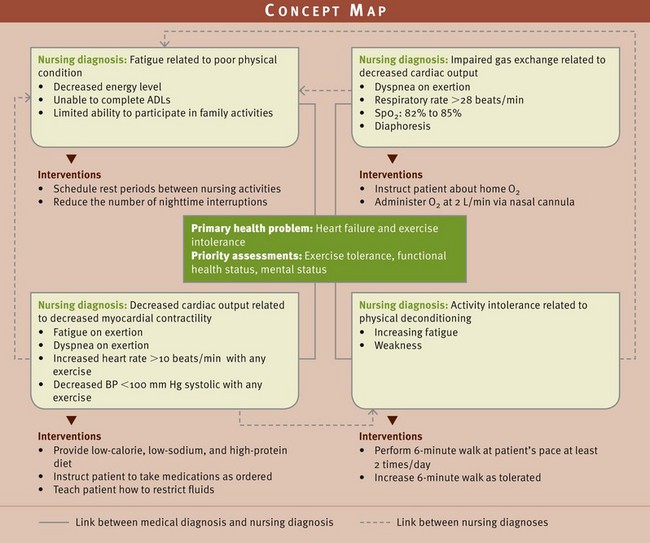

Concept maps are a tool to assist in the planning of care. Fig. 38-4 shows the relationship between a patient’s medical diagnosis of heart failure and the identified nursing diagnosis.

Goals and Outcomes

Once you identify the nursing diagnoses, you and the patient set goals and expected outcomes to direct interventions. The plan includes consideration of any risks for injury to the patient and preexisting health concerns. It is especially important to have knowledge of the patient’s home environment when planning therapies to maintain or improve activity, body alignment, and mobility. Include the patient’s family in the care plan. For some patients with alterations in joint mobility, family members may be caregivers. The general goal related to exercise and activity is to improve or maintain the patient’s motor function and independence. The following are examples of outcomes for patients with deficits in activity and exercise (Ackley and Ladwig, 2008):

Setting Priorities

Care planning is patient centered, taking into consideration the patient’s most immediate needs. You determine the immediacy of any problem by the effect of the problem on the patient’s mental and physical health. Because of the many skills associated with the care of patients with activity intolerance; improper body mechanics; and/or impaired mobility such as turning, transferring, and positioning, it is easy to overlook the complications associated with these health alterations. Therefore be vigilant in monitoring the patient and supervising assistive personnel in carrying out activities to prevent complications and potential injury.

Teamwork and Collaboration

Planning involves understanding the patient’s need to maintain function and independence. For example, it is important to collaborate with physical and occupational therapists. Sometimes long-term rehabilitation is necessary. Discharge planning begins when a patient enters the health care system. In addition, always individualize a plan of care directed at meeting the actual or potential needs of the patient (see the Nursing Care Plan).

Implementation

A sedentary lifestyle contributes to the development of health-related problems. You promote health by encouraging patients to engage in a regular exercise program (Box 38-8). Take a holistic approach to develop and implement a plan that enhances the patient’s overall physical fitness. Discuss recommendations for physical activity and fitness and collaborate with the patient to design a program of exercise.

Before starting an exercise program, teach patients to calculate their maximum heart rate by subtracting their current age in years from 220 and then obtaining their target heart rate by taking 60% to 90% of the maximum, depending on their health care provider’s recommendation. No matter which exercise prescription is implemented for the patient, a warm-up and cool-down period needs to be included in the program (Edelman and Mandle, 2010). The warm-up period usually lasts about 5 to 10 minutes and frequently includes stretching, calisthenics, and/or the aerobic activity performed at a lower intensity. It prepares the body and decreases the potential for injury. The cool-down period follows the exercise routine and usually lasts about 5 to 10 minutes. It allows the body to readjust gradually to baseline functioning and provides an opportunity to combine movement such as stretching with relaxation-enhancing mind-body awareness.

Many patients find it difficult to incorporate an exercise program into their daily lives because of time constraints. For these patients it is beneficial to reinforce that they can use ADLs to accumulate the recommended 30 minutes or more per day of moderate-intensity physical activity (Box 38-9).

Other patients benefit from a prescribed exercise and physical fitness program carefully designed to meet their needs and expectations. An exercise prescription usually includes a combination of aerobic exercises, stretching and flexibility exercises, and resistance training. Aerobic exercise includes walking, running, bicycling, aerobic dance, jumping rope, and cross-country skiing. Recommended frequency of aerobic exercise is 3 to 5 times per week or every other day for approximately 30 minutes. Cross-training is recommended for the patient who prefers to exercise every day. For example, the patient runs one day and does yoga the next day.

Stretching and flexibility exercises include active ROM and stretch all muscle groups and joints. This form of exercise is ideal for warm-up and cool-down periods. Benefits include increased flexibility, improved circulation and posture, and an opportunity for relaxation.

Resistance training increases muscle strength and endurance and is associated with improved performance of daily activities and avoidance of injuries and disability. Formal resistance training includes weight training; but patients can obtain the same benefits by performing ADLs such as pushing a vacuum cleaner, raking leaves, shoveling snow, and kneading bread. Some patients use weight training to bulk up their muscles. However, the purpose of weight training from a health perspective is to develop tone and strength and stimulate and maintain healthy bone (O’Donovan et al., 2010).

Body Mechanics: The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration released federal ergonomic guidelines to prevent musculoskeletal injuries in the workplace (OSHA, 2009). Half of all back pain is associated with manual lifting tasks (Box 38-10). Coordinated musculoskeletal activity is necessary when positioning and transferring patients. The most common back injury is strain on the lumbar muscle group, which includes the muscles around the lumbar vertebrae. Injury to these areas affects the ability to bend forward, backward, and from side to side. The ability to rotate the hips and lower back is also decreased (Nelson and Hughes, 2009). Body mechanics alone are not sufficient to prevent musculoskeletal injuries when positioning or transferring patients (Table 38-1).

TABLE 38-1

PREVENTING LIFT INJURIES IN HEALTH CARE WORKERS

| ACTION | RATIONALE |

| When planning to move a patient, arrange for adequate help. If your institution has a lift team, use it as a resource. | A lift team is properly educated in techniques to prevent musculoskeletal injuries. |

| Use patient-handling equipment and devices such as height-adjustable beds, ceiling-mounted lifts, friction-reducing slide sheets, and air-assisted devices (Nelson and Baptiste, 2004; Nelson and Hughes, 2009; Tullar et al., 2010). | These devices reduce the caregiver’s muscular strain during patient handling. |

| Encourage patient to assist as much as possible. | This promotes patient’s independence and strength while minimizing workload. |

| Keep back, neck, pelvis, and feet aligned. Avoid twisting. | Reduces risk of injury to lumbar vertebrae and muscle groups. Twisting increases risk of injury. |

| Flex knees; keep feet wide apart. | A broad base of support increases stability. |

| Position self close to patient (or object being lifted). | Reduces horizontal reach and stress on caregiver’s back. |

| Use arms and legs (not back). | The leg muscles are stronger, larger muscles capable of greater work without injury. |

| Slide patient toward your body using a pull sheet or slide board. When transferring a patient onto a stretcher or bed, a slide board is more appropriate. | Sliding requires less effort than lifting. Pull sheet minimizes shearing forces, which can damage patient’s skin. |

| Person with the heaviest load coordinates efforts of team involved by counting to three. | Simultaneous lifting minimizes the load for any one lifter. |

| Perform manual lifting as last resort and only if it does not involve lifting most or all of patient’s weight (Nelson and Baptiste, 2004; Nelson and Hughes, 2009; Tullar, 2010). | Lifting is a high-risk activity that causes significant biochemical and postural stressors. |

Before lifting, assess the weight to be lifted, determine the assistance needed, and evaluate available resources. Use safe patient-handling equipment when the patient is unable to assist in transfer. Lift teams, consisting of two physically fit people competent in lifting techniques, reduce the risk of injury to the patient and members of the health care team (Baptiste et al., 2006; Pelczarski, 2007). Use manual lifting only as a last resort when you need to lift a small portion of the patient’s weight (Nelson and Baptiste, 2004; Nelson et al., 2008; Tullar et al., 2010). Teaching health care workers about patient-handling equipment, proper body mechanics, and the use of lift teams is most effective in preventing injury (Nelson and Baptiste, 2004; Nelson et al., 2008).

Acute Care

Encourage patients who are hospitalized to do stretching and isometric exercises, active ROM exercises, and low-intensity walking, depending on their condition. When patients cannot participate in active ROM, maintain joint mobility and prevent contractures by implementing passive ROM into the plan of care. If needed, medicate patients for pain 30 minutes before exercise.

Musculoskeletal System: Help maintain the musculoskeletal system during acute care by encouraging the use of stretching and isometric exercises. Review the patient’s chart and collaborate with the health care provider to identify possible contraindications before initiating isometric exercises. You design an isometric exercise program for the specific needs of a patient. For example, an exercise program includes isometric exercises of the biceps and triceps to prepare your patient for crutch walking. Instruct the patient to stop the activity if pain, fatigue, or discomfort is experienced.

Generally the muscle group is tightened (contracted) for 10 seconds and then completely relaxed for several seconds (Hoeman, 2006). Repetitions are gradually increased for each muscle group until the isometric exercise is repeated 8 to 10 times. Instruct patients to perform the exercises slowly and increase repetitions as their physical condition improves. Patients need to isometrically exercise muscle groups (quadriceps and gluteal) used for walking 4 times per day until they are ambulatory.

Joint Mobility: The easiest intervention to maintain or improve joint mobility for patients and one that can be coordinated with other activities is the use of ROM exercises (see Chapter 47). In active ROM exercises patients are able to move their joints independently. With passive ROM exercises you move each joint in patients who are unable to perform these exercises themselves. The use of ROM exercises provides data to systematically assess and improve the patient’s joint mobility.

Joints that are not moved periodically are at risk for contractures, a permanent shortening of a muscle followed by the eventual shortening of associated ligaments and tendons. Over time the joint becomes fixed in one position, and the patient loses normal use of it. Passive ROM exercises are the exercises of choice for patients who do not have voluntary motor control.

Older adults experiencing a decline in physical activity and changes in joints often have limited mobility and joint flexibility. Use a variety of recommended approaches to help older adults use proper body mechanics and prevent injury (Box 38-11).

Mechanical devices place specific joints through continuous passive motion (CPM). You will use CPM machines most commonly after joint replacement surgery to place joints through a selective repetitive ROM. You set the machine to certain degrees of joint mobility, with increasing joint mobility or flexion as the goal. Unless contraindicated, the nursing care plan includes exercising each joint through as nearly a full ROM as possible. Initiate passive ROM exercises as soon as the patient loses the ability to move the extremity or joint. Chapter 47 details ROM exercises for each area and illustrates the motion of each joint.

Walking: Walking increases joint mobility. Measure distances walked in feet or yards instead of charting “ambulated to nurses’ station and back.” Illness or trauma usually reduces activity tolerance, resulting in the need for assistance with walking or the use of mechanical devices such as crutches, canes, or walkers.

Helping a Patient to Walk: Helping a patient to walk requires preparation. Assess the patient’s activity tolerance, strength, coordination, baseline vital signs, and balance to determine the type of assistance needed. Also assess the patient’s orientation and determine if there are any signs of distress. Postpone walking if you determine the patient cannot safely walk. Evaluate the environment for safety before ambulation; this includes the removal of obstacles, a clean and dry floor, and the identification of rest points in case the patient’s activity tolerance becomes less than expected or if the patient becomes dizzy. Also have the patient wear supportive, nonskid shoes.

Help the patient to a position of sitting at the side of the bed and dangling the legs over the side of the bed for 1 to 2 minutes before standing. Some patients experience orthostatic hypotension, a drop in blood pressure that occurs when they change from a horizontal to a vertical position (Capan and Lynch, 2007; Monahan et al., 2007). Those at higher risk are patients who are immobilized, patients who are on prolonged bed rest, older adults, and patients with chronic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease (Capan and Lynch, 2007). Signs and symptoms of orthostatic hypotension include dizziness, light-headedness, nausea, tachycardia, pallor, and even fainting. Dangling a patient’s legs before standing is an intermediate step that allows assessment of the patient before changing positions to maintain safety and prevent injury to the patient. In some instances you will need to obtain the patient’s blood pressure while he or she is sitting on the side of the bed.

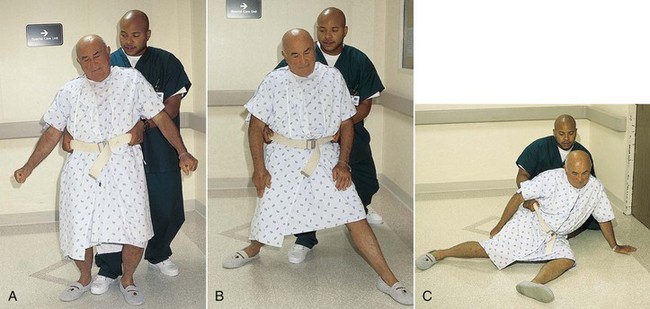

Several methods are used to assist a patient with ambulation. Provide support at the waist so the patient’s center of gravity remains midline. This is achieved with the use of a gait belt. A gait belt encircles the patient’s waist and may have handles attached for the nurse to hold while the patient ambulates.

If the patient has a fainting (syncope) episode or begins to fall, assume a wide base of support with one foot in front of the other, thus supporting the patient’s body weight (Fig. 38-5, A). Extend one leg, let the patient slide against the leg, and gently lower the patient to the floor, protecting the head (Fig. 38-5, B and C). Practice this technique with a friend or classmate before attempting it in a clinical setting. When the patient attempts to ambulate again, proceed more slowly, monitoring for reports of dizziness, and take the patient’s blood pressure before, during, and after ambulation.

Restorative and Continuing Care

Restorative and continuing care involves implementing activity and exercise strategies to assist the patient with ADLs after acute care is no longer needed. Restorative and continuing care also includes activities and exercises that restore and promote optimal functioning in patients with specific chronic illnesses such as coronary heart disease (CHD), hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and diabetes mellitus.

Assistive Devices for Walking

In collaboration with other health care professionals such as physical therapists, promote activity and exercise by teaching the proper use of canes, walkers, or crutches, depending on the assistive device most appropriate for the patient’s condition.

Walkers: Walkers are extremely light, movable devices that are about waist high and made of metal tubing (Fig. 38-6). They have four widely placed, sturdy legs. The patient holds the handgrips on the upper bars, takes a step, moves the walker forward, and takes another step. A walker requires a patient to lift the device up and forward. In the home many patients prefer walkers with wheels or short runners on the legs that allow them to push the walker. Instruct patients on how to use walkers safely and avoid risk of falling.

Canes: Canes are lightweight, easily movable devices made of wood or metal. They provide less support than a walker and are less stable. A person’s cane length is equal to the distance between the greater trochanter and the floor (Pierson and Fairchild, 2008). Two common types of canes are the single straight-legged cane and the quad cane. The single straight-legged cane is more common and is used to support and balance a patient with decreased leg strength. Have the patient keep the cane on the stronger side of the body. For maximum support when walking, the patient places the cane forward 15 to 25 cm (6 to 10 inches), keeping body weight on both legs. The weaker leg is moved forward to the cane so body weight is divided between the cane and the stronger leg. The stronger leg is then advanced past the cane so the weaker leg and the body weight are supported by the cane and weaker leg. During walking the patient continually repeats these three steps. The patient needs to learn that two points of support such as both feet or one foot and the cane are on the floor at all times.

The quad cane provides the most support and is used when there is partial or complete leg paralysis or some hemiplegia (Fig. 38-7). You teach the patient the same three steps that are used with the straight-legged cane.

Crutches: Crutches are often needed to increase mobility. Begin crutch instruction with guidelines for safe use (Box 38-12). The use of crutches is often temporary (e.g., after ligament damage to the knee). However, some patients with paralysis of the lower extremities need them permanently. A crutch is a wooden or metal staff. The two types of crutches are the double adjustable Lofstrand or forearm crutch and the axillary wooden or metal crutch. The forearm crutch has a handgrip and a metal band that fits around the patient’s forearm. The metal band and the handgrip are adjusted to fit the patient’s height. The axillary crutch has a padded curved surface at the top, which fits under the axilla. A handgrip in the form of a crossbar is held at the level of the palms to support the body. It is important to measure crutches for the appropriate length and to teach patients how to use their crutches safely to achieve a stable gait, ascend and descend stairs, and rise from a sitting position.

Measuring for Crutches: The axillary crutch is the more common crutch used. Measurements include the patient’s height, the angle of elbow flexion, and the distance between the crutch pad and the axilla. When crutches are fitted, ensure the length of the crutch is three to four finger widths from the axilla to a point 15 cm (6 inches) lateral to the patient’s heel (Pierson and Fairchild, 2008) (Fig. 38-8).

Position the handgrips so the axillae are not supporting the patient’s body weight. Pressure on the axillae increases risk to underlying nerves, which sometimes results in partial paralysis of the arm. Determine correct position of the handgrips with the patient upright, supporting weight by the handgrips with the elbows slightly flexed at 30 degrees (Pierson and Fairchild, 2008). Elbow flexion may be verified with a goniometer (Fig. 38-9). When you determine the height and placement of the handgrips, verify that the distance between the crutch pad and the patient’s axilla is three to four finger widths (Fig. 38-10).

Crutch Gait: Patients assume a crutch gait by alternately bearing weight on one or both legs and on the crutches. Determine the gait by assessing the patient’s physical and functional abilities and the disease or injury that resulted in the need for crutches. This section summarizes the basic crutch stance and the four standard gaits: four-point alternating gait, three-point alternating gait, two-point gait, and swing-through gait.

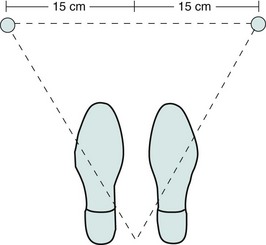

The basic crutch stance is the tripod position, formed when the crutches are placed 15 cm (6 inches) in front of and 15 cm (6 inches) to the side of each foot (Fig. 38-11). This position improves the patient’s balance by providing a wider base of support. The body alignment of the patient in the tripod position includes an erect head and neck, straight vertebrae, and extended hips and knees. The axillae should not bear any weight. The patient assumes the tripod position before crutch walking.

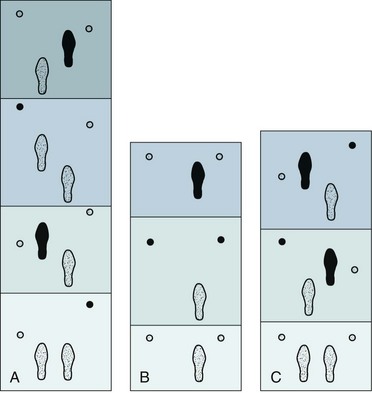

Four-point alternating, or four-point, gait gives stability to the patient but requires weight bearing on both legs. Each leg is moved alternately with each opposing crutch so three points of support are on the floor at all times (Fig. 38-12, A).

FIG. 38-12 A, Four-point alternating gait. Solid feet and crutch tips show the order of foot and crutch tip movement in each of the four phases. (Read from bottom to top.) B, Three-point gait with weight borne on unaffected leg. Solid foot and crutch tips show weight bearing in each phase. (Read from bottom to top.) C, Two-point gait with weight borne partially on each foot and each crutch advancing with opposing leg. Solid areas indicate leg and crutch tips bearing weight. (Read from bottom to top.)

Three-point alternating, or three-point, gait requires the patient to bear all of the weight on one foot. In a three-point gait the patient bears weight on both crutches and then on the uninvolved leg, repeating the sequence (Fig. 38-12, B). The affected leg does not touch the ground during the early phase of the three-point gait. Gradually the patient progresses to touchdown and full weight bearing on the affected leg.

The two-point gait requires at least partial weight bearing on each foot (Fig. 38-12, C). The patient moves a crutch at the same time as the opposing leg so the crutch movements are similar to arm motion during normal walking.

Individuals with paraplegia who wear weight-supporting braces on their legs frequently use the swing-through gait. With weight placed on the supported legs, the patient places the crutches one stride in front and then swings to or through them while they support his or her weight.

Crutch Walking on Stairs: When ascending stairs on crutches, the patient usually uses a modified three-point gait (Fig. 38-13). He or she stands at the bottom of the stairs and transfers body weight to the crutches. The unaffected leg is advanced between the crutches to the stairs. The patient then shifts weight from the crutches to the unaffected leg. Finally he or she aligns both crutches on the stairs. The patient repeats this sequence until he or she reaches the top of the stairs.

FIG. 38-13 Ascending stairs. A, Weight is placed on crutch. B, Weight is transferred from crutches to unaffected leg on stairs. C, Crutches are aligned with unaffected leg on stairs.

A three-phase sequence is also used to descend the stairs (Fig. 38-14). The patient transfers body weight to the unaffected leg. The crutches are placed on the stairs, and the patient begins to transfer body weight to the crutches, moving the affected leg forward. Finally the unaffected leg is moved to the stairs with the crutches. The patient repeats the sequence until reaching the bottom of the stairs.

FIG. 38-14 Descending stairs. A, Body weight is on unaffected leg. B, Body weight is transferred to crutches. C, Unaffected leg is aligned on stairs with crutches.

Because in most cases patients need to use crutches for some time, they need to be taught to use them on stairs before discharge. This instruction applies to all patients who are dependent on crutches, not only those who have stairs in their homes. You will frequently collaborate with physical therapists to provide instruction about crutch walking.

Sitting in a Chair with Crutches: As with crutch walking and crutch walking up and down stairs, the procedure for sitting in a chair involves phases and requires the patient to transfer weight (Fig. 38-15). First the patient positions himself or herself at the center front of the chair with the posterior aspect of the legs touching the chair. Then the patient holds both crutches in the hand opposite the affected leg. If both legs are affected, as with a person with paraplegia who wears weight-supporting braces, the crutches are held in the hand on the patient’s stronger side. With both crutches in one hand, the patient supports body weight on the unaffected leg and the crutches. While still holding the crutches, the patient grasps the arm of the chair with the remaining hand and lowers his or her body into it. To stand the procedure is reversed; and the patient, when fully erect, assumes the tripod position before beginning to walk.

Restoration of Activity and Chronic Illness

Nurses design care plans to increase activity and exercise in patients with specific disease conditions and chronic illnesses such as CHD, hypertension, COPD, and diabetes mellitus.

Coronary Heart Disease: Research shows activity and exercise play a role in secondary prevention or recurrence of CHD. Cardiac rehabilitation is an integral part of comprehensive care of patients diagnosed with CHD. Nurses are involved in many aspects of cardiac rehabilitation and assist patients to develop a program of exercise that fits their needs and level of functioning. Increased physical activity benefits individuals with myocardial infarction (MI), angina pectoris, or heart failure and patients who have had a coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA). Patients with CHD benefit from exercise and activity in terms of reduced mortality and morbidity, improved quality of life, improved left ventricular function, increased functional capacity, decreased blood lipids and apolipoproteins (protein components of lipoprotein complexes), and psychological well-being (Donges et al., 2010; Hamer and Stamatakis, 2009; Mandic et al., 2009).

Hypertension: Exercise reduces systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings. Low- to moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (brisk walking or bicycling) is the most effective in lowering blood pressure, whereas weight training and high-intensity aerobics have minimal benefits (Balady et al., 2010; Ciolac et al., 2009; Edelman and Mandle, 2010).

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Pulmonary rehabilitation helps patients reach an optimal level of functioning. Some patients are fearful of participating in exercise because of the potential of worsening dyspnea (difficulty breathing). This aversion to physical activity sets up a progressive deconditioning in which minimal physical exertion results in dyspnea. Pulmonary rehabilitation provides a safe environment for monitoring patients’ progress. In addition, they receive encouragement and support to increase activity and exercise (Berry et al., 2010; Salhi et al., 2010).

Diabetes Mellitus: Along with diet, glucose monitoring, and medication, exercise is an important component in the care of patients with diabetes mellitus. Individuals with type 1 diabetes need to exercise because it leads to improved glucose control, cardiovascular fitness, and psychological well-being. Exercise lowers blood sugar levels, and the effects of exercise on blood sugar levels often last for at least 24 hours. Instruct the patient with type 1 diabetes about the risks and precautions regarding exercise. Instruction includes the need for a physical examination before beginning an exercise program and precautions to monitor blood glucose level immediately before and after exercise. Also instruct patients to perform low- to moderate-intensity exercises, carry a concentrated form of carbohydrates (sugar packets or hard candy), and wear a medical alert bracelet. The patient with type 2 diabetes who decides to participate in a regular program of exercise needs to include low-intensity warm-up and cool-down exercises, aerobic exercise at 50% to 75% of maximal oxygen uptake, and exercise for 20 to 45 minutes 3 days per week (ADA, 2007; Morrato et al., 2006).

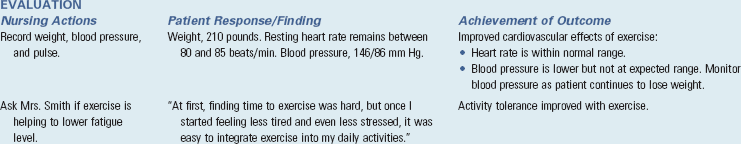

Evaluation

For activity and exercise you measure the effectiveness of nursing interventions by the success of meeting the patient’s expected outcomes and goals of care. The patient is the only one who knows the effectiveness and benefits of activity and exercise (Fig. 38-16). Continuous evaluation helps to determine whether new or revised therapies are needed and if new nursing diagnoses have developed.

Patient Outcomes

To evaluate the effectiveness of nursing interventions to enhance activity and exercise, make comparisons with baseline measures that include pulse, blood pressure, strength, endurance, and psychological well-being. Compare actual outcomes with expected outcomes to determine the patient’s health status and progression. The following is an example of questions you ask when your patients do not meet their expected outcomes:

• The last time we met, you planned to walk outside for 20 minutes three days a week. However, you report that you are only able to walk twice a week right now. What do you think is preventing you from meeting your goal?

• Your weight is the same this month as it was last month. We were hoping that increasing your activity would lead to a decrease in your weight. Help me understand the factors you believe are preventing you from losing weight right now.

• You state that you experience leg pain after walking short distances. Describe your pain. What pain-relieving measures have you tried?

Key Points

• Exercise is physical activity for the purpose of conditioning the body, improving health, and maintaining fitness; it also is a therapeutic measure.

• Activity tolerance is the kind and amount of exercise or work that a person is able to perform. Physiological, emotional, and developmental factors influence the patient’s activity tolerance.

• The best program of physical activity includes a combination of exercises that produces different physiological and psychological benefits.

• Body mechanics are the coordinated efforts of the musculoskeletal and nervous systems as the person moves, lifts, bends, stands, sits, lies down, and completes daily activities.

• Coordinated body movement requires integrated functioning of the skeletal system, skeletal muscles, and nervous system.

• Muscles primarily associated with movement are located near the skeletal region, where movement results from leverage, which is characteristic of movements of the upper extremities.

• Coordination and regulation of muscle groups depend on muscle tone and activity of antagonistic, synergistic, and antigravity muscles.

• The nervous system controls balance through the functions of the cerebellum and inner ear.

• You achieve body balance when there is a wide base of support, the center of gravity falls within the base of support, and a vertical line falls from the center of gravity through the base of support.

• Developmental changes, behavioral aspects, environmental issues, cultural and ethnic origin, and family and social support influence the patient’s perception and motivation to engage in physical activity and exercise.

• Ability to engage in normal physical activity and exercise depends on intact and functioning nervous and musculoskeletal systems.

• Use the nursing process to provide care for patients who are experiencing or are at risk for activity intolerance and impaired physical mobility.

• After identifying nursing diagnoses, plan and implement interventions to increase activity and exercise in collaboration with the patient when possible.

• Range-of-motion exercises incorporated into daily activities include one or all of the body joints.

• Mechanical devices to promote walking include canes, walkers, and crutches.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

Mrs. Smith has experienced some success in initiating an exercise program. However, maintaining her exercise plan is becoming challenging, and she is not seeing the improvements that she expects. She states, “I feel like I’m doing everything right, but I’m getting few results for my efforts.”

1. Mrs. Smith states, “I don’t want to leave the house anymore.” She also expresses feelings of overwhelming stress and excessive demands on her time. What interventions do you suggest to Mrs. Smith to help overcome this barrier to exercise?

2. Mrs. Smith has several challenges to initiating and maintaining an exercise program. Develop a stepwise approach for Mrs. Smith that helps her initiate and maintain an exercise program, keeping in mind the challenges that she faces.

3. Develop an educational component to Mrs. Smith’s care plan, emphasizing the benefits of exercise.

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. A patient on bed rest for several days attempts to walk with assistance. He becomes dizzy and nauseated. His pulse rate jumps from 85 to 110 beats/min. These are most likely symptoms of which of the following?

2. Which action(s) are appropriate for the nurse to implement when a patient experiences orthostatic hypotension? (Select all that apply.)

3. Take patient’s blood pressure and pulse.

4. Continue to ambulate patient to build endurance.

5. If patient begins to faint, allow him to slide against the nurse’s leg to the floor.

3. Which of the following best motivates a patient to participate in an exercise program?

1. Giving a patient information on exercise

2. Providing information to the patient when the patient is ready to change behavior

3. Explaining the importance of exercise when a patient is diagnosed with a chronic disease such as diabetes

4. Following up with instructions after the health care provider tells a patient to begin an exercise program

4. Which of the following is a principle of proper body mechanics when lifting or carrying objects?

1. Keep the knees in a locked position.

2. Bend at the waist to maintain a center of gravity.

5. Which group of patients is at most risk for severe injuries related to falls?

6. A nurse plans to provide education to the parents of school-aged children and includes which of the following result of children being less physically active outside of school?

7. A nursing assistive personnel asks for help to transfer a patient who is 125 pounds (56.8 kg) from the bed to a wheelchair. The patient is unable to assist. What is the nurse’s best response?

1. “As long as we use proper body mechanics, no one will get hurt.”

2. “The patient only weighs 125 lb. You don’t need my assistance.”

8. You are transferring a patient who weighs 320 lb (145.5 kg) from his bed to a chair. The patient has an order for partial weight bearing as a result of bilateral reconstructive knee surgery. Which of the following is the best technique for transfer?

9. Which is the correct gait when a patient is ascending stairs on crutches?

1. A modified two-point gait. The affected leg is advanced between the crutches to the stairs.

2. A modified three-point gait. The unaffected leg is advanced between the crutches to the stairs.

4. A modified four-point gait. Both legs advance between the crutches to the stairs.

10. A patient recovering from bilateral knee replacements is prescribed bilateral partial weight bearing. You reinforce crutch walking knowing that which of the following crutch gaits is most appropriate for this patient?

11. A patient with a right knee replacement is prescribed no weight bearing on the right leg. You reinforce crutch walking knowing that which of the following crutch gaits is most appropriate for this patient?

12. A patient on week-long bed rest is now performing isometric exercises. Which nursing diagnosis best addresses the safety of this patient?

13. Which of the following activities does the nurse delegate to nursing assistive personnel in regard to crutch walking? (Select all that apply.)

1. Notify nurse if patient reports pain before, during, or after exercise.

2. Notify nurse of patient complaints of increased fatigue, dizziness, light-headedness when obtaining vital signs before and/or after exercise.

3. Notify nurse of vital sign values.

4. Evaluate the patient’s ability to use crutches properly.

5. Prepare the patient for exercise by assisting in dressing and putting on shoes.

14. Select statements that apply to the proper use of a cane. (Select all that apply.)

1. For maximum support when walking, the patient places the cane forward 15 to 25 cm (6 to 10 inches), keeping body weight on both legs. The weaker leg is moved forward to the cane so body weight is divided between the cane and the stronger leg.

2. A person’s cane length is equal to the distance between the elbow and the floor.

3. Canes provide less support than a walker and are less stable.

4. The patient needs to learn that two points of support such as both feet or one foot and the cane need to be present at all times.

15. A patient is discharged after an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). She states, “I’m afraid to go to pulmonary rehabilitation.” What is your best response?

1. Pulmonary rehabilitation provides a safe environment for monitoring your progress.

2. You have to participate or you will be back in the hospital.

3. Tell me more about your concerns with going to pulmonary rehabilitation.

4. The staff at our pulmonary rehabilitation facility are professionals and will not cause you any harm.

Answers: 1. 2; 2. 1, 2, 3, 5; 3. 2; 4. 3; 5. 2; 6. 1; 7. 3; 8. 4; 9. 2; 10. 1; 11. 2; 12. 4; 13. 1, 2, 3, 5; 14. 1, 3, 4; 15. 1.

References

Ackley, BJ, Ladwig, GB. Nursing diagnosis handbook: an evidence-based guide to planning care, ed 8. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). Position stand on fitness: the recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness and flexibility in healthy adults. http://www.50plus.org/Libraryitems/1_5positionstandonfitness.htm, 2007. [accessed August 2010.].

American Diabetes Association (ADA). Diabetes and exercise: position statement. Diabetes Care. 2007:S58.

American Nurses Association (ANA). Position statement on elimination of manual patient handling to prevent work-related musculoskeletal disorders. http://www.nursingworld.org/readroom/postion/workplace/pathand.htm, 2008. [accessed August 2010.].

Balady, GJ, et al. Clinician’s guide to cardiopulmonary exercise testing in adults: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122(2):191.

Chodzko-Zajko, WJ, et al. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exercise. 2009;41(7):1510.