Older Adults

• Identify common myths and stereotypes about older adults.

• Identify selected biological and psychosocial theories of aging.

• Discuss common developmental tasks of older adults.

• Describe common physiological changes of aging.

• Differentiate among delirium, dementia, and depression.

• Discuss issues related to psychosocial changes of aging.

• Describe selected health concerns of older adults.

• Identify nursing interventions related to the physiological, cognitive, and psychosocial changes of aging.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Age 65 is considered to be the lower boundary for “old age” in demographics and social policy within the United States. However many older adults consider themselves to be “middle-age” well into their seventh decade. Chronological age often has little relation to the reality of aging for an older adult. Each person ages in his or her own way. Every older adult is unique, and as a nurse you need to approach each one as an individual, even though this chapter makes generalizations about the aging process and its effect on individuals.

The number of older adults in the United States is growing, both absolutely and as a proportion of the total population. In 2009 there were 39.6 million adults over age 65 in the United States, representing 12.9% of the population or one in eight Americans (Administration on Aging [AOA], 2010). This represents an increase of 4.8 million since 1998. Part of that increase is the result of extension of the average life span. Women who were age 65 in 2007 could expect to live another 19.8 years, and men another 17.1 years. According to estimates, the number of older adults will increase to 72.1 million by 2030. Factors that contribute to the projected increase in the number of older adults are the aging of the baby-boom generation and the growth of the population segment over age 85. The baby boomers are the large group of adults born between 1946 and 1964. The first baby boomers reached age 65 in 2011. As the large number of baby boomers age, the social and health care programs necessary to meet their needs must dramatically reform their services. The diversity of the population over age 65 is also increasing. In 2008 minorities (African Americans, Hispanics, Asians, American Indians/Eskimos/Aleuts, and other Pacific Islanders) made up 19.6% of the population over age 65 (AOA, 2010). Nurses need to take the cultural, ethnic, and racial diversity represented by these numbers into account as they care for older adults from these groups. The challenge is to gain new knowledge and skills to provide culturally sensitive and linguistically appropriate care. Chapter 9 provides further information on culturally competent care.

Variability Among Older Adults

The nursing care of older adults poses special challenges because of great variation in their physiological, cognitive, and psychosocial health. Older adults also vary widely in their levels of functional ability. Most older adults are active and involved members of their communities. A smaller number have lost the ability to care for themselves, are confused or withdrawn, and/or are unable to make decisions concerning their needs. Most older adults live in noninstitutional settings. In 2008 54.6% of older adults in noninstitutional settings lived with a spouse (41.7% of older women, 72% of older men) (AOA, 2009); 30.5% lived alone (39.5% of older women, 18.5% of older men); and only 4.1% of all older adults resided in institutions such as nursing homes or centers.

Aging does not inevitably lead to disability and dependence. Most older people remain functionally independent despite the increasing prevalence of chronic disease. Nursing assessment provides valuable clues to the effects of a disease or illness on a patient’s functional status. Chronic conditions add to the complexity of assessment and care of the older adult. Most older persons have at least one chronic condition, and many have multiple conditions. The most frequently diagnosed chronic conditions occurring in 2005 to 2007 were arthritis (49%), hypertension (41%), all types of heart disease (31%), any cancer (22%), and diabetes (18%) (AOA, 2009). The physical and psychosocial aspects of aging are closely related. A reduced ability to respond to stress, the experience of multiple losses, and the physical changes associated with normal aging combine to place people at high risk for illness and functional deterioration. Although the interaction of these physical and psychosocial factors is often serious, do not assume that all older adults have signs, symptoms, or behaviors representing disease and decline or that these are the only factors you need to assess. You also need to identify the older adult’s strengths and abilities during the assessment and encourage independence as an integral part of your plan of care (Kresevic, 2008).

Myths and Stereotypes

Despite ongoing research in the field of gerontology, myths and stereotypes about older adults persist. These include false ideas about their physical and psychosocial characteristics and lifestyles. When health care providers hold negative stereotypes about aging, they can negatively affect the quality of patient care. Although nurses are susceptible to these myths and stereotypes, they have the responsibility to replace them with accurate information.

Some people stereotype older adults as ill, disabled, and physically unattractive. Although many older adults have chronic conditions or have at least one disability that limits their performance of activities of daily living (ADLs), most noninstitutionalized older adults (39.1%) assess their health as excellent or very good (AOA, 2009). Some people believe that older adults are forgetful, confused, rigid, bored, and unfriendly and that they are unable to understand and learn new information. Yet specialists in the field of gerontology view centenarians, the oldest of the old, as having an optimistic outlook on life, good memories, broad social contacts and interests, and tolerance for others. Although changes in vision or hearing and reduced energy and endurance sometimes affect the process of learning, older adults are lifelong learners. Use teaching techniques to compensate for sensory changes, provide additional time for remembering and responding, and present concrete rather than abstract material to facilitate learning by older adults. Other effective teaching techniques draw on the older adult’s past experiences and correspond to his or her identified interests rather than to the content areas that the health care professional believes are important. Box 14-1 presents additional teaching strategies to address the special learning needs of older adults.

Stereotypes about lifestyles include mistaken ideas about living arrangements and finances. Misconceptions about their financial status range from beliefs that many are affluent to beliefs that many are poor. According to the AOA (2009), 9.7% of persons over age 65 had incomes below the poverty level, with another 6.3% classified as near poor. The median income reported was $18,337, with 87% coming from Social Security.

In a society that values attractiveness, energy, and youth, these myths and stereotypes lead to the undervaluing of older adults. Some people equate worth with productivity; therefore they think that older adults become worthless after they leave the workforce. Others consider their knowledge and experience too outdated to have any current value. These ideas demonstrate ageism, which is discrimination against people because of increasing age, just as people who are racists and sexists discriminate because of skin color and gender. According to experts in the field of gerontology, unopposed ageism has the potential to undermine the self-confidence of older adults, limit their access to care, and distort caregivers’ understanding of the uniqueness of each older adult. Older adults who have a positive image about aging actually live 7.5 years longer than those with a negative image (Levy et al., 2002). Nursing can help promote a positive perception regarding the aging process when working with these patients.

Today laws exist that ban discrimination on the basis of age. The economic and political power of older adults challenges ageist views. Older adults are a significant proportion of the consumer economy. As voters and activists in various issues, they have major influence in the formation of public policy. Their participation adds a unique perspective on social, economic, and technological issues because they have experienced almost a century of developments. In the past 100 years our nation has progressed from riding in horse-drawn carriages to tracking the adventures of the international space station. Gaslights and steam power have been replaced by electricity and nuclear power. Computers and copier machines replace typewriters and carbon paper. Many older adults lived through or were born during the Great Depression of 1929. They also experienced two world wars and wars in Korea, Vietnam, and the Persian Gulf and are now experiencing the war on terrorism. Older adults have seen changes in health care as the era of the family physician gave way to the age of specialization. After witnessing the government initiatives establishing the Social Security system, Medicare, and Medicaid, older adults are currently living with the changes imposed by health care reform and the uncertainty of the future of Social Security and Medicare. Living through all of these events and changes, they have stories and examples of coping with change to share.

Nurses’ Attitudes Toward Older Adults

It is important for you to assess your own attitudes toward older adults; your own aging; and the aging of your family, friends, and patients. Nurses’ attitudes come from personal experiences with older adults, education, employment experiences, and attitudes of co-workers and employing institutions. Given the increasing number of older adults in health care settings, forming positive attitudes toward them and gaining specialized knowledge about aging and their health care needs are priorities for all nurses. Positive attitudes are based in part on a realistic portrayal of the characteristics and health care needs of older adults. It is critical for you to learn to respect older adults and actively involve them in care decisions and activities. In the past institutional settings such as hospitals and nursing centers often treated older adults as objects rather than independent, dignified people. The time has come for nurses to recognize and address ageism by questioning prevailing negative attitudes and stereotypes and reinforcing the realities of aging as they care for older adults in all care settings.

Theories of Aging

Various theories exist that describe the complex biopsychosocial processes of aging. However, there is no single, universally accepted theory that predicts and explains the complexities of the aging process. You need to be aware of the scientific attempts to explain the aging process and the concepts included in the theories. Although the theories are in various stages of development and have limitations, use them to increase your understanding of the phenomena affecting the health and well-being of older adults and to guide nursing care.

The biological theories of aging are either stochastic or nonstochastic. Stochastic theories view aging as the result of random cellular damage that occurs over time. The accumulated damage leads to the physical changes that are recognized as characteristic of the aging process. Nonstochastic theories view aging as the result of genetically programmed physiological mechanisms within the body that control the process of aging.

The psychosocial theories of aging, developed during the 1960s, explain changes in behavior, roles, and relationships that come with aging. These theories reflect the values that the theorist and society held at the time the theory was developed. A sample of theories follows. Disengagement theory, the oldest psychosocial theory, states that aging individuals withdraw from customary roles and engage in more introspective, self-focused activities (Cummings and Henry, 1961). The activity theory, unlike the disengagement theory, considers the continuation of activities performed during middle age as necessary for successful aging (Havighurst et al., 1963). Continuity theory, or developmental theories, suggests that personality remains stable and behavior becomes more predictable as people age (Neugarten, 1964). The personality and behavior patterns developed during a lifetime determine the degree of engagement and activity in older adulthood. The more recent theory of gerotranscendence proposes that the older adult experiences a shift in perspective with age (Wadensten, 2007). The person moves from a materialistic and national view of the world to a more cosmic and transcendent one, causing an increase in overall life satisfaction (Jett, 2008). Critics suggest that theories either fail in some measure to consider the many factors that affect an individual’s response to aging or address those factors in a too-simplistic fashion. Rather, each individual ages uniquely.

Developmental Tasks for Older Adults

Theories of aging are closely linked to the concept of developmental tasks appropriate for distinct stages of life. Although no two individuals age in the same way, either biologically or psychosocially, researchers have developed frameworks outlining developmental tasks for older adults (Box 14-2). These developmental tasks are common to many older adults and are associated with varying degrees of change and loss. The more common losses are of health, significant others, a sense of being useful, socialization, income, and independent living. How older adults adjust to the changes of aging is highly individualized. For some adaptation and adjustment are relatively easy. For others coping with aging changes requires the assistance of family, friends, and health care professionals. Be sensitive to the effect of losses on older adults and their families and be prepared to offer support.

Older adults must adjust to the physical changes that accompany aging. The extent and timing of these changes vary from individual to individual; but, as body systems age, changes in appearance and functioning occur. These changes are not associated with a disease; they’re normal. The presence of disease sometimes alters the timing of the changes or their impact on daily life. The section on physiological changes describes structural and functional changes of aging.

Some older adults, both men and women, find it difficult to accept aging. This is apparent when they understate their ages when asked, adopt younger styles of clothing, or attempt to hide physical evidence of aging with cosmetics. Others deny their aging in ways that are potentially problematic. For example, some older adults deny functional declines and refuse to ask for help with tasks that place their safety at great risk. Others avoid activities designed for their benefit such as senior citizens’ centers and senior health promotion activities and thus do not receive the benefits these programs offer. Acceptance of personal aging does not mean retreat into inactivity, but it does require a realistic review of strengths and limitations.

Older adults retired from employment outside the home have to cope with the loss of a work role. Older adults who worked at home and the spouses of those who worked outside the home also face role changes. Some may welcome retirement as a time to pursue new interests and hobbies, volunteer in their community, continue their education, or start a new career. Retirement plans for others may include changing residence by moving to a different city or state or to a different type of housing within the same area. Reasons other than retirement also lead to changes of residence. For example, physical impairments may require relocation to a smaller, single-level home or nursing center. A change in living arrangements for the older adult usually requires an extended period of adjustment, during which assistance and support from health care professionals, friends, and family members are necessary.

The majority of older adults cope with the death of a spouse. In 2008 almost half (42%) of all older women were widows, and 14% of older men were widowers (AOA, 2010). Some older adults must cope with the death of adult children and grandchildren. All experience the deaths of friends. These deaths represent both losses and reminders of personal mortality. Coming to terms with them is often difficult. By assisting older adults through the grieving process, you help them resolve the issues posed by these deaths.

The redefining of relationships with children that occurred as the children grew up and left home continues as older adults experience the challenges of aging. A variety of issues sometimes occur, including but not limited to control of decision making, dependence, conflict, guilt, and loss. How these issues surface in situations and how they are resolved depend in part on the past relationship between the older adult and their adult children. All the involved parties have past experiences and powerful emotions. When adult children become their parents’ caregivers, they have to find ways to balance the demands of their own children and careers with the many challenges of family caregiving. As adult children and aging parents negotiate the aspects of changing roles, nurses are in the position to act as counselors to both the parents and the children. An aim is to help older adults find ways to maintain their quality of life. What defines quality of life is unique for each person.

Community-Based and Institutional Health Care Services

Nurses encounter older-adult patients in a wide variety of community and institutional health care settings. Outside of an acute care hospital, nurses care for older adults in private homes and apartments, retirement communities, adult day care centers, assisted-living facilities, and nursing centers (extended care, intermediate care, and skilled nursing facilities). Chapter 2 describes these settings and the services provided in detail.

Nurses help older adults and their families by providing information and answering questions as they make choices among care options. The assistance of the nurse is especially valuable when decisions about moving to a nursing center must be made. Some family caregivers consider nursing center placement when in-home care becomes increasingly difficult or when convalescence (recovery) from hospitalization requires more assistance than the family is able to provide. Although the decision to enter a nursing center is never final and a nursing center resident is sometimes discharged to home or another less-acute facility, many older adults may view the nursing center as their final residence. Results of state and federal inspections of nursing centers are available to the public at the nursing center, on-line, and at the inspectors’ offices. The best way to evaluate the quality of a nursing center in a community is for the patient and family to visit that facility and inspect it personally. The Medicare website (http://www.Medicare.gov/NHcompare) is an excellent resource for you to learn about the quality rating of a nursing center based on the health inspections, staffing, and quality measures of the facility. It also offers a nursing center checklist. Box 14-3 summarizes some features to look for in a nursing center.

Assessing the Needs of Older Adults

Gerontological nursing requires creative approaches for maximizing the potential of older adults. With comprehensive assessment information regarding strengths, limitations, and resources, the nurse and the older adult identify needs and problems. Together they select interventions to maintain the older adult’s physical abilities and create an environment for psychosocial and spiritual well-being. A thorough assessment requires the nurse to actively engage older adults and provide them enough time to share important information about their health.

Nursing assessment takes into account five key points to ensure an age-specific approach: (1) the interrelation between physical and psychosocial aspects of aging, (2) the effects of disease and disability on functional status, (3) the decreased efficiency of homeostatic mechanisms, (4) the lack of standards for health and illness norms, and (5) altered presentation and response to a specific disease (Meiner, 2011). A comprehensive assessment of an older adult takes more time than the assessment of a younger adult because of the longer life and medical history and the potential complexity of the history. During the physical examination allow rest periods as needed or conduct the assessment in several sessions because of the reduced energy and limited endurance of some frail older adults. Remember to review both prescribed and over-the-counter medications carefully with the patient.

Sensory changes also affect data gathering. Your choice of communication techniques depends on visual or hearing impairments of the older adult. If older adults are unable to understand your visual or auditory cues, assessment data may be inaccurate or misleading. For example, if an older adult has difficulty hearing a nurse’s questions, inappropriate responses might lead the nurse to believe that the person is confused. Chapter 49 explains in detail techniques to use when communicating with older adults who have a hearing impairment. When a person has a visual impairment, use these communication techniques:

• Sit or stand at eye level, in front of the patient in full view.

• Face the older adult while speaking; do not cover your mouth.

• Provide diffuse, bright, nonglare lighting.

• Encourage the older adult to use his or her familiar assistive devices such as glasses or magnifiers.

Memory deficits, if present, affect the accuracy and completeness of an assessment. Information contributed by a family member or other caregiver is sometimes necessary to supplement the older adult’s recollection of past medical events and information such as allergies and immunizations. Use tact when involving another person in the assessment interview. The additional person supplements the answers of the older adult with the consent of the older adult, but the older adult remains the focus of the interview.

During all aspects of the assessment you are responsible for providing culturally competent care. See Chapter 9 for a detailed description of the components of a cultural assessment. There are ways to provide culturally competent care while communicating with older adults during the assessment process (Box 14-4).

During assessment use caution when interpreting the signs and symptoms of diseases and laboratory values. Historically researchers have used younger populations to establish these signs and norms. However, the classic signs and symptoms of diseases are sometimes absent, blunted, or atypical in older adults (Gray-Miceli et al., 2010). This is especially true in the case of bacterial infection, pain, acute myocardial infarction, and heart failure. The masquerading of disease is possibly caused by age-related changes in organ systems and homeostatic mechanisms, progressive loss of physiological and functional reserves, or coexisting acute or chronic conditions. As a result the older adult with a urinary tract infection may present with confusion, incontinence, and an elevation of body temperature (within normal limits) instead of having fever, dysuria, frequency, or urgency. Some older adults with pneumonia have tachycardia, tachypnea, and confusion with decreased appetite and functioning, without the more common symptoms of fever and productive cough. Instead of crushing, substernal chest pain and diaphoresis, the older adult with a myocardial infarction experiences a sudden onset of dyspnea often accompanied by anxiety and confusion. Variations from the usual norms for laboratory values are sometimes caused by age-related changes in cardiac, pulmonary, renal, and metabolic function (Amella, 2006).

It is important to recognize early indicators of an acute illness in older adults. Note changes in mental status, occurrence and reason for falls, dehydration, decrease in appetite, loss of function, dizziness, and incontinence because these may be indicators not presented in younger adults. A key principle of providing age-appropriate nursing care is timely detection of these cardinal signs of illness so early treatment can begin (Box 14-5). Mental status changes commonly occur as a result of disease and psychological issues. Some mental changes are often drug related, caused by drug toxicity or adverse drug events. A fall can be a common event for an older adult and can be injury producing and costly (Ferrari et al., 2010). A fall is a complex event that needs careful investigation to find out if it was the result of environmental causes or the symptom of a new-onset illness. Problems with the cardiac, respiratory, musculoskeletal, neurological, urological, and sensory body systems can present with a fall as a chief symptom of a new-onset condition. Dehydration is common in older adults because of decreased oral intake related to a reduced thirst response and less free water as a consequence of a decrease in muscle mass. When vomiting and diarrhea accompany the onset of an acute illness, the older adult is at risk for further dehydration. Decrease in appetite is a common symptom with the onset of pneumonia, heart failure, and urinary tract infection. Loss of functional ability occurs in a subtle fashion over a period of time; or it occurs suddenly, depending on the underlying cause. Thyroid disease, infection, cardiac or pulmonary conditions, metabolic disturbances, and anemia are common causes of functional decline; thus nurses play an essential role in early identification, referral, and treatment of health problems.

Physiological Changes

Perception of well-being defines quality of life. Understanding the older adult’s perceptions about health status is essential for accurate assessment and development of clinically relevant interventions. Their concepts of health generally depend on personal perceptions of functional ability. Therefore older adults engaged in ADLs usually consider themselves healthy; whereas those who have physical, emotional, or social impairments that limit their activities perceive themselves as ill.

Some frequently observed physiological changes in older adults are normal (Table 14-1). The changes are not always pathological processes in themselves, but they make older adults more vulnerable to some common clinical conditions and diseases. Some older adults experience all of these changes, and others experience only a few. The body changes continuously with age; and specific effects on particular older adults depend on health, lifestyle, stressors, and environmental conditions. The nurse needs to know about these normal, more common changes to provide appropriate care for older adults and assist with adaptation to the changes.

TABLE 14-1

Common Physiological Changes with Aging at a Glance

| SYSTEM | COMMON CHANGES |

| Integumentary | Loss of skin elasticity with fat loss in extremities, pigmentation changes, glandular atrophy (oil, moisture, sweat glands), thinning hair, with hair turning gray-white (facial hair: decreased in men, increased in women), slower nail growth, atrophy of epidermal arterioles |

| Respiratory | Decreased cough reflex; decreased cilia; increased anterior-posterior chest diameter; increased chest wall rigidity; fewer alveoli, increased airway resistance; increased risk of respiratory infections |

| Cardiovascular | Thickening of blood vessel walls; narrowing of vessel lumen; loss of vessel elasticity; lower cardiac output; decreased number of heart muscle fibers; decreased elasticity and calcification of heart valves; decreased baroreceptor sensitivity; decreased efficiency of venous valves; increased pulmonary vascular tension; increased systolic blood pressure; decreased peripheral circulation |

| Gastrointestinal | Periodontal disease; decrease in saliva, gastric secretions, and pancreatic enzymes; smooth muscle changes with decreased esophageal peristalsis and small intestinal motility; gastric atrophy, decreased production of intrinsic factor, increased stomach pH, loss of smooth muscle in the stomach, hemorrhoids, anal fissures; rectal prolapse and impaired rectal sensation. |

| Musculoskeletal | Decreased muscle mass and strength, decalcification of bones, degenerative joint changes, dehydration of intervertebral disks |

| Neurological | Degeneration of nerve cells, decrease in neurotransmitters, decrease in rate of conduction of impulses |

| Sensory | |

| Eyes | Decreased accommodation to near/far vision (presbyopia), difficulty adjusting to changes from light to dark, yellowing of the lens, altered color perception, increased sensitivity to glare, smaller pupils |

| Ears | Loss of acuity for high-frequency tones (presbycusis), thickening of tympanic membrane, sclerosis of inner ear, buildup of earwax (cerumen) |

| Taste | Often diminished; often fewer taste buds |

| Smell | Often diminished |

| Touch | Decreased skin receptors |

| Proprioception | Decreased awareness of body positioning in space |

| Genitourinary | Fewer nephrons, 50% decrease in renal blood flow by age 80, decreased bladder capacity Male—enlargement of prostate Female—reduced sphincter tone |

| Reproductive | Male—sperm count diminishes, smaller testes, erections less firm and slow to develop Female—decreased estrogen production, degeneration of ovaries, atrophy of vagina, uterus, breasts |

| Endocrine | General—alterations in hormone production with decreased ability to respond to stress Thyroid—decreased secretions Cortisol, glucocorticoids—increased antiinflammatory hormone Pancreas—increased fibrosis, decreased secretion of enzymes and hormones |

| Immune System | Thymus involution T-cell function decreases |

Modified from Touhy T, Jett K: Ebersole and Hess’ gerontological nursing and healthy aging, ed 3, St Louis, 2010, Mosby.

General Survey

The general survey begins during the initial nurse-patient encounter and includes a quick but careful head-to-toe scan of the older adult that the nurse writes in a brief description (see Chapter 30). An initial inspection reveals if eye contact and facial expression are appropriate to the situation and universal aging changes such as facial wrinkles, gray hair, loss of body mass in the extremities, and an increase of body mass in the trunk.

Integumentary System

With aging the skin loses resilience and moisture. The epithelial layer thins, and elastic collagen fibers shrink and become rigid. Wrinkles of the face and neck reflect lifelong patterns of muscle activity and facial expressions, the pull of gravity on tissue, and diminished elasticity. Spots and lesions are often present on the skin. Smooth, brown, irregularly shaped spots (age spots or senile lentigo) initially appear on the backs of the hands and on forearms. Small, round, red or brown cherry angiomas occur on the trunk. Seborrheic lesions or keratoses appear as irregular, round or oval, brown, watery lesions. Years of sun exposure contribute to the aging of the skin and lead to premalignant and malignant lesions. You need to rule out these three malignancies related to sun exposure when examining skin lesions: melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma (see Chapter 30).

Head and Neck

The facial features of the older adult may become more pronounced from loss of subcutaneous fat and skin elasticity. Facial features appear asymmetrical because of missing teeth or improperly fitting dentures. In addition, common vocal changes include a rise in pitch and a loss of power and range.

Visual acuity declines with age. This is often the result of retinal damage, reduced pupil size, development of opacities in the lens, or loss of lens elasticity. Presbyopia, a progressive decline in the ability of the eyes to accommodate from near to far vision, is common. Ability to see in darkness and adapt to abrupt changes from dark to light areas (and the reverse) is reduced. More ambient light is necessary for tasks such as reading and other ADLs. Older adults have increased sensitivity to the effects of glare. Pupils are smaller and react slower. Objects do not appear bright, but the older adult has difficulty when coming from bright to dark environments. Changes in color vision and discoloration of the lens make it difficult to distinguish between blues and greens and among pastel shades. Dark colors such as blue and black appear the same. Diseases of the older eye include cataract, macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and retinal detachment. Cataracts, a loss of the transparency of the lens, are a prevalent disorder among older adults. They normally result in blurred vision, sensitivity to glare, and gradual loss of vision. Chapter 49 outlines nursing interventions for adapting to a patient’s visual changes.

Noise is the most prevalent risk factor for impaired hearing. Exposure earlier in life exacerbates hearing loss in old age. However, auditory changes are often subtle. Most of the time older adults ignore the early signs of hearing loss until friends and family members comment on compensatory attempts such as turning up the volume on televisions or avoiding social conversations. A common age-related change in auditory acuity is presbycusis. Presbycusis affects the ability to hear high-pitched sounds and sibilant consonants such as s, sh, and ch. Before the nurse assumes presbycusis, it is necessary to inspect the external auditory canal for the presence of cerumen. Impacted cerumen, a common cause of diminished hearing acuity, is easy to treat.

Salivary secretion is reduced, and taste buds atrophy and lose sensitivity. The older adult is less able to differentiate among salty, sweet, sour, and bitter tastes. The sense of smell also decreases, further reducing taste. Health conditions, treatments, and/or medications can alter taste. It is often a challenge to promote optimal nutrition in an older patient because of the loss of smell and changes in taste.

Thorax and Lungs

Because of changes in the musculoskeletal system, the configuration of the thorax sometimes changes. Respiratory muscle strength begins to decrease, and the anteroposterior diameter of the thorax increases. Vertebral changes caused by osteoporosis lead to dorsal kyphosis, the curvature of the thoracic spine. Calcification of the costal cartilage causes decreased mobility of the ribs. The chest wall gradually becomes stiffer. Lung expansion decreases, and the person is less able to cough deeply. If kyphosis or chronic obstructive lung disease is present, breath sounds become distant. With these changes the older adult is more susceptible to pneumonia and other bacterial or viral infections.

Heart and Vascular System

Decreased contractile strength of the myocardium results in decreased cardiac output. The decrease is significant when the older adult experiences anxiety, excitement, illness, or strenuous activity. The body tries to compensate for decreased cardiac output by increasing the heart rate during exercise. However, after exercise it takes longer for the older adult’s rate to return to baseline. Systolic and/or diastolic blood pressures are sometimes abnormally high. Although a common chronic condition, hypertension is not a normal aging change and predisposes older adults to heart failure, stroke, renal failure, coronary heart disease, and peripheral vascular disease.

Peripheral pulses frequently are weaker, although still palpable, in the lower extremities. Older adults sometimes complain that their lower extremities are cold, particularly at night. Changes in the peripheral pulses in the upper extremities are less common.

Breasts

As estrogen production diminishes, the milk ducts of the breasts are replaced by fat, making breast tissue less firm. Decreased muscle mass, tone, and elasticity result in smaller breasts in older women. In addition, the breasts sag. Atrophy of glandular tissue, coupled with more fat deposits, results in a slightly smaller, less dense, and less nodular breast. Gynecomastia, enlarged breasts in men, is often the result of medication side effects, hormonal changes, or obesity. Both older men and women are at risk of breast cancer.

Gastrointestinal System and Abdomen

Aging leads to an increase in the amount of fatty tissue in the trunk. As a result, the abdomen increases in size. Because muscle tone and elasticity decrease, it also becomes more protuberant. Gastrointestinal function changes include a slowing of peristalsis and alterations in secretions. The older adult experiences these changes by becoming less tolerant of certain foods and having discomfort from delayed gastric emptying. Alterations in the lower gastrointestinal tract lead to constipation, flatulence, or diarrhea.

Reproductive System

Changes in the structure and function of the reproductive system occur in both sexes as the result of hormonal alterations. Female menopause is related to a reduced responsiveness of the ovaries to pituitary hormones and a resultant decrease in estrogen and progesterone levels. In men there is no definite cessation of fertility associated with aging. Spermatogenesis begins to decline during the fourth decade and continues into the ninth. However, the changes in reproductive structure and function do not affect libido; sexual desires, thoughts, and actions continue throughout all decades of life (Wallace, 2008). Less frequent sexual activity often results from illness, death of a sexual partner, or decreased socialization.

Urinary System

Hypertrophy of the prostate gland is frequently seen in older men. This hypertrophy enlarges the gland and places pressure on the neck of the bladder. As a result, urinary retention, frequency, incontinence, and urinary tract infections occur. In addition, prostatic hypertrophy results in difficulty initiating voiding and maintaining a urinary stream. Benign prostatic hypertrophy is different from cancer of the prostate. Cancer of the prostate is the second most common cause of cancer death in men over age 50. In 2010 the American Cancer Society estimated that one in six men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer and 1 in 36 will die (American Cancer Society, 2010).

Urinary incontinence is an abnormal condition that can occur in both older men and women. Men may be afraid to discuss incontinence with their physician because of embarrassment and because they think that urinary incontinence is a “woman’s disease.” Older women, particularly those who have had children, experience stress incontinence, an involuntary release of urine that occurs when they cough, laugh, sneeze, or lift an object. This is a result of a weakening of the perineal and bladder muscles. Other types of urinary incontinence are urge, overflow, functional, and mixed incontinence. The risk factors for urinary incontinence include age, menopause, diabetes, hysterectomy, stroke, and obesity.

Musculoskeletal System

With aging muscle fibers become smaller. Muscle strength diminishes in proportion to the decline in muscle mass. Beginning in the 30s, bone density and bone mass decline in men and women. Older adults who exercise regularly do not lose as much bone and muscle mass or muscle tone as those who are inactive. Osteoporosis is a major public health threat. An estimated 10 million Americans already have the disease, and an additional 34 million are at risk with low bone mass (National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2010). Postmenopausal women experience a greater rate of bone demineralization than older men. Women who maintain calcium intake throughout life and into menopause have less bone demineralization than women with low calcium intake. Older men with poor nutrition and decreased mobility are also at risk for bone demineralization.

Neurological System

A decrease in the number and size of neurons in the nervous system begins in the middle of the second decade. Neurotransmitters, chemical substances that enhance or inhibit nerve impulse transmission, change with aging as a result of the decrease in neurons. All voluntary reflexes are slower, and individuals often have less of an ability to respond to multiple stimuli. In addition, older adults frequently report alterations in the quality and the quantity of sleep (see Chapter 42), including difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, difficulty falling asleep again after waking during the night, waking too early in the morning, and excessive daytime napping. These problems are believed to be caused by age-related changes in the sleep-wake cycle.

Functional Changes

Physical function is a dynamic process. It changes as individuals interact with their environments. Functional status in older adults includes the day-to-day ADLs involving activities within physical, psychological, cognitive, and social domains. A decline in function can often be linked to illness or disease and its degree of chronicity. However, ultimately it is the complex relationship among all of these areas that influences an older adult’s functional abilities and overall well-being.

Keep in mind that it may be difficult for older adults to accept the changes that occur in all areas of their lives, which in turn have a profound effect on functional status. Some deny the changes and continue to expect the same performance from themselves, regardless of age. Conversely some overemphasize them and prematurely limit their activities and involvement in life. The fear of becoming dependent is an overwhelming one for the older adult who is experiencing functional decline as a result of aging. Educate older adults to promote understanding of age-related changes, appropriate lifestyle adjustments, and effective coping. Factors that promote the highest level of function in all the areas include a healthy, well-balanced diet; paced and appropriate activity; regularly scheduled visits with a health care provider; regular participation in meaningful activities; use of stress management techniques; and avoidance of alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs.

Functional status in older adults refers to the capacity and safe performance of ADLs and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). It is a sensitive indicator of health or illness in the older adult. ADLs (such as bathing, dressing, and toileting) and IADLs (such as the ability to write a check, shop, prepare meals, or make phone calls) are essential to independent living; therefore carefully assess whether or not the older adult has changed the way he or she completes these tasks. Occupational and physical therapists are your best resources for a comprehensive assessment. A sudden change in function, as evidenced by a decline or change in the older adult’s ability to perform any one or combination of ADLs, is often a sign of the onset of an acute illness (e.g., pneumonia, urinary tract infection, or electrolyte imbalance) or worsening of a chronic problem (e.g., diabetes or cardiovascular disease) (Kresevic, 2008).

Health care providers who work in a range of different settings are able to perform functional assessment. Several standardized functional assessment tools are widely available. There is an online collection of the tools used most commonly with older adults at the geriatric nursing website of the American Nurses Association (ANA), www.geronurseonline.org. When you identify a decline in a patient’s function, focus your nursing interventions on maintaining, restoring, and maximizing the older adult’s functional status to maintain independence while preserving dignity.

Cognitive Changes

A common misconception about aging is that cognitive impairments are widespread among older adults. Because of this misconception, older adults often fear that they are, or soon will be, cognitively impaired. Younger adults often assume that older adults will become confused and no longer able to handle their affairs. Forgetfulness as an expected consequence of aging is a myth. Some structural and physiological changes within the brain are associated with cognitive impairment. Reduction in the number of brain cells, deposition of lipofuscin and amyloid in cells, and changes in neurotransmitter levels occur in older adults both with and without cognitive impairment. Symptoms of cognitive impairment such as disorientation, loss of language skills, loss of the ability to calculate, and poor judgment are not normal aging changes and require you to further assess patients for underlying causes. There are standard assessment forms for determining a patient’s mental status, including the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) and the NEECHAM Confusion Scale (Ebersole et al., 2008).

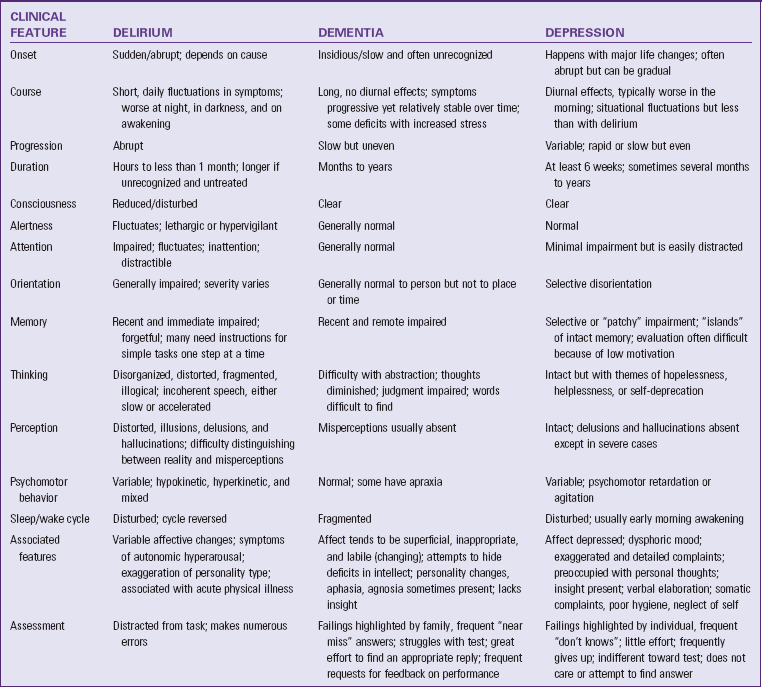

The three common conditions affecting cognition are delirium, dementia, and depression (Table 14-2). Distinguishing among these three conditions is challenging. Complete a careful and thorough assessment of older adults with cognitive changes to distinguish among them. Select appropriate nursing interventions that are specific to the cause of the cognitive impairment.

TABLE 14-2

Comparison of Clinical Features of Delirium, Dementia, and Depression

Modified from Braes T et al: Assessing cognitive function. In Capezuti E et al: Evidence-based geriatric nursing protocols for best practice, ed 3, New York, 2008, Springer.

Delirium

Delirium, or acute confusional state, is potentially a reversible cognitive impairment that often has a physiological cause. Physiological causes include electrolyte imbalances; cerebral anoxia; hypoglycemia; medication effects; tumors; subdural hematomas; and cerebrovascular infection, infarction, or hemorrhage. Delirium in older adults sometimes accompanies systemic infections and is often the presenting symptom for pneumonia or urinary tract infection. Sometimes it is also caused by environmental factors such as sensory deprivation or unfamiliar surroundings or psychosocial factors such as emotional distress or pain. Sleep deprivation is another possible reason for delirium. Although it occurs in any setting, an older adult in the acute care setting is especially at risk because of predisposing factors (physiological, psychosocial, and environmental) in combination with the underlying medical condition. Dementia is an additional risk factor that greatly increases the risk for delirium, and it is possible for delirium and dementia to occur in a patient at the same time. The presence of delirium is a medical emergency and requires prompt assessment and intervention. Nurses are at the bedside 24/7 and in a position to recognize delirium development and report it. The cognitive impairment usually reverses once health care providers identify and treat the cause of delirium.

Dementia

Dementia is a generalized impairment of intellectual functioning that interferes with social and occupational functioning. It is an umbrella term that includes Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body disease, frontal-temporal dementia, and vascular dementia. Cognitive function deterioration leads to a decline in the ability to perform basic ADLs and IADLs. Unlike delirium, a gradual, progressive, irreversible cerebral dysfunction characterizes dementia. Because of the similarity between delirium and dementia, you need to assess carefully to rule out the presence of delirium whenever you suspect dementia.

Nursing management of older adults with any form of dementia always considers the safety and physical and psychosocial needs of the older adult and the family. These needs change as the progressive nature of dementia leads to increased cognitive deterioration. To meet the needs of the older adult, individualize nursing care to enhance quality of life and maximize functional performance by improving cognition, mood, and behavior. Box 14-6 lists general nursing principles for care of older adults with cognitive changes. Support and education about Alzheimer’s disease for patients, families, and professionals can be found at the Alzheimer’s Association website (www.alz.org).

Depression

Approximately one third of older adults experience depressive symptoms (Mental Health America, 2011). Older adults sometimes experience late-life depression, but it is not a normal part of aging. Depression is the most common, yet most undetected and untreated, impairment in older adulthood. Co-occurring diseases may include stroke, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, heart disease, cancer, and pain-provoking diseases such as arthritis. Loss of a significant loved one or a nursing center admission may precipitate depression. Clinical depression is treatable and includes medication, psychotherapy, or a combination of both. Of special note, suicide attempts in older adults are often successful. In fact, suicide in older adults comprises 20% of all suicides (Mental Health America, 2011).

Psychosocial Changes

The psychosocial changes occurring during aging involve life transitions and loss. The longer people live, the more transitions with which they must cope, and the more losses they experience. Life transitions, of which loss is a major component, include retirement and the associated financial changes, changes in roles and relationships, alterations in health and functional ability, changes in one’s social network, and relocation. But the universal loss for older adults usually revolves around the loss of relationships through death.

It is important to assess both the nature of the psychosocial changes that occur in older adults as a result of life transitions and the loss and the adaptations to the changes. During the assessment ask how the older adult feels about self, self in relation to others, and self as one who is aging and what coping methods and skills have been beneficial. Areas to address during the assessment include family, intimate relationships, past and present role changes, finances, housing, social networks, activities, health and wellness, and spirituality. Specific topics related to these areas include retirement, social isolation, sexuality, housing and environment, and death.

Retirement

Many often mistakenly associate retirement with passivity and seclusion. In actuality it is a stage of life characterized by transitions and role changes. This transition requires letting go of certain habits and structure and developing new ones (Touhy and Jett, 2010). The psychosocial stresses of retirement are usually related to role changes with a spouse or within the family and to loss of the work role. Sometimes problems related to social isolation and finances are present. The age of retirement varies. But, whether it occurs at age 55, 65, or 75, it is one of the major turning points in life.

Preretirement planning is an important advisable task. People who plan in advance for retirement generally have a smoother transition. Preretirement planning is more than financial planning. Planning begins with consideration of the “style” of retirement desired and includes an inventory of interests, current skills, and general health. Meaningful retirement planning is critical as the population continues to age.

Retirement affects more than just the retired. It affects the spouse, adult children, and even grandchildren. When the spouse is still working, the retired person faces time alone. There may be new expectations of the retired person. For example, a working spouse might have new ideas about the amount of housework expected of the retired person. Problems develop when the plans of the retired person conflict with the work responsibilities of the working spouse. The roles of the retiree and the working spouse need clarification. Adult children may expect the retired person to always babysit for the grandchildren, forgetting that this is a time for the retired person to pursue other personal interests.

Loss of the work role has a major impact on some retired persons. When so much of life has revolved around work and the personal relationships at work, the loss of the work role can be devastating. Personal identity is often rooted in the work role, and with retirement individuals need to construct a new identity. Individuals also lose the structure imposed on daily life when they no longer have a work schedule. The social exchanges and interpersonal support that occur in the workplace are lost. In the adjustment to retirement the older adult has to develop a personally meaningful schedule and a supportive social network.

Factors that influence the retired person’s satisfaction with life are health status and sufficient income. Positive preretirement expectations also contribute to satisfaction in retirement. The nurse can help the older adult and family prepare for retirement by discussing with them several key areas, including relations with spouse and children; meaningful activities and interests; building social networks; issues related to income; health promotion and maintenance; and long-range planning, including wills and advance directives.

Social Isolation

Many older adults experience social isolation. Isolation is sometimes a choice, the result of a desire not to interact with others. It is also a response to conditions that inhibit the ability or the opportunity to interact such as the lack of access to transportation. Although some older adults choose isolation or a lifelong pattern of reduced interaction with others, older adults who experience social isolation become vulnerable to its consequences. An older adult’s vulnerability increases in the absence of the support of other adults, as occurs with loss of the work role or relocation to unfamiliar surroundings. Impaired sensory function, reduced mobility, and cognitive changes all contribute to reduced interaction with others and can place the older adult at risk for isolation.

You assess patients’ potential for social isolation by identifying their social network, access to transportation, and willingness and desire to interact with others. Your findings assist you in helping a lonely older adult rebuild social networks and reverse patterns of isolation. Many communities have outreach programs designed to make contact with isolated older adults such as Meals on Wheels, which provides nutritional meals. Outreach programs such as daily telephone calls by volunteers or needs for activities such as social outings also meet socialization needs. Social service agencies in most communities welcome older adults as volunteers and provide the opportunity for them to serve while meeting their socialization or other needs. Churches, colleges, community centers, and libraries offer a variety of programs for older adults that increase the opportunity to meet people with similar activities, interests, and needs.

Sexuality

All older adults, whether healthy or frail, need to express their sexual feelings. Sexuality involves love, warmth, sharing, and touching, not just the act of intercourse. Sexuality plays an important role in helping the older adult maintain self-esteem. To help an older adult achieve or maintain sexual health, you need to understand the physical changes in a person’s sexual response (Chapter 34). You need to provide privacy for any discussion of sexuality and maintain a nonjudgmental attitude. Open-ended questions inviting the older adult to explain sexual activities or concerns elicit more information than a list of closed-ended questions about specific activities or symptoms. Include information about the prevention of sexually transmitted infections when appropriate. Sexuality and the need to express sexual feelings remain throughout the human life span.

When considering the older adult’s need for sexual expression, do not ignore the important need to touch and be touched. Touch is an overt expression with many meanings and is an important part of intimacy (Atkinson, 2006). Touch complements traditional sexual methods or serves as an alternative sexual expression when physical intercourse is not desired or possible. Knowing an older adult’s sexual needs allows you to incorporate this information into the nursing care plan.

The sexual preferences of older adults are as diverse as those of the younger population. Clearly not all older adults are heterosexual, yet little research has been done on older adult homosexuals and their health care needs. A number of emerging issues have the potential to substantially affect caregiving in the future, including the demographic changes and the overall aging of the U.S. population, shifts in the nature of families, growing economic pressures, and the societal context of caregiving (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2009). Nurses often find that they are called on to help other health care professionals understand the sexual needs of older adults and advise them. Not all nurses feel comfortable counseling older adults about sexual health and intimacy-related needs. Be prepared to refer older adults to an appropriate professional counselor.

Housing and Environment

The extent of an older adult’s ability to live independently influences housing choices. Changes in social roles, family responsibilities, and health status influence their living arrangements. Some choose to live with family members. Others prefer their own homes or other housing options near their families. Leisure or retirement communities provide older people with living and social opportunities in a one-generation setting. Federally subsidized housing, where available, offers apartments with communal, social, and in some cases food-service arrangements.

The goal of your assessment of a patient’s environment is to consider resources that promote independence and functional ability. When assisting older adults with housing needs, assess their activity level, financial status, access to public transportation and community activities, environmental hazards, and support systems (Touhy and Jett, 2010). When helping patients consider housing choice, anticipate their future needs as much as possible. For example, a housing unit with only one floor and without exterior steps is a prudent choice for the older adult with severe arthritis who has already had lower-extremity joint replacement surgery and anticipates the need for future operations. Assessment of safety, a major component of the older adult’s environment, includes risks within the environment and the older adult’s ability to recognize and respond to the risks (Chapter 27). Safety risks in the home include factors leading to injury such as water heaters set at excessively hot temperatures or environmental barriers such as throw rugs or slippery floor surfaces that could cause a fall. Assess if the person has a pet that could easily move around the person’s feet to cause a fall. Lighting in the home must be assessed. Is the light bright enough to see walkways and stairs, and is there a lit path to the bathroom at night? Conduct a home and environmental check with the person’s family caregiver present if possible.

Housing and environment affect the health of older adults. The environment can support or hinder physical and social functioning, enhance or drain energy, and complement or tax existing physical changes such as vision and hearing. For example, furnishings with red, orange, and yellow colors are easiest for older adults to see. Shiny waxed floors may appear to be wet or have a hole in them. Older adults have difficulty distinguishing between green and blue and among pastel shades. Door frames and baseboards should be a color that contrasts with the color of the wall to improve perception of the boundaries of halls and rooms. Stairs should have a color contrast at the edge of the step so the older person knows where the stair ends. Glare from highly polished floors, metallic fixtures, and windows is difficult for the older adult to tolerate.

Furniture must be comfortable and designed for the musculoskeletal changes of older adults. Older adults need to examine it carefully for size, comfort, and function before purchasing it. It must be easy to get into and out of and provide back support. Test dining room chairs for comfort during meals and for height in relation to the table. Armrests make it easier for patients to get in and out of a chair because they can use their arms to assist in lifting. Older adults often prefer transferring out of a wheelchair to another chair for meals because some styles of wheelchairs do not let older adults sit close enough to the table to eat comfortably. Raising the table to clear the wheelchair arms brings the table closer to the older adult but makes it too high for comfortable use. To make getting out of bed easier and safer, the height of the bed needs to allow the older adult’s feet to be flat on the floor when he or she is sitting on the side of the bed.

Death

Part of one’s life history is the experience of loss through the death of relatives and friends (see Chapter 36). This includes the loss of the older generations of families and sometimes, sadly, the loss of a child. However, death of a spouse is the loss that affects the lives of most older people. The death of a spouse affects older women more than men, a trend that will probably continue in the future. In spite of these experiences, it is wrong to assume that the older adult is comfortable with the idea of death. A key role of the nurse is to help older adults understand the meaning of the loss and cope with it.

Older people have a wide variety of attitudes and beliefs about death, but fear of their own death is uncommon (Friedman, 2006). Rather they are concerned with fear of being a burden, experiencing suffering, being alone, and the use of life-prolonging measures. The stereotype that the death of an older adult is a blessing does not apply to every older adult. Even as death approaches, many older adults still have unfinished business and are not prepared for it. Families and friends are not always ready to let go of him or her. The nurse is often the person to whom the older adult and family members or friends turn to for assistance. Knowledge of the grieving process (see Chapter 36), excellent communication skills; understanding of legal issues; familiarity with community resources; and awareness of one’s own feelings, limitations, and strengths as they relate to care of those confronting death are critical.

Addressing the Health Concerns of Older Adults

As the population ages and life expectancy increases, emphasis on health promotion and disease prevention increases (see Chapter 6). The number of older adults becoming enthusiastic and motivated about these aspects of health is increasing. A number of national programs and projects address preventive practices in the older-adult population. The national initiative Healthy People 2020 (HealthyPeople.gov), has a number of major goals affecting the older adult population, including increasing the number of older adults with one or more chronic conditions who report confidence in maintaining their conditions, reducing the proportion of older adults who have moderate-to-severe functional limitations, reducing the number of emergency department visits resulting from falls among older adults, increasing the number of older adults who live at home but have unmet long-term services and support; and increasing the proportion of older adults with reduced physical or cognitive function who engage in light, moderate, or vigorous leisure-term physical activities. Agencies that serve older adults will continue to collaborate in such efforts to promote health and prevent disease.

The challenges of health promotion and disease prevention for older adults are complex and affect health care providers as well. For the older adult, previous health care experiences, personal motivation, health beliefs, culture, and nonhealth-related factors such as transportation and finances can create barriers to participation. Barriers for health care providers include beliefs and attitudes about which services and programs to provide, their effectiveness and the lack of consistent guidelines, and absence of a coordinated approach. The nurse’s role is to focus interventions on maintaining and promoting patients’ function and quality of life. You can help older adults become empowered to make their own health care decisions and realize their optimum level of health, function, and quality of life (Resnick, 2006) Always be open to recognizing an older adult’s concerns so you can adjust a plan of care accordingly. Although various interventions cross all three levels of care (i.e., health promotion, acute care, and restorative care), some approaches are unique to each level.

Health Promotion and Maintenance: Physiological Concerns

Older adults vary in their desire to participate in health promotion activities; therefore use an individualized approach, taking into account the person’s beliefs about the importance of staying healthy and fit and remaining independent. Researchers have not fully identified the factors that lead to good health in advanced age, but three important factors seem to be genetics, good health habits, and preventive measures. Use creative approaches to incorporate health promotion activities in all health care settings.

The AOA (2009) reports that in 2008 38% of older persons had some type of disability (i.e., difficulty in hearing, vision, cognition, ambulation, self-care, or independent living). Some of these disabilities are relatively minor, but others cause people to require assistance to meet important personal needs. The incidence of disability increases with age. Limitations in ADLs limit the ability to live independently. The ADL limitations most often reported include walking, showering and bathing, getting in and out of bed and chair, dressing, toileting, and eating. There is a strong relationship between disability status and reported health status. The effect of chronic conditions on the lives of older adults varies widely, but in general chronic conditions further diminish well-being and a sense of independence. Direct nursing interventions at managing these conditions and educating family caregivers in ways to give appropriate support. It is also important to focus interventions on prevention. General preventive measures for you to recommend to older adults include:

• Participation in screening activities (e.g., blood pressure, mammography, Pap smears, depression, vision and hearing testing, colonoscopy)

• Weight reduction if overweight

• Eating a low-fat, well-balanced diet

• Immunization for seasonal influenza, tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis, shingles, and pneumococcal disease

Those who die from influenza are predominately older adults. A debate currently centers about influenza deaths and the older adult. Do older adults die because of influenza or is the death related to worsening of a chronic illness and influenza? However, providers continue to strongly recommend annual immunization of all older adults for influenza, with special emphasis on residents of nursing homes or residential or long-term care facilities. Not all older adults are current with their booster injections, and some never received the primary series of injections. Ask older adults about the current status of all immunizations, provide information about the immunizations, and make arrangements for the older adult to receive the immunizations as needed.

Most older adults are interested in their health and are capable of taking charge of their lives. They want to remain independent and prevent disability (Fig. 14-1). Initial screenings establish baseline data that you use to determine wellness, identify health needs, and design health maintenance programs. Following initial screening sessions, share with older adults information on nutrition, exercise, medications, and safety precautions. You can also provide information on specific conditions such as hypertension, arthritis, or self-care procedures such as foot and skin care. By providing information about health promotion and self-care, you significantly improve the health and well-being of older adults.

Heart Disease

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in older adults (CDC, 2010a). Common cardiovascular disorders are hypertension and coronary artery disease. Hypertension is a silent killer because often the person is unaware that his or her blood pressure is elevated (see Chapter 29). Although over half of Americans have elevated diastolic and/or systolic pressures, the fact that hypertension is common does not make it normal or harmless. Treatment of systolic pressures 160 mm Hg or higher is linked to reduced incidence of myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure. In coronary artery disease partial or complete blockage of one or more coronary arteries leads to myocardial ischemia and myocardial infarction. The risk factors for both hypertension and coronary artery disease include smoking, obesity, lack of exercise, and stress. Additional risk factors for coronary artery disease include hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus. Nursing interventions for hypertension and coronary artery disease address weight reduction, exercise, dietary changes, limiting salt and fat intake, stress management, and smoking cessation. Patient teaching also includes information about medication management, blood-pressure monitoring, and the symptoms indicating the need for emergency care.

Cancer

Malignant neoplasms are the second most common cause of death among older adults (CDC, 2010a). Nurses educate older adults about early detection, treatment, and cancer risk factors. Examples include smoking cessation, teaching breast self-examination (see Chapter 30), and encouraging all older adults to have annual screening for fecal occult blood with a rectal examination. It is also important to educate older adults about the signs of cancer and encourage prompt reporting of nonhealing skin lesions, unexpected bleeding, change in bowel habits, nagging cough, lump in breast or another part of body, change in a mole, difficulty swallowing, and unexplained weight loss. Cancer is difficult to detect because providers often mistake symptoms as part of the normal aging process or signs of a person’s chronic disease. You need to carefully distinguish between signs of normal aging and signs of pathological conditions.

Stroke (Cerebrovascular Accident)

Cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs) continue to be the third leading cause of death in the United States and occur as brain ischemia (inadequate blood supply to areas of brain caused by arterial blockage) or brain hemorrhage (subarachnoid or intercerebral bleeds) (CDC, 2010a). Risk factors for CVAs include hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, history of transient ischemic attacks, and family history of cardiovascular disease. CVAs often impair the functional abilities of older adults and lead to the inability to live independently. The scope of nursing interventions ranges from teaching older adults about risk-reduction strategies to teaching family caregivers the early warning signs of a stroke and ways to support a patient during recovery and rehabilitation.

Smoking

Cigarette smoking is a risk factor among the four most common causes of death: heart disease, cancer, stroke, and lung disease. Smoking is the most preventable cause of disease and death in the United States. As of 2009 an estimated 9.5% of people ages 65 and older smoked cigarettes (CDC, 2010b). Approximately 440,000 people die annually from smoking-related diseases, and 300,000 of those deaths occur in people ages 65 and older (CMS, 2010).

Smoking cessation is a health promotion strategy for older adults just as it is for younger adults. Older smokers still benefit from smoking cessation. In addition to reducing risk, it sometimes stabilizes existing conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and coronary artery disease. Smoking cessation after age 65 can add 2 to 3 years to life expectancy. Within a year of quitting, former smokers reduce their risk of coronary heart disease by 50% (National Cancer Institute, 2010). Smoking-cessation programs recommended by the CDC (2008) include individual, group, and telephone counseling and the use of nicotine (gum and patch) or nonnicotine medications. If the patient rejects smoking cessation, suggest at least a reduction in smoking. Finally, arrange with the older adult a quit or reduction date and a follow-up visit or contact to discuss the quit attempt. At follow-up visits, offer encouragement and assistance in modifying the plan as necessary.

Alcohol Abuse

Alcoholism can be found in older adults. Alcohol is inexpensive, legal, and accessible. Studies of alcohol abuse in older adults report two patterns: a lifelong pattern of heavy drinking that continues and a pattern when heavy drinking begins late in life. Frequently cited causes of excessive alcohol use are depression, loneliness, and lack of social support.

Alcohol abuse may be underidentified in older adults. The clues to creating suspicion of alcohol abuse are subtle, and coexisting dementia or depression sometimes complicates the assessment. Suspicion of alcohol abuse increases when there is a history of repeated falls and accidents, social isolation, recurring episodes of memory loss and confusion, failure to meet home and work obligations, a history of skipping meals or medications, and difficulty managing household tasks and finances. When you suspect that an older adult is abusing alcohol, realize that a variety of treatment needs are present. Treatment includes age-specific approaches that acknowledge the stresses experienced by the older adult and encourage involvement in activities that match the older adult’s interests and increase feelings of self-worth. The identification and treatment of co-existing depression are also important. The continuum of interventions can range from simple education to formalized treatment programs that include pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and rehabilitation.

Nutrition

Lifelong eating habits and situational factors influence how older adults meet their needs for good nutrition. Lifelong eating habits based in tradition, ethnicity, and religion influence the choice of what foods are eaten and how they are prepared. Situational factors affecting nutrition include access to grocery stores, finances, physical and cognitive capability for food preparation, and a place to store food and prepare meals. Older adults’ levels of activity and clinical conditions affect their nutritional needs. Level of activity has implications for the total amount of required calories. Older adults who are sedentary usually need fewer calories than those who are more active. However, activity alone does not determine caloric requirements. Additional calories are often necessary in clinical situations such as recovery from surgery, whereas fewer calories are necessary when the older adult has diabetes or is overweight.

Good nutrition for older adults includes appropriate caloric intake and limited intake of fat, salt, refined sugars, and alcohol. The nutritional guidelines displayed in the USDA’s MyPlate (see Chapter 44) are the basic recommendations for older-adult nutrition. Protein intake is sometimes lower than recommended if older adults have reduced financial resources or limited access to grocery stores. Difficulty chewing meat because of poor dentition or poor-fitting dentures also limits protein intake. Fat intake is higher than usual because of the substitution of fast-food restaurant meals for meals prepared at home or because of methods of cooking featuring fried foods and sauces using butter and cream. Some use extra salt and sugar while cooking or at the table to compensate for a diminished sense of taste.

Older adults with dementia have special nutritional needs. As their memory and functional skills decline with the progression of dementia, they lose the ability to remember when to eat, how to prepare food, and how to feed themselves. Caloric needs may increase because of the energy expended in pacing and wandering activities. When caring for older adults with dementia, routinely monitor weight and food intake, serve food that is easy to eat such as finger foods (e.g., chicken strips, sandwiches, cut-up vegetables, and fruit), provide assistance with eating, and offer food supplements that are tasty and easy to swallow.

Dental Problems

Dental problems with natural teeth and dentures are common in older adults. Dental caries, gingivitis, broken or missing teeth, and ill-fitting or missing dentures affect nutritional adequacy, cause pain, and lead to infection. Dentures are a frequent problem because the cost is not covered by Medicare and dentures tend to be quite expensive. Help prevent dental and gum disease through education about routine dental care (see Chapter 39).

Exercise

Encourage older adults to maintain physical exercise and activity. The primary benefits of exercise include maintaining and strengthening functional ability and promoting a sense of enhanced well-being. Regular daily exercise such as walking builds endurance, increases muscle tone, improves joint flexibility, strengthens bones, reduces stress, and contributes to weight loss. Other benefits include improvement of cardiovascular function, improved plasma lipoprotein profiles, increased metabolic rate, increased gastrointestinal transit time, prevention of depressive illness, and improved sleep quality. Older adults who participate in group exercise programs or physical therapy may experience improved mobility, gait, and balance, resulting in fewer falls (Michael et al., 2010).

Consult with physical therapists and the patient’s physician to plan an exercise program that meets physical needs and is one the patient enjoys. Consider the patient’s physical limitations and encourage the older adult to stick with the exercise program. Many factors influence an individual’s willingness to participate in an exercise program. These include general beliefs about benefits of exercise, past experiences with exercise, personal goals, personality, and any unpleasant sensations associated with exercise.