Mobility and Immobility

• Describe the functions of the musculoskeletal (skeleton, skeletal muscles) and nervous systems in the regulation of movement.

• Discuss physiological and pathological influences on body alignment and joint mobility.

• Identify changes in physiological and psychosocial function associated with mobility and immobility.

• Assess for correct and impaired body alignment and mobility.

• Formulate appropriate nursing diagnoses for impaired body alignment and mobility.

• Develop individualized nursing care plans for patients with impaired body alignment and mobility.

• Discuss the importance of no-lift policies for the patient and health care provider.

• Describe equipment needed for safe patient handling and movement.

• Discuss the impact of national patient safety resources, initiatives, and regulations in relation to patient handling and movement.

• Compare and contrast active and passive range-of-motion exercises.

• Evaluate the nursing plan for maintaining body alignment and mobility.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

People use mobility for many purposes (e.g., expression of emotions or satisfaction of basic needs with nonverbal gestures). It is also used to show self-defense, perform activities of daily living (ADLs), and participate in recreational activities. Many functions of the body depend on mobility. Intact musculoskeletal and nervous systems are necessary for optimal physical mobility and functioning.

Clinical nursing practice related to mobility and immobility requires the incorporation of scientific and nursing knowledge and skills to provide competent care. Knowing the movements and functions of muscles in maintaining posture and movement and implementing evidence-based knowledge about safe patient handling are essential to protecting the safety of both the patient and the nurse.

Scientific Knowledge Base

Movement is a complex process that requires coordination between the musculoskeletal and nervous systems. Body mechanics is a term used to describe the coordinated efforts of the musculoskeletal and nervous systems. Although nurses need to understand the physics surrounding body mechanics, lifting techniques historically used in nursing practice that emphasize body mechanics often cause debilitating injuries to nursing and other health care staff (de Castro et al., 2006). Today nurses use information about body alignment, balance, gravity, and friction when implementing nursing interventions such as positioning patients, determining the risk of patient falls, and selecting the safest way to move or transfer patients.

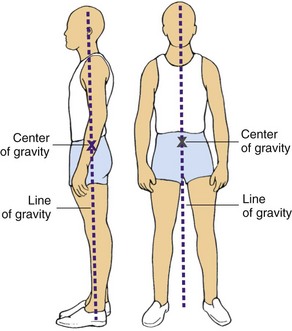

Alignment and Balance

The terms body alignment and posture are similar and refer to the positioning of the joints, tendons, ligaments, and muscles while standing, sitting, and lying. Body alignment means that the individual’s center of gravity is stable. Correct body alignment reduces strain on musculoskeletal structures, aids in maintaining adequate muscle tone, promotes comfort, and contributes to balance and conservation of energy. Without balance control the center of gravity is displaced, thus creating a risk for falls and subsequent injuries. Balance is enhanced by keeping the center of gravity of the body low with a wide base of support and maintaining correct body posture.

Individuals require balance for maintaining a static position (e.g., sitting) and moving (e.g., walking). Disease, injury, pain, physical development (e.g., age), and life changes (e.g., pregnancy) compromise the ability to remain balanced. Medications that cause dizziness and prolonged immobility also affect balance. Impaired balance is a major threat to physical safety and contributes to a fear of falling and self-imposed restrictions on activity.

Gravity and Friction

Weight is the force exerted on a body by gravity. The force of weight is always directed downward, which is why an unbalanced object falls. Unsteady patients fall if their center of gravity becomes unbalanced because of the gravitational pull on their weight.

To lift safely the lifter has to overcome the weight of the object and know its center of gravity. In symmetrical inanimate objects the center of gravity is at the exact center of the object. However, people are not geometrically perfect; their centers of gravity are usually at 55% to 57% of standing height and are in the midline, which is why only using principles of body mechanics in lifting patients often leads to injury of the nurse or health care professional.

Friction is a force that occurs in a direction to oppose movement. The greater the surface area of the object that is moved, the greater the friction. A larger object produces greater resistance to movement. In addition, the force exerted against the skin while the skin remains stationary and the bony structures move is called shear. Unfortunately a common example is when the head of the bed is elevated beyond 60 degrees and gravity pulls the bony skeleton toward the foot of the bed while the skin remains against the sheets. The blood vessels in the underlying tissue are stretched and damaged, resulting in impeded blood flow to the deep tissues. Ultimately pressure ulcers often develop within the undermined tissue; the surface tissue appears less affected. To decrease surface area and reduce friction when patients are unable to assist with moving up in bed, nurses use an ergonomic assistive device such as a full body sling. This sling mechanically lifts the patient off the surface of the bed, thereby preventing friction, tearing, or shearing his or her delicate skin, and protects the nurse and other staff from injury (Nelson et al., 2009).

Physiology and Regulation of Movement

The skeleton provides attachments for muscles and ligaments and the leverage necessary for movement. Thus the skeleton is the supporting framework of the body and is made up of four types of bones: long, short, flat, and irregular. Long bones contribute to height (e.g., the femur, fibula, and tibia in the leg) and length (e.g., the phalanges of the fingers and toes). Short bones (e.g., the carpal bones in the foot and the patella in the knee) occur in clusters and, when combined with ligaments and cartilage, permit movement of the extremities. Flat bones (e.g., some bones in the skull and the ribs in the thorax) provide structural contour. Irregular bones make up the vertebral column and some bones of the skull such as the mandible.

Bones are further characterized by firmness, rigidity, and elasticity. Firmness results from inorganic salts such as calcium and phosphate that are in the bone matrix. It is related to the rigidity of the bone, which is necessary to keep long bones straight and enables bones to withstand weight bearing. In addition, bones have a degree of elasticity and skeletal flexibility that change with age. For example, the newborn has a large amount of cartilage and is highly flexible but is unable to support weight. The toddler’s bones are more pliable than those of an older person and are better able to withstand falls. Older adults, especially women, are more susceptible to bone loss (resorption) and osteoporosis, which increase the risk of fractures.

The skeletal system has several functions. It protects vital organs (e.g., the skull around the brain and the ribs around the heart and lungs) and aids in calcium regulation. Bones store calcium and release it into the circulation as needed. Patients with decreased calcium regulation and metabolism are at risk for developing osteoporosis and pathological fractures (fractures caused by weakened bone tissue). In addition, the internal structure of long bones contains bone marrow, participates in red blood cell (RBC) production, and acts as a reservoir for blood. Patients with altered bone marrow function or diminished RBC production fatigue easily because of reduced hemoglobin and oxygen-carrying ability. This fatigue decreases their mobility and increases the risk for falling.

Joints: Joints are the connections between bones. Each joint is classified according to its structure and degree of mobility. There are four classifications of joints: synostotic, cartilaginous, fibrous, and synovial.

The synostotic joint refers to bones jointed by bones. No movement is associated with this type of joint, and the bony tissue that forms between the bones provides strength and stability. The classic example of this type of joint is the skull, where fusion of the joint occurs later in life (Fig. 47-1, A).

In the cartilaginous joint, or synchondrosis joint, cartilage unites bony components. This type of joint allows for bone growth while providing stability. When bone growth is complete, the joints ossify. The first sternocostal joint is an example of a synchondrosis joint (Fig. 47-1, B).

The fibrous joint, or syndesmosis joint, is a joint in which a ligament or membrane unites two bony surfaces. The fibers of ligaments are flexible and stretch, permitting a limited amount of movement. The paired bones of the lower leg (tibia and fibula) are syndesmotic joints (Huether and McCance, 2008) (Fig. 47-1, C).

The synovial joint, or true joint, is a freely movable joint in which contiguous bony surfaces are covered by articular cartilage and connected by ligaments lined with a synovial membrane. Joining of the humeral radius and ulna by cartilage and ligaments forms a pivotal joint (Fig. 47-1, D). Other types of synovial joints are the ball-and-socket joints such as the hip joint and the hinge joints such as the interphalangeal joints of the fingers.

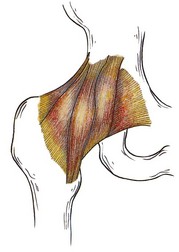

Ligaments: Ligaments are white, shiny, flexible bands of fibrous tissue binding joints together and connecting bones and cartilages. Ligaments are elastic and aid joint flexibility and support (Fig. 47-2). In addition, some ligaments have a protective function. For example, ligaments between the vertebral bodies and the ligamentum flavum prevent damage to the spinal cord during movement of the back.

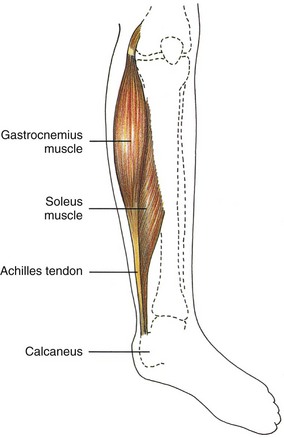

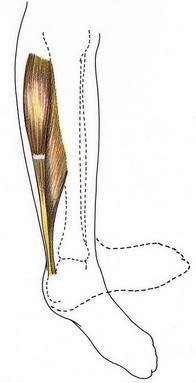

Tendons: Tendons are white, glistening, fibrous bands of tissue that connect muscle to bone. They are strong, flexible, and inelastic; and they occur in various lengths and thicknesses. The Achilles tendon (tendo calcaneus) is the thickest and strongest tendon in the body. It begins near the midposterior of the leg and attaches the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles in the calf to the calcaneal bone in the back of the foot (Fig. 47-3).

Cartilage: Cartilage is nonvascular (without blood vessels) supporting connective tissue located chiefly in the joints and thorax, trachea, larynx, nose, and ear. The fetus has a large amount of temporary cartilage, which is replaced by bone developed during infancy. Permanent cartilage is unossified (not hardened), except in advanced age and diseases such as osteoarthritis.

Joints, ligaments, tendons, and cartilage facilitate strength and flexibility of the skeleton. Strength enables the skeletal system to support the body. A person’s flexibility is demonstrated through range of motion (ROM). However, strength and flexibility do not result entirely from these four structures. Adequate skeletal muscle is also necessary.

Skeletal Muscle

Movement of bones and joints involves active processes that are carefully integrated to achieve coordination. Skeletal muscles, because of their ability to contract and relax, are the working elements of movement. Anatomical structure and attachment to the skeleton enhance contractile elements of the skeletal muscle.

Muscles are made of fibers that contract when stimulated by an electrochemical impulse that travels from the nerve to the muscle across the neuromuscular junction. The electrochemical impulse causes the filaments (predominantly protein molecules of myosin and actin) within the fiber to slide past one another, with the filaments changing length.

Muscle contractions are categorized by functional purpose: moving, resisting, or stabilizing body parts. In concentric tension increased muscle contraction causes muscle shortening, resulting in movement such as when a patient uses an overhead trapeze to pull up in bed. Eccentric tension helps control the speed and direction of movement. For example, when using an overhead trapeze, the patient slowly lowers himself to the bed. The lowering is controlled when the antagonistic muscles lengthen. Concentric and eccentric muscle actions are necessary for active movement and therefore are referred to as dynamic or isotonic contraction. Isometric contraction (static contraction) causes an increase in muscle tension or muscle work but no shortening or active movement of the muscle (e.g., instructing the patient to tighten and relax a muscle group, as in quadriceps set exercises or pelvic floor exercises). Voluntary movement is a combination of isotonic and isometric contractions.

Although isometric contractions do not result in muscle shortening, energy expenditure increases. This type of muscle work is comparable to having a car in neutral with the driver continually depressing the accelerator and racing the engine. The driver is not going anywhere but expends a large amount of energy. It is important to understand the energy expenditure (increased respiratory rate and increased work on the heart) associated with isometric exercises because the exercises are sometimes contraindicated in certain patients’ illnesses (e.g., myocardial infarction or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease).

Muscle Movement and Posture: Muscles that attach to bones of leverage provide necessary strength to move an object. Leverage is an inducing or compelling force and occurs when specific bones such as the humerus, ulna, and radius and the associated joint such as the elbow act together as a lever. Force is applied to one end of the bone to lift a weight as another point rotates the bone in the opposite direction.

Muscles associated primarily with maintaining posture are short and featherlike in appearance because they converge obliquely at a common tendon. Muscles of the lower extremities, trunk, neck, and back are concerned primarily with posture (the position of the body in relation to the surrounding space). These muscle groups work together to stabilize and support body weight, and they allow an individual to maintain a sitting or standing posture.

Muscle Regulation of Posture and Movement: Posture and movement depend on the skeleton and the shape and development of skeletal muscles. They also contribute to musculoskeletal function and often reflect personality, discomfort, and mood. For example, a person with a dramatic personality gestures with the hands, a person who is fatigued or depressed may slouch, and a person with abdominal pain may curl into a fetal-like position.

Coordination and regulation of different muscle groups depend on muscle tone and activity of antagonistic, synergistic, and antigravity muscles (see Chapter 38). Muscle tone, or tonus, is the normal state of balanced muscle tension. The body achieves tension by alternating contraction and relaxation without active movement of neighboring fibers of a specific muscle group. Muscle tone helps maintain functional positions such as sitting or standing without excess muscle fatigue and is maintained through continual use of muscles. ADLs require muscle action and help maintain muscle tone. When a patient is immobile or on prolonged bed rest, activity level, activity tolerance, and muscle tone decrease.

Nervous System

The nervous system regulates movement and posture. The precentral gyrus, or motor strip, is the major voluntary motor area and is in the cerebral cortex. A majority of motor fibers descend from the motor strip and cross at the level of the medulla. Thus the motor fibers from the right motor strip initiate voluntary movement for the left side of the body, and motor fibers from the left motor strip initiate voluntary movement for the right side of the body.

During voluntary movement impulses descend from the motor strip to the spinal cord. An impulse exits the spinal cord through efferent motor nerves and travels through the nerves. Through a complex process neurotransmitters, or chemicals such as acetylcholine, transfer electric impulses from the nerve across the neuromuscular junction to the muscle. The neurotransmitter reaches a muscle and stimulates it, causing movement. Movement is impaired by disorders that alter neurotransmitter production, transfer of impulses from the nerve to the muscle, or activation of muscle activity. Parkinsonism is an example of such a disorder (see Chapter 38).

Pathological Influences on Mobility

Many pathological conditions affect mobility. Although a complete description of each is beyond the scope of this chapter, an overview of four pathological influences are presented.

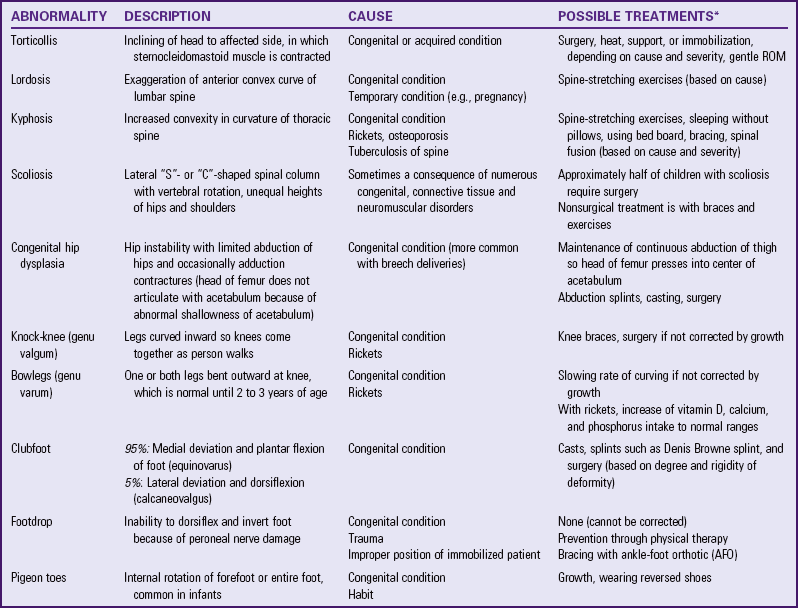

Postural Abnormalities

Congenital or acquired postural abnormalities affect the efficiency of the musculoskeletal system and body alignment, balance, and appearance. During assessment observe body alignment and ROM (see Chapter 38). Postural abnormalities can cause pain, impair alignment or mobility, or both. Knowledge about the characteristics, causes, and treatment of common postural abnormalities is necessary for lifting, transfer, and positioning (Table 47-1). Some postural abnormalities limit ROM. Nurses intervene to maintain maximum ROM in unaffected joints and then design interventions to strengthen affected muscles and joints, improve the patient’s posture, and adequately use affected and unaffected muscle groups. Referral to and/or collaboration with a physical therapist enhances the nurse’s interventions for a patient with a postural abnormality.

Muscle Abnormalities

Injury and disease lead to numerous alterations in musculoskeletal function. For example, the muscular dystrophies are a group of familial disorders that cause degeneration of skeletal muscle fibers. They are the most prevalent of the muscle diseases in childhood. Patients with muscular dystrophy experience progressive, symmetrical weakness and wasting of skeletal muscle groups, with increasing disability and deformity (McCance and Huether, 2009).

Damage to the Central Nervous System

Damage to any component of the central nervous system that regulates voluntary movement results in impaired body alignment, balance, and mobility. Trauma from a head injury, ischemia from a stroke or brain attack (cerebrovascular accident [CVA]), or bacterial infection such as meningitis can damage the cerebellum or the motor strip in the cerebral cortex. Damage to the cerebellum causes problems with balance, and motor impairment is directly related to the amount of destruction of the motor strip. For example, a person with a right-sided cerebral hemorrhage with necrosis has destruction of the right motor strip that results in left-sided hemiplegia. Trauma to the spinal cord also impairs mobility. For example, a complete transection of the spinal cord results in a bilateral loss of voluntary motor control below the level of the trauma because motor fibers are cut.

Direct Trauma to the Musculoskeletal System

Direct trauma to the musculoskeletal system results in bruises, contusions, sprains, and fractures. A fracture is a disruption of bone tissue continuity. Fractures most commonly result from direct external trauma, but they also occur as a consequence of some deformity of the bone (e.g., pathological fractures of osteoporosis, Paget’s disease, or osteogenesis imperfecta). Young children are usually able to form new bone more easily than adults and, as a result, have few complications after a fracture. Treatment often includes positioning the fractured bone in proper alignment and immobilizing it to promote healing and restore function. Even this temporary immobilization results in some muscle atrophy, loss of muscle tone, and joint stiffness.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Fully understanding movement and mobility requires more than an overview of movement and the physiology and regulation of movement by the musculoskeletal and nervous systems. You need to know how to apply these scientific principles in the clinical setting to determine the safest way to move patients and to understand the effect of immobility on the physiological, psychosocial, and developmental aspects of patient care.

Safe Patient Handling

Nurses are exposed to the hazards related to lifting and transferring patients in many settings such as inpatient nursing units, long-term care facilities, and the operating room (de Castro et al., 2006). Manually lifting and transferring patients contributes to the high incidence of work-related musculoskeletal problems and back injuries in nurses and other health care staff (Nelson and Baptiste, 2006). Current evidence shows that many nurses frequently transfer to different positions and leave the profession because of work-related injuries (de Castro et al., 2006). Implementing evidence-based interventions and programs (e.g., lift teams) reduces the number of work-related injuries, which improves the health of the nurse and reduces indirect costs to the health care agency (e.g., workers’ compensation and replacing injured workers).

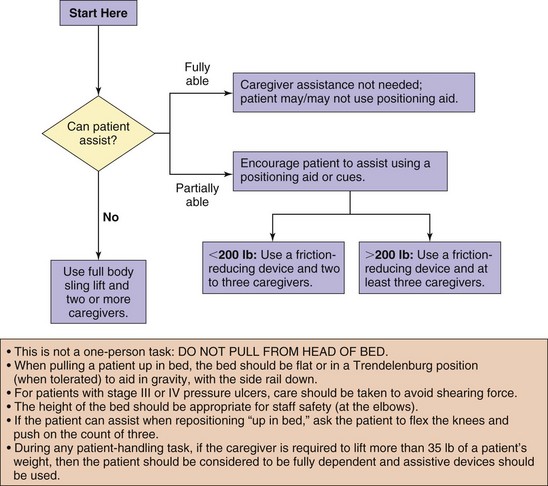

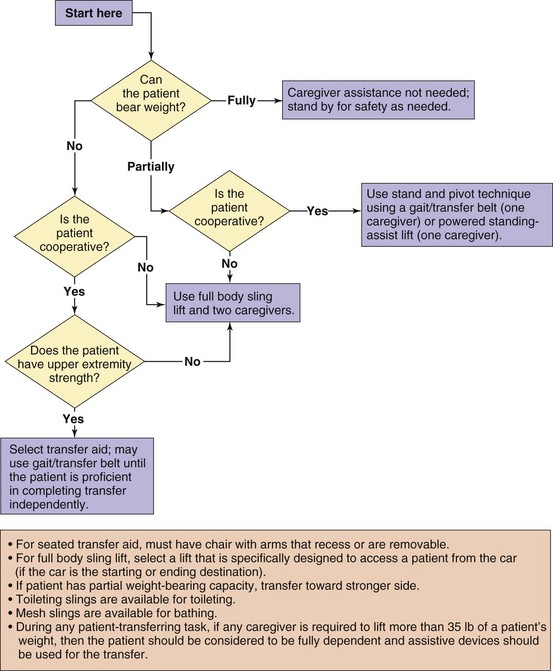

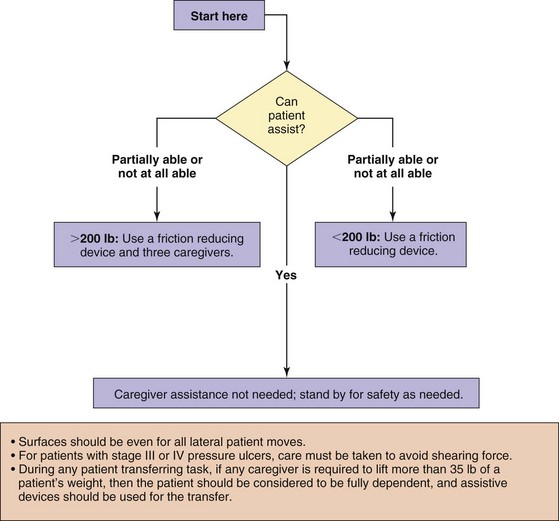

Today many states have laws that mandate safe patient handling in health care agencies. Health care agencies are implementing comprehensive safe patient–handling programs in all parts of the United States. Comprehensive safe patient–handling programs include the following elements: an ergonomics assessment protocol for health care environments, patient assessment criteria, algorithms for patient handling and movement, special equipment kept in convenient locations to help transfer patients, back injury resource nurses, an “after-action review” that allows the health care team to apply knowledge about moving patients safely in different settings, and a no-lift policy (Nelson, 2006).

Factors Influencing Mobility-Immobility

To determine how to move patients safely, assess their ability to move. Mobility refers to a person’s ability to move about freely, and immobility refers to the inability to do so. Some patients can be mobile or immobile, whereas others experience varying degrees of partial immobility. Think of mobility as a continuum, with mobility on one end, immobility on the other, and varying degrees of partial immobility between the end points. Some patients move back and forth between mobility and immobility, but for others immobility is absolute and continues indefinitely. The terms bed rest and impaired physical mobility are used frequently when discussing patients on the mobility-immobility continuum.

Bed rest is an intervention that restricts patients to bed for therapeutic reasons. Nurses and health care providers most often prescribe this intervention. Bed rest has many different interpretations among health care professionals. Patients with a wide variety of conditions are placed on bed rest. The duration of bed rest depends on the illness or injury and the patient’s prior state of health.

The effects of muscular deconditioning associated with lack of physical activity are often apparent in a matter of days. This cluster of symptoms is often referred to as the “hazards of immobility.” The individual of average weight and height without a chronic illness on bed rest loses muscle strength from baseline levels at a rate of 3% a day. Immobility also is associated with cardiovascular, skeletal, and other organ changes. The term disuse atrophy describes the tendency of cells and tissue to reduce in size and function in response to prolonged inactivity resulting from bed rest, trauma, casting, or local nerve damage (McCance and Huether, 2009).

Periods of immobility or prolonged bed rest cause major physiological, psychological, and social effects. These effects are gradual or immediate and vary from patient to patient. The greater the extent and the longer the duration of immobility, the more pronounced the consequences. The patient with complete mobility restrictions is continually at risk for the hazards of immobility.

Systemic Effects

All body systems work more efficiently with some form of movement. Exercise has positive outcomes for all major systems of the body. When there is an alteration in mobility, each body system is at risk for impairment. The severity of the impairment depends on the patient’s overall health, degree and length of immobility, and age. For example, older adults with chronic illnesses develop pronounced effects of immobility more quickly than do younger patients with the same immobility problem.

Metabolic Changes: Changes in mobility alter endocrine metabolism, calcium resorption, and functioning of the gastrointestinal system. The endocrine system, made up of hormone-secreting glands, maintains and regulates vital functions such as (1) response to stress and injury; (2) growth and development; (3) reproduction; (4) maintenance of the internal environment; and (5) energy production, use, and storage.

When injury or stress occurs, the endocrine system triggers a series of responses aimed at maintaining blood pressure and preserving life. It is important in maintaining homeostasis. Tissues and cells live in an internal environment that the endocrine system helps regulate through maintenance of sodium, potassium, water, and acid-base balance. It also regulates energy metabolism. Thyroid hormone increases the basal metabolic rate (BMR), and energy becomes available to cells through the integrated action of gastrointestinal and pancreatic hormones (McCance and Huether, 2009).

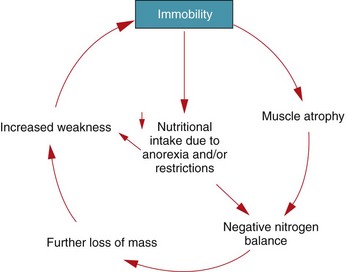

Immobility disrupts normal metabolic functioning: decreasing the metabolic rate; altering the metabolism of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins; causing fluid, electrolyte, and calcium imbalances; and causing gastrointestinal disturbances such as decreased appetite and slowing of peristalsis. However, in the presence of an infectious process, immobilized patients often have an increased BMR as a result of fever or wound healing because these increase cellular oxygen requirements (Huether and McCance, 2008).

A deficiency in calories and protein is characteristic of patients with a decreased appetite secondary to immobility. The body is constantly synthesizing proteins and breaking them down into amino acids to form other proteins (see Chapter 41). When the patient is immobile, his or her body often excretes more nitrogen (the end product of amino acid breakdown) than it ingests in proteins, resulting in negative nitrogen balance (Fig. 47-4). Weight loss, decreased muscle mass, and weakness result from tissue catabolism (tissue breakdown) (McCance and Huether, 2009).

FIG. 47-4 Factors contributing to negative nitrogen balance associated with immobility. (From Gröer MW, Shekleton ME: Basic pathophysiology: a holistic approach, ed 3, St Louis, 1989, Mosby.)

Another metabolic change associated with immobility is calcium resorption (loss) from bones. Immobility causes the release of calcium into the circulation. Normally the kidneys excrete the excess calcium. However, if the kidneys are unable to respond appropriately, hypercalcemia results. Pathological fractures occur if calcium resorption continues as the patient remains on bed rest or continues to be immobile (Huether and McCance, 2008).

Impairments of gastrointestinal functioning caused by decreased mobility vary. Difficulty in passing stools (constipation) is a common symptom, although pseudodiarrhea often results from a fecal impaction (accumulation of hardened feces). Be aware that this finding is not normal diarrhea, but rather liquid stool passing around the area of impaction (see Chapter 46). Left untreated, fecal impaction results in a mechanical bowel obstruction that partially or completely occludes the intestinal lumen, blocking normal propulsion of liquid and gas. The resulting fluid in the intestine produces distention and increases intraluminal pressure. Over time intestinal function becomes depressed, dehydration occurs, absorption ceases, and fluid and electrolyte disturbances worsen.

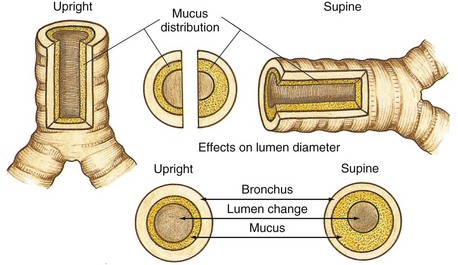

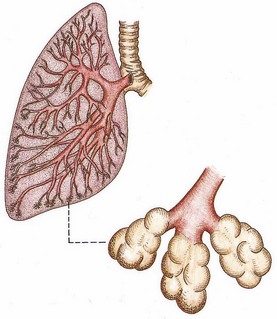

Respiratory Changes: Regular aerobic exercise enhances respiratory functioning. Lack of movement and exercise places patients at higher risk for respiratory complications. Patients who are immobile are at high risk for developing pulmonary complications. The most common respiratory complications are atelectasis (collapse of alveoli) and hypostatic pneumonia (inflammation of the lung from stasis or pooling of secretions). Both decreased oxygenation and prolonged recovery add to the patient’s discomfort (Lewis et al., 2011). In atelectasis secretions block a bronchiole or a bronchus; and the distal lung tissue (alveoli) collapses as the existing air is absorbed, producing hypoventilation. The site of the blockage affects the severity of atelectasis. Sometimes an entire lung lobe or a whole lung collapses. At some point in the development of these complications, there is a proportional decline in the patient’s ability to cough productively. Ultimately the distribution of mucus in the bronchi increases, particularly when the patient is in the supine, prone, or lateral position (Fig. 47-5). Mucus accumulates in the dependent regions of the airways (Fig. 47-6). Hypostatic pneumonia frequently results because mucus is an excellent place for bacteria to grow.

Cardiovascular Changes: Immobilization also affects the cardiovascular system. The three major changes are orthostatic hypotension, increased cardiac workload, and thrombus formation.

Orthostatic hypotension is an increase in heart rate of more than 15% and a drop of 15 mm Hg or more in systolic blood pressure or a drop of 10 mm Hg or more in diastolic blood pressure when the patient changes from the supine to standing position (Huether and McCance, 2008). In the immobilized patient decreased circulating fluid volume, pooling of blood in the lower extremities, and decreased autonomic response occur. These are especially evident in the older adult.

As the workload of the heart increases, so does its oxygen consumption. Therefore the heart works harder and less efficiently during periods of prolonged rest. As immobilization increases, cardiac output falls, further decreasing cardiac efficiency and increasing workload.

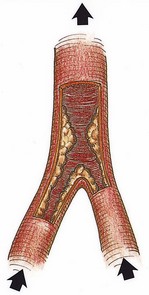

Patients who are immobile are also at risk for thrombus formation. A thrombus is an accumulation of platelets, fibrin, clotting factors, and the cellular elements of the blood attached to the interior wall of a vein or artery, which sometimes occludes the lumen of the vessel (Fig. 47-7). Three factors contribute to venous thrombus formation: (1) damage to the vessel wall (e.g., injury during surgical procedures), (2) alterations of blood flow (e.g., slow blood flow in calf veins associated with bed rest), and (3) alterations in blood constituents (e.g., a change in clotting factors or increased platelet activity). These three factors are often referred to as Virchow’s triad (Huether and McCance, 2008).

Musculoskeletal Changes: The effects of immobility on the musculoskeletal system include permanent or temporary impairment or permanent disability. Restricted mobility sometimes results in loss of endurance, strength, and muscle mass and decreased stability and balance. Other effects of restricted mobility affecting the skeletal system are impaired calcium metabolism and joint mobility.

Muscle Effects: Because of protein breakdown, the patient loses lean body mass. The reduced muscle mass is unable to sustain activity without increased fatigue. If immobility continues and the patient does not exercise, there is further loss of muscle mass. Muscle weakness always occurs with immobility, and prolonged immobility often leads to disuse atrophy. Muscle atrophy is a widely observed response to illness, decreased ADLs, and immobilization. Loss of endurance, decreased muscle mass and strength, and joint instability (see Skeletal Effects) put patients at risk for falls (see Chapter 38).

Skeletal Effects: Immobilization causes two skeletal changes: impaired calcium metabolism and joint abnormalities. Because immobilization results in bone resorption, the bone tissue is less dense or atrophied, and disuse osteoporosis results. When disuse osteoporosis occurs, the patient is at risk for pathological fractures.

Osteoporosis is a major health concern in this country. The first Surgeon General’s report on the topic of bone health stated that one in two Americans over 50 years of age will be at risk for fractures related to osteoporosis by the year 2020. Furthermore, the National Osteoporosis Foundation (2010) reports that 44 million Americans (55% of those over the age of 50) either have osteoporosis or are at risk for developing it. Approximately 80% of people who have osteoporosis are female. Although primary osteoporosis is different in origin from the osteoporosis that results from immobility, it is imperative for nurses to recognize that immobilized patients are at high risk for accelerated bone loss if they have primary osteoporosis.

Immobility can lead to joint contractures. A joint contracture is an abnormal and possibly permanent condition characterized by fixation of the joint. It is important to note that flexor muscles for joints are stronger than extensor muscles and therefore contribute to the formation of contractures. Disuse, atrophy, and shortening of the muscle fibers cause joint contractures. When a contracture occurs, the joint cannot achieve full ROM. Contractures sometimes leave a joint or joints in a nonfunctional position, as seen in patients who are permanently curled in a fetal position. Early prevention of contractures is essential; they can begin to form after only 8 hours of immobility in the older adult (Fletcher, 2005).

One common and debilitating contracture is footdrop (Fig. 47-8). When footdrop occurs, the foot is permanently fixed in plantar flexion. Ambulation is difficult with the foot in this position because the patient cannot dorsiflex the foot. The patient with footdrop is unable to lift the toes off the ground. Patients who have suffered CVAs or brain attacks with resulting right- or left-sided paralysis (hemiplegia) are at risk for footdrop.

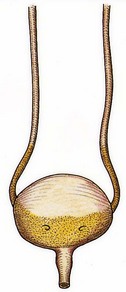

Urinary Elimination Changes: Immobility alters the patient’s urinary elimination. In the upright position urine flows out of the renal pelvis and into the ureters and bladder because of gravitational forces. When the patient is recumbent or flat, the kidneys and ureters move toward a more level plane. Urine formed by the kidney needs to enter the bladder unaided by gravity. Because the peristaltic contractions of the ureters are insufficient to overcome gravity, the renal pelvis fills before urine enters the ureters (Fig. 47-9). This condition is called urinary stasis and increases the risk of urinary tract infection and renal calculi (see Chapter 45). Renal calculi are calcium stones that lodge in the renal pelvis or pass through the ureters. Immobilized patients are at risk for calculi because they frequently have hypercalcemia.

As the period of immobility continues, fluid intake often diminishes. When combined with other problems such as fever, the risk for dehydration increases. As a result, urinary output declines on or about the fifth or sixth day after immobilization, and the urine becomes concentrated. This concentrated urine increases the risk for calculi formation and infection. Inappropriate perineal care after bowel movements, particularly in women, increases the risk of urinary tract contamination by Escherichia coli bacteria. Another cause of urinary tract infections in immobilized patients is the use of an indwelling urinary catheter.

Integumentary Changes: The changes in metabolism that accompany immobility add to the harmful effect of pressure on the skin in the immobilized patient. This makes immobility a major risk factor for pressure ulcers. Any break in the integrity of the skin is difficult to heal. Preventing a pressure ulcer is much less expensive than treating one; therefore preventive nursing interventions are imperative (WOCN, 2009).

A pressure ulcer is an impairment of the skin as a result of prolonged ischemia (decreased blood supply) in tissues (see Chapter 48). The ulcer is characterized initially by inflammation and usually forms over a bony prominence. Ischemia develops when the pressure on the skin is greater than the pressure inside the small peripheral blood vessels supplying blood to the skin.

Tissue metabolism depends on the supply of oxygen and nutrients to and the elimination of metabolic wastes from the blood. Pressure affects cellular metabolism by decreasing or totally eliminating tissue circulation. When a patient lies in bed or sits in a chair, the weight of the body is on bony prominences. The longer the pressure is applied, the longer the period of ischemia and therefore the greater the risk of skin breakdown. The older adult is especially at risk. For example, an older adult who is immobilized on a backboard following a trauma can develop skin breakdown within 3 hours (Fletcher, 2005).

Psychosocial Effects

Immobilization often leads to emotional and behavioral responses, sensory alterations, and changes in coping. When normal, healthy young men who were part of a National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) study were on bed rest for several weeks, they exhibited signs of sensory deprivation: altered sleep patterns and significant increases in anxiety, hostility, and depression (Fletcher, 2005). Every patient responds to immobility differently.

Patients with restricted mobility may have some depression. Depression is an affective disorder characterized by exaggerated feelings of sadness, melancholy, dejection, worthlessness, emptiness, and hopelessness out of proportion to reality. It results from worrying about present and future levels of health, finances, and family needs. Because immobilization removes the patient from a daily routine, he or she has more time to worry about disability. Worrying quickly increases the patient’s depression, causing withdrawal. Withdrawn patients often do not want to participate in their own care.

Developmental Changes

Developmental changes tend to be associated with immobility in the very young and older adults. The immobilized young or middle-age adult who has been healthy experiences few, if any, developmental changes. However, there are exceptions. For example, a mother with complications following birth has to go onto bed rest and as a result cannot interact with her newborn as expected.

Infants, Toddlers, and Preschoolers

The newborn infant’s spine is flexed and lacks the anteroposterior curves of the adult (see Chapter 12). As the baby grows, musculoskeletal development permits support of weight for standing and walking. Posture is awkward because the head and upper trunk are carried forward. Because body weight is not distributed evenly along a line of gravity, posture is off balance, and falls occur often. The infant, toddler, or preschooler is usually immobilized because of trauma or the need to correct a congenital skeletal abnormality. Prolonged immobilization delays the child’s gross motor skills, intellectual development, or musculoskeletal development.

Adolescents

The adolescent stage usually begins with a tremendous increase in growth (see Chapter 12). Growth is frequently uneven. Prolonged immobilization alters adolescent growth patterns. In addition, adolescents who experience immobility often are behind peers in gaining independence and accomplishing certain skills such as obtaining a driver’s license. Social isolation is a concern for this age-group when immobilization occurs.

Adults

An adult who has correct posture and body alignment feels good, looks good, and generally appears self-confident. The healthy adult also has the necessary musculoskeletal development and coordination to carry out ADLs (see Chapter 13). When periods of prolonged immobility occur, all physiological systems are at risk. In addition, the role of the adult often changes with regard to the family or social structure. Some adults lose their jobs, which affects their self-concept (see Chapter 33).

Older Adults

A progressive loss of total bone mass occurs with the older adult. Some of the possible causes of this loss include decreased physical activity, hormonal changes, and bone resorption. The effect of bone loss is weaker bones. Older adults often walk more slowly, take smaller steps, and appear less coordinated. Prescribed medications alter their sense of balance or affect their blood pressure when they change position too quickly, increasing their risk for falls and injuries (see Chapter 14). The outcomes of a fall include not only possible injury but also hospitalization, loss of independence, psychological effects, and quite possibly death (yeom et al., 2009).

Older adults often experience functional status changes secondary to hospitalization and altered mobility status (Box 47-1). Immobilization of older adults increases their physical dependence on others and accelerates functional losses. Immobilization of some older adults results from a degenerative disease, neurological trauma, or chronic illness. In others it occurs gradually and progressively, and in others—especially those who have had a stroke—immobilization is sudden. When providing nursing care for an older adult, encourage the patient to perform as many self-care activities as possible, thereby maintaining the highest level of mobility. Sometimes nurses inadvertently contribute to a patient’s immobility by providing unnecessary help with activities such as bathing and transferring.

Critical Thinking

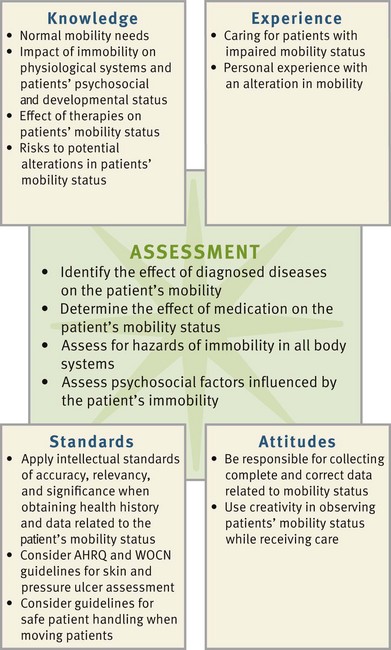

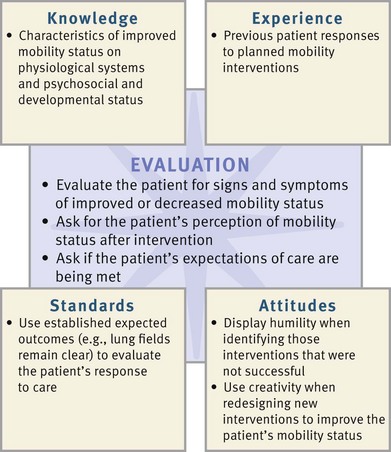

Critical thinking requires the combination of knowledge, experiences, patient data, critical thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. The needs of the immobile patient are multiple and complex. After conducting a thorough assessment, the nurse identifies appropriate nursing diagnoses and implements effective nursing care.

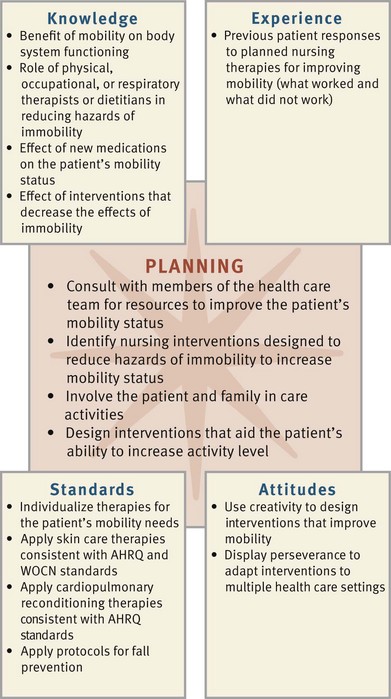

To understand the impact of immobility on the patient and family, integrate knowledge from nursing and other disciplines, previous experiences, and information gathered from patients. In addition, the use of critical thinking attitudes is necessary when designing a plan of care for successful interventions related to immobility. Professional standards such as those developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, 2009) and the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society (WOCN, 2009) and intellectual standards such as accuracy provide valuable guides for mobility management (Fig. 47-10). In addition, many agencies have standards for practice related to transferring patients and fall and pressure ulcer prevention.

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop an individualized plan of care. Patients with preexisting mobility impairments and those who are at risk for immobility will greatly benefit from your application of the nursing process and the use of your critical thinking skills to design a care plan that improves the patient’s functional status, promotes self-care, maintains psychological well-being, and reduces the hazards of immobility.

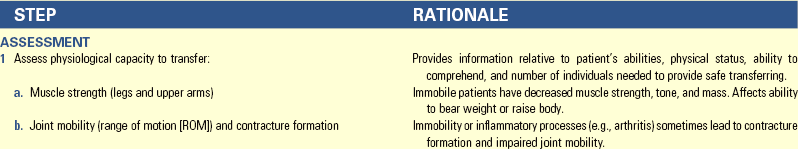

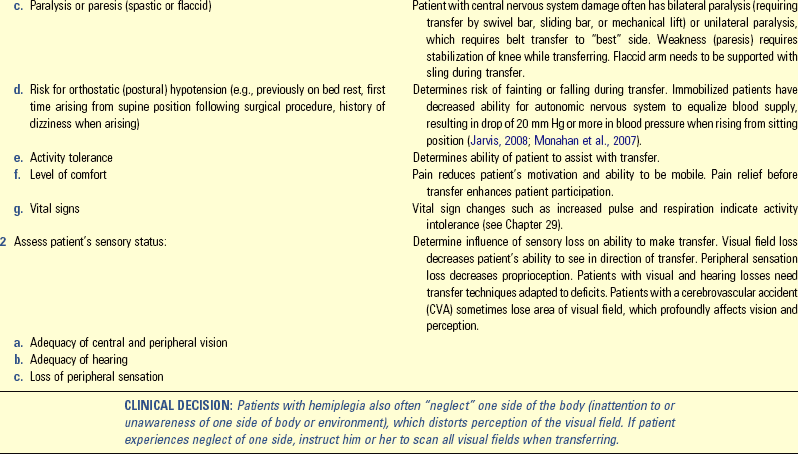

Assessment

During the assessment process, thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care. Nursing assessment of the patient includes aspects of both mobility and immobility.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

Usually the nurse assesses for and asks questions about the patient’s degree of both mobility and immobility during physical examination (Box 47-2). Keep in mind that the patient is a full partner in providing information and designing the plan of care. You convey respect for the patient’s preferences, values, and needs when implementing the nursing process and designing a plan of care with the patient (Cromwell and Berg, 2006).

Mobility

Assessment of patient mobility focuses on ROM, gait, exercise and activity tolerance, and body alignment. When unsure of the patient’s abilities, begin assessment of mobility with the patient in the most supportive position and move to higher levels according to his or her tolerance. Generally the assessment of movement starts while the patient is lying and proceeds to assessing sitting positions in bed, transfers to chair, and finally walking. This helps to protect the patient’s safety.

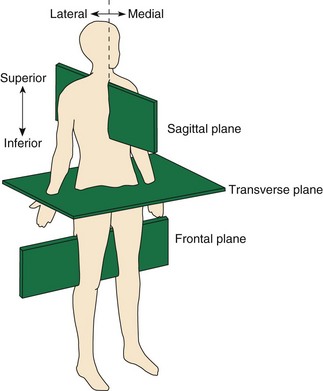

Range of Motion: Range of motion (ROM) is the maximum amount of movement available at a joint in one of the three planes of the body: sagittal, transverse, or frontal (Fig. 47-11). The sagittal plane is a line that passes through the body from front to back, dividing it into a left and right side. The frontal plane passes through the body from side to side and divides it into front and back. The transverse plane is a horizontal line that divides the body into upper and lower portions.

Ligaments, muscles, and the nature of the joint limit joint mobility in each of the planes. However, some joint movements are specific to each plane. In the sagittal plane movements are flexion and extension (e.g., fingers and elbows), dorsiflexion and plantar flexion (feet), and extension (e.g., hip). In the frontal plane movements are abduction and adduction (e.g., arms and legs) and eversion and inversion (feet). In the transverse plane movements are pronation and supination (hands) and internal and external rotation (hips).

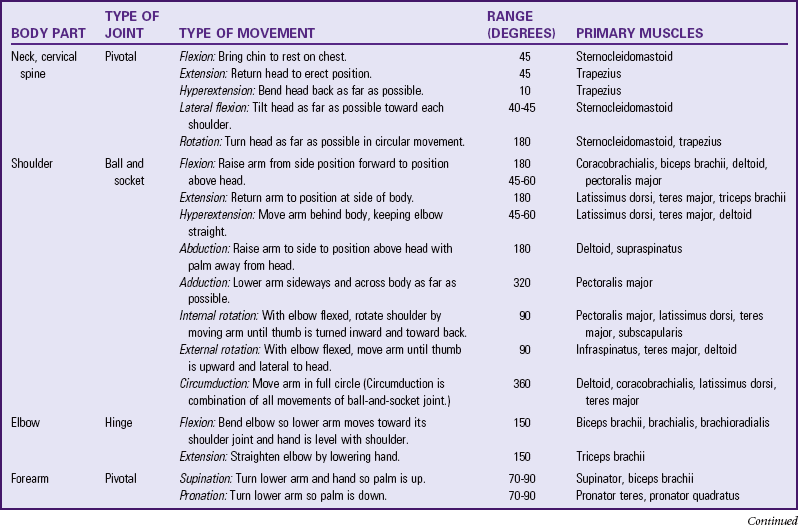

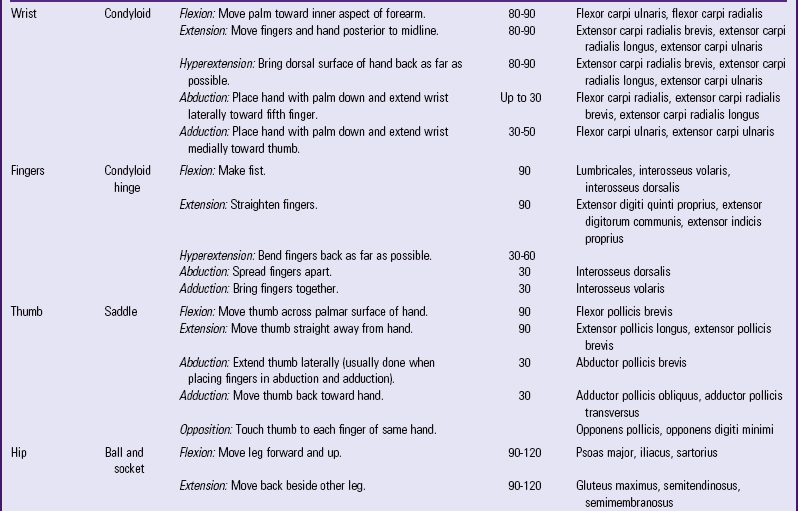

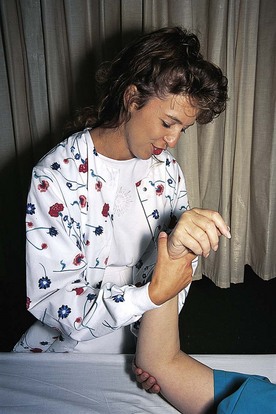

When assessing ROM, ask questions about and physically examine the patient for stiffness, swelling, pain, limited movement, and unequal movement. Chapter 30 describes specific techniques for measuring the degrees of motion in a joint. Assessment of ROM is important as a baseline measure to compare and evaluate whether loss in joint mobility has occurred. Patients whose mobility is restricted require ROM exercises to reduce the hazards of immobility. Therefore assess the type of ROM exercise that a patient is able to perform. ROM exercises are active (the patient moves all joints through their ROM unassisted), passive (the patient is unable to move independently, and the nurse moves each joint through its ROM), or somewhere in between (Table 47-2). For example, provide support for a weak patient while the patient performs most of the movement. Some patients are able to move some joints actively, whereas the nurse passively moves others. First consider the medical plan of care and if active ROM exercises are appropriate; then assess the patient’s ability to engage in active ROM exercises and the need for assistance, teaching, or reinforcement. In general, exercises need to be as active as health and mobility allow. Contractures develop in joints not moved periodically through their full ROM. Assessment data from patients with limited joint movements vary based on the area affected.

Neck: A flexion contracture of the neck is a serious disability because the patient’s neck is permanently flexed with the chin close to or actually touching the chest. Assessment reveals altered body alignment, changes in the visual field, and decreased level of independent functioning.

Shoulder: One feature of the shoulder that sets it apart from other joints in the body is that the strongest muscle controlling it, the deltoid, is in complete elongation in the normal position. No other muscle exerts its full strength when in complete elongation. Patients with limited movement in the shoulder have difficulty moving their arms.

Elbow: The elbow functions optimally at an angle of approximately 90 degrees. An elbow fixed in full extension is disabling and limits the patient’s independence.

Forearm: Most functions of the hand are best carried out with the forearm in moderate pronation. When the forearm is fixed in a position of full supination, the patient’s use of the hand is limited.

Wrist: The primary function of the wrist is to place the hand in slight dorsiflexion, the position of functioning. When the wrist is fixed in even a slightly flexed position, the grasp is weakened.

Fingers and Thumb: The ROM in the fingers and thumb enables the patient to perform ADLs and activities requiring fine-motor skills such as carpentry, needlework, drawing, and painting. The functional position of the fingers and thumb is slight flexion of the thumb in opposition to the fingers.

Hip: Because the lower extremities are concerned chiefly with locomotion and weight bearing, stability of the hip joint is more important than its mobility. For example, if one hip has no mobility but is fixed in a neutral position and fully extended, it is possible to walk without a significant limp. However, contractures often fix the hip in positions of deformity. Excessive abduction makes the affected leg appear too short, whereas excessive adduction makes it appear too long. In either case the patient has limited locomotion and walks with an obvious limp. Internal and external rotation contractures cause an abnormal and unbalanced gait.

Knee: A primary function of the knee is stability, which is achieved by ROM, ligaments, and muscles. However, the knees cannot remain stable under weight-bearing conditions unless there is adequate quadriceps power to maintain the knee in full extension. An immobile knee joint results in serious disability. The degree of disability depends on the position in which the knee is stiffened. If it is fixed in full extension, the person needs to sit with the leg out in front. When the knee is flexed, the person limps while walking. The greater the flexion, the greater is the limp.

Ankle and Foot: Without full ROM of the ankle, gait deviations occur. If the joint is not stable, the person falls. When the person relaxes as in sleep or coma, the foot relaxes and assumes a position of plantar flexion. As a result, it becomes fixed in plantar flexion (footdrop), which impairs the ability to walk.

Gait: The term gait describes a particular manner or style of walking. The gait cycle begins with the heel strike of one leg and continues to the heel strike of the other leg. Assessing a patient’s gait allows you to draw conclusions about balance, posture, safety, and ability to walk without assistance. The mechanics of human gait involve coordination of the skeletal, neurological, and muscular systems of the human body.

Exercise and Activity Tolerance: Exercise is physical activity for conditioning the body, improving health, and maintaining fitness. Nurses use it as therapy to correct a deformity or restore the overall body to a maximal state of health. When a person exercises, physiological changes occur in body systems (see Chapter 38).

Assessment of the patient’s energy level includes the physiological effects of exercise and activity tolerance. Activity tolerance is the type and amount of exercise or work that a person is able to perform. Assessment of activity tolerance is necessary when planning activity such as walking, ROM exercises, or ADLs. Activity tolerance assessment includes data from physiological, emotional, and developmental domains (see Chapter 38). This assessment is applicable in all clinical settings.

As activity begins, monitor patients for symptoms such as dyspnea, fatigue, chest pain, and/or a change in vital signs. The weak or debilitated patient is unable to sustain even slight changes in activity because of the increased demand for energy. Seemingly simple tasks such as eating and moving in bed often result in extreme fatigue. When the patient experiences decreased activity tolerance, carefully assess how much time he or she needs to recover. Decreasing recovery time indicates improving activity tolerance.

People who are depressed, worried, or anxious are frequently unable to tolerate exercise. Depressed patients tend to withdraw rather than participate. Patients who worry or are frequently anxious expend a tremendous amount of mental energy and often report feeling fatigued. Because of this, they also experience physical and emotional exhaustion.

Developmental changes also affect activity tolerance. As the infant enters the toddler stage, the activity level increases, and the need for sleep declines. The child entering preschool or primary grades expends mental energy in learning and often requires more rest after school or before strenuous play. The adolescent going through puberty requires more rest because much body energy is expended for growth and hormone changes (see Chapter 42).

Changes still occur through the adult years, but many of them are related to work and lifestyle choices. Pregnancy causes fluctuations in a woman’s energy tolerance, especially during the first and third trimesters, when she experiences increased fatigue. Hormonal changes and fetal development use body energy, and the woman is sometimes unable or unmotivated to carry out physical activities. During the last trimester fetal development consumes a great deal of the mother’s energy; and the size and location of the fetus limit the ability to take a deep breath, resulting in less oxygen being available for physical activities.

As the person grows older, activity tolerance changes. Muscle mass is reduced, and posture and bone composition change. Changes in the cardiorespiratory system such as decreased maximum heart rate and lung compliance, which affect the intensity of exercise, often occur. As age progresses, some older individuals still exercise but do so at a reduced intensity. The more inactive a patient is, the more pronounced are these activity changes.

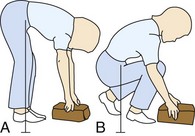

Body Alignment: Perform assessment of body alignment with the patient standing, sitting, or lying down. This assessment has the following objectives:

• Determining normal physiological changes in body alignment resulting from growth and development for each patient

• Identifying deviations in body alignment caused by incorrect posture

• Providing opportunities for patients to observe their posture

• Identifying learning needs of patients for maintaining correct body alignment

• Identifying trauma, muscle damage, or nerve dysfunction

• Obtaining information concerning other factors that contribute to incorrect alignment such as fatigue, malnutrition, and psychological problems

The first step in assessing body alignment is to put patients at ease so they do not assume unnatural or rigid positions. When assessing the body alignment of an immobilized or unconscious patient, remove pillows and positioning supports from the bed and place the patient in the supine position.

Standing: Characteristics of correct body alignment for the standing patient include the following:

1. The head is erect and midline.

2. When observed posteriorly, the shoulders and hips are straight and parallel.

3. When observed posteriorly, the vertebral column is straight.

4. When observed laterally, the head is erect, and the spinal curves are aligned in a reversed S pattern. The cervical vertebrae are anteriorly convex, the thoracic vertebrae are posteriorly convex, and the lumbar vertebrae are anteriorly convex.

5. When observed laterally, the abdomen is comfortably tucked in, and the knees and ankles are slightly flexed. The person appears comfortable and does not seem conscious of the flexion of knees or ankles.

6. The arms hang comfortably at the sides.

7. The feet are slightly apart to achieve a base of support, and the toes are pointed forward.

8. When viewing the patient from behind, the center of gravity is in the midline, and the line of gravity is from the middle of the forehead to a midpoint between the feet. Laterally the line of gravity runs vertically from the middle of the skull to the posterior third of the foot (Fig. 47-12).

Sitting: Characteristics of correct alignment of the sitting patient include the following:

1. The head is erect, and the neck and vertebral column are in straight alignment.

2. The body weight is distributed evenly on the buttocks and thighs.

3. The thighs are parallel and in a horizontal plane.

4. Both feet are supported on the floor (Fig. 47-13), and the ankles are flexed comfortably. With patients of short stature, use a footstool to ensure that ankles are flexed comfortably.

5. A 2.5- to 5-cm (1- to 2-inch) space is maintained between the edge of the seat and the popliteal space on the posterior surface of the knee. This space ensures that there is no pressure on the popliteal artery or nerve to decrease circulation or impair nerve function.

6. The patient’s forearms are supported on the armrest, in the lap, or on a table in front of the chair.

It is particularly important to assess alignment when sitting if the patient has muscle weakness, muscle paralysis, or nerve damage. Patients who have these problems have diminished sensation in the affected area and are unable to perceive pressure or decreased circulation. Proper alignment while sitting reduces the risk of musculoskeletal system damage in such a patient. The patient with severe respiratory disease sometimes assumes a posture of leaning on the table in front of the chair in an attempt to breathe more easily. This is called orthopnea.

Lying: People who are conscious have voluntary muscle control and normal perception of pressure. As a result, they usually assume a position of comfort when lying down. Because their ROM, sensation, and circulation are within normal limits, they change positions when they perceive muscle strain and decreased circulation.

Assess body alignment for a patient who is immobilized or bedridden with the patient in the lateral position. Remove all positioning supports from the bed except for the pillow under the head and support the body with an adequate mattress (Fig. 47-14). This position allows for full view of the spine and back and helps provide other baseline body alignment data such as whether the patient is able to remain positioned without aid. The vertebrae are aligned, and the position does not cause discomfort. Patients with impaired mobility (e.g., traction or arthritis), decreased sensation (e.g., hemiparesis following a CVA), impaired circulation (e.g., diabetes), and lack of voluntary muscle control (e.g., spinal cord injury) are at risk for damage when lying down.

Immobility

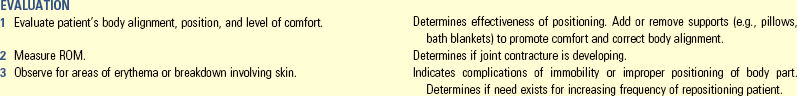

Assess the patient for hazards of immobility by performing a head-to-toe physical assessment (see Chapter 30). In addition, focus on certain physiological areas and the patient’s psychosocial and developmental dimensions. Table 47-3 summarizes how to assess for the physiological hazards of immobility.

TABLE 47-3

Assessment of the Physiological Hazards of Immobility

Metabolic System: When assessing metabolic functioning, use anthropometric measurements (measures of height, weight, and skinfold thickness) to evaluate muscle atrophy (see Chapter 30). In addition, analyze intake and output records for fluid balance. Does intake equal output? Intake and output measurements help the nurse determine whether a fluid imbalance exists (see Chapter 41). Dehydration and edema increase the rate of skin breakdown in a patient who is immobilized. Monitoring laboratory data such as levels of electrolytes, serum protein (albumin and total protein), and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) aid the nurse in determining metabolic functioning.

Monitoring food intake and elimination patterns and assessing wound healing help to determine altered gastrointestinal functioning and potential metabolic problems. If the patient has a wound, the rate of healing indicates how well nutrients are delivered to tissues. Normal progression of healing indicates that metabolic needs of injured tissues are being met. Anorexia commonly occurs in patients who are immobilized. Assess the patient’s food intake before the meal tray is removed to determine the amount eaten. Assess his or her dietary patterns and food preferences at the onset of immobilization to help prevent nutritional imbalances (see Chapter 44).

Respiratory System: Perform a respiratory assessment at least every 2 hours for patients with restricted activity. Inspect chest wall movements during the full inspiratory-expiratory cycle. If a patient has an atelectatic area, chest movement is often asymmetrical. Auscultate the entire lung region to identify diminished breath sounds, crackles, or wheezes. Focus auscultation on the dependent lung fields because pulmonary secretions tend to collect in these lower regions.

Cardiovascular System: Cardiovascular nursing assessment of the patient who is immobilized includes blood pressure monitoring, evaluation of apical and peripheral pulses, and observation for signs of venous stasis (e.g., edema and delayed wound healing).

Although not all patients experience orthostatic hypotension, nurses monitor their vital signs during the first few attempts at sitting or standing (see Chapter 29). Move the patient gradually during position changes and monitor him or her closely for dizziness while assessing orthostatic blood pressures. The longer the period of immobility, the greater is the risk of hypotension when the patient stands (Huether and McCance, 2008).

Also assess apical and peripheral pulses (see Chapter 30). Recumbent positions increase cardiac workload and result in an increased pulse rate. In some patients, particularly older adults, the heart does not tolerate the increased workload, and a form of cardiac failure develops. A third heart sound, heard at the apex, is an early indication of congestive heart failure. Monitoring peripheral pulses allows the nurse to evaluate the ability of the heart to pump blood. Immediately document and report the absence of a peripheral pulse in the lower extremities to the patient’s health care provider, especially if the pulse was present previously.

Edema sometimes develops in patients who have had injury or whose heart is unable to handle the increased workload of bed rest. Because edema moves to dependent body regions, assessment of the patient experiencing immobility includes the sacrum, legs, and feet. If the heart is unable to tolerate the increased workload, peripheral body regions such as the hands, feet, nose, and earlobes are colder than central body regions. To assess for a deep vein thrombosis (DVT), remove the patient’s elastic stockings and/or sequential compression devices (SCDs) every 8 hours (or according to agency policy) and observe the calves for redness, warmth, and tenderness. Homans’ sign, or calf pain on dorsiflexion of the foot, is contraindicated in patients when a DVT is suspected. It is no longer a reliable indicator in assessing for DVT, and it is present in other conditions (see Chapter 30).

Measure bilateral calf circumference and record it daily as an alternative assessment for DVT. To do this, mark a point on each calf 10 cm (3.9 inches) down from the midpatella. Measure the circumference each day using the mark for placement of the tape measure. Unilateral increases in calf circumference are an early indication of thrombosis. Because DVTs also occur in the thigh, take thigh measurements daily if the patient is prone to thrombosis. A dislodged venous thrombus, called an embolus, can travel through the circulatory system to the lungs and impair circulation and oxygenation, resulting in tachycardia and shortness of breath. Venous emboli that travel to the lungs are sometimes life threatening. More than 90% of all pulmonary emboli begin in the deep veins of the lower extremities (Huether and McCance, 2008).

Musculoskeletal System: Major musculoskeletal abnormalities to identify during nursing assessment include decreased muscle tone and strength, loss of muscle mass, and contractures. The anthropometric measurements described previously indicate losses in muscle tone and muscle mass.

Early assessment of ROM is important because it establishes a baseline against which later measurements can be compared to evaluate whether a loss in joint mobility has occurred. Measure ROM with a goniometer (see Fig. 38-9). Physical assessment cannot identify disuse osteoporosis. However, patients on prolonged bed rest, postmenopausal women, patients taking steroids, and people with increased serum and urine calcium levels have a greater risk for bone demineralization. Consider the risk of disuse osteoporosis when planning nursing interventions. Although some falls result in injury, others occur because of pathological fractures secondary to osteoporosis.

Integumentary System: Continually assess the patient’s skin for breakdown and color changes such as pallor or redness. Consistently use a standardized tool such as the Braden Scale. This identifies patients with a high risk for impaired skin integrity or early changes in the condition of patients’ skin. Early identification allows for early intervention. Observe the skin often during routine care (e.g., when the patient is turned, during hygiene measures, and when providing for elimination needs). At a minimum, skin assessment occurs every 2 hours (see Chapter 48).

Elimination System: Evaluate the patient’s elimination status on each shift and total intake and output every 24 hours. Compare the amounts over time. Determine that the patient is receiving the correct amount and type of fluids orally or parenterally (see Chapters 41 and 45). Inadequate intake and output or fluid and electrolyte imbalances increase the risk for renal system impairment, ranging from recurrent infections to kidney failure. Dehydration also increases the risk for skin breakdown, thrombus formation, respiratory infections, and constipation.

Assessment of elimination status includes the adequacy of dietary choices, bowel sounds, and the frequency and consistency of bowel movements (see Chapter 46). Accurate assessment enables the nurse to intervene before constipation and fecal impaction occur.

Psychosocial Assessment: Many alterations in physiological, sociocultural, and developmental functioning are related to immobility. Often these problems are interrelated, and it is imperative that nursing care focuses on all dimensions. Often the focus of immobility is on the easily visible physical problems such as skin impairment, but do not overlook its psychosocial and developmental aspects.

Abrupt changes in personality often have a physiological cause such as surgery, a medication reaction, a pulmonary embolus, or an acute infection. For example, the primary symptom of compromised older patients with an acute urinary tract infection or fever is confusion. Identifying confusion is an important component of the nurse’s assessment. Acute confusion in older adults is not normal; a thorough nursing assessment is the priority (Ebersole et al., 2008).

Common reactions to immobilization include boredom and feelings of isolation, depression, and anger. Observe for changes in a patient’s emotional status and listen carefully to family if they report emotional changes. Examples of change that indicate psychosocial concerns are a cooperative patient who becomes less cooperative or an independent patient who asks for more help than is necessary. The nurse investigates reasons for such alterations. Identifying how the patient usually copes with loss is vital (see Chapters 35 and 36). A change in mobility status, whether permanent or not, causes a grief reaction. Families are a key resource for information about behavior changes.

Identify and correct unexplained changes in the sleep-wake cycle. Nurses prevent or minimize most stimuli that interrupt the sleep-wake cycle (e.g., nursing activities, a noisy environment, or discomfort). However, some medications such as analgesics, sleeping pills, or cardiovascular drugs also cause sleep disturbances (see Chapter 42).

Because psychosocial changes usually occur gradually, observe the patient’s behavior on a daily basis. If behavioral changes occur, determine the cause(s) and evaluate the changes. Identifying the cause helps you to design appropriate nursing interventions.

Developmental Assessment: Include a developmental assessment of patients who are immobilized. When caring for a young child, determine whether he or she is able to meet developmental tasks and is progressing normally. The child’s development sometimes regresses or slows because he or she is immobilized. Design nursing interventions that maintain normal development, provide physical and psychosocial stimuli after identifying a child’s developmental needs, and assure the parents that developmental delays are usually temporary.

Immobilization of a family member changes family functioning. The family’s response to this change often leads to problems, stress, and anxieties. Children, when seeing parents who are immobile, sometimes have difficulty understanding what is occurring and difficulty coping.

Immobility has a significant effect on the older adult’s levels of health, independence, and functional status. Nursing assessment enables the nurse to determine the patient’s ability to meet needs independently and adapt developmental changes such as declining physical functioning and altered family and peer relationships. A decline in developmental functioning needs prompt investigation to determine why the change occurred and interventions that can return the patient to an optimal level of functioning as soon as possible. Activities that reduce immobility and promote participation in ADLs are vital to preventing functional decline (Kawamoto et al., 2006). Assessment also includes the patient’s home and community to identify factors that are risks to his or her mobility and safety (see Chapter 38).

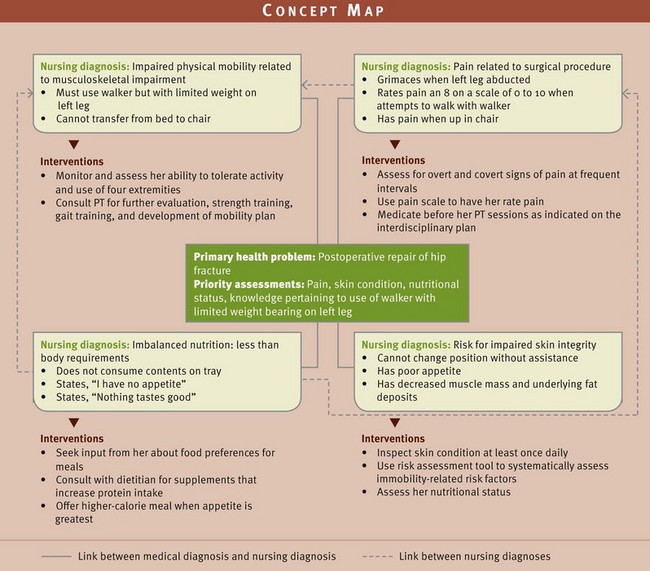

Nursing Diagnosis: A patient who is experiencing an alteration in mobility often has one or more nursing diagnoses. The two diagnoses most directly related to mobility problems are impaired physical mobility and risk for disuse syndrome. The diagnosis of impaired physical mobility applies to the patient who has some limitation but is not completely immobile. The diagnosis of risk for disuse syndrome applies to the patient who is immobile and at risk for multisystem problems because of inactivity. Beyond these diagnoses, the list of potential diagnoses is extensive, because immobility affects multiple body systems. Other possible nursing diagnoses include the following:

Assessment reveals clusters of data that indicate whether a patient is at risk or if an actual problem exists. The clusters of data include defining characteristics that support the diagnostic label and probable cause of the diagnosis. Locating the probable cause of the diagnosis (based on assessment data) is important to planning patient-centered goals and subsequent nursing interventions that will best help the patient.

Impaired physical mobility related to reluctance to initiate movement requires slightly different interventions than impaired physical mobility related to pain in the left shoulder. Thus it is critical that nursing assessment activities identify and cluster defining characteristics that ultimately support the nursing diagnosis selected (Box 47-3). The diagnosis related to reluctance to initiate movement requires interventions aimed at keeping the patient as mobile as possible and encouraging him or her to perform self-care and ROM. The diagnosis related to pain requires the nurse to assist the patient with comfort measures so he or she is then willing and more able to move. In both situations the nurse explains how activity enhances healthy body functioning.

Often the physiological dimension is the major focus of nursing care for patients with impaired mobility. Thus the psychosocial and developmental dimensions are neglected. Yet all dimensions are important to health. During immobilization some patients experience decreased social interaction and stimuli. These patients frequently use the nurse’s call bell to request minor physical attention when their real need is greater socialization. Nursing diagnoses for health needs in developmental areas reflect changes from the patient’s normal activities. Immobility leads to a developmental crisis if the patient is unable to resolve problems and continue to mature.

Immobility also leads to multiple complications (e.g., renal calculi, DVT, pulmonary emboli, or pneumonia). If these conditions develop, collaborate with the health care provider or nurse practitioner for prescribed therapy to intervene. Be alert for and prevent these potential complications when possible.

Planning: During planning the nurse synthesizes information from resources such as knowledge of the role of respiratory and physical therapy, standards such as skin care guidelines from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society (WOCN), protocols for patients at risk for falls, attitudes such as creativity and perseverance, and past experiences with immobilized patients (Fig. 47-15). Critical thinking ensures that the patient’s plan of care integrates all that you know about the individual and key critical thinking elements. Professional standards are especially important to consider when you develop a plan of care. These standards often establish scientifically proven guidelines for selecting effective nursing interventions. Finally, as stated earlier, the patient is a full partner in designing the plan of care, and this input must be reflected when establishing the goals and outcomes.

Goals and Outcomes

Develop an individualized plan of care for each nursing diagnosis (see the Nursing Care Plan). Set realistic expectations for care and include the patient and family when possible. Set goals that are individualized, realistic, and measurable. The goals focus on preventing problems or risks to body alignment and mobility.

Develop goals and expected outcomes to assist the patient in achieving his or her highest level of mobility and reducing the hazards of immobility. For example, a patient who has left-sided paralysis following a stroke has two long-term goals. The first, directed toward improved mobility, is “Patient uses walker to ambulate safely in the home.” A parallel goal directed toward the hazards of immobility is “Patient’s skin remains intact.” Both of these goals are essential to restoring maximal mobility for this patient. Because there is impaired sensation, both the patient and caregivers need to be aware of the patient’s need to have the skin free of pressure. Expected outcomes for the second goal include the following:

Setting Priorities

The effect that problems have on the patient’s mental and physical health determines the immediacy of any problem. Set priorities when planning care to ensure that immediate needs are met first. This is particularly important when patients have multiple diagnoses (Fig. 47-16). Plan therapies according to severity of risks to the patient; and individualize the plan according to the patient’s developmental stage, level of health, and lifestyle.

It is especially important in priority setting to make sure that you do not overlook potential complications. Many times actual problems such as pressure ulcers and disuse syndrome are addressed only after they develop. Therefore monitor the patient often, reinforcing prevention techniques to both the patient and other caregivers and supervising nursing assistive personnel in carrying out activities aimed at preventing complications of impaired mobility.

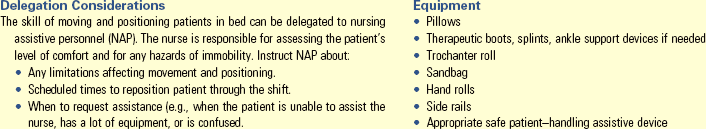

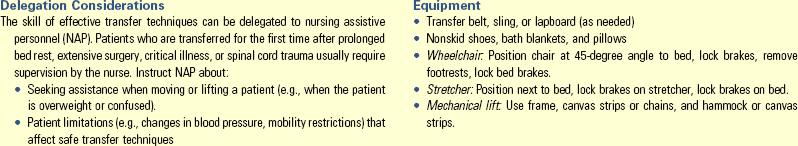

Teamwork and Collaboration

Care of the patient experiencing alterations in mobility requires a team approach. Nurses often delegate some interventions to nursing assistive personnel. Nursing assistive personnel can encourage the patient to do leg exercises, use the incentive spirometer, and cough and deep breathe (see Chapter 40). They can turn and position patients and apply elastic stockings. They can also help the nurse measure leg circumferences and height and weight.

Collaborate with other health care team members such as physical or occupational therapists when it is essential to consider mobility needs. Understanding the need for and having open communications with other members of the interdisciplinary care team results in better patient outcomes and hopefully prevents the hazards of immobility. It is through these collaborative efforts and teamwork that patients benefit most. For example, physical therapists are a resource for planning ROM or strengthening exercises, and occupational therapists are a resource for planning ADLs that patients need to modify or relearn. Wound care specialists and respiratory therapists are often involved in patient care, especially with patients who are experiencing complications related to their immobility. Consult a registered dietitian when the patient is experiencing nutritional problems; and refer him or her to a mental health advanced practice nurse, licensed social worker, or psychologist to assist with coping or other psychosocial issues.

Discharge planning begins when a patient enters the health care system. In anticipation of the patient’s discharge from an institution, make appropriate referrals or consult a case manager or a discharge planner to ensure that the patient’s needs are met at home. Consider the patient’s home environment when planning therapies to maintain or improve body alignment and mobility. Referrals to home care or outpatient therapy are often needed.

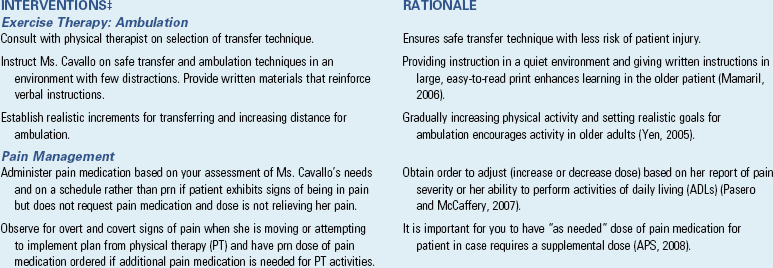

Implementation

Health promotion activities include a variety of interventions such as education, prevention, and early detection. Examples of health promotion activities that address mobility and immobility include prevention of work-related injury, fall-prevention measures, exercise, and early detection of scoliosis.

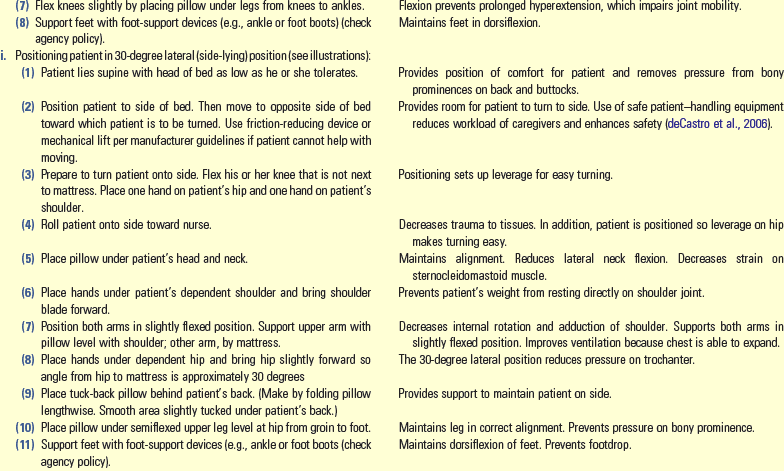

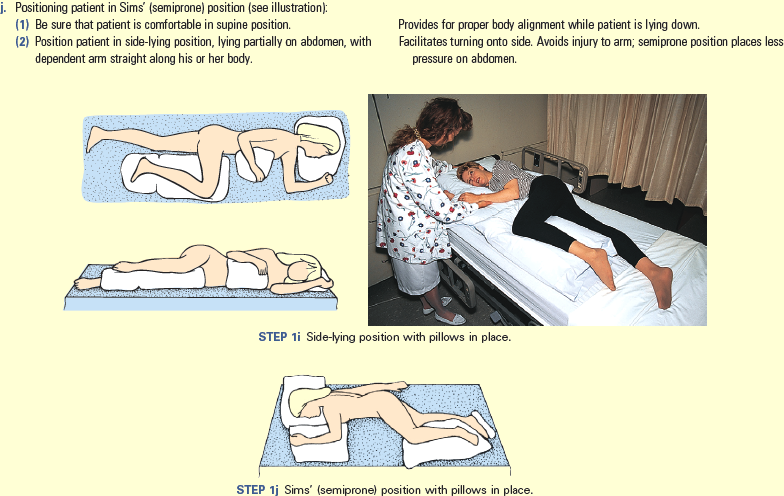

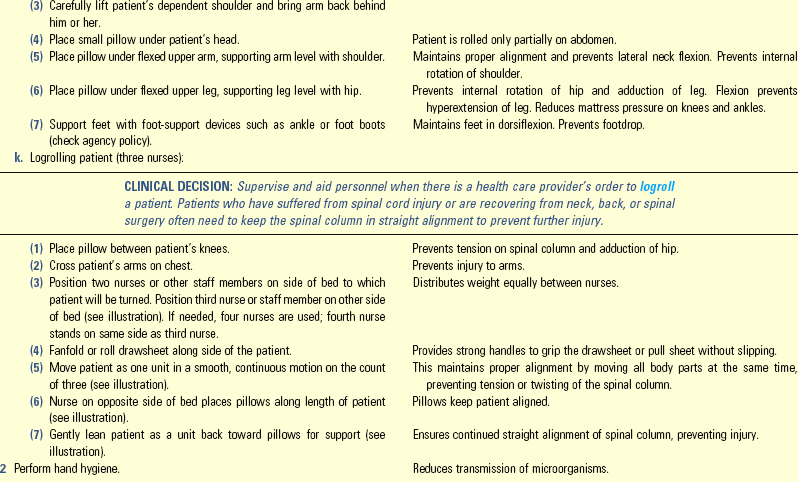

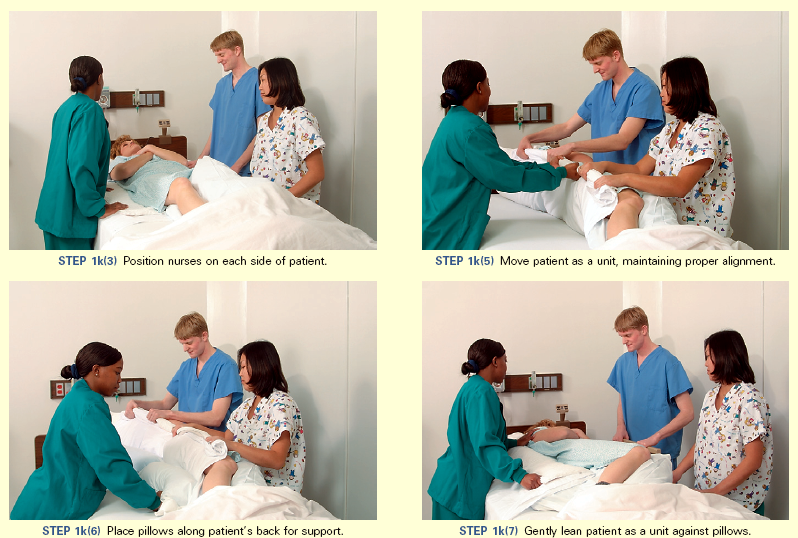

Prevention of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Injuries: The rate of work-related injuries in health care settings has increased in recent years. In 2006 there were 4.4 cases per 100 full-time workers who experienced occupational injury and illness compared with 5 cases per 100 for private industry overall. The rate for nursing homes was 10.1 per 100 workers (USDL, 2007). Most these injuries occurred as a result of overexertion, which resulted in back injuries and other musculoskeletal problems. Back injuries are often the direct result of improper lifting and bending. The most common back injury is strain on the lumbar muscle group, which includes the muscles around the lumbar vertebrae. Injury to these areas affects the ability to bend forward, backward, and from side to side and limits the ability to rotate the hips and lower back. Research has demonstrated that ergonomic programs in health care facilities reduce costs, injuries to employees, and missed work days. Matz (2007) noted that patient quality of care is best when staff are healthy and they are not experiencing any pain or discomfort.