Food and Nutrient Delivery

Bioactive Substances and Integrative Care

Integrative Medicine

Integrative medicine focuses on healing-oriented medicine that considers the whole person (body, mind, spirit) and all aspects of lifestyle. Emphasis is placed on the therapeutic relationship and appropriate therapies, both conventional and alternative. A multidisciplinary approach that moves beyond conventional medicine practitioners is needed; here, patients and health care providers are partners in promoting wellness. The scope of care includes wellness and prevention, and, when illness does occur, a reliance on less invasive approaches is emphasized. Yet integrative care is evidence-based by critically evaluating all medical and healing approaches.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) refers to those practices that are not a customary part of conventional medicine. This includes such treatment methodologies as acupuncture, meditation, naturopathy, and chiropractic care. Integrative medicine is slightly different than CAM in that it is focused on the combined use of conventional and CAM approaches, and is defined as the comprehensive integration of appropriate complementary approaches along with conventional medical approaches into the care of the whole person, with the goal of achieving optimal health outcomes (Kiefer, 2009).

CAM and integrative therapies are not new. In fact, their roots can be traced to early Greek and Chinese cultures. Although natural therapies are often described as being “cutting edge,” they are actually much older than conventional Western medical interventions. Experts estimate that herbal remedies and ayurveda, the traditional medicine of India, are more than 5000 years old. CAM therapies are holistic therapies, derived from the Greek word holos, meaning whole. They are based on the theory that health is a vital dynamic state, reflecting a profound will and wisdom to maintain wellness rather than just the absence of disease. Vis mediatrix naturae, the healing force of nature, is the underlying precept of holistic medicine. According to this precept, all living things can self-heal, and organisms have inherent self-defense mechanisms against illness. According to the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) classification scheme, CAM can be grouped as (1) alternative medical systems such as naturopathy, traditional Chinese Medicine, ayurveda, and homeopathy; (2) mind-body therapies such as meditation, prayer, art or music therapy, and cognitive behavior therapy; (3) biologically based therapies such as the use of herbs, whole-foods diets, and nutrient supplementation; (4) manipulative therapies such as massage, chiropractic medicine, osteopathy, and yoga; and (5) and medical systems based on energy therapies such as qi gong, magnetic therapy, or reiki.

Functional medicine has some components of CAM therapy, but shifts the disease-centered focus of traditional medical practice to a more patient-centered approach (Institute of Functional Medicine, 2011). The goal is to evaluate the whole person rather than individual symptoms, and to consider care in relation to prevention as well as long-term support for health. Diet, nutrition, and exercise are considered central to “best medical practice” in the delivery of functional medicine. The philosophy also embraces biochemical individuality, hormonal and neurotransmitter imbalance, oxidative stress and detoxification, immune enhancement, and the overall dynamic balance of internal and external factors important to health and longevity.

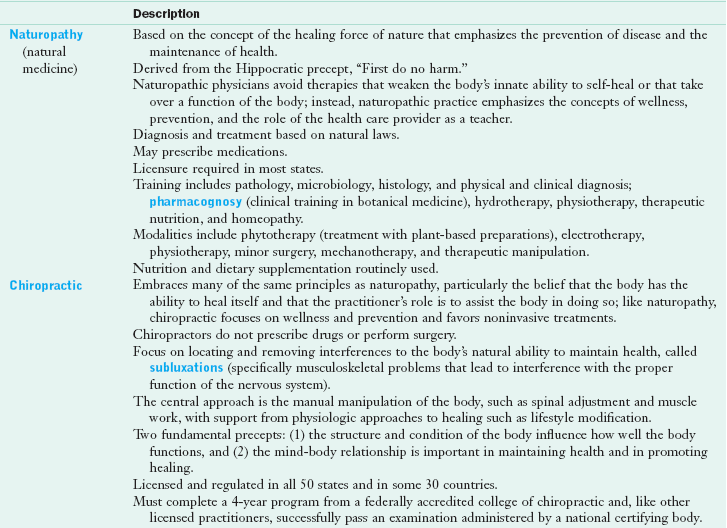

Increasingly, health care practitioners, including dietetics professionals, are involved in the provision of care based on an integrative approach. For example, functional nutrition assessment (as defined in New Directions: Functional Nutrition Assessment in Chapter 6) is being included more frequently as part of a complete health evaluation. As the cost of health care escalates, providers are actively seeking integrative care as a plausible approach to reducing costs and enhancing client satisfaction (Maizes, 2009; Ullman, 2009). Diet therapy and dietary supplementation are modalities commonly practiced in the context of CAM and integrative and functional medicine. Several diet-based therapies are listed as CAM modalities, including the Ornish, Zone, Atkins, and Pritikin diets, as well as macrobiotic and vegetarian diets. See Table 13-1 for descriptions of modalities identified as within the scope of CAM.

Use of Complementary and Alternative Therapies

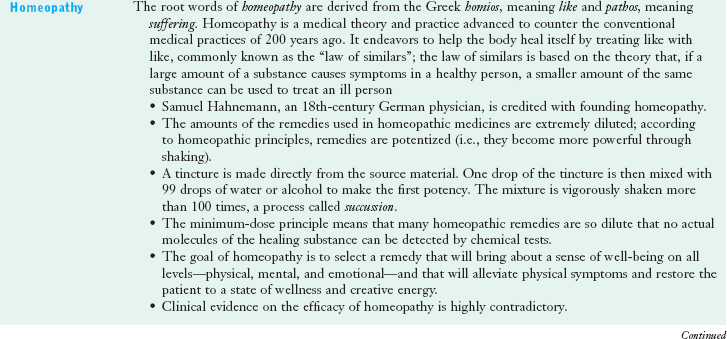

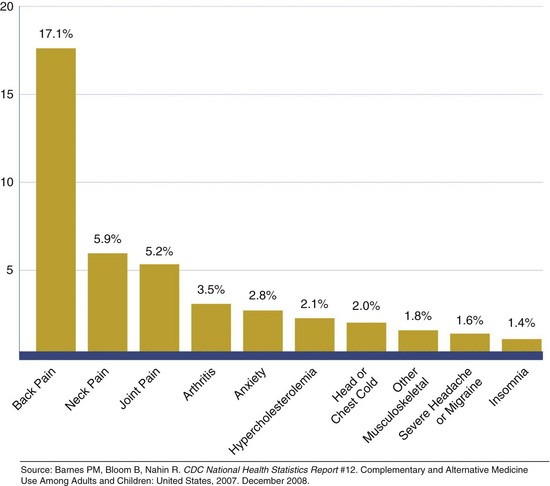

The use of CAM therapies to enhance conventional medical practices has increased in the United States since the 1960s. A significant number of Americans use some form of CAM therapy even more frequently than they see a primary care physician. Figure 13-1 shows the frequency of use of CAM therapies.

FIGURE 13-1 The ten most common complementary and alternative medicine therapies used by adults. (Source: http://nccam.nih.gov/news/camstats/2007/graphics.htm. Accessed 24 May 2010.)

Data from the Alternative Health/Complementary and Alternative Medicine supplement to the 2007 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, showed that among the 29,266 American households and 75,764 people surveyed, 38.3% of adults and one in nine children reported use of CAM within the previous 12 months (Barnes et al., 2008). Use has been shown to be greatest among women, people ages 30-69, people with higher education, those residing in the western United States, and people who were hospitalized in the previous 12 months (National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2005). By race or ethnicity, Native Americans (50.3%) and Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (43.2%) report the highest use of CAM, followed by non-Hispanic whites (43.1%). Factors associated with greater CAM use among children include adolescence, college-educated parents, concurrent prescription medication use, and reported anxiety or stress, as well as dermatologic conditions, sinusitis, and musculoskeletal conditions (Birdee, 2010).

Between 2002 and 2007, use of CAM therapies acupuncture, deep breathing, massage therapy, meditation, naturopathy, and yoga increased. Vegetarian diets were most commonly used (3.5% of adults), followed by the Atkins Diet (1.7%), macrobiotic (0.2%), and Zone diets (0.2%). Megavitamin therapy was reportedly used by 2.8% of the adult population surveyed (Barnes et al., 2008).

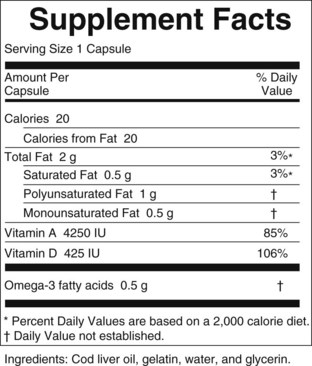

Those who use these therapies believe that these options are beneficial to their overall health and are more congruent with their values about health than conventional therapies. Frequently, there is an increased reliance on CAM therapies when conventional medicine has little to offer in terms of effective treatment, or when the current conventional approach has significant risks and side effects that motivate patients to explore alternatives. CAM therapies are also often considered when conventional therapies or diagnostic workups are not deemed effective by the patient (as in insomnia, pain, anxiety), when CAM approaches have been shown to be effective (chiropractic medicine for back pain, acupuncture for pain relief, select dietary supplementation for joint pain associated with osteoarthritis), and when CAM approaches are supported by significant historical evidence of efficacy. The recent NHIS survey also suggested that CAM use increases when conventional treatments are too costly. Figure 13-2 shows the frequency of CAM use by medical diagnosis.

FIGURE 13-2 Diseases for which complementary and alternative medicine therapies are most often used by adults. (Source: http://nccam.nih.gov/news/camstats/2007/graphics.htm. Accessed 24 May 2010.)

As a result of the increased interest in these therapies, the Office of Alternative Medicine of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) was created in 1992 to evaluate their effectiveness. This office became the 27th institute or center within the NIH in 1998. Renamed NCCAM, the Center explores complementary and alternative healing practices scientifically, using research, training, outreach, and integration. (Ahn et al, 2010) In addition to research funding, there has been an increased awareness of expanding training needs as well as medical reimbursement for provision of CAM therapies in the context of conventional medical systems. Increasingly, nursing and medical curricula include CAM training.

Dietary Supplementation

Dietary supplementation is common practice among Americans, particularly among those at risk or diagnosed with clinical conditions such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hypertension. Consumers and health professionals should be aware that there is limited information on the effects of dietary supplements taken concurrently with prescription and other over-the-counter medications (Farmer Miller et al., 2008).

Historically, dietetics professionals focused their assessment, care plan, and counseling on diet or food-related recommendations. The 2007 NHIS survey of CAM use indicated that nonvitamin, nonmineral, natural products are the most common form of CAM. The demand for information in this area from dietetics professionals remains high. In fact, the 2009 Position Paper of the American Dietetic Association on nutrient supplementation calls on registered dietitians to be the “first source” of information on nutrient supplementation (Marra et al., 2009).

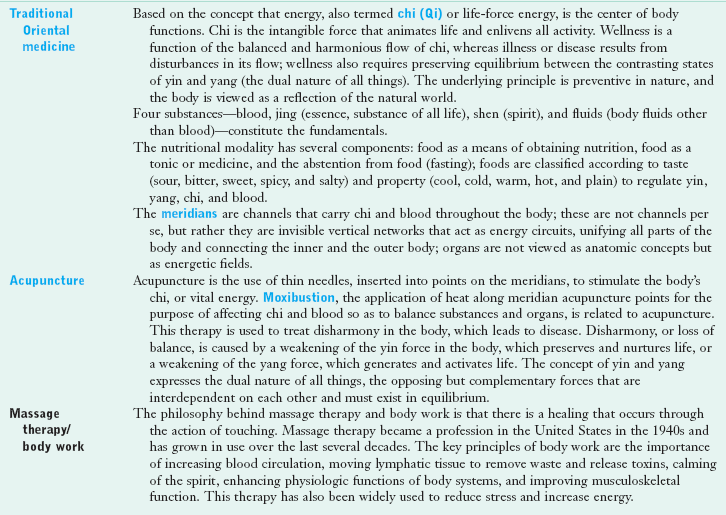

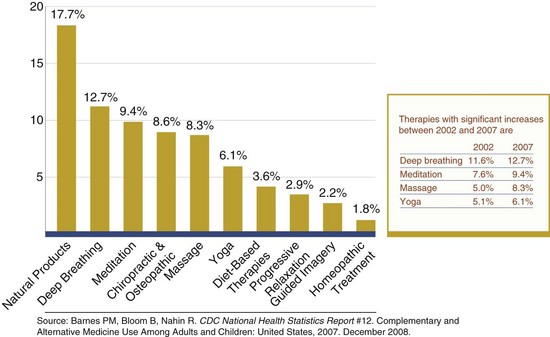

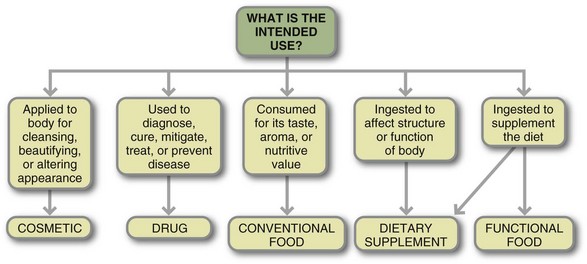

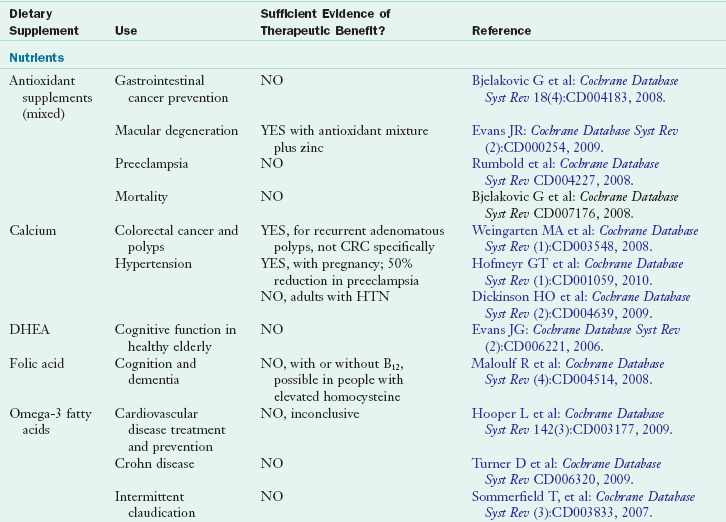

Dietary supplements have been officially defined under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994 as products intended to supplement the diet that contain one or more of the following ingredients: a vitamin, mineral, herb or other botanical, amino acid, concentrate, metabolite, constituent, extract, or combinations of these ingredients. Dietary supplements are intended for ingestion in pill, capsule, tablet, or liquid form and are not to be represented for use as a conventional food or as the sole item of a meal or diet. They should be labeled as a dietary supplement and carry the dietary supplement facts label (Figure 13-3). Dietary supplements must be differentiated from drugs, cosmetics, and foods; see Figure 13-4.

FIGURE 13-3 A dietary supplement facts label per Food and Drug Administration regulation as defined under the Dietary Supplement Health Education Act. (Source: http://www.fda.gov/Food/DietarySupplements/ConsumerInformation/ucm110493.htm. Accessed 24 May 2010.)

FIGURE 13-4 Use of dietary supplementation in clinical practice requires use of a credible resource for evaluation and application. (From Thomson CA, Newton T: Dietary supplements: evaluation and application in clinical practice, Topics Clin Nutr 20(1):32, 2005. Reprinted with permission.)

Botanicals, plants (including their leaves, flowers, stems, rhizomes, or roots) that are used for medicinal purposes, are formulated in a wide variety of forms, including teas, infusions, and decoctions (concentrated beverage made from boiling plant root), as well as extracts (including tinctures, alcohol solvent, and glycerite-glycerol solvent) and pill forms (capsules, tablets, lozenges, soft gels) (see Botanical Formulations in Box 13-1). Topical application of botanicals or nutrients in the form of creams or essential oils such as are used in aromatherapy are not classified as dietary supplements under the current regulatory definition. Created in Germany, the Commission E Monographs on phytomedicines were developed by an expert commission of scientists and health care professionals as references for practice of phytotherapy, the science of using plant-based medicines to prevent or treat illness.

In recent years the Office of Dietary Supplements has worked collaboratively with several organizations and experts to develop a database of dietary supplements used in the United States. Because the database provides specific information on the nutrient, herbal, or other constituents contained in a supplement, it allows clinicians to more accurately assess the appropriate use of select supplements by their patients. The database includes dietary supplement label information for more than 4000 supplements, including the structure and function claims. The information is linked to PubMed, allowing clinicians access to peer-reviewed information on use in human trials, adverse events (AEs) associated with use, and information regarding the mechanism of action (National Institutes of Health, 2010).

Trends in Dietary Supplement Use

Dietary supplement use is common among adults in the United States and is growing among children as well. About one third of adults use a multivitamin and mineral supplement regularly (American Dietetic Association, 2009). The NHIS CAM survey showed the most common nonvitamin, nonmineral supplements consumed were fish oils, glucosamine, echinacea, flaxseed, and ginseng (Barnes et al., 2008). Children commonly consume the same dietary supplements taken by adults. Use of dietary supplements has been shown to increase with advancing age, white race, and female gender. Reports find that use of dietary supplements is highest among those in the best state of health; most frequently supplements are taken by those with a body mass index less than 25 kg/m2 who are nonsmokers, are physically active, report good health, adhere to a healthy diet, and use food labels in making food choices, as well as among those with high incomes and education (Archer, 2005).

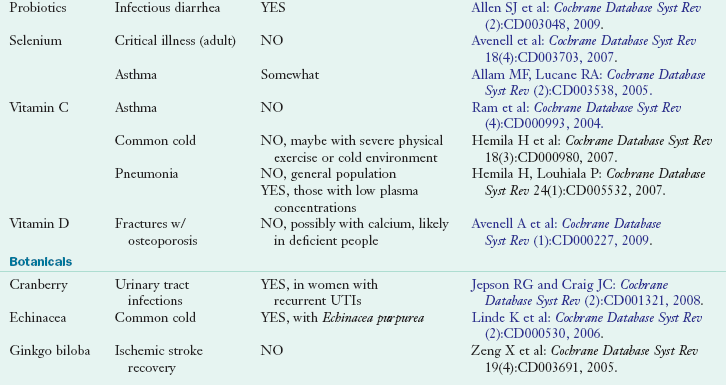

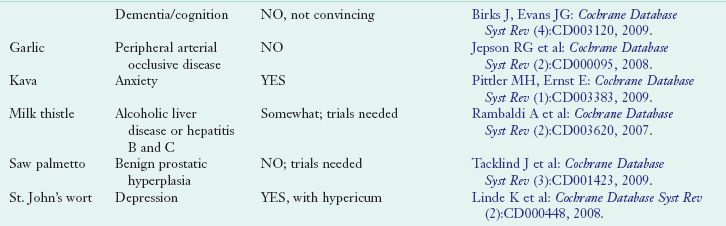

Use of herbal products has been more difficult to evaluate; products are often taken intermittently to treat specific health care problems, and use can be quite variable. Some herbal products commonly consumed include St. John’s wort, echinacea, garlic, saw palmetto and ginkgo biloba, ginseng, soy, valerian, cranberry, and black cohosh (Ernst, 2005). For several dietary supplements enough evidence has accumulated to justify an evidence assessment report by multidisciplinary teams of scientific experts under the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the preparation of a Cochrane Database Review (CDR). A CDR is published as a summation of efficacy and safety of the use of a select supplement in specific medical conditions. Table 13-2 presents commonly used dietary supplements and related information regarding clinical efficacy in the form of CDR.

TABLE 13-2

Select Cochrane Database Reviews of Nutrient and Botanical Supplementation Efficacy

Cochrane Database reviews can be found online at: www.cochrane.org/reviews and are also listed in MedLine and PubMed peer-review citation indexes.

CRC, Colorectal cancer; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; HTN, hypertension; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Potentially At-Risk Populations

Although dietary supplementation is most common among those who are likely to be at lowest risk for nutrient deficiency, select groups within the population are more likely to require dietary supplementation. For example, dietary intake inadequacies have been reported among the elderly (Chernoff, 2005), those of lower socioeconomic status (Karp et al., 2005), and those on energy- or fat-restricted diets (Dwyer et al., 2005). In addition, select physiologic states such as pregnancy and lactation increase requirements for select nutrients (e.g., iron, calcium, folate) that are sometimes difficult to meet through dietary changes alone. Furthermore, chronic illness may result in either increased requirements for certain nutrients (e.g., malabsorptive disorders and general supplementation, osteoporosis and bone-related nutrients, elevated serum homocysteine levels in cardiac disease, and increased B vitamin requirements). Finally, lifestyle choices may increase nutrient needs (e.g., increased vitamin C requirement in smokers, increased folate requirement in alcohol users, and increased iron requirements in iron-deficient athletes). Thus clinicians should be aware of these at-risk subgroups and complete a nutrition assessment to determine the need for supplementation on an individual basis. See Chapters 6 and 8.

Routine use of multivitamin-mineral supplements may be an appropriate recommendation to ensure dietary adequacy. Because many American adults do not meet even the estimated average requirement for vitamin C, D, and E or minerals such as calcium, many suggest that adults in the United States should regularly take a multivitamin-mineral supplement. To further address this issue, the NIH convened a Conference on Multivitamin/Mineral Supplements and Chronic Disease Prevention in 2006 to develop a consensus statement. Even though the panel report states that there is insufficient evidence to show that multivitamin-mineral supplements will reduce the risk for certain chronic diseases (see full report at http://ods.od.nih.gov/news/Results_of_MultivitaminMineral_Supplements_2006.aspx; Neuhouser, 2009), many nutrition practitioners and health care providers continue to recommend a daily multivitamin-mineral supplement to their patients on a routine basis. In some instances supplementation is considered standard of practice. An example is the recommendation that all women of childbearing age take a multivitamin with 400 mcg of folic acid to reduce the risk for neural tube defects in unborn children.

In the area of botanical supplementation there is less evidence of the existence of at-risk populations who require supplementation. Rather, botanical supplements are more generally used to alleviate symptoms of illness or disease. There can be wide variability in response, and routine recommendations for all patients may not be appropriate For example, although there is some support for the use of garlic to reduce serum cholesterol levels, routine supplementation with garlic for all patients with hypercholesterolemia is not appropriate. The patient may be taking prescription medications to treat the elevated cholesterol, may be at risk for increased bleeding time with long-term garlic use, or may be intolerant of the potential gastrointestinal discomfort of supplemental garlic.

In addition to reviewing the available evidence, an assessment of each patient’s clinical situation is important. If the therapy is both effective and safety has been demonstrated, recommending a dietary supplement or a CAM therapy may make sense. Unfortunately, either the evidence for CAM therapy is not clear and consistent (especially in regard to general lack of studies) or safety is a concern. These gray areas are challenging for clinicians when making specific recommendations. Certainly the use of a CAM or dietary supplement that has not been shown to be effective and carries a safety risk should be discouraged.

Dietary Supplement Regulation

Botanical products are regulated in the United States as dietary supplements. The DSHEA of 1994 clarifies marketing regulations for botanicals and reclassifies them as dietary supplements, distinct from food or drugs. A variety of potential labeling approaches are used by the dietary supplement industry to market supplements. These include qualified health claims; unqualified health claims; claims based on an authoritative statement; nutrient content claims; dietary guidance statements; and structure-function claims, which is the most commonly used approach.

A health claim is a written claim on the dietary supplement label that has two essential components: (1) a substance and (2) a disease or health-related condition. It describes the relationship between these two components; a statement lacking either of these components does not meet the regulatory definition of a health claim. Furthermore, it must meet the significant scientific agreement standard and requires prenotification of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Although it does require approval by the FDA, a general health claim does not require the level of scientific evidence of a qualified health claim.

A qualified health claim is a label health claim based on emerging scientific evidence that, on review of this evidence by the FDA, is approved for use on a food or dietary supplement label, given sufficient evidence exists to make the requested label claim (see Chapter 12 for more details). Remember that qualified health claims must be petitioned for by a body outside the FDA such as the supplement manufacturer; thus, although evidence may exist for use of select dietary supplements for select health symptoms, unless a request is formally made to FDA, such a claim will not be developed. Other types of health claims are the authoritative statement (FDA Modernization Act of 1997) and dietary guidance statements, which are based on published statements from authoritative organizations and agencies, as well as statements found within the body of the dietary guidelines.

Of greatest concern is the set of structure-function claims. Under DSHEA, the physiologic effects of a product can be noted, but no claims about prevention or cure of specific conditions can be made. A product manufacturer cannot claim that a dietary supplement “prevents heart disease,” but it can state that the product “helps increase blood flow to the heart.” Such subtle differences are unlikely to be discerned by the average consumer, leading to misinterpretation and potentially inappropriate use of the products. Furthermore, these claims do not require FDA prenotification, and the manufacturer assumes responsibility for ensuring the accuracy and truthfulness of the statement. All products must display the following disclaimer: “This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.” However, there is no research as to the awareness or interpretation of this statement by consumers. Consumers must educate themselves about the appropriate application of each dietary supplement they choose to use and about selection of quality products.

A report from the International Food Information Council (IFIC) suggests that consumers cannot clearly distinguish qualified from unqualified health claims and that they prefer structure-function claims for their positive focus and brevity. Among the more common problems that have been reported since the passage of DSHEA are misrepresentation of product contents; variable potency and recommended dosages among products; inadequate information about how a company’s herbs are grown and processed; and poor standards of quality, product safety, or activity of ingredients. Although rare, herb contamination and misidentification do occur. Governmental and industry entities have developed high-quality manufacturing guidelines (good manufacturing practices [GMPs]) for all dietary supplements, including botanical products. Under the GMP rule manufacturers are required to establish and meet specifications for identity, purity, quality, strength and composition of dietary supplements (Food and Drug Administration, 2007)

In December 2006 the Dietary Supplement and Nonprescription Drug Consumer Protection Act was signed into law, setting requirements for both labeling and mandatory (rather than voluntary) AE reporting related to dietary supplement and over-the-counter (OTC) medication interactions (Frankos, 2009).

Another agency has international significance. The Codex Alimentarius Commission (Codex) was created in 1963 by two U.N. organizations, the Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization, to protect the health of consumers and to ensure fair practices in international food trade (Food and Drug Administration, 2010). Codex participants work on the development of food standards, codes of practice, and guidelines for products such as dietary supplements. Codex standards and guidelines are developed by committees from 180 member countries, where they voluntarily review and provide comments on standards at several stages in the development process (Crane et al., 2010).

Assessment Of Dietary Supplement Use

Popular interest in the use of dietary supplements for health applications is widespread in the United States. Health care professionals should be aware that, although nutrient supplementation is generally recommended to enhance the relative adequacy of the diet or to meet increased requirements associated with illness or disease, the therapeutic action of many botanical products is similar to that of drugs; so the potential for harmful interactions exists. Consumers may not be well informed about the safety and efficacy of supplements and some have difficulty interpreting product labels (American Dietetic Association, 2009).

Health care professionals should also be aware that their patients typically do not inform them of their use of botanicals or other dietary supplements; practitioners must inquire about the use of supplements by their patients. To facilitate obtaining information, health care providers should approach patients in an open, nonjudgmental manner. Key items and issues to be inquired about are summarized in Box 13-2. Not only should all dietary supplements be reviewed, but it is recommended that patients bring all supplements into the clinic to be evaluated. In this way the health care provider can review dose, dosage form, additive sources of the same nutrient or botanical, frequency of use, rationale for use, any identified side effects, and the patient-perceived efficacy of each supplement. This should be done on a regular basis. It is particularly important that dietary supplement use be reviewed before surgery because some dietary supplements and botanicals alter the rate of blood coagulation. Table 13-3 provides specific recommendations regarding the discontinuation of dietary supplements before surgery to avoid complications associated with prolonged bleeding time.

TABLE 13-3

Recommended Times for Preoperative Discontinuation of Select Common Dietary Supplements

| Dietary Supplement | Recommended Discontinuation Time Before Surgery |

| Echinacea | Insufficient data |

| Garlic | 7 days |

| Gingko | 36 hours |

| Ginseng | 7 days |

| Kava | 24 hours |

| St. John’s wort | 5 days |

| Valerian | Insufficient data |

| Vitamin E | 7 days |

Data from Ang-Lee MK et al: Herbal medicines and perioperative care, JAMA 286:208, 2001.

Although a listing of efficacy and safety issues of select supplements is provided in the form of Cochrane database reviews in this chapter (see Table 13-3), the list is somewhat limited. A more extensive list is not provided because it is imperative that practitioners seek current data sources for this information, which is expanding rapidly. Practitioners should use the most up-to-date information when formulating recommendations for their patients. See Box 13-3 for a listing of reliable and comprehensive data sources.

Intake and follow-up information about these therapies provides important pharmacologic and treatment information for the health care provider. In particular, dietary supplements that have similar actions to prescription and OTC medications should generally not be combined, because the effects can be additive and cause harm (DeBusk, 2000). Conversely, dietary supplements that counter the effects of prescription and OTC medications should not be combined, such as taking a blood pressure–lowering medication along with a botanical that can raise blood pressure. Funding studies that evaluate botanical-drug interactions is a priority of the NCCAM.

Beyond evaluating the efficacy of dietary supplements, safety must also be addressed. Although select safety issues have been identified, some may go unreported and use of that supplement discontinued, with no formal report of the AE being filed. As an example, more than 4 million Americans are taking antithrombotic therapy. Approximately 180 dietary supplements have been identified as having anticoagulation, antiplatelet, antagonistic, or drug-metabolizing activity. AEs should be reported to the health care institutions, poison control centers, and MedWatch. Manufacturers of dietary supplements should also maintain their own reporting system for AEs (Talati and Gurnani, 2009).

AEs should be reported to MedWatch. Reports can be filed by the individual, health care provider, or industry. AE reports are forwarded to the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition where they are further evaluated by qualified reviewers. In 2008 a total of 1,080 reports were filed—the majority from mandatory rather than voluntary sources. The majority were related to use of vitamins or mixed-nutrient products (Frankos, 2009).

Many health care professionals remain uncomfortable recommending dietary supplements. Guidelines for recommending and selling dietary supplements and a clinical practice paper have been previously published (Thomson et al., 2005). Internet resources are listed at the end of this chapter. An algorithm for assessing and recommending dietary supplements is presented. Practitioners must take the initiative to develop the appropriate knowledge, skills, and resources to provide optimal care in the area of dietary supplementation.

Guidelines For Counseling

The goal of CAM counseling is to determine which supplements clients are using and the health goals they hope to achieve through the use of these products. People typically do not divulge their use of dietary supplements or CAM use to their health care practitioners. This is especially true for minority racial and ethnic groups. It is imperative that the practitioner establish rapport with the client to enhance disclosure of CAM use (Chao, 2008). Being nonjudgmental of the client’s practices fosters a constructive dialogue. The health care practitioner’s role is as a coach who helps clients assess the need for supplements and helps them to become more knowledgeable about their options (see Box 13-2).

For discussion of dietary supplement use, clients should bring with them all prescriptions, OTC medications, and dietary supplements they are using. In addition, a dietary supplement intake assessment form should be completed by each patient or client and reviewed in detail by the health care provider. Note that, in addition to a listing of specific supplements, nutrients, and botanicals, the form also identifies the health conditions that motivated the use of supplements. In the case of calcium, it is also imperative to collect information about antacid use because this is a major source of calcium supplementation.

Each supplement should be discussed individually in terms of what the client hopes to achieve by using that supplement, whether the preparation is appropriate for the client’s health goals, and whether the dosage being taken and the length of time for supplementation is supported by published clinical trials. How to recognize a quality preparation for each supplement (in particular if the manufacturer is compliant with GMPs), any known safety concerns and contraindications, and any known or potential interactions between each supplement and prescription or OTC medications and other dietary supplements or foods should also be reviewed (see Chapter 9).

The client should be instructed to use the dosage commonly recommended for that specific botanical. A low starting dose, even less than the recommended dose, should be encouraged and the response monitored to minimize the chances of an adverse reaction. Dietary supplement use by clients provides an excellent platform for teaching consumers analytic skills that will serve them well in their pursuit of increased self-management of their health.

The Office of Dietary Supplements has developed facts sheets for an extensive list of dietary supplements that can be used by health care professionals to educate patients. The FDA has published tips for the dietary supplement user in making informed choices regarding which supplements to consider taking. Tips include advice regarding (1) assessment of present diet, (2) informing health care providers of dietary supplement use, (3) potential medication–dietary supplement interactions, (4) reporting of AEs, and (5) assessment of the validity of information. See Box 13-4 for issues to consider when choosing a botanical.

Resources for Clinicians

As awareness of dietary supplement use expands within the health care community, the number of evidence-based resources available to clinicians is also growing considerably. It is advisable that clinicians have access to at least one online resource that is updated at regular intervals. Resources that provide reference to the original research are preferable. In addition, accessing available medical literature is advised, given that there are a growing number of studies being published in peer-reviewed literature. Finally, contacting health care providers and researchers who are actively working in this area can be invaluable in terms of increasing awareness of safety issues, understanding mechanisms of biologic activity, and assessing the level of evidence for clinical efficacy.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Arthritis Foundation Supplement Guide

http://www.arthritistoday.org/treatments/supplement-guide/conditions.php

http://nccam.nih.gov/camonpubmed/

Computer Access to Research on Dietary Supplements

http://dietary-supplements.info.nih.gov/Research/CARDS_Database.aspx

Dietary Supplements Labels Database

http://dietarysupplements.nlm.nih.gov/dietary

http://www2.Cochrane.org/reviews/

Food and Drug Administration—Dietary supplement advice

http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm153239.htm

Institute for Functional Medicine

http://www.functionalmedicine.org

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s About Herbs, Botanicals & Other Products

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine

http://ods.od.nih.gov/Health_Information/Health_Information.aspx

References

Ahn, AC, et al. Applying principles from complex systems to studying the efficacy of CAM therapies. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:1015.

Allam MF, Lucane RA: Selenium supplementation for asthma, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003538, 2005.

Allen SJ, et al: Probiotics for treating infectious diarrhea, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003048, 2009.

American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: nutrient supplementation. Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:2073.

Ang-Lee, MK, et al. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286:208.

Archer, SL. Association of dietary supplement use with specific micronutrient intakes among middle-aged American men and women: the INTERMAP Study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:1106.

Avenell A, et al: Selenium supplementation for critically ill adults, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003703 October 18, 2007.

Avenell A, et al: Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD000227, 2009.

Barnes, P, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;10(12):1.

Birdee, GS, et al. Factors associated with pediatric use of complementary and alternative medicine. Pediatrics. 2010;125:249.

Birks J, Evans JG: Ginkgo biloba for cognitive impairment and dementia, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003120, 2009.

Bjelakovic G, et al: Antioxidant supplements for preventing gastrointestinal cancers, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 18(4):CD004183, 2008.

Bjelakovic G, et al: Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with diseases, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 16(2):CD007176, 2008.

Chao, MT, et al. Disclosure of complementary and alternative medicine to conventional medical providers: variation by race/ethnicity and type of CAM. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:1341.

Chernoff, R. Micronutrient requirements in older women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:1204S.

Crane, NT, et al. The role and relevance of Codex in Nutrition Standards. Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:672.

DeBusk, RM. Herbs as medicine: what you should know. Tallahassee, FL: PR Treadwell; 2000.

Dickinson HO, et al: Calcium supplementation for the management of primary hypertension in adults, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD004639, 2009.

Dwyer, JT, et al. Dietary supplements in weight reduction. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:80S.

Ernst, E. The efficacy of herbal medicine-an overview. Fundamental Clin Pharmacol. 2005;19:405.

Evans JG: Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) supplementation for cognitive function, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD006221, 2006.

Evans JR: Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for age-related macular degeneration, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD000254, 2009.

Farmer Miller, N, et al. Dietary supplement use in individuals living with cancer and other chronic conditions: a population-based study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:483.

Food and Drug Administration. Current good manufacturing practice in manufacturing, packaging, labeling, or holding operations for dietary supplements. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2007;72:34751.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA). What is Codex? Accessed 24 May 2010 from http://www.fda.gov/Food/DietarySupplements/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ucm113860.htm#what.

Frankos, VH, et al. FDA regulation of dietary supplements and requirements regarding adverse event reporting. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:239.

Hemila H, et al: Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 18(3):CD000993, 2007.

Hemila H, Louhiala P: Vitamin C for preventing and treating pneumonia, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 24(1):CD005532, 2007.

Hofmeyr GT, Atallah AN, Duley L: Calcium supplementation during pregnancy for preventing hypertensive disorders and related problems, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD001059, 2010.

Hooper L, et al: ω 3 fatty acids for prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003177, 2009.

Institute of Functional Medicine. Website http://www.functionalmedicine.org/about/whatis.asp. [accessed 1/16/2011.].

Jepson RG, Craig JC: Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD001321, 2008.

Jepson RG, et al: Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD000095, 2008.

Karp, RJ, et al. The appearance of discretionary income: influence on the prevalence of under and over nutrition. Int J Equity Health. 2005;28:4.

Kiefer, D, et al. An overview of CAM: components and clinical uses. Nutr in Clin Pract. 2009;24:549.

Linde K, et al: Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD000530, 2006.

Linde K, et al: St John’s wort for depression, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD000448, 2008.

Maizes, VM, et al. Integrative medicine and patient-centered care. Explore (NY). 2009;5(5):277.

Maloulf R, et al: Folic acid with or without vitamin B12 for cognition and dementia, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD004514, 2008.

Marra, MV, et al. Position of the American Dietetic Association: nutrient supplementation. JADA. 2009;190:2073.

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). NCCAM funding: appropriations history. Accessed 8 December 2005 from www.nccam.nih.gov/news/camsurvey.htm.

National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dietary supplements labels database. Accessed 20 May 2010 from http://dietarysupplements.nlm.nih.gov/dietary/.

Neuhouser, ML, et al. Multivitamin use and risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease in the Women’s Health Initiative cohorts. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:294.

Pittler MH, Ernst E: Kava extract for treating anxiety, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003383, 2009.

Rambaldi A, et al: Milk thistle for alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C virus liver diseases, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003620, 2007.

Rumbold A, et al: Antioxidants for preventing pre-eclampsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev D004227, 2008.

Sommerfield T, et al: ω-3 fatty acids for intermittent claudication, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003833, 2007.

Tacklind J, et al: Serenoa repens for benign prostatic hyperplasia, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD001423, 2009.

Talati, AR, Gurnani, AK. Dietary supplements adverse event reports: review and analysis. Food & Drug Law J. 2009;64:503.

Thomson, CA, et al. Practice Paper of the American Dietetic Association: dietary supplements. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:460.

Turner D, et al: ω 3 fatty acids (fish oil) for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD006320, 2009.

Ullman, D. A review of a historical summit on integrative medicine. eCAM Advance Access. 31 August 2009. [doi:10.1093/ecam/nep128].

Weingarten MA, et al: Dietary calcium supplementation for preventing colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003548, 2008.

Zeng X, et al: Ginkgo biloba for acute ischaemic stroke, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 19(4):CD003691, 2005.