Chapter 26 Active first stage of labour

Labour, the culmination of pregnancy, is an event with great psychological, social and emotional meaning for the mother and her family. In addition, many women experience stress and physical pain. The midwife and all other supporters should display tact and sensitivity, respect the needs and choices of the individual woman and provide an environment which enables her to labour and give birth with dignity.

Communication and environment

In Europe, the vast majority of women opt to give birth in hospital or a birth centre. However, some may choose to give birth in their own home where they may feel they have more control over the environment so reducing fear.

The woman should decide where to give birth only after full and unbiased discussion of her options and the associated benefits and potential risks in terms of outcomes. There are times, when the midwife should advise the woman in individual circumstances (Sinivaara et al 2004). Once a decision has been made, her choice should be supported.

Currently in the UK most births occur in hospital, therefore the atmosphere and environment of hospital birthing rooms are important (Sullivan & McCormick 2007). Soft furnishings, the use of colour and the arrangement of appropriate furniture can help to soften a hospital atmosphere with its implications of sickness and institutional rules. The attitude of the staff, however, is much more important than physical surroundings. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the Royal College of Midwives in their joint report ‘Towards safer childbirth’ (RCOG/RCM 1999) make specific recommendations regarding making ‘delivery’ rooms more homely. This includes furnishings that allow women to adopt a variety of positions in labour, as well as the provision of dedicated bereavement rooms.

Good communication on labour wards between women and midwives, midwives and doctors, and doctors and women can have enormous impact (Crofts et al 2006, Hunter 2006, Lewis 2007). Labour ward staff having a shared philosophy and communicating well in multidisciplinary forums are helpful in improving the culture of busy labour wards. Improvement of multidisciplinary communication should be actively sought. Risk management issues and statutory supervision must be dealt with in a way that positively develops and supports staff. Communication is not only the content of what is said but includes non-verbal communication, written birth plans and involvement of the whole team in decision making. The 8th annual report from the Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy (CESDI 2001) reiterated that all healthcare professionals involved in maternity care should be vigilant in identifying and communicating risk factors to specialist services, and that plans for both antenatal and intrapartum care should be made. Lewis (2007) also cites lack of communication, teamwork and cross-agency working as contributory factors in maternal death.

Prior to admission to a hospital, the woman should have been given good information about the physical process of labour and should have considered what strategies she may use to cope during the birth. It is essential that the labouring woman is welcomed and encouraged to feel at ease, and most of all that the midwife spends time actively listening as the woman recounts the details of the onset of labour.

Emotional support

The midwife has a defined role to fulfil which includes both physical and emotional assessment. Emotional support is provided by exercising skill in imparting confidence, expressing caring and dependability as well as being an advocate for her if needed. Clinical assessment includes the progress of labour and the physical status of mother and fetus. The midwife should display a tolerant non-judgemental attitude, ensuring that the woman is accepted whatever her reactions to labour may be.

Companion in labour

For more than 20 years, research has consistently shown that continuous one-to-one support of a woman during labour creates a strong feeling of security and satisfaction as well as having a positive effect on outcomes (Ball 1994, Hodnett & Osborn 1989a,b, Langer et al 1998, Madi et al 1999). A meta-analysis by Hodnett (2001) demonstrates a number of benefits of one-to-one care for mothers and babies. These include reduction in pain relief, in operative vaginal delivery and caesarean section as well as in length of labour; there were no harmful effects demonstrated. Women greatly value companionship and social support in labour (Price et al 2007).

The woman herself is central to all the decisions made about care during labour. Her chosen companion, whether sexual partner, friend or family member, should understand this. Ideally the companion should be involved in pre-labour preparation and decision-making. The companion should have participated in compiling a birth plan and any contingency plans drawn up in the event of change.

Admission to hospital labour wards is often an unknown entity and the company of a supportive companion can help reduce anxiety. During labour, the companion can keep the woman company, walk with her if she is ambulant, support her decisions about pain relief and encourage her with whatever she has chosen as her coping mechanism. Providing encouragement and reassurance that labour is progressing is also important, as is helping with physical comfort. In some areas a midwife will be able to remain with one woman through her entire labour but due to the unpredictable workloads on busy labour wards this is not always possible. Students can play an invaluable role in providing support.

The midwife should appreciate that the companion may also need direct support at times. This is particularly evident when a sudden emergency develops. If, for instance, a caesarean section becomes necessary, the midwife should delegate someone to keep the companion as informed as the woman wishes and ensure that he or she is not left feeling abandoned or uncared for.

Consent and information giving

Consent

Common law in the UK has developed rules that require patients to agree in meaningful terms to any recommended treatment. As Lord Donaldson has said (Re F 1990) ‘The ability of the ordinary adult to exercise free choice in deciding whether to accept or refuse medical treatment… is a crucial factor in relation to all medical treatment’. It can therefore be concluded that patient autonomy is protected only when there is a meaningful choice made by the patient on the basis of adequate information and comprehension of that information.

Women need sufficient information before they can decide whether to give their consent, for example information about the benefits and risks of the proposed treatment, and alternative treatments. If she is not offered as much information as she reasonably needs to make her decision, and in a way she can understand, then consent may not be valid.

Consent must be given voluntarily, not under any form of duress or undue influence from health professionals, family or friends. It can be written or verbal. It is a common misunderstanding that a patient’s signature on a consent form proves the consent is valid. This is not always the case. In an absolute emergency, it may be more appropriate to take witnessed verbal consent as more time can be spent on discussion and explanation and less on paperwork. In this scenario, it must be carefully documented in the case notes.

Under common law, a competent adult, including a competent pregnant woman, has the right to refuse medical treatment, however unreasonable this is deemed to be, even when the life of herself or her fetus is at risk. This is true whether the reason is rational or irrational, or even when there is no reason at all. The courts have no jurisdiction to declare non-consensual treatment of competent women (women that have capacity) to be lawful. Only when a baby has been born does it acquire rights.

There are exceptions to this rule, e.g. where the treatment is for a mental disorder and the patient is detained under the Mental Health Act of 1983.

A person lacks capacity if some impairment or disturbance of mental functioning renders that person unable to make a decision about treatment. This will occur when the person is unable to comprehend and retain the information material to the decision, or when the person is unable to retain information and weigh it in the balance as part of the process of arriving at a decision. Incapacity may be temporary, for instance if caused by shock, pain, fatigue, confusion, or panic induced by fear. If a healthcare professional fears a patient’s decision-making (capacity) is impaired they should ask for help is assessing capacity. The Law Commission is keen to ensure that any decisions taken do not violate the European Convention on Human Rights. It is envisaged that, in the future, statutory protection will be given to the informal way decisions are currently made on behalf of incapacitated adults.

Midwives must provide support by giving information that ensures the woman understands events, feels free to ask questions and is aware of how labour is progressing. Before performing any examination, verbal permission should be sought, and explanations should be given of what is about to be done and why. Following any procedures, the midwife should provide feedback and verbal reinforcement; she can only then involve the woman in making further decisions about care. Relatives cannot give consent on behalf of a competent woman; it is only the woman herself who can give consent. It is an important principle that a midwife remembers no one else can consent on behalf of a competent adult.

Prevention of infection

Hospitals are notorious sources of infection, which can be resistant to antibiotic treatment. Effective cleaning will reduce the transfer of airborne organisms. A balance between encouraging visitors and accommodating lots of unnecessary people in a birthing environment should be considered. Where the birth is not occurring at home, baths, sinks and toilets should be scrupulously cleaned and disinfected between users as necessary. Beds and rooms must also be cleaned thoroughly after use. It is part of ensuring a safe environment for the midwife to ensure that high standards of cleanliness are maintained even if she does not have managerial control over domestic services.

Personal hygiene is important for both mothers and their attendants. The woman should be encouraged to bathe and wash as she wishes to maintain personal freshness and the midwife must wash her hands before and after examining the mother and wear gloves when handling used sanitary pads, bloodstained linen or body fluids.

In the healthy woman, the immune system is the body’s defence against not only bacteria and viruses but also other foreign organisms or harmful chemicals. It is very complex and it has to work properly to protect us from harmful bacteria and other organisms. Women with problems during pregnancy may have less resistance to combat infection. Some women will need very specialized care, especially women with any transmissible infection such as gastroenteritis, hepatitis or HIV infection.

Women with problem-free pregnancies and labours should be encouraged to stay in their own environment as long as possible, thus reducing the time spent in hospital. If a woman in normal labour is able to stay at home during the latent phase of labour this may also reduce the diagnosis of prolonged labour.

True prolonged labour increases the risk of infection and haemorrhage. Once the woman is admitted to hospital, invasive procedures should be kept to a minimum as an intact skin provides an excellent barrier to organisms.

The fetal membranes should also be preserved intact unless there is a positive indication for their rupture that would outweigh the advantage of their protective functions (Clements 2001). Certain invasive techniques, such as the performance of vaginal examinations, may be deemed necessary during labour. However, the midwife should ensure that she has a sound reason before embarking on any procedure. Women whose labours are prolonged are at particular risk of infection and are often subjected to a number of invasive procedures including the administration of intravenous fluids, repeated vaginal examinations, epidural analgesia and fetal blood sampling.

Pre-labour rupture of fetal membranes at term

The incidence of pre-labour rupture of membranes (PROM) at term (>37 weeks) is between 8–10% of all pregnancies (NICE 2008), and most women with PROM will labour spontaneously within 24 hrs. Following PROM with no signs of labour and no obvious liquor draining, digital examination should be avoided owing to an increased risk of ascending infection. If there is any uncertainty regarding the status of the membranes and in the absence of any pathology (including meconium staining), a woman may wear a pad for an hour or two then, with the midwife, reassess the clinical findings. Where there are facilities and the diagnosis of ROM is ambiguous, one sterile speculum examination should be performed to try and visualize pooling of liquor in the posterior fornix. Endocervical swabs may also be taken at this time.

Management of rupture of membranes

Active management has been shown to slightly reduce maternal infectious morbidity and admissions of babies to neonatal intensive care though neonatal infection rates were not increased (Dare 2006). Active management should most commonly be with the use of vaginal prostaglandins but may alternatively be via intravenous oxytocin depending on individualized care. Women with pre-labour ruptured membranes who opt for expectant management should have their temperature monitored and auscultation of the fetal heart to exclude a fetal tachycardia or other signs of fetal compromise associated with infection. This observation does not necessitate hospital admission in an otherwise uncomplicated pregnancy. Women should be given adequate information to decide between expectant management or active management of labour following pre-labour rupture of membranes.

Pre-term pre-labour rupture of membranes

In pre-term pregnancies, complicated by pre-labour rupture of membranes the presentation is often not cephalic. Transfer to a hospital with appropriate neonatal facilities is required. Corticosteroids reduce the incidence of respiratory distress syndrome and neonatal death. The use of antibiotics (specifically erythromycin) reduces neonatal treatment and is associated with prolongation of pregnancy (Kenyon et al 2001). Expectant management is usually considered until 34 weeks when individualized decisions would be made (RCOG 2006).

Position and mobility

A prospective RCT (de Jong et al 1997) demonstrated that women who adopt an upright position during labour experience significantly less pain and suffer less perineal trauma. Lateral and posterior position of the fetal presenting parts may be associated with more painful, prolonged or obstructed labour and difficult birth. It is possible that maternal posture may influence fetal position (Hofmeyr & Kulier 2001).

Women should be encouraged to give birth in the position they find most comfortable. Sutton & Scott (1995) have written and taught much on optimal fetal positioning. The benefits and risks of various labour and birthing positions need to be examined to ensure greater certainty. When methodologically stringent trials data are available, then women should be encouraged to use this information to make informed choices about the birth positions they might wish to assume. Midwives must be flexible in their approach to positions that women adopt as well as considering their own health, for example when assuming positions such as leaning to one side for sustained periods to assist women giving birth in a semi-sitting position on a labour ward bed.

Analgesia

Women should be aware of the advantages and disadvantages of all methods of analgesia available to them in their chosen birth environment. This is an essential part of antenatal education and the chosen method of analgesia may affect outcomes (see Ch. 27). Epidural analgesia gives the most effective pain relief in labour but is associated with increased rates of instrumental birth. The Comparative Obstetric Mobile Epidural Trial (COMET) study group (2001) reported a normal delivery rate of 35.1% with ‘traditional epidural’ and 42.7% with low dose (mobile) epidural.

Monitoring the fetus

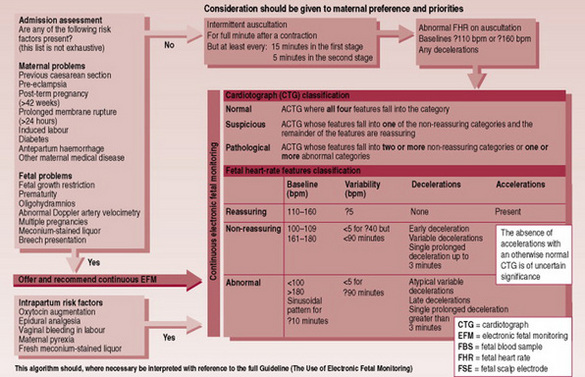

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE 2001b) has recommended that women with an uncomplicated pregnancy should not have electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) as a routine, but that intermittent auscultation with a Pinard stethoscope or handheld Doppler device should be the monitoring of choice. In this group of women there is no evidence to support an admission cardiotocograph (CTG); it should therefore not be done as routine.

The term ‘intermittent auscultation’ is used when the fetal heart is auscultated at intervals using a monaural fetal stethoscope (Pinard’s) or a handheld Doppler device. Doppler apparatus can be used throughout a contraction, but listening during a contraction with a monaural stethoscope (Pinard) is uncomfortable for the woman and the fetal heart sounds may be inaudible. Using a Pinard the midwife can listen in to the fetal heart rate as the contraction is finishing to detect any slow recovery of the fetal heart rate back to the baseline.

The baseline rate should be between 110 and 160 b.p.m.

Normally the baseline rate is maintained during a contraction and immediately after it. However, in late labour some decelerations with contractions that recover quickly may be due to cord compression or compression of the fetal head and are normal.

Variability of >5 b.p.m. should be maintained throughout labour. The rate of the fetal heart should be counted over 1 complete minute in order to listen for the beat-to-beat variation. Variability can be confirmed by counting the number of fetal heartbeats heard in a 5 s interval repeating this exercise for one minute. The fetal heart should be auscultated every 15 min when the woman is in established labour. If decelerations are heard in the first stage of labour with a Pinard or Doppler instrument, then electronic monitoring may be indicated to assess the extent of decelerations.

Electronic fetal monitoring

Electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) was introduced in the 1970s with the aim of reducing cerebral palsy. However, a reduction has not been demonstrated and the rate of cerebral palsy remains 2–3/10 000 live births (Parkes et al 2001). What has been demonstrated by the use of continuous EFM is an increase in obstetric intervention.

For women with problems in their pregnancy or other risk factors including the use of oxytocin, or epidural analgesia, EFM is appropriate.

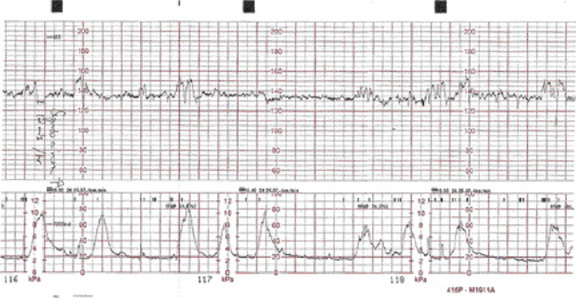

The use of a CTG may appear to limit the choice of position, but telemetric apparatus allows the woman to walk around freely, provided that she remains within a given range. A conventional CTG (Fig. 26.1) does not necessarily confine the woman to bed but accurate external monitoring of uterine contractions may be difficult if she is very mobile.

Interpretation of CTG

Hospitals should ensure that staff who are performing and interpreting CTG traces have received training and assessment of their skills to ensure these are up-to-date (NICE 2001). The Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts has also set a standard for 6-monthly updating.

Only four variables are considered when interpreting a CTG. The CTG provides information on:

Baseline fetal heart rate

This is the fetal heart rate between uterine contractions. A rate more rapid than 160 b.p.m. is termed baseline tachycardia; a rate slower than 110 b.p.m. is baseline bradycardia. Either may be indicative of fetal compromise due to a number of causes. If the baseline is outside the stated normal range then referral to an obstetrician is appropriate.

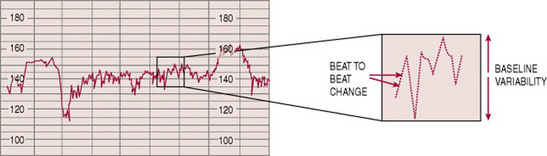

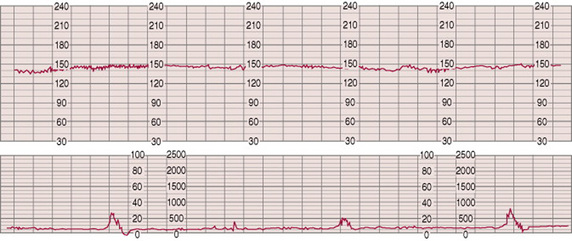

Baseline variability

Electrical activity in the fetal heart results in minute variations in the length of each beat. This causes the tracing to appear as a jagged rather than a smooth line (Fig. 26.2). The baseline rate should vary by at least 5 beats over a period of 1 min. Loss of this variability (Fig. 26.3) may indicate fetal compromise. Reduced variability may be noted for a short period after the administration of maternal diamorphine/pethidine, which depress the fetal brain. Periods of ‘fetal sleep’ also cause a reduction in variability and commonly last for 20–30 min even in advanced labour (Gibb 1988, Lowe & Reiss 1996).

An acceleration is a brief rise in the fetal heart rate of at least 15 beats, for at least 15 s.

A deceleration is a drop from the baseline of 15 beats for >15 s but <3 min.

A deceleration of the fetal heart rate lasting longer than 3 min is referred to as a bradycardia.

Response of the fetal heart to uterine contractions

The fetal heart rate will normally remain steady or accelerate during uterine contractions during the first stage of labour. In order to assess the significance of fetal heart rate decelerations accurately, their exact relationship to uterine contractions, size, shape and uniformity must be noted. Compression of the umbilical cord, or fetal head, will result in some decelerations, particularly if the membranes are not intact. These would be early or variable decelerations lasting <3 min with good recovery to pre-deceleration rate.

This analysis of the fetal heart rate makes a CTG interpretable into the three categories recommended by NICE (2001) (Fig. 26.4):

This is of course a rather simplistic view, as the whole picture of labour must be taken into account, including the gestation, any complications, particularly if the baby is not well grown and is presumed to have less reserves, as well as the stage and length of that specific labour. These guidelines are an aid to clinical judgement with the exception of clearly pathological traces.

All CTG traces should be secured in the notes and kept for a minimum of 25 years, along with all other maternity records.

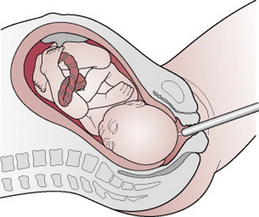

Fetal blood sampling

Units that use electronic fetal monitoring should have 24 hrs access to fetal blood sampling (FBS) facilities. When the fetal heart rate pattern is suspicious or pathological and fetal acidosis is suspected, then FBS should always be carried out NICE (2001). The procedure should be carried out with the woman in the left lateral position as a lithotomy position is more distressing for both mother and fetus (Fig. 26.5). If imminent delivery is clearly indicated by a severely pathological CTG, then no time should be wasted performing an FBS. This would be the clinical decision of a senior obstetrician. A fetal blood sample result of ≤7.25 should be repeated usually within 30 min to 1 hr. An FBS <7.20 indicates that the baby should be delivered.

Nutrition

Despite food and drink nowadays being more freely available to most women in labour, once in established labour, most women have no desire to eat, though some fluids should be encouraged. A large amount of women feel nauseated or too distracted to eat. But for those who do not, particularly in the latent phase, women may have a desire for energy rich foods and carbohydrate. Low fat foods, such as toast, breakfast cereal, yoghurt, fruit juice, tea, plain biscuits and clear broth are easily digested. Ice cream and jelly may also be refreshing. Fluids may be taken freely, although women tend to reduce their drinking as labour progresses (Roberts & Ludka 1994).

Intake in normal labour

Opinions are divided and policies vary between hospitals. Most low risk women in spontaneous labour have little risk of requiring an emergency general anaesthetic. Therefore most hospitals will allow such women to take a low fat, low residue diet according to appetite, in order to give her energy and ensure that she is not hungry. However, in some centres, women receive nothing to eat after labour is established and are allowed only ice chips to suck. The latter policy stems from ‘the widespread concern that eating and drinking during labour will put women at an increased and unacceptable risk of regurgitation and aspiration of gastric contents’ (Johnson et al 1989, p 827). Aspirated contents from the stomach may contain undigested food and predispose to airway obstruction. But if the woman has been fasting, the strongly acidic gastric juice can cause a chemical pneumonitis if inhaled (Mendelson’s syndrome). The cardiac sphincter, rendered less efficient by the effects of progesterone, allows a passive leak of stomach contents into the pharynx when loss of consciousness is induced with general anaesthesia. This, combined with the oedema of the pharynx so often present in pregnancy, makes intubation by the anaesthetist a difficult procedure. The answer clearly is to reduce the risk of general anaesthetic and use cricoid pressure during induction of such emergency anaesthetics (see Ch. 32).

Different foods and fluids empty from the stomach at different rates and gastric emptying is prolonged following the administration of narcotic analgesia. Johnson and colleagues point out that there is, however, ‘no guarantee that withholding food and drink during labour will ensure that the stomach will be empty in the event that general anaesthesia should become necessary’ (Johnson et al 1989, p 829). In an effort to reduce gastric volume and decrease the gastric acidity of the labouring woman, prophylactic antacids may be administered (see Ch. 32).

Glycogenic and fluid requirements

The vigorous muscle contractions of the uterus during labour demand a continuous supply of glucose. If this is not obtained from the diet, the body will start to metabolize protein and fat stores in an effort to provide glucose (gluconeogenesis) without which uterine muscle inertia will occur. This relatively inefficient method of producing glucose results in the occurrence of ketoacidosis. High concentrations of intravenous glucose may artificially increase fetal blood glucose levels, thereby causing fetal hyperinsulinism and resulting in hypoglycaemia of the neonate (Lowe & Reiss 1996, Steele 1995).

For women at increased risk of a general anaesthetic, giving small volumes of water or a weak fruit cordial may be acceptable. If the woman is permitted to follow her inclinations about drinking she is unlikely to become dehydrated. Simple measures such as brushing her teeth or using a mouthwash can help relieve the discomfort of a dry and uncomfortable mouth.

Bladder care

The woman should be encouraged to empty her bladder every 1–2 hrs during labour. The midwife should not rely on the mother to request to use the toilet as the sensation of needing to micturate may be reduced, particularly if there is an effective epidural block in progress. If the woman is mobile she may visit the toilet. In women who suffer pregnancy complications and have fluids restricted or an intravenous infusion the quantity of urine passed should be measured and a specimen obtained for testing. As urine in the bladder is a non-compressible mass, it may interfere with descent of the presenting part or reduce the capacity of the uterus to contract, increasing the risk of postpartum haemorrhage.

A full bladder may initially prevent the fetal head from entering the pelvic brim. In all cases of delay in labour, the midwife should ascertain whether the bladder is full and encourage the woman to void regularly. If it is not possible for the woman to use the toilet, the midwife should provide privacy and ensure maximum comfort by placing the bedpan on a stool or chair or encouraging the woman to adopt a squatting position on the bed. The sound or feel of water can also help to trigger the micturition reflex. If the bladder is incompletely emptied or the woman is unable to void for some hours, it may become necessary to pass a catheter.

Observations

The mother

Reaction to labour

As with other major life events, women vary in their reactions to labour. Some may view the contractions experienced as a positive, motivating, life-giving force. Others may feel them as pain and resist them. One woman may welcome the event with excitement because soon she will see her baby; another may be glad the pregnancy is over and with it the cumbersome ungainliness she experienced. However she views labour, the preparatory phase of pregnancy is at an end and within a relatively short period, a baby will be born. There may be feelings of apprehension, fear and worry in case she does not conform to the social expectations of her culture. She may experience anxiety in case childbirth is painful and have concerns about her ability to control pain (Niven 1992). As labour progresses she may feel less confident in her ability to cope with the relentless nature of the contractions that control her body. The midwife, with her skillful observations, advice and assistance, can do much to help her. She can encourage and help the woman and when possible give her one-to-one care. Accurate and easy-to-understand information given to the woman about the progress of labour will provide encouragement. Consultation about methods of pain relief will increase feelings of being in control (Ball 1994, Lovell 1996). The management of pain is discussed in Ch. 27.

Pulse rate

If the rate increases to >100 b.p.m. it may be indicative of anxiety, pain, infection, ketosis or haemorrhage. It is usual to record the pulse rate every 1–2 hrs during early labour and every 30 min when labour is more advanced.

Respiratory rate

Respiratory rate is a good indicator of the general physical condition of the woman. It should be recorded at least every 4 hrs. The rate may be over 20 respirations/min in severe anxiety or other pathologies. Some breathing techniques used in labour by women may make it difficult to monitor. In late labour and second stage, respiratory rates will vary because of the physical effort and strategies for second stage.

Temperature

This should remain within the normal range. Pyrexia is indicative of infection or ketosis, or may be associated with epidural analgesia. In normal labour, the maternal temperature should be recorded at least every 4 hrs and additionally when there is a clinical indication.

Blood pressure

Blood pressure is measured every 2–4 hrs unless it is abnormal, in which case, more frequent recordings will be necessary depending on the individual situation. The blood pressure must also be monitored very closely following epidural or spinal anaesthetic (see Ch. 27). Hypotension may be caused by the supine position, shock or as a result of epidural anaesthesia.

In a woman who has had pre-eclampsia or essential hypertension during pregnancy, labour may further elevate a raised blood pressure.

Urinalysis

Urine passed during labour should be tested for glucose, ketones and protein. Ketones may occur as a result of starvation or maternal distress when all available energy has been utilized. A low level of ketones is very common during labour and thought not to be significant. Unless the non-diabetic mother has recently eaten a large quantity of carbohydrate or sugar, glucose is found in the urine only following intravenous administration of glucose.

A trace of protein may be a contaminant following rupture of the membranes or a sign of a urinary infection, but more significant proteinuria may indicate pre-eclampsia.

Fluid balance

A record should be kept of all urine passed to ensure that the bladder is being emptied. If an intravenous infusion is in progress, the fluids administered must be recorded accurately. It is particularly important to note how much fluid remains if a bag is changed when only partially used.

Abdominal examination

An initial abdominal examination is carried out when the midwife first examines the mother. This should be repeated at intervals throughout labour in order to assess the length, strength and frequency of contractions and the descent of the presenting part. The method is described in Ch. 17.

Contractions

The frequency, length and strength of the contractions should be noted. When a uterine contraction begins, it is painless for a number of seconds and painless again at the end. The midwife, when feeling for contractions, is aware of the beginning of the contraction before the woman feels it. This knowledge can be utilized when giving inhalational analgesia or using other coping mechanisms (see Ch. 27). The uterus should always feel softer between contractions. Contractions, which are unduly long or very strong and in quick succession give cause for concern as fetal hypoxia may develop. Hyperstimulation should be considered if oxytocin is being infused. It should be stopped if fetal compromise or hyperstimulation is apparent.

Descent of the presenting part

During the first stage of labour, descent can be followed almost entirely by abdominal palpation. It is usual to describe the level in terms of the fifths of the head, which can still be palpated above the pelvic brim (see Ch. 17 and Ch. 25).

In the primiparous woman, the fetal head is usually engaged before labour begins. If this is not the case, the level of the head must be estimated frequently by abdominal palpation in order to observe whether the head will pass through the brim with the aid of good contractions.

When the head is engaged, the occipital protuberance can be felt only with difficulty from above but the sinciput may still be palpable, owing to increased flexion of the head, until the occiput reaches the pelvic floor and rotates forwards.

Vaginal examination and progress in labour

Although it is not essential to examine the woman vaginally at frequent intervals, it may be useful to do so when progress is in doubt or another indication arises (see Ch. 25). The features that are indicative of progress are effacement and dilatation of the cervix, and descent, flexion and rotation of the fetal head. There do not appear to be many research-based recommendations on the timing and frequency of carrying out a vaginal examination in labour. As this intervention can be extremely distressing to some women, alternative methods of assessment should be considered (Nolan 2001); routine examinations in normal labour should be abandoned and an individualized approach taken. All examinations should be recorded on the labour record.

The minimal standard of recording should include:

Effacement and dilatation of the cervix

In normal labour, the primiparous cervix effaces before dilating, whereas in the parous woman, these two events often occur simultaneously. The latent phase of labour is usually defined as up to 3–4 cm dilated (see Ch. 25). There is no agreed ‘starting point’ for the onset of labour. However, acknowledging the latent phase and not commencing a partogram too early will reduce the overdiagnosis of ‘failure to progress’ later in labour.

Progressive dilatation is monitored as labour continues and charted on either the partograph or the cervicograph. This will allow for early detection of abnormal progress and indicate when intervention is likely. The use of cervograms to monitor labour has limitations and must be understood and applied appropriately (Gee 2000) (see also Ch. 25).

Descent

When assessed vaginally, the level or station of the presenting part is estimated in relation to the ischial spines, which are fixed points at the outlet of the bony pelvis. During normal labour the head descends progressively. The midwife must be aware, while estimating whether the head is lower than previously, that marked moulding or a large caput succedaneum will give a false impression of the level of the fetal head.

Flexion

In vertex presentations, progress depends partly on increased flexion. When the head is driven down on to the pelvic floor it encounters resistance: the lever principle causes the anterior part of the head to flex because there is less counterpressure. The midwife assesses flexion by the position of the sutures and fontanelles. If the head is fully flexed, the posterior fontanelle becomes almost central; if the head is deflexed, both anterior and posterior fontanelles may be palpable.

Rotation

Rotation is assessed by noting changes in the position of the fetus between one examination and the next. The sutures and fontanelles are palpated in order to determine position. Even if insufficient information is gained to make a definitive diagnosis, a record is made of what is felt and the findings will be evaluated with the abdominal findings at the time and compared with the findings of earlier or later vaginal examinations.

The fetus

Fetal condition during labour can be assessed by obtaining information about the fetal movements, heart rate patterns, the pH of the fetal blood and the colour and amount of amniotic fluid.

The fetal heart

The fetal heart rate may be assessed intermittently by a Pinard stethoscope or handheld Doppler device or continuously using EFM as appropriate.

Amniotic fluid

Amniotic fluid escapes from the uterus continuously following rupture of the membranes. This fluid should normally remain clear. If the fetus becomes hypoxic, meconium may be passed as hypoxia causes relaxation of the anal sphincter. The amniotic fluid becomes green as a result of meconium staining. Amniotic fluid that is a muddy yellow colour or is only slightly green may signify a previous event from which the fetus has recovered, but is common and may be of no significance in post-dates babies.

If the breech is presenting and is compacted in the pelvis, the fetus may pass frank thick meconium because of the compression of the abdomen; a fetus presenting by the breech is also prone to fetal compromise and may pass meconium as a result of hypoxia.

In the rare case of a fetus that is severely affected by Rhesus isoimmunization, the amniotic fluid may be golden-yellow owing to an excess of bilirubin.

Bleeding of sudden onset at the time of rupture of the membranes may be the result of ruptured vasa praevia and is an acute emergency (see Ch. 33).

Fetal compromise

‘Fetal distress’ is a term that should no longer be used; suspected fetal compromise should be favoured. If the fetus suffers as a result of an intrapartum event resulting in oxygen deprivation then the following signs may be present:

Midwife’s management of fetal compromise

If signs of suspected fetal compromise are apparent, a midwife must call an appropriately trained obstetrician. If oxytocin is being administered, it should be stopped and the woman placed in a favourable position, usually on her left side. In cases of maternal oxygen lack, such as eclampsia or shock due to antepartum haemorrhage, oxygen may be given via a face mask. Prolonged oxygen administration will not benefit the fetus. The doctor may wish to take a sample of fetal blood for testing and arrangements should be made for this or delivery will be expedited depending on the clinical situation. In the first stage of labour this will necessitate caesarean section. In the second stage of labour a forceps delivery or ventouse extraction may be performed. When it is necessary to expedite delivery, the presence of a neonatologist or appropriately qualified health professional is desirable (NMC 2004).

Pre-term labour

Pre-term labour (for causes of this, see Ch. 42) is defined as labour occurring before the 37th completed week of pregnancy, regardless of birth weight (WHO 1969). A fetus is legally viable from 24 weeks’ gestation. If a fetus is expelled from the uterus prior to 24 weeks and shows no sign of life, it is classified in the UK as a miscarriage (abortion). The World Health Organization recommends recording all deliveries of >500 g birth weight.

Pre-term labour is associated with significant long-term disability and morbidity. After 29–30 weeks’ gestation, the birth weight is a good predictor of survival. Prior to 29 weeks’ gestation, the birth weight, gender, multiple pregnancy and gestation are all considered in the equation of risks of morbidity and mortality. The incidence of pre-term birth is increasing, but currently stands at around 8%, although with wide racial differences (Atalla et al 2000, p 113).

Increased perinatal survival, which is attributed to increased neonatal intensive care facilities and appropriately trained personnel, has altered policies towards management of the woman in pre-term labour. A woman who is at risk of delivering prematurely should be transferred to a maternity unit with intensive neonatal facilities, preferably with the fetus in utero. Tocolytic drugs may be used in very early labour to delay delivery until transfer to such a unit. Antenatal administration of corticosteroids has been shown to reduce the incidence of hyaline membrane disease, intraventricular haemorrhage and necrotizing enterocolitis in fetuses of 26–34 weeks’ gestation. Two doses given over 24 hrs last for at least 7 days.

The 8th Annual CESDI (2001) report on the project of 27/28 week-gestation babies states that 88% of these survive – almost double that of 15 years previously.

Management of pre-term labour

The gestation of the pregnancy in pre-term labour influences the management. Generally, the earlier the gestational age the higher is the possibility of an infective cause, which is often followed by rapid labour and delivery. Caesarean section of cephalic pre-term infants offers no reduction in fetal morbidity or trauma and is associated with its own morbidity. It is generally accepted that the mode of delivery of gestations <26 weeks does not alter the outcome. Prolonging pregnancies beyond 34 weeks does not improve neonatal outcomes, therefore in practice no attempt is usually made to arrest labour if pregnancy has advanced to 34 weeks’ gestation.

Skilled care is required for the woman and the fetus during labour. The mother is faced with an unexpected emotional crisis because of the interruption of the normal progress of pregnancy. In extreme prematurity (22–25 weeks), a high perinatal mortality rate means the woman and her partner have to face the possibility of the death or disability of their baby. Full discussion regarding possible outcomes and whether or not to attempt resuscitation should be carried out with the senior clinicians involved in the care, and of course the parents. Continuous electronic heart rate monitoring is difficult to interpret at <30 weeks’ gestation and should therefore be used and interpreted with caution. Baseline variability may be reduced on the CTG.

Records

Midwives are subject to statutory supervision and the Midwives Rules. The Nursing and Midwifery Council has set out how midwives’ records should be kept, stored, handled and supervised. Rule 9 of the Midwives Rules and Standards (NMC 2004) sets out stipulations in relation to the keeping of midwifery records. Rule 10 requires midwives to permit the inspection of their records by the supervisor, the local supervising authority and the NMC (Dimond 2005). The content of these records should pertain to both the woman’s physical and psychological condition and the condition of her fetus (see Ch. 25). Records must be legible in ink that can be reliably photocopied; they must also be dated and signed. The purpose of records is to serve the interest of the woman, to demonstrate the chronology of events as well as all significant consultations, assessments, observations, decisions, interventions and outcomes.

A written individualized care plan should be recorded in labour following examination and consultation with the woman. This should attempt to fit nicely with the birth plan that was devised in pregnancy and address anything that has changed. If the woman changes her mind as her labour progresses, or the situation changes, adjustments can and sometimes must be made. Whether or not a formal birth plan has been prepared, the midwife who is with the woman should communicate effectively with her, evaluate whether the labour is proceeding as expected and listen to her requests. A comprehensive record of the discussions that take place about changes in the plan or about proposed measures will ensure that the closest possible attention is paid to achieving the outcome that the parents are hoping for and will also provide an excellent documented history of the labour and improve communication. The midwife must also record reasonable observations and examinations as contemporaneously as possible.

Box 26.1 lists best practice points for this stage of labour.

Atalla R, Kean L, McParland P. Preterm labour and prelabour rupture of fetal membranes. In: Kean L, Baker P, Edlestone D, editors. Best practice in labour ward management. London: W B Saunders; 2000:113-129.

Ball JA. Reactions to motherhood, 2nd edn. Hale: Books for Midwives Press, 1994.

Clements C. Amniotomy in spontaneous, uncomplicated labour at term. British Journal of Midwifery. 2001;9(10):629-634.

CESDI (Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy). 8th annual report. London: Maternal and Child Health Research Consortium, 2001.

COMET (Comparative Obstetric Mobile Epidural Trial) Study Group UK. Effect of low dose mobile versus traditional epidural techniques on mode of delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358(9275):19-23.

Crofts JF, Bartlett C, Ellis D, et al. Training for shoulder dystocia: a trial of simulation using low-fidelity and high-fidelity mannequins. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;108(6):1477-1485.

Dare MR, Middleton P, Crowther CA, et al. Planned early birth versus expectant management (waiting) for prelabour rupture of membranes at term (37 weeks or more). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 1, 2006.

de Jong PR, Johanson RB, Baxen P, et al. Randomised controlled trial comparing the upright and supine positions for second stage of labour. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;104:567-571.

Dimond B. Midwifery records and legal issues surrounding them. British Journal of Nursing. 2005;14(20):1076-1078.

Gee H. Abnormal patterns of labour and prolonged labour. In: Kean LH, Baker P, Edleston DI, editors. Best practice in labour ward management. W B Saunders; 2000:London.

Gibb D. A practical guide to labour management. Blackwell Scientific: Oxford, 1988.

Hodnett ED. Caregiver support for women during childbirth. The Cochrane Library, Issue 3. Update Software, Oxford, 2001.

Hodnett ED, Osborn RW. Effects of continuous intrapartum professional support on childbirth outcomes. Research in Nursing and Health. 1989;12:289-297.

Hodnett ED, Osborn RW. A randomized trial of the effects of support during labour: mothers’ views two to four weeks postpartum. Birth. 1989;16(4):177-183.

Hofmeyr G, Kulier R. Hands/knees posture in late pregnancy or labour for fetal malposition (lateral or posterior). The Cochrane Library, Issue 3. Update Software, Oxford, 2001.

Hunter LP. Women give birth and pizzas are delivered: language and Western childbirth paradigms. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2006;51(2):119-124.

Johnson C, Keirse MJNC, Enkin M, et al. Nutrition and hydration in labour. In: Chalmers I, Enkin M, Keirse MJNC, editors. Effective care in pregnancy and childbirth. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1989:827-832.

Kenyon SL, Taylor DJ, Tarnow-Mordi W, et al. Broad-spectrum antibiotics for preterm, prelabour rupture of fetal membranes: the ORACLE I randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357(9261):979-988.

Langer A, Campero L, Garcia C, et al. Effects of psychosocial support during labour and childbirth on breastfeeding, medical interventions, and mothers’ wellbeing in a Mexican public hospital: a randomised clinical trial. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;105(10):1056-1063.

Lewis G, editor. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer 2003–2005. The 7th report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. London: CEMACH, 2007.

Lovell A. Power and choice in birthgiving: some thoughts. British Journal of Midwifery. 1996;4(5):268-272.

Lowe NK, Reiss R. Parturition and fetal adaptation. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecological and Neonatal Nursing. 1996;25(4):339-349.

Madi BC, Sandall J, Bennett R, et al. Effects of female relative support in labour: a randomized controlled trial. Birth. 1999;26(1):4-8.

NICE (National Institute for Clinical Excellence). Clinical guideline No. 70. London: Induction of labour. RCOG Press, 2008.

NICE (National Institute for Clinical Excellence). The use of electronic fetal monitoring: the use and interpretation of cardiotocography in intrapartum fetal surveillance. London: NICE, 2001.

Niven C. Psychological care for families: before, during and after birth. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1992.

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council). Midwives rules and standards. London: NMC, 2004.

Nolan M. Vaginal examinations in labour: expert view. Practising Midwife. 2001;4(6):22.

Parkes J, Dolk H, Hill N, et al. Cerebral palsy in Northern Ireland: 1981–1993. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2001;15(3):278-286.

Price S, Noseworthy J, Thornton J. Women’s experience with social presence during childbirth. American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2007;32(3):184-191.

RCOG/RCM (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists/Royal Colleges of Midwives). Towards safer childbirth. London: RCOG/RCM, 1999.

RCOG. Guideline No. 44 Preterm prelabour rupture of membranes. London: RCOG, 2006.

Re F, (Mental Patient:Sterilisation). 2 AC 1, 1990.

Roberts CC, Ludka LM. Food for thought. Childbirth Instructor Magazine Spring. 1994:25-29.

Sinivaara M, Suominen T, Routasolo P, et al. How delivery ward staff exercise power over women in communication. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;46(1):33-41.

Steele R. Midwifery care during the first stage of labour. In: Alexander J, Levy V, Roch S, editors. Aspects of midwifery practice: a research-based approach. Hampshire: Macmillan, 1995. Ch. 2

Sullivan A, McCormick C. Liu D, editor. Labour ward manual, Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, 2007;19-22.

Sutton J, Scott P. Understanding and teaching optimal foetal positioning. New Zealand: Birth concepts, 1995;11.

WHO (World Health Organization). Prevention of perinatal morbidity and mortality. Public Health Papers No. 42. WHO, Geneva, 1969.