Chapter 30 Prolonged pregnancy and disorders of uterine action

While the decision to intervene in a pregnancy that continues beyond term is based on discussion between the woman and obstetrician, the unique relationship between the woman and midwife is pivotal in enabling the woman to make an informed decision at this time. The midwife continues to play a key role when labour is induced, when there is failure to progress in labour or when labour is prolonged, with or without further complications.

Prolonged pregnancy

Prolonged pregnancy and post-term pregnancy are used synonymously and refer to a specific gestation of the pregnancy and not the fetus or neonate. The term, prolonged pregnancy, will be used in this chapter. Post-maturity refers to a description of the neonate with peeling of the epidermis, long nails, an alert face and loose skin suggestive of recent weight loss (Koklanaris & Tropper 2006). The relationship, if any, between prolonged pregnancy and post-maturity will be explored later in the chapter.

Prolonged pregnancy is associated with increased risk to the fetus and neonate resulting in higher perinatal morbidity and mortality (Briscoe et al 2005, Fok et al 2006, Gülmezoglu et al 2006, RCOG 2001). It is the most common indication given for induction of labour in England accounting for approximately 46% of inductions overall. In 2004–2005, 79% of cases of prolonged pregnancy were induced (Department of Health (DH) 2006). While it is accepted there is evidence of an increase in perinatal mortality and morbidity as the pregnancy goes beyond 41 weeks, this would appear to relate to studies in white women. The racial differences with regards to length of gestation in South Asian and Black women that Balchin et al (2007) highlight must also be considered with regards to a definition of prolonged pregnancy to improve perinatal outcome in these groups.

Definition

The definition of a prolonged pregnancy commonly cited by many authors (Balchin et al 2007, de Miranda et al 2006, Laursen et al 2004) is that taken from WHO (1977) as a pregnancy equal to or more than 42 completed weeks (294 days from the first day of the last menstrual period, LMP). This has become the standard definition of prolonged pregnancy and recognized internationally (Hovi et al 2006, Koklanaris & Tropper 2006, Mogren et al 1999). However, the RCOG in their guideline on induction of labour use a definition of ‘those pregnancies continuing past 287 days (41 weeks) from the first day of the last menstrual period’ (RCOG 2001, p 15).

The expected date of delivery (EDD) is calculated on the basis of Naegele’s rule, the assumption being that the cycle is 28 days and that ovulation occurs on the 14th day (see Ch. 17). It is clear however, that making this assessment based on the LMP is to consider women as a homogenous group with regards to their menstrual cycle. Balchin et al (2007) suggest that defining a pregnancy as prolonged on the basis of the LMP is an ‘epidemiological concept’ and highlights the racial variations with shorter gestational age in South Asian and Black women. This concept is supported by Laursen et al (2004) who put forward the notion of prolonged pregnancy as ‘a normal variation of human gestation’. Only a small proportion of prolonged pregnancies result in babies that are postmature as described above (Hovi et al 2006). We live in a multicultural society and given the perceived risks of prolonged pregnancy, this would appear to highlight the need for further studies in different racial groups to determine a more accurate definition in such groups of women. Accurately defining prolonged pregnancy is important if the woman is to be advised appropriately regarding the possible risks, the options for the birth and to avoid unnecessary intervention in an otherwise ‘low risk’ pregnancy.

Incidence

The frequency or incidence of prolonged pregnancy is quoted as anything from 5–10% (Briscoe et al 2005, Cardozo et al 1986, Hannah et al 1992, Hovi et al 2006). In 2004–2005 the incidence in England is given as 4% (DH 2006). Based on a definition of 42 weeks, a true incidence of prolonged pregnancy is difficult to assess because in many cases women are induced before reaching that time for specific complications in the pregnancy, for maternal request or because the pregnancy has gone beyond the EDD. Cardozo et al (1986) suggest there might be three sub-groups related to a prolonged pregnancy, which include those where the dates are incorrect, those with a normal prolonged gestation where physiological maturity is achieved after 42 weeks and those with correct dates, are functionally mature but who do not go into labour at term. A number of authors support the use of an early ultrasound scan to date the pregnancy more accurately particularly if there is any uncertainty with LMP in order to reduce the number of pregnancies categorized as prolonged (Balchin 2007, Briscoe et al 2005, Hovi et al 2006, NICE 2008a).When an early ultrasound scan is used the incidence is reduced from 10% to 3% (Hovi et al 2006).

Associated risks and implication for mother, fetus and baby

The risks with any perceived complication of pregnancy need to be viewed from the perspectives of the mother, the fetus and the neonate with regards to morbidity and mortality. The associated risks for the mother are associated with a large for gestational age or macrosomic infant such as shoulder dystocia, genital tract trauma, postpartum haemorrhage and operative birth. The macrosomic infant is at risk of bony injury, soft tissue trauma, hypoxia, and cerebral haemorrhage. However, in prolonged pregnancy, risk of neonatal morbidity and mortality are more commonly associated with the opposite in terms of growth, i.e. the small for gestational age baby suffering hypoxia, asphyxia, meconium aspiration and stillbirth.

The risks outlined for the fetus and neonate appears to be linked to a reduced liquor volume (oligohydramnios). A number of authors suggest placental insufficiency or placental dysfunction as a contributory factor to fetal problems based on the notion that if the pregnancy is prolonged the placenta is ageing and thus the pregnancy has outgrown placental function (Dasari et al 2007, Hovi et al 2006). Fox (1997) argues that the changes in the placenta over the course of pregnancy are part of a process of maturation and an increase in functional efficiency as opposed to a process of ageing and decrease in functional efficiency. Given that few post-term babies exhibit signs of postmaturity possible changes in placental function might be more appropriately linked to pregnancies where there is evidence of postmaturity in the neonate rather than in prolonged pregnancies per se (Koklanaris & Tropper 2006).

In prolonged pregnancy, much of the discussion on the associated risks is focused on fetal and neonatal well-being and the need to reduce perinatal mortality and morbidity with appropriate management. The possible risk to mother, fetus and neonate associated with induction of labour for prolonged pregnancy, particularly where the cervix is unfavourable must also be considered in an otherwise uncomplicated pregnancy.

Predisposing factors

Factors that might predispose a woman to a prolonged pregnancy include nulliparity, previous prolonged pregnancy, male fetus, pre-pregnancy BMI of 25 kg/m2 or more, anencephaly (Koklanaris & Tropper 2006, Laursen et al 2004, Mogren et al 1999, Neff 2004, Olesen et al 2006). Laursen et al (2004) demonstrate a lower perinatal mortality rate in prolonged pregnancies where the mother has had a previous prolonged pregnancy suggesting a possible genetic influence with a prolonged gestation as a normal variation on human gestation.

Management of prolonged pregnancy

The purpose in determining the most appropriate management is to ensure the optimum outcome for mother and baby. In a prolonged pregnancy where there are any obstetric or medical complications the priority in management should follow the practice for the specific complication. All things being equal the management can follow an active or expectant approach and the decision on which approach to take should be based on the woman and partner receiving the information on the possible benefits and risks of each so that an informed choice can be made. Any management must include an accurate dating of the pregnancy to determine the pregnancy is prolonged for that individual.

The expectant approach involves increased antenatal surveillance including a non-stress test (NST) and ultrasound estimation of amniotic fluid volume (AFV) using either amniotic fluid index (AFI) or maximum vertical pocket (MVP) as the criteria to assess fetal wellbeing (Dasari et al 2007, NICE 2008a). The NST involves a cardiotocograph (CTG) to monitor the fetal heart rate with the expectation of two accelerations of ≥15 beats for ≥ 15 s above the baseline in a 20-min period. Fetal movements may also be noted on the CTG. Because of difference in the fetal sleep–wake cycle if there are no accelerations seen in that time the CTG is continued for a further 20 min. If no accelerations are seen in the 40-min period (non-reactive trace), or if there are any other irregularities in the CTG the management is reviewed. Measurement of AFV is undertaken to identify cases where there is oligohydramnios because of the association between a reduced liquor volume, intrapartum fetal heart rate decelerations and meconium stained liquor. Other options for monitoring fetal well-being antenatally include a biophysical profile (AFV, fetal breathing movements, fetal movements, fetal tone and NST), contraction stress testing and Doppler velocimetry. There is little or no evidence to support the efficacy of this type of surveillance over those mentioned previously. The suggested frequency of antenatal surveillance is two to three times a week (Hannah et al 1992, Neff 2004, RCOG 2001).

The use of a membrane sweep at 41 weeks’ gestation has been seen to significantly increase the spontaneous onset of labour before 42 weeks (de Miranda et al 2006). The purpose of membrane sweeping is to attempt to initiate the onset of labour physiologically, thus avoiding induction for prolonged pregnancy using prostaglandin, ARM and oxytocin. Sweeping of the membranes is designed to separate the membranes from their cervical attachment by introducing the examining fingers into the cervical os and passing them circumferentially around the cervix. The process of detaching the membranes from the decidua results in the release of local prostaglandin that may contribute to the initiation of the onset of labour in some individuals. Massage of the cervix can be used when the cervical os remains closed and this process may also cause release of local prostaglandin. If after an appropriate time labour has not started spontaneously, the process can be repeated. The practice of sweeping the membranes is not associated with any increase in maternal or neonatal infection (NICE 2008a), or pre-labour rupture of membranes (Boulvain et al 2005, Wong et al 2002), although women report more vaginal blood loss and painful contractions in the 24 hrs period following the procedure.

The active approach involves induction of labour (IOL) at 41 or 42 completed weeks (Briscoe et al 2005, Koklanaris & Tropper 2006, Neff 2004, NICE 2008b, RCOG 2001). The RCOG recommend IOL to women with uncomplicated pregnancies beyond 41 weeks, stating that where routine induction is undertaken after 41 weeks, there is evidence of a reduction in perinatal mortality. Heimstad et al (2007) compared IOL at 41 weeks’ gestation with expectant management and found no difference between the two groups with regard to neonatal morbidity or mode of birth. Alexander et al (2000) suggest that intervention at 41 weeks’ gestation cannot be justified based on a lack of proven benefit and an increased likelihood of intrapartum complications and Menticoglou and Hall (2002) argue that ‘ritual induction’ at 41 weeks is based on flawed evidence and interferes with a ‘normal physiologic situation’.

The midwife’s role

The mechanisms leading to the onset of labour remain largely unknown and the possibility of a prolonged pregnancy being a variation on human gestation within normal parameters should be considered. The debate on the management of prolonged pregnancy centres on the disparate evidence with regards to fetal risk and neonatal outcome in terms of perinatal mortality and morbidity and the management is designed to reduce these risks. The potential risks to the mother of a prolonged pregnancy, often relate to complications that arise where the baby is macrosomic. However, the interventions necessary when labour is induced also pose a potential risk to mother, fetus and neonate. The woman and her partner should be fully informed of the risks and benefits of any management to enable her to make an informed choice. While the obstetrician will take the lead in such cases the midwife has a role in facilitating the woman’s right to autonomy by ensuring she fully understands the options available to her and in appropriate cases acting as the woman’s advocate. See Box 30.1 for a summary of the key points relating to prolonged pregnancy.

Box 30.1 Key points about prolonged pregnancy

Induction of labour

The induction of labour (IOL) rate in the National Health Service (NHS) in England is 20% and this rate has been slowly rising since 1993 (DH 2006) making it an intervention that has become common practice in maternity units within the NHS.

IOL is an intervention to initiate the process of labour by artificial means and is the term used when initiating this process in pregnancies from 24 weeks’ gestation, which is the legal definition of fetal viability in the UK (RCOG 2001). Where labour is being induced, a full assessment must be made to ensure that any intervention planned will confer more benefit than risk for the mother and her baby. The decision to induce labour should only be made when it is clear that a vaginal birth is the most appropriate mode of delivery in this pregnancy, for that particular woman and her baby (NICE 2008b, RCOG 2001).

Indication for induction of labour

Induction of labour is considered when the maternal or fetal condition suggests that a better outcome will be achieved by intervening in the pregnancy than by allowing it to continue. This most commonly applies to cases where there are deviations from the normal physiological processes of childbirth as a result of maternal problems for example hypertension or diabetes, or fetal problems such as fetal growth restriction or macrosomia. A list of some of the indications for IOL can be seen in Box 30.2. The mother may also request to have labour induced for social reasons (NICE 2008b, RCOG 2001). However, the grounds on which the decision is made to induce labour must be sound enough to support the outcome whatever that outcome might be. There is no guarantee an IOL will result in a vaginal birth.

Box 30.2 Indications for induction of labour

Maternal

Fetal

The list in Box 30.2 is not considered to be definitive or conclusive and there may be other indications where IOL is recommended.

The contraindications for IOL are situations that would preclude a vaginal birth in the best interests of the mother and/or baby (Chamberlain & Zander 1999), such as:

Methods of induction

During pregnancy the cervix must remain strong and unyielding to the pressure of the gravid uterus to retain the fetus until it has reached maturity. For an induction to be successful, the cervix needs to have undergone the changes that will ensure the uterine contractions are effective in the progressive dilatation and effacement of the cervix, descent of the presenting part and the birth of the baby.

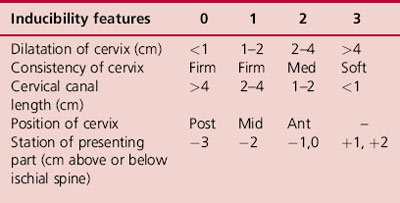

The cervix is said to be ripe when it has undergone the changes described in Chs 14 and 25. Assessing the ripeness of the cervix is by means of a scoring system devised by Bishop in 1964 (Bishop’s score) that examines four features of the cervix and the relationship of the presenting part to the ischial spines. Each of these five elements is scored between 0 and 3 on vaginal examination (VE). A score of 8 or more equates to a ripe cervix and one that is favourable for the purpose of IOL in that it is more compliant offering less resistance as the contraction and retraction of the myometrium forces the presenting part down. The scoring system has been modified and it is this version that is used in contemporary obstetric practice (Table 30.1). A VE to assess the cervix and the likelihood of successful induction in this way is by nature a subjective examination and as such there will be inter-observer variations. Elghorori et al (2006) undertook a prospective study to compare subjective and objective assessment of the cervix before IOL and found a transvaginal ultrasound assessment of cervical length was superior to the Bishop’s score in predicting the success of IOL. Future research in this area of practice will be interesting to follow particularly with regard to preference and acceptability from the woman’s perspective.

Prior to any method used to induce labour, it is extremely important for the midwife to carry out an abdominal examination confirming the lie, presentation, descent of presenting part and fetal well-being. All findings are clearly recorded in the woman’s maternity records and if there is any doubt or concern in the findings the process should be stopped and the doctor informed (NMC 2004).

Membrane sweep

A membrane sweep after 40 weeks carried out by a doctor or midwife experienced in the practice has been found to reduce the need for further methods to induce labour (Boulvain et al 2005, Chamberlain & Zander 1999). Wong et al (2002) found that while the procedure was safe in that it did not lead to pre-labour rupture of membranes, bleeding or maternal or neonatal infection it did cause significant discomfort and in their study was not found to reduce the need for IOL. NICE (2008b) recommend sweeping of the membranes prior to formal induction procedures at 40+ weeks’ gestation or earlier where there are pregnancy complications, if the woman’s clinical condition allows for this. However, a review by Boulvain et al (2005) suggests the possible benefits in terms of a reduction in more formal induction methods needs to be weighed against the discomfort of the VE and other adverse effects of bleeding and irregular contractions not leading to labour.

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) (Dinoprostone)

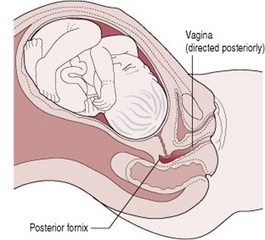

Prostaglandins are naturally occurring female hormones present in tissues throughout the body. Prostaglandin E2 and F2 are known to be produced by tissues of the cervix, uterus, decidua and the fetal membranes and to act locally on these structures. Dinoprostone is the active ingredient in Prostin E2 vaginal tablets, gel, and pessaries (BNF 2007). It replicates prostaglandin E2 produced by the uterus in early labour to ripen the cervix and is seen as a more natural method than the use of oxytocin. Prostin E2 placed in the posterior fornix of the vagina (Fig. 30.1) is absorbed by the epithelium of the vagina and cervix leading to relaxation and dilatation of the muscle of the cervix and subsequent contraction of uterine muscle. The use of Prostin prior to the use of oxytocin potentiates the effects of the oxytocic agent (Chamberlain & Zander 1999).

Figure 30.1 Insertion of prostaglandins. The posterior fornix of the vagina is used to insert prostaglandins for ripening or induction of labour. The key point is that when undertaking a vaginal examination to assess the cervix midwives should follow the direction of the vagina which will be directed posteriorly if the woman is semi-recumbent. The uterus is anteverted and anteflexed, creating the posterior fornix. The cervix may appear ‘difficult to reach’ particularly when unfavourable.

There are a number of preparations of PGE2, which have been found to be clinically equivalent. In a small study by Tomlinson et al (2001) the women receiving the slow release pessary gave a higher satisfaction score with regards to their perception of labour. The slow release preparation would appear to confer more benefit from the woman’s perspective with regard to fewer VEs. The cost of PGE2 preparations may vary over time and NICE (2008b) expect cost to be taken into consideration when prescribing a gel, tablet or pessary. It must be remembered that these PGE2 preparations are not bioequivalent.

Following insertion of PGE2, the woman is advised to lie down for 30 min. The fetal heart rate and uterine activity are continuously monitored by CTG to determine fetal well-being. If the trace is found to be reassuring the CTG can be discontinued and intermittent monitoring used. If there are no risk factors such as maternal hypertension, previous caesarean section, fetal growth restriction, etc. the initial process can take place on the antenatal ward with facilities for continuous electronic fetal monitoring (NICE 2008b, RCOG 2001) and appropriate staffing levels. Prior to the administration of the Prostin the midwife should confirm with the midwife in charge of the labour suite that a bed is available in the event there is a need to transfer the woman as a matter of urgency. For the safety of the woman and her baby any decision to proceed with IOL must take cognizance of the current situation on the labour suite because the woman’s response to insertion of PGE2 cannot be predicted. If there are any maternal or fetal risk factors in the pregnancy the IOL must take place on the labour suite (NICE 2008b, RCOG 2001).

Where the membranes are intact or ruptured, the recommended initial dose for all women whether it is a first or subsequent pregnancy is PGE2 3 mg tablet. If the woman has not gone into labour, a further assessment is carried out 6 hrs later and if the cervix remains unfavourable, a further 3 mg tablet is inserted into the posterior fornix the maximum recommended dose of a PGE2 tablet being 6 mg (RCOG 2001). If PGE2 gel is being used, the dosage will depend on parity and Bishop’s score. The gel can be given as 1 or 2 mg and the maximum recommended dosage is 4 mg. A review by Kelly et al (2003) suggests that the ‘low doses were as effective as higher doses’. However, Selo-Ojeme et al (2007) found that despite having an induction of labour protocol that was said to be in accordance with NICE guidelines a high percentage of units do not comply with these recommendations and exceed the maximum doses particularly when using PGE2 tablets as opposed to PGE2 gel. The advice from NICE in cases where the maximum dose has been given but amniotomy is still not possible is for the clinician to use their professional judgement with regard to administering further doses. It is not clear what the legal implications would be if there were complications and the manufacturer’s recommendations had been exceeded (Selo-Ojeme et al 2007). There should be a break of no less than 6 hrs from the last PGE2 to commencement of an oxytocin infusion. Side effects of Prostin include nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea (BNF 2007).

PGE1 (misoprostol) can be given by the oral, sublingual, or vaginal route for IOL but it is not licensed for this purpose in the UK. It is thought the sublingual route might replicate the vaginal route with regards to bioavailability because it avoids first pass effect that occurs when the drug is taken orally. The dosage of tablets currently available is 200 μg and for use in IOL a much smaller dose would need to be available (Shetty et al 2003, Shetty et al 2002). Misoprostol is thought to be more effective and less expensive than PGE2 and oxytocin for the induction of labour but there are still questions about safety issues with regard to uterine hyperstimulation. More work needs to be done to study the efficacy of these alternative routes.

Risk associated with use of PGE2

The use of PGE2 can be unpredictable and may lead to hypertonic uterus, placental abruption, fetal hypoxia, pulmonary or amniotic fluid embolism (Kramer et al 2006). While uterine rupture is rare, occurring between 0.3% and 7% of labours there continues to be debate on the use of prostaglandins in women with a caesarean section scar and the possible effect of the prostaglandin on the fibrous tissue of the scar (Vause et al 1999).

Artificial rupture of membranes

ARM or amniotomy, can be used in an attempt to induce labour if the cervix is favourable and the presenting part is fixed in the pelvis particularly where the woman does not want to use drugs such as PGE2 or oxytocin. Prior to the procedure an abdominal examination is carried out and if the findings are satisfactory a VE is done to assess the cervix, confirm the presentation and station and to exclude possible cord presentation or vasa praevia. If these findings are satisfactory, the bag of membranes lying in front of the presenting part (forewaters) is ruptured with the use of an amniohook or similar device to release the amniotic fluid. The fluid is assessed for colour and volume and the midwife or doctor may be able to distinguish other features on the presenting part to identify the position of the fetus. After the procedure, the woman is made comfortable, the fetal heart is auscultated and all findings are recorded in the maternity notes. The longer the interval between ARM and birth increases the risk of the woman developing chorioamnionitis as a result of an ascending infection from the genital tract leading to an increased risk of perinatal mortality (Blackburn 2007). For this reason, if a decision has been made to induce labour for perceived risks it is common practice to start an oxytocin infusion within a few hours if labour has not been established following the ARM. In their review of two trials, Bricker and Luckas (2000) found insufficient evidence on the effects of amniotomy alone for the IOL.

Changes to ripen the cervix are thought to be in response to PGE2 produced by the amnion and cervix. In pregnancy, the chorion provides a barrier to the amnion and fetus from the vagina and cervix. Prostaglandin dehydrogenase (PGDH) is an enzyme produced by the chorion that breaks down PGE2. As a result of the actions of this enzyme the changes in the cervix do not take place and pre-term labour is avoided (Smyth et al 2007). Van Meir et al (1997) found that in labouring women the part of the chorion that was in close contact with the cervical os released less of this enzyme allowing the PGE2 from the amnion to come into contact with the cervix and facilitate ripening of the cervix. The theory is that if an ARM is performed too early the action of the amniotic prostaglandins on the cervix is lost.

Oxytocin

Oxytocin is synthesized in the hypothalamus and then transported to the posterior pituitary gland from where it is episodically released to act on smooth muscle. The number of oxytocin receptors in the myometrium significantly increases by term increasing uterine oxytocin sensitivity (Blackburn 2007).

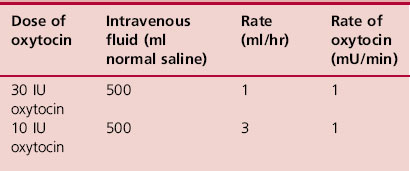

In its synthetic form oxytocin (Syntocinon) is a powerful uterotonic agent and when used for induction of labour following ARM should be administered by slow intravenous infusion using an infusion pump or syringe driver with non-return valve (BNF 2007, NICE 2001, RCOG 2001). In order to reduce the risk of clinician error, the RCOG (2001) recommend the use of a standardized dilution of oxytocin in 500 mL of normal saline (Table 30.2). There should be an interval of 6 hrs between administration of prostaglandins and commencement of an oxytocin infusion and if the membranes have not previously ruptured an amniotomy should be performed. The dose of oxytocin is titrated against uterine contractions to achieve three to four contractions every 10 min lasting 40 s or more using the lowest possible dose. The contraction rate each 10 min should not exceed this number.

When using an oxytocin infusion, the fetal heart and uterine activity should be monitored using continuous electronic monitoring to ensure the fetus does not become compromised by the induced uterine contractions. The intended outcome is to achieve three to four contractions every 10 min but there is a risk of hyperstimulation and hypertonic uterus leading to fetal compromise. In this event, the infusion should be decreased or discontinued and medical aid summoned. The midwife should also palpate the uterine contractions for their frequency, strength, and duration as well as using electronic monitoring.

The midwife’s role when caring for the mother where labour is being induced

The midwife’s responsibilities to the mother include care during the antenatal and intrapartum period. Where a decision has been made to induce labour, it is important the midwife ensures the woman and her partner have been fully informed and understand the process and how it might be undertaken. There are a number of ways that labour can be induced and the method will depend on the individual circumstances of each woman. All information should be given in an objective manner to ensure the woman and her partner understand the reason for the induction, any possible consequences or risks of having/not having the procedure as well as any alternatives to the procedure (RCOG 2004). It is important for the woman and her partner to understand that IOL may be delayed if the labour suite is busy, that it might take some time for contractions to be initiated and the possibility that the induction process could be unsuccessful. Time should be allowed for discussion with the midwife or obstetrician and it must be remembered that consent to a treatment can be withdrawn at any time and this decision by the woman should be respected (Dimond 2006). The midwife or doctor should record any discussion that takes place and requests made in the maternity notes.

During the induction process all maternal and fetal observations will be recorded in the maternity notes. Until labour is established and the partogram is commenced, the observation will be recorded in the antenatal section of the notes. Because the layout is not as comprehensive and logical as the partogram it is important the midwife is clear and methodical in her documentation at this time. The frequency and type of monitoring of the mother and fetus will depend on the reason for and method of induction. The midwife is advised to follow the local protocol regarding IOL in each case. It is important when monitoring the well-being of the mother and fetus during the induction process that the midwife understands the possible risks associated with each method of induction so that she can make the necessary observations to recognize any deviations from normal, take whatever action is most appropriate and call medical aid.

Initiation of labour during the induction may be a protracted process and in such cases, the woman may have time to adjust to the changes in her body and be better able to cope with contractions. However, the sudden onset of strong painful contractions occurring every 3–4 min can be quite overwhelming and result in an early request for pain relief. Continuity of care by one midwife in labour is important in developing a rapport with the woman and her partner and in being able to make an assessment of her progress based on physical observations of abdominal examination and VE as well as less tangible observations of body language and behaviour. In this way, a midwife may be better able to advise a woman of her progress to help her in her decision on the type of pain relief. The suggested frequency of VEs will depend on the local policy but it must be remembered that valid consent must be obtained before all such procedures. When a woman is experiencing painful contractions in labour the information about any examinations or procedures that the midwife or doctor may wish to perform should be given between contractions (RCOG 2001).

Alternative approaches to initiating labour

For some women avoidance of any surgical or pharmacological intervention in an otherwise low-risk pregnancy is extremely important and they might seek advice from the midwife on this matter. Alternative approaches include the ingestion of castor oil, nipple stimulation, sexual intercourse, acupuncture and the use of homeopathic methods. The midwife must ensure that any advice given on alternative therapies is in line with the sphere of practice (NMC 2004). In their review, Kelly et al (2001) found there was insufficient research to demonstrate the efficacy of castor oil on cervical ripening or inducing labour.

Stimulation of the breast or more specifically the nipple appears to cause the release of endogenous oxytocin, the effect being to initiate a uterine response. In a review by Kavanagh et al (2005) stimulation of the breast either by massage or nipple stimulation ‘appears beneficial in relation to the number of women not in labour after 72 hrs, and reduced postpartum haemorrhage rates’. It appears to be less effective where the cervix is not ripe. Further studies are needed before it can be considered for use in high-risk groups.

Suggesting sexual intercourse as a method of initiating labour to women at or beyond term with uncomplicated pregnancies is based on a number of factors that it is thought might contribute to the induction process; the prostaglandin content in semen, the physical stimulation of the lower segment of the uterus by the act of intercourse, stimulation of the breast during the process of love-making and the release of endogenous oxytocin during maternal orgasm. In the review by Kavanagh et al (2001), the efficacy of sexual intercourse as a method to initiate labour could not be supported.

The review by Smith & Crowther (2004) looking at acupuncture for the induction of labour stated the need for well-designed trials on the subject, but on current evidence the use of acupuncture in the induction of labour had not been fully evaluated for safety and effectiveness. Harper et al (2006) acknowledge the need to conduct further studies in this area.

Caulophyllum is a homeopathic therapy commonly used to initiate labour, however in a review of trials by Smith (2003) there was not enough evidence to recommend homoeopathy as a method of induction.

Failure to progress and prolonged labour

Labour encompasses effective uterine contractions and cervical changes leading to progressive effacement and dilatation of the cervix, rotation of the fetus and descent of the presenting part, the birth of the baby and expulsion of the placenta and membranes and the control of bleeding. For many, this process starts spontaneously and continues that way without the need to intervene. For some however, either in the early or late stages of labour the process slows down and there is ‘failure to progress’ based on the rate of cervical dilatation/hour or the labour is ‘prolonged’ when it exceeds the number of hours considered to be normal for a nulliparous or multiparous woman. Dystocia is the term used for a difficult or slow labour and thus includes both failure to progress and prolonged labour (Albers 2001). When dystocia occurs the obstetrician needs to make a decision as to how the situation is best managed from this point onwards with appropriate consideration of all the facts in the context of the individual. Interventions to correct this problem included ARM or oxytocin or a combination of both. The means to augment labour in this way has become common practice in UK with as many as 50% of nulliparae receiving an oxytocin infusion in labour (Hayman 2004). If these means fail an instrumental or operative delivery may be the only course of action depending on the stage of labour reached. The caesarean section rate in England is currently 23% and over half of these are emergencies (DH 2006). Many of these will be for failure to progress or prolonged labour.

The greatest anxiety with prolonged labour is the risk of obstructed labour and uterine rupture and the subsequent maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality associated with that scenario. Other problems when labour is slow to progress or prolonged is the risk of infection with prolonged rupture of membranes, or postpartum haemorrhage as a result of an atonic uterus. It must also be remembered the interventions used to correct a dystocia such as amniotomy, oxytocin infusion, and instrumental or operative delivery are not risk free and therefore any decision to intervene must take account of the full clinical picture. Prolonged labour is not easily defined primarily because there is no consensus as to what constitutes a normal time limit for labour either in the latent or active part of the first stage or the passive or active part of the second stage. The WHO (1994) defines prolonged labour as one that exceeds 18 hrs in primiparous women.

Delay in the latent phase of labour

In the first stage of labour, the latent phase is the period when structural changes occur in the cervix and it becomes softer and shorter (from 3 cm to <0 .5 cm), its position is more central in relation to the presenting part and it dilates to 3 cm (Hayman 2004). The time for this to take place is given as 8–10 hrs based on the original work of Friedman in 1956 (cited El-Hamamy & Arulkumaran 2005, Hayman 2004, Neilson et al 2003,). If progress in this phase of labour is considered to be slow, the emphasis is on conservative management rather than intervention (Hayman 2004). During this time, the woman needs support and encouragement from those caring for her. The contractions may be painful but the perceived result of such painful contractions may be disappointing when hearing the cervix is 3 cm dilated after several hours. Also during this time, making sure there is adequate food and fluid intake not only helps to maintain energy levels but can also bring a sense of normality and comfort. It is important for the woman to rest at this time and not to feel that if she tries to sleep, the contractions will cease. Advice on how to relieve pain might include simple back massage, changes of position, a warm bath or some simple analgesia. Intervention such as an ARM at this stage can interfere with the action of amniotic prostaglandin on the cervix and be counterproductive (Smyth et al 2007).

Delay in the active phase of labour and the use of the partogram

The active phase is the period of time when the cervix dilates from 3 cm to 10 cm with rotation and descent of the presenting part. This part is possibly the most contentious because the expectation is that progress once labour is diagnosed is a cervical dilatation of 1 cm/hr. Albers (2001) suggests a limit of 0.3–0.5 cm/hr might be a more appropriate reflection of the progress of normal labour. The current NICE guideline on intrapartum care (2007) appears to support both perspectives, defining delay in the first stage as progress of <2 cm in 4 hrs in both nulliparous and parous women or slowing in progress in parous women. However, when delay is suspected, the advice is to undertake a VE 2 hrs later at which point progress is defined as more that 1 cm/hr. While the guideline suggests one must also consider descent and rotation of the presenting part, changes in contractions, etc. the emphasis nonetheless seems to remain with the rate of cervical dilatation per hour.

The partogram is a graphical representation of dilatation of the cervix against time with an alert line based on cervical dilatation of 1 cm/hr between 3 cm and 10 cm. When labour is confirmed, the cervical dilatation is plotted on this line. An action line parallel to the alert line is placed 2 or 4 hrs to the right to highlight slow progress and indicate the timing of intervention for failure to progress or prolonged labour. The time frame for the action line varies from unit to unit. The WHO recommends the use of a 4 hrs action line (Lavender et al 2006) and this is supported by NICE (2007). Intervention rates will clearly vary depending on where the action line is placed and these must be considered in the context of improvement to maternal or neonatal outcome. The partogram also provides information on other factors that are critical in making an appropriate assessment where progress is deemed to be deviating from the normal range. These include findings at VE with regard to the presentation, position and station enabling the assessor to determine if there is rotation and descent of the presenting part, and the degree of caput or moulding. Information is also provided from abdominal palpation in terms of the presenting part and fifths palpable to see how this correlates with the VE and the frequency, strength and length of contractions. While such information is helpful it is also very subjective. Continuity of carer over time should reduce the likelihood of inter-observer variations.

The influence of the three ‘Ps’ (passages, passenger, powers)

Dystocia can be as a result of ineffective uterine contractions, malposition of the fetus leading to a relative or absolute cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD), malpresentation, or any combination of these. These may result in poor progress during the active phase or a cessation of cervical dilatation following a period of normal dilatation (Hayman 2004). An understanding of the role played by the three ‘Ps’ will help in determining why there is a delay in progress in first or second stage of labour and what action might be taken.

In the developed world, the majority of women have grown up well nourished, fit and healthy and the passages the fetus must negotiate are unlikely to be seriously flawed, excluding possible trauma to the pelvis. However the impact of a full rectum, full bladder and fibroids cannot be ignored in causing a delay in the progress of labour. A malpresentation, such as shoulder, brow or face (mento-posterior), is one of the causes of poor progress or prolonged labour and this may occur as a result of a problem with the passage (see Ch. 31).

When the fetus is adopting an attitude where the head is deflexed or slightly extended and the occiput is posterior, the presenting diameters are larger and there will be a degree of asynclitism. This inevitably slows progress but does not necessarily mean progress is abnormal. This might be considered a relative cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD) because with effective uterine contractions the fetus might adopt a more flexed attitude; the fetal head is designed to mould and change the dimensions of the presenting part. On some occasions more time is needed to do this safely. Where there is an occipitoposterior position and epidural analgesia, Ferguson’s reflex is not effective which results in slowing the progress of labour down at this time. In some cases the head is just (normally) large and any decision to intervene at this point with oxytocin may increase strength and frequency of uterine contractions in such a way as to unduly force this process with inevitable fetal heart rate changes prompting further intervention. El Halta (1998) suggests that rupturing the membranes when the fetus is an occipitoposterior position may result in a sudden descent of the fetal skull resulting in a deep transverse arrest whereby the occipitofrontal diameter (11.5 cm) is caught on the bispinous diameter of the outlet (10–11 cm).

Although the uterus has prepared itself for the metabolic activity of labour, as labour continues the smooth muscle uses up its metabolic reserves and becomes tired. While some ketosis is considered normal in labour, there remains a need for additional supplies of energy if the uterus is to continue contracting effectively. Any change to the strength, length or frequency of contractions will affect progress and is indicative of inefficient uterine action.

When there are concerns about progress in labour, the midwife will inform the obstetrician so that an appropriate assessment can be made to identify the cause and decide on the best course of management. It is important that the woman and her partner are closely involved in any discussions at this time to enable informed consent to be given for any procedures to augment the labour such as artificial rupture of the membranes or an oxytocin infusion if the membranes are ruptured. When a decision has to be made on the next step in managing dystocia it is important that repeat examinations are done by the same person. A full assessment should take place to ensure the decision to augment labour is based on sound and accurate clinical findings.

The midwife’s role in caring for a woman in prolonged labour

A prolonged labour leads to increased levels of stress, anxiety and fatigue and increases the risk of infection, postpartum haemorrhage and emergency caesarean section (Svärdby et al 2006). Managing labour should start with appropriate antenatal education. Advice on suitable food and drink to eat in the early stages of labour to maintain energy levels, positions and activities to encourage a forward rotation where there is an occipitoposterior position are just some of the ways that might help to assist the woman in the normal progress of labour.

When the woman and her partner come into hospital, one-to-one care helps to create a sense of trust between the woman, the partner and the midwife but also allows for more accurate assessment over time by the midwife to enable her to suggest non-interventionist ways in which progress can be maintained if appropriate. An upright position might help to facilitate more effective contractions or an alternative position might help to improve pelvic diameters when the position of the baby is posterior. At this stage, it is also important to maintain hydration, to encourage voiding and to suggest non-pharmacological ways to relieve pain. Facilitating her autonomy by keeping the woman and her partner informed of her progress and the choices she has is important in helping her to feel in control and to reduce her anxiety. Raised adrenalin levels as a result of fear, anxiety or pain can impact negatively on uterine activity and slow progress in labour.

Accurate observations in labour are critical in assessing progress. Edmunds (1998, p 13) talks of the importance of the midwife preparing for, expecting and facilitating a normal birth ‘while discreetly providing for any contingency necessitating intercession’. Recognition and detection of abnormal progress in labour with appropriate clinical response will improve the outcome of labour for both mother and baby (Neilson et al 2003). An abdominal examination can provide vital information about the labour with regard to the lie, presentation, position and descent of presenting part as well as the length, strength and frequency of contractions whereby any change in the pattern of the contractions can be picked up. When comparing these findings with those from VE a more comprehensive picture of the progress of labour is achieved. On VE the midwife is assessing the presence and degree of moulding of the fetal skull, the presence and position of caput succedaneum in relation to sutures and fontanelles and the dilatation of the cervix noting any thickening and its application to the presenting part. Any changes to the colour of the liquor if the membranes have previously ruptured or to fetal heart rate will give some indication as to how the fetus is coping with the progress of labour.

When the decision to augment labour has been made the woman and her partner will need additional support from the midwife, as the interventions necessary for this process may be very different from the birth they had previously imagined. Psychological as well as physical support is important at this time, as the control of the birth of their baby now appears to be in the hands of a third party and this can lead to very negative feelings of the childbirth experience (Nystedt et al 2005, 2006).

The management of prolonged labour is a collaborative effort involving the woman and her partner, the midwife, obstetrician, and anaesthetist. The normal pattern of observations and care in labour apply and any deviations from normal are reported to the obstetrician. When an ARM has been done to augment labour an appropriate period of grace should be given for effective uterine contractions to resume before commencing an oxytocin infusion. There is no specific regime for the use of oxytocin to augment labour but it is common practice to use that given by the RCOG for the induction of labour (RCOG 2001). The uterus responds with increased sensitivity to the oxytocin infused as the cervix dilates and it may be necessary to reduce the rate as full dilatation is approached to avoid hyperstimulation of the uterus and the concomitant effects on mother and fetus. The timing of how long to continue with augmentation in the first stage of labour will depend on the individual situation and circumstances at that time. An assessment will be made 2–4 hrs after ARM or commencing oxytocin to ascertain the likelihood of a successful vaginal birth. If there is persistent poor progress in the active phase despite optimal contractions of four each 10 min lasting >40 s, and the woman is pain free, well hydrated and with an empty bladder it is unlikely that continuing with an oxytocin infusion will lead to a vaginal birth.

The decision to augment labour in multiparae or in women with prior caesarean section must be made by an experienced obstetrician because of the very real risk of hyperstimulation and uterine rupture. Additional time should be given between ARM and commencing an oxytocin infusion with careful assessment of uterine activity and fetal heart rate. When the obstetrician has excluded absolute CPD a low dose oxytocin infusion may be commenced until optimal contractions are established at which point the infusion may be discontinued (El-Hamamy & Arulkumaran 2005, Hayman 2004).

Delay in the second stage of labour

The second stage of labour can be divided into a passive (pelvic) phase and active (perineal) phase. Delay in this stage of labour may be due to malposition causing failure of the vertex to descend and rotate, ineffective contractions due to a prolonged first stage, large fetus and large vertex, or absence of the desire to push with epidural analgesia. Some of these situations may be rectified with the judicious use of an oxytocin infusion thus avoiding the need for an instrumental or operative delivery.

Time limits in second stage range from 30 min to 2 hrs for multiparae and 1–3 hrs for nulliparae but an understanding of the different phases as the head negotiates the birth canal can avoid the encouragement of premature bearing down efforts, which only serve to tire and demoralize the mother. The variation in time limits takes into consideration the impact of epidural analgesia on the desire to push in the second stage. An imposed time limit is felt by some to be unnecessary if both mother and fetus are doing well (Hayman 2004, Neilson et al 2003).

The active phase when the mother is bearing down is the most critical time. Providing there is obvious progress and mother and fetus are both in good condition intervention may not be necessary. NICE (2007) suggest there is delay if the length of active second stage is 2 hrs in nulliparous women and 1 hr for parous women. When a diagnosis of delay in the second stage has been made the case is referred to the obstetrician for review and assessment. The risk to both mother and fetus if the second stage is allowed to exceed normal time limits must be weighed against the risks of intervening with an instrumental or operative delivery. Where there is any indication that the mother or the fetus is compromised the birth must be expedited as soon as possible.

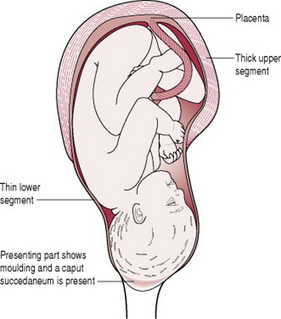

Obstructed labour

An obstructed labour occurs when despite good uterine contractions there is no advance of the presenting part. Possible causes of obstructed labour include absolute CPD, deep transverse arrest, malpresentation, lower segment fibroids, fetal hydrocephaly and multiple pregnancy with conjoined or locked twins. Because of the high presenting part if the woman goes into labour there may be spontaneous rupture of the membranes and cord prolapse with related risk to the fetus. If the condition is not recognized the mother’s uterus will continue to contract to overcome the obstruction. She will become progressively more dehydrated, ketotic, pyrexial, and tachycardic. The fetus will develop a bradycardia because of the relentless contractions. As the uterus continues to contract and retract the upper segment becomes progressively thicker closely enveloping the fetus and the lower segment becomes increasingly thinner. In nulliparous women the contractions may cease for a period before resuming again with increasing strength and frequency with little interval between contractions until the uterus assumes a state of tonic contraction. The difference between upper and lower segment may be seen as a ridge obliquely crossing the abdomen (Bandl’s ring). The mother is in severe and unrelenting pain. If VE is possible the presenting part will be high with excessive moulding (Fig. 30.2). The uterus is in imminent danger of rupture and emergency measures must be taken if the situation has been allowed to get this far. Uterine rupture leads to maternal mortality and the tonic contractions and uterine rupture cause hypoxia, asphyxia, and subsequent perinatal mortality (Neilson et al 2003).

Figure 30.2 Obstructed labour. The uterus is moulded around the fetus; the thickened upper segment is obvious on abdominal palpation.

If the woman has been discovered in this condition at home, a paramedic ambulance should be called for immediate transfer to hospital. Labour suite should be informed and they in turn will contact the senior obstetrician, anaesthetist, paediatrician, theatre staff, and special care baby unit. While waiting for the ambulance the midwife should cannulate, take blood for urgent cross match, and site an intravenous infusion. The woman’s GP can be called if close by to provide additional help and support until the ambulance arrives. Observations of mother and fetus and any actions taken and by whom are recorded in the maternity notes as soon as possible. If the obstruction is discovered in hospital an emergency caesarean section is performed.

Management of obstructed labour is about its prevention in the antenatal and intrapartum period. The midwife should highlight any predisposing factors antenatally with appropriate referral to the obstetrician so that a decision is made with the woman on the safest mode of birth. During labour skilled abdominal examination will alert the midwife to any malpresentation or failure of the presenting part to advance despite optimal uterine contractions. VE will confirm suspected malpresentation and where the presentation is vertex reveal increasing caput succedaneum or moulding. With a high presenting part in labour cervical dilatation will be extremely slow and there will be little if any application to the presenting part. The obstetrician is informed as soon as possible so that the birth can be expedited. If the labour is becoming obstructed in the first stage an emergency caesarean section will be carried out. If the delay occurs in the second stage as a result of deep transverse arrest the obstetrician may try to deliver the baby vaginally with ventouse but if that fails or is not possible an emergency caesarean is carried out. Despite the very real threat to maternal and perinatal well-being these procedures should only be undertaken with maternal consent.

Precipitate labour

In some women, the uterus is over-efficient and the onset of labour to birth is an hour or less. Much or all of the first stage is not recognized because contractions are not painful and the realization of the birth of the head may be the first indication that labour has actually started.

Such a precipitate birth is not without its problems leading to soft tissue trauma of the maternal genital tract due to sudden stretching and distension as the baby is born. Risks to the baby include: hypoxia as a result of the frequency and strength of the contractions, intracranial haemorrhage from the sudden compression and decompression of the fetal skull as it passes through the birth canal with speed, and possible injury as the head and body deliver rapidly and possibly fall to the floor. The unexpected nature of the event means that the place of birth may be inappropriate and the baby may be further compromised if the importance of maintaining the baby’s temperature is not recognized.The over-efficient uterus may relax after the birth of the baby resulting in retained placenta and/or postpartum haemorrhage. The psychological impact of such a rapid birth must not be underestimated and some women will be in a state of shock after the event.

Precipitate labour will often recur in subsequent pregnancies and the obstetrician may advise induction of labour once term (37 completed weeks) is reached.

The views of midwives and doctors on childbirth are often considered to be diametrically opposite, with midwives looking on childbirth as normal until proved otherwise and obstetricians viewing it as normal retrospectively. El-Hamamy & Arulkumaran (2005) consider every labour a trial of labour. Whatever the perspective taken the primary outcome is the safety of the mother and baby. Childbearing is a time of major life transition and each woman and partner deserve to have a positive birth experience whether labour is spontaneous or induced and the birth is vaginal or by caesarean section. Working together as a team can only help to contribute to that positive birth experience.

Albers L. Rethinking dystocia: patience please. MIDIRS Midwifery Digest. 2001;11(3):351-353.

Alexander JM, McIntire D, Leveno KJ. Forty weeks and beyond: pregnancy outcomes by week of gestation. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;96(2):291-294.

Balchin I, Whittaker C, Patel R, et al. Racial variation in the association between gestational age and perinatal mortality: prospective study. British Medical Journal. 2007;334:833.

Blackburn S. Maternal, fetal, and neonatal physiology: a clinical perspective, 3rd edn. Philadelphia: W B Saunders, 2007.

BNF. British National Formulary, BNF 53. 2007. Online. Available http://www.bnf.org.

Boulvain M, Stan C, Irion O. Membrane sweeping for induction of labour. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2005. CD000451

Bricker L, Luckas M. Amniotomy alone for induction of labour. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2000. CD002862

Briscoe D, Nguyen H, Mencer M, et al. Management of pregnancy beyond 40 weeks’ gestation. American Family Physician. 2005;71(10):1935-1941.

Cardozo L, Fysh J, Pearce JM. Prolonged pregnancy: the management debate. British Medical Journal. 1986;293:1059-1063.

Chamberlain G, Zander L. ABC of labour care: Induction. British Medical Journal. 1999;318(7189):995-998.

Dasari P, Niveditta G, Raghavan S. The maximal vertical pocket and amniotic fluid index in predicting fetal distress in prolonged pregnancy. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2007;96(2):89-93.

de Miranda E, van der Bom JG, Bonsel GJ, et al. Membrane sweeping and prevention of post-term pregnancy in low-risk pregnancies: a randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;113(4A):402-408.

DH (Department of Health). NHS Maternity Statistics, England: 2004–2005. London: Department of Health, 2006.

Dimond B. Legal aspects of midwifery, 3rd edn. Hale: Books for Midwives Press, 2006.

Edmunds J. Prolonged labor: past and present. Midwifery Today. Summer, 1998, 13-14.

Elghorori MRM, Hassan I, Dartan W, et al. Comparison between subjective and objective assessments of the cervix before induction of labour. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;26(6):521-526.

El Halta V. Preventing prolonged labor. Midwifery Today. Summer, 1998, 22-27.

El-Hamamy E, Arulkumaran S. Poor progress of labour. Current Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;15(1):1-8.

Fok WY, Chan LY, Tsui MH, et al. When to induce labour for post-term? A study of induction at 41 weeks versus 42 weeks. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Reproductive Biology. 2006;125:206-210.

Fox H. Ageing of the placenta. Archives of Diseases in Childhood. 1997;77(3):171-175.

Gülmezoglu AM, Crowther CA, Middleton P. Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2006. CD004945

Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hellman J, et al. Induction of labour as compared with serial antenatal monitoring in post-tem pregnancy. A randomized controlled trial. The Canadian Multicenter Post-term Pregnancy Trial Group. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326(24):1587-1592.

Harper TC, Coeytaux RR, Chen W, et al. A randomized controlled trial of acupuncture for initiation of labour in nulliparous women. Journal of Maternal–Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2006;19(8):465-470.

Hayman R. Poor progress in labour. In: Luesley DM, Baker PN, editors. Obstetrics and gynaecology. An evidence-based text for MRCOG. London: Arnold, 2004.

Heimstad R, Skogvoll E, Mattsson LA, et al. Induction of labour or serial antenatal fetal monitoring in post term pregnancy: a randomised controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2007;109(3):609-617.

Hovi M, Raatikainen K, Heiskanen N, et al. Obstetric outcome in post-term pregnancies: time for reappraisal in clinical management. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2006;85(7):805-809.

Kavanagh J, Kelly AJ, Thomas J. Sexual intercourse for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2001. CD003093

Kavanagh J, Kelly AJ, Thomas J. Breast stimulation for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2005. CD003392

Kelly AJ, Kavanagh AJ, Thomas J. Castor oil, bath and/or enema for cervical priming and induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2001. CD003099

Kelly AJ, Kavanagh J, Thomas J. Vaginal prostaglandin (PGE2 and PGF2a) for induction of labour at term. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2003. CD003101

Koklanaris N, Tropper P. Post term pregnancy. Female Patient. 2006;31(6):14-18.

Kramer MS, Rouleau J, Baskett TF, et al. Amniotic-fluid embolism and medical induction of labour: a retrospective, population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2006;368(954521):1444-1448.

Laursen M, Bille C, Olesen AW, et al. Genetic influence on prolonged gestation: a population-based Danish twin study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2004;190:489-494.

Lavender T, Alfirevic Z, Walkinshaw S. Effect of different partogram action lines on birth outcomes: a randomised controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;108:295-302.

Menticoglou SM, Hall PF. Routine induction of labour at 41 weeks gestation: nonsensus consensus. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2002;109(5):485-491.

Mogren I, Stenlund H, Hogberg U. Recurrence of prolonged pregnancy. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;28(2):253-257.

Neff M. ACOG Guidelines on management of post term pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2004;104(3):639-645.

Neilson JP, Lavender T, Quenby S, et al. Obstructed labour. British Medical Bulletin. 2003;67(1):191-204.

NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence). Intrapartum care. Care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. NICE, London, 2007.

NICE (National Institute for Clinical Excellence). Antenatal care: routine care for the healthy pregnant woman National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. London: NICE, 2008.

NICE (National Institute for Clinical Excellence). Induction of labour. London: NICE, 2008.

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council). Midwives rules and standards. London: NMC, 2004.

Nystedt A, Hogberg U, Lundman B. The negative birth experience of prolonged labour: a case-referent study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2005;14:579-586.

Nystedt A, Hogberg U, Lundman B. Some Swedish women’s experiences of prolonged labour. Midwifery. 2006;22:56-65.

Olesen AW, Westergaard JG, Olsen J. Prenatal risk indicators of a prolonged pregnancy. The Danish Birth Cohort 1998–2001. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2006;85(11):1338-1341.

RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists). Induction of labour. London: RCOG, 2001. Evidence-based Clinical Guideline No. 9

RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists). Management of HIV in pregnancy. 2004. Guideline No. 39. Online. Available http://rcog.org.uk.

Selo-Ojeme D, Pisal P, Barigye O, et al. Are we complying with NICE guidelines on the use of prostaglandin E2 for induction of labour? A survey of obstetric units in the UK. Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2007;27(2):144-147.

Shetty A, Mackie L, Danielian P, et al. Sublingual compared with oral misoprostol in term labour induction: a randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2002;109(6):645-650.

Shetty A, Livingstone I, Acharya S, et al. Oral misoprostol (100 μg) versus vaginal misoprostol (25 μg) in term labour induction: a randomised comparison. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2003;82(12):1103-1106.

Smith CA. Homoeopathy for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2003. CD003399

Smith CA, Crowther CA. Acupuncture for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2004. CD002962

Smyth R, Alldred SK, Markham C. Amniotomy for shortening spontaneous labour (Protocol). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2007. CD006167

Svärdby K, Nordström L, Sellström E. Primiparas with or without oxytocin augmentation: a prospective descriptive study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2006;16:179-184.

Thornton JG, Hornbuckle J, Vail A, et al. Infant wellbeing at 2 years of age in the Growth Restriction Intervention Trial (GRIT): multicentred randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9453):513-520.

Tomlinson AJ, Archer PA, Hobson S. Induction of labour: a comparison of two methods with particular concern to patient acceptability. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2001;21(3):239-241.

Van Meir CA, Ramirez MM, Matthews, et al. Chorionic prostaglandin metabolism is decreased in the lower uterine segment with term labour. Placenta. 1997;18:109-114.

Vause S, Macintosh M, Glass MR. Evidence based case report: Use of prostaglandins to induce labour in women with a caesarean section scar. British Medical Journal. 1999;318:1056-1058.

WHO. Recommended definitions, terminology and format for statistical tables related to the perinatal period and use of a new certificate for cause of perinatal deaths: modifications recommended by FIGO. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1977;56:247-253.

WHO. Maternal and Safe Motherhood Programme. World Health Organization partograph in the management of labour. Lancet. 1994;343:1399-1404.

Wong SF, Hui SK, Choi H, et al. Does sweeping of membranes beyond 40 weeks reduce the need for formal induction of labour? British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2002;109(6):632-636.