Chapter 17 Antenatal care

Antenatal care refers to care given to a pregnant woman from the time conception is confirmed until the beginning of labour. The midwife should provide a woman-centred approach to the care of the woman and her family by sharing information with the woman to help her make informed choices about her care.

Introduction

Antenatal care was first offered in the late 1920s (Ministry of Health 1929). The model of antenatal care followed a traditional regime of monthly visits until 28 weeks’ gestation, then fortnightly visits until 36 weeks, then weekly visits until the birth of the baby. This model was challenged in the 1980s by Hall et al (1980) whose retrospective analysis demonstrated that health professionals’ expectations of antenatal care might not be met by this provision of care. They found that conditions requiring hospitalization, including pre-eclampsia, were neither prevented nor detected by antenatal care; and intrauterine growth restriction was over-diagnosed.

A more flexible approach to the timing of visits and place of consultation was incorporated into midwifery practice (Clement et al 1996, Jewell et al 2000, Sikorski et al 1996). This was in an attempt to improve maternal satisfaction by the provision of holistic, individualized care and organizational change in the pattern of care (DH 2004, 1993). Sikorski et al (1996) conducted a randomized controlled trial, with low risk pregnant women, to compare the acceptability and effectiveness of a reduced antenatal visit schedule of six to seven routine visits with the traditional 13 routine visits. No differences in clinical outcome between the two groups were found, but twice as many women in the reduced-visit group were dissatisfied with the frequency of attendance, compared with women who received the full range of visits. A substantial number of women in both groups felt that the gaps in their care were too long, with women in the reduced-visit group feeling less remembered from one visit to the next.

A report for The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE 2003) indicated that women may be less satisfied with a reduced pattern of antenatal visits, however, low risk women can be cared for with this reduced pattern without detrimental maternal or fetal effects. It is important to note, however, that the most recent study referred to by NICE (2003) was a large randomized controlled trial conducted in Saudi Arabia, Thailand, Cuba and Argentina, where less than 20% of women were cared for antenatally by a midwife as their main provider (Villar et al 2001). Comparing five visits with eight visits had minimal impact on maternal and perinatal outcomes (Villar et al 2001). The need to provide a more individualized, flexible approach to care, with increased psychosocial support for those pregnant women who needed it, was one of the main conclusions of this study. Clement et al (1996) and NICE (2003) agree that women who had a midwife willing to spend time with them and facilitate them to ask questions were more likely to be satisfied with reduced visits than those whose midwife did not offer this.

Traditional visiting versus flexible visiting, by a midwife, was studied in 11 primary care centres with 609 women (Jewell et al 2000). Comparing the two groups, no difference was found either in attitudes to pregnancy and motherhood or in women urgently reporting antenatal problems. However, women in the flexible care group would like to have been seen more often, although they liked the choices associated with the individualized approach to planning visits (Jewell et al 2000). Rates of obstetric complications did not differ between groups (Jewell et al 2000). Villar & Khan-Neelofur (2001), who reviewed randomized controlled trials involving 25 000 women, support this finding. Evidence supports the view that perinatal outcomes are not adversely affected by a reduction in visits, nor by midwife-led models of care when a woman’s pregnancy is uncomplicated (Jewell et al 2000, Villar & Khan-Neelofur 2001). In 2008 NICE partially updated and replaced their 2003 antenatal guidelines, see Box 17.1 for the revised recommended visiting pattern.

Box 17.1 Antenatal visiting pattern as advocated by NICE (2008)

Oakley et al (1990) explored a bespoke approach to antenatal care and showed that an individual approach best supported women’s needs. A randomized controlled trial examined the effect of providing social support to women who had previously had one or more babies with a birth weight less than 2500g. Women who had an increased likelihood of being socially disadvantaged in pregnancy were identified and a research midwife gave additional support to them. The midwife visited this group of women a minimum of three times during their pregnancy. She could be contacted by telephone 24 hrs a day, gave practical advice and information, made referrals to other healthcare professionals as necessary but did not give any clinical care. Women and babies in this group experienced improved outcomes, fewer hospital admissions in pregnancy, fewer very low birth weight babies, reduced need for neonatal intensive care and women reporting healthier babies in the first few weeks of life, compared with the control group.

A year later, women felt less anxious about their babies and more positive about motherhood. Six years later, the psychological and health benefits in the intervention group had continued, compared with women in the control group (Oakley et al 1996). Government-led initiatives, such as Sure Start, support the findings of Oakley’s work and have been developed throughout the UK; positive results for the health and well-being of under-5s in disadvantaged areas are clearly found (Barnes et al 2006). Extending the boundaries of midwifery care to offer social support demonstrates the positive effect of an holistic approach to care of women and their families with positive outcomes in terms of lifestyle, employment and the growth and development of children (Leamon & Viccars 2007).

The aim of antenatal care

The aim of antenatal care is to monitor the progress of pregnancy to optimize maternal and fetal health. It is essential that the midwife critically evaluates the physical, psychological and sociological effects of pregnancy on the woman and her family. The midwife achieves this by:

Women will attend antenatal care if it offers them information and choice about childbirth. It needs to meet their expectations and support them to be in control of their childbirth experience. Women may have to meet demands of work, family and children, which can be stressors affecting the pregnancy. Education from health professionals, schools, the media, television and lay childbirth organizations give contrasting views about the normality of pregnancy and childbirth which can make decision-making during pregnancy challenging.

Midwives should be approachable, flexible and adapt to meet women’s individual needs. Midwives provide the infrastructure for antenatal care within an environment of trust and safety and should offer evidence-based information for informed choices (see Ch. 4). Five steps to help to sensitivity and evidence for practice are (Page 2006, p 360):

This method, incorporating individual needs, with sources of credible evidence will facilitate optimum antenatal care. The midwife has roles as counsellor and mediator and may need to utilize skills to deal with conflict or communication difficulties. The midwife has a responsibility to refer the family to appropriate professional or lay organizations when provision of care extends beyond her role (NMC 2004).

A birth plan can be instrumental in assisting the woman towards having the birth experience of her choice or at least to consider what she might like to do during labour and what is important to her. Lundgren et al (2003) suggest that birth plans do not enhance the childbirth experience for all but some women felt that aspects of pain, fear and concern for their baby were alleviated by having a birth plan. Most satisfaction with childbirth in this study was related to the relationship women developed with their midwife in labour, irrespective of whether or not they had prepared a birth plan (Lundgren et al 2003). Thus, birth plans are likely to be most effective if they are written with the midwife sharing information to enable the woman to make plans that reflect current practice and care.

When women carry their own maternity records, it was found to enhance their satisfaction with antenatal care and communication with health professionals (NICE 2008, Webster et al 1996) and their feeling of control during pregnancy (Elbourne et al 1987, Homer et al 1999, NICE 2008).

The initial assessment (booking visit)

The purpose of this visit is to introduce the woman to the maternity service. Information is shared between the woman and midwife in order to discuss, plan and implement care for the duration of the pregnancy, the birth and postnatal period. General conversation about the woman’s experiences can be a more useful way of sharing information between woman and midwife compared with asking a list of questions or filling in computer data (McCourt 2006).

Questions need to be open and facilitate a discussion to collect salient information. McCourt (2006) found that information shared did not differ between hospital and home. The way in which midwives communicated with women differed between those case holding where a partnership approach was used and a conventional model of care where a more ‘professional/didactic’ guiding technique was used (McCourt 2006).

Early contact with the midwife, ideally by 10 weeks, is important so that appropriate and valuable advice relating to nutrition and care of the developing fetal organs, which are almost completely formed by 12 weeks’ gestation, may be given. Medical conditions, infections and lifestyle may all have a profound and detrimental effect on the fetus during this time.

Early stages of pregnancy may leave the mother feeling exhausted, nauseous and overwhelmed with the changes occurring in her body. Women are encouraged to access their midwife through their local health centre on confirmation or suspicion of a positive pregnancy test and should be facilitated to do this. They do not require referral from a GP, but the midwife may refer when known medical or psychological problems could impact on the pregnancy or the condition. It is important for the midwife to maintain continuity with the woman even if she is not providing total care during the pregnancy; she can act as an advocate for the woman to enhance care given (e.g. by accompanying her to consultant appointments). It is also important for the midwife to comprehend and promote normality within the context of high risk care.

Models of midwifery care

Women can choose from a variety of midwifery care options. However, there may be restrictions resulting from resource allocation to accessing some of these, dependent on where the woman lives and what services are offered locally. Options for place of birth include the home, a birth centre or a tertiary hospital. Midwives have been shown to exert the most influence over decisions about place of birth compared with other health professionals and lay personnel (Barber et al 2007, 2006a,b).

The majority of women receive antenatal care in the community, either in their own home or at a local clinic. Hospital or community based clinics are available for women who receive care from an obstetrician or physician in addition to their midwife. Women who have identified risk factors or develop complications during pregnancy will usually plan for a hospital birth. The Government is keen to promote birth at home as an option for all women with low risk pregnancies, but fundamental to this is women’s choice (Redshaw et al 2006).

Introduction to the midwifery service

The woman’s first introduction to midwifery care is crucial in forming her initial impressions of the maternity service. A friendly, professional approach will enable the development of a positive partnership between the woman and the midwife. The initial visit focuses on the exchange of information (Box 17.2). This helps the midwife and the woman to get to know each other. The midwife may meet other members of the family and in this way gain a more informed view of the woman’s needs. The midwife will also recognize that there are occasions when the woman may need to spend time alone with her to facilitate discussion, which she may not feel able to have in the presence of family members. For example, it is important for the midwife to recognize her own attitudes to culture and religion and to accept individual differences that may conflict with these (Schott & Henley 1996). Receiving antenatal care from a midwife in an unknown or unfamiliar environment may be the first time some women have experiences outside their own community.

Box 17.2 Objectives for the initial assessment

Communication

The midwife requires many skills to achieve optimal antenatal care, fundamentally the ability to communicate effectively and sensitively. McCourt (2006) suggests that ‘knowledge and confidence’ in the woman will develop as her relationship with the midwife progresses. The National Service Framework for children, young people and the maternity service supports earlier policy in its emphasis on basic principles of care as a means of achieving satisfaction for women in pregnancy and childbirth (DH 2004, 1993).

Listening skills involve attending to or focusing on what the woman is saying, considering the words, phrases and general content of what is said (Morrison & Burnard 1997). The fluency, timing, volume and pitch of the woman’s voice all impact on how the midwife listens to her. In addition, non-verbal responses, including facial expression, body position, eye contact, proximity to the midwife and touch, will affect the flow of information between woman and midwife.

The midwife can promote communication with the woman during discussion by gentle questioning, open-ended statements and reflecting back keywords from what is said, to encourage and facilitate exploration of what is meant (Stein-Parbury 1993). Communication encompasses writing accurate, comprehensive and contemporaneous records of information given and received and the plan of care that has been agreed (NMC 2006). This is essential when there is shared care within the multidisciplinary team, as well as to ensure that the woman understands the records she holds (NMC 2004).

First impressions

A midwife can gain much from the initial observation and assessment of a woman at the start of their first meeting. Previous experiences of the health or maternity services can impact on how the woman will respond to meeting her midwife and her emotional response to this may depend on the empathic and caring response she is met with on their first meeting. The assessment should be carried out sensitively, enabling the woman to express her concerns about this or previous experiences of pregnancy or birth. While it is important for the midwife to be welcoming and enthusiastic towards the woman, it must not be assumed that in all cases the pregnancy is wanted. Observation of physical characteristics is also important. Poor posture and gait can indicate back problems or previous trauma to the pelvis. The woman may be lethargic, which could be an indication of extreme tiredness, anaemia, malnutrition or depression.

Social history

It is useful to assess the response of the whole family to the pregnancy. Some families may experience overcrowding, and need support from the midwife to find out about re-housing. Some women may be overwhelmed by having to care for a new baby and other children; some children may find it difficult to accept the prospect of a new baby into the family. The woman may be a teenager, still under her parents’ care and there may be issues of how much support they can offer their daughter during pregnancy and following the birth. Additional support from a range of lay and professionals will support the teenager through pregnancy in terms of accommodation and schooling for example (Ch. 3).

The Government is committed to improving health and reducing health inequalities in pregnant women and their young children (see Chs 3 and 51). The midwife may, in partnership with the woman, advocate referral to a social worker who has a role in alleviating some of these difficulties or to other multiprofessional agencies where assistance can be obtained.

Domestic violence is an ongoing problem and it is important for the midwife to explore sensitively this issue when possible with the woman during her antenatal care. Midwives should be trained to ask all women if they experience abuse during or prior to pregnancy (Lewis 2007). Support can then be offered with the multiprofessional team working together. Bacchus et al (2004) found that 23% of women had life experience of domestic violence. The woman may only disclose information if she is alone; the midwife must be vigilant during pregnancy for signs or symptoms of domestic violence (NICE 2003). The risk of domestic violence may be more significant in single or women separated from their partners or in those not cohabiting (Bacchus et al 2004, Mezey et al 2005).

General health

General health should be discussed and good habits reinforced, giving further advice when required. All women should be provided with information about healthy eating, and vitamin D supplementation will be recommended for women at risk of deficiency (NICE 2008).

Exercise

Usual aerobic or strength conditioning exercise should be continued (RCOG 2006). Not only will this enhance general well-being, but also reduce stress and anxiety and prepare the body for the challenge of labour. Any activity which can cause trauma or physical injury to the woman or fetus should be avoided (RCOG 2006) (see Ch. 16). Sexual intercourse during pregnancy may continue and has been found to reduce the likelihood of premature labour between 29 and 36 weeks (Sayle et al 2001).

Smoking

Evidence suggests that 33% of women smoke during pregnancy (DH 2005). Some women may be ready to cut down or give up smoking, while others may not want to change their smoking behaviour (Prochaska 1992). Motivating women to change their behaviour can be helpful; the midwife can be influential in setting goals to cut down or quit smoking (McLeod et al 2004, 2003, DH 2007a). Walker and Walker (2006) state that significant effects of smoking on the fetus occur in late pregnancy and therefore strategies to quit should be continued throughout pregnancy.

Babies born to women who smoke are frequently smaller by up to 458 g (Roquer et al 1995) (see Ch. 42), they frequently have respiratory problems at birth and in their first year; there are also higher rates of prematurity, stillbirth and low birthweight (Floyd et al 1993, Li & Windsor 1993). There is an increased risk of asthma and otitis media in these babies (Nafstad et al 1996). The midwife should offer referral to local organizations and the NHS Quit Smoking line (DH 2007a). Nicotine replacement therapy should be discussed with women having difficulty quitting smoking (NICE 2008).

The woman, her partner and other family members should be informed about the direct and passive effects of smoking on the baby. Smoking in pregnancy increases the risk of babies dying from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (Blair et al 1996). Babies of women who smoke 15 cigarettes a day have a 15 times greater risk of dying from SIDS than babies of a non-smoker (Mitchell et al 1997).

Alcohol

The effects of alcohol on the fetus are marked, particularly in the 1st trimester when fetal alcohol syndrome can develop. This syndrome consists of restricted growth, facial abnormalities, central nervous system problems, behavioural and learning difficulties (CDC 2007, DH 2007b, NOFAS-UK 2007). It is recommended that pregnant women abstain from alcohol during pregnancy (DH 2007b) (see Ch. 48).

Menstrual history and expected date of delivery

An accurate menstrual history helps determine the expected date of delivery (EDD), enables the midwife to predict a birth date and subsequently calculate gestational age at any point in the pregnancy. However, midwives are often inaccurate in the way in which they do this (Stenhouse et al 2003). Midwives may wish to consider giving women a ‘baby born by’ date instead of an EDD which is the date at which they would be 42 weeks’ pregnant. This may help to reduce the anxiety felt by women and their families once they reach term. The midwife has a role in helping the woman to understand that an EDD is 1 day between 37 and 42 weeks’ gestation during which her baby is term, and may be born.

The EDD is calculated by adding 9 calendar months and 7 days to the date of the first day of the woman’s last menstrual period (known as Naegele’s Rule). This method assumes that:

The duration of pregnancy based on Naegele’s rule suggests that the duration of a pregnancy is 280 days. However, it is useful to consider that if the woman has a 35 day cycle then 7 days should be added to the EDD owing to the long second menstrual phase; if her cycle is less than 28 days then the appropriate number of days is subtracted (see Ch. 10).

Controversy exists over the suitability of applying Naegele’s rule to determine EDD. Predicted dates of delivery were studied in over 14 000 women with a reliable date of LMP, average length of pregnancy of 280 or 282 days (Nguyen et al 1999). They found the average discrepancies between dates of delivery predicted from the bi-parietal diameter, or BPD (on ultrasound in the second trimester) were 7.96 and 8.63 days, respectively. The error of the LMP method alone was reduced significantly by adding 282 days to the LMP instead of 280 days. This method would reduce the incidence of post-term pregnancy; however, the authors concluded that use of BPD alone is superior to the use of LMP, but if LMP is the only predictor available then 282 days should be added to the LMP.

These data support that of Tunon et al (1996) who found that if LMP and ultrasound differed by less than 8 days, then neither method could more accurately predict EDD. However, as the difference in gestational age between the two methods increases, ultrasound becomes the more accurate method for predicting the EDD. These findings do depend on the availability of and accessibility to an experienced ultrasonographer and the woman’s consent to have an ultrasound scan. Kalish & Chervenak (2005) suggest that head circumference is the best measure for determination of gestational age. NICE (2008) now recommend crown–rump measurement between 10 weeks 0 days and 13 weeks 6 days and if above 84 mm, then measure head circumference. Nuchal translucency can be identified between 11 and 14 weeks as part of the ‘combined test’ for Down syndrome screening and the 18–20 week scan for structural abnormality screening (NICE 2008) (see Ch. 18). For women who book after 14 weeks, the triple or quadruple serum screening test can be offered between 15 and 20 weeks. Information about ultrasound will be offered by the midwife and peer reviewed leaflets can support this process (MIDIRS 2008a).

Obstetric history

Previous childbearing experiences have an important part to play in possible outcome prediction of the current pregnancy. In order to give a summary of a woman’s childbearing history, the descriptive terms gravida and para are used. ‘Gravid’ means ‘pregnant’, gravida means ‘a pregnant woman’, and a subsequent number indicates the number of times she has been pregnant regardless of outcome. ‘Para’ means ‘having given birth’; a woman’s parity refers to the number of times that she has given birth to a child, live or stillborn, excluding abortions. A grande multigravida is a woman who has been pregnant five times or more, irrespective of outcome. A grande multipara is a woman who has given birth five times or more.

A sympathetic non-judgemental approach is required to elicit information and encourage the woman to talk freely about her experiences of previous births, miscarriages or terminations. The booking visit may be the first opportunity a woman has to discuss her last experience of labour and birth in detail. A pregnancy loss may have affected the way in which the woman accepted it at the time, perhaps grieving the loss of hopes and expectations of a pregnancy (Raphael-Leff 2005). This may lead to suppression of feelings, which could interfere with emotional adjustment to the present pregnancy. Any form of miscarriage/abortion occurring in a Rhesus negative woman requires prophylactic administration of anti-D immunoglobulin to reduce the risk of Rhesus incompatibility in a subsequent pregnancy (see Ch. 47).

Confidential information may be recorded in a clinic-held summary of the pregnancy and not in the woman’s handheld record if she requests this. Repeated spontaneous fetal loss may indicate such conditions as genetic abnormality, hormonal imbalance or incompetent cervix (see Ch. 19). The woman may be more anxious about the pregnancy and will usually be relieved when it progresses past the date of previous fetal loss. Minor disturbances in pregnancy may be exacerbated and preoccupation with the pregnancy may lead to other psychological, social or physical problems. The woman may be reassured if she hears the fetal heart or sees the image of her unborn baby on an ultrasound scan.

For completeness of the history, reference to old case notes should be made to elicit all the relevant information. A risk assessment should be carried out based on the woman’s obstetric, medical and social history and current pregnancy. This will enable the midwife and woman to discuss the progress of her pregnancy and identify other health professionals who may need to be involved. If risk factors such as those listed in Box 17.3 are identified, they can help to determine the frequency of antenatal visits and alert staff to appropriate screening techniques. This should follow an individualized approach, using Page’s five steps (Page 2006). The location of antenatal care will be determined by the availability of support services, senior obstetric staff and experienced midwives. Place of birth will also be influenced by the risk assessment but in all cases the ultimate decision is taken by the woman who should make an informed choice (MIDIRS 2008b).

Medical history

During pregnancy both the mother and the fetus may be affected by a medical condition, or a medical condition may be altered by the pregnancy; if untreated there may be serious consequences for the woman’s health (Lewis 2007).

Family history

Certain conditions are genetic in origin, others are familial or related to ethnicity, and some are associated with the physical or social environment in which the family lives. There is a higher mortality rate in babies born to mothers of Pakistan or Caribbean origin (DH 1999). Lewis (2007) demonstrated that women from minority ethnic groups were three times more likely to die than Caucasian women and the mortality rate was seven times higher in black African and asylum seekers than white women. There is also evidence of a high rate of consanguinity within Pakistani families which can adversely affect outcomes (Bundey & Alan 1991). Genetic disease in the baby is much more likely to occur if his biological parents are close relatives such as first cousins (Stoltenberg et al 1998).

Diabetes, although not inherited, leads to a predisposition in other family members, particularly if they become pregnant or obese. Hypertension also has a familial component and multiple pregnancy has a higher incidence in certain families. Some conditions such as sickle cell anaemia and thalassaemia are more common in black Caribbean, African-Caribbean, African, Pakistani, Cypriots, Bangladeshis and those of Chinese ethnicity (NICE 2008) (see Ch. 21). Screening for gestational diabetes is now recommended using a risk factor approach.

Physical examination

Prior to conducting the physical examination of a pregnant woman, her consent and comfort are primary considerations. Sophisticated biochemical assessments and ultrasound investigations can enhance clinical observations.

It is therefore important to look holistically at the woman and her family and assess fetal growth and development by recognized markers in conjunction with this knowledge.

Weight

Normal weight gain in pregnancy ranges from 7–18 kg for a 3–4 kg baby. Normal body mass index (BMI) should be calculated at booking, based on pre-pregnancy weight. Referral to an obstetrician should be made if it is <18 kg/m2 or ≥30 kg/m2 (NICE 2008) (see Ch. 13). Women with a BMI in the obese range are more at risk of complications of pregnancy. These may include gestational diabetes, PIH and shoulder dystocia. There may also be difficulty in palpating the fetal parts and defining presentation, position or engagement of the fetus. Overweight or underweight women should be carefully monitored, have additional care from an obstetrician, and be offered appropriate support including nutritional counselling within the multiprofessional team.

Blood pressure

Blood pressure is taken in order to ascertain normality and provide a baseline reading for comparison throughout pregnancy. Systolic blood pressure does not alter significantly in pregnancy, but diastolic falls in mid pregnancy and rises to near non-pregnant levels at term. The systolic recording may be falsely elevated if a woman is nervous or anxious; long waiting times can cause additional stress; white coat hypertension whereby the BP is higher than normal by 30 mmHg can occur during the procedure or in a doctor’s surgery (Beevers et al 2001a). If the midwife is aware of this she can arrange to see the woman at home so she is relaxed beforehand. A full bladder can also cause an increase in blood pressure. Blood pressure should be checked with the woman relaxed. The woman should be comfortably seated or resting in a lateral position on the couch for the measurement. Brachial artery pressure is highest when sitting and lower when in the recumbent position.

Current opinion is that Korotkoff V should be used (Beevers et al 2001a, Walfish & Hallak 2006). An elevation of more than 30 mmHg systolic or 15 mmHg diastolic on at least two occasions 6 hrs apart warrants investigation (Walfish & Hallak 2006). It has been recommended by NICE (2008, para 1.9.2.5) that if there is a ‘single diastolic blood pressure of 110 mmHg or two consecutive readings of 90 mmHg at least 4 hrs apart and/or significant proteinuria (1+)’, there should be an increase in surveillance. Steps that can be taken to increase accuracy of blood pressure measurement and recording are listed in Box 17.4.

Box 17.4 Factors that increase accuracy of blood pressure measurement and recording (Beevers et al 2001a, b)

Urinalysis

Urinalysis is performed at every visit to exclude proteinuria (NICE 2008, Way 2000). The woman can be shown how to test her own urine and encouraged to test it at subsequent visits. At the first visit a midstream specimen may be sent to the laboratory for culture to exclude asymptomatic bacteruria. This condition exists when a culture is grown of a specific bacterium that exceeds 106 organisms/mL of urine. As it is asymptomatic the woman is unaware of disease and treatment will reduce the risk of preterm labour.

Other possible findings during subsequent routine urinalysis include:

Blood tests in pregnancy

The midwife should explain why blood tests are carried out at the booking visit (NMC 2004). Women should be facilitated by the midwife to make an informed choice about the tests that are available. The midwife should be fully aware of the difference between screening and diagnostic tests, and their accuracy, and discuss these options with women. Blood tests taken at the initial assessment include the following:

ABO blood group and Rhesus (Rh) factor

It is important to identify the blood group, RhD status and red cell antibodies in pregnant women, so haemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN) can be prevented and to prepare for blood transfusion if it becomes necessary. Blood will be taken at booking and again at 28 weeks to determine if antibodies are present (NICE 2008). All Rh negative women will be offered anti-D at 28 and 34 weeks’ gestation (NICE 2002). If the woman’s partner is also Rh negative then anti-D prophylaxis will not be required (NICE 2002). Threatened miscarriage, amniocentesis or any other uterine trauma are indications for the administration of anti-D gammaglobulin within a few days of the event in pregnancy in addition to that given at 28 and 34 weeks (NICE 2002). If the titration demonstrates a rising antibody response then more frequent assessment will be made in order to plan management by a specialist in Rhesus disease (see Ch. 47).

Full blood count

This is taken to observe the woman’s general blood condition, and includes: Haemoglobin (Hb) estimations (see Ch. 14 for normal values). If the mean cell volume (MCV) is found to be low on the full blood count result, serum ferritin levels are also taken in order to assess the adequacy of iron stores. Haemoglobin below 11 g/L at booking is investigated at the 16-week check and iron supplementation considered. Further investigation of an Hb of 10.5 g/L or less will be carried out at 28 weeks when the physiological effects of haemodilution are becoming more apparent. Iron supplementation is not considered necessary in women who are taking adequate dietary iron and who have a normal Hb and MCV at the initial assessment.

The decision to use supplements should be made on an individual basis and include clear information about dietary iron sources. Maximum absorption of iron in meat or green leafy vegetables will be achieved by consuming vitamin C at the same time and avoiding caffeine. The intestinal mucosa has a limited ability to absorb iron and when this is exceeded extra iron is excreted in the stools. Folic acid (400 μg/day) should be taken prior to conception and for the first 12 weeks of pregnancy to reduce the risk of spina bifida (NICE 2008).

Venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test

This is performed for syphilis. Not all positive results indicate active syphilis; early testing will allow a woman to be treated in order to prevent infection of the fetus (see Ch. 23).

HIV antibodies

Routine screening to detect HIV infection should be offered in pregnancy (Ades et al 1999, NICE 2008) as treatment in pregnancy is beneficial in reducing vertical transmission to the fetus. There are many views as to the ethical issues involved in screening. It is important to gain informed consent for any blood tests undertaken and offer appropriate counselling before and after the screening is carried out.

Rubella immune status

This is determined by measuring the rubella antibody titre. Women who are not immune must be advised to avoid contact with anyone suffering from the disease and may wish to discuss termination of pregnancy if they have been exposed. The live vaccination is offered during the puerperium, and subsequent pregnancy must be avoided for at least 3 months.

Investigations for other blood disorders

All women should be offered screening for sickle cell disease or thalassaemias early in pregnancy. Some ethnic groups have a higher incidence than others and the type of screening will depend on the prevalence (NICE 2008). If a woman either has or is a carrier of one of these diseases her partner’s blood should also be tested. The couple will be offered genetic counselling and management during pregnancy will be explained.

Hepatitis B

Screening is offered in pregnancy so that postnatal intervention can be planned to decrease the risk of mother-to-baby transmission (NICE 2003).

Hepatitis C and chlamydia

This is currently not recommended as a routine screening test in pregnancy because the effect and cost effectiveness have not yet been evaluated (NICE 2008).

Cytomegalovirus and toxoplasmosis

These are not routinely done in pregnancy because tests do not currently determine which pregnancies may result in an infected fetus (NICE 2008). Toxoplasmosis screening is not recommended because the risks of screening may outweigh the benefits; however, women need to be informed of how to avoid contracting the infection (NICE 2008) (See Ch. 47).

The midwife’s examination

The midwife’s examination of the woman, with consent, is performed by exchange of information between the woman and midwife and observation rather than physical examination. Communication has been shown to be most effective if the woman is sitting in a comfortable position making eye contact with the midwife.

The midwife’s general examination of the woman should be holistic and should encompass her physical, social and psychological well-being. The usual social contact gives the midwife an opportunity to look at the woman’s face and assess her health and general well-being. Sleeping patterns can be disrupted in pregnancy. Women frequently continue to work throughout pregnancy, therefore they are unlikely to be able to rest during the day and many need to go to bed earlier to alleviate the tiredness. If at any time the midwife notices any sign of ill health she should discuss this with the woman, and advocate referral to the most appropriate health professional.

The midwife should facilitate discussion about infant-feeding. Breastfeeding should be promoted in a sensitive manner, and information given about the benefits to both mother and baby (see Ch. 41, UNICEF 2007). Most women will not require an examination of their breasts. Current evidence does not support the benefits of nipple preparation (Alexander et al 1992). The midwife may also discuss the woman’s experiences of breast changes so far in her pregnancy, and expected changes as pregnancy progresses.

Some women will appreciate information about the body changes taking place during pregnancy. Increasing abdominal size may be an acceptable body change but breast changes may not have been anticipated. For some women, breast size and appearance are an important part of their body image. Partners may also be affected by the changes. The midwife can be influential in discussions with women who had not realized the extent to which pregnancy would change their body. Open and honest discussion between the woman and her partner may help to resolve anxieties. A good relationship in which the couple feels able to share anxieties and fears may minimize some of the difficulties in making the transition to motherhood.

Bladder and bowel function may be discussed; dietary advice may be necessary at this visit or later in the pregnancy with reference to how hormonal changes may alter normal bowel and kidney function. Early referral within the multidisciplinary team will be necessary if treatment is required or problems identified. Vaginal discharge (leucorrhoea) increases in pregnancy; the woman may discuss any increase or changes with the midwife. If the discharge is itchy, causes soreness, is any colour other than creamy-white or has an offensive odour then infection is likely, and should be investigated further. Later in pregnancy the woman may report a change from leucorrhoea to a heavier mucous discharge.

The obstetrician will investigate vaginal bleeding during pregnancy; however, in early pregnancy spotting may occur at the time when menstruation would have been due. Early bleeding is not uncommon; the midwife should advise the woman to rest at this time and avoid sexual intercourse until the pregnancy is more stable. Ultrasound will usually confirm a diagnosis.

Abdominal examination

In the past midwives have palpated the uterus once it has entered the abdomen, from about 12 weeks’ gestation, however current guidelines suggest that because of sophisticated scanning techniques there is no benefit in palpating the uterus prior to 25 weeks’ gestation, at which time uterine growth can be measured (NICE 2008).

Oedema

This should not be evident during the initial assessment but may occur as the pregnancy progresses. Physiological oedema occurs after rising in the morning and worsens during the day; it is often associated with daily activities or hot weather. At visits later in pregnancy the midwife should observe for oedema and ask the woman about symptoms. Often the woman may notice that her rings feel tighter and her ankles are swollen. Pitting oedema in the lower limbs can be identified by applying gentle fingertip pressure over the tibial bone: a depression will remain when the finger is removed. If oedema reaches the knees, affects the face or is increasing in the fingers it may be indicative of hypertension of pregnancy if other markers are also present.

Varicosities

These are more likely to occur during pregnancy and are a predisposing cause of deep vein thrombosis. The woman should be asked if she has any pain in her legs. Reddened areas on the calf may be due to varicosities, phlebitis or deep vein thrombosis. Areas that appear white as if deprived of blood could be caused by deep vein thrombosis. The woman should be asked to report any tenderness that she feels either during the examination or at any time during the pregnancy. Referral should be made to medical colleagues as appropriate (NMC 2004). Support stockings will help alleviate symptoms although not prevent varicose veins occurring (NICE 2008).

Abdominal examination

Abdominal examination is carried out from 25 weeks’ gestation to establish and affirm that fetal growth is consistent with gestational age during the pregnancy.

Preparation

Abdominal examination will be most effective if the woman is consistently in the same position at each antenatal check (Engstrom et al 1993). A study comparing supine, trunk elevation, knee flexion and trunk elevation with knee flexion found there were significant differences between each in estimating fundal height measurements (Engstrom et al 1993). A full bladder will make the examination uncomfortable; this can also make the measurement of fundal height less accurate. It is important that the midwife exposes only that area of the abdomen she needs to palpate, and covers the remainder of the woman to enhance privacy. The woman should be lying comfortably with her arms by her sides to relax the abdominal muscles. The midwife should discuss her findings throughout the abdominal examination with the woman.

Inspection

The size of the uterus is assessed approximately by visual observation. A full bladder, distended colon or obesity may give a false impression of fetal size, however. The shape of the uterus is longer than it is broad when the lie of the fetus is longitudinal, as occurs in the majority of cases. If the lie of the fetus is transverse, the uterus is low and broad.

The multiparous uterus may lack the snug ovoid shape of the primigravid uterus. Often it is possible to see the shape of the fetal back or limbs. If the fetus is in an occipitoposterior position a saucer-like depression may be seen at or below the umbilicus. The midwife may observe fetal movements, or they may be felt by the mother; this can help the midwife determine the position of the fetus. The woman’s umbilicus becomes less dimpled as pregnancy advances and may protrude slightly in later weeks.

Lax abdominal muscles in the parous woman may cause the uterus to sag forwards; this is known as pendulous abdomen or anterior obliquity of the uterus. In the primigravida it is a significant sign as it may be due to pelvic contraction.

Skin changes

Stretch marks from previous pregnancies appear silvery and recent ones appear pink. A linea nigra may be seen; this is a normal dark line of pigmentation running longitudinally in the centre of the abdomen below and sometimes above the umbilicus. Scars may indicate previous obstetric or abdominal surgery.

Palpation

The midwife’s hands should be clean and warm; cold hands do not have the necessary acute sense of touch, they tend to induce contraction of the abdominal and uterine muscles and the woman may find palpation uncomfortable. Arms and hands should be relaxed and the pads, not the tips, of the fingers used with delicate precision. The hands are moved smoothly over the abdomen to avoid causing contractions.

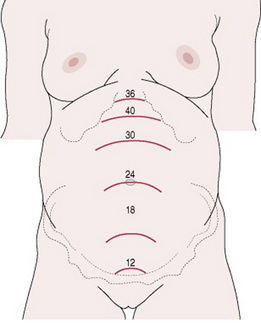

In order to determine the height of the fundus the midwife places her hand just below the xiphisternum. Pressing gently, she moves her hand down the abdomen until she feels the curved upper border of the fundus, noting the number of fingerbreadths that can be accommodated between the two (Fig. 17.1). The distance between the fundus and the symphysis pubis can be determined with a tape measure which is consistent with current practice; the height of the fundus in centimetres should correspond with weeks of gestation to the nearest 3 cm (Neilson 2001). Measurements should be recorded in the pregnancy record or plotted on a chart that gives average findings for gestational age: a symphysis–fundal height chart (Gardosi & Francis 1999, NICE 2008).

Clinically assessing the uterine size to compare it with gestation does not always produce an accurate result but Figure 17.2 is a guide to fundal height at various weeks of pregnancy. If the uterus is unduly big the fetus may be large or it may indicate multiple pregnancy or polyhydramnios. When the uterus is smaller than expected the LMP date may be incorrect, or the fetus may be small for gestational age. Further investigation is warranted and an ultrasound scan will usually be required alongside medical referral (NMC 2004).

Fundal palpation

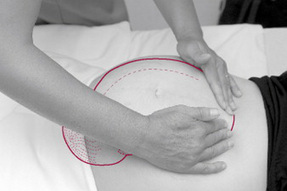

This determines the presence of the breech or the head. This information will help to diagnose the lie and presentation of the fetus. Talking through the palpation with the woman, making eye contact with her during the procedure, the midwife lays both hands on the sides of the fundus, fingers held close together and curving round the upper border of the uterus. Gentle yet deliberate pressure is applied using the palmar surfaces of the fingers to determine the soft consistency and indefinite outline that denotes the breech. Sometimes the buttocks feel rather firm but they are not as hard, smooth or well defined as the head. With a gliding movement the fingertips are separated slightly in order to grasp the fetal mass, which may be in the centre or deflected to one side, to assess its size and mobility. The breech cannot be moved independently of the body but the head can (Fig. 17.3). The head is much more distinctive in outline than the breech, being hard and round; it can be balloted (moved from one hand to the other) between the fingertips of the two hands because of the free movement of the neck.

Lateral palpation

This is used to locate the fetal back in order to determine position. The hands are placed on either side of the uterus at the level of the umbilicus (Fig. 17.4). Gentle pressure is applied with alternate hands in order to detect which side of the uterus offers the greater resistance. More detailed information is obtained by feeling along the length of each side with the fingers. This can be done by sliding the hands down the abdomen while feeling the sides of the uterus alternately. Some midwives prefer to steady the uterus with one hand and, using a rotary movement of the opposite hand, to map out the back as a continuous smooth resistant mass from the breech down to the neck; on the other side the same movement reveals the limbs as small parts that slip about under the examining fingers.

Figure 17.4 Lateral palpation. Hands placed at umbilical level on either side of the uterus. Pressure is applied alternately with each hand.

‘Walking’ the fingertips of both hands over the abdomen from one side to the other is an excellent method of locating the back (Fig. 17.5). The fingers should be dipped into the abdominal wall deeply. Palpating from the neck upwards and inwards can locate the anterior shoulder.

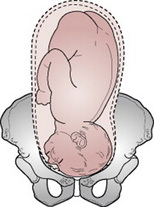

Pelvic palpation

Pelvic palpation can cause contractions of the uterus therefore it is often carried out before fundal and lateral palpation to make the findings easier to determine. However, some would argue that it should be carried out last. Pelvic palpation will identify the pole of the fetus in the pelvis; it should not cause discomfort to the woman. NICE (2008) recommend this is only done from 36 weeks onwards.

The midwife should ask the woman to bend her knees slightly in order to relax the abdominal muscles and also suggest that she breathe steadily; relaxation may be helped if she sighs out slowly. The sides of the uterus just below umbilical level are grasped snugly between the palms of the hands with the fingers held close together, and pointing downwards and inwards (Fig. 17.6).

If the head is presenting (towards the lower part of the uterus), a hard mass with a distinctive round, smooth surface will be felt. The midwife should also estimate how much of the fetal head is palpable above the pelvic brim to determine engagement. The two-handed technique appears to be the most comfortable for the woman and gives the most information. Pawlik’s manoeuvre, where the midwife grasps the lower pole of the uterus between her fingers and thumb, which should be spread wide enough apart to accommodate the fetal head (Fig. 17.7), is sometimes used to judge the size, flexion and mobility of the head, but undue pressure must not be applied. It should be used only if absolutely necessary: There is no research evidence to support one method over the other.

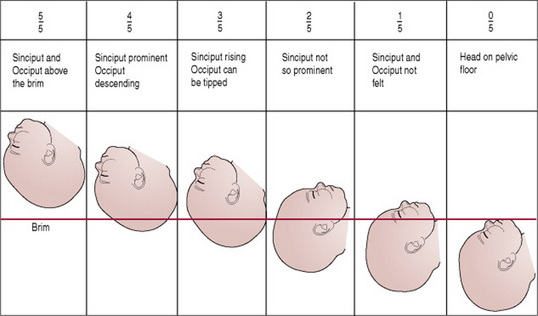

Engagement

Engagement is said to have occurred when the widest presenting transverse diameter has passed through the brim of the pelvis. In cephalic presentations this is the biparietal diameter and in breech presentations the bitrochanteric diameter. Engagement demonstrates that the maternal pelvis is likely to be adequate for the size of the fetus and that the baby will birth vaginally.

In a primigravid woman, the head normally engages at any time from about 36 weeks’ pregnancy, but in a multipara this may not occur until after the onset of labour. Engagement of the fetal head is usually measured in fifths palpable above the pelvic brim. When the vertex presents and the head is engaged the following will be evident on clinical examination:

On rare occasions, the head is not palpable abdominally because it has descended deeply into the pelvis. If the head is not engaged, the findings are as follows:

If the head does not engage in a primigravid woman at term, there is a possibility of a malposition or cephalopelvic disproportion. However, Roshanfekr et al (1999) found that 86% of nulliparous women with a non-engaged head at the onset of active labour proceeded to have a vaginal birth. Therefore, until labour commences, the midwife should assess the woman as usual and monitor the progress of her pregnancy. The force of labour contractions encourages flexion and moulding of the fetal head and the relaxed ligaments of the pelvis allow the joints to give. This may be sufficient to allow engagement and descent. Other causes of a non-engaged head at term include:

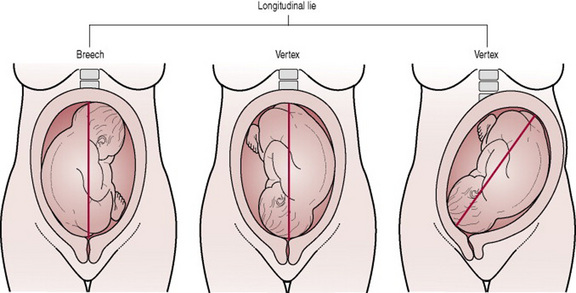

Presentation

Presentation refers to the part of the fetus that lies at the pelvic brim or in the lower pole of the uterus. Presentations can be vertex, breech, shoulder, face or brow (Figs 17.9–17.14). Vertex, face and brow are all head or cephalic presentations. When the head is flexed the vertex presents; when it is fully extended the face presents and when partially extended the brow presents (Figs 17.15–17.18). It is more common for the head to present because the bulky breech finds more space in the fundus, which is the widest diameter of the uterus, and the head lies in the narrower lower pole. The muscle tone of the fetus also plays a part in maintaining its flexion and consequently its vertex presentation.

Auscultation

Listening to the fetal heart has historically been an important part of the process. However, NICE (2008) do not recommend routine listening other than at maternal request because there is no clinical benefit. A Pinard’s fetal stethoscope will enable the midwife to hear the fetal heart directly and determine that it is fetal and not maternal. The stethoscope is placed on the mother’s abdomen, at right angles to it over the fetal back (Fig. 17.19). The ear must be in close, firm contact with the stethoscope but the hand should not touch it while listening because then extraneous sounds are produced. The stethoscope should be moved about until the point of maximum intensity is located where the fetal heart is heard most clearly. The midwife should count the beats per minute, which should be in the range of 110–160. The midwife should take the woman’s pulse at the same time as listening to the fetal heart to enable her to distinguish between the two. In addition, ultrasound equipment (e.g. a sonicaid or Doppler) can be used for this purpose so that the woman may also hear the fetal heartbeat. However, use of a Pinard’s stethoscope will enable the midwife to hear the actual heartbeat and not the reflected sound waves produced from the ultrasound equipment.

Findings

The findings from the abdominal palpation should be considered part of the holistic picture of the pregnant woman. The midwife assesses all the information she has gathered from inspection, palpation and auscultation and critically evaluates the well-being of the woman and her fetus. Deviation from the expected growth and development should be discussed with the woman and referral to an obstetrician can be arranged if required. Concerns about this screening process may also be discussed within the interprofessional team.

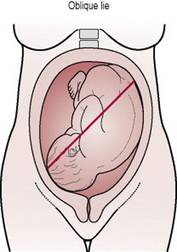

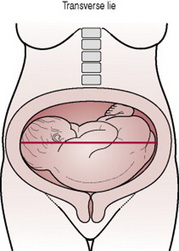

Lie

The lie of the fetus is the relationship between the long axis of the fetus and the long axis of the uterus (Figs 17.20–17.24). In the majority of cases the lie is longitudinal owing to the ovoid shape of the uterus; the remainder are oblique or transverse. Oblique lie, when the fetus lies diagonally across the long axis of the uterus, must be distinguished from obliquity of the uterus, when the whole uterus is tilted to one side (usually the right) and the fetus lies longitudinally within it. When the lie is transverse the fetus lies at right angles across the long axis of the uterus. This is often visible on inspection of the abdomen.

Figures 17.20–17.24 The lie of the fetus.

Figures 17.20–17.22 Depict the longitudinal lie. Confusion sometimes exists regarding Figure 17.22, which gives the impression of an oblique lie, but the fetus is longitudinal in relation to the uterus and merely moving the uterus abdominally rectifies the presumed obliquity.

Attitude

Attitude is the relationship of the fetal head and limbs to its trunk. The attitude should be one of flexion. The fetus is curled up with chin on chest, arms and legs flexed, forming a snug, compact mass, which utilizes the space in the uterine cavity most effectively. If the fetal head is flexed the smallest diameters will present and, with efficient uterine action, labour will be most effective.

Denominator

‘Denominate’ means ‘to give a name to’; the denominator is the name of the part of the presentation, which is used when referring to fetal position. Each presentation has a different denominator and these are as follows:

Although the shoulder presentation is said to have the acromion process as its denominator, in practice the dorsum is used to describe the position. In the brow presentation no denominator is used.

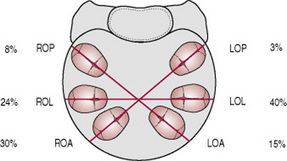

Position

The position is the relationship between the denominator of the presentation and six points on the pelvic brim (Fig. 17.25). In addition, the denominator may be found in the midline either anteriorly or posteriorly, especially late in labour. This position is often transient and is described as direct anterior or direct posterior.

Figure 17.25 Diagrammatic representation of the six vertex positions and their relative frequency: LOA, left occipitoanterior; LOL, left occipitolateral; LOP, left occipitoposterior; ROA, right occipitoanterior; ROL, right occipitolateral; ROP, right occipitoposterior.

Anterior positions are more favourable than posterior positions because when the fetal back is at the front of the uterus it conforms to the concavity of the mother’s abdominal wall and the fetus can flex more easily. When the back is flexed the head also tends to flex and a smaller diameter presents to the pelvic brim. There is also more room in the anterior part of the pelvic brim for the broad biparietal diameter of the head. The positions in a vertex presentation are summarized in Box 17.5 (also see Figs 17.26–17.31)

Box 17.5 Positions in a vertex presentation

In breech and face presentations the positions are described in a similar way using the appropriate denominator.

Assessment of pelvic capacity

According to NICE (2008), routine antenatal pelvic examination is an inaccurate measurement of gestational age, and the likelihood of preterm birth or cephalopelvic disproportion, therefore it is not recommended.

Ongoing antenatal care

The information gathered during the antenatal visits will enable the midwife and pregnant woman to determine the appropriate pattern of antenatal care (NICE 2008). The timing and number of visits will vary according to individual need and changes should be made as circumstances dictate (e.g. as demonstrated in Box 17.6).

Indicators of fetal well-being

Eliciting information about recent fetal movement will reassure the mother. Patterns of fetal movements are a reliable sign of fetal well-being; evidence of usual fetal movements for the woman can be considered normal. However, NICE (2008) supported by Mangesi & Hofmeyr (2007) suggest that fetal movement counting does not prevent fetal morbidity or mortality and therefore is a poor indicator of fetal well-being.

Preparation for labour

During the latter weeks of pregnancy, plans for labour and birth will be a focus of discussion. Most hospitals provide a list of items that they require women to bring with them into hospital for themselves and their baby. If the woman has planned a home birth, she is visited by her midwife to make final arrangements for the birth. In both cases it is important to ensure that women know whom to contact if they need advice about the commencement of labour or have other concerns.

The focus on the positive progress of labour and birth, centering on normality, is a priority but if there is a need to change plans during labour then women and their families should be facilitated by the midwife to make an informed choice. Flexibility and adaptability should be built into the labour and birth plans to ensure an individual approach is adopted and the woman’s needs are met. Parents’ wishes should be recorded in the pregnancy labour notes in addition to discussions about care, which take place between the woman, her family, the midwife and other health professionals who are involved antenatally.

Ades A, Sculpher M, Gibb D, et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of antenatal HIV screening in United Kingdom. British Medical Journal. 1999;319(7219):1230-1234.

Alexander JM, Grant AM, Campbell MJ. Randomised controlled trial of breast shells and Hoffman’s exercises for inverted and non-protractile nipples. British Medical Journal. 1992;304(6833):1030-1032.

Bacchus L, Mezey G, Bewley S. Domestic violence: prevalence in pregnant women and associations with physical and psychological health. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 2004;113(1):6-11.

Barber T, Rogers J, Marsh S. The birth place choices project: phase one. British Journal of Midwifery. 2006;14(10):609-613.

Barber T, Rogers J, Marsh S. The birth place choices project: phase two initiative. British Journal of Midwifery. 2006;14(11):671-675.

Barber T, Rogers J, Marsh S. Increasing out of hospital births: what needs to change? British Journal of Midwifery. 2007;15(1):16-20.

Barnes J, Cheng H, Howden B, et al. Changes in the characteristics of SSLP areas between 2000/1 and 2003/4. 2006. Online. Available dfes/www.surestart.gov.uk.

Beevers G, Lipe G, O’Brien E. ABC of hypertension: blood pressure measurement. British Medical Journal. 2001;332:981-985.

Beevers G, Lipe G, O’Brien E. ABC of hypertension: blood pressure measurement Part II. British Medical Journal. 2001;322:1043-1047.

Blair P, Bensley D, Smith I, et al. Smoking and the sudden infant death syndrome: results from 1993–5 case-control study for confidential enquiry into stillbirths and deaths in infancy. British Medical Journal. 1996;313:195-198.

Bundey S, Alan H. Why do UK born Pakistani babies have high perinatal and neonatal mortality rates. Paediatrica Perinatal Epidemiology. 1991;5(1):101-114.

Clement S, Candy B, Sikorski J, et al. Does reducing the frequency of routine antenatal visits have long term effects? Follow up of participants in a randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1996;106(4):367-370.

CDC (Center for Disease Control). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. 2007. Online. Available http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fas/fasask.htm, (accessed 7 October 2007)

DH. Smoking and pregnancy. 2007. Online. Available http://www.gosmokefree.co.uk/whygosmokefree/smokingpregnancy/index.php, (accessed 6 April 2007)

DH. Alcohol and Pregnancy. 2007. Online. Available http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/News/DH_074968, (accessed 7 October 2007)

DH. Social Services and Public Safety, Infant Feeding Survey. London: DH, 2005.

DH. The National Service framework for children, young people and the maternity services. London: DH, 2004.

DH (Department of Health). Changing childbirth: report of the expert maternity group. London: HMSO, 1993.

DH (Department of Health). Our healthier nation: reducing health inequalities: an action report. London: DH, 1999.

Elbourne D, Richardson M, Chalmers I, et al. The Newbury maternity care study: a randomised controlled trial to assess a policy of women holding their own obstetric records. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1987;94(7):612-619.

Engstrom J, Piscioneri L, Low L. Fundal height measurement part 3 – the effect of maternal position on fundal height measurements. Journal of Nurse-Midwifery. 1993;38(1):23-27.

Farquharson, Greaves. Thromboembolic disease. In: James D, Steer P, Weiner C, et al, editors. High risk pregnancy. 3rd edn. London: Saunders; 2006:938-948.

Floyd R, Rimer B, et al. A review of smoking in pregnancy: effects on pregnancy outcomes and cessation efforts. Annual Review of Public Health. 1993;14:379-411.

Gardosi J, Francis A. Controlled trial of fundal height measurement plotted on customised antenatal growth charts. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;106(4):309-317.

Hall MH, Cheng PK, MacGillivray I. Is routine antenatal care worth while? Lancet. 1980;ii:78-80.

Homer C, Davis G, Everitt L. The introduction of a woman-held record into a hospital antenatal clinic: the bring your own records study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;39(1):54-57.

Jewell D, Sharp D, Sanders J, et al. A randomised controlled trial of flexibility in routine antenatal care. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;107(10):1241-1247.

Kalish R, Chervenak F. Sonographic determination of gestational age. Ultrasound Review of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;5(4):254-258.

Leamon J, Viccars A. West Howe midwifery evaluation: the with me study. Bournemouth: Bournemouth University, 2007.

Lewis G. Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH) Saving Mothers’ Lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer 2003–2005. The 7th report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. CEMACH, London, 2007.

Lewis G, Drife J. Why Mothers Die 1997–1999. The fifth report of the confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. RCOG Press, London, 2001.

Li C, Windsor R. The impact on infant birthweight and gestational age of cotinine-validated smoking reduction in pregnancy. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;269:1519-1524.

Lundgren I, Berg M Lindmark G. Is the childbirth experience improved by a birth plan? Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2003;48(5):322-328.

Mangesi L, Hofmeyr G. Fetal movement counting for assessment of fetal well-being. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007. 1:CD004909

McCourt C. Supporting choice and control? Communication and interaction between midwives and women at the antenatal booking visit. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:1307. 1218

Mcleod M, Benn C, Pullon S, et al. Midwifery Education for women who smoke: A randomised controlled trial. Midwifery. 2004;20(1):37-50.

Mcleod M, Benn C, Pullon S, et al. The midwife’s role in facilitating smoking behaviour during pregnancy. Midwifery. 2003;19(4):285-297.

Mezey G, Bacchus L, Bewley, et al. Domestic violence lifetime trauma and psychological health of childbearing women. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;112(2):197-204.

MIDIRS. Ultrasound scans-what you need to know. Informed choice leaflet (3) for women. MIDIRS, Bristol, 2008.

MIDIRS. where will you have your baby? Informed choice leaflet (10) for women. Bristol: MIDIRS, 2008.

Ministry of Health. Maternal mortality in childbirth. Antenatal clinics: their conduct and scope. London: HMSO, 1929.

Mitchell EA, Tuohy PG, Brunt JM, et al. Risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome following the prevention campaign in New Zealand: a prospective study. Pediatrics. 1997;100:835-840.

Morrison P, Burnard P. Caring and communicating. London: Macmillan Press, 1997.

Nafstad P, Jaakkola JJ, Hagen JA, et al. Breastfeeding, maternal smoking and lower respiratory tract infections. European Respiratory Journal. 1996;9(12):2623-2629.

Neilson JP. Symphysis-fundal height measurement in pregnancy. The Cochrane Library, issue 3. Update Software, Oxford, 2001.

Nguyen T, Larsen T, Enghollm G, et al. Evaluation of ultrasound-estimated date of delivery in 17 450 spontaneous singleton births: do we need to modify Naegele’s rule? Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;14(1):223-228.

NICE. Antenatal care: Routine care for the healthy pregnant woman. London: CG62 NICE, 2008.

NICE. Antenatal and postnatal mental health. London: NICE, 2007.

NICE. Antenatal Care: Routine care for the pregnant woman. London: NICE, 2003.

NICE. Guidance on the use of routine antenatal Anti D prophylaxis for RhD negative women. London: NICE, 2002. Appraisal Guidance No 41

NOFAS-UK National Organisation on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome UK. Online Available http://www.nofas-uk.org/index.asp, 2007. (accessed 7 October 2007)

Nursing and Midwifery Council. Midwives Rules and Standards. London: NMC, 2004.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. A–Z Advice Sheet: Records and record keeping. London: NMC, 2006.

Oakley A, Rajan L, Grant A. Social support and pregnancy outcome. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1990;97:155-162.

Oakley A, Hickey D, Rajan L. Social support in pregnancy: does it have long term effects? Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 1996;14:7-22.

Page L. Being with Jane in childbirth: putting science and sensitivity into practice, 2006. Page L, McCandlish R, editors. The new midwifery science and sensitivity in practice, 2nd edn., London: Churchill Livingstone, 2006.

Prochaska J. What causes people to change from unhealthy to health enhancing behaviour? In: Heller T, Bailey L, Patison S, editors. Preventing cancers. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1992:147-153.

Raphael-Leff J. Psychological processes of childbearing, 4th edn. London: Chapman & Hall, Anna Freud Centre, 2005.

Redshaw M, Rowe R, Hockley C, et al. Recorded delivery: a national survey of women’s experience of maternity care. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, 2006.

RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists). Recreational exercise and pregnancy. 2006. Online. Available http://www.rcog.org.uk/resources/public/pdf/recreational_exercise_pi.pdf, (accessed 7 April 2007)

Roquer J, Figueras J, Botet F, et al. Influence on fetal growth of exposure to tobacco smoking during pregnancy. Acta Paediatrica. 1995;84:118-121.

Roshanfekr D, Blakemore KJ, Lee J, et al. Station at onset of active labor in nulliparous patients and risk of cesarean delivery. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;93(3):329-331.

Sayle A, Savitz D, Thorp J, et al. Sexual activity during late pregnancy and risk of pre-term delivery. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;97:283-289.

Schott J, Henley A. Culture, religion and childbearing in a multiracial society. London: Butterworth Heinemann, 1996.

Sikorski J, Wilson J, Clement S, et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing two schedules of antenatal visits: the antenatal care project. British Medical Journal. 1996;312:546-553.

Stenhouse E, Wright D, Hattersley A, et al. How well do midwives estimate the date of delivery? Midwifery. 2003;19:125-131.

Stein-Parbury. Patient and person developing interpersonal skills in nursing. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1993.

Stoltenberg C, Magnus P, Lie RT, et al. Influence of consanguinity and maternal education on risk of stillbirth and infant death in Norway, 1967–1993. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;148(5):452-459.

Tunon K, Eik-Nes S, Grottum P. A comparison between ultrasound and a reliable last menstrual period as predictors of the day of delivery in 15 000 examinations. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1996;8:178-185.

UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative. The ten steps to successful breastfeeding. 2007. Online. Available http://www.babyfriendly.org.uk/page.asp?page=60, (accessed 7 October 2007

Villar J, Hassan B, Piaggio G, et al. WHO antenatal care randomized trial for the evaluation of a new model of routine antenatal care. The Lancet. 2001;357:1551-1564.

Villar J, Khan-Neelofur D. Patterns of routine antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. The Cochrane Library. Update Software, Oxford, 2001. issue 3

Walfish A, Hallak M. Hypertension. In: James D, Steer P, Weiner C, et al, editors. High risk pregnancy. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006:772-797.

Walker J, Walker A. Substance abuse. In: James D, Steer P, Weiner, et al. High risk pregnancy. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006:721-741.

Way S. Core skills for caring and assessment. Manchester: Books for Midwives, 2000.

Webster J, Forbes K, Foster S, et al. Sharing antenatal care: client satisfaction and use of the ‘patient-held record’. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1996;35(1):11-14.

Williams D. Renal disorders. In: James D, Steer P, Weiner, et al. High risk pregnancy. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006:1098-1124.