Chapter 31 Malpositions of the occiput and malpresentations

Malpositions and malpresentations of the fetus present the midwife with a challenge of recognition and diagnosis both in the antenatal period and during labour.

Occipitoposterior positions

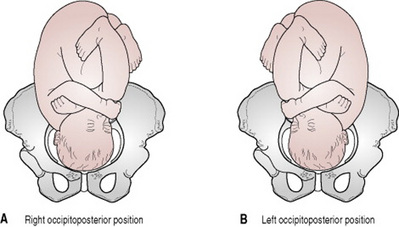

Occipitoposterior positions are the most common type of malposition of the occiput and occur in approximately 10% of labours. A persistent occipitoposterior position results from a failure of internal rotation prior to birth. This occurs in 5% of births (Pearl et al 1993).

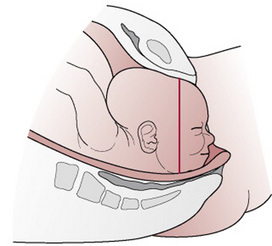

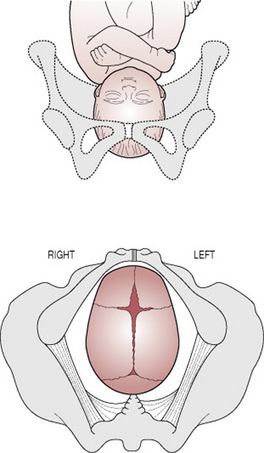

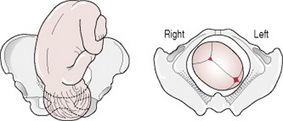

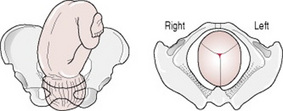

The vertex is presenting, but the occiput lies in the posterior rather than the anterior part of the pelvis. As a consequence, the fetal head is deflexed and larger diameters of the fetal skull present (Fig. 31.1).

Causes

The direct cause is often unknown, but it may be associated with an abnormally shaped pelvis. In an android pelvis, the forepelvis is narrow and the occiput tends to occupy the roomier hindpelvis. The oval shape of the anthropoid pelvis, with its narrow transverse diameter, favours a direct occipitoposterior position.

Antenatal diagnosis

Abdominal examination

Listen to the mother

The mother may complain of backache and she may feel that her baby’s bottom is very high up against her ribs. She may report feeling movements across both sides of her abdomen.

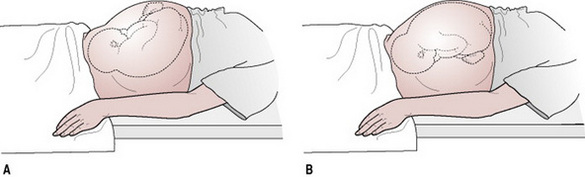

On inspection

There is a saucer-shaped depression at or just below the umbilicus. This depression is created by the ‘dip’ between the head and the lower limbs of the fetus. The outline created by the high, unengaged head can look like a full bladder (Fig. 31.2).

On palpation

While the breech is easily palpated at the fundus, the back is difficult to palpate as it is well out to the maternal side, sometimes almost adjacent to the maternal spine. Limbs can be felt on both sides of the midline.

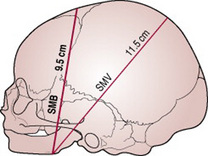

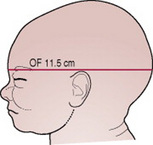

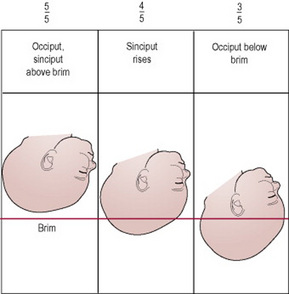

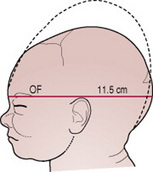

The head is usually high, a posterior position being the most common cause of non-engagement in a primigravida at term. This is because the large presenting diameter, the occipitofrontal (11.5 cm), is unlikely to enter the pelvic brim until labour begins and flexion occurs. The occiput and sinciput are on the same level (Figs 31.3, 31.4). Flexion allows the engagement of the suboccipitofrontal diameter (10 cm).

The cause of the deflexion is a straightening of the fetal spine against the lumbar curve of the maternal spine. This makes the fetus straighten its neck and adopt a more erect attitude.

Antenatal preparation

Anecdotal evidence suggested that active changes of maternal posture would help to achieve an optimal fetal position before labour (El Halta 1998, Sutton 1996). Research has shown that the mother adopting a knee–chest position several times a day may achieve temporary rotation of the fetus to an anterior position but only has a short-term effect upon fetal presentation (Kariminia et al 2004). There is insufficient evidence to suggest that mothers adopt the hands and knees posture unless they find it comfortable. Further research is needed to evaluate the effect of adopting a hands and knees posture on the presenting part during labour (Hofmeyr & Kulier 2005).

Diagnosis during labour

The woman may complain of continuous and severe backache worsening with contractions. However, the absence of backache does not necessarily indicate an anteriorly positioned fetus.

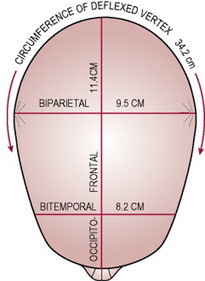

The large and irregularly shaped presenting circumference (Fig. 31.5) does not fit well onto the cervix. Therefore the membranes tend to rupture spontaneously at an early stage of labour and the contractions may be incoordinate. Descent of the head can be slow even with good contractions. The woman may have a strong desire to push early in labour because the occiput is pressing on the rectum.

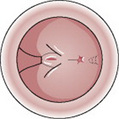

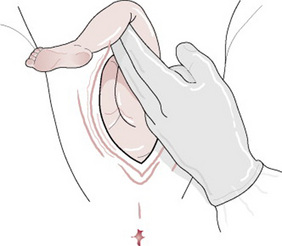

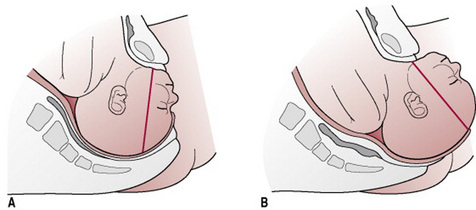

Vaginal examination

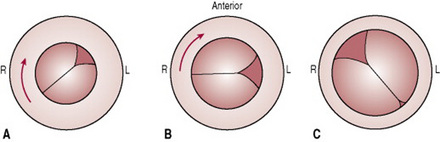

The findings (Fig. 31.6) will depend upon the degree of flexion of the head; locating the anterior fontanelle in the anterior part of the pelvis is diagnostic but this may be difficult if caput succedaneum is present. The direction of the sagittal suture and location of the posterior fontanelle will help to confirm the diagnosis.

Figure 31.6 Vaginal touch pictures in a right occipitoposterior position. (A) Anterior fontanelle felt to left and anteriorly. Sagittal suture in the right oblique diameter of the pelvis. (B) Anterior fontanelle felt to left and laterally. Sagittal suture in the transverse diameter of the pelvis. (C) Following increased flexion the posterior fontanelle is felt to the right and anteriorly. Sagittal suture in the left oblique diameter of the pelvis. The position is now right occipitoanterior.

Care in labour

Labour with a fetus in an occipitoposterior position can be long and painful. The deflexed head does not fit well onto the cervix and therefore does not produce optimal stimulation for uterine contractions.

First stage of labour

The woman may experience severe and unremitting backache, which is tiring and can be very demoralizing, especially if the progress of labour is slow. Continuous support from the midwife will help the mother and her partner to cope with the labour (Thornton & Lilford 1994) (see Chs 25–27). The midwife can help to provide physical support such as massage and other comfort measures and suggest changes of posture and position. The all-fours position may relieve some discomfort; anecdotal evidence suggests that this position may also aid rotation of the fetal head.

Labour may be prolonged and the midwife should do all she can to prevent the mother from becoming dehydrated or ketotic (see Ch. 26).

Incoordinate uterine action or ineffective contractions may need correction with an oxytocin infusion (see Ch. 30).

The woman may experience a strong urge to push long before her cervix has become fully dilated. This is because of the pressure of the occiput on the rectum. However, if the woman pushes at this time, the cervix may become oedematous and this would delay the onset of the second stage of labour. The urge to push may be eased by a change in position and the use of breathing techniques or inhalational analgesia to enhance relaxation. The woman’s partner and the midwife can assist throughout labour with massage, physical support and suggestions for alternative methods of pain relief (see Ch. 27). The mother may choose a range of pain control methods throughout her labour depending on the level and intensity of pain that she is experiencing at that time.

Second stage of labour

Full dilatation of the cervix may need to be confirmed by a vaginal examination because moulding and formation of a caput succedaneum may bring the vertex into view while an anterior lip of cervix remains. If the head is not visible at the onset of the second stage, then the midwife could encourage the woman to remain upright (see Ch. 28). This position may shorten the length of the second stage and may reduce the need for operative delivery. In some cases where contractions are weak and ineffective an oxytocin infusion may be commenced to stimulate adequate contractions and achieve advance of the presenting part. As with any labour, the maternal and fetal conditions are closely observed throughout the second stage. The length of the second stage of labour is usually increased when the occiput is posterior, and there is an increased likelihood of operative delivery (Gimovsky & Hennigan 1995, Pearl et al 1993).

Mechanism of right occipitoposterior position (long rotation) (Figs 31.7-31.10)

Figures 31.7–31.10 Mechanism of labour in right occipitoposterior position.

Figure 31.7 Head descending with increased flexion. Sagittal suture in right oblique diameter of the pelvis.

Figure 31.8 Occiput and shoulders have rotated  of a circle forwards. Sagittal suture in transverse diameter of the pelvis.

of a circle forwards. Sagittal suture in transverse diameter of the pelvis.

Internal rotation of the head

The occiput reaches the pelvic floor first and rotates forwards  of a circle along the right side of the pelvis to lie under the symphysis pubis. The shoulders follow, turning

of a circle along the right side of the pelvis to lie under the symphysis pubis. The shoulders follow, turning  of a circle from the left to the right oblique diameter.

of a circle from the left to the right oblique diameter.

Extension

The sinciput, face and chin sweep the perineum and the head is born by a movement of extension.

Restitution

In restitution the occiput turns  of a circle to the right and the head realigns itself with the shoulders.

of a circle to the right and the head realigns itself with the shoulders.

Internal rotation of the shoulders

The shoulders enter the pelvis in the right oblique diameter; the anterior shoulder reaches the pelvic floor first and rotates forwards  of a circle to lie under the symphysis pubis.

of a circle to lie under the symphysis pubis.

Possible course and outcomes of labour

As with all labours, complicated or otherwise, the mother should be kept informed of her progress and proposed interventions so that she can make informed choices and give informed consent, ensuring the optimum outcome for herself and her baby.

Long internal rotation

This is the commonest outcome, with good uterine contractions producing flexion and descent of the head so that the occiput rotates forward  of a circle as described above.

of a circle as described above.

Short internal rotation

The term ‘persistent occipitoposterior position’ (Figs 31.11, 31.12) indicates that the occiput fails to rotate forwards. Instead the sinciput reaches the pelvic floor first and rotates forwards. The occiput goes into the hollow of the sacrum. The baby is born facing the pubic bone (face to pubis).

Figure 31.11 Persistent occipitoposterior position before rotation of the occiput: position right occipitoposterior.

Figure 31.12 Persistent occipitoposterior position after short rotation: position direct occipitoposterior.

Cause

Failure of flexion. The head descends without increased flexion and the sinciput becomes the leading part. It reaches the pelvic floor first and rotates forwards to lie under the symphysis pubis.

Diagnosis

In the first stage of labour. Signs are those of any posterior position of the occiput, namely a deflexed head and a fetal heart heard in the flank or in the midline. Descent is slow.

In the second stage of labour. Delay is common. On vaginal examination the anterior fontanelle is felt behind the symphysis pubis, but a large caput succedaneum may mask this. If the pinna of the ear is felt pointing towards the mother’s sacrum, this indicates a posterior position.

The long occipitofrontal diameter causes considerable dilatation of the anus and gaping of the vagina while the fetal head is barely visible, and the broad biparietal diameter distends the perineum and may cause excessive bulging. As the head advances, the anterior fontanelle can be felt just behind the symphysis pubis; the baby is born facing the pubis. Characteristic upward moulding is present with the caput succedaneum on the anterior part of the parietal bone (Fig. 31.13).

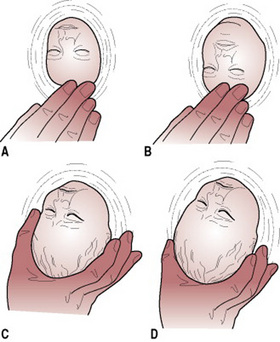

The birth (Figs 31.14-31.17)

The sinciput will first emerge from under the symphysis pubis as far as the root of the nose and the midwife maintains flexion by restraining it from escaping further than the glabella, allowing the occiput to sweep the perineum and be born. She then extends the head by grasping it and bringing the face down from under the symphysis pubis. Perineal trauma is common and the midwife should watch for signs of rupture in the centre of the perineum (‘button-hole’ tear). An episiotomy may be required, owing to the larger presenting diameters.

Undiagnosed face to pubis

If the signs are not recognized at an earlier stage, the midwife may first be aware that the occiput is posterior when she sees the hairless forehead escaping beneath the pubic arch. She may have been misguidedly extending the head and should therefore now flex it towards the symphysis pubis.

Deep transverse arrest

The head descends with some increase in flexion. The occiput reaches the pelvic floor and begins to rotate forwards. Flexion is not maintained and the occipitofrontal diameter becomes caught at the narrow bispinous diameter of the outlet. Arrest may be due to weak contractions, a straight sacrum or a narrowed outlet.

Diagnosis

The sagittal suture is found in the transverse diameter of the pelvis and both fontanelles are palpable. Neither sinciput nor occiput leads. The head is deep in the pelvic cavity at the level of the ischial spines although the caput may be lower still. There is no advance.

Management

The mother must be kept informed of progress and participate in decisions. Pushing at this time may not resolve the problem; the midwife and the woman’s partner can help by encouraging SOS breathing (see Ch. 16). A change of position may help to overcome the urge to bear down.

If an operative delivery is required for the safe delivery of a healthy baby then the mother’s informed consent is required. The procedure would be undertaken under local, regional or more rarely general anaesthesia (see Ch. 32). The considerations are the choice of the mother and the condition of the mother and fetus.

Vacuum extraction has been associated with lower incidence of trauma to both the mother and the infant (Pearl et al 1993) (see Ch. 32). The doctor may choose to use forceps to rotate the head to an occipitoanterior position before delivery. Whichever procedure is undertaken, the mother should first be given adequate analgesia or anaesthesia.

Conversion to face or brow presentation

When the head is deflexed at the onset of labour, extension occasionally occurs instead of flexion. If extension is complete then a face presentation results, but if incomplete the head is arrested at the brim, the brow presenting. This is a rare complication of posterior positions, and is more commonly found in multiparous women.

Complications

Apart from prolonged labour with its attendant risks to mother and fetus and the increased likelihood of instrumental delivery, the following complications may occur.

Obstructed labour

This may occur when the head is deflexed or partially extended and becomes impacted in the pelvis (see Ch. 30).

Maternal trauma

Forceps delivery may result in perineal bruising and trauma. Birth of a baby in the persistent occipitoposterior position, particularly if previously undiagnosed, may cause a third-degree tear (Pearl et al 1993).

Neonatal trauma

Neonatal trauma occurring following birth from an occipitoposterior position has been associated with forceps or ventouse delivery. The outcome for a neonate delivered from an occipitoposterior position is comparable with that expected for an infant delivered from an occipitoanterior position.

Cord prolapse

A high head predisposes to early spontaneous rupture of the membranes, which, together with an ill-fitting presenting part, may result in cord prolapse (see Ch. 33).

Cerebral haemorrhage

The unfavourable upward moulding of the fetal skull, found in an occipitoposterior position, can cause intracranial haemorrhage, as a result of the falx cerebri being pulled away from the tentorium cerebelli. The larger presenting diameters also predispose to a greater degree of compression. Cerebral haemorrhage (see Ch. 45) may also result from chronic hypoxia, which may accompany prolonged labour.

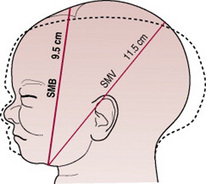

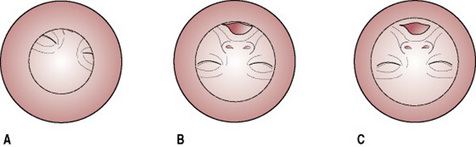

Face presentation

When the attitude of the head is one of complete extension, the occiput of the fetus will be in contact with its spine and the face will present. The incidence is about ≤1:500 (Bhal et al 1998) and the majority develop during labour from vertex presentations with the occiput posterior; this is termed secondary face presentation. Less commonly, the face presents before labour; this is termed primary face presentation. There are six positions in a face presentation (Figs 31.18-31.23); the denominator is the mentum and the presenting diameters are the submentobregmatic (9.5 cm) and the bitemporal (8.2 cm).

Causes

Anterior obliquity of the uterus

The uterus of a multiparous woman with slack abdominal muscles and a pendulous abdomen will lean forward and alter the direction of the uterine axis. This causes the fetal buttocks to lean forwards and the force of the contractions to be directed in a line towards the chin rather than the occiput, resulting in extension of the head.

Contracted pelvis

In the flat pelvis, the head enters in the transverse diameter of the brim and the parietal eminences may be held up in the obstetrical conjugate; the head becomes extended and a face presentation develops. Alternatively, if the head is in the posterior position, vertex presenting, and remains deflexed, the parietal eminences may be caught in the sacrocotyloid dimension, the occiput does not descend, the head becomes extended and face presentation results. This is more likely in the presence of an android pelvis, in which the sacrocotyloid dimension is reduced.

Antenatal diagnosis

Antenatal diagnosis is rare since face presentation develops during labour in the majority of cases. A cephalic presentation in a known anencephalic fetus may be presumed to be a face presentation.

Intrapartum diagnosis

On abdominal palpation

Face presentation may not be detected, especially if the mentum is anterior. The occiput feels prominent, with a groove between head and back, but it may be mistaken for the sinciput. The limbs may be palpated on the side opposite to the occiput and the fetal heart is best heard through the fetal chest on the same side as the limbs. In a mentoposterior position the fetal heart is difficult to hear because the fetal chest is in contact with the maternal spine (Fig. 31.24).

On vaginal examination

The presenting part is high, soft and irregular. When the cervix is sufficiently dilated, the orbital ridges, eyes, nose and mouth may be felt. Confusion between the mouth and anus could arise, however. The mouth may be open, and the hard gums are diagnostic. The fetus may suck the examining finger. As labour progresses the face becomes oedematous, making it more difficult to distinguish from a breech presentation. To determine position the mentum must be located; if it is posterior, the midwife should decide whether it is lower than the sinciput; if so, it will rotate forwards if it can advance. In a left mentoanterior position, the orbital ridges will be in the left oblique diameter of the pelvis (Fig. 31.25). Care must be taken not to injure or infect the eyes with the examining finger.

Figure 31.25 Vaginal touch pictures of left mentoanterior position: (A) The mentum is felt to left and anteriorly. Orbital ridges in left oblique diameter of the pelvis. (B) Following increased extension of the head, the mouth can be felt. (C) The face has rotated  of a circle forwards. Orbital ridges in transverse diameter of the pelvis. Position direct mentoanterior.

of a circle forwards. Orbital ridges in transverse diameter of the pelvis. Position direct mentoanterior.

Mechanism of a left mentoanterior position

Figure 31.26 Diameters involved in delivery of face presentation. Engaging diameter, sub-mentobregmatic (SMB) 9.5 cm. The sub-mentovertical (SMV) diameter, 11.5 cm, sweeps the perineum.

Internal rotation of the head

This occurs when the chin reaches the pelvic floor and rotates forwards  of a circle. The chin escapes under the symphysis pubis (Fig. 31.27A).

of a circle. The chin escapes under the symphysis pubis (Fig. 31.27A).

Flexion

This takes place and the sinciput, vertex and occiput sweep the perineum; the head is born (Fig. 31.27B).

Internal rotation of the shoulders

The shoulders enter the pelvis in the left oblique diameter and the anterior shoulder reaches the pelvic floor first and rotates forwards  of a circle along the right side of the pelvis.

of a circle along the right side of the pelvis.

Possible course and outcomes of labour

The mother should be kept informed of her progress and any proposed intervention throughout labour.

Prolonged labour

Labour is often prolonged because the face is an ill-fitting presenting part and does not therefore stimulate effective uterine contractions. In addition the facial bones do not mould and, in order to enable the mentum to reach the pelvic floor and rotate forwards, the shoulders must enter the pelvic cavity at the same time as the head. The fetal axis pressure is directed to the chin and the head is extended almost at right angles to the spine, increasing the diameters to be accommodated in the pelvis.

Mentoanterior positions

With good uterine contractions, descent and rotation of the head occur (see above) and labour progresses to a spontaneous birth.

Mentoposterior positions

If the head is completely extended, so that the mentum reaches the pelvic floor first, and the contractions are effective, the mentum will rotate forwards and the position becomes anterior.

Persistent mentoposterior position

In this case, the head is incompletely extended and the sinciput reaches the pelvic floor first and rotates forwards  of a circle, which brings the chin into the hollow of the sacrum (Fig. 31.28). There is no further mechanism. The face becomes impacted because, in order to descend further, both head and chest would have to be accommodated in the pelvis. Whatever emerges anteriorly from the vagina must pivot around the subpubic arch; if the chin is posterior this is impossible because the head can extend no further.

of a circle, which brings the chin into the hollow of the sacrum (Fig. 31.28). There is no further mechanism. The face becomes impacted because, in order to descend further, both head and chest would have to be accommodated in the pelvis. Whatever emerges anteriorly from the vagina must pivot around the subpubic arch; if the chin is posterior this is impossible because the head can extend no further.

Reversal of face presentation

A face presentation in a persistent mentoposterior position may, in some cases, be manipulated to an occipitoanterior position using bimanual pressure (Gimovsky & Hennigan 1995, Neuman et al 1994). This method was developed to reduce the likelihood of an operative delivery for those women who refused caesarean section. Using a tocolytic drug to relax the uterus, the fetal head is disengaged using upward transvaginal pressure. The fetal head is then flexed with bimanual pressure under ultrasound guidance to achieve an occipitoanterior position.

Management of labour

First stage

Upon diagnosis of a face presentation, the midwife should inform the doctor of this deviation from the normal. Routine observations of maternal and fetal conditions are made as in a normal labour (see Ch. 26). A fetal scalp electrode must not be applied, and care should be taken not to infect or injure the eyes during vaginal examinations.

Immediately following rupture of the membranes, a vaginal examination should be performed to exclude cord prolapse; such an occurrence is more likely because the face is an ill-fitting presenting part. Descent of the head should be observed abdominally, and careful vaginal examination performed every 2–4 hrs to assess cervical dilatation and descent of the head.

In mentoposterior positions the midwife should note whether the mentum is lower than the sinciput, since rotation and descent depend on this. If the head remains high in spite of good contractions, caesarean section is likely. The woman may be prescribed oral ranitidine, 150 mg every 6 hrs throughout labour, if it is considered that an anaesthetic may be necessary.

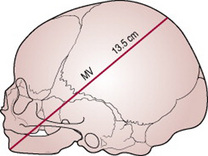

Birth of the head (Fig. 31.29)

When the face appears at the vulva, extension must be maintained by holding back the sinciput and permitting the mentum to escape under the symphysis pubis before the occiput is allowed to sweep the perineum. In this way, the submentovertical diameter (11.5 cm) instead of the mentovertical diameter (13.5 cm) distends the vaginal orifice. Because the perineum is also distended by the biparietal diameter (9.5 cm), an elective episiotomy may be performed to avoid extensive perineal lacerations.

Figure 31.29 Birth of face presentation: (A) The sinciput is held back to increase extension until the chin is born. (B) The chin is born. (C) Flexing the head to bring the occiput over the perineum. (D) Flexion is completed; the head is born.

If the head does not descend in the second stage, the doctor should be informed. In a mentoanterior position it may be possible for the obstetrician to deliver the baby with forceps when rotation is incomplete. If the position remains mentoposterior, the head has become impacted, or there is any suspicion of disproportion, a caesarean section will be necessary.

Complications

Obstructed labour

Because the face, unlike the vertex, does not mould, a minor degree of pelvic contraction may result in obstructed labour (see Ch. 30). In a persistent mentoposterior position the face becomes impacted and caesarean section is necessary.

Cord prolapse

A prolapsed cord is more common when the membranes rupture because the face is an ill-fitting presenting part. The midwife should always perform a vaginal examination when the membranes rupture to rule out cord prolapse (see Ch. 33).

Facial bruising

The baby’s face is always bruised and swollen at birth with oedematous eyelids and lips. The head is elongated (Fig. 31.30) and the baby will initially lie with head extended. The midwife should warn the parents in advance of the baby’s ‘battered’ appearance, reassuring them that this is only temporary; the oedema will disappear within 1 or 2 days, and the bruising will usually resolve within a week.

Cerebral haemorrhage

The lack of moulding of the facial bones can lead to intracranial haemorrhage caused by excessive compression of the fetal skull or by rearward compression, in the typical moulding of the fetal skull found in this presentation (Fig. 31.30).

Maternal trauma

Extensive perineal lacerations may occur at birth owing to the large submentovertical and biparietal diameters distending the vagina and perineum. There is an increased incidence of operative delivery, either forceps delivery or caesarean section, both of which increase maternal morbidity.

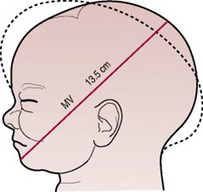

Brow presentation

In the brow presentation the fetal head is partially extended with the frontal bone, which is bounded by the anterior fontanelle and the orbital ridges, lying at the pelvic brim (Fig. 31.31). The presenting diameter of 13.5 cm is the mentovertical (Fig. 31.32), which exceeds all diameters in an average-sized pelvis. This presentation is rare, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 1000 deliveries (Bhal et al 1998).

Causes

These are the same as for a secondary face presentation (see above); during the process of extension from a vertex presentation to a face presentation, the brow will present temporarily and in a few cases this will persist.

Diagnosis

Brow presentation is not usually detected before the onset of labour.

On abdominal palpation

The head is high, appears unduly large and does not descend into the pelvis despite good uterine contractions.

On vaginal examination

The presenting part is high and may be difficult to reach. The anterior fontanelle may be felt on one side of the pelvis and the orbital ridges, and possibly the root of the nose, at the other (Fig. 31.33). A large caput succedaneum may mask these landmarks if the woman has been in labour for some hours.

Management

The doctor must be informed immediately this presentation is suspected. This is because vaginal birth is extremely rare and obstructed labour usually results. It is possible that a woman with a large pelvis and a small baby may give birth vaginally. When the brow reaches the pelvic floor the maxilla rotates forwards and the head is born by a mechanism somewhat similar to that of a persistent occipitoposterior position. However, the midwife should never expect such a favourable outcome. The mother should be warned about the possible course of labour and that a vaginal birth is unlikely.

If there is no evidence of fetal compromise, the doctor may allow labour to continue for a short while in case further extension of the head converts the brow presentation to a face presentation. Occasionally spontaneous flexion may occur, resulting in a vertex presentation. If the head fails to descend and the brow presentation persists, a caesarean section is performed, with maternal consent.

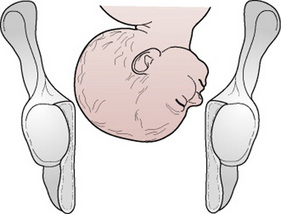

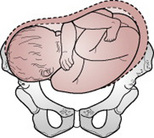

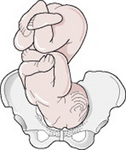

Breech presentation

A breech presentation is an unusual presentation but it should not be considered abnormal as the fetus lies longitudinally with the buttocks in the lower pole of the uterus. The presenting diameter is the bitrochanteric (10 cm) and the denominator the sacrum. This presentation occurs in approximately 3% of pregnancies at term. In mid-trimester the frequency is much higher because the greater proportion of amniotic fluid facilitates free movement of the fetus (Gimovsky & Hennigan 1995). Mothers can be reassured that a normal labour and birth are not excluded just because the presenting part is a breech. Ensuring informed consent the midwife must explain that not all breech babies can or should be born vaginally. The Term Breech Trial (Hannah et al 2000) reported that vaginal birth is more hazardous than caesarean birth for a uncomplicated term breech presentation. However, a 2-year follow-up has shown that there is little difference between outcome comparing mode of delivery (Hannah et al 2004).

Types of breech presentation and position

There are six positions for a breech presentation, illustrated in Figures 31.34-31.39.

Breech with extended legs (frank breech)

The breech presents with the hips flexed and legs extended on the abdomen (Fig. 31.40). Some 70% of breech presentations are of this type and it is particularly common in primigravidae whose good uterine muscle tone inhibits flexion of the legs and free turning of the fetus.

Complete breech

The fetal attitude is one of complete flexion (Fig. 31.41), with hips and knees both flexed and the feet tucked in beside the buttocks.

Footling breech

This is rare. One or both feet present because neither hips nor knees are fully flexed (Fig. 31.42). The feet are lower than the buttocks, which distinguishes it from the complete breech.

Knee presentation

This is very rare. One or both hips are extended, with the knees flexed (Fig. 31.43).

Causes

Often no cause is identified, but the following circumstances favour breech presentation.

Extended legs

Spontaneous cephalic version may be inhibited if the fetus lies with the legs extended, ‘splinting’ the back.

Preterm labour

As breech presentation is relatively common before 34 weeks’ gestation, it follows that breech presentation is more common in preterm labours.

Multiple pregnancy

Multiple pregnancy limits the space available for each fetus to turn, which may result in one or more fetuses presenting by the breech.

Polyhydramnios

Distension of the uterine cavity by excessive amounts of amniotic fluid may cause the fetus to present by the breech.

Antenatal diagnosis

Abdominal examination

Listen to the mother

She may tell you that she can feel that there is something very hard and uncomfortable under her ribs that makes breathing uncomfortable at times. If her baby’s feet are in the lower pole of the uterus she may feel some very hard kicks on her bladder.

Palpation

In primigravidae, diagnosis is more difficult because of their firm abdominal muscles. On palpation the lie is longitudinal with a soft presentation, which is more easily felt using Pawlik’s grip (see Fig. 17.7, p 278). The head can usually be felt in the fundus as a round hard mass, which may be made to move independently of the back by balloting it with one or both hands. If the legs are extended, the feet may prevent such nodding. When the breech is anterior and the fetus well flexed, it may be difficult to locate the head but use of the combined grip in which the upper and lower poles are grasped simultaneously may aid diagnosis. The woman may complain of discomfort under her ribs, especially at night, owing to pressure of the head on the diaphragm.

Diagnosis during labour

A previously unsuspected breech presentation may not be diagnosed until the woman is in established labour. If the legs are extended, the breech may feel like a head abdominally, and also on vaginal examination if the cervix is <3 cm dilated and the breech is high.

Vaginal examination

The breech feels soft and irregular with no sutures palpable, although occasionally the sacrum may be mistaken for a hard head and the buttocks mistaken for caput succedaneum. The anus may be felt and fresh meconium on the examining finger is usually diagnostic. If the legs are extended (Fig. 31.44) the external genitalia are very evident but it must be remembered that these become oedematous. An oedematous vulva may be mistaken for a scrotum.

If a foot is felt (Fig. 31.45), the midwife should differentiate it from the hand. Toes are all the same length, they are shorter than fingers and the big toe cannot be opposed to other toes. The foot is at right angles to the leg, and the heel has no equivalent in the hand.

Antenatal management

If the midwife suspects or detects a breech presentation at 36 weeks’ gestation or later, she should refer the woman to a doctor. The presentation may be confirmed by ultrasound scan or occasionally by abdominal X-ray. There are differing opinions amongst obstetricians as to the management of breech presentation during pregnancy and a decision on management is usually deferred until near term.

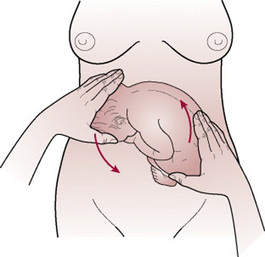

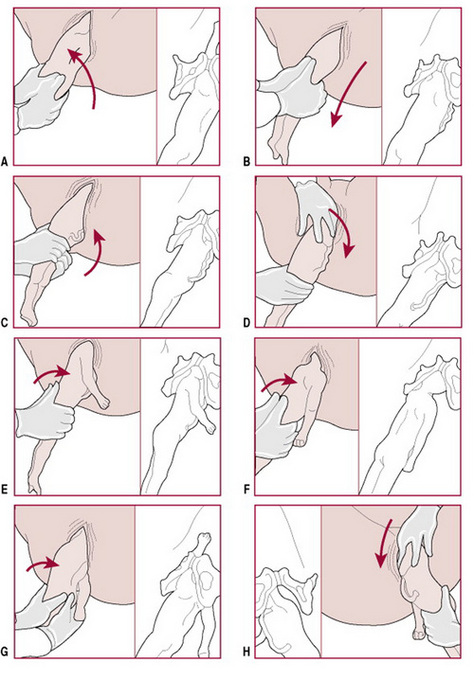

External cephalic version

External cephalic version (ECV) is the use of external manipulation on the mother’s abdomen to convert a breech to a cephalic presentation. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG 1993) recommend that ECV should be offered at term by a practitioner skilled and experienced in the procedure and should be undertaken only in a unit where there are facilities for emergency delivery (CESDI 2000). The success of the procedure depends not only upon the skill and experience of the operator, but also upon the position and engagement of the fetus, liquor volume and maternal parity (Hofmeyr & Hutton 2006).

It has been demonstrated that ECV can reduce the number of babies presenting by the breech at term by two-thirds, and therefore reduce the caesarean section rate for breech presentations (Hofmeyr & Hutton 2006).

According to Zhang et al (1993) turning the fetus from a breech to a cephalic presentation before 37 weeks’ gestation does not reduce the incidence of breech birth or rate of caesarean section as it is likely to turn itself back spontaneously but research is in progress (at the time of writing) to test this out. The reasons for attempting ECV and the procedure itself should be explained to the woman so that she can give her informed consent to have ECV performed.

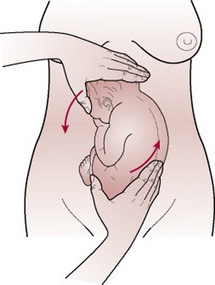

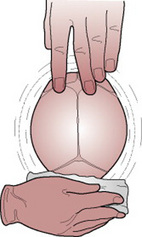

Method

An ultrasound scan is performed to localize the placenta and to confirm the position and presentation of the fetus.

If the procedure is to be performed under tocolysis then a cannula will be sited to allow venous access. A 30 min CTG is performed to establish that the fetus is not compromised at the start of the procedure and maternal blood pressure and pulse are recorded.

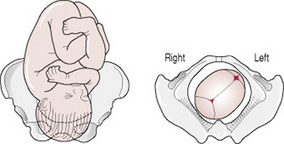

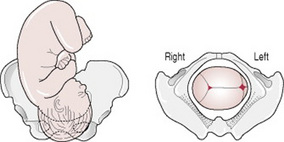

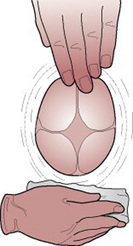

The woman is asked to empty her bladder. The midwife then assists the woman into a comfortable supine position. The foot of the bed may be elevated to help free the breech from the pelvic brim. The abdomen is usually dusted with talcum powder to prevent pinching of the mother’s skin during the procedure. While ECV may be uncomfortable for the mother it should not be painful. The breech is displaced from the pelvic brim towards an iliac fossa. Simultaneous force is then used as with one hand on each pole the operator makes the fetus perform a forward somersault (Figs 31.46-31.48). If this is not successful then a backward somersault can be attempted. If the fetus does not turn easily, then the procedure is abandoned but may be tried again a few days later.

Figures 31.46–31.48 External cephalic version.

Figure 31.46 The right hand lifts the breech out of the pelvis. The left hand makes the head follow the nose. Flexion of head and back is maintained throughout.

A CTG is repeated following the procedure.

If the woman is Rhesus negative an injection of anti-D immunoglobulin is given as prophylaxis against isoimmunization caused by any placental separation.

If the version is performed immediately prior to the onset of labour, this can be delayed until after birth when the blood group of the baby is known. In this case if anti-D is needed, it must be given within 72 hrs of the version.

Complications

Knotting of the umbilical cord

This should be suspected if bradycardia occurs and persists. The fetus is immediately turned back to a breech presentation. The woman is admitted for observation and, if necessary, caesarean section.

Separation of the placenta

The midwife should ask the woman to report pain or vaginal bleeding during and after the procedure.

Rupture of the membranes

If this occurs the cord may prolapse because neither the head nor the breech is engaged.

Relative contraindications

The presence of a uterine scar was previously thought to be an absolute contraindication to performing an ECV. Evidence, however, suggests that it is a safe and effective procedure used selectively in those women who have previously had a caesarean section (Flamm et al 1991).

Contraindications

Moxibustion for treatment of breech

Moxibustion (see Ch. 50) may be beneficial in reducing the need for ECV. However, there is a need for well-designed randomized controlled trials to evaluate moxibustion for breech presentation which should report on clinically relevant outcomes as well as the safety of the intervention (Cardini et al 2005, Neri et al 2004).

Persistent breech presentation

When external version has been unsuccessful or has not been attempted, then at 37 weeks’ gestation a discussion of the available options should take place between the mother and an experienced practitioner (CESDI 2000) and a decision made as to whether to perform an elective caesarean section or to attempt a vaginal birth. The discussion and the plan formulated should be recorded. A planned caesarean section at term reduces the perinatal and neonatal mortality and morbidity but there is an increased risk of maternal morbidity (Hannah et al 2004). A 2-year follow-up did not show any differences in long-term outcomes between planned caesarean or planned vaginal breech births (Hannah et al 2004). ‘An increased effort should be made to diagnose presentation at 37 weeks for all women planning to deliver outside an obstetric unit’ (CESDI 2000, p 37).

Assessment for vaginal birth

Any doubt as to the capacity of the pelvis to accommodate the fetal head must be resolved before the buttocks are born and the head attempts to enter the pelvic brim. At this point the fetus begins to be deprived of oxygen and a last minute decision to perform caesarean section may be too late.

Fetal size

This, especially in relation to maternal size, can be assessed on abdominal palpation but is more accurately judged in association with an ultrasound examination.

Pelvic capacity

This can be judged on vaginal assessment (see Ch. 17), but it is usual to perform a lateral pelvimetry. This will show the shape of the sacrum and give accurate measurements of the anteroposterior diameters of the pelvic brim, cavity and outlet. No studies have confirmed the value of this procedure in selecting women who are likely to succeed in achieving a vaginal birth of a breech or in improving perinatal outcome (Hannah 1994). In a multigravida, information about the type of birth and the size of previous babies when compared with the size of the present fetus can be helpful.

Mechanism of left sacroanterior position

Internal rotation of the buttocks

The anterior buttock reaches the pelvic floor first and rotates forwards  of a circle along the right side of the pelvis to lie underneath the symphysis pubis. The bitrochanteric diameter is now in the anteroposterior diameter of the outlet.

of a circle along the right side of the pelvis to lie underneath the symphysis pubis. The bitrochanteric diameter is now in the anteroposterior diameter of the outlet.

Lateral flexion of the body

The anterior buttock escapes under the symphysis pubis, the posterior buttock sweeps the perineum and the buttocks are born by a movement of lateral flexion.

Internal rotation of the shoulders

The shoulders enter the pelvis in the same oblique diameter as the buttocks, the left oblique. The anterior shoulder rotates forwards  of a circle along the right side of the pelvis and escapes under the symphysis pubis; the posterior shoulder sweeps the perineum and the shoulders are born.

of a circle along the right side of the pelvis and escapes under the symphysis pubis; the posterior shoulder sweeps the perineum and the shoulders are born.

Management of labour

Vaginal birth should be presented to the woman as the norm for breech presentation (MIDIRS 2007) provided there are no complications or contraindications, and it should be made clear that there is a risk of delivery by caesarean section.

First stage

Basic care during this stage is the same as in normal labour (see Chs 25 and 26) encouraging upright positions a much as possible to aid descent of the presenting part. The breech with extended legs fits the cervix quite well, the complete breech is a less well-fitting presenting part and the membranes tend to rupture early. For this reason there is an increased risk of cord prolapse, and a vaginal examination is performed to exclude this as soon as the membranes rupture. If they do not rupture spontaneously at an early stage, it is considered safer to leave them intact until labour is well established and the breech is at the level of the ischial spines. Meconium-stained liquor is sometimes found owing to compression of the fetal abdomen and is not always a sign of fetal compromise.

Analgesia

An epidural block may be offered to a woman with a breech presentation as it inhibits the urge to push prematurely. However, there is no evidence to suggest that this is indicated. Epidural analgesia has been associated with prolongation of the second stage of labour and has not been associated with any unique advantages for a woman giving birth to a breech at term.

Second stage

Full dilatation of the cervix should always be confirmed by vaginal examination before the woman commences active pushing. This is because in a footling presentation a foot may appear at the vulva when the cervix is only partially dilated; or when the legs are extended, particularly if the fetus is small, the breech may slip through an incompletely dilated cervix. In either case, the head may be trapped by the cervix when the baby is partially born. The woman may like to adopt a supported squat to utilize gravity in the second stage.

If the birth is taking place in hospital it is usual to inform the obstetrician of the onset of the second stage; a paediatrician should be present for the birth and it is usual to inform the anaesthetist also in case a general anaesthetic is required. Active pushing is not commenced until the buttocks are distending the vulva. Failure of the breech to descend onto the perineum in the second stage despite good contractions may indicate a need for caesarean section.

Types of birth

Management of the birth

Breech births can be as normal as any other vaginal birth and a woman who has chosen to birth vaginally needs support from skilled and confident midwives. An explanation is given to the woman so that she can understand the importance of not pushing until full dilatation of her cervix has been confirmed. The midwife should also discuss with the woman beforehand the possibility of the need for other skilled attendants at the birth.

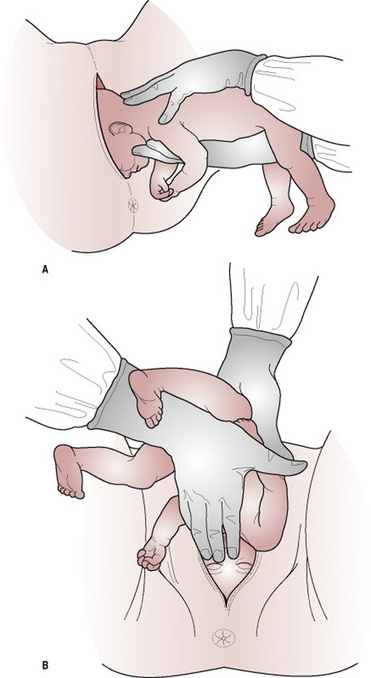

The woman is encouraged to push with the contractions and the buttocks are born spontaneously. If the legs are flexed, the feet disengage at the vulva and the baby is born as far as the umbilicus. A loop of cord is gently pulled down to avoid traction on the umbilicus. Spasm of the cord vessels can be caused by manipulating the cord or by stretching it. If the cord is being nipped behind the pubic bone it should be moved to one side. The midwife should feel for the elbows, which are usually on the chest. If so, the arms will escape with the next contraction. If the arms are not felt, they are extended.

If an obstetrician is assisting the birth the woman may be placed in the lithotomy position when the buttocks are distending the perineum, and the vulva swabbed and draped with sterile towels. The bladder must be empty and it is usually catheterized at this stage. If epidural analgesia is not being used, the perineum is infiltrated with up to 10 mL of 0.5% plain lignocaine prior to an episiotomy being performed. (Pudendal block is sometimes used by a doctor.)

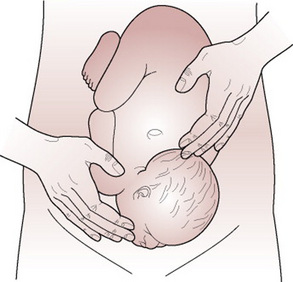

Birth of the shoulders

The uterine contractions and the weight of the body will bring the shoulders down on to the pelvic floor where they will rotate into the anteroposterior diameter of the outlet.

It is helpful to wrap a small towel around the baby’s hips, which preserves warmth and improves the grip on the slippery skin. The midwife now grasps the baby by the iliac crests with her thumbs held parallel over his sacrum and tilts the baby towards the maternal sacrum in order to free the anterior shoulder.

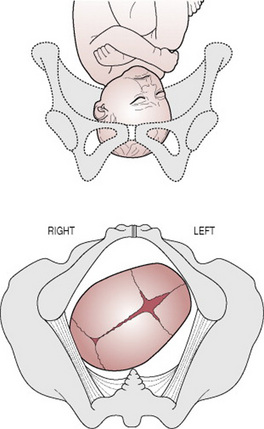

When the anterior shoulder has escaped, the buttocks are lifted towards the mother’s abdomen to enable the posterior shoulder and arm to pass over the perineum (Fig. 31.49). As the shoulders are born, the head enters the pelvic brim and descends through the pelvis with the sagittal suture in the transverse diameter. The back must remain lateral until this has happened but will afterwards be turned uppermost. If the back is turned upwards too soon, the anteroposterior diameter of the head will enter the anteroposterior diameter of the brim and may become extended. The shoulders may then become impacted at the outlet and the extended head may cause difficulty.

Birth of the head

When the back has been turned the infant is allowed to hang from the vulva without support. The baby’s weight brings the head onto the pelvic floor on which the occiput rotates forwards. The sagittal suture is now in the anteroposterior diameter of the outlet. If rotation of the head fails to take place, two fingers should be placed on the malar bones and the head rotated. The baby can be allowed to hang for 1 or 2 min. Gradually the neck elongates, the hair-line appears and the suboccipital region can be felt. Controlled birth of the head is vital to avoid any sudden change in intracranial pressure and subsequent cerebral haemorrhage. There are three methods used.

Forceps delivery. Most breech deliveries are performed by an obstetrician, who will apply forceps to the after-coming head to achieve a controlled birth.

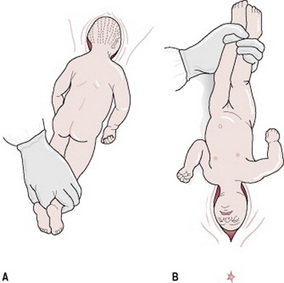

Burns Marshall method can be undertaken once the nape of the neck and hairline are visible. The midwife or doctor stands facing away from the mother and, with the left hand, grasps the baby’s ankles from behind with forefinger between the two (Fig. 31.50A). The baby is kept on the stretch with sufficient traction to prevent the neck from bending backwards and being fractured. The suboccipital region, and not the neck, should pivot under the apex of the pubic arch or the spinal cord may be crushed. The feet are taken up through an arc of 180° until the mouth and nose are free at the vulva. The right hand may guard the perineum in order to prevent sudden escape of the head. An assistant may now clear the airway and the baby will breathe. The mother should be asked to take deliberate, regular breaths which allow the vault of the skull to escape gradually, taking 2 or 3 min (Fig. 31.50B).

Figure 31.50 Burns Marshall method of delivering the after-coming head of a breech presentation: (A) The baby is grasped by the feet and held on the stretch. (B) The mouth and nose are free. The vault of the head is delivered slowly.

Mauriceau–Smellie–Veit manoeuvre (jaw flexion and shoulder traction; Fig. 31.51). This is mainly used when there is delay in descent of the head because of extension.

Figure 31.51 Mauriceau–Smellie–Veit manoeuvre for delivering the after-coming head of breech presentation: (A) The hands are in position before the body is lifted. (B) Extraction of the head.

The baby is laid astride the arm with the palm supporting the chest (Fig. 31.51A). One finger is placed on each malar or cheek bone to flex the head. The middle finger may be used to apply pressure to the chin. Two fingers of the operator’s other hand are hooked over the shoulders with the middle finger pushing up the occiput to aid flexion. Suprapubic pressure applied by an assistant may be helpful at this point to increase flexion. Traction is applied to draw the head out of the vagina and, when the suboccipital region appears, the body is lifted to assist the head to pivot around the symphysis pubis (Fig. 31.51B). The speed of birth of the head must be controlled so that it does not emerge suddenly like a cork popping out of a bottle. Once the face is free, the airways may be cleared and the vault is delivered slowly.

Alternative positions

When the woman has chosen to deliver in an alternative position, it is the upright or supported squat that is the most suitable. The techniques described above will be adapted accordingly and the midwife will observe and encourage the spontaneous mechanism of birth.

Delivery of extended legs

The frank breech descends more rapidly during the first stage of labour. The cervix dilates more quickly and there is a risk of the cord becoming compressed between the legs and the body. Cord prolapse is less likely than in other breech presentations because the frank breech is a better-fitting presenting part. Delay may occur at the outlet because the legs splint the body and impede lateral flexion of the spine.

The baby can be born with legs extended but assistance is usually required. When the popliteal fossae appear at the vulva, two fingers are placed along the length of one thigh with the fingertips in the fossa. The leg is swept to the side of the abdomen (abducting the hip) and the knee is flexed by the pressure on its under surface. As this movement is continued the lower part of the leg will emerge from the vagina (Fig. 31.52). This process should be repeated in order to deliver the second leg. The knee is a hinge joint, which bends in one direction only. If the knee is pulled forwards from the abdomen, severe injury to the joint can result.

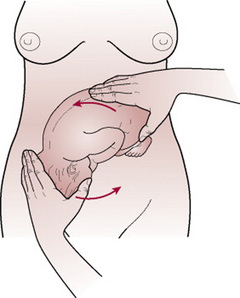

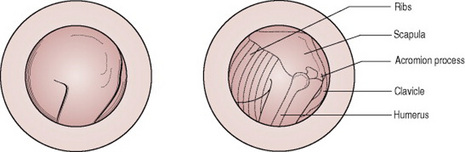

Delivery of extended arms

Extended arms are diagnosed when the elbows are not felt on the chest after the umbilicus is born. Prompt action must be taken to avoid delay and consequent hypoxia. This may be dealt with by using the Løvset manoeuvre (Figs 31.53, 31.54). This is a combination of rotation and downward traction that may be employed to deliver the arms whatever position they are in. The direction of rotation must always bring the back uppermost and the arms are delivered from under the pubic arch.

When the umbilicus is born and the shoulders are in the anteroposterior diameter, the baby is grasped by the iliac crests with the thumbs over the sacrum. Downward traction is applied until the axilla is visible.

Maintaining downward traction throughout, the body is rotated through half a circle, 180°, starting by turning the back uppermost. The friction of the posterior arm against the pubic bone as the shoulder becomes anterior sweeps the arm in front of the face. The movement allows the shoulders to enter the pelvis in the transverse diameter.

The arm which is now anterior is delivered. The first two fingers of the hand that is on the same side as the baby’s back are used to splint the humerus and draw it down over the chest as the elbow is flexed.

The body is now rotated back in the opposite direction and the second arm delivered in a similar fashion.

Delay in birth of the head

Extended head. If, when the body has been allowed to hang, the neck and hair-line are not visible, it is probable that the head is extended. This may be dealt with by the use of forceps or the Mauriceau–Smellie–Veit manoeuvre. If the head is trapped in an incompletely dilated cervix, an air channel can be created to enable the baby to breathe pending intervention. This is done by inserting two fingers or a Sim’s speculum in front of the baby’s face and holding the vaginal wall away from the nose. Moisture is mopped away and the airways are cleared. Attempts to release the head from the cervix result in high fetal morbidity and mortality. The McRoberts manoeuvre has been suggested as a method to facilitate the release of the fetal head (Shushan & Younis 1992). The McRoberts manoeuvre requires the woman to lie flat on her back and bring her knees up to her abdomen with hips abducted. This manoeuvre, more commonly used to relieve shoulder dystocia, is described in detail in Ch. 33.

Posterior rotation of the occiput. This malrotation of the head is rare and is usually the result of mismanagement, for the back should be turned upwards after the shoulders are born.

To assist birth of the head with the occiput posterior, the chin and face are permitted to escape under the symphysis pubis as far as the root of the nose and the baby is then lifted up towards the mother’s abdomen to allow the occiput to sweep the perineum.

Complications

Apart from those difficulties already mentioned, other complications can arise, most of which affect the fetus. Many of these can be avoided by allowing only an experienced operator, or a closely supervised learner, to assist the birth.

Impacted breech

Labour becomes obstructed when the fetus is disproportionately large for the size of the maternal pelvis.

Cord prolapse

This is more common in a flexed or footling breech, as these have ill-fitting presenting parts (see Ch. 33).

Birth injury

Superficial tissue damage

The midwife must warn the mother and her partner of the bruising that may be expected during birth. Oedema and bruising of the baby’s genitalia may be caused by pressure on the cervix. In a footling breech a prolapsed foot that lies in the vagina or at the vulva for a long time may become very oedematous and discoloured.

If assisting the birth is performed correctly the following are less likely to occur:

Fractures of humerus, clavicle or femur or dislocation of shoulder or hip

These can be caused during manipulation of extended arms or legs.

Erb’s palsy

This can be caused when the brachial plexus is damaged. The brachial plexus can be damaged by twisting the baby’s neck (see Plate 31).

Damage to the adrenals

This can be caused by grasping the baby’s abdomen, leading to shock caused by adrenaline release.

Fetal hypoxia

This may be due to cord prolapse or cord compression or to premature separation of the placenta.

Premature separation of the placenta

Considerable retraction of the uterus takes place while the head is still in the vagina and the placenta begins to separate. Excessive delay in birth of the head may cause severe hypoxia in the fetus.

Maternal trauma

The maternal complications of a breech delivery are the same as found in other operative vaginal deliveries (see Ch. 32).

Shoulder presentation

When the fetus lies with its long axis across the long axis of the uterus (transverse lie) the shoulder is most likely to present. Occasionally the lie is oblique but this does not persist as the uterine contractions during labour make it longitudinal or transverse.

Shoulder presentation occurs in approximately 1:300 pregnancies near term. Only 17% of these cases remain as a transverse lie at the onset of labour; the majority are multigravidae (Gimovsky & Hennigan 1995). The head lies on one side of the abdomen, with the breech at a slightly higher level on the other. The fetal back may be anterior or posterior (Figs 31.55, 31.56).

Causes

Maternal

Before term, transverse or oblique lie may be transitory, related to maternal position or displacement of the presenting part by an overextended bladder prior to ultrasound examination. Other causes are described below.

Lax abdominal and uterine muscles

This is the most common cause and is found in multigravidae, particularly those of high parity.

Fetal

Pre-term pregnancy

The amount of amniotic fluid in relation to the fetus is greater, allowing the fetus more mobility than at term.

Multiple pregnancy

There is a possibility of polyhydramnios but the presence of more than one fetus reduces the room for manoeuvre when amounts of liquor are normal. It is the second twin that more commonly adopts this lie after birth of the first baby.

Polyhydramnios

The distended uterus is globular and the fetus can move freely in the excessive liquor.

Antenatal diagnosis

Intrapartum diagnosis

On abdominal palpation

The findings are as above but when the membranes have ruptured the irregular outline of the uterus is more marked. If the uterus is contracting strongly and becomes moulded around the fetus, palpation is very difficult. The pelvis is no longer empty, the shoulder being wedged into it.

On vaginal examination

This should not be performed without first excluding placenta praevia. In early labour, the presenting part may not be felt. The membranes usually rupture early because of the ill-fitting presenting part, with a high risk of cord prolapse.

If the labour has been in progress for some time the shoulder may be felt as a soft irregular mass. It is sometimes possible to palpate the ribs, their characteristic grid-iron pattern being diagnostic (Fig. 31.57). When the shoulder enters the pelvic brim an arm may prolapse; this should be differentiated from a leg. The hand is not at right angles to the arm, the fingers are longer than toes and of unequal length and the thumb can be opposed. No os calcis can be felt and the palm is shorter than the sole. If the arm is flexed, an elbow feels sharper than a knee.

Possible outcome

There is no mechanism for delivery of a shoulder presentation. If this persists in labour, delivery must be by caesarean section to avoid obstructed labour and subsequent uterine rupture (see Ch. 33).

Whenever the midwife detects a transverse lie she must obtain medical assistance.

Management

Antenatal

A cause must be sought before deciding on a course of management. Ultrasound examination can detect placenta praevia or uterine abnormalities, while X-ray pelvimetry will demonstrate a contracted pelvis (see Ch. 8). Any of these causes requires elective caesarean section. Once they have been excluded, ECV may be attempted. If this fails, or if the lie is again transverse at the next antenatal visit, the woman is admitted to hospital while further investigations into the cause are made. She frequently remains there until labour because of the risk of cord prolapse if the membranes rupture.

Intrapartum

If a transverse lie is detected in early labour while the membranes are still intact, the doctor may attempt an ECV, followed, if this is successful, by a controlled rupture of the membranes. (This may be considered before labour in some cases (Hofmeyr & Hutton 2006). If the membranes have already ruptured spontaneously, a vaginal examination must be performed immediately to detect possible cord prolapse.

Complications

Prolapsed arm

This may occur when the membranes have ruptured and the shoulder has become impacted. Delivery should be by immediate caesarean section.

Neglected shoulder presentation

The shoulder becomes impacted, having been forced down and wedged into the pelvic brim. The membranes have ruptured spontaneously and if the arm has prolapsed it becomes blue and oedematous. The uterus goes into a state of tonic contraction, the overstretched lower segment is tender to touch and the fetal heartbeat may be absent. All the maternal signs of obstructed labour are present (see Ch. 30) and the outcome, if not treated in time, is a ruptured uterus and a stillbirth.

With adequate supervision both antenatally and during labour this should never occur.

Unstable lie

The lie is defined as unstable when after 36 weeks’ gestation, instead of remaining longitudinal, it varies from one examination to another between longitudinal and oblique or transverse.

Causes

Any condition in late pregnancy that increases the mobility of the fetus or prevents the head from entering the pelvic brim may cause this.

Management

Antenatal

It may be advisable for the woman to be admitted to hospital to avoid unsupervised onset of labour with a transverse lie. An alternative is for the woman to admit herself to the labour ward as soon as labour commences. The risk associated with the possibility of rupture of membranes and cord prolapse should be emphasized if the mother chooses to remain at home.

Ultrasonography is used to rule out placenta praevia. Attempts will be made to correct the abnormal presentation by ECV. If unsuccessful, caesarean section is considered.

Intrapartum

Many obstetricians induce labour after 38 weeks’ gestation, having first ensured that the lie is longitudinal; the induction may be performed by commencing an intravenous infusion of oxytocin to stimulate contractions. A controlled rupture of the membranes is performed so that the head enters the pelvis.

The midwife should ensure that the woman has an empty rectum and bladder before the procedure, as a loaded rectum or full bladder can prevent the presenting part from entering the pelvis. She should palpate the abdomen at frequent intervals to ensure that the lie remains longitudinal and to assess the descent of the head. Labour is regarded as a trial (see Ch. 30).

Compound presentation

When a hand, or occasionally a foot, lies alongside the head, the presentation is said to be compound. This tends to occur with a small fetus or roomy pelvis and seldom is difficulty encountered except in cases where it is associated with a flat pelvis. On rare occasions the head, hand and foot are felt in the vagina – a serious situation that may occur with a dead fetus.

If diagnosed during the first stage of labour, medical aid must be sought. If, during the second stage, the midwife sees a hand presenting alongside the vertex, she could try to hold the hand back.

Bhal PS, Davies NJ, Chung T. A population study of face and brow presentation. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;18(3):231-235.

Cardini F, Lombardo P, Regalia AL. A randomised controlled trial of moxibustion for breech presentation. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;112(6):743-747.

CESDI (Confidential enquiry into stillbirths and deaths in infancy). 7th Annual Report. London: Maternal and Child Health Research Consortium, 2000.

El Halta. Preventing prolonged labour. Midwifery Today. 1998;46:22-27.

Flamm BL, Fried M, Lonky NM, et al. External cephalic version after previous cesarean section. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1991;165(2):370-372.

Gimovsky M, Hennigan C. Abnormal fetal presentations. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;7(6):482-485.

Hannah WJ. The Canadian consensus on breech management at term. Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada policy statement. Journal of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. 1994;16(6):1839-1848.

Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, et al. Term Breech Trial Collaborative group. Planned cesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomized multicentre trial. Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1375-1383.

Hannah ME, Whyte H, Hannah WJ. Maternal outcomes at 2 years after planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal delivery for breech presentation at term: the international randomized term breech trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;191(3):917-p927.

Hofmeyr GJ, Hutton EK. External cephalic version for breech presentation before term Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2006. Issue 1

Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R. Hands/knees posture in late pregnancy or labour for fetal malposition (lateral or posterior). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2005. Issue 2

Kariminia A, Chamberlain ME, Keogh J. Randomised controlled trial of effect of hands and knees posturing on incidence of occiput posterior position at birth. British Medical Journal. 2004;328(7438):490-493.

MIDIRS. Informed choice for professionals. Number 9 breech presentation – options for care. Bristol: MIDIRS and The NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2007.

Neri I, Airola G, Contu G. Acupuncture plus moxibustion to resolve breech presentation: a randomized controlled study. Journal of MaternalFetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2004;15(4):247-252.

Neuman M, Beller U, Lavie O. Intrapartum bimanual tocolytic-assisted reversal of face presentation: preliminary report. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;84(10):146-148.

Pearl ML, Roberts JM, Laros RK, et al. Vaginal delivery from the persistent occiput posterior position. Influence on maternal and neonatal morbidity. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 1993;38(12):955-961.

RCOG. (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists). In: Effective procedures in obstetrics suitable for audit. Manchester: Medical Audit Unit, RCOG; 1993:2.

Shushan A, Younis JS. McRoberts maneuver for the management of the aftercoming head in breech delivery. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 1992;34(3):188-189.

Sutton J. Birth: medical emergency or engineering miracle? A midwifery approach to keeping birth normal. MIDIRS Digest. 1996;6(2):170-173.

Thornton JG, Lilford RJ. Active management of labour: current knowledge and research issues. British Medical Journal. 1994;309(6951):366-369.

Zhang J, Bowes WA, Fortney JA. Efficacy of external cephalic version: a review. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;82(2):306-312.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Mode of term singleton breech delivery. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;108(1):235-237.

This publication suggests that planned vaginal birth of a term singleton breech fetus may be reasonable under hospital-specific protocol guidelines for both eligibility and labour management. It states that the patient’s informed consent should be documented.

Ben-Arie A, Kogan S, Schachter M. The impact of external cephalic version on the rate of vaginal and cesarean breech deliveries: a 3-year cumulative experience. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1995;63(2):125-129.

This paper remains relevant to current practice, an interesting European perspective on the experience of ECV and breech deliveries.

CESDI (Confidential enquiry into stillbirths and deaths in infancy). 7th Annual Report. London: Maternal and Child Health Research Consortium, 2000.

The 7th CESDI report focuses on breech presentation at the onset of labour. Recommendations for management of breech presentation and training of staff should be read in full.

Chapman K. Aetiology and management of the secondary brow. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;20(1):39-44.

Six cases of vaginal birth from a brow presentation over a career of 39 years are recorded in this article. Most midwives will never see a brow presentation birth vaginally; this is a fascinating record from a long career.

Gardberg M, Tuppurainen M. Anterior placental location predisposes for occiput posterior presentation near term. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1994;73(2):151-152.

In a series of 325 ultrasound examinations the authors demonstrated an association between an anteriorly situated placenta and OP position after 36 weeks of pregnancy.

Gardberg M, Laakkonen E, Salevaara M. Intrapartum sonography and persistent occiput posterior position: a study of 408 deliveries. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;91(5):1746-1749.

This study showed that in most cases occipitoposterior position develops through a malrotation and only one-third through absence of rotation from an initially occiput posterior position.

Hofmeyr GJ, Impey LWM. The management of breech presentation. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2006.

Updated comprehensive obstetric guidelines for the management of breech presentation covering: reducing of the incidence of breech presentation, including external cephalic version; elective caesarean section versus planned vaginal breech delivery at term, including intrapartum management and training needs; and management of the preterm breech and twin breech.

Nassar N, Roberts CL, Raynes-Greenow CH, et al. Development and pilot-testing of a decision aid for women with a breech-presenting baby. Midwifery. 2007;23(1):38-47.

This article highlights the importance of giving women sound information. The decision aid described was an effective and acceptable tool for pregnant women that provided an important adjunct to standard counselling for the management of breech presentation.

Waites B. Breech birth. London: Free Association Books, 2003.

A clearly written comprehensive guide suitable for professionals and pregnant women

of a circle forwards. Sagittal suture in the left oblique diameter of the pelvis. The position is right occipitoanterior.

of a circle forwards. Sagittal suture in the left oblique diameter of the pelvis. The position is right occipitoanterior.

of a circle forwards. Note the twist in the neck. Sagittal suture in the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis.

of a circle forwards. Note the twist in the neck. Sagittal suture in the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis. of a circle to the right.

of a circle to the right.

of a circle to the woman’s left.

of a circle to the woman’s left. of a circle to the left.

of a circle to the left.