Chapter 25 The first stage of labour

physiology and early care

The transition from pregnancy to labour is a sequence of events that often begins gradually. The first stage of labour, although difficult to diagnose, is usually recognized by the onset of regular uterine contractions and finally culminates in complete effacement and dilatation of the cervix.

Changes during the last few weeks of pregnancy

The physiological transition from being a pregnant woman to becoming a mother means an enormous change for each woman, both physically and psychologically. Every system in the body is affected and the experience, although unfortunately not joyous for all, represents a major transition in a woman’s life.

During the last few weeks of pregnancy, a number of physical and psychological changes may occur:

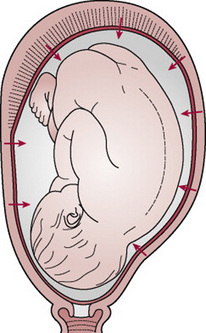

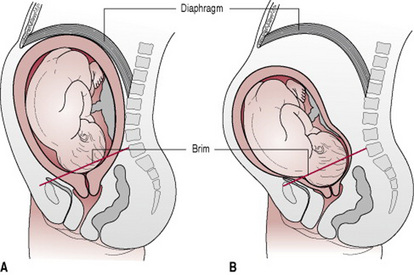

Figure 25.1 (A) Prior to lightening. The fundus crowds the diaphragm. The lower uterine segment has not stretched to accommodate the fetal head, which therefore remains high. The lower segment is ‘V’ shaped. (B) After lightening. The fundus sinks below the diaphragm and breathing is easier. The lower segment is ‘U’ shaped; it has softened and dilated so that the head sinks down into it and may partly enter the pelvic brim.

In a healthy pregnancy, the placenta nourishes and protects the growing fetus; the body of the uterus remains relaxed and the cervix closed. As birth approaches, the non-progressive Braxton Hicks contractions experienced during pregnancy alter and intensify to become the progressive form of labour. The cervix, which has remained firm and closed, becomes soft and able to dilate. Accompanying the physical changes the woman may have feelings of great intensity varying from excited anticipation to fearful expectancy. The midwife and other supporters must exercise great sensitivity at this time in order to meet the specific needs and hopes of the woman.

Labour, purely in the physical sense, may be described as the process by which the fetus, placenta and membranes are expelled through the birth canal – but of course, labour is much more than a purely physical event. What happens during labour can affect the relationship between mother and baby and can influence the likelihood of future pregnancies.

Traditionally, a human pregnancy is considered to last approximately 40 weeks (see Ch. 17). Normal labour occurs between 37 and 42 weeks’ gestation.

The World Health Organization (WHO 1997) defines normal labour as: low risk throughout, spontaneous in onset with the fetus presenting by the vertex, culminating in the mother and infant in good condition following birth. All definitions of labour appear to be purely physiological and do not encompass the psychological well-being of the parents.

Once physiological labour commences, its progress is measured by descent of the head and dilatation of the cervix. The expected rate of cervical dilatation in labour was based on work by Friedman during the 1950s, but more recent research demonstrates that the process of labour in terms of cervical dilatation should not be strictly timed and may last longer than some clinicians expect. The criteria for distinguishing normal labour from abnormal labour based on time limits needs revision (Albers 1999, Lavender et al 2006).

Traditionally, three stages of labour are described: the first, second and third stage. But this is a rather pedantic view, as labour is obviously a continuous process. There is increasing acknowledgement that there are not just three clear phases of normal labour. Sherblom Matteson (2001) gives a full description of this view of more than three stages to labour, along with not only the physical changes but the emotional effects observed in women at this time.

First stage

The onset of spontaneous physiological labour

Women should have adequate information prior to labour to ensure comprehension of the changes labour will bring. This information is also needed to allow women to make their own choices based on good unbiased evidence. The complex physical, psychological and emotional experience of labour affects every woman differently and midwives must have sound knowledge as well as a range of different experiences to ensure the woman has some control over the birth of her baby. Women in labour should be encouraged to trust their own instincts, listen to their own body and verbalize feelings in order to get the help and support they need. Anxiety can increase the production of adrenaline (epinephrine), which inhibits uterine activity and may in turn prolong labour (Niven 1992, Seitchik 1987, Wuitchik et al 1989). The attitude of the midwife and the advice and guidance she gives during pregnancy influence the progress of labour and the attitudes of both the partners to each other and to their baby after it is born (Fisher et al 2006, Halldorsdottir & Karlsdottir 1996, Nolan 1995).

Recognition of the onset of normal spontaneous labour is not always easy. A woman may construe herself to be labouring, whereas sound midwifery judgement and understanding of the physiology of the first stage of labour may lead the midwife to the diagnosis of the latent phase of labour. Both the woman and midwife being aware of the latent phase of labour and allowing this time to pass with no intervention may prevent the medical diagnosis of ‘poor progress’ or ‘failure to progress’ later in labour. In a hospital setting, it is good practice not to commence the partogram until active labour has commenced.

Spurious labour

Many women experience contractions before the onset of labour; these may be painful and may even be regular for a time, causing a woman to think that labour has started. The two features of true labour that are absent in spurious labour are effacement and dilatation of the cervix (see below). It is important to note that the discomfort or even pain that the woman is conscious of is not false; the contractions she is experiencing are real but have not yet settled into the rhythmic pattern of ‘true’ labour and are not having an effect on the cervix. Reassurance should be given; discussion of this potential situation earlier in the pregnancy will have allowed the woman and her partner to prepare for such a scenario.

Cervical effacement (taking up of the cervix)

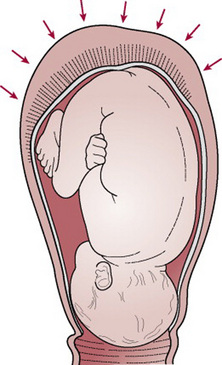

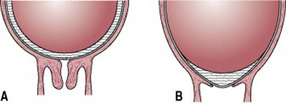

Here the cervix is drawn up and gradually merges into the lower uterine segment (Fig. 25.2). In the primiparous woman, this may result in complete effacement of the internal and external cervical os. But in the multiparous woman a perceptible canal may remain.

Figure 25.2 (A) The cervix before effacement. (B) The cervix after effacement. The cervical canal is now part of the lower uterine segment.

The onset of labour is determined by a complex interaction of maternal and fetal hormones and is not fully understood. It would appear to be multifactorial in origin, being a combination of hormonal and mechanical factors. Levels of maternal oestrogen rise sharply during the last weeks of pregnancy, resulting in changes that overcome the inhibiting effects of progesterone. High levels of oestrogens cause uterine muscle fibres to display oxytocic receptors and form gap junctions with each other. Oestrogen also stimulates the placenta to release prostaglandins that induce a production of enzymes that will digest collagen in the cervix, helping it to soften (Tortora & Grabowski 2000). The process is unclear but it is thought that both fetal and placental factors are involved. There is no clear evidence that concentrations of oestrogens and progesterone alter at the onset of labour, but the balance between them does facilitate myometrial activity.

Uterine activity may also result from mechanical stimulation of the uterus and cervix. This may be brought about by overstretching, as in the case of a multiple pregnancy, or pressure from a presenting part that is well applied to the cervix (Allman et al 1996, Beazley 1995).

The onset of labour is a process, not an event; therefore it is very difficult to pinpoint exactly when the painless (sometimes painful) contractions of pre-labour develop into the progressive rhythmic contractions of established labour.

Diagnosing the onset of labour is extremely important, since it is on the basis of this finding that decisions are made that will affect the management of labour (Gee & Olah 1993, Gharoro & Enabudoso 2006, O’Driscoll & Meagher 1993).

It is part of the remit of the midwife to ensure that women have sufficient information to assist them to recognize the onset of true labour. Contact with the midwife should be made when regular, rhythmic, uterine contractions are experienced, and these are perceived by the woman as uncomfortable or painful.

When in labour, contractions will often be accompanied or preceded by a bloodstained mucoid ‘show’. Occasionally, the membranes will rupture; a midwife may want to be assured that there are no changes in the fetal heart rate due to the rare complication of cord prolapse and that meconium is not present in the liquor.

Irrespective of whether they have given birth before, women experience their onset of labour in a variety of ways. A large proportion of these experiences bear no resemblance to the classic diagnosis of labour as described above and most are unrelated to the duration of labour (Gross et al 2006).

Physiology of the first stage of labour

Duration

The length of labour varies widely and is influenced by parity, birth interval, psychological state, presentation and position of the fetus. Maternal pelvic shape and size and the character of uterine contractions also affect timescale.

By far the greater part of labour is taken up by the first stage; it is common to expect the active phase (see First stage, above) to be completed within 6–12 hrs (Tortora & Grabowski 2000). Albers (1999) found the mean length of the active phase (4–10 cm dilated) was 7.7 hrs in first time mothers (but up to 17.5 hrs) and 5.6 hrs in multiparous women (again up to 13.8 hrs). On average, the nulliparous woman will take longer than the parous woman to reach the second stage. In the individual case, however, averages can prove extremely misleading: The World Health Organization recommends partograms with a 4 hrs action line, denoting the timing of intervention for prolonged labour; others recommend earlier intervention. In a randomized trial of primigravid women with uncomplicated pregnancies, in spontaneous labour at term, women were assigned to have their labours recorded on a partogram with an action line 2 or 4 hrs to the right of the alert line. Outcomes of rate of caesarean delivery and maternal satisfaction with labour, demonstrated no significant differences but intervention was less in the 4 hrs group (Lavender et al 2006).

Uterine action

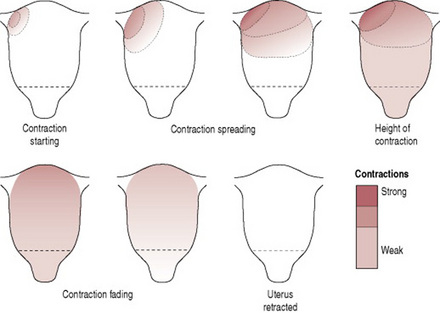

Fundal dominance (Fig. 25.3)

Each uterine contraction starts in the fundus near one of the cornua and spreads across and downwards. The contraction lasts longest in the fundus where it is also most intense, but the peak is reached simultaneously over the whole uterus and the contraction fades from all parts together. This pattern permits the cervix to dilate and the strongly contracting fundus to expel the fetus.

Polarity

Polarity is the term used to describe the neuromuscular harmony that prevails between the two poles or segments of the uterus throughout labour. During each uterine contraction, these two poles act harmoniously. The upper pole contracts strongly and retracts to expel the fetus; the lower pole contracts slightly and dilates to allow expulsion to take place. If polarity is disorganized then the progress of labour is inhibited.

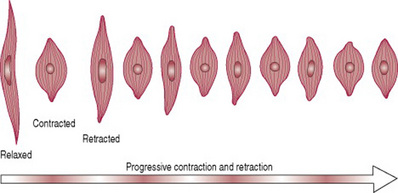

Contraction and retraction

Uterine muscle has a unique property. During labour the contraction does not pass off entirely, but muscle fibres retain some of the shortening of contraction instead of becoming completely relaxed (Fig. 25.4). This is termed retraction. It assists in the progressive expulsion of the fetus; the upper segment of the uterus becomes gradually shorter and thicker and its cavity diminishes.

Each labour is individual and does not always conform to expectations, but generally before labour becomes established, these uterine contractions may occur every 15–20 min and may last for about 30 sec. They are often fairly weak and may even be imperceptible to the mother. They usually occur with rhythmic regularity and the intervals between them gradually lessen; meanwhile the length and strength of the contractions gradually increase through the latent phase and into the active first stage. By the end of the first stage, they occur at 2–3 min intervals, last for 50–60 sec and are very powerful.

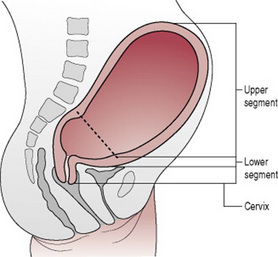

Formation of upper and lower uterine segments

By the end of pregnancy, the body of the uterus is described as having divided into two segments, which are anatomically distinct (Fig. 25.5). The upper uterine segment, having been formed from the body of the fundus, is mainly concerned with contraction and retraction; it is thick and muscular. The lower uterine segment is formed of the isthmus and the cervix, and is about 8–10 cm in length. The lower segment is prepared for distension and dilatation. Although there is no clear and strict division of these two segments, the muscle content reduces from the fundus to the cervix, where it is thinner. When labour begins, the retracted longitudinal fibres in the upper segment pull on the lower segment causing it to stretch; this is aided by the force applied by the descending presenting part.

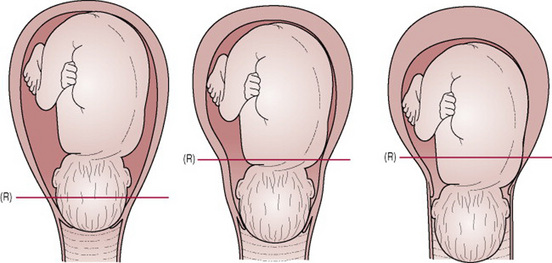

The retraction ring

A ridge forms between the upper and lower uterine segments; this is known as the ‘retraction’, or ‘Bandl’s ring’ (Fig. 25.6). It is customary to use the former term to describe the physiological retraction ring and to reserve the term ‘Bandl’s ring’ for an exaggerated degree of the phenomenon that becomes visible above the symphysis in mechanically obstructed labour when the lower segment thins abnormally. A Bandl’s ring may be associated with fetal compromise. (Lauria et al 2007).

The physiological ring gradually rises as the upper uterine segment contracts and retracts and the lower uterine segment thins out to accommodate the descending fetus. Once the cervix is fully dilated and the fetus can leave the uterus, the retraction ring rises no further.

Cervical effacement

‘Effacement’ refers to the inclusion of the cervical canal into the lower uterine segment. According to conventional obstetric belief this process takes place from above downward; that is, the muscle fibres surrounding the internal os are drawn upwards by the retracted upper segment and the cervix merges into the lower uterine segment. The cervical canal widens at the level of the internal os, whereas the condition of the external os remains unchanged (Cunningham et al 1989, O’Driscoll & Meagher 1993) (Fig. 25.2).

However, an alternative mechanism of cervical effacement has been suggested, in which the tissues in the region of the external os are taken up first. By an outward unrolling movement, the cervix thins from the external os upwards, leaving the internal os to be affected last (Beazley 1995, Olah et al 1993).

Effacement may occur late in pregnancy, or it may not take place until labour begins. In the nulliparous woman the cervix will not usually dilate until effacement is complete, whereas in the parous woman effacement and dilatation may occur simultaneously and a small canal may be felt in early labour. This is often referred to by midwives as a ‘multips os’.

Cervical dilatation

Dilatation of the cervix is the process of enlargement of the os uteri from a tightly closed aperture to an opening large enough to permit passage of the fetal head. Dilatation is measured in centimetres and full dilatation at term equates to about 10 cm.

Dilatation occurs as a result of uterine action and the counterpressure applied by either the intact bag of membranes or the presenting part, or both. A well-flexed fetal head closely applied to the cervix favours efficient dilatation. Pressure applied evenly to the cervix causes the uterine fundus to respond by contraction and retraction (Beazley & Lobb 1983, Ferguson 1941).

Show

As a result of the dilatation of the cervix, the operculum, which formed the cervical plug during pregnancy, is lost. The woman may see a bloodstained mucoid discharge a few hours before, or within a few hours after, labour starts. The blood comes from ruptured capillaries in the parietal decidua where the chorion has become detached from the dilating cervix. There should never be more than bloodstaining; frank fresh bleeding is not normal at this stage – though, as the first stage ends, during the transitional period there is often a small loss of bright red blood that heralds the second stage. Both are referred to as a ‘show’.

Mechanical factors

Formation of the forewaters

As the lower uterine segment forms and stretches, the chorion becomes detached from it and the increased intrauterine pressure causes this loosened part of the sac of fluid to bulge downwards into the internal os, to the depth of 6–12 mm. The well-flexed head fits snugly into the cervix and cuts off the fluid in front of the head from that which surrounds the body. The former is known as the ‘forewaters’ and the latter the ‘hindwaters’. In early labour, it is often possible to feel intact forewaters bulging even when the hindwaters have ruptured, making ruptured membranes a difficult diagnosis at times.

The effect of separation of the forewaters prevents the pressure that is applied to the hindwaters during uterine contractions from being applied to the forewaters. This may help keep the membranes intact during the first stage of labour and be a natural defence against ascending infection.

General fluid pressure

While the membranes remain intact, the pressure of the uterine contractions is exerted on the fluid and, as fluid is not compressible, the pressure is equalized throughout the uterus and over the fetal body; it is known as ‘general fluid pressure’ (Fig. 25.7). When the membranes rupture and a quantity of fluid emerges, the fetal head, and the placenta and umbilical cord are compressed between the uterine wall and the fetus during contractions and the oxygen supply to the fetus is diminished. Preserving the integrity of the membranes, therefore, optimizes the oxygen supply to the fetus and also helps to prevent intrauterine and fetal infection, especially in longer labours.

Rupture of the membranes

The optimum physiological time for the membranes to rupture spontaneously is at the end of the first stage of labour after the cervix becomes fully dilated and no longer supports the bag of forewaters. The uterine contractions are also applying increasing expulsive force at this time.

The membranes may sometimes rupture days before labour begins or during the first stage. If for any reason there is a badly fitting presenting part and the forewaters are not cut off effectively then the membranes may rupture early. But in most cases there is no apparent reason for early spontaneous membrane rupture. Occasionally the membranes do not rupture even in the second stage and appear at the vulva as a bulging sac covering the fetal head as it is born; this is known as the ‘caul’.

Early rupture of membranes may lead to an increased incidence of variable decelerations on cardiotocograph (CTG), which may lead to an increase in caesarean section rate if fetal blood sampling is not available (Goffinet et al 1997). A large meta-analysis (Brissen-Carroll et al 1997) suggests that routine artificial rupture of membranes (ARM) may decrease the overall length of labour by 60–120 min. ARM does not reduce the overall caesarean section rate. It was concluded in this study that routine ARM should be reserved for women who are progressing slowly in labour or have abnormalities in the CTG. All women need to give consent for this intervention and the practitioner should have a positive indication for performing ARM, which should be recorded in the notes.

Fetal axis pressure

During each contraction, the uterus rises forward and the force of the fundal contraction is transmitted to the upper pole of the fetus, down the long axis of the fetus and applied by the presenting part to the cervix. This is known as ‘fetal axis pressure’ (Fig. 25.8) and becomes much more significant after rupture of the membranes and during the second stage of labour.

Recognition of the first stage of labour

Ideally, the woman should know her own midwife and be able to contact her when labour starts. Where this is not possible, it is crucial that the first meeting between the midwife, the labouring woman and her partner establishes a rapport, which sets the scene for the remainder of labour. If the woman is planning to birth in hospital, she may worry about the reception she and her companion will receive and the attitude of the people attending her. In addition, an unfamiliar environment may provoke feelings of vulnerability and undermine her confidence. Comfortable surroundings, a welcoming manner and a midwife who greets the woman as an equal in a partnership will engender feelings of mutual respect, thus enabling the woman to relax and respond positively to the amazing forces of labour (Berry 2006, Raphael-Leff 1993).

Recognition of labour by the woman

It is the woman herself who usually diagnoses the onset of normal labour and many women and their partners are apprehensive in case the labour is very quick, resulting in an unattended birth. Education during the prenatal period is important to enable the woman to recognize the beginning of labour and understand the latent phase.

Women should be aware of what a ‘show’ is like, and know that in late pregnancy vaginal secretions are increased but should not be bloodstained. A ‘show’ in early labour or prior to the onset of labour is quite common. It is usually a pink or bloodstained jelly-like loss; labour may be imminent or under way. Women who are examined vaginally in late pregnancy should be made aware that there may be some slight blood loss after this procedure.

Braxton Hicks contractions are more noticeable in late pregnancy and some women experience them as painful. They are usually irregular or their regularity is not maintained for long spells of time. They seldom last more than 1 min. In true labour, contractions exhibit a pattern of rhythm and regularity, usually increasing in length, strength and frequency as time goes on. When the woman first feels contractions she may be aware only of backache but if she places a hand on her abdomen she may perceive simultaneous hardening of the uterus. Contractions will often be short initially, lasting 30–40 secs, and may be as much as 30 min apart. If the pregnancy is problem free, with a normal birth anticipated, the midwife should advise the woman to stay in her own surroundings, continue with her normal activities, to eat, be active and upright.

It is often difficult to be sure whether or not the membranes have ruptured spontaneously prior to labour or in early labour. The woman may be experiencing some degree of stress incontinence, so she may be unsure if it is liquor or urine that she is passing. If there is any doubt, the woman should contact her midwife. The midwife may decide to pass a speculum and look for amniotic fluid in the vagina. Digital examination should be avoided if the woman is not in labour as it will increase the risk of ascending infection and chorioamnionitis.

Initial meeting with the midwife and care in labour

Communication

When a woman begins to labour, she may have a mixture of emotions. Most women anticipate labour with a degree of excitement, anxiety, fear and hope. Many other emotions are influenced by cultural expectations and previous life experiences. The state of the woman’s knowledge, her fears and expectations are also influenced by her companions during labour. By the time labour starts, a decision will have been reached about where the woman plans to give birth. Some women may choose to give birth at home, some in hospital and some may wish to labour as long as possible at home but give birth in hospital. Whatever choice the woman makes, she must be the focus of the care, should be able to feel she is in control of what is happening to her and be able to make decisions about her care (DH 2007, Sinivaara et al 2004).

Providing that there are no complications and labour is not well advanced, the woman may remain at home as long as she feels comfortable and confident. If labour is pre-term, however, admission to hospital is always advised (see Ch. 26).

The initial examination will include details of when labour started, whether the membranes have ruptured and the frequency and strength of the contractions. The midwife should remember that the woman will be very conscious of her body and may therefore be unable to pay attention or respond while experiencing a contraction. Since the woman has embarked on an intensely energy-demanding process, inquiry should be made as to whether she has been deprived of sleep and also what food she has recently eaten. If still in early labour with a problem-free pregnancy, she should be advised to eat or drink if she wishes and remain mobile, maybe to bathe if she would find this relaxing (Champion & McCormick 2002).

Thought should be given to the social circumstances, particularly the care of other children and whether a birthing partner is available and has been contacted.

Birth plan

Most women currently give birth in hospital. Admission to hospital of a woman in labour provides the opportunity for the midwife to discuss with each woman and her partner any plans that may have already been prepared by them. An outline may be present in the case notes, or the couple may bring a birth plan with them. Some women will not have prepared a birth plan and, if this is the case, the midwife can encourage the couple to consider any preferences that they may have. A birth plan simply means that a pregnant woman has (usually) written down, and may have discussed with her midwife, the kind of birth she would like. Frequently, the partner is involved in this forward planning, which should be a flexible proposal that can be reviewed and revised during labour (DH 2007). To welcome the woman who is being admitted in labour, to introduce oneself and to ascertain how she would like to be addressed should help the midwife establish a trusting relationship. Whether or not they are already identified in a birth plan, she should explore the following issues:

The midwife should also offer to explain anything the woman or her partner wishes to know, and document all requests.

Midwife’s initial physical examination of the mother

Prior to touching the woman, a sound explanation of the proposed examination and their significance should be given. Verbal consent should be obtained and recorded in the notes. The midwife must be aware that a competent woman, with a capacity to make decisions, is within her rights to refuse any treatment regardless of the consequences to her and her unborn baby. She does not have to give a reason.

Basic observations including pulse rate, temperature and blood pressure are taken and recorded. The woman’s hands and feet are usually examined for signs of oedema. Slight swelling of the feet and ankles is normal, but pretibial oedema or puffiness of the fingers or face is not.

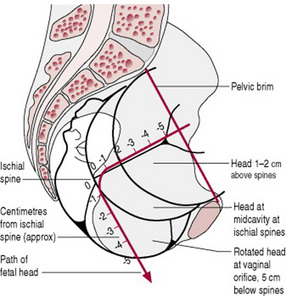

A detailed abdominal examination including symphysis fundal height as described in Ch. 17 should be carried out and recorded. Initial observations form a baseline for further examinations carried out throughout labour. The abdominal examination may be repeated at intervals in order to assess descent of the head. This is measured by the number of fifths palpable above the pelvic brim and should be recorded on the partogram.

Vaginal examination

Physical examination of the cervix is not the only way to assess labour; skills of listening watching and communicating with the woman should be used in conjunction with vaginal examination. Generally, the trend is away from routine four-hourly vaginal examinations and justification for a vaginal examination should always be recorded, a vaginal examination should be preceded by an abdominal examination, an explanation and the obtaining of verbal consent from the woman. The woman’s bladder should be empty as the head may be displaced by a full bladder as well as being very uncomfortable for the woman. With the combination of external and internal findings, the skilled midwife will have a very detailed picture of the labour and subsequent progress of labour.

Indications for vaginal examination

The midwife should realize that a vaginal examination is not always the only way of obtaining this information and that careful, continuous observation of the labouring mother will enable her to avoid making unnecessary vaginal examinations, which should be kept to a minimum. Under no circumstances should a midwife make a vaginal examination if there is any frank bleeding unless the placenta is positively known to be in the upper uterine segment.

Method

A vaginal examination during labour is an aseptic procedure. The midwife should first explain the procedure carefully to the woman and give her an opportunity to ask questions. In order to obtain the most information, the woman is usually asked to lie on her back but the technique can be easily adapted to accommodate other positions that suit the woman better. During the examination the woman’s dignity and privacy need to be considered; to avoid unnecessary exposure, the woman can be asked to move and uncover herself when the midwife is ready to begin. It appears that there is no increased risk of infection to mothers and babies if the midwife does not swab the vulva with antiseptic solution or use sterile vaginal packs (McCormick 2001); what is important is using a good hand-washing technique and wearing sterile gloves.

Findings

The midwife should observe the labia for any sign of varicosities, oedema or vulval warts or sores (see Ch. 23). She notes whether the perineum is scarred from a previous tear or episiotomy. Some cultures practise female genital mutilation (excision of the clitoris and the labia minora); scarring from this operation would be evident. The midwife should also note any discharge or bleeding from the vaginal orifice. If the membranes have ruptured the colour and odour of any amniotic fluid or discharge are noted. Offensive liquor suggests infection and green fluid indicates the presence of meconium, which may be a sign of fetal compromise or postmaturity.

Particularly in a multiparous woman, a cystocele may be found. A loaded rectum may also be felt through the posterior vaginal wall. If time allows, a suppository or microenema may be offered. Many women have some degree of loose bowels in early labour though, which reduces the need for enema or suppositories in most spontaneous labours.

As the examining fingers reach the end of the vagina they are turned so that their sensitive pads face upwards and come into contact with the cervix. Palpate around the fornices and sense the proximity of the presenting part of the fetus to the examining finger. The os uteri is located by gently sweeping the fingers from side to side. It will normally be situated centrally, but sometimes in early labour, it will be very posterior. In the rare event of a sacculated retroverted gravid uterus the cervix may be located in an extreme anterior position.

The midwife must assess the length of the cervical canal. A long, tightly closed cervix indicates that labour has not yet started. The cervical canal may be partially or completely obliterated depending on the degree of effacement (see above). In a primigravida, the cervix may be completely effaced but still closed; in this case, it will be closely applied to the presenting part and can easily be confused with a completely dilated cervix until the small tell-tale depression in the centre is found.

The consistency of the cervix is noted. It should be soft, elastic and applied closely to the presenting part.

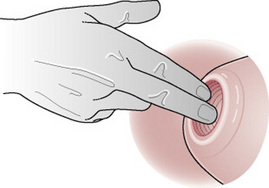

Dilatation of the cervix, that is the distance across the opening, is estimated in centimetres (Fig. 25.9); 10 cm dilatation equates to full dilatation (Fig. 25.10). In pre-term labours the smaller fetal head will pass through the os at a smaller diameter. At the point where the maximum diameters of the fetal head have passed through the os, the cervix can no longer be felt.

The midwife should always take care to feel for the cervix in every direction as a lip of cervix frequently remains in one quarter only, usually anteriorly (see also Bishop’s score, Ch. 30).

Intact membranes can be felt through the dilating os. When felt between contractions they are slack but will become tense when the uterus contracts and the fluid behind them is then more readily appreciated. The consistency of the membranes can be likened to ‘Cling film’. When the forewaters are very shallow it may be difficult to feel the membranes.

If the presenting part does not fit well, some of the fluid from the hindwaters escapes into the forewaters, causing the membranes to protrude through the cervix. This will be more exaggerated in obstructed labour. Bulging membranes are more likely to rupture early and in this case they will not be felt at all. Following rupture of the membranes the midwife needs to satisfy herself that the cord has not prolapsed by listening to the fetal heart through a contraction.

If the forewaters are felt following a leakage of amniotic fluid it may be supposed that the hindwaters have ruptured.

The presenting part is defined as the part of the fetus lying over the uterine os during labour. In order to assess the descent of the fetus in labour, the level of the presenting part is estimated in relation to the maternal ischial spines. The distance of the presenting part above or below the ischial spines is expressed in centimetres (Fig. 25.11). As a caput succedaneum (see Ch. 45) may form over the presenting part, care must be taken to relate the bony part of the fetus to the ischial spines and not to the oedematous swelling. Moulding of the fetal skull can also result in the presenting part becoming lower without any appreciable advance of the head as a whole. The midwife must bear in mind that the fetus follows the curve of Carus (see Ch. 8) and it is impossible to judge the station precisely. The purpose of making this estimate is to assess progress and it is therefore valuable for the same person to make all the vaginal examinations on any particular mother.

In 96% of cases, the vertex presents and is recognized by feeling the hard bones of the vault of the skull and the fontanelles and sutures in relation to the maternal pelvis. For details of the findings in face, brow, breech and shoulder presentations see Ch. 31.

By feeling the features of the presenting part, the midwife can deduce the position of the presentation. The vertex has the fewest diagnostic features but, being the most common presentation, is the one with which she must become most familiar.

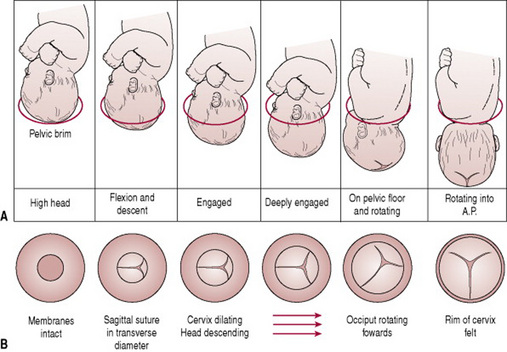

Commonly, the first feature to be felt, even in early labour, is the sagittal suture. Its slope should be noted; most frequently it will be in the right or left oblique diameter of the maternal pelvis, or it may be transverse. Later it rotates into the anteroposterior diameter of the maternal pelvis (Fig. 25.12).

Figure 25.12 (A) Diagrams showing descent of the fetal head through the pelvic brim. (B) Diagrams showing dilatation of the cervix and rotation of the fetal head as felt on vaginal examination.

The sagittal suture should be followed with the finger until a fontanelle is reached. If the head is well flexed, this will be the posterior fontanelle, which is recognized because it is small and triangular with three sutures leaving it. The anterior fontanelle is diamond shaped, covered with membrane and with four sutures leaving it. The location of the fontanelle in relation to the maternal pelvis will give information about the whereabouts of the fetal occiput.

Moulding (see Ch. 12)

This can be judged by feeling the amount of overlapping of the skull bones; it can also give additional information as to position. The parietal bones override the occipital bone and the anterior parietal bone overrides the posterior.

An understanding of the mechanism of labour (see Ch. 28) will help the midwife to appreciate the significance of flexion, rotation and descent as determinants of progress in labour.

Although the capacity of the pelvis may have been assessed antenatally, the midwife should take the opportunity to assure herself of its adequacy as she completes her vaginal examination. She may be able to feel the ischial spines, which should be blunt, and note the size of the subpubic angle, which should be about 90° and accommodate the two examining fingers. Prominent ischial spines and a reduced subpubic angle are unfavourable features associated with the android pelvis.

Keeping the woman fully informed in labour shows sensitivity to her needs and is an essential, integral component of the support provided by the midwife.

Cleanliness and comfort

Bowel preparation

If there has been no recent bowel action (depending on the woman’s normal bowel habits) or the rectum feels loaded on vaginal examination, the woman should be consulted and asked if she would like an enema or suppositories. This is never done as a routine procedure. A small, low volume disposable enema may be administered, or two glycerine suppositories. There is no evidence to suggest a full rectum causes delay in the progress of labour (Drayton 1990), but the woman may be embarrassed if she feels she is likely to pass faeces during labour.

Perineal shave

Routine perineal shaving has not been carried out in the UK for some years. Research has shown that perineal shaving is unnecessary and does not improve infection rates. Dislike of the procedure and abrasions sustained cause discomfort for many women and detract from the positive experience of labour (Drayton 1990).

Bath or shower

If a woman has had no access to a bath or shower at home, she may wish to use these facilities on admission to the hospital. For women in normal labour, a warm bath (or birthing pool) can be an effective form of pain relief that allows increased mobility with no increased incidence of adverse outcome for mother or baby (Alderdice et al 1995, Gilbert & Tookey 1999). The woman may choose to rest in the bath for a long time. The midwife should invite the mother who is mobile to have a bath or shower whenever she wishes during normal labour.

Clothing

It is entirely up to the individual woman what she wears in labour. If in hospital she may prefer to wear the loose gown offered or she may feel more comfortable wearing her own choice of clothing. As long as she is aware that the garment may become wet and bloodstained and that she may require more than one, there is no reason to restrict her choice.

Records

Midwifery is becoming increasingly litigious. The midwife’s record of labour is a legal document and must be kept meticulously. The records may be examined by any court for up to 25 years, they may go before the Nursing and Midwifery Council professional conduct or health committee, and will usually be examined in the audit process of statutory supervision or on behalf of the Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts. The midwives rules and standards (NMC 2004) and guidelines for records and record keeping (NMC 2005) both reiterate that records should be as contemporaneous as is reasonable, and must be authenticated with the midwife’s full signature; it is good practice to print the author’s name under the signature. A midwife must not destroy or arrange for destruction of these records and must be satisfied they are stored securely.

The records are created to give comprehensive and concise information regarding the woman’s observations, her physical, psychological and sociological state, and any problem that arises as well as the midwife’s response to that problem, including any interventions. They are there to serve the interest of the woman and to demonstrate that the midwife has understood and carried out her duty of care as a reasonable midwife should.

An accurate record during labour provides the basis from which clinical improvements, progress or deterioration of the mother or fetus can be judged. For this reason, the notes should be kept in chronological order.

The maternity record is shared between the midwife and the obstetrician. The obstetrician makes notes of his or her findings, timing of visits and any prescriptions made. The same standards apply to all practitioners. The midwife usually enters the summary of labour and initial details about the baby.

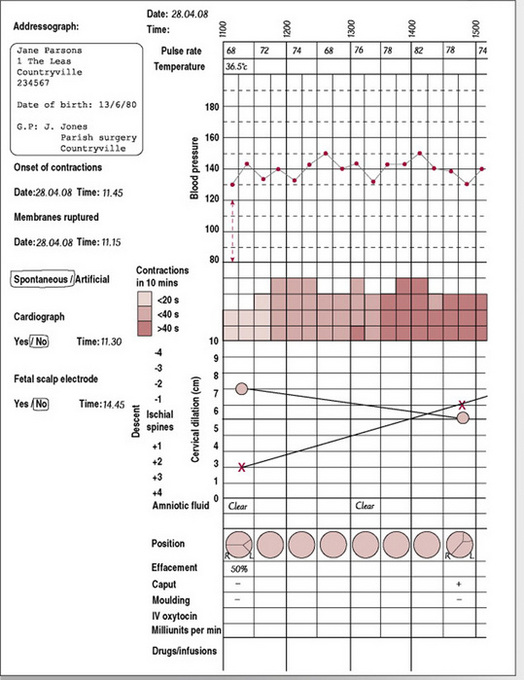

In recent years, the partogram or partograph has been widely accepted as an effective means of recording the progress of labour. It is a chart on which the salient features of labour are entered in a graphic form and therefore provides the opportunity for early identification of deviations from normal. Figure 25.13 shows one example of a partogram, which is a visual means of recording all observations and includes a pictorial record of the rate of cervical dilatation. The charts are usually designed to allow for recordings at 15 min intervals and include:

The cervicograph is the diagrammatic representation of the dilatation of the cervix charted against the hours in labour. Some studies (Friedman & Sachtleben 1965, Pearson 1981) have shown that the cervical dilatation time of normal labour has a characteristic sigmoid curve. This curve can be divided into two distinct parts – the latent phase and the active phase. The active phase has been said to proceed at a rate 0.5–1 cm hr, but more recent work has challenged this rigid view (Albers 1999, Lavender et al 2006). The disadvantage of using such prescribed parameters of normal is the temptation to make all women fit predetermined criteria for normality. The rate of progress in labour must be considered in the context of the woman’s total well-being and choice.

If it becomes necessary to confer with an obstetrician, paediatrician or other practitioner, the midwife records the times and the nature of the consultation, including whether the practitioner was informed, consulted or asked to be present.

Medicine records

Midwives have an exemption from needing a prescription for specific medicines used for the care of women in normal labour (see Ch. 49). Even so, most NHS Trusts also have locally agreed patient group directions to which the midwife should adhere; these usually guide the midwife as to which medicines are preferred and what doses and frequency are to be used within that Trust. If the midwife is practising outside the area in which she has notified her intention to practise, she should consult the supervisor of midwives regarding any matters relating to the supply, administration, storage or surrender of controlled drugs or medicines (NMC 2004).

As well as being entered on the partogram, doses of drugs are recorded on the prescription sheet, in the summary of labour and, in the case of controlled drugs, in the Controlled Drug Register.

Box 25.1 lists key points for care in the first stage of labour.

Box 25.1 Key points for the first stage of labour

Albers LL. The duration of labor in healthy women. Journal of Perinatology. 1999;19(2):114-119.

Alderdice F, Renfrew M, Marchant S, et al. Labour and birth in water in England and Wales. Report of a survey funded by the Department of Health into the safety of water birth. British Medical Journal. 1995;310(6983):837.

Allman ACJ, Genevier ES, Johnson MR, et al. Head to cervix force: an important physiological variable in labour. 1. The temporal relation between head to cervix force and intrauterine pressure during labour. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1996;103:763-768.

Arulkumaran S. Poor progress in labour including augmentation, malpositions and malpresentations. In: James D, Steer P, Gonik B, editors. High risk pregnancy. London: W B Saunders; 1996:1063.

Beazley JM. Natural labour and its active management. In Whitfield C, editor: Dewhurst’s textbook of obstetrics and gynaecology for postgraduates, 5th edn, Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1995. Ch. 21

Beazley JM, Lobb MO. Aspects of care in labour. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1983.

Berry D. Health communication: theory and practice. Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2006;151.

Brissen-Carroll G, Fraser W, Breart G, et al. The effect of routine early amniotomy on spontaneous labour: a meta analysis. The Cochrane Collaboration, Issue 4. Update Software, Oxford, 1997.

Champion P, McCormick C. Eating and drinking in labour. Oxford: Books for Midwives, 2002.

Cunningham FG, MacDonald PC, Grant NF. Williams obstetrics, 18th edn. London: Prentice-Hall, 1989.

DH (Department of Health). Maternity matters: Choice, access and continuity of care in a safe service. London: DH, 2007.

Drayton S. Midwifery care in the first stage of labour. In: Alexander J, Levy V, Roch S, editors. Intrapartum care: a research based approach. Macmillan: Basingstoke, 1990.

Ferguson JK. A study of the motility of the intact uterus at term. Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1941;73:359-366.

Fisher C, Hauck Y, Fenwick J. How social context impacts on women’s fears of childbirth: a Western Australian example. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;63(1):64-75.

Friedman EA, Sachtleben MR. Station of the fetal presenting part. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1965;93(4):522-529.

Gee H, Olah KS. Failure to progress in labour. In: Studd J, editor. Progress in obstetrics and gynaecology. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1993. Ch. 10

Gharoro EP, Enabudoso EJ. Labour management: an appraisal of the role of false labour and latent phase on the delivery mode. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;26(6):534-537.

Gilbert RE, Tookey PA. Perinatal mortality and morbidity among babies delivered in water: surveillance study and postal survey. British Medical Journal. 1999;319(7208):483-487.

Goffinet F, Fraser W, Marcoux S, et al. Early amniotomy increases the frequency of fetal heart rate abnormalities. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;104:548-553.

Gross MM, Hecker H, Matterne A, et al. Does the way that women experience the onset of labour influence the duration of labour? British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;113(3):289-294.

Halldorsdottir S, Karlsdottir SI. Journeying through labour and delivery: perceptions of women who have given birth. Midwifery. 1996;12:48-61.

Lauria MR, Barthold JC, Zimmerman RA, et al. Pathologic uterine ring associated with fetal head trauma and subsequent cerebral palsy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;109(2):495-497.

Lavender T, Alfirevic Z, Walkinshaw S. Effect of different partogram action lines on birth outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;108(2):295-302.

McCormick C. Vulval preparation in labour: use of lotions or tap water. British Journal of Midwifery. 2001;9(7):453-455.

Niven C. Psychological care for families: before, during and after birth. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann, 1992.

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council). Midwives rules and standards. London: NMC, 2004.

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council). Guidelines for records and record keeping. London: NMC, 2005.

Nolan M. Supporting women in labour: the doula’s role. Modern Midwife. 1995;5(3):12-15.

O’Driscoll K, Meagher D. Active management of labour, 3rd edn. London: Mosby, 1993.

Olah KS, Brown JS, Gee H. Cervical contractions: the response of the cervix to oxytocic stimulation in the latent phase of labour. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1993;100:635-640.

Pearson J. Partography. Nursing Mirror. 1981;153(2):xxv-xxix.

Raphael-Leff J. Pregnancy: the inside story. London: Sheldon, 1993.

Seitchik J. The management of functional dystocia in the first stage of labour. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1987;30(1):42-49.

Sherblom Matteson P. Women’s health during the childbearing years: A community based approach. New York: Mosby, 2001;358-359.

Sinivaara M, Suominen T, Routasolo P, et al. How delivery ward staff exercise power over women in communication. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;46(1):33-41.

Stables D. Physiology in childbearing. London: Baillière Tindall, 1999;450.

Tortora G, Grabowski S. Principles of anatomy and physiology, 9th edn. John Wiley, New York, 2000;1039-1040.

WHO (World Health Organization) Department of Reproductive Health and Research. Care in normal labour. Geneva: A practical guide. WHO, 1997.

Woods T. The transitional stage of labour. MIDIRS Midwifery Digest. 2006;16(2):225-228.

Wuitchik M, Bakal D, Lipshitz J. The clinical significance of pain and cognitive activity in latent labour. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1989;73(1):25-41.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Intrapartum guidelines. Online. Available: www.nice.org.uk.